Abstract

Background

Abuse of children is abhorrent in Western society and, yet, is not uncommon. Nonaccidental trauma (NAT) is the result of a complex sociopathology. Not all of the causative factors of NAT are known, many are incompletely described, not all function in each case, and many are secondary to preexisting pathology in other areas.

Questions/purposes

We therefore addressed the following questions in this review: (1) what is the general incidence of NAT; (2) what factors are intrinsic to the abused child, family, and society; and (3) what orthopaedic injuries are common in NAT?

Methods

We searched Medline, Medline In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, and Embase using OVID. Only one article fit our inclusion criteria; therefore, this is a descriptive generalized review of the epidemiology of NAT.

Results

The general incidence of NAT ranges from 0.47 per 100,000 to 2000 per 100,000. Younger children are at greater risk of NAT than older children. Parents are often the perpetrators of the abuse. Rib fractures are highly indicative of NAT in young children.

Conclusions

It is important to consider child, family, and societal factors when confronted with suspicions of child abuse. Our review demonstrates the currently limited information on the true incidence of NAT. To determine a much more accurate incidence of NAT, there needs to be a population-based surveillance program conducted through primary care providers.

Introduction

Despite the abhorrence of abuse of children in Western society, it is not uncommon. The term “nonaccidental trauma” (NAT) is frequently used because of its more neutral connotations. NAT is the result of a complex sociopathology. Not all of the causative factors are known, many are incompletely described, not all function in each case, and many are secondary to preexisting pathology in other areas. There are many confounding factors in diagnosis (bias, underreporting, real and hypothetical bone fragility). The complexity of the problem defies simple deconstructive analysis.

The complexity of the problem is reflected in the heterogeneity of the literature. There is a wide range in the reported incidence of NAT, ranging from 0.47 per 100,000 to 2000 per 100,000 [2, 43]. A wide range of risk factors have been investigated, including birth order and family structure to whether the perpetrator had been abused as a child [3, 6, 14, 30, 34]. Studies reviewing orthopaedic injuries as a result of NAT are a bit more homogeneous with fractures in some bones being clearly more related to NAT than others [27, 31, 39].

This review addresses epidemiologic factors related to the maltreatment of children and focuses on physical abuse. Our goal in this review is to provide a rich descriptive background. The questions addressed in this review are: (1) what is the general incidence of NAT; (2) what risk factors are intrinsic to the abused child, family, and society; and (3) what orthopaedic injuries are common in NAT?

Materials and Methods

A search strategy was developed in consultation with a medical librarian to find epidemiologic studies of fracture in NAT (Appendix 1). The MeSH heading child abuse with the epidemiology filter as well as fracture and bone were included in the search. Key word searches included child abuse, synonyms for child abuse, orthopaedics, and fracture using appropriate wild card symbols and truncation. We searched Medline, Medline In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, and Embase using the OVID interface.

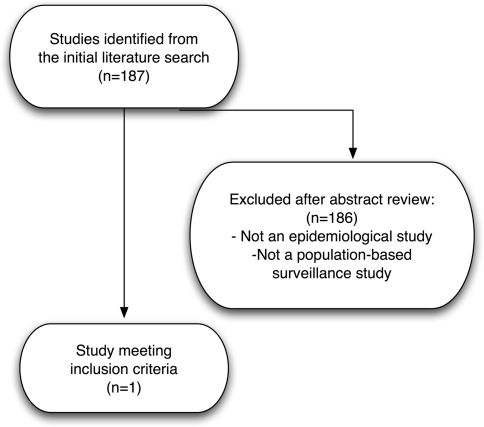

The search identified a total of 187 unique titles (Fig. 1). Abstracts of the articles were obtained and reviewed. We included a study only if it: (1) addressed the epidemiology of NAT in children; and (2) was a population-based surveillance study. One article fit these criteria [43]; therefore, it was decided to present a more generalized review of the epidemiology of NAT by exploring common themes in the abstracts returned in our literature search. Additional papers were identified through the reference lists of these papers. Ultimately, the articles included in this review were selected using expert opinion.

Fig. 1.

A flow diagram of the article selection process is shown.

The studies included in this review were performed primarily in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Two additional studies were from Canada and Finland. Study designs included retrospective (n = 21), case-control (n = 9), review article (n = 4) prospective (n = 3), cross-sectional (n = 3), other (n = 2), retrospective with a prospective component (n = 1), expert opinion (n = 1), and randomized controlled trial (n = 1).

Results

Incidence

The general incidence of NAT ranges from 0.47 per 100,000 to 2000 per 100,000 [2, 3, 9, 10, 43] (Table 1). The lowest reported incidence of 0.47 per 100,000 was from a population-based study in Wales in the 6- to 14-year-old age group [43]. The reported incidence may vary based on age group [43], the year in which the study was performed [10], and study design [3].

Table 1.

General incidence of nonaccidental trauma

| Reference | Study description | Incidence of abuse | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Altemeier et al. [2] | 1400 low-income mothers interviewed while pregnant; followed prospectively; 23 subsequently abused their children | 2000/100,000 | |

| Baldwin and Oliver [3] | Retrospective case-control and prospective case reports; 38 children from 34 families; severe abuse; retrospective 1965–1971 and prospective January 1972–June 1973 | 37/100,000 | Retrospective arm of study |

| 96/100,000 | Prospective arm of study | ||

| Cappelleri et al. [9] | Data from the Second National Incidence and Prevalence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect | 495/100,000 | |

| Creighton [10] | Retrospective review; 6532 children on abuse register 1977–1982 | 43/100,000 | In 1979 |

| 63/100,000 | In 1982 | ||

| Sibert et al. [43] | Population-based incidence | 73.4/100,000 | In babies younger than 1 year |

| Study 1996–1998; children | 9.2/100,000 | Children 1–4 | |

| younger than 14; severe abuse | 0.47/100,000 | Children 5–14 |

Risk Factors

Risk factors for NAT can be broadly categorized into: (1) risk factors intrinsic to the child; (2) risk factors intrinsic to the perpetrator of abuse; and (3) risk factors intrinsic to family structure and society.

Several studies have tried to identify risk factors that predispose a child to NAT. Gender, age, race, and the child’s health status have been investigated. There is no consensus on gender being a risk factor [3, 28, 39, 47]. However, one study did report a substantial bias toward males in a review of children who sustained fractures as a result of NAT [28]. The risk of NAT is inversely related to the age of the child with most victims being younger than 2 years of age [1, 3, 25, 43]. There are mixed results regarding whether a particular race is at greater risk for experiencing NAT [9, 24–26, 28]. Of note, black children have a greater risk of mortality from NAT [16, 34]. Children who are born prematurely or with concomitant medical conditions are at higher risk of experiencing NAT [3, 10, 22, 30, 35, 42, 44].

Major themes for developing a profile for the perpetrator of abuse are gender, relationship to the child (Table 2), age of the perpetrator (Table 3), and whether the perpetrator had been abused as a child (Table 4). The perpetrator of NAT is likely to be a young parent or primary caregiver and female. Males are more likely to be responsible for episodes of NAT resulting in death. Data regarding whether abusive parents were more likely to have been abused as children are mixed. Various other potential risk factors have also been identified (Table 5).

Table 2.

Identity of the perpetrator of abuse

| Reference | Study description | Female | Male | Both | Parent/caregiver | Other relative or parent’s boyfriend or girlfriend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldwin and Oliver [3] | Retrospective case-control and prospective case reports; 38 children from 34 families; severe abuse | 47% | 12% | 41% | ||

| Benedict et al. [6] | Retrospective case-control; mothers of 532 abused children matched for child age and gender, maternal care, and maternal education | 39% | 18% | 2.5% | 60% | 13% |

| Lightcap et al. [30] | 24 two-parent families with a documented history of abuse | 33% | 67% | |||

| Lyman et al. [34] | Retrospective review of child homicides younger than 6 years of age | 36% | 64% | 61% | 23% | |

| Perez-Arjona et al. [39] | Retrospective review of Department of Health Statistics | 75% | 11% |

Table 3.

Age of perpetrator of abuse

| Reference | Study description | Results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benedict et al. [6] | Retrospective case-control; mothers of 532 abused children matched for child age and gender, maternal care, and maternal education | Mean age of mother in abuse group 20.7 ± 4.6 versus 21.8 ± 5.6 years | Statistically significant; larger proportion of mothers in the 17–19 age group in the abuse group |

| Lauer et al. [25] | Retrospective case-control; 130 abused children | Median age of mothers in abuse group 22.5 versus 26.5 for control subjects; median age of fathers in abuse group 25.2 in abuse group versus 42% of control subjects; 21% of mothers were 19 years of age or younger versus 8% of control subjects | Difference in the parents’ age between the two groups was statistically significant |

| Lynch and Roberts [35] | Retrospective case-control 50 abused children | 50% of mothers in the abuse group were 20 years or younger at birth of her first baby versus 16% of control subjects; 20% of mothers in the abuse group were 20 years or younger at birth of the index child versus 8% of control subjects | Difference was statistically significant for age at birth of first child but not for birth of index child |

| Perez-Arjona et al. [39] | Retrospective review of Department of Health Statistics | 80% of perpetrators younger than 40 years Mean age of females: 31 years Mean age of males: 34 years | Descriptive statistics only |

| Smith and Adler [44] | Case-control; controlled for social class; 45 hospitalized abused children | Mean age of mother in abuse group 25.9 ± 7 versus 29.6 ± 6 in control subjects; Mean age of father in abuse group 28.1 ± 8 versus 32.2 ± 9 in control subjects | Both are statistically significant |

Table 4.

Abusive parents who experienced abuse as children

| Reference | Study description | Results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Altemeier et al. [2] | 1400 low-income mothers interviewed while pregnant; followed prospectively; 23 subsequently abused their children | 17% were beaten more than two times by parents; 9% saw a doctor for a beating by a parent; 43% were punished by abuse as children | No statistically significant difference between mothers who abused their children and those who did not in these areas |

| Baldwin and Oliver [3] | Retrospective case-control and prospective case reports; 38 children from 34 families; severe abuse | 41% of parents were abused as children | |

| Disbrow et al. [14] | Case-control; 37 abusive families 32 control subjects; matched for age of child, and age, education, race, and relationship status of mother | Abusive parents more likely to have been abused as children | This was a statistically significant difference Tau coefficient 0.40 |

| Egeland et al. [15] | Prospective longitudinal study of 267 primiparous women; low socioeconomic group; 161 women interviewed when her child was 48 or 54 months old | 47 of 161 mothers were abused as children; 18 of the 47 women abused their children; 12 did not and 12 were “borderline” | |

| Haapasalo and Aaltonen [21] | 25 mothers who had had contact with child protective services (CPS) and 25 who had not; matched for mothers’ and children’s ages and gender, and number of children | All mothers in CPS group reported a history of physical abuse; 23 of 25 reported a history of physical abuse in the non-CPS group | |

| Hunter et al. [23] | Prospective review of 255 premature births with abuse rate of 3.9% | 90% of the families in the abuse group had a family history of abuse or neglect compared with 17% in the no abuse group | This was a statistically significant difference |

| Smith and Adler [44] | Case-control; controlled for social class; 45 hospitalized abused children | 47% of mothers and 33% of fathers in the abuse group had a history of abuse compared with 16% and 13%, respectively in the control group | Both were statistically significant differences |

| Smith and Hanson [45] | 214 parents of battered infants and children less than 5; 53 control subjects | No difference in incidence in abuse as children |

Table 5.

Other factors that have been associated with perpetrators of nonaccidental trauma

| Increased life stressors [2, 15, 19, 44] |

| Decreased self-esteem [2] |

| Easy to anger [2] |

| Depression [15, 45] |

| Aggressive [2] |

| Punished “unfairly” as a child [2] |

| Relationships with parents more negative [2] |

| Parent was in foster care or abandoned as a child [2, 3] |

| Less likely to have a close relationship with the child’s father/other biological parent [2, 44] |

| Has lost child to foster care or avoidable death [2] |

| Unplanned pregnancy [2] |

| Unwanted pregnancy [2] |

| Engages in criminal activity/violence as an adult [3, 37] |

| Chronically ill or disabled [3] |

| Personality disorder [3, 23, 37] |

| Borderline to moderate intellectual impairment [3, 37] |

| External agency support needed [3] |

| History of suicide attempt(s) [37] |

| More likely to use physical punishment [45] |

| Parents “undervigilant” about child’s whereabouts [45] |

| Less prenatal care [6] |

| Clumsy [45] |

| Parents used significant harsh corporal punishment [36] |

| Has relationship problems with other adults [47] |

| Increased number of separations from the child in the first year [44] |

| Shorter birth intervals [6] |

| Frequent change of adults in charge of children (spouses, cohabitees, relatives, etc) [3] |

The role of family structure in NAT has also been investigated. In one study, the eldest child had the highest risk of abuse [44], whereas in another, the second child was identified as having the highest risk of abuse [3]. When the parental feelings a parent or caregiver has for a child are weak, the risk of mistreatment by that parent or caregiver is increased [12]. This has implications for stepchildren [13, 30] as well as for children with whom the natural parents do not bond [10, 33, 36, 45].

Societal factors affecting NAT include socioeconomic status and lack of community support. Socioeconomic factors are sometimes believed to play a role in the incidence of NAT. Several studies report no difference in abuse and nonabuse groups based on socioeconomic status [2, 16, 28, 44]. Isolation and lack of community support are common themes in the NAT literature (Table 6). Abuse is more common when the parent perceives there is little community support and when families feel a lack of connection to the community.

Table 6.

Social isolation and community support

| Reference | Study description | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Crittenden [11] | Case control; 121 mother-child dyads in each group; same neighborhood | No difference in size or composition of maternal social network; mothers who mistreated their children did not see others as a possible source of help; did not think they were competent to enlist help; were unable to express empathy for others; and engaged in nonreciprocal interactions aimed at coercing others to meet their needs |

| Garbarino and Crouter [19] | Retrospective case series of abusive families | Abuse correlates with family mobility and stability of the neighborhood |

| Garbarino and Kostelny [20] | 77 communities in the Chicago area; socioeconomically similar | In poor communities where the attitude toward the community was negative, abuse rates were high; in poor communities where the attitude toward the community was positive, abuse rates were low |

| Hunter and Kilstrom [22] | Case control; premature infants admitted to an intensive care unit; history of abuse in parents in 49/255 | Nongeneration-repeating families had a richer network of social connections |

| Lauer et al. [25] | Retrospective case-control of 130 abused children; 130 control subjects | 66% of families had lived at their current address less than 10 months; only 5% had kept their location unchanged for 30 months or longer |

| Polansky et al. [40] | Retrospective case-control; 152 “neglectful” mothers and 154 control subjects in the same neighborhood | “Neglectful” mothers viewed neighborhood as less friendly and helpful |

Orthopaedic Injuries in NAT

Orthopaedic injuries are a common feature of NAT. One study using data from the Kids’ Inpatient Database found 12.08% of children hospitalized with fractures sustained those fractures as a result of NAT [27]. NAT was second only to falls as the cause of fractures requiring hospitalization. Fractures in young children should raise suspicion for NAT (Table 7). Twenty-five percent of children who were hospitalized with a fracture in the first year of life were abused.

Table 7.

Age of children sustaining fractures as a result of NAT

| Reference | Study description | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Leventhal et al. [28] | Incidence of fractures in hospitalized children resulting from abuse; used Kids’ Inpatient Database | Incidence of fractures caused by NAT by age group: age 11 months or younger: 36.1 per 100,000 age 12–23 months: 4.8 per 100,000 age 24–35 months: 4.8 per 100,000 |

| Pandya et al. [38] | Analysis of trauma at a Level I pediatric trauma Center | Mean age of child presenting with orthopaedic injuries as a result of NAT was 11.8 months |

| Sibert et al. [43] | Population based incidence study | Incidence of fractures caused by NAT by age group: age 0–5 months: 56.8 per 100,000 age 6–11 months: 39.8 per 100,000 age 60–119 months: 0 |

| Worlock et al. [47] | Retrospective case control | 80% of children presenting with fractures as a result of NAT were younger |

| Than 18 months old |

Fractures in certain bones and specific fracture types are more common in NAT than in accidental injury (Table 8). In a retrospective review of all children younger than age 3 with rib fractures within a 6-year period, the positive predictive value of a rib fracture as an NAT was 95% [5]. In 29% of these children, rib fractures were the only orthopaedic injury caused by NAT. The number of fractures may provide a clue toward whether the injury was nonaccidental. In a series of 35 children with fractures sustained as a result of NAT, 54% of the children had a history of three or more fractures [47]. In the group of 116 control subjects, no child had more than two fractures; 84% of the children had only one fracture.

Table 8.

Fracture sites in nonaccidental trauma (NAT)

| Reference | Study description | Age of patients | Fracture site | Caused by NAT (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulloch et al. [7] | Case series of 39 subjects; 1994–1997 | 1 year | Ribs | 82% | |

| Leventhal et al. [27] | Incidence of fractures in hospitalized children resulting from abuse; used Kids’ Inpatient Database | < 36 months | Ribs | 61.4% | |

| Tibia/fibula | 31.1% | ||||

| Radius/ulna | 29.8% | ||||

| Clavicle | 20.7% | ||||

| Skull | 12.1% | ||||

| Femur | 11.7% | ||||

| Humerus | 9.3% | ||||

| Loder and Bookout [31] | Case study of 154 fractures in 75 children reported to child protective services 1987–1988 | < 7 years | Skull | ||

| Rib | |||||

| Long bones | |||||

| “Corner” fractures | |||||

| Loder et al. [32] | Case series based on 2000 Health Care Cost and Utilization Project | < 2 years | Femur | 15% | n = 1076 femur fractures |

| Pandya et al. [38] | Analysis of trauma at a Level I pediatric trauma Center | Non-bony head injury | 5 most common injuries in NAT | ||

| Rib fracture | |||||

| Tibia/fibula fracture | |||||

| Radius/ulna fracture | |||||

| Clavicle fracture | |||||

| Scherl et al. [41] | Retrospective review of 214 femur fractures | < 6 years | Femur | 8% | No difference in the number of spiral and transverse fractures in abuse group |

Discussion

NAT is the result of a complex sociopathology. There is a lack of true epidemiologic studies of fracture sustained as a result of NAT. As a result of the heterogeneity of the literature, we identified common themes present in the NAT literature and touched on the wide range of research that has been undertaken. This review sought to address three topics: (1) the incidence of NAT; (2) risk factors for NAT; and (3) orthopaedic injuries in NAT.

There are limitations inherent in NAT research. First, there may be challenges around collecting data and conducting research in NAT as a result of privacy laws and fear of litigation. Second, each of the risk factor analyses in any given paper is subject to bias. It is important to take into account the study’s sample size and the possibility of type II error.

Our literature review was also limited in several ways. First, we were limited in our ability to conduct a systematic review of true epidemiologic studies of NAT because only one population-based surveillance study was found in our literature search that fit our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Therefore, we proceeded with a descriptive article. The strict inclusion criteria for study design were set because a population-based surveillance program is the purest way to conduct an epidemiologic study. Second is the heterogeneous nature of those papers selected for inclusion. Definitions of NAT varied; some studies looked only at severe trauma or death, whereas others combined physical abuse with other types of abuse or confirmed cases of physical abuse with suspected cases of physical abuse. Third, various study designs were used, including retrospective chart reviews, database searches, case-controls, matched cohort studies, and prospective designs. Data from retrospective studies and databases may have over- or underestimated the true incidence of NAT. Fourth, although heterogeneous in many respects, the papers were also somewhat homogeneous with regard to the countries in which they were performed. Almost all studies were performed in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Butchart noted “almost all scientifically robust epidemiological studies of child mal treatment…have been conducted in high income countries,” which in and of itself can be a confounding factor [8].

There is little information on the true incidence of NAT. Although general statistics can give a clear picture of those cases correctly diagnosed as NAT, they omit “near misses” and cases that are misdiagnosed or are not reported [4, 46]. One study has also suggested there is a bias toward referring minority children for bone scans to investigate other injuries and to child protective services [24]. Reports of incidence may also be impacted by children who experience recurring episodes of NAT. The reported risk of recurrence ranges from 9.3% to 43.8% [17, 18, 25, 29]. To determine a much more accurate incidence of NAT, there needs to be a population-based surveillance program conducted through primary care providers, similar to the study conducted in Wales [43]. Every child would need to be seen and assessed every 6 months until age 5 [43]. The assessment would include a detailed examination for evidence of abuse and determination of the risk factors for abuse present in the child’s life. Implementing a large population-based surveillance program would have several challenges, including recruitment, compliance with followup, and the cost of running such a program. Despite these challenges, this type of study would provide the most accurate incidence of NAT because the number of NAT cases reported or diagnosed in the hospital setting is likely to be just the tip of the iceberg.

The results of this review highlight the complex nature of NAT. It is important to consider child, family, and societal risk factors when confronted with cases suspicious for NAT. A high index of suspicion should be maintained in cases in which the patients are young (eg, younger than 2 years of age) or have comorbid medical conditions. The perpetrator of NAT is often a young female parent or primary caregiver who has decreased feelings of attachment to the child and may feel isolated from the community or a lack of support.

When evaluating a patient with fractures, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion when the patient is a young child with a fracture or has a history of multiple fractures. Rib fractures and “corner” fractures are particularly associated with NAT. Long bones are also commonly fractured in NAT.

Our review highlights the limited information available on the true incidence of NAT. It is likely that the incidence reported in the literature is lower than the true incidence of NAT. It is important for healthcare providers to maintain a high index of suspicion for NAT, particularly in young children, and to consider child, familial, and societal risk factors when confronted with suspicions of child abuse.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr Ranjit Varghese for his editing assistance.

Appendix 1. Search strategy

exp Child Abuse/ep [Epidemiology]

(child abuse or non-accident* injur* or battered child*).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier]

(epidemiol* or incidence or population).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier]

2 and 3

exp Fractures, Bone/

orthop?ed*.mp.

fracture*.mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier]

4 or 1

5 or 6 or 7

8 and 9

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

This work was performed at British Columbia Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

References

- 1.Agran PF, Anderson C, Winn D, Trent R, Walton-Haynes L. Rates of pediatric injuries by 3-month intervals for children 0–3 years of age. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e683–e692. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.e683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altemeier WA, O’Connor S, Vietze PM, Sandler HM, Sherrod KB. Antecedents of child abuse. J Pediatr. 1982;100:823–829. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(82)80604-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldwin JA, Oliver JE. Epidemiology and family characteristics of severely-abused children. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1975;29:205–221. doi: 10.1136/jech.29.4.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banaszkiewicz PA, Scotland TR, Myerscough EJ. Fractures in children younger than age 1 year: importance of collaboration with child protection services. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:740–744. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barsness KA, Cha E-S, Bensard DD, Calkins CM, Partrick DA, Karrer FM, Strain JD. The positive predictive value of rib fractures as an indicator of nonaccidental trauma in children. J Trauma. 2003;54:1107–1110. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000068992.01030.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benedict MI, White RB, Cornley DA. Maternal perinatal risk factors and child abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1985;9:217–224. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bulloch B, Schubert CJ, Brophy PD, Johnson N, Reed MH. Cause and clinical characteristics of rib fractures in infants. Pediatrics. 2000;105:e48. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butchart A. The major missing element in the global response to child maltreatment? Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:S103–S105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cappelleri JC, Eckenrode J, Powers JL. The epidemiology of child abuse: findings from the Second National Incidence and Prevalence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1622–1624. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.83.11.1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creighton SJ. An epidemiological study of abused children and their families in the United Kingdom between 1977 and 1982. Child Abuse Negl. 1985;9:441–448. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crittenden PM. Social networks, quality of childrearing, and child development. Child Dev. 1985;56:1299–1313. doi: 10.2307/1130245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daly M, Wilson M. Discriminative parental solicitude: a biological perspective. J Marriage Fam. 1980;42:277–288. doi: 10.2307/351225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daly M, Wilson M. An assessment of some proposed exceptions to the phenomenon of nepotistic discrimination against stepchildren. Ann Zool Fenn. 2001;38:287–296. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Disbrow MA, Doerr H, Caulfield C. Measuring the components of parents’ potential for child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 1977;1:279–296. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(77)90003-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egeland B, Jacobvitz D, Sroufe LA. Breaking the cycle of abuse. Child Dev. 1988;59:1080–1088. doi: 10.2307/1130274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falcone RA, Brown RL, Garcia VF. The epidemiology of infant injuries and alarming health disparities. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fluke JD, Yuan Y-YT, Edwards M. Recurrence of maltreatment: an application of the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23:633–650. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fryer GE, Miyoshi TJ. A survival analysis of the revictimization of children: the case of Colorado. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18:1036–1071. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garbarino J, Crouter A. Defining the community context for parent-child relations: the correlates of child maltreatment. Child Dev. 1978;49:604–616. doi: 10.2307/1128227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garbarino J, Kostelny K. Child maltreatment as a community problem. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;16:455–464. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90062-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haapasalo J, Aaltonen T. Mothers’ abusive childhood predicts child abuse. Child Abuse Rev. 1999;8:231–250. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0852(199907/08)8:4<231::AID-CAR547>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter RS, Kilstrom N. Breaking the cycle in abusive families. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136:1320–1322. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.10.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter RS, Kilstrom N, Kraybill EN, Loda F. Antecedents of child abuse and neglect in premature infants; a prospective study in a newborn intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 1978;61:629–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lane WG, Rubin DM, Monteith R, Christian CW. Racial differences in the evaluation of pediatric fractures for physical abuse. JAMA. 2002;288:1603–1609. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.13.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lauer B, Ten Broeck E, Grossman M. Battered child syndrome: review of 130 patients with controls. Pediatrics. 1974;54:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leventhal JM, Larson IA, Abdoo D, Singaracharlu S, Takizawa C, Miller C, Goodman TR, Schwartz D, Grasso S, Ellingson K. Are abusive fractures in young children becoming less common? Changes over 24 years. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leventhal JM, Martin KD, Asnes AG. Incidence of fractures attributable to abuse in young hospitalized children: results from analysis of a United States database. Pediatrics. 2008;122:599–604. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leventhal JM, Thomas SA, Rosenfield NS, Markowitz RI. Fractures in young children: distinguishing child abuse from unintentional injuries. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:87–92. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160250089028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy HB, Markovic J, Chaudhry U, Ahart S, Torres H. Reabuse rates in a sample of children followed for 5 years after discharge from a child abuse inpatient assessment program. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19:1363–1377. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00095-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lightcap JL, Jurland JA, Burgess RL. Child abuse: a test of some predictions from evolutionary theory. Ethol Sociobiol. 1982;3:61–67. doi: 10.1016/0162-3095(82)90001-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loder RT, Bookout C. Fracture patterns in battered children. J Orthop Trauma. 1991;5:428–433. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loder RT, O’Donnell PW, Feinberg JR. Epidemiology and mechanisms of femur fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:561–566. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000230335.19029.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lozoff B, Brittenham GM, Trause MA, Kennell JH, Llaus MH. The mother-newborn relationship: limits of adaptability. J Pediatr. 1977;91:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(77)80433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyman JM, McGwin G, Malone DE, Taylor AJ, Brissie RM, Davis G, Rue LW. Epidemiology of child homicide in Jefferson County, Alabama. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1063–1073. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynch MA, Roberts J. Predicting child abuse: signs of bonding failure in the maternity hospital. BMJ. 1977;1:624–626. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6061.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muller RT, Hunter JE, Stollak G. The intergenerational transmission of corporal punishment: a comparison of social learning and temperament models. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19:1323–1335. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00103-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliver JE. Successive generations of child maltreatment: social and medical disorders in the parents. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:484–490. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pandya NK, Baldwin K, Wolfgruber H, Christian CW, Drummond DS, Hosalkar HS. Child abuse and orthopaedic injury patterns; analysis at a level I pediatric trauma center. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:618–628. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181b2b3ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perez-Arjona E, Dujovny M, Vinas F, Park HK, Lizarraga S, Park T, Diaz FG. CNS child abuse: epidemiology and prevention. Neurol Res. 2002;24:29–40. doi: 10.1179/016164102101199512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polansky NA, Gaudin JM, Ammons PW, Davis KB. The psychological ecology of the neglectful mother. Child Abuse Negl. 1985;9:265–275. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scherl SA, Miller L, Lively N, Russinoff S, Sullivan CM, Tornetta P. Accidental and nonaccidental femur fractures in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;376:96–105. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200007000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sherrod KB, O’Connor S, Vietze PM, Altemeier WA. Child health and maltreatment. Child Dev. 1984;55:1174–1183. doi: 10.2307/1129986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sibert JR, Payne EH, Kemp AM, Barber M, Rolfe K, Morgan RJH, Lyons RA, Butler I. The incidence of severe physical child abuse in Wales. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26:267–276. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith JAS, Adler RG. Children hospitalized with child abuse and neglect: a case control study. Child Abuse Negl. 1991;15:437–445. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(91)90027-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith S, Hanson R. Interpersonal relationships and child-rearing practices in 214 parents of battered children. Br J Psychiatry. 1975;127:513–525. doi: 10.1192/bjp.127.6.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taitz J, Moran K, O’Meara M. Long bone fractures in children under 3 years of age: is abuse being missed in emergency department presentations? J Paediatr Child Health. 2004;40:170–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Worlock P, Stower M, Barbor P. Patterns of fractures in accidental and non-accidental injury in children: a comparative study. BMJ. 1986;293:100–102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6539.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]