Abstract

Searching for efficacious and safe agents for the chemoprevention and therapy of prostate cancer has become the top priority of research. The objective of this study was to determine the effects of a group of tanshinones from a Chinese herb Salvia Miltiorrhiza, cryptotanshinone (CT), tanshinone IIA (T2A) and tanshinone I (T1) on prostate cancer. The in vitro studies showed that these tanshinones inhibited the growth of human prostate cancer cell lines in a dose-dependent manner via cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induction. Among three compounds, T1 had the most potent activity with IC50s around 3–6µM. On the other hand, tanshinones had much less adverse effects on the growth of normal prostate epithelial cells. The epigenetic pathway focused array assay identified Aurora A kinase as a possible target of tanshinone actions. The expression of Aurora A was overexpressed in prostate cancer cell lines. Moreover, knockdown of Aurora A in prostate cancer cells significantly decreased cell growth. Tanshinones significantly down-regulated the Aurora A expression, suggesting Aurora A may be a functional target of tanshinones. Tanshinones, especially T1, also showed potent anti-angiogenesis activity in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, T1 inhibited the growth of DU145 prostate tumor in mice associated with induction of apoptosis, decrease of proliferation, inhibition of angiogenesis and downregulation of Aurora A, whereas it did not alter food intake or body weight. Our results support that T1 may be an efficacious and safe chemopreventive or therapeutic agent against prostate cancer progression.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, tanshinones, Aurora A, angiogenesis, apoptosis, proliferation, chemoprevention

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer is the most common invasive malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer death in America men. Current therapeutic modalities for prostate cancer usually have variable effectiveness and develop metastasis and drug-resistance associated with high toxicity to normal tissues. Therefore, the searching for more effective regimens with minimal adverse effects for the chemopreventive intervention of prostate cancer remains the top priority in prostate cancer research.

The use of plants for medicinal purposes is as old as human history. All traditional and indigenous healing systems used natural products to treat or prevent disease. The use of medicinal botanical products is growing in the United States and many other countries. Most, if not all, traditional medical systems rely primarily on botanicals as a mainstay of therapy or prevention. Plants and other botanicals have also been the basis for most modern pharmaceutical drugs.

Herbal medicines usually contain multiple bioactive components with specific biological activities and are also used as alternative therapeutic or preventive regimens for individuals with cancer 1. Some of those herbal medicines have been used for centuries without demonstrating significant adverse effects on humans, thus their active ingredients could serve as efficacious and safe candidates for the prevention and/or therapy of cancer.

Danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge) has been widely used in traditional Chinese medicine practice for over a thousand years in the treatment of coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular diseases with minimal side effects 2. Cryptotanshinone (CT), Tanshinone IIA (T2A) and Tanshinone I (T1) are three major diterpene compounds of tanshinones in Danshen 2. In addition to their functions in cardiovascular systems, tanshinones have been recently shown to possess some activities against human cancer cells. T1 inhibited the growth of leukemia 3–6, lung 7 and breast cancer 8 in vitro in part via induction of apoptosis. T2A inhibited the growth of breast cancer 9, 10, nasopharyngeal carcinoma 11, glioma 12, leukemia 13 and hepatocellular carcinoma 14, 15 cells in vitro by induction of apoptosis 11, 14, and inhibited the growth of hepatic carcinoma 16 and breast tumor 9 in vivo. T2A also inhibited invasion of lung cancer cells in vitro 17. CT inhibited the growth of hepatocarcinoma cells 18 in vitro via cell cycle arrest at S phase and the growth of gastric and hepatocellular cancer cells. However, there is no report about the effect of tanshinones on prostate cancer.

The objectives of this study were to systematically evaluate tanshinones as potential chemopreventive and therapeutic candidates against prostate cancer progression by using both in vitro and in vivo systems. Our results provided convincing experimental evidence to support the future development of tanshinones, especially T1, as efficacious and safe agents for the prevention and/or therapy of prostate cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Tanshinones CT, T2A and T1 were purchased from LKT Laboratories (St. Paul, MN), and the purities were verified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Tissue culture media, fetal bovine serum (FBS), and trypsin were from Life Technologies, Inc. (Grand Island, NY). Propidium iodide (PI) was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); RNase A and 3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) were from Promega (Madison, WI). Antibodies used in Western blot against human antigens were cyclin B1, cdc2 and Bax (Oncogene Research Products, Boston, MA), Bcl-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), Aurora A (Cell Signaling, Beverly, CA), and β-actin (Merck Co., Darmstadt, Germany). Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry against human antigens were Ki67 and Factor VIII (Dako North America, Inc., Carpinteria, CA), and Aurora A (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA). Biotinylated anti-mouse/anti-rabbit IgG, Vectastain ABC kit and DAB substrate kit were from Vector Laboratories Inc. (Burlingame, CA)

Cell culture

Androgen-sensitive LNCaP and androgen-independent PC-3 and DU145 human prostate cancer cells from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Bethesda, MD) were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS and antibiotics in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Human normal prostate epithelial cells (PrEC) were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD) and cultured in PrEGM plus EGM-2 singlequotes (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Human umbilical vein epithelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD) and cultured in endothelia cell basal medium (EGM-2) plus EGM-2 singlequotes (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Cell growth assay

The effects of tanshinones on cell growth were determined by using Cell Titer 96 Aqueous One Solution Reagent, MTS (Promega) as we previously used 19. The experiments were repeated at least twice, each in triplicate.

Clonogenic survival assay

The effects of tanshinones on clonogenic survival of cancer cells were determined by a colony-forming assay following the method we described before 19. The experiments were done at least twice, each in duplicate.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells treated with different concentration of tanshinones were harvested, stained with PI and then analyzed by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Immunocytometry Systems, Mountview, CA) for cell cycle distribution according to the protocol we used before 20, 21.

Cell apoptosis detection

Cell apoptosis after treatment with tanshinones was determined by Annexin V-PI apoptosis detection kit. In brief, treated cells (1 × 105) were collected by trypsinization and centrifugation. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 500µl Annexin V binding buffer, to which 2.5µl Annexin V was added and incubated at room temperature for 15min; then 10µl propidium iodide was added for another 5min incubation in the dark. Apoptotic cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Immunocytometry Systems, Mountview, CA).

Cancer cell invasion assay

The effect of tanshinones on prostate cancer cell invasion was determined using a BD biocoat matrigel invasion chamber. PC-3 cells were starved overnight in serum-free medium and 200 µl of cell suspension (2.5 × 105 cells/ml) with or without tanshinones were added to the upper chamber. The lower chamber was filled up with 750 µl of NIH3T3 fibroblast conditioned media. The cells were incubated for 20 hrs at 37°C. After incubation, cells in the top well were removed carefully by swiping the cotton swabs and the cells on the underside of the membrane were stained using the Diff Quik (Dade Behring) stain kit, and quantified. The treatment was duplicated and the experiment was repeated at least twice.

Western blot analysis

Cells were treated with different concentrations of tanshinones, cell lysates were prepared, and protein expression was determined following the procedures we previously described 19, 21. The primary antibodies used were as follows: cyclin B1 (1:200), Cdc-2 (1:500), Bcl-2 (1:100), Bax (1:500), Aurora A (1:1000) and β-actin (1:10,000).

Epigenetic chromatin modification enzymes PCR array

The Human Epigenetic Chromatin Modification Enzymes RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD) was used to detect the expression of 84 key genes encoding enzymes known or predicted to modify genomic DNA and histone to regulate chromatin accessibility and therefore gene expression. The experiment was performed according to the vender’s instruction.

Quantitative real time reverse transcription-PCR

Total RNA was isolated by using Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). First-strand cDNA synthesis used 100ng random primer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1.0µg of total RNA, 10mM dNTP and 200 units of reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) per 20µl reaction. The sequences of primers used in this study are listed as follows:

β-actin forward 5’-GATGAGATTGGCATGGCTTT-3’, reverse 5’-CACCTTCACCGTTCCAGTTT-3’ with a product size of 100bp;

Aurora A forward 5’-CATCTTCCAGGAGGACCACT-3’, reverse 5’-CAAAGAACTCCAAGGCTCCA-3’ with a product size of 112bp.

PCRs were performed in duplicates in a 25µl final volume by using SYBR Green master mix from SABiosciences (Frederick), and the data were analyzed by using the same methods as described above.

Aurora A silencing by siRNA

The Aurora A silencing by siRNA followed the method described by Lentini and coworkers 22 with appropriate modifications. Briefly, 8×104 PC-3 cells were seeded in a 6 well plate and incubated for 24h. The silencer negative control and siRNA for Aurora A (Ambion, Austin, TX) were diluted in Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The final concentration of siRNA added to the cells was 33nM. The duplex siRNA sequence for Aurora A was as follows: 5’-AUGCCCUGUCUUACUGUCATT-3’.

In vitro angiogenesis assays

The HUVEC proliferation, migration and tube formation assays were used as the in vitro angiogenesis assays. HUVEC proliferation followed the MTS assay as described before 19.

For the endothelial cell migration assay, the BD fibronectin Biocoat 24-well chambers (3-µm pore size) were used. The lower chamber was loaded with 650 µl of complete medium (VEGF, PDGF and IGF-1 as chemo-attractants). The upper chamber wells were loaded with HUVEC cells (50,000 cells/well) in a 200µl of serum-free M199 medium with 0.1% bovine serum albumin. The cells were then treated with tanshinones or the vehicle and incubated for 5 hr at 37°C, and the migrated cells were measured following the method described in the cancer cell invasion assay.

For the tube formation assay, matrigel (BD Bioscience, City, CA) was added (50 µL) to each well of a 96-well plate and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr to solidify. A suspension of HUVEC cells (12500 cells) in EGM2 medium were seeded into each well and treated with tanshinones or the vehicle. After 18 hrs of incubation at 37°C, images were captured, and tubes formed were scored as follows: a three-branch point event was scored as one tube.

In vivo matrigel plug assay

The in vivo matrigel plug assay followed the protocol described by Huh and coworkers 23 with appropriate modifications. Male C57BL/6J mice (8-week-old) were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY), randomized into the Control or the T1 treatment group (n=8/group) and fed the AIN-93M diet. After two weeks of treatment with either the T1 (50 mg/kg BW, in corn oil) or the vehicle (corn oil) via gavage, each mouse was injected subcutaneously with 0.5 ml of matrigel (BD Sciences) and continued the treatment for 7 days. The mice were sacrificed and the matrigel plugs were excised and weighed. Hemoglobin levels in matrigel plugs were measured as an indication of blood vessel formation, using the Drabkin method (Sigma, St Louis). The concentration of hemoglobin was calculated from a hemoglobin standard curve.

Animal study

Male SCID mice (eight-week-old) were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY), and fed the AIN-93M diet for one week of adaptation. Mice were randomly assigned into 2 experimental groups (Control and T1 treatment), and each mouse was inoculated subcutaneously with 2 × 106 of PC-3 cells and treated with the assigned experimental treatment, either the vehicle (100µl corn oil) or T1 in corn oil at 150mg/kg BW by gavage daily. Food intake and body weight were measured weekly. The tumor diameters were measured weekly 21. At the end of the experiments, the mice were sacrificed; primary tumors were excised and weighed. A tumor slice from each primary tumor tissue was carefully dissected and fixed in 10% buffer-neutralized formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 4µm thickness for immunohistochemistry.

In situ detection of apoptotic index

Apoptotic cells were determined by a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (Chemicon International Inc, Billerica, MA) following our described protocols 20, 24. The staining was analyzed by using the Ivision imaging software (Biovision, Exton, PA).

Immunohistochemical determination of tumor cell proliferation

The proliferation index was evaluated by calculating the proportion of cells with Ki-67 staining, following the procedures in the laboratory 24.

Immunohistochemical determination of microvessel density

Microvessel density (MVD) was used as a marker for tumor angiogenesis and detected by immunohistochemical staining of Factor VIII following a method described previously 20, 24. Representative images were captured and the data was analyzed by the Ivision imaging software (Biovision).

Immunohistochemical staining of Aurora A

The expression level of Aurora A in the tumor tissue was detected by immunohistochemistry following the protocols described previously 20, 24 with appropriate modifications. Briefly, after deparaffinization, rehydration and washing, the section was treated with 0.1% trypsin for 45min for antigen retrieval. It was then incubated with diluted Aurora A antibody (1:200) overnight and then subjected to the secondary antibody incubation and staining procedures. Representative images were captured and analyzed by using the Ivision imaging software.

Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as group means±SEM and analyzed for statistical significance by analysis of variance followed by Fisher’s protected least-significant difference based on two-side comparisons among experimental groups by using Statview 5.0 program (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effects of tanshinones on the growth, clonogenic survival and invasion of prostate cancer cells in vitro

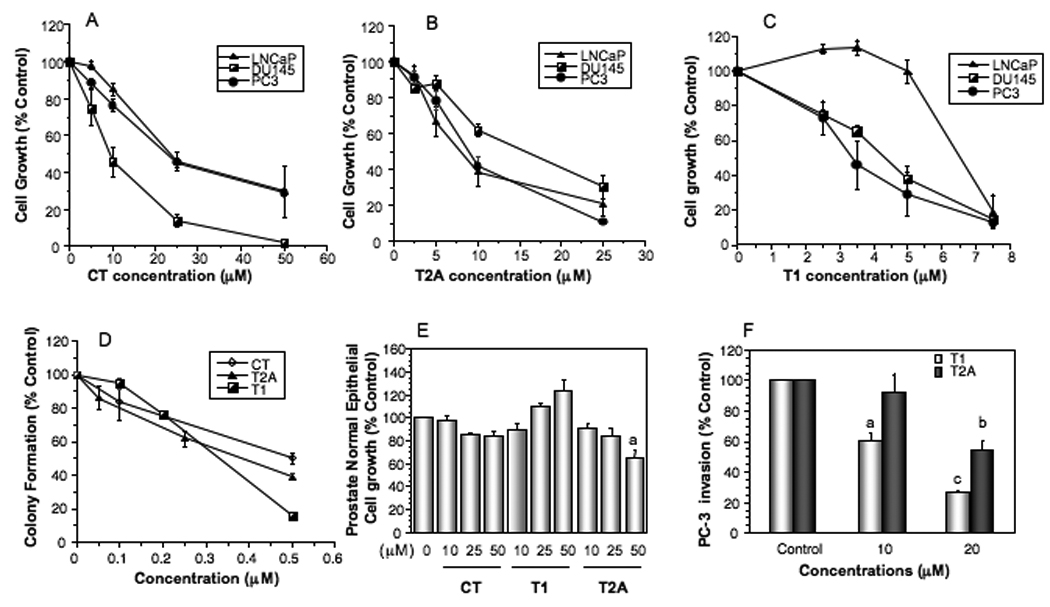

Tanshinones CT (Fig. 1A), T2A (Fig. 1B) and T1 (Fig. 1C) inhibited prostate cancer cell growth in a dose dependent manner. Among the three compounds, T1 showed the most potent activity with its IC50’s around 3–6.5µM, whereas the IC50’s of CT and T2A are around 10–25µM and 8–15µM, respectively, for different prostate cancer cell lines (Fig. 1A–C).

Figure 1.

Effects of tanshinones on the growth, colony formation and invasion of human prostate cancer cells and the growth of normal prostate epithelial cells in vitro. A–C, The dose-dependent effects of CT (A), T2A (B) and T1 (C) on the growth of androgen-sensitive LNCaP and androgen-independent DU145 and PC-3 cell lines. D, Effects of tanshinones on the growth of normal prostate epithelial cells (PrEC). E, Effects of tanshinones on colony formation of PC-3 cells. F, Effects of T2A and T1 on PC-3 cell invasion. Values are mean±SEM of three independent experiments in duplicate. Within the tanshinone treatment in each panel (E and F), the value with a letter is significantly different from that of the corresponding control, a, p<0.05; b, p<0.01; c, p<0.001.

We further examined the effects of CT, T2A and T1 on clonogenic survival of prostate cancer cells. Tanshinones significantly inhibited the colony formation of PC-3 (Fig. 1D) and other cell lines (LNCaP and DU145, data not shown). When compared to the growth inhibition assay, the colony formation was more sensitive (approximately 10 folds) to the treatment. On the other hand, tanshinones did not show significant cytotoxicity on normal prostate epithelial cells (PrEC) at the concentrations high as 50µM (Fig. 1E). The results suggest that tanshinones may have potent anti-growth effects on prostate cancer cells, but limited adverse effect on normal cells.

The effects of tanshinones on prostate cancer cell invasion were evaluated in highly invasive PC-3 cells. T2A and T1 inhibited PC-3 cell invasion in a dose-dependent manner, and T1 was more potent than T2A (Fig. 1F). At the current experimental conditions, T1 or T2A did not significantly inhibit the growth of PC-3 cells (data not shown).

Effects of tanshinones on PC-3 cell apoptosis in vitro

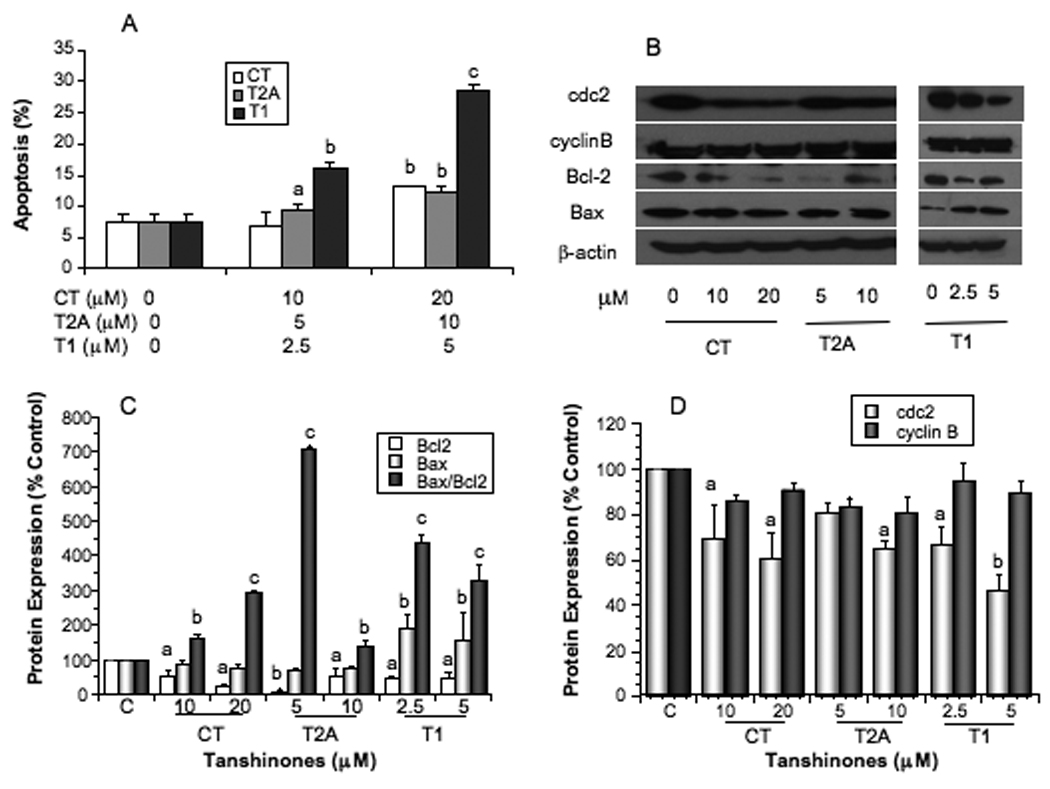

We used Annexin V-PI apoptosis detection kit to determine the effects of tanshinones on apoptosis induction of PC-3 cells. As shown in Fig. 2A, CT, T2A and T1 treatments induced apoptosis dose-dependently. Among three tanshinones, T1 was the most potent one in apoptosis induction and increased apoptosis by 6.5 folds at the concentration of 5µM.

Figure 2.

Effects of tanshinones on apoptosis of PC-3 cells measured by Annexin V-PI staining and flow cytometry (A), the expression of apoptosis related biomarkers bcl-2 and bax measured by Western blot (B) and quantified by densitometry after normalization to β-actin (C), and the expression of cell cycle related biomarkers cdc2 and cyclin B measured by Western blot (B) and quantified by densitometry after normalization to β-actin (D). Values are mean±SEM of three independent experiments in duplicate. Within the tanshinone treatment in each panel (A, C, or D), the value with a letter is significantly different from that of the corresponding control, a, p<0.05; b, p<0.01; c, p<0.001.

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms of tanshinones activities in apoptosis induction, we measured the expression of Bax and Bcl-2 proteins (Fig. 2B, 2C). All tanshinones significantly downregulated the expression of Bcl-2 (P at least <0.05) in PC-3 cells, however, only T1 significantly upregulated Bax expression (P at least <0.05). All tanshinones significantly increased the Bax/Bcl2 ratio, a more reliable indicator of apoptosis (Fig. 2C, P at least <0.05).

Effects of tanshinones on cell cycle progression in vitro

Cell cycle progression analysis showed that CT and T1 arrested cell cycle at S phase, whereas T2A arrested cell cycle at G2-M phases. Compared with the control PC-3 cells (30.56±0.95%), cells treated with 10 and 20µM CT increased the S phase proportion to 34.46±1.07% (P>0.05) and 37.08±2.49% (P<0.05), respectively. Similarly, cells treated with 2.5 and 5 µM T1 increased the S phase to 38.65±0.40% (P<0.05) and 39.87±1.37% (P<0.05), respectively. On the other hand, cells treated with 5 and 10 µM T2A increased the G2-M phase distribution to 32.97±1.45% (P<0.05) and 37.94±1.93% (P<0.05) respectively, compared with the control cells (28.68±3.66%).

We also measured the protein markers related to cell cycle progression, and the results showed that CT, T2A and T1 treatment significantly decreased the protein level of cdc2 (P<0.05) in a dose dependent manner, but did not significantly alter the expression of cyclin B (Fig. 2D).

Effects of tanshinones on the expression of epigenetic modification related genes in vitro

To identify the target genes of CT, T2A and T1, PC-3 cells were treated with 15µM CT, 7.5µM T2A, or 5µM T1, and then collected for the PCR array analysis. Only the genes with ∆∆Ct of 2 were considered as significant. Among the 84 genes related to epigenetic modification, 32 were down regulated by more than two folds after T1 treatment, including Aurora A kinase, DNA methyltransferase, Histone acetyltransferase, Histone deacetylase, Lysine (K)-specific demethylase, Protein arginine methyltransferase. However, CT or T2A treatment significantly downregulated only Aurora A kinase gene. The results suggest that Aurora A may be a potential molecular target of tanshinone actions.

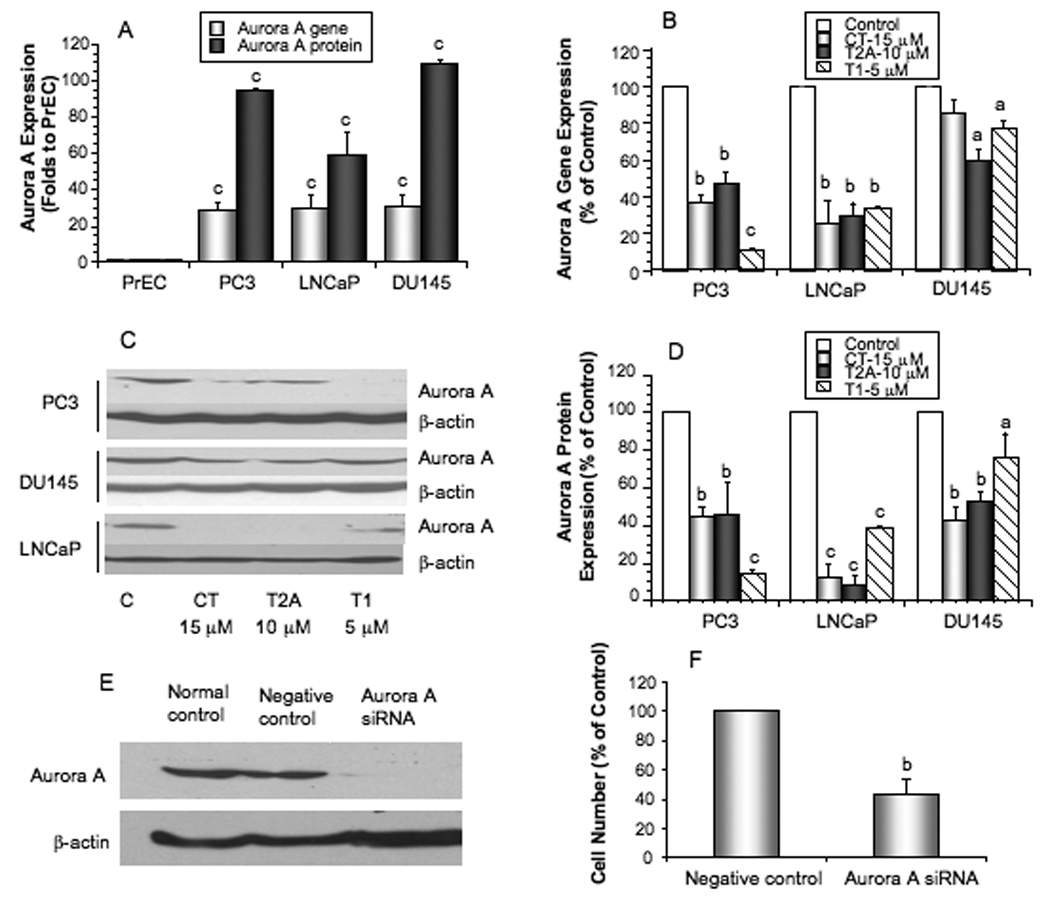

Effects of tanshinones on Aurora A expression in vitro

We compared Aurora A expression between normal prostate epithelial cells (PrEC) and prostate cancer cell lines. Compared with PrEC, prostate cancer cell lines (PC-3, LNCaP, and DU145) had significantly overexpressed levels of Aurora A gene and protein (Fig. 3A, P<0.001). Treatments of prostate cancer cell lines with tanshinones significantly downregulated the gene (Fig. 3B, P at least <0.05) and protein (Fig. 3C, 3D, P at least <0.05) levels of Aurora A.

Figure 3.

The gene and protein expression of Aurora A in prostate cancer cell lines and PrEC (A), the effects of tanshinones on the expression of Aurora A gene measured by real time PCR (B) and Aurora A proteins measured by Western blot (C) and quantified by densitometry (D), representative western blots showing the successful silencing of Aurora A by siRNA in PC-3 cells as confirmed by Western blot (E), and the effect of Aurora A knockdown on the growth of PC-3 cells (F). Values are mean±SEM of three independent experiments in duplicate. Within the panel, the value with a letter is significantly different from that of the corresponding control, a, p<0.05; b, p<0.01; c, p<0.001.

Aurora A function in prostate cancer cell growth in vitro

To determine the functional role of Aurora A in prostate cancer, we used Aurora A specific siRNA to downregulate its expression. Aurora A siRNA treatment effectively knocked down Aurora A protein level in PC-3 cells (Fig. 3E) by over 90%. Effective knockdown of Aurora A also significantly reduced the growth of PC-3 cells by over 50% (Fig. 3F, P<0.01). The results suggest that Aurora A play an important function in prostate cancer cell growth.

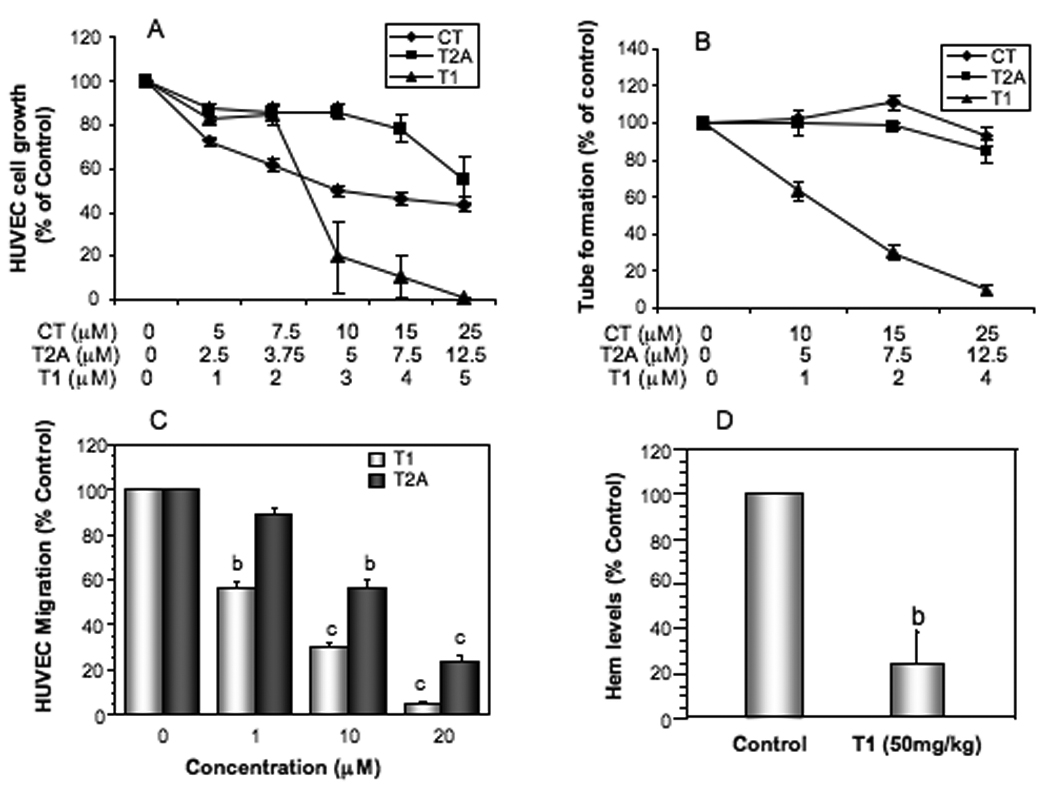

Effects of tanshinones on angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo

The HUVEC cell growth, migration and tube formation were used as the in vitro angiogenesis assays. CT, T2A and T1 had potent activities in inhibiting the growth of HUVEC cells in a dose-dependent manner, with the IC50s around 10µM, 15µM and 2.5µM, respectively (Fig. 4A). CT and T2A had no apparent effect on tube formation, but T1 had a very potent activity in inhibiting tube formation with the IC50 less than 1 µM (Fig. 4B). Tanshinones (T1 and T2A) also inhibited HUVEC migration in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4C). Since T1 showed the most potent anti-angiogenesis activity in vitro, its anti-angiogenesis activity was further evaluated in the in vivo matrigel plug assay. T1 treatment (50mg/kg BW) significantly inhibited angiogenesis by 80% (Fig. 4D, P<0.01). These results suggest that tanshinones, especially T1 may have potent anti-angiogenesis activity.

Figure 4.

Effects of tanshinones on the growth (A), tube formation (B) and migration (C) of human umbilical vein epithelial cells (HUVEC) in vitro, and the effect of T1 treatment at 50mg/kg BW on anti-angiogenesis in vivo measured by Matrigel Plug Assay (D). The in vitro values were mean±SEM of at least three independent experiments in duplicate. The in vivo values were the mean±SEM (n=8/group). The value with a letter is significantly different from that of the corresponding control, a, p<0.05; b, p<0.01; c, p<0.001.

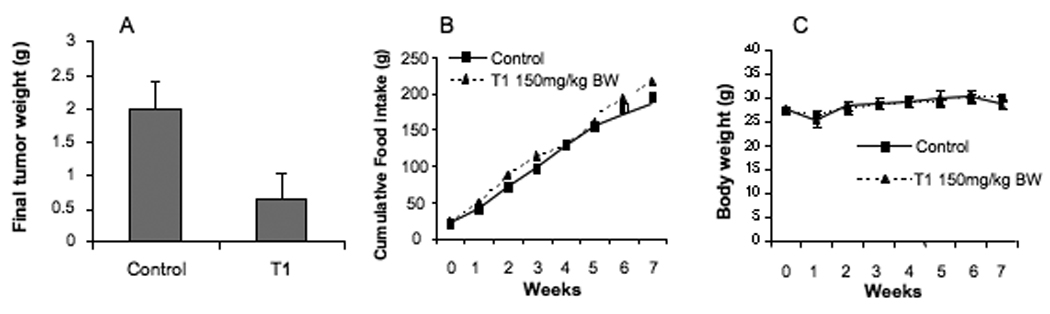

Effects of T1 treatment on DU145 tumor growth and modulation of tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis and Aurora A expression and tumor angiogenesis in vivo

Since T1 showed the most potent anti-prostate cancer cell growth in vitro and anti-angiogenesis activities in vitro and in vivo, we further evaluated the effect of T1 on prostate tumor growth in mice. As shown in Fig. 5A, T1 treatment (150mg/kg BW) significantly inhibited the final tumor weight by 67% (P<0.05). On the other hand, T1 did not significantly alter either food intake (Fig. 5B) or body weight (Fig. 5C), suggesting that T1 treatment had limited adverse effect on mice.

Figure 5.

Effects of T1 treatment at 150mg/kg BW on the growth of DU145 tumors in mice (A), food intake (B) and body weight (C). Values are group mean±SEM (n=6/group).

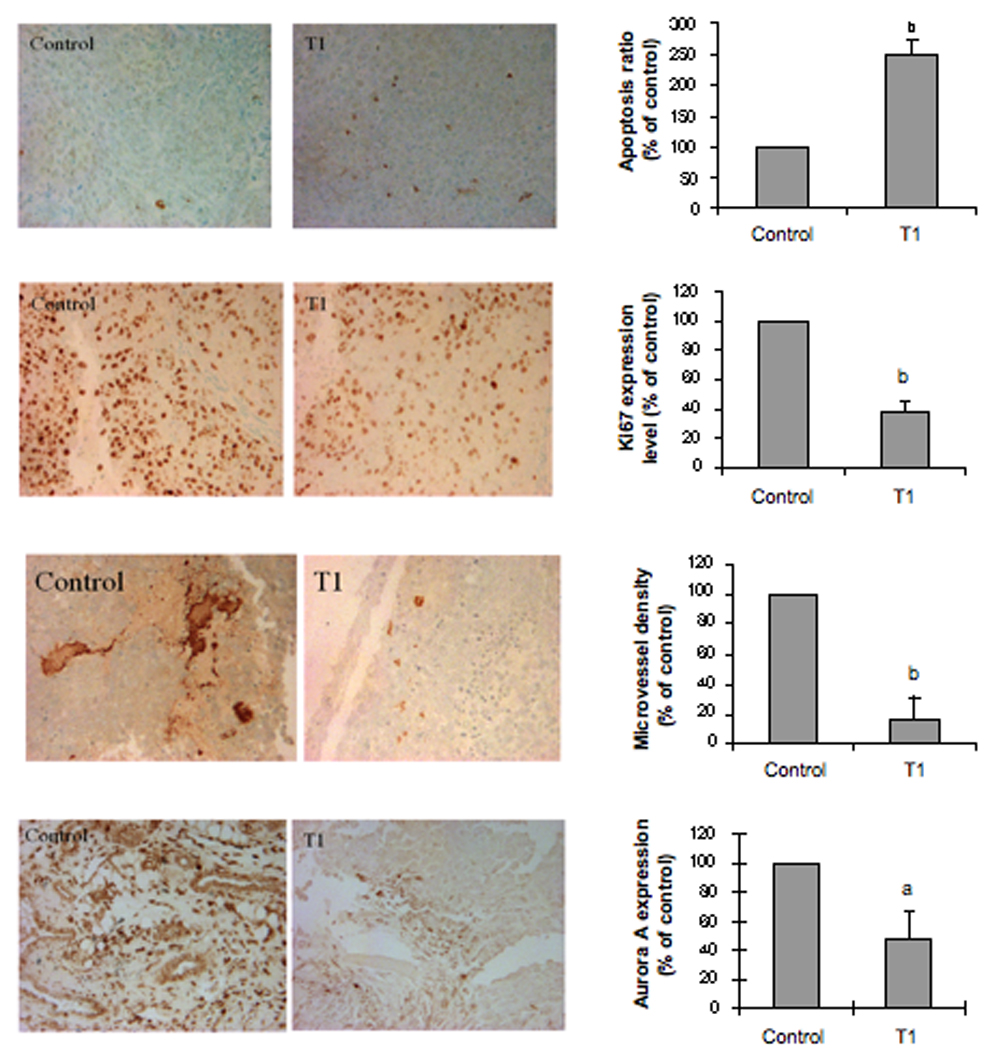

Analyses of cellular markers showed that the T1 treatment significantly induced prostate cancer cell apoptosis by 250% (Fig. 6A, P<0.01), reduced prostate cancer cell proliferation by 60 % (Fig. 6B, P<0.01) and inhibited prostate tumor angiogenesis by 80% (Fig. 6C, P<0.01). The T1 treatment also significantly reduced Aurora A protein expression by 60% in prostate tumors (Fig.6D, P<0.05). These results confirmed that T1 inhibited the growth of prostate tumors by inducing apoptosis, reducing proliferation and down-regulating Aurora A protein level of prostate cancer cells, and inhibiting prostate tumor angiogenesis in vivo.

Figure 6.

Effects of T1 treatment on DU145 tumor cell apoptosis index measured by TUNEL assay (A), tumor cell proliferation measured by immunohistochemical staining of ki-67 (B), tumor microvessel density measured by Factor VIII staining (C) and tumor cell expression of Aurora A measured by immunohistochemistry (D). For the analysis of immuno-staining, at least three representative areas of each section were selected, and the results were analyzed by using the Ivision-Mac imaging software. The data are expressed as the mean percentage of the control±SEM. The value with a letter is significantly different from that of the control, a, p<0.05; b, p<0.01; c, p<0.001.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we conducted a series of in vitro studies and found that tanshinones CT, T1 and T2A significantly inhibited the growth of both androgen-sensitive and androgen-independent human prostate cancer cell lines in part via induction of apoptosis, cell cycle arrest at S phase (CT and T1) or G2-M phase (T2A) and down-regulation of Aurora A expression. Knockdown of Aurora A by siRNA significantly reduced the growth rate of prostate cancer cells, suggesting that Aurora A may be a functional target for tanshinones. Tanshinones also inhibited angiogenesis in both the in vitro and in vivo assays. Among three tanshinones, T1 showed the most potent anti-growth, anti-invasion and anti-angiogenesis activities. The animal study further confirmed that T1 treatment significantly reduced the final tumor weight associated with induced prostate cancer cell apoptosis, reduced prostate cancer cell proliferation, down-regulated prostate cancer cell Aurora A protein expression and inhibited prostate tumor angiogenesis, without altering food intake or body weight. This is the first report, to the best of our knowledge, that a novel group of bioactive tanshinones, especially T1, had potent anti-prostate cancer and anti-angiogenesis activities against prostate cancer progression. It is also the first report to identify Aurora A as the functional target for tanshinones actions.

Because prostate cancer has long latency and its risk increases with age, chemopreventive strategies could be applied to effectively prevent or delay its progression. However, the outcome from the recent selenium and vitamin E cancer prevention trial (SELECT trial) has been disappointing 25. In the prostate cancer prevention trial (PCPT trial), finasteride, a 5α-reductase inhibitor, reduced the risk of prostate cancer by 24.8%, but was initially associated with increased risk of high-grade disease by 25.5% 26. Although reanalysis indicated that high-grade cancer was not associated with finasteride, the results may need further confirmation from another clinical trial, the Reduction by Dutasteride of prostate cancer events (REDUCE) trial 27. Therefore, there is an urgency to identify more promising safe and efficacious agents for prostate cancer chemoprevention. Our results from the systematic in vitro and in vivo studies strongly suggest that tanshinone T1 may have favorable efficacy and safety profiles and may serve as a promising chemopreventive agent against prostate cancer progression.

Despite previous findings that tanshinones had anti-cancer activities, the molecular mechanisms remain elusive. Our studies support that down-regulation of Aurora A may be an important molecular mechanism by which tanshinones possess chemopreventive activity against prostate cancer progression. Aurora kinases are a novel oncogenic family of mitotic serine/threonine kinases, which comprise three family members, Aurora-A, Aurora-B, and Aurora-C 28, 29. Aurora-A is localized on duplicated centrosomes and spindle poles during mitosis and is required for the timely entry into mitosis and proper formation of a bipolar mitotic spindle by regulating centrosome maturation, separation, and microtubule nucleation activity 30. Aurora A was frequently overexpressed in different types of cancers 22, 28, 31–33 and in prostate cancer 31, 34–37. Suppression of Aurora A expression and function reduced the prostate tumor growth and sensitized the activity of chemotherapeutic drugs 38. Thus Aurora A has been recognized as an important molecular target for cancer therapy 39, 40. Our studies demonstrated that tanshinones significantly down-regulated the gene and protein levels of Aurora A, supporting that Aurora A may be a novel molecular target for tanshinone actions.

Cellular mechanism studies showed that tanshinones inhibited the growth of prostate cancer cells in part via cell cycle arrest. Interestingly, CT and T1 arrested the cell cycle progression at S phase, whereas T2A did it at G2-M phases, in part via down-regulation of cdc2 expression levels (Fig. 2B, 2D). Cdc2, also known as CDK1 (cyclin dependent kinase), plays an important role during the cell cycle progress. CDK1 usually combines with Cyclin B and regulates the cell cycle progression at the S and G2-M phases. CDK1 phosphorylates motor proteins involved in centrosomes separation required for bipolar spindle assembly 41, and phosphorylates lamina inducing a destabilization of the nuclear structure leading to nuclear envelope breaks down 42. It also phosphorylates condensin contributing to chromosome condensation 43. Cdc2 has been considered as an essential molecular target for design of therapeutic anti-cancer drugs 44. Therefore, down-regulation of cdc2 may provide an important molecular mechanism that tanshinones modulate cell cycle progression of prostate cancer cells. Further investigation is needed to determine the mechanism by which tanshinones down-regulate cdc2 levels. Since Aurora A is essential for G2-M progression 22, 45 and knockdown of Aurora A results in G2-M arrest and eventual apoptosis 46, it is possible that the observed cell cycle arrest and down-regulation of cdc2 by tanshinones may be, at least in part, due to down-regulation of Aurora A. Indeed, Aurora A knockdown reduced cdk1 expression in human carcinoma cells 47.

Although we found that tanshinones downregulated cdc2 and Aurora A expression in prostate cancer cell lines, our results could not explain the different effects of tanshinones on regulating cell cycle phases, but instead suggested that these tanshinones might have other mechanisms on regulating cell cycle progression. Several regulatory markers, such as cyclin A, cyclin D, cyclin E, CDK2 and others, play roles in S-phase cell cycle progression. It is thus possible that tanshinones CT and T1, but not T2A, may specifically regulate the expression and function of S phase related biomarkers. This will be one of the future mechanistic studies.

Another cellular mechanism by which tanshinones inhibited the growth of prostate cancer cells might be via induction of apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. T1 showed the potent activity in inducing apoptosis of prostate cancer cells (Fig. 2A) in part via down-regulation of Bcl-2 and up-regulation of Bax levels in vitro (Fig. 2B, 2C). T1 also significantly induced apoptosis of DU145 tumor cells in vivo (Fig. 6). On the other hand, CT and T2A induced apoptosis of prostate cancer cells primarily via down-regulation of Bcl-2 (Fig. 2B, 2C). All treatment significantly increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, a more reliable indicator for apoptosis 48. Our results are consistent with that of previous in vitro studies showing that apoptosis induction was an important cellular mechanism of tanshinone actions in inhibiting the cell growth of different cancer types 8, 11, 14. We further provided the in vivo evidence to support that tanshinones induced apoptosis of prostate cancer cells.

The growth of all solid tumors is dependent on angiogenesis and suppression of tumor blood vessel offers a new option for the prevention and treatment of cancer 49. Our in vitro and in vivo studies also provided the convincing experimental evidence to support that one of the mechanisms by which tanshinones, especially T1 inhibited the growth of prostate cancer is by inhibition of angiogenesis. Among tanshinones, T1 showed the most potent anti-angiogenesis activity in vitro (Fig. 4) and significantly inhibited prostate tumor angiogenesis in vivo (Fig. 6). On the other hand, the molecular mechanisms that tanshinones inhibit angiogenesis remain unclear and should be the important area of research in the future.

In conclusion, the results from this study provided promising experimental evidence to support that T1 may be a novel efficacious and safe candidate agent for the chemoprevention and/or therapy of prostate cancer progression by induction of apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation of prostate cancer cells, and inhibition of prostate tumor angiogenesis. Our results also provided functional evidence to support that Aurora A may be a novel molecular target for tanshinones.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Supported by Idea Award PC073988 (Department of Defense) and R21 CA133865 (National Cancer Institute, NIH) to Dr. Zhou.

Abbreviations used are

- cdc2

cell division cycle-2

- CDK1

cyclin dependent kinase

- CT

Cryptotanshinone

- MVD

microvessel density

- PrEC

Prostate epithelial cells

- T2A

Tanshinone IIA

- T1

Tanshinone I

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling

REFERENCES

- 1.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou L, Zuo Z, Chow MS. Danshen: an overview of its chemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and clinical use. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:1345–1359. doi: 10.1177/0091270005282630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosaddik MA. In vitro cytotoxicity of tanshinones isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge against P388 lymphocytic leukemia cells. Phytomedicine. 2003;10:682–685. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song Y, Yuan SL, Yang YM, Wang XJ, Huang GQ. Alteration of activities of telomerase in tanshinone IIA inducing apoptosis of the leukemia cells. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2005;30:207–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sung HJ, Choi SM, Yoon Y, An KS. Tanshinone IIA, an ingredient of Salvia miltiorrhiza BUNGE, induces apoptosis in human leukemia cell lines through the activation of caspase-3. Exp Mol Med. 1999;31:174–178. doi: 10.1038/emm.1999.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon Y, Kim YO, Jeon WK, Park HJ, Sung HJ. Tanshinone IIA isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza BUNGE induced apoptosis in HL60 human premyelocytic leukemia cell line. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;68:121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CY, Sher HF, Chen HW, Liu CC, Chen CH, Lin CS, Yang PC, Tsay HS, Chen JJ. Anticancer effects of tanshinone I in human non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3527–3538. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nizamutdinova IT, Lee GW, Son KH, Jeon SJ, Kang SS, Kim YS, Lee JH, Seo HG, Chang KC, Kim HJ. Tanshinone I effectively induces apoptosis in estrogen receptor-positive (MCF-7) and estrogen receptor-negative (MDA-MB-231) breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Wei Y, Yuan S, Liu G, Lu Y, Zhang J, Wang W. Potential anticancer activity of tanshinone IIA against human breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:799–807. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su CC, Lin YH. Tanshinone IIA inhibits human breast cancer cells through increased Bax to Bcl-xL ratios. Int J Mol Med. 2008;22:357–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan S, Wang Y, Chen X, Song Y, Yang Y. A study on apoptosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line induced by Tanshinone II A and its molecular mechanism. Hua Xi Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2002;33:84–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Wang X, Jiang S, Yuan S, Lin P, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang Q, Xiong Z, Wu Y, Ren J, Yang H. Growth inhibition and induction of apoptosis and differentiation of tanshinone IIA in human glioma cells. J Neurooncol. 2007;82:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu JJ, Zhang Y, Lin DJ, Xiao RZ. Tanshinone IIA inhibits leukemia THP-1 cell growth by induction of apoptosis. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:1075–1081. doi: 10.3892/or_00000326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan SL, Wei YQ, Wang XJ, Xiao F, Li SF, Zhang J. Growth inhibition and apoptosis induction of tanshinone II-A on human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2024–2028. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i14.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Yuan S, Huang R, Song Y. An observation of the effect of tanshinone on cancer cell proliferation by Brdu and PCNA labeling. Hua Xi Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 1996;27:388–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Yuan S, Wang C. A preliminary study of the anti-cancer effect of tanshinone on hepatic carcinoma and its mechanism of action in mice. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 1996;18:412–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang P, Pei Y, Qi Y. Influence of blood-activating drugs on adhesion and invasion of cells in lung cancer patients. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 1999;19:103–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee WY, Chiu LC, Yeung JH. Cytotoxicity of major tanshinones isolated from Danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza) on HepG2 cells in relation to glutathione perturbation. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh AV, Franke AA, Blackburn GL, Zhou JR. Soy phytochemicals prevent orthotopic growth and metastasis of bladder cancer in mice by alterations of cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis and tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1851–1858. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou J-R, Mukherjee P, Gugger ET, Tanaka T, Blackburn GL, Clinton SK. The inhibition of murine bladder tumorigenesis by soy isoflavones via alterations in the cell cycle, apoptosis, and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5231–5238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mai Z, Blackburn GL, Zhou JR. Genistein sensitizes inhibitory effect of tamoxifen on the growth of estrogen receptor-positive and HER2-overexpressing human breast cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:534–542. doi: 10.1002/mc.20300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lentini L, Amato A, Schillaci T, Insalaco L, Di Leonardo A. Aurora-A transcriptional silencing and vincristine treatment show a synergistic effect in human tumor cells. Oncol Res. 2008;17:115–125. doi: 10.3727/096504008785055521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huh JE, Lee EO, Kim MS, Kang KS, Kim CH, Cha BC, Surh YJ, Kim SH. Penta-O-galloyl-beta-D-glucose suppresses tumor growth via inhibition of angiogenesis and stimulation of apoptosis: roles of cyclooxygenase-2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1436–1445. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou J-R, Yu L, Zerbini LF, Libermann TA, Blackburn GL. Progression to androgen-independent LNCaP human prostate tumors: cellular and molecular alterations. Int. J. Cancer. 2004;81:800–806. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, Lucia MS, Thompson IM, Ford LG, Parnes HL, Minasian LM, Gaziano JM, Hartline JA, Parsons JK, Bearden JD, 3rd, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) Jama. 2009;301:39–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lucia MS, Miller GJ, Ford LG, Lieber MM, Cespedes RD, Atkins JN, Lippman SM, Carlin SM, Ryan A, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N. Eng. J. Med. 2003;349:215–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomella LG. Chemoprevention using dutasteride: the REDUCE trial. Curr Opin Urol. 2005;15:29–32. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaestner P, Stolz A, Bastians H. Determinants for the efficiency of anticancer drugs targeting either Aurora-A or Aurora-B kinases in human colon carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2046–2056. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vankayalapati H, Bearss DJ, Saldanha JW, Munoz RM, Rojanala S, Von Hoff DD, Mahadevan D. Targeting aurora2 kinase in oncogenesis: a structural bioinformatics approach to target validation and rational drug design. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:283–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marumoto T, Zhang D, Saya H. Aurora-A - a guardian of poles. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:42–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qu Y, Zhang L, Mao M, Zhao F, Huang X, Yang C, Xiong Y, Mu D. Effects of DNAzymes targeting Aurora kinase A on the growth of human prostate cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;15:517–525. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Comperat E, Bieche I, Dargere D, Laurendeau I, Vieillefond A, Benoit G, Vidaud M, Camparo P, Capron F, Verret C, Cussenot O, Bedossa P, et al. Gene expression study of Aurora-A reveals implication during bladder carcinogenesis and increasing values in invasive urothelial cancer. Urology. 2008;72:873–877. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li D, Zhu J, Firozi PF, Abbruzzese JL, Evans DB, Cleary K, Friess H, Sen S. Overexpression of oncogenic STK15/BTAK/Aurora A kinase in human pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:991–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee EC, Frolov A, Li R, Ayala G, Greenberg NM. Targeting Aurora kinases for the treatment of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4996–5002. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matarasso N, Bar-Shira A, Rozovski U, Rosner S, Orr-Urtreger A. Functional analysis of the Aurora Kinase A Ile31 allelic variant in human prostate. Neoplasia. 2007;9:707–715. doi: 10.1593/neo.07322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qu Y, Zhang L, Mu DZ, Huang X, Wei DP, Zhao FY, Liu BL. Effect of aurora A on carcinogenesis of human prostate cancer. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2008;39:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buschhorn HM, Klein RR, Chambers SM, Hardy MC, Green S, Bearss D, Nagle RB. Aurora-A over-expression in high-grade PIN lesions and prostate cancer. Prostate. 2005;64:341–346. doi: 10.1002/pros.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumano M, Miyake H, Terakawa T, Furukawa J, Fujisawa M. Suppressed tumour growth and enhanced chemosensitivity by RNA interference targeting Aurora-A in the PC3 human prostate cancer model. BJU Int. 2010;106:121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dar AA, Goff LW, Majid S, Berlin J, El-Rifai W. Aurora kinase inhibitors--rising stars in cancer therapeutics? Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:268–278. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorgun G, Calabrese E, Hideshima T, Ecsedy J, Perrone G, Mani M, Ikeda H, Bianchi G, Hu Y, Cirstea D, Santo L, Tai YT, et al. A novel aurora-A kinase inhibitor MLN8237 induces cytotoxicity and cell cycle arrest in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blangy A, Lane HA, d'Herin P, Harper M, Kress M, Nigg EA. Phosphorylation by p34cdc2 regulates spindle association of human Eg5, a kinesin-related motor essential for bipolar spindle formation in vivo. Cell. 1995;83:1159–1169. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peter M, Nakagawa J, Doree M, Labbe JC, Nigg EA. In vitro disassembly of the nuclear lamina and M phase-specific phosphorylation of lamins by cdc2 kinase. Cell. 1990;61:591–602. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90471-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimura K, Hirano M, Kobayashi R, Hirano T. Phosphorylation and activation of 13S condensin by Cdc2 in vitro. Science. 1998;282:487–490. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perez de Castro I, de Carcer G, Montoya G, Malumbres M. Emerging cancer therapeutic opportunities by inhibiting mitotic kinases. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirota T, Kunitoku N, Sasayama T, Marumoto T, Zhang D, Nitta M, Hatakeyama K, Saya H. Aurora-A and an interacting activator, the LIM protein Ajuba, are required for mitotic commitment in human cells. Cell. 2003;114:585–598. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hata T, Furukawa T, Sunamura M, Egawa S, Motoi F, Ohmura N, Marumoto T, Saya H, Horii A. RNA interference targeting aurora kinase a suppresses tumor growth and enhances the taxane chemosensitivity in human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2899–2905. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sasayama T, Marumoto T, Kunitoku N, Zhang D, Tamaki N, Kohmura E, Saya H, Hirota T. Over-expression of Aurora-A targets cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein and promotes mRNA polyadenylation of Cdk1 and cyclin B1. Genes Cells. 2005;10:627–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Israels LG, Israels ED. Apoptosis. The Oncologist. 1999;4:332–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao Y. Angiogenesis: What can it offer for future medicine? Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1304–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]