Since its introduction approximately 20 years ago, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has rapidly become the treatment of choice for symptomatic cholelithiasis [1–3]. Conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy generally is performed through four small incisions in the abdominal wall [4]. In recent years, a less invasive method has been sought in an effort to reduce postoperative pain and morbidities such as wound infection and trocar-site hernias while further enhancing the cosmetic results. Initial attempts to perform the procedure through three and then two ports or with reduced-diameter trocars (needlescopic surgery) [5–9] have since been superseded by even less invasive and more innovative techniques, namely, single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) [10–13].

Single-incision laparoscopic surgery is an attractive technique for cholecystectomy due to its superior cosmetic results and potential to reduce the rate of wound complications such as infection, hematoma, and hernia. This technique, however, is not straightforward. The technical complexity of SILS naturally results in a steep learning curve and increased operating room time and requires specialized equipment.

The primary technical obstacles of SILS currently include

Collision of instruments both within and outside the abdomen as a result of their common entry point (“sword fighting”)

Inadequate triangulation

Compromised field of view due to obstruction by instruments entering the common port

Inadequate exposure and retraction.

Several techniques have since evolved to overcome these potential pitfalls [14–16]. By incorporating a number of these techniques, we have created a simplified technique that has proved successful with both animal and human subjects. We describe both our experience and what we have learned, which have allowed simplification of a technical complex procedure.

Methods

The single-incision approach was used for 31 patients (28 women and 3 men). The indications for surgery included recurrent biliary colic in 24 patients, acute cholecystitis in 5 patients, gallstone pancreatitis in 1 patient, and postcholedocholithiasis treated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in 1 patient. The mean patient age was 39.2 years (range, 19–65 years), and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 26 kg/m2 (range, 19.2–36.1 kg/m2). Nine of the patients (29%) had undergone previous lower abdominal surgery, appendectomy, or cesarean section.

In an effort to overcome the problem of “sword fighting,” instruments were introduced into the peritoneal cavity through either a single 15-mm dual-seal trocar or three 5-mm low-profile trocars (Storz endoscopy, Tuttlingen, Germany) (Fig. 1). A flexible endoscope, used in four of the operations, was introduced to the abdominal cavity through the 10-mm seal in the 15-mm dual-seal trocar. In the remaining 27 cases, we used a 5-mm 30º laparoscope and switched its insertion point during the procedure as needed.

Fig. 1.

5 mm low profile trocars (Storz endoscopy) inserted through a single 18 mm skin incision. The use of these trocars enables minimal instruments’ collision and better maneuverability

Local triangulation was achieved using articulating instruments (Novare Surgical, Cupertino, CA, USA) (Fig. 2). Retraction was accomplished using one of two techniques. The first technique, applied in nine operations, used an endoloop to grasp the gallbladder dome and then used a suture passer to retract the endoloop through the abdominal wall. The second technique, applied in 20 operations, used endo-retractors (Virtual Ports Ltd., Misgav, Israel) (Fig. 3).

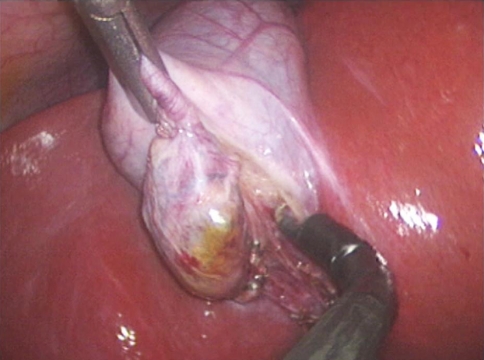

Fig. 2.

RealHand (TM) hook (Novare surgical) dissecting off the gallbladder from the liver bed. The use of articulating instruments enables local triangulation, enhances dissection capability and improves the view

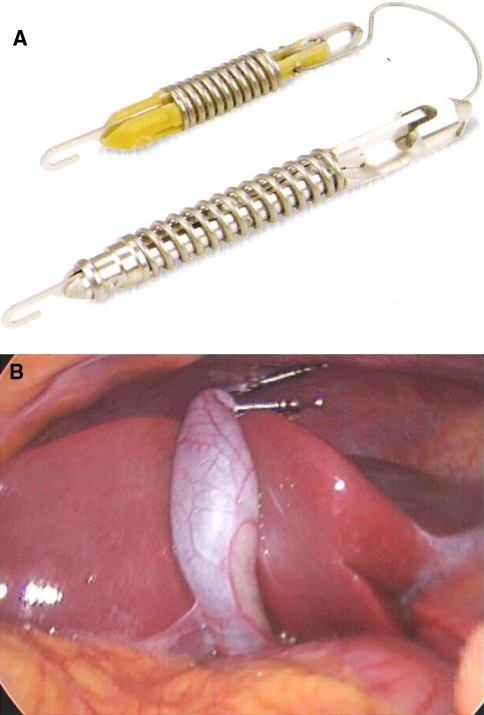

Fig. 3.

A Virtual Ports Endograb (TM). The use of endo-retractors optimizes retraction and exposure capability including changing retraction angles during the operation. B Virtual Ports Endograb (TM). The retraction of the gallbladder achieved with the device is shown

The endo-retractor contains two grasping forceps. The first is attached to the gallbladder, and the second is anchored anywhere on the peritoneal surface. Hence, retraction is versatile, and retracting direction can be changed during the procedure as needed.

In two operations, no retraction device was used. The steps of the procedure were exactly the same as in standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

The operative time, postoperative hospital length of stay, and complications were recorded. Postoperative pain levels were established using the visual analog scale (VAS) on postoperative day 1, and on the first outpatient follow-up visits occurred on postoperative days 7 to 10. At that time, the patients also were questioned regarding their return to usual daily activities and their general satisfaction.

Results

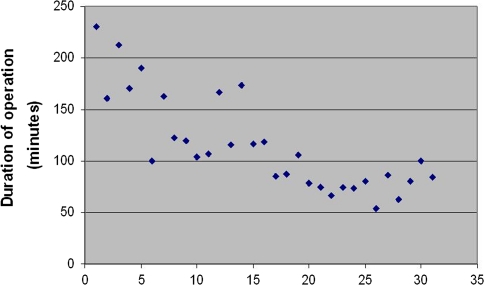

The surgery for all 31 patients was performed by the same surgical team. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy was successfully performed for 30 of the 31 patients (96.7%). One early conversion to standard laparoscopy was performed due to an intrahepatic gallbladder and an overlying left hepatic lobe that prevented achievement of optimal retraction of the Hartman’s pouch. The mean operative time (skin to skin) was 115 min (range, 54–230 min), and the times shortened along the learning curve (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The advancement in operative time along the learning curve. The first procedure has taken 230 min while the latest ones took only 54–80 min

The earlier-mentioned solutions used to overcome the technical challenges provided the following advantages:

The reduced external diameter of the low-profile trocars and the fact that only one of these trocars had a valve for carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation minimized collision of instruments.

The versatility of the flexible endoscope achieved a superior operative view and enabled adjustment of visual angles as the procedure required.

Alternating the insertion port of the 30° laparoscope with the other instruments resulted in improved visualization and dissection capability.

The use of articulating instruments and endo-retractors improved the surgeon’s ability to perform both a safe and efficient procedure.

Familiarity with these techniques resulted in a decreased operative time over the course of our experience.

The mean hospital stay was 1.7 days (range, 1–7 days). No complications occurred for the 30 patients who underwent surgery via the single-incision approach.

At the first outpatient follow-up visit on postoperative days 7 to 10, all the patients expressed satisfaction with the procedure and its cosmetic result. All the patients reported an uneventful return to their usual daily activities at that time.

Discussion

Single-incision laparoscopic surgery is an attractive approach for cholecystectomy. However, several significant obstacles must be overcome before widespread application of this technique can be expected. Recent studies have used different technical solutions for these obstacles with varying success and complication rates [14–21].

Based on our experience, low-profile trocars, articulating laparoscopic tools, and the use of endo-retractors transform single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy, making it both feasible and safe. Larger series of single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy have been presented [22, 23], but in the aspect of technical novelty, we believe this series to be of special interest.

At our institution, we do not perform routine intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) during cholecystectomy, and the current series did not include patients who needed this procedure. If IOC is needed, we believe it could be performed using the single-incision approach without major technical problems.

Our follow-up evaluation found that immediate postoperative pain levels were not lower than those recorded for the population of patients who underwent standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Despite this finding, it is worth mentioning that all 30 patients successfully treated with single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy returned to work within 7 to 10 days, which may indicate faster recovery after this procedure.

The cosmetic results of SILS are clearly superior to those of standard laparoscopy. With proper placement of the incision within or at the superior border of the umbilicus, none of our patients had a visible scar after full recovery.

Conclusion

Single-incision laparoscopic surgery is a technically challenging surgical approach. Increased operative times are expected at the beginning of each surgeon’s learning curve, but our initial experience indicates that such a curve is expected to be steep for experienced surgeons. To overcome the technical obstacles and to perform single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy with safety similar to that for standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy, dedicated tools for this surgical approach are needed, as discussed earlier. With such tools, SILS is a safe and feasible approach for cholecystectomy.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

Noam Shussman has no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose. Dr. Horgan has stock options in Novare Surgical. Dr. Mintz is a medical advisor to Virtual Ports Ltd. Drs. Shussman, Schlager, Elazary, Khalaileh, Keidar, Talamini, and Rivkind have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Cameron JL, Gadacz TR. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1991;213:1–2. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199101000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gadacz TR, Talamini MA, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 1990;70:1249–1262. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)45282-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuschier A, Terblanche J. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: evolution, not revolution. Surg Endosc. 1990;4:125–126. doi: 10.1007/BF02336585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips E, Daykhovsky L, Carroll B, Gershman A, Grundfest WS. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: instrumentation and technique. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1990;1:3–15. doi: 10.1089/lps.1990.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tagaya N, Kita J, Takagi K, Imada T, Ishikawa K, Kogure H, Ohyama O. Experience with three-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1998;5:309–311. doi: 10.1007/s005340050051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reardon PR, Kamelgard JI, Applebaum B, Rossman L, Brunicardi FC. Feasibility of laparoscopic cholecystectomy with miniaturized instrumentation in 50 consecutive cases. World J Surg. 1999;23:128–132. doi: 10.1007/PL00013163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung KF, Lee KW, Cheung TY, Leung LC, Lau KW. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: two-port technique. Endoscopy. 1996;28:505–507. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kagaya T. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy via two ports, using the “Twin-Port” system. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:76–80. doi: 10.1007/s005340170053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ngoi SS, Goh P, Kok K, Kum CK, Cheah WK. Needlescopic or minisite cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:303–305. doi: 10.1007/s004649900971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tacchino R, Greco F, Matera D. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: surgery without a visible scar. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:896–899. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0147-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elazary R, Khalaileh A, Zamir G, Har-Lev M, Almogy G, Rivkind AI, Mintz Y. Single-trocar cholecystectomy using a flexible endoscope and articulating laparoscopic instruments: a bridge to NOTES or the final form? Surg Endosc. 2009;23:969–972. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0289-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rolanda C, Lima E, Pego JM, et al. Third-generation cholecystectomy by natural orifices: transgastric and transvesical combined approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mintz Y, Horgan S, Cullen J, Ramamoorthy S, Chock A, Savu MK, Easter DW, Talamini MA. NOTES: the hybrid technique. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:402–406. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romanelli JR, Roshek TB III, Lynn DC, Earle DB. Single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: initial experience. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(6):1374–1379. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirschniak A, Bollmann S, Pointner R, Granderath FA. Transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: preliminary experiences. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:436–438. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181c3f12b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts KE, Solomon D, Duffy AJ, Bell RL. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a surgeon’s initial experience with 56 consecutive cases and a review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(3):506–510. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1116-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philipp SR, Miedema BW, Thaler K. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy using conventional instruments: early experience in comparison with the gold standard. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:632–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chow A, Purkayastha S, Aziz O, Paraskeva P. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery for cholecystectomy: an evolving technique. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(3):709–714. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Binenbaum SJ, Teixeira JA, Forrester GJ, Harvey EJ, Afthinos J, Kim GJ, Koshy N, McGinty J, Belsley SJ, Todd GJ. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy using a flexible endoscope. Arch Surg. 2009;144:734–738. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuon Lee S, You YK, Park JH, Kim HJ, Lee KK, Kim DG. Single-port transumbilical laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a preliminary study in 37 patients with gallbladder disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:495–499. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ersin S, Firat O, Sozbilen M. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: is it more than a challenge? Surg Endosc. 2010;24:68–71. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0543-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernandez JM, Morton CA, Ross S, Albrink M, Rosemurgy AS. Laparoendoscopic single-site cholecystectomy: the first 100 patients. Am Surg. 2009;75:681–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivas H, Varela E, Scott D. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: initial evaluation of a large series of patients. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(6):1403–1412. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0786-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]