Abstract

Epileptiform discharges recorded in the 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) in vitro epilepsy model are mediated by glutamatergic and GABAergic signaling. Using a 60-channel perforated multi-electrode array (pMEA) on corticohippocampal slices from 2 to 3 week old mice we recorded interictal- and ictal-like events. When glutamatergic transmission was blocked, interictal-like events events no longer initiated in the hilus or CA3/CA1 pyramidal layers but originated from the dentate gyrus granule and molecular layers. Furthermore, frequencies of interictal-like events were reduced and durations were increased in these regions while cortical discharges were completely blocked. Following GABAA receptor blockade interictal-like events no longer propagated to the dentate gyrus while their frequency in CA3 increased; in addition, ictal-like cortical events became shorter while increasing in frequency. Lastly, drugs that affect tonic and synaptic GABAergic conductance modulate the frequency, duration, initiation and propagation of interictal-like events. These findings confirm and expand on previous studies indicating that multiple synaptic mechanisms contribute to synchronize neuronal network activity in forebrain structures.

Keywords: Seizures, hippocampus, 4-aminopyridine, local field potentials, GABA

1. Introduction

The potassium channel blocker 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) has been widely used as an in vitro model of epilepsy for the last three decades (see for review Avoli et al. 2002). This compound enhances neuronal activity and mimics the electroencephalographic activity recorded in patients affected by partial epilepsy. Three types of synchronous field potential discharges have been reported during 4-AP application: i) “slow”-GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) -mediated interictal-like events that occur at a relatively low frequency of 0.25 to 0.05 Hz., ii) “fast” interictal-like events that have a higher frequency of 0.5 to 0.25 Hz, originate in CA3 and are mainly mediated by glutamate receptors, and iii) long-lasting ictal-like events that in adult brain slices originate in entorhinal cortex and propagate to hippocampus proper (Avoli et al. 2002). Ictal-like events require a contiguous connection between entorhinal cortex and hippocampus in slices from adult rodents.

Both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmissions modulate the frequencies and durations of these field potential discharges (see for review Avoli et al. 2002). Furthermore, GABAA receptor signaling can be epileptogenic (Klaassen et al. 2002) and is required for the generation of interictal-like events in human brain slices (Cohen et al. 2002). Indeed, in the 4-AP model, slow interictal-like events are blocked only when bicuculline, the competitive antagonist for GABAA receptors, is applied (Avoli et al. 2002). Thus, GABAA receptors play an important role in the 4-AP in vitro epilepsy model.

GABA is the principle inhibitory neurotransmitter in the mammalian forebrain. GABAA receptors are ligand-gated ion channels permeable to Cl− and HCO3− and are assembled as pentameric proteins comprised of distinct subunits (MacDonald and Olsen, 1994). The specific subunit composition of the receptors determines the channel kinetics, pharmacological sensitivity (MacDonald and Olsen, 1994) and subcellular localization (Fritschy and Brunig, 2004). Synaptic GABAA receptors mediate phasic inhibition produced by quantal release of GABA at high concentrations, which results in inhibitory postsynaptic currents (Stell and Mody, 2002, Farrant and Nusser, 2005). In addition, a persistent concentration of ambient GABA generates a tonic conductance via high-affinity extrasynaptic GABAA receptors. (Stell and Mody, 2002, Farrant and Nusser, 2005; Glykys et al 2007). These currents show little to no desensitization and by defining the neuronal membrane potential at rest provide a powerful persistent inhibition that allows for the regulation of network excitability (Scimemi et al., 2005; Semyanov et al., 2003). Tonic GABAergic current is increased after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in dentate granule cells and in subicular neurons (Zahn et. al 2009; Biagini et al., 2010), and it is reduced in basolateral amygdala circuitry after kainate status (Fritsch et al 2002). Tonic current is expressed to varying degrees in the multiple cell-types of hippocampus (Scimemi et al., 2005; Semyanov et. al 2003; Mann and Mody 2009; Wyeth et al 2010).

Here, by using multisite electrophysiological recordings with a perforated multi electrode array (pMEA), we analyzed the changes in synchronous epileptiform activity induced by 4-AP, under the pharmacological manipulation of phasic and tonic GABAergic currents. We also studied the action of NMDA and non-NMDA glutamatergic receptor antagonists. Our experiments were performed using acute coronal hippocampal slices from juvenile mice, as coronal slices permit the focused study of intrinsic hippocampal network dynamics without the influence of enthorinal cortex, and in turn allow for the analysis of independent cortical activity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Slice Preparation

C57BL/6J mice aged postnatal days 13 to 18 were sacrificed by decapitation in agreement with the Georgetown University Animal Care and Use committee (GUACUC), and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of Laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used. Brains were rapidly removed and placed in an ice-cold slicing solution containing (in mM): 86 NaCl, 3 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 1 NaH2PO4, 75 sucrose, 25 glucose, 1 CaCl2, and 25 NaHCO3. Coronal slices (300 μm thick) containing hippocampus and neocortex were prepared using a Vibratome 3000 Plus Sectioning System (Vibratome, St. Louis, MO). Slices were further reduced in size to approximately 6.5 mm sided squares to better fit them on the perforated multi electrode array (pMEA, Multi Channel Systems GmbH, Reutlingen, Germany). The slices contained the dorsal section of hippocampus proper and parietal somatosensory neocortex. An illustration of a typical slice used can be found in Suppl. Fig. 1. Sections recovered in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) 124 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 1 CaCl2, and 26 NaHCO3 at 32°C for 30 min. Brain slices remained in ACSF at room temperature until they were utilized in the experiment. All solutions were maintained at pH 7.4 by continuous bubbling with 95% O2-5% CO2.

2.2. Chemicals

The effect of specific drug treatments (3,3-(2-carboxypiperazine-4-yl)propyl-1-phosphonate (CPP, 12 μM) and (2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione) (NBQX, 10 μM), bicuculline methabromide (BMR, 25 μM), pentobarbital (20 μM), or (4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol) (THIP, 10 μM) were studied upon perfusion of the slice by gravity at 3 ml/min. Chemicals were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich Canada (Oakville, Ontario, Canada) and Tocris Cookson (Ellisville, MO, USA).

2.3. pMEA Recordings

The pMEA consists of 60 platinum electrodes, with a 30 μm electrode diameter and a 200 μm inter-electrode spacing. The substrate on which the electrodes rest is perforated in order to allow suctioning of the slice onto the array for recording. Each slice was positioned over the array to align the hippocampus and neocortex in parallel with respect to the columns of electrodes. When the slice was in place, gentle suction was applied through a 30 ml syringe connected to a chamber directly below the pMEA. When the slice covered all the perforations, at the moment of suction a seal was formed. This facilitated close contact between the slice and the pMEA electrodes throughout the recording. In all experiments, MC Rack (4.0, Multi Channel Systems), was utilized to acquire data. Recordings were sampled at 5 kHz. The various ACSF solutions were continuously preheated to 32 °C just before reaching the MEA chamber with a heated perfusion cannula (ALA instruments, Farmingdale, NY). Temperature in the MEA tissue chamber was verified with an analogue YS1 Telethermometer (Yellow Springs Instrument Co., Yellow Springs, OH).

2.4. Induction of epileptiform activity

In order to induce spontaneous epileptiform-like discharges, the hippocampal slices were perfused with ACSF-containing 4-AP (100 μM). This defined the control condition and all experiments commenced with a 24 min recording. A second 24 min session followed with the ACSF + 4-AP solution containing one of the drugs described above. In addition, the control slices that received continuous treatment with 4-AP after the initial 24 min showed no change in frequencies, sites of initiation, and level of propagation.

2.5. Data analysis

MC Rack was used to record and display data. An in-house adaptation of MEATools (Egert et al., 2002) written using Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA), imports the MC Rack data into Matlab variables for further analysis. The last six minutes of the 24 minutes of data recorded in each condition were analyzed when activity was stabilized for both control and drug treatments. Specifically, we calculated the power spectrum, wavelet transform, frequencies and durations of local field potentials (LFPs) recorded from each electrode within each slice. Frequency decomposition was performed on each six-minute trace and the result was smoothed using a Savitzky-Golay polynomial smoothing filter. In addition, to examine the finer temporal structure of the activity, we measured the power spectrum within each LFP. After visual inspection of the power distribution from 0 to 200 Hz, we narrowed the range of analysis to two regions: 0.1–4Hz and 160–200Hz. Next, we measured the time evolution of the power distribution by applying a wavelet transformation. Using a normalized Morlet wavelet centered at angular frequency, ω0 = 6, scales were chosen to reflect the frequencies, f, between 10−3 and 1 Hz as follows:

Wavelet transforms are presented as color-coded frequency vs. time plots with warmer colors representing larger power. Lastly, we calculated the durations of individual LFPs for three electrodes in the CA3 subfield and dentate gyrus, as well as the durations of ictal-like events for three electrodes in neocortex. These data were averaged to attain frequency and duration values for each anatomical area. Data analysis programs were written using Matlab. Statistical analyses were calculated in Origin 8.0 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). For the six-minute power spectra and durations, average data are presented as mean± S.D. For individual LFP power spectrum analysis, average data are presented as mean± S.E.M.

2.5.1. Movies of color coded voltage activity

The initiation and propagation of events in different areas were determined by constructing contour plots from raw data files at one frame per sampling point (5 KHz) from each of the 60-channels plotted simultaneously using the Analysis Rack within MC Rack software. This was followed by an interpolation analysis utilizing Movie Tool in MEATools with a 5 point Savitzky-Golay filter before export to JPEG image format. Individual JPEGs were then concatenated and converted in AVI animations using ImageJ (Abramoff et al., 2004).

Three types of epileptiform-like activity were recorded (see Results for detailed description). Approximately 70% of slices exhibited this stereotyped activity, and if all three types of field potentials were present, the slice was included in the analysis. Ictal-like events originated in neocortex and did not propagate to hippocampus. Only rarely were ictal-like potentials present in CA1 and with diminishing amplitude in CA3 and DG as electrodes increased in distance from neocortex. The small number of brain slices in which ictal-like activity was present in the hippocampus, the amplitude variations and the fact that ictal-like events were superimposed over interictal-like events in hippocampus led us to suspect that the ictal-like activity recorded in the hippocampus was volume-conducted from cortex, which displayed simultaneous large-amplitude ictal-like activity. Furthermore, no ictal-like events were recorded in four hippocampal slices that contained no cortex and ictal-like events were generated in four cortical slices that contained no hippocampus. As such, interictal-like events in hippocampus were analyzed separately from ictal-like events in neocortex in combined slices.

2.6. Statistics

The data was analyzed for a normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Control frequencies, durations, points of initiation, and propagation were compared among groups using a one-way ANOVA. Paired t-tests and 2-sample T-tests were used to compare frequency, duration, initiation, and propagation differences between groups.

3. Results

3.1. Stereotyped activity in 4-AP

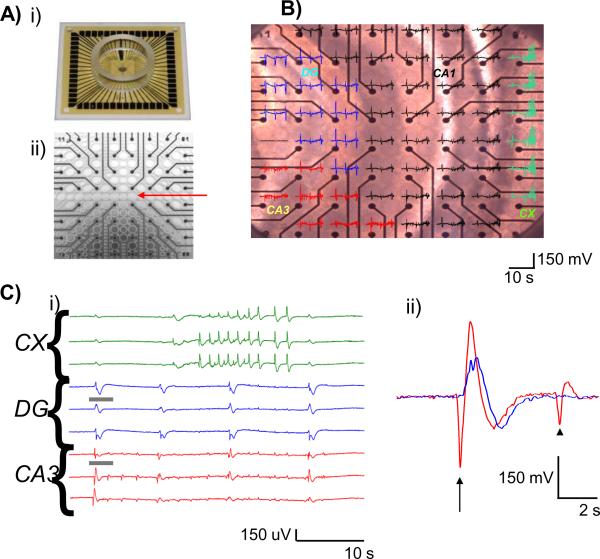

Using a pMEA illustrated in Fig. 1A, we recorded field potentials induced by 4-AP, Fig. 1B,C similar to those previously reported with other approaches (Avoli et al. 2002, Ziburkus et al. 2006). Epileptiform activity was maintained throughout the recordings, due to the perfusion of the slice via the pMEA perforations (Fig 1A, Egert et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

Stereotyped activity during application of 4-AP.

A) i) Example of a 60 channels pMEA. ii) Perforated MEA at 40× magnification illustrating perforations (red arrow) that permits gentle suction of the slice for a more stable recording and high signal to noise ratio due to the reduced distance between the electrodes and the tissue.

B) Photograph of cortico-hippocampal slice over pMEA with voltage traces recorded at each electrode overlaid in distinct colors. Colors indicate the anatomical area: red – CA3, blue – dentate gyrus (DG), and green – cortex (Cx).

C) i) Example traces of local field potentials (LFP) from selected channels in the anatomical regions indicated. ii) Overlap of the expanded view of segments of traces in i) indicated by grey bars. LFPs in CA3 leads are compared to those recorded in dentate gyrus (DG, arrows) and often CA3 events do not propagate to dentate gyrus (arrowhead). Color coding as in B.

In order to assess the epileptiform activity of hippocampus and neocortex separately, we used neocortico-hippocampal slices in the coronal plane, which contain little connections between dorsal hippocampus and neocortex. As previously reported in several 4-AP studies (Avoli et al 1996 a & b; Avoli et al. 2002 for review), we were able to record three distinct neuronal patterns of activity in different sections of our slice preparation (Fig. 1B&C). Ictal-like field potentials, with durations longer than four seconds and a biphasic waveform (tonic-clonic) originated in the neocortex and did not propagate to hippocampus (Fig. 1C and see Methods for further details). Thus, two distinct types of interictal-like local field potentials were the only population events present in hippocampus: (i) “CA3-only” LFPs that were usually circumscribed to the CA3 area, and (ii) “CA3-DG” LFPs that although initiated in CA3, propagated to the dentate gyrus (DG, Fig 1B&C). Interictal-like activity in CA3 and CA1 was highly synchronous but LFPs were present less consistently in CA1. Therefore, our analysis focused on LFPs recorded from electrodes located in CA3 and DG population events.

The average frequencies of the LFPs recorded in each anatomical area, CA3, DG, and neocortex (CX) were 0.071±0.006Hz, 0.046±0.003 Hz, and 0.008±0.001Hz respectively (n= 21 slices, averaged frequency value of three leads per anatomical area). CA3 and DG frequencies were significantly different from one another (p<0.001). This difference in frequency reflects presumably the presence of CA3-only field potentials in CA3. Of 974 events in which propagation was analyzed, 198 remained only in CA3 while 776 propagated to DG as well (Fig 6, Suppl. movie 1 and 3). Interictal-like events in both CA3 and DG had significantly higher frequencies than ictal-like events in neocortex (n= 21 slices, p <0.001).

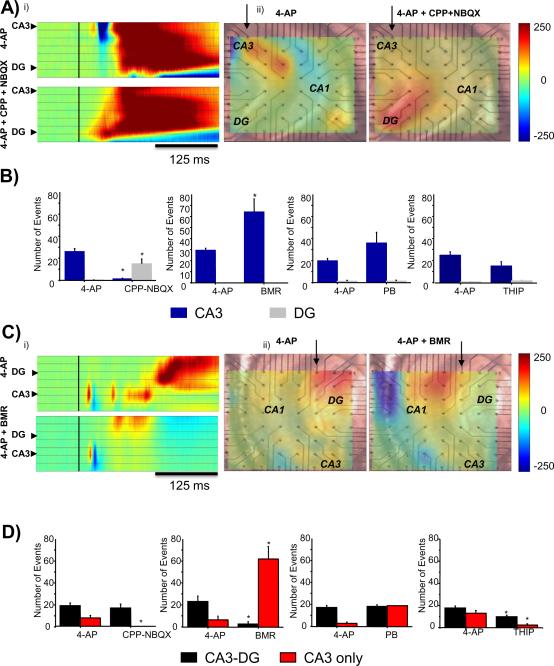

Figure 6.

Initiation and Propagation of Synchronous Field Potential Discharges

A. Initiation. i) Plots of time-dependent color-coded voltage changes in 4-AP (top) and 4-AP + NBQX (bottom) from columns of selected electrodes illustrated by arrows in middle and right panels. Note change in initiation point from CA3 to dentate gyrus in CPP + NBQX. ii) Color-coded voltages recorded from the MEA overlapped onto low magnification (4×) bright field images of the hippocampal slice. Each snapshot illustrates the initiation point of synchronous LFP discharges shifting from CA3 in 4-AP (left) to dentate gyrus in CPP + NBQX (right).

B. Summary of results of initiation for each treatment. Data are expressed as number of events originating in electrodes located in CA3 (blue) or DG (grey). Events were collected from all electrodes in each area (at least 5 per area including both pyramidal or granule cell layers and dendritic layers) and averaged across at least 4 slices. *p<0.05 independent t-test.

C. Propagation. i) Plots of time-dependent color-coded voltage changes in 4-AP (top) and 4-AP + BMR (bottom) from columns of selected electrodes illustrated by arrows in middle and right panels. Note the failure of propagation from CA3 to dentate gyrus in BMR. ii) Color-coded voltages recorded from the MEA overlapped onto bright field image of the hippocampal slice. Each snapshot shows the endpoint of LFP, illustrating the lack of propagation to dentate gyrus in BMR.

D. Summary of results of propagation for each treatment. Data are expressed as number of events recorded simultaneously in both CA3 and DG electrodes (black) or exclusively in CA3 electrodes (red). Events were collected from all electrodes in each area (at least 5 per area including both pyramidal or granule cell layers and dendritic layers) and averaged across at least 4 slices. *p<0.05 independent t-test.

In 958 out of 978 interictal-like LFPs, recorded from hippocampal leads and assessed across 21 slices, the initiation point was in stratum radiatum of CA3 (Fig 1C, Fig. 6, Suppl. movies 1 and 3). Thus, both events that remained only within CA3, and those that propagated to DG as well, initiated in CA3 98.8% of the time. The average durations of all events seen per slice in CA3, DG, and CX were 1.19±0.12 s, 1.23±0.11s, and 16.5±1.3 s (n= 21 slices). DG and CA3 events were not significantly different from each other in durations but were significantly shorter than CX (n= 21, p<0.001). Without pharmacological blockade (see below), it was not possible to measure LFP duration from recordings in each anatomical structure as a means to differentiate which events propagate only within CA3 and those that propagate to DG.

3.2. GluR antagonists decrease the frequency of events in CA3 and silences cortical activity while changing the initiation point of the field potentials from CA3 to DG

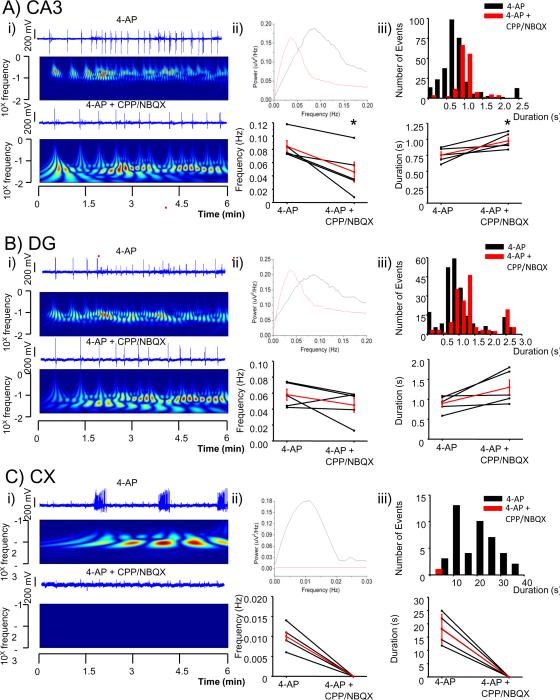

When we blocked glutamatergic signaling with both AMPA and NMDA receptor blockers (CPP (12μM) and NBQX (10μM)), interictal-like field potentials identified in CA3 only decreased significantly in frequency from 0.076±0.003 Hz to 0.010±0.033 Hz (n=5, p<0.05) (i.e., a reduction of 87%), while their duration was significantly increased from 0.75±0.05 s to 0.98±0.05 s (n= 5, p<0.05) (i.e., an increase of 29%) (Fig 2A). DG showed a trend towards lower frequency and duration but data were not significantly different (Fig 2B). Furthermore, events that initiated in CA3 and did not propagate to DG were completely silenced after blocking glutamatergic signaling (Fig 6). Since the duration of LFPs recorded in CA3 increased with these drugs (Fig.2A iii, bottom), it is likely that CA3 events blocked by CPP/NBQX, which do not propagate to DG were shorter in duration (see also Fig. 1C as an example, arrowhead). Activity in neocortical leads was completely silenced by the addition of GluR antagonist (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Glutamate receptor antagonists decrease the frequency of LFPs but increased their duration in DG and CA3 areas while silencing cortical activity.

A comparison of LFP recorded from a hippocampal slice from selected channels of a pMEA in the presence and the absence of CPP (12 μM) and NBQX (10 μM).

i) Selected channel traces in each specified area (CA3 in A, DG in B and Cx in C) are shown over color coded power (wavelet analysis with frequencies plotted in a log scale; warmer colors indicate higher power) in the absence (top) and the presence of the drugs (bottom).

ii) Top: overlaps of power spectra of traces shown in i) in each specified area (CA3 in A, DG in B and Cx in C). Bottom: plot of overall averages of peak frequencies derived from a pool of 3 channels in each selected area in the presence and absence of the drugs are shown together with the average in red from 4 slices. * p < 0.05 paired t-test.

iii) Top: histogram of duration (bin size 0.2 s in CA3 and DG and 2 s in Cx) of LFPs derived from an aggregate of 3 channels in each selected area in the presence and absence of the drugs. Bottom: plot of overall averages of durations in each selected area are shown together with the average in red from 4 slices.

* p < 0.05 paired t-test.

Fig. 2 A shows an example of wavelet spectral analysis for the 6 min period illustrated. In addition to the reported decrease in frequency summarized for each slice, the low frequency power components of each individual event decreased with glutamate receptor antagonists (bottom panels labeled ii) of each section of Fig. 2). However, longer episodes of higher power materialize in the wavelet sonogram suggesting increased synchronization albeit at a lower frequency (Fig. 2 A and B). These results were further supported by the analysis of binned averaged power consumption of each individual LFP (Suppl. Fig. 2). In addition, spectral analysis revealed that averaged power consumption at the high frequency range (160–200 Hz) decreases (Suppl. Fig. 2).

Addition of GluR antagonists also significantly changed the initiation point from the CA3 stratum radiatum to the molecular and granule cell layers of DG. The number of events in a six minute window, 18 minutes after addition of GluR antagonists, initiating in CA3 was reduced from 26 ± 3 to 1.2 ± 0.73 (n= 131 and 6 events respectively, from at least 3 leads in 5 slices, p <0.01), a decrease of 95.6% while the number of events initiating in DG was increased from 0.2 ± 0.2 to 15 ± 5 (n= 1 to 73 events respectively, from at least 3 leads in n= 5 slices, p<0.05), an increase of three orders of magnitude (Fig 6, Suppl. movies 1 and 3). This indicates that events initiating in CA3 are dependent upon glutamatergic neurotransmission since CA3 events rarely initiate in CA3 after the addition of GluR antagonists. Furthermore, events that were generated in CA3 and limited in their propagation within this area were completely blocked by glutamate receptor antagonists.

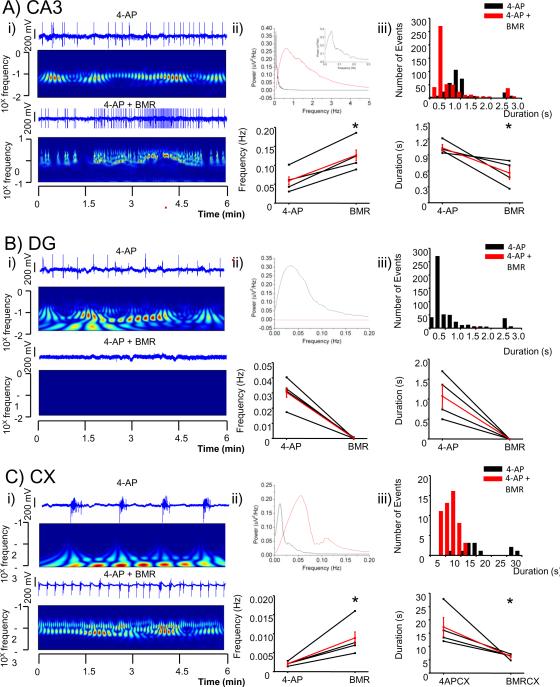

3.3. GABAAreceptor antagonism increases the frequency of events in neocortex and CA3 while inhibiting DG

Addition of the GABAA antagonist BMR (25μM), to the 4-AP containing ACSF, significantly increased the frequency of interictal-like events in CA3 from 0.06±0.01 Hz to 0.13±0.01 Hz (n= 4, p<0.05), an increase of 114%, and significantly decreased their duration from 1.03±0.06 s to 0.56±0.12 s (n= 4 slices, p<0.05), a decrease of 46±12% (Fig. 3A). Events in DG were completely blocked (Fig. 3B, Suppl. movies 3 and 4). GABAA receptor antagonism, as seen from the wavelet analysis in Fig. 3, increased the basal frequency but created multiple short episodes of higher power. Averaged binned power derived from each LFP (Suppl. Fig. 2) is also decreased in the low frequency range but surprisingly is reduced in the high frequency range with BMR as well.

Figure 3.

A GABAA receptor antagonist increases the frequency of LFPs and decreased their duration in CA3 and cortex while completely blocked activity in dentate gyrus.

A comparison of LFP recorded from a hippocampal slice from selected channels of a pMEA in the presence and the absence of BMR (25 μM).

i) Selected channel traces in each specified area (CA3 in A, DG in B and Cx in C) are shown over color coded power (wavelet analysis with frequencies plotted in a log scale; warmer colors indicate higher power) in the absence (top) and the presence of the drug (bottom).

ii) Top: overlaps of power spectra of traces shown in i) in each specified area (CA3 in A, DG in B and Cx in C). Bottom: plot of overall averages of peak frequencies derived from a pool of 3 channels in each selected area in the presence and absence of the drugs are shown together with the average in red from 4 slices. * p < 0.05 paired t-test. An expanded section of the power spectrum at low frequency is shown in A.

iii) Top: histogram of duration (bin size 0.2 s in CA3 and DG and 2 s in Cx) of LFPs derived from an aggregate of 3 channels in each selected area in the presence and absence of the drug. Bottom: plot of overall averages of durations in each selected area are shown together with the average in red from 4 slices. * p < 0.05 paired t-test.

The number of interictal-like events initiating in CA3 was increased significantly from 29±2 to 65±12 (n= 119 and 259 events respectively, from at least 3 leads in n= 4 slices, p<0.05), an increase of 118%, during BMR bath application (Fig. 6). The number of events that were limited to CA3 in their propagation also increased from 6.5±3.5 to 62±11 (n= 26 and 248 events respectively, from at least 3 leads in n= 4 slices, p<0.05), an increase of 854%, while the number of events propagating to DG decreased from 23±5 to 2.7±2.1 (n= 93 and 11 events respectively, from at least 3 leads in n= 4 slices, p<0.05), a decrease of 88%. Although no field potentials were detected with the frequency counting algorithm in DG after BMR addition, in the visual analysis of propagation an average of 2.7 ± 2.1 interictal-like events per slice in DG after the addition of BMR were seen suggesting a difference in the stringency of our methods although both results suggest a large inhibition of DG when GABAA receptors are blocked.

During BMR application, neocortical epileptiform discharges were also significantly increased in frequency from 0.002±0.0006 Hz to 0.009±0.002 Hz (n= 4 slices, p<0.05), an increase of 326%, and showed a trend towards a decrease in duration from 17± 4 s to 6.2±0.5 s (n= 4 slices, p= 0.07), a decrease of 64 ± 3% (Fig 3C). Thus, the increase in frequency of CA3 initiating and CA3-only propagating events after BMR suggests that intact GABAergic transmission controls the occurrence of field potentials in CA3 and their propagation into DG.

3.4. Contrasting effects of increasing phasic current vs. increasing tonic current

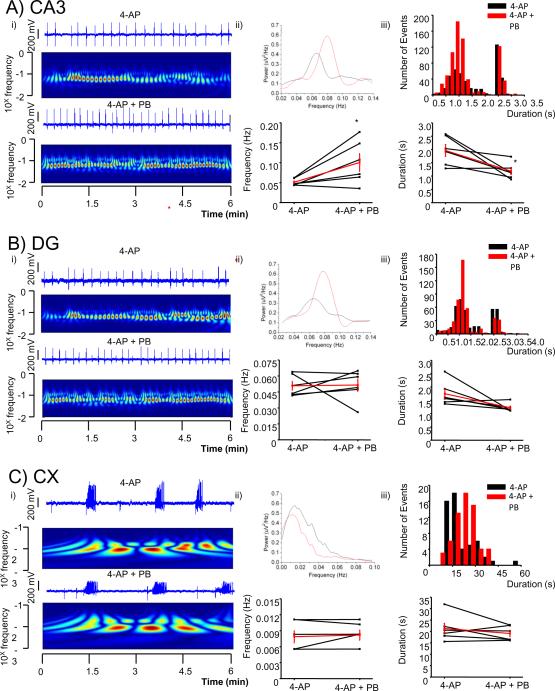

3.4.1. Potentiating synaptic GABAAR increases the frequency of events in CA3

It has been shown that potentiating GABAAR with the barbiturate PB (20μM) increases sharp-wave ripple events in CA3 (Ellender et al. 2010). PB potentiates both phasic and tonic currents (Choi et al 2008, Feng et al 2010, Wang et al 2010). Addition of PB to the 4-AP containing ACSF, significantly increased the frequency of interictal-like events in CA3 from 0.05 ± 0.003 to 0.10±0.02 Hz (n= 6, p<0.05), an increase of 978±44% and significantly decreased their duration from 2.0±0.2 to 1.2±0.1 s (n= 6, p <0.05), a decrease of 40% (Fig 4A). PB did not affect the frequency or duration of field potentials in DG or CX (Fig 4A and B).

Figure 4.

A barbiturate increased the frequency and decreased duration of LFPs recorded from CA3 but not those in dentate gyrus or cortex.

A comparison of LFP recorded from a hippocampal slice from selected channels of a pMEA in the presence and the absence of Pentobarbital (PB, 20 μM).

i) Selected channel traces in each specified area (CA3 in A, DG in B and Cx in C) are shown over color coded power (wavelet analysis with frequencies plotted in a log scale; warmer colors indicate higher power) in the absence (top) and the presence of the drug (bottom).

ii) Top: overlaps of power spectra of traces shown in i) in each specified area (CA3 in A, DG in B and Cx in C). Bottom: plot of overall averages of peak frequencies derived from a pool of 3 channels in each selected area in the presence and absence of the drugs are shown together with the average in red from 6 slices. * p < 0.05 paired t-test.

iii) Top: histogram of duration (bin size 0.2 s in CA3 and DG and 2 s in Cx) of LFPs derived from an aggregate of 3 channels in each selected area in the presence and absence of the drug. Bottom: plot of overall averages of durations in each selected area are shown together with the average in red from 6 slices. * p < 0.05 paired t-test.

Propagation and initiation within hippocampus was not affected significantly by the changes in frequency of CA3 (Fig. 6). Interestingly, like BMR, potentiating GABAARs with PB increased the frequency of CA3 field potentials. However, in contrast to when the GABAAR antagonist was applied, DG and neocortex were unaffected. As the interpretation of these findings is complicated by the fact that both phasic and tonic currents are potentiated with PB, we next addressed the role of tonic current in our experimental model.

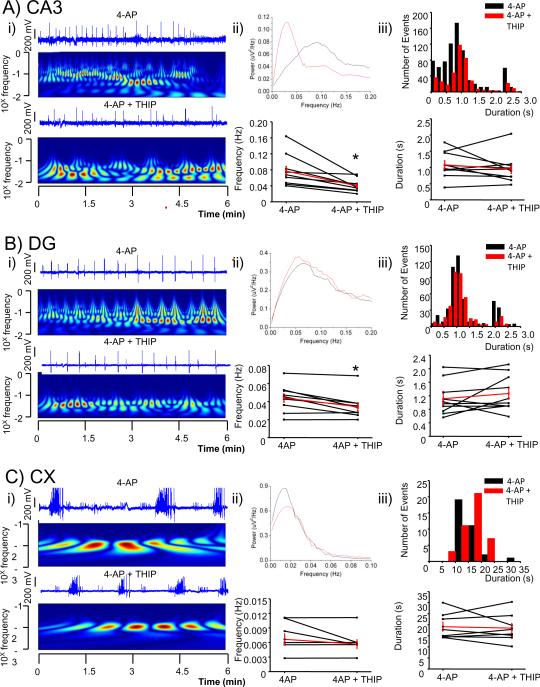

3.4.2 Tonic GABAAR activation decreases the frequency of events in CA3

In contrast to the effect of potentiating both phasic and tonic currents in which the frequency of events in CA3 is increased, addition of the δ-containing-GABAA receptor agonist, THIP (10 μM), which specifically activates the tonic current (Krook-Magnuson et al. 2008) to the 4-AP containing ACSF, significantly decreased the frequency of CA3 events from 0.07 ± 0.01Hz to 0.04± 0.005 Hz (n= 10, p <0.01), a decrease of 47% (Fig. 5A). However, although a trend towards increased duration was seen in CA3 and DG, it was not significant. Nevertheless, THIP significantly reduced the number of events restricted to CA3 from 13.1±2.4 to 2.3±1.29 (n= 131 and 23 interictal-like events respectively, from at least 3 leads in n= 5 slices, p<0.05) a decrease of 90%. THIP also reduced the number of events propagating to DG from 17.8±1.9 to 9.9±1.43 (n= 178 and 99 interictal-like events respectively, from at least 3 leads in n= 5 slices, p<0.05), a decrease of 44% (Fig 6). THIP did not have a significant effect on the initiation of signals within hippocampus. Similarly, THIP also reduced the frequency of interictal-like discharges in DG from 0.043±0.01 Hz to 0.034±0.01 Hz (n= 10, p<0.05), a decrease of 21% (Fig 5B) without significantly affecting durations. Cortical events were unaffected by THIP.

Figure 5.

Tonic GABAA receptor activation decreases the frequency of events in CA3.

Gaboxadol (THIP, 10 μM), a preferential agonist for tonically active GABAA receptor decreased the frequency of events in CA3 and dentate gyrus. Cortical activity was not affected. A comparison of LFP recorded from a hippocampal slice from selected channels of a pMEA in the presence and the absence of the drug.

i) Selected channel traces in each specified area (CA3 in A, DG in B and Cx in C) are shown over color coded power (wavelet analysis with frequencies plotted in a log scale; warmer colors indicate higher power) in the absence (top) and the presence of the drug (bottom).

ii) Top: overlaps of power spectra of traces shown in i) in each specified area (CA3 in A, DG in B and Cx in C). Bottom: plot of overall averages of peak frequencies derived from a pool of 3 channels in each selected area in the presence and absence of the drugs are shown together with the average in red from 10 slices. * p < 0.05 paired t-test.

iii) Top: histogram of duration (bin size 0.2 s in CA3 and DG and 2 s in Cx) of LFPs derived from an aggregate of 3 channels in each selected area in the presence and absence of the drug. Bottom: plot of overall averages of durations in each selected area are shown together with the average in red from 10 slices. * p < 0.05 paired t-test.

When compared, PB and THIP had almost an opposite effect. The effect of PB in CA3 was similar to that of BMR but it had no effect in DG. In contrast THIP decreased LFP occurrence in both CA3 and DG, similarly to the effect of the combination of CPP/NBQX, but it failed to significantly alter event duration. PB increases the occurrence of CA3-restricted LFPs while leaving the LFPs that initiate in CA3 and propagate to DG unaffected. This is compatible with the increase of LFP frequency and decreased duration in CA3 but not in DG. THIP also fails to alter LFPs propagating to DG but blocked LFPs originating in CA3, resulting in a decrease in the frequency of LFPs in both CA3 and DG.

4. Discussion

The role of GABA receptors in neuronal network synchronization has been widely recognized and is now central to the understanding of the mechanisms behind epileptogenicity. As previously reported (Avoli et al. 2002), an advantage to using the 4-AP in vitro epilepsy model to address this question is that it produces network synchronization while preserving GABAergic inhibition. Using multisite electrophysiological recordings with a pMEA we have reported here the changes in hippocampal excitability resulting from pharmacological manipulation of phasic and tonic GABAergic conductances. Our data are in partial agreement with previous studies (Avoli et al. 2002, Avoli et al 1993, Avoli et al 1996b, Avoli et al. 1998) that identified “fast-CA3-driven” and “slow” interictal discharges as the two major types of synchronous activity observed in the hippocampal areas of the slice. In addition, we also observed longer lasting, “ictal-like” activity in neocortical areas that did not propagate to the hippocampus due to the anatomical constraints of our preparation.

Interictal-like events were more abundant in CA3 leads than in the DG. The cocktail of glutamate receptor antagonists reduced the frequency of these events and induced a significant increase in their duration in both CA3 and DG. These results were supported by wavelet spectral analysis as well as binned averaged power that further suggested an increased synchronization, albeit at a lower frequency. However, spectral analysis of individual LFPs at the high frequency range (160–200 Hz) showed a decrease with glutamate antagonists, consistent with the hypothesis that fast interictal-like LFPs, or those originating in CA3 in our study, are due to recurrent excitatory connections in CA3 pyramidal neurons (Avoli et al. 2002; Dzhala and Staley, 2003).

We also observed LFPs that became prevalent in DG leads when glutamatergic activity was blocked; these events have a low frequency of occurrence and longer durations than CA3-driven glutamatergic interictal-like events. Therefore, DG can independently generate field potentials but when CA3 activity is present they are synchronized with events initiating in CA3. As seen in the wavelet analysis, CPP/NBQX treatment decreased basal frequency and created longer episodes at lower power, suggesting less frequent but longer lasting synchrony, possibly between GABAergic interneurons since glutamatergic activity is blocked.

Wavelet analysis also suggested that GABAA receptor antagonism increased the basal frequency in CA3 and created short episodes with higher power, suggesting more frequent but shorter-lasting synchrony. Similar results have been reported both in the 4-AP model (Lopantsev and Avoli 1998a) as well as in the 8.5 mM KCl model (Dzhala et al 2003). Averaged binned power was also decreased both in the low frequency range but surprisingly it was also reduced in the high frequency range. One intriguing possibility is that the GABAA receptor antagonist BMR silences several neuronal populations. The increase in frequency of LFPs restricted to CA3 after BMR, suggests that intact GABAergic transmission controls their occurrence. Events originating in DG are also depended on GABAergic transmission as they are silenced when the GABAA antagonist is applied. This implies a role for hilar commissural projection interneurons synapsing onto dentate granule cells in mediating population events in DG (Witter and Amaral, 2004; Scharfman, 2007).

The use of the pMEA allows for the study of both initiation and propagation of the synchronous LFP as seen in Fig 6 and the supplemental movies. Strikingly the main effect of the GluR antagonists is a significant change in site of initiation from CA3 to DG, due to the predominance of BMR-sensitive events in DG. The GABAA receptor antagonist resulted in the failure of propagation from CA3 to dentate gyrus. This supports the hypothesis that the source of fast interictal-like discharges and high frequency oscillation are CA3 pyramidal cells (Avoli et al 2002, Dzhala et al 2003, Ellender et al. 2010). Together, these findings suggests that there are two types of synchrony occurring in hippocampus, the “fast” interictal-like events that originate in CA3 and trigger events in DG, and the slower interictal-like LFPs, which are prevalent in DG and are silenced by GABAA antagonists. CA3 activity occurs more frequently and the majority of these events propagate to DG. However, when GluR antagonists are applied, CA3 no longer initiates the events, and instead DG synchronizes first and in turn these events propagate to CA3. Thus, both CA3 and DG are capable of generating LFPs, and these synchronous events can propagate to the neighboring structure. It should be noted that signals initiating in the highly epileptogenic CA3 area can propagate back to the molecular layer and excite granule cells in DG via the commissural/associational projections to the inner 3rd of the dentate molecular layer that arise exclusively from large neurons in the dentate hilus (Witter and Amaral, 2004). Moreover, although the CA3 area does not have robust excitatory influence on DG granule cells, in the presence of 4AP and possibly in pathological conditions, the balance between mossy cell and GABAergic interneurons is altered allowing CA3 outputs influence DG activity (Scharfman, 2007).

The expression of tonic current in hippocampal neurons (Scimemi et al., 2005; Semyanov et. al 2003; Mann and Mody 2009; Wyeth et al 2010) prompted us to compare the action of two compounds that differentially affect GABAergic mechanisms: THIP, a preferential agonist for extrasynaptic GABAA receptors, and PB that enhances the synaptic action of GABA (Choi et al 2008, Ellender et al. 2010, Feng et al 2010, Wang et al 2010). PB increased the frequency of interictal-like events in CA3 only suggesting that GABAergic transmission in CA3 is excitatory in juvenile animals as has been seen in other hippocampal preparations (Ellender et al. 2010). THIP, in contrast, inhibited LFPs both in CA3 and DG highlighting the role of tonic current in neuronal excitability and leading to a decreased level of synchronization in CA3.

The effect of PB and THIP suggest that GABA controls the activity of CA3 pyramidal neurons and, their recurrent afferents via both tonic and synaptic conductance. This is crucial to the network effect of these GABA modulators, as this is associated with the CA3-restricted LFPs. However our results also suggest an effect of these drugs on GABAergic interneurons, which may mediate propagation into and initiation in DG when excitatory neurotransmission is blocked. Thus all three treatments of CPP/NBQX, PB, and THIP may differentially affect inhibitory interneurons regulating DG excitability. However, one should also consider the reported selective PB antagonism on Ca2+-impermeable AMPA receptors (Yamkura. et al. 1995) predominant in pyramidal neurons. Although observed at high concentration, reduction of AMPA currents would preferentially inhibit excitatory recurrent synapses among CA3 in addition to silencing GABAergic interneurons. Further studies with single cell recording resolution combined with pMEA recordings should clarify these issues.

Although our study focused on the frequency, duration, initiation, and propagation of interictal-like discharges in the hippocampus using coronal slices, we also detected an independent neocortical activity. As reported for the entorhinal cortex and the juvenile hippocampus (Avoli et al. 2002, Avoli et al 1993, Avoli et al 1996b, Avoli et al. 1998) this activity consisted of repetitive LFPs lasting for a few seconds that were completely antagonized by glutamate receptor antagonists and reduced in duration but enhanced in frequency and amplitude by BMR. In contrast to the hippocampus the GABA current modulators, PB and THIP had no significant effects on these LFPs suggesting a profoundly different network regulation by GABA between these two areas in the 4-AP model.

In summary, MEA recordings allowed us to describe in detail the electrophysiological and pharmacological properties of previously reported synchronous epileptiform discharges induced by 4-AP in an in vitro hippocampus-neocortical slice preparation. Our results point to phasic and tonic GABA currents as important regulators of synchronous epileptiform discharges in CA3 with contrasting affects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by the Luce Foundation (RD, JW), the NIH (SV), the CONACyT of the Mexican Government (Scholarship number: 209104) (AGS), the NSF PIRE grant (0730255) (AGS), the CIHR (MA) and the Savoy Foundation (MA).

Abbreviations

- 4-AP

4-aminopyridine

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate

- BMR

bicuculline methobromide

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- CPP

3-(2-Carboxypiperazin-4-yl)propyl-1-phosphonic acid

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartic acid

- NBQX

2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione

- pMEA

perforated multi-electrode array

- THIP

4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol.

- LFP

local field potential

- PB

pentobarbital

- CX

neocortex

- DG

dentate gyrus DG

- GluR

glutamate receptors

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image processing with image. J. Biophotonics Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, D'Antuono M, Louvel J, Kohling R, Biagini G, Pumain R, D'Arcangelo G, Tancredi V. Network pharmachological mechanisms leading to epileptiform synchronization in the limbic system in vitro. Progr Neurobiol. 2002;68:167–207. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Louvel J, Kurcewicz I, Pumain R, Barbarosie M. Extracellular free potassium and calcium during synchronous activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in the immature rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1996a;493:707–717. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Barbarosie M, Lücke A, Nagao T, Lopantsev V, Köhling R. Synchronous GABA-mediated potentials and epileptiform discharges in the rat limbic system in vitro. J. Neurosci. 1996b;16:3912–3924. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03912.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Methot M, Kwawasaki H. GABA-dependent generation of ectopic action potentials in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998;10:2714–2722. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Psarropoulou C, Tancredi V, Fueta Y. On the synchronous activity induced by 4aminopyridine in the CA3 subfield of juvenile rat hippocampus. J Neurophys. 1993;70:1018–1027. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.3.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagini G, Panuccio G, Avoli M. Neurosteroids and epilepsy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2010;23:170–176. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833735cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen I, Navarro V, Clemenceau S, Baulac M, Miles R. On the Origin of Interictal Activity in Human Temporal Lobe Epilepsy in Vitro. Science. 2002;298:1418–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.1076510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D, Weizhen W, Deitchman KJ, Kharazia VN, Lesscher HMB, McMahon T, Wang D, Qi Z, Sieghart W, Zhan C, Shokat KM, Mody I, Messing RO. Protein kinase Cð regulates ethanol intoxication and enhancement of GABA-stimulated tonic current. J Neurosci. 2010;28:11890–11899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3156-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Prida LM, Huberfeld G, Cohen I, Miles R. Threshold behavior in the initiation of hippocampal population bursts. Neuron. 2006;49:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhala VI, Staley KJ. Excitatory actions of endogenously released GABA contribute to initiation of ictal epileptiform activity in the developing hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1840–1846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01840.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egert U, Heck D, Aertsen A. Two-dimensional monitoring of spiking networks in acute brain slices. Experimental Brain Research. 2002a;142:268–274. doi: 10.1007/s00221-001-0932-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egert U, Knott T, Schwarz C, Nawrot M, Brandt A, Rotter S. MEA-tools: an open source toolbox for the analysis of multi-electrode data with MATLAB. J Neurosci Methods. 2002b;117:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egert U, Okujeni S, Nisch W, Boven K-H, Rudorf R, Gottschlich N, Stett A. Perforated Microelectrode Arrays Optimize Oxygen Availability and Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Brain Slice Recordings. 2005 Abstract at the MST Kongress. [Google Scholar]

- Ellender TJ, Nissen W, Colgin LL, Mann EO, Paulsen O. Priming of hippocampal population bursts by individual perisomatic-targeting interneurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5979–5991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3962-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABAA receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H, Macdonald RL. Barbiturates require the N terminus and first transmembrane domain of the ð subunit for enhancement of α1β3δ GABAA receptor currents. JBC. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.122564. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch B, Qashu F, Figueiredo TH, Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, Rogawski MA, Braga MF. Pathological alterations in GABAergic interneurons and reduced tonic inhibition in the basolateral amygdala during epileptogenesis. Neuroscience. 2009;163:415–429. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AJ, Jones NA, Williams CM, Stephens GJ, Whalley BJ. Development of multi-electrode array screening for anticonvulsants in acute rat brain slices. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;18:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Brunig I. Formation and plasticity of GABAergic synapses: physiological mechanisms and pathophysiological implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;98:299–323. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Mann EO, Mody I. Which GABAA receptor subunits are necessary for tonic inhibition in the hippocampus? J Neurosci. 2008;26:1421–1426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4751-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopantsev V, Avoli M. Participation of GABAA-mediated inhibition in ictal-like discharges in the rat entorhinal cortex. J Neurophysiology. 1998;79:352–360. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen A, Glykys J, Maguire J. Seizures and enhanced cortical GABAergic inhibition in two mouse models of human autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:19152–19157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608215103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krook-Magnuson EI, Li P, Paluszkiewicz SM, Huntsman M. Tonically active inhibition selectively controls feedforward circuits in mouse barrel cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:932–44. doi: 10.1152/jn.01360.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald RL, Olsen RW. GABAA receptor trafficking, channel activity, and functional plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:569–602. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann EO, Mody I. Control of hippocampal gamma oscillation frequency by tonic inhibition and excitation of interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 2009;13:205–213. doi: 10.1038/nn.2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praxinos G. The rat nervous system. Academic Press; 2004. chapter 21 – hippocampal formation. [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE. The CA3 “backprojection” to the dentate gyrus. Prog. Brain. Res. 2007;163:627–637. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63034-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scimemi A, Semyanov A, Sperk G, Kullman D, Walker M. Multiple and plastic receptors mediate tonic GABAA receptor currents in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2005;15:10016–10024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2520-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semyanov A, Walker MC, Kullman D. GABA Uptake Regulates Cortical Excitability Via Cell Type-Specific Tonic Inhibition. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6:484–490. doi: 10.1038/nn1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Rahman M, Johansson I, Bäckström T. Agonist function of the recombinant α4β3δ GABAA receptor is dependent on the human and rat variants of the α4-subnit. Clin and Exp Pharm and Phys. 2010;37:662–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2010.05374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter MP, Amaral DG. Hippocampal Formation. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego: 2004. pp. 637–703. [Google Scholar]

- Wyeth MS, Zhang N, Mody I, Houser CR. Selective reduction of cholecystokinin-positive basket cell innervation in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2010;30:8993–9006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1183-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamkura T, Sakimura K, Mishina M, Shimoji K. The sensitivity of AMPA selective glutamate receptor channels to pentobarbital is determined by a single amino acid residue of the alpha2 subunit. FEBS Lett. 1995;374:412–414. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan R, Nadler JV. Enahanced tonic GABA current in normotopic and hilar ectopic dentate granule cells after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:670–681. doi: 10.1152/jn.00147.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziburkus J, Cressman JR, Barreto E, Schiff SJ. Interneuron and pyramidal cell interplay during in vitro seizure-like events. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:3948–3954. doi: 10.1152/jn.01378.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.