Abstract

Acrolein is a reactive unsaturated aldehyde that is produced during endogenous oxidative processes and is a major bioactive component of environmental pollutants such as cigarette smoke. Because in vitro studies demonstrate that acrolein can inhibit neutrophil apoptosis, we evaluated the effects of in vivo acrolein exposure on acute lung inflammation induced by LPS. Male C57BL/6J mice received 300 μg/kg intratracheal LPS and were exposed to acrolein (5 parts per million, 6 h/day), either before or after LPS challenge. Exposure to acrolein either before or after LPS challenge did not significantly affect the overall extent of LPS-induced lung inflammation, or the duration of the inflammatory response, as observed from recovered lung lavage leukocytes and histology. However, exposure to acrolein after LPS instillation markedly diminished the LPS-induced production of several inflammatory cytokines, specifically TNF-α, IL-12, and the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ, which was associated with reduction in NF-κB activation. Our data demonstrate that acrolein exposure suppresses LPS-induced Th1 cytokine responses without affecting acute neutrophilia. Disruption of cytokine signaling by acrolein may represent a mechanism by which smoking contributes to chronic disease in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma.

Cigarette smoking is a major causative factor in respiratory diseases such as lung cancer, emphysema, and asthma. Moreover, indirect smoke exposure during childhood substantially diminishes lung function and increases susceptibility to respiratory infection and the development of asthma (1, 2). Although cigarette smoke contains many diverse chemicals (>4500), its acute effects on cell function and toxicity appear to be due largely to volatile thiol-reactive components (3, 4), of which acrolein (2,3-propenal) is the most reactive and abundant (5, 6). Acrolein is present in mainstream cigarette smoke at concentrations of ~90 parts per million (ppm)3 (5), and ambient acrolein concentrations in smoking environments may reach levels up to 0.2 ppm (7).

Studies in vivo demonstrate that acrolein may be responsible for many of the respiratory responses to cigarette smoke exposure. Indeed, in vivo exposure to acrolein (ranging from 0.2 to 6 ppm) causes pulmonary edema (8), stimulates sensory nerves and airway cell proliferation (9, 10), and diminishes pulmonary defenses against bacterial and viral infection (7, 11). Moreover, more chronic acrolein exposure induces bronchial lesions and mucus hyperplasia (12, 13).

At the cellular level, acrolein causes an imbalance in cell survival/death control pathways by interfering with various cellular signaling events. Several studies indicate that acrolein induces apoptosis and necrosis in various cell types (14–17), but acrolein was also found to inhibit apoptosis by influencing redox-sensitive caspase signaling cascades (17–19). Such interference with apoptosis may have significant consequences during inflammatory conditions, in which apoptosis is critical in terminating inflammatory signaling.

Although acrolein exposure has been associated with inflammatory responses in vivo (13, 20), studies have also indicated immunosuppressive properties of acrolein, because it inhibits the release of several inflammatory cytokines from macrophages, T cells, and bronchial epithelial cells (14, 21, 22). These immunosuppressive properties of acrolein have been related to redox imbalances due to depletion of glutathione (GSH) (3) and/or direct interaction with redox-sensitive signaling pathways such as NF-κB or JNK (15, 22–25). However, the in vivo significance of these immunosuppressive effects has to date not been addressed.

Based on these considerations, acrolein inhalation may affect acute or chronic inflammation, e.g., by bacterial infection or allergen challenge. Therefore, the present study was designed to determine whether acrolein exposure affects the initiation or resolution of acute airway inflammation induced by the Gram-negative bacterial cell wall component, LPS.

Materials and Methods

Model of LPS-induced acute lung inflammation

Male C57BL/6J mice (6–8 wk) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories and housed for a minimum of 1 wk in the animal facility at University of Vermont. The animal study protocol was approved by University of Vermont Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and we followed the standards under the U.S. Animal Welfare Act. For induction of acute lung inflammation, mice were slightly anesthetized with inhalation of isoflurane and LPS (LPS; Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5; Sigma-Aldrich) was instilled intratracheally (i.t.) in a total volume of 50 μl in PBS to a final dose of 300 μg/kg, by pipetting 50 μl into the larynges. The dose was based on previous studies (26–28). Animals recovered quickly from the procedure with only mild discomfort.

Acrolein exposure

At various times before or after LPS instillation, animals were exposed to acrolein vapor for 6 h/day for up to 3 days, at a concentration of 5 ppm (11.5 mg/m3), in a closed exposure chamber under relative negative pressure (−1 cm H2O compared with room pressure) to avoid leaking. Acrolein (Fluka BioChemika) was placed in a glass apparatus in a 45°C water bath (slightly below its boiling point), and acrolein vapor was mixed with filtered air by delivering constant air flow (pressure of 2.5 cm H2O), and its concentration was continuously monitored by using an infrared sensor (Miran SapphIRe model M205; Thermo Scientific). Acrolein concentrations were adjusted to 5 ppm, the highest tolerable concentration that does not induce acute lung toxicity (e.g., see Ref. 7). During exposures, mice were kept in wire bottom cages, and control mice were kept in environmental filtered air under similar conditions.

Collection of lung tissues and lung lavage

At selected times after acrolein exposure and LPS challenge, animals were sacrificed by i.p. injection of sodium pentobarbital and exsanguinated. Lungs were lavaged 3 times with 500 μl of sterile PBS, and lavage fluids were kept on ice until processing. The lungs were subsequently removed and right lobes were fixed in 4% buffered paraformadehyde for 24 h and transferred to 70% ethanol for analysis of lung histology, which was performed on 5-μm thick sections stained with H&E and observed by light microscopy at 400× magnification. Left lung lobes were snap frozen in liquid N2 for biochemical analysis, or placed in RNAlater (Ambion, Texas) for 24 h before storage at −20°C, for subsequent mRNA extraction. Lung lavage fluids were centrifuged (15′, 420 × g), and supernatant were stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis of protein and cytokine levels. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of PBS for total cell counting using a hemacytometer, and cytospins were prepared for differential cell counts by staining with a modified Giemsa method (Protocol Hema 3; Fischer). At least 200 cells were counted per slide.

Protein analysis

Proteins from lung lavage supernatant were quantified using a BCA method to evaluate vascular permeability to airways (Pierce).

Bio-Plex cytokine assay

Lung lavage samples were analyzed for a panel of Th1 and Th2 cytokines using a Bio-Plex kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Plex mouse cytokine Th1/Th2 panel; Bio-Rad). Anti-cytokine bead suspensions were mixed with the samples in a 96-well plate, and processed for detection using a Bio-Plex suspension array reader (Bio-Rad).

Analysis of cytokine levels

Concentrations of IL-4, IL-12p70, IFN-γ, and TNF-α were measured in lung lavage supernatants using ELISA (Quantikine cytokine ELISA kit; R&D Systems), as recommended by the manufacturer.

Apoptosis assay

Lung lavage cells were obtained as described above, washed two times with cold PBS, and resuspended for analysis of apoptotic cells using an annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (BD Bioscience). annexin V/propidium iodide-positive cells were analyzed by flow cytometry, as described previously (24), after gating the flow cytometer to primarily detect recovered neutrophils.

Quantitative real time RT-PCR analysis of cytokine mRNA

Lung tissue mRNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) as described previously. Briefly, 1 μg of total RNA was used to prepare cDNA with M-MLV reverse transcriptase and Oligo(dT)12–16 primer. The cDNA solution was diluted 1/10 and 1 μl of the first strand cDNA product was amplified using FAM assay on demand (Applied Biosystems) for the housekeeping gene GAPDH (FAM channel) and SYBR Green method for inflammatory cytokines with the following primers were used: mouse IL12p35: 5′-ATGACCCT GTGCCTTGGTAG-3′/5′-CAGATAGCCCATCACCCTGT-3′; IL-12p40: 5′-TGACACGCCTGAAGAAGATG-3′/5′-AGTCCCTTTGGTCCAGTG TG-3′; IFN-γ: 5′-GCTTTGCAGCTCTTCCTC-3′/5′-TGAGCTCATTGA ATGCTTGG-3′; GM-CSF: 5′-GGCCTTGGAAGCATGTAGAG-3′/5′-TCATTACGCAGGCACAAAAG-3′, TNF-α: 5′-ACGGCATGGATCTCA AAGAC-3′/5′-TGGAAGACTCCTCCCAGGTA-3′ and NOS2: 5′-CC TTGTTCAGCTACGCCTTC-3′/5′-AAGGCCAAACACAGCATACC-3′. After 35 cycles, the melting points were determined as quality control for the generation of a single amplicon and CT values were obtained. ΔCT values were calculated by subtracting housekeeping gene GAPDH CT values and ΔΔCT were calculated by subtracting average ΔCT of control group for each cytokine/protein. Finally, relative quantity (RQ) was obtained from ΔΔCT by the following equation: RQ = 2−ΔΔCT. PCR products were also evaluated using 1% agarose gel with ethidium bromide to confirm molecular size.

Phosphoprotein Bio-Plex assay

Frozen lung tissue was ground in liquid N2 and extracted in Bio-Plex lysis buffer (Bio-Rad), and equivalent amounts of protein were analyzed using a Bio-Plex phosphoprotein assay (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Results were expressed as the ratio between fluorescence intensity of phosphorylated target and total target (IκBα or JNK).

NF-κBp65 activity assay

Nuclear proteins were obtained from ground frozen lung tissues using a nuclear extraction kit (Chemicon International), and protein concentration was quantified using the BCA method. NF-κBp65 activity was measured in 10 μg of nuclear protein using the Active Motif TransAM NF-κBp65 detection kit (Active Motif), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and data were corrected for blank wells and expressed as absorbance at 450 nm.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and analyzed by one-way ANOVA, and the posttest choice was Tukey’s test for nonparametric data and Bonferroni’s test for parametric data as suggested by SigmaPlot 9.0 software (Systat Software). A t test was used for comparison of the PCR results for experiments with ≤3 groups. Results were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Results

Acrolein exposure does not prolong the inflammatory response by LPS

In previous studies, we reported that acrolein is capable of inhibiting apoptotic signaling in neutrophils (19, 24), which we proposed could lead to decreased neutrophil clearance during inflammatory processes resulting in prolonged and enhanced inflammation. To test this possibility, we investigated the impact of acrolein inhalation (5 ppm) on the transient inflammatory response induced by intratracheal LPS instillation. Based on previous findings that LPS-induced inflammation reached an optimum after ~24 h, and declined at 48, 72, and 96 h (27, 28), acrolein exposure was initiated 18 h after LPS challenge for 6 h, and the 6 h/day acrolein exposure was repeated the next 2 days. Animals were harvested at the end of each acrolein exposure (24, 48, and 72 h after LPS instillation; Fig. 1A).

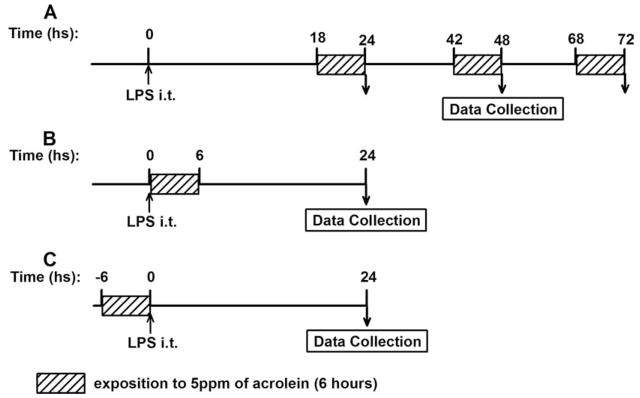

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram of experimental design. A, For analysis of acrolein exposure on the time course of LPS-induced inflammation, LPS was instilled at time 0, and exposure to 5 ppm acrolein was initiated after 18 h for a period of 6 h, which was repeated on the next 2 days. Mice were euthanized immediately after acrolein exposure, at 24, 48, and 72 h after LPS instillation. B, Mice were exposed to acrolein, started immediately following i.t. instillation of LPS, for a period of 6 h, and euthanized at 24 h later. C, Mice were pre-exposed to 5 ppm of acrolein for 6 h, before i.t. instillation of LPS and were euthanized 24 h after LPS challenge. In each case, time-matched control animals were included that received only LPS or were exposed to acrolein only.

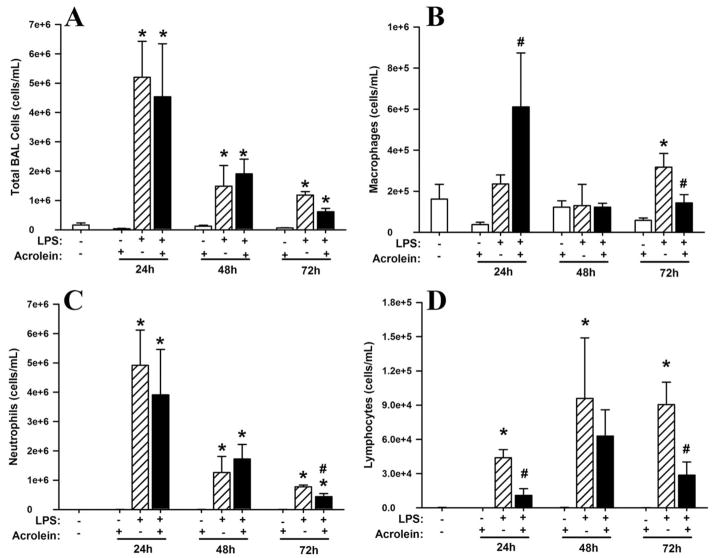

As shown in Fig. 2A, LPS instillation resulted in significant and transient lung inflammation, with the highest number of cells recovered by lung lavage after 24 h, and reduced numbers at 48 and 72 h, consistent with resolution of the inflammatory response. Cell identification by differential staining demonstrated that the major recruited cell type was neutrophils (>90%; Fig. 2C), with slightly increased numbers of macrophages and lymphocytes also observed, primarily at later time points (Fig. 2, B and D). No detectable eosinophils were observed. Lung tissue staining with H&E revealed the recruitment of neutrophils to airways, perivascular and parenchymal compartments (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of acrolein exposure on the time course of LPS-induced inflammation in mice. C57BL/6J mice were exposed to LPS and/or acrolein according to protocol A in Fig. 1, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluids were collected for analysis of total BAL cells (A), macrophages (B), neutrophils (C), and lymphocytes (D). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3 for each treatment). Multiple comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test. *, p < 0.01 vs naive mice and acrolein groups. #, p ≤ 0.05 vs mice exposed to LPS only.

Exposure to acrolein (5 ppm, 6 h/day) alone did not cause significant pulmonary inflammation (Fig. 2). Moreover, acrolein exposure did not significantly affect airways neutrophilia induced by LPS or the resolution of airway neutrophilia, illustrated by similar numbers of total lung lavage cells and neutrophils at each time point (Fig. 2, A and C). However, acrolein exposure did significantly increase macrophage numbers in LPS-challenged animals at 24 and 72 h (Fig. 2B) and reduced LPS-induced lymphocyte recruitment at each time point (which was statistically significant at 24 h; Fig. 2D). Similarly, tissue inflammation as assessed by H&E staining showed no significant changes after acrolein exposure (data not shown).

As another index of acute lung injury by LPS, we measured lung lavage protein levels, which indicate epithelial permeability and pulmonary edema. As expected, LPS instillation resulted in a significant increase in lung lavage protein levels (Fig. 3A), peaking at 48 h, and declining thereafter. LPS-induced increases in lung lavage protein levels were significantly decreased by acrolein exposure at 48 and 72 h, whereas acrolein exposure alone did not affect lung lavage protein levels.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of acrolein on LPS-induced protein leakage and inflammatory cytokine production. C57BL/6J mice were exposed as in Fig. 2, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluids were collected at 24 h for analysis of protein concentration (A) and the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α (B), IL-12p70 (C), and IFN-γ (D). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3 for each group). Multiple comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test. *, p < 0.05 vs naive and acrolein controls. #, p < 0.05 vs LPS mice.

Effects of acrolein inhalation on neutrophil apoptosis

Based on our previous findings that acrolein can inhibit apoptosis of human neutrophils (24), we initially performed experiments with bone marrow neutrophils from C57BL/6J mice, isolated as previously described (29). As expected, treatment of mouse bone marrow-derived neutrophils with acrolein similarly suppressed caspase-3 activation, inhibited constitutive apoptosis, and increased necrosis (analyzed by annexin V and propidium iodide labeling and flow cytometry; results not shown). To determine the effects of in vivo acrolein inhalation on apoptosis of extravasated neutrophils after LPS-induced airway inflammation, lung lavage fluids from LPS-challenged mice (with or without acrolein exposure) were collected and lavaged cells were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide for analysis by flow cytometry. Recovered percentages of apoptotic (annexin V-positive) and necrotic (PI-positive) cells were 4.0 ± 1.3 and 0.08 ± 0.07 24 h after LPS challenge, and 3.1 ± 0.6 and 0.21 ± 0.26 after LPS challenge followed by acrolein exposure (n = 4). Although differences were not statistically significant, acrolein exposure tended to reduce the number of apoptotic cells and increase necrotic cells, consistent with the in vitro studies (24).

Acrolein exposure inhibits cytokine production in response to LPS

LPS-induced airway inflammation is known to be mediated by TLR4-dependent signaling and production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. As a first approach to determine the effects of acrolein exposure on LPS-induced cytokine and chemokine production, we screened lung lavage fluids for a panel of Th1 and Th2 cytokines, using a multiplex protein detection system (Bio-Plex; BioRad). Results are presented in Table I and show that LPS instillation induced primarily Th1 cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-12p70, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF. Exposure of LPS-challenged mice to acrolein decreased the production of some cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-10, IL-12p70, and IFN-γ, but appeared to enhance the production of other cytokines, such as IL-5, GM-CSF, and TNF-α (Table I). To verify some of these results, we performed ELISA on lung lavage fluids, and confirmed that LPS-induced production of IL-12p70, IFN-γ, and TNF-α at 24 and 48 h were significantly reduced after acrolein exposure (Fig. 3, B–D). Levels of these cytokines reduced to near normal levels after 72 h. Curiously, analysis of TNF-α concentrations by ELISA revealed significant reduction of LPS-induced TNF-α production after exposure to acrolein (Fig. 3B), in apparent contrast to the Bio-Plex data in Table I. However, the marked decreases in IL-12p70 and IFN-γ observed by ELISA were consistent with the Bio-Plex data.

Table I.

Effects of LPS and/or acrolein on lung lavage levels of a panel of Th1/Th2 cytokinesa

| Naive | Acrolein | LPS | LPS + Acrolein | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 | 16.3 ± 2.8 | 22.1 ± 1.6 | 14.8 ± 8.6 | 9.0 ± 4.5 |

| IL-4 | nd | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 1.9 | nd |

| IL-5 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 7.3 ± 0.3 | 19.4 ± 7.1 | 23.1 ± 0.2 |

| IL-10 | 18.8 ± 12.5 | 34.3 ± 1.2 | 31.7 ± 14.2 | 14.2 ± 2.4 |

| IL-12p70 | nd | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 91.3 ± 89.3 | 3.7 ± 2.6 |

| GM-CSF | nd | 5.7 ± 3.3 | 107.7 ± 32.8 | 230.2 ± 49.8 |

| IFN-γ | nd | 11.1 ± 5.0 | 96.9 ± 94.2 | nd |

| TNF-α | nd | 6.1 ± 5.3 | 551.5 ± 321.3 | 1848.8 ± 589.5 |

Cytokine levels were measured by multiplex analysis (Bio-Plex) in lung lavage fluids obtained 24 h after exposure to LPS and/or acrolein, according to Fig. 1A. All values are expressed as pg/ml (mean ± SEM; n = 3 mice each); nd, not detectable.

We next determined whether these changes in cytokine levels were also seen at the level of mRNA expression, as analyzed by quantitative real time PCR. As shown in Fig. 4, LPS challenge markedly enhanced expression of IL-12p40, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, which was in some cases significantly suppressed after acrolein exposure, consistent with the ELISA results in Fig. 3. Moreover, acrolein exposure also tended to reduce basal mRNA levels of IL-12p40 and IFN-γ, and significantly reduced basal IL-12p35 expression. In contrast to these suppressive effects of acrolein exposure, induction of GM-CSF mRNA expression by LPS tended to be further enhanced in response to acrolein, consistent with increased GM-CSF production as analyzed by Bio-Plex (Table I). Because IFN-γ is known to induce NOS2, an important mediator of inflammation and host defense, we also analyzed effects of acrolein exposure on LPS-mediated induction of NOS2 (28) and observed a strong trend toward reduced NOS2 expression after acrolein exposure (Fig. 4F).

FIGURE 4.

Lung tissue inflammatory cytokine expression after LPS instillation and acrolein exposure. C57BL/6J mice were exposed as in Figs. 2 and 3, and total RNA was extracted from lung tissues 24 h after LPS challenge, and expression of TNF-α (A), IL-12p35 (B), IL-12p40 (C), IFN-γ (D), GM-CSF (E), and NOS2 (F) were analyzed by a quantitative real-time PCR. The CT values were normalized to GAPDH expression and relative quantities (RQ) to the naive control group are reported. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3 for each group), and t test was used (*, p < 0.05 vs naive/acrolein control groups and **, p < 0.05 vs LPS treatment) to compare groups.

Effects of acrolein on the initiation of LPS-induced inflammation

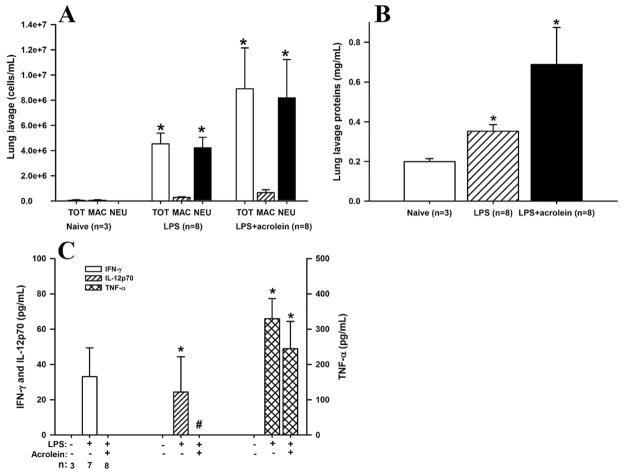

Based on the observed changes in cytokine production in the studies described above, we next determined the effect of acrolein exposure on more proximal cytokine/chemokine signaling during LPS-induced inflammation, by initiating acrolein exposure immediately after LPS challenge (Fig. 1B). As shown in Fig. 5A, while acrolein exposure in this scenario did not significantly alter LPS-induced increases in total lung lavage cells and neutrophils, there was showed a trend toward increased neutrophilic inflammation in the LPS+acrolein exposed mice. A similar trend was also observed after analysis of lung lavage protein levels, which increased significantly in response to LPS and tended to be further enhanced by simultaneous acrolein exposure (Fig. 5B). Because acrolein inhalation itself did not induce significant inflammation or protein leak (Fig. 3A), the apparent effect of acrolein exposure on LPS-induced inflammation may be synergistic. Histological analyses revealed a relatively similar degree of tissue inflammation between mice treated with LPS alone and mice that were also exposed to acrolein (data not shown). However, analysis of IL-12p70, IFN-γ, and TNF-α production demonstrated suppressive effects of acrolein that were qualitatively similar to those described when acrolein was given 18 h after LPS. Although LPS significantly increased the production of IFN-γ and IL-12p70, no IFN-γ or IL-12p70 were detectable when animals were simultaneously exposed to acrolein (Fig. 5C). However, the LPS-induced increase in TNF-α was not significantly affected by acrolein exposure, indicating that exposure did not interfere with cytokine quantification by ELISA. Analysis of mRNA levels of these cytokines by RT-PCR confirmed their increased expression after LPS, but did not reveal significant changes in response to acrolein exposure (data not shown), which suggests that these effect of acrolein is at posttranscriptional level.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of acrolein exposure during the initiation of LPS-induced inflammation. C57BL/6J mice were exposed to LPS and/or acrolein according to protocol B in Fig. 1, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids were collected for analysis of total cells, macrophages and neutrophils (A), protein levels (B), or the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-12p70, and IFN-γ (C). Results are expressed as mean = SEM. *, p < 0.05 vs naive control. #, p = 0.06 vs LPS, t test.

Effect of acrolein pre-exposure on LPS-induced inflammation

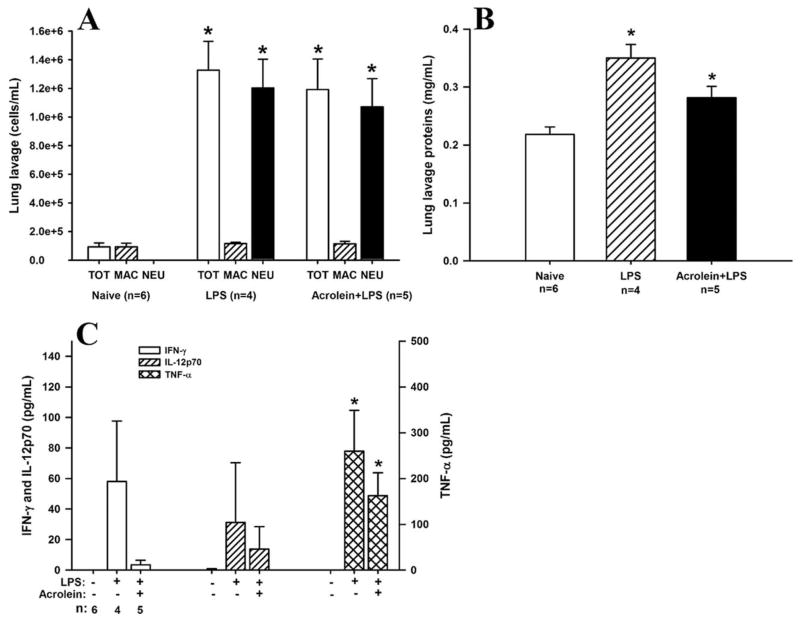

Because acrolein is capable of inhibiting NF-κB activation and could thereby attenuate LPS-induced inflammation (22, 23, 30), we performed a third set of studies in which mice were first exposed to acrolein (5 ppm, 6 h) before induction of inflammation by LPS instillation (Fig. 1C). In this scenario, LPS-induced neutrophilia and lung permeability was not affected by acrolein pre-exposure, although a slight trend toward reduced lung lavage protein levels was noted after acrolein exposure (Fig. 6, A and B). Moreover, the extent of tissue inflammation was similar in both cases (data not shown). LPS-induced production of Th1 cytokines, especially IFN-γ, again appeared to be reduced by acrolein exposure (Fig. 6C), although no statistically significant effects were seen on LPS-induced induction of mRNA of these cytokines (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of acrolein pre-exposure on LPS-induced inflammation in mice. C57BL/6J mice were exposed to LPS and/or acrolein according to protocol C in Fig. 1, and lung lavage fluids were collected for analysis of total cells, macrophages and neutrophils (A), protein levels (B), or inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-12p70, and IFN-γ (C). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. *, p < 0.05 vs naive control, t test.

Acrolein decreases NF-κB activation in vivo

To address the potential mechanism by which acrolein inhalation suppresses LPS-induced cytokine production, homogenates, or nuclear extracts from lung tissues of LPS-challenged mice with or without acrolein exposure (5 ppm/6 h) were analyzed for phosphorylation of IκB-α and JNK or NF-κB activity, based on recent studies demonstrating that reduced macrophage cytokine production by cigarette smoke is related to alterations of these signaling pathways (21, 31). As illustrated in Fig. 7A, NF-κBp65 activity in nuclear extracts was markedly enhanced after LPS challenge, as expected. Moreover, both basal and LPS-induced NF-κBp65 activity was significantly reduced following exposure to acrolein compared with exposure to room air. Analysis of IκBα phosphorylation using Bio-Plex did not reveal significant differences in the phospho/total IκBα ratio between LPS-air and LPS-acrolein treated mice, suggesting that acrolein exposure did not prevent or reduce phosphorylation of IκBα but rather suppressed NF-κB more downstream, such as at the level of NF-κB nuclear translocation or DNA binding (Fig. 7B). Because acrolein might also affect cytokine expression by inducing JNK phosphorylation and activation of c-Jun (31, 32), we analyzed JNK phosphorylation in lung tissues of LPS and acrolein-exposed mice. As shown in Fig. 7C, no significant increases in overall JNK phosphorylation were observed in response to LPS or acrolein.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of acrolein exposure on activation NF-κB and JNK. C57BL/6J mice received intratracheal LPS and were immediately exposed to either 5 ppm acrolein or room air for 6 h, and euthanized. Lung tissues were collected for analysis of NF-κB p65 activity (A) and for phosphorylation status of IκBα (B) and JNK (C), as described in the Materials and Methods section. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5–6). *, p < 0.05.

Discussion

This study was designed to test two separate hypotheses. First, based on our in vitro studies (19, 24), we proposed that acrolein inhalation during ongoing airway inflammation may prolong inflammation by negatively affecting neutrophil apoptosis and clearance. Conversely, we rationalized that acrolein inhalation might also suppress inflammatory cytokine production and inflammation by inhibition of, e.g., NF-κB signaling in airway epithelial cells (22, 33) or macrophages (23), which is essential for LPS-induced neutrophilia (30, 34). Our current study shows that exposure to subtoxic concentrations of acrolein (5 ppm, 6 h/day for up to 3 days), which are representative of indoor environmental conditions due to smoking, wood burning, or cooking (7), does not induce significant inflammation by itself, in apparent contrast with some previous studies (13). Moreover, acrolein exposure at this level did not significantly affect overall acute lung injury and airways neutrophilia in response to LPS, except for a tendency to increase LPS-induced neutrophilia during simultaneous exposure to LPS and acrolein. However, LPS-induced increases in the production of several Th1 cytokines after LPS challenge, especially IL-12 and IFN-γ, were diminished in the presence of acrolein exposure. Similarly, the appearance of lymphocytes within lung lavage fluids after LPS challenge was found to be reduced in acrolein-exposed animals (Fig. 2D), which is consistent with the reduced production of Th1-polarizing cytokine levels (e.g., IL-12) that are known to contribute to T cell proliferation (35). In this regard, our findings are in accordance with recent observations that smokers’ lungs are relatively depleted of Th1 cytokine-secreting cells (36) and would suggest that these findings may be, in part, due to acrolein within cigarette smoke.

Although acrolein has been shown to induce apoptosis in various cell types (14, 15, 17), it can also inhibit constitutive or stimulated apoptosis by direct or indirect effects on caspase cascades (18, 24), which may contribute to prolonged neutrophil or lymphocyte survival or necrosis, and enhance inflammation. Indeed, neutrophil apoptosis in LPS-challenged mice appeared to be slightly reduced after exposure to 5 ppm acrolein, but the extent to which this occurred was apparently not sufficient to result in significant changes in overall neutrophilia or its resolution.

Our observations of decreased cytokine production by acrolein are consistent with a number of in vitro studies that have demonstrated the ability of acrolein to suppress inflammatory cytokine production by macrophages, epithelial cells, or T lymphocytes (14, 21, 22) and are in line with observations that acrolein exposure decreases antibacterial or antiviral host defense (7, 11). These collective findings also suggest that acrolein may be primarily responsible for the observed adverse effects of smoking or exposure to second-hand smoke on susceptibility to infections (1, 37). Indeed, it was recently observed that exposure of mice to sidestream cigarette smoke increases respiratory syncytial virus gene expression, which was related to suppressed Th1 cytokine responses and an alteration in Th1/Th2 cytokine balances (37). Similarly, exposure to sidestream smoke was also reported to induce exaggerated Th2 responses in a mouse model of allergic airway inflammation (38). Similar findings of imbalanced Th1/Th2 cytokine signaling in our studies in response to acrolein exposure strongly suggest that these adverse effects of cigarette smoke exposure may be largely due to effects of acrolein. Intriguing recent studies also point to acrolein as a prominent player in cigarette smoke-induced lung cancer (39).

Although it is well known that LPS-induced neutrophilic inflammation is mediated by TLR-4/CD14 activation, and NF-κB-promoted induction of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, GM-CSF, and MIP-2 (30, 40), questions still exist as to what extent these cytokines are responsible for recruitment of neutrophils into the alveolar space. Indeed, it was recently shown that TNF-α and IL-1β are not essential for airways neutrophilia induced by LPS (40, 41). Hence, it is not necessarily surprising that observed changes in lung lavage cytokine levels due to acrolein exposure were not associated with significant changes in airway neutrophilia. Neutrophil emigration into the airspaces in response to inhaled LPS depends primarily on adhesion molecules and on trans-endothelial or -epithelial permeability (42, 43). In this regard, recent findings that 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, an unsaturated aldehyde with properties similar to acrolein (5), causes endothelial barrier dysfunction (44) may suggest that acrolein can promote neutrophil emigration by similar effects on airway epithelial barrier function. Such mechanism could help explain the observed trend toward increased overall LPS-induced inflammation by acrolein inhalation during the initial 6 h following LPS challenge (Fig. 2C), the time frame during which neutrophil emigration commences (27, 43). As such, possible inhibitory effects by acrolein inhalation on airway inflammation by decreasing cytokine production could have been canceled out by increased airway inflammation due to alterations in neutrophil apoptosis or epithelial permeability.

One potential mechanism by which acrolein exposure may have suppressed Th1 cytokine production (IL-12 and IFN-γ) is by up-regulation of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 (35). However, although acrolein exposure tended to increase IL-10 production, no significant differences were observed in IL-10 production by LPS with or without acrolein exposure (Table I). It is more likely that acrolein inhibits cytokine production by more direct effects on signaling pathways involved in the transcriptional activation of these cytokines. Indeed, previous studies have shown that in vitro exposure to acrolein can directly inhibit the induction of inflammatory cytokines by macrophages, epithelial cells, or T cells after appropriate stimulation (14, 21, 22). However, contrary to some of these studies, our results suggest that acrolein does not cause general suppression of proinflammatory cytokines, because expression and production of GM-CSF appeared to be enhanced by acrolein exposure (Fig. 4). Because GM-CSF enhances neutrophil survival (45), increases in GM-CSF production by acrolein may promote neutrophilia, as was suggested in some of our studies (e.g., see Fig. 5).

The precise mechanisms by which acrolein or cigarette smoke affects cell signaling pathways is unknown, but they appear related to changes in cellular GSH status and consequent effects on redox-sensitive signaling pathways such as NF-κB (46, 47). Indeed, cigarette smoke and acrolein can readily decrease intracellular levels of GSH, due to conjugation reactions catalyzed by GSH S-transferases (GSTs) (48–50). Cellular GSH status may play an important role in the regulation of many signaling pathways, such as the activation of MAPKs. For example, reductions in GSH levels by oxidants were recently found to be associated with increased activation of JNK and inhibition of p38-MAPK activation, which collectively resulted in reduced macrophage IL-12 production in response to LPS (32). Moreover, oxidant exposure was recently found to suppress IL-12p40 expression due to interference with NF-κB pathways (51). Previous findings that acrolein can deplete cellular GSH, suppress NF-κB (22, 23), and activate JNK (25, 52) suggest that acrolein might inhibit the production of IL-12p70 and IFN-γ by a similar mechanism. Furthermore, depletion of cellular GSH in APCs has been associated with polarization to a Th2 response, with reduced production of Th1-polarizing cytokines such as IL-12 (53, 54), which suggests that cigarette smoke-derived acrolein might similarly contribute to Th1/Th2 imbalances and promote the development of allergic airway disease. In our study, activation of NF-κB in response to LPS challenge in vivo was indeed suppressed after inhalation of acrolein (5 ppm/6 h). This finding is also in accordance with observed reduced NF-κB activation of ex vivo alveolar macrophages from cigarette smoke-exposed mice (31). Although acrolein is capable of activating JNK and inducing c-Jun phosphorylation (25), acrolein inhalation under our conditions did not significantly affect JNK phosphorylation in lung tissues in vivo (Fig. 7).

In addition to indirect cellular effects in response to altered cellular GSH status, acrolein could also directly target functional proteins by Michael addition to cysteine, histine, or lysine residues (5, 55, 56). For example, recent studies indicated that inhibition of caspase activation by acrolein is largely due to direct caspase modifications rather than indirect effects due to GSH changes (18). Similarly, several studies have suggested that acrolein can inhibit NF-κB activation by direct alkylation of IκB kinase or inhibit DNA binding by alkylation of NF-κB (22, 23, 57, 58). Our observation that acrolein inhalation reduced NF-κB activation, but did not significantly suppress IκBα phosphorylation, suggests that acrolein may inhibit this pathway by an alternative mechanism. This might involve direct modification of NF-κB protein (58) or inhibition of ligand-induced dimerization of TLR4 (59). Given the complexity of overall NF-κB regulation, by many diverse activators and in multiple lung cell types, elucidating the precise mechanism of action by which acrolein interferes with this general signaling pathway will be difficult, and future studies will be needed to better address the mechanisms by which acrolein and other relevant aldehydes can impact on this and other signaling pathways and to identify their critical cellular and molecular targets.

In summary, our present studies demonstrate that (sub)acute exposure to acrolein does not significantly alter transient neutrophilia and acute lung injury in response to LPS challenge. However, significant and selective changes in Th1 cytokine production implicate the possible importance of acrolein in impaired innate immune responses against airways infections observed in acute and chronic smokers (11, 60). Decreases in Th1 cytokine expression by acrolein may also highlight a potential mechanism by which smoking contributes to alterations in acquired immunity and development of allergic airways diseases such as asthma.

Acknowledgments

We thank Justin Robbins and Stacie Beuschel for assistance with the animal exposures, Scott Tighe at the Vermont Cancer Center for assistance with flow cytometry analysis, and Dr. Umadevi Wesley (University of Vermont) for designing q-RT-PCR primers.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL068865 and HL074295.

Abbreviations used in this paper: ppm, parts per million; GSH, glutathione; i.t., intratracheal.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.DiFranza JR, Aligne CA, Weitzman M. Prenatal and postnatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure and children’s health. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1007–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kabesch M, Hoefler C, Carr D, Leupold W, Weiland SK, von Mutius E. Glutathione S transferase deficiency and passive smoking increase childhood asthma. Thorax. 2004;59:569–573. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.016667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leuchtenberger C, Leuchtenberger R, Zbinden I. Gas vapour phase constituents and SH reactivity of cigarette smoke influence lung cultures. Nature. 1974;247:565–567. doi: 10.1038/247565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green GM. Cigarette smoke: protection of alveolar macrophages by glutathione and cysteine. Science. 1968;162:810–811. doi: 10.1126/science.162.3855.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujioka K, Shibamoto T. Determination of toxic carbonyl compounds in cigarette smoke. Environ Toxicol. 2006;21:47–54. doi: 10.1002/tox.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Holian A. Acrolein: a respiratory toxin that suppresses pulmonary host defense. Rev Environ Health. 1998;13:99–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hales CA, Musto SW, Janssens S, Jung W, Quinn DA, Witten M. Smoke aldehyde component influences pulmonary edema. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:555–561. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.2.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris JB, Stanek J, Gianutsos G. Sensory nerve-mediated immediate nasal responses to inspired acrolein. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1877–1886. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.5.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roemer E, Anton HJ, Kindt R. Cell proliferation in the respiratory tract of the rat after acute inhalation of formaldehyde or acrolein. J Appl Toxicol. 1993;13:103–107. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550130206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jakab GJ. Adverse effect of a cigarette smoke component, acrolein, on pulmonary antibacterial defenses and on viral-bacterial interactions in the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;115:33–38. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.115.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa DL, Kutzman RS, Lehmann JR, Drew RT. Altered lung function and structure in the rat after subchronic exposure to acrolein. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;133:286–291. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borchers MT, Wesselkamper S, Wert SE, Shapiro SD, Leikauf GD. Monocyte inflammation augments acrolein-induced Muc5ac expression in mouse lung. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L489–L497. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.3.L489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Hamilton RF, Jr, Taylor DE, Holian A. Acrolein-induced cell death in human alveolar macrophages. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;145:331–339. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanel A, Averill-Bates DA. The aldehyde acrolein induces apoptosis via activation of the mitochondrial pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1743:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nardini M, Finkelstein EI, Reddy S, Valacchi G, Traber M, Cross CE, van der Vliet A. Acrolein-induced cytotoxicity in cultured human bronchial epithelial cells: modulation by α-tocopherol and ascorbic acid. Toxicology. 2002;170:173–185. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kern JC, Kehrer JP. Acrolein-induced cell death: a caspase-influenced decision between apoptosis and oncosis/necrosis. Chem Biol Interact. 2002;139:79–95. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(01)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hristova M, Heuvelmans S, van der Vliet A. GSH-dependent regulation of Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation by acrolein. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:361–367. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finkelstein EI, Nardini M, van der Vliet A. Inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis by acrolein: a mechanism of tobacco-related lung disease? Am J Physiol. 2001;281:L732–L739. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.3.L732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kilburn KH, McKenzie WN. Leukocyte recruitment to airways by aldehyde-carbon combinations that mimic cigarette smoke. Lab Invest. 1978;38:134–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert C, McCue J, Portas M, Ouyang Y, Li J, Rosano TG, Lazis A, Freed BM. Acrolein in cigarette smoke inhibits T-cell responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:916–922. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valacchi G, Pagnin E, Phung A, Nardini M, Schock BC, Cross CE, van der Vliet A. Inhibition of NFκB activation and IL-8 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells by acrolein. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:25–31. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L, Hamilton RF, Jr, Holian A. Effect of acrolein on human alveolar macrophage NF-κB activity. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L550–L557. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.3.L550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finkelstein EI, Ruben J, Koot CW, Hristova M, van der Vliet A. Regulation of constitutive neutrophil apoptosis by the α, β-unsaturated aldehydes acrolein and 4-hydroxynonenal. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:L1019–L1028. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00227.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pugazhenthi S, Phansalkar K, Audesirk G, West A, Cabell L. Differential regulation of c-jun and CREB by acrolein and 4-hydroxynonenal. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szarka RJ, Wang N, Gordon L, Nation PN, Smith RH. A murine model of pulmonary damage induced by lipopolysaccharide via intranasal instillation. J Immunol Methods. 1997;202:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00236-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chignard M, Balloy V. Neutrophil recruitment and increased permeability during acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:L1083–L1090. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okamoto T, Gohil K, Finkelstein EI, Bove P, Akaike T, van der Vliet A. Multiple contributing roles for NOS2 in LPS-induced acute airway inflammation in mice. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:L198–L209. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00136.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schock BC, Van der Vliet A, Corbacho AM, Leonard SW, Finkelstein E, Valacchi G, Obermueller-Jevic U, Cross CE, Traber MG. Enhanced inflammatory responses in α-tocopherol transfer protein null mice. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;423:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poynter ME, Irvin CG, Janssen-Heininger YM. A prominent role for airway epithelial NF-κB activation in lipopolysaccharide-induced airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2003;170:6257–6265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaschler GJ, Zavitz CC, Bauer CM, Skrtic M, Lindahl M, Robbins CS, Chen B, Stampfli MR. Cigarette smoke exposure attenuates cytokine production by mouse alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:218–226. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0053OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Utsugi M, Dobashi K, Ishizuka T, Endou K, Hamuro J, Murata Y, Nakazawa T, Mori M. c-Jun N-terminal kinase negatively regulates lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-12 production in human macrophages: role of mitogen-activated protein kinase in glutathione redox regulation of IL-12 production. J Immunol. 2003;171:628–635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horton ND, Biswal SS, Corrigan LL, Bratta J, Kehrer JP. Acrolein causes inhibitor κB-independent decreases in nuclear factor κB activation in human lung adenocarcinoma (A549) cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9200–9206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noulin N, V, Quesniaux F, Schnyder-Candrian S, Schnyder B, Maillet I, Robert T, Vargaftig BB, Ryffel B, Couillin I. Both hemopoietic and resident cells are required for MyD88-dependent pulmonary inflammatory response to inhaled endotoxin. J Immunol. 2005;175:6861–6869. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:133–146. doi: 10.1038/nri1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagiwara E, Takahashi KI, Okubo T, Ohno S, Ueda A, Aoki A, Odagiri S, Ishigatsubo Y. Cigarette smoking depletes cells spontaneously secreting Th(1) cytokines in the human airway. Cytokine. 2001;14:121–126. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phaybouth V, Wang SZ, Hutt JA, McDonald JD, Harrod KS, Barrett EG. Cigarette smoke suppresses Th1 cytokine production and increases RSV expression in a neonatal model. Am J Physiol. 2006;290:L222–L231. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00148.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seymour BW, Pinkerton KE, Friebertshauser KE, Coffman RL, Gershwin LJ. Second-hand smoke is an adjuvant for T helper-2 responses in a murine model of allergy. J Immunol. 1997;159:6169–6175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng Z, Hu W, Hu Y, Tang MS. Acrolein is a major cigarette-related lung cancer agent: Preferential binding at p53 mutational hotspots and inhibition of DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15404–15409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607031103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreland JG, Fuhrman RM, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Quinn TJ, Benda E, Pruessner JA, Schwartz DA. TNF-α and IL-1 β are not essential to the inflammatory response in LPS-induced airway disease. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:L173–L180. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.1.L173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith S, Skerrett SJ, Chi EY, Jonas M, Mohler K, Wilson CB. The locus of tumor necrosis factor-α action in lung inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:881–891. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.6.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Basit A, Reutershan J, Morris MA, Solga M, Rose CE, Jr, Ley K. ICAM-1 and LFA-1 play critical roles in LPS-induced neutrophil recruitment into the alveolar space. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:L200–L207. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00346.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reutershan J, Basit A, Galkina EV, Ley K. Sequential recruitment of neutrophils into lung and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in LPS-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:L807–L815. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00477.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Usatyuk PV, Parinandi NL, Natarajan V. Redox regulation of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal-mediated endothelial barrier dysfunction by focal adhesion, adherens, and tight junction proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35554–35566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klein JB, Rane MJ, Scherzer JA, Coxon PY, Kettritz R, Mathiesen JM, Buridi A, McLeish KR. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor delays neutrophil constitutive apoptosis through phosphoinositide 3-kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways. J Immunol. 2000;164:4286–4291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muller T, Gebel S. The cellular stress response induced by aqueous extracts of cigarette smoke is critically dependent on the intracellular glutathione concentration. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:797–801. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kehrer JP, Biswal SS. The molecular effects of acrolein. Toxicol Sci. 2000;57:6–15. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/57.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reddy S, Finkelstein EI, Wong PS, Phung A, Cross CE, van der Vliet A. Identification of glutathione modifications by cigarette smoke. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1490–1498. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rahman I, MacNee W. Lung glutathione and oxidative stress: implications in cigarette smoke-induced airway disease. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L1067–L1088. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.6.L1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berhane K, Widersten M, Engstrom A, Kozarich JW, Mannervik B. Detoxication of base propenals and other α, β-unsaturated aldehyde products of radical reactions and lipid peroxidation by human glutathione transferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1480–1484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khan N, Rahim SS, Boddupalli CS, Ghousunnissa S, Padma S, Pathak N, Thiagarajan D, Hasnain SE, Mukhopadhyay S. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits IL-12 p40 induction in macrophages by inhibiting c-rel translocation to the nucleus through activation of calmodulin protein. Blood. 2006;107:1513–1520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ranganna K, Yousefipour Z, Nasif R, Yatsu FM, Milton SG, Hayes BE. Acrolein activates mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;240:83–98. doi: 10.1023/a:1020659808981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kato T, Tada-Oikawa S, Takahashi K, Saito K, Wang L, Nishio A, Hakamada-Taguchi R, Kawanishi S, Kuribayashi K. Endocrine disruptors that deplete glutathione levels in APC promote Th2 polarization in mice leading to the exacerbation of airway inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1199–1209. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peterson JD, Herzenberg LA, Vasquez K, Waltenbaugh C. Glutathione levels in antigen-presenting cells modulate Th1 versus Th2 response patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3071–3076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Furuhata A, Nakamura M, Osawa T, Uchida K. Thiolation of protein-bound carcinogenic aldehyde: an electrophilic acrolein-lysine adduct that covalently binds to thiols. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27919–27926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202794200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uchida K. Current status of acrolein as a lipid peroxidation product. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1999;9:109–113. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(99)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ji C, Kozak KR, Marnett LJ. IκB kinase, a molecular target for inhibition by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18223–18228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lambert C, Li J, Jonscher K, Yang TC, Reigan P, Quintana M, Harvey J, Freed BM. Acrolein inhibits cytokine gene expression by alkylating cysteine and arginine residues in the NF-κB1 DNA binding domain. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19666–19675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Youn HS, Lee JS, Lee JY, Lee MY, Hwang DH. Acrolein with an α, β-unsaturated carbonyl group inhibits LPS-induced homodimerization of toll-like Receptor 4. Mol Cells. 2008;25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aronson MD, Weiss ST, Ben RL, Komaroff AL. Association between cigarette smoking and acute respiratory tract illness in young adults. J Am Med Assoc. 1982;248:181–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]