Abstract

TLR activation is an important component of innate immunity but also contributes to the severity of inflammatory diseases. Cysteine cathepsins (Cat) B, L and S, which are endosomal and lysosomal proteases, participate in numerous physiological systems and are upregulated during various inflammatory disorders and cancers. Macrophages have the highest cathepsin expression and are major contributors to inflammation and tissue damage during chronic inflammatory diseases. We investigated the impact of TLR activation on macrophage Cat B, L and S activities using live-cell enzymatic assays. TLR2, TLR3 and TLR4 ligands increased intracellular activities of these cathepsins in a differential manner. TLR4-induced cytokines increased proteolytic activities without changing mRNA expression of cathepsins or their endogenous inhibitors. Neutralizing antibodies recognizing TNF-α, IL-1β and IFN-β differentially eliminated cathepsin upregulation. These findings indicate cytokines induced by MyD88-dependent and -independent signaling cascades regulate cathepsin activities during macrophage responses to TLR stimulation.

Keywords: cathepsins, endosomal proteases, inflammatory response, macrophage activation, Toll-like receptors, signal transduction, pattern recognition receptors

1. Introduction

TLR cell activation initiates immune responses to microbial pathogens via recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns. In mammals at least 12 membrane proteins are currently identified as TLR family members, named TLR 1–12, and each receptor has different specificities [1]. The various TLR ligands stimulate differential cytokine production, which can be attributed to the signaling pathways activated. Pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 are rapidly induced upon TLR4 and TLR2 activation of multiple cell types [2–5], while TLR3 ligands cause robust IFN-β secretion. TLR4 signal transduction involves pathways that are dependent and independent of the MyD88 adaptor molecule. TLR2 signals only through MyD88, while TLR3 utilizes the Trif adaptor molecule that is independent of MyD88. TLR signaling cascades lead to activation of MAPK pathways and transcription factors, including NF-κB and AP-1, which regulate the inflammatory response [6,7].

Signal transduction through TLR is implicated as contributing to severity of numerous diseases, such as atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Crohn’s disease [8–10]. As an example, TLR2 activation of multiple cell types with either endogenous or exogenous ligands promotes atherogenesis during atherosclerosis [9], and is associated with the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Furthermore, TLR stimulation enhances proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells by increasing expression of matrix metalloproteases and integrins [11]. These diseases are also accompanied with increased proteolytic activity and expression of cysteine cathepsins [12]. Possibly, TLR signal transduction affects cysteine cathepsins as well, however their regulation by TLR activation has not been well elucidated.

Cysteine cathepsins are endosomal and lysosomal proteases belonging to the papain family. These proteases are involved in other physiological processes; in addition to antigen processing that is critical for CD4+ T cell responses [12,13]. Cysteine cathepsins are candidate disease markers due to their increased expression and activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, atherosclerosis and a multitude of cancers [12]. Infiltrating immune cells are thought to be the major cause of tissue destruction in inflammatory diseases, and the cells with the highest cathepsin expression are the GR-1+/Mac-1+ myeloid cell population [14]. Cathepsins (Cat) B, L and S hydrolyze extracellular matrix components, such as collagen and laminin, which have an important role in joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis [12]. During tumor angiogenesis, the highest cathepsin activities are detected at the invasive tumor fronts, indicating their role, also, in metastasis [15].

A few studies have investigated the effects of TLR4 ligand, LPS, on cathepsins in dendritic cells and smooth muscle cells, while the impact of other TLR ligands on these proteases has been largely unexplored. Although macrophages have the highest expression of cathepsins in diseased tissues [14], TLR regulation of these proteases has not been previously investigated in macrophages. The present study focused on Cat B, L and S activities in macrophages during inflammatory responses to both MyD88-dependent and -independent TLR ligands. Macrophage activation with various TLR ligands increased cathepsin activities in a differential manner. Enhanced proteolytic activity was not due to increased cathepsin mRNA expression or decreased expression of endogenous inhibitors. Augmented cathepsin activities occurred within bystander cells, indicating the involvement of secreted products. Antibody neutralization of IL-1β, TNF-α and IFN-β inhibited cathepsin upregulation in TLR-stimulated cells, which was reversed by addition of exogenous cytokines. These results suggest that TLR signaling cascades do not directly regulate cathepsins, instead these proteases are regulated by cytokines secreted in response to TLR activation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

Female C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were used from 6 to 9 weeks of age. Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. Research complied with all relevant laws, guidelines, and policies.

2.2. Cells

Bone marrow cells were obtained from femurs of mice by flushing and cultured in L-929-conditioned medium as source of M-CSF from 7 to 9 days to generate bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) [16]. Murine macrophage P388D1 and human monocyte THP-1 cell lines (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were grown in RPMI 1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Biofluids, Rockville, MD), L-glutamine and antibiotics. A bone marrow murine macrophage cell line was provided by Dr. Howard Young (National Institutes of Health, Frederick, MD) and cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS, L-glutamine and antibiotics. Murine macrophage/microglial cell line EOC 20 (American Type Culture Collection) was grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS, L-glutamine, antibiotics and 10% LADMAC- (American Type Culture Collection) conditioned medium as a source of CSF-1.

2.3. In vitro TLR stimulation

Bacterial LPS from E. coli 055:B5, peptidoglycan (PGN) from S. aureus, and polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid sodium salt (Poly I:C) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Macrophages at 2 × 106 cells/well were cultured in complete medium with and without various LPS, PGN or Poly I:C concentrations at 37°C for time points ranging from 6 to 48 h. Cells were harvested, washed twice in PBS, and cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion. Protease activity of cathepsins in live cells was assessed using flow cytometry or spectrofluorophotometry as described below. For subsequent experiments, cells were incubated with 1 µg/ml LPS, 4 µg/ml PGN, 10 µg/ml Poly I:C or complete medium for 6 or 24 h. Cell-free culture supernatants were collected, and RNA was isolated as described below.

2.4. In vivo TLR stimulation

C57BL/6J female mice were injected i.p. with 1 ml of 4% thioglycollate to elicit peritoneal macrophages. On day 5, mice were injected i.p. with 25 µg of LPS (Sigma-Aldrich L2654) or PBS control. Peritoneal cells were harvested by lavage 24 h later, and live cell cathepsin assays using spectrofluorophotometry were performed as described below.

2.5. Live cell cathepsin assays

Magic Red ™ (MR)-conjugated selective substrates (Immunochemistry Technologies, LLC, Bloomington, MN) for Cat B, L and S were Z-Arg-Arg-MR-Arg-Arg, Z-Phe-Arg-MR-Arg-Phe, and Z-Val-Val-Arg-MR-Arg, respectively. Respective 7-aminomethyl-coumarin (AMC)-conjugated substrates (Bachem Bioscience, King of Prussia, PA) for Cat B, L and S were Z-Arg-Arg-AMC, Z-Phe-Arg-AMC, and Z-Val-Val-Arg-AMC. Stock substrate solutions in DMSO were stored at −80°C. Live cell assays using these conjugated substrates were performed as previously described [17]. Briefly, 4 × 106 cells/ml were incubated with 6 µM Cat B or Cat L, or 24 µM Cat S MR-conjugated substrate for 45 min at 37°C. Control cells were incubated with the corresponding DMSO concentration lacking a substrate. Cells were washed twice with PBS containing 0.02% sodium azide to remove excess substrate, and fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde in PBS before analysis. Red fluorescence intensity of cells was measured with logarithmic amplification using a Becton Dickinson FACScan equipped with a 15 mW 488 nm argon laser and appropriate excitation filters (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Data on 20,000 cells were collected, and forward-angle and side scatter gates were set to exclude dead cells and cell clumps. Values are expressed as the net mean red fluorescence intensity (MFI).

For live cell assays using AMC-conjugated substrates, 1 × 106 cells/ml in PBS were incubated with 10 µM selective Cat B, L or S substrate for 1 h at 37°C. Fluorescence was measured by a Shimadzu spectrofluorophotometer RF5000 (Columbia, MD) with an excitation wavelength of 370 nm and emission wavelength of 460 nm. One activity unit is 1.0 fluorescence unit equivalent to 0.012 nmol product produced/h. Background controls were cells incubated with DMSO alone. Values are expressed as net activity/106 cells. Fold-increase values were calculated by dividing fluorescent values of TLR-stimulated cells by values of medium control cells.

2.6. ImageStream® cell analysis

Cells were incubated without or with 1 µg/ml LPS for 24 h and harvested as above. Cells at 1 × 106 cells/ml in PBS were incubated with 6 µM Cat L or B, or 15 µM Cat S MR-conjugated substrate for 45 min at 37°C. Cells were then incubated with 100 nM LysoTracker DND-26 (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in DMSO for another 15 min at 37°C, and cells were analyzed using ImageStream® Cell Analysis System (Amnis Corporation, Seattle, WA) courtesy of Amnis Corporation and University of Virginia, School of Medicine Flow Cytometry Core Facility (Charlottesville, VA). The ImageStream System is equipped with a brightfield lamp, 488 nm laser, and six-channel CCD camera. Fluorescence intensity and similarity bright detail score analyses were performed courtesy of Dr. Philip Morrissey (Amnis Corporation) as described [18]. Similarity bright detail score calculates the relative intensities in individual pixels of cells at the same location in paired images using an algorithm. The value indicates how well fluorescence intensity due to LysoTracker DND-26 in channel 3 with emission wavelengths from 500 to 560 nm correlates with MR fluorescence intensity in channel 5 with emission wavelengths from 595 to 660 nm.

2.7. Semiquantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Forward and reverse primers for Cat B, Cat L and β-actin were previously published [19]. Cat S primers (forward primer: 5′-TAA TCG GAC ATT GCC TGA CA-3′; reverse primer: 5′-CTG GAA AGC TTC GGT CAT GT-3′), cystatin A primers (forward primer: 5′-GCA CAG CTC GAA GAG GAA AC-3′; reverse primer: 5′-CAG CTC ATC ATC CTC GGT TT-3′), cystatin B primers (forward primer: 5′-GTC CCA GCT TGA ATC GAA AG-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GGG TCA AAG GCT TGT TTT CA-3′), and cystatin C primers (forward primer: 5′-TCG CTG TGA GCG AGT ACA AC-3′; reverse primer: 5′-ATC TGG AAG GAG CAG AGT GC-3′) were synthesized and purified by the Virginia Commonwealth University DNA core laboratory (Richmond, VA). Cat B, L and S primers produce a 237-bp product from bases 447–683, a 294-bp product from bases 410–704, and a 241-bp product from bases 357–597, respectively. Cystatin B primers produce a 174-bp product from bases 74–244 and cystatin C primers produce a 217-bp product from bases 146–362. Cystatin A primers produce a 210-bp product from bases 73–282, and β-actin primers produce a 451-bp product from bases 415 to 865. RNA at 1µg was treated with amplification grade DNase I (Invitrogen) for 20 min at room temperature to remove genomic DNA. Yield was determined by absorbance at 260 nm, and purity was verified by 260:280 and 260:230 nm absorbance ratios. RNA was reversed transcribed with Superscript™ first strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen) using oligo-dT primers according to manufacturer’s directions. Controls omitted reverse transcriptase to verify that genomic DNA was not amplified by PCR. Products were amplified by PCR using Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). Following initial denaturizing at 94°C for 2 min, samples were denatured at 94°C for 30 s, annealed at 55°C for 30 s and extended at 72°C for 30 s. Each cDNA was amplified separately to maintain linearity of the reactions. PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide, and bands were visualized by a UV transilluminator with a CCD camera. Band intensities were quantified with AlphaEase FluorChem 8900 (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, CA). Relative expression for each sample was calculated by dividing the intensity of the target band by the β-actin band intensity.

2.8. Activation of non-responsive bystander cells with culture supernatants

P388D1 cells at 2 × 106 cells/well were cultured in complete RPMI without or with 1µg/ml LPS, and cell-free culture supernatants were collected at 6 or 24 h. Cell-free culture supernatants were concentrated with Centricon-10 or Amicon-4 microconcentrators (Millipore, Jaffrey, NH) two-fold, filter sterilized and stored at −20°C. EOC 20 cells at 2 × 106 cells/well were cultured for 24 h in complete DMEM with P388D1-culture supernatants equivalent to 60% in the original P388D1 cultures. Cells were harvested and washed, and cathepsins activities in EOC 20 cells were assessed using AMC-conjugated substrates as described above. Fold-increase was calculated by dividing fluorescence values of EOC 20 incubated with LPS-stimulated culture supernatants by the values of cells incubated with medium control supernatants.

2.9. TNF-α and IL-1β studies

Monoclonal anti-TNF-α (clone TN3–19) antibody (mAb) was purchased from e-Bioscience (San Diego, CA) and anti-IL-1β (clone 30311) mAb was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). P388D1 cells were stimulated with 1µg/ml LPS as above, and cell-free culture supernatants from medium control and LPS-stimulated cultures were collected at 6 h. Cell-free culture supernatants were concentrated and filter sterilized as described above. Culture supernatants were then incubated with 3 µg/ml anti-TNF-α, 20 µg/ml anti-IL-1β mAb, both, or control IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C for 1 h. The selected mAb concentrations gave maximal specific inhibition in initial dose-response analyses. All antibodies (Ab) were functional-grade and endotoxin levels were < 0.1 Endotoxin Unit/µg protein. EOC 20 cells at 2 × 106 cells/well were cultured in complete DMEM and Ab-treated culture supernatants at a 2:1 ratio for 24 h. Cells were harvested and washed, and cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion. Cathepsins activities in viable EOC 20 cells were measured using AMC-conjugated substrates as described above. Percent inhibition of cathepsin activity was calculated as 1-[(activity from neutralizing Ab-treated culture supernatants from LPS-stimulated P388D1 cells – baseline)/(activity from the appropriate control IgG-treated culture supernatant from LPS-stimulated P388D1 cells – baseline)] × 100%. Baseline was cathepsin activity in the appropriate control IgG-treated culture supernatant from medium controls.

P388D1 cells were incubated without or with various concentrations of carrier-free recombinant mouse TNF-α or IL-1β (R&D Systems) with < 0.1 Endotoxin Unit/µg protein for 24 h, and cathepsin activities were measured in live cells as above. For reversal experiments, cells were pre-incubated with 10 µg/ml anti-TNF-α plus 20 µg/ml anti-IL-1β mAb, or 30 µg/ml control IgG for 30 min. Medium, 1 µg/ml LPS, or 1 ng/ml TNF-α plus 16 pg/ml IL-1β was added to cultures containing neutralizing antibodies, and cells were incubated for 12 h. Medium, or 1 ng/ml TNF-α plus 16 pg/ml IL-1β was added to cultures, and cells were incubated for an additional 12 h. Cells were harvested, and cathepsin activities were measured as above.

2.10. IFN-β studies

P388D1 cells were incubated without or with various concentrations of carrier-free recombinant mouse IFN-β (PBL InterferonSource, Piscataway, NJ) with < 0.1 Endotoxin Unit/µg protein for 24 h, and cathepsin activities in cells were measured as above. For reversal experiments, cells were pre-incubated with 10 µg/ml hamster IgG (Cappel MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) or anti-IFN-β (clone MIB-5E9.1) (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) for 30 min. Both Ab were functional-grade, and endotoxin levels were < 0.1 Endotoxin Units/µg protein. Cells were then incubated without or with 10 µg/ml Poly I:C for 12 h. Medium or 250 U/ml IFN-β was added to cultures containing neutralizing antibody, and cathepsin activities were measured after an additional 12 h as above.

2.11. Statistical analyses

Parametric analysis of variance was performed by two-tailed Student’s t test. Cathepsin activities in TLR ligand-treated groups were compared with medium controls. Fold-increase values were compared to the value of 1.0 by ANOVA with Dunnet’s post-hoc analysis. Percent inhibition was compared to the value of 0% inhibition. Significance was designated at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. TLR ligands increase cathepsin activities in macrophages

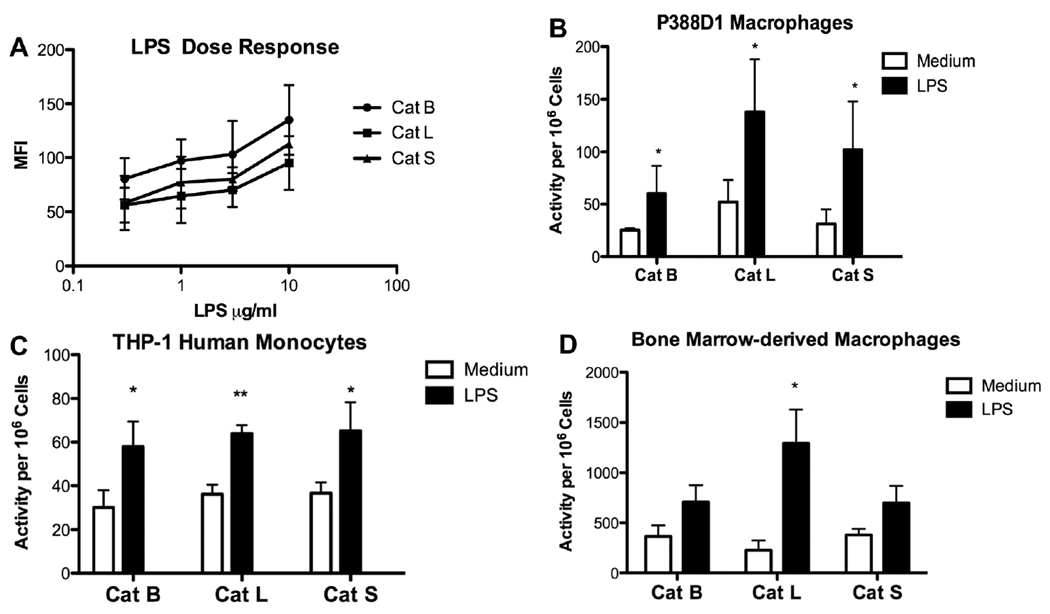

We investigated the effects of TLR ligands on cysteine cathepsin activity in multiple murine macrophage cell lines, human monocyte cell line and primary BMDM. To measure cathepsin activity inside live cells, cell permeable, selective substrates conjugated with AMC or MR were utilized. The substrates for the two assays have the same amino acid target sequence with different leaving groups, and selectivity of substrate cleavage was previously established [17]. Fluorescent AMC and MR products were measured by spectrofluorophotometry or flow cytometry, respectively, based on their spectral properties [17]. LPS at 0.3µg/ml caused cathepsin activities to increase at 24 h, and more significant augmentations were observed with 1 µg/ml or higher concentrations in a murine bone marrow macrophage cell line (Fig. 1A). Time course studies revealed that cathepsin upregulation occurred in cell lines stimulated with 10 µg/ml LPS by 18 h with average fold-increase in MFI values for Cat B, L and S of 1.4, 1.8 and 1.4, respectively. At lower LPS concentrations, upregulated cathepsin activities were detected at 24 h. When murine P388D1 macrophage or human THP-1 monocyte cell lines were stimulated with 1 µg/ml LPS for 24 h, Cat B, L and S activities significantly increased (Figs. 1B and C). Activities remained elevated at 48 h, but were not significantly different from the levels at 24 h (data not shown). BMDM had higher basal levels of cathepsin activity than the cell lines (Fig. 1D). In contrast to cell lines, cathepsin activities in BMDM increased with lower LPS doses and upregulation occurred as early as 12 h (Fig 1D). Cat L showed the greatest augmentation in both P388D1 cells and BMDM. Upregulation of cathepsins also occurred in vivo within peritoneal macrophages after i.p. LPS administration with average fold-increase in fluorescence values for Cat B, L and S of 1.2, 1.6, and 1.4, respectively. Hence, LPS activation enhanced proteolytic activity in the monocyte/macrophages examined.

Fig. 1.

LPS stimulation increases cathepsin activities in live macrophages from multiple origins. (A) Bone marrow macrophage cell line was incubated with 0.3 µg/ml to 10 µg/ml LPS for 24 h. Cells were harvested, and activities of the indicated cathepsins were measured using a flow cytometric assay. MFI values are mean ± SD from two separate experiments. (B) P388D1 and (C) THP-1 cells were stimulated with or without 1 µg/ml LPS for 24 h, and cathepsin activities were assayed using a spectrofluorophotometric assay. (D) Bone marrow-derived macrophages were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 12 h and cathepsin activities were assayed using a spectrofluorophotometric assay. Data are mean ± SD from at least three separate experiments. LPS vs. medium: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

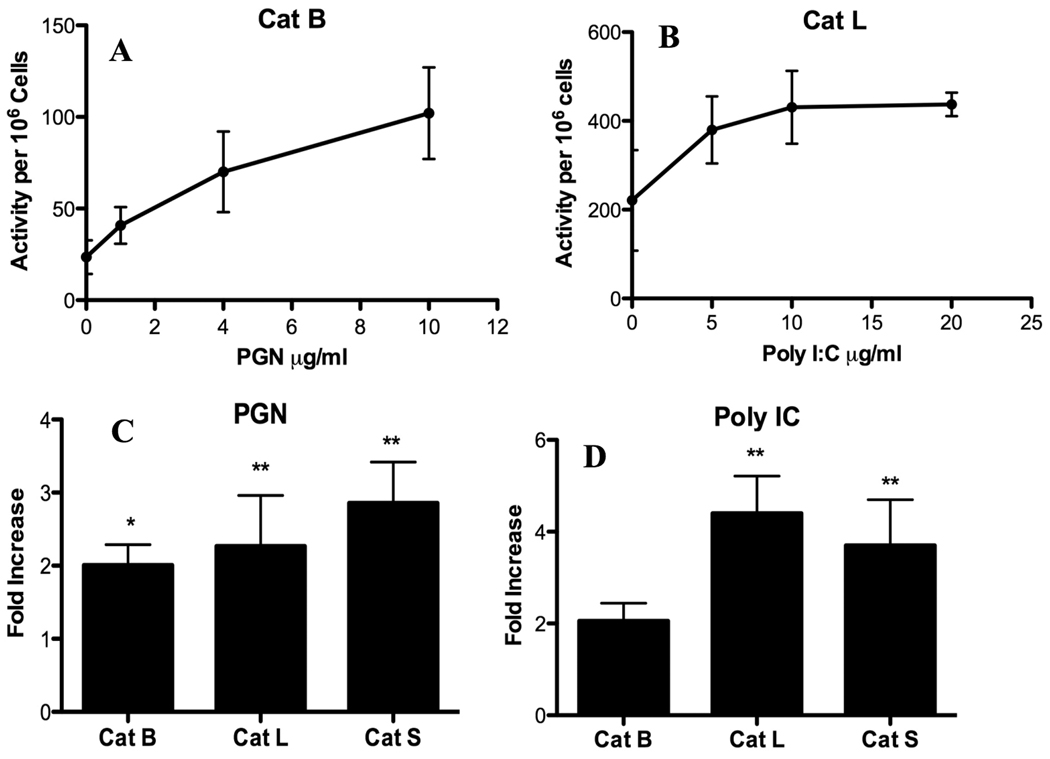

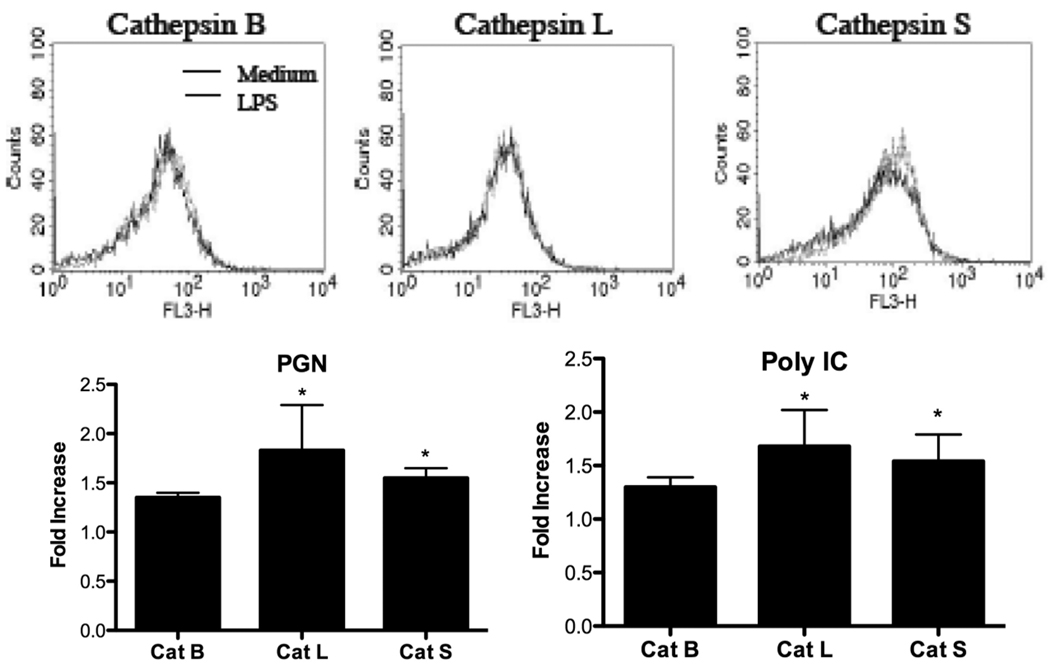

The study was extended to other TLR ligands that signal through MyD88-dependent or – independent pathways. Dose response studies were performed with PGN, a TLR2 ligand, and Poly I:C, a TLR3 ligand. In a dose-dependent manner, PGN increased Cat B activity (Fig. 2A) and Poly I:C enhanced Cat L activity (Fig. 2B) in P388D1 cells. Likewise, these TLR ligands upregulated activities of other cathepsins inside viable macrophages in a dose-dependent manner (data not shown). P388D1 macrophages stimulated with 4 µg/ml PGN for 24 h significantly increased Cat L and S activities compared with medium controls (Fig. 2C). While Cat B showed enhanced activity, this increase was not as high as that observed for Cat L and S. Similar results were obtained when P388D1 cells were stimulated with 10 µg/ml Poly I:C (Fig. 2D). Cat L and S activities were significantly increased, while enhancement of Cat B activity was not statistically significant. These results suggest Cat L and S upregulation occurred when either MyD88-dependent or –independent pathways were activated.

Fig. 2.

MyD88-dependent and -independent TLR ligands increase cathepsin activities. P388D1 macrophages were incubated with or without the indicated concentrations of (A) PGN or (B) Poly I:C for 24 h. P388D1 macrophages were stimulated with or without (C) 4 µg/ml PGN or (D) 10 µg/ml Poly I:C for 24 h. Cathepsin activities in live cells were assessed by spectrofluorophotometry. Data are mean ± SD from three or more separate experiments. Fold-increase was calculated by dividing fluorescent values of stimulated cells by values of medium controls. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 compared with the value of 1.0.

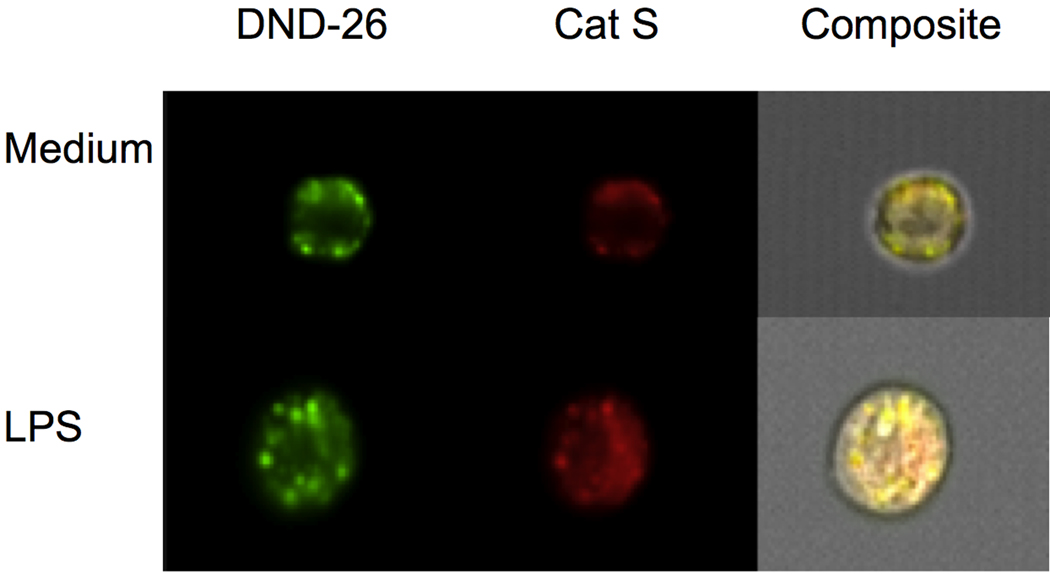

3.2. Active cathepsins in LPS-stimulated cells remain localized to acidic organelles

To insure increased fluorescence was due to enhanced cathepsin activity within acidic intracellular organelles, the ImageStream®Cell Analysis System was employed. This system combines FACS and fluorescence microscopy allowing one to determine the intracellular location of fluorescent molecules, as well as quantitate changes in fluorescence intensities [18]. As shown in Fig. 3, the red fluorescent product generated by cleavage of MR-conjugated Cat S substrate had a punctate cytoplasmic fluorescence pattern in LPS-stimulated cells and medium control cells. The cleavage product co-localized with a green fluorescent acidotrophic probe as revealed by the yellow fluorescence in the composite, indicating that the active protease remained inside acidic vesicles, and paralleled results obtained using confocal microscopy (data not shown). Similar results were obtained for Cat B and L substrates, and similarity bright detail scores supported co-localization (2.87 for Cat B, 2.97 for Cat L and 2.22 for Cat S). The MFI for the green fluorescent acidotrophic probe increased from 33931 for medium control cells to 39469 for LPS-stimulated cells. Red channel MFI of Cat B, L and S products in LPS-stimulated cells also increased compared with medium control values from 63,833 to 89,259, 61,384 to 104,810, and 105,907 to 117,262, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Active cathepsin S in LPS-stimulated cells localizes within acidic organelles. Macrophages were cultured without or with 1 µg/ml LPS for 24 h, harvested and then incubated with MR-conjugated Cat S substrate and LysoTracker DND-26. Analysis was performed using the ImageStream®Cell Analysis System to measure fluorescent intensity and localize intracellular red fluorescent hydrolyzed product from Cat S substrate and green fluorescent LysoTracker DND-26. Yellow fluorescence in composite indicates co-localization.

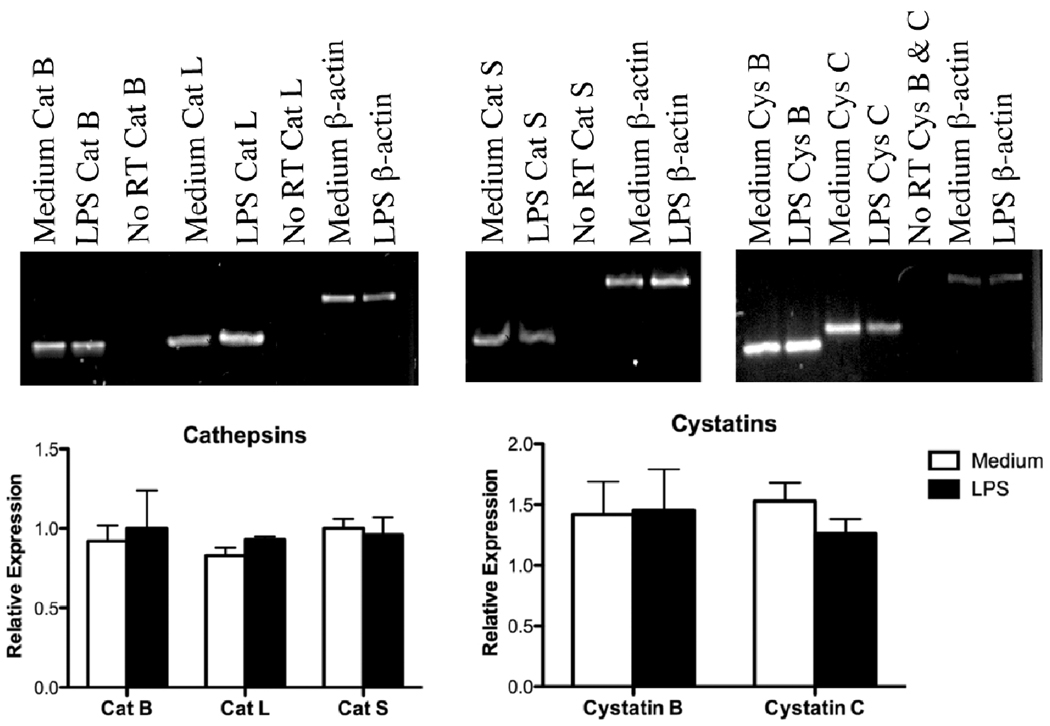

3.3. Cathepsin and cystatin mRNA expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages

After LPS activation, mRNA expression of cathepsins and their endogenous inhibitors was examined at early and late time points to detect possible transient changes. RNA was isolated from P388D1 cells stimulated with 1 µg/ml LPS for 6 h or 24 h, and semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed. Cystatin A mRNA, which is an endogenous cysteine cathepsin inhibitor, was not detected in LPS-stimulated or medium control macrophages at either time point using 44 amplification cycles (data not shown). At the 6-h time point, no changes in the band intensities for transcripts of Cat B, L, and S or the endogenous inhibitors, cystatins B and C were observed (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 4, mRNA expression of Cat B, L, and S did not significantly increase at 24 h. Likewise, cystatin B and C mRNA expression was not significantly altered at 24 h (Fig. 4). Changes in transcript levels encoding cathepsins or their inhibitors could not account for increased cathepsin activities.

Fig. 4.

Expression of cathepsins and cystatins mRNA in LPS-stimulated cells. P388D1 cells were cultured with or without 1 µg/ml LPS for 24 h. Cells were lysed and RNA was prepared for semiquantitative RT-PCR. Cat B, L and S, cystatins (Cys) B and C, and β-actin cDNA were amplified at different cycle numbers to maintain linearity. No RT samples are reactions lacking reverse transcriptase. Top panels are representative gels. Bottom panels are band intensities quantified by densitometry that were normalized relative to β-actin. Relative expression is mean ± SD from three independent preparations.

3.4. Activation of LPS non-responsive bystander cells

Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, are readily produced by macrophages activated by LPS and PGN [2–4], which may mediate increased cathepsin activities. EOC 20 macrophage/microglial cell line is derived from C3H/HeJ mice. Cells derived from these mice are LPS non-responsive due to a mutation within the cytoplasmic domain of TLR4, but are responsive to PGN and Poly I:C for cytokine production [20]. As expected, EOC 20 cells cultured with LPS did not increase cathepsin activities (Fig. 5). EOC 20 cells are propagated in LADMAC-conditioned medium containing CSF-1. Cathepsin activities in EOC 20 cells were not altered by the LADMAC-conditioned medium when compared with cells cultured in medium lacking CSF-1 (data not shown). We investigated the ability of EOC 20 cells to increase cathepsin activities in response to PGN and Poly I:C. Similar to P388D1 cells (see Fig. 2), EOC 20 cells significantly upregulated Cat L and S activities when stimulated with PGN or Poly I:C (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

PGN and Poly I:C increase cathepsin activities in LPS non-responsive cells. EOC 20 cells were incubated without or with 1 µg/ml LPS, 4 µg/ml PGN or 10 µg/ml Poly I:C for 24 h. Cat B, L and S activities in live cells were assessed by flow cytometry (top panels) or spectrofluorophotometry (bottom panels). Histograms are representative of 3 separate experiments. Fold-increase was calculated as described in Fig. 2 legend, and is mean ± SD from three or more separate experiments. Medium control values for PGN panel were 41.5 ± 7.3, 70.3 ± 8.6 and 83.2 ± 15.3 Activity/106 cells for Cat B, L and S, respectively. Medium control values for Poly I:C panel were 27.8 ± 3.0, 41.7 ± 9.1 and 61.8 ± 17.7 Activity/106 cells for Cat B, L and S, respectively. *p < 0.05 compared with the value of 1.0.

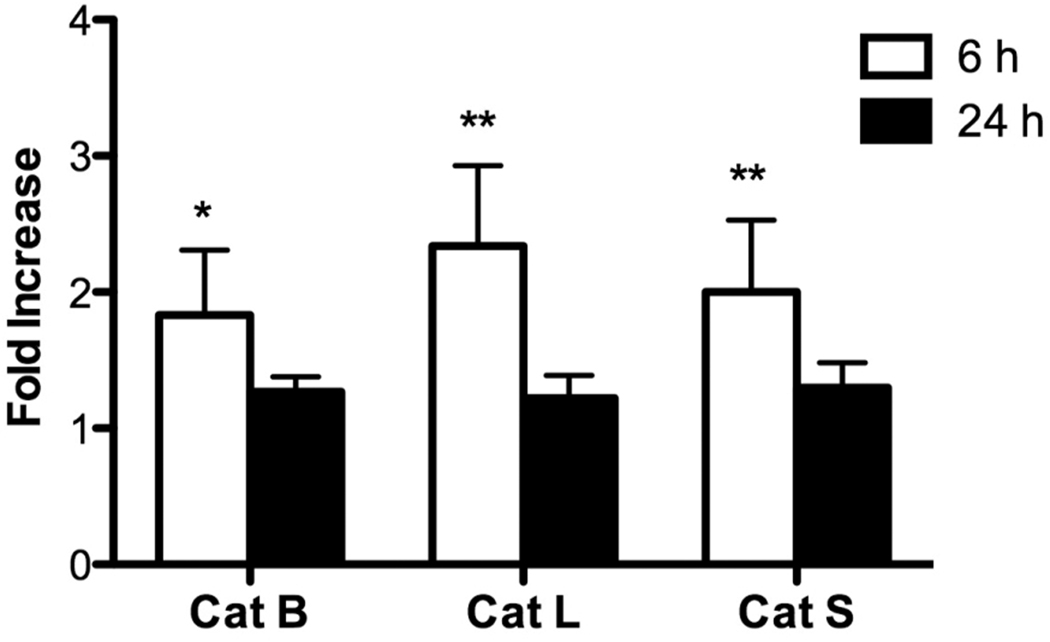

To investigate the role of cytokines, P388D1 macrophages were cultured in medium with or without LPS for 6 or 24 h. Then, EOC 20 cells were incubated with P388D1 cell-free culture supernatants for 24 h, and cathepsin activities were assessed using AMC-conjugated substrates. Before EOC 20 cells were incubated with culture supernatants, cathepsin activities in the supernatants were measured, and the activity levels were < 1.0% present within one cell. The 24-h LPS culture supernatants had no effect on cathepsin activities in EOC 20 cells (Fig. 6). Furthermore, basal levels of cathepsin activities in EOC 20 cells were similar to the levels in cells cultured with P388D1 medium control supernatants, suggesting a lack of spontaneous cytokine secretion from P388D1 cells. In contrast, 6-h LPS culture supernatants significantly increased activities of the three cathepsins in EOC 20 cells, indicating that early-secreted products enhanced cathepsin activity (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Culture supernatants from LPS-stimulated cells increase cathepsin activities in LPS non-responsive cells. P388D1 macrophages were cultured with medium or 1 µg/ml LPS for 6 or 24 h. Cell-free culture supernatants were harvested and concentrated. EOC 20 cell were incubated with culture supernatants for an additional 24 h and harvested. Cathepsin activities in live cells were assayed as in Fig. 2. Fold-increase was calculated by dividing the fluorescence values of cells incubated with LPS-stimulated culture supernatants by the values of cells incubated with medium control culture supernatants. Results are mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Medium control values for 6-h culture supernatants were 36.8 ± 5.7, 81.5 ± 20.9 and 94.0 ± 15.4 Activity/106 cells for Cat B, L and S, respectively. Medium control values for 24-h culture supernatants were 50.1 ± 5.0, 75.4 ± 8.6 and 79.7 ± 11.0 Activity/106 cells for Cat B, L and S, respectively. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 compared with the value of 1.0.

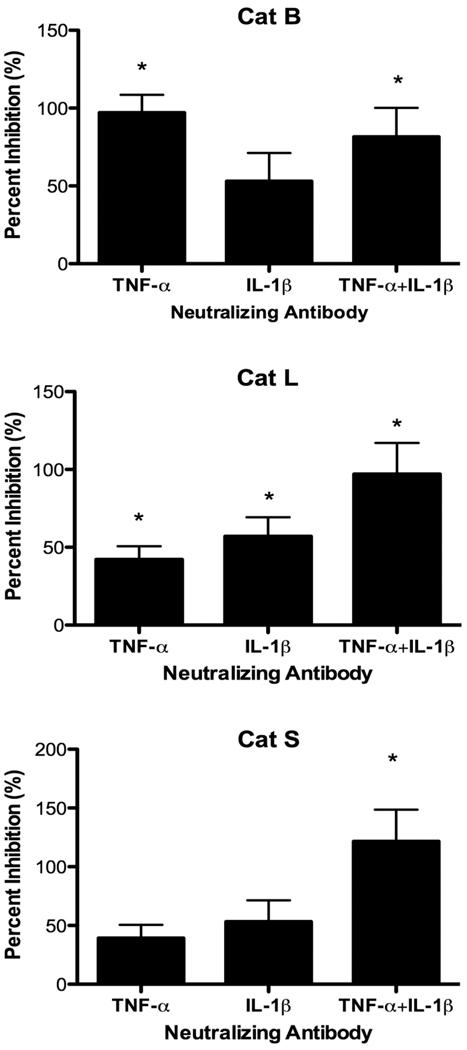

3.5. TNF-α and IL-1β increase cathepsin activities

TNF-α is rapidly released, and other pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, are also secreted from TLR-activated macrophages. To investigate the role of TNF-α and IL-1β, 6-h culture supernatants generated by P388D1 cells were incubated with various concentrations of neutralizing anti-TNF-α or anti-IL-1β mAb to select concentrations for subsequent experiments (data not shown). Control supernatants were treated with corresponding concentrations of control IgG. EOC 20 cells were then incubated with Ab-treated culture supernatants for 24 h. Anti-TNF-α mAb treatment of LPS-stimulated culture supernatants dramatically inhibited upregulation of Cat B activity in EOC 20 cells when compared to IgG-treated control supernatants (Fig. 7). The level of Cat B activity dropped to the medium control level. In contrast, neutralization of IL-1β within LPS-stimulated supernatants caused a decrease, which was not significant, in Cat B activity in EOC 20 cells. Cat L activity in EOC 20 cells was partially reduced by neutralizing either TNF-α or IL-1β alone. When both TNF-α and IL-1β were neutralized simultaneously, complete inhibition of Cat L upregulation occurred, and the combined inhibition was additive (Fig. 7). Again, when both cytokines were neutralized, upregulation of Cat S activity was also abolished in EOC 20 cells, similar to the results for Cat L activity (Fig. 7). These results suggest increased Cat B activity relied on TNF-α, whereas both TNF-α and IL-1β were responsible for Cat L and S upregulation during the LPS response.

Fig. 7.

Neutralization of TNF-α and IL-1β reduces cathepsin activities. P388D1 cells were cultured in medium or 1 µg/ml LPS for 6 h. Cell-free culture supernatants were harvested, concentrated, and treated with 3 µg/ml anti-TNF-α mAb, 20 µg/ml anti-IL-1β mAb, both mAb, or the corresponding concentration of control IgG. EOC 20 cells were incubated with treated culture supernatants for 24 h and harvested, and cathepsin assays with live cells were performed as in Fig. 2. Data are the mean ± SD from three separate experiments. Percent inhibition was calculated as described in the methods, and 100% inhibition corresponds to cathepsin activity in cells incubated with IgG-treated medium control culture supernatants. *p < 0.05 compared with 0% inhibition.

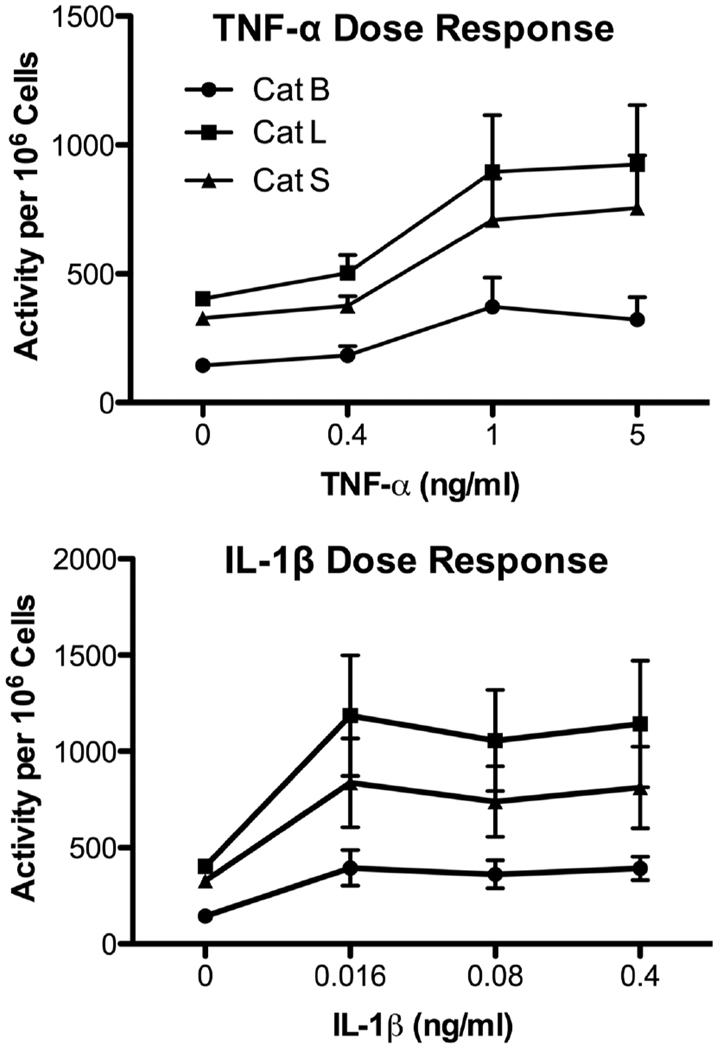

P388D1 cells were then stimulated with recombinant TNF-α or IL-1β in the absence of LPS. TNF-α augmented cathepsin activities in a dose-dependent manner with 1 ng/ml TNF-α yielding maximal stimulation (Fig. 8). Similarly, 16 pg/ml IL-1β significantly enhanced Cat L and S activities (p < 0.05) (Fig.8), while 4 pg/ml IL-1β did not significantly upregulate their activities (data not shown). In agreement with the mAb neutralization study (see Fig. 7), IL-1β slightly increased Cat B activity (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Recombinant TNF-α and IL-1β increase cathepsin activities. P388D1 cells were cultured in medium or various concentrations of recombinant mouse TNF-α (upper panel) or IL-1β (lower panel) for 24 h, and cathepsin activities were measured as in Fig. 2. Values are mean ± SE from three or more separate experiments.

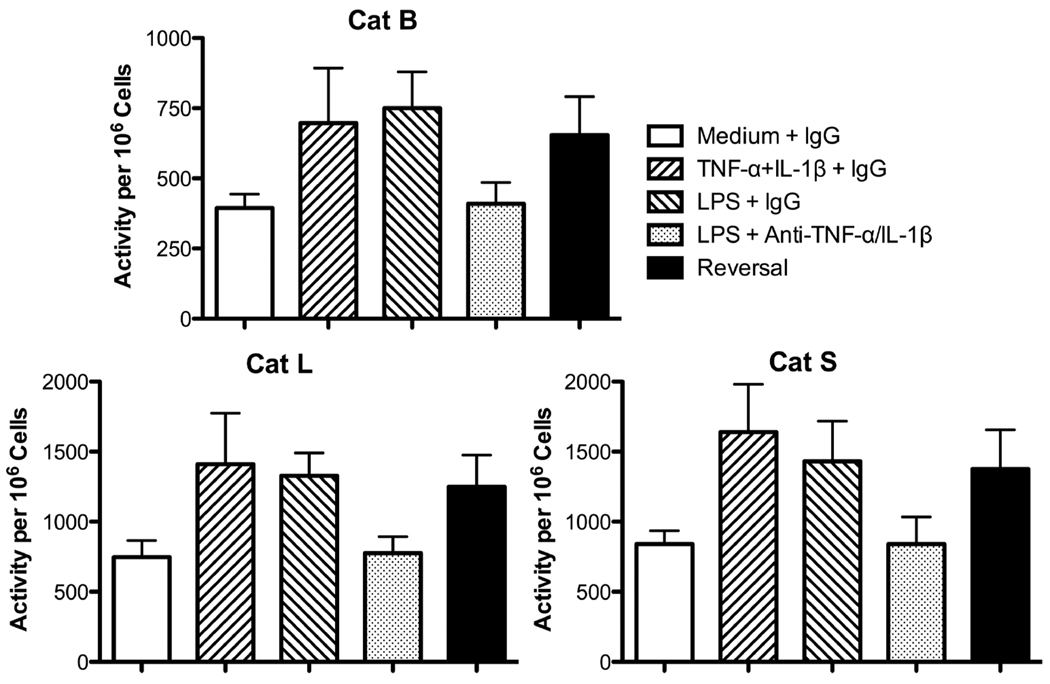

These cytokines were examined for their ability to reverse the inhibitory effects of the neutralizing mAb. For these experiments, P388D1 cells were stimulated with LPS in the presence of both anti-TNF-α and anti-IL-1β mAb, or control IgG for 24 h. At 12 h, 1 ng/ml TNF-α and 16 pg/ml IL-1β were added to LPS cultures containing the neutralizing mAb. The concentrations of the cytokines were selected from their dose-response curves in Fig. 8. As expected, the two cytokines together increased activity of the three cathepsins (Fig. 9). Again, LPS upregulated cathepsin activities (Fig. 9). Analogous to the culture supernatant study, the neutralizing mAb reduced cathepsin activities in LPS-stimulated P388D1 cells to medium control levels (Fig. 9). Addition of exogenous TNF-α and IL-1β at the 12-h time point of culture reversed the mAb inhibition and restored augmented cathepsin activities in LPS-stimulated cells (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Exogenous TNF-α and IL-1β reverse inhibition by neutralization antibodies. P388D1 cells were pre-incubated with 10 µg/ml anti-TNF-α mAb and 20 µg/ml anti-IL-1βmAb, or 30 µg/ml control IgG for 30 min followed by addition of medium, 1 µg/ml LPS, or 1 ng/ml TNF-α and 16 pg/ml IL-1β. After 12 h, medium, or 1 ng/ml TNF-α and 16 pg/ml IL-1β was added to cultures, and cells were harvested after an additional 12 h. The indicated cathepsin activities in live cells were measured as in Fig. 2. Values are mean ± SE from four separate experiments. Reversal cultures contained anti-TNF-α and anti-IL-1β mAb, LPS, TNF-α and IL-1β.

3.6. IFN-β contributes to cathepsin upregulation during Poly I:C response

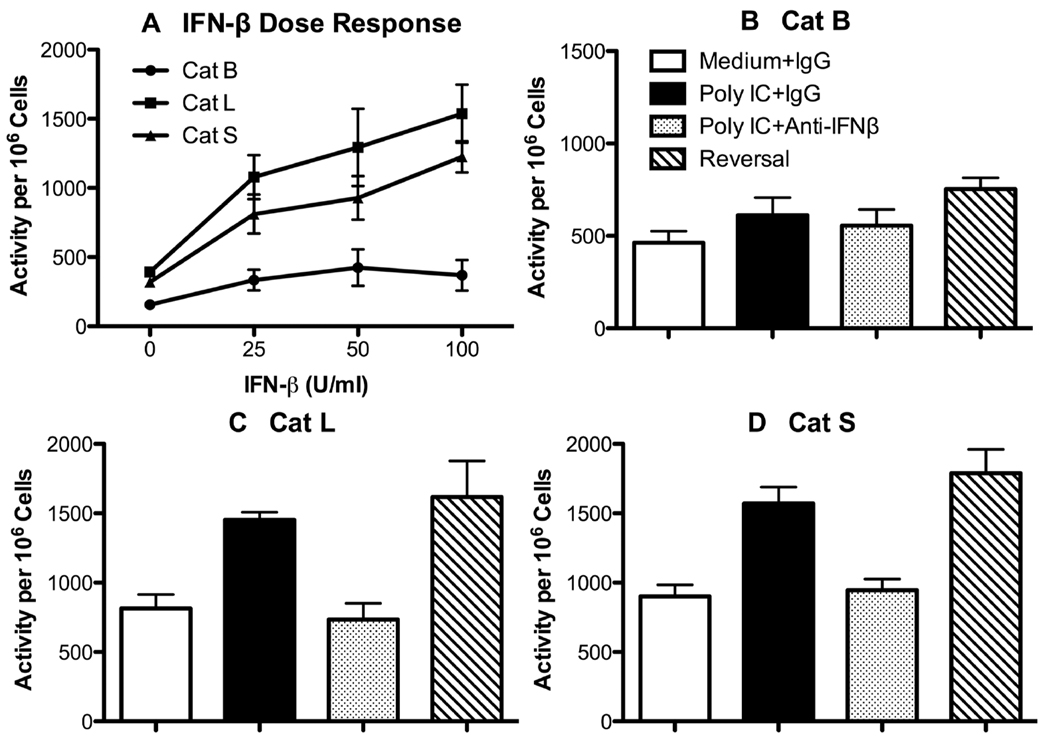

Poly I:C induces vigorous IFN-β secretion, whereas LPS is noted for quick and robust production of TNF-αand IL-1β. Cat L and S activities significantly increased in macrophages in response to Poly I:C (see Figs. 2 and 5), suggesting a potential role for IFN-β in regulating cathepsins. When P388D1 cells were incubated with recombinant IFN-β, Cat L and S activities significantly increased in the cells (p < 0.006), whereas the slight elevation of Cat B activity was not significant (Fig. 10A). IFN-β at 10 U/ml was not stimulatory (data not shown). To investigate the possible IFN-β effect during the Poly I:C response, another approach was utilized, because EOC 20 cells were responsive to Poly I:C. P388D1 macrophages were pre-incubated with neutralizing anti-IFN-β mAb or control IgG before a 24 h-stimulation with Poly I:C. Cat B activity was not significantly upregulated in Poly I:C-stimulated cells (Fig. 10B), which agrees with the preceding results (see Figs. 2 and 5). Neutralization of IFN-β had little effect on Cat B activity (Fig. 10B). In contrast, Poly I:C significantly augmented Cat L and S activities (p < 0.004) as before, and their activities were reduced to medium control levels with anti-IFN-β mAb (Figs. 10C and D). In initial experiments, 100 U/ml exogenous IFN-β did not counteract the neutralizing effect of anti-IFN-β mAb (data not shown). However, 250 U/ml IFN-β added at the 12-h time point completely reversed inhibition of Cat L and S activities by anti-IFN-βmAb (Figs. 10C and D) and marginally increased Cat B activity (Fig. 10B).

Fig. 10.

IFN-β increases cathepsin L and S activities. (A) P388D1 cells were incubated with medium, or various concentrations of recombinant mouse IFN-β for 24 h, and cathepsin activities were measured as in Fig. 2. Data are mean ± SE from three separate experiments. (B – D) P388D1 cells were pre-incubated with 10 µg/ml anti-IFN-β mAb or hamster IgG for 30 min followed by addition of 10 µg/ml Poly I:C or medium. After 12 h, 250 U/ml IFN-β or medium was added to cultures. After another 12 h, cells were harvested, and the indicated cathepsin activities were measured in live cells as in Fig. 2. Values are mean ± SE from three or more separate experiments. Reversal cultures contained anti-IFN-β mAb, Poly I:C, and IFN-β.

4. Discussion

This study is one of the first to examine the impact of TLR ligands on cysteine cathepsins in macrophages. LPS activation of dendritic cells alters the intracellular localization of active proteases within phagosomal and endosomal compartments [21,22], however, these studies did not examine whether LPS affects cathepsin activity or expression. In addition, LPS increases Cat S expression in cervical smooth muscle cells [23]. In the present study, LPS significantly increased Cat B, L and S activities by 2- to 4-fold in multiple murine macrophage cell lines and a human monocyte cell line. Enhanced cathepsin activities in peritoneal cell also occurred after in vivo LPS exposure, indicating that upregulated cathepsin activities are an integral part of the myeloid cell LPS response. Primary BMDM had augmented Cat L activity in response to 100-fold lower LPS dose, suggesting that primary cells are more sensitive to LPS than cell lines. However, changes in cathepsin transcript levels were not observed. In a similar manner, PGN, a TLR2 ligand, and Poly I:C, a TLR3 ligand, also enhanced proteolytic activity of Cat L and S, and the degree of augmentation was comparable to that induced by LPS activation. Cat B activity consistently had the lowest degree of enhancement, and, in fact, did not significantly increase after Poly I:C stimulation. A TLR subgroup, including TLR3, TLR7 and TLR9, resides within endosomal/lysosomal membranes, and acidification of these organelles is essential for cell activation through these receptors [24]. In particular, TLR9 requires cleavage by cysteine cathepsins for proper signal transduction, indicating a link between TLR activation and cathepsins [25,26]. Our results support a link between TLR signals and cathepsin upregulation in a differential manner. Activation of either MyD88-dependent or -independent pathways lead to increased Cat L and S activities, while only MyD88-dependent pathways enhanced Cat B activity.

LPS and PGN induce rapid TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 production, although lower levels are observed with TLR2 ligands [1,5,27,28]. Previous studies indicate cytokines regulate cysteine cathepsins in a cell type-dependent manner [23,29–33]. IFN-γ upregulates cathepsins in macrophages [29,30], but the effect of other cytokines on these proteases has not been investigated in macrophages. Recombinant IL-6 increases Cat S activity in dendritic cells in a STAT-3-dependent manor [31], and Cat B release in osteoblasts [32]. Cat S expression that is increased in LPS-stimulated human cervical smooth muscle cells is partially inhibited with neutralizing anti-TNF-α Ab [23]. Recombinant TNF-α and IL-1β increases activity of Cat B and S, but not L, in human dendritic cells [33]. However, anti-IL-1β Ab does not inhibit upregulation of Cat S mRNA in cervical smooth muscle cells [23]. Early cytokine response played a significant role in regulating cathepsins, when we examined the effects of culture supernatants from LPS-stimulated P388D1 cells on cathepsin activity in LPS non-responsive EOC 20 cells. Culture supernatants from 6-h LPS-stimulated macrophages increased cathepsin activities in LPS non-responsive macrophages, which was not observed when supernatants were collected from 24-h LPS cultures. These cytokines were most likely consumed by P388D1 cells in an autocrine manner by 24 h. In agreement, numerous studies have shown that mRNA levels of these cytokines are maximal at 4 to 6 h after stimulation, and cytokine concentrations in culture supernatants are highest from 6 to 12 h and decrease by 24 h [2–4,34]. The culture supernatants contained an extremely low level of active cathepsins, and, hence, increased cathepsin activities in bystander EOC 20 cells cannot be attributed to carry over of proteases into the EOC 20 cell cultures. Medium control culture supernatants did not boost cathepsin activities in EOC 20 cells arguing against spontaneous cytokine secretion by P388D1 cells. Neutralization of TNF-α and IL-1β had different effects on Cat B, L and S. Anti-TNF-α or anti-IL-1β mAb alone decreased Cat L and S activities. However, activity levels of Cat L and S were completely reduced to medium control values when both cytokines were neutralized, which displayed an additive effect. In addition, recombinant TNF-α or IL-1β alone enhanced Cat L and S activities in a dose-dependent manner in the absence of LPS. Furthermore, these cytokines, when added at 12 h of culture, completely reversed the inhibitory effect of neutralizing mAb on Cat L and S activities in LPS-stimulated cells. Hence, Cat L and S appear to be regulated by both TNF-α and IL-1β. On the other hand, increased Cat B activity was dramatically inhibited when TNF-α alone was neutralized in transferred LPS culture supernatants. Recombinant TNF-α or IL-1β alone augmented Cat B activity to a lower extent compared with Cat L and S activities. These cytokines also counteracted the impact of neutralizing anti-TNF-α and anti-IL-1β mAb on Cat B activity. Although the culture supernatants should contain other cytokines, TNF-α and IL-1β were the primary regulators of these cathepsins in macrophages, and other cytokines did not compensate when TNF-α and/or IL-1β were neutralized. Therefore, changes in cathepsin activities were apparently not due to direct LPS signaling but were, instead, controlled by cytokines produced during the LPS response.

Our original prediction was that cathepsin upregulation would be MyD88-dependent because of vigorous pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Poly I:C, which tranduces a MyD88-independent signal, induces a low level of pro-inflammatory cytokine production in comparison with LPS, but causes robust IFN-β secretion [1,5,27,28]. Unexpectedly, Cat L and S activities in P388D1 cells substantially increased in response to Poly I:C. This finding suggested IFN-β might play an important role in regulating these proteases and possibly compensate for the low TNF-α and IL-1β levels in response to Poly I:C. Recombinant IFN-β alone enhanced Cat L and S activities in a dose-dependent manner. Neutralization of IFN-β significantly reduced increased Cat L and S activities during Poly I:C stimulation to medium control levels. Importantly, exogenous IFN-β completely restored upregulated Cat L and S activities in the presence of the neutralizing mAb. On the other hand, recombinant IFN-β had little impact on Cat B activity. Neutralizing IFN-β had no effect on Cat B activity, correlating with the lack of significant Cat B upregulation during the Poly I:C response. Unlike Cat B activity that was IFN-β-independent, IFN-βwas a major regulator of Cat L and S activities during the Poly I:C response in macrophages.

Cathepsin activity is regulated on multiple levels [13,35]. Hence, altered cathepsin activity and mRNA expression do not necessarily correlate [36]. The significant increase in cathepsin activity in LPS-stimulated cells occurred in the absence of increased cathepsin mRNA expression at both time points examined. Cystatins are endogenous inhibitors of cysteine cathepsins, and are often inversely affected during inflammatory diseases [37,38]. Cystatin C mRNA did not significantly decrease at the 24-h time point. This finding suggests downregulation of cystatin C mRNA expression was not a factor in increased cathepsin activities during the LPS response in macrophages. The role of cystatin C in regulating cathepsins is unclear. Studies suggest cystatin C is an important regulator of Cat S activity and trafficking of MHC class II molecules in dendritic cells [31,39,40], whereas another study reported cystatin C expression and distribution is not altered in LPS-stimulated dendritic cells [22]. Other studies indicate cystatin C is not localized to endosomes and lysosomes, and does not regulate antigen presentation [41,42]. Likewise, the intracellular inhibitor cystatin B mRNA was not altered, suggesting it might not regulate these proteases during LPS stimulation. Active cathepsins were present in acidic vesicles based on their cleavage product co-localizing with an acidotrophic probe. In agreement with the flow cytometric and spectrofluorophotometric assays, the ImageStream®analyses also measured increased product formation within acidic vesicles inside LPS-stimulated cells. Interestingly, the MFI of the acidotropic probe was also increased in LPS-stimulated cells suggesting that the acidic compartments themselves were impacted. Fluorescence of the probe is pH insensitive, and, thus, increased MFI does not reflect a lower pH within the vesicles. LPS alters the endosomal/lysosomal location of these proteases and enhances vesicular acidification in dendritic cells [22,43]. Recruitment of cathepsins to more acidic endocytic compartments promotes enzyme activation [13]. LPS also drives endolysosomal tubule formation, increasing the overall size of acidic compartments [44,45]. Therefore, LPS may induce changes in acidity and size of the endocytic compartments leading to increased cathepsin activities.

This study is the first one to indicate that IFN-β regulates cysteine cathepsins. IFN-β might affect cathepsins by a different mechanism than TNF-α and IL-1β. Poly I:C response might alter cathepsin transcript levels unlike the LPS response. Interferon response factor-1 regulates Cat S gene expression through an interferon stimulated response element (ISRE) in the Cat S promoter [46]. However, an ISRE has not been identified in the promoter region of Cat L [46]. The robust IFN-β production that occurs with Poly I:C may increase mRNA levels of Cat L and S via other transcription factors, which was not investigated here. Alternatively, IFN-β induces secretion of other cytokines [47,48], and the later cytokines may cause enhanced Cat L and S activities. Possibly, neutralization of IFN-β inhibited induction of other inflammatory cytokines, which increase cathepsin activities. Additional experiments are needed to distinguish between these possibilities.

Altogether, our studies show TLR signals positively regulated cathepsin activities involving both MyD88-dependent and –independent pathways. Steady-state mRNA expression of cathepsins and their endogenous inhibitors, cystatins, did not significantly alter in LPS-stimulated cells. Increased fluorescence intensity of the pH-insensitive acidotropic probe in LPS-stimulated cells suggests that the nature of acidic compartments changed resulting in enhanced cathepsin activities. The effects of TLR signaling on the cysteine cathepsins examined could be attributed to an indirect cytokine-mediated mechanism. These proteases are important in initiating adaptive immune responses by their involvement in antigen processing, which is critical for CD4+ T cell antigen responses, but cathepsins also participate in inflammation and tissue destruction. Disruption in the balance of their regulated activity may underlie the pathological changes that involve cathepsins.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by P50DA05275 and R01ES07199 grants from the National Institutes of Health, the A.D. Williams Trust Fund and the VCU Department of Microbiology and Immunology. B.M. Creasy was supported by T32AI07407 from the Department of Health and Human Services. We especially thank Dr. Phil Morrissey and Jeff Hudson (Amnis Corporation) and the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at University of Virginia for assistance with the ImageStream® System; Dr. Howard Young (National Institutes of Health) for providing the bone marrow macrophage cell line; and Immunochemistry Technologies, LLC for providing the MR-conjugated cathepsin substrates.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Trinchieri G, Sher A. Cooperation of Toll-like receptor signals in innate immune defense. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:179–190. doi: 10.1038/nri2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones BW, Heldwein KA, Means TK, Saukkonen JJ, Fenton MJ. Differential roles of Toll-like receptors in the elicitation of proinflammatory responses by macrophages. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2001;60 Suppl. 3:iii6–iii12. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.90003.iii6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones BW, Means TK, Heldwein KA, Keen MA, Hill PJ, Belisle JT, Fenton MJ. Different Toll-like receptor agonists induce distinct macrophage responses. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2001;69:1036–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirschfeld M, Weis JJ, Toshchakov V, Salkowski CA, Cody MJ, Ward DC, Qureshi N, Michalek SM, Vogel SN. Signaling by toll-like receptor 2 and 4 agonists results in differential gene expression in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:1477–1482. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1477-1482.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjorkbacka H, Fitzgerald KA, Huet F, Li X, Gregory JA, Lee MA, Ordija CM, Dowley NE, Golenbock DT, Freeman MW. The induction of macrophage gene expression by LPS predominantly utilizes MyD88-independent signaling cascades. Physiol. Genomics. 2004;19:319–330. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00128.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeda K, Akira S. TLR signaling pathways. Semin. Immunol. 2004;16:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karin M, Lawrence T, Nizet V. Innate immunity gone awry: linking microbial infections to chronic inflammation and cancer. Cell. 2006;124:823–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gribar SC, Anand RJ, Sodhi CP, Hackam DJ. The role of epithelial Toll-like receptor signaling in the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;83:493–498. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tobias PS, Curtiss LK. Toll-like receptors in atherosclerosis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007;35:1453–1455. doi: 10.1042/BST0351453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Q, Ma Y, Adebayo A, Pope RM. Increased macrophage activation mediated through toll-like receptors in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;5:2192–2201. doi: 10.1002/art.22707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang B, Zhao J, Unkeless JC, Feng ZH, Xiong H. TLR signaling by tumor and immune cells: a double-edged sword. Oncogene. 2008;27:218–224. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berdowska I. Cysteine proteases as disease markers. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2004;342:41–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honey K, Rudensky AY. Lysosomal cysteine proteases regulate antigen presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:472–482. doi: 10.1038/nri1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joyce JA, Baruch A, Chehade K, Meyer-Morse N, Giraudo E, Tsai FY, Greenbaum DC, Hager JH, Bogyo M, Hanahan D. Cathepsin cysteine proteases are effectors of invasive growth and angiogenesis during multistage tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:443–453. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gocheva V, Zeng W, Ke D, Klimstra D, Reinheckel T, Peters C, Hanahan D, Joyce JA. Distinct roles for cysteine cathepsin genes in multistage tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:543–556. doi: 10.1101/gad.1407406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray P, Wang L, Onufryk C, Tepper R, Young R. T cell-derived IL-10 antagonizes macrophage function in mycobacterial infection. J. Immunol. 1997;158:315–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creasy BM, Hartmann CB, Higgins White FK, McCoy KL. New assay using fluorogenic substrates and immunofluorescence staining to measure cysteine cathepsin activity in live cell subpopulations. Cytometry Part A. 2007;71:114–123. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beum PV, Lindorfer MA, Hall BE, George TC, Frost K, Morrissey PJ, Taylor RP. Quantitative analysis of protein co-localization on B cells opsonized with rituximab and complement using the ImageStream multispectral imaging flow cytometer. J. Immunol. Methods. 2006;317:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison MT, Hartmann CB, McCoy KL. Impact of in vitro gallium arsenide exposure on macrophages. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2003;186:18–27. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(02)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeuchi O, Takeda K, Hoshino K, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Akira S. Cellular responses to bacterial cell wall components are mediated through MyD88-dependent signaling cascades. Int. Immunol. 2000;12:113–117. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lennon-Dumenil AM, Bakker AH, Maehr R, Fiebiger E, Overkleeft HS, Rosemblatt M, Ploegh HL, Lagaudriere-Gesbert C. Analysis of protease activity in live antigen-presenting cells shows regulation of the phagosomal proteolytic contents during dendritic cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:529–540. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lautwein A, Burster T, Lennon-Dumenil AM, Overkleeft HS, Weber E, Kalbacher H, Driessen C. Inflammatory stimuli recruit cathepsin activity to late endosomal compartments in human dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:3348–3357. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200212)32:12<3348::AID-IMMU3348>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watari M, Watari H, Nachamkin I, Strauss JF. Lipopolysaccharide induces expression of genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines and the elastin-degrading enzyme, cathepsin S, in human cervical smooth-muscle cells. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2000;7:190–198. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(00)00054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trivedi S, Greidinger EL. Endosomal Toll-like receptors in autoimmunity: mechanisms for clinical diversity. Therapy. 2009;6:433–442. doi: 10.2217/thy.09.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto F, Saitoh S, Fukui R, Kobayashi T, Tanimura N, Konno K, Kusumoto Y, Akashi-Takamura S, Miyake K. Cathepsins are required for Toll-like receptor 9 responses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;367:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park B, Brinkmann MM, Spooner E, Lee CC, Kim Y-M, Ploegh HL. Proteolytic cleavage in an endolysosomal compartment is required for Toll-like receptor 9 activation. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:1407–1414. doi: 10.1038/ni.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Neill LA. Toll-like receptor signal transduction and the tailoring of innate immunity: a role for Mal? Trends Immunol. 2002;23:296–300. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Neill LA. How Toll-like receptors signal: what we know and what we don’t know. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2006;18:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lemaire R, Huet G, Zerimech F, Grard G, Fontaine C, Duquesnoy B, Flipo RM. Selective induction of the secretion of cathepsins B and L by cytokines in synovial fibroblast-like cells. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1997;36:735–743. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.7.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lah TT, Hawley M, Rock RL, Goldberg AL. Gamma-interferon causes a selective induction of the lysosomal proteases, cathepsins B and L, in macrophages. FEBS Lett. 1995;363:85–89. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00287-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitamura H, Kamon H, Sawa S, Park SJ, Katunuma N, Ishihara K, Murakami M, Hirano T. IL-6-STAT3 controls intracellular MHC class II alphabeta dimer level through cathepsin S activity in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2005;23:491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chae HJ, Ha KC, Lee GY, Yang SK, Yun KJ, Kim EC, Kim SH, Chae SW, Kim HR. Interleukin-6 and cyclic AMP stimulate release of cathepsin B in human osteoblasts, Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2007;29:155–172. doi: 10.1080/08923970701511579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiebiger E, Meraner P, Weber E, Fang IF, Stingl G, Ploegh H, Maurer D. Cytokines regulate proteolysis in major histocompatibility complex class II-dependent antigen presentation by dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:881–892. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zughaier S, Zimmer S, Datta A, Carlson R, Stephens D. Differential induction of the Toll-like receptor 4-MyD88-dependent and -independent signaling pathways by endotoxins. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:2940–2950. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2940-2950.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Honey K, Duff M, Beers C, Brissette WH, Elliott EA, Peters C, Maric M, Cresswell P, Rudensky A. Cathepsin S regulates the expression of cathepsin L and the turnover of gamma-interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase in B lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:22573–22578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keyszer G, Redlich A, Haupl T, Zacher J, Sparmann M, Engethum U, Gay S, Burmester GR. Differential expression of cathepsins B and L compared with matrix metalloproteinases and their respective inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: a parallel investigation by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1378–1387. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199808)41:8<1378::AID-ART6>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Sukhova GK, Sun JS, Xu WH, Libby P, Shi GP. Lysosomal cysteine proteases in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:1359–1366. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000134530.27208.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kopitar-Jerala N. The role of cystatins in cells of the immune system. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6295–6301. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boes M, van der Wel N, Peperzak V, Kim YM, Peters PJ, Ploegh H. In vivo control of endosomal architecture by class II-associated invariant chain and cathepsin S. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005;35:2552–2562. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pierre P, Mellman I. Developmental regulation of invariant chain proteolysis controls MHC class II trafficking in mouse dendritic cells. Cell. 1998;93:1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zavasnik-Bergant T, Repnik U, Schweiger A, Romih R, Jeras M, Turk V, Kos J. Differentiation- and maturation-dependent content, localization, and secretion of cystatin C in human dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005;78:122–134. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0804451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El Sukkari D, Wilson NS, Hakansson K, Steptoe RJ, Grubb A, Shortman K, Villadangos JA. The protease inhibitor cystatin C is differentially expressed among dendritic cell populations, but does not control antigen presentation. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5003–5011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trombetta ES, Ebersold M, Garrett W, Pypaert M, Mellman I. Activation of lysosomal function during dendritic cell maturation. Science. 2003;299:1400–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.1080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vyas JM, Kim Y-M, Artavanis-Tsakona K, Love CJ, Van der Veen AG, Ploegh H. Tubulation of class II MHC compartments is microtubule dependent and involves multiple endolysosomal membrane proteins in primary dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2007;178:7199–7210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleijmeer M, Ramm G, Schuurhuis D, Griffith J, Rescigno M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Rudensky AY, Ossendorp F, Melief CJ, Stoorvogel W, Geuze HJ. Reorganization of multivesicular bodies regulates MHC class II antigen presentation by dendritic cells. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:53–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Storm van’s Gravesande K, Layne MD, Ye Q, Le L, Baron RM, Perrella MA, Santambrogio L, Silverman ES, Riese RJ. IFN regulatory factor-1 regulates IFN-gamma-dependent cathepsin S expression. J. Immunol. 2002;168:4488–4494. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Remoli ME, Gafa V, Giacomini E, Severa M, Lande R, Coccia EM. IFN-β modulates the response to TLR stimulation in human DC: Involvement of IFN regulatory factor-1(IRF-1) in IL-27 gene expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:3499–3508. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Theofilopoulos AN, Baccala R, Beutler B, Kono DH. Type I interferons (α/β) in immunity and autoimmunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:307–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]