Abstract

The purpose was to examine the associations between Morningness/Eveningness (M/E; a measure of sleep-wake preference) and alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use as well as the interaction of M/E and pubertal timing. The data represent baseline measures from a longitudinal study examining the association of psychological functioning and smoking with reproductive and bone health in 262 adolescent girls (11-17 years). The primary measures used for this study were pubertal timing (measured by age at menarche), the Morningness/Eveningness scale, and substance use (alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana). Multiple group path modeling showed that there was a significant interaction between pubertal timing and M/E on cigarette use. The direction of the parameter estimates indicated that for the early and on-time groups, Evening preference was associated with more cigarette use. For the late timing group the association was not significant. The results point to the need to consider sleep preference as a characteristic that may increase risk for substance use in adolescents.

Keywords: sleep preference, puberty, alcohol use, marijuana use, nicotine use

1. Introduction

Substance use is a substantial problem in adolescence. The latest findings from the Monitoring the Future study still show widespread substance use among adolescents in the United States. Twenty percent of 12th graders reported smoking in the past 30 days whereas 45% reported any lifetime use (Johnston et al., 2009). Marijuana use among high school students increased, with over 11% of 8th graders and 32% of 12 graders reporting use in the last year while 14% and 45% reported use at some time in their life. Although alcohol use among adolescents has decreased since its peak in the mid-1990’s, 32% of 8th graders and over 65% of 12th graders still report use in the last year (Johnston et al., 2009).

Early initiation of substance use in adolescence is a risk factor for later substance abuse and has been linked to other negative events such as motor vehicle accidents, drug abuse, unwanted pregnancies, depression, and suicide (Grant and Dawson, 1997; Grant, 1998; Grant and Dawson, 1998). In addition, substance use tends to be associated with psychopathology. Individuals who use substances report higher rates of disruptive behavior disorders, depressive symptoms, and externalizing problems (Fergusson et al., 2007; Lansford et al., 2008).

Substance use can be affected by a number of factors. One factor that may increase the risk is the adolescent’s sleep/wake preference. Sleep preference (Morningness versus Eveningness) is based on chronobiology and circadian rhythms (Tankova et al., 1994; Young and Kay, 2001). Individual differences in sleep preference are often viewed on a continuum with the extremes of the scale being referred to as Morning or Evening type. Morning types awaken early, are refreshed upon awakening, and go to bed early, whereas Evening types have difficulty rising in the morning, are tired when awakening, and stay up late. Morning types prefer doing mental and physical activity in the morning, whereas evening types prefer these activities later in the day (Goldstein et al., 2007). Evening types have irregular sleep-wake schedules; they go to bed later, wake up later, sleep more on weekends than on school nights, and complain of sleep debt compared to Morning types (Giannotti et al., 2002). Younger children tend to be Morning types, although as they enter adolescence, particularly puberty (Randler, 2008b; Tonetti et al., 2008), the preference shifts to Evening type; they begin going to sleep later and will stay asleep later when permitted (Wolfson and Carskadon, 1998; Cavallera and Giudici, 2008). Eveningness has been found to affect various areas of functioning. Evening types have more attention problems, emotional problems, and depressive symptoms as well as lower self-control and poorer school achievement than Morning types (Giannotti et al., 2002; Digdon and Howell, 2008; Gaspar-Barba et al., 2009; Pabst et al., 2009). Eveningness is also associated with health problems such as menstrual symptoms, asthma, and migraines (Bruni et al., 2008; Ferraz et al., 2008; Negriff and Dorn, 2009).

In addition to the various other problematic behaviors evidenced by Evening types, an Evening preference may also increase the risk of substance use. Previous research has found that Eveningness is related to antisocial behavior in both pre- and early pubertal adolescents (Susman et al., 2007). Adolescents with Evening preference may stay out later, attend late night parties, or need substances such as nicotine or caffeine to counteract the effects of erratic sleep patterns. Evidence showed that individuals with Evening preference consume more alcohol and nicotine than Morning types (Adan, 1994; Wittmann et al., 2006; Randler, 2008a) and these associations appear to be stronger in adolescents than adults (Wittmann et al., 2006). Other studies showed that Evening type adolescents tend to use alcohol and nicotine more frequently than Morning types (Giannotti et al., 2002) and to use more habitually (Gau et al., 2007).

Pubertal timing is another factor found to affect the initiation and prolonged use of substances. In particular, there is a strong association between early pubertal timing and early use of cigarettes and alcohol for both males and females (Ge et al., 2006b; Bratberg et al., 2007; Westling et al., 2008; Downing and Bellis, 2009). In one study early developing females were 3.7 times more likely to have tried cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana than non-early maturers (Lanza and Collins, 2002), whereas another showed that girls with early puberty reported smoking their first cigarette about 7 months earlier than girls with later puberty (Wilson et al., 1994). Similarly, early maturers were found to use alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana with more regularity and frequency than non-early maturers (Tschann et al., 1994). Early maturing girls also initiated alcohol use at a younger age than later maturing girls (Deardorff et al., 2005), and early maturation was related to more alcohol use (Wichstrom, 2001).

Overall, there is substantial evidence that early pubertal timing puts an adolescent at increased risk for substance use. However, one study found late timing to be associated with more alcohol use in a sample of 11-17 year old girls (Marklein et al., 2009). Still others report a pubertal timing effect on substance use when moderators such as parenting, peer substance use, or school and neighborhood context were considered (Foshee et al., 2007). Moderators provide useful information about conditions that may amplify or alleviate the risks associated with early puberty. Identifying the early roots of substance use with regard to the risk factors of sleep preference and timing of puberty may inform early substance use prevention. In particular, early timing may increase the risk of substance use for adolescents with Evening preference, more so than early maturers with Morning preference. For Evening-types, a proclivity for late night activities may provide more exposure and opportunity for substance use. In addition, being an early maturer may increase the risk for substance use because early pubertal timing is linked to more exposure to older peers and deviant peers who may be engaging in substance use (Stattin and Magnusson, 1990; Haynie, 2003; Lynne et al., 2007).

There is substantial evidence that both early pubertal timing and Evening preference are individually associated with substance use. However, the studies showing an association between Eveningness and substance use have all been conducted on samples outside of the United States and no studies have examined the interaction effect between Morningness/Eveningness and pubertal timing on substance use. Therefore, the aims of this study were a) to examine the associations between Morningness/Eveningness and alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use and b) to examine the interaction between pubertal timing and sleep preference on substance use in adolescent girls. It was hypothesized that Eveningness would be associated with greater use of all three substances, and that girls with Evening preference and early pubertal timing would show higher substance use than on-time or late maturing girls.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants included adolescent girls (N = 262) enrolled in an ongoing longitudinal study on smoking, mood, and their potential effects on bone and reproductive health (Dorn et al., 2008). Data for the present study were from the first assessment which took place from December 2003 to October 2007. Girls were primarily Caucasian (62.8%) or African American (32.8%). The remaining 5.3% of the girls represented mixed-race or other race/ethnicities and were combined with the African American group. Participants were recruited from an urban teen health clinic and the surrounding community. Enrollment was by age cohorts of 11, 13, 15, and 17 years old as well as an eligibility questionnaire based on five previously defined levels of smoking experience ranging from “not even a puff” to daily smoking. Exclusion criteria were based on factors relevant to the ongoing study and included: 1) pregnancy or breast feeding within 6 months, 2) primary amenorrhea ( >16 years) or secondary amenorrhea (< 6 cycles/year), 3) body mass index < the 1st percentile or body weight > 300 pounds, 4) medication/medical disorder influencing bone health, and 5) psychological disabilities impairing comprehension or compliance. This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the affiliated hospital. Parents provided consent and the adolescent provided assent.

2.2. Procedures

Participants came to an urban children’s hospital for their study visits. A physical examination was conducted by a physician or nurse practitioner trained in the procedures. During that time, a standardized interview was also conducted focusing on menstrual history followed by administration of the Morningness/Eveningness questionnaire. Other measures included in the visit were not the focus of this study. Administration of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) (Shaffer et al., 2000) followed, which assessed substance use.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Pubertal timing

Age at menarche (years, months) was obtained through clinician interview. Early, on-time, and late timing groups were created based on the sample distribution within Caucasian and non-Caucasian racial groups in this study. Plus and minus one standard deviation (SD) from the mean are typically used as cut-offs for the timing groups (Ge et al., 2006a). Girls who were 1 SD or more below the mean (within their racial group) were coded as early-timing, and those that were 1 SD or more above the mean were coded as late-timing; all remaining girls were coded as on-time. For the Caucasian group the cut-offs for the early and late groups were 11.52 and 13.74 years respectively, whereas for the non-Caucasian group the cut-offs were 10.67 and 13.34 years respectively.

At Time 1, 209 (80%) of the sample were menarcheal. For the remaining 53 premenarcheal girls, age at menarche was obtained from a subsequent data collection time point. Six premenarcheal girls withdrew before the Year 2 visit and thus could not be assigned to a timing group. At Year 4, three premenarcheal girls remained. Based on their chronological age and our stated criterion, they were placed in the late timing group.

2.3.2. Morningness/Eveningness

Morningness/Eveningness (M/E) was assessed via the Morningness/Eveningness scale for children (Carskadon et al., 1993). Ten questions assessed preferred time of day for activities (e.g. waking time, bedtime, test taking). The scale ranged from 10- 42 with lower scores indicating Evening preference. In this sample the scores ranged from 13-38 with acceptable internal consistency reliability (α = 0.78).

2.3.3. Substance Use

Substance use (past year) was measured by questions from the alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana modules of the DISC (Shaffer et al., 2000). Research coordinators trained in the administration of the DISC completed the computer interview with the adolescents. Responses (never tried, experimentation, and use) were defined based on items from the alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana modules as modeled by others (Pajer et al., 2007).

Adolescent alcohol use was coded as: 0 = never tried alcohol in their lifetime excluding a sip, 1 = experimented with alcohol in the past year (more than one but less than six drinks), or 2 = consumed alcohol in the past year (six or more drinks).

Adolescent cigarette use was coded as: 0 = never smoked cigarettes in their lifetime, 1 = experimented with cigarettes in the past year (at least a puff, but not more than once a week for a month or longer), or 2 = regular smokers in the past year (smoked at least once a week for a month or longer).

Adolescent marijuana use was as: 0 = never used marijuana in their lifetime, 1 = experimented with marijuana in the past year (more than one but less than six times), or 2 = smoked marijuana in the past year (six or more times).

2.3.4 Covariates

The covariates included in the data analyses were age, race, and socioeconomic status (SES). The Hollingshead scale was used as an index of SES with higher scores indicating higher SES (Hollingshead, 1976). Parents reported on questions regarding SES. In the current sample the mean SES score was 35.90 (blue collar/working class) with a range of 14-66 (possible range=13-66).

2.4. Data Analysis

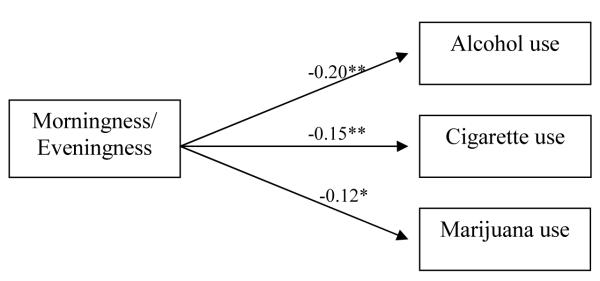

Descriptive statistics were examined and mean differences between the pubertal timing groups on M/E were tested with analysis of variance (ANOVA). Path modeling using Amos 7.0 (Arbuckle, 2006) and the asymptotically distribution-free estimation method was used to test the study hypotheses. First, to examine the associations between M/E and substance use for the total sample, M/E was modeled as the independent variable with alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use as the three dependent variables (Figure 1). Main effects were included between M/E and each substance use variable. The covariates were age, race (Caucasian/non-Caucasian), and socioeconomic status (Hollingshead, 1976). Second, to examine the interaction effect between M/E and pubertal timing on substance use, the previous model was simultaneously fit to all three pubertal timing groups using multiple group path modeling. First an unrestricted model was fit simultaneously to all groups then the parameter estimate to each substance use variable, in turn, was restricted to be equal across groups. A significant decrement in model fit as indicated by the chi-square difference test demonstrated whether the restricted parameter was significantly different between the groups, signifying an interaction effect.

Figure 1.

Path diagram testing the relationship between Morningness/Eveningness and substance use for the total sample. Standardized path coefficients are shown. Covariates (age, race, SES) were omitted from the figure for simplicity. Lower scores on M/E indicate Evening preference. **p<0.01, *p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics can be found in Table 1. Mean differences in M/E between the pubertal timing groups were tested and no significant differences were found (F (2, 256) = 1.04, p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for study variables

| N | Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 262 | 14.93 | 2.17 | 11.07 - 17.99 |

| SES | 261 | 37.32 | 13.67 | 14 - 66 |

| Age at menarche (years) | 252 | 12.39 | 1.24 | 7.42 - 16.08 |

| Morningness/Eveningness | 260 | 26.41 | 5.14 | 12 - 38 |

|

| ||||

| * | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

|

|

||||

| Alcohol use: n | 135 (51.5%) | 59 (22.5%) | 67 (25.6%) | |

| Cigarette use: n | 147 (56.1%) | 38 (14.5%) | 76 (29%) | |

| Marijuana use: n | 182 (69.5%) | 31 (11.8%) | 48 (18.3%) | |

Note: for alcohol and marijuana 0 = no use, 1 = used 1-5 times, 2 = used ≥ 6 times; for cigarettes 0 = no use, 1 = smoked less than once a week, 2 = smoked at least once a week for a month or longer; alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; SES = socioeconomic status; Morningness/Eveningness-lower scores indicate Evening preference

3.2. Morningness/Eveningness and Substance Use: Total Sample

The first aim was to examine the associations between M/E and alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use for the total sample. The path model was fully saturated producing a perfect fit to the data. There were significant associations between M/E and all three types of substance use. (See Figure 1 and Table 2). The direction of all path coefficients indicated that Evening preference was associated with more substance use.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates for Morning/Eveningness and substance use from multiple group path modeling analyses between pubertal timing groups

| Morningness/Eveningness (M/E) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early |

On-time |

Late |

Total sample |

||||

| Unstandard ized coefficient (SE) |

Standardi zed coefficien t |

Unstandard ized coefficient (SE) |

Standardi zed coefficien t |

Unstandard ized coefficient (SE) |

Standardi zed coefficien t |

Standardi zed coefficien t |

|

| Alcohol | −0.05 (.02) | −0.32* | −0.03 (.01) | −0.20** | −0.02 (.02) | −0.12 | −0.20** |

| Cigarettes | −0.06 (.02) | −0.33**a | 0-.03 (.01) | −0.16*b | 0.01 (.02) | 0.06a,b | −0.15** |

| Marijuana | −0.04 (.02) | −0.30* | −0.02 (.01) | −0.11 | −0.02 (.02) | −0.09 | −0.12* |

Note: SE= Standard Error; Lower scores on M/E indicate Evening preference; coefficients with

superscript are significantly different

at p < 0.01, those with

superscript are significantly different at p < 0.08;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

3.3. Interaction Effect of Morningness/Eveningness and Pubertal timing on Substance Use

The second aim examined the interaction between M/E and pubertal timing on substance use. The model fit was good for the unrestricted model (χ2 =19.34 (12); RMSEA=0.05; CFI=0.99). There was a marginally significant decrement in model fit when the path from M/E to cigarette use was constrained to be equal across groups (Δχ2 = 5.59 (2), p =0.06) indicating an interaction effect between M/E and pubertal timing. The critical ratios of differences test indicated that the parameter between M/E and cigarette use was significantly different for the early versus late groups (CR=2.47, p=0.01), a trend for the on-time and late groups (CR=1.79, p=0.07), and not different between the early and on-time group. For the early and on-time groups there was a significant relationship between M/E and cigarette use (early: β= −0.33, p <0.01; on-time: β= −0.16, p<0.05) whereas for the late group the association was not significant (β= 0.06, p=0.54). This indicates that for the early group a five point (1 SD) shift toward Eveningness was associated with a 30% increase in the risk for moving towards a higher substance use category. In the on-time group a five point (1 SD) shift toward Eveningness was associated with a 15% increase in risk for a higher substance use category. There were no other significant moderating effects of pubertal timing group. (See Table 2).

4. Discussion

This study examined the associations between Morningness/Eveningness and alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use in adolescent girls and the interaction between Morningness/Eveningness and pubertal timing on substance use. As hypothesized, the results showed that for the total sample Evening preference was associated with higher use of all three substances. In addition, for early and on-time maturers, Eveningness was associated with more cigarette use than for late maturers. However, there were no significant differences in the association between M/E and alcohol or marijuana use by pubertal timing group.

4.1. Eveningness and Substance use

Greater substance use by Evening types may be a result of a combination of factors. Late-to-bed youth tend to have less parental supervision (Gau and Soong, 2003; Cousins et al., 2007), which combined with their inclination to stay up later and possible selection of substance using peers (Donovan and Jessor, 1985) may increase their risk for substance use (Stattin and Kerr, 1999). Alternatively, adolescents may adopt Eveningness patterns in order to pursue interests that are more supported by a late night lifestyle (Stattin and Kerr, 1999). Lastly, mood problems such as depressive symptoms are associated with Evening preference (Gau et al., 2007; Pabst et al., 2009) and comorbidity of depression and substance use has often been found (Armstrong and Costello, 2002; Volkow, 2004).

Overall, during puberty the architecture of sleep changes dramatically: there is a decrease in the amount of REM sleep, greater daytime sleepiness, and a shift toward phase delay (later bedtime and later awakening) (Carskadon et al., 1993; Dahl and Lewin, 2002). Although the present study did not examine sleep or sleep problems in particular, the findings of other studies suggest that sleep problems in general increase vulnerability to substance use (Johnson and Breslau, 2001; Wong et al., 2004). Other studies have found that in adults, Evening types scored higher on several measures of propensity towards risk-taking (Killgore, 2007) whereas in adolescents sleep habits resulting in insufficient sleep were associated with more risk taking behaviors including alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use (O’Brien and Mindell, 2005). The evidence demonstrates that there may be a number of aspects of sleep (i.e. insufficient sleep or Evening preference) that increase the risk for substance use. Although studies show sleep problems are associated with more substance use (Johnson and Breslau, 2001; Wong et al., 2004; O’Brien and Mindell, 2005), this is the first study to show that the Evening sleep chronotype is associated with substance use in an U.S. sample of adolescent girls. Studies conducted in countries outside the U.S may be characterized by cultural differences in the acceptability of the use of certain substances. Generalizing previous findings to American adolescents may not be appropriate. However, the results from this study concur with those conducted in other countries (Adan, 1994; Giannotti et al., 2002; Gau et al., 2007; Randler, 2008a) showing that Eveningness is associated with more alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use.

4.2. Eveningness, Early Pubertal Timing, and Substance Use

Overall the literature shows that separately early pubertal timing and Evening preference are associated with more substance use (Adan, 1994; Tschann et al., 1994; Wichstrom, 2001; Lanza and Collins, 2002; Gau et al., 2007), however no studies have examined the interaction effect between the two on substance use. Similar to Susman and colleagues (2007) we found no pubertal timing differences in sleep preference, however we did find that the interaction between pubertal timing and sleep preference influences cigarette use. As expected, our results show that the association between Eveningness and cigarette use was stronger for the early and on-time pubertal timing groups than for the late group, with the late group showing a non-significant association. This demonstrates that being a late maturer is relatively protective. A similar pattern was found for alcohol and marijuana use, although the parameter estimates between pubertal timing groups were not significantly different. There is evidence that even infrequent experimentation with cigarettes in adolescence increases the likelihood of becoming a regular smoker in young adulthood (Chassin et al., 1990; Choi et al., 1997). Therefore identifying the risks for cigarette use in adolescence may help intervene in the development of long-term use. Early pubertal timing is thought to increase substance use because early maturers may have more opportunities to be exposed to and participate in substance use. A similar explanation may apply for Eveningness and substance use. An early maturer with Evening preference may be more vulnerable than an on-time or late maturer with Evening preference because the early maturer may be drawn into older peer groups or deviant peer groups due to their mature physical appearance (Stattin and Magnusson, 1990; Caspi et al., 1993; Lynne et al., 2007). This may expose them to substance-using peers while they lack the cognitive and emotional maturity to deal with peer pressure. A strength of the current study was the examination of a widely understudied influence on adolescent substance use, namely Morningness/Eveningness. These results contribute to the understanding of sleep preference changes in adolescence as well as potential risk factors for substance use.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First the data were cross-sectional precluding any causal inferences. Therefore we cannot determine if Evening preference leads to increased substance use or if substance use alters sleep chronotype. Longitudinal data will allow examination of the associations between pubertal timing, sleep preference, and substance use as they change with advancing age. Specifically it will be important to examine whether Eveningness precedes substance use or if substance use alters sleep preference. Of particular concern is the increased risk for substance abuse linked to early initiation and the persistence of substance use into adulthood. Second, all measures were self-report which may introduce bias. However for the concepts considered herein (i.e. sleep preference, age at menarche, substance use) the adolescents’ self-report is likely the most accurate. In addition, measures of self report M/E have been validated against temperature, hormonal profiles, actigraphy, and sleep logs (Kerkhof, 1985; Bailey and Heitkemper, 1991; Gibertini et al., 1999; Baehr et al., 2000; Tonetti, 2007) indicating that self report of this construct is accurate. We also did not examine possible psychiatric comorbidity with substance use. As depression and substance use are correlated in many studies and are linked to both Eveningness and early pubertal timing, there is likely more complexity to these associations than can be gleaned from the current findings. In addition many other variables have been linked to substance use and we could not include all the possible risk factors for substance use.

An additional limitation may be the sample size for this study. Due to the nature of the pubertal timing variable there will inherently be more participants in the on-time group than in the early or late groups. However, many studies have used this variable with similar distributions and sample sizes to the current study, thus our confidence in this variable is supported. Additionally, because this was a secondary data analysis we may have limited statistical power, particularly in examining interaction terms. The non-significant interaction effects for marijuana and alcohol use may be due to difficulties in detecting interaction effects with unequal cell sizes and creating categorical variables from continuous ones (Aguinis et al., 2001; Frazier et al., 2004). Lastly, it should be noted that our sample was drawn from a limited geographic region in the Midwestern United States, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings as this sample may not be representative of all adolescents in the US.

Future research should examine these variables to gain a clearer understanding of the multifaceted etiology of substance use. While we did not examine racial differences per se, we did control for race in the analyses. Supplementary analyses between racial groups did not show any racial differences in the association between M/E and substance use. Lastly, we cannot determine whether Evening preference leads to increased substance use due to social or environmental factors or if they are linked by a familial predisposition for substance use that may become exacerbated in Evening types. The results of this study illustrate two conditions (M/E and pubertal timing) that may amplify the risk for substance use in adolescents. Examination of other factors such as peer group influences, neighborhood characteristics and parental monitoring will clarify contextual processes that may further increase substance use.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Grant Number R01 DA 16402, National Institute of Drug Abuse, NIH. PI: Lorah D. Dorn, Ph.D., U.S.P.H.S. Grant Number UL1RR026314 from the National Center for Research Resources, NIH, and by National Research Service Award Training Grant 1T32PE10027.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adan A. Chronotype and personality factors in the daily consumption of alcohol and psychostimulants. Addiction. 1994;89:455–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis H, Boik RJ, Pierce CA. A generalized solution for approximating the power to detect effects of categorical moderator variables using multiple regression. Organizational Research Methods. 2001;4:291–323. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 7.0 [Computer software] Amos Development Corporation; Spring House, PA: 2006. p. Computer software. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1224–1239. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baehr EK, Revelle W, Eastman CI. Individual differences in the phase and amplitude of the human circadian temperature rhythm: with an emphasis on morningness-eveningness. Journal of Sleep Research. 2000;9:117–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SL, Heitkemper MM. Morningness-eveningness and early-morning salivary cortisol levels. Biological Psychology. 1991;32:181–192. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(91)90009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratberg GH, Nilsen TI, Holmen TL, Vatten LJ. Perceived pubertal timing, pubertal status and the prevalence of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking in early and late adolescence: a population based study of 8950 Norwegian boys and girls. Acta Paediatrica. 2007;96:292–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni O, Russo PM, Ferri R, Novelli L, Galli V. Relationships between headache and sleep in a non-clinical population of children and adolescents. Sleep Medicine. 2008;9:542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carskadon MA, Vieira C, Acebo C. Association between puberty and delayed phase preference. Sleep: Journal of Sleep Research & Sleep Medicine. 1993;16:258–262. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Lynam D, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Unraveling girls’ delinquency: biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallera GM, Giudici S. Morningness and eveningness personality: A survey in literature from 1995 up till 2006. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Edwards DA. The natural history of cigarette smoking: Predicting young-adult smoking outcomes from adolescent smoking patterns. Health Psychology. 1990;9:701–716. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Pierce JP, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Berry CC. Which adolescent experimenters progress to established smoking in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1997;13:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins JC, Bootzin RR, Stevens SJ, Ruiz BS, Haynes PL. Parental involvement, psychological distress, and sleep: a preliminary examination in sleep-disturbed adolescents with a history of substance abuse. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:104–113. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE, Lewin DS. Pathways to adolescent health sleep regulation and behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Gonzales NA, Christopher FS, Roosa MW, Millsap RE. Early puberty and adolescent pregnancy: the influence of alcohol use. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1451–1456. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digdon NL, Howell AJ. College students who have an eveningness preference report lower self-control and greater procrastination. Chronobiology International. 2008;25:1029–1046. doi: 10.1080/07420520802553671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Jessor R. Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:890–904. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn LD, Susman EJ, Pabst S, Huang B, Kalkwarf H, Grimes S. Association of depressive symptoms and anxiety with bone mass and density in ever-smoking and never smoking adolescent girls. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162(12):1181–1188. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.12.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing J, Bellis MA. Early pubertal onset and its relationship with sexual risk taking, substance use and antisocial behaviour: a preliminary cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:446. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse and dependence: Results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:S14–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraz E, Borges MC, Vianna EO. Influence of nocturnal asthma on chronotype. Journal of Asthma. 2008;45:911–915. doi: 10.1080/02770900802395470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Granger DA, Benefield T, Suchindran C, Hussong AM, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, DuRant RH. A Test of Biosocial Models of Adolescent Cigarette and Alcohol Involvement. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27:4–39. doi: 10.1177/0272431606294830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar-Barba E, Calati R, Cruz-Fuentes CS, Ontiveros-Uribe MP, Natale V, De Ronchi D, Serretti A. Depressive symptomotology is influenced by chronotypes. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;119:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SS, Shang CY, Merikangas KR, Chiu YN, Soong WT, Cheng ATA. Association between morningness-eveningness and behavioral/emotional problems among adolescents. Journal of Biological Rhythms. 2007;22:268–274. doi: 10.1177/0748730406298447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SS, Soong WT. The transition of sleep-wake patterns in early adolescence. Sleep: Journal of Sleep and Sleep Disorders Research. 2003;26:449–454. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Brody GH, Conger RD, Simons RL. Pubertal maturation and African American children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006a;35:531–540. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Jin R, Natsuaki MN, Gibbons FX, Brody GH, Cutrona CE, Simons RL. Pubertal Maturation and Early Substance Use Risks Among African American Children. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006b;20:404–414. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Sebastiani T, Ottaviano S. Circadian preference, sleep and daytime behaviour in adolescence. Journal of Sleep Research. 2002;11:191–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibertini M, Graham C, Cook MR. Self-report of circadian type reflects the phase of the melatonin rhythm. Biological Psychology. 1999;50:19–33. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(98)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein D, Hahn CS, Hasher L, Wiprzycka UJ, Zelazo PD. Time of day, Intellectual Performance, and Behavioral Problems in Morning Versus Evening type Adolescents: Is there a Synchrony Effect? Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF. Age at smoking onset and its association with alcohol consumption and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1998;10:59–73. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National longitudinal alcohol epidemiologic survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1998;10:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL. Context’s of risk? Explaining the link between girls’ pubertal development and their delinquent involvement. Social Forces. 2003;82:355–397. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AF. Four Factor Index of Social Status: Manual. Department of Sociology, Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EO, Breslau N. Sleep problems and substance use in adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;64:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2008. Volume 1: Secondary school students. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhof GA. Inter-individual differences in the human circadian system: a review. Biological Psychology. 1985;20:83–112. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(85)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WD. Effects of sleep deprivation and morningness-eveningness traits on risk-taking. Psychological Reports. 2007;100:613–626. doi: 10.2466/pr0.100.2.613-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Erath S, Yu T, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. The developmental course of illicit substance use from age 12 to 22: Links with depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders at age 18. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:877–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Collins LM. Pubertal timing and the onset of substance use in females during early adolescence. Prevention Science. 2002;3:69–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1014675410947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynne SD, Graber JA, Nichols TR, Brooks-Gunn J, Botvin GJ. Links between pubertal timing, peer influences, and externalizing behaviors among urban students followed through middle school. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:181.e187–181.e113. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklein E, Negriff S, Dorn LD. Pubertal timing, friend smoking, and substance use in adolescent girls. Prevention Science. 2009;10:141–150. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0120-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, Dorn LD. Morningness-Eveningness and menstrual symptoms in adolescent girls. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;67:169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien EM, Mindell JA. Sleep and risk-taking behavior in adolescents. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2005;3:113–133. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0303_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabst SR, Negriff S, Huang B, Susman EJ, Dorn LD. Depression and anxiety in adolescent females: The impact of sleep preference and body mass index. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44:554–560. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajer K, Kazmi A, Gardner W, Wang Y. Female Conduct Disorder: Health Status in Young Adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:84.e81–84.e87. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randler C. Differences between smokers and nonsmokers in Morningness-Eveningness. Social Behavior and Personality. 2008a;36:673–680. [Google Scholar]

- Randler C. Differences in sleep and circadian preference between Eastern and Western German adolescents. Chronobiology International. 2008b;25:565–575. doi: 10.1080/07420520802257794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Future directions and challenges in the study of morningness-eveningness. Human Development. 1999;42:199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Magnusson D. Paths through life-Vol. 2: Pubertal maturation in female development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Susman EJ, Dockray S, Schiefelbein VL, Herwehe S, Heaton JA, Dorn LD. Morningness/eveningness, morning-to-afternoon cortisol ratio, and antisocial behavior problems during puberty. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:811–822. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tankova I, Adan A, Buela-Casal G. Circadian typology and individual differences: A review. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;16:671–684. [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti L. Validity of the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire for Adolescents (MEQ-A) Sleep and Hypnosis. 2007;9:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti L, Fabbri M, Natale V. Sex difference in sleep-time preference and sleep need: a cross-sectional survey among Italian pre-adolescents, adolescents, and adults. Chronobiology International. 2008;25:745–759. doi: 10.1080/07420520802394191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Adler NE, Irwin CE, Millstein SG, Turner RA, Kegeles SM. Initiation of substance use in early adolescence: The roles of pubertal timing and emotional distress. Health Psychology. 1994;13:326–333. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND. The reality of comorbidity: depression and drug abuse. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56:714–717. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westling E, Andrews JA, Hampson SE, Peterson M. Pubertal timing and substance use: The effects of gender, parental monitoring and deviant peers. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichstrom L. The impact of pubertal timing on adolescents’ alcohol use. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DM, Killen JD, Hayward C, Robinson TN, Hammer LD, Kraemer HC, Varady A, Taylor CB. Timing and rate of sexual maturation and the onset of cigarette and alcohol use among teenage girls. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1994;148:789–795. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170080019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Dinich J, Merrow M, Roenneberg T. Social jetlag: Misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiology International. 2006;23:497–509. doi: 10.1080/07420520500545979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Development. 1998;69:875–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Sleep problems in early childhood and early onset of alcohol and other drug use in adolescence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:578–587. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000121651.75952.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MW, Kay SA. Time zones: A comparative genetics of circadian clocks. National Review of Genetics. 2001;2:702–715. doi: 10.1038/35088576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]