Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) play pivotal roles in responding to foreign entities during an innate immune response and initiating effective adaptive immunity as well as maintaining immune tolerance. The sensitivity of DCs to foreign stimuli also makes them useful cells to assess the inflammatory response to biomaterials. Elucidating the material property-DC phenotype relationships using a well-defined biomaterial system is expected to provide criteria for immuno-modulatory biomaterial design. Clinical titanium (Ti) substrates, including pretreatment (PT), sand-blasted and acid-etched (SLA), and modified SLA (modSLA), with different roughness and surface energy were used to treat DCs and resulted in differential DC responses. PT and SLA induced a mature DC (mDC) phenotype, while modSLA promoted a non-inflammatory environment by supporting an immature DC (iDC) phenotype based on surface marker expression, cytokine production profiles and cell morphology. Principal component analysis (PCA) confirmed these experimental results, and it also indicated that the non-stimulating property of modSLA covaried with certain surface properties, such as high surface hydrophilicity, % oxygen and % Ti of the substrates. In addition to the previous research that demonstrated the superior osteogenic property of modSLA compared to PT and SLA, the result reported herein indicates that modSLA may further benefit implant osteo-integration by reducing local inflammation and its associated osteoclastogenesis.

Keywords: dendritic cells, titanium, immune response, inflammation

1. Introduction

Dendritic cells play a critical role in orchestrating the host responses to a wide variety of foreign antigens and are the most potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that bridge innate and adaptive immunity [1]. Dendritic cells are sentinel cells of the hematopoietic origin and differentiate from CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells or CD14+ monocytes [2]. Under steady state conditions, DCs reside in the periphery, where they use their pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), conserved motifs derived from pathogens [3,4], and “danger signals”, tissue fragments and intracellular molecules resulting from tissue necrosis [5]. Upon the challenge with the PAMPs or inflammatory cytokines, DCs internalize, process, and present exogenous antigens to T cells via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, while DCs migrate to the lymph nodes and become phenotypically mature. Dendritic cell maturation is a continuous process that results in down-regulation of endocytoic capacity, up-regulation of surface co-stimulatory and MHC class II molecules, and enhanced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12, which together facilitate the activation of T cells and B cells and the initiation of adaptive immunity and immune memory [1,4,6]. Dendritic cells are also central in immunological self-tolerance by actively inducing the formation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [7]. Therefore, DCs are pivotal in both effective immunity and immune tolerance.

Dendritic cells are also key players in osteoimmunology. In particular, DCs have been identified in the synovial tissue and synovial fluid of joints in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients [8,9] and have been implicated in inflammation-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone loss [10]. Human or mouse activated CD4+ T cells induced by environmental stimuli were shown to up-regulate surface-bound and soluble receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL), which is a prime regulator of osteoclast differentiation and activation [11]. The ligation of RANKL to its receptor, RANK, on osteoclast precursors resulted in inflammation-induced bone loss in diseases such as RA and periodontitis [12–15]. Therefore, upon inflammation, DCs can become mature and initiate T cell activation, which in turn promotes the differentiation and survival of osteoclasts.

Biomaterials commonly used in combination products were previously shown to differentially affect DC phenotype in vitro [16,17]. For instance, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and chitosan films promote a mDC phenotype; agarose films and even more so, hyaluronic acid films, maintain an iDC phenotype [16,17]. Furthermore, PLGA, but not agarose, enhanced the humoral immunity against a co-delivered model antigen in vivo [18,19]. These studies demonstrated that biomaterials can be used to control the DC phenotype, thereby potentially modulating associated in vivo immune responses. This potential of biomaterials to affect host response can be manipulated to either suppress immune responses induced by a tissue-engineered construct, or enhance the protective immunity induced by a biomaterial-based vaccine. Elucidation of the biomaterial properties that control DC phenotype are expected to inform immuno-modulatory biomaterial design. However, due to the limitations of the biomaterials used in the previous studies, it was unclear which biomaterial properties determined distinct responses. In order to delineate material property–DC phenotype relationships, a well-defined biomaterial system with detailed material characterization is needed.

In this study, clinical titanium (Ti) surfaces commercially available, including PT, SLA and modSLA, for dental implants were used to 1) analyze DC response to material properties and 2) determine the possible immunological outcomes induced by the different Ti substrates, using DC phenotype as an indicator of inflammatory response. These surfaces have been prepared to possess distinct microtopography and surface energy. PT substrates were chemically polished to have a smooth finish; SLA surfaces were prepared by sand-blasting and acid-etching of the PT surfaces for increased roughness; modSLA surfaces had the same roughness as SLA, but were protected from contamination by hydrocarbons and carbonates naturally occurring in the atmosphere to maintain its high surface energy. The surface material properties of these Ti substrates have been extensively characterized and were shown to induce distinct responses of human osteoblast-like MG63 cells, as well as normal human and rat osteoblasts [20–22]. The osteoblastic differentiation of MG63 cells was enhanced on rougher Ti surfaces such as SLA, and such differentiation was sensitive to both micron and submicron surface structures [23,24]. Furthermore, superior to PT or SLA, modSLA substrates promoted enhanced differentiation of osteoblasts and production of local osteogenic factors such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1) and osteocalcin, indicating that high surface energy and surface roughness synergistically support an osteogenic microenvironment [20]. In addition, modSLA implants significantly increased bone-to-implant contact in miniature pigs as compared to SLA surfaces [25] and more rapid peri-implant bone formation in humans [26,27], consistent with the in vitro enhancement of osteoblast differentiation on modSLA surfaces.

PT, SLA and modSLA surfaces were used to treat DCs and resulted in differential phenotype, which was then covaried to the surface properties of the Ti substrates, using principal component analysis (PCA). Furthermore, the overall results indicated that modSLA may promote a more immature phenotype of DCs, which is anti-inflammatory, thereby potentially supporting osteoblast differentiation by suppressing local inflammation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ti substrates

Ti disks were prepared from 1-mm thick sheets of grade 2 unalloyed Ti (ASTM F67; “Unalloyed titanium for Ti for surgical implant applications”) and kindly supplied by Institut Straumann AG (Basel, Switzerland). The Ti disks were punched to be 15 mm in diameter for snug fit in the wells of 24-well tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) plates (Costar) (Corning, Corning, NY). The methods used to produce the PT, SLA and modSLA Ti substrates were previously described [20,28]. The surface properties of the Ti substrates were previously extensively characterized and are summarized in Table 1 for air-water contact angle, mean-peak-to-valley roughness (Ra) and surface chemical composition [21,29].

Table 1.

| PT | SLA | ModSLA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air-water contact angle Θ | 95.8 ± 4.0° | 138.3 ± 4.2° | ~0° | |

| Roughness (Ra) (μm) | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 3.97 ± 0.04 | 3.97 ± 0.04 | |

| Chemical Composition | O (%) | 47.6 ± 1.2 | 50.2 ± 2.6 | 60.1 ± 0.7 |

| Ti (%) | 17.9 ± 1.0 | 14.3 ± 1.4 | 23.0 ± 1.1 | |

| N (%) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | |

| C (%) | 29.2 ± 1.5 | 34.2 ±2.0 | 14.9 ± 0.9 | |

2.2. Human dendritic cell culture

Human blood was collected from healthy donors with informed consent and heparinized (333 U/ml blood) (Abraxis Pharmaceutical Products, Schaumburg, IL) at the Student Health Center Phlebotomy Laboratory, in accordance with protocol H10011 of the Institutional Review Board of Georgia Institute of Technology. Dendritic cells were derived from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using a previously described method [30] with some modifications. Briefly, PBMCs from collected blood were isolated by differential centrifugation using lymphocyte separation medium (Cellgro MediaTech, Herndon, VA). The residual red blood cells were lysed with RBC lysis buffer (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA), and the PBMCs were washed with Mg2+- and Ca2+-free phosphate buffer saline (D-PBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Ten milliliters of PBMCs were plated in a Primaria 100×20 mm2 tissue-culture dish (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at a concentration of 5×106 cells/ml in DC media [RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen), 10% heat inactivated FBS (Cellgro MediaTech) and 100 U/ml of penicillin/streptomycin (Cellgro MediaTech)]. After incubation for 2 hours at 95% relative humidity and 5% CO2 at 37°C to select for adherent monocytes, the dishes were washed three times with warm DC media to remove non-adherent cells. The remaining adherent cells were incubated with 10 ml/plate fresh warm DC media, supplemented with 1000 U/ml GM-CSF and 800 U/ml IL-4 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), for 5 days to induce the differentiation of monocytes into iDCs.

2.3. Exposure of DCs to Ti substrates

On day 5 of culture, loosely adherent and non-adherent cells containing iDCs were harvested and resuspended in DC media with 1000 U/ml GM-CSF and 800 U/ml IL-4 at 5×105 DCs/ml. One milliliter of cell suspension (5×105 DCs) was plated on Ti disks in the wells of a 24-well plate, treated with 1 μg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (E. coli 055:B5; Sigma, St Louis, MO) for the positive control of mDCs, or left untreated in TCPS plates for the negative control of iDCs. Differentially-treated DCs were collected after 24 h for analysis. The loosely- or non-adherent fraction was collected by gentle pipetting of the cell suspension from the tissue culture plates. The cell culture supernatants were collected after centrifugation of the cell suspension at 1100 rpm for 10 min and stored at −20°C until cytokine analysis. To remove the adherent fraction, 0.5 ml warm cell dissociation buffer (Sigma) was added into each well and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The plate was gently tapped against the bench-top for 30 times every 5 min to dislodge adherent cells. The cell number of both fractions was quantified using a Multisizer™ 3 Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA).

2.4. Flow cytometry for surface marker expression

After 24 h exposure to Ti substrates, DCs were harvested and analyzed for surface expression of DC maturation-associated markers, including CD83, CD86, and HLA-DQ, whose levels are up-regulated upon DC maturation. CD83 is a DC maturation marker; CD86 is a co-stimulatory molecule; HLA-DQ is a major histocompatibility (MHC) class II molecule. Twelve independent experiments were performed using DCs each derived from a different donor. The levels of surface marker expression were monitored by flow cytometry using previously described methods [31]. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 1100 rpm for 10 min, resuspended in cell-staining buffer (0.1% BSA and 2 mM EDTA in D-PBS, pH 7.2), and stained with fluorescently-labeled antibodies, including CD83 (clone HB15a; mouse IgG2b) (Immunotech, Marseille, France), CD86 (clone BU63; mouse IgG1κ) (Ancell Corporation, Bayport, MN), and HLA-DQ (clone TU169; mouse IgG2aκ) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The cells were stained for 30 min at 4°C, and analyzed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (Beckton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

2.5. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of adherent DCs

DCs were cultured on the Ti disks in a 12-well TCPS plate to ensure easy removal of the disks during SEM sample preparation. After 24 h of culture, the disks were washed three times with warm D-PBS to remove the non- or loosely-adherent cells. The cells/Ti samples were fixed with 1 ml 3.5% EM grade glutaraldehyde (Sigma) with 2% (w/v) tannic acid (Sigma) in 0.1 M Sorenson’s phosphate buffer (P-buffer) overnight. The cells were washed three times with P-buffer and were post-fixed with 0.5 ml 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4, Sigma) in P-buffer for 1 h to impart partial conductivity [32]. After three washes, the cells were treated with 1 ml 2% (w/v) aqueous tannic acid for 1 h (to preserve the fine structures of cells and aid in the subsequent OsO4 reduction at its binding sites). After three washes, the cells were post-fixed again with 0.5 ml 1% OsO4 in P-buffer for 1 h. The cells were then dehydrated in a sequential series of increasing concentrations of acetone: 15%, 30%, 45%, 75%, 90%, and 100% acetone for 30 min at each concentration. Subsequently, the samples were dried in an E3000 Critical Point Dryer (Quorum Technologies, Guelph, Ontario, Canada) and sputter coated with a thin layer (~5 nm) of gold (Polaron Sputter Coater SC7640; Quorum Technologies). The micrographs were collected using Hitachi S-800 scanning electron microscope.

2.6. Multiplex cytokine profiling

The supernatants collected from the cell culture medium in the presence of Ti substrates or controls were stored at −20°C and were thawed only once for multiplex cytokine analysis. The levels of cytokines and chemokines in the cell culture supernatants were measured using Bio-Plex suspension array systems (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, beads conjugated with capture antibodies for the target analytes were mixed and transferred to a 96-well filter plate (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Supernatant samples were added to the wells for 30 min incubation. After the beads were washed three times in the filter plate using a vacuum manifold (Pall Life Science, Ann Arbor, MI), the beads were incubated with biotinylated detection antibodies for 30 min. After another three washes, the beads were incubated with streptavidin-PE for 10 min. After three final washes, the beads were analyzed using a Bio-Plex 200 instrument with Bio-Plex Manager 4.0 software. Through 12 independent experiments each with a different donor, 4-plex cytokine analysis was performed for TNF-α (pro-inflammatory), IL-1ra, IL-10 (anti-inflammatory), and MIP-1α (chemokine). The production of these cytokines was normalized by the cell number in the well. Because normalization did not affect the results in the 4-plex analysis, a wider panel of cytokines and chemokines [pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-12p70, IL-15, IL-18 and TNF-α), anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1ra and IL-10), a pleiotropic cytokine (IL-16), and chemokines (IL-8, MCP-1, and MIP-1α)] were analyzed in a separate experiment with three different donors but were not normalized by the cell number.

2.7. Statistical analysis

To observe any significant differences between all sample groups in pairs, a pair-wise general linear model of the two-way ANOVA with a mixed model followed by Tukey post test was used. For all statistical methods, the Minitab software (Version 14, State College, PA) was used, and the p-value equal to or less than 0.05 was considered significant.

2.8. Principal component analysis (PCA)

PCA was performed to analyze the phenotype and Ti substrate property data and to draw correlations between DC response and material properties. PCA allows for the simultaneous analysis of the original large set of variables by reducing the number of dimensions to a few principal components (PCs). This is achieved by finding new axes to represent dimensions with maximal variability and highlight the global covariance patterns of the variables. Typically, only two to three axes (PCs) are sufficient to capture most information from the data [33]. The phenotype variables included levels of surface markers, CD83, CD86 and HLA-DQ, and cytokine production of TNF-α, IL-1ra, IL-10 and MIP-13; the material properties variables included air-water contact angle, surface roughness and surface chemical composition, % C, O, N and Ti. The measurements from the experiments with twelve donors were organized into a data matrix, to which the PCA algorithm was applied to extract the latent correlations among the variables. All data were pre-processed by log transformation, mean centering and unit-variance scaling [34]. Log transformation ensured Gaussian distributions of data, while mean centering and unit-variance scaling allowed the variances of different variables to have equal chances of being projected onto the PCs [35]. Despite the large variances, all data points were included, and the variances were accepted as natural variations of human primary immune cell responses.

Two PCAs were performed using different sets of variables for extracting different information from the multi-dimensional data. The first analysis aimed to determine the overall effects of PT, SLA and modSLA on DC phenotype relative to the controls. Average values of the phenotype variables and all of the five treatments, including PT, SLA, modSLA, TCPS and TCPS + LPS, were organized into a data matrix. The phenotype variables were organized in the columns of the matrix and the treatments in the rows of the matrix (Fig. 6A). The objective of the second analysis was to draw correlations between material properties of Ti substrates and DC phenotype. For this analysis, individual values of the phenotype variables from the three biomaterial treatments (PT, SLA and modSLA) were used. The material properties were also included in this data matrix. The phenotype variables and the material properties were organized in the columns and the treatments from each donor in the rows of the matrix (Fig. 7A). PCA was performed using the software SIMCA P+ (Umetrics, Malmö, Sweden).

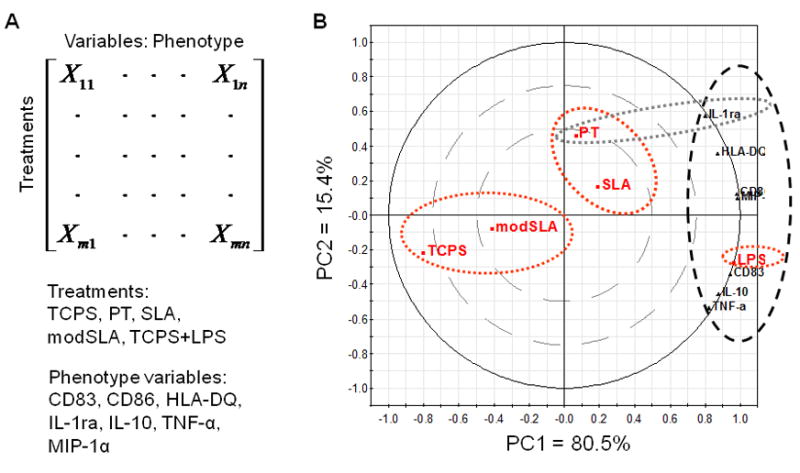

Figure 6.

Confirmation of the relative effects of Ti substrates (PT, SLA or modSLA) on DC phenotype relative to the iDC (TCPS) and mDC (TCPS+LPS) controls using PCA. (A) The organization of data into a matrix for PCA. (B) PCA biplot of the DC phenotype variables, including surface marker expression of CD83, CD86 and HLA-DQ and production of TNF-α, IL-1ra, IL-10 and MIP-1α, for PT, SLA, modSLA, TCPS and LPS treatments of DCs. PC1 represents 80.5% of data variance, and PC2 explains 15.4% of data variance, which together capture 95.9% of data variance with little loss of information. The red dotted ellipses represent clustering of similar treatment groups (e.g. TCPS and modSLA form one cluster, while PT and SLA form another cluster). The thick black dotted ellipse indicates the location of phenotype variables, which is strongly associated with LPS-treated DCs along the far end of PC1. The gray dotted ellipse represents the association of PT treatment and IL-1ra release along PC2.

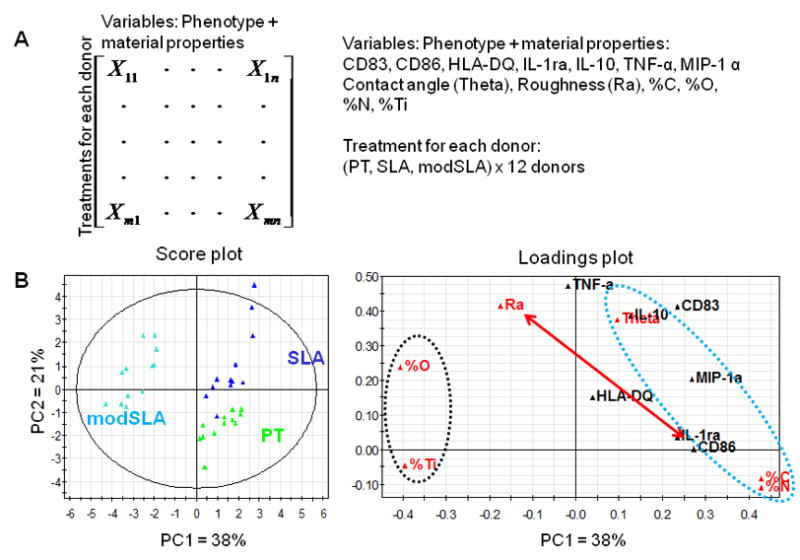

Figure 7.

Assessment of material property–DC phenotype relationships using PCA. (A) The organization of the data into a matrix for PCA. (B) PCA score plot and loadings plot for the first two PCs. PC1 represents 38% of data variance, and PC2 explains 21% of data variance, which together capture 59% of data variance. The red double- headed vector indicates that CD86 and Ra primarily influence PC1 and PC2, respectively, suggesting that roughness has little effect on CD86 expression. The blue dotted ellipse indicates that material properties of air-water contact angle (Theta), surface %C and %N are more associated with the phenotype variables. Conversely, the black dotted ellipse shows that properties such as %O and %Ti are situated on the opposite side of the phenotype variables, suggesting that these material properties are more associated with an iDC phenotype. The data set can be best modeled by 3 PCs that capture a total of 74.4% information. However, because score plot and loading plots of PC1 and PC3 yield similar conclusions as those of PC1 and PC2, and because plots of PC2 and PC3 do not yield meaningful information, only the plots of PC1 and PC2 are shown for simplicity.

3. Results

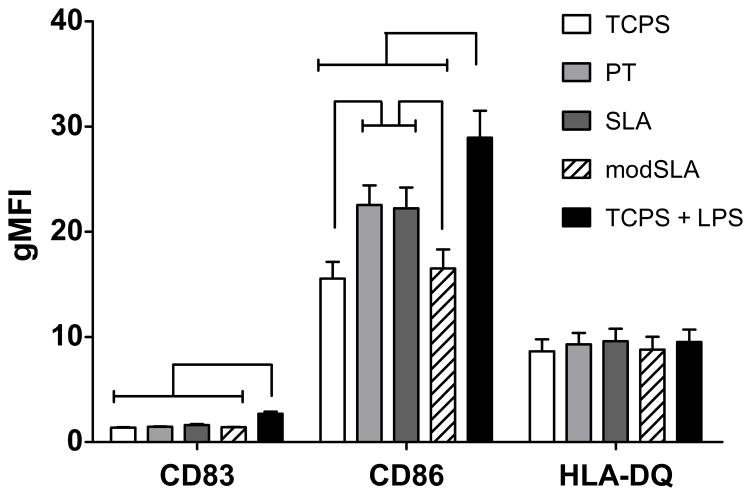

3.1. The expression of DC maturation-associated markers was substrate-dependent

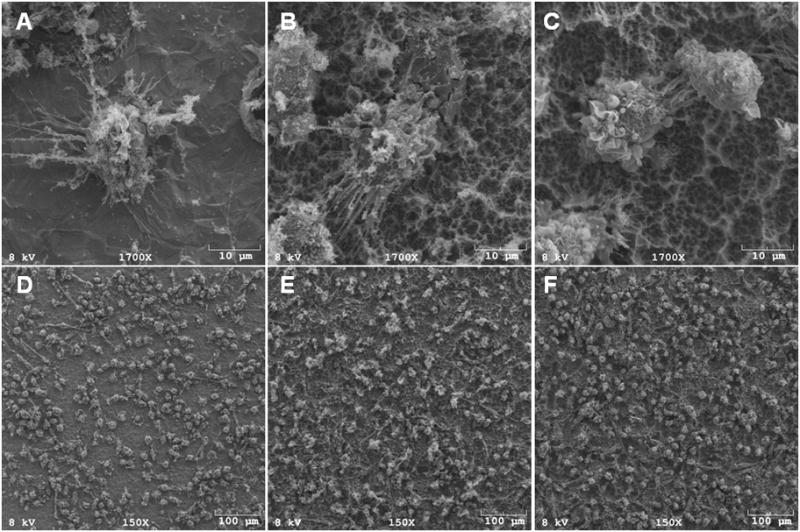

As shown in Figure 1, PT- and SLA-treated DCs both expressed higher CD86 levels as compared to the TCPS-treated iDC control; however, no difference was found between PT and SLA treatments for CD86 expression in DCs. In contrast, modSLA surfaces maintained a CD86 expression level that was similar to the iDC control. However, DCs treated with modSLA substrates were still able to fully mature in response to LPS (data not shown). LPS-treated DCs expressed higher CD86 levels compared to DCs treated with any of the substrates. The expression levels of CD83 or HLA-DQ were not significantly affected upon treatments with the different Ti substrates. Furthermore, SEM micrographs showed that DCs treated with PT or SLA substrates exhibited more dendritic processes associated with mDCs, while modSLA treated DCs were rounded, which is a morphology associated with iDCs (Fig. 2A–C).

Figure 1.

Surface marker expression of DCs in response to treatment with different Ti surfaces (PT, SLA or modSLA) as compared to the iDC (TCPS) and mDC (TCPS+LPS) controls. Geometric mean fluorescent intensities are shown for n = 12 donors (mean±SEM). Brackets represent statistical significance among treatments with p30.05.

Figure 2.

SEM of DCs on Ti surfaces. High magnification micrographs (1700x) show that DCs on PT (A, D) or SLA (B, E) exhibited highly dendritic morphology, which is associated with mDCs; DCs on modSLA (C, F) exhibited rounded morphology, which is associated with iDCs. Low magnification scans (150x) (D, E and F) show that the different Ti surfaces adhere similar numbers of DCs. Data are from one of two separate experiments, both with comparable results.

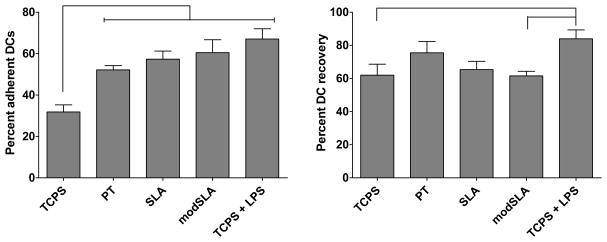

3.2. Similar numbers of DCs adhered to the different Ti substrates

After a 24 h exposure to the Ti substrates, the percent DC recovery (recovered DCs / plated DCs) was similar for both the loosely- or non-adherent and adherent fractions of cells (Fig. 3). Percent DC recovery from the LPS-treated culture was higher than from DCs cultured on TCPS or treated with modSLA. Furthermore, the percent adherent DCs (adherent DCs / recovered DCs) was not different among the different Ti substrates, but percent adherent DCs on TCPS was lower than on any of the substrates (Fig. 3). Low magnification (150x) SEM images of cells remaining on the substrates after non-adherent cells were washed away, indicate that the number of adherent DCs on these Ti substrates was similar (Fig. 2D–F).

Figure 3.

Percent adherent cells on and percent DC recovery from the Ti substrates and controls. Left: Percent of cells (adherent DCs/recovered DCs) adherent to the different Ti surfaces (PT, SLA or modSLA) was not significantly different from each other. Right: Percent DC recovery from modSLA was lower compared to mDC control (TCPS+LPS). n=6 donors (mean±SEM). Brackets represent statistical significance among treatments with p≤0.05.

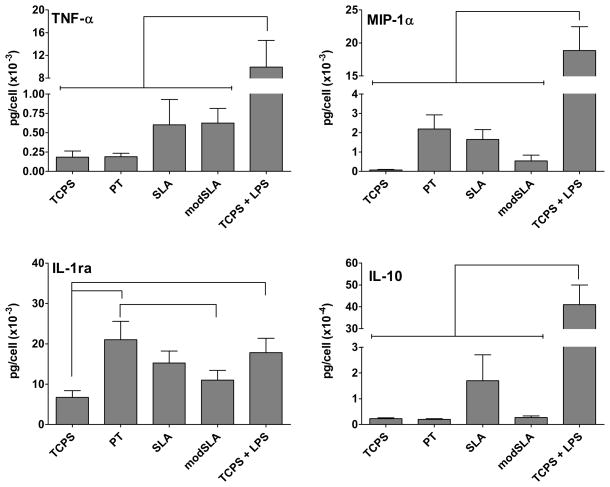

3.3. Ti substrates induced differential cytokine production by DCs

Multiplex cytokine analysis showed that production of factors was substrate-dependent. PT surfaces induced higher levels of IL-1ra production by DCs compared to the negative control or modSLA substrates. As expected, LPS-treated DCs released higher amounts of IL-1ra compared to the iDC control (Fig. 4). Although some trends in the production of TNF-3, IL-10 and MIP-13 were observed among the Ti substrates, the differences were not statistically significant. LPS-treated DCs produced higher TNF-α, IL-10 and MIP-1α relative to any other treatments.

Figure 4.

Cytokine and chemokine release for DCs treated with Ti surfaces (PT, SLA or modSLA) as compared to the iDC (TCPS) and mDC (TCPS+LPS) controls. The cytokine amount was normalized to the total cell number in the well. n=12 donors (mean±SEM). Brackets represent statistical significance among treatments with p≤0.05.

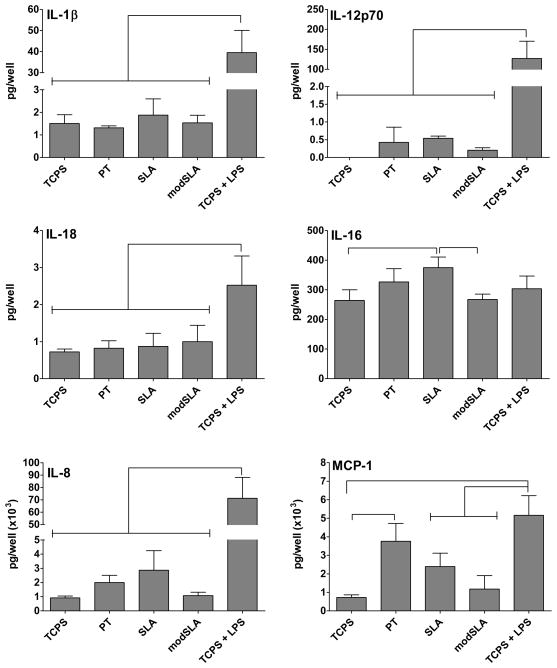

The analysis of a wider array of cytokines and chemokines (Fig. 5) indicated that SLA surfaces induced higher levels of IL-16 production by DCs compared to modSLA or TCPS, while PT-treated DCs released higher amounts of MCP-1 relative to the TCPS control and to a level not different from LPS-treated DCs. LPS induced increased production of MCP-1 compared to TCPS, SLA or modSLA. Furthermore, all of these three Ti substrates induced minute production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-12p70 and IL-18) compared to LPS treatment of DCs. Although the substrate-induced production of IL-8 by DCs followed the trend of SLA > PT > modSLA, the differences were not significant. In addition, LPS-treated DCs released higher IL-8 compared to TCPS or any substrate treatment. All Ti substrates induced IL-15 production by DCs at levels below detection limit (data not shown). Trends of TNF-α, IL-1ra, IL-10 and MIP-1α production were similar to Fig. 4.

Figure 5.

Cytokine and chemokine release for DCs treated with Ti surfaces (PT, SLA or modSLA) as compared to the iDC (TCPS) and mDC (TCPS+LPS) controls. The cytokine amount produced by the cells in the well is shown. n=3 donors (mean±SEM). Brackets represent statistical significance among treatments with p≤0.05. The trends of production of TNF-α, IL-1ra, IL-10 and MIP-1α were similar to those in Figure 4 and hence not shown.

3.4. PCA indicated differential levels of DC maturation were induced by Ti substrates

The first PCA analysis confirmed experimental data that extents of DC maturation were substrate-dependent (Fig. 6). The data set could be modeled using two PCs, which were able to represent 95.9% of the data. The PCA biplot indicated that modSLA clustered with TCPS for its effects on DC responses, while SLA and PT formed another cluster that was closer to the LPS treatment. As expected, LPS induced drastic phenotypic changes in DCs and was strongly associated with the phenotype variables along the far end of the first PC (PC1) (thick black dotted ellipse in Fig. 6). Consistent with the experimental result, PT treatment was more strongly associated with IL-1ra production than the other two Ti treatments as shown along the second PC (PC2) (thin black dotted ellipse in Fig. 6). Overall, SLA induced higher DC maturation as compared to PT because it was situated closer to the phenotype variables along PC1, while modSLA-treated DCs were negatively associated with the phenotype variables (Fig. 6).

3.5. PCA suggested DC phenotype-material property relationships

The second PCA analysis suggested DC phenotype–material property relationships (Fig. 7). The data set could be modeled by three PCs capturing a total of 74.4% of information. The first 2 PCs (PC1 and PC2) were able to represent 59% of data variance. Instead of a biplot, the score plot and loadings plot are shown for clarity. The relative locations of PT, SLA and modSLA in the score plot were consistent with the PCA biplot shown in Fig. 6. In addition, in the loadings plot, CD86 expression and surface roughness (Ra) primarily contributed to PC1 and PC2, respectively, suggesting that roughness had little effect on CD86 expression, which was consistent with the experimental result. Furthermore, air-water contact angle (Theta), surface %C and %O were more associated with a mDC phenotype due to their clustering with phenotype variables that were up-regulated upon DC maturation (blue dotted ellipse in Fig. 7). Higher values of these surface characteristics were associated with PT and SLA substrates, which were shown to promote DC maturation. In contrast, surface %O and %Ti, which were higher on modSLA substrates, were on the opposite side of the phenotype variables (black dotted ellipse in Fig. 7), indicating that these surface properties tended to promote an iDC phenotype. Interestingly, air-water contact angle was strongly associated with IL-10 production, and %C and %N were similar in their effects on DC phenotype. Information from plots of PC1 and PC3 provided similar conclusions as PC1 and PC2, while plots formed by PC2 and PC3 resulted in meaningless covariations (data not shown).

4. Discussion

The phenotype of DCs was differentially modulated by PT, SLA and modSLA surfaces. Specifically, although the expression levels of DC maturation marker, CD83 and MHC class II molecule, HLA-DQ, were not altered significantly, PT and SLA treatment of DCs induced higher co-stimulatory molecule, CD86, expression relative to DCs cultured on TCPS (iDC control). DC treatment with modSLA did not affect CD86 expression as compared to iDCs, presumably promoting a non-inflammatory environment. Our previous experience indicates that CD86 is the most sensitive marker for DC response to biomaterial treatments and is a valid variable for determining DC maturation levels [16]. Furthermore, both PT- and SLA- treated DCs exhibited much more extensive dendritic processes, a morphology associated with mDCs. Consistent with the CD86 expression results, DCs treated with modSLA possessed a rounded morphology that is associated with iDCs. Therefore, PT or SLA promotes an mDC phenotype, whereas modSLA promotes an iDC phenotype. Despite the non-stimulating nature of modSLA substrates, DCs treated on modSLA were able to fully mature upon LPS challenge, indicating that modSLA does not suppress DC’s capability to respond to bacterial stimuli, an important aspect for clearance of any device-associated infection (data not shown).

PT and SLA surfaces have very similar surface chemical composition, but differ in average peak-to-valley roughness (Ra) and surface air-water contact angle [21]. Both of these surfaces are hydrophobic; hence, the most important difference lies in the surface roughness between PT and SLA substrates. The comparable levels of CD86 expression for DCs treated with PT or SLA surfaces suggested that surface roughness is not crucial in modulating DC phenotype. Conversely, modSLA surfaces have the same surface roughness as SLA substrates, but were prepared to retain their high surface energy (approximately 0° air-water contact angle) by preventing surface contamination with atmospheric hydrocarbons and carbonates. The results presented herein that modSLA-treated DCs were non-stimulating indicated the importance of surface hydrophilicity as a material property that modulates DC phenotype.

Surprisingly, despite the vast differences in surface energy and cellular responses, as many DCs adhered to modSLA substrates as to PT or SLA surfaces, indicating that cell adhesion alone is not sufficient in inducing DC maturation. Previous study demonstrated that distinct adsorbed ECM proteins on TCPS affected DC morphology, cytokine production, and allostimulatory capacity [36]. In addition, chemically-defined self-assembled monolayers were shown to present differential glycan profiles as well as induce distinct DC responses [37,38]. Therefore, the distinct DC responses induced by the Ti substrates were likely due to the differential protein adsorption profiles from the cell culture medium onto the Ti surfaces. Although the adsorbed proteins allowed similar extents of DC adhesion to the different Ti substrates, the difference in the presentation or conformation of these proteins presumably provided DCs with differential molecular patterns, resulting in distinct responses. This hypothesis will be tested in the future to understand which adsorbed protein profiles on the Ti substrates govern DC response. Specifically, it is necessary to understand the receptors and adsorbed matrix proteins critical for the modulation of DC responses to biomaterials.

In addition, DCs treated with Ti surfaces produced differential cytokine profiles. Contrary to the high expression level of CD86 and dendritic morphology, PT-treated DCs released higher amounts of anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1ra, compared to iDCs or modSLA-treated DCs. Although some trends in the release of TNF-α, IL-10 and MIP-1α were observed, the differences were not statistically significant, primarily due to the large variances in the cytokine production by individual donors. A wider array of cytokines and chemokines were subsequently analyzed in order to better delineate the cytokine responses upon DC treatment with Ti surfaces. Treatment of DCs with PT surfaces promoted enhanced production of the chemokine MCP-1, compared to iDCs, and to a level similar to LPS-treated mDCs. In addition, treatment of DCs with SLA surfaces induced higher levels of IL-16 production relative to iDCs or modSLA-treated DCs. The production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-12p70 and IL-18 induced by DC treatment with Ti substrates were low and not different among each other.

MCP-1 is a potent chemokine for monocytes and a variety of other immune cells such as activated CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells [39]. Furthermore, MCP-1 was released at high levels by osteoblasts in the bone with associated inflammation [40]. The elevated levels of MCP-1 production by DCs treated with PT surfaces are consistent with the enhanced expression of CD86 and mDC morphology observed for DCs treated with PT, indicating a pro-inflammatory DC phenotype. Counter-intuitively, IL-1ra production was also enhanced by PT surfaces. However, it is well-known that upon maturation, DCs naturally up-regulate the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines as a negative feedback [41]. Therefore, the up-regulated IL-1ra production by DC treated with PT surfaces was presumably initiated by the activated DCs to alleviate the pro-inflammatory response. In addition, DC treatment with SLA substrates increased the production of IL-16, which is a pleiotropic cytokine that can have both pro- and anti-inflammatory properties. IL-16 has been shown to be a chemoattractant for CD4 expressing peripheral immune cells, including CD4+ T cells, monocytes, eosinophils and DCs [42], and the elevated production of IL-16 was directly associated with airway inflammation [43]. In contrast, IL-16 was also demonstrated to inhibit mixed lymphocyte reaction by inhibiting TCR signaling [44], and that the administration of IL-16 reduced the RA symptoms in a murine model [45]. Therefore, the functions of IL-16 are likely dependent on the presence of surrounding cell types and cytokines in the microenvironment. Because of the mature phenotype suggested by the enhanced CD86 expression and dendritic morphology, SLA-treated DCs likely produce IL-16 as part of a pro-inflammatory response. It is also worthwhile to note that, despite the lack of statistical significance, DC treatment with SLA surfaces appeared to induce higher levels of IL-8 and MCP-1 production, supporting its pro-inflammatory phenotype. Collectively, the results indicate that treatment with PT or SLA surfaces promote a more mature phenotype of DCs, while treatment with modSLA surfaces maintains an iDC phenotype.

PCA was performed in order to draw correlations between DC phenotype and material properties of Ti surfaces from the multi-dimensional dataset. PCA was applied to the data in a blinded fashion to reduce the number of dimensions of the data, thereby facilitating the analysis of latent relationships. Consistent with the experimental data, PCA results suggest that PT and SLA surfaces were pro-inflammatory for DCs, while modSLA appeared to promote a non-inflammatory environment (Fig. 6). Furthermore, along with air-water contact angle, surface % C and N were associated with an mDC phenotype, and higher values of these surface characteristics were associated with PT and SLA substrates. In contrast, surface % O and % Ti contents were attributed to supporting a non-inflammatory DC phenotype and were detected at higher levels on modSLA surfaces. In addition, air-water contact angle was heavily associated with IL-10 production as compared to other surface material properties. The proximity of %C and N on the loadings plot indicated that their effects on DC phenotype were similar and presumably redundant. Taken together, PCA not only suggested possible material property–DC response relationships, but it also further supported the experimental results that PT and SLA surfaces are pro-inflammatory, while modSLA surfaces are non-inflammatory, for DCs.

Previous research demonstrated that the high surface energy and microtopography of modSLA surfaces synergistically enhanced the differentiation of osteoblasts and production of local osteogenic factors such as PGE2, TGF-β1 and osteocalcin [20]. In contrast to PT or SLA surfaces, the study herein showed that modSLA surfaces were able to promote a non-inflammatory environment by its non-stimulatory effect on DC phenotype, thereby reducing the innate immune response. Numerous studies have indicated the central role of DCs in osteo-immunology. Elevated numbers of DCs have been found in joints of RA patients [8,9] and have been attributed to the bone loss induced by inflammation [10]. Furthermore, human or mouse activated CD4+ T cells induced by environmental stimuli were shown to up-regulate RANKL, which supports osteoclast differentiation and activation. The over-activity of osteoclasts results in inflammation-induced bone loss [11,12]. Among APCs, DCs are the most potent in bridging innate to adaptive immunity by initiating and regulating T and B cell responses. Activation or maturation of DCs by environmental stimuli, including biomaterial treatments, was shown to induce T cell proliferation [46]. Hence, upon inflammation, DCs can become mature and initiate T cell activation, which can in turn promote the differentiation and survival of osteoclasts. Furthermore, PT-treated DCs were shown in this study to release elevated levels of MCP-1. MCP-1 was previously demonstrated to induce the formation of multinucleated osteoclast-like cells from human primary mononuclear precursors in vitro [47]. In another study, MCP-1 and RANKL synergistically promoted the differentiation of and fusion of mouse bone marrow cells into osteoclasts as well as enhanced the mineral dissolution in mouse bone marrow macrophage cultures on calcium phosphate disks [48]. In contrast, modSLA surfaces had little effects on the phenotype of DCs, maintaining an immature phenotype, evaluated by surface marker expression, morphology and cytokine profile. The ability of surface roughness and energy to induce osteogenesis and improve osseointegration is not only because of its effect on osteoblast and mesenchymal cells [24,25,29,49], but may also be due to its effect on the inflammation process. As a consequence, a non-inflammatory implant material such as modSLA is expected to promote osteoblast differentiation by suppressing local inflammation and associated osteoclast differentiation and to promote peri-implant formation clinically [26].

5. Conclusion

In this study, different clinical Ti surfaces were shown to induce differential DC phenotype upon treatment. DCs treated with PT or SLA surfaces exhibited a more mature phenotype, whereas DCs treated with modSLA surfaces maintained an immature phenotype. These results indicate another benefit of modSLA surfaces for promoting bone formation and integration by providing a local non-inflammatory environment. Furthermore, PCA indicated possible material property–DC phenotype relationships for Ti implant design. Specifically, increasing surface hydrophilicity, % O and %Ti may reduce the stimulating effects of Ti implants on DCs, potentially increasing anti-inflammatory effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Institut Straumann AG (Basel, Switzerland) for providing the Ti disks used in this study, Dr. Melissa L. Kemp of Georgia Institute of Technology for helpful discussion on PCA and critical review of the manuscript, and Dr. Manu O. Platt of Georgia Institute of Technology for access to the Simca P+ software. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants EB004633 (JEB) and AR052102 (BDB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Banchereau J, et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shortman K, Naik SH. Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:19–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immunity: lipoproteins take their toll on the host. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R879–R882. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trinchieri G, Sher A. Cooperation of toll-like receptor signals in innate immune defence. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:179–190. doi: 10.1038/nri2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matzinger P. The danger model: a renewed sense of self. Science. 2002;296:301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1071059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449:419–426. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zvaifler NJ, Steinman RM, Kaplan G, Lau LL, Rivelis M. Identification of immunostimulatory dendritic cells in the synovial effusions of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:789–800. doi: 10.1172/JCI112036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas R, MacDonald K, Pettit A, Cavanagh L, Padmanabha J, Zehntner S. Dendritic cells and the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:286–292. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page G, Miossec P. RANK and RANKL expression as markers of dendritic cell-t cell interactions in paired samples of rheumatoid synovium and lymph nodes. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2307–2312. doi: 10.1002/art.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong Y, et al. Activated T cells regulate bone loss and joint destruction in adjuvant arthritis through osteoprotegerin ligand. Nature. 1999;402:304–309. doi: 10.1038/46303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teng YT, et al. Functional human T-cell immunity and osteoprotegerin ligand control alveolar bone destruction in periodontal infection. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:R59–67. doi: 10.1172/jci10763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gravallese EM. Bone destruction in arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(Suppl 2):ii84–86. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.suppl_2.ii84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teng YA. The role of acquired immunity and periodontal disease progression. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:237–252. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taubman M, Kawai T. Involvement of T-lymphocytes in periodontal disease and in direct and indirect induction of bone resorption. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2001;12:125–135. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babensee JE, Paranjpe A. Differential levels of dendritic cell maturation on different biomaterials used in combination products. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;74A:503–510. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshida M, Babensee JE. Differential effects of agarose and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) on dendritic cell maturation. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;79A:393–408. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennewitz NL, Babensee JE. The effect of the physical form of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) carriers on the humoral immune response to co-delivered antigen. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2991–2999. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norton LW, Park J, Babensee JE. Biomaterial adjuvant effect is attenuated by anti-inflammatory drug delivery or material selection. J Control Release. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.032. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao G, Raines A, Wieland M, Schwartz Z, Boyan B. Requirement for both micron- and submicron scale structure for synergistic responses of osteoblasts to substrate surface energy and topography. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2821–2829. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao G, Schwartz Z, Wieland M, Rupp F, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Cochran DL, Boyan BD. High surface energy enhances cell response to titanium substrate microstructure. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;74A:49–58. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyan BD, Lossdörfer S, Wang L, Zhao G, Lohmann CH, Cochran DL, Schwartz Z. Osteoblasts generate an osteogenic microenvironment when grown on surfaces with rough microtopographies. Eur Cell Mater. 2003;6:22–27. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v006a03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin JY, et al. Effect of titanium surface roughness on proliferation, differentiation, and protein synthesis of human osteoblast-like cells (MG63) J Biomed Mater Res. 1995;29:389–401. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820290314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao G, Zinger O, Schwartz Z, Wieland M, Landolt D, Boyan BD. Osteoblast-like cells are sensitive to submicron-scale surface structure. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;17:258–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buser D, et al. Enhanced bone apposition to a chemically modified SLA titanium surface. J Dent Res. 2004;83:529–533. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bornstein MM, Hart CN, Halbritter SA, Morton D, Buser D. Early loading of nonsubmerged titanium implants with a chemically modified sand-blasted and acid-etched surface: 6-month results of a prospective case series study in the posterior mandible focusing on peri-implant crestal bone changes and implant stability quotient (ISQ) values. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2009;11:338–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2009.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bornstein MM, Wittneben J, Brägger U, Buser D. Early loading at 21 Days of non-submerged titanium implants with a chemically modified sandblasted and acid-etched surface: 3-year results of a prospective study in the posterior mandible. J Periodontol. 2010;81:809–818. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rupp F, Scheideler L, Olshanska N, Wild MD, Wieland M, Geis-Gerstorfer J. Enhancing surface free energy and hydrophilicity through chemical modification of microstructured titanium implant surfaces. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2006;76A:323–334. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz Z, Lohmann CH, Vocke AK, Sylvia VL, Cochran DL, Dean DD, Boyan BD. Osteoblast response to titanium surface roughness and 1alpha,25-(OH)2D3 is mediated through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;56:417–426. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20010905)56:3<417::aid-jbm1111>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romani N, et al. Proliferating dendritic cell progenitors in human blood. J Exp Med. 1994;180:83–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kou PM, Babensee JE. Validation of a high-throughput methodology to assess the effects of biomaterials on dendritic cell phenotype. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2621–2630. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babensee JE, De Boni U, Sefton MV. Morphological assessment of hepatoma cells (HepG2) microencapsulated in a HEMA-MMA copolymer with and without Matrigel. J Biomed Mater Res. 1992;26:1401–1418. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820261102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janes KA, Yaffe MB. Data-driven modelling of signal-transduction networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:820–828. doi: 10.1038/nrm2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albeck JG, MacBeath G, White FM, Sorger PK, Lauffenburger DA, Gaudet S. Collecting and organizing systematic sets of protein data. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:803–812. doi: 10.1038/nrm2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janes KA, Kelly JR, Gaudet S, Albeck JG, Sorger PK, Lauffenburger DA. Cue-signal-response analysis of TNF-induced apoptosis by partial least squares regression of dynamic multivariate data. J Comput Biol. 2004;11:544–561. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2004.11.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Acharya AP, Dolgova NV, Clare-Salzler MJ, Keselowsky BG. Adhesive substrate-modulation of adaptive immune responses. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4736–4750. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shankar SP, Chen II, Keselowsky BG, García AJ, Babensee JE. Profiles of carbohydrate ligands associated with adsorbed proteins on self-assembled monolayers of defined chemistries. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;92A:1329–1342. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shankar SP, Petrie TA, García AJ, Babensee JE. Dendritic cell responses to self-assembled monolayers of defined chemistries. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;92A:1487–1499. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rollins BJ. Chemokines. Blood. 1997;90:909–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahimi P, Wang CY, Stashenko P, Lee SK, Lorenzo JA, Graves DT. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression and monocyte recruitment in osseous inflammation in the mouse. Endocrinology. 1995;136:2752–2759. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.6.7750500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chi H, Barry SP, Roth RJ, Wu JJ, Jones EA, Bennett AM, Flavell RA. Dynamic regulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1) in innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2274–2279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510965103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cruikshank W, Kornfeld H, Center D. Interleukin-16. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:757–766. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hessel EM, et al. Involvement of IL-16 in the induction of airway hyper-responsiveness and up-regulation of IgE in a murine model of allergic asthma. J Immunol. 1998;160:2998–3005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Theodore A, Center D, Nicoll J, Fine G, Kornfeld H, Cruikshank W. CD4 ligand IL-16 inhibits the mixed lymphocyte reaction. J Immunol. 1996;157:1958–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klimiuk PA, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. IL-16 as an Anti-Inflammatory Cytokine in Rheumatoid Synovitis. J Immunol. 1999;162:4293–4299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshida M, Babensee JE. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) enhances maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;71A:45–54. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim MS, Day CJ, Selinger CI, Magno CL, Stephens SRJ, Morrison NA. MCP-1-induced human osteoclast-like cells are tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, NFATc1, and calcitonin receptor-positive but require receptor activator of NF3B ligand for bone resorption. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1274–1285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li X, Qin L, Bergenstock M, Bevelock LM, Novack DV, Partridge NC. Parathyroid hormone stimulates osteoblastic expression of MCP-1 to recruit and increase the fusion of pre/osteoclasts. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33098–33106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olivares-Navarrete R, Hyzy SL, Hutton DL, Erdman CP, Wieland M, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z. Direct and indirect effects of microstructured titanium substrates on the induction of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation towards the osteoblast lineage. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2728–2735. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]