Abstract

Neurotransmitters such as serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) work closely with leptin and insulin to fine-tune the metabolic and neuroendocrine responses to dietary intake. Losing the sensitivity to excess food intake can lead to obesity, diabetes, and a multitude of behavioral disorders. It is largely unclear how different serotonin receptor subtypes respond to and integrate metabolic signals and which genetic variations in these receptor genes lead to individual differences in susceptibility to metabolic disorders. In an obese cohort of families of Northern European descent (n = 2,209), the serotonin type 5A receptor gene, HTR5A, was identified as a prominent factor affecting plasma levels of triglycerides (TG), supported by our data from both genome-wide linkage and targeted association analyses using 28 publicly available and 12 newly discovered single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), of which 3 were strongly associated with plasma TG levels (P < 0.00125). Bayesian quantitative trait nucleotide (BQTN) analysis identified a putative causal promoter SNP (rs3734967) with substantial posterior probability (P = 0.59). Functional analysis of rs3734967 by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) showed distinct binding patterns of the two alleles of this SNP with nuclear proteins from glioma cell lines. In conclusion, sequence variants in HTR5A are strongly associated with high plasma levels of TG in a Northern European population, suggesting a novel role of the serotonin receptor system in humans. This suggests a potential brain-specific regulation of plasma TG levels, possibly by alteration of the expression of HTR5A.

Keywords: family study, single nucleotide polymorphism association, electrophoretic mobility shift assay

the metabolic syndrome has been recognized as an epidemic with a high risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and stroke. It is characterized by a cluster of features including abdominal-visceral obesity, glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, increased blood pressure, and a specific dyslipidemia characterized by increased plasma triglyceride (TG) levels, increased predominance of dense low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles, and reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels (22, 33). This dyslipidemia significantly contributes to the cardiovascular complications of the syndrome.

High levels of plasma TG are caused by multiple factors, but a substantial portion of the variation is genetically determined (2, 17). However, only few genetic candidates have been discovered to date, and these only explain a small fraction of the total interindividual variation in plasma TG levels (20, 21, 35).

To elucidate additional genetic factors that determine metabolic syndrome-associated lipid traits, we examined the Metabolic Risk Complications of Obesity Genes (MRC-OB) cohort, which includes 2,209 individuals of Northern European descent from 507 families residing in 10 Midwestern US states. A genome-wide linkage scan using microsatellite markers revealed a 5-Mb region on chromosome 7q36 that harbors a quantitative trait locus (QTL) linked to lipid traits including plasma TG levels [logarithm of odds (LOD) = 3.7] and LDL cholesterol (LOD = 2.2) (33). This chromosomal region has repeatedly been associated with plasma TG levels (12, 23, 30) and thus may harbor major genetic determinants of this trait. The gene for the 5-HT receptor type 5A (HTR5A), encoding one of the five serotonin receptors in the human brain, is located at the peak of the linkage region.

Serotonin receptor subtypes have been identified in both animals and humans. These receptors belong to the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily, and once activated by the ligand, serotonin, they undergo conformational changes and activate adenylyl cyclase (4). Behavioral and pharmacological studies have shown the effect of the serotonin system on obesity and diabetes (3, 7, 37).

In the brain, the hypothalamus regulates feeding behavior and energy balance by integrating signals from peripheral hormones, metabolites, and nutrients. Recent work has shown that the release of serotonin in the hypothalamus is closely coupled with the action of leptin and insulin in response to a short-term high-fat diet (3). Signaling from insulin, leptin, and serotonin are interconnected and work cooperatively to maintain metabolic homeostasis. It is thus conceivable that sequence variation in genes encoding serotonin receptors affect obesity-related phenotypes. In fact, it has been shown that polymorphisms in the promoter region of the 5-HT2C receptor gene are associated with obesity and diabetes (37), as well as body mass index (BMI) and serum leptin levels (25). A recent animal behavioral study also showed that mice carrying a mutant 5-HT subtype 6 receptor gene were significantly less sensitive to diet-induced obesity compared with control mice. This was reflected in reduced weight gain and fat accumulation, but only when mice were fed a high-fat diet (14).

HTR5A has been associated with the genetic basis of psychiatric disorders such as autism, schizophrenia, mood disorders, and sleep disturbances (6, 10, 11) but has never been shown to directly influence obesity or its related traits. Based on our initial linkage findings, we investigated the association of sequence variants in HTR5A with plasma lipid levels. Our data presented here suggest for the first time that HTR5A affects plasma TG levels in our study cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Cohort

Cohort recruitment and individual phenotyping have been described previously (33). In brief, families with at least two obese siblings (BMI > 30), the availability of one (preferably both) parent, and one or more never-obese sibling (BMI <27) were recruited from the TOPS (“Take Off Pounds Sensibly”) membership in 10 Midwestern US states. Health information of all participants was obtained by a questionnaire, which included information on asthma, kidney or liver disease, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, thyroid disorders, diabetes, medications, menopausal status and hormonal therapy, weight history, and smoking history. Individuals were excluded from recruitment with the following conditions: pregnancy, type 1 diabetes, history of cancer, renal or hepatic disease, severe coronary artery disease, substance abuse, corticosteroids or thyroid dosages above replacement dose, history of weight loss of more than 10% in the preceding 12 mo, as well as individuals receiving lipid-lowering medications. Phenotypic measurements included BMI, waist and hip circumferences, as well as fasting plasma levels of glucose, insulin, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and plasma TG.

A total of 2,209 individuals distributed over 507 families of Northern European descent qualified for the above-mentioned criteria and were included in the initial linkage study. Based on these initial findings, 1,560 individuals were selected for further studies based on their contribution to the linkage on chromosome 7q36. All participants provided informed consent, and all protocols have been approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Initial Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Selection

For the initial analysis, the genomic region harboring HTR5A interval was examined to select single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) based on the linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns of the Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) population genotyped as part of the HapMap project. We aimed to genotype one SNP every 5 kb, and selected tagSNPs by applying the tagging algorithm of Carlson et al. (8) with an r2 cutoff of 0.8 to the CEPH data. For any region that is not covered by at least 1 SNP per 5 kb, additional SNPs were selected.

Resequencing

SNP discovery by resequencing was performed using 47 genomic DNA samples from unrelated subjects in the cohort. In addition, a HapMap CEPH sample was included as a reference. A 5-kb region covering a 3-kb promoter and the entire exon 1 of HTR5A gene were identified for resequencing. This 5-kb interval was divided into overlapping sections, which were then amplified by PCR using the primers and conditions described in Supplementary Table S1.1 PCR products were purified using Millipore MultiScreen-FB plates (catalog no. MSFBN6B10); samples were mixed 1:1 (vol/vol) with binding buffer (7 M guanidine, 200 mM MES, pH 5.6) in the plate, and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 5 min to bind DNA to the membrane. The samples were then washed twice in 80% ethanol before being eluted in sterile distilled H2O for sequencing. Sequencing was carried out using BigDye v3.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems) with standard techniques and analyzed on an Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA analyzer.

SNPs were identified by aligning all sequences using PolyPhred, and all putative sites were checked manually for confirmation. Results were independently confirmed by aligning all traces with the chromosome 7 reference sequence using the anchored alignment algorithm in PolyBayes. To remove potential redundancy from the genotyping and identify separate SNPs with identical genotypes, the genotypes of all SNPs were aligned using Visual Genotype (http://pga.mbt.washington.edu/VG2.html) to determine SNPs at different locations with identical genotypes.

Genotyping

Affymetrix 3K array genotyping.

Genomic DNA from 1,560 individuals was normalized to 150 ng/μl for genotyping on a custom-designed 3K GeneChip Universal Tag Array with the Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G MegAllele System (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) based on Molecular Inversion Probe technology (15, 16) (ParAllele Bioscience, Santa Clara, CA), as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, probes are hybridized to genomic DNA flanking the location of a SNP, an enzymatic gap-fill reaction circularizes the probes in an allele-specific manner, and the probes are then separated from unreacted and cross-reacted probes by an exonuclease reaction. The circularized (or “padlocked”) probes are inverted and amplified by PCR, and an allele-specific label is added; samples are then hybridized to GeneChip Universal Tag Arrays and scanned four times (once for each allele: A, C, G, T). Data were processed using the GeneChip Operating System version 1.3.0.031 (Affymetrix), and genotypes were determined by using the “cluster fit” function of TrueCall Analyzer version 7.0.0.22 (ParAllele BioScience). Genotypes for all samples were exported from TrueCall Analyzer version 7.0.0.22 (ParAllele BioScience); data files were transformed to linkage format for further analysis. Data were initially checked for relationship and genotyping errors using PedCheck version 1.1 (27); errors were corrected by removing all genotypes for a family at a discrepant SNP, as it was not possible to determine unambiguously which individual genotype was incorrect.

Genotyping using Invader technology.

SNPs uncovered by resequencing were genotyped using Invader technology (Third Wave Technologies, Madison, WI) (28). PCRs were designed to amplify products containing up to eight SNP loci, custom Invader assays were then designed for all SNPs using a commercial online platform (http://uip.twt.com/twt/uic/; Third Wave Technologies). Genotyping was carried out in a total volume of 6 μl, containing 0.5 μl PCR product, 0.02 μl each primary probe, 0.002 μl Invader probe, 1.12 μl of 2.6 M betaine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 2.75 μl TE buffer, 0.35 μl Cleavase (Third Wave Technologies), and 1.24 μl fluorescence resonance energy transfer mix (FRET mix, Third Wave Technologies). Reactions were denatured at 95°C for 5 min and then heated at 63°C for 15–120 min depending on individual SNP genotyping efficiency.

Association Analysis

Phenotype data of raw TG levels were first transformed into natural log (ln) to overcome the high-value deviation. Transformed data were examined for deviation from normality, and outliers that exceed at least 4 deviation units were removed from the data set. Twenty-eight publicly available SNPs across the 14.9-kb chromosomal region on chr7q36 that harbors the HTR5A gene, along with the 12 novel SNPs uncovered by resequencing, were examined for plasma TG association. For each SNP, a measured genotype approach was applied. Briefly, the effects of each single SNP genotype were modeled by assigning the homozygotes with values of 1 and −1, and the heterozygotes with values of 0, providing an additive model (13). To account for the phenotypic correlation between family members, SNPs were individually screened as covariates using variance components analysis that had been implemented in the computer program, SOLAR (“sequential oligogenic linkage analysis routines”) (1). An overall significance level for association (P < 0.00125) was based on a Bonferroni correction for 40 SNPs. All statistical models included age, sex, age by sex, age squared, age squared by sex, and diabetes status as covariates.

Bayesian Quantitative Trait Nucleotide Analysis

The quantitative trait nucleotide analysis using Bayesian model averaging and model selection (BQTN) has been developed (5) and demonstrated for successful identification of causative variants in a obesity study in the MRC-OB cohort (9). The BQTN methodology estimates the posterior probability that a given SNP has a direct effect (assuming that all genetic variation has been assayed in the candidate locus). Using the posterior probabilities as weights, the posterior mean and variance of any parameter are easily calculated and can then be used to form a statistical test that will yield the correct experiment-wide P value. Thus, this approach directly accounts for model uncertainty and provides a statistical estimate that a given SNP has a direct effect on the phenotype. This Bayesian model averaging and model selection procedure for QTN analysis is performed using the SOLAR computer package.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Human malignant glioma cell lines U-87 and D-54 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in RPMI-1640, supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 mg/ml each of streptomycin and penicillin, and 10% fetal bovine serum, at 37°C with 5% CO2. Complementary 41-mer oligonucleotides representing both allelic forms of the HTR5A promoter SNP (rs3734967, A>G) were obtained commercially (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA; see Table 2). Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed as described previously (24, 32). Briefly, nuclear extracts were prepared from ∼8 × 107 cells. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit. For EMSA, nuclear proteins (3 μg) were preincubated for 10 min on ice with 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) (Pharmacia) in a binding buffer (4% Ficoll, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 50 mM KCl). Nuclear proteins were then incubated with biotin-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide probes (20 fmol) for 30 min on ice, then analyzed on a 6% Novex DNA retardation gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and electroblotted onto a positively charged nylon membrane (Ambion, Austin, TX). Detection of protein/DNA complexes was achieved following incubation of the membrane with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase and development with luminal substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Light emission was captured on X-ray film.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide sequences for EMSA

| Name of Oligos | Sequence |

|---|---|

| HTR5A_A_F | CAGAAACTCCCCCACTGGCCAGAGGTTGCAAACATCCGGAT |

| HTR5A_A_R | ATCCGGATGTTTGCAACCTCTGGCCAGTGGGGGAGTTTCTG |

| HTR5A_G_F | CAGAAACTCCCCCACTGGCCGGAGGTTGCAAACATCCGGAT |

| HTR5A_G_R | ATCCGGATGTTTGCAACCTCCGGCCAGTGGGGGAGTTTCTG |

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) probes are all 41-mer with the 21st nucleotide carrying the alternative allele (A or G on the forward strand, bold) of rs3734967, the TG-associated promoter single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of HTR5A.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the study subjects are summarized in Table 1. These individuals are members of extended families ranging from 4 to 15 participants per family that contributed significantly (LOD > 0.001) to the observed linkage on chromosome 7q36.

Table 1.

The summary of cohort characteristics

| Variable | N | Mean | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 1,555 | 46.33719 | 44 | 13 | 90 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1,554 | 31.99735 | 30.7 | 17.1 | 75.31 |

| Height, cm | 1,552 | 167.8158 | 167 | 135 | 207 |

| Hips, cm | 1,544 | 116.0479 | 113 | 43 | 195 |

| Waist, cm | 1,545 | 101.6186 | 100 | 44 | 197 |

| Waist/hip ratio | 1,544 | 0.873274 | 0.87 | 0.53 | 1.45 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | 1,532 | 195.3707 | 194 | 66 | 458 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 1,535 | 38.65399 | 37 | 11 | 116 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 1,530 | 120.7794 | 119 | 13 | 360 |

| TG, mg/dl | 1,530 | 124.6669 | 105 | 27 | 802 |

| Insulin, pmol/l | 1,312 | 100.6275 | 80.28 | 5.6 | 1034.22 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 1,526 | 90.29838 | 84 | 36 | 379 |

| Insulin/glucose ratio | 1,311 | 1.114376 | 0.929022 | 0.0802213 | 14.803333 |

BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triglycerides.

For the analysis described in this study, we selected HTR5A as a positional candidate gene for the observed linkage as it is located at the center of QTL region. We therefore tested whether sequence variants in this gene are associated with altered plasma TG levels.

Initially, we selected 28 SNPs across the gene interval based on LD information from the HapMap consortium. These SNPs were genotyped in the 1,560 individuals using custom 3K GeneChip arrays. We identified 3 SNPs that were significantly associated with the lipid phenotype (P < 0.00125; Table 3). Of these variants, two SNPs (rs2873379 and rs1017488) were located within the putative promoter region (∼2.3 kb upstream of the start codon) of HTR5A gene (See Fig. 1).

Table 3.

BQTN analysis of SNPs in HTR5A proximity

| SNP | Chr7 Position† | Location | P Value of Association Analysis | Posterior Probability (BQTN) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs6972688 | 154260597 | upstream | 0.3383 | NS | |

| rs7805887 | 154261124 | upstream | 0.3357 | NS | |

| rs1583830 | 154273658 | upstream | 0.9240 | NS | |

| rs4960675 | 154278282 | upstream | 0.2459 | NS | |

| rs4960575 | 154283439 | upstream | 0.9166 | NS | |

| rs1440461 | 154287271 | upstream | 0.6806 | NS | |

| rs1440458 | 154291802 | upstream | 0.0184 | NS | |

| rs1440454 | 154294985 | upstream | 0.7459 | NS | |

| rs2873379* | 154297883 | upstream | 0.0005 | ||

| rs1017488* | 154297955 | upstream | 0.0011 | ||

| rs2698501* | 154298339 | upstream | 0.0003 | ||

| −1910G_A* | 154298348 | upstream | 0.0333 | NS | |

| −1457T_C* | 154298801 | upstream | 0.2060 | NS | |

| rs1881691* | 154299041 | upstream | 0.0019 | ||

| −1015A_G* | 154299243 | upstream | 0.9825 | NS | |

| rs3823534* | 154299836 | upstream | 0.0029 | ||

| rs3734966* | 154300082 | upstream | 0.6481 | NS | |

| rs3734967* | 154300156 | upstream | 0.0016 | 0.59 | |

| rs1800883* | 154300239 | upstream | 0.2819 | NS | |

| HTR5A starts | 154300258 | ||||

| rs6320* | 154300269 | exon | 0.0028 | ||

| 42T_C* | 154300300 | exon | 0.0635 | NS | |

| rs2241859* | 154301115 | intron | 0.0165 | NS | |

| 862G_A* | 154301120 | intron | 0.3144 | NS | |

| rs2581841* | 154301487 | intron | 0.0072 | ||

| rs4581000 | 154307991 | intron | 0.0521 | NS | |

| rs6597455 | 154309013 | intron | 0.0035 | ||

| rs732050 | 154311043 | intron | 0.0101 | NS | |

| rs2698512 | 154312220 | intron | 0.6632 | NS | |

| rs1657268 | 154312262 | intron | 0.2035 | NS | |

| rs6947679 | 154313114 | intron | 0.3617 | NS | |

| rs1730208 | 154313428 | intron | 0.0245 | NS | |

| rs893112 | 154317886 | downstream | 0.0246 | NS | |

| rs1657278 | 154322472 | downstream | 0.0247 | NS | |

| rs1730135 | 154322733 | downstream | 0.0312 | NS | |

| rs1436818 | 154322885 | downstream | 0.0302 | NS | 0.97 |

| rs1730182 | 154327796 | downstream | 0.0116 | NS | 0.97 |

| rs893109 | 154330522 | downstream | 0.0094 | ||

| rs1730143 | 154333441 | downstream | 0.1116 | NS | |

| rs1657265 | 154335681 | downstream | 0.0161 | NS | |

| rs893108 | 154371096 | downstream | 0.0258 | NS |

SNPs revealed by resequencing in 47 unrelated individuals of the Metabolic Risk Complications of Obesity Genes (MRC-OB) cohort. BQTN, Bayesian quantitative trait nucleotide.

Based on build 125. NS, nonsignificant association between SNP and TG level (P > 0.01).

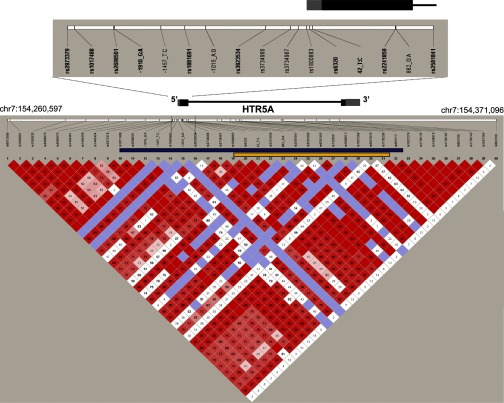

Fig. 1.

The HTR5A gene and linkage disequilibrium structure. The 40 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) cover the chromosomal interval chr7:154,260,597–154,371,096. The color diagram depicts the pair-wise linkage disequilibrium between SNPs (D′), as calculated for the family-based cohort of 1,560 individuals using the program Haploview version 4.1. The gene structure of HTR5A is depicted in bar and line format. Gray bars represent the untranslated mRNA sequences. A close-up view of the region resequenced in our study is shown with the exon 1 in location relative to the positions of the SNPs in this region. Haplotype blocks analyzed for their contribution to the observed linkage are highlighted by bars. A haplotype of contiguous SNPs depicted by the blue bar covers the region from 2,303 bp upstream to 17,628 bp downstream of the HTR5A gene and explains 26% of the observed linkage. In contrast, a haplotype for a smaller region, depicted by the yellow bar, which spans 19 bp upstream to 13,170 bp downstream of HTR5A, reduces the logarithm of the odds (LOD) score by only 5%. This analysis reveals a critical region between rs1017488 and rs1800883 likely to contain causal variants that contribute significantly to the observed linkage.

Next, we examined the effect of multi-SNP haplotypes on the original linkage with plasma TG. The analysis using haplotypes spanning LD blocks and comprised of HapMap SNPs revealed that the entire region spanning the HTR5A gene interval contains polymorphisms determining a substantial proportion of the linkage (LOD reduction >12%). A gene-centric haplotype analysis centered on the HTR5A gene was then conducted by testing haplotypes spanning different regions of the gene. Contiguous SNPs (rs1017488 to rs893112) that cover 2,303 bp upstream to 17,628 bp downstream of the HTR5A gene capture 26% of the observed linkage (Fig. 1, blue bar). However, when the tested region is restricted to a smaller region of contiguous SNPs (rs1800883 to rs1730208), which span 19 bp upstream to 13,170 bp downstream of HTR5A, the LOD score was reduced by 5% (Fig. 1, yellow bar). These results suggest sequence variants residing between or in LD with rs1017488 and rs1800883 may explain the majority of the contribution of HTR5A to the observed linkage, as illustrated in Fig. 1. This region spans 2,284 bp upstream of the start codon, and as this is a potential promoter region, we hypothesized that SNPs located within this region exert their effect on plasma TG by modulating the expression of HTR5A.

To find the causal SNP(s) that may alter the expression of HTR5A, we resequenced a 5-kb region including the promoter, exon 1, and a small portion of the first intronic space in 47 unrelated individuals. This included 7 individuals with normal TG levels and 40 individuals with TG levels in the top 10th percentile from the MRC-OB cohort. A total of 23 SNPs including 9 novel polymorphisms were detected. Analysis using Visual Genotype (http://pga.gs.washington.edu/VG2.html) identified seven pairs of SNPs with identical genotype distribution across the 47 samples. Only one SNP of each pair was selected for subsequent genotyping, resulting in a set of 16 informative SNPs across the region of interest (Table 3). Four of the 16 SNPs had previously been genotyped (rs2873379, rs1017488, rs1800883, rs2241859). The remaining 12 SNPs were genotyped in the 1,560 cohort using Invader assays.

Single SNP association with plasma TG was tested for each newly typed variant. Three SNPs were associated with plasma TG levels (P < 0.00125) and of these, two (rs2873379 and rs2698501) demonstrated strong association (P = 4.8 × 10−4 and 2.6 × 10−4, respectively; Table 3). The location of all SNPs relative to the exons of HTR5A is illustrated in Fig. 1, and their allelic and flanking sequences are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Flanking sequences and MAFs of the SNPs in this study

| SNP | −10 bases | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | +10 Bases | MAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs6972688 | TCACATACAT | A | G | TAGTTGGAGT | 0.34 |

| rs7805887 | CTTTGGAAAG | A | G | GATCTGAGTT | 0.34 |

| rs1583830 | CCTGTTCAGC | T | C | CTTGATTTGG | 0.394 |

| rs4960675 | GAATGTACCC | G | A | TGTAACCAGC | 0.328 |

| rs4960575 | TGGACACACC | A | C | GTCTCAGAAA | 0.386 |

| rs1440461 | ATGTAGCCCC | A | G | ATTCCAGGAC | 0.384 |

| rs1440458 | AAGAAAAGAA | T | C | GCCGGTCCTT | 0.052 |

| rs1440454 | CTGCCTGCAG | A | G | GTCTCAGCCA | 0.386 |

| rs2873379* | ATATGGCAGA | T | C | GGGAGTTTTA | 0.269 |

| rs1017488* | CAGCTTCATC | T | G | TAAAGCATAG | 0.266 |

| rs2698501* | ACTTTTTCCA | A | G | AGAAGAGGAT | 0.274 |

| −1910G_A* | AAAGAAGAGG | A | G | TTCATAGTTT | 0.048 |

| −1457T_C* | TTTTATATTG | C | T | TATATCATGT | 0.003 |

| rs1881691* | CTGCCTTATG | A | C | CTCTGAGGAG | 0.352 |

| −1015A_G* | GGAGAACAAA | A | G | GTTAGTGAAA | 0.002 |

| rs3823534* | GGGCAGGGAG | A | G | CAACGCGGTG | 0.257 |

| rs3734966* | AGCCACACCA | T | C | CTCCAACGGA | 0.072 |

| rs3734967* | CCCACTGGCC | A | G | GAGGTTGCAA | 0.327 |

| rs1800883* | GTACCCCAGG | G | C | CGGTCTCCTG | 0.357 |

| HTR5A starts | |||||

| rs6320* | TGGATTTACC | T | A | GTGAACCTAA | 0.285 |

| 42T_C* | CCTCTCCACC | C | T | CCTCCCCTTT | 0.055 |

| rs2241859* | TTACTCCCCC | C | A | ACTCCCAAAC | 0.323 |

| 862G_A* | GGAGTGGGGG | G | A | AGTAAACTGG | 0.024 |

| rs2581841* | GCATTTCATC | T | C | TAGTCTATTC | 0.32 |

| rs4581000 | TACTTTGAAT | A | C | TTTATTCAAC | 0.006 |

| rs6597455 | AATTGCAAGA | C | G | TTAGGATCAT | 0.344 |

| rs732050 | TTCTAATCCA | T | C | GATTGCAATA | 0.314 |

| rs2698512 | ACAGAAAGTG | G | A | GATTTTCAAT | 0.04 |

| rs1657268 | AAAGTTTGGA | T | C | TATTATGGAC | 0.388 |

| rs6947679 | AGGTTATAAA | G | A | ATGGTAGAAA | 0.097 |

| rs1730208 | GTGGATGTGC | G | A | GAATCCAGGC | 0.312 |

| rs893112 | AACAAGCAAT | T | C | CCCGGTGGAT | 0.311 |

| rs1657278 | GCTTAAACAA | A | C | TAGAGAGATT | 0.369 |

| rs1730135 | TCAGAAAACA | C | T | CTTCACAGAC | 0.364 |

| rs1436818 | ATATTTTCCA | G | A | TTAAACATCA | 0.362 |

| rs1730182 | AGAAAGCCAC | G | C | TCTGTATCCT | 0.37 |

| rs893109 | CTTAAAAAGT | G | A | GGGAAAATAT | 0.295 |

| rs1730143 | GGGACCCGCC | G | T | CCCCTTGGCT | 0.348 |

| rs1657265 | AGACATGAGA | C | T | GTGTAGCAGA | 0.238 |

| rs893108 | GCAGGGCAGC | C | T | TGGACGTGCT | 0.193 |

MAF, minor allele frequency.

Using this complete set of sequence variants across HTR5A, we performed BQTN analysis to statistically identify the most likely causal variant(s) in the interval. Of the 40 HTR5A variants (Table 3) only three SNPs were identified as potentially (rs3734967; probability = 0.59) or highly likely (rs1436818 and rs1730182; probability = 0.97) causal variants. SNP rs3734967 is located in the putative promoter region of the gene (position −102), and the other two variants (rs1436818 and rs1730182) are 3′ to the last exon (9 kb and 14 kb, respectively).

Allele-specific phenotypic means of plasma TG levels for the promoter SNP rs3734967 suggest that the G allele increases levels of plasma TG, with GG homozygotes having a 15% increase in plasma TG levels (138.48 vs. 120.05 mg/dl) relative to homozygotes for the A allele. This effect seems to be additive, with heterozygotes having an intermediate TG level (Table 5). Individuals homozygous for the C allele of rs1730182 have on average an increase in plasma TG levels of 11.5% (131.68 vs. 118.11 mg/dl), and the effect of the C allele seems to be dominant (Table 5). This effect is mirrored by the alleles of rs1436818. In all cases, the minor allele is associated with the increase in plasma TG levels.

Table 5.

Genotype effect of HTR5A posterior probable SNPs on TG levels in MRC-OB

| SNP | MAF | Genotype | TG, mg/dl |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs3734967 | 0.3068 | AA | 120.05 |

| (G) | AG | 129.86 | |

| GG | 138.48 | ||

| rs1436818 | 0.3570 | AA | 132.22 |

| (A) | AG | 131.29 | |

| GG | 119.59 | ||

| rs1730182 | 0.3654 | CC | 131.68 |

| (C) | CG | 133.10 | |

| GG | 118.11 |

In testing the impact of these three variants on the original linkage signal, we found each SNP only minimally affects the LOD score. However, the three SNPs combined result in a 16% reduction in the LOD score.

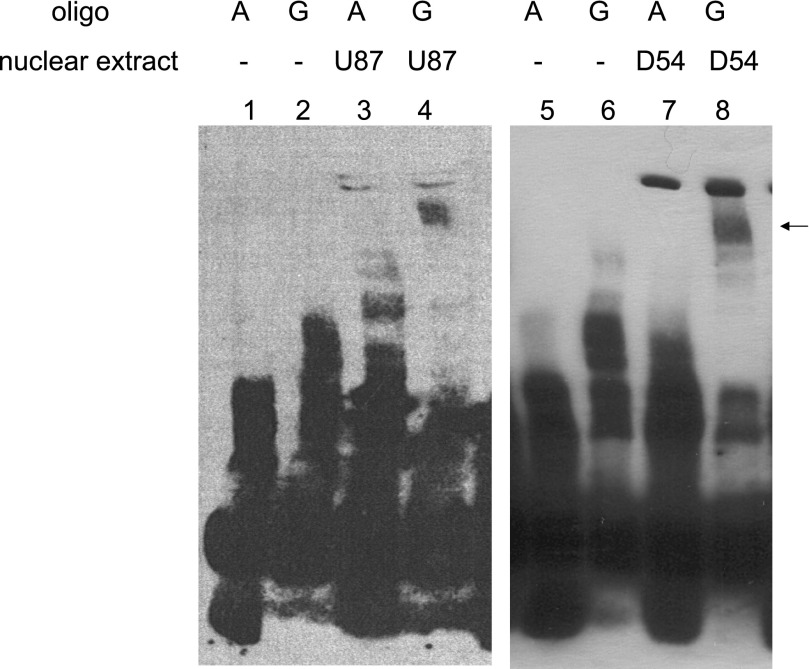

Since HTR5A is exclusively expressed in the brain, it is difficult to measure genotype-specific gene expression directly. To explore how the statistically causal promoter variant of HTR5A (rs3734967) may exert its effect, we performed EMSAs to test whether the two alleles have different protein binding affinities in vitro. Nuclear proteins from two different glioma cell lines consistently exhibit distinct gel shift patterns between the two allelic forms of rs3734967 (Fig. 2). These results suggest that rs3734967 may affect TG levels by modulating the binding of transcription factor(s) or other nuclear proteins to the promoter of HTR5A.

Fig. 2.

Allelic polymorphisms of rs3734967 residing in the promoter of HTR5A present distinct binding patterns with nuclear proteins from brain cells. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay was performed in two different human glioma cell lines, U-87 (lanes 3 and 4) and D-54 (lanes 7 and 8). Oligos carrying rs3734967 and its surrounding sequence were assayed for binding capabilities with proteins from the two types of nuclear extracts. A pattern is consistently observed in both cell lines showing that the G allele (lanes 4 and 8) binds unidentified protein factors, causing a mobility shift in the electrophoresis. This pattern does not appear for the A allele (lanes 3 and 7), nor for the A or the G allele when no nuclear protein is applied (lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6). The arrow points at mobility shift of oligonucleotides with the G allele caused by differential protein binding. Results are representative of at least 4 separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

The serotonin system is intricately involved in central metabolic balancing (3, 25, 29). Consequently, sequence variants in serotonin receptor genes have been shown to be associated with obesity and diabetes-related traits (25, 37). In our genome-wide linkage analysis of plasma TG levels, we identified a QTL on chromosome 7q36. Since a serotonin receptor gene, HTR5A, is located at the center of the region, we tested the involvement of this gene in the regulation of plasma lipid levels. As our data demonstrate, we identified associated sequence variants in this gene that affect plasma TG in an obese cohort of Northern European descent. While the mechanism by which this receptor influences plasma lipids remains unclear, our data suggest that the associated promoter SNP (rs3734967) may result in altered transcription factor binding and thus modified gene expression. However, this variant alone explains only a small fraction (<1%) of the total variation in TG levels, suggesting that additional functional variants in this gene as well as in other genes in the QTL interval also contribute to the observed linkage effect. All three of the identified putative causal variants in HTR5A combined account for 16% of the observed linkage. Therefore, it is likely that future comprehensive analyses of the QTL region will uncover additional genes and sequence variants that contribute to the altered lipid profile in our study cohort and explain the remaining fraction of the linkage effect.

The G allele of the promoter SNP rs3734967 appears to be the risk allele for elevated TG levels in our cohort and results in a 15.4% increase in TG levels in individuals homozygous for the G-allele compared with A-allele homozygous individuals. Functional analysis of the promoter SNP using EMSA resulted in distinct protein binding patterns of each of the two alleles, suggesting this SNP may exert its influence on the gene expression by modulating promoter binding with unknown transcription factors. However, the putative mode of action for the other two variants identified in our analysis remains to be elucidated.

As demonstrated by the haplotype analysis, there are likely other variants in or around HTR5A that significantly contribute to the effect seen in our linkage study. These may be rare variants that were not uncovered in our resequencing efforts or may be located in other coding or regulatory regions surrounding the gene. Thus, it is likely that further resequencing of the genomic interval will help uncover additional causal variants that combine to explain a significant proportion of the observed linkage on chromosome 7q36.

Increased plasma TG levels are a fundamental feature of the metabolic syndrome in humans. This form of dyslipidemia significantly contributes to the cardiovascular complications of the syndrome. Both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the etiology of this dyslipidemia, but the underlying genes and mutations are virtually unknown. Recently, a meta-analysis study combining seven genome-wide association studies (GWAS) on polygenic dyslipidemia in more than 40,000 individuals was performed to identify novel genes that alter plasma TG levels (21). Although several new genes and polymorphisms were identified (in addition to previously reported associated genes), the polymorphisms identified in this study explain less than 15% of the interindividual variance in plasma TG levels in any of the study populations. HTR5A gene variants did not show significant association with the same lipid traits examined in these studies (20, 21, 35), and no other variants on chromosome 7q36 were identified despite the successful replication of the linkage finding in numerous other studies. This lack of replication in the results from GWAS and linkage studies needs to be further explored. At this point, it is unclear whether the lack of replication is due to the study design (e.g., SNP selection) or the different population structures or histories. Only specific testing of putative causal variants directly in extensive cohorts and population-based samples will help validate the role of HTR5A in lipid metabolism.

With its prominent role in regulating feeding behavior and energy homeostasis, the central nervous system likely affects obesity and related metabolic phenotypes. This has been supported by a number of recent studies on obesity. At least five genes related to neuronal function have been identified in GWAS studies of BMI published last year (26, 34, 36). Our discovery of a serotonin receptor gene significantly influencing the plasma TG levels also underscores the important role of the brain in regulating obesity-related metabolic pathways. Our results provide the first in-depth evidence of a serotonin receptor gene contributing to plasma lipid regulation, an important risk factor in obese individuals for developing CVD and stroke. Additional functional studies will be necessary to unveil the underlying cellular and physiological mechanisms of how this receptor affects plasma TG levels and may help uncover novel pathways and targets for future lipid-lowering therapies to reduce the CVD risk.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-74168 (to M. Olivier).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Regina Cole, Milena Zelembaba, Jack Littrell, and other members of the Olivier lab for technical assistance.

Present address of E. M. Smith: Dept. of Biological Sciences, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK.

Present address of T. M. Baye: Cincinnati Children's Hospital, Cincinnati, OH.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

REFERENCES

- 1. Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet 62: 1198–1211, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Austin MA, King MC, Bawol RD, Hulley SB, Friedman GD. Risk factors for coronary heart disease in adult female twins. Genetic heritability and shared environmental influences. Am J Epidemiol 125: 308–318, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Banas SM, Rouch C, Kassis N, Markaki EM, Gerozissis K. A dietary fat excess alters metabolic and neuroendocrine responses before the onset of metabolic diseases. Cell Mol Neurobiol 29: 157–168, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barnes NM, Sharp T. A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology 38: 1083–1152, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blangero J, Goring HH, Kent JW, Williams JT, Peterson CP, Almasy L, Dyer TD. Quantitative trait nucleotide analysis using Bayesian model selection. Hum Biol 77: 541–559, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blier P, de Montigny C. Serotonin and drug-induced therapeutic responses in major depression, obsessive-compulsive and panic disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 21: 91S–98S, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blundell JE, Lawton CL, Halford JC. Serotonin, eating behavior, and fat intake. Obes Res 3, Suppl 4: 471S–476S, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carlson CS, Eberle MA, Rieder MJ, Yi Q, Kruglyak L, Nickenson DA. Selecting a maximally informative set of single-nucleotide polymorphisms for association analyses using linkage disequilibrium. Am J Hum Genet 74: 106–120, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Curran JE, Jowett JB, Elliott KS, Gao Y, Gluschenko K, Wang J, Abel Azim DM, Cai G, Mahaney MC, Comuzzie AG, Dyer TD, Walder KR, Zimmet P, MacCluer JW, Collier GR, Kissebah AH, Blangero J. Genetic variation in selenoprotein S influences inflammatory response. Nat Genet 37: 1234–1241, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dijk DJ, Czeisler CA. Contribution of the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat to sleep propensity, sleep structure, electroencephalographic slow waves, and sleep spindle activity in humans. J Neurosci 15: 3526–3538, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dubertret C, Hanoun N, Ades J, Hamon M, Gorwood P. Family-based association studies between 5-HT5A receptor gene and schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 38: 371–376, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duggirala R, Blangero J, Almasy L, Dyer TD, Williams KL, Leach RJ, O'Connell P, Stern MP. A major susceptibility locus influencing plasma triglyceride concentrations is located on chromosome 15q in Mexican Americans. Am J Hum Genet 66: 1237–1245, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Falconer DS. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics (3rd ed.). New York: Longman Scientific and Technical, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frassetto A, Zhang J, Lao JZ, White A, Metzger JM, Fong TM, Chen RZ. Reduced sensitivity to diet-induced obesity in mice carrying a mutant 5-HT6 receptor. Brain Res 1236: 140–144, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hardenbol P, Baner J, Jain M, Nilsson M, Namsaraev EA, Karlin-Neumann GA, Fakhrai-Rad H, Ronaghi M, Willis TD, Landegren U, Davis RW. Multiplexed genotyping with sequence-tagged molecular inversion probes. Nat Biotechnol 21: 673–678, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hardenbol P, Yu F, Belmont J, Mackenzie J, Bruckner C, Brundage T, Boudreau A, Chow S, Eberle J, Erbilgin A, Falkowski M, Fitzgerald R, Ghose S, Iartchouk O, Jain M, Karlin-Neumann G, Lu X, Miao X, Moore B, Moorhead M, Namsaraev E, Pasternak S, Prakash E, Tran K, Wang Z, Jones HB, Davis RW, Willis TD, Gibbs RA. Highly multiplexed molecular inversion probe genotyping: over 10,000 targeted SNPs genotyped in a single tube assay. Genome Res 15: 269–275, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heller DA, de Faire U, Pedersen NL, Dahlen G, McClearn GE. Genetic and environmental influences on serum lipid levels in twins. N Engl J Med 328: 1150–1156, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. J Am Stat Assoc 90: 773–795, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kathiresan S, Manning AK, Demissie S, D'Agostino RB, Surti A, Guiducci C, Gianniny L, Burtt NP, Melander O, Orho-Melander M, Arnett DK, Peloso GM, Ordovas JM, Cupples LA. A genome-wide association study for blood lipid phenotypes in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet 8, Suppl 1: S17, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kathiresan S, Melander O, Guiducci C, Surti A, Burtt NP, Rieder MJ, Cooper GM, Roos C, Voight BF, Havulinna AS, Wahlstrand B, Hedner T, Corella D, Tai ES, Ordovas JM, Berglund G, Vartiainen E, Jousilahti P, Hedblad B, Taskinen MR, Newton-Cheh C, Salomaa V, Peltonen L, Groop L, Altshuler DM, Orho-Melander M. Six new loci associated with blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides in humans. Nat Genet 40: 189–197, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, Demissie S, Musunuru K, Schadt EE, Kaplan L, Bennett D, Li Y, Tanaka T, Voight BF, Bonnycastle LL, Jackson AU, Crawford G, Surti A, Guiducci C, Burtt NP, Parish S, Clarke R, Zelenika D, Kubalanza KA, Morken MA, Scott LJ, Stringham HM, Galan P, Swift AJ, Kuusisto J, Bergman RN, Sundvall J, Laakso M, Ferrucci L, Scheet P, Sanna S, Uda M, Yang Q, Lunetta KL, Dupuis J, de Bakker PI, O'Donnell CJ, Chambers JC, Kooner JS, Hercberg S, Meneton P, Lakatta EG, Scuteri A, Schlessinger D, Tuomilehto J, Collins FS, Groop L, Altshuler D, Collins R, Lathrop GM, Melander O, Salomaa V, Peltonen L, Orho-Melander M, Ordovas JM, Boehnke M, Abecasis GR, Mohlke KL, Cupples LA. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet 41: 56–65, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kissebah AH, Sonnenberg GE, Myklebust J, Goldstein M, Broman K, James RG, Marks JA, Krakower GR, Jacob HJ, Weber J, Martin L, Blangero J, Comuzzie AG. Quantitative trait loci on chromosomes 3 and 17 influence phenotypes of the metabolic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 14478–14483, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li WD, Dong C, Li D, Garrigan C, Price RA. A genome scan for serum triglyceride in obese nuclear families. J Lipid Res 46: 432–438, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li YC, Ross J, Scheppler JA, Franza BR., Jr An in vitro transcription analysis of early responses of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat to different transcriptional activators. Mol Cell Biol 11: 1883–1893, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McCarthy S, Mottagui-Tabar S, Mizuno Y, Sennblad B, Hoffstedt J, Arner P, Wahlestedt C, Andersson B. Complex HTR2C linkage disequilibrium and promoter associations with body mass index and serum leptin. Hum Genet 117: 545–557, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meyre D, Delplanque J, Chevre JC, Lecoeur C, Lobbens S, Gallina S, Durand E, Vatin V, Degraeve F, Proenca C, Gaget S, Korner A, Kovacs P, Kiess W, Tichet J, Marre M, Hartikainen AL, Horber F, Potoczna N, Hercberg S, Levy-Marchal C, Pattou F, Heude B, Tauber M, McCarthy MI, Blakemore AI, Montpetit A, Polychronakos C, Weill J, Coin LJ, Asher J, Elliott P, Jarvelin MR, Visvikis-Siest S, Balkau B, Sladek R, Balding D, Walley A, Dina C, Froguel P. Genome-wide association study for early-onset and morbid adult obesity identifies three new risk loci in European populations. Nat Genet 41: 157–159, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O'Connell JR, Weeks DE. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet 63: 259–266, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Olivier M, Chuang LM, Chang MS, Chen YT, Pei D, Ranade K, de Witte A, Allen J, Tran N, Curb D, Pratt R, Neefs H, de Arruda Indig M, Law S, Neri B, Wang L, Cox DR. High-throughput genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms using new biplex invader technology. Nucleic Acids Res 30: e53, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Orosco M, Gerozissis K. Macronutrient-induced cascade of events leading to parallel changes in hypothalamic serotonin and insulin. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 25: 167–174, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shearman AM, Ordovas JM, Cupples LA, Schaefer EJ, Harmon MD, Shao Y, Keen JD, DeStefano AL, Joost O, Wilson PW, Housman DE, Myers RH. Evidence for a gene influencing the TG/HDL-C ratio on chromosome 7q32.3-qter: a genome-wide scan in the Framingham study. Hum Mol Genet 9: 1315–1320, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith EM, Wang X, Littrell J, Eckert J, Cole R, Kissebah AH, Olivier M. Comparison of linkage disequilibrium patterns between the HapMap CEPH samples and a family-based cohort of Northern European descent. Genomics 88: 407–414, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith EM, Zhang Y, Baye TM, Gawrieh S, Cole R, Blangero J, Carless MA, Curran JE, Dyer TD, Abraham LJ, Moses EK, Kissebah AH, Martin LJ, Olivier M. INSIG1 influences obesity-related hypertriglyceridemia in humans. J Lipid Res 51: 701–708, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sonnenberg GE, Krakower GR, Martin LJ, Olivier M, Kwitek AE, Comuzzie AG, Blangero J, Kissebah AH. Genetic determinants of obesity-related lipid traits. J Lipid Res 45: 610–615, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thorleifsson G, Walters GB, Gudbjartsson DF, Steinthorsdottir V, Sulem P, Helgadottir A, Styrkarsdottir U, Gretarsdottir S, Thorlacius S, Jonsdottir I, Jonsdottir T, Olafsdottir EJ, Olafsdottir GH, Jonsson T, Jonsson F, Borch-Johnsen K, Hansen T, Andersen G, Jorgensen T, Lauritzen T, Aben KK, Verbeek AL, Roeleveld N, Kampman E, Yanek LR, Becker LC, Tryggvadottir L, Rafnar T, Becker DM, Gulcher J, Kiemeney LA, Pedersen O, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K. Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Nat Genet 41: 18–24, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Willer CJ, Sanna S, Jackson AU, Scuteri A, Bonnycastle LL, Clarke R, Heath SC, Timpson NJ, Najjar SS, Stringham HM, Strait J, Duren WL, Maschio A, Busonero F, Mulas A, Albai G, Swift AJ, Morken MA, Narisu N, Bennett D, Parish S, Shen H, Galan P, Meneton P, Hercberg S, Zelenika D, Chen WM, Li Y, Scott LJ, Scheet PA, Sundvall J, Watanabe RM, Nagaraja R, Ebrahim S, Lawlor DA, Ben-Shlomo Y, Davey-Smith G, Shuldiner AR, Collins R, Bergman RN, Uda M, Tuomilehto J, Cao A, Collins FS, Lakatta E, Lathrop GM, Boehnke M, Schlessinger D, Mohlke KL, Abecasis GR. Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet 40: 161–169, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Willer CJ, Speliotes EK, Loos RJ, Li S, Lindgren CM, Heid IM, Berndt SI, Elliott AL, Jackson AU, Lamina C, Lettre G, Lim N, Lyon HN, McCarroll SA, Papadakis K, Qi L, Randall JC, Roccasecca RM, Sanna S, Scheet P, Weedon MN, Wheeler E, Zhao JH, Jacobs LC, Prokopenko I, Soranzo N, Tanaka T, Timpson NJ, Almgren P, Bennett A, Bergman RN, Bingham SA, Bonnycastle LL, Brown M, Burtt NP, Chines P, Coin L, Collins FS, Connell JM, Cooper C, Smith GD, Dennison EM, Deodhar P, Elliott P, Erdos MR, Estrada K, Evans DM, Gianniny L, Gieger C, Gillson CJ, Guiducci C, Hackett R, Hadley D, Hall AS, Havulinna AS, Hebebrand J, Hofman A, Isomaa B, Jacobs KB, Johnson T, Jousilahti P, Jovanovic Z, Khaw KT, Kraft P, Kuokkanen M, Kuusisto J, Laitinen J, Lakatta EG, Luan J, Luben RN, Mangino M, McArdle WL, Meitinger T, Mulas A, Munroe PB, Narisu N, Ness AR, Northstone K, O'Rahilly S, Purmann C, Rees MG, Ridderstrale M, Ring SM, Rivadeneira F, Ruokonen A, Sandhu MS, Saramies J, Scott LJ, Scuteri A, Silander K, Sims MA, Song K, Stephens J, Stevens S, Stringham HM, Tung YC, Valle TT, Van Duijn CM, Vimaleswaran KS, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Wallace C, Watanabe RM, Waterworth DM, Watkins N, Witteman JC, Zeggini E, Zhai G, Zillikens MC, Altshuler D, Caulfield MJ, Chanock SJ, Farooqi IS, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Hattersley AT, Hu FB, Jarvelin MR, Laakso M, Mooser V, Ong KK, Ouwehand WH, Salomaa V, Samani NJ, Spector TD, Tuomi T, Tuomilehto J, Uda M, Uitterlinden AG, Wareham NJ, Deloukas P, Frayling TM, Groop LC, Hayes RB, Hunter DJ, Mohlke KL, Peltonen L, Schlessinger D, Strachan DP, Wichmann HE, McCarthy MI, Boehnke M, Barroso I, Abecasis GR, Hirschhorn JN. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits Consortium GIANT Consortium. Six new loci associated with body mass index highlight a neuronal influence on body weight regulation. Nat Genet 41: 25–34, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yuan X, Yamada K, Ishiyama-Shigemoto S, Koyama W, Nonaka K. Identification of polymorphic loci in the promoter region of the serotonin 5-HT2C receptor gene and their association with obesity and type II diabetes. Diabetologia 43: 373–376, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.