Abstract

Brucellosis is a worldwide zoonotic infectious disease that has a significant economic impact on animal production and human public health. We characterized the gene expression profile of B. abortus-infected monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) from naïve cattle naturally resistant (R) or susceptible (S) to brucellosis using a cDNA microarray technology. Our data indicate that 1) B. abortus induced a slightly increased genome activation in R MDMs and a down-regulated transcriptome in S MDMs, during the onset of infection, 2) R MDMs had the ability to mount a type 1 immune response against B. abortus infection which was impaired in S cells, and 3) the host cell activity was not altered after 12h post-B. abortus infection in R MDMs while the cell cycle was largely arrested in infected S MDMs at 12h p.i. These results contribute to understand of how host responses may be manipulated to prevent infection by brucellae.

Keywords: Brucella, macrophages, cattle, resistance, microarray

1.4 Introduction

Infectious diseases are usually controlled by traditional interventions such as antibiotics or vaccines. However, these interventions are not completely effective, as diseases persist in animal populations. Repeated observations over time in domestic livestock have demonstrated that clinical manifestations of infectious disease rarely occur in all members of the population exposed to the same pathogen under similar conditions. Genetic implications of these observations were initially ignored until association of natural resistance to pathogens with genetic markers in animal species, breeds or families was established (Carmichael, 1941; Cameron et al., 1942; Bumstead and Barrow, 1993; Xu et al., 1993). The genetic regulation of natural resistance to infectious disease is variable and usually complex, and includes both immune and non-immune mechanisms, although sometimes expression of an allele at one locus can significantly modify the disease pathogenesis in individuals (Adams and Templeton, 1998).

Brucellae are the etiological agents of brucellosis, a worldwide zoonotic infectious disease that has a significant economic impact on animal production and human public health (Corbel, 1997). Among animal species, most mammals are susceptible to brucellosis. Bovine brucellosis is mainly caused by Brucella abortus which is clinically characterized by abortion and infertility in cows, and orchitis and inflammation of the accessory sex organs in bulls (Enright, 1990). Natural B. abortus infection in cattle occurs primarily through penetration of the mucosa membrane of the oropharynx followed by uptake by macrophages (MØ) and transport to the regional lymph nodes (Adams, 2002; Olsen et al., 2004). Successful initial establishment is due to the stealthy strategy employed by Brucella to modulate activation of the innate immune system, while persistent infection resides in the ability of the pathogen to modify trafficking to survive and replicate inside MØ by overcoming bactericidal mechanisms (Roop II et al., 2004; Barquero-Calvo et al., 2007).

The presence of invading microbes is detected by sentinel cells such as MØ and dendritic cells (DC). After contact with the pathogen, sentinel cells secret a mixture of cytokines and process and link the exogenous antigen to MHC-II molecules to activate T-helper (Th0) cells in secondary lymphoid organs. According to the stimulus received, Th0 cells differentiate into Th1 and Th2 subsets, which polarize the immune response (Salyers and Whitt, 2002). Th1 subset of cells develop in response of Th0 to IL-12, inducing a Th1-oriented immune response, mostly involved in protection against intracellular pathogens through cell-mediated immunity and characterized preferentially by secretion of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin 2 (IL-2) cytokines. On the other hand, sentinel cells that secrete IL-4 induce a Th2 subset of cells development and a Th2-oriented immune response. Th2 immunity is characterized by secretion of IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13 and is mainly responsible for protection against extracellular pathogens by mediating antibody production (Tizard, 2004).

Previous studies have reported that Th1 immune response is particularly involved in host protection against Brucella infection through cell-mediated immunity (Oliveira et al., 2002). When Brucella invade naïve hosts non-activated professional phagocytes uptake the pathogen and release interleukin-12 (IL-12). Subsequently, IL-12 induce Th0 cells to differentiate into IFNγ-secreting Th1 cells that are capable of activating MØ for increased anti-microbial mechanisms, and thus promote clearance of the bacteria (Zaitseva et al., 1995; Dornand et al., 2002). However, virulent Brucella have developed active strategies to interfere with innate immunity and consequently avoid being eliminated. For instance, Brucella impair apoptosis in human MØ (Gross et al., 2000; Fernandez Prada et al., 2003) and inhibit or delay dendritic cells maturation and antigen presentation (Billard et al., 2008). Moreover, Brucella alter the production and secretion of cytokines of infected host cells (Caron et al., 1994), modify the intracellular trafficking (Rittig et al., 2003), inhibit degranulation of neutrophils (Bertram et al., 1986; Orduna et al., 1991), and impair NK cell activity (Salmeron et al., 1992).

Previously, our laboratory identified cattle naturally resistant (R) and susceptible (S) to B. abortus infection (Harmon et al., 1985; Templeton et al., 1988). In these studies, the R cattle developed low transient serologic titers and were negative for Brucella isolation, while S infected cows developed high titers, aborted and Brucella was isolated from secretions. Later experiments focused on innate immunity found that mammary gland MØ from R cows produced significantly higher oxidative burst activity and had significantly greater in vitro bacteriostatic activity than MØ from S cows, when both were stimulated with opsonized B. abortus (Harmon et al., 1989). Furthermore, B. abortus were demonstrated to bind differentially to the peripheral blood monocyte-derived MØ (MDMs) from R or S cattle and also the cells from R animals were significantly superior in their ability to control the in vitro intracellular replication of B. abortus than those derived from S cattle (Price et al, 1990; Campbell and Adams, 1992; Campbell et al., 1994; Qureshi et al., 1996). These findings further substantiate the importance of the mononuclear phagocyte system in natural resistance to bovine brucellosis. In order to associate natural resistance with genetic markers, later studies identified the bovine SLC11A1 gene (formerly NRAMP1) as one of the major elements in controlling of intracellular replication of B. abortus in MØ (Feng et al., 1996; Adams and Templeton, 1998; Barthel et al., 2001). To better understand the differences in the phenotype and identifying novel cattle candidate genes and pathways involved in innate resistance to brucellosis, we characterized the expression profile of B. abortus-infected MDMs from naïve cattle naturally R or S to brucellosis using a cDNA microarray technology. In concordance with previous knowledge, our results demonstrated that R MDMs were superior controlling B. abortus infection due to the ability to polarize an immune response toward Th1, while the innate immune system of S MDMs failed to generate appropriate signals to mount an effective immune response against invading bacteria.

1.5 Materials and Methods

Bacterial strain, media and culture conditions

The smooth virulent Brucella abortus S2308 (gift of Dr. Billy Devoe, USDA, Agricultural Research Service, National Animal Disease Center, Ames, IA) was maintained as frozen glycerol stocks and resuspended in fresh complete RPMI (C-RPMI) 1640 medium (RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 4mM L-glutamine, 1mM non-essential amino acids, 1mM sodium pyruvate and 2.9mM 7.5% sodium bicarbonate) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS) (American Type Culture Collection – ATCC, Manassas, VA) at 1 × 107 CFU/ml and incubated at 38°C for 1 h prior to use in assays. The CFU inoculated was corroborated retrospectively by serial dilution plating the inoculum on TSA plate.

Isolation of peripheral blood monocytes

Blood was collected from a clone of a bull naturally R to B. abortus S2308 infection (Westhusin et al., 2007) and a progeny from the pedigreed family of cattle previously characterized as S to conjunctival challenge with live B. abortus (Price et al., 1990). The cattle were unvaccinated and serologically negative to brucellosis by the card test and complement serological assays. Blood was extracted and processed as previously explained (Campbell and Adams, 1992). Briefly, 50 ml of blood was collected by aseptic venipuncture of the jugular vein into 7.5 ml of acid-citrate-dextrose (ACD) and diluted in an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline containing citrate (PBS-C). Diluted blood was carefully poured on the top of Percoll (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and centrifuged at 1000X g for 30 min. The interface cells were washed 3 times in cold PBS-C, resuspended in C-RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 4% of autologous serum and transferred to Teflon Erlenmeyer flasks. After 38°C incubation overnight in humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2, non-adherent cells were removed and fresh media added to each flask before replacing them in the incubator. The cells were kept in culture for 21 days with medium changes every 7 days to let monocytes mature to MØ before using them in assays.

Infection assay

Twenty-four hours prior to infection, MDMs were harvested by chilling the Teflon flasks on ice for 15 min, enumerated and subcultured in 25cm2 cell culture flasks (Corning, Corning, NY) at a concentration of 2 × 105 MDMs/flask and replaced to the incubator. Infection with B. abortus S2308 was performed at the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5:1 (bacteria: MDMs) by centrifuging bacteria onto cells at 800X g for 10 min. After 30 min incubation to allow bacteria: MDMs interaction, extracellular bacteria were killed by replacing the culture media on each flask by C-RPMI medium supplemented with 50µg/ml of gentamicin solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). After 1 hour incubation, all flasks were washed 3 times with PBS to eliminate antibiotic residue and 8 ml of fresh C-RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% HI-FBS was added to every culture before replacing them to the incubator. Sham inoculated MDMs were used as controls. To determine the number of intracellularly viable B. abortus S2308 at T0 and T12, MDMs were plated in triplicate in 24 well plates at 2 × 105 MDMs/well and infected at MOI 5:1. At T0 (i.e., immediately after cells were washed to eliminate antibiotic residue) and T12 (i.e., 12 h post infection, -p.i.-), infected cells were lysed with 0.5% Tween-20 (Sigma) in sterile distilled water, lysates, serially diluted and 100µl of dilutions cultured on TSA plates for quantification of CFU. Triplicate wells containing bacterial suspensions alone were plated in each well and used as a control for the adequacy of killing of extracellular bacteria and for the control of bacterial growth.

Isolation of total RNA from MDMs

Total RNA from infected and control MDMs from cattle R or S to B. abortus infection was isolated at 12 h p.i. At this time point, supernatants from the cultures were harvested and the cells were rinsed once with cold PBS. One ml of Tri-reagent® (Ambion, Austin, TX) was added to each flask and RNA extracted using the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. The resultant RNA pellets were re-suspended in DEPC-treated water (Ambion) with 1% RNAse inhibitor (Promega, Madison, WI). Genomic DNA was removed by RNase free - DNAse I treatment (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and samples were stored at −80°C until used. RNA concentration was quantified by measuring absorbance at λ260nm using a NanoDrop® ND-1000 (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE), and the quality of the RNA determined using a Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA).

Preparation of bovine reference RNA

Based on previous references that demonstrated no statistical difference between genomic DNA and reference RNA for standardizing spotted microarray data (Weil et al., 2002), we prepared bovine RNA common reference set for standardizing our array experiments (Pollack, 2002). Total RNA was isolated from Madin-Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) and bovine B lymphocyte (BL-3) cell lines (ATCC) and fresh bovine brain, as explained above. Cell lines were grown in 150 cm2 cell culture flasks with minimum essential medium Eagle (MEME) (ATCC) supplemented with 10% HI-FBS. Bovine brain was harvested from cortex and cerebellum of a Holstein male calf immediately after euthanasia. The tissue was homogenized in ice-cold Tri-reagent® (Ambion). RNA concentration from each sample was quantified and bioanalyzed before and after pooling the samples. Total RNA isolated from three samples was pooled together in equal amounts, aliquoted and stored at −80°C until needed.

Construction of 13K bovine cDNA microarrays and annotation

A custom bovine cDNA library consisting of unique 70-mer oligonucleotides representing 13,257 unique oligos of 12,220 cattle ORFs obtained from normalized and subtracted cattle cDNA libraries was printed in 150 mM phosphate buffer at 20 µM concentration in duplicate on aminosilane-coated glass slides at the W. M. Keck Center (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). The oligos were annotated based on the GenBank accession number, when available. Additional description of the array design, construction and annotation has been previously published (Everts et al., 2005; Loor et al., 2007). Sequence annotation of the differentially expressed spots was manually improved by blast searches on public databases (GenBank, UniGene).

Sample preparation and slide hybridization

Three biological replicates of B. abortus-infected and non-infected MDMs from cattle naturally R or S to brucellosis at 12 h p.i. (n = 12) were analyzed. The labeling and hybridization procedures were adapted from the protocol described previously (Rossetti et al., 2009). Briefly, 10µg of experimental and reference total RNA were reverse transcribed overnight to amino-allyl cDNA using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cy3 and Cy5 dye esters (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) were covalently linked to the amino-allyl group by incubating the samples with the dye esters in 0.1M sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9,0). After one hour incubation in the dark, uncoupled dyes were removed and dye incorporation calculated based on NanoDrop® analysis. Dry, labeled experimental cDNA samples were resuspended in 20µl of nuclease – free water (Ambion) and reference samples in 20µl of bovine competitor DNA (Applied Genetics Laboratories, Melbourne, FL) and combined. Mixed samples were heated at 95°C for 5 min, annealed at 60°C for 10 min and kept at room temperature for another 10 min. Samples were kept at 42°C until hybridization. Forty µl of 2X formamide-based hybridization buffer [50% formamide; 10X SSC; 0.2% SDS] was added to pre-annealed samples, mixed well and applied to the 13.2K bovine oligo-slides. Prior to hybridization, the microarrays were denatured by exposing to steam from boiling water, UV cross-linked and immersed in prehybridization buffer [5X sodium chloride, sodium citrate buffer (SSC), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Ambion); 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)] at 42°C for a minimum of 45 min followed by four washes in RNase-DNase free, distilled water, immersion in 100% isopropanol for 10 seconds, and dried by centrifugation. Slides were hybridized at 42°C for approximately 40 h in a dark humid hybridization chamber (Corning) and washed for 10 min at 42°C with low stringency buffer [1X SSC, 0.2% SDS] followed by two 5-min washes in a higher stringency buffers [0.1X SSC, 0.2% SDS and 0.1X SSC] at room temperature with agitation. Slides were drying by centrifugation at 800X g for 2 min and immediately scanned.

Data acquisition and microarray data analysis

Hybridized slides were scanned by a commercial laser scanner (GenePix 4100; Axon Instruments, Inc., Foster City, CA). Scans were performed using the autoscan feature with the percent saturated pixels set at 0.03%. The spots representing genes on the arrays were adjusted for background and normalized to internal controls using image analysis software (GenePix Pro 6.0; Axon Instruments, Inc.). Spots with fluorescent signal values below background were disregarded in all analyses. Initially, arrays were normalized against bovine reference RNA signals across slides and within each slide (across the duplicate spots). Data were analyzed using GeneSifter (VizX Labs, Seattle, WA) and using a combinatorial statistical approach as follows: data were normalized by mean and then combined, Student’s t test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction was performed with a cutoff value of 0.05, and pairwise comparisons were made with a fold-change cutoff of 2-fold. Genes were considered as significantly altered if the average fold-change was at least 2, the adjusted p value was less than 0.05 and the alteration was reproducible across replicates. Microarray data are deposited in GEO database at NCBI (Accession # GSE16112).

Microarray results validation

Ten selected genes with differential expression by microarray results (i.e., 5 differentially expressed genes in S MDMs and 5 in R MDMs at 12 h p.i. compared to uninfected cells) were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Two micrograms of RNA were reverse transcribed using TaqMan® Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). For relative quantitation of target cDNA, samples were run in individual tubes in SmartCycler II (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA). One SmartMix bead (Cepheid) was used for 2 – 25 µl PCR reactions along with 20ng of cDNA, 0.2X SYBR Green I dye (Invitrogen) and 0.3µM forward and reverse primers (Sigma Genosys) designed by Primer Express Software v2.0 (Applied Biosystems) (Table 1). For each gene tested, the individual calculated threshold cycles (Ct) were averaged among each condition and normalized to the Ct of the GAPDH from the same cDNA samples before calculating the fold change using the ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). For each primer pair, a negative control (water) and an RNA sample without reverse transcriptase (to determine genomic DNA contamination) were included as controls during cDNA quantitation. Array data were considered valid if the fold-change of each gene tested by qRT-PCR was >2.0 and in the same direction as determined by microarray analysis.

Table 1.

Primers for Real Time – PCR evaluated genes of bovine monocyte- derived macrophages.

| GeneBank accession # |

Gene symbol |

Gene name | Forward primers (5'-3') | Reverse primers (5'-3') |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_174006 | CCL2 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | TCCTAAAGAGGCTGTGATTTTCAA | AGGGAAAGCCGGAAGAACAC |

| NM_174092 | IL-1A | Interleukin 1, α | GCCACAAAGCAAGAAAAATTGG | ACATGCTCAGCGAGTGACTAACA |

| NM_174187 | SPP1 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | TGCCACAGAGGAGGACTTCAC | CTTGTTCTTATCCTTGGCCTTTG |

| NM_001035306 | RPL5 | Ribosomal protein L5 | GCCAGAACTACTACCGGGAATAAA | CCATGATGTGCTTTCGGTGTA |

| NM_001098933 | CCRK | Cell cycle related kinase | GCTGTCAGCTTCCAATTTTGTG | CCCTGCCTGGTGGAATCC |

| NM_001037100 | BCL2A1 | BCL2 related protein A1 | GCCAGAACAATATTCAACCAAGTG | TGATGAACTCCGCCACAAAG |

| NM_001075147 | CCL4 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 | AGCTGTGGTATTCCAGACCAAAA | GCATGGAGAGGGTGCATCTC |

| NM_001080272 | OSMR | Oncostatin M receptor | GTTGTTCACGCCACGCTTCT | GGAGGTAAGCTCCTTGGCATT |

| NM_001098135 | RPS27 | Ribosomal protein S27 | TGCAGAGCCCCAATTCCTAT | GCCAACACACAAGACTACTGTTTGT |

| NM_001076831 | COL3A1 | Collagen, type III, alpha 1 | CACTCCATATGTTCCTTTTGTTCTAATC | CACTCCATATGTTCCTTTTGTTCTAATC |

| NM_001034034 | GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | TTCTGGCAAAGTGGACATCG | GCCTTGACTGTGCCGTTGA |

2 Results

Invasion and intracellular growth of B. abortus S2308 revealed different patterns in MDMs from R and S cattle

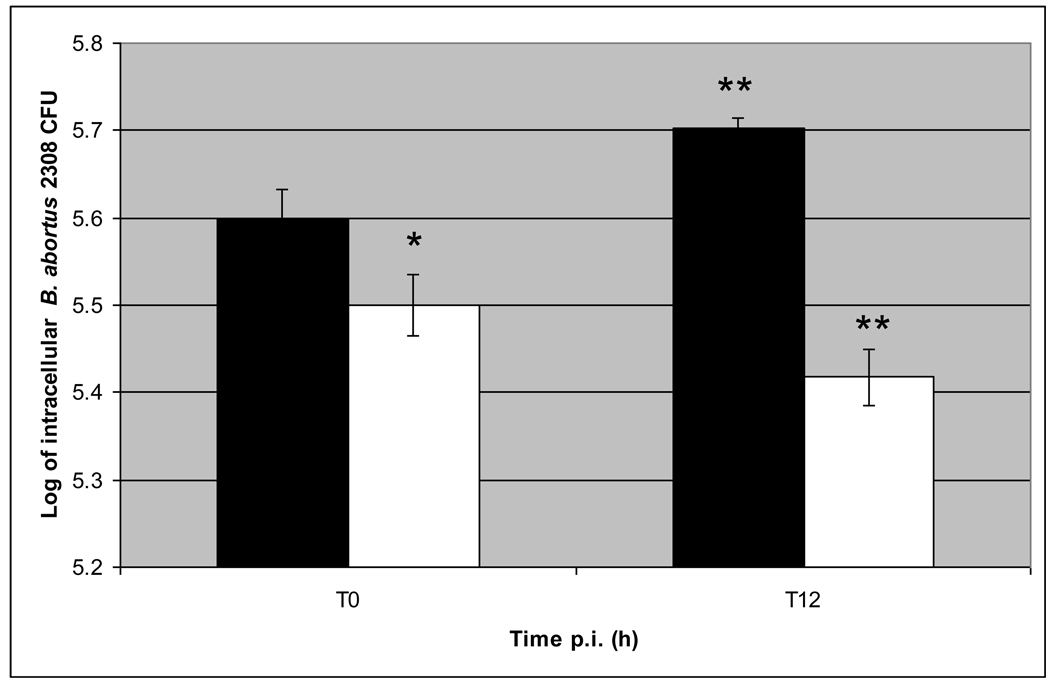

At T0, the CFU of Brucella recovered from wells with R MDMs was significantly lower (P < 0.05) than those from wells with S MDMs. At 12 h p.i. (T12), the number of intracellular B. abortus was 18% lower in MDMs from R animal, and 27% higher in MDMs from S animal, compared to their own T0 value (in both cases P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). The number of B. abortus S2308 CFU present in growth control wells increased more than 1 log in the first 12 h p.i. compared with the original inoculum and the number of bacteria present in growth control wells after antibiotic treatment was reduced to zero. Altogether, these results indicate that B. abortus attach and internalize less efficiently in R than S MDMs and furthermore R MDMs kill more efficiently and inhibit B. abortus intracellular replication in the first 12 h p.i than S MDMs.

Figure 1. Kinetics of B. abortus S2308 intracellular growth in bovine monocytes-derived macrophages from cattle naturally resistant (R) or susceptible (S) to brucellosis.

Monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) were plated in triplicate in 24 well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well and infected with B. abortus S2308 at a MOI 5:1. After 30 min – interaction, extracellular bacteria were killed by co-incubation with gentamycin for 1 h, and then washed 3 times with PBS. At 0 (T0) and 12 (T12) h post-infection, cells were lysed and serial dilutions cultured on TSA plates for quantification of CFU. The intracellular number of B. abortus S2308 was significantly different (P < 0.05) in MDMs from R and S cattle at T0 (*) and at T12 from R or S MDMs compared to their own T0 value (**). Means +/− SD (bars) of 3 independent assays done in triplicate are shown. Solid bars indicate intracellular B. abortus CFU from S MDMs, open bars indicate intracellular B. abortus CFU from R MDMs.

Reliability of array data

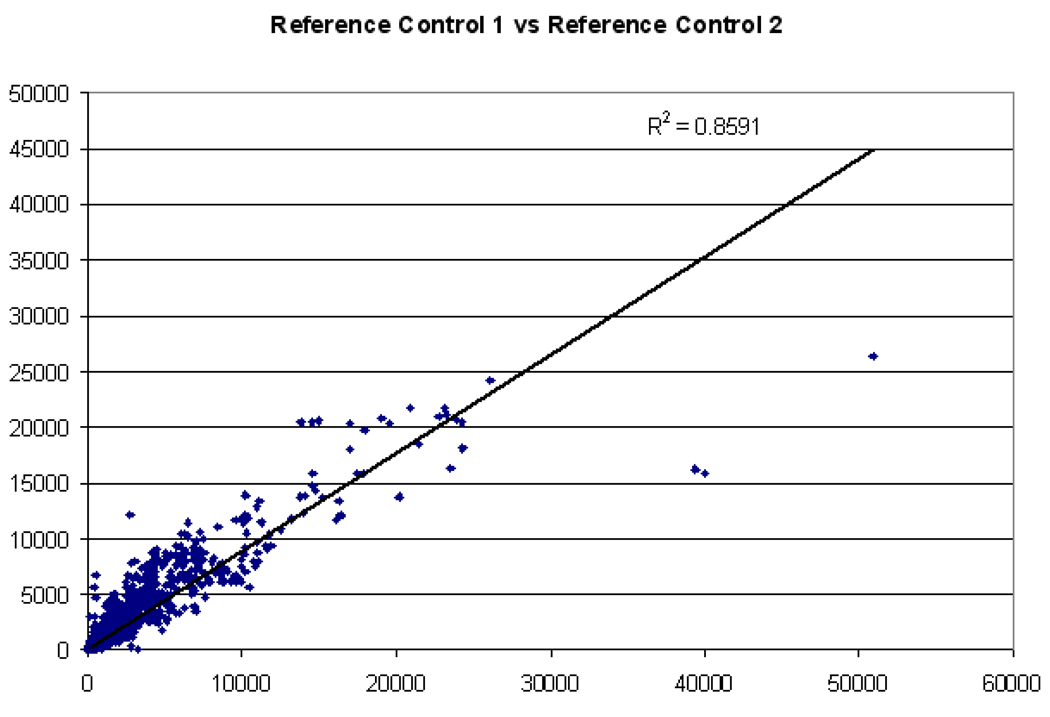

Twelve RNA experimental samples representing 4 different scenarios (triplicate biological replicas of infected and uninfected MDMs from R and S animals at 12 h post-treatment) were manually co-hybridized against a common bovine reference RNA on custom two-color DNA microarrays, each representing ~13,000 bovine ESTs, spotted in duplicate. The RNA analyzed from all samples was of good to excellent quality (RIN ≥ 9.0, 28S/18S ratio ≥ 1.6, OD260/280 ≥ 2.0, OD260/230 > 1.8 for experimental samples; and RIN = 9.7, 28S/18S ratio = 2.1, OD260/280 = 2.01, OD260/230 = 1.85 for reference RNA). The reference RNA generated readable signal intensities for more than 85% of the genes on the microarray (SNR > 3SD above background), and co-hybridization with experimental samples provided comparisons of MDMs gene expression profiles across all treatments and time points. For each of these samples, the spots represented on the arrays were adjusted for background and normalized to internal controls using GenePix Pro 6.0 software. Linear regression analysis of reference signal values (before normalization) from each array yielded an average R-squared value of 0.784 (minimum of 0.632 and maximum of 0.874), indicating that labeling procedures were consistent across all arrays. A comparison of like-experimental samples (e.g., control replicate 1 versus control replicate 2) yielded similarly consistent results (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Expression profile chart for genes from bovine reference RNA samples.

An expression profile chart of two identical reference samples with linear trend line and R-squared values is shown. The ordinate represents non-normalized signal intensity values for each spot (gene) from one randomly chosen reference sample, and a second reference sample is indicated on the abscissa.

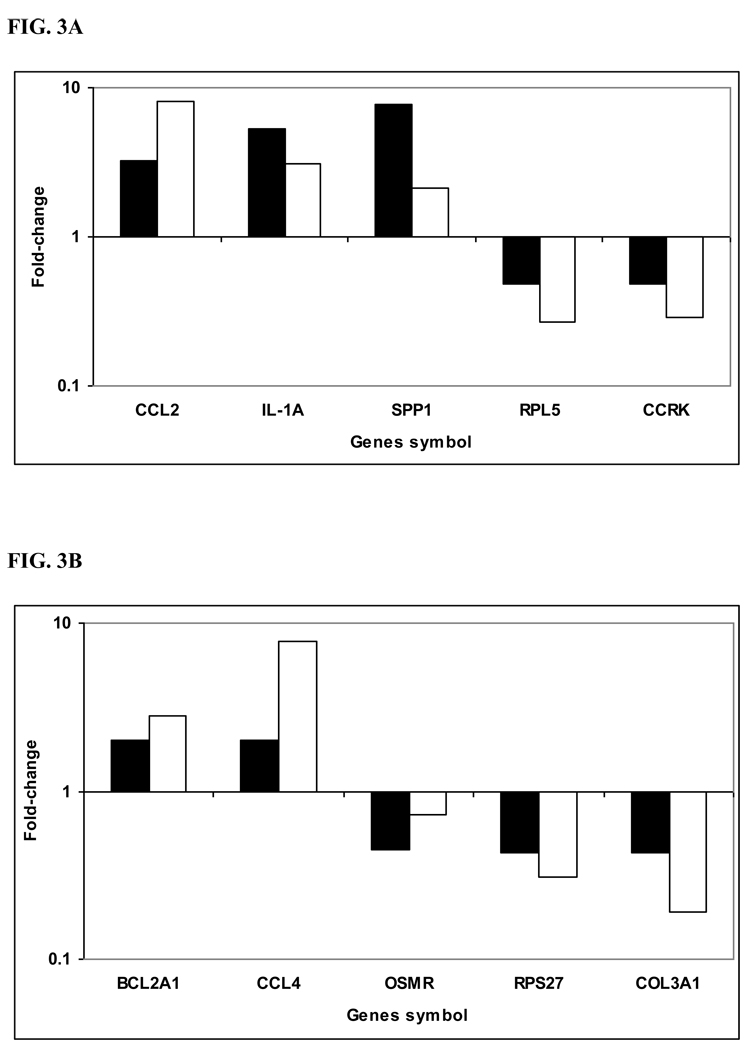

To confirm the microarray results, we randomly selected 10 differentially expressed genes at 12 h p.i. (five from each condition, i.e. R and S) and performed qRT-PCR. Based on qRT-PCR results, transcript levels of 9 of 10 genes were altered greater than 2.0-fold and in the same direction as was determined by microarray analysis. The other gene (OSMR) was determined to be differentially expressed and in the same direction of microarray analysis, but the fold change was lower than 2 (Fig. 3A and B).

Figure 3. Validation of microarray results by quantitative Real Time - PCR.

cDNA was synthesized from the same RNA samples used for microarray hybridization. Ten selected genes that were differentially expressed based on microarray analysis between B. abortus-infected susceptible bovine MDMs (A) and B. abortus-infected resistant bovine MDMs (B) at 12h p.i. as compared with non-infected cells (control), were validated by quantitative RT-PCR. Fold-change was normalized to the expression of GAPDH and calculated using the ΔΔCt method. All the genes tested had fold-changes in the same direction by both methodologies and 9 of 10 were also altered greater than 2-fold. Solid bars indicate microarray fold-change, open bars indicate qRT-PCR fold-change.

Uninfected R and S MDMs displayed different transcriptional profiles

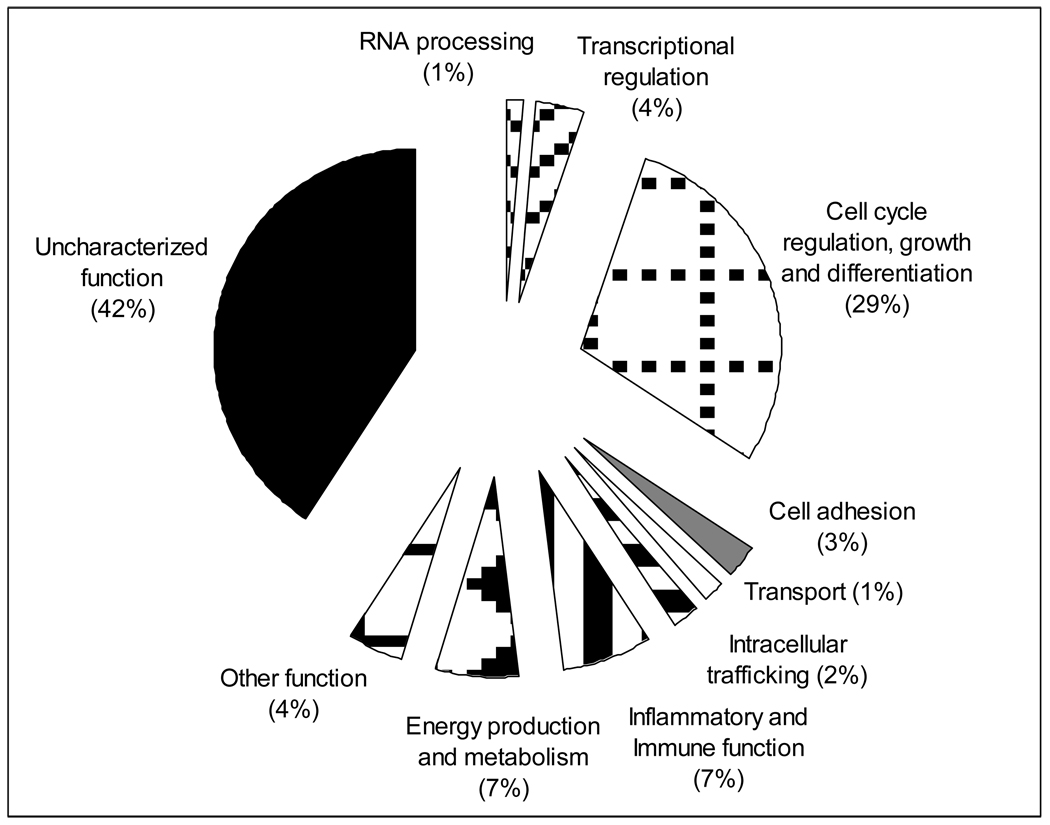

In order to identify candidate molecular markers or pathways relevant for B. abortus innate resistance, we compared the transcriptomes of uninfected S and R MDMs to identify infection-independent differences between the cells. Microarray data analysis revealed that 135 genes (80 with known function and 55 without functional characterization) were significantly altered (at least 2-fold and P value less than 0.05) between uninfected R and S MDMs under the same condition (Table 2). More specifically our data indicate that 123 (90%) of the differentially expressed genes were down-regulated and only 12 genes were up-regulated in R MDM cells versus S MDM cells. Differentially expressed genes with known or inferred function (80 genes) were grouped in terms of the associated biological processes attributed to each of their products (http://www.amigo.geneontology.org). The pie graph in Fig. 4 provides an overview of the groups sorted by biological processes of differentially expressed genes by uninfected R and S MDMs. Down-regulation expression of immune-related genes such as IL-18bp, C1RL, FCAR, ALOX5AP, PF4 and CCL2 may enhance Th1 immune response and reduce humoral and inflammatory reaction. Simultaneously, the reduction of cell proliferation activity is reflected by the down regulation of the 39 of 41 of the genes differentially expressed related with cell growth, differentiation and proliferation. The most highly and the lowest expressed genes in R MDMs compared to S were 2 loci without functional characterization (19.5 and −47 fold). Summarizing, the general functional trend suggests that the MDMs-resistant phenotype presents a basal enhanced Th1 immune response and a reduced expression of humoral and inflammatory factors and cell proliferation activity as well, compared to gene expression profiles of S MDMs.

Table 2.

Comparison of genes differentially expressed in uninfected monocyte-derived macrophages from cattle resistant to susceptible to brucellosis.

| Sequence Identifier |

Gene symbol | Fold-change |

|---|---|---|

| RNA processing | ||

| CR452407 | PSRC2 | −2.6 |

| NM_174594 | RNASE6 | −5.9 |

| Transcription regulation | ||

| CN437874 | LBH | 2 |

| CN442084 | SFMBT2 | −2 |

| CN437084 | NR2F1 | −3.1 |

| BF041696 | PMF1 | −3.2 |

| CN436867 | TRIP13 | −3.5 |

| Cell cycle regulation/growth/differentiation | ||

| CR452577 | Transcribed locus | 3 |

| NM_174264 | CCNB2 | −2 |

| CR454106 | CABLES1 | −2.1 |

| CR453022 | MCM2 | −2.1 |

| BM364143 | ARL6IP1 | −2.3 |

| CN437507 | TCFL5 | −2.5 |

| CN434361 | TYMS | −2.6 |

| CR455944 | CCNA2 | −2.7 |

| CN436077 | FANCD2 | −2.8 |

| CR454614 | HELLS | −2.9 |

| AW357584 | CDC6 | −3 |

| CR452898 | SPBC25 | −3.2 |

| BM364726 | RBL2 | −3.2 |

| CN438866 | ALX1 | −3.3 |

| CR550984 | SMC2 | −3.3 |

| BF040210 | DAB2 | −3.3 |

| CR453527 | RRM2 | −3.4 |

| CN440981 | CEP72 | −3.4 |

| CN437405 | DZIP1 | −3.7 |

| BF045590 | RYBP | −3.7 |

| CN433387 | CDCA3 | −4 |

| CR456279 | CENPF | −4.2 |

| CN441415 | SPAG5 | −4.3 |

| CK773173 | CDC45L | −4.5 |

| BP100977 | ASF1B | −4.9 |

| CN433213 | CKAP2 | −5 |

| CN433471 | TPX2 | −5.1 |

| CN432347 | CTTNBP2 | −5.1 |

| CN440096 | STMN1 | −5.2 |

| DR749363 | CCNF | −5.6 |

| CR455093 | KNTC2 | −5.6 |

| DR749295 | CENPA | −6.1 |

| BF043168 | NEK2 | −6.2 |

| AW461931 | IQGAP3 | −7 |

| CR452593 | TMSL8 | −7.8 |

| CN440232 | KIF11 | −8.1 |

| CN433506 | KIAA0101 | −9.4 |

| CN433360 | TOP2A | −12.2 |

| CN434640 | DLG7 | −16.8 |

| Cell adhesion | ||

| CN437044 | CDH15 | 2.9 |

| CR454464 | VCL | 2.7 |

| CN442238 | TMEM204 | −3.5 |

| CN435183 | THBS2 | −4.9 |

| Transport | ||

| CR455643 | TF | −2.7 |

| NM_174782 | SLC12A2 | −5 |

| Intracellular trafficking | ||

| CR453444 | AP3D1 | 2.2 |

| BM251684 | SYTL1 | −2 |

| CR453562 | KIF20A | −3.5 |

| Inflammatory & immune functions | ||

| NM_173982 | AGER | 2.8 |

| BF044563 | ALOX5AP | −2 |

| BF041442 | ELMOD3 | −2 |

| BF040320 | C1RL | −2.9 |

| BF042057 | IL18BP | −3 |

| AY247821 | FCAR | −3.6 |

| BF440567 | HLA-A1 | −3.7 |

| BF044309 | LILRB6 | −4 |

| CN440842 | PF4 | −5.2 |

| BF043950 | CCL2 | −8.6 |

| Energy production and metabolism | ||

| AW464548 | CTSK | 3.1 |

| CR452848 | TRA1 | 2.4 |

| BF440264 | ZDHHC2 | −2 |

| CN440619 | NAAA | −2 |

| AW464985 | USP9X | −2.2 |

| CR453258 | ATP5G1 | −2.3 |

| CK728068 | ACOX3 | −2.4 |

| AW464210 | DPP4 | −2.4 |

| BF041253 | FAR2 | −3.3 |

| Other functions | ||

| NM_174566 | OPN1LW | −2 |

| CR455862 | MBP | −2.1 |

| CR552253 | CALD1 | −2.2 |

| BF440451 | CLEC2D | −2.5 |

| BF440280 | ANXA3 | −3.4 |

| CR452494 | COL1A2 | −5.3 |

| Uncharacterized | ||

| BM361913 | mRNA sequence | 19.5 |

| DR697542 | mRNA sequence | 7.6 |

| BF042955 | mRNA sequence | 3.1 |

| BF046062 | DBNDD1 | 2.4 |

| CN433011 | mRNA sequence | −2 |

| AY563829 | Transcribed locus | −2.1 |

| AW465803 | Transcribed locus | −2.1 |

| CN437617 | NKD2 | −2.1 |

| CN437228 | mRNA sequence | −2.2 |

| CN440381 | Transcribed locus | −2.2 |

| AW463556 | mRNA sequence | −2.2 |

| DR749282 | Transcribed locus | −2.2 |

| BF043021 | mRNA sequence | −2.3 |

| CR454941 | Transcribed locus | −2.3 |

| CN432553 | NRM | −2.3 |

| CN440892 | Transcribed locus | −2.3 |

| BF040477 | mRNA sequence | −2.3 |

| BF040697 | mRNA sequence | −2.4 |

| CN440892 | Transcribed locus | −2.4 |

| CN435160 | Transcribed locus | −2.5 |

| CN437807 | mRNA sequence | −2.5 |

| BF440307 | mRNA sequence | −2.7 |

| CN438535 | mRNA sequence | −2.8 |

| BF440292 | mRNA sequence | −2.8 |

| CR454384 | GPATCH8 | −2.8 |

| BM362405 | SUSD3 | −2.9 |

| TC222073 | mRNA sequence | −3 |

| CN435160 | Transcribed locus | −3 |

| BF044422 | Transcribed locus | −3.1 |

| CB423716 | Transcribed locus | −3.2 |

| BM363262 | LOC513111 | −3.2 |

| CN432697 | Transcribed locus | −3.2 |

| CR452791 | mRNA sequence | −3.4 |

| AW463283 | Transcribed locus | −3.4 |

| AW461570 | C23H6orf129 | −3.5 |

| BF043154 | Transcribed locus | −3.6 |

| CN438539 | mRNA sequence | −3.6 |

| BM363349 | mRNA sequence | −3.8 |

| CN438081 | Transcribed locus | −3.8 |

| BM366640 | Transcribed locus | −3.9 |

| CR553166 | mRNA sequence | −4.2 |

| BM364214 | LOC618541 | −4.3 |

| CN441931 | Transcribed locus | −4.4 |

| CN436436 | Transcribed locus | −4.6 |

| CN440116 | mRNA sequence | −4.6 |

| CN436425 | Transcribed locus | −5.1 |

| CN436345 | Transcribed locus | −5.3 |

| CN433474 | mRNA sequence | −5.4 |

| CR453971 | Transcribed locus | −5.4 |

| BM366656 | Transcribed locus | −5.8 |

| CN436426 | mRNA sequence | −6.4 |

| CN441242 | mRNA sequence | −6.9 |

| CN435532 | Transcribed locus | −8.8 |

| CR453356 | mRNA sequence | −12.5 |

| CR553566 | Transcribed locus | −47 |

Negative sign (−) before the number indicates down-regulation of the gene.

Figure 4. Proportional representation of the biological processes groups of differentially expressed genes between uninfected bovine R and S monocyte-derived macrophages. Detailed information is presented in Table 2.

Brucella-infected S MDMs had a down-regulated transcriptome at 12h post-B. abortus infection

B. abortus S2308 infection induced alteration in the signal intensity values of 241 different genes (46 up- and 195 down-regulated) in S MDMs at 12h p.i. compare to uninfected cells (Table 3). One hundred forty-four (60%) of these 241 genes have known function or blast searches revealed high similarity to genes with known functions, with 22 (15%) of them up- and 116 (85%) down-regulated. Up-regulated genes with known function were randomly distributed among different functional categories, with higher proportions in cell adhesion (4/6) and immune response (3/6) clusters. Conversely, the majority of characterized down-regulated genes at 12h p.i. had some bias to some specific functions such as cell development, growth and differentiation (30/33), protein biosynthesis, folding and catabolism (24/27), general metabolism (16/20), signal transduction (11/13), intracellular trafficking (6/6), transcription regulation and mRNA processing (9/9), transport (8/9) and DNA replication and repair (7/9). Analysis of individual immune and inflammatory-associated genes differentially expressed reveals that B. abortus induce an up-regulation in IL-1A, CCL2, CCL5 and RANTES and a down-regulation of HSPA14, TCIRG1 and C1QBP genes during the first 12 h p.i. infection. Altogether, these data indicate that B. abortus induce a down-regulation of Th1 subset of immune response and arrest the cell cycle in infected S MDMs at 12h p.i.

Table 3.

Genes significantly up - regulated in B. abortus – infected monocyte-derived macrophages from bovine naturally susceptible to brucellosis 12 h post-infection, compared to uninfected cells.

| Sequence identifier |

Gene symbol | Fold- change |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA replication and repair | |||

| CN436535 | RAD51AP1 | 2 | 0.012798 |

| CN440965 | MEN1 | 2 | 0.033644 |

| BM363362 | HP1BP3 | −2.1 | 0.014615 |

| CR451784 | SSRP1 | −2.1 | 0.001088 |

| BF042701 | XRCC5 | −2.2 | 0.028438 |

| AW463670 | CHD3 | −2.3 | 0.010785 |

| CN433291 | H2AFX | −2.3 | 0.00807 |

| CR452840 | ATIC | −2.3 | 0.03416 |

| BM366355 | CHRAC1 | −2.5 | 0.020614 |

| Transcription regulation and RNA processing | |||

| CN434076 | RBM23 | −2 | 0.001493 |

| BF044611 | SKIV2L2 | −2 | 0.019285 |

| CN439289 | ZNF211 | −2 | 0.04369 |

| CN435437 | SNRPG | −2.1 | 0.02193 |

| BF440611 | QKI | −2.1 | 0.028399 |

| CR453755 | TINP1 | −2.2 | 0.002914 |

| CR454921 | TAF11 | −2.4 | 0.048223 |

| BF440603 | DNTTIP2 | −2.4 | 0.010831 |

| DR697555 | IGF2BP3 | −3.7 | 0.033597 |

| Cell development, growth and differentiation | |||

| CK846466 | CBLN1 | 4.2 | 0.010537 |

| AW466205 | CIDEA | 2.2 | 0.030579 |

| NM_205787 | REG3A | 2.2 | 0.006797 |

| BF045587 | AATF | −2 | 0.014579 |

| CR451700 | MLF2 | −2 | 0.043153 |

| CN438718 | SKIL | −2 | 0.035406 |

| CN434165 | PIGU | −2 | 0.01877 |

| CK959975 | ANGPT4 | −2 | 0.047019 |

| BF045982 | EPB41L2 | −2 | 0.044067 |

| AW462514 | GSPT1 | −2 | 0.007692 |

| AW461998 | CSRP1 | −2 | 0.029829 |

| CN440711 | OPTN | −2.1 | 0.048056 |

| BF039833 | CCRK | −2.1 | 0.035498 |

| AW463034 | AKAP12 | −2.1 | 0.041319 |

| CN437378 | ARPC1B | −2.2 | 0.002672 |

| CN436304 | SMC4 | −2.2 | 0.040856 |

| BF440228 | TGFBR3 | −2.2 | 0.022062 |

| BM363735 | AIF1 | −2.3 | 0.003817 |

| NM_174005 | CCIN | −2.3 | 0.004703 |

| CR454883 | MEST | −2.3 | 0.019538 |

| CR451635 | GTSE1 | −2.3 | 0.003521 |

| CN440112 | MINA | −2.3 | 0.00067 |

| CK943499 | TACC2 | −2.3 | 0.04264 |

| CR452742 | ENC1 | −2.3 | 0.007579 |

| BF440347 | FGD3 | −2.3 | 0.021089 |

| AW463810 | EAPP | −2.3 | 0.006253 |

| NM_174209 | UACA | −2.4 | 0.012996 |

| BF045016 | ZMYM3 | −2.4 | 0.02123 |

| AW462369 | RARRES1 | −2.4 | 0.001494 |

| CB421393 | BBS7 | −2.6 | 0.014228 |

| AW462158 | DDX28 | −2.6 | 0.015702 |

| BM365145 | TUSC4 | −2.8 | 0.01158 |

| AW463470 | NCAPD2 | −3 | 0.015283 |

| Transport | |||

| NM_174071 | GLRB | 2.6 | 0.04727 |

| CR454289 | TNPO3 | −2 | 0.038832 |

| BF046658 | TIMM50 | −2 | 0.030007 |

| CR455688 | FDX1L | −2 | 0.006493 |

| CN437583 | CLNS1A | −2.1 | 0.001805 |

| BF040012 | SLC19A2 | −2.1 | 0.010527 |

| BM363775 | CLIC1 | −2.2 | 0.011465 |

| NM_174371 | KCNA4 | −2.5 | 0.01934 |

| BF043853 | SYT4 | −2.7 | 0.015922 |

| Metabolism | |||

| CB446606 | CA8 | 4 | 0.011733 |

| BF039557 | LOC785314 | 2.6 | 0.002684 |

| NM_201527 | SOD2 | 2.6 | 0.040638 |

| BF043599 | ATAD4 | 2.1 | 0.01223 |

| CR455483 | CRYZ | −2 | 0.023141 |

| CR452141 | NAT12 | −2 | 0.035025 |

| CN437401 | DPM1 | −2 | 0.038338 |

| BF044835 | DIP2B | −2 | 0.038872 |

| BF043099 | GSTK1 | −2 | 0.024588 |

| CN435685 | RGN | −2 | 0.002805 |

| AW464776 | TXN2 | −2.1 | 0.025333 |

| AW462172 | ARSB | −2.1 | 0.038167 |

| CN437243 | ISCU | −2.2 | 0.002229 |

| CN432284 | PIK3C3 | −2.2 | 0.019429 |

| DR697431 | LOC782666 | −2.3 | 0.005903 |

| AW461872 | MSR1 | −2.3 | 0.006326 |

| CN434081 | PCCB | −2.4 | 0.009599 |

| AW261169 | PCCA | −2.5 | 0.003671 |

| AW266859 | MSRB2 | −2.7 | 0.008601 |

| BF041637 | GNPAT | −3.6 | 0.024213 |

| Protein processing | |||

| BF040619 | NEDD4L | 2.8 | 0.027674 |

| BM431662 | SPINK1 | 2.2 | 0.04782 |

| NM_181008 | CSN2 | 2 | 0.038672 |

| CR454222 | MRPL3 | −2 | 0.029686 |

| CO895992 | ASPA | −2 | 0.001912 |

| BF046090 | FBXO11 | −2 | 0.022913 |

| BF042334 | RPS6KC1 | −2 | 0.016106 |

| CR553712 | OS9 | −2 | 0.006614 |

| BF044848 | UBE2V2 | −2 | 0.011541 |

| CR553513 | UCHL5 | −2.1 | 0.01485 |

| CR552645 | DUSP12 | −2.1 | 0.00738 |

| CR454607 | MRPL13 | −2.1 | 0.021589 |

| CR453519 | RPL35A | −2.1 | 0.006397 |

| CR452490 | RPL5 | −2.1 | 0.01003 |

| BM364981 | PFDN5 | −2.1 | 0.00125 |

| BF046118 | PSMD1 | −2.1 | 0.010022 |

| BF045731 | VBP1 | −2.1 | 0.004496 |

| CR453689 | RPL22 | −2.2 | 0.015299 |

| CR453525 | RPS6 | −2.2 | 0.043312 |

| BF045932 | MRPS11 | −2.2 | 0.002001 |

| BF045297 | RPL10 | −2.2 | 0.048448 |

| AW465874 | ARIH1 | −2.2 | 0.027491 |

| CR454940 | ST3GAL6 | −2.2 | 0.001991 |

| BM366593 | DNAJA3 | −2.2 | 0.01866 |

| BF042101 | SHMT2 | −2.3 | 0.013722 |

| CN434588 | FKBP3 | −2.8 | 0.008926 |

| CN441491 | SIAH1 | −3 | 0.007214 |

| Signal transduction | |||

| M_001001149 | CALCB | 2.7 | 0.001067 |

| NM_174406 | NXPH2 | 2.6 | 0.042586 |

| NM_174236 | AKAP5 | −2 | 0.001748 |

| BF043621 | PYGO2 | −2 | 0.018663 |

| BM363977 | TBC1D9 | −2 | 0.008686 |

| BF440275 | TNIK | −2 | 0.016256 |

| AU279004 | TM2D3 | −2 | 0.00015 |

| CN436332 | CNIH4 | −2.1 | 0.007068 |

| CN437637 | CALR | −2.2 | 0.012659 |

| CN440743 | GKAP1 | −2.2 | 0.020772 |

| CR456175 | S100A10 | −2.3 | 0.004438 |

| CN438280 | GNB5 | −2.7 | 0.045939 |

| CR453647 | AMFR | −2.9 | 0.018384 |

| Intracellular trafficking | |||

| DR697451 | ENAH | −2 | 0.014658 |

| AW465699 | ARF6 | −2 | 0.010549 |

| CF613563 | ATG5 | −2 | 0.033296 |

| BF040141 | RAB24 | −2.2 | 0.001572 |

| BF039386 | COG2 | −2.4 | 0.047562 |

| BM362494 | GBF1 | −2.5 | 0.002042 |

| Cell adhesion | |||

| CN435936 | SPP1 | 7.8 | 0.006672 |

| BF043281 | GJA3 | 2.4 | 0.010211 |

| NM_174280 | CNTN1 | 2.2 | 0.031111 |

| L27869 | NRXN3 | 2.2 | 0.035758 |

| BF043702 | CEACAM8 | −2.2 | 0.004872 |

| CN439886 | GPM6B | −2.2 | 0.021116 |

| Inflammatory and immune response | |||

| X12497 | IL1A | 5.3 | 0.029947 |

| BF043950 | CCL2 | 3.2 | 0.04788 |

| BM363499 | CCL5 | 2.8 | 0.04067 |

| CR553339 | HSPA14 | −2 | 0.007621 |

| AW462950 | TCIRG1 | −2.2 | 0.026645 |

| CN433781 | C1QBP | −2.3 | 0.00346 |

| Unknown function | |||

| CK394086 | GRAMD1C | 4.7 | 0.005583 |

| CR453360 | mRNA seq | 3.6 | 0.028089 |

| CN434319 | Transcr locus | 3.5 | 0.003021 |

| CR552017 | INDOL1 | 3.2 | 0.005439 |

| BF042120 | mRNA seq | 2.9 | 0.011408 |

| BF040440 | Transcr locus | 2.9 | 0.013091 |

| BM364050 | mRNA seq | 2.8 | 0.045414 |

| CK394163 | Transcr locus | 2.6 | 0.038814 |

| AW464659 | mRNA seq | 2.6 | 0.021362 |

| BF042444 | Transcr locus | 2.6 | 0.030362 |

| AY563735 | mRNA sequ | 2.6 | 0.017374 |

| CN438563 | mRNA | 2.5 | 0.038378 |

| DR749459 | mRNA seq | 2.4 | 0.024572 |

| CR454841 | mRNA seq | 2.2 | 0.005294 |

| CN435906 | mRNA seq Hypothetical |

2.1 | 0.04738 |

| CK394134 | LOC100174927 | 2.1 | 0.012865 |

| BM363550 | mRNA seq | 2.1 | 0.010831 |

| AW463075 | mRNA sequ | 2.1 | 0.011975 |

| AW656826 | Transcr locus | 2.1 | 0.0332 |

| DR749406 | ALKBH4 | 2 | 0.037488 |

| CN441759 | KIAA0406 | 2 | 0.020521 |

| CN436628 | Transcr locus | 2 | 0.025941 |

| CR454029 | Transcr locus | 2 | 0.037561 |

| CN438621 | mRNA sequ | 2 | 0.044158 |

| CV798869 | Transcr locus | −2 | 0.005075 |

| CR553807 | MORN2 | −2 | 0.008144 |

| CR553297 | DONSON | −2 | 0.016478 |

| CR552451 | Transcr locus | −2 | 0.016826 |

| CR550949 | ENKUR | −2 | 0.039676 |

| CR452826 | TMCC3 | −2 | 0.043398 |

| CN441384 | mRNA seq | −2 | 0.013879 |

| CN437904 | Transcr locus | −2 | 0.02252 |

| CN433518 | Transcr locus | −2 | 0.011052 |

| CN433286 | Transcr locus | −2 | 0.026338 |

| BM364672 | C21orf59 | −2 | 0.008 |

| BM362937 | mRNA seq | −2 | 0.016551 |

| BF440346 | CCDC125 | −2 | 0.031793 |

| BF046723 | mRNA seq | −2 | 0.033449 |

| BF041501 | LOC515651 | −2 | 0.015499 |

| AW461946 | MGC128747 | −2 | 0.001249 |

| AW465670 | mRNA sequ | −2 | 0.032058 |

| CN440220 | LOC617694 | −2 | 0.021621 |

| BE722725 | Transcr locus | −2 | 0.03681 |

| BF044805 | Transcr locus | −2 | 0.014413 |

| AW465807 | Transcr locus | −2 | 0.003764 |

| CR452356 | LOC506074 | −2.1 | 0.004625 |

| CN437533 | Transcr locus | −2.1 | 0.010029 |

| CN437200 | C1orf52 | −2.1 | 0.029358 |

| CN436474 | MGC148355 | −2.1 | 0.042662 |

| CN435422 | mRNA seq | −2.1 | 0.004848 |

| BM364118 | mRNA seq | −2.1 | 0.034525 |

| BM363762 | Transcr locus | −2.1 | 0.024959 |

| BF041485 | Transcr locus | −2.1 | 0.001438 |

| BF040156 | FAM96A | −2.1 | 0.02247 |

| AY563713 | Transcr locus | −2.1 | 0.024982 |

| AW463226 | C7H5orf15 | −2.1 | 0.002516 |

| CN433567 | MGC139126 | −2.1 | 0.003927 |

| BF440393 | Transcr locus | −2.1 | 0.029318 |

| DR697587 | Transcr locus | −2.2 | 0.017607 |

| CN441772 | CCDC90A | −2.2 | 0.019245 |

| CN439397 | Transcr locus | −2.2 | 0.044367 |

| CN438023 | Transcr locus | −2.2 | 0.008942 |

| BM364157 | mRNA seq | −2.2 | 0.020096 |

| BF440257 | Transcr locus | −2.2 | 0.024855 |

| BF045639 | Transcr locus | −2.2 | 0.043847 |

| BF044066 | YIPF2 | −2.2 | 0.047593 |

| AW463110 | LOC514162 | −2.2 | 0.00779 |

| AW461934 | TMEM165 | −2.2 | 0.008286 |

| CN439481 | Transcr locus | −2.2 | 0.018453 |

| BM363176 | WDR54 | −2.2 | 0.045691 |

| CR454316 | TCTEX1D2 | −2.3 | 0.019889 |

| BM363007 | mRNA seq | −2.3 | 0.030154 |

| BM362963 | TMEM183A | −2.3 | 0.004398 |

| BF045994 | mRNA seq | −2.3 | 0.001834 |

| BF040988 | Transcr locus | −2.3 | 0.004564 |

| CR453653 | Transcr locus | −2.3 | 0.044028 |

| CR455800 | Transcr locus | −2.4 | 0.018999 |

| CR453901 | RSRC2 | −2.4 | 0.044236 |

| CR451871 | Transcr locus | −2.4 | 0.007411 |

| BM364112 | mRNA seq | −2.4 | 0.018626 |

| BF043474 | LOC507724 | −2.4 | 0.029765 |

| AY563886 | mRNA seq | −2.4 | 0.011197 |

| CN438652 | Transcr locus | −2.4 | 0.045309 |

| BM364672 | C1H21ORF59 | −2.4 | 0.010719 |

| CN436507 | LENG8 | −2.4 | 0.026297 |

| CN434826 | mRNA seq | −2.5 | 0.010429 |

| BF440233 | mRNA seq | −2.5 | 0.031531 |

| BF044267 | ZC3H11A | −2.5 | 0.005648 |

| DR749252 | mRNA seq | −2.6 | 0.007047 |

| CN434082 | Transcr locus | −2.6 | 0.003073 |

| BF440521 | mRNA seq | −2.6 | 0.026848 |

| BF043361 | NIPSNAP1 | −2.6 | 0.018738 |

| AW464396 | TMCC1 | −2.6 | 0.032342 |

| CN439836 | Transcr locus | −2.6 | 0.016679 |

| BF044820 | DCTN6 | −2.6 | 0.049392 |

| BF440233 | mRNA sequ | −2.6 | 0.045429 |

| CN432742 | C3H1orf50 | −2.7 | 0.029089 |

| BF039679 | mRNA seq | −2.7 | 0.005038 |

| DR749422 | LOC513273 | −2.8 | 0.01908 |

| DR697523 | Transcr locus | −2.8 | 0.039045 |

| CR550825 | Transcr locus | −2.9 | 0.037771 |

| AW266853 | mRNA seq | −3 | 0.003122 |

| BF041611 | Transcr locus | −8 | 0.046242 |

Negative sign (−) before the number indicates down-regulation of the gene.

B. abortus infection stimulates modest alteration of transcript levels in R MDMs at 12h post-infection

The infection assays disclosed that the number of intracellular B. abortus in R MDMs was 18% lower at T12 (12h p.i.) than at T0 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). Microarray analysis identified B. abortus infection induced alteration in the signal intensity values of 56 different genes in R MDMs at 12h post-infection compared to uninfected controls (Table 4). Of these 56 genes, 31 were up- and 25 were down-regulated, but only 21 of these 56 genes (37.5%) had assigned functions (11 up- and 10 down-regulated). Individual analysis of differentially expressed genes with known function revealed that R MDMs mounted a type 1 immune response to B. abortus infection, which is the opposite of what was observed in S MDMs. These inferences correlate with the up-regulation of CCL4 (or MIP-1b) and the reduced expression of the activator of B-lineage gene expression (EBF1) and oncostatin M-specific receptor beta (OSMR-b). Also contrary to what was observed in infected S MDMs, the analysis of microarray data indicates that cell proliferation is active in infected R MDMs. Altogether these data indicate that B. abortus modestly induce a genome activation in bovine R MDMs during the first 12h p.i. infection, with bias to type 1 immune response and no host cell activity modification.

Table 4.

Genes significantly altered in B. abortus – infected monocyte-derived macrophages from bovine naturally resistant to brucellosis 12h post-infection, compared to uninfected cells.

| Sequence identifier |

Gene symbol | Fold- change |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA replication & repair | |||

| CK776451 | RAD18 | 2 | 0.005927 |

| CK770264 | RAD51L1 | −2.2 | 0.002847 |

| Transcription regulation | |||

| CR454810 | COMMD7 | 2.2 | 0.048429 |

| AW465701 | RCOR1 | 2 | 0.03685 |

| CR452102 | RMP | 2 | 0.000759 |

| CR453476 | EBF1 | −2.1 | 0.01349 |

| Cell proliferation | |||

| BF045152 | PDGFC | 2.3 | 0.029767 |

| CN439003 | MARCKSL1 | 2.1 | 0.029038 |

| BF440414 | BCL2A1 | 2 | 0.027301 |

| Immune response | |||

| BM364954 | CCL4L1 | 2 | 0.023221 |

| AW463280 | OSMR | −2.2 | 0.035044 |

| Metabolism | |||

| CK981355 | CA8 | 2.5 | 0.013259 |

| CN435598 | LRRC47 | −2.2 | 0.022079 |

| CR453715 | RPS27 | −2.3 | 0.047924 |

| CN442150 | FBXL12 | −3.3 | 0.004795 |

| Transport | |||

| CN437407 | KCTD13 | 2.1 | 0.023717 |

| Intracellular transport | |||

| BF042139 | LOC619125 | −2.6 | 0.008686 |

| Cell adhesion | |||

| CR552676 | COL3A1 | −2.3 | 0.012799 |

| DR697491 | CRISPLD2 | −2.8 | 0.033894 |

| Signal transduction | |||

| CR452358 | GPR155 | 2 | 0.02611 |

| CN437082 | REM2 | −2.2 | 0.031759 |

| Unknown function | |||

| CR551153 | LOC785824 | 5.8 | 0.031443 |

| DR749367 | Trcr locus | 5.2 | 0.016925 |

| NG010005B14F03 | mRNA sequence | 3.5 | 0.02925 |

| CK394002 | mRNA sequence | 2.4 | 0.015736 |

| BF039815 | mRNA sequence | 2.4 | 0.039986 |

| CN437846 | Trcr locus | 2.3 | 0.009568 |

| AW462726 | Trcr locus | 2.2 | 0.030233 |

| CN441215 | Trcr locus | 2.1 | 0.02319 |

| AW463633 | PTPLB | 2.1 | 0.028519 |

| DR697311 | TM9SF4 | 2.1 | 0.045581 |

| BF042044 | mRNA sequence | 2.1 | 0.041983 |

| CN439741 | Trcr locus | 2.1 | 0.044695 |

| CN434587 | Trcr locus | 2.1 | 0.031319 |

| BF045605 | Trcr locus | 2 | 0.039534 |

| CR452655 | Trcr locus | 2 | 0.034942 |

| TC225637 | mRNA sequence | 2 | 0.036141 |

| BM362622 | KIAA1797 | 2 | 0.014768 |

| CV798711 | mRNA sequence | 2 | 0.002806 |

| CN440913 | mRNA sequence | 2 | 0.018244 |

| CV798772 | CCDC62 | 2 | 0.043505 |

| AW461867 | TMEM86A | −2 | 0.028343 |

| CN439630 | Trcr locus | −2 | 0.046217 |

| CN441187 | Trcr locus | −2 | 0.006074 |

| DR749216 | mRNA sequ | −2 | 0.03689 |

| CN434275 | Trcr locus | −2.1 | 0.034322 |

| CR551689 | GALNTL1 | −2.2 | 0.042343 |

| AW464049 | Trcr locus | −2.3 | 0.03765 |

| NM_174508 | BTN1A1 | −2.3 | 0.047924 |

| CN441319 | mRNA sequ | −2.3 | 0.040534 |

| BF039032 | Trcr locus | −2.4 | 0.017324 |

| CR452929 | LOC513129 | −2.5 | 0.034724 |

| BM364151 | mRNA sequ | −2.6 | 0.008686 |

| BM364245 | mRNA sequ | −2.6 | 0.001497 |

| X95395 | mRNA sequ | −2.8 | 0.004258 |

| CR454451 | Trcr locus | −2.8 | 0.002231 |

Negative sign (−) before the number indicates down-regulation of the gene.

Discussion

Our initial results indicate that B. abortus attach and internalize less efficiently in R than S MDMs. This result is in line with those obtained by Campbell et al. (1994), who found that MDMs from R cattle were less permissive to invasion by B. abortus 2308 than MDMs from S animals. These authors also found that the pathogen was bound to different surface’s molecules on R or S MDMs, influencing the intracellular fate of Brucella. It is well known that Brucella is an intracellular pathogen that has the ability of survive and replicate inside professional phagocytic cells (Roop II et al., 2004); therefore, the lower internalization of Brucella in R MDMs is integral to the host innate response to reduce Brucella’s opportunities to establish an intracellular niche for replication. Also in concordance with Campbell and Adams (1992), we observed that the number of intracellular Brucella at 12h p.i. increased in S MDMs but was decreased in R MDMs, which indicates that R MDMs kill more efficiently and inhibit B. abortus intracellular replication in the first 12 h p.i than S MDMs.

Immune response mechanisms are required by hosts to protect themselves from microbial invaders. The innate immune response is not only the first barrier of defense but also induces and modulates the acquired immune response, a more powerful and prolonged specific response. Previous studies have shown that Th1 cellular immune response is effective to promote Brucella clearance from the host (Dornand et al., 2002; Rolán and Tsolis, 2008), while Th2 is detrimental for controling B. abortus infection (Fernandez and Baldwin, 1995). To identify infection-independent molecular differences in B. abortus innate resistance, we compared the transcriptomes of uninfected S and R MDMs. Our data revealed that uninfected R MDMs had enhanced Th1 expression and reduced Th2-immune response-related genes, compared to gene expression profiles of S MDMs. The enhancement of type 1 cytokine response in uninfected R MDMs was correlated with the down-regulated expression of IL18BP, an inhibitor of the IL18– induced IFNγ production (Novick et al., 1999). IFNγ was demonstrated to be crucial to inhibit B. abortus intracellular growth (Murphy et al., 2001), and IL18BP down-regulation may be related to mechanisms that stimulate the early Th1-host protected immune response. The C1RL gene encodes the first component of the classical complement pathway that it is activated by the antigen-antibody complex, and FCAR gene encodes the Fc receptor for IgA. The lower number of transcripts from C1RL and FCAR genes detected in R MDMs may correlate with the weak contribution that antibodies play in the role protecting against Brucella infections (Harmon et al., 1985; Baldwin and Goenka, 2006). In addition, the lower number of Fc receptors on R MØ may significantly reduce the opportunity for B. abortus to attach and invade mononuclear phagocytes (Campbell et al., 1994). Genes encoding chemoattractant products to polymorphonuclear (PMN) neutrophilic leukocytes and mononuclear phagocytic cells such as ALOX5AP, PF4 (also called CXCL4) and CCL2 (or MCP1) (Deuel et al., 1981; Meter et al., 2005) also had lower expression in uninfected R than in S MDMs. These data suggest that Brucella may take advantage of the higher predisposition of S animals to recruit phagocytic cells to hide inside and thus avoid the more deleterious extracellular environment. Simultaneously, PF4 has an anti-apoptotic activity in monocytes (Scheuerer et al., 2005), which is also enhanced by Brucella after invasion (Gross et al., 2000). Collectively, these observations may indicate that Brucella infection is enhanced by the more prolonged half life in S MDMs, which may be advantageous to the intracellular life style of the pathogen. In parallel, the observed down-regulation of CCL2 transcription would be expected to contribute to the Th1 immune response polarization (Omata et al., 2002; Del Corno et al., 2009) of R MDMs. On the other hand, no apparent association could be established between R phenotype to brucellosis and the down-regulated expression of HLA-A (or BoLA) gene. HLA-A encodes a heavy chain of the MHC-I. Foreign peptides derived from intracellular synthesized antigens (mainly virus) are presented in association with MHC-I and recognized by CTLs-CD8+. However, this mechanism does not seem to be relevant during Brucella infection, as bovine lymphocytes expressing CD8+ molecules do not react with B. abortus and MHC-I – knockout mice controlled and cleared B. abortus infection as well as wild type mice (Smith III et al., 1990; Baldwin and Parent, 2002).

Two non-immune related genes differentially expressed between uninfected R and S MDMs that could influence the natural resistance to brucellosis in cattle were transferrin (TR) and tumor rejection antigen (TRA1). TR is a serum protein that transports iron from storage sites to all proliferating cells in the body. Paradoxically, iron is not only an essential element to promote bacteria growth (Finlay and Falkow, 1997) but is also involved in anti-microbial mechanisms (Babior, 1984). In concordance with the observation that increased levels of iron correlate with increased susceptibility to infectious disease (Ampel et al., 1989), the lower expression of TR gene in R animal may, in part, explain the restricted intracellular growth of B. abortus in R MDMs. TRA1 (also known as GP96/GRP94) encodes a molecular chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. In addition to the role in refolding denatured proteins after stress, the product of this gene is involved in a cross-priming process, which includes the uptake, processing and presentation of antigens by professional APCs (Warger et al., 2006). Simultaneously, it was also shown that GP96 gene product binds bacterial LPS and augments its biological activity. It is well known that Brucella presents an unconventional LPS that allows the pathogen to evade innate immunity (Lapaque et al., 2005). Collectively, these data indicate that R MDMs may have the ability to amplify its innate immune response to Brucella infection due to the higher number of GP96 molecules that would attach to B. abortus LPS and augment its biological activity. It is not immediately clear how several other differentially expressed genes between uninfected R and S MDMs might contribute to susceptibility or resistance of cattle to B. abortus infection; it is possible that some of the differences in transcript levels observed might be individual variation however others are related to resistance / susceptibility to B. abortus infection.

The analysis of microarray performed with RNA extracted from B. abortus-infected S MDMs revealed up-regulation in some inflammation-associated host genes during B. abortus infection, such as IL-1A, CCL2 and CCL5. IL-1 is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine with pleiotropic effects. However, this interleukin has not been found to have an effect on intracellular Brucella growth (Jiang and Baldwin, 1993), although it does play a critical role in the development of Th2 cell cytokine production (Manetti et al., 1994). CCL2 (also called MCP-1) and CCL5 (or RANTES) are chemotactic cytokines for monocytes to the inflammatory site. The up-regulation of these genes after B. abortus infection may indicate that the pathogen enhances the influx of the mononuclear phagocytic cells to the already predisposed host to the site only to infect the MDMs and remain protected from external stimulus. Simultaneously, CCL2 modulates incoming monocytes differentiation into dendritic cells and inhibits Th1 cell development (Omata et al., 2002). In parallel, abortion is the main clinical symptom of brucellosis in cattle, but little is known about the molecular mechanism. In a recent publication, it was demonstrated that the increased expression of RANTES contributes to abortion in B. abortus-infected pregnant mice (Watanabe et al., 2008). This finding enables speculation that the increase rate of abortion induced in S cows after challenging with B. abortus (Harmon et al., 1985) could be in part due to the increased expression of RANTES gene. Also among immune-related genes, microarray analysis displayed decreased expression of HSPA14, TCIRG1 and C1QBP genes at 12 h post-B. abortus infection in S MDMs. HSPA14 encodes for a heat shock protein from the Hsp70 family. Proteins from this family were demonstrated to have potent effects polarizing immune responses toward Th1 (Wan et al., 2009), while the product of TCIRG1 gene induces T cell activation, IL-2 secretion and IFNγ expression (Utku et al., 1998), all elements that contribute to eliminate Brucella from the host. Altogether, these data indicate that B. abortus induces a down-regulation of Th1 subset of immune response in S MDMs, which would be expected to contribute to chronic brucellosis.

Another interesting finding from the infected S MDMs gene expression analysis indicates that the cell cycle is largely arrested in infected cells at 12h p.i. (Table 3). The down-regulation of the great majority of genes clustered in DNA replication, transcription regulation and cell growth and proliferation groups are in concordance with the lower number of transcripts from protein metabolism-encoding genes detected in infected compared to uninfected MDMs. Similar results were observed in mouse MDMs infected with B. abortus at earlier time point (Eskra et al., 2003; He et al., 2006). Perhaps, reduced host metabolism is necessary for B. abortus to survive and replicate inside MDMs. Considering the numbers and types of genes with decreased expression in S MDMs at 12 h p.i., it is possible that susceptibility results from the inability of MDMs to mount appropriate immune responses against invading Brucella as well as dampening of required general cell physiology and metabolism.

On the other hand, the analysis of microarray results revealed that R MDMs mounted a type 1 immune response to B. abortus infection. These inferences correlate with the up-regulation of CCL4 (or MIP-1b) (Schrum et al., 1996) and the reduced expression of EBF1, an activator of B-lineage gene expression (Roessler et al., 2007). Transcription and secretion of CCL4 by mononuclear phagocytes is induced by IFNγ (Hariharan et al., 1999), and its product is chemotactic for T helper1 cells (Siveke and Hamann, 1998) and a co-activator of MDMs (Dorner et al., 2002). OSMR encodes for an oncostatin M-specific receptor beta that is specifically activated by oncostatin M (OSM) (Mosley et al., 1996). Deficient expression of this gene facilitates an enhanced influx of monocytic cell trafficking into the site of inflammation with NF-kB activation (Hams et al., 2008). Normally, B. abortus infection induces minimal levels of cytokines and does not generate an inflammatory response (Barquero-Calvo et al., 2007) therefore the lower expression of OSMR gene could be part of the more active innate immune response in R MDMs that enhances control of B. abortus replication. Also contrary to what was observed in infected S MDMs, the analysis of microarray data indicates that cell proliferation is active in infected R MDMs. This fact is supported by the increased transcription of cell proliferation-induced genes such as PDGFC (Platelet Derived Growth Factor C) and MARCKSL1, the anti-apoptotic gene BCL2A1 and the up-regulation of the DNA-replicative gene KCTD13 (or PDIP1) (He et al., 2001) as well. The up-regulation of these cell cycle progresion-induced genes and the sub-expression of RAD51 gene, which encodes the catalytic component in homologous recombination (Lundin et al., 2003), suggest that the intracellular presence of Brucella does not significantly interfere with the cell physiological processes, and the pathogen does not generate host DNA damage in R MDMs in the first 12h p.i. On the other hand, the up-regulation of RAD18, another DNA damage repair gene, is somewhat contradictory. The product of RAD18 gene accumulates in nuclei after UV irradiation and double-strand breakage in cells entering S-phase and acts as a proximal signal to recruit Y-family polymerases to bypass damaged DNA (Kakar et al., 2008). These data are in concordance with the active, continuous proliferative capability of infected R MDMs. Recently, it was revealed that B. abortus uptake choline from the host to elaborate their own phosphatidylcholine (PC), which is necessary to sustain a chronic infection process (Comerci et al., 2006). The product of the locus LOC619625 shows high similarity to the protein encoded by the S. cerevisiae SEC14 gene, which regulates the phosphatidylcholine (PC) homeostasis and the intracellular trafficking of vesicles from the trans-Golgi export pathways in yeast (Curwin et al., 2009). A down-regulation of the SEC14 implicates higher levels of host PC that negatively influences Golgi vesicle generation (Howe and McMaster, 2006). In the view of our results, we propose that the down-regulation of the LOC619625 locus stimulates increased concentrations of PC in R MDMs as a mechanism to sequester choline from the pathogen and simultaneously modulate intracellular trafficking and interfere with the establishment of the B. abortus intracellular niche. The contribution of the other differentially expressed genes in R MDMs inhibiting intracellular B. abortus survival and replication in the first 12h p.i. is challenging; however, our data clearly indicate that 1) B. abortus modestly induces a genome activation in bovine R MDMs during the onset of infection, 2) R cattle have the ability to mount a type 1 immune response against B. abortus infection, and 3) the host cell activity is not altered significantly after 12h post-B. abortus infection.

In conclusion, the data from our experiments reveal that R but not S MDMs inhibit B. abortus intracellular growth in the first 12h p.i. Gene expression analyses of both uninfected and B. abortus infected MDMs 12h p.i identified completely different sets of expressed genes, a phenomenon that was observed for both susceptible and resistant MDMs. The data highlighted that R MDMs have the ability to mount a type 1 immune response against B. abortus infection, which was impaired in S MDMs. Also, there was a general trend for greater numbers of gene expression alterations (mainly down-regulation) to occur in B. abortus infected S MDMs, as opposed much lower numbers of gene expression changes in infected R MDMs, and especially when compared to uninfected cells. Similarly, a higher number of transcriptional alterations was observed in uninfected S compared to R uninfected MDMs. We propose that a reduced extended response to B. abortus infection facilitates natural resistance to the bacteria.

Acknowledgements

Mr. Alan Patranella for taking care of the animals and blood recollection, and Mrs. Roberta Pugh and Mrs. Doris Hunter for their technical assistance. This study was supported by U.S. Department of Homeland Security – National Center of Excellence for Foreign Animal and Zoonotic Disease (FAZD) Defense grant ONR-N00014-04-1-0 and a NIH grant 2U54AI057156-06. CAR was sponsored by Fulbright-INTA scholarship from Argentina.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams LG, Templeton JW. Genetic resistance to bacterial diseases of animals. Revue Scientifique et Technique (International Office of Epizootic) 1998;17:200–219. doi: 10.20506/rst.17.1.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams LG. The pathology of brucellosis reflects the outcome of the battle between the host genome and the Brucella genome. Veterinary Microbiology. 2002;90:553–561. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00235-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ampel NM, Van Wyck DB, Aguirre ML, Willis DG, Popp RA. Resistance to infection in murine B-thalassemia. Infection and Immunity. 1989;57:1011–1017. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1011-1017.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior BM. The respiratory burst of phagocytes. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1984;73:599–601. doi: 10.1172/JCI111249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin CL, Parent M. Fundamentals of host immune response against Brucella abortus: What the mouse model has revealed about control of infection. Veterinary Microbiology. 2002;90:367–382. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin CL, Goenka R. Host immune responses to the intracellular bacteria Brucella: Does the bacteria instruct the host to facilitate chronic infection? Critical Review in Microbiology. 2006;26:407–442. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v26.i5.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barquero-Calvo E, Chaves-Olarte E, Weiss DS, Guzmán-Verri C, Chacon-Diaz C, Rucavado A, Moriyón I, Moreno E. Brucella abortus uses a stealthy strategy to avoid activation of the innate immune system during the onset of infection. Plos One. 2007;2(7):e631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel R, Feng J, Piedrahita JA, McMurray DM, Templeton JW, Adams LG. Stable transfection of the bovine NRAMP1 gene into murine RAW264.7 cells: Effect on Brucella abortus survival. Infection and Immunity. 2001;69:3110–3119. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3110-3119.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram TA, Canning PC, Roth JA. Preferential inhibition of primary granule release from bovine neutrophils by a Brucella abortus extract. Infection and Immunity. 1986;52:285–292. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.285-292.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billard E, Dornand J, Gross A. Vir B type IV secretory system does not contribute to Brucella suis avoidance of human dendritic cell maturation. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2008;53:404–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumstead N, Barrow P. Resistance to Salmonella gallinarum S. pollurum and S. enteritidis in inbred lines of chickens. Avian Disease. 1993;37:189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HS, Hughes EH, Gregory PW. Genetic resistance to brucellosis in swine. Journal of Animal Science. 1942;1:106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell GA, Adams LG. The long-term culture of bovine monocyte-derived macrophages and their use in the study of intracellular proliferation of Brucella abortus. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 1992;34:291–305. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(92)90171-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell GA, Adams LG, Sowa BA. Mechanisms of binding of Brucella abortus to mononuclear phagocytes form cows naturally resistant or susceptible to brucellosis. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 1994;41:295–306. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(94)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael J. Bovine tuberculosis in the tropics with special reference to Uganda. Part II. Experimental tuberculosis in Zebu cattle. Veterinary Journal. 1941;97:329–339. [Google Scholar]

- Caron E, Peyrard T, Kohler S, Cabane S, Liautard JP, Dornand J. Live Brucella spp. fail to induce tumor necrosis factor alpha excretion upon infection of U937-derived phagocytes. Infection and Immunity. 1994;62:5267–5274. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5267-5274.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comerci DJ, Altabe S, de Mendoza D, Ugalde RA. Brucella abortus synthesizes phophatidilcoline from coline provided by the host. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006;188:1929–1934. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.5.1929-1934.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbel MJ. Brucellosis: an overview. Emerging Infectious Disease. 1997;3:213–221. doi: 10.3201/eid0302.970219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curwin AJ, Fairn GD, McMaster CR. Phospholipid transfer protein Sec14 is required for trafficking from endosomes and regulates distinct trans-Golgi export pathways. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:7364–7375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808732200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Corno M, Michienzi A, Masotti A, Da Sacco L, Bottazzo GF, Belardelli F, Gessani S. CC chemokine ligand 2 down-modulation by selected Toll-like receptor agonist combinations contributes to T helper 1 polarization in human dendritic cells. Blood. 2009;114:796–806. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuel TF, Senior RM, Chang D, Griffin GL, Heinrikson RL, Daisser ET. Platelet factor 4 is chemotactic for neutrophils and monocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1981;78:4584–4587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornand J, Gross A, Lafont V, Liautard J, Oliaro J, Liautard JP. The innate immune response against Brucella in humans. Veterinary Microbiology. 2002;90:383–394. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorner BG, Scheffold A, Rolph MS, Huser MB, Kaufmann SHE, Radbruch A, Flesch IEA, Kroczek RA. MIP-1alpha, MIP-1 beta, RANTES, and ATAC/lymphotactin function together with IFN gamma as type 1 cytokines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:6181–6186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092141999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright FM. The pathogenesis and pathobiology of Brucella infection in domestic animals. In: Nielsen K, Duncan JR, editors. Animal brucellosis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press Inc.; 1990. pp. 301–320. [Google Scholar]

- Eskra L, Mathison A, Splitter G. Microarray analysis of mRNA levels from RAW264.7 macrophages infected with Brucella abortus. Infection and Immunity. 2003;71:1125–1133. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1125-1133.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts E, Band MR, Liu ZL, Kumar CG, Liu L, Loor JJ, Oliveira R, Lewin HA. A 7872 cDNA microarray and its use in bovine functional genomics. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2005;105:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Li Y, Hashad M, Schurr E, Gros P, Adams LG, Templeton JW. Bovine natural resistance associated macrophage protein 1 (Nramp1) gene. Genome Research. 1996;6:956–964. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.10.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández DM, Baldwin CL. Interleukin 10 down-regulates protective immunity to Brucella abortus. Infection and Immunity. 1995;63:1130–1133. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1130-1133.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Prada CM, Zelazowska EB, Nikolich M, Hadfield TL, Roop RM, II, Robertson GL, Hoover DL. Interactions between Brucella melitensis and human phagocytes: Bacterial surface O-polysaccharide inhibits phagocytosis, bacterial killing, and subsequent host cell apoptosis. Infection and Immunity. 2003;71:2110–2119. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.4.2110-2119.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay BB, Falkow S. Common themes in microbial patogenicity revisited. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 1997;61:136–169. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.136-169.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, Terraza A, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Liautard JP, Dornand J. In vitro Brucella suis infection prevents the programmed cell death of human monocytic cells. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68:342–351. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.342-351.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hams E, Colmont CS, Dioszeghy V, Hommond VJ, Fielding CA, Williams AS, Tanaka M, Miyajima A, Taylor PR, Topley N, Jones SA. Oncostatin M receptor-B signaling limits monocytic cell recruitment in acute inflammation. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181:2174–2180. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan D, Douglas SD, Lee B, Lai JP, Campbell DE, Ho WZ. Interferon gamma upregulates CCR5 expression in cord and adult blood mononuclear phagocytes. Blood. 1999;93:1137–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon BG, Templeton JW, Crawford RP, Heck FC, Williams JD, Adams LG. Macrophage function and immune response of naturally resistant and susceptible cattle to Brucella abortus. In: Skamene E, editor. Genetic control of host resistance to infection and malignancy. New York: Alan R. Liss, Inc.; 1985. pp. 345–354. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon BG, Adams LG, Templeton JW, Smith R., III Macrophage function in mammary glands of Brucella abortus-infected cows and cows that resisted infection after inoculation of Brucella abortus. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 1989;50:459–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Tan CK, Downey KM, So AG. A tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 6-inducible protein that interacts with the small subunit of DNA polymerase delta and proliferatin cell nuclear antigen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:11979–11984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221452098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Reichow S, Ramamoorthy S, Ding X, Lathigra R, Craig JC, Sobral BWS, Schurig GG, Sriranganathan N, Boyle SM. Brucella melitensis triggers time-dependent modulation of apoptosis and down-regulation of mitochondrion-associated gene expression in mouse macrophages. Infection and Immunity. 2006;74:5035–5046. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01998-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe AG, McMaster CR. Regulation of phosphatidylcholine homeostasis by Sec14. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1993;84:29–38. doi: 10.1139/Y05-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Baldwin CL. Effects of cytokines on intracellular growth of Brucella abortus. Infection and Immunity. 1993;61:124–134. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.124-134.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakar S, Watson NB, McGregor WG. RAD18 signals DNA polymerase IOTA to stalled replication forks in cells entering S-phase wiht DNA damage. In: Kang KA, Harrison DK, McGregor WG, editors. Oxigen transport to tissue. vol. 614. Springer; 2008. pp. 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapaque N, Moriyón I, Moreno E, Gorvel JP. Brucella lipopolysaccharide acts as a virulence factor. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2005;8:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using realtime quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loor JJ, Everts RE, Bionaz M, Dann HM, Morin DE, Oliveira R, Rodriguez-Zas SL, Drackley JK, Lewin HA. Nutrition-induced ketosis alters metabolic and signaling gene networks in liver of periparturient dairy cows. Physiological Genomics. 2007;32:105–116. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00188.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundin C, Schultz N, Arnaudeau C, Mohindra A, Hansen LT, Helleday T. RAD51 is involved in repair of damage associated with DNA replication in mammalian cells. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2003;328:521–535. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manetti R, Barak V, Piccinni MP, Sampognaro S, Parronchi P, Maggi E, Dinarello CA, Romagnani S. Interleukin-I favors the in vitro development of type 2 T helper (Th2) human T-cell clones. Research in Immunology. 1994;145:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(94)80019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meter RA, Wira CR, Fahey JV. Secretion of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 by human uterine epithelium directs monocyte migration in culture. Fertility and Sterility. 2005;84:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]