Abstract

Aim

This paper is a report of a study conducted to characterize the stigma of urinary frequency and urgency and differentiate it from the stigma of incontinence and to describe race/ethnic and gender differences in the experience of stigma among a diverse sample of individuals.

Background

Lower urinary tract symptoms, including frequency, urgency and incontinence, are susceptible to stigma, but previous stigma research has focused almost exclusively on incontinence.

Method

The Boston Area Community Health Survey is a population-based, random sample epidemiological survey of urologic symptoms (N=5503). Qualitative data for this study came from in-depth interviews conducted between 2007 and 2008 with a random subsample of 151 black, white and Hispanic men and women with urinary symptoms.

Findings

Respondents reported stigma associated with frequency and urgency – not just incontinence. The stigma of frequency/urgency is rooted in social interruption, loss of control of the body, and speculation as to the nature of a non-specific “problem.” Overall, the stigma of urinary symptoms hinged upon whether or not the problem was “perceptible.” Men felt stigmatized for making frequent trips to the bathroom and feared being seen as impotent. Women feared having an unclean body or compromised social identity. Hispanic people in particular voiced a desire to keep their urinary symptoms a secret.

Conclusion

The stigma of urinary symptoms goes beyond incontinence to include behaviors associated with frequency and urgency. Healthcare practitioners should assess for stigma sequelae (e.g. anxiety, depression) in individuals with frequency and urgency, and stress treatment options to circumvent stigmatization.

Keywords: Nursing, healthcare professionals, stigma, public health, urinary incontinence, urinary symptoms

INTRODUCTION

Previous research on the stigmatization of individuals with urinary symptoms has focused almost exclusively on the experience of urinary incontinence (UI) (Brittain and Shaw 2007, Chiverton et al. 1996, Garcia et al. 2005, Mitteness and Barker 1995, Paterson 2000), while relatively little attention has been paid to the personal and social consequences of other lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). LUTS are a constellation of symptoms that include daytime frequency, urgency, nocturia and incontinence (Abrams et al. 2003). LUTS commonly co-occur (Barry et al. 2008, Coyne et al. 2008), and UI is often accompanied by additional urological symptoms, although clusters of other LUTS without UI are also common (Cinar et al. 2008, Hall et al. 2008).

There is reason to believe that urinary frequency and urgency are their own source of stigma, distinct from incontinence. Recent research has shown these symptoms to be linked to anxiety, depression (Coyne et al. 2009), fear of incontinence and hopelessness (Nicolson et al. 2008), suggesting that frequency and urgency affect people on personal, inter-personal and/or social — not just physical — levels. Further, urinary frequency and urgency cause individuals to make frequent trips to the bathroom in the presence of others, drawing attention to private body parts (Crandall and Moriarty 1995) and the act of urination, which is socially expected to occur in a private space (Mitteness and Barker 1995). Even in the absence of UI, LUTS may give rise to behaviors that are potentially stigmatizing.

BACKGROUND

Conceptually, Goffman’s well-known work on stigma (Goffman 1963) defines a stigmatized person as one who possesses “an attribute that makes him different from others...and of a less desirable kind” (p.3). Goffman’s work has inspired a profusion of research focused on the nature, sources, and consequences of stigma (Link and Phelan 2006). From a public health perspective, stigma is of special concern; it is associated with worsened health outcomes (Schwartzmann 2009, Taft et al. 2009) and is thought to be a general risk factor for disease by creating stressful circumstances and then compromising a person’s ability to cope with these circumstances (Link and Phelan 2006). Stigma is also linked to reduced self-esteem and depression (Link 1987, Markowitz 1998), anxiety (Markowitz 1998), quality of life (QOL) (Devinsky et al. 1999, Holzemer et al. 2009) and discrimination (Phelan et al. 2008). Further, stigmatized individuals experience “reduced life chances” (Goffman 1963) such as decreased employment and housing opportunities, and medical care (Link and Phelan 2006).

The stigma of UI has been explored from a number of important angles which inform this paper. First, Mitteness and Barker’s (1995) work establishes the linkage of UI with incompetence and aging, highlighting the importance of control and self-restraint to notions of adulthood in Western society. Incontinence confounds expectations of bodily control and notions of appropriate comportment, where the act of urination is expected to take place in a private space (not in public as in the case of visible leakage), and where “accidents” are expected to be managed such that they are invisible to others. The social consequences of failure to conceal leakage are pronounced and include strained relationships and social isolation (Mitteness and Barker 1995). Indeed, the notion of visibility is a linchpin in the discourse on stigma with respect to its role in producing negative social reactions (Jones et al. 1984). Joachim and Acorn provide a framework for distinguishing the stigma of visible and invisible chronic illnesses (e.g. paraplegia versus diabetes), although some conditions — like — LUTS have the capacity to be both visible and concealed (Joachim and Acorn 2000).

Existing research on differences in stigma attitudes and experience by race/ethnicity leads us to hypothesize that such differences may extend to stigma associated with urinary symptoms. For example, black and Hispanic people may be more likely to perceive themselves to be stigmatized (Mulia et al. 2009), and members of racial minority groups may be more reluctant to seek help for stigmatizing medical conditions (Anglin et al. 2006, Lichtenstein et al. 2005). From another perspective, African Americans may hold more stigmatizing attitudes towards individuals with mental illness than white and Hispanic people (Anglin et al. 2006, Rao et al. 2007, Whaley 1997), which may have a negative impact on their own likelihood of seeking treatment for mental illness (Sanders Thompson et al. 2004).

The stigma literature has not, to our knowledge, characterized the stigma of urinary frequency and urgency or differentiated it from the stigma of UI. Further, studies conducted in the U.S.A. and Scotland examining LUTS from a qualitative perspective have sampled only men and have been largely racially and ethnically homogeneous (Cunningham-Burley et al. 1996, Gannon et al. 2004). In a departure from the prevailing focus on UI in the stigma literature, in the study reported here we focused on “other” urinary symptoms in order to determine whether and how men and women of different racial/ethnic backgrounds with frequency and urgency are stigmatized. This study provides the basis for a new and more comprehensive conceptualization of the stigma of LUTS and implications for healthcare practitioners around stigma detection and prevention.

THE STUDY

Aims

The aims of this study were 1) to characterize the stigma of daytime frequency and urgency and differentiate it from the stigma of UI, and 2) to describe race/ethnic and gender differences in the experience of stigma among a diverse sample of individuals with LUTS.

Methodology

An inductive approach with qualitative methods was used. Data collection and analysis were guided by grounded theory, as this method allows for a systematic but inductive approach to understanding stigma perceptions in a social context (Strauss and Corbin 1990). The data were collected between 2007 and 2008.

Participants

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey is the “parent” study to this qualitative study and is a population-based, random sample epidemiological survey (n=5503) of a broad range of urological symptoms. A multi-stage, stratified cluster sample design was used to obtain approximately equal numbers of black, Hispanic and white men and women aged 30–79 years. Participants included 3202 women and 2301 men: 1767 black, 1877 Hispanic, and 1859 white people. The sampling design and study methods (McKinlay and Link 2007) and the prevalence and correlates of urological symptoms (Fitzgerald et al. 2007, Tennstedt et al. 2008) have been previously reported.

The qualitative study consisted of focus groups and in-depth interviews. Participants for focus groups and interviews were randomly sampled from each of the six subgroups of the BACH sample, and included individuals who reported one or more LUTS on the survey. Fifty-eight respondents participated in a total of eight focus groups. In-depth interviews were conducted with an additional 151 respondents, randomly sampling approximately equal numbers (~25) in each of the six subgroups (black, white, and Hispanic men and women) in order to achieve thematic saturation across each group.

Data collection

Focus groups

Eight focus groups were conducted to explore the experience of urinary symptoms in a social context, in order to generate themes based on the interactions of individuals with each other. The primary purpose of the focus groups was to inform the development of the in-depth interview guide. Focus groups were stratified by gender and ethnic group, and moderators were matched to each group. Separate focus groups were conducted in English and Spanish for Hispanic participants, based on language preference. Focus groups ran for approximately 90 minutes.

In-depth interviews

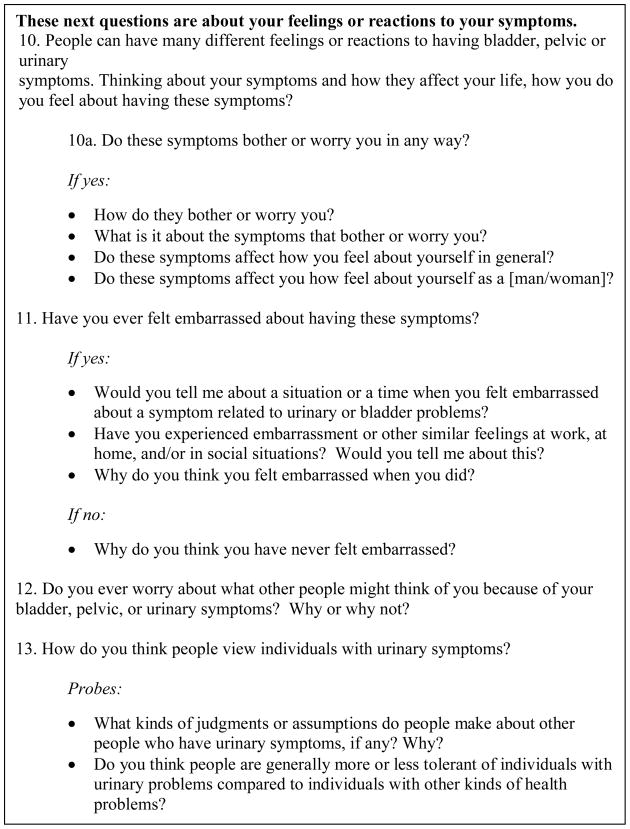

An interview guide was developed and then refined through the use of the focus groups. The final interview guide posed questions related to respondents’ own experiences of having urinary symptoms, as well as their impressions of what other people think of individuals with urinary symptoms, and asked them to 1) speculate on how they might feel in certain situations; 2) provide their perception of how others view them; and, 3) discuss their own opinions about others who experience various urinary symptoms. The section of the interview guide pertaining to stigma is displayed in Figure 1. This mode of questioning allowed us to glean respondents’ perspectives from a number of different angles. In-depth interviews were conducted by trained interviewers in participants’ homes. The length of the interview was approximately 60 minutes.

Figure 1.

Section of interview discussion guide pertaining to stigma of urinary symptoms

Both interviews and focus groups were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Spanish interviews and focus groups were translated into English.

Ethical considerations

Both the parent study (BACH) and qualitative sub-study were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Board.

Data analysis

Criteria for inclusion in this analysis included reporting of urinary frequency, urgency, and/or UI symptoms (see Table 1). Data from the in-depth interviews only were analyzed for this paper. An inductive approach, consistent with Strauss and Corbin’s approach for creating theory grounded in the data (Strauss 1987) was used in our analysis. Our methods stressed learning from respondents through the use of open-ended interviewing techniques and a constant comparative method (Morse and Richards 2002). Thus, transcripts were read by two of the researchers (EE and EB) to generate a “start list” of codes, a process that Strauss and Corbin refer to as “open coding” (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Transcripts were read a second time to refine the coding structure and explicit definitions were stored in a code book. Transcripts were then coded using Atlas.ti software (Muhr 2004). Finally, patterns across transcripts were examined and emergent themes were compared across gender and ethnic/racial groups. Respondents’ perceptions of being stigmatized by others (hereafter referred to as “stigma perceptions” for the sake of brevity) were derived inductively, based on emergent themes from the data.

Table 1.

Assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in this study

Frequency 1: At least one of the following reported :

|

Urgency1: At least one of the following reported to occur “fairly often,” “usually,” or “almost always”:

|

Urine leakage2: Experiencing the following at least weekly (“one or more times per week” or “every day”)

|

Although the sample included individuals with the storage symptom of nocturia, themes related to nocturia were not included in our analysis as this symptom was not hypothesized to be stigmatizing, due to the lack of social context involved in night-time frequency.

Rigour

Two authors (EE and EB) were involved in coding and met regularly throughout the study (every two weeks) to discuss emergent themes, appropriateness of interview guide questions, and data saturation. Double coding was conducted on a sample of focus group transcripts in order to discuss discrepancies and refine the coding structure. Interpretation of the data was discussed in regular meetings by all authors.

FINDINGS

Study participants ranged in age from 31 to 80 years and consisted of 77 (26 white, 26 black and 25 Hispanic) men and 75 women (25 in each race/ethnic group). The analysis reported here was limited to those respondents who reported urinary frequency, urgency and/or incontinence symptoms (n=118). Table 2 displays the self-reported burden of urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence by gender and race/ethnic group. Below we describe the stigma of frequency and urgency as compared to the stigma of UI, and then address racial/ethnic and gender differences in stigma perceptions associated with these symptoms.

Table 2.

Self-reported burden of urinary incontinence, frequency, and urgency by race/ethnic and gender group

| Any frequency | Any urgency | Any urinary incontinence | Urinary incontinence only | Urinary incontinence plus frequency and/or urgency | Frequency and/or urgency (No urinary incontinence) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total* (N=118) | 95 (81%) | 51 (43%) | 38 (32%) | 8 (7%) | 33 (28%) | 77 (65%) |

| Black Males (n=20) | 19 (95%) | 7 (35%) | 4 (20%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (15%) | 16 (80%) |

| White Males (n=20) | 18 (90%) | 7 (35%) | 2 (10%) | 0 | 2 (10%) | 18 (90%) |

| Hispanic Males (n=17) | 15 (88%) | 15 (88%) | 2 (12%) | 0 | 2 (12%) | 15 (88%) |

| Black Females (n=19) | 14 (74%) | 2 (11%) | 8 (42%) | 2 (11%) | 8 (42%) | 9 (47%) |

| White Females (n=20) | 16 (80%) | 10 (50%) | 10 (50%) | 2 (10%) | 8 (40%) | 10 (50%) |

| Hispanic Females (n=22) | 13 (59%) | 10 (45%) | 12 (55%) | 3 (14%) | 10 (45%) | 9 (41%) |

The total number of respondents in this study was 151; however, our analysis included only those who reported urinary incontinence, frequency and/or urgency (n=118).

Stigma of daytime frequency and urgency

Respondents reported stigma associated with urinary frequency and urgency, not just UI. In particular, they reported feelings of embarrassment and shame associated with having to make frequent trips to the bathroom when in the company of others, as illustrated by the following examples:

If I go to someone’s house and I have to go to the bathroom a lot, maybe it might not be the right time to go to the bathroom to pee, but since I have this weakness in my bladder, I have to go right away... I worry because I think other people are going to think ‘what’s wrong with her? Why is she going to the bathroom so much?’... It’s truly not normal for someone to need to go to the bathroom so much! (Hispanic woman)

Imagine if someone goes to the bathroom at another person’s house three, four, or five times, what are people going to think? ...they must think ‘what’s wrong with that guy?’ (Hispanic man)

As a result of their frequency/urgency symptoms, respondents felt compelled to behave in ways that made them stand out as different. These behaviors, by repeatedly making a private act public, were perceived to be socially risky in that they signalled a furtive and nonspecific problem and made respondents feel that others were suspicious of them.

Some respondents substantiated their fear of stigmatization with stories of others treating them differently as a result of their behavior. For example, one woman recalled other people’s responses to her frequent trips to the bathroom:

If I’m with other people...they say, ‘Oh my god, you have to go to the bathroom again? We have to keep looking for a bathroom for this woman! Pisser! That woman has to pee a lot.’ (Hispanic woman)

Stigma perceptions for frequency and urgency symptoms often indicated anxieties about the potential for leakage; however, we found the stigma of frequency and urgency to be rooted in social interruption, loss of socially-expected control of the body, speculation as to the nature of a non-specific “problem,” and the undesirable mixing of private behavior in a public space.

Stigma of daytime urinary frequency and urgency vs. the stigma of UI

Jones and colleagues (1984) note that a person with a stigmatizing health condition may or may not be stigmatized; a person only becomes stigmatized once “the deviant condition has been noticed and recognized as a problem”. In line with previous research on other chronic conditions (Joachim and Acorn 2000, Jones et al. 1984, Wilde 2003), our respondents observed that their condition was only stigmatizing when visible. Thus, the fear of stigmatization for UI is in fact a fear of visibility — “the fear not that you have contaminated yourself, but that others will notice” (Oring 1979). Respondents noted that their symptoms were largely concealable and located the nascence of stigma in the spectre of visibility:

You don’t go around wearing a sign on your back saying “I have a urinary [problem]” ... But, if it was something visible, I would think people would treat you worse... because people are judgmental, you know? (Black man)

If someone can see their problem, they may be treated differently. . . I think if people know the situation, they don’t want to be around it. (Black woman)

However, unlike other chronic conditions to which Joachim and Acorn (2000) have applied the notion of visible and invisible stigma, UI has an additional signifier: odour. As one white male respondent aptly put it, “If you have a bleeding sore, it’s a different kind of thing than somebody who has an unpleasant odour. Both of them are unpleasant. One’s to the eye. One’s to the [nose]. . . Different senses are involved.” Thusm the terms “perceptible” and “imperceptible” may more accurately describe the signifier marking an individual with UI. Comments from one respondent revealed a visceral sense of repulsion and disgust in response to the smell of urine:

There was a long period where I had to endure the odour of my mother’s incontinence when I... visited my parents. And it left a real strong impression on me, that experience. Well, this man on the elevator, it’s the same thing. I know that the man doesn’t want to spend money on (brand of adult incontinence product), you know? That’s one of the terrible things about people getting older... I hope I never get to the point where if I have to wear an apparatus for incontinence that I don’t scrimp on it. And I mean, when I’m on the elevator with this man, I just turn and I do something like this (wrinkles up nose). And he gives me this look like, how dare you? But I want this guy to get the message that he stinks, you know? (White man)

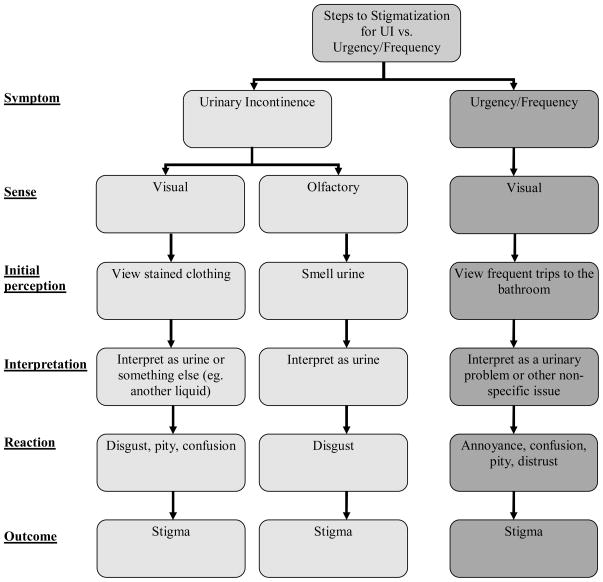

These comments illustrate that smell may be even more stigmatizing than visible urine on clothing (the marks of which must first be interpreted as urine), and that another person’s perception of symptoms signals one’s failure to manage the condition (see Figure 2). To the respondent quoted above, the smell of urine signifies unreasonable frugality and reflects a social expectation that the man in the elevator should manage his problem such that it is undetectable to others. This respondent’s harsh response to his neighbor’s seeming refusal to control the condition of his body despite an ostensible ability to do so corroborates findings by others that people with stigmas perceived to be controllable are less liked and more rejected than those with stigmas considered to be uncontrollable (Weiner et al. 1988).

Figure 2.

Stigmatization of urinary incontinence (UI) compared to frequency/urgency

The odour of urine is a strong signifier, not just that someone is incontinent, but that there is something very wrong with that person. The smell of urine portends old age, dementia, and incompetence (Mitteness and Barker 1995). While visible leakage shows the immediacy of an accident, perceptible odour signifies an accident that is removed from the immediate; urine odour develops over time, indicating that the bearer either is inured to the odour or is incapable of managing the problem (i.e. “incompetent,” as described by Mitteness and Barker). Figure 2 shows the ways in which “perceptibility” gives rise to stigmatization for frequency and urgency compared to UI. In the case of frequency or urgency, visible, frequent bathroom trips were interpreted by others as a urinary or non-specific “problem,” inciting confusion, annoyance, and/or distrust. In the case of UI, stained clothing had the potential to be interpreted as urine or as something else, such that, at this stage, the “problem” was still potentially concealable. On the other hand, the smell of urine immediately induced a disgust response and stigmatization. Inasmuch as the ability to control information about the self in general is connected to social position and self-esteem, concealing urinary symptoms so that they are not perceptible to others may be vital to being considered “normal” and avoiding stigmatization (Mitteness and Barker 1995). For frequency/urgency, concealment meant strategically planning trips to the bathroom so that they were not carried out when others would notice, or avoiding social situations altogether; in the case of UI, concealment often meant wearing a diaper or pad to prevent visible wetness, and frequently changing clothes or bathing. These findings suggest that a “hierarchy” of stigma may be in operation, whereby individuals with perceptible UI are subject to greater stigmatization than those with perceptible urinary frequency/urgency. However, the quantification of such a relationship is beyond the scope of this paper.

Gendered experiences of stigma

While both men and women feared the visibility (or “perceptibility”) of their frequency/urgency symptoms, the root of this fear varied by gender. Men in our sample were especially worried about revealing a frequent need to urinate. One white man commented that he thought a man “might get a stigma attached if [he goes] to the bathroom a lot. Males aren’t supposed to go to the bathroom a lot; females, maybe, but not males.” Some men believed that others might link behaviors associated with urinary symptoms (e.g. frequent urination or visible wetness) with infertility or impotence, as in the following example:

Oftentimes I hear my friends talk, and when they do, I stay silent because... the first thing that comes to their mind is that... any men who have this problem aren’t functioning as [men] anymore. (Hispanic Man)

Among women, UI constituted bodily pollution and was attached to notions of lack of hygiene, uncleanness, and a sense of responsibility for the condition of the body. Hispanic women in particular expressed the need to manage UI and, by extension, other people’s opinions of them:

It worries me that someone might think badly of me. . . that I don’t bathe, or that I don’t change my underwear. . . They might think that it must be a lack of hygiene or a lack of going to the doctor to get checked out. (Hispanic woman)

I believe people think, that person must not practice good hygiene... If I have to bathe twenty times, I bathe twenty times. And I change because it’s very noticeable...[Urinary problems are] something I think that people can’t stand. (Hispanic woman)

Goffman (1963), as well as Jones and colleagues (1984), have noted that it is the responsibility of a stigmatized person to manage that which is different about them, such that that thing is no longer discernable to others. Women in our study in particular commented on the social expectation that people should control their urinary symptoms:

I think the general public might be less tolerant. . . Maybe people think. . . If you’ve got these problems, why aren’t you taking care of it? (White woman)

If you have those problems, you need to take care of yourself. Because I have smelled people that walk around smelling like urine that peed on their self. And I’m like, this is disgusting. (Black woman)

In summary, for men, frequent urination and UI signalled a compromised masculine identity, while for women, these same symptoms were perceived to be a kind of bodily pollution and shirking of social/moral responsibility.

Hispanic individuals and stigma

Disproportionate to black and white respondents, Hispanic men and women reported that that they responded to worries about being stigmatized with secrecy. A number of Hispanic respondents made comments such as, “There are many things that no one knows about if you don’t tell them,” and “I think people tend to withdraw from people and not deal with it so [other people] don’t think badly of them.” One respondent offered this explanation for his secrecy:

Most people stay silent. . . because of the way of life, culture. . . the shame of having to describe yourself, and maybe the rejection or lack of understanding from others. (Hispanic man)

Secrecy or silence may be a cultural response to a shameful or stigmatizing condition. The notion of voicing the problem or “describing yourself” may also have language barrier implications among Hispanic people; as one respondent noted,

Latinos. . . sometimes we have difficulty explaining our symptoms to someone else... I try not to look like I’m behaving strangely, knowing that I am the only one who knows... Personally, having my silence, right? I carry my burden. (Hispanic man)

That urinary frequency, urgency and UI may not be easy to “explain to someone else” may indicate both reluctance to talk about the problem because of embarrassment and/or difficulty in communicating the problem with others due to a language barrier. Silence as defence against stigma may be a mechanism to protect against stigma, but it poses the problem of bearing a silent burden and being a barrier to help-seeking.

Stigmatizer/Stigmatized

Similar to results found by others (Mitteness 1987), we found that respondents who had felt resentment from others related to their urinary symptoms themselves expressed negative opinions about generalized others with similar or worse symptoms. Recalling the man quoted above who told the story of encountering an incontinent man in an elevator, it is surprising to find that the same man spoke of his own embarrassment and discomfort related to similar symptoms:

When my mother died and I went to her funeral... I seemed to be the only one that had a urinary crisis. I literally had to leave the procession and run to the back of a building to pee. And then less than an hour later I had to go again. I’ll never forget that morning, because it was embarrassing. . . There have been times when. . . I actually lose control. If there’s a faucet running in my bathroom and I’m shaving, all of a sudden, oh my God, I just leaked a little bit. Now that really bothers me. (White man)

This respondent, despite having experienced troublesome urinary symptoms himself, was nevertheless critical about another person’s unmanaged UI (see quote on page 12). Another respondent described her reluctance to invite her incontinent friends into her home, despite being incontinent herself:

If people can’t hold their water and I know that, I don’t want to invite them up because I don’t want them peeing on my couch. (White woman)

Respondents in our sample spoke from the perspective of both the stigmatizer and the stigmatized throughout their interviews, demonstrating that the stigmatizer role may be assumed even by people who themselves have felt stigmatized for the same condition.

DISCUSSION

Study limitations

Two limitations of this study must be noted. First, the observational study design impedes our ability to assign causality. Second, time constraints impeded our ability to conduct back translation of Spanish interviews, thus some subtle meaning may have been lost. However, this qualitative study is strengthened by its large sample size, which assured we reached thematic saturation across all subgroups.

The stigma of lower urinary tract symptoms

This study provides the basis for a new and more comprehensive conceptualization of the stigma of LUTS that goes beyond incontinence to include the stigma of behaviors precipitated by urinary frequency and urgency symptoms. The stigma of frequency and urgency was rooted in social interruption, loss of socially-expected control of the body, speculation as to the nature of a non-specific “problem,” and the undesirable mixing of private behavior and public space. The stigma of urinary symptoms (including UI) hinged upon whether the problem was perceptible (i.e. through visible urine stains, odour, or trips to the bathroom) or concealed. Men in particular felt stigmatized for being seen making frequent trips to the bathroom and feared being viewed as impotent. Women feared being stigmatized based on having an unclean body and a compromised social identity. Hispanic individuals in particular voiced a tendency to keep urinary symptoms a secret from others.

While the negative social repercussions of incontinent episodes are well-documented in the literature, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to address the stigma of urinary frequency and urgency. The fact that urinary symptoms often co-occur (Barry et al. 2008), combined with our finding that other LUTS — not just — UI are stigmatizing, suggests that the stigmatization faced by individuals with LUTS may be more pervasive than previously thought. As there are a wider range of behaviors that engender negative reactions from others (e.g. frequent trips to the bathroom), individuals with LUTS may actually be stigmatized before they have leakage. Therefore healthcare practitioners should assess for psychological distress such as stress, anxiety and other consequences of stigma when patients present with LUTS, even in the absence of UI.

The reasons why people felt stigmatized for urinary frequency, urgency and incontinence varied by gender, and this has implications for help-seeking. Fear of stigmatization may affect individuals’ likelihood of help seeking, by either triggering or delaying it (Link and Phelan 2006). Men with frequency/urgency and women with UI (groups that reported feeling particularly stigmatized) may be most at risk of not seeking help because of the discomfort of talking about these symptoms. On the other hand, a fear of stigmatization could have the reverse effect, whereby individuals seek help in order to alleviate and prevent a negative response from others. In this case, women with UI might be more likely to seek help, as would men with frequency.

Hispanic people may be at increased risk of delaying or avoiding help-seeking for urinary symptoms altogether due to a sense of culturally-mandated secrecy around bodily conditions that are considered private or shameful. While feelings of embarrassment or shame related to frequency, urgency and UI were by no means unique to Hispanic people (nor was the impulse to hide these symptoms from others), the special emphasis by Hispanic individuals on secrecy may suggest a reluctance to confide in healthcare practitioners or likelihood of choosing social isolation over help-seeking. These findings corroborate previous research showing that shame and worry about what others would think were factors relevant to help-seeking among Hispanic individuals (Larkey et al. 2001).

Despite feeling stigmatized themselves, respondents expressed little sympathy for generalized others with urinary symptoms like their own. This finding reflects a typical human response to stigmatizing conditions (Goffman 1963), a “normal (if undesirable) consequence of peoples’ cognitive abilities and limitations” (Dovidio et al. 2000). The processes involved in stigmatizing urinary symptoms including frequency and urgency may involve rigid and furtive subconscious biases. Offering effective treatment options to patients with these symptoms may be the most realistic way to protect against negative reactions from others.

CONCLUSION

In this qualitative study of a diverse sample of men and women with LUTS, our theory that individuals find frequency and urgency symptoms — not just UI — to be stigmatizing was confirmed. The holistic focus of nursing on patient care and quality of life includes the social and behavioral elements of stigma. In their assessment and care of patients with urinary frequency and urgency as well as incontinence, nurses have a distinct opportunity to assess for stigma consequences (e.g. low self-esteem, anxiety or depression). We also found that individuals of different racial/ethnic backgrounds may have varying responses to their urinary symptoms, and that Hispanic people in particular may be reluctant to discuss their symptoms. Therefore nurses should include direct yet sensitive queries about urinary symptoms in their clinical assessments, and give information about the effectiveness of available treatments. Given the diverse nature of our sample, our findings are widely valid to black, white, and Hispanic men and women. That said, our findings may be most applicable to nursing practice in Western cultures, since the social construction of stigma and norms related to bodily processes may vary culturally. Future researchers in this area should quantify the relationship between perceived stigma and help-seeking for LUTS, as well as the relationship between perceived stigma of urinary symptoms and likelihood of confiding in a healthcare practitioner.

SUMMARY STATEMENT.

What is already known about this topic

Stigma is of concern to healthcare practitioners because it is associated with poorer health outcomes, stress, reduced quality of life, discrimination, and decreased use of health care.

Previous research on the stigmatization of individuals with urinary symptoms has focused almost exclusively on the experience of urinary incontinence.

There is reason to believe that urinary frequency and urgency are stigmatizing, as they give rise to frequent bathroom trips in the presence of others, drawing attention to a private act.

What this paper adds

Individuals with urinary symptoms perceive themselves to be stigmatized for behaviors associated with urinary frequency and urgency, and not just incontinence.

The stigma of frequency/urgency is rooted in social interruption, loss of control of the body, speculation as to the nature of a non-specific “problem,” and the “perceptibility” of symptoms.

Men and women experience stigma related to urinary symptoms differently, and Hispanic people in particular had a tendency to keep urinary symptoms a secret from others.

Implications for practice and policy

This study provides the basis for a new and more comprehensive conceptualization of the stigma of urinary symptoms that goes beyond incontinence to include behaviors engendered by frequency and urgency symptoms.

Healthcare practitioners should assess for stigma consequences (e.g. depression, anxiety) in individuals with symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency and incontinence, and should describe to them the efficacy of treatment options to circumvent stigmatization.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the NIH for supplying the funding for this study (Grant No. DK073835), as well as Journel Joseph, Senior Research Assistant, for his assistance with data analysis.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disorders, Grant No. DK073835

Footnotes

Author contributions

SLT was responsible for the study conception and design. EE and EB performed the data collection. EE, SPT and EB performed the data analysis. EE drafted the manuscript. EE, SPT, and SLT made critical revisions to the paper for important intellectual content. SLT obtained funding. EB provided administrative, technical and material support.

Author Contributions:

SLT was responsible for the study conception and design

EAE & EMB performed the data collection

EAE, SPT & EMB performed the data analysis.

EAE was responsible for the drafting of the manuscript.

EAE & SPT made critical revisions to the paper for important intellectual content.

SLT obtained funding

EMB provided administrative, technical or material support.

SLT supervised the study

Contributor Information

Emily A. Elstad, Email: emelstad@gmail.com, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Gillings School of Global Public Health USA.

Simone P. Taubenberger, New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA , USA.

Elizabeth M. Botelho, New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA USA.

Sharon L. Tennstedt, New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA USA.

References

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, Van Kerrebroeck P, Victor A, Wein A. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003;61(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglin DM, Link BG, Phelan JC. Racial differences in stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):857–62. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry MJ, Link CL, McNaughton-Collins MF, McKinlay JB. Overlap of different urological symptom complexes in a racially and ethnically diverse, community-based population of men and women. BJU Int. 2008;101(1):45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain KR, Shaw C. The social consequences of living with and dealing with incontinence--a carers perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(6):1274–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiverton PA, Wells TJ, Brink CA, Mayer R. Psychological factors associated with urinary incontinence. Clin Nurse Spec. 1996;10(5):229–33. doi: 10.1097/00002800-199609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinar A, Hall SA, Link CL, Kaplan SA, Kopp ZS, Roehrborn CG, Rosen RC. Cluster analysis and lower urinary tract symptoms in men: findings from the Boston Area Community Health Survey. BJU Int. 2008;101(10):1247–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne KS, Matza LS, Kopp ZS, Thompson C, Henry D, Irwin DE, Artibani W, Herschorn S, Milsom I. Examining lower urinary tract symptom constellations using cluster analysis. BJU Int. 2008;101(10):1267–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne KS, Wein AJ, Tubaro A, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, Kopp ZS, Aiyer LP. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2009;103(Suppl 3):4–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall CS, Moriarty D. Physical illness stigma and social rejection. Br J Soc Psychol. 1995;34 ( Pt 1):67–83. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1995.tb01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham-Burley S, Allbutt H, Garraway WM, Lee AJ, Russell EB. Perceptions of urinary symptoms and health-care-seeking behaviour amongst men aged 40–79 years. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46(407):349–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O, Westbrook L, Cramer J, Glassman M, Perrine K, Camfield C. Risk factors for poor health-related quality of life in adolescents with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1999;40 (12):1715–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Major B, Crocker J. Stigma: Introduction and Overview. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, Hebl MR, Hull JG, editors. The Social Pyschology of Stigma. The Guildford Press; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald MP, Link CL, Litman HJ, Travison TG, McKinlay JB. Beyond the lower urinary tract: the association of urologic and sexual symptoms with common illnesses. Eur Urol. 2007;52(2):407–15. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon K, Glover L, O’Neill M, Emberton M. Men and chronic illness: a qualitative study of LUTS. J Health Psychol. 2004;9(3):411–20. doi: 10.1177/1359105304042350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JA, Crocker J, Wyman JF, Krissovich M. Breaking the cycle of stigmatization: managing the stigma of incontinence in social interactions. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2005;32(1):38–52. doi: 10.1097/00152192-200501000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice Hall; New York: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hall SA, Cinar A, Link CL, Kopp ZS, Roehrborn CG, Kaplan SA, Rosen RC. Do urological symptoms cluster among women? Results from the Boston Area Community Health Survey. BJU Int. 2008;101(10):1257–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzemer WL, Human S, Arudo J, Rosa ME, Hamilton MJ, Corless I, Robinson L, Nicholas PK, Wantland DJ, Moezzi S, Willard S, Kirksey K, Portillo C, Sefcik E, Rivero-Mendez M, Maryland M. Exploring HIV stigma and quality of life for persons living with HIV infection. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(3):161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joachim G, Acorn S. Stigma of visible and invisible chronic conditions. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32 (1):243–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E, Farina A, Hastorf A, Markus H, Miller D, Scott R. Social stigma: The pyschology of marked relationships. W.H. Freeman & co; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Larkey LK, Hecht ML, Miller K, Alatorre C. Hispanic cultural norms for health-seeking behaviors in the face of symptoms. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28(1):65–80. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein B, Hook EW, 3rd, Sharma AK. Public tolerance, private pain: stigma and sexually transmitted infections in the American Deep South. Cult Health Sex. 2005;7(1):43–57. doi: 10.1080/13691050412331271416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Stigma and its public health implications. Lancet. 2006;367(9509):528–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz FE. The effects of stigma on the psychological well-being and life satisfaction of persons with mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1998;39(4):335–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007;52(2):389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitteness LS. So what do you expect when you’re 85? Urinary incontinence in late life. In: Roth J, Conrad P, editors. The Experience of Illness: Research in the Sociology of Health Care Series. Vol. 6. JAI Press, Inc; Greenwich, CT: 1987. pp. 177–219. [Google Scholar]

- Mitteness LS, Barker JC. Stigmatizing a “normal” condition: urinary incontinence in late life. Med Anthropol Q. 1995;9(2):188–210. doi: 10.1525/maq.1995.9.2.02a00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J, Richards L. Readme First for a User’s Guide to Qualitative Methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muhr T. User’s Manual for ATLAS.ti 5.0. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; Berlin: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(4):654–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson P, Kopp Z, Chapple CR, Kelleher C. It’s just the worry about not being able to control it! A qualitative study of living with overactive bladder. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13(Pt 2):343–59. doi: 10.1348/135910707X187786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oring E, editor. From Uretics to Uremics: A Contribution toward the Ethnography of Peeing. Chandler and Sharp; Novato, CA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson J. Stigma associated with postprostatectomy urinary incontinence. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2000;27(3):168–73. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5754(00)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Link BG, Dovidio JF. Stigma and prejudice: one animal or two? Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):358–67. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Feinglass J, Corrigan P. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental illness stigma. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(12):1020–3. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31815c046e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders Thompson VL, Bazile A, Akbar M. African American’s perceptions of psychotherapy and psychotherapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;39 :19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzmann L. Research and action: toward good quality of life and equity in health. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9(2):143–7. doi: 10.1586/erp.09.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Taft TH, Keefer L, Leonhard C, Nealon-Woods M. Impact of perceived stigma on inflammatory bowel disease patient outcomes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(8):1224–1232. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennstedt SL, Link CL, Steers WD, McKinlay JB. Prevalence of and risk factors for urine leakage in a racially and ethnically diverse population of adults: the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(4):390–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B, Perry RP, Magnusson J. An attributional analysis of reactions to stigmas. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55(5):738–48. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley A. Ethnic and racial differences in perceptions of dangerousness of persons with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:1328–1330. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.10.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde MH. Life with an indwelling urinary catheter: the dialectic of stigma and acceptance. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(9):1189–204. doi: 10.1177/1049732303257115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]