Abstract

Objective

Modes of governance were compared in ten local mental health networks in diverse contexts (rural/urban and regionalized/non-regionalized) to clarify the governance processes that foster inter-organizational collaboration and the conditions that support them.

Methods

Case studies of ten local mental health networks were developed using qualitative methods of document review, semi-structured interviews and focus groups that incorporated provincial policy, network and organizational levels of analysis.

Results

Mental health networks adopted either a corporate structure, mutual adjustment or an alliance governance model. A corporate structure supported by regionalization offered the most direct means for local governance to attain inter-organizational collaboration. The likelihood that networks with an alliance model developed coordination processes depended on the presence of the following conditions: a moderate number of organizations, goal consensus and trust among the organizations, and network-level competencies. In the small and mid-sized urban networks where these conditions were met their alliance realized the inter-organizational collaboration sought. In the large urban and rural networks where these conditions were not met, externally brokered forms of network governance were required to support alliance based models.

Discussion

In metropolitan and rural networks with such shared forms of network governance as an alliance or voluntary mutual adjustment, external mediation by a regional or provincial authority was an important lever to foster inter-organizational collaboration.

Keywords: coordination, integration, mental health, networks, governance, continuity of care

Introduction

The shift of mental health care to the community [1–2] combined with the implementation of regional health authorities (RHAs) represents a significant component of health system restructuring [3–5]. Since the needs of persons with serious illness naturally extend beyond acute care to an array of health and social services, navigating the relevant supports can be a challenge. Services have been increasingly re-conceptualized to align with this reality. Limited coordination among service providers may place the continuity of care for those with serious illness at risk, contributing to a deterioration in health status, social functioning, re-hospitalization, and homelessness [6–11]. Publicly commissioned reports have found that coordination has not been sufficiently established to ensure the continuity of care needed to sustain persons with serious mental illness in the community [12, Section 3.03, p. 89] and to avoid preventable re-hospitalization [13–16] increasing the risk that the mistakes of previous movements of de-institutionalization may be repeated [11].

Mental health networks offer a means to develop a system of coordinated care for this higher needs sub-population. A network is a set of organizations and the relations among them that serve as channels through which communications, referrals and resources flow [17, 18]. The goal is to develop virtual ‘programs of care’ by coordinating primary, secondary, tertiary health and social services to simplify clients' access to them. Provincial health regions may include more than one network that operates among organizations with working relations. Governance is coordinated between a regional authority and a local network through their respective executive committees. Although the role of network governance in fostering inter-organizational cooperation is important, it is less well understood [16, 19–22]. The objective of our study was to analyze the instruments and levers of governance being used in mental health networks to foster inter-organizational cooperation. We do so by developing case studies of networks in regionalized/non-regionalized and rural/urban contexts to compare the governance strategies used and the extent to which their potential is context dependent [23, 24].

Network governance

Governance of networks in the health sector involves overseeing the collective action of public and private organizations contracted to provide public services to support a system of care. Its purview includes strategic direction, policy, management and use of resources to ensure accountability for health system performance [25]. As coordination is a measure of performance, accountability for it is assumed within a governance framework [26]. In Canada, regional health authorities were developed to enhance the level of service integration and coordination [27]. Networks are recognized as a mode of sub-regional governance, having developed within the cancer [28, 29], mental health [19, 30, 31], dementia [32], AIDS [33] and elderly chronic care sectors [34, 35] as vehicles to coordinate collective action and realize a systems approach [36]. “Although all networks comprise a range of interactions among participants, a focus on governance involves the use of institutions and structures of authority and collaboration to allocate resources and to coordinate and control joint action across the network as a whole” [37, p. 231]. As networks are based on cooperative endeavors, they do not have the same legal imperatives as organizations.

Coordination is complex as it involves translating policy into client-related activities mediated across numerous organizations. Organizations in a network must translate their values into a common vision, and negotiate who will provide which services and how to alleviate service gaps. As care shifts to the community prompts an environment of change that can represent a threat to organizations seeking to ensure their role in the system design; their activities can create an outcome different from the one intended [38, 39].

Theories of network governance

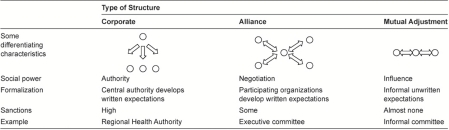

Organizational theorists identify inter-organizational coordination as a process that seeks to achieve unity of effort across service agencies and have proposed typologies to characterize the modes of local governance that foster coordination [20, 29, 36]. Provan and Kenis [37], for example, offer a model with nuanced refinements. As we sought to reflect the diversity of the Canadian context that incorporates networks with refined forms of governance and those at an early stage of development in which only select multi-collaborative inter-organizational relations exist and where dyad-based relations are common, we chose to adopt Whetten's [44] framework with three possible forms of coordination: mutual adjustment, alliance, and corporate structure (Table 1). Mutual adjustment is based largely on voluntary exchanges (e.g., client referral) between pairs of organizations, but no formal mechanism of coordination. A corporate structure involves an overarching formal authority that integrates management and care (e.g., through control of psychiatric hospitals and community mental health centers). An alliance involves autonomous agencies who form a coalition. The level of coordination is more formalized than in mutual adjustment, but the member agencies retain their autonomy. An alliance can form the basis for virtual integration [45] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Governance and coordination models

Adapted from Whetten [44].

Integration has also been distinguished as voluntary, mediated and directed based on the presence and role of a lead organization [46]. In voluntary integration, the lead agency is also a service provider; in mediated integration the lead agency's sole mission is to coordinate the services provided by other agencies; both voluntary and mediated integration can occur in an alliance structure. Directed integration occurs when one organization has the authority to mandate service coordination among agencies, which occurs in corporate structures.

Mental health networks also exist within a regional context that influences the incentives and forms of local governance and coordination. Models of regionalization range from devolution: the creation of sub-provincial units with revenue and expenditure authority (e.g., Alberta and New Brunswick); to deconcentration: the transfer of local administrative authority without political authority (e.g., Quebec); to delegation: the transfer of managerial responsibilities to regional offices (e.g., Ontario prior to the launch of local health integration networks) [47].

The type of regional and local network governance adopted creates a set of incentives that can influence the conditions that build inter-organizational solidarity or fragmentation [48, 49]. The challenge in governing networks is to determine the process that will lead organizations to engage in collective and mutually supportive action in which conflicts are addressed and network resources are used effectively and efficiently. An analysis of models of mental health system integration in the US found that while tight central control over integration through a core agency is likely to increase efficiency in providing services, it may inhibit voluntary cooperation and spontaneity, which is more likely to occur in decentralized networks in which multiple providers work together informally though a shared governance model, such as an alliance [42, 50]. Within decentralized structures, mediated systems were found to have leadership advantages over voluntary systems [46].

Current conceptualizations of networks [40, 41] would benefit from a greater understanding of the governance processes that foster inter-organizational coordination including a range of instruments from incentives to direct control. Provan and Kenis [37] theorize that four key structural and relational contingencies determine the effectiveness of shared governance: trust, size (number of participants), goal consensus, and the need for network-level competencies. As trust is less densely distributed among network organizations, the number of network partners increases, and less consensuses exists on network goals, they argue that brokered forms of network governance become more effective than shared governance.

An understanding of the contextual conditions under which a particular governance approach is likely to foster inter-organizational collaboration would refine current theoretical models. For example, in those contexts in which inter-organizational collaboration is predisposed to arise through such shared governance models as an alliance, are certain incentives, supports or strategies likely to foster their development? Our research explores the manner in which a range of network governance processes combine with local context (regionalized and non-regionalized). The intent is to clarify the conditions under which certain governance models and instruments are more likely to support coordination than others. By incorporating the three levels of analysis recognized as fundamental in assessing systems that rely on cooperation among these levels (community, network and organizational) [51], we clarify and compare the processes of network governance and discuss their implications for coordination through the lens of key informants.

Objectives

The first objective of this research was to compare the modes of network governance and coordination adopted in ten local mental health networks in rural/urban, regionalized/non-regionalized contexts. The second objective was to analyze key informants' insights on the extent to which the governance processes adopted facilitated inter-organizational collaboration within their local context.

Methodology

Ten local mental health network case studies were developed. To maximize variation and enhance generalizability, networks were purposively selected to include the following contexts: regionalized/non-regionalized provincial health authority; urban/rural; presence/absence of a psychiatric facility. The case studies were developed by incorporating the three units of analysis that Provan and Milward [50, 51] identify as necessary for network analysis: the community which is comprised of provincial program funders, the mental health network level, and the organizational level. The key informant approach has been used by network scholars to clarify the dimensions that underlie the processes of governance and coordination [33, 50, 51]. The case studies drew on provincial and network-level documents, and semi-structured key informant interviews with decision-makers and front-line managers. The interviews focused on the decision-makers' and managers' experience with the type of governance used in their network and their perspectives on the extent to which it supported the coordination of mental health services across organizations. A comparative framework categorizes the networks, and allows a discussion of the implications of the three types of governance processes for inter-organizational coordination given the different sets of contextual conditions [37].

Levels of analysis

The provincial policy level of analysis was informed by a document review of the grey and published literature and 32 semi-structured interviews with senior Ministry of Health or organization directors with oversight for mental health policy and services in Alberta, Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick. Network level focus groups involved 6–8 key informants. Organizational level data was collected through semi-structured interviews with eight urban or four rural front-line hospital and community service managers in each network. Network focus group and organizational key informants clarified the governance and inter-organizational process used to coordinate care and the extent to which the processes supported coordinated care in each network. Key informants' insights and perspectives on the strengths and weaknesses thus allowed a better understanding of the manner in which governance approaches influenced organizational coordination.

Selection of provinces, networks and key informants

Provinces were selected to include western (Alberta), central (Ontario and Quebec) and eastern (New Brunswick) Canada. Networks and provinces were purposively selected to include diverse contexts to increase generalizability: those with and without regional health authorities, those with and without access to a local psychiatric hospital, and those in rural, urban and metropolitan areas. Ten networks agreed to participate, whose geographic area is categorized as rural or urban: large (>1 million); midsize (>500,000–1 million); and small (<500,000) anonymously labeled A–J (Table 2). Three networks that declined to participate were in transition undergoing changes in their senior management and organizational structure. For the network level focus group, the provincial Ministry of Health identified local mental health leaders and senior directors who were invited to participate in the focus groups. For the organizational level key informants, senior directors in the network identified front-line service managers to serve as key informants.

Table 2.

Provincial and regional governance context

| Size | Province | Jurisdiction for mental health | Local authority | Single regional board | Psychiatric hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | |||||

| A | Ontario | Provincial | Delegated1 | No | No |

| B | Alberta | Regional | Devolved2 | Yes | Yes |

| Small urban | |||||

| C | New Brunswick | Regional | Devolved2 | Yes | Yes |

| Mid-sized urban | |||||

| D | Quebec | Sub-regional | Deconcentrated3 | No | No |

| E | Quebec | Sub-regional | Deconcentrated3 | No | Yes |

| F | Ontario | Provincial | Delegated1 | No | Yes |

| Large urban | |||||

| G | Quebec | Sub-regional | Deconcentrated3 | No | Yes |

| H | Ontario | Provincial | Delegated1 | No | Yes |

| I | Ontario | Provincial | Delegated1 | No | Yes |

| J | Alberta | Regional | Devolved2 | Yes | No |

MH, Mental Health.

1Delegated to Regional Ministry office.

2Devolved to Regional Health Authority.

3Deconcentrated to ‘Table de concertation’.

Data collection

The review of government documents occurred first to provide a context for the key informant interviews which elaborated on provincial policies. Provincial level semi-structured interviews gathered data on government ministry coordination for inter-sectoral services (e.g., housing, justice services), and on community and institutional service funding models. Network level data was collected through a focus group with senior mental health directors in each network. Network and organizational level key informants described the governance and inter-organizational processes used to coordinate care. Key informants were asked to indicate the extent to which these processes supported coordinated care. In all 96 key informants participated in the research from 2003 to 2006. A secondary analysis of Fleury's [52] data informed the analysis of three networks in Quebec.

Data organization and analysis

The analysis of government reports occurred first, followed by key informant interview transcripts. Each taped interview was transcribed and checked to identify omissions or errors and to identify concepts that the key informants used to capture what they said. Data were analyzed by applying content analysis in which a codebook was used to guide the identification of common words, phrases, and characteristics among responses and condense the data [53]. Relationships among the responses of key informants within and across networks were organized into the following higher-level themes: network governance, inter-organizational collaboration; budget authority and service planning; incentives and authority to collaborate, hospital links to community care and social services (addictions, justice, employment and housing programs); joint programs; leadership; system wide objectives; and centralized access [54, 55]. Two members of the research team validated the emergent themes through triangulation and convergence among responses. The results are presented according to community, network, and organization-level themes, that include key informants' perspectives on the implications of their local model for coordinated care. Features of network governance are categorized and compared based on the framework in Table 1 and network type.

Results

Authority for mental health care

Jurisdiction for mental health services resided at the provincial (Ontario), regional (Alberta, New Brunswick) and sub-regional (Quebec) levels (Table 2). While the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) was responsible for mental health policy, local administration was transferred to the seven regional offices of the Health Services Management Division that were not responsible for operations, referred to as delegation. In Alberta and New Brunswick, authority for mental health was devolved to Regional Health Authorities (RHAs) in a phased manner from a provincial Mental Health Board in 2002.1 Key informants addressed how the shift in governance affected service coordination. In Quebec, the sub-regional ‘table de concertation’ offered mental health organizations a forum to discuss service coordination, referred to as deconcentration (transfer of local administrative authority without political authority) [47]. Although Quebec is regionalized, psychiatric hospital boards remain, allowing them to exercise more autonomy than in other regionalized provinces.

Mental health networks

Local mental health networks adopted one of three approaches to govern inter-organizational collaboration: corporate structure, mutual adjustment or alliance (Table 3) [44]. In regionalized provinces, Regional Health Authorities (RHAs) integrated organizations' boards through a corporate structure to support coordination of hospital and community mental health services. In Alberta and New Brunswick, authority for mental health was devolved to Regional Health Authorities in a phased manner from a provincial Mental Health Board in 2002. The Alberta and New Brunswick mental health networks thus implemented a corporate structure only after this form of governance was already in place for other health care services (Networks B, C, J). We found the two most coordinated networks adopted corporate-governed models (Networks C and J). In corporate-governed Network B conversely, key informants noted that inter-organizational collaboration had not progressed. To address this, the external provincial mental health board used the governance instrument of appointing a director to oversee both hospital and community services, who struck committees comprised of representatives from both sectors to initiate coordination. While such governance is directed [20, 46] key informants noted it was mediated locally through the committees formed.

Table 3.

Governance models

| Size | Province | Jurisdiction for mental health | Budget authority | Network governance model | Network governance mechanism | Social power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | ||||||

| A | Ontario | Provincial: Delegated1 | Provincial | Mutual adjustment | Executive Commitee2 | Influence |

| B | Alberta | Regional: Devolved | Regional | Corporate | Executive Committee3 | Authority |

| Small urban | ||||||

| C | New Brunswick | Regional: Devolved | Mental Health Network | Corporate | Executive Committee | Authority |

| Mid-size urban | ||||||

| D | Quebec | Sub-regional: Deconcentrated | Regional | Alliance | Table de concertation | Negotiation |

| E | Quebec | Sub-regional: Deconcentrated | Regional | Alliance | Table de concertation | Negotiation |

| F | Ontario | Provincial: Delegated1 | Provincial | Alliance | Executive Committee | Negotiation |

| Large urban | ||||||

| G | Quebec | Sub-regional: Deconcentrated | Regional | Mutual adjustment | Table de concertation | Influence |

| H | Ontario | Provincial: Delegated1 | Provincial | Mutual adjustment | None | Influence |

| I | Ontario | Provincial: Delegated1 | Provincial | Mutual adjustment | None | Influence |

| J | Alberta | Regional: Devolved | Regional | Corporate | Executive Committee | Authority |

1Delegated to the Ministry regional office.

2An executive committee functions at a sub-network level. Network A: Community services only; Network H: Centralized case management services only.

3In addition to the Executive Team, governance occurred through an Integration Steering Committee, several Integrated Service Teams, and a Joint Director responsible for all mental health services, a position that was put in place prior to the transferred of authority for mental health services to the Regional Health Authority.

In the small and mid-size urban networks (Networks D, E, F), governance occurred through an alliance of organizations which formed an executive team that mediated service coordination. The governing alliances in Networks D and E were initiated through their respective ‘tables de concertation’. While more formalized than in mutual adjustment, organizations retained their autonomy. The alliance in Network F evolved from its ‘Addictions and Mental Health Executive Committee,’ which mediated governance to coordinate services. The alliance in Network C also made significant progress prior to the devolution of mental health to the Regional Health Authority. The small and mid-size urban networks would appear to offer the best conditions for an alliance model to function: developing working relationships among a smaller number of organizations was most feasible and fostered a stronger sense of accountability to the network.

Among the large urban networks, key informants in Network J indicated the highest level of coordination. Network J's corporate governance and integrated management supported the greatest unity of effort by mediating collaborative interactions among organizations. And while its network lacked a psychiatric facility which limited access to tertiary care beds, its executive team ensured planning across general hospitals was coordinated. As resources were not embedded in an institutional model, programs could more easily change course, such as introducing centralized access to care. Moreover, union contracts did not prevent shifting care to the community.

In Ontario's large urban networks, the governance model adopted was mutual adjustment. Coordination was through voluntary exchange, such as client referral, without formal coordination mechanisms. Financial incentives through the ‘Community Investment Fund’ of the mid-to-late 1990s were the main instruments: programs that sought to expand required a memorandum of understanding with the other organizations in their network to coordinate services, which hastened inter-organizational cooperation across the province [56]. The Ministry however mediated coordination for Assertive Community Treatment forensic teams, and the implementation of Community Treatment Orders2 in Networks H and I.

In metropolitan networks, mutual adjustment was thus the predominant means of coordination. Key informants in these networks conveyed the challenges for persons with a psychiatric disability:

“If you are a consumer, or a family member, you have no way of knowing how to get access to case management or Assertive Community Treatment services. There are…14 agencies that provide those services…14 phone numbers, 14 application forms, it's a nightmare. Every planning document that has been developed in the last 20 years has said coordinated access…our current initiative was born out of a network of mental health services”.

– Network H, Key Informant 4

Coordinating care between a psychiatric hospital and community services was often difficult to achieve, unless discharge planning processes—such as a liaison nurse based in the community—supported coordination. When a psychiatric hospital was present its involvement in network governance was pivotal to ensuring coordination processes were in place.

“The vast majority of mental health programs had staff from the former psychiatric hospital working in them …so that really helped to bridge the gap between the tertiary hospital and the general hospital, tertiary hospital and community mental health program and there are a number of community mental health programs that probably wouldn't have got off the ground or thrived without the ongoing support of the psychiatric hospital. So I think that is a really important part of the infrastructure of collaboration”.

– Network F, Key Informant 7

Developing an alliance required the involvement of all mental health organizations. When psychiatric hospitals were managed by provincial governments (e.g., Ontario, Alberta), their wide catchment area made it difficult for them to engage in local planning. In rural Network A for example, community providers found it challenging to coordinate care when their clients were admitted to a general or psychiatric hospital outside their network.

“So, there will be times when we'll send a client in, and send follow-ups, we'll call, and we'll be informed that the client has been discharged and we haven't received a single word…discharge planning is extremely ad hoc…there isn't coordinated care within the community with the schedule ones. Because you transfer, and they deal with it…and you get a discharge summary, if you get one, because they generally only send them to the family GPs who don't send them to us, because they assume we work with them. But if you get that it's usually within a couple of weeks. That's a gap in service”.

– Network A, Key Informant 1

Without a governance forum, community organizations were unable to develop coordination mechanisms with the psychiatric hospital to which their patients were admitted; discharge referral arrangements were not established, which led to lapsed care. In Quebec, most psychiatric hospitals play a leadership role at the local level because they offer specialized care and emergency psychiatric services. At the same time, these organizations were not always accountable for ensuring a seamless transition across the continuum of care. Conversely, corporate-governed networks in regionalized provinces were held accountable for ensuring mental health service coordination. A key governance lever in corporate-governed networks was to implement a central intake registry in which all organizations were required to participate to coordinate service access (Networks C, J).

Aligning budget authority with service planning

As governance includes oversight for resources, we examined the extent to which the governance of mental health networks included authority over the network budget and service planning. We found these roles were divided among provincial, regional and local levels in the networks studied. Key informants in networks whose authority included both budget allocation and service planning indicated this alignment supported their governance capacity to prompt inter-organizational cooperation (Network C, KIs 5, 7). Conversely, we found network governance was less well supported when the province set organizational budgets while networks oversaw service planning, as networks lacked a key governance lever (Network A, KIs 3, 4; Network G, KIs 1, 2, 6, 7). Such misalignment was most evident when mental health services were planned by the network, while secondary and tertiary facilities were funded by and reported to the province. The divided authority meant hospitals were not held accountable when their care was not coordinated with community-based organizations (Networks A, H, I). Coordination did not always occur without formal processes or incentives to encourage hospitals to align their care with community organizations.

While the ‘table de concertation’ in Networks D, E and G offered a forum to discuss service needs and local plans, not all networks achieved consensus. Even though the Ministry requested organizations to coordinate their care, they were not accountable to their network; such ambiguity weakened the efforts of networks whose governance was based on mutual adjustment.

Key informants indicated network governance was most supported when mental health planning and budget decisions resided at the regional or network level (Networks B, C, J). Regions with integrated financial management were also more likely to emphasize the goals of the system which fostered innovation and facilitated resource re-allocation to needed areas (Networks C, J). Conversely, we found provincial control over network budgets was less likely to support network governance due to lack of local insight and an inability to foster a shared network vision. Instead provincial budget control tended to address the goals of individual organizations.

Leadership

In alliance- and corporate-governed small and mid-sized networks, governance occurred through organizational leaders' vision and accountability to address service access on behalf of their population. In these networks, a team of network organizations' executives assessed needs, achieved consensus on resource allocation and made decisions to foster strategic alliances that drew on the strengths of their organizations (Networks C, F). We found leadership ‘buy-in’ was important to ensure a network was strategically aligned and resources were reallocated to promote coordination (Network F, Key Informant 2). Organizations that contributed to the governance of the network affected buy-in concerning the network's strategic direction, hence the importance of involving key organizational leaders. Network strategy and decision-making was guided by leaders' insights on how to alleviate ‘upstream’ problems. Consensus on strategic direction was also most likely when it responded to a recognized need and was based on trust. Government key informants and executives in several networks emphasized the importance of trust as directors build a network. Several indicated the need to maintain a flexible vision of how their organization will contribute and trust their counterparts will reciprocate to address population needs.

System wide objectives

Several networks developed system wide goals. In Network C, working groups addressed such issues as: network mandate, access, education, and partnering to support the development of system wide goals. A ‘Communities of Practice’ approach addressed administrative, structural, and clinical integration issues.

“The goals and operational plan is to have representation from across the region to address issues of integration, and we are doing that. And it's a joint plan between community and hospital.”

– Network C, Focus group member

While organizations in all networks engaged in performance review, organization-specific as opposed to system measures were often applied which could promote unit over system goals. Conversely, key informants in Network C which engaged in network planning and developed system goals and performance measures indicated their network was working toward several of its system objectives. “That's where we are right now, developing a practice, on a much more consistent basis.” Network C, Focus group member.

Fostering sub-networks: addictions, justice and housing programs

Inclusion of addictions and justice services within a governance framework is important as a large proportion of persons with a psychiatric history have a concurrent substance use disorder (20–50%) [57] or are associated with the law and inappropriately incarcerated. As housing programs can be a primary community service provider (liaising with mental health case managers and medical care on behalf of their residents as needed), they are important to include. Provincial level governance led the Ministries of Health and Community and Social Services to develop guidelines for collaboration among relevant government divisions. Once a provincial framework was established, inter-sectoral collaboration was found to function most effectively through local sub-networks of relevant organizations, with greater opportunity to discuss common concerns and resolve them [56].

Several networks aligned their governance to include mental health and addiction programs (A, C, F, I), or justice and mental health systems (C, E, I and J). An important governance strategy was thus to foster the formation of sub-networks which addressed the needs of a sub-population, such as the homeless, or a program, such as the implementation of Community Treatment Orders where case management programs coordinate their services with 11 hospitals in Networks H and I, reflecting a mediated sub-network that operates similar to an alliance. In networks without an alliance, sub-networks that address such areas as court-diversion or case management were found to fulfill a similar role.

Centralized access

Centralized access directs a person to care when their intake assessment demonstrates the need. Networks B, C and J used a centralized intake system/registry that offered a single point of referral to a comprehensive set of mental health services. Networks D and E coordinated primary health and community services, while Network H offered centralized access to case management. Alternatively, Networks A, B and F offered central intake for community supports. Community organizations experienced mixed success in facilitating access to psychiatrists.

In rural Network A, the Community Mental Health Centre (CMHC) offered a single point of entry to community mental health services (Assertive Community Treatment, mobile teams, case management, counseling, and crisis care). The CMHC coordinated with social services (children's, police, justice, addictions, women's shelters, housing and employment), but was unable to coordinate with the general and psychiatric hospital to which persons in their network were referred. In Quebec Networks D and E, the local community health centers (CSSSs) offered centralized access to mental health programs and services.

Governance strategies to attain coordination

In networks whose key informants indicated progress was made in coordinating services, the predominant governance model was a network executive committee with representation from local organizations through which consensus was attained and decisions were made (Networks B, C, E, F and J). Network C's executive team viewed its mandate as an opportunity to develop more comprehensive and integrated services; subcommittees ensured its decisions were operationalized through coordinated action plans.

“System wide goals and priorities are in our operational plan—plus we've got four working groups that are presently off working together to identify goals and service co-ordination, and recommendations will be put forth towards those areas, of which we will be working towards for the next three years”.

– Network C, Focus group key informant

In rural Network B in which limited coordination occurred, the provincial mental health board used its governance authority to appoint a joint director for both institutional and community-based mental health services, who formed executive, and integration steering committees and service teams which prompted region-wide planning, as opposed to within separate communities (Network B). After jurisdiction for mental health services was transferred to Regional Health Authorities in Alberta and a local network executive committee was formed, key informants emphasized relationships among organizations were more fully developed, and coordination was more effective, replacing previous informal communication (Networks B and J):

“…the integration is much smoother—previously we were a number of silos doing our own thing and keeping our own population, and not communicating perhaps as well as we should have…managers coordinate conversations… we're over a number of services now…a number of community agencies meet on a regular basis and identify gaps that we present to the region”.

– Network J, Key informant 5

Where regional health authorities were not present, networks developed on an ad-hoc basis. In large urban Network H for example, an overarching network did not exist; instead individual organizations developed informal agreements to work together to extend their range of services:

“I don't think we have a network at this point…each agency relates to the funder, which is in our case the Ministry of Health, on a separate basis, so we don't have a lead agency model…it's really each agency looking at the client group they are serving and based on that, identifying gaps and talking to the Ministry…there are lots of partnerships, voluntary in terms of partnering with housing providers…”

– Network H, Key Informant 6

The absence of local governance through an executive forum in rural Network A was noted by key informants as preventing the development of processes to support continuity of care. Conversely, the presence of governance through an executive forum in rural Network B made it possible to advance a shared understanding of system goals, agree on service providers' roles, coordinate supports and develop performance measures.

Changing role of hospitals

Psychiatric hospitals have been reconfigured as part of restructuring and have different roles, including specialized care (psychosis, treatment resistance, early intervention, forensic care). In Ontario, tertiary facilities were re-organized and divested, such that new relationships needed to be established.

“Services in the hospitals have been resorted and restructured, and moved around without any consultation. And the community finds out in retrospect…When they change internally… internal communication is almost non-existent. It makes it very difficult”.

– Network A, Key Informant 1

“We used to have a fairly good relationship with—mental health centre. Since the merger…it has created more barriers for us; it has made it more difficult for us to communicate with a larger institution”.

– Network I, Key Informant 3

Psychiatric hospitals experience difficulties coordinating their services with those of the other organizations in their network for a variety of reasons.

“There has been a cultural shift, I think, towards working with the community... that takes a generation…I think it shows that there still is, and will continue to be some battling going on, for, you know, what is our hospital going to look like at the end of the day?”

– Network H, Focus group key informant

Orienting providers in psychiatric facilities to connect with community programs remains a challenge, as the Director of a community housing facility in Network I indicated:

“Whenever we have clients that go into hospital we're on the phone to the primary caregiver the next day begging to be involved in the process. We invariably get ignored by the psychiatric hospital…If we take somebody into hospital invariably we're sitting there and ignored for 10 hours…when I only have one staff to deal with 37 people…but the client needs it…We may have maybe two hospitalizations a year…”

– Network I, Key Informant 5

“We need to link the services better between community and facility, and not have this disconnect, that we need to become a continuous service.”

– Network B, Key Informant 2

General hospitals are becoming more responsive in coordinating their care. Key informants in large urban centers indicated the general hospitals seem to be reaching out to make the connection to community service providers, where their case management, inpatient, emergency services, and their mobile crisis team are ‘doing a great job.’

“…emergency services is…making it possible for you to take your mental health clients to emergency and be seen by a psychiatrist first and not go through the medical stream and then wait for the consultation, because most of our folks…need crisis intervention”.

– Network I, Key Informant 5

“Three years ago there was minimal coordination between the psychiatric inpatient units and community care; in the last year and a half this has improved 25–35%.”

– Network J, Key Informant 4

Coordination of care between general hospitals and community organizations thus varies, and is improving as hospitals' role in the system adjusts to the current reality: community-based organizations serve an important role in re-integrating in-patients into the community. As hospitals are at capacity, developing linkages with community programs that support persons being discharged would reduce demand on their services. Community programs are however often at capacity, and their waiting lists can prevent patients from accessing these supports.

The challenge is how to include psychiatric hospitals within local governance when many operate as autonomous organizations. The networks in which psychiatric hospitals participated in local governance were in rural and mid-sized urban areas (Networks B, E and F). In the corporate-governed rural network, the provincial mental health board used its authority to appoint a network-wide director as a key governance instrument. Under the director's leadership, the psychiatric hospital's executive was brought into the network planning process. For the mid-sized urban networks that adopted the alliance model, the psychiatric hospital participated in the executive leadership team. We found that involving psychiatric hospitals in the governance of the network and development of coordination strategies had a profound effect on continuity of care. A governance instrument that two mid-sized urban networks used was to shift downsized psychiatric hospital staff to community organizations which increased hospital-community coordination.

Discussion

We found the type of network governance model adopted affected organizations' unity of effort to coordinate services among diverse providers. Several governance strategies were particularly supportive. While the corporate model advanced organizational cooperation most directly, the appointment of a director with jurisdiction for institutional and community services, who formed an executive committee with representation from both sectors was key. Integration through a Regional Health Authority was however not the sole means to coordinate services. The small and mid-size urban network's (Networks C, D, E and F) alliance executive team aligned programs and re-allocated resources to address community needs.

Where Provan and Kenis' [37] conditions of distribution of trust among network organizations, a moderate number of organizations, goal consensus and network level competencies were present—as occurred in the small and mid-sized urban networks (Networks C, D, E and F)—key informants emphasized their progress. Their alliance-governed networks' executive team made strategic decisions that reallocated network financial and human resources to align programs and address community needs. Key informants in these networks stressed their executive team and sub-network committees were instrumental in developing a shared vision and aligned organizations' contributions. They also instilled a sense of shared accountability toward the population served. Our findings suggest the conditions in the small and mid-sized urban networks of having a reasonable number of organizations on whom care depends, can make coordination and re-deployment of staff and resources to address population needs most feasible. Durbin et al. [30] found other small urban Ontario networks (excluded from the current study) achieved significant coordination in the absence of a regional health authority.

Sub-networks in the metropolitans studied which met the conditions of trust, goal consensus, a moderate number of organizations and network level competencies also achieved inter-organizational collaboration. A mediated sub-network in Networks H and I offers an example: Community Treatment Orders were implemented through cooperation among community case management organizations and 11 hospitals that link and coordinate case management services.

Governance of metropolitan networks overall faced more complex challenges. First, maintaining dialogue among a multitude of organizations was more difficult. Although a ‘table de concertation’ existed in Network G for example, the number of organizations involved made it difficult to develop effective working relationships. As the ‘table de concertation’ was not sufficiently resourced to allow its members to engage in the process needed to develop a common vision—a complex exercise given the numerous stakeholders with diverse cultural and philosophical perspectives—divergent views remained; goal consensus and trust were not present. Hence, the conditions of moderate size, goal consensus and trust were not met, eventhough network level competencies were available [37]. While the size and level of resources within the large urban networks differed, the findings were consistent across them: metropolitan networks that relied on voluntary mutual adjustment were unlikely to achieve coordinated care. This finding thus confirms Provan and Kenis' theory that the fewer of the key conditions present, the more likely the need for externally brokered forms of governance.

Key informants also indicated the presence of a psychiatric facility within a network could make coordination more complex (B, E, F, G and I). Shortell et al. suggests that overly large organizations are not conducive to community building: their size, diverse programs and services make it possible for them to disengage from community building exercises. A focus on individuality can also lead communal exercises to bring out protectionist tendencies, and become a forum for organizations to advance their professional identity. Conversely, a sense of community emerges when organizations develop a capacity for vulnerability in which they recognize that fostering links to the community—where patients must re-build their lives—ensures their place in the system design by supporting continuity of care and the most efficient use of resources [42].

In the metropolitan networks with a psychiatric facility we studied, trust among organizations and a commitment to coordination was often weak, especially when not reinforced through an executive forum. Under these conditions, with no common vision and few incentives to foster cooperation there was an absence of strategic or operational plans. Metropolitan networks thus experienced a three-fold challenge: the large number of organizations made efforts to coordinate care more difficult, especially where trust among organizations was weak, and without consensus on goals. To support network governance in metropolitans, externally brokered or mediated forms of governance are needed, along with incentives for inter-organizational cooperation. Among the networks with a psychiatric facility in our study, we found the mid-sized urban networks that possessed the predisposing governance conditions of trust, goal consensus, a moderate number of organizations and network level competencies achieved most coordination.

Conclusion

In Alberta and New Brunswick, the mandate of regionalization was to coordinate care which created incentives for local networks to form. In many cases this external incentive was sufficient to prompt the development of local network governance (Networks C, J). Instead of appointing an external board of directors—as occurs for private sector organizations—the mental health networks studied were governed by a committee of network organizations' executive directors. Under this form of ‘shared governance’ the collectivity of partners made all the decisions and managed network activities. In the four small to mid-sized urban networks (C, D, E and F) the conditions of: trust, moderate number of network participants, goal consensus and network level competencies allowed their alliance-based network governance to foster the inter-organizational collaboration sought [37].

Local network governance was at the same time overseen by either a Regional Health Authority or a provincial Mental Health Board or government, which in some cases exerted external governance instruments when coordination did not occur through local network governance. Levers of external governance were necessary when the conditions required to for shared governance to function well were not present. In the two rural networks (A, B) for example, the absence of trust and goal consensus among organizations formed less than ideal conditions for local governance. In Network B, the provincial Mental Health Board brokered local governance by appointing a director of mental health across the continuum of care to. In Network A, such external brokerage did not occur. In large urban networks the challenge was even greater, given the multitude of organizations combined with an absence of trust and goal consensus. In large urban networks that were governed through mutual adjustment (G, H, I), such external brokerage was needed to foster a more cohesive form of local governance. Conversely, the corporate structure form of governance in large urban Network J, with its external oversight by a regional authority, led to the inter-organizational collaboration sought.

In all contexts, challenges occurred as care shifted from hospitals to the community and prompted adjustments in organizational roles and relationships. In Ontario, the incentives associated with the Community Investment Fund prompted inter-organizational collaboration even in the absence of a regional authority: while the small and mid-sized urban networks began to develop, less progress was made in the rural and metropolitan networks without an executive committee, even as sub-networks formed within them. A similar pattern was found in Quebec, where the mid-sized urban areas established forms of mediated governance while the metropolitan networks faced greater challenges. A common vision and relationships of mutual trust and cooperation were more difficult to establish among a multitude of organizations whose stakeholders had diverse cultural and philosophical perspectives, and where community organizations and hospitals may not have had prior working relationships. Metropolitan networks that relied on voluntary mutual adjustment, without external oversight from a regional or provincial authority thus lacked a key lever for coordination. While the organizational relationships needed to establish a systems approach may not have been necessary in the past, as the community becomes the locus of care, they are fundamental to supporting continuous care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, and the Canadian Mental Health Association for their support for the project. We are also grateful to Dr. Paula Goering for her suggestions on earlier versions of the paper and to the numerous key informants who shared their insights.

Footnotes

In April 2009, since the study ended, Alberta consolidated its 12 health regional authorities to form Alberta Health Services. New Brunswick's eight regional health authorities were amalgamated into two new health authorities in September 2008.

Legislation for Community Treatment Orders was passed in Ontario in 2000. CTOs are issued by a certified physician to enable them to provide a person with community-based treatment or care and supervision that is less restrictive than being detained in a hospital. CTOs are for individuals who suffer from serious mental disorders, who have a history of repeated hospitalizations and who meet the committal criteria defined in the Mental Health Act, and involuntary psychiatric patients who agree to a treatment/supervision plan as a condition of their release from a psychiatric facility to the community.

Contributor Information

Mary E Wiktorowicz, Chair and Associate Professor, School of Health Policy and Management, York University, 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, Ontario M3J 1P3, Canada.

Marie-Josée Fleury, Professeur Adjoint, Département de Psychiatrie, Université McGill, 845 Sherbrooke St. W. Montreal, Quebec H3A 2T5, Canada.

Carol E Adair, Adjunct Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, 3330 Hospital Drive NW, Calgary, Alberta T2N 4N1, Canada.

Alain Lesage, Department of Psychiatry, Université de Montréal, Associate scientific director, Fernand-Seguin Research Center, L-H Lafontaine Hospital, Montréal, Québec H1N 3M5, Canada.

Elliot Goldner, Faculty of Health Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver campus, HC 2400 515 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC V6B 5K3, Canada.

Suzanne Peters, Doctoral Candidate, Department of Sociology, York University, 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, Ontario M3J 1P3, Canada.

Reviewers

Juan E. Mezzich, (1) President, International Network for Person Centered Medicine; (2) Professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York University, New York

Ivy Lynn Bourgeault, PhD, (1) Professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Ottawa, Health Science Programme, (2) Associate Director of the Community Health Research Unit, University of Ottawa, Canada

One anonymous reviewer

References

- 1.Ontario Ministry of Health. Making it happen: implementation plan for the reformed mental health system. Toronto, Ontario: Integrated Policy and Planning Division; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberta Ministry of Health. Working in partnership: building a better future for mental health. Final Report of the Mental Health Strategic Planning Committee. Edmonton, Alberta: Government of Alberta; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberta Ministry of Health. Creating a better future—action plan and business plans. Provincial Mental Health Advisory Board 1997-1998 to 1999-2000. Edmonton, Alberta: Government of Alberta; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mhatre S, Deber B. From equal access to health care to equitable access to health: a review of Canadian Provincial Health Commissions and Reports. International Journal of Health Services. 1992;22(4):645–68. doi: 10.2190/UT6U-XDU0-VBQ6-K11E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rochefort DA. More lessons, of a different kind: Canadian mental health policy in comparative perspective. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1992;43(11):1083–90. doi: 10.1176/ps.43.11.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorvil H. Reform and reshaping mental health services in the Montreal area. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1997;43(3):164–74. doi: 10.1177/002076409704300302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassuk EL, Gerson S. Deinstitutionalization and mental health services. Scientific American. 1978;238(2):46–53. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0278-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein L, Test M. Alternatives to mental hospital treatment: I. Conceptual model, treatment program and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1980;37(4):392–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780170034003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabriel A. Reducing the length of stay in a psychiatric inpatient unit and providing community care as an alternative. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;42(1):87. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pemberton K. Mental homes wretched, lobby group says. Vancouver Sun March 9, 1989; p. A1, A16.

- 11.Simmons H. Unbalanced: mental health policy in Ontario, 1930-1989. Toronto: Wall and Thomson; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario auditor general report. Toronto, Ontario: Government of Ontario; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adair CE, McDougall GM, Mitton CR, Joyce AS, Wild TC, Gordon A, et al. Continuity of care and health outcomes among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(9):1061–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitton CR, Adair CE, McDougall GM, Marcoux G. Continuity of care and health care costs among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(9):1070–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adair CE, McDougall GM, Beckie A, Joyce A, Mitton C, Wild CT, et al. History and measurement of continuity of care in mental health services and evidence of its role in outcomes. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(10):1351–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.10.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joyce AS, Wild TC, Adair CE, McDougall GM, Gordon A, Costigan N, et al. Continuity of care in mental health services: toward clarifying the construct. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;49(8):539–50. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alba RD. Taking stock of network analysis: A decade's results. In: Bachrach S, editor. Research in the sociology of organizations (Vol. 1) Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1982. p. 39–76. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reburn F. Human services integration. Public Administration Review. 1977;37:264–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durbin J, Goering P, Steiner D, Pink G. Does system integration affect continuity of care? Admin Policy Mental Health and Mental Health Service Research. 2006;33:705–17. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Provan KG, Sebastian JG, Milward HB. Interorganizational cooperation in community mental health: a resource-based explanation of referrals and case coordination. Medical Care Research Review. 1996;53:94–119. doi: 10.1177/107755879605300105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bazzoli G, Shortell S, Dubbs N, Chan C, Kralovec P. A taxonomy of health networks and systems: bringing order out of chaos. Health Services Research. 1999;33(6):1683–717. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolland JM, Wilson JV. Three faces of integrative coordination: a model of interorganizational relations in community based health and human services. Health Services Research. 1994;29:341–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleury M-J, Mercier C. Integrated local networks as a model for organizing mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2002;36:55–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1021227600823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott WR, Black BL. Organizations and mental health. In: Scott WR, Black BL, editors. The organization of mental health services: societal and community systems. Beverly Hills, California: Sage; 1986. p. 7–12. [Sage Focus editions volume 78] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prakash A, Hart JH. Globalization and governance: an introduction. In: Prakash A, Hart JH, editors. Globalization and governance. London: Routledge; 1999. p. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woods KJ. A critical appraisal of accountability structures in integrated health care systems 2002. Glasgow, Scotland: Scottish Executive Health Department Review of Management and Decision Making in NHS Scotland; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lomas J, Woods J, Veenstra G. Devolving authority for health care in Canada's provinces: 1. An introduction to the issues. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1997;156:371–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dobrow M, Paszat L, Golden B, Brown A, Holowaty E, Orchard M, et al. Measuring integration of cancer services to support performance improvements: the CSI Survey. Healthcare Policy. 2009;5(1):35–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Touati N, Roberge D, Denis J-L, Pineault R, Cazale L, Tremblay D. Governance, health policy implementation and the added value of regionalization. Healthcare Policy. 2007;2(3):97–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durbin J, Rogers J, Macfarlane D, Baranek P, Goering P. Strategies for mental health system integration: a review final report for the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care through the Ontario Mental Health Foundation 2001. Toronto, Ontario: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleury M-J. Quebec mental health services networks: models and implementation. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2005 Jun 1;:5. doi: 10.5334/ijic.127. Available from: http://www.ijic.org/. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemieux-Charles L, Chambers LW, Cockerill R, Jaglal S, Brazil K, Cohen C, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of community-based dementia care networks: the dementia care networks' study. The Gerontologist. 2005;45(4):456–64. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.4.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsasis P. The social processes of interorganizational collaboration and conflict in non-profit organizations. Non-profit Management and Leadership. 2009;20(1):5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care: a perilous journey through the health care system. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:1064–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Béland F, Bergman H, Lebel P, Hummel S. Des services intégrés pour les personnes âgées fragiles: une expérience québécois [Integrated services for the fragile elderly: the Quebec experience] In: Fleury M-J, Tremblay M, Nguyen H, Bordeleau L, editors. Le système sociosanitaire au Québec, Régulation, gouvernance et participation [The health care system in Quebec: Regulation, governance and participation] Montreal: Gaëtan Morin Publisher; 2007. p. 219–43. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheaff R, Benson L, Farbus L, Scholfeild J, Mannion R, Reeves D. Network resilience in the face of health system reform. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;70:779–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Provan K, Kenis P. Modes of network governance: structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration, Research and Theory. 2008;18(2):229–52. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoge MA, Howenstein RA. Organizational development strategies for integrating mental health services. Community Mental Health Journal. 1997;33:175–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1025044225835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agranoff R. Human services integration: past and present challenges in public administration. Public Administration Review. 1991;51:533–42. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fleishman JA. US Dept of Health and Human Services. Community-based care for persons with AIDS: developing a research agenda. AHCPR Conference Proceedings. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1990. Research issues in service integration and coordination. p. 187–267. [DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 90-3456. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leatt P, Pink G, Guerriere M. Towards a Canadian model of integrated healthcare. Healthcare Papers [serial online] 2000 Spring;1(2):13–35. doi: 10.12927/hcpap..17216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shortell S, Gillies R, Anderson D, Erickson KM, Mitchell J. Remaking health care in America: the evolution of organized delivery systems. 2nd edition. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Provan KG, Sebastian JG, Milward HB. Interorganizational cooperation in community mental health: a resource-based explanation of referrals and case coordination. Medical Care Research Review. 1996;53:94–119. doi: 10.1177/107755879605300105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whetten DA. Interorganizations relations: a review of the field. Journal of Higher Education. 1981;52:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fleury M-J. Integrated service networks: the Quebec case. Health Services Management Research. 2006;19:153–65. doi: 10.1258/095148406777888080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gans S, Horton GT. Integration of human services. New York: Praeger; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curtis S, Taket A. Health and societies. London: Arnold; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Putnam RD. Making democracy work. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morton LW. Health care restructuring: Markey Theory vs. Civil Society. Westport, CT: Auburn House; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Provan KG, Milward HB. Integration of community-based services for the severely mentally ill and the structure of public funding: a comparison of four systems. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1994;19:865–94. doi: 10.1215/03616878-19-4-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Provan K, Milward H. Do Networks Really Work? A Framework for Evaluating Public-Sector Organizational Networks. Public Administration Review. 2001;61(4):414–23. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fleury M-J, Mercier C, Lesage A, Ouadahi Y, Grenier G, Aubé D. Réseaux integres de services et réponse aux besions [Integrated service networks and their response to needs] Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yin R. Case study research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morrissey JP, Ridgely MS, Goldman HH, Bartko WT. Assessments of community mental health support systems: a key informant approach. Community Mental Health Journal. 1994;30(6):565–79. doi: 10.1007/BF02188593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berg BL. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 3rd edition. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wiktorowicz ME. Restructuring mental health policy in Ontario: deconstructing the evolving welfare state. Canadian Public Administration. 2005;48(3):386–412. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skinner W, O'Grady CP, Bartha C, Parker C. Concurrent substance use and mental health disorders: an information guide. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]