Abstract

αA-crystallin is a molecular chaperone and an antiapoptotic protein. This study investigated the mechanism of inhibition of apoptosis by human αA-crystallin and determined if the chaperone activity of αA-crystallin is required for the antiapoptotic function. αA-crystallin inhibited chemical-induced apoptosis in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and HeLa cells by inhibiting activation of caspase-3 and -9. In CHO cells, it inhibited apoptosis induced by the overexpression of human proapoptotic proteins, Bim and Bax. αA-crystallin inhibited doxorubicin-mediated activation of human procaspase-3 in CHO cells and it activated the PI3K/Akt cell survival pathway by promoting the phosphorylation of PDK1, Akt and phosphatase tensin homologue in HeLa cells. The phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K) activity was increased by αA-crystallin overexpression but the protein content was unaltered. Downregulation of PI3K by the expression of a dominant-negative mutant or inhibition by LY294002 abrogated the ability of αA-crystallin to phosphorylate Akt. These antiapoptotic functions of αA-crystallin were enhanced in a mutant protein (R21A) that shows increased chaperone activity than the wild-type (Wt) protein. Interestingly, a mutant protein (R49A) that shows decreased chaperone activity was far weaker than the Wt protein in its antiapoptotic functions. Together, our study results show that αA-crystallin inhibits apoptosis by enhancing PI3K activity and inactivating phosphatase tensin homologue and that the antiapoptotic function is directly related to its chaperone activity.

Keywords: apoptosis, chaperone, crystalline, PI3K, PTEN

α-Crystallin is a major structural protein of the lens; it accounts for nearly 40% of the total protein in the lens and is required for maintenance of lens transparency.1 The lens grows throughout age, though at a very slow rate. The proteins in the lens have negligible turnover and therefore their levels remain more or less constant during aging. α-Crystallin consists of two similar subunits, αA- and αB-crystallin, that exist in the lens as heteroaggregates in a 3 : 1 ratio with an average molecular mass of ∼800 kDa. Human αA- and αB-crystallin share nearly 60% sequence homology.2 Although αA-crystallin is expressed mainly in the lens and shows low levels of expression in the retina, αB-crystallin is expressed at high levels in the lens and in other tissues, such as skeletal and cardiac muscle, kidney and brain.3

α-Crystallin belongs to the small heat shock protein (sHSP) superfamily, featured by a conserved crystallin domain flanked by an N-terminal and a short C-terminal domain.4 sHSPs, including α-crystallin, are antiapoptotic proteins that provide protection against a wide range of cellular stresses. It has been reported that cells overexpressing αA- or αB-crystallin are more resistant to thermal,5 osmotic6 and oxidative stress.7 In addition, recent studies have shown that α-crystallin prevents apoptosis induced by a variety of agents, including staurosporine,8, 9 tumor necrosis factor-α,10 UVA light,8 hydrogen peroxide11 and etoposide.9

The robust effects of α-crystallin against these apoptosis inducers prompted many researchers to investigate molecular mechanisms by which α-crystallin functions as an antiapoptotic protein. α-Crystallin has been shown to bind the proapoptotic molecules p53, Bax and Bcl-X(S), and therefore could prevent their translocation to mitochondria during apoptosis.9, 12 It has been shown that αB-crystallin can suppress autocatalytic maturation of procaspase-313, 14 and inhibit cytochrome c release during apoptosis.15 Whether αA-crystallin shows these properties is not yet known. During fiber cell differentiation in the lens, α-crystallin suppresses caspase activity, resulting in the retention of lens fiber cell integrity following degradation of mitochondria and other organelles.16 This finding suggests that αA-crystallin might possess antiapoptotic functions similar to αB-crystallin. UVA-induced apoptosis in lens epithelial cells is inhibited by αA- and αB-crystallins through regulation of PKC-α, RAF/MEK/ERK and Akt signaling pathways,17 suggesting additional mechanisms of apoptosis inhibition. Phosphorylation of α-crystallin appears to be important for its antiapoptotic function, as mimicking phosphorylation of αB-crystallin at serine-59 appears to be sufficient to protect cardiac myocytes from apoptosis.18 Whether this property applies for αA-crystallin is not known.

In addition to being antiapoptotic proteins, both αA- and αB-crystallins are molecular chaperones; they prevent aggregation of structurally perturbed proteins.19, 20 It has been reported that, under heat and other stress conditions, proteins retain their native secondary structure in the presence of α-crystallin.21 A decrease in the chaperone function of α-crystallin in the aging lens22 may be one reason for the onset of age-related cataracts in humans.

Although glycation, a posttranslational modification of proteins by sugars and ascorbate, reduces the chaperone function of α-crystallin,23 modification of α-crystallin by a similar process initiated by methylglyoxal (MGO) improves its chaperone function.24, 25 MGO is a metabolic product derived from glycolytic intermediates and is present ubiquitously in humans and in relatively large amounts in the human lens.26 Reaction of MGO with αA-crystallin produces argpyrimidine and hydroimidazolone adducts on arginine residues in tissue proteins, including proteins of the lens.27, 28 We previously identified argpyrimidine on R21, R49 and R103 in MGO-modified αA-crystallin.24 Later, we used site-directed mutagenesis in which specific arginine residues were replaced with alanines and showed that the R21A and R103A mutations made αA-crystallin a better chaperone, whereas the R49A mutation made it a weaker chaperone.29 The double mutant R21A/R49A was a better chaperone compared with the unmodified protein, which implied that R21A mutation overrode the negative effect of R49A mutation. These studies showed that chemical modification by MGO may be beneficial to the chaperone function of αA-crystallin in the lens.

The R116C and R49C mutations in human αA-crystallin and R120G and P20S mutations in αB-crystallin, which are associated with autosomal dominant cataracts in humans, cause weaker chaperone function along with considerably lower antiapoptotic functions relative to the wild-type (Wt) protein.7, 30, 31, 32 Despite these advances in our understanding of α-crystallin's chaperone and antiapoptotic functions, it is still not clear whether the two are directly linked. In this study, we show by several criteria that these functions are intimately coupled.

Results

Overexpression of human αA-crystallin

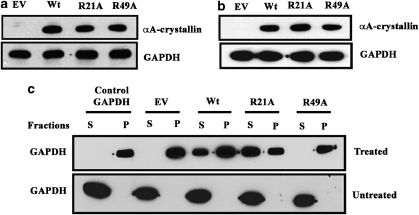

We generated stable cell lines in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells that overexpressed Wt, R21A or R49A. Clones expressing human αA-crystallin were analyzed by western blot analysis using an anti-αA-crystallin antibody (Figure 1a). Purified human αA-crystallin of varied concentrations was used to quantify the expression of human αA-crystallin. Positive clones expressing comparable amounts of human αA-crystallin, ∼2.5 ng human αA-crystallin per mg of total protein, were used. Wt, R21A or R49A were also overexpressed in HeLa cells by transient transfections (Figure 1b). Our data suggest that the two cell types expressed similar levels of each αA-crystallin variant.

Figure 1.

Overexpression of wild-type (Wt) and mutant αA-crystallins and demonstration of in situ chaperone function. Human Wt, R21A or R49A αA-crystallin in pCDNA3.1(−) were stably overexpressed in (a) Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and (b) transiently transfected in HeLa cells. αA-Crystallin was detected using anti-αA-crystallin polyclonal antibody. glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the loading control. (c) Western blot to show that R21A is a better chaperone than R49A in CHO cells. Cell lysates of control (Untreated) and those incubated at 55°C for 3 h (Treated) were separated into soluble (S) and insoluble (P) fractions by centrifugation. GAPDH was detected using an anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibody. GAPDH from rabbit muscle (Sigma) was used as the positive control

R21A mutant protein is a better chaperone in CHO cells

To determine if overexpressed αA-crystallin shows chaperone function in CHO cells and if R21A and R49A mutant show their expected changes in the chaperone function, we used a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) aggregation assay. We first determined the optimal temperature and time for complete aggregation of GAPDH and found that incubation at 55°C for 3 h resulted in complete aggregation of the pure protein. On the basis of this result, we incubated cell lysates at 55°C for 3 h and then fractioned the lysate into soluble and insoluble fractions followed by western blotting for GAPDH. We found that in all cell lysates not subjected to heat treatment, GAPDH was entirely present in the supernatant fraction (Figure 1c). However, in heat-treated cell lysates GAPDH was found in the pellet fraction as well. In the lysate of cells with empty vector (EV), GAPDH was present entirely in the pellet fraction and in the lysate of cells with Wt protein, it was present both in the soluble and insoluble fractions, suggesting Wt protein inhibited aggregation of GAPDH. In the lysate of cells expressing R21A protein, GAPDH was mostly present in the supernatant fraction, but it was entirely present in the pellet fraction in the lysate from cells expressing R49A protein. These data imply that the overexpressed R21A mutant protein is a better chaperone and R49A is a weak chaperone relative to Wt protein in CHO cells.

R21A mutant protein is a better antiapoptotic protein

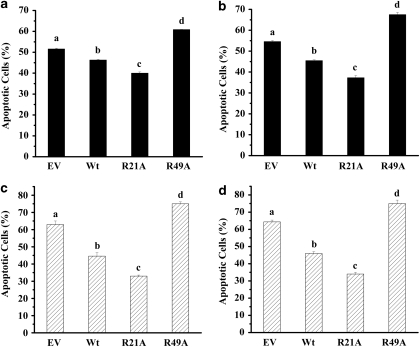

We have previously shown that the R21A mutation in human αA-crystallin increases its chaperone function, whereas the R49A mutation decreases this function.29 To determine whether these changes in chaperone function translate into a gain or loss of antiapoptotic function, we measured apoptosis in CHO cell lines incubated with apoptosis-inducing chemicals, staurosporine or etoposide. In dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-treated cells, no apoptosis was observed (data not shown). In EV-transfected cells, ∼52% cells were apoptotic on staurosporine treatment. This percentage increased to ∼60% in the case of R49A mutant protein-overexpressing cells. Apoptosis was inhibited by R21A mutant protein overexpression, and the number of apoptotic cells was 38%, which was 14% lower than EV-transfected cells (Figure 2a). Similar results were observed when apoptosis was induced by 10 μM etoposide. Although cells overexpressing R21A showed nearly 33% reduction in apoptotic cells, cells overexpressing R49A showed a 22% increase in apoptotic cells when compared with EV-transfected cells (Figure 2b). Similar results were obtained in transiently transfected HeLa cells; R21A was better and R49A was worse than Wt in preventing apoptosis induced by either staurosporine (Figure 2c) or etoposide (Figure 2d). These results indicate that R21A has enhanced and R49A has reduced antiapoptotic activity, relative to Wt protein, and that the gain or loss of antiapoptotic function coincides with the chaperone function of αA-crystallin.

Figure 2.

R21A provides better protection against apoptosis. Apoptosis was induced in αA-crystallin overexpressing Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and HeLa cells by either 100 nM staurosporine or 10 μM etoposide. CHO cells were grown to 100% confluency and then treated with 100 nM staurosporine (a) or 10 μM etoposide (b) in 0.01% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 36 h. Similarly HeLa cells were treated with either 100 nM staurosporine (c) or 10 μM etoposide (d) for 24 h. Cells were treated with Hoechst stain to estimate the percentages of apoptotic cells. Bars that do not share a common superscript are statistically significant at P<0.0001. In each case, n=3

Bax translocation to mitochondria is better inhibited by R21A

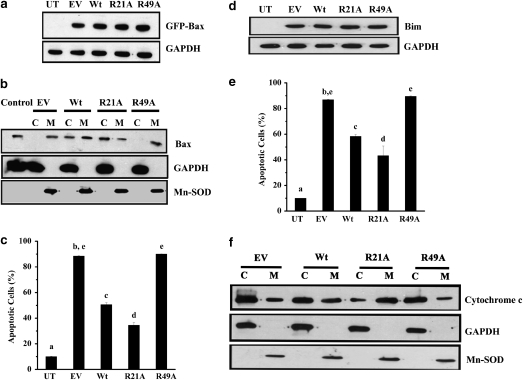

Bax is activated and translocated from the cytosol into mitochondria during apoptosis. Because it has been shown that αA-crystallin directly interacts with Bax,9 we reasoned that such an interaction could affect translocation of Bax into mitochondria during apoptosis and that the R21A mutation may affect this function. To test this hypothesis, we transiently overexpressed green fluorescent protein (GFP)-human Bax in CHO cells (stably transfected with αA-crystallin). Expression of GFP-Bax was confirmed by western blot analysis (Figure 3a). Cells were fractionated into cytosolic and membrane fractions. Mitochondria were found to be enriched in the membrane fraction. In cells overexpressing Wt, Bax was seen in both the cytosolic and membrane fractions (Figure 3b). By contrast, in R21A-overexpressing cells, Bax was mainly present in the cytosolic fraction. Remarkably, in R49A-overexpressing cells, most of Bax was present in the membrane fraction.

Figure 3.

R21A prevents Bax translocation, Bim-induced apoptosis and cytochrome c release in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. (a) Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-Bax was transiently transfected in cell lines overexpressing Wt, R21A or R49A. Untransfected cells (UT) and cells transfected with the empty vector (EV) were used as controls. Total protein was extracted from the cell lysates and 50 μg protein was separated by SDS-PAGE. GFP-Bax was detected by western blot using an anti-Bax antibody. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as the loading control. (b) At 15 h after transfection with GFP-Bax, cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation. Approximately 50 μg of the cytosolic (C) and membrane (M) fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed using an anti-Bax antibody. GAPDH and manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) served as marker proteins for the cytosolic and membrane fractions, respectively. (c) The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by Hoechst staining. (d) Bim was transiently transfected using SuperFect transfection reagent in cell lines to induce apoptosis. Bim was detected by western blotting using an anti-Bim polyclonal antibody. (e) The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by staining the cells with Hoechst stain. (f) Stable cells lines overexpressing Wt, R21A, R49A proteins or empty vector (EV) were incubated at 43°C for 1 h, followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 h. Cell lysates were fractionated into cytosolic (C) and membrane (M) fractions and western blot was performed as mentioned above. Cytochrome c was detected using anti-cytochrome c monoclonal antibody. Cytosolic and membrane proteins were detected as described above. In (c) and (e) results are presented as the mean±S.D. of n=3. Bars that do not share a common superscript are statistically significant at P<0.0001

GFP-Bax expression induced apoptosis in CHO cells; nearly 90% of the cells were apoptotic in GFP-Bax (no αA-crystallin) cells. This percentage was reduced by about 50% in GFP-Bax/αA-crystallin (Wt) cells and further reduced by 35% in GFP-Bax/αA-crystallin (R21A) cells. In contrast, apoptosis increased and reached 90% in GFP-Bax/αA-crystallin (R49A) cells (Figure 3c). Taken together, these results suggest that R21A is better and R49A is worse than Wt in preventing Bax translocation to mitochondria and inhibiting Bax-mediated apoptosis.

R21A provides better protection against Bim-induced apoptosis

Bim is a BH3-only member of the Bcl2 family that functions as a death signal sensor.33 We tested whether R21A mutant protein is able to prevent Bim-induced apoptosis better than the Wt protein by transient transfection of human Bim into CHO cells. Western blot analysis for Bim showed similar levels of expression in all cell lines (Figure 3d). Similar to Bax overexpression, Bim overexpression caused apoptosis in CHO cells. We observed nearly 90% of Bim (no αA-crystallin) cells to be apoptotic; however, apoptosis decreased to 58 and 43% in Bim/αA-crystallin (Wt) and Bim/αA-crystallin (R21A) cells, respectively (Figure 3e). In contrast, nearly 90% of the Bim/αA-crystallin (R49A) cells were apoptotic. Thus, R21A mutant protein was better than Wt protein against Bim-induced apoptosis, and this protection ability was compromised in R49A mutant protein.

R21A offers better protection against cytochrome c release from mitochondria

Exposure of cells to high temperatures causes activation of Bax and subsequent release of cytochrome c from mitochondria.34 We investigated whether αA-crystallin could inhibit or prevent such an effect and whether R21A mutant protein performs that function better than Wt protein. CHO cells were incubated at 43°C for 1 h, followed by incubation at 37°C for another hour. Cells were fractionated into cytosolic and membrane (contains mitochondria) fractions as described above. Western blotting for cytochrome c in the two fractions showed that, in R21A mutant protein-overexpressing cells, cytochrome c was mostly present in the membrane fraction (Figure 3f), whereas it was mostly present in the cytosolic fraction in R49A mutant protein-overexpressing cells. Cytochrome c was observed in the cytosolic fraction of cells transfected with EV, as expected. Cells expressing Wt protein showed nearly equal quantities of cytochrome c in the two fractions. These data further strengthen our notion that R21A mutant protein is a better antiapoptotic agent and that R49A mutant protein is a weaker antiapoptotic relative to Wt.

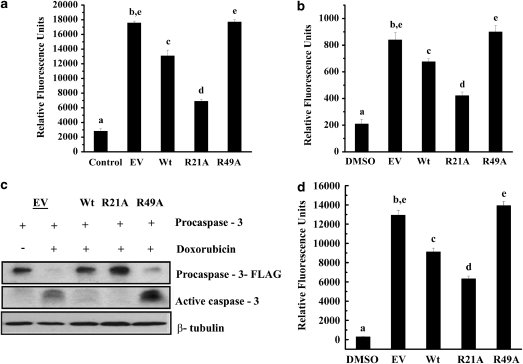

Caspases are less active in R21A mutant protein- overexpressing cells

Previous studies have shown that translocation of Bax from the cytosol to mitochondria induces the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and thereby leads to activation of caspases.35 Because R21A mutant protein-overexpressing cells sequestered most of Bax in the cytosol, we tested whether expression of R21A mutant protein had an effect on the activity of caspases. Apoptosis in CHO cell lines was induced by treatment with 100 nM staurosporine in DMSO. Cells treated with DMSO alone served as a control. We measured caspase-3 and -9 activities in cell lysates using their respective fluorogenic peptide substrates. In Wt cells, caspase-3 and -9 activities were nearly 30 and 20% lower, respectively, when compared with cells transfected with the EV (Figure 4a and b). Cells expressing R21A mutant protein had further reduced activities, by 52 and 50%, respectively. In contrast, activities of both caspases were elevated in cells overexpressing R49A and were comparable to those observed in cells transfected with vector alone.

Figure 4.

R21A prevents activation of caspases. Caspase activities were measured in cells treated with 100 nM staurosporine. (a) For caspase-3 activity measurement, cell lysates were incubated with 50 μM DEVD-AFC for 2 h at 37°C. (b) To determine caspase-9 activity, we used 50 μM LEHD-AFC. Samples were read at 400/505 nm excitation/emission wavelengths. (c) Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were transfected with human procaspase-3 using SuperFect transfection reagent for 48 h followed by treatment with 20 μM doxorubicin to induce apoptosis. Cell lysates (50 μg of protein) were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by western blotting. (d) Cell lysates were incubated with 50 μM DEVD-AFC for 2 h at 37°C to determine caspase-3 activity. Samples were read at 400/505 nm excitation/emission wavelengths. In each treatment, n=3. Bars that do not share a common superscript are statistically significant at P<0.0001

Doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in procaspase-3-overexpressing cells is significantly inhibited by R21A

αB-crystallin inhibits caspase-8-mediated maturation of procaspase-3 to active caspase-3.15 We sought to determine whether the reduced activity of caspase-3 in CHO cell lines (above) is due to αA-crystallin's ability to inhibit maturation of procaspase-3, similar to αB-crystallin. To accomplish this goal, we overexpressed human procaspase-3 in CHO cell lines and in untransfected CHO cells, which also allowed us to investigate whether R21A mutant protein is a better inhibitor of procaspase-3 maturation, mirroring its other antiapoptotic properties. Western blotting confirmed overexpression of procaspase-3 in all cell lines except in untransfected cells; procasapse-3 overexpression did not result in its autocatalytic maturation (data not shown). When cells were treated with 20 μM doxorubicin for 12 h, a clear increase in cleaved caspase-3 was observed. Caspase-3 activation was inhibited by R21A mutant protein and to a lesser extent by Wt protein; however, R49A mutant protein was unable to inhibit caspase-3 activation (Figure 4c). We then evaluated caspase-3 activity in cells; procaspase-3 overexpression alone did not cause an increase in caspase-3 activity, but doxorubicin treatment resulted in massive induction of the enzyme (Figure 4d). Although R21A mutant protein overexpression significantly reduced caspase-3 activity, R49A overexpression was ineffective at reducing the activity. Wt protein inhibited caspase-3 activity, although this effect was lower than that of R21A mutant protein. These results suggest that αA-crystallin inhibits maturation of procaspase-3 and further confirm that R21A mutant protein is better than Wt protein, and that R49A mutant form is a relatively poor inhibitor of procaspase-3 activation.

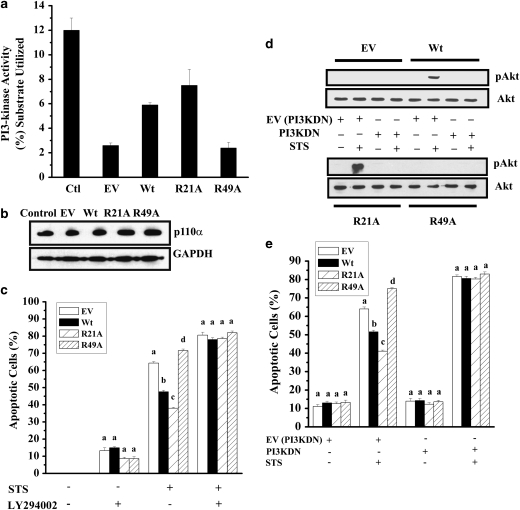

Enhanced antiapoptotic function of R21A mutant protein is due to its higher ability to activate PI3K

Akt is phosphorylated by phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K). Hsp27, a related heat shock protein, has been shown to inhibit apoptosis by activating Akt through PI3K.36 Our studies on the role of αA-crystallin PI3K signaling pathway initially used CHO cells. However, we realized that many of the commercial antibodies to signaling proteins of the PI3K pathway did not work in CHO cells and therefore we used HeLa cells in our subsequent experiments. To determine if αA-crystallin's ability to inhibit apoptosis was due to its effect on PI3K, we measured the PI3K activity in HeLa cells overexpressing Wt and mutant proteins. We found that cells overexpressing R21A had the higher PI3K activity (∼25% higher) than cells overexpressing Wt protein (Figure 5a). Cells overexpressing R49A had activity comparable to cells transfected with the EV. These data suggest that higher PI3K activity in R21A cells is responsible for its better antiapoptotic function.

Figure 5.

Phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K)-mediated cell survival is enhanced by R21A. (a) PI3K activity was measured by a competitive ELISA in HeLa cells after transient transfection (24 h) and 100 nM staurosporine treatment (16 h). (b) PI3K expression was detected by western blotting (50 μg of protein) using an anti-p110α polyclonal antibody. (c) Cells were treated with 20 μM LY294002 for 2 h and then treated with 100 nM staurosporine (STS). (d) Cell lysates (50 μg protein) were subjected to western blotting to detect pAkt using an anti-pAkt antibody and total Akt was detected using anti-Akt antibody. (e) Cell lines were infected with adenovirus containing an EV or a vector containing dominant-negative PI3K, followed by treatment with 100 nM STS to induce apoptosis. In each treatment, n=3. Bars that do not share a common superscript within groups are statistically significant at P<0.0001. EV, empty vector, PI3KDN, dominant-negative PI3K

We then determined if the increased PI3K activity in R21A cells was due to higher expression of the protein by western blotting using an antibody to p110α, the catalytic subunit of PI3K. We found no difference in PI3K protein level in cells overexpressing Wt or the mutant proteins (Figure 5b). Thus, it appears that R21A activates PI3K better than the Wt protein and this ability is lost in R49A.

To confirm whether PI3K is involved in αA-crystallin-mediated inhibition of apoptosis, we incubated cells with a PI3K inhibitor, LY294002. Cells were incubated with or without 20 μM LY294002 for 2 h followed by treatment or nontreatment with 100 nM staurosporine. LY294002 treatment alone increased apoptosis in untransfected CHO cells; these effects were further enhanced in staurosporine-treated cells (Figure 5c). In CHO cell lines, treatment with LY294002 completely abolished the antiapoptotic function of Wt protein. Interestingly, even in R21A cells, the apoptotic rate was similar to that of the Wt cells. R49A showed responses similar to those of the Wt and R21A cells. These results suggest that PI3K activity is required for the antiapoptotic function of αA-crystallin.

To further confirm the involvement of PI3K, we transduced our cell lines with dominant-negative PI3K adenovirus or empty adenovirus to block the activity of PI3K specifically. Cells were then treated with staurosporine to induce apoptosis. The dominant-negative vector has been shown to inhibit PI3K robustly.37 We confirmed this effect by measuring Akt phosphorylation at serine 473 using western blot analysis. It was completely blocked by expression of the dominant-negative mutant (Figure 5d), but was unaffected in cells transduced with EV. Expression of the dominant-negative mutant alone caused apoptosis (Figure 5e); this effect was exaggerated by staurosporine treatment. In all cell lines, expression of the dominant-negative mutant resulted in a failure to protect against staurosporine-induced apoptosis; however, transduction of the empty adenovirus vector did not change the gain or loss of antiapoptotic function in R21A and R49A. These results suggest that αA-crystallin inhibits apoptosis through activation of PI3K.

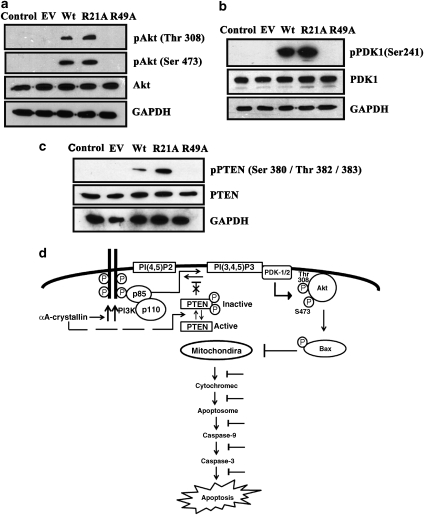

Phosphorylation of Akt, PDK1 and PTEN is elevated by R21A

The above results suggested that αA-crystallin inhibits the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis through activation of the PI3K-mediated signaling pathway. It is well established that PI3K-mediated activation Akt promotes cell survival.38 It has been shown that human αA-crystallin activates the Akt survival pathway to counteract UVA-induced apoptosis.17 Therefore, we investigated the downstream signaling of the PI3K pathway.

Phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-triphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3) produced from PI3K activity recruits Akt to the plasma membrane. At the plasma membrane, Akt is phosphorylated at Thr308 and Ser473 by PDK1 and PDK2, respectively.34, 39 We analyzed Akt phosphorylation in CHO cell lines after treatment with 100 nM staurosporine for 3 h. Robust Akt phosphorylation (at Ser473) was observed in R21A mutant protein-overexpressing cells (data not shown), but this response was muted in Wt protein-overexpressing cells and was completely absent in both R49A protein-overexpressing cells and in cells transfected with the EV. Experiments on HeLa cells allowed us to determine if phosphorylation occurs on Thr308 as well, as commercial antibodies to Thr308 phosphorylation did not work with CHO cells. In 100 nM staurosporine-treated HeLa cells, Akt phosphorylation at both Thr308 and Ser473 was elevated in R21A-overexpressing cells than in cells overexpressing Wt protein, but such phosphorylation was completely absent in R49A-overexpressing cells and in EV-transfected cells (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

R21A induces Akt, PDK1 and phosphatase tensin homologue (PTEN) phosphorylation. HeLa cells overexpressing human Wt, R21A or R49A αA-crystallin were treated with 100 nM staurosporine or 0.01% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 12 h. Cell lysates (100 μg of protein each) were subjected to western blot analysis. (a) pAkt levels at Thr308 and Ser473 using an anti-pAkt (Thr308) and anti-pAkt (Ser473) polyclonal antibodies, respectively. Total Akt was detected using an anti-Akt polyclonal antibody. (b) Detection of pPDK1 and total PDK1 using an anti-pPDK1(Ser241) and anti-PDK1 polyclonal antibodies, respectively. (c) Detection of pPTEN (Ser380/Thr382/383) and total PTEN using an anti-pPTEN polyclonal and an anti-PTEN polyclonal antibody. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as loading control. (d) A conceptual mechanism by which αA-crystallin inhibits apoptosis by the PI3K/PDK1/Akt pathway: αA-crystallin inhibits apoptosis by the PI3K/PDK1/Akt pathway. αA-crystallin enhances the PI3K activity and decreases PTEN activity through phosphorylation (dashed line) leading to increased production and retention of phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-triphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3). This favors recruitment of Akt to the plasma membrane allowing its phosphorylation at Thr308 and Ser473 by PDK1/2. Activated Akt then detaches from the membrane and inactivates Bax by phosphorylation. Inactive Bax is unable to translocate to mitochondria, which prevents cytochrome c release into the cytoplasm. The ensuing inhibition of caspase activation leads to inhibition of apoptosis

One of the upstream kinases that activates Akt is PDK1.36 We investigated if αA-crystallin activates Akt through activation of PDK1. In HeLa cells treated with 100 nM staurosporine, we found PDK1 to be phosphorylated at Ser241 in R21A-expressing cells (Figure 6b). This response, although seen with cells overexpressing Wt protein, was less apparent. However, PDK1 phosphorylation was not seen in either R49A protein overexpressing cells or in cells transfected with the EV.

Next we studied the phosphorylation status of phosphatase tensin homologue (PTEN) in HeLa cells. PTEN is a dual lipid and protein phosphatase. PTEN dephosphorylates PI(3,4)P and PI(3,4,5)P acting as an antagonist of PI3K effects. It is known that phosphorylation of PTEN at the C-terminal tail suppresses the activity of PTEN.40 We found increased phosphorylation of PTEN in R21A-overexpressing cells when compared with cells overexpressing Wt (Figure 6c). R49A overexpressing cells and cells with EV did not show PTEN phosphorylation. Together these results show that the increased ability of R21A protein to protect cells from apoptosis is due to reduced PTEN activity, thus further promoting activation of Akt through PDK1 phosphorylation.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was twofold: (1) to determine if the antiapoptotic function of αA-crystallin is related to its chaperone function and (2) to evaluate whether argpyrimidine-modifiable arginine residues that enhance or reduce the chaperone function dictate the antiapoptotic function. We have previously shown that MGO, a metabolic dicarbonyl compound, reacts with Hsp27 and makes it a better antiapoptotic protein.41 We also showed that MGO reacts with specific arginine residues in αA-crystallin and converts them to argpyrimidine.24 We have found that such conversion at R21 makes αA-crystallin a better chaperone and conversion at R49 makes it a poor chaperone. We then showed that removal of the positive charge by substitution with alanine at these sites had the same effect on protein function as argpyrimidine modification.29 The finding that the chaperone function could be modulated by point mutations of specific arginine residues enabled us to undertake this study. The principal findings of this study are that the enhanced chaperone function of αA-crystallin strictly correlates with enhanced protection against the intrinsic apoptosis pathway and that loss of chaperone function has the opposite effect. The improvement in antiapoptotic function occurred through (1) increased PI3K activity and enhanced Akt phosphorylation by PDK1, (2) increased phosphorylation of PTEN, (3) increased inhibition of Bax translocation to mitochondria and Bim-mediated apoptosis, (4) decreased cytochrome c release from mitochondria and (5) increased inhibition of caspase-9 activity followed by inhibition of capase-3 activation. These data clearly suggest that the chaperone function is directly related and possibly essential for the antiapoptotic function of αA-crystallin.

Bcl2 family proteins control mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP).42 Activation of Bax and/or Bak is required for MOMP; however, mechanisms by which Bax and Bak become activated are still being studied. The direct activation model suggests that BH3-only proteins, such as, Bim and tBid, can bind directly to Bax and Bak and promote their activation.43 The indirect activation model suggests that Bim binds to antiapoptotic Bcl2 proteins and displaces Bax, which subsequently results in Bax activation.44, 45 According to the first model, interaction with Bim results in structural perturbation at the N- and C termini of Bax, which then translocates to mitochondria, oligomerizes on the mitochondrial outer membrane and causes MOMP.46 We showed that overexpression of R21A is able to inhibit Bax translocation. This finding suggests that R21A could interfere with Bim binding to Bax, or that it might interact directly with structurally perturbed Bax through its chaperone property, thereby blocking its translocation and oligomerization on the mitochondrial outer membrane. Along these lines, it has been shown that heat treatment in a cell-free system induces oligomerization and activation of Bax47 and αA-crystallin has been shown to bind thermally destabilized proteins.48 Thus, it is possible that αA-crystallin can bind to structurally perturbed Bax during its activation by Bim.

When we overexpressed BimEL in CHO cells, it induced spontaneous apoptosis, as expected.49 The R21A mutant was effective, unlike R49A mutant, at inhibiting such apoptosis. This finding suggests that R21A interacts directly with and sequesters Bim or that it binds to Bax and prevents Bim-mediated activation of Bax. Further studies are needed to test these possibilities.

The lower activity of caspase-3 in R21A cells relative to R49A cells could be because of either a direct interaction of αA-crystallin with procaspase-3 or indirect effects through inhibition of Bax translocation to mitochondria. The former possibility is supported by observations that αB-crystallin and Hsp27, two proteins related to αA-crystallin, interact directly with procaspase-3 and inhibit its activation.15, 50 During apoptosis, caspase-9 activates procaspase-3 through apoptosome formation. It is likely that αA-crystallin, similar to Hsp27, might bind to the propeptide and inhibit the maturation process. Work is underway to investigate this possibility.

There seems to be another level, either Bax-independent or -dependent, at which αA-crystallin inhibits apoptosis. PI3K leads to stimulation of PI-dependent kinase through PIP3, which increases Akt phosphorylation and, subsequently, activity of Akt.36 We found that the PI3K activity was elevated in R21A cells when compared with Wt cells and was diminished in R49A cells. However, we did not observe any significant difference in the expression level of PI3K. Exactly how αA-crystallin activates PI3K is uncertain at this time, but our data point to the possibility that it could do so by enhancing the phosphorylation of PI3K. Our study data show that when PI3K is inhibited either by LY294002 or by a dominant-negative mutation, the antiapoptotic function of αA-crystallin, including that of the R21A mutant, is completely abolished. These observations imply that PI3K/Akt pathway activation is involved in αA-crystallin's antiapoptotic function.

A previous study showed that αA-crystallin activates Akt by phosphorylation at Ser473.51 Our study showed that in addition to Ser473, αA-crystallin promotes phosphorylation at Thr308 and that R21A is better than Wt in promotion of phosphorylation at these two sites. Our study also showed that αA-crystallin-mediated Thr308 phosphorylation is due to an increase in phosphorylation of PDK1 (at Ser241). The promotion of Akt phosphorylation by R21A could lead to inhibition of Bax translocation to mitochondria, as phosphorylated Akt has been shown to induce Bax phosphorylation, which leads to its sequestration and heterodimerization with the antiapoptotic Bcl2 family members, Mcl-1 and Bcl-XL.52 We cannot rule out other mechanisms by which Akt phosphorylation could inhibit apoptosis, such as phosphorylation and inhibition of proapoptotic mediators, such as Bad and caspase-9.53, 54 On the basis of our results, we propose that αA-crystallin functions as an antiapoptotic protein by increasing PI3K activity and decreasing the PTEN activity (Figure 6d).

We believe that the findings of this study significantly impact on our understanding of the role of α-crystallin in diseases. In the human lens the chaperone function of α-crystallin decreases during aging and cataract formation.55 On the basis of the results in this study, we believe that such a decrease in the chaperone function could reduce its antiapoptotic function as well. Whether αA-crystallin content decreases in the epithelial cells of cataractous lenses is not clear, but if it does, it could render lens epithelial cells more susceptible to apoptosis. In fact, in human and experimental cataracts, lens epithelial cell apoptosis has been observed.56 Although such apoptosis is not extensive, it may be sufficient to cause damage to the lens. Lens epithelial cells synthesize high amounts of α-crystallin. Whether α-crystallin expression protects epithelial cells from apoptosis in vivo should be investigated. Previous work using α-crystallin knockout animals suggests that lens epithelial cells become genomically unstable and undergo enhanced apoptosis in the absence of α-crystallin.57 A recent study showed that differentiated fiber cells undergo apoptosis in the absence of α-crystallin in the mouse lens.16

The antiapoptotic function of α-crystallin may also be important in other tissues. In the ischemic heart, phosphorylated αB-crystallin is translocated to mitochondria where it stabilizes mitochondrial membrane potential and inhibits apoptosis.58 α-Crystallin has been shown to protect cancer cells from apoptosis in glioblastoma59 and retinoblastoma.60 A recent study showed that αB-crystallin is an oncoprotein that is highly expressed in breast carcinomas and its expression independently predicts survival in this disease.61 α-Crystallin appears to be important for the prevention of apoptosis in vascular cells as well. Our previous study using human umbilical vein endothelial cells showed that hyperglycemia-induced apoptosis can be inhibited by overexpression of αB-crystallin.62 In addition, we have previously shown that apoptosis of retinal capillary pericytes, which is associated with a decrease in αB-crystallin content, can be prevented by the overexpression of αB-crystallin.63 A recent report shows that αB-crystallin promotes tumor angiogenesis by increasing endothelial cell survival during tube morphogenesis.64 Thus, it is apparent that αA- and αB-crystallins are important in the prevention of apoptosis in many different tissues.

In summary, we have shown in this study that the antiapoptotic property of αA-crystallin is directly related to its chaperone function. The fact that modification of R21 to argpyrimidine by a metabolic dicarbonyl MGO had similar effects on the chaperone function of αA-crystallin, combined with the present finding that the R21A mutant protein is superior to Wt protein in terms of antiapoptotic functions, suggests that low cellular concentrations of MGO may help cells to cope with stress by preventing protein aggregation and apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Cloning

Wt αA-crystallin cDNA was excised from pCMS-EGFP plasmid using NheI and XbaI and inserted into pcDNA 3.1(−) vector. R21A cDNA was generated by PCR using forward primer 5′-CTGCAGAATTCATGGACGTGACCTCCAGCAC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CCCAAGCTTAGGACGAGGGAGCCGAGGT-3′ and the R21A-pET23d plasmid as template. The PCR product was then inserted into pcDNA3.1(−) vector between ECORI and HindIII restriction sites. R49A cDNA was amplified using the R49A-pET23d plasmid as template by PCR using the above primers and cloned with the same restriction sites as described for R21A.

Cell culture

Chinese hamster ovary cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and HeLa cells were used for the study. Cells were transfected with either empty pcDNA3.1(−) vector or vector coding for Wt, R21A or R49A αA-crystallin. Transient transfections were performed in HeLa cells using SuperFect transfection reagent. HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. CHO cells were used to establish stable cell lines expressing αA-crystallin using Lipofectamine, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Cells were cultured in Ham's F12 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transfected cells were then selected by treatment with G418 (400 μg/ml). Colonies were isolated and individual colonies were expanded. Each colony was derived from a single cell. Cell lysates were prepared from 1 × 106 cells using mammalian protein extraction reagent (MPER) reagent (Pierce, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The expression of αA-crystallin in cell lines was analyzed by western blot using an αA-crystallin polyclonal antibody (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The expression levels of αA-crystallin in CHO cell lines were calculated by comparison with densitometric values obtained from varied concentrations of purified human αA-crystallin. Monoclonal mouse antiGAPDH antibody (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) was used to detect GAPDH, which served as a loading control.

GAPDH aggregation assay

Stable cell lines were grown to 100% confluence in Ham's F12 media containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Cell lysates were prepared from 10 × 106 cells using MPER reagent and were incubated at 55°C for 3 h for protein aggregation. Soluble and insoluble fractions were separated as described by Hayes et al.65 and 10 μg protein was separated by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed and GAPDH was detected using antiGAPDH monoclonal antibody (Chemicon International). Purified GAPDH from rabbit muscle (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was used as the positive control.

Transient transfection of CHO cell lines with human GFP-Bax, BimEL and procaspase-3

GFP-Bax and Bim, both in pcDNA3(−) vector (Shigemi Matsuyama), were transiently transfected into CHO cell lines (each 7 × 105 cells) using SuperFect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). To generate full-length caspase-3-FLAG (FL-caspase-3-FLAG), we amplified pQE31 plasmid containing the human caspase-3 cDNA66 using the forward primer 5′-GGATCCGAATTC GCCACCATGTCTGGAATATCC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-ATCCTCGAGTGTCGACGCGTGATAAAAATAGAG-3′. The DNA was cloned into the BamHI and SalI sites of the mammalian pCMV-(4B)-FLAG expression vector (Startagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) generating the C-terminal FLAG epitope-tagged caspase-3. FL-caspase-3-FLAG clones were confirmed by sequencing and protein expression using the anti-Flag antibody (Clone M2; Sigma). Procaspase-3 in pCMV vector (Assay Designs) was transiently transfected as described above. In these experiments, cells transfected with or without EV served as controls. The expression of the proteins in transfected cells was confirmed by western blotting (see below).

Western blot analysis

Cell lysis was performed for Bax, Bim by incubation in a cell lysis buffer obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA; catalog no. 9803) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Cell lysis for procaspase-3 was performed as previously reported.50 Cell lysates were passed through a 26-gauge needle several times in the presence of 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 5 μl/ml protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma; catalog no. P8340). Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Samples corresponding to 50–100 μg protein were electrophoresed through a 15% SDS-PAGE gel and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane for 80 min at 100 V. Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 buffer for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was then incubated with one of the following primary antibodies: αA-crystallin (polyclonal; Assay Designs), Bax, caspase-3, pAkt (Ser473), pAkt (Thr308), Akt, pPDK1 (Ser241), PDK1, pPTEN (Ser380/Thr382/383), PTEN, p110α (all polyclonal; Cell Signaling), BimEL (polyclonal; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA), cytochrome c (monoclonal; Assay Designs), at a 1 : 1000 dilution overnight at 4°C. A monoclonal antibody for GAPDH was added at a 1 : 10 000 dilution and incubated overnight at 4°C. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse secondary antibody was used at a 1 : 5000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was detected using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce).

Cell fractionation

Subcellular fractionation to determine Bax translocation was performed using the Qproteome Cell Compartment Kit (Qiagen). Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were separated according to the manufacturer's instructions. Manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD; mitochondrial marker protein) was detected using an anti-MnSOD polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Cytosolic marker protein GAPDH was detected by anti-GAPDH antibody.

Induction of apoptosis

Stable cell lines were grown to 100% confluence in Ham's F12 media containing 10% fetal bovine serum in the presence of 400 μg/ml G418. Cells were then placed in media containing 0.01% DMSO (control) or DMSO containing 100 nM staurosporine or 10 μM etoposide for 24–36 h or 20 μM doxorubicin for 12 h. After treatment, all samples were collected and analyzed for apoptosis. The percentage of apoptotic and viable cells was measured by Hoechst staining. A total of 300 cells were counted. The percentage of apoptotic cells and viable cells relative to the total number of cells was calculated.

Caspase-3 and -9 activities

Cells were collected and lysed as described above. Cell lysates were incubated in a black microwell plate for 2 h at 37°C with 50 μl of either 50 mM DEVD-AFC in 10% glycerol, 50 mM 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid (pH 7.0), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol to measure capase-3 activity or 50 mM LEHD-AFC in the same buffer to measure caspase-9 activity. Samples were read at 400/505 nm excitation/emission wavelengths using a Spectramax Gemini XPS spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

PI3K activity assay

The activity of PI3K was determined using the PI3K activity ELISA Kit (Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City, UT, USA). HeLa cells were transiently transfected with either EV or vector harboring Wt, R21A and R49A mutant of human αA-crystallin for 24 h. Cells were treated with 100 nm staurosporine for 16 h. Cell lysate was used for immunoprecipitation of PI3K using an anti-PI3K antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Temecula, CA, USA) and a competitive ELISA was used to measure PI3K activity following the manufacturer's protocol.

Blocking of PI3K activity in CHO cell lines

For inhibition of PI3K activity, CHO cells were grown to 100% confluence in Ham's F12 media and incubated with or without 20 μM LY294002 for 2 h. Cells without the inhibitor served as the control. Following the treatment, cells were incubated with or without 100 nM staurosporine for 36 h. Cells were stained with Hoechst stain to measure apoptosis as described above. To block PI3K activity in cells, we transduced cells with an adenovirus harboring a dominant negative form of PI3K (PI3K DN-PI3K).67 CHO cell lines were plated overnight at a density of 1 × 105 cells per 2 ml in Ham's F12 media in 6- or 12-well plates and were then infected overnight with 2.5 × 1010 PFU per ml with either an empty adenovirus or adenovirus carrying DN-PI3K. The transduction efficiency was previously established to be greater than 95%.67 Cells were washed once with PBS, and were then cultured for an additional 24 h in 2 ml of Ham's F12 medium containing 100 nM staurosporine.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean±S.D. Statistical significance among groups was analyzed by ANOVA followed by the Fisher's least significant difference test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH Grants R01EY-016219, R01EY-09912 (RHN), P30EY11373 (Visual Sciences Research Center of CWRU), R01CA102074 (DD), R01HL075040-01 and NSF-MCB 0542244 (AID), RO1AG031903 (SM), by a Senior Scientific Investigator Award from Research to Prevent Blindness foundation of New York to RHN and by the Ohio Lions Eye Research Foundation.

Glossary

- sHSPs

small heat shock proteins

- MGO

methylglyoxal

- MnSOD

manganese superoxide dismutase

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3 kinase

- PI(3,4,5)P3

phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-triphosphate

- PDK1/2

PI(3,4,5)P-dependent kinase 1/2

- PTEN

phosphatase tensin homologue

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- PI3K DN

PI3K dominant-negative

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- AFC

aminofluoromethyl coumarin

- MPER

mammalian protein extraction reagent

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bloemendal H. Lens proteins. CRC Crit Rev Biochem. 1982;12:1–38. doi: 10.3109/10409238209105849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ouderaa FJ, de Jong WW, Bloemendal H. The amino-acid sequence of the alphaA2 chain of bovine alpha-crystallin. Eur J Biochem. 1973;39:207–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan AN, Nagineni CN, Bhat SP. alpha A-crystallin is expressed in non-ocular tissues. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23337–23341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong WW, Leunissen JA, Voorter CE. Evolution of the alpha-crystallin/small heat-shock protein family. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:103–126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a039992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama A, Frohli E, Schafer R, Klemenz R. Alpha B-crystallin expression in mouse NIH 3T3 fibroblasts: glucocorticoid responsiveness and involvement in thermal protection. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1824–1835. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta S, Hohman TC, Carper D. Hypertonic stress induces alpha B-crystallin expression. Exp Eye Res. 1992;54:461–470. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(92)90058-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andley UP, Patel HC, Xi JH. The R116C mutation in alpha A-crystallin diminishes its protective ability against stress-induced lens epithelial cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10178–10186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109211200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andley UP, Song Z, Wawrousek EF, Fleming TP, Bassnett S. Differential protective activity of alpha A- and alphaB-crystallin in lens epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36823–36831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao YW, Liu JP, Xiang H, Li DW. Human alphaA- and alphaB-crystallins bind to Bax and Bcl-X(S) to sequester their translocation during staurosporine-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:512–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlen P, Schulze-Osthoff K, Arrigo AP. Small stress proteins as novel regulators of apoptosis. Heat shock protein 27 blocks Fas/APO-1- and staurosporine-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16510–16514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao XW, Green LM, Gridley DS. Evaluation of polysaccharopeptide effects against C6 glioma in combination with radiation. Oncology. 2001;61:243–253. doi: 10.1159/000055381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Li J, Tao Y, Xiao X. Small heat shock protein alphaB-crystallin binds to p53 to sequester its translocation to mitochondria during hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamradt MC, Lu M, Werner ME, Kwan T, Chen F, Strohecker A, et al. The small heat shock protein alpha B-crystallin is a novel inhibitor of TRAIL-induced apoptosis that suppresses the activation of caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11059–11066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamradt MC, Chen F, Sam S, Cryns VL. The small heat shock protein alpha B-crystallin negatively regulates apoptosis during myogenic differentiation by inhibiting caspase-3 activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38731–38736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamradt MC, Chen F, Cryns VL. The small heat shock protein alpha B-crystallin negatively regulates cytochrome c- and caspase-8-dependent activation of caspase-3 by inhibiting its autoproteolytic maturation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16059–16063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozov V, Wawrousek EF. Caspase-dependent secondary lens fiber cell disintegration in alphaA-/alphaB-crystallin double-knockout mice. Development. 2006;133:813–821. doi: 10.1242/dev.02262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JP, Schlosser R, Ma WY, Dong Z, Feng H, Liu L, et al. Human alphaA- and alphaB-crystallins prevent UVA-induced apoptosis through regulation of PKCalpha, RAF/MEK/ERK and AKT signaling pathways. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison LE, Hoover HE, Thuerauf DJ, Glembotski CC. Mimicking phosphorylation of alphaB-crystallin on serine-59 is necessary and sufficient to provide maximal protection of cardiac myocytes from apoptosis. Circ Res. 2003;92:203–211. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000052989.83995.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz J. Alpha-crystallin can function as a molecular chaperone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10449–10453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloemendal H, de Jong W, Jaenicke R, Lubsen NH, Slingsby C, Tardieu A. Ageing and vision: structure, stability and function of lens crystallins. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004;86:407–485. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das KP, Choo-Smith LP, Petrash JM, Surewicz WK. Insight into the secondary structure of non-native proteins bound to a molecular chaperone alpha-crystallin. An isotope-edited infrared spectroscopic study. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33209–33212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derham BK, Harding JJ. Effect of aging on the chaperone-like function of human alpha-crystallin assessed by three methods. Biochem J. 1997;328 (Part 3:763–768. doi: 10.1042/bj3280763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puttaiah S, Biswas A, Staniszewska M, Nagaraj RH. Methylglyoxal inhibits glycation-mediated loss in chaperone function and synthesis of pentosidine in alpha-crystallin. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:914–921. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj RH, Oya-Ito T, Padayatti PS, Kumar R, Mehta S, West K, et al. Enhancement of chaperone function of alpha-crystallin by methylglyoxal modification. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2003;42:10746–10755. doi: 10.1021/bi034541n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar MS, Reddy PY, Kumar PA, Surolia I, Reddy GB. Effect of dicarbonyl-induced browning on alpha-crystallin chaperone-like activity: physiological significance and caveats of in vitro aggregation assays. Biochem J. 2004;379:273–282. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haik GM, Jr, Lo TW, Thornalley PJ. Methylglyoxal concentration and glyoxalase activities in the human lens. Exp Eye Res. 1994;59:497–500. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N, Thornalley PJ, Dawczynski J, Franke S, Strobel J, Stein G, et al. Methylglyoxal-derived hydroimidazolone advanced glycation end-products of human lens proteins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:5287–5292. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padayatti PS, Ng AS, Uchida K, Glomb MA, Nagaraj RH. Argpyrimidine, a blue fluorophore in human lens proteins: high levels in brunescent cataractous lenses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1299–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas A, Miller A, Oya-Ito T, Santhoshkumar P, Bhat M, Nagaraj RH. Effect of site-directed mutagenesis of methylglyoxal-modifiable arginine residues on the structure and chaperone function of human alphaA-crystallin. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2006;45:4569–4577. doi: 10.1021/bi052574s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloyan A, Sanbe A, Osinska H, Westfall M, Robinson D, Imahashi K, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis underlie the pathogenic process in alpha-B-crystallin desmin-related cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;112:3451–3461. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.572552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay DS, Andley UP, Shiels A. Cell death triggered by a novel mutation in the alphaA-crystallin gene underlies autosomal dominant cataract linked to chromosome 21q. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:784–793. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Li C, Lu Q, Su T, Ke T, Li DW, et al. Cataract mutation P20S of alphaB-crystallin impairs chaperone activity of alphaA-crystallin and induces apoptosis of human lens epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1782:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthalakath H, Strasser A. Keeping killers on a tight leash: transcriptional and post-translational control of the pro-apoptotic activity of BH3-only proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:505–512. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens L, Anderson K, Stokoe D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Painter GF, Holmes AB, et al. Protein kinase B kinases that mediate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent activation of protein kinase B. Science. 1998;279:710–714. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurgensmeier JM, Xie Z, Deveraux Q, Ellerby L, Bredesen D, Reed JC. Bax directly induces release of cytochrome c from isolated mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4997–5002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaki M, Oshimura M, Ito H. PI3K–Akt pathway: its functions and alterations in human cancer. Apoptosis. 2004;9:667–676. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000045801.15585.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K, Wang H, Krebs TL, Danielpour D. Novel roles of Akt and mTOR in suppressing TGF-beta/ALK5-mediated Smad3 activation. EMBO J. 2006;25:58–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi DR, James SR, Downes CP, Holmes AB, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, et al. Characterization of a 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase which phosphorylates and activates protein kinase Balpha. Curr Biol. 1997;7:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez F, Grossman SR, Takahashi Y, Rokas MV, Nakamura N, Sellers WR. Phosphorylation of the PTEN tail acts as an inhibitory switch by preventing its recruitment into a protein complex. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48627–48630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oya-Ito T, Liu BF, Nagaraj RH. Effect of methylglyoxal modification and phosphorylation on the chaperone and anti-apoptotic properties of heat shock protein 27. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:279–291. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science. 2004;305:626–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1099320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavathiotis E, Suzuki M, Davis ML, Pitter K, Bird GH, Katz SG, et al. BAX activation is initiated at a novel interaction site. Nature. 2008;455:1076–1081. doi: 10.1038/nature07396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letai A, Bassik MC, Walensky LD, Sorcinelli MD, Weiler S, Korsmeyer SJ. Distinct BH3 domains either sensitize or activate mitochondrial apoptosis, serving as prototype cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, Chipuk JE, Bonzon C, Sullivan BA, Green DR, et al. BH3 domains of BH3-only proteins differentially regulate Bax-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization both directly and indirectly. Mol Cell. 2005;17:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalier L, Cartron PF, Juin P, Nedelkina S, Manon S, Bechinger B, et al. Bax activation and mitochondrial insertion during apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:887–896. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0749-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliari LJ, Kuwana T, Bonzon C, Newmeyer DD, Tu S, Beere HM, et al. The multidomain proapoptotic molecules Bax and Bak are directly activated by heat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17975–17980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506712102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz J. Alpha-crystallin. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00278-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Paschen SA, Heger K, Wilfling F, Frankenberg T, Bauerschmitt H, et al. BimS-induced apoptosis requires mitochondrial localization but not interaction with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:625–636. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss OH, Batra S, Kolattukudy SJ, Gonzalez-Mejia ME, Smith JB, Doseff AI. Binding of caspase-3 prodomain to heat shock protein 27 regulates monocyte apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-3 proteolytic activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25088–25099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JP, Schlosser R, Ma WY, Dong Z, Feng H, Lui L, et al. Human alphaA- and alphaB-crystallins prevent UVA-induced apoptosis through regulation of PKCalpha, RAF/MEK/ERK and AKT signaling pathways. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:393–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardai SJ, Hildeman DA, Frankel SK, Whitlock BB, Frasch SC, Borregaard N, et al. Phosphorylation of Bax Ser184 by Akt regulates its activity and apoptosis in neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21085–21095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A, Datta SR, Greenberg ME. Transcription-dependent and -independent control of neuronal survival by the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:297–305. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC, Toker A. Direct regulation of the Akt proto-oncogene product by phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate. Science. 1997;275:665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derham BK, Harding JJ. Alpha-crystallin as a molecular chaperone. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:463–509. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q, Liu JP, Li DW. Apoptosis in lens development and pathology. Differentiation. 2006;74:195–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andley UP. The lens epithelium: focus on the expression and function of the alpha-crystallin chaperones. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker R, Glassy MS, Gude N, Sussman MA, Gottlieb RA, Glembotski CC. Kinetics of the translocation and phosphorylation of {alpha}B-crystallin in mouse heart mitochondria during ex vivo ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1633–H1642. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01227.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegh AH, Kesari S, Mahoney JE, Jenq HT, Forloney KL, Protopopov A, et al. Bcl2L12-mediated inhibition of effector caspase-3 and caspase-7 via distinct mechanisms in glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10703–10708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712034105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kase S, Parikh JG, Rao NA. Expression of alpha-crystallin in retinoblastoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:187–192. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyano JV, Evans JR, Chen F, Lu M, Werner ME, Yehiely F, et al. AlphaB-crystallin is a novel oncoprotein that predicts poor clinical outcome in breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:261–270. doi: 10.1172/JCI25888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj RH, Oya-Ito T, Bhat M, Liu B. Dicarbonyl stress and apoptosis of vascular cells: prevention by alphaB-crystallin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1043:158–165. doi: 10.1196/annals.1333.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Bhat M, Padival AK, Smith DG, Nagaraj RH. Effect of dicarbonyl modification of fibronectin on retinal capillary pericytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1983–1995. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimberg A, Rylova S, Dieterich LC, Olsson AK, Schiller P, Wikner C, et al. alphaB-crystallin promotes tumor angiogenesis by increasing vascular survival during tube morphogenesis. Blood. 2008;111:2015–2023. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes VH, Devlin G, Quinlan RA. Truncation of alphaB-crystallin by the myopathy-causing Q151X mutation significantly destabilizes the protein leading to aggregate formation in transfected cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10500–10512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706453200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss OH, Kim S, Wewers MD, Doseff AI. Regulation of monocyte apoptosis by the protein kinase Cdelta-dependent phosphorylation of caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17371–17379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K, Cornelius SC, Reiss M, Danielpour D. Insulin-like growth factor-I inhibits transcriptional responses of transforming growth factor-beta by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent suppression of the activation of Smad3 but not Smad2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38342–38351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]