Abstract

Asymmetric positioning of the mitotic spindle before cytokinesis can produce different-sized daughter cells that have distinct fates. Here, we found an asymmetric division in the Caenorhabditis elegans Q neuroblast lineage that began with a centered spindle but generated different-sized daughters, the smaller (anterior) of which underwent apoptosis. During this division, more myosin II accumulated anteriorly, suggesting that asymmetric contractile forces might produce different-sized daughters. Indeed, partial inactivation of anterior myosin by chromophore-assisted laser inactivation created a more symmetric division and allowed the survival and differentiation of the anterior daughter. Thus, the balance of myosin activity on the two sides of a dividing cell can govern the size and fate of the daughters.

Most somatic cell divisions equally partition the cytoplasm and produce equivalent daughters. Asymmetric cell divisions are used to generate distinct daughter cells that have different fates in development and in adult stem cell lineages (1, 2). Asymmetric cell division has been best studied in the first embryonic cell division in Caenorhabditis elegans (3). Here, unequal dynein-mediated pulling forces in the anterior-posterior axis displace the spindle toward the posterior pole (3–5). The cleavage furrow then forms in the middle of the elongating anaphase spindle, but because the spindle is displaced, the cell is divided into unequal-size daughters (3, 5). However, in Drosophila neuroblasts, asymmetric cell division begins with the spindle aligned in the middle of the cell (6–8). As anaphase progresses, the spindle elongates asymmetrically and the cytokinetic furrow shifts toward one side of the cell. However, the cellular mechanism responsible for this type of asymmetric cytokinesis is unknown.

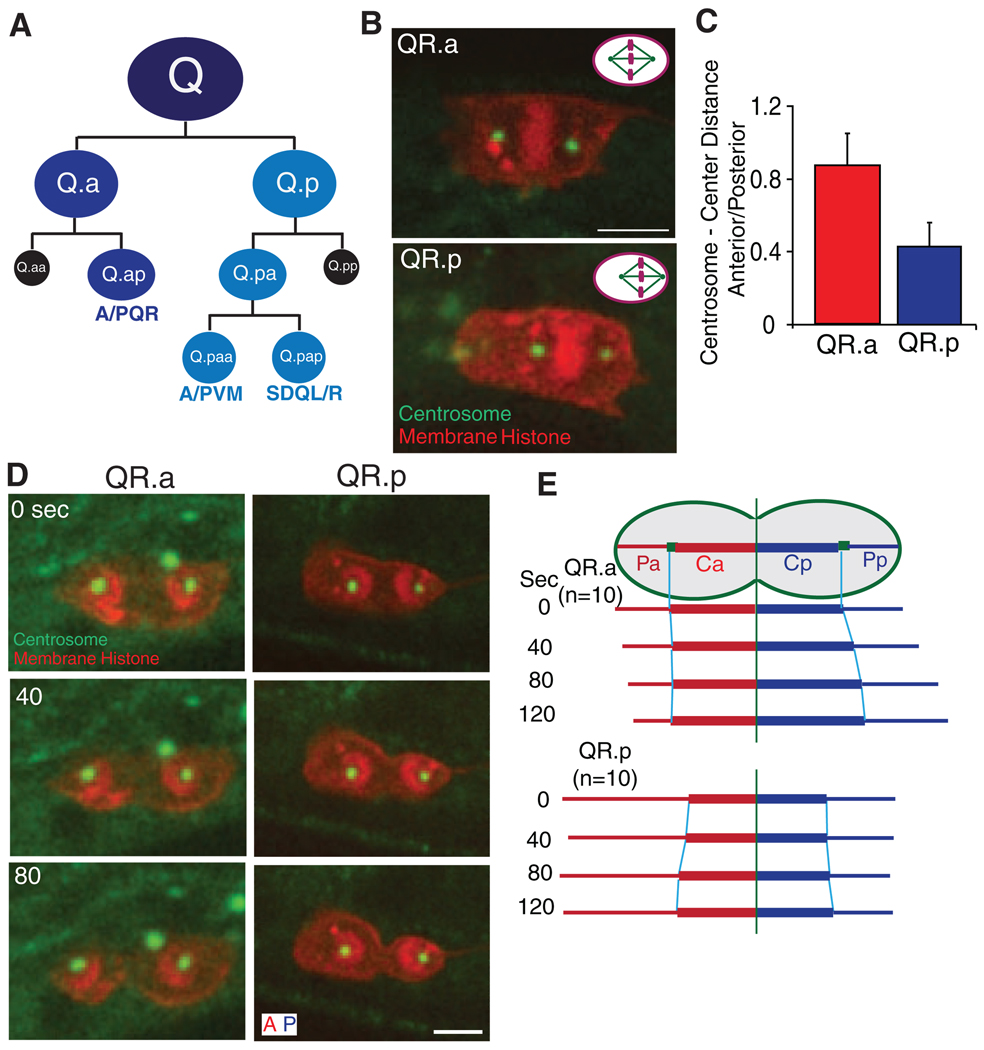

We developed fluorescence markers and live imaging methodologies to study asymmetric divisions in the C. elegans Q neuroblast lineage. Q neuroblasts undergo three rounds of division to make three distinct neurons and two apoptotic cells (Fig. 1A). In the second round, asymmetric divisions give rise to a large cell that continues to divide and differentiate and a small cell that undergoes apoptosis (Fig. 1A) (9).

Fig. 1.

C. elegans Q neuroblast lineage and spindle positioning in asymmetric cell division. (A) Three rounds of asymmetric cell divisions make three different neurons (QL generates PQR, PVM, and SDQL, whereas QR generates AQR, AVM and SDQR) and two apoptotic cells (in black). (B) Spindle positioning in the second-round division with centrosomes (γ-tubulin, TBG-1::GFP) in green and plasma membrane [mCherry with a myristoylation signal (12)] and histone (his-24::mCherry) in red. The cell anterior is toward the left. Bar, 2.5 µm. Upper right corners show a schematic summary of the results: QR.p spindle is displaced posteriorly but QR.a spindle is centered. (C) Centrosome–to–cell center distance ratio (anterior centrosome distance divided by posterior centrosome distance); data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 12). Cell center is defined as the midpoint between the two cell poles. (D) QR.a (left) and QR.p (right) spindles during anaphase and cytokinesis. (E) The distance of the centrosome to the cleavage furrow (Ca, anterior; Cp, posterior) or to the cell pole (Pa, Pp). The distance is quantified from 10 movies and is normalized compared to the initial distances for each centrosome at the start of anaphase. Raw data are shown in fig. S1.

We first examined the spindle positioning of the QR.p and QR.a cells at metaphase by measuring the distances from each centrosome [marked by γ-tubulin–green fluorescent protein (GFP)] to the center of the cell. In QR.p, the metaphase spindle was displaced toward the posterior; the distance from the anterior centrosome to the cell center was 0.4 times as long as that from the posterior centrosome to the cell center (Fig. 1, B and C, and movie S1). At anaphase, the cleavage furrow formed equidistant between the two centrosomes. As the spindle elongated, the distances of the anterior and posterior centrosomes to the furrow increased in a similar manner (Fig. 1, D and E, fig. S1, and movie S1); as the spindle was displaced before anaphase, a large and a small daughter cell were produced when the cytokinetic furrow bisected the spindle. The behavior of the QL.p division was similar to that of QR.p (fig. S2, A and B). Thus, this asymmetric division appears to be similar to the first cell division in C. elegans embryogenesis (3, 5).

The asymmetric division of the QR.a cell, however, was more similar to that described for Drosophila neuroblasts. In the QR.a cell, anaphase began with the two centrosomes positioned equidistant to the center [imaged with GFP–γ-tubulin (Fig. 1, B and C, and movie S2)] orGFP–α-tubulin (fig. S3 and movie S3). As anaphase progressed, the distance from the anterior centrosome to the ingressing cleavage furrow remained constant, whereas the posterior centrosome–to–furrow distance increased (Fig. 1, D and E, fig. S1, and movie S2). This progressively developing asymmetry that emerges in a cell with an initially centered spindle raises the possibility that a nonspindle factor may be driving the asymmetry in daughter cell size.

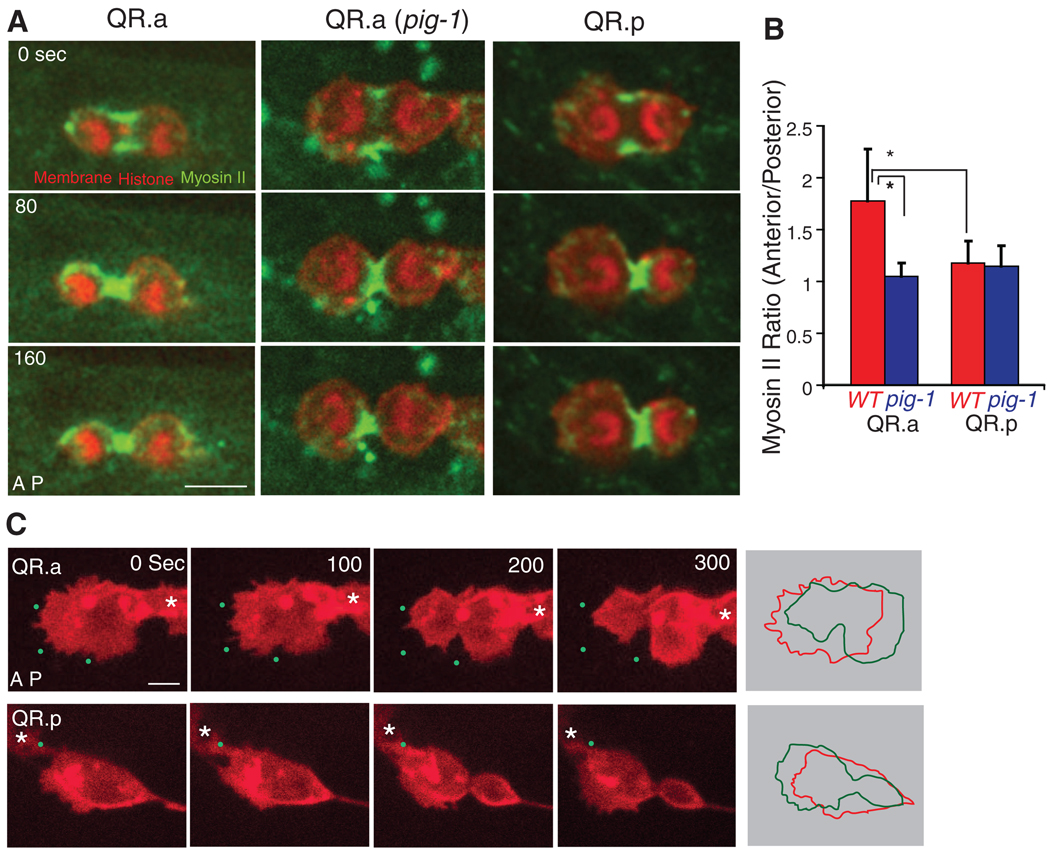

We next examined the dynamics of GFP-labeled nonmuscle myosin II in the contractile ring during cytokinesis. In the QR.p cell (posterior-displaced spindle), myosin II (NMY-2 in C. elegans) was equally distributed on the anterior and posterior sides of the ingressing furrow throughout cytokinesis (Fig. 2, A and B, fig. S4A, and movie S4). Myosin was depleted at both the anterior and posterior poles during telophase, as in somatic cell division (10). However, in the QR.a cell, where the cleavage furrow is initiated at the cell center, the distribution of myosin became asymmetric during anaphase. More cortical myosin was found at the anterior than at the posterior side of the furrow, particularly at early stages of anaphase, and cortical myosin was often found at the anterior pole of the QR.a cell, which was rarely seen in the QR.p cell (Fig. 2, A and B, movie S5, and fig. S4). We also observed a similar myosin II asymmetry during the asymmetric cell division in QL.a but not in the QL. p lineage (fig. S2, C and D).

Fig. 2.

Myosin II and membrane dynamics in Q neuroblasts during cytokinesis. (A) Still images of myosin II–GFP dynamics during cytokineses of QR.a in wild-type (WT) or QR.a in pig-1 mutant and QR.p animals. (B) Myosin II–GFP fluorescence intensities ratio between the anterior and posterior parts of QR.a or QR.p cells in WT or pig-1 (gm344) mutant (*P < 0.001, n = 9 to 11); data are shown as the mean ± SD. (C) Membrane dynamics of QR.a or QR.p during cytokinesis. The plasma membrane is imaged as in Fig. 1. Green dots are autofluorescent spots in the C. elegans body that provide fiducial marks (original image not shown). Panels on the far right show the alignment of QR.a and QR.p cell peripheries (0 s red, 300 s green) revealing the contraction and expansion of the two sides of the cell. Asters show neighboring Q cells. More examples are shown in fig. S6. Anterior of the cell is toward the left. Bar, 2.5 µm.

An asymmetric distribution of myosin in the QR.a cells might create a “tense” anterior cortex that resists deformation and a “relaxed” posterior cortex that can deform and expand. To explore this idea, we examined the shape of the plasma membrane (using an mCherry-tagged plasma membrane marker) in the anterior and posterior halves of the dividing cell. For the QR.p cell, its anterior pole is the leading edge of cell migration before and after cell division (QR.pa cell). The anterior membrane of the QR.p cell was more dynamic and more ruffled than the posterior portion from metaphase and throughout cytokinesis (Fig. 2C, movie S6, and fig. S6B). As the spindle elongated in anaphase, the centrosome–to–cell pole distances decreased equally in the anterior and posterior (Fig. 1, D and E, and movie S1), and the size of the anterior half was constantly ~2.2 times as large as that of the posterior throughout cytokinesis (fig. S5). However, a very different behavior was observed for the QR.a cell. Like that of the QR.p cell, the anterior half of the QR.a cell was the leading edge of migration before division, and was more dynamic and formed more protrusions than the posterior portion through metaphase (Fig. 2C, movie S7, and fig. S6A). However, unlike that of the QR.p cell, the anterior membrane became less dynamic and protrusive at anaphase and shrunk inward, resulting in a gradual decrease of the anterior pole–to–centrosome distance and also the size of the anterior daughter (Fig. 1, D and E, figs. S1 and S5, and movies S2 and S7). Furthermore, the membrane in the posterior pole expanded outward during anaphase, resulting in an increase in the posterior pole–to–centrosome distance and the overall size of the posterior daughter (Fig. 2C, figs. S1 and S5, and movie S7). Thus, higher levels of cortical tension and contractile forces may drive the membrane toward the centrosome in the anterior half and lower cortical tension may allow the expansion of the membrane away from the centrosome in the posterior half of the QR.a cell.

To further explore whether myosin II asymmetry is involved in generating the QR.a daughter cell size asymmetry, we examined GFP–myosin II in the pig-1 (gm344) mutant [PIG-1, a MELK-like kinase, is needed for asymmetric cell division in Q neuroblasts but not in the early embryo (11)]. In the pig-1 mutant, GFP–myosin II was distributed symmetrically on the anterior and posterior sides of the furrow during QR.a division (Fig. 2, A and B, fig. S4, and movie S8), consistent with a role for myosin in the asymmetric cell division of the QR.a cell. However, because the pig-1 mutant also affects the asymmetric division of the QR.p cell, which occurs by spindle displacement rather than asymmetric myosin, this correlation does not definitively link the polarization of myosin II with asymmetric cell division. To obtain more direct evidence, we inactivated myosin II activity using chromophore-assisted laser inactivation [CALI (12)] in the anterior of the QR.a cell at the onset of cytokinesis and determined whether this perturbation changed the sizes of the daughters. CALI uses an intense laser irradiation of a fluorophore, including GFP, to damage proteins within ~4 nm by generating highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (13–15). GFP-based CALI of the myosin II regulatory light chain has been shown to specifically block furrow ingression during cytokinesis in Drosophila epithelial cells (16). Similarly, in the first-round division of the QR cell, we found that CALI illumination of GFP–myosin II applied to one side of the furrow caused the ingression on that side to pause while the other, nonilluminated side continued to pinch (fig. S7B, 73%, n = 11). Thus, CALI can inhibit the myosin II activity during cytokinesis in the Q cell.

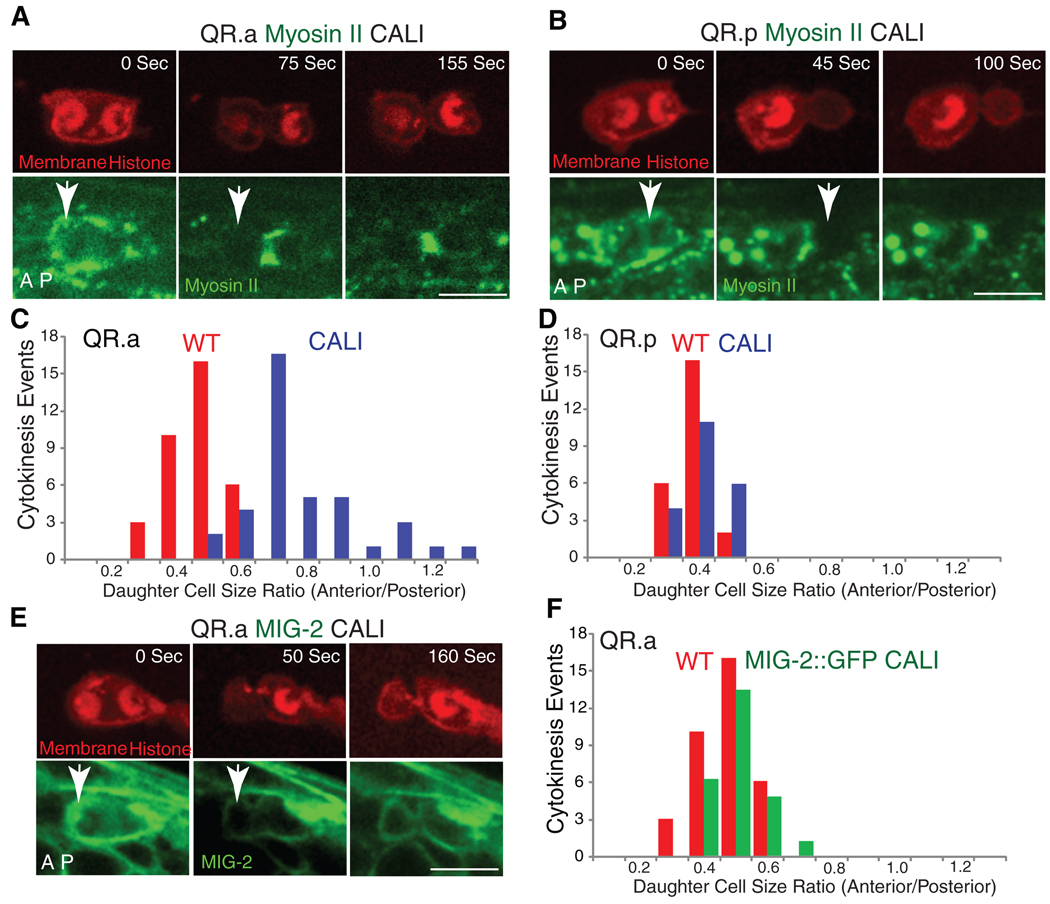

We next applied CALI to the anterior half of QR.a cell, which had higher GFP–myosin II, and then measured the sizes of the daughters. After CALI, the anterior daughter cell QR.aa was enlarged [QR.aa/QR.ap size ratio of 0.83 ± 0.18 (mean ± SD, n = 39) compared to normal (0.52 ± 0.08, n = 35) (Fig. 3, A and C)]. Furthermore, the QR.aa cell was sometimes larger than the QR.ap cell after CALI treatment, which was not observed in the wild type (Fig. 3C). To establish that these results were due to inactivation of myosin and not to nonspecific effects of illumination, we performed a similar CALI treatment of the GFP-tagged membrane protein MIG-2, a small guanosine triphosphatase involved in Q cell migration but not in cytokinesis (17, 18). Performing CALI of MIG-2::GFP in the anterior of the QR.a cell at anaphase did not significantly change the QR.aa/QR.ap cell size ratio (0.56 ± 0.07, n = 21) (Fig. 3, E and F). We also performed CALI of GFP-myosin II in the posterior half of the QR.p cell, whose asymmetric division appears to involve spindle displacement rather than asymmetric myosin (Figs. 1 and 2). In this case, CALI only marginally changed the QR.pp/QR.pa size ratio [(0.47 ± 0.06, n = 21) versus untreated (0.42 ± 0.06, n = 24); Fig. 3, B and D]. Thus, CALI of GFP-tagged myosin II specifically affects the daughter cell sizes of the QR.a division.

Fig. 3.

Chromophore-assisted laser inactivation (CALI) of myosin II in Q neuroblasts during cytokinesis. (A) CALI inactivation of myosin II in the anterior of QR.a enlarges the anterior daughter cell size. Upper images show the chromosome and plasma membrane labeled with mCherry, and lower images show GFP-tagged myosin II. Arrows indicate the region that was treated with CALI at late anaphase (12). (B) CALI inactivation of myosin II in the posterior of QR.p does not change sizes of daughter cells. (C) and (D) are quantifications of the above CALI experiments. (E and F) CALI of MIG-2::GFP does not change the ratio of QR.aa and QR.ap. Anterior of the cell is toward the left. Bar, 5 µm.

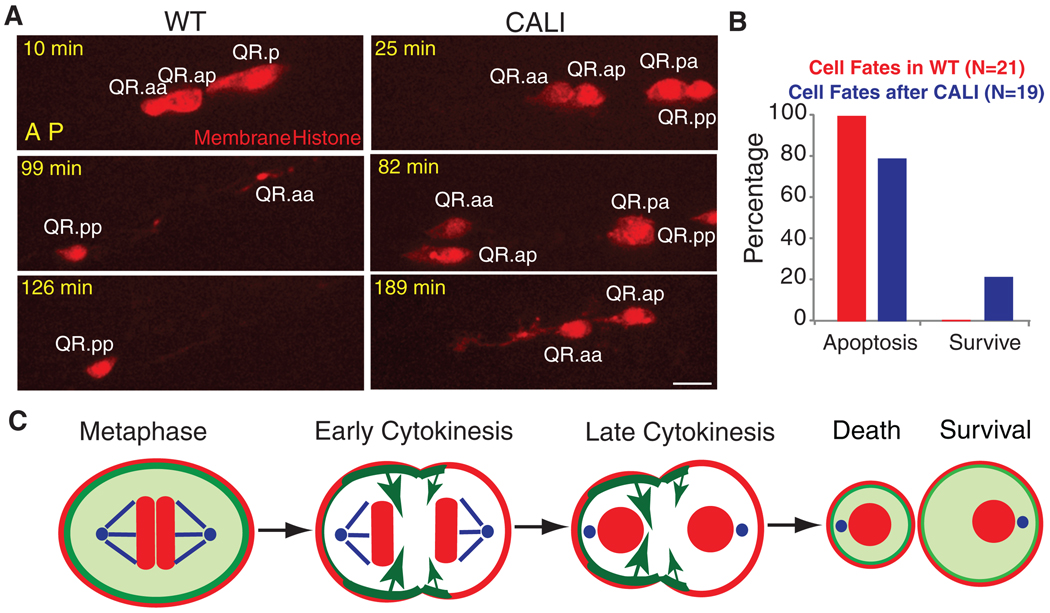

We next followed the fate of the QR.aa cell after CALI by long-term time lapse imaging. Normally, the QR.aa cell becomes engulfed and digested by neighboring cells within 150 min (Fig. 4, A and B, and movie S9) (9). In contrast, the QR.aa cell derived from the QR.a cell after CALI treatment sometimes escaped apoptosis (21%, n = 19) and could differentiate into a neuronal-like cell that extended a long process (11%) (Fig. 4, A and B, and movie S10). The larger QR.aa cells that formed after CALI were the ones that had a higher chance of survival (fig. S7C). The differentiation into a neuronal-like cell appears to be an outcome associated with survival rather than with CALI per se, because a similar differentiation phenotype was observed when QR.aa apoptosis was blocked in a ced-4 mutant (n1162) (fig. S8).

Fig. 4.

Cell fate after CALI and a proposed model. (A) QR.aa cells normally undergo apoptosis (disappearance at 126 min). After CALI, QR.a cell migrated (82 min, the nonmotile QR.pp provides a fiduciary marker) and formed a neurite-like process (189 min). (B) Quantifications of QR.aa cell fates (12) in WT (red) and after CALI (blue) ~150 min after birth. Anterior of the cell is toward the left. Bar, 5 µm. (C) Proposed mechanism of QR.aa asymmetric division. Myosin II localizes evenly in QR.a cell at metaphase but distributes asymmetrically during anaphase. More myosin II at the anterior than at the posterior may generate larger cortical tension (long arrows), pushing cellular contents and resulting in a small cell in the anterior that undergoes apoptosis and a large cell in the posterior that survives. Myosin II (green); plasma membrane and chromosomes (red); centrosome and microtubules (blue).

Our results show that asymmetric cortical tension, produced by an unequal distribution of myosin and perhaps other cortical proteins, produced two different-sized QR.a daughter cells. We propose that a stiffer and inward-contracting anterior pole pushes cytoplasm through the furrow toward the less contractile posterior pole, which responds by expanding like a balloon (Fig. 4C). We also demonstrate a direct connection between the size of a cell and its fate in C. elegans development by showing that increasing cell size by myosin II CALI can result in a rescue from apoptosis and differentiation into a neuronal-like cell.

The downstream “output” of asymmetric cortical signaling (3, 5) has been thought to be the mitotic spindle, best exemplified by the displacement of mitotic spindle in the C. elegans embryo (3, 5). Similarly, asymmetric divisions of Drosophila neuroblasts (which start anaphase with a symmetric, centrally positioned spindle) have been postulated to arise from the greater elongation of microtubules on one side of the spindle midzone compared with the other (6–8). We also observed asymmetric spindle elongation in the QR.a cell (Fig. 1, D and E), but propose that this occurs secondarily to myosin polarization, in which the spindle elongates preferentially toward the pole with lower cortical tension. In support of this idea, increasing cortical tension at the cell poles prevents spindle elongation and cell extension in dividing Drosophila S2 cells (19). Consequently, we propose that a polarization of myosin-based contractility is the primary driver of the QR.a cell division asymmetry, although we cannot rule out some contribution from the spindle as well. Thus, a simple organism like C. elegans [in which 807 out of its 949 somatic cell divisions are asymmetric (20)] appears to use at least two physical mechanisms (one spindle-based and one cortex-based) to generate asymmetric cell division.

Note added in proof: Cabernard et al. (21) recently showed an asymmetric distribution of myosin II during cytokinesis of Drosophila neuroblasts.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/science.1196112/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S8

Table S1

References

Movies S1 to S10

References and Notes

- 1.Moore KA, Lemischka IR. Science. 2006;311:1880. doi: 10.1126/science.1110542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumüller RA, Knoblich JA. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2675. doi: 10.1101/gad.1850809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider SQ, Bowerman B. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2003;37:221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.142443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gönczy P, Pichler S, Kirkham M, Hyman AA. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:135. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gönczy P. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:355. doi: 10.1038/nrm2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siller KH, Doe CQ. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:365. doi: 10.1038/ncb0409-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaltschmidt JA, Davidson CM, Brown NH, Brand AH. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:7. doi: 10.1038/71323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Y, Yu F, Lin S, Chia W, Yang X. Cell. 2003;112:51. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Dev. Biol. 1977;56:110. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vale RD, Spudich JA, Griffis ER. J. Cell Biol. 2009;186:727. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200902083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cordes S, Frank CA, Garriga G. Development. 2006;133:2747. doi: 10.1242/dev.02447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 13.Diefenbach TJ, et al. J. Cell Biol. 2002;158:1207. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobson K, Rajfur Z, Vitriol E, Hahn K. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:443. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang FS, Wolenski JS, Cheney RE, Mooseker MS, Jay DG. Science. 1996;273:660. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monier B, Pélissier-Monier A, Brand AH, Sanson B. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:60. doi: 10.1038/ncb2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ou G, Vale RD. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200812077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zipkin ID, Kindt RM, Kenyon CJ. Cell. 1997;90:883. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hickson GR, Echard A, O’Farrell PH. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:359. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horvitz HR, Herskowitz I. Cell. 1992;68:237. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90468-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabernard C, Prehoda KE, Doe CQ. Nature. 2010;467:91. doi: 10.1038/nature09334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.We thank L. Cai, D. Sherwood, J. Ziel, P. Zhang, I. Cheeseman, C. Kenyon, G. Garriga, and Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for reagents, equipments and strains, and thank C. Locke and W. Li for myosin quantifications. This work was supported by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (G.O.) and the NIH and Howard Hughes Medical Institute (R.D.V.).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.