A 6–12-month course of isoniazid (INH)* has been recommended as prophylaxis against tuberculosis for individuals having an asymptomatic positive tuberculin skin test (1, 2). Isoniazid is known to cause an elevation of liver enzymes (3-5), which usually improves after INH is discontinued. However, INH may sometimes cause fatal hepatic necrosis (6-9).

Liver transplantation has been reported to be effective for drug-induced hepatic failure of multiple etiologies (10-13). However, there have been no reports of liver transplantation for INH-induced hepatic failure. We describe here the case of a 16-year-old girl who developed hepatic failure following a 3-month course of INH use and was successfully treated with liver transplantation.

In September 1992, an otherwise healthy 16-year-old girl displayed a positive PPD skin test by routine examination, with a normal chest roentgenogram. She was placed on prophylactic doses of INH and pyridoxine. The INH was discontinued in late December, after she developed lethargy, weakness, and loss of appetite. In early January 1993, she was found to have scleral icterus, abnormal liver function tests, and coagulopathy (serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase 328 IUL, glutamic pyruvic transaminase 313 IUL, alkaline phosphatase 350 IUL, total bilirubin 10.4 mgldl, prothrombin time 20 sec, partial thromboplastin time 122 sec, ammonia 86 μmol/L). She was hospitalized and was started on lactulose, neomycin, cimetidine and vitamin K.

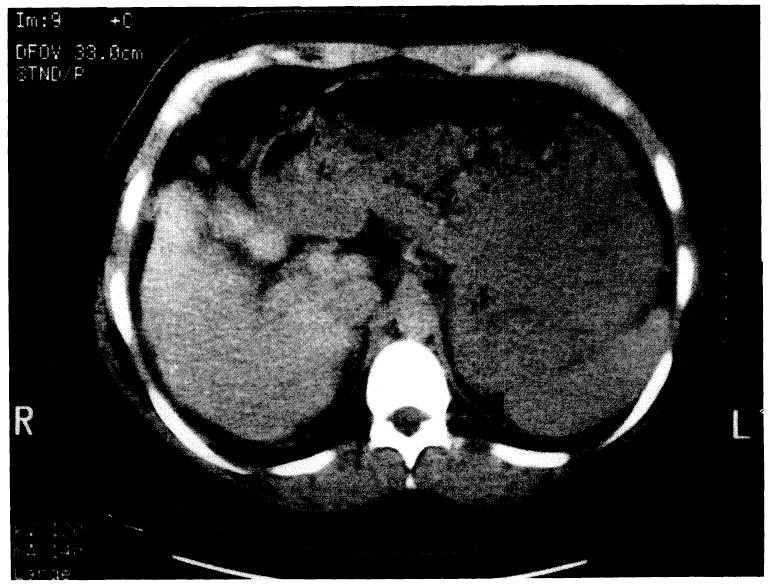

After 2 weeks, her total bilirubin decreased to 8.4 mg/dl, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase decreased to 203 IUL, and ammonia decreased to 60 μmol/dl; however, her prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time did not improve despite administration of fresh frozen plasma several times. She had not experienced episodes of bleeding or encephalopathy. She was transferred to our institution for possible liver transplantation. She had a firm liver without signs of portal hypertension. Computerized tomography scanning showed a diminished-size heterogeneous liver with calcified nodules (Fig. 1). There was no ascites or splenomegaly. Hepatitis A, B, C screens were negative. Serum alpha-1-antitrypsin, alpha-fetoprotein, copper, and ceruloplasmin levels were within normal ranges. Anti–smooth muscle, anti-DNA, anti-RNA, and antimicrosomal antibodies were negative. Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus titers were negative. A chest roentgenogram was normal. Cultures from the sputa were negative.

Figure 1.

Computerized tomography scan of the abdomen showing a diminished size heterogenous liver with calcified nodules.

In early February, she underwent orthotopic liver transplantation. Using the liver from a 10-year-old donor, the transplant was done with a transient portocaval shunt by the piggy-back method (14). An arterial graft was interposed between the infrarenal aorta and a small hepatic artery. The postoperative course was uneventful except for transient bleeding from a Roux-en-Y loop, which was treated with blood transfusion. Immunosuppression was with FK506 and steroids. Since her transplant, she has been on ethambutol and. pyrazinamide continuously as antituberculosis prophy-1axis. She had no episodes of rejection or infection and was discharged on the 13th postoperative day. She has had no respiratory symptoms and her chest roentgenogram has been normal during an 8-month follow-up.

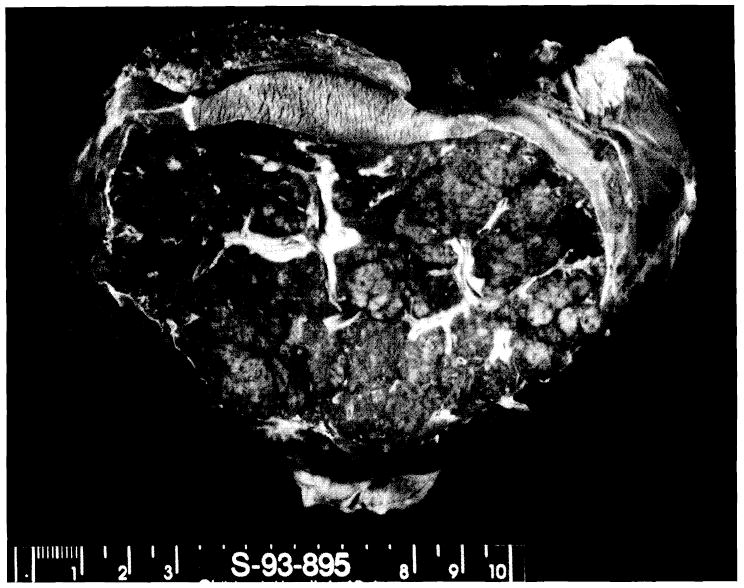

The resected liver was 484.5 g and 16×6×7 cm in size (Fig. 2). It was red-brown, rubbery, firm, and shrunken, with massive areas of necrosis intermixed with yellowish nodules of intact liver tissue. Histologically, the liver had extensive necrosis mixed with areas of remaining islands of hepatocytes. There was extensive acute and chronic inflammation. There were some regenerating hepatocytes and many proliferating cholangioles. No significant fibrosis was seen.

Figure 2.

The resected liver: weight: 484.5 g, size: 16×10×7 cm. The liver is rubbery, firm, and shrunken. There are massive areas of necrosis and small nodular areas of intact tissue.

Isoniazid hepatotoxicity is considered a hepatocellular hypersensitivity reaction that may cause diffuse hepatocellular necrosis (4). Initial elevation of transaminases occurs in 10–20% of patients undergoing INH therapy (15-17). Typically, this is remedied by discontinuation of INH. Although the mechanism of hepatic necrosis is unknown, once massive necrosis occurs the damage is irreversible and may be fatal. Mortality rates from hepatic failure are reported to be 23.2/100,000 or 57.9/100,000 (9, 18). In the present case, the resected liver showed massive necrosis, which was considered to be irreversible and fatal without liver transplantation.

Isoniazid hepatotoxicity resembles viral hepatitis and is diagnosed by ruling out other possible etiologies. In the present case, hepatitis screens and autoantibodies were negative. Alpha-1-antitrypsin, Alpha-fetoprotein, copper, and ceruloplasmin levels were within normal ranges. The patient developed hepatic failure 3 months after the initiation of INH therapy.

Liver transplantation has been successful for drug-induced hepatic failure secondary to ketoconazole, paracetamol, fipexide, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, sulfasulfalamin, halothane, and salazopyrine (9-12). Severe irreversible cases of INH-induced hepatic failure reported previously did not undergo liver transplantation, although one patient died while waiting for transplantation (5). The present case is the first reported case of INH-induced hepatic failure to undergo successful liver transplantation.

It is important to differentiate an irreversible case from a reversible one. Coagulopathy and hyperammonemia, as well as elevated liver enzymes and bilirubin, which are resistant to medical therapy, should reflect irreversible hepatic necrosis requiring liver transplantation. Additionally, a small cirrhotic liver seen by computerized tomography scanning may reveal significant postnecrotic changes. Once these abnormalities occur, acute hepatic failure develops, with immediate need for transplantation.

After transplantation, prophylactic antituberculosis medication, exclusive of INH, was required in our patient who had not completed her initial course of therapy. Sinnott et al. (19) have recommended pyrazinamide for prophylaxis in the transplanted patient receiving cyclosporine-related immunosuppressives. We chose to treat our patient with a six-month course of the combination of pyrazinamide and ethambutol. The use of two second-line antituberculosis medications was chosen to enhance the mycobactericidal activity in this immunosuppressed patient.

In conclusion, liver transplantation should be considered for severe irreversible INH-induced hepatic failure.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by research grants from the Veterans Administration and Project Grant DK-29961 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Abbreviation: INH, isoniazid.

References

- 1.Ferebee SH, Mount FW. Tuberculosis morbidity in a controlled trial of the prophylactic use of isoniazid among household contacts. Am Rev Resp Dis. 1962;85:490. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1962.85.4.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iseman MD, Miller B. If a tree falls in the middle of the forest: isoniazid and hepatitis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:575. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar A, Misra PK, Mehotra RAJ, Govil YC, Rana GS. Hepatotoxicity of rifampin and isoniazid. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:1350. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.6.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman C, Braman S. Isoniazid: a review with emphasis on adverse effects. Chest. 1972;62:71. doi: 10.1378/chest.62.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakajo MM, Rao M, Steiner P. Incidence of hepatotoxicity in children receiving isoniazid chemoprophylaxis. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1989;8:649. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198909000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spyridis P, Sinaniotis C, Papadia I, Oreopoulos L, Hadjiyiannis S, Papadatos C. Isoniazid liver injury during chemophylaxis in children. Arch Dis Child. 1979;54:65. doi: 10.1136/adc.54.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vanderhoof JA, Arment ME. Fatal hepatic necrosis due to isoniazid chemoprophylaxis in a 15-year-old girl. J Pediatr. 1976;88:867. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)81134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gal AA, Klatt EC. Fatal isoniazid hepatitis in a child. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1986;5:490. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198607000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snider DE, Cras GJ. Isoniazid-associated hepatitis deaths: a review of available information. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:494. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.2_Pt_1.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Grady JG, Wendon J, Tan KC, et al. Liver transplantation after paracetamol overdose. Br J Med. 1991;303:221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6796.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight TE, Shikuma CY, Knight J. Ketokonazole-induced fulminant hepatitis necessitating liver transplantation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:398. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70214-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durand F, Samuel D, Bernuau J, et al. Fipexide-induced fulminant hepatitis: report of three cases with emergency liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 1992;15:144. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90027-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isai H, Sheil AGR, McCaughan GW, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure and liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1992;24:1475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tzakis A, Todo S, Starzl TE. Orthotopic liver transplantation with preservation of the inferior vena cava. Ann Surg. 1989;210:649. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198911000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrd RB, Nelson R, Elliot RC. Isoniazid toxicity: a prospective study in secondary chemoprophylaxis. J Am Med Assoc. 1972;220:1471. doi: 10.1001/jama.220.11.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaudry PH, Brickman HF, Wise MB, MacDougall D. Liver enzyme disturbances during isoniazid chemoprophylaxis in children. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974;110:581. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1974.110.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell JR, Zimmerman HJ, Ishak JG, et al. Isoniazid liver injury: clinical spectrum, pathology and probable pathogenesis. Ann Int Med. 1976;84:181. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-84-2-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopanoff DE, Snider DE, Cara GJ. Isoniazid-related hepatitis: a US Public Health Service cooperative surveillance study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;117:991. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.117.6.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinnott JT, Emmanuel PJ. Mycobacterial infections in the transplant patient. Semin Resp Infect. 1990;5:65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]