Abstract

A new observational measure of attachment strategies in the home, the Toddler Attachment Sort-45 (TAS-45) was completed for 59 18- to 36-month-old recipients of EHS. Mothers completed the Brief Infant Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA); children were tested on the Preschool Language Scale (PLS-4); and a mother-child snack was videotaped and coded for dyadic mutuality. The TAS-45 Security score was associated with more dyadic mutuality, higher language and competence scores, and lower problem scores. Discriminant validity was evidenced by a lack of associations with the TAS-45 Dependence score. The TAS-45 Disorganized “hotspot” (cluster) score also showed expected associations with these outcomes. Results are discussed in terms of next steps for use of the TAS-45 in research and practice.

Keywords: attachment, mother-child interaction, toddlers, home visiting, Early Head Start

Early Head Start (EHS), an expansion of the federal Head Start program, serves low-income pregnant women and families with children up to 3 years old. EHS began in 1995 with 68 initial programs that were funded by competitive grant applications. By 2003 there were 664 EHS programs nationwide serving over 55,000 families. EHS is a two-generation, comprehensive program developed such that each EHS site implements a uniquely designed program within EHS performance guidelines, which are based on an ecological systems perspective (Advisory Committee on Services for Families with Infants and Toddlers, 1994).

Supporting parent-child attachment relationships and infant social-emotional well-being are fundamental aims of EHS (Fenichel, 2000; Mann, 1997). Assessing the child-parent attachment is therefore of critical interest for programs and for intervention research involving EHS-eligible populations. The two best-known tools for the measurement of early attachment are the Strange Situation procedure (SSP; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters & Wall, 1978) and the Attachment Q-Sort (AQS; Waters & Deane, 1985; Waters, 1987). The SSP requires a laboratory playroom, video equipment, and intensive training to conduct and code the assessment. The timing and sequencing of the intentional stressors in the SSP can also be intimidating for families. Last, because the experimenter is in control, the measure is somewhat lacking in ecological validity, or “real world” authenticity. For all of these reasons, the SSP is not suitable for use by EHS programs to measure the quality of child-parent attachment. It is often limited for intervention research as well.

In contrast, the AQS has many features which favor its use by EHS programs and for research with EHS and similarly vulnerable families. Specifically, the AQS describes children's secure-base behavior and its correlates with a set of 90 items that are sorted by observers into pre-defined piles, from most to least applicable. The AQS is scored after one or more 2-3 hour home visits, making it more ecologically valid than a laboratory-based procedure. The AQS can be collected repeatedly without threats to its validity, whereas children get extremely distressed with repeated Strange Situation assessments. The AQS generates a Security factor score, which is based on correlations with experts’ criterion sorts of the AQS items for prototypically secure children, and a Dependence factor score, tapping distress proneness, considered to be an aspect of temperament (Belsky & Rovine, 1987; Roisman & Fraley, 2008). A recent meta-analysis indicates that the AQS has been extensively validated as a measure of the quality of attachment relationships between children from age one through the preschool years and their primary caregivers (van IJzendoorn, Vereijken, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Riksen-Walraven, 2004). Despite these benefits, the 90-item Q-sort procedure is labor intensive (scoring after visits can take 45 minutes). Further, the AQS does not provide information on disorganization in attachment strategies, like the SSP, a limitation for some research or intervention contexts.

Designed in part to overcome the limitations of the SSP and AQS, a new measure employing observation of secure base behavior and naturally occurring indicators of attachment strategies in the home, the Toddler Attachment Sort-45 (TAS-45), holds promise for use with EHS and other at-risk families.

Development of the Toddler Attachment Sort-45 (TAS-45)

The TAS-45 was developed by a research team led by Kirkland and Bimler (Bimler & Kirkland, 2002; Kirkland, Bimler, Drawneek, McKim, Schölmerich, & Axel, 2004), supported in part by the U.S Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics for inclusion in the 24-month child assessment of the national Early Child Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort (ECLS-B; Andreassen, Fletcher, & Park, 2006; Andreassen & West, 2007). Although the TAS-45 was developed to assess child-parent attachment quality for two-year-olds in the ECLS-B, child assessment age ranged from 16 to 39 months, with 98% of the children between 22 and 28 months of age. AQS-related material was used in the development of the TAS-45 courtesy of E. Waters. Development began with the re-analysis of various 100-item (Waters & Deane, 1985) and 90-item (Waters, 1987) AQS data sets (for a non-redundant total of 145 items across the two sets) from several countries using well-established as well as novel multidimensional scaling (MDS) techniques. Their methods have been described in detail (Andreassen et al., 2006; Bimler & Kirkland, 2002; Kirkland et al., 2004).

For the version of the TAS-45 used in the ECLS-B, Kirkland et al. (2004) first applied MDS and facet cluster analysis to map the 145 AQS items on to eight “hotspots” or clusters defined according to their “face value” or directly perceived meaning. For convenience, the eight hotspot clusters were labelled with letters of the alphabet, S through Z. Next they identified a subset of 39 AQS items that functioned as well as a larger set to describe children's overall security and represent the eight hotspots, a process which resulted in four to six items per hotspot. (See Table 1 for TAS-45 hotspots and respective items.) Finally, they reduced the number of sorting piles from nine to five using the Method of Successive Sorts (MOSS; Block, 1961). Sorting began by first placing items into three piles, “applies,” “undecided,” and “does not apply,” and then each of the “applies” and “not applies” piles was sorted into two more piles; the center pile was retained for “undecided.” This method resulted in five piles ranging from “almost always applies” to “rarely or hardly ever applies.” The within-item correlations for the five- and traditional AQS nine-pile sorts ranged from .95 to .99, supporting the simplified sorting technique.

Table 1.

TAS-45 Hotspot Cluster Groups and Items

| S | Group 1: warm, cuddly |

| • Hugs and cuddles against parent without being asked to do so | |

| • Relaxes when in contact with parent | |

| • Seeks and enjoys being hugged by parent | |

| • When crying or upset, is easily comforted by contact with parent | |

| T | Group 2: cooperative |

| • When parent asks child to do something, child understands what she wants--may or may not obey | |

| • Cooperates with parent and gives parent things if asked | |

| • Responds to positive hints from parent | |

| • Obeys when asked to bring or give parent something | |

| • When parent says “come here”, child obeys | |

| U | Group 3: enjoys company |

| • If asked, lets friendly adult strangers hold or share toys | |

| • A social child who enjoys the company of others | |

| • Enjoys being hugged or held by friendly adult strangers | |

| • Eager to join in with friendly adult strangers--does not wait to be asked | |

| • Enjoys copying what friendly adult strangers do | |

| V | Group 4: independent |

| • Often plays out of parent's sight | |

| • Is very independent | |

| • Fearless, gets into everything. | |

| • Usually finds something else to do when finished with an activity-- does not go to parent for help | |

| • Takes off and explores new things on own | |

| • Hardly ever goes to parent for any help, not even for minor injuries | |

| W | Group 5: attention seeker |

| • Tries to stop parent from giving affection to other people, including family members | |

| • When parent talks with anybody else, child wants parent's attention | |

| • Wants to be at the center of parent's attention | |

| • When child is bored, will go to parent looking for something to do | |

| • Child frequently wants parent's attention | |

| X | Group 6: upset by separation |

| • Is very clingy, stays closer to parent or returns more often than simply keeping track of parent's whereabouts | |

| • Gets upset if parent leaves and shifts to another place | |

| • Child does not try new things and always wants parent to help | |

| • Cries or tries to stop parent from leaving or moving to another place | |

| Y | Group 7: avoids others, does not socialize |

| • Soon loses interest in friendly adult strangers. | |

| • Turns away from friendly adult strangers and goes own way | |

| • If there is a choice, child prefers to play with toys rather than with friendly adults | |

| • When a new visitor arrives, child first ignores or avoids him/her | |

| Z | Group 8: demanding/angry |

| • When child cries, cries loud and long | |

| • When child sees something really nice to play with, child will fuss and whine or try to drag parent over to it | |

| • When parent does not do what child wants right away, child fusses, gets angry or gives up | |

| • Cries as a way of getting parent to do what is wanted | |

| • Cries often, regardless of how hard or how long | |

| D | Group 9: moody/unsure/“unusual” |

| • Seems lost, remote and/or disconnected | |

| • With parent, child suddenly changes moods--may go from being calm to upset, afraid or angry, or from nice to mean, or gets upset and then goes blank. Goes all floppy (limp) when held by parent | |

| • Child sometimes freezes, perhaps in an unusual position, for a few seconds. | |

| • Will go towards parent to give parent toys, but does not touch nor look at parent | |

| • Suddenly aggressive towards parent for no reason (for example, hits, slaps, pushes, or bites parent). | |

| • Easily becomes angry at parent |

To add items to tap attachment disorganization as described by Main and Solomon (1990), Kirkland's team started with a pool of 42 statements characterizing disorganized attachment behavior, narrowed the set to 12 items using MDS and facet cluster analysis, and selected six that were most feasible to observe in the field by data collectors. The six disorganization items constituted a ninth, “Disorganized” (“D”) hotspot.

Extensive ECLS-B field testing of all items resulted in replacing some that were infrequently observed or presented difficulties for field staff, and rewording most items to achieve a 6th to 8th grade reading level.

Each item has a hotspot weight. Each hotspot has a specific location triangulated from three orthogonal dimensions. The closer an item is to the center of the hotspot cluster, the greater the weight. The more distant from the center of the cluster, the smaller the weight. The weight is multiplied by the number of the pile it is sorted into, from applies most to applies least. Further computation produces Security and Dependence (distress proneness) factor scores equivalent to those obtained by the AQS, based on published criterion sorts (Waters & Deane, 1985). The computed value of each hotspot can be also plotted as a line graph of the nine hotspots to illustrate a child's individual profile of attachment behaviors. Refinements to the algorithm take into account missing data and items not used in a particular sort.

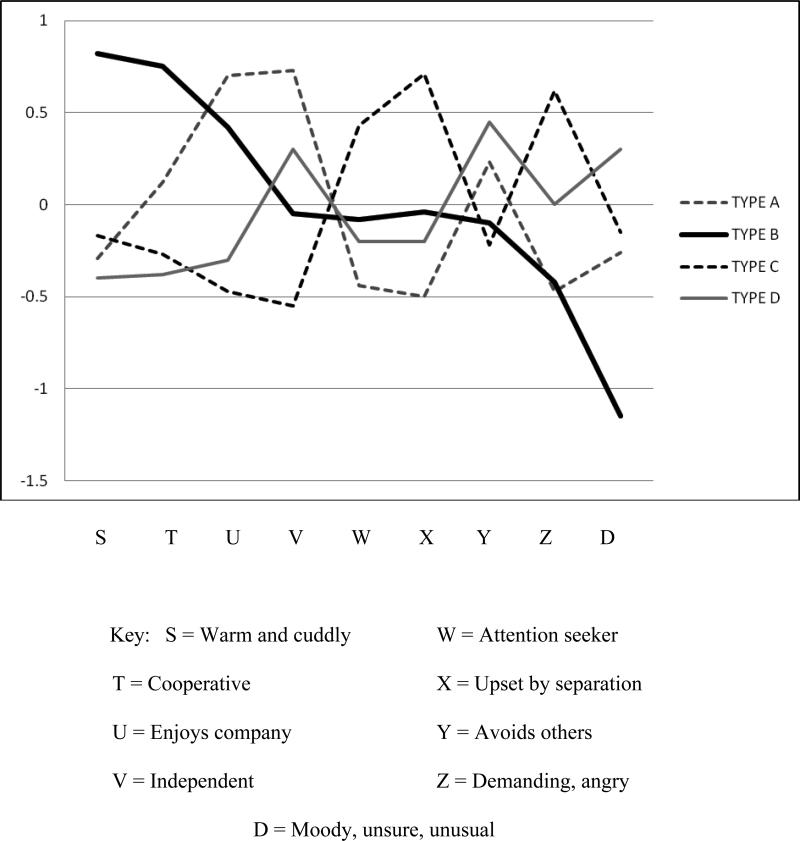

The profiles can be further evaluated according to the “distance” each has from profiles that are prototypically secure (Profile B), insecure-avoidant (Profile A), and insecure-ambivalent/resistant (Profile C). A formula for estimating a prototype for profiles with high levels of extreme, unusual, or unclear attachment behaviors (Profile D) was created for the ECLS-B study and is undergoing further refinement. Details are reported in Andreassen et al.(2006). Figure 1 illustrates prototypical profiles of the four attachment strategies. Profile B, secure, is high on warmth, cooperativeness, and sociability, and low on separation distress and avoidance of others. Profile A, avoidant, is high on sociability and independence and low on warmth and cooperativeness. Profile C, resistant-ambivalent, is low on sociability and independence, and high on attention seeking and separation distress. Profile D is high on moody, unusual, extreme, or unclear behaviors and would be expected to be most variable on the other hotspots, but elevated on the D hotspot relative to the A, B, or C attachment profiles.

Figure 1.

Hotspot Profiles of A, B, C and D Attachment Strategies

A computerized approach to the five-pile sort was developed so that observers could complete it speedily on a laptop computer after a 90-minute data collection visit. The ECLS-B version of the TAS-45 and computerized training modules have been available to any user through a free, though unsupported, website (http://www.suchandsuch.biz/tots/). The website did not, however, classify the profiles into best-fitting attachment classifications, generate Security or Dependence factor scores, or otherwise aid users who would use the TAS-45 in a research study. Continued refinement of the items and analysis software following the ECLS-B study resulted in the version of the TAS-45 described in the Method section.

We expect that the ECLS-B national data set will generate many attachment studies using the TAS-45, and that these will specifically support the validity of the measure. The first such study examined a subsample of same-sex twins (Roisman and Fraley, 2008). This study found a correlation between parenting quality, measured in a 10-minute semi-structured interaction task, and the TAS-45 Security factor of r = .19, p < .05. Roisman and Fraley note that this correlation is as strong as other, meta-analytically-derived associations between attachment security and parenting quality and that this “...represents promising evidence of its validity” (p. 838).

Arguably, the strongest validation of the TAS-45 would be an examination of how it performs relative to the AQS and SSP. In the absence of that standard, the approach modeled by Roisman and Fraley (2008) has utility. In the lieu of a more definitive test, the aim of the current study is to test similar, predicted associations between the TAS-45 and several aspects of concurrent toddler functioning.

Associations between Early Attachment Security and Child Functioning

There is strong evidence that the foundation for social-emotional competence and self-regulation skills is acquired in the earliest years of life within a child's primary caregiving relationships (Blair, 2002; Braungart-Rieker, Garwood, Powers, & Wang, 2001; Cassidy, 1994; Egeland, Pianta, & O'Brien, 1993; Siegel, 2001). The attachment relationship has implications for how well children learn to manage negative affect (Carlson & Sroufe, 1995). Insecure attachment strategies, particularly those involving avoidance and disorganization, have been associated with behavior problems largely in samples of children living in poverty (Erickson, Sroufe, & Egeland, 1985; DeKlyen & Greenberg,2008; Keller, Spieker, & Gilchrist, 2005; Munson, McMahon, & Spieker, 2001; Shaw & Vondra, 1995) rather than in low-risk, middle-class samples (Bates, Maslin, & Frankel, 1985; Erickson et al., 1985; Fagot & Kavanagh, 1990; Shaw & Vondra, 1995), suggesting that insecure attachment combined with the stresses associated with poverty amplify the risks for developing behavior problems. A meta-analysis across many studies found that children with early insecure-disorganized attachments to primary caregivers developed more externalizing (acting out, oppositional and defiant behavior, conduct problems) symptoms (van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1999).

Evidence is accumulating that securely attached children have also an early advantage in language development. Another meta-analysis across seven studies found that children with secure attachments, compared to children with insecure attachments from the same samples, had significantly higher language scores across a variety of standardized tests (van IJzendoorn, Dijkstra, & Bus, 1995, r = .28). These results were replicated in our own research involving children eligible for EHS (Spieker, Nelson, Petras, Jolley, & Barnard, 2003).

Based on the literature reviewed above, we hypothesized that the TAS-45 Security factor score and the D hotspot would be concurrently related to measures of the quality of mother-child interaction, child social problem behavior and competence, and child expressive and receptive language. We also hypothesized that the Dependency (distress proneness) factor score would not show these associations, providing evidence of discriminant validity for the variables generated by the TAS-45.

Method

Participants

Fifty nine mothers and their 18 (n = 15), 24 (n = 29) or 36 (n = 15) month-old children enrolled in a home-based EHS program were informed about the study by their home visitors and agreed to participate in the research home visit. Thirty four children (58%) were male and 25 (42%) were female. The mothers were ethnically and racially diverse, with 3.4% Native American, 10.2% Black, 22% Hispanic, 22% multi-racial, and 42.4% White. Mothers ranged in age from 16 to 40 years (M = 24.8, SD = 6.2).

A subset of 23 mothers and children completed two TAS-45 assessments, 13 at 18 and 24 months, and 10 at 24 and 36 months. These longitudinal data were combined to analyze test-retest stability.

Procedure

Data were collected during a 90-minute home visit. The data collector scheduled the visit at a time when the child would be rested and fed. The data collector, a stranger to the family, paid attention to toddler behavior that would inform her scoring of the TAS-45 from the moment of arrival. After obtaining informed consent, she asked the parent to leave the room and to return in a few minutes when called. The separation was three minutes unless the child cried. Following the separation and reunion, the parent and child played with a set of warm-up toys while the data collector set up the video equipment. The child language assessment, parent interview, and parent questionnaires were administered next. Toward the end of the visit the data collector gave a simple snack to the parent with the request, “Please share this snack with your child. Take as long as you like. Please let me know when you and your child are finished.” The entire activity was videotaped. Although the length of snack activities varied, all dyads were engaged for at least six minutes. The home visit protocol included activities to allow the data collector to observe child secure base behaviors. In addition to the separation and reunion, the data collector also casually asked the parent how the child reacted when the parent gave affection to other family members (unless directly observed). At the end of the visit, the data collector asked the child for a hug good-bye. Soon after the visit, the data collector completed the TAS-45 on a paper form in her car or at a nearby coffee shop.

Measures

Toddler attachment security

The development of the TAS-45 for use in the ECLS-B is described in detail by Andreassen, et al. (2006), and was summarized above. The current version has additional slight changes in item wording, an additional item in the D hotspot, a deleted item, and a simpler sorting procedure. Table 1 lists the 45 items according to their hotspot affiliations. In the sorting procedure used in this study, the 45 descriptive statements are presented in specific sets of three. The observer decides which of the three statements is “most like” and which is “least like” the child's behavior during the observation just completed. Three-way forced ranking techniques like these are called “trilemmas” (see Bimler, Kirland, Yuhara, Kurosaki, and Coxhead (2005) for analytic details). Trilemma examples are listed in Table 2. Each of the 45 statements appears in two trilemmas; there are 30 trilemmas in all. This forced-ranking technique is considerably simpler and faster than traditional Q-sort methodology or even the five-pile approach used in the ECLS-B. The new approach retains the ability to generate all of the variables available in the ECLS-B data set, including the nine hotspot scores, Security and Dependence factor scores, and the best-fitting ABCD classifications based on the overall shape of the profiles.

Table 2.

TAS-45 Trilemmas: Sorting Instructions and Examples

| Read the three statements in each trilemma, then mark the number of the statement that is most true, and the number of the statement that is least true, of the child just observed. | ||

| Most True | Least True | |

| — | — | 1 When child cries, cries loud and long. |

| 2 Obeys when asked to bring or give parent something | ||

| 3 Is very independent | ||

| — | — | 1 Responds to positive hints from parent. |

| 2 Soon loses interest in friendly adult strangers. | ||

| 3Child sometimes freezes, perhaps in an unusual position, for a few seconds. | ||

| — | — | 1 When parent asks child to do something, child understands what parent wants--may or may not obey |

| 2 Cries as a way of getting parent to do what is wanted | ||

| 3 Does not ask for parent's help | ||

| — | — | 1 Often plays out of parent's sight. |

| 2 When parent doesn't do what child wants right away, child fusses, gets angry, or gives up | ||

| 3 Relaxes when in contact with parent | ||

During the first stage of training, the third author and the study's data collector observed the on-line modules created for the ECLS-B field staff, passing the three computerized quizzes at a minimum pass rate of 80%. Next, they conducted joint pilot visits, completed the TAS-45 separately after the visit, and then discussed, item by item, the decisions they made. Computation of inter-coder agreement was not available at that time through the website but was estimated by comparing levels and shapes of resulting profiles. After data collection began, the third author accompanied the data collector on 11 visits, and both observers completed the TAS-45 independently. These were later scored for reliability with the assistance of Dr. Bimler. Pearson correlations for the Security and Dependence scores were .83 and .92, respectively. Pearson correlations for the nine individual hotspots that make up the profiles were as follows: S .87, T .65, U .91, V .91, W .87, X .86, Y .91, Z .57, and D .87. There was 100% agreement on the 11 attachment classifications (27.3% A and 72.7% B). The low reliability of the Z hotspot (see items in Table 1) suggests that it should not be used as a unique variable in analyses. However, the reliability of the Security and Dependence scores and the remaining hotspots were adequate.

This report focuses on the traditional scores found in the SSP or AQS literature and generated by the TAS-45: the Security and Dependence factor scores and the ABCD classifications. Although hotspot scores may be of interest for some kinds of research, for research on attachment, the Security factor score and the ABCD classifications are recommended (Andreaasen et al., 2006). In addition, associations with the D hotspot score are reported because of keen interest in measures and correlates of attachment disorganization.

Observed mother-child interaction

The first five minutes of the snack videotape were used to code mutuality in mother-child communication, in terms of opening and completing “circles of communication” as described by Greenspan (1999, p. 332). Criteria were further refined using Wetherby and Prizant (2002)'s definitions of the form, function and use of intentional communication. The Circles of Communication coding protocol was developed by the authors with the technical assistance of P.Mangold in using INTERACT (Mangold, 2007) software for this project. The purpose of the coding system is to capture both verbal and non-verbal communication attempts by both the parent and toddler, and the degree of reciprocity present between them during the snack-sharing activity. Interactions consisted of attempts by either the parent or the toddler to engage the other's attention. Sometimes attempts successfully elicited responses; other times there was no response, meaning there was a break in the flow of communication. Some breaks in communicative interactions were very brief, and a second or third attempt immediately followed. Other communicative attempts led to single or multiple back and forth exchanges of gestures, vocalizations and/or verbalizations. A single back and forth exchange in which the first party initiates contact, is responded to, and then breaks the exchange, is a “circle of communication.” A series of back and forth contingent responses between the parent and toddler constitute “chains” of circles of communication.

The coding protocol used a decision-making tree that required that any act met the following criteria before being coded as part of a “circle of communication”:

The act must be an attempt to communicate to the other (i.e., to draw the other person's attention either to oneself, to an object, an activity; to encourage or discourage the other's behavior; or to prolong an interaction);

The act must include a gesture, vocalization or verbalization, or a combination thereof; The act must be directed towards the other person. In the absence of eye contact, a gesture and/or vocalization must clearly be in reference to the other person's activity, to an emotion, or used to call attention to an object or event. It is important to note that simply handing an object to the other person in the context of snack without a clear vocal, gestural, or verbal attempt to obtain or direct their attention did not qualify as a communicative act in this coding protocol.

Coders blind to all other data were trained to apply these criteria to the videotaped interactions of the dyad during snack. Inter-rater reliability was based on double-coding of 29% of the recordings. Cohen's kappa for all parent and child “Start” and “Stop” codes within 30 seconds was .65. Percent agreement for responses by parent was an acceptable 89%; percent agreement for child responses was an acceptable 81%.

The following variables were used in these analyses: Total number of attempts to communicate to the other person, called “Parent Starts” and “Child Starts”; total number of non-responses to the other person's initiation attempts, called “Parent Stops” and “Child Stops”; and “Mutuality Count,” computed as the sum of the child's responses to maternal communicative attempts plus the sum of the mother's responses to the child's communicative attempts (r = .97, p < .001).

Child problem behavior and social competence

The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA Version 1.0; Briggs-Gowan & Carter, 2001) is a screening tool used to identify young children who may have social-emotional or behavioral problems or delays in competence. The BITSEA consists of 60 items drawn from the Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA) (Carter & Briggs-Gowan, 2000). The BITSEA has 49 Problem items (alpha = .83) and 11 Competence items (alpha = .66). Items are rated on the following three-point scale: (0) Not true/rarely, (1) Somewhat true/sometimes, and (2) Very true/often. The BITSEA was validated on a diverse community sample of over 1200 families, 24.7% non-white minorities, and a small early intervention sample (N = 233). We used the Problem and Competence total scores.

Child language

The Preschool Language Scale Fourth Edition (PLS-4: Zimmerman, Steiner, & Pond, 2002) measures young children's spoken expressive language and receptive language (which Zimmerman and colleagues call “auditory comprehension”) from birth to six years of age. The fourth edition is based on the latest research and input from clinicians around the U.S. The PLS-4 was validated on a U.S. sample of 1,500 largely middle class children birth through 6 years, including children with disabilities. Minorities constituted 39.1% of the sample. The PLS-4 utilizes parent report, direct observation, and direct assessment of children's responses to structured language tasks. We used the standard scores for the expressive and receptive communication scales.

Results

Analysis Plan

Using the cross-sectional sample (N = 59), we first examined descriptive statistics for the major attachment variables, the five mother-child interaction variables, and the four child outcome variables. We determined whether mean differences in any variable by child age necessitated controlling for child age in subsequent analyses. Test-retest correlations and stability of attachment factor scores and classifications were calculated using the longitudinal sample (n = 23). Next we examined the inter-correlations among the TAS-45, mother-child interaction, and child problem, competence, and language outcome variables. If both a mother-child interaction variable and the attachment Security factor were associated with a child outcome, we conducted a hierarchical regression analysis predicting that outcome, entering Security on the last step in order to determine if attachment was uniquely predictive after controlling for the quality of parent-child interaction.

Descriptive Findings

The ABCD attachment classification distribution was 24% A, 73% B, 3.4% C and 0% D. Examination of the D hotspot scores revealed four outliers and six extreme scores. ABCD classifications were then recalculated with those cases with D hotspot outlying or extreme score being reclassified, resulting in a Profile D classification. Using this algorithm, the revised distribution was 13.6% A, 67.8% B, 3.4% C, and 15.3% D. Three of the new “D” classifications had originally been classified Profile B, and six had originally been classified as Profile A.

We compared mean scores on the TAS-45 D hotspot and the Security and Dependence factor scores for the three age groups: 18, 24 and 36 months. No significant differences emerged. Thus, we proceeded with our plan to combine data across the three age groups for all of the TAS-45 variables. Table 3 presents descriptive statistics for the D hotspot and the Security and Dependence factor scores for the whole sample and by TAS-45 ABCD profiles.

Table 3.

Mean, Standard Deviation, and Range for TAS-45 Hotspot and Summary Scores for Total Sample and by ABCD Classification

| M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (N = 59) | |||

| D Hotspot | -.13 | .32 | -1.37 - .036 |

| Security Factor | .15 | .07 | -.05 - .24 |

| Dependence Factor | -.02 | .07 | -.17 - .13 |

| A Profile (n = 8) | |||

| D Hotspot | -1.16 | .11 | -1.30 - -.96 |

| Security Factor | .10 | .03 | .04 - .13 |

| Dependence Factor | -.08 | .04 | -.12 - -.01 |

| B Profile (n = 40) | |||

| D Hotspot | -1.26 | .06 | -1.37 - -1.01 |

| Security Factor | .19 | .04 | .08 - .24 |

| Dependence Factor | .00 | .05 | -.08 - .13 |

| C Profile (n = 2) | |||

| D Hotspot | -1.22 | .08 | -1.29 - -1.17 |

| Security Factor | .09 | .04 | .07 - .12 |

| Dependence Factor | .08 | .03 | .06 - .10 |

| D Profile (n= 9) | |||

| D Hotspot | -.47 | .33 | -.93 - .04 |

| Security Factor | .05 | .08 | -.05 - .17 |

| Dependence Factor | -.09 | .08 | -.17 - .06 |

We also compared the mean scores across age group for the five mother-child mutual communication variables, the BITSEA problem and competence scores, and the PLS-4 expressive and receptive language standard scores. The means for the five circles of communication variables were compared across the three ages. Mutuality count tended to vary by child age (F (2, 44) = 3.14, p < .10, means (standard deviations) were 35.9 (21.9), 42.0 (23.1), and 59.4 (15.5) seconds for 18, 24 and 36 month-olds, respectively). Post-hoc group comparisons also did not reach significance so we did not control for age in analyses with this variable. There were no mean differences on the two BITSEA scores across the three age groups. There were significant differences across age group on the standardized language scores (for expressive language, F (2, 55) = 6.2, p < .01, means (with standard deviations in parentheses) were 110.9 (15.1), 102.1 (15.3), and 90.8 (17.2) for 18, 24 and 36 month-olds, respectively; for receptive language, F (2, 55) = 4.2, p < .05, means (standard deviations) were 106.4 (18.9), 96.6 (15.3), and 86.8 (17.2). For this reason, age group is controlled in analyses involving the two language scores. Descriptive statistics for the mother-child interaction variables and child outcome variables in the cross sectional sample are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mean, Standard Deviation, and Range for Circles of Communication Parent-Child Interaction Scores and Correlations with TAS-45 D Hotspot and Security and Dependence Factor Scores

| Parent Starts N = 45 | Child Starts N = 45 | Parent Stops N = 45 | Child Stops N = 45 | Mutuality Count N = 45 | BITSEA Problem N = 55 | BITSEA Competence N = 55 | Expressive Comm.a N = 57 | Receptive Lang.a N = 57 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 13.8 | 5.3 | 4.0 | 14.9 | 44.9 | 15.8 | 18.1 | 101.5 | 96.6 |

| SD | 6.4 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 6.0 | 22.6 | 9.7 | 3.0 | 17.1 | 19.6 |

| Range | 3 – 29 | 0 – 14 | 0 – 13 | 4 – 29 | 4 – 92 | 1 – 43 | 8 – 22 | 62 – 135 | 50 – 135 |

| D Hotspot | .28+ | -.21 | -.26+ | .30* | -.21 | .59*** | -.55*** | -.27* | -.43*** |

| Security factor | -.26+ | .15 | .15 | -.27+ | .35* | -.64*** | .61*** | .32* | .41*** |

| Depend. factor | -.15 | -.01 | -.15 | -.11 | -.07 | -.35 | .25+ | -.08 | -.14 |

| Parent starts | -.53*** | .88*** | -.27+ | -.03 | .02 | -.15 | .02 | -.15 | |

| Child starts | -.27+ | .58*** | .26+ | -.03 | .15 | .12 | .17 | ||

| Parents stops | -.43** | .02 | .01 | -.15 | .09 | -.04 | |||

| Child stops | .18 | -.02 | .19 | -.02 | -.03 | ||||

| Mutuality count | -.22 | .35* | .47*** | .38* | |||||

Partial correlation controlling for child age

p < .10

p < .05

p<.01

p<.001

Stability of Attachment in the Longitudinal Sample

The same D hotspot cutoff score for assigning the D classification was used in the longitudinal sample, resulting in an ABCD distribution that was 4.3% A, 69.6% B, 0% C, and 26.1% D, at Time 1, and 0% A, 73.9% B, 0% C, and 26.1% D, at Time 2. There was one shift from A to B, two shifts from B to D, and two from D to B.

The Security factor score was moderately stable, (r = .54, p < .01), as was the Dependence factor score, (r = .58, p < .01), and they were positively correlated with each other at each time point, (r's = .65 and .57, p < .01). The D hotspot score was very stable, (r = .84, p < .001), as would be expected with the majority of the sample exhibiting little disorganization.

Associations Among TAS-45 Scores and Parent-Child Interaction and Child Outcomes

Table 4 presents the correlations between the mother-child interaction variables and the D hotspot and the Security and Dependence factor scores, and between these variables’ and the BITSEA competence and problem scores and PLS-4 child expressive and receptive language scores. Mothers with more initiations had children who had marginally higher D hotspot scores and lower Security factor scores. Children with higher rates of stopping circles of communication had higher D scores and marginally lower Security factor scores. Mutuality count was positively related to the child Security factor score. The Dependence factor score was unrelated to any mother-child interaction variable.

The Security factor score was significantly associated with expressive and receptive language, controlling for child age. The D hotspot was related to both language scores, and the Dependence factor score was unrelated to the child language scores.

There were several associations between the TAS-45 variables and the BITSEA scores. Children who were lower on the Security and Dependence factor scores and higher on the D hotspot score had more mother-reported behavior problems and lower competence. Overall, the associations for the Dependence factor appeared to be weaker than those for security or disorganization.

Of the five mother-child interaction variables, only mutuality count was associated with expressive and receptive language (controlling for child age). No mother-child interaction variables were related to BITSEA behavior problems, but mutuality count was associated with the BITSEA competence score.

As shown in Table 4, three of four child variables were associated with both the Security factor score and mother-child interaction mutuality count: BITSEA competence and PLS-4 expressive and receptive language. Therefore, we examined the unique contribution of the Security factor score to the prediction of these three dependent variables in hierarchical regression analyses. Table 5 presents the results of the hierarchical regression predicting to child competence from circles of communication mutuality count and the TAS-45 Security factor score. Child security contributes significant unique variance to the BITSEA competence score (ΔR2 = 0.30), and mutuality count no longer accounts for significant variance when security is in the model.

Table 5.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting Child BITSEA Competence (N = 43)

| Variable | B | SE B | β | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||

| Mutuality count | .05 | .02 | .35* | .10 |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Mutuality count | .02 | .02 | .11 | |

| Security factor | 26.00 | 5.53 | .61*** | .40 |

p < .05

p < .001

Table 6 presents the results of the hierarchical regression analysis predicting expressive language from child age, mutuality count and the TAS-45 Security factor score. In this case, child security did not add significantly to the variance accounted for by child age and mutuality count. Finally, Table 7 presents the results of the hierarchical regression analysis predicting receptive language from child age, mutuality count and the TAS-45 Security factor score. Child security contributes significant unique variance to the receptive language score (ΔR2 = 0.09), and in the final model the contributions of child age and mutuality count both remain significant.

Table 6.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting Child Expressive Language (N = 44)

| Variable | B | SE B | β | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||

| Child age | -1.25 | .37 | -.46** | .19 |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Child age | -1.68 | .36 | -.62*** | |

| Mutuality count | .33 | .10 | .45*** | .35 |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Child age | -1.73 | .36 | -.64** | |

| Mutuality count | .30 | .10 | .41** | |

| Security factor | 34.46 | 30.05 | .15 | .36 |

Note.

p < .01

p < .001

Table 7.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting Child Receptive Language (N = 44)

| Variable | B | SE B | β | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||

| Child age | -.92 | .43 | -.31* | .08 |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Child age | -1.33 | .43 | -.45** | |

| Mutuality count | .31 | .12 | .39** | .19 |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Child age | -1.46 | .41 | -.49** | |

| Mutuality count | .23 | .11 | .30* | |

| Security factor | 82.82 | 34.60 | .33* | .28 |

p < .05

p < .01

Discussion

This study examined the variables generated by the TAS-45 measure of attachment in a small sample of toddlers in one Early Head Start program for preliminary evidence of the validity of the TAS-45. Below we compare features of the TAS-45 with both the AQS and SSP, and evaluate associations between TAS-45 attachment variables and measures of mother-child interaction, child problem behavior and competence, and child expressive and receptive language.

TAS-45: Comparisons with the AQS and SSP

The TAS-45, although aided in its development by analyses of AQS data sets, is not a reduced or adjusted version of the AQS. Rather, AQS data facilitated the identification and mapping of the TAS-45 “hotspots” using multidimensional scaling. It turns out that there can be many variations on the items that will still cluster around these conceptual hotspots because there are only a certain number of ways to represent specific locations triangulated from three orthogonal dimensions (J. Kirkland, personal communication, January 23, 2009).

The seven items in the D hotspot scale were not in the original AQS. They were selected from descriptions of disorganized behavior discussed by Main and Solomon (1990). The items were not meant to be an exhaustive representation of disorganized/disoriented behavior. For instance, behaviors obviously indicative of fear of approaching the parent were not included, with the explanation that the developers did not want rating the child's behavior to be too disturbing for paraprofessional data collectors (Andreassen et al., 2006). The items were selected for objectivity and feasibility in the field. They clearly reflect observable, atypical behavior, which, if attachment-related, would be disorganized, but which could also have other neurological etiologies (Pipp-Siegel, Siegel, & Dean, 1999) or reflect some other developmental issue, such as symptoms of autism (Capps, Sigman, & Mundy, 1994). The D hotspot did have consistent associations with low mutuality in mother-child interaction, mother report of behavior problems and low social competence, and less proficient child language. Future validation of the D hotspot should include comparisons of normative samples with those in which the children are known to have experienced attachment-related traumas, as well as direct assessment of disorganized/disoriented behavior and atypical attachment strategies in the SSP. A deeper examination of these issues was beyond the scope of this study, but it is possible that the ECLS-B data and other existing data sets can be analyzed, and that future studies can be designed for this purpose.

It is also important to acknowledge that the indicators of “disorganization” in the TAS-45 could be further informed by developmental theory and what we have learned about atypical attachment strategies in the SSP for children after infancy. In the future, different versions of the TAS-45 might be needed for infants and younger toddlers versus older toddlers and preschoolers. Older preschoolers utilize an expanding repertoire of self-protective strategies, as described by Crittenden (1992, 2008). For example, toddlers and preschoolers coping with adverse home environments begin to use strategies that inhibit negative affect, such as compulsive compliance, compulsive caregiving, or coy expressions that might be mistaken for secure strategies unless the items take into account parental behavior, and observers are trained accordingly. The two current approaches to classifying preschool-age behavior in the SSP differ quite dramatically on the identification of secure and atypically insecure classifications (Spieker & Crittenden, in press). The TAS-45 cannot be fully validated without being informed by a comparison of these methods and the theoretical differences they reflect (Thompson & Raikes, 2003).

Given the small sample size, we were not primarily concerned with the ABCD attachment classifications generated by the TAS-45 for these validity analyses. Future studies may have this requirement, and our results suggest that this classification variable needs further refinement. We identified no D classifications in this sample when we computed the TAS-45 variables using the currently available instructions (Bimler & Kirkland, 2004). In response, we created sample-specific D classifications by identifying the D hotspot outlying scores and setting the cut point for a D classification so that all outliers would fall within the range for a D classification. The resulting distribution, 13.6% A, 67.8% B, 3.4% C, and 15.3% D, had fewer insecure classifications compared to that reported for a meta-analysis of low-income American children: 16.6% A, 48.1% B, 10.2% C, 10.2% D (van IJzendoorn et al., 1999). In contrast, even without this adjustment in the larger, diverse ECLS-B study, the TAS-45 generated a very typical distribution of ABCD attachment classifications, 16.3% A, 61.1% B, 8.9% C, 13.5% D (Andreassen et al. 2006), closely corresponding to the published meta-analysis for normative samples: 14.8% A, 61.7% B, 8.7% C, and 14.8% D (van IJzendoorn et al., 1999). We are currently communicating with the developers of the TAS-45 so that future releases of the program address this issue. One possibility to consider is whether the AQS items identified by van Bakel & Riksen-Walraven (2004), together with the TAS-45 D hotspot items, can be mapped more specifically to identify disorganization, at least in the youngest children (J. Kirkland, personal communication, May 4, 2009). In the meantime, it appears that the Security factor scores and the D hotspot scores as they are currently computed demonstrate preliminary validity for use as dimensional variables in attachment research with 18 to 36-month old children.

TAS-45: Associations with Mother-Child Mutuality and Child Outcomes

The pattern of associations found in this small study of 59 Early Head Start 18- to 36-month old children supports the validity of the TAS-45 as a measure of attachment strategies in relation to their mothers during mildly stressful home visits. First, we found predicted associations between the TAS-45 Security factor score and observations of mother-child interaction, specifically communicative mutuality during a shared snack. Sensitive, responsive caregiving has consistently had a causal association with attachment security in the literature (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, 2003), although not necessarily a sufficient or exclusive one (Thompson & Raikes, 2003). Mothers’ sensitivity and responsiveness to children's signals increase and expand circles of communication with a very young child. Consistent with Roisman and Fraley's (2008) finding in the ECLS-B data of a modest correlation between parenting quality, measured in a 10-minute semi-structured interaction task, and the TAS-45 Security factor, we found that maternal sensitivity and responsiveness in a snack interaction are associated with TAS-45 security. It is an indication of discriminant validity that the Dependence factor score, though associated with Security, was not associated with any of the mother-child interaction circles of communication variables. The Dependence factor reflects, to some degree, the child's temperamental tendency to express negative affect and distress, but these potent signals were not associated with more mutual communication between child and mother.

All three TAS-45 attachment variables were associated with the mother-report BITSEA problem and competence scales. The Security factor and D Hotspot scores had the strongest associations, and the Dependence factor was marginally associated with competence. In post-hoc regressions we included all three TAS-45 attachment variables to predict the BITSEA problem and competence scores. For competence, only the Security factor score was uniquely predictive; the Dependence and D hotspot scores adding a non-significant 1% and 3% of the variance, respectively. For the problem score, the D hotspot added a marginally significant 3.7% of the variance, and the Dependence factor score added nothing.

As predicted, we found associations between the TAS-45 Security factor score and PLS-4 standardized scores for expressive and receptive language. The Dependence factor score was unrelated to child language, again supporting the discriminant validity of the TAS-45 variables. The D Hotspot score also showed expected associations. In post-hoc regressions we included both the Security and D Hotspot scores to predict expressive and receptive language. The addition of the D Hotspot accounted no significant additional variance. This is not surprising, given a negative correlation between the Security factor score and the D hotspot (r = -.71, p < .001).

Both mutuality in mother-child interaction, as measured by the count of completed circles of communication, and security of attachment, as measured by the TAS-45, were associated with mothers’ reports of child competence and child expressive and receptive language. The first regression indicated that mutuality count was no longer a significant predictor of competence when the TAS-45 Security factor score was also in the model. Thus, child secure base behavior, observed in the data collection visit, shares significant variance with maternal report of competence over the past month, and second-by-second analysis of mother child interaction quality does not add to the predictive model. In contrast, in the second regression model mother-child mutuality accounted for virtually all of the variance in expressive language. We can only speculate that more participation in mutual circles of communication provides practice for the use of expressive communication and the quality of secure base behavior does not add additional benefit for learning expressiveness. Finally, the third regression analysis demonstrated that the Security factor score accounted for unique variance in the prediction of receptive language after controlling for the contributions of child age and mother-child dyadic mutuality, which remained significant with all variables in the model. In this small Early Head Start sample, older children had lower receptive language scores than younger children, suggesting a cumulative effect of the environment and perhaps the increasing contribution of genetic factors as well. Within age groups, both quality of mother-child interaction and security of attachment were associated with better language comprehension, with a considerable amount of unique variance accounted for by each of these aspects of the mother-child relationship. Together these three regression analyses showed a somewhat nuanced pattern of joint effects of mother-child dyadic mutuality and TAS-45 security on three different child outcome variables, and provide some support for the validity of the TAS-45. We find that attachment security and dyadic mutuality are related but not identical. Their unique contributions vary in understandable ways according to the child outcome: security to mothers’ ratings of competence, mutuality to child expressiveness, and both security and mutuality to child comprehension.

Limitations

Although we present evidence for the validity of the TAS-45 as a measure of attachment, this preliminary study has important limitations. All analyses were cross-sectional and the child age range fairly broad. Our age range was comparable to the range for the age 2 sample of the ECLS-B, 16 – 39 months, with the caveat that only 22% of the ECLS-B children were actually younger or older than 23 - 25 months at the time of the observation. Nevertheless, child age across this range was not associated with dramatic variations in the TAS-45 variable distributions (Andreassen et al., 2006). van IJzenddorn et al. (2004) reported that the AQS had stronger associations with the SSP for children younger than 18 months compared to older children, but child age did not moderate the association of the AQS with sensitivity. Future validity studies need to address the extent to which the TAS-45 is valid for children across the age range of 12 to 42 months.

Our measure of child problem behavior and competence was based on maternal report. Although mothers were instructed to think of their child's behavior over the past month, and observers were instructed to base their TAS-45 scoring only on behavior observed or specifically inquired about during the home visit, it is possible those maternal reports on the BITSEA were influenced by child behavior during the home visit, or that TAS-45 observers were influenced in their ratings by their having collected the maternal reports. Either way, this contamination would result in inflating the associations between the TAS-45 and the BITSEA.

Evidence of validity of the TAS-45 would certainly have been enhanced if we had also found agreement with concurrent Strange Situation and AQS assessments, but these activities were beyond our resources. The sample was small. For our sample sizes of 45 for the mother-child interaction analyses and 57 for the language analyses, the power to detect “true” effect sizes was .37 and .59, respectively, based on meta-analyses in the literature (r = .24 for the association between parental sensitivity and attachment security [De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997], and r = .28, for the association between attachment security and language [van IJzendoorn et al., 1995]). A more serious limitation relates to the validation measures themselves. We cannot rule out that the pattern of associations is competence related and not the result of attachment, per se, despite the fact that we expected to find this pattern of results based on the attachment meta-analyses in the literature. As Thompson (2008) has cautioned, a current challenge to attachment theory is to “clarify the expectations for which the theory can be held accountable in the context of proliferating mini-theories about how security is associated with antecedent and later functioning” (p. 288). Finally, there is the issue of how much secure-base behavior can actually be observed in the home. This issue, which also pertains to the AQS, has been summarized by Solomon and George (2008) and is the reason why Posada, Kaloustian, Richmond and Moreno (2007) recommend conducting AQS observations in different naturalistic contexts, including outside of the home, for relatively long periods of time. Our solution, and the solution of others, was to provide a few semi-structured events to assure activation of the child's attachment system (van IJzendoorn, et al., 2004) but undoubtedly longer observation periods would enhance the validity of the TAS-45.

Applications to Practice

The TAS-45 appears to be a useful measure for EHS programs to assess the quality of child-parent attachment. Its focus on child attachment strategies provides staff with a tool to reflect on the parent-child attachment, and to wonder with parents about the meaning of their child's behaviors, a strategy that may promote parental reflective capacity (Slade, Sadler, & Mayes, 2005). The association between TAS-45 attachment security and dyadic mutuality in circles of communication may provide a second entry into intervention, as parents can be supported by their EHS service provider to “complete circles” with their child for the purposes of enhancing language and child learning, which may also contribute to child attachment security (e.g., Klein, 1996). The focus on circles of communication also lends itself to video-feedback techniques, which have been shown to enhance both parental sensitivity and attachment security in fairly brief, more behaviorally focused interventions (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, 2003; Cooper, Hoffman, Powell, & Marvin, 2005; Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2008; Velderman, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Juffer, & van IJzendoorn 2006) that might also be very appropriate for use by EHS programs. Finally, the TAS-45 has proved to be a useful tool for reflective practice and professional development. Our EHS project partners believe the TAS-45 can do more than document attachment processes within EHS programs. The TAS-45 provides an observational frame for home visitors to detect and reflect with each other, their supervisors, and eventually the families themselves, on the meaning of the 45 attachment and exploration behaviors for children, parents, and parent-child relationships (Condon & Spieker, 2008).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the Department of Health and Human Services Administration on Children and Families, 90YF0048; and the National Institutes of Health through the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, 5 T32 RR023256-02, and the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, P30-HD02274.

References

- Advisory Committee on Services for Families with Infants and Toddlers . Statement of the Advisory Committee on Services for Families with Infants and Toddlers. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families; Washington, D.C.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, NJ: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C, Fletcher P, Park J. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B) Psychometric report for the 2-year data collection (NCES 2006-045) U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; Washington D.C: 2006. Toddlers Security of Attachment Status. pp. 8–1.pp. 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C, West J. Measuring socioemotional functioning in a national birth cohort study. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2007;28:627–646. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:195–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates J, Maslin C, Frankel K. Bretherton I, Waters E, editors. Attachment security, mother-child interaction, and temperament as predictors of behavior-problem ratings at age 3 years. Growing points of attachment theory and research Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985. pp. 167–193. Serial No. 209. [PubMed]

- Belsky J, Fearon R. Infant-mother attachment security, contextual risk, and early development: A moderational analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:293–310. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Rovine M. Temperament and attachment security in the Strange Situation: An empirical rapprochement. Child Development. 1987;58:787–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bimler D, Kirkland J. Unifying versions and criterion sorts of the Attachment Q-Set with a spatial model. Canadian Journal of Infant Studies. 2002;9:2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bimler D, Kirkland J. The ABC(D) of the TAS-45 (Toddler Attachment Set – 45): A lay figure's guide to analysis and interpretation of TAS-45 data (version 2.2) Massey University; New Zealand: 2004. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Bimler D, Kirkland J, Yuhara N, Kurosaki M, Coxhead E. “Trilemmas”: Characterizing the Japanese concept of “amae” with a three-way forced-ranking technique. Quality & Quantity. 2005;39:779–800. [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children's functioning at school entry. American Psychologist. 2002;57:111–127. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block J. The Q-sort method in personality assessment and psychological research. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1961. Reprinted in 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Braungart-Rieker JM, Garwood MM, Powers BP, Wang X. Parental sensitivity, infant affect, and affect regulation: Predictors of later attachment. Child Development. 2001;72:252–270. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS. The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA) Manual. Version 1.0. Yale University; New Haven, Connecticut: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Capps L, Sigman M, Mundy P. Attachment security in children with autism. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EA, Sroufe LA. Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Contribution of attachment theory to developmental psychopathology. Developmental Psychopathology, Vol. 1: Theory and methods. Wiley series on personality processes. 1995. pp. 581–617.

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ. The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA) University of Massachusetts Boston Department of Psychology; Yale University; Boston, MA., New Haven, CT: 2000. Unpublished Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Emotion regulation: influences of attachment relationships. Monograph of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(2-3):228–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cassidy J, Marvin RS, the MacArthur Attachment Working Group of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Network on the Transition from Infancy to Early Childhood . Attachment organization in preschool children: procedures and coding manual. The Pennsylvania State University; 1992. Unpublished coding manual. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Marvin RS, the MacArthur Attachment Working Group of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Network on the Transition from Infancy to Early Childhood . Attachment organization in preschool children: procedures and coding manual. The Pennsylvania State University; 1992. Unpublished coding manual. [Google Scholar]

- Condon MC, Spieker SJ. It's more than a measure: Reflections on a University-Early Head Start Partnership. Infants & Young Children. 2008;21(1):70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G, Hoffman K, Powell B, Marvin R. The Circle of Security intervention: Differential diagnosis and differential treatment. In: Berlin L, Ziv Y, Amaya-Jackson L, Greenberg MM, editors. Enhancing early attachments: Theory, research, intervention and policy. Guilford Publications; New York: 2005. pp. 127–151. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM. Children's strategies for coping with adverse home environments: An interpretation using attachment theory. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1992;16:329–343. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90043-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM. The Preschool Assessment of Attachment Coding Manual. Family Relations Institute; Miami, FL: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM. Raising parents: Attachment, parenting, and child safety. Willan Publishing; Portland, OR: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- DeKlyen M, Greenberg MT. Attachment and psychopathology in childhood. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 2nd Edition Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 637–697. [Google Scholar]

- De Wolff MS, van Ijzendoorn MH. Sensitivity and attachment: a meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development. 1997;68:571–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Pianta R, O'Brien MA. Maternal intrusiveness in infancy and child maladaptation in early school years. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson M, Sroufe L, Egeland B. Bretherton I, Waters E, editors. The relationship between quality of attachment and behavior problems in preschool in a high-risk sample. Growing points of attachment theory and research Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985. pp. 147–166. Serial No. 209. [PubMed]

- Fagot BI, Kavanagh K. The prediction of antisocial behavior from avoidant attachment classification. Child Development. 1990;61:864–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenichel E. Infant mental health and social policy. In: Osofsky JD, Fitzgerald HE, editors. WAIMH handbook of infant mental health Volume 4 Infant Mental Health in groups at high risk. Four. Wiley; New York: 2000. pp. 485–520. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL, Boyle DE. Attachment in US children experiencing nonmaternal care in the early 1990s. Attachment & Human Development. 2008;10:225–261. doi: 10.1080/14616730802113570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan S. Building Healthy Minds. Perseus Publishing; Cambridge, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, editors. Promoting positive parenting: An attachment-based intervention. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Keller TE, Spieker SJ, Gilchrist L. Patterns of Risk and Trajectories of Preschool Problem Behaviors: A Person-Oriented Analysis of Attachment in Context. Development & Psychopathology. 2005;17:349–384. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland J, Bimler D, Drawneek A, McKim M, Schölmerich A. An alternative approach for the analyses and interpretation of attachment sort items. Early Child Development and Care. 2004;174:701–719. [Google Scholar]

- Klein PS. Early Intervention: Cross-Cultural Experiences with a Mediational Approach. Garland Publishing, Inc.; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Solomon J. Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In: Greenberg MT, editor. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1990. pp. 121–160. [Google Scholar]

- Mangold P. INTERACT Software (Version 8.1) Mangold International GmbH; Arnstorf, Germany: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mann TL. Promotinog the mental health of infants and toddlers in Early Head Start: Responsibiltiies and partnerships. Zero to Three. 1997;18(2):37–40. [Google Scholar]

- McCartney K, Owen MT, et al. Testing a maternal attachment model of behavior problems in early childhood. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2004;45:765–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisset CE, Barnard KE, Greenberg MT, Booth CL. Environmental influences on early language development: The context of social risk. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:127–149. [Google Scholar]

- Munson JA, McMahon RJ, Spieker SJ. Structure and variability in the developmental trajectory of children's externalizing problems: Impact of infant attachment, maternal depressive symptomatology, and child sex. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:277–296. doi: 10.1017/s095457940100205x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipp-Siegel S, Siegel CH, Dean J. Atypical attachment in infancy and early childhood among children at developmental risk. II. Neurological aspects of the disorganized/disoriented attachment classification system: differentiating quality of the attachment relationship from neurological impairment. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1999;64(3):25–44. doi: 10.1111/1540-5834.00032. discussion 213-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada G, Kaloustian G, Richmond MK, Moreno A. Maternal secure base Support and preschoolers’ secure base behavior in natural environments. Attachment & Human Development. 2007;9:393–411. doi: 10.1080/14616730701712316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Fraley RC. A behavior-genetic study of parenting quality, infant attachment security, and their covariation in a nationally representative sample. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:831–839. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Vondra JI. Infant attachment security and maternal predictors of early behavior problems: A longitudinal study of low-income families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:335–357. doi: 10.1007/BF01447561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel DJ. Toward an interpersonal neurobiology of the developing mind: Attachment relationships, “mindsight,” and neural integration. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Sadler LS, Mayes LC. Minding the Baby: The promotion of attachment security and reflective functioning in a nursing/mental health home visiting program. In: Berlin LJ, Ziv Y, Amaya-Jackson L, Greenberg MT, editors. Enhancing early attachments: Theory, research intervention, and policy. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. pp. 152–177. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J, George C. The measurement of attachment security and related constructs in infancy and early childhood. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of Attachment. 2nd Ed. Guilford; New York: 2008. pp. 383–416. [Google Scholar]

- Spieker SJ, Crittenden PM. Comparing two classification methods applied to preschool Strange Situations. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. doi: 10.1177/1359104509345878. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieker SJ, Nelson DC, Petras A, Jolley SN, Barnard KE. Joint influence of child care and infant attachment security for cognitive and language outcomes of low-income toddlers. Infant Behavior & Development. 2003;26:326–344. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Measure twice, cut once: Attachment theory and the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. Attachment & Human Development. 2008;10:287–297. doi: 10.1080/14616730802113604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Raikes HA. Toward the next quarter-century: Conceptual and methodological challenges for attachment theory. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:691–718. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bakel HJA, Riksen-Walraven JM. AQS security scores: What do they represent? A study in construct validation. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2004;25:175–193. [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn M, Dijkstra J, Bus A. Attachment, intelligence, and language: A meta-analysis. Social Development. 1995;4:115–128. [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Schuengel C, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Disorganized attachment in early childhood: meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequelae. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:225–249. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Vereijken CM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Riksen-Walraven JM. Assessing attachment security with the Attachment Q Sort: meta-analytic evidence for the validity of the observer AQS. Child Development. 2004;75:1188–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velderman MK, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F, van IJzendoorn MH. Effects of attachment-based interventions on maternal sensitivity and infant attachment: differential susceptibility of highly reactive infants. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:266–274. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E. Attachment Behavior Q-Set (Revision 3.0) State University of New York at Stony Brook, Department of Psychology; Stony Brook, NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, Deane K. Defining and assessing individual differences in attachment relationships: Q-methodology and the organization of behavior in infancy and early childhood. Growing points of attachment theory and research. 1985. pp. 41–65.; Bretherton I, Waters E, editors. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. pp. 41–65. 50, (Serial No. 209) Serial No. 209.

- Wetherby AM, Prizant B. CSBS DP Manual: Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Development Profile. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc.; Baltimore: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman IL, Steiner VG, Pond RE. Preschool Language Scale, Fourth Edition (PLS-4) English Edition. Harcourt Assessment, Inc.; San Antonio, Texas: 2002. [Google Scholar]