Abstract

The ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) is a family of receptors that allow cells to interact with the extracellular environment and transduce signals to the nucleus that promote differentiation, migration and proliferation necessary for proper heart morphogenesis and function. This review focuses on the role of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases, and their importance in proper heart morphogenesis, as well as their role in maintenance and function of the adult heart. Studies from transgenic mouse models have shown the importance of ErbB receptors in heart development, and provide insight into potential future therapeutic targets to help reduce congenital heart defect (CHD) mortality rates and prevent disease in adults. Cancer therapeutics have also shed light to the ErbB receptors and signaling network, as undesired side effects have demonstrated their importance in adult cardiomyocytes and prevention of cardiomyopathies. This review will discuss ErbB receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) in heart development and disease including valve formation and partitioning of a four-chambered heart as well as cardiotoxicity when ErbB signaling is attenuated in adults.

Introduction

1.1

The first organ to form during embryogenesis is the heart. The process of how such critical structures form from limited progenitor cells is one of the most intricate stories in developmental biology. The complexity of heart development is reflected in the fact that congenital heart defects (CHD) are the most common malformations diagnosed in newborns. Heart development is a highly regulated process orchestrated by signaling events triggered by binding of ligands such as growth factors and extracellular matrix components to specific receptors. This sequential cascade of signaling events ultimately promotes differentiation, migration and proliferation of cells that lead to proper embryonic heart development. It is beyond the scope of this review to discuss all of the complex signaling events involved in heart development, which are described elsewhere [1-7]. This review focuses on the role of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases, and their importance in proper heart morphogenesis, as well as their role in maintenance and function of the adult heart. Nevertheless, it is important to understand that the complexity of the signaling network does not occur in an isolated manner. In particular, morphogenesis of the heart occurs in a complex extracellular environment, and since it is the first organ to form, it is highly vulnerable to disruptions in developmental signaling. This is evidenced by the high incidence of CHD that contribute significantly to fetal and childhood mortality [8]. The incidence of CHD in the United States varies between 4 and 10 per 1000 live births [9], of which an estimated 2.3 per 1000 live births require invasive treatment or result in death in the first year of life [10]. Additionally, according to the national vital statistics system, as of 2005, greater than 29% of infants who die of a birth defect have a congenital heart defect [9]. Although mortality rates from congenital heart defects have been decreasing for over 30 years, adult cardiovascular (CV) disease has been increasing, and it kills over one million persons a year. As we believe adult CV disease has origins in development, the understanding of how ErbB receptors regulate heart morphogenesis will ultimately improve therapeutic strategies to repair congenital heart defects and prevent disease in adults.

1.2

The ErbB receptor family consists of four type 1 tyrosine kinase transmembrane glycoproteins that are structurally homologous and share highly conserved sequences [1]. This family includes the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (EGFR), also known as ErbB1, or HER1, the ErbB2 (also known as HER2), the ErbB3 (HER3), and the ErbB4 (HER4), named after their ligands, heregulins, also known as neuregulins or NRGs. ErbB ligands include EGF-like ligands as well as neuregulins (NRGs) 1 through 4, TGFα, amphiregulin, heparin-binding EGF-likel growth factor (HB-EGF), betacellulin, epiregulin, and epigen [1, 11]. While the EGF-like ligands (EGF, TGFα, HB-EGF, betacellulin, epiregulin, epigen) bind to the ErbB1 receptor, NRG-1-4 bind to ErbB3 and ErbB4. Additional ligands for ErbB4 include HB-EGF, epiregulin and betacellulin [12, 13], while ErbB3 is also able to bind TGFα and EGF [14]. The ErbB2 receptor is considered an orphan receptor since no known ligands bind to its extracellular domain (ECD). However, its tyrosine kinase domain is catalytically active, making it a co-receptor that can heterodimerize with the other ErbB family members to initiate signal transduction.

ErbB signal transduction occurs upon binding of a ligand to the ECD, promoting hetero- or homodimerization amongst family members, which results in activation of their cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain, and transphosphorylation of intracellular tyrosine residues. The transphosphorylation event allows for recruitment of signaling proteins leading to activation of a large network of signaling pathways, namely, the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathways. An exception to transactivation by the ErbB family members comes from the ErbB3, which lacks a functional tyrosine kinase domain. Given that ErbB2 and ErbB3 lack part of the components required for signal transduction upon ligand binding, their main role is to act as co-receptors and heterodimerize to other ErbBs to elicit a cellular response from external stimuli.

ErbB signaling plays major roles in heart development, which will be the focus of this review, however its involvement in the nervous system, and in cancer development is also of major significance and will be reviewed elsewhere in these review series.

ErbB activation and signaling

2.1 EGFR (ErbB1)

Originally, it was thought that EGFR activation occurred upon ligand binding to a dimer complex, after which a conformational change would induce signal transduction, but x-ray crystallography studies have shown that ligand binding occurs on EGFR receptor monomers, causing a conformational change in the ECD that allows dimerization and initiation of signal transduction, an unusual occurrence among receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) [15-18], also reviewed in [19]. Ligand binding is the pivotal event that acts as the external switch to turn on signal transduction. The receptor dimerization allows for the interaction between the tyrosine kinase subdomain and the tyrosine residues on the C-terminus region of the dimerized partner, causing transphosphorylation and binding of Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing effector molecules [20].

2.2 ErbB4

Similar to the EGFR, the ErbB4 is highly sequence homologous[21] and activates in a similar manner, although differences in its ECD promote proteolytic cleavage by membrane metalloproteases (MMPs) at a higher rate than the EGFR, likely shortening the period of active signaling. Furthermore, ErbB4 undergoes a second proteolytic cleavage of the intracellular domain (ICD), which is believed to translocate into the nucleus to act as a transcriptional regulator [19, 22, 23].

2.3 ErbB2 and ErbB3

ErbB2 and ErbB3 also share high sequence homology with the EGFR and ErbB4, but unlike them, they are unable to transduce signals by homodimerization. The ErbB2 is considered an orphan receptor because it is unable to bind ligands, so it only acts as a co-receptor with other ErbB family members. In spite of the inability of the ErbB2 receptor to bind a ligand, its extracellular domain assumes a conformation that mimics the ligand-bound form of the EGFR [16, 24], and it remains the favorite family member to which other ErbBs dimerize. ErbB2 heterodimerization increases ligand binding affinity, thus prolonged activation of the signaling pathways [25]. On the other hand, the ErbB3 receptor is able to bind ligands similar to the EGFR and ErbB4, but its tyrosine kinase domain is catalytically inactive [26]. ErbB3 transduction can occur when another ErbB family member (with a catalytically active tyrosine kinase) phosphorylates the tyrosine residues on the C-terminus end.

2.4 Signaling

ErbB receptor signaling has become a complex network of interactions governed by proteins containing Src homology 2 (SH2) domains, which allows for the direct interactions with phosphotyrosines in the intracellular region of activated ErbB receptors. Given that each receptor has multiple tyrosine residues that can be potentially phosphorylated, the variety of effector molecules that can interact, and varying affinities is immense. Adding to it, adaptor molecules containing SH2 domains can attract another set of effector molecules, which in itself, adds another layer of complex regulation beyond the scope of this review, described in more detail in these excellent reviews [19, 27-29].

2.5

One of the key pathways activated by ErbB receptors is the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ ERK1/2, which is a multi-kinase cassette that consists of the Raf (a MAPK kinase kinase or MAPKKK), MEK1/2 a MAPK kinase, and the MAPK ERK1/2. The adaptor protein Grb2 anchors to the activated ErbB receptors through its SH2 domain in a complex with SOS, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) that activates the Ras-GDP by exchanging GDP for GTP. Once active, Ras can interact with Raf to ultimately promote ERK1/2 activation and translocation into the nucleus, where it acts as a transcription factor promoting cell growth, and cardiac hypertrophy [30, 31]. Protein tyrosine phosphatases also interact in this complex via SH2-mediated interactions to modulate the intensity of signaling. Germline mutations in the PTP11 gene, encoding the protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) SHP-2 are linked to Noonan syndrome (NS). Mutations in the regulatory domain of SHP-2 often lead to pulmonary valvular stenosis, atrial and ventricular septal defects, as well as a large set of phenotypically characteristic deformities commonly found in NS (OMIM 163950). In fact, over half of the patients suffering from NS carry a gain-of-function mutation in the PTP11 gene [32]. Although not entirely understood, SHP-2 plays an important role in the heart by regulating the Ras-MAPK pathway, a pathway important in valvulogenesis. This pathway is important because it regulates differentiation, migration and proliferation of cells, all of which occur during endothelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), a central process to valvulogenesis. Further importance of this pathway is highlighted by another germline mutation in the K-Ras gene which results in a protein unable to hydrolyze GTP, rendering it hyperactive, leading to a similar phenotype as the PTP11 gain-of-function mutation (D61G), leading to NS [33]. Mutations in SOS1 leading to increased Ras activity and gain of function mutations in RAF-1 are also contributors to NS [34, 35]. The contribution of unregulated Ras activity to heart defects is also observed in neurofibromatosis type I (NF1). NF1 encodes neurofibromin a GTPase activating protein (GAP), which negatively regulates Ras. NF1 patients not only have neural crest-derived abnormalities but also pulmonary valve stenosis [36]. These clinical syndromes highlight the importance for the proper dose and timing of appropriate RTK signaling during structural heart formation.

2.6

Another transduction route activated upon ErbB phosphorylation is the PI3K/AKT pathway. Recruitment of PI3K to the ErbB receptor is facilitated by its SH2 domain, attracted to the phosphotyrosine residues in the intracellular domain, near the plasma membrane, where it can phosphorylate phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) at its 3’-hydroxyl group, to produce PIP3, attracting AKT to the membrane, where it gets phosphorylated by PDK1, and then further phosphorylated for full activation [37]. Activated AKT relocates to the cytoplasm where it can phosphorylate its multiple substrates to promote cell survival and proliferation through mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation. Additionally, mTOR targets molecules such as the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), which facilitates mRNA interaction with the 40s ribosomal subunit [38], thus translation of proteins important for cell cycle progression. Furthermore, AKT inhibits the pro-apoptotic protein BAD, further contributing to cell survival [39]. Consistent with these results, it has also been shown that ErbB2 inhibition results in increased levels of the pro-apoptotic protein Bcl-xS and decreased levels of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL [40]. The requirement for AKT in heart valve morphogenesis has recently been described [41], further indicating this pathway in heart development and function. The versatility of ErbB signaling also includes interactions with the Src-FAK signaling pathway, involved in focal adhesion contact and lamellipodia formation, suggesting a relationship between ErbB activation by NRG-1 and cardiomyocyte cell-cell or cell-matrix interactions. These interactions are crucial for maintenance of electrical coupling [42].

Termination of the ErbB signal occurs by clustering of receptors in clathrin-coated pits, followed by endocytosis, ubiquitination and degradation as described in detail in these references [43-46]. The fundamental role of regulated signaling events is critical for proper cellular and organ function, as studies show, downregulation or knockout of ErbB receptors or their ligands has fatal effects, affecting heart morphogenesis, as well as proper development of the nervous system (reviewed elsewhere in these series).

ErbB mouse models and phenotypes

3.1

The importance of ErbB signaling in the heart is highlighted by observations in engineered knockout (KO) mice of ErbB2, ErbB3, ErbB4, as well as neuregulin-1 knockouts, all have lethal phenotypes with heart defects (Table 1) [47-60]. One common phenotype shared among these different ErbB KO mice is the lack of ventricular trabeculation, an important process in ventricular maturation required for physical contractions and proper blood flow. ErbB2, ErbB4, and NRG-1 KO mice die at embryonic day 10.5 (E 10.5) due to lack of trabeculation and likely myocardial competence. ErbB2 and ErbB4 have been found to be expressed in cardiac myocytes at E9.5/10.5, whereas NRG is expressed in adjacent endocardium. Importantly, neither ErbB4 nor ErbB2 can compensate for the loss of the other receptor, suggesting that ErbB2/4 heterodimer is required for NRG signaling in the heart [47, 54, 57, 61]. In addition to these observations, ErbB2 is also vital to development of neuromuscular junctions [36]. Furthermore, the human Shp2 lesions in Noonan syndrome have been modeled in knock-in mice (SHP2D61G+) which exhibit most of the heart defects including valvular stenosis, as well as the myeloproliferative disorder observed in humans [59]. Although ventricular trabeculation is relatively normal in ErbB3 null mice, these homozygous embryos die around E13.5 due to disruption of endocardial cushion mesenchyme formation [55, 56]. The endocardial cushions are the precursor tissues from which valves originate, thus disruption of these, is most likely the cause of embryonic death at E13.5. The role of the ErbB2/ErbB3 dimer in early valve formation was further substantiated in cardiac cushion explants and by closer examination of the respective KO showing deficiencies in valve mesenchyme formation in ex-vivo [56]. The role of EGFR or ErbB1 in heart development and function was first discovered in the Waved-2 mice, named for their wavy hair. The waved-2 mouse model is used to study EGFR signaling because of a mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR rendering it partially active (10-15% activity)[63]. Waved-2 mice exhibit hyperplastic outflow tract valves, suggesting that EGFR catalytic activity is important for semilunar valve morphogenesis and maturation. Interestingly, this phenotype shows higher penetrance when mice have a heterozygous Shp2+/- background, suggesting that Shp2 is required for EGFR signaling in semilunar valvulogenesis [51].

Table 1.

Expression of ErbBs, their ligands and phenotypes in heart development and disease

| Molecule | Dysregulation | Phenotype (transgenic mouse models) | Lethality | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRG1 | KO | Lack of ventricular trabeculation, disrupted endocardial cushion formation | E 10.5 – 11.5 | [47] |

| ErbB1 | KO | Semilunar valve defects | Viable, post natal lethality | [48-51] |

| Waved-2 (10% kinase activity) | Hyperplastic OFT valves | Viable | [50, 51] | |

| ErbB2 | KO | Lack of ventricular trabeculation, underdeveloped cushions | E 10.5 | [52, 54, 56, 61] |

| Down-regulation | Myocardial thinning, dilated cardiomyopathy | Spontaneous cardiomyopathy | [54, 98, 99] | |

| ErbB3 | KO | Disrupted endocardial cushion formation | E 13.5 | [55, 56] |

| ErbB4 | KO | Lack of ventricular trabeculation | E 10.5 | [57] |

| Down-regulation | Impaired contractility and delayed conduction, dilated cardiomyopathy | Cardiomyopathy development at 3 months of age | [100] | |

| HB-EGF | KO | Dilated cardiomyopathy and enlarged myxomatous valves | Early post-natal lethality | [50, 58] |

| TACE (ADAM17) | KO | Myxomatous valves, same phenotype as HB-EGF KO | Early post-natal lethality | [50] |

| Shp2 | Constitutively active (point mutation knock-in) | Valvular stenosis and hyperproliferative valves | Viable | [59] |

| Ras | Constitutively active | Hyperproliferative endocardial cushions | Perinatal | [60] |

| NF1 | Mutated-inactive | Hyperproliferative endocardial cushions | Perinatal | [101] |

| ShcA | Mutated AKT domain | Abnormal trabeculation | E 12.5 | [62] |

KO: Knockout, homozygous null; OFT: outflow tract

3.2

Kinase inactive and conditional KO models of ErbB receptors display similar embryonic heart defects consistent with the conventional KO counterparts [52, 64]. The detailed analysis of the EGFR KO mouse by Jackson et al., showed these mice also have valve defects in the OFT, as well as atrioventricular valves [50] consistent with observations in the Waved-2 mice. A knock-in mouse model with a kinase inactive variant of the ErbB2 receptor shows a similar phenotype to the ErbB2 null mouse, substantiating ErbB2 kinase activity importance in trabeculae formation [52]. Conditional ventricular ErbB2 KO mice were developed using a Cre-loxP system where the ErbB2 gene was floxed and Cre expression was driven by the myosin light chain 2v (MLC2v) promoter, restricting Cre expression to cardiac ventricular muscle cells, and thus the loss of expression of ErbB2 specific to the ventricular myocardium [65]. Although these conditional knockout (CKO) mice appear normal at birth and lived through adulthood, these animals develop dilated cardiomyopathy and myocardial thinning [54, 65, 66]. Also, a decrease in fractional shortening and increased mortality was observed 8 days after transthoracic aortic banding (TAC) [65]. TAC is a useful pressure overload model used to evaluate left ventricular hypertrophy in response to hemodynamic stress. Furthermore, Crone et al. isolated cardiomyocytes from the ErbB2 conditional KO mice (CKO) and confirmed a 40% loss of ErbB2 protein as compared to cardiomyocytes isolated from wild type mice.

Other gene-targeting studies related to ErbB signaling include the deletion of HB-EGF, which results in myxomatous enlarged valves, demonstrating its role in heart valve maturation[50]. Mouse models deficient in ADAM17/TACE, a membrane metalloprotease that cleaves the pro-form of HB-EGF into active growth factor, share the same phenotype as HB-EGF knockout models [50]. Gene mutations resulting in truncation of the cytoplasmic tail of NRG created a model in which all NRG forms could not be cleaved by proteases thus preventing ErbB3/ErbB4 activation [67]. These animals had similar cardiac phenotype as the conventional null NRG embryos substantiating the contribution of both proteolytic cleavage of these growth factors and NRG in heart development and maturation. Collectively, these mouse studies underscore the importance of ErbB activity in formation and function of the heart especially for pathways involving ErbB2.

Maintenance and function of adult cardiomyocytes by ErbB signals

4.1

EGF/NRG growth factors and ErbB receptors are needed for critical aspects of both neuronal and heart development [47, 53, 57, 68]; however, their importance to maintenance of the adult heart was recently discovered due to cardiotoxic effects of drugs that target ErbB receptors in anticancer therapies. Chemotherapeutic agents such as anthracyclines, taxanes, as well as novel agents such as anti-ErbB2 antibodies, imatinib and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [69, 70], are all linked to cardiotoxic effects.

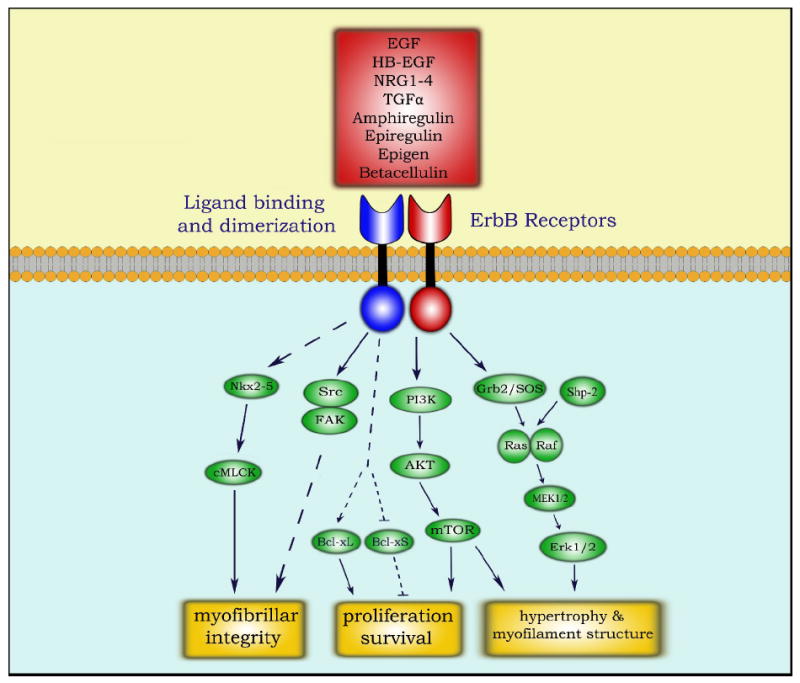

The activation of ErbB2/ErbB4 signaling by NRG-1 has been found to be important for cardiomyocyte survival. NRG signaling through ErbB receptors plays an important role in cellular functions such as differentiation, migration and cell survival. Particularly, NRG signaling is crucial for cardiomyocyte survival due to the role it plays in multiple signaling cascades. NRG-1 has been shown to induce PI3K mediated AKT activation, important for cardiomyocyte protection against cell death [71-75]. Activation of PI3K by NRG-1 requires ErbB4 as a hetero- or homodimer. While PI3K activation often involves ErbB2, it is not required or sufficient to induce AKT phosphorylation and activation [71]. Although not entirely understood, the role of AKT is crucial for cardiomyocyte survival as it regulates apoptosis by controlling bcl-x splicing [40, 68], as well as modulating bcl-2 family protein expression [76]. Furthermore, cardiac AKT activation can result in activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), promoting protein synthesis and hypertrophy [77]. In-vitro studies show that NRG-1 treatment of primary cardiomyocytes can protect against cell death induced by serum starvation, β-adrenergic receptor activation and anthracyclines [71, 72, 74, 75, 78-81]. Cytoprotection by NRG-1 against cell death is not achieved when a dominant negative AKT isoform is overexpressed, suggesting that NRG-1 cytoprotection is mediated mainly through the PI3K/AKT pathway. Additional studies of AKT signaling by Meadows et al. show that AKT plays a key role in the initiation of endothelial to mesenchymal transition in the endocardial cushions, a complex process crucial for proper valve development [41]. Further signaling by NRG includes the MAPK/ERK1/2 pathway; a well known pathway involved in cellular proliferation and hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes [82]. A transgenic mouse line containing a cardiac-restricted active MEK1 cDNA (upstream effector kinase that activates ERK1/2, figure 1) was generated, demonstrating increased hypertrophy and cardiac function, as determined by echocardiography without any signs of cardiomyopathies [83]. This is strong evidence from in-vivo studies supporting the idea that MAPK/ERK1/2 signaling is an important pathway for cardiomyocyte function and hypertrophy.

Figure 1. ErbB signaling in adult cardiomyocytes.

Description: ErbB receptor signaling essential for cardiomyocyte function. Signal transduction is initiated upon ligand binding (red box), inducing dimerization and transphosphorylation of ErbB receptors. A simplified illustration of ErbB signaling is focused on signaling cascades relevant to cardiomyocyte function and survival, mediated by the Ras-MAPK, PI3K-AKT, Src-FAK, and Nkx2.5 pathways.[56]

Trastuzumab, tyrosine kinase inhibitors and cardiac toxicity

4.2

The importance of ErbB signaling in heart form and function is highlighted by the associated cardiotoxicity in patients treated with Trastuzumab (Herceptin). Standard chemotherapy agents such as the anthracyclines are known to cause irreversible cardiac abnormalities. The use of Trastuzumab arose from the increasing understanding of ErbB2 in breast cancer making it a new molecular therapy for breast cancer patients [84]. The monoclonal antibody trastuzumab targets the open conformation state of the ErbB2 receptor [16, 24], as this receptor is overexpressed in a substantial number of breast cancers. Trastuzumab has been a successful therapy in reducing mortality rates for breast cancer patients [85, 86]. Unfortunately, a portion of patients treated with trastuzumab later developed congestive heart failure, especially those concurrently or previously treated with anthracyclines [87]. Observations with animal models provide evidence for both ErbB2 and ErbB4 in cardiomyocyte protection. For example, Rohrbach et al.[88], show that ErbB2/ErbB4 receptors are downregulated during progression of cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure. Crone et al. [65], created a conditional ErbB2 mutant line to bypass the embryonic lethality of the conventional knockout phenotype. The conditional KO ErbB2 mice develop dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Liu et al. [89] show that recombinant NRG1 attenuated the severity of ischemic heart disease and cardiomyopathy in rodent models substantiating the protective impact of NRG-ErbB signals. Ozcelik et al. show that ErbB2 and ErbB4 are detected in myocytes to the T-tubule system suggesting a connection to maintenance of myofibrillar integrity [90]. Thus, when ErbB expression or activity is lost, ensuing collapse of myofibrils triggers myocyte cell death leading to cardiomyopathy. These animal models and other studies strongly suggest that inhibition of the ErbB2 pro-survival signal has a detrimental effect on cardiomyocyte viability, leading to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure.

In this regard, there is an emerging concern with a variety of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) and cardiotoxicity. The heart appears to be a sensitive organ to long term TKI exposure. There is a growing list of TKI associated with negative effects on the heart, many directly or indirectly targeting the ErbB signaling pathways (Table 2). Combination therapies of Trastuzumab with other antineoplastic therapies such as imatinib (Gleevec), and taxanes such as paclitaxel (Taxol), have also revealed cardiotoxic side effects [91-93]. Imatinib alone has recently been linked to cardiotoxicity in patients receiving the drug for gastrointestinal tumors or chronic myelogenous leukemia [94, 95]. The emerging reports of thiazolidinediones (Avandia) causing cardiotoxicity in diabetic patients [96] underscores the impact that changing signaling pathways can have on the heart. One can speculate that both Gleevec and Avandia are impacting myocyte integrity possibly through attenuating pro-survival signals from ErbB receptors. These observations highlight the need for patients and clinicians to carefully consider the cardiovascular risk stratification when considering new pharmacological agents such as those disrupting ErbB signaling.

Table 2.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors linked with cardiac toxicity

| TKI | Brand name | Target(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Trastuzumab | Herceptin | ErbB2 |

| Gefitinib | Iressa | EGFR |

| Erlotinib | Tarceva | EGFR |

| Cetuximab | Erbitux | EGFR |

| Lapatinib | Tykerb | EGFR, ErbB2 |

| Dasatinib | Sprycel | Src kinases |

| Imatinib | Gleevec | Bcr-Abl |

| Nilotinib | Tasigna | Bcr-Abl |

| sunitinib | Sutent | Multiple RTKs |

| Sorafenib | Nexavar | Raf, VEGFR, PDGFR |

| Bevacizumab | Avastin | VEGFR |

VEGFR: Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; PDGFR: Platelet-derived growth factor receptor

Conclusions

5.1

It is clear that ErbB signaling in the heart is of major significance from the developmental stages, all throughout life. In development, ErbBs act as key regulators of cell fate, whether it is differentiation and migration in the endocardial cushions, or proliferation necessary for ventricular trabeculation. Further elucidation of ErbB temporal and spatial roles during heart development, as well as better understanding of the signal transduction pathways they activate would help improve our understanding of the origins of congenital heart defects, providing us with potential new therapeutics to reduce CHD mortality rates.

In the adult heart, anti-ErbB2 therapy has highlighted the role ErbB signaling plays in anti-apoptotic pathways, and maintenance of cardiomyocyte function, as well as hypertrophy. Clinically, anti-ErbB2 cancer therapy has proved successful, but the incidence of cardiotoxicity has limited the potential of this targeted therapy. The discovery of cardiotoxicity potential with Trastuzumab revealed a shared risk with this new generation of targeted molecular therapeutics (Table 2). Thus, the understanding of ErbB signaling and dysregulation in cancer and heart function will continue to be a research priority. Ironically, detailed mechanistic studies into ErbBs role in CV biology are anticipated to reveal new therapies for congestive heart failure and dilated cardiomyopathy [97].

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank K. Ermit for reviewing the manuscript.

P.S.S. is supported by the Superfund Training Grant (NIH ES 04940; ES06694).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Pablo Sanchez-Soria, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, College of Pharmacy, University of Arizona, 1703 E. Mabel St., PO Box 210207, Tucson, AZ 85721-0207, USA. Soria@pharmacy.rizona.edu.

Todd D Camenisch, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, College of Pharmacy, University of Arizona, Steele Memorial Children’s Research Center, University of Arizona, 1703 E. Mabel St., PO Box 210207, Tucson, AZ 85721-0207, USA. Camenisch@pharmacy.arizona.edu, Tel. 520-6260240, Fax +1-520-6262466.

References

- 1.Schroeder JA, Jackson LF, Lee DC, Camenisch TD. Form and function of developing heart valves: Coordination by extracellular matrix and growth factor signaling. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2003;81(7):392–403. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0456-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastava D. Genetic regulation of cardiogenesis and congenital heart disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:199–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cripps RM, Olson EN. Control of cardiac development by an evolutionarily conserved transcriptional network. Dev Biol. 2002;246(1):14–28. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chien KR, Olson EN. Converging pathways and principles in heart development and disease. Cell. 2002;110(2):153–62. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00834-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srivastava D, Olson EN. A genetic blueprint for cardiac development. Nature. 2000;407(6801):221–6. doi: 10.1038/35025190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.EPSTEIN JA, BUCK CA. Transcriptional regulation of cardiac development: Implications for congenital heart disease and DiGeorge syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2000;48(6) doi: 10.1203/00006450-200012000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srivastava D. GENETIC ASSEMBLY OF THE HEART: Implications for congenital heart disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63(1):451–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allan LD, Crawford DC, Chita SK, Anderson RH, Tynan MJ. Familial recurrence of congenital heart disease in a prospective series of mothers referred for fetal echocardiography* 1. Am J Cardiol. 1986;58(3):334–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2009 update: A report from the american heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):e21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moller J. Prevalence and incidence of cardiac malformations. Perspectives in pediatric cardiology. 6:1984–1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroeder JA, Lee DC. Transgenic mice reveal roles for TGFα and EGF receptor in mammary gland development and neoplasia. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1997;2(2):119–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1026347629876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riese DJ, Komurasaki T, Plowman GD, Stern DF. Activation of ErbB4 by the bifunctional epidermal growth factor family hormone epiregulin is regulated by ErbB2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(18):11288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elenius K, Paul S, Allison G, Sun J, Klagsbrun M. Activation of HER4 by heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor stimulates chemotaxis but not proliferation. EMBO J. 1997;16(6):1268–78. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinkas-Kramarski R, Soussan L, Waterman H, Levkowitz G, Alroy I, Klapper L, et al. Diversification of neu differentiation factor and epidermal growth factor signaling by combinatorial receptor interactions. EMBO J. 1996;15(10):2452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burgess AW, Cho HS, Eigenbrot C, Ferguson KM, Garrett TPJ, Leahy DJ, et al. An open-and-shut case? recent insights into the activation of EGF/ErbB receptors. Mol Cell. 2003;12(3):541–52. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrett TPJ, McKern NM, Lou M, Elleman TC, Adams TE, Lovrecz GO, et al. The crystal structure of a truncated ErbB2 ectodomain reveals an active conformation, poised to interact with other ErbB receptors. Mol Cell. 2003;11(2):495–505. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorissen RN, Walker F, Pouliot N, Garrett TPJ, Ward CW, Burgess AW. Epidermal growth factor receptor: Mechanisms of activation and signalling. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284(1):31–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogiso H, Ishitani R, Nureki O, Fukai S, Yamanaka M, Kim JH, et al. Crystal structure of the complex of human epidermal growth factor and receptor extracellular domains. Cell. 2002;110(6):775–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00963-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuller SJ, Sivarajah K, Sugden PH. ErbB receptors, their ligands, and the consequences of their activation and inhibition in the myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44(5):831–54. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.02.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Gureasko J, Shen K, Cole PA, Kuriyan J. An allosteric mechanism for activation of the kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cell. 2006;125(6):1137–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plowman GD, Culouscou JM, Whitney GS, Green JM, Carlton GW, Foy L, et al. Ligand-specific activation of HER4/p180erbB4, a fourth member of the epidermal growth factor receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(5):1746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpenter G. Nuclear localization and possible functions of receptor tyrosine kinases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15(2):143–8. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlessinger J, Lemmon MA. Nuclear signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases: The first robin of spring. Cell. 2006 Oct 6;127(1):45–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho HS, Mason K, Ramyar KX, Stanley AM, Gabelli SB, Denney DW, Jr, et al. Structure of the extracellular region of HER2 alone and in complex with the herceptin fab. Nature. 2003 Feb 13;421(6924):756–60. doi: 10.1038/nature01392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karunagaran D, Tzahar E, Beerli R, Chen X, Graus-Porta D, Ratzkin B, et al. ErbB-2 is a common auxiliary subunit of NDF and EGF receptors: Implications for breast cancer. EMBO J. 1996;15(2):254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Citri A, Skaria KB, Yarden Y. The deaf and the dumb: The biology of ErbB-2 and ErbB-3. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284(1):54–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dengjel J, Akimov V, Blagoev B, Andersen JS. Signal transduction by growth factor receptors: Signaling in an instant. Cell cycle. 2007;6(23):2913–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.23.5086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Wolf-Yadlin A, Ross PL, Pappin DJ, Rush J, Lauffenburger DA, et al. Time-resolved mass spectrometry of tyrosine phosphorylation sites in the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling network reveals dynamic modules. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2005;4(9):1240. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500089-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulze WX, Deng L, Mann M. Phosphotyrosine interactome of the ErbB-receptor kinase family. Molecular systems biology. 2005;1(1) doi: 10.1038/msb4100012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006 Aug;7(8):589–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in heart development and diseases. Circulation. 2007;116(12):1413. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.679589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tartaglia M, Mehler EL, Goldberg R, Zampino G, Brunner HG, Kremer H, et al. Mutations in PTPN11, encoding the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, cause noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;29(4):465–8. doi: 10.1038/ng772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schubbert S, Zenker M, Rowe SL, Böll S, Klein C, Bollag G, et al. Germline KRAS mutations cause noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2006;38(3):331–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts AE, Araki T, Swanson KD, Montgomery KT, Schiripo TA, Joshi VA, et al. Germline gain-of-function mutations in SOS1 cause noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2006;39(1):70–4. doi: 10.1038/ng1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pandit B, Sarkozy A, Pennacchio LA, Carta C, Oishi K, Martinelli S, et al. Gain-of-function RAF1 mutations cause noonan and LEOPARD syndromes with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2007;39(8):1007–12. doi: 10.1038/ng2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin AE, Birch PH, Korf BR, Tenconi R, Niimura M, Poyhonen M, et al. Cardiovascular malformations and other cardiovascular abnormalities in neurofibromatosis 1. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2000;95(2):108–17. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001113)95:2<108::aid-ajmg4>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgensztern D, McLeod HL. PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway as a target for cancer therapy. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16(8):797. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000173476.67239.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18(16):1926. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, et al. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91(2):231–41. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grazette LP, Boecker W, Matsui T, Semigran M, Force TL, Hajjar RJ, et al. Inhibition of ErbB2 causes mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiomyocytes∷ Implications for herceptin-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(11):2231–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meadows KN, Iyer S, Stevens MV, Wang D, Shechter S, Perruzzi C, et al. Akt promotes endocardial-mesenchyme transition. Journal of angiogenesis research. 2009;1:2. doi: 10.1186/2040-2384-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuramochi Y, Guo X, Sawyer DB. Neuregulin activates erbB2-dependent src/FAK signaling and cytoskeletal remodeling in isolated adult rat cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41(2):228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schlessinger J, Lemmon MA. Nuclear signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases: The first robin of spring. Cell. 2006;127(1):45–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sweeney C, Carraway KL. Negative regulation of ErbB family receptor tyrosine kinases. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(2):289–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waterman H, Yarden Y. Molecular mechanisms underlying endocytosis and sorting of ErbB receptor tyrosine kinases. FEBS Lett. 2001;490(3):142–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marmor MD, Yarden Y. Role of protein ubiquitylation in regulating endocytosis of receptor tyrosine kinases. Oncogene. 2004;23(11):2057–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyer D, Birchmeier C. Multiple essential functions of neuregulin in development. 1995 doi: 10.1038/378386a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sibilia M, Wagner EF. Strain-dependent epithelial defects in mice lacking the EGF receptor. Science. 1995;269(5221):234. doi: 10.1126/science.7618085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sibilia M, Wagner B, Hoebertz A, Elliott C, Marino S, Jochum W, et al. Mice humanised for the EGF receptor display hypomorphic phenotypes in skin, bone and heart. Development. 2003;130(19):4515. doi: 10.1242/dev.00664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jackson LF, Qiu TH, Sunnarborg SW, Chang A, Zhang C, Patterson C, et al. Defective valvulogenesis in HB-EGF and TACE-null mice is associated with aberrant BMP signaling. EMBO J. 2003;22(11):2704. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen B, Bronson RT, Klaman LD, Hampton TG, Wang JF, Green PJ, et al. Mice mutant for egfr and Shp2 have defective cardiac semilunar valvulogenesis. Nat Genet. 2000 Mar;24(3):296–9. doi: 10.1038/73528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chan R, Hardy WR, Laing MA, Hardy SE, Muller WJ. The catalytic activity of the ErbB-2 receptor tyrosine kinase is essential for embryonic development. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(4):1073. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1073-1078.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee KF, Simon H, Chen H, Bates B, Hung MC, Hauser C. Requirement for neuregulin receptor erbB2 in neural and cardiac development. Nature. 1995 Nov 23;378(6555):394–8. doi: 10.1038/378394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Negro A, Brar BK, Lee KF. Essential roles of Her2/erbB2 in cardiac development and function. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2004;59(1):1. doi: 10.1210/rp.59.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Erickson SL, O’Shea KS, Ghaboosi N, Loverro L, Frantz G, Bauer M, et al. ErbB3 is required for normal cerebellar and cardiac development: A comparison with ErbB2-and heregulin-deficient mice. Development. 1997 Dec;124(24):4999–5011. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.24.4999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Camenisch TD, Schroeder JA, Bradley J, Klewer SE, McDonald JA. Heart-valve mesenchyme formation is dependent on hyaluronan-augmented activation of ErbB2-ErbB3 receptors. Nat Med. 2002 Aug;8(8):850–5. doi: 10.1038/nm742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gassmann M, Casagranda F, Orioli D, Simon H, Lai C, Klein R, et al. Aberrant neural and cardiac development in mice lacking the ErbB4 neuregulin receptor. Nature. 1995 Nov 23;378(6555):390–4. doi: 10.1038/378390a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iwamoto R, Yamazaki S, Asakura M, Takashima S, Hasuwa H, Miyado K, et al. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor and ErbB signaling is essential for heart function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(6):3221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0537588100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Araki T, Mohi MG, Ismat FA, Bronson RT, Williams IR, Kutok JL, et al. Mouse model of noonan syndrome reveals cell type–and gene dosage–dependent effects of Ptpn11 mutation. Nat Med. 2004;10(8):849–57. doi: 10.1038/nm1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Camenisch TD, Spicer AP, Brehm-Gibson T, Biesterfeldt J, Augustine ML, Calabro A, Jr, et al. Disruption of hyaluronan synthase-2 abrogates normal cardiac morphogenesis and hyaluronan-mediated transformation of epithelium to mesenchyme. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(3):349–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI10272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee KF, Simon H, Chen H, Bates B, Hung MC, Hauser C. Requirement for neuregulin receptor erbB2 in neural and cardiac development. 1995 doi: 10.1038/378394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hardy W, Li L, Wang Z, Sedy J, Fawcett J, Frank E, et al. Combinatorial ShcA docking interactions support diversity in tissue morphogenesis. Science. 2007;317(5835):251. doi: 10.1126/science.1140114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luetteke N, Phillips H, Qiu T, Copeland N, Earp H, Jenkins N, et al. The mouse waved-2 phenotype results from a point mutation in the EGF receptor tyrosine kinase. Genes Dev. 1994;8(4):399. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morris JK, Lin W, Hauser C, Marchuk Y, Getman D, Lee KF. Rescue of the cardiac defect in ErbB2 mutant mice reveals essential roles of ErbB2 in peripheral nervous system development. Neuron. 1999;23(2):273–83. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80779-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Crone SA, Zhao YY, Fan L, Gu Y, Minamisawa S, Liu Y, et al. ErbB2 is essential in the prevention of dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2002;8(5):459–65. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Özcelik C, Erdmann B, Pilz B, Wettschureck N, Britsch S, Hübner N, et al. Conditional mutation of the ErbB2 (HER2) receptor in cardiomyocytes leads to dilated cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(13):8880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122249299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu X, Hwang H, Cao L, Buckland M, Cunningham A, Chen J, et al. Domain-specific gene disruption reveals critical regulation of neuregulin signaling by its cytoplasmic tail. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(22):13024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rohrbach S, Niemann B, Silber RE, Holtz J. Neuregulin receptors erbB2 and erbB4 in failing human myocardium -- depressed expression and attenuated activation. Basic Res Cardiol. 2005 May;100(3):240–9. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0514-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen B, Peng X, Pentassuglia L, Lim CC, Sawyer DB. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Cardiovascular Toxicology. 2007;7(2):114–21. doi: 10.1007/s12012-007-0005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feldman AM, Lorell BH, Reis SE. Trastuzumab in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer : Anticancer therapy versus cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2000 Jul 18;102(3):272–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fukazawa R, Miller TA, Kuramochi Y, Frantz S, Kim YD, Marchionni MA, et al. Neuregulin-1 protects ventricular myocytes from anthracycline-induced apoptosis via erbB4-dependent activation of PI3-kinase/Akt. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35(12):1473–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fujio Y, Nguyen T, Wencker D, Kitsis RN, Walsh K. Akt promotes survival of cardiomyocytes in vitro and protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mouse heart. Circulation. 2000;101(6):660. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.6.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matsui T, Rosenzweig A. Convergent signal transduction pathways controlling cardiomyocyte survival and function: The role of PI 3-kinase and akt. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005 Jan;38(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miao W, Luo Z, Kitsis RN, Walsh K. Intracoronary, adenovirus-mediated akt gene transfer in heart limits infarct size following ischemia-reperfusion injury in vivo* 1. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32(12):2397–402. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sawyer DB, Zuppinger C, Miller TA, Eppenberger HM, Suter TM. Modulation of anthracycline-induced myofibrillar disarray in rat ventricular myocytes by neuregulin-1 {beta} and anti-erbB2: Potential mechanism for trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2002;105(13):1551. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013839.41224.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dhanasekaran A, Gruenloh SK, Buonaccorsi JN, Zhang R, Gross GJ, Falck JR, et al. Multiple antiapoptotic targets of the PI3K/Akt survival pathway are activated by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids to protect cardiomyocytes from hypoxia/anoxia. American Journal of Physiology- Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2008;294(2):H724. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00979.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kemi OJ, Ceci M, Wisloff U, Grimaldi S, Gallo P, Smith GL, et al. Activation or inactivation of cardiac Akt/mTOR signaling diverges physiological from pathological hypertrophy. J Cell Physiol. 2008;214(2):316–21. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pentassuglia L, Sawyer DB. The role of neuregulin-1 [beta]/ErbB signaling in the heart. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315(4):627–37. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhao YY, Sawyer DR, Baliga RR, Opel DJ, Han X, Marchionni MA, et al. Neuregulins promote survival and growth of cardiac myocytes. persistence of ErbB2 and ErbB4 expression in neonatal and adult ventricular myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998 Apr 24;273(17):10261–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuramochi Y, Lim CC, Guo X, Colucci WS, Liao R, Sawyer DB. Myocyte contractile activity modulates norepinephrine cytotoxicity and survival effects of neuregulin-1 {beta} American Journal of Physiology- Cell Physiology. 2004;286(2):C222. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00312.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Okoshi K, Nakayama M, Yan X, Okoshi MP, Schuldt AJT, Marchionni MA, et al. Neuregulins regulate cardiac parasympathetic activity: Muscarinic modulation of {beta}-adrenergic activity in myocytes from mice with neuregulin-1 gene deletion. Circulation. 2004;110(6):713. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138109.32748.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ueyama T, Kawashima S, Sakoda T, Rikitake Y, Ishida T, Kawai M, et al. Requirement of activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade in myocardial cell hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32(6):947–60. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bueno OF, De Windt LJ, Tymitz KM, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Klevitsky R, et al. The MEK1–ERK1/2 signaling pathway promotes compensated cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 2000;19(23):6341–50. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gschwind A, Fischer OM, Ullrich A. The discovery of receptor tyrosine kinases: Targets for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2004;4(5):361–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, Suman VJ, Geyer CE, Jr, Davidson NE, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1673. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Joensuu H, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Bono P, Alanko T, Kataja V, Asola R, et al. Adjuvant docetaxel or vinorelbine with or without trastuzumab for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(8):809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(11):783. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rohrbach S, Yan X, Weinberg EO, Hasan F, Bartunek J, Marchionni MA, et al. Neuregulin in cardiac hypertrophy in rats with aortic stenosis: Differential expression of erbB2 and erbB4 receptors. Circulation. 1999;100(4):407. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu X, Gu X, Li Z, Li X, Li H, Chang J, et al. Neuregulin-1/erbB-activation improves cardiac function and survival in models of ischemic, dilated, and viral cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Oct 3;48(7):1438–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ozcelik C, Erdmann B, Pilz B, Wettschureck N, Britsch S, Hubner N, et al. Conditional mutation of the ErbB2 (HER2) receptor in cardiomyocytes leads to dilated cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Jun 25;99(13):8880–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122249299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kerkelä R, Grazette L, Yacobi R, Iliescu C, Patten R, Beahm C, et al. Cardiotoxicity of the cancer therapeutic agent imatinib mesylate. Nat Med. 2006;12(8):908–16. doi: 10.1038/nm1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gehl J, Boesgaard M, Paaske T, Jensen BV, Dombernowsky P. Combined doxorubicin and paclitaxel in advanced breast cancer: Effective and cardiotoxic. Annals of Oncology. 1996;7(7):687. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tan-Chiu E, Yothers G, Romond E, Geyer CE, Jr, Ewer M, Keefe D, et al. Assessment of cardiac dysfunction in a randomized trial comparing doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel, with or without trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy in node-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-overexpressing breast cancer: NSABP B-31. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(31):7811. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Turrisi G, Montagnani F, Grotti S, Marinozzi C, Bolognese L, Fiorentini G. Congestive heart failure during imatinib mesylate treatment. Int J Cardiol. 2009 Aug 3; doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Trent JC, Patel SS, Zhang J, Araujo DM, Plana JC, Lenihan DJ, et al. Rare incidence of congestive heart failure in gastrointestinal stromal tumor and other sarcoma patients receiving imatinib mesylate. Cancer. 2010;116(1):184–92. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shaya FT, Lu Z, Sohn K, Weir MR. Thiazolidinediones and cardiovascular events in high-risk patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus: A comparison with other oral antidiabetic agents. 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gao R, Zhang J, Cheng L, Wu X, Dong W, Yang X, et al. A phase II, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, based on standard therapy, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of recombinant human neuregulin-1 in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(18):1907–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Crone SA, Zhao YY, Fan L, Gu Y, Minamisawa S, Liu Y, et al. ErbB2 is essential in the prevention of dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2002 May;8(5):459–65. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nebigil CG, Maroteaux L. A novel role for serotonin in heart. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2001;11(8):329–35. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Garcia-Rivello H, Taranda J, Said M, Cabeza-Meckert P, Vila-Petroff M, Scaglione J, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy in erb-b4-deficient ventricular muscle. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2005;289(3):H1153. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00048.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lakkis MM, Epstein JA. Neurofibromin modulation of ras activity is required for normal endocardial-mesenchymal transformation in the developing heart. Development. 1998;125(22):4359. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.22.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]