Abstract

Obesity is an important risk factor for pharyngeal airway collapse in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). To examine the effect of obesity on pharyngeal airway size on inspiration and expiration, respiratory-gated MRI of the pharynx was compared in New Zealand Obese (NZO) and New Zealand white (NZW) mice (weights: 50.4g vs. 34.7g, p < 0.0001). Results: 1) pharyngeal airway cross-sectional area was greater during inspiration than expiration in NZO mice, but in NZW mice airway area was greater in expiration than inspiration; 2) inspiratory-to-expiratory changes in both mouse strains were largest in the caudal pharynx and 3) during expiration, airway size tended to be larger, though non-significantly, in NZW than NZO mice. The respiratory pattern differences are likely attributable to obesity that is the main difference between NZO and NZW mice. The data support an hypothesis that pharyngeal airway patency in obesity is dependent on inspiratory dilation and may be vulnerable to loss of neuromuscular pharyngeal activation.

Keywords: obstructive sleep apnea, magnetic resonance imaging, respiration, upper airway

1. Introduction

The pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is believed to be a complex interaction between anatomic factors that reduce pharyngeal airway size and stiffness and neurologic factors that reduce pharyngeal muscle activation during sleep. Obesity is the most important risk factor for OSA. Previous studies in rodents have shown that obese rats have reduced pharyngeal airway size and collapsibility compared to their lean littermates (Nakano et al., 2001; Brennick et al., 2006). The objective of this paper is to examine a murine model of obesity with a specific focus on the role of obesity on dynamic respiratory-related pharyngeal airway size variations.

Recent MRI studies from this laboratory have compared pharyngeal airway size in obese Zucker rats and their lean littermates (Brennick et al., 2006). During spontaneous breathing, pharyngeal airway cross-sectional area was greater during inspiration than expiration in both the obese and lean rats. However, the increase in cross-sectional area during inspiration in the lower pharyngeal airway was significantly greater in the lean compared to the obese animals.

Although both obese and lean Zucker rats showed pharyngeal airway dilation during inspiration, the same findings may not be present in obese and lean mice. In a recent study comparing one specific region of the pharyngeal airway in NZO (New Zealand obese) and NZW (New Zealand white) mice, we found that the airway of the obese NZO mouse dilated during inspiration, whereas in the lean NZW mouse, the upper airway was reduced in size during inspiration (Brennick et al., 2009). In that study we showed with a quantitative analysis based on MRI that the volume of pharyngeal soft tissue structures and associated fat deposits was greater in NZO compared to NZW mice. These findings might contribute to pharyngeal airway narrowing in the obese phenotype. However, while a comprehensive analysis of upper airway and whole body fat distribution was presented in that study, only one caudal part (1mm thick slice) of the pharyngeal airway was analyzed.

In the current study we used respiratory-gated MRI to acquire images during inspiration and expiration across all pharyngeal regions in NZO and NZW mice to compare upper airway cross-sectional area during inspiration and expiration. We hypothesized, that as seen previously in Zucker rats, obesity in NZO mice decreases overall (inspiratory and expiratory) pharyngeal airway size compared to NZW (non-obese) mice. In order to address this hypothesis, we compared pharyngeal airway size in inspiration and expiration in NZO and NZW mice. An additional objective was to examine whether the pattern of inspiratory dilation, as found in the both lean and obese Zucker rats, is present in obese and lean mouse strains. Partial results of this study have been presented in an abstract (Brennick et al., 2007) and data from spin-echo images, including respiratory data on a single pharyngeal slice from this group of mice have been published (Brennick et al., 2009).

2. Methods

2.1 General

With the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, MRI experiments were performed on 11 NZO and 13 NZW male mice. We used age-matched animals where the average age of NZO was 21.0 ± 2.9 (SD) weeks and NZW was 23.2 ± 3.4 weeks (Students’ t-test, p = 0.11). The mean weight for NZO mice (50.4 ± 4.0 g) was significantly greater than that of the NZW mice (34.7 ±1.3 g, Students’ t-test, p < 0.0001).

Anesthetized, spontaneously breathing mice were imaged using a gradient-recalled echo MRI respiratory-gated protocol that allowed for a time series of images (6 images, obtained at 75 ms intervals during respiration). These images were acquired in a contiguous stack of 12, with 1 mm thick axial slices throughout the entire pharyngeal airway. MRI was performed in a 50 mm diameter, custom-made (birdcage design) radio frequency (RF) volume coil. The RF transmit-receive coil was tuned to the resonant 200 MHz frequency of the 40 cm bore 4.7T magnet (Magnex, Concord), equipped with a 12 cm shielded gradient insert (gradients up to 25 g-cm−1) operated with a Varian INOVA console (Varian, Palo Alto).

Following anesthetic induction (2% isoflurane in oxygen), the mice were maintained on anesthetic gas (1.0 - 2.0% isoflurane in oxygen) through a facemask. The anesthetic gas was exhausted from the breathing mask (using a flow rate greater than minute ventilation) to an activated carbon filter (F’air, Houston, TX). The anesthetized mice were placed supine with the head centered in the RF coil in a custom cradle to stabilize the body. A monitoring system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY) was used that included a compliant pressure sensor (2 cm diameter pillow) positioned over the diaphragm and lower abdomen that generated a continuous wave form (showing diaphragmatic motion representing the respiratory cycle) and from this, a trigger signal initiated at the inspiratory phase was used for gating the MRI to the respiratory cycle. The physiological monitoring system also regulated core temperature at 37-8°C using a feedback-controlled warm air source coupled with a rectal thermistor.

Axial images were obtained on a 128 × 128 pixel matrix, field of view (FOV) = 32 × 32 mm; slice thickness = 1.0 mm; echo time (TE) = 3 ms; image acquisition time (for three slices = 12 ms). Repetition time (TR) was equivalent to the respiratory rate that ranged from 77.0 ± 13.8 to 71.9 ± 9.5 breaths per minute (mean ± SD for NZO to NZW respectively, p = 0.31).

2.2 Image Analysis - Temporal alignment

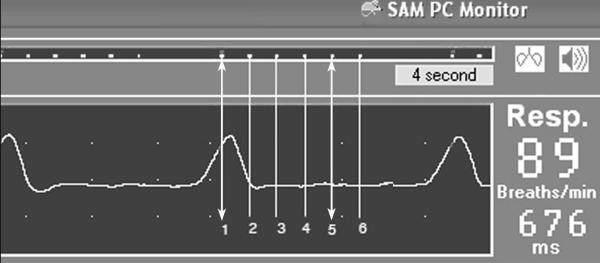

Figure 1 shows the respiratory pressure tracing and the timing of the gradient recalled echo image acquisitions during the respiratory cycle. Image acquisition was synchronized using a trigger actuated with the inspiratory (pressure pillow) monitoring signal. Thus, image 1 was acquired following the trigger during inspiration and the measured timing of the subsequent images (75 ms between each “red dot = image acquisition” Figure 1) showed that images 3-6 were acquired in expiration. To compare cross-sectional pharyngeal airway area during inspiration and expiration, two of the six images at each slice location were chosen, image number 1 at mid-inspiration (“inspiration”) and image number 5 at mid-expiration.

Figure 1.

Example of the chest wall movement signal used for respiratory-gated imaging. On the respiratory trace, there is one complete breath in the continuous readout where the respiratory rate averaged over several breaths was 89 breaths/min (676 ms per breath; monitor had 4 s sweep rate refresh). The respiratory signal moved upwards during inspiration and electronically triggered the start of the MRI acquisitions. Each dot, extended with the vertical lines, represents one the 6 phasic acquisitions during a respiratory cycle. The separation between image acquisition lines was 75 ms. Lines 1 and 5 (with double arrows) indicate the timing of images acquired at approximately mid-inspiration and mid-expiration.

Axial images of the pharynx were acquired in four acquisitions of 3 slices each (with 1 mm gap between slices). Obtaining only 3 slices at a time allowed a very short acquisition time (<12 ms) and minimized blurring. Although it would be possible to obtain all 12 locations in a single acquisition, the length of time would have been on the order 48 ms and that would be too long to obtain a clear airway image given the speed at which the pharynx changes size during respiration. The 4 sets of image acquisitions were merged to create a set of 12 axial images (each location having 6 images at 75 ms time intervals) spaced over the rostral to caudal length of the pharynx.

2.3 Image Analysis - Spatial Alignment

The mice were positioned in the MRI coil so that the head-to-neck angle was similar among all mice. The angle of the cervical spine to brain midline was measured on the scout images and was similar between the two groups of mice.

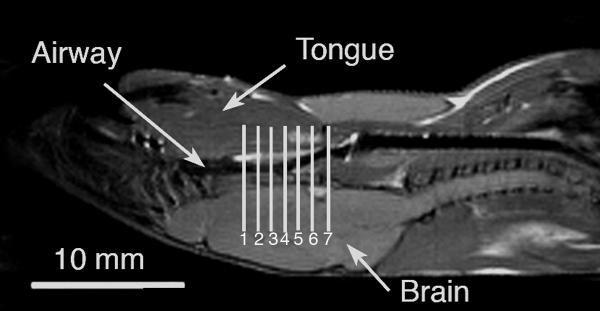

Twelve contiguous axial slices (1 mm thick) were acquired across the pharynx in order to properly align across mice the 7 slices from the region of interest described below. The axial slice which represented the most rostrally located image in which the tympanic bulla were first evident was used to align of the images across mice. The 7 slice locations, highlighted by the vertical lines in Figure 2, encompassed the pharynx (including nasopharynx and oropharynx, where it was existent) from the beginning of the junction of the hard to soft palate to just beyond the distal edge of the soft palate, in the region of the hypopharynx. These landmarks are comparable to human anatomy, although, the mouse does not have a large space between the distal edge of the soft palate and the epiglottis so the ‘hypopharynx’ in the mouse is a relatively smaller region than that in the human pharynx. The seven slices were numbered 1-7, where 1 was the most rostral.

Figure 2.

Mid-sagittal MRI of representative NZW mouse (in supine position) highlighting the locations (vertical lines) where 7 transverse axial MR images of the upper airway were obtained. A series of 6 respiratory-gated axial images were obtained at each location (Figure 4).

2.4 Airway Measurement

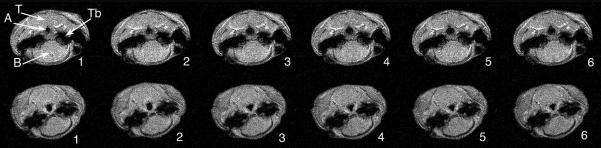

The airway in each of the inspiratory and expiratory axial slices in all 7 pharyngeal locations was measured using the public domain NIH Image-J program (U.S. National Institutes of Health, available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Figure 3 shows the axial images in the 7 pharyngeal locations for a representative NZW mouse during expiration. In this example there are some slice locations with both NP and OP airways and other slices where only one (NP) airway exists. Overall, in some slices in the mice, both the oropharyngeal (OP) and nasopharyngeal airspace (NP) were evident. Sometimes in the same mouse, the OP was open in one respiratory phase, e.g., expiration, but not in the other phase. Since these conditions were variable, we collected the data as: NP only measurements and total airway (NP + OP) measurements. In some cases in the caudal regions slightly beyond the soft palate, if only a single open airway was apparent, this was labeled NP since this would be the primary airway and functionally equivalent to the airway of the nasopharynx.

Figure 3.

Seven axial slices obtained during expiration in the pharyngeal region from the anatomical locations noted by the 7 vertical lines in Figure 2 are shown from a representative NZW mouse. The axial slices (numbered 1-7) represent 1 mm thick MRI gradient recalled acquisitions as described in the METHODS with slice 1 from the most rostral location and slice 7 from the most caudal location. Annotations include: a 1 cm scale bar, the brain (BR), tongue (Ton) and the two, tympanic bulla (TB) on slice 6. NP and OP airways are evident in slices 3, 4 and 5 and noted with arrows in slices 4 and 5.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

A mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences between inspiratory and expiratory size for: 7 regions (slice locations), in the NP + OP and NP (only) airspace, for the two phenotypes (NZW and NZO). The analysis of inspiratory and expiratory size changes during respiration was determined separately for each mouse phenotype. Post-hoc contrasts were adjusted for the set of planned comparisons e.g., inspiratory vs. expiratory changes in NP airspace in a specific region. This method provides strong control over Type I error while not being overly conservative (Winer et al., 1991; Littell et al., 1996). Within each mouse phenotype, the step-down Bonferroni multiple comparison test on post-hoc contrasts, was used for post-hoc comparisons (significance at p < 0.05).

A combined result defined in this study as “Delta” (expiratory cross-sectional area minus inspiratory cross-sectional area) was computed across the 7 regions in NZO and NZW mice and the results compared differences in airway size on inspiration vs. expiration. A negative Delta would indicate that airway size was greater on inspiration than expiration. Significant differences (p < 0.05, with step-down Bonferroni correction) on the regional (slice) level were noted between NZW and NZO.

3. Results

Figure 4 shows a representative set of 6 images from an NZW (top panel) and NZO mouse (bottom panel), obtained in the caudal pharynx (slice location 6 in Figure 2). In this image series, image 1 and 2 are during inspiration and images 3 to 6 were acquired during expiration (See Figure 1 for respiratory: image timing). In the NZW mouse, the inspiratory-timed images show reduced cross-sectional airway area compared to the expiratory images. In contrast, in the NZO mouse, the airway is larger on inspiration (images 1 and 2) than on expiration (images 3 to 6). A major difference in these regions is that the airway circumference in the caudal region primarily comprised of muscle and soft tissues whereas, in the mid- and rostral pharynx, i.e., the dorsal boundary of the nasopharyngeal airway, is supported by bone.

Figure 4.

Six axial slice images from same location in the pharynx in a representative NZW (top panel) and NZO mouse (bottom panel). Slice location #6 (see Figure 2) is displayed since that is a location where differences between NZO and NZW airways were most apparent. Images in each panel are numbered (1-6) corresponding to the numbered lines (time sequence of acquisition) in Figure 1. The axial images are displayed with the animal orientation (supine) so that the tongue (T) is superior and the brain (B) is inferior in the image. The two large dark circular structures lateral to the airway (A) are the tympanic bulla (Tb) that were used as a registration marker to orient axial images from rostral to caudal loci. Note that in the NZW mice (top panel), the inspiratory-timed images (1 and 2) show reduced cross-sectional airway area compared to the expiratory images (3 to 6). In contrast, in the NZO series (bottom panel) the inspiratory-timed images (1 and 2) showed an increase in cross-sectional area, while the expiratory images (3 to 6) were smaller.

Quicktime movies: Cinematic images of the dynamic behavior of the mouse pharynx at matched loci (in the hypopharyngeal region) are shown in two QuickTime movies (NZWAxial.mov and NZOAxial.mov). In the NZWAxial.mov the airway is reduced in size during inspiration (first and second images), and then enlarges in expiration (following 4 images). In the NZOAxial.mov, the airway is dilated in inspiration (first two images), and then becomes smaller during expiration (following 4 images).

Representative individual images from each movie are displayed in Figure 3 (top panel = NZW, bottom panel = NZO).

Cinematic images of the dynamic behavior of the caudal pharyngeal airway (slice location 6) from the NZO and NZW mice in Figure 3 are shown in two QuickTime movies (NZWAxial.mov and NZOAxial.mov). In the NZWAxial.mov the airway is reduced in size during inspiration (first and second images) then enlarges in expiration (following 4 images). In the NZOAxial.mov, the airway is dilated in inspiration (first two images) then becomes smaller during expiration (following 4 images).

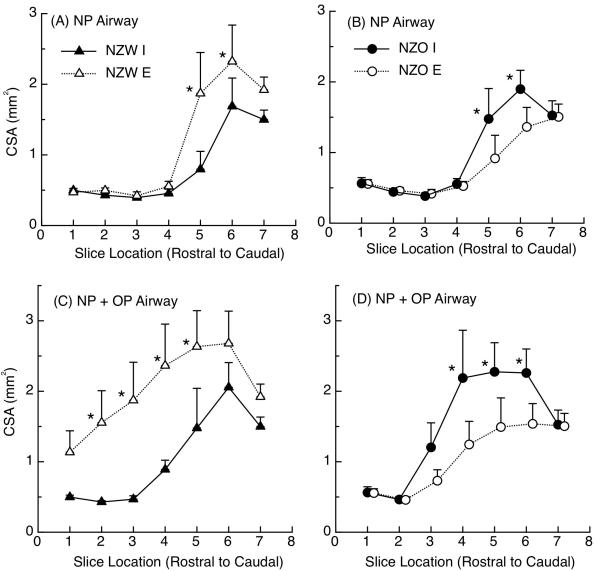

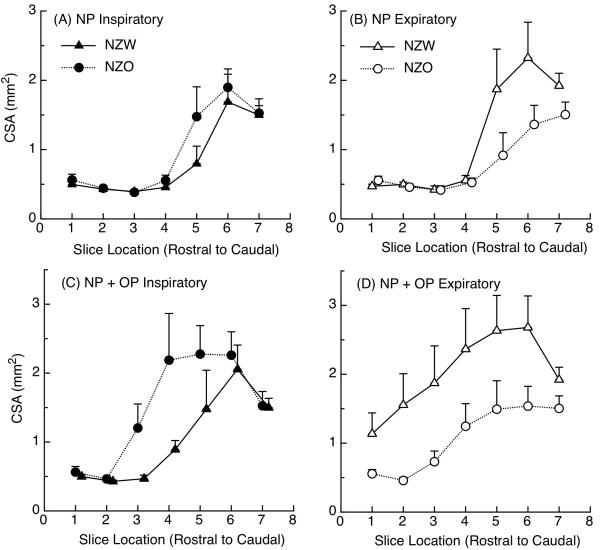

Figure 5 (A & B) shows the mean inspiratory and expiratory cross-sectional area in the NP airway in the NZW (A) and NZO mice (B) and Figure 5 (C &D) shows the mean inspiratory and expiratory cross-sectional area for NP + OP airway for NZW (C) and NZO (D) mice. ANOVA results for the NP airway showed the respiratory phasic difference (mean expiratory – mean inspiratory) in cross-sectional area was overall, significant when compared within a phenotype i.e., NZW (P < 0.001) and NZO mice (p < 0.005). Post-hoc testing to determine if any NP airway location had significant differences in airway area between inspiration and expiration showed that both NZW and NZO mice had a significant phasic respiratory-related differences at slice locations 5 and 6 (all p < 0.005). However, in the NZW mice, cross-sectional area was larger in expiration than inspiration, whereas in the NZO mice cross-sectional area was larger in inspiration than expiration.

Figure 5.

(A-D): Mean cross-sectional area (CSA) of the pharyngeal airway in (N = 13) NZW and (N = 11) NZO mice during mid-inspiratory and mid-expiratory phases of respiration. Panel A shows NZW results measured in the nasopharynx (NP) across 7 slice locations, where filled triangles denote inspiration, and open triangles denote expiration. Panel B shows the NP airway CSA for NZO mice where filled circles denote inspiration and open circles denote expiration. In each plot data errors bars show SEM and (*), indicates a significant difference between inspiration and expiration from post hoc comparisons (step-down Bonferroni, p < 0.05). Panel C (NZW mice) and Panel D (NZO mice) compare inspiratory and expiratory CSA in the NP + OP airway. Symbols and error annotations are the same in C and D as in A and B. In some cases the slice locations were intentionally offset for clarity. In each plot data errors bars show SEM and (*), indicates a significant difference between inspiration and expiration (step-down Bonferroni, post hoc comparisons, p < 0.05).

For the NP + OP airway, the respiratory-related change in cross-sectional area was also significantly different (as described below) within phenotype (p < 0.0001). Post hoc testing showed that airway area was greater during expiration than on inspiration in NZW mice at slice levels 2, 3, 4, and 5 (step-down Bonferroni, p < 0.05) and that airway area was greater on inspiration than during expiration in NZO mice at slice levels 4, 5 and 6 (step-down Bonferroni, p < 0.05).

In addition to comparisons of inspiratory/expiratory behavior within NZO and NZW mice described above, the measured cross-sectional airway area at each slice level during inspiration and expiration were compared for the NP and NP + OP airspace between mouse groups. These data comparing NZW and NZO mice are shown in Figure 6 (A-D) where cross-sectional area for inspiratory and expiratory phase are shown for the NP (panel A, B) and the NP + OP (panel C, D) airway. The ANOVA results for the NP airway revealed no significant differences overall in cross-sectional airway area between NZW and NZO mice (inspiration: p = 0.28; expiration p = 0.08). There was, however, a trend for caudal pharyngeal cross-sectional airway area (slice locations 5 and 6) to be larger in the NZW than NZO mice (raw p values < 0.015 with step-down Bonferroni correction, p <0.10). When the NP + OP airway was compared between NZW and NZO mice, there was also no significant difference between inspiratory (p = 0.14) and expiratory (p = 0.063) cross-sectional areas.

Figure 6.

(A-D): Mean cross-sectional area from Figure 4 is plotted to show comparisons between NZW and NZO mice. Panel A compares cross-sectional area (CSA) measured during inspiration in the nasopharynx (NP) across 7 slice locations between NZW (filled triangles) and NZO mice (filled circles). Panel B compared NZW (open triangles) to NZO (open circles) measured during expiration in the nasopharynx. Panel C compares NZW and NZO measured in nasopharynx plus oropharynx (NP + OP) during inspiration and Panel D shows NZW and NZO results in the NP + OP during expiration.

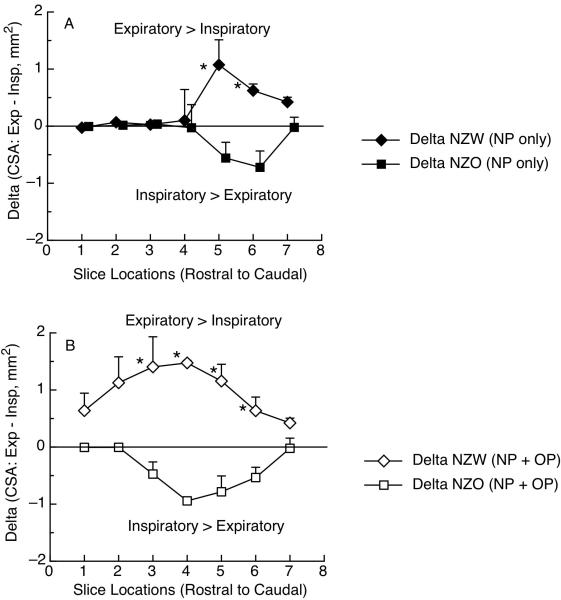

To further examine the changes in airway size between inspiration and expiration the value of Delta (defined in the Methods) is shown in Figure 7 (A, B). for the NP (Fig 7A) and NP + OP airway (Fig 7B). In the NP airway (Fig 7A) there was a significant overall effect such that Delta for NZW was greater than NZO (p < 0.0001). Post-hoc testing (Bonferroni) showed that Delta size was greater in NZW than NZO mice at slice levels 5 and 6 (p < 0.0001). Similarly, in the NP + OP airspace (Fig 7B), there was a significant overall effect such that Delta for NZW was greater than NZO (p < 0.0013). Post-hoc testing (step-down Bonferroni) showed that slice levels: 3, 4, 5 and 6 were significantly different (p< 0.05) indicating that change in airway size (magnitude or absolute value of Delta) was greater in NZW than NZO mice at those slice levels. Thus, inspiratory dilation occurred in NZO mice, while a significant reduction in airway size during inspiration was found in specific locations in the NZW mice.

Figure 7.

(A, B): A combined variable ‘Delta’ (expiratory cross-sectional area - inspiratory cross-sectional area) was plotted to show how the respiratory phasic pattern was different between NZW and NZO mice. Panel A shows Delta CSA for NZW (closed triangles) and NZO (closed circles) from the nasopharynx (NP) across 7 slice locations. Panel B shows Delta CSA measured from the nasopharynx plus oropharynx (NP + OP) where open triangle represent NZW points and open circles represent NZO points. Data are means with SEM and (*), for this figure indicates a significant difference between inspiration and expiration (step-down Bonferroni, post hoc comparisons, all p < 0.05)

4. Discussion

This study used respiratory-gated MR imaging to compare the dynamic changes in pharyngeal airway size during respiration in lean NZW and obese NZO mice. We found that pharyngeal cross-sectional area was greater during inspiration than expiration in obese NZO mice, but that airway area size was greater in expiration than inspiration in age-matched, normal weight NZW mice. This study also showed that changes although, opposite in direction (NZO was greater in inspiration but NZW was greater in expiration) in pharyngeal airway cross-sectional area during respiration were significant and occurred primarily in the more caudal region of the pharynx. Comparison of unadjusted airway sizes at comparable loci between NZW and NZO yielded no significant differences in inspiration although there was a trend towards NZW having larger expiratory cross-sectional area than NZO at two caudal pharyngeal locations. Overall we would not reject the null hypothesis (that there are no overall airway size reductions with obesity) since the trend in expiration would suggest that a larger number of animals might show a significant increase in NZW vs. NZO airway size. However, the difference in respiratory pattern of airway size changes would suggest that obesity does play a role in modulating airway size in this mouse model.

Regarding our imaging methods, the mice were imaged during spontaneous breathing in the supine position. The choice of this position helped avoid compromise of diaphragmatic function that would cause an anesthetized animal to have labored breathing and allowed the use of a pressure sensitive ‘pillow-transducer’ to monitor and record respiration. The pillow transducer is a non-invasive, easy to use method that provided a reliable trigger signal to initiate the respiratory-gated MRI (Brennick et al., 2009). Other methods that could monitor and record respiratory airflow or airway pressure could be used such as in a previous study in Zucker rats where we used an intra-pleural presssure transducer to monitor respiration (Brennick et al., 2006). While that method provided a precise recording of pleural pressure, that required an acute surgery whereby the animal was euthanized after the single MRI session. The pressure pillow is a non-invasive monitor method and allows the mice to be recovered from anesthesia only with the possiblilty of future studies.

Furthermore, we made certain that the head-to-neck angle was constant throughout the experiments since head extension and flexion can change pharyngeal airway size and mechanical properties (Bonora et al., 1985). In previous related work we measured head-to-neck angle and found we could replicate the same position in NZO and NZW mice with no significant differences between them (Brennick et al., 2009). The main reason to use respiratory-gated image acquisition was to allow imaging of dynamic changes between inspiration and expiration. Respiratory gating is the best method to prevent motion artifact (image blurring) while acquiring lines of image data that combine to make a fully resolved image. This method depends on the animal being in a steady state with a uniform pattern of body motion associated with each respiratory effort. Using this respiratory-gated technique, we were able to acquire high-resolution images without motion artifact.

The pattern of inspiratory pharyngeal airway dilation has been found in other mammals (Veasey et al., 1996; Brennick et al., 2006) but is not common in humans with or without obstructive sleep apnea (Schwab et al., 1993a; Schwab et al., 1993b). A study using CT imaging in 2 English bulldogs (Veasey et al., 1996) showed pharyngeal airway dimensions increased throughout inspiration and narrowed during expiration. Administration of a serotonergic antagonist reversed this pattern such that airway size was critically reduced during inspiration with some return to normal during expiration. While the pattern of inspiratory airway dilation in the upper airway of the English bulldog seems analogous to that of obese mice, a study from this lab (Brennick et al., 2006) reported that pharyngeal cross-sectional area was significantly greater in inspiration than expiration in both obese Zucker rats and their lean littermates. However, the pharyngeal airway in the obese rats was significantly smaller than that of the lean littermates in both inspiration and expiration.

Why do both lean and obese Zucker rats demonstrate a similar directional changes in pharyngeal cross-sectional area during respiration though different in magnitude, whereas NZW and NZO mice show respiratory patterns that are opposite each other? One reason for this incongruity with the effect of obesity may be that the obese and lean Zuckers are considered littermates (Farkas & Schlenker, 1994) with only one gene alteration (fa/fa) differentiating the two animals of same heritage. However, the NZO and NZW mice while having a similar parent strain are not ‘littermates’ per se and have genetic dissimilarity in more than one gene (Bielschowsky & Goodall, 1970).

It is not clear if the airway differences between obese NZO and lean NZW mice are due to anatomical or respiratory-related neuromuscular differences between the two mouse strains. Consistent with general knowledge of respiratory function (Bartlett Jr., 1986), relatively greater phasic inspiratory motor output to pharyngeal dilator muscles may be present in obese NZO than lean NZW mice. NZO mice are likely to generate a relatively large subatmospheric intrathoracic pressure during inspiration in order to overcome the mass loading of their chest wall by adipose tissue. Greater pharyngeal muscle activation might be required to protect airway patency when this large negative pressure is transmitted into the potentially collapsible pharyngeal airway. It is also possible that NZW mice do not “need” the same degree of pharyngeal muscle activation to maintain functional airway patency during inspiration. Therefore differences in neuromuscular activation of pharyngeal airway muscles that could cause differences in respiratory-related changes in pharyngeal airway size may explain why cross-sectional airway area during inspiration was similar between NZW and NZO strains of mice.

Active expiration is also a possible explanation for the differences in NP + OP among mice. A measure of pharyngeal pressure during expiration would provide some data to evaluate this along with EMG measurement of diaphragm or intercostal muscle activity during expiration as respiratory pump muscle activation during expiration can occur in some cases (Murray, 1986). It is also possible that there may be an effect of vagally mediated expiratory braking (at the glottis) that is different between the NZO and NZW strains as Song et al. (Song et al., 2009), found that there is laryngeal constriction that varies in mouse strains. If the lean NZW mice did not employ any expiratory braking a larger volume of air would be expelled during expiration and this might expand the NP + OP airspace. Conversely, if the NZO mice did employ expiratory braking then a smaller volume of air (compared to NZW) would be expelled and this might limit expiratory airway dilation. Reduced lung volume in the obese NZO mice might be the reason for such a hypothetical difference in expiratory braking and this might also be an explanation for the difference in expiratory pharyngeal airway size between NZW and NZO mice. This does not exclude the importance of increased soft tissues throughout the NZO upper airway that were quatitatively measured in our previous paper (Brennick et al., 2009).

Although, EMG activity might help to determine if the airway changes between the NZO and NZW mice were secondary to anatomy or neuromuscular function, EMG measurements at best could identify qualitatively whether there is inspiratory muscle activation. However, there are no general methods to calibrate EMG measurements between animals since there are many uncontrolled variables, e.g. electrode placement, etc. Additionally, due to the magnetic fields and RF interference, EMG recordings are difficult if not impossible to obtain during MRI experiments. Some studies include fMRI and EMG (van Rootselaar et al., 2008) but this is different than anatomically focused MRI. Thus, we do not have data in these MRI studies on the upper airway EMG activation during respiration.

Our data may help to explain the relationship of obesity to OSA since the current study demonstrates a difference in respiratory pattern between obese NZO and non-obese NZW mice. Pharyngeal dilation that occurs only in the NZO mouse during inspiration may be due to: increased inspiratory phasic activation, mechanoreceptor mediated reflex activation or an increase in background CO2 that might facilitate inspiratory neuromuscular activation to a greater degree than in the NZW mice. If pharyngeal neuromuscular activity during inspiration is increased in the NZO compared to the NZW mice then a sleep state loss of neuromuscular activity would presumably have a more negative consequence in obese mice than normal. Mezznotte et al. (Mezzanotte et al., 1992; Mezzanotte et al., 1996), has suggested that increased upper airway activity in OSA patients could become a liability and contribute to the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea since sleep-state related reduction of upper airway activity could be more detrimental to patients with a greater dependence of active dilation during wakefulness. Results of the current study would support a similar hypothesis that airway patency in obese animals is more dependent on active (inspiratory) dilation and thus obese animals would be more vulnerable to loss of neuromuscular pharyngeal activation.

One of the interesting findings of this study is that the greatest change in pharyngeal cross-sectional area between inspiration and expiration occurred in the mid to caudal regions in both mouse phenotypes. These data thus provide a quantitative regional examination of phasic respiratory airway size that compliments our previous findings in rats (Brennick et al., 2006) where we also found that both obese and lean Zucker rats had phasic respiratory related changes predominately in the mid and caudal pharyngeal regions. Interestingly, regional compliance measured in the passive isolated airway in rats is also greatest in the caudal region (Van Zutphen et al., 2007). Thus, in these rodent studies, the more caudal regions have both high compliance and larger phasic respiratory changes. This relationship would also imply that insufficient activation, leading to inspiratory narrowing would compromise airway size and have its affect on the most compliant regions.

How do the results of this study compare to airway size in the human respiratory cycle? Schwab et al. (Schwab et al., 1993b) described dynamic pharyngeal airway size fluctuation with respiration in awake normal and OSA patients and found that the pharyngeal airway changed size during respiration in a similar fashion between sleep disordered patients and normals but at each inspiratory or expiratory time phase there were differences between groups in the size and shape of the upper airway. They found in general, that positive expiratory pressure expanded the pharyngeal airway in both normal subjects and OSA patients and that the apneics expanded to a greater degree during early expiration. During inspiration neither apneics nor normals showed extensive narrowing but instead maintained their airway caliber, presumably due to upper airway muscle activation. Thus, the difference between apneics and normals was primarily related to size such that the apneic upper airway was significantly smaller than normals and this occurred primarily in the mid-pharyngeal and hypopharyngeal region (Schwab et al., 1993b). This area would be comparable to the mid and caudal regions in the mice and is also the location where significant differences in respiratory pattern between NZO and NZW were found (Fig. 7).

Considering the respiratory pattern however, awake patients with sleep disordered breathing tended to expand the pharyngeal airway to a greater degree during early expiration compared to normals and this is opposite to the behavior of the mice where the airway in the lean mice (NZW) were larger in expiration compared to that of the obese (NZO) mice (Schwab et al., 1993a). These results would lead to the speculation that inspiratory dilation as seen in obese mice, obese and lean Zucker rats and the English bulldog may be a compensatory mechanism that was not observed in patients in Schwab’s human study. However, in comparing the human and animal studies it should be noted that the animal studies were preformed under anesthesia while the human studies (Schwab et al., 1993a) were performed in unanesthetized, awake state.

4.1 Conclusion

In conclusion, we have studied a murine model of obesity and found that obese NZO mice tend to have a smaller airway at expiration than NZW, although inspiratory airway size in NZO was not significantly different than NZW mice. The major difference between the obese and non-obese mice was that obese mice have a pattern of inspiratory dilation such that the pharyngeal airway caliber in inspiration is larger than caliber in expiration. The respiratory pattern in NZW (normal) mice was the opposite of the NZO mice in that expiratory size in NZW was larger (in most regions) than inspiratory size. Finally, the findings show that respiratory size changes in both obese and normal nice are predominately in the mid and lower pharyngeal regions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge technical assistance from Kathy Zhang, M.S. and Sarika Shinde, B.S.. We also appreciate the technical support provided through the Small Animal Imaging Facility, Department of Radiology, and the Center for Sleep and Respiratory Neurobiology, Director, Allan Pack, MB, ChB, PhD at the University of Pennsylvania. Funding for this study was provided through NIH HL077838, HL077838-03S1, P01-HL094307 and HL66611.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Samuel T. Kuna, Associate Professor of Medicine Divisions of Sleep and Pulmonary and Critical Care, Department Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA and Chief, Pulmonary, Sleep and Critical Care, Department of Medicine, Philadelphia Veterans Administration Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA

Stephen Pickup, Director Small Animal Imaging Facility Department of Radiology, School of Medicine University of Pennsylvania.

Jacqueline Cater, Biomedical Statistical Consulting Center for Sleep and Respiratory Neurophysiology Department of Medicine, School of Medicine University of Pennsylvania.

Richard J. Schwab, Professor of Medicine Divisions of Sleep and Pulmonary and Critical Care, Department Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

References

- Bartlett D., Jr. Upper airway motor systems. In: Fishman AP, editor. The Respiratory System. 2nd edn American Physiology Society; Baltimore: 1986. pp. 223–246. [Google Scholar]

- Bielschowsky M, Goodall CM. Origin of inbred NZ mouse strains. Cancer Res. 1970;30:834–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonora M, Bartlett D, Jr., Knuth SL. Changes in upper airway muscle activity related to head position in awake cats. Respir Physiol. 1985;60:181–192. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(85)90102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennick MJ, Pack AI, Ko K, Kim E, Pickup S, Maislin G, Schwab RJ. Altered upper airway and soft tissue structures in the New Zealand obese mouse. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:158–169. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1435OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennick MJ, Pack AI, Pickup S, Schwab RJ. Cine-MRI shows airway inspiratory and expiratory compromise in New Zealand obese mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:A754. [Google Scholar]

- Brennick MJ, Pickup S, Cater JC, Kuna ST. Phasic respiratory pharyngeal mechanics by magnetic resonance imaging in lean and obese Zucker rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1031–1037. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-705OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas GA, Schlenker EH. Pulmonary ventilation and mechanics in morbidly obese Zucker rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:356–362. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.2.8049815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS@ System for Mixed Models. SAS Institute Inc; Cary: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzanotte WS, Tangel DJ, White DP. Waking genioglossal electromyogram in sleep apnea patients versus normal controls (a neuromuscular compensatory mechanism) J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1571–1579. doi: 10.1172/JCI115751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzanotte WS, Tangel DJ, White DP. Influence of sleep onset on upper airway muscle activity in apnea patients versus normal controls. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;156:1880–1887. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JF. The Normal Lung. W. B. Saunders Co.; Philadelphia: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano H, Magalang UJ, Lee S-d, Krasney JA, Farkas GA. Serotonergic modulation of ventilation and upper airway stability in obese Zucker rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1191–1197. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2004230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab RJ, Gefter WB, Hoffman EA, Gupta KB, Pack AI. Dynamic upper airway imaging during awake respiration in normal subjects and patients with sleep disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1993a;148:1385–1400. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab RJ, Gefter WB, Pack AI, Hoffman EA. Dynamic imaging of the upper airway during respiration in normal subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1993b;74:1504–1514. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z, Harris KA, Thach BT. Laryngeal constriction during hypoxic gasping and its role in improving autoresucitation in two mouse strains. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1223–1226. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91192.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rootselaar A, Maurits N, Renken R, Koelman J, Hoogduin J, Leenders K, Tijssen M. Simultaneous EMG-functional MRI recordings can directly relate hyperkinetic movements to brain activity. Human Brain Mapping. 2008;29:1430–1441. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zutphen C, Janssen P, Hassan M, Cabrera R, Bailey EF, Fregosi RF. Regional velopharyngeal compliance in the rat: influence of tongue muscle contraction. NMR In Biomedicine. 2007;20:682–691. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veasey SC, Panckeri KA, Hoffman EA, Pack AI, Hendricks JC. The effects of serotonin antagonists in an animal model of sleep disordered breathing. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1996;153:776–786. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer BJ, Brown DR, Michels KM. Statistical principles in experimental design. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.