Abstract

Background

Existing studies suggest a relatively high incidence of dysphagia after anterior cervical decompression and fusion (ACDF). The majority of these studies, however, are retrospective in nature and lack a control group.

Questions/purposes

We therefore (1) prospectively determined the incidence and severity of dysphagia after ACDF using lumbar decompression patients as a control group; and (2) determined which factors, if any, are associated with increased postoperative dysphagia.

Methods

Patients undergoing either one- or two-level ACDF (n = 38) or posterior lumbar decompression (n = 56) were prospectively followed. Baseline patient characteristics were recorded. A dysphagia questionnaire was administered preoperatively and during the 2-week, 6-week, and 12-week postoperative visits. We found no differences in patient age, body mass index, or the preoperative incidence and severity of dysphagia between the cervical and lumbar groups. We compared the incidence and severity of dysphagia between the patients who had cervical and lumbar surgery.

Results

Postoperatively, 71% of patients having cervical spine surgery reported dysphagia at 2 weeks followup. This incidence decreased to 8% at 12 weeks followup. The incidence and severity of dysphagia were greater in the cervical group at 2 and 6 weeks followup with a trend toward greater dysphagia at 12 weeks followup. Body mass index, gender, location of surgery, and the number of surgical levels were not related to the risk of developing dysphagia. We observed a correlation between operative time and the severity of postoperative dysphagia.

Conclusions

Dysphagia is common after ACDF. The incidence and severity of postoperative dysphagia decreases over time, although symptoms may persist at least 12 weeks after surgery.

Level of Evidence

Level II, prospective, comparative study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

The Smith Robinson approach to anterior cervical surgery was described over 50 years ago [26]. This approach is still commonly used to perform a variety of anterior cervical procedures that address symptomatic cervical disc herniation and cervical spondylosis, including anterior discectomy and fusion, anterior corpectomy and fusion, and, more recently, cervical disc replacement surgery. Generally speaking, these procedures provide return to function and pain relief and a low incidence of major complications [1, 10, 14, 19, 21, 22, 25, 26]. The most common patient complaint after this procedure is dysphagia; the reported incidence of which is up to 69% in the early postoperative period [12, 29, 30]. The proposed causes of postoperative dysphagia include recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, esophageal ischemia and reperfusion injury, and local soft tissue swelling. Risk factors for developing postoperative dysphagia are debated in the literature. Several studies have suggested that deflating and reinflating the endotracheal cuff after placement of retractors, minimizing endotracheal cuff pressure, and minimizing the duration and pressure of intraoperative retraction may decrease the incidence of postoperative dysphagia [2, 13, 16, 24]. Other studies suggest, however, that these interventions have no effect on postoperative dysphagia [3, 23]. Various intraoperative and patient factors (ie, age, gender, body mass index, operative time, estimated blood loss, number of levels of surgery, location of surgery, and plate thickness) have been investigated as potential risk factors for postoperative dysphagia with inconsistent findings [4, 7, 17, 18, 23, 27, 29]. Fortunately, postoperative dysphagia is typically a transient phenomenon. Persistent, debilitating dysphagia is relatively uncommon [4, 29].

Many of the existing studies that have evaluated the incidence and severity of dysphagia after anterior cervical surgery are retrospective in nature [5, 7, 8, 10, 15, 19, 20, 28, 31–33]. Edwards et al. [9] showed the incidence and severity of dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery was underreported by physicians in the medical chart. Recent prospective studies show postoperative dysphagia is a more common problem than previously reported [4, 7, 12, 23, 24, 27]. The only prospective study on postoperative dysphagia that includes comparison with a lumbar control group is that by Smith-Hammond et al. [27], a study limited by the fact that only 17 of 38 (45%) patients having anterior cervical spine surgery in the study were seen for a followup visit beyond the initial postoperative evaluation, which occurred an average of 2 days postoperatively.

We therefore (1) prospectively determined the incidence and severity of dysphagia after anterior cervical decompression and fusion (ACDF) using lumbar decompression patients as a control group; and (2) determined which factors, if any, are associated with increased postoperative dysphagia.

Patients and Methods

We prospectively enrolled 94 patients undergoing one of two types of surgery from April 2008 to July 2008: (1) 38 undergoing one- or two-level anterior cervical decompression (ie, either two-level discectomy or one-level corpectomy) and fusion; and (2) 56 undergoing posterior lumbar decompression (ie, discectomy or laminectomy) or placement of an interspinous spacer for degenerative disease. The indications for cervical surgery were one- or two-level cervical spondylosis and/or disc herniation with radiculopathy that was unresponsive to conservative treatment. The indications for lumbar surgery were single or multilevel lumbar stenosis and/or disc herniation with radiculopathy and/or neurogenic claudication that was unresponsive to conservative treatment. We excluded from the study patients who had prior anterior cervical surgery, who underwent greater than two-level cervical surgery, or who underwent surgery for an etiology other than degenerative disease (ie, trauma, infection, and tumor) from this study. There were 46 male and 48 female study patients with an average age of 49 years (range, 20–82 years). There were no differences between the patients having cervical and lumbar surgery in regard to age (p = 0.73), body mass index (BMI) (p = 0.22), or preoperative incidence (p = 0.40) or severity (p = 0.20) of dysphagia (Table 1). There was a higher percentage of female patients in the cervical group compared with the lumbar group (p = 0.001). Before patient enrollment, approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board. We obtained informed consent to participate in the study from all study patients.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Cervical | Lumbar | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, range) | 48.4 (31–82) | 49.3 (20–82) | 0.73 |

| Gender (percent female) | 71 | 38 | 0.001 |

| Body mass index (range) | 29.8 (20.3–54.2) | 28.0 (18.8–39.2) | 0.22 |

| Operative time (minutes, range) | 107 (69–224) | 87 (39–190) | 0.002 |

| Preoperative dysphagia numeric rating score | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.20 |

| Frequency of preoperative dysphagia | 0/38 (0%) | 1/56 (1.8%) | 0.40 |

During a preoperative visit we asked patients to complete a demographic and medical history questionnaire and a dysphagia survey. The survey consisted of a dysphagia numeric rating scale (range, 0–10) and a dysphagia questionnaire [4]. The answers to the questions comprising the dysphagia survey were used to score the degree of dysphagia as none, mild, moderate, or severe according to a previously published dysphagia scoring system [4]. This scoring system inquires about the frequency with which the patient has difficulty swallowing liquids and/or solids with an increased severity of dysphagia assigned to patients with more frequent episodes of dysphagia and episodes of dysphagia that involve liquids [4]. We recorded the type of surgical procedure and the length of the procedure.

All surgeries were performed at a single institution. All patients in the cervical group underwent a left-sided anterior approach through a transverse incision and had fusion surgery performed with the use of structural allograft bone and anterior plate and screw fixation. The type of plate was not standardized for this study and varied depending on surgeon preference. No patients received recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 or any other bone graft supplement or substitute. Self-retaining retractors were used for all cervical procedures. The endotracheal cuff was not deflated then reinflated after retractor placement. The average operative time was greater (p = 0.002) in the cervical group (Table 1). Of the patients undergoing anterior cervical surgery, 16 (42%) had one-level surgery and 22 (58%) had two-level surgery. Fourteen (37%) patients having cervical spine surgery had surgery performed at or above the C4-C5 level and 24 (63%) had surgery performed below the C4-C5 level.

Postoperatively, a deep drain was used in the cervical spine patients. The drain was discontinued on postoperative Day 1 or when the drain output was less than 30 mL per 8-hour shift. Patients having lumbar spine surgery did not receive a drain. Patients having either cervical or lumbar spine surgery were discharged from the hospital to home on postoperative Day 1 or 2. The use of postoperative orthoses and a postoperative rehabilitation program was not standardized and was at the discretion of the treating surgeon.

The dysphagia survey was repeated at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks postoperatively during regularly scheduled followup appointments. Four of 94, 10 of 94, and 15 of 94 patients who were not present for the regularly scheduled 2-week, 6-week, and 12-week followup appointment(s), respectively, completed the survey through a telephone interview. At all time points, the survey was administered by a spine research fellow (JK) who was not directly involved with the clinical care of the study patients.

A prior power analysis was performed assuming alpha of 0.5 and power of 80% (standard). An effect size of 0.49 was calculated assuming that a difference in the mean dysphagia numeric rating score between the cervical and lumbar groups of 2.0 is clinically important (range, 0–10). This represents a 20% difference in dysphagia between groups. The SD used for both the cervical and lumbar groups when calculating effect size was 1.8. Because prior studies have not reported dysphagia using a 0 to 10 scale, this SD was derived from prior publications that use a similar 0 to 10 visual analog scale to report neck pain [6, 11]. Based on this power analysis, 14 patients would be required in each group.

Descriptive statistics were calculated, including frequencies for categorical and variables and means, SDs, and ranges for continuous variables. We used the Student’s t-test and chi square test to determine differences in the severity and incidence of postoperative dysphagia between the cervical and lumbar groups. Repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to determine the differences in the severity of dysphagia from baseline within each group at each followup time period. Patients in the cervical group were subdivided according to the location of surgery (ie, C4-C5 or higher versus C5-C6 or below) and the number of levels of surgery (ie, those with one-level surgery versus those with two-level surgery). The difference in the severity and incidence of postoperative dysphagia between these subgroups was determined using the Student’s t-test and chi square test. We performed additional statistical analysis to determine associations among age, BMI, gender, operating room time, and the swallowing score. For the categorical variable gender, we performed T statistics to determine if there was a difference in the average swallowing scores across the males and females. Similarly, we performed T statistics to determine if there was difference in the average age, BMI, and operating room time between those patients with and those patients without postoperative dysphagia at each followup time period. Chi square analysis was performed for the categorical variables gender and the presence of postoperative dysphagia. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 12.0.1 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

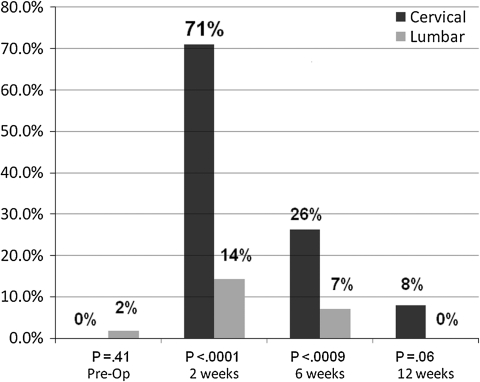

At the 2-week followup period, 71% of the patients having cervical spine surgery reported some degree of dysphagia according to the Bazaz dysphagia scoring system [4] (Fig. 1). This decreased to 8% at the 12-week followup period (Fig. 1). A greater incidence of dysphagia was observed in the cervical compared with the lumbar group at the 2-week (71% versus 14%, p < 0.001) and 6-week (26% versus 7%, p < 0.001) time periods (Fig. 1). A greater percentage (p < 0.001) of patients with cervical spine surgery had moderate to severe dysphagia at the 2-week time period than did patients with lumbar spine surgery: 61% versus 11%, respectively (Table 2). A similar trend was observed when comparing the severity of postoperative dysphagia between groups as measured by the dysphagia numeric rating score (Table 3). Patients having cervical spine surgery experienced an increase in the dysphagia numeric rating score at the 2-week and 6-week postoperative time periods (p < 0.001) when compared with preoperative scores and a trend toward an increased dysphagia score at 12 weeks (p = 0.06). Patients having lumbar spine surgery had no increase in the dysphagia numeric rating score when compared with the preoperative score at any of the followup time periods.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the overall incidence of dysphagia between the cervical and lumbar groups preoperatively and at each of the follow-up time periods (ie, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks).

Table 2.

Comparison of the incidence and severity of dysphagia between cervical and lumbar groups

| Timeframe | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical | Lumbar | Cervical | Lumbar | Cervical | Lumbar | Cervical | Lumbar | ||

| Preoperative | 100.0% | 94.6% | 0.0% | 5.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.408 |

| 2 weeks | 28.9% | 85.7% | 10.5% | 3.6% | 39.5% | 8.9% | 21.1% | 1.8% | < 0.0001 |

| 6 weeks | 73.7% | 92.9% | 10.5% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 7.1% | 13.2% | 0.0% | 0.0009 |

| 12 weeks | 92.1% | 100.0% | 5.3% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.06 |

Table 3.

Comparison of the dysphagia numeric rating score between cervical and lumbar patients

| Timeframe | Cervical | Lumbar | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.28 |

| 2 weeks | 3.24 | 0.37 | < 0.0001 |

| 6 weeks | 1.32 | 0 | < 0.0001 |

| 12 weeks | 0.26 | 0 | 0.05 |

There were no differences at any of the followup time periods in the incidence or severity of dysphagia when comparing patients with two-level cervical surgery and one-level cervical surgery (Tables 4, 5). Similarly, there were no differences when comparing patients whose location of surgery was at higher level(s) (ie, C4-C5 or above) with those who had surgery on lower level(s) (ie, C5-C6 or below) (Tables 5, 6). Patients with postoperative dysphagia had a statistically similar age, gender, BMI, and operative time when compared with those without postoperative dysphagia at all followup time periods with the exception of an increase operative time in those patients who had dysphagia at the 12-week followup time period (p = 0.04) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Comparison of dysphagia numeric rating score according to number of surgical levels

| Timeframe | One-level (n = 16) | Two-level (n = 22) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | 2.5 | 3.8 | 0.20 |

| 6 weeks | 1.1 | 1.5 | 0.45 |

| 12 weeks | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.19 |

Table 5.

Comparison of age, gender, body mass index, and operative time in those with and without dysphagia at 2-, 6-, and 12-week followup

| Timeframe | Postoperative dysphagia | Age (years) | Percent female | BMI (kg/m2) | Operative time (minutes) | Percent at or above C4 | Percent 1-level surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | Yes (n = 27) | 48.1 | 70.4% | 28.7 | 107.1 | 37.0% | 37.0% |

| No (n = 11) | 49.1 | 72.7% | 32.6 | 107.7 | 36.4% | 54.5% | |

| p Value | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.28 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.32 | |

| 6 weeks | |||||||

| Yes (n = 10) | 46.4 | 80.0% | 29.8 | 112.6 | 20.0% | 50.0% | |

| No (n = 28) | 49.1 | 67.9% | 29.8 | 105.2 | 42.9% | 39.3% | |

| p Value | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.56 | |

| 12 weeks | |||||||

| Yes (n = 3) | 43.0 | 66.7% | 32.8 | 135.3 | 0.0% | 33.3% | |

| No (n = 35) | 48.8 | 71.4% | 29.6 | 104.7 | 40.0% | 42.9% | |

| p Value | 0.38 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.75 | |

BMI = body mass index.

Table 6.

Comparison of dysphagia numeric rating score according to location of cervical surgery

| Timeframe | C4-C5 or above (n = 14) | Below C4-C5 (n = 24) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | 2.4 | 3.8 | 0.17 |

| 6 weeks | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.07 |

| 12 weeks | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.26 |

Discussion

The incidence of postoperative dysphagia after ACDF varies widely in previous studies, ranging from 5% to 69% [4, 7, 9, 12, 20, 27, 30–32] (Table 7). This disparity is likely related to variations in study design and in the definition and measurement of dysphagia. Many of the existing studies of postoperative dysphagia are retrospective in nature and draw conclusions based on data that exist in the medical chart. A recent study [9] showed that postoperative dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery was underreported by physicians in the medical chart. We therefore (1) prospectively determined the incidence and severity of dysphagia after ACDF using lumbar decompression patients as a control group; and (2) determined which factors, if any, are associated with increased postoperative dysphagia. [4, 7, 9, 12, 20, 27, 30–32].

Table 7.

Reported incidence of dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery

| Study | Prospective versus retrospective | Number of subjects | Followup | Control group | Percent postoperative dysphagia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current study | Prospective | 38 | 12 weeks | Yes | 70% |

| Lunsford et al. [19] | Retrospective | 253 | 7 years | No | 5% |

| Stewart et al. [28] | Retrospective | 73 | 22 months | No | 45% |

| Bose [5] | Retrospective | 97 | N/A | No | 5.1% |

| Daniels et al. [8] | Retrospective | 2 | N/A | No | N/A |

| Winslow et al. [31] | Retrospective | 497 | 3.3 years | No | 60% |

| Frempong-Boadu et al. [12] | Prospective | 23 | 1 month | No | 67% |

| Bazaz et al. [4] | Prospective | 249 | 12 months | No | 50.2% |

| Ratnaraj et al. [24] | Prospective | 50 | 1 week | No | 52% |

| Edwards et al. [9] | Retrospective | 166 | 6 months | No | 57% |

| Smith-Hammond et al. [27] | Prospective | 38 | 3 years | Yes | 47% |

| Yue et al. [32] | Retrospective | 74 | 11 years | No | 35.1% |

| Papavero et al. [23] | Prospective | 92 | 5 days | Yes* | 49.3% |

| Chin et al. [7] | Prospective | 64 | 1 month | No | 17.2% |

| Tervonen et al. [29] | Prospective | 102 | 6.1 months | Yes† | 69% |

* Control group described in methods section but not reported in results; †control group of patients never intubated previously, no surgical control group, no followup on controls; N/A = not available.

Our study had several limitations. First, we had no objective measurements of dysphagia. Although videofluoroscopic swallow evaluation (VSE) is often considered the “gold standard” in the evaluation of swallowing function, such objective measures of dysphagia are extremely sensitive in patients undergoing anterior cervical surgery. In 2002, Frempong-Boadu et al. [12] performed a prospective study of the incidence of dysphagia in anterior cervical surgery patients, performing VSE on the patients before and after surgery. These authors found 48% of patients had objective evidence of dysphagia on VSE preoperatively. None of these patients, however, had preoperative subjective complaints of swallowing difficulty. Although objective evaluation of dysphagia provides important information, patient-reported measures of dysphagia may be more clinically relevant. Second, there were differences between groups at baseline that may have affected the results of this study, including gender, operative time, and positioning of the patient (ie, prone versus supine). These differences are reflective of the patient population and nature of surgery of each group. Ideally, a control group with similar positioning and operative time would be used to control for operative variables. Third, our data in this study may not be applicable to patients undergoing anterior cervical surgery on greater than two levels, revision anterior cervical surgery, or anterior cervical surgery for etiologies other than degenerative disease such as trauma, infection, or tumor. We focused on the most common anterior cervical procedures performed. Inclusion of less commonly performed procedures and indications for surgery would have likely led to the enrollment of small numbers of patients within these subgroups, data from which would be difficult to interpret. Fourth, the outcome measures that we used to measure the incidence and severity of postoperative dysphagia (ie, the Bazaz score [4] and dysphagia numeric rating score) are not validated measures. It should be noted that the Bazaz scores seem more severe than the dysphagia numeric rating score in the cervical group. For example, the mean dysphagia numeric rating score is 3.24 in the cervical group at 2 weeks followup, whereas 61% of patients having cervical spine surgery have moderate to severe dysphagia at 2 weeks according to the Bazaz score. This disparity is reflective of the lack of validation of these two measures. The Bazaz score [4] is, however, the most widely used dysphagia measurement tool used to study postoperative dysphagia in anterior cervical surgery, and therefore its use in this study allows for the comparison of the results to the results of prior studies. Finally, this study has relatively short-term followup. Although the nature of dysphagia is most commonly a transient finding in the early postoperative period, there is a minority of patients who develop long-term issues with swallowing. It will be important to follow this patient population to gain a better understanding of the long-term effects of anterior cervical surgery on swallowing.

We found a relatively high incidence and severity of dysphagia in the early postoperative period after ACDF. The differences noted between the study and control groups suggest postoperative dysphagia is the result of the anterior cervical surgery itself rather than potential confounding factors such as general anesthesia or endotracheal intubation. The incidence of dysphagia in the early postoperative period after anterior cervical surgery in previous prospective analyses ranges from 30% to 50% [4, 7, 12, 23, 24, 27]. Bazaz et al. [4] performed a prospective study on 221 patients on dysphagia after anterior cervical surgery. These authors reported an overall incidence of postoperative dysphagia of 50% at 1 month, 32% at 2 months, and 18% at 6 months. The incidence of moderate to severe dysphagia at 6 months was 5%. Papavero et al. [23] reported a 49% incidence of postoperative dysphagia after anterior cervical surgery. This study only included followup data out to the fifth postoperative day. Chin et al. [7] prospectively studied the effect of plate thickness on postoperative dysphagia after anterior cervical fusion surgery. Patients with a plate that did not protrude past the anterior margin of the preoperative anterior osteophytes had a 30% incidence of dysphagia lasting a mean of 38 days compared with a 38% incidence of dysphagia lasting a mean of 76 days in patients in whom the plate extended past the anterior margin of preoperative anterior osteophytes. The only existing prospective, controlled analysis of postoperative dysphagia is that by Smith-Hammond et al. [27], who compared patients undergoing ACDF with those undergoing either posterior cervical or posterior lumbar surgery. These authors reported that 47% of patients having anterior cervical spine surgery had evidence of dysphagia on postoperative VSE. The dysphagia in 70% of these patients resolved within 2 months from surgery, whereas 23% had some degree of dysphagia that persisted for up to 10 months. In a large prospective study of 310 patients undergoing anterior cervical surgery with 2-year followup, Lee et al. [18] reported a 54% incidence of dysphagia at 1 month, an 18.6% incidence of dysphagia at 6 months, and a 13.6% incidence of dysphagia at 2 years postoperatively. We found a higher incidence of postoperative dysphagia in the early postoperative period than previously reported with 71% of patients demonstrating dysphagia at 2 weeks followup. The postoperative dysphagia was, however, relatively transient compared with previous reports with only 8% of patients demonstrating dysphagia at 12 weeks followup.

We did not find that the location of cervical surgery (ie, high versus low) or the level of surgery (ie, one versus two) affected the risk of developing postoperative dysphagia. It should be noted, however, that the subgroup analysis within the cervical surgery patients (ie, location and number of levels of surgery) resulted in relatively small group sizes (Tables 4, 6). Therefore, it is possible that there was not adequate power to show differences that may exist between these subgroups. These findings are consistent with the findings of Smith-Hammond et al. [27] and Chin et al. [7]. Both Bazaz et al. [4] and Lee et al. [18] reported that the location of surgery did not influence the incidence of postoperative dysphagia but that patients undergoing multilevel ACDF had a greater incidence of postoperative dysphagia compared with those undergoing single-level surgery at 1- and 2-month followup. Frempong-Boadu et al. [12] also reported that patients undergoing multilevel anterior cervical surgery demonstrated an increased incidence of postoperative swallowing abnormalities as demonstrated on VSE compared with those undergoing single-level surgery. Unlike the findings of Smith-Hammond et al. [27] and Chin et al. [7], who did not see increased operative time in those patients with postoperative dysphagia, we found that patients with postoperative dysphagia at the time of most recent followup (ie, 12 weeks) did have greater operative time. We found no differences in gender, age, or BMI when comparing patients with and without postoperative dysphagia. Several previous prospective studies have reported that females are more prone to developing postoperative dysphagia after anterior cervical surgery [4, 18, 23].

Postoperative dysphagia after ACDF is a relatively common occurrence in the early postoperative period. It is, however, a relatively transient finding with the vast majority of cases resolving within 3 months. Given the differences observed in the incidence and severity of dysphagia when comparing the cervical and lumbar groups, it is likely that dysphagia after ACDF is the result of local factors relating to the surgery rather than other potential confounding factors, including endotracheal tube placement and general anesthesia. Although some disparity exists in the literature, age, gender, the number of levels of surgery, and the location of surgery do not seem to be related to postoperative dysphagia. Increased operative time, however, may be associated with greater incidence of persistent postoperative dysphagia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ashish Joshi, MD, MPH, for his contribution to the statistical analyses of this study. We also thank James Harrop, MD, David G. Anderson, MD, and John K. Ratliff, MD, for their contributions as participating surgeons who enrolled patients in this study.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Anderson PA, Sasso RC, Riew KD. Comparison of adverse events between the Bryan artificial cervical disc and anterior cervical arthrodesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:1305–1312. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817329a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apfelbaum RI, Kriskovich MD, Haller JR. On the incidence, cause, and prevention of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsies during anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2906–2912. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Audu P, Artz G, Scheid S, Harrop J, Albert T, Vaccaro A, Hilibrand A, Sharan A, Spiegal J, Rosen M. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after anterior cervical spine surgery: the impact of endotracheal tube cuff deflation, reinflation, and pressure adjustment. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:898–901. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazaz R, Lee MJ, Yoo JU. Incidence of dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a prospective study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:2453–2458. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bose B. Anterior cervical fusion using Caspar plating: analysis of results and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:25–31. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(97)00306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cariga P, Ahmed S, Mathias CJ, Gardner BP. The prevalence and association of neck (coat-hanger) pain and orthostatic (postural) hypotension in human spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:77–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin KR, Eiszner JR, Adams SB., Jr Role of plate thickness as a cause of dysphagia after anterior cervical fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:2585–2590. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318158dec8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniels SK, Mahoney MC, Lyons GD. Persistent dysphagia and dysphonia following cervical spine surgery. Ear Nose Throat J. 1998;77:470, 473–475. [PubMed]

- 9.Edwards CC, 2nd, Karpitskaya Y, Cha C, Heller JG, Lauryssen C, Yoon ST, Riew KD. Accurate identification of adverse outcomes after cervical spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:251–256. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B2.13878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eleraky MA, Llanos C, Sonntag VK. Cervical corpectomy: report of 185 cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:35–41. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.1.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falla D, Jull G, Rainoldi A, Merletti R. Neck flexor muscle fatigue is side specific in patients with unilateral neck pain. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:71–77. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(03)00075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frempong-Boadu A, Houten JK, Osborn B, Opulencia J, Kells L, Guida DD, Le Roux PD. Swallowing and speech dysfunction in patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: a prospective, objective preoperative and postoperative assessment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15:362–368. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heese O, Fritzsche E, Heiland M, Westphal M, Papavero L. Intraoperative measurement of pharynx/esophagus retraction during anterior cervical surgery. Part II: perfusion. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1839–1843. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heller JG, Sasso RC, Papadopoulos SM, Anderson PA, Fessler RG, Hacker RJ, Coric D, Cauthen JC, Riew DK. Comparison of BRYAN cervical disc arthroplasty with anterior cervical decompression and fusion: clinical and radiographic results of a randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:101–107. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818ee263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston FG, Crockard HA. One-stage internal fixation and anterior fusion in complex cervical spinal disorders. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:234–238. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.2.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kriskovich MD, Apfelbaum RI, Haller JR. Vocal fold paralysis after anterior cervical spine surgery: incidence, mechanism, and prevention of injury. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1467–1473. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee MJ, Bazaz R, Furey CG, Yoo J. Influence of anterior cervical plate design on dysphagia: a 2-year prospective longitudinal follow-up study. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:406–409. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000177211.44960.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MJ, Bazaz R, Furey CG, Yoo J. Risk factors for dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a two-year prospective cohort study. Spine J. 2007;7:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunsford LD, Bissonette DJ, Jannetta PJ, Sheptak PE, Zorub DS. Anterior surgery for cervical disc disease. Part 1: Treatment of lateral cervical disc herniation in 253 cases. J Neurosurg. 1980;53:1–11. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.53.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin RE, Neary MA, Diamant NE. Dysphagia following anterior cervical spine surgery. Dysphagia. 1997;12:2–8. doi: 10.1007/PL00009513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayr MT, Subach BR, Comey CH, Rodts GE, Haid RW., Jr Cervical spinal stenosis: outcome after anterior corpectomy, allograft reconstruction, and instrumentation. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:10–16. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.96.1.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mummaneni PV, Burkus JK, Haid RW, Traynelis VC, Zdeblick TA. Clinical and radiographic analysis of cervical disc arthroplasty compared with allograft fusion: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:198–209. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papavero L, Heese O, Klotz-Regener V, Buchalla R, Schröder F, Westphal M. The impact of esophagus retraction on early dysphagia after anterior cervical surgery: does a correlation exist? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1089–1093. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000261627.04944.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ratnaraj J, Todorov A, McHugh T, Cheng MA, Lauryssen C. Effects of decreasing endotracheal tube cuff pressures during neck retraction for anterior cervical spine surgery. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:176–179. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.97.2.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sasso RC, Smucker JD, Hacker RJ, Heller JG. Clinical outcomes of BRYAN cervical disc arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter trial with 24-month follow-up. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:481–491. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3180310534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith GW, Robinson RA. The treatment of certain cervical-spine disorders by anterior removal of the intervertebral disc and interbody fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1958;40:607–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith-Hammond CA, New KC, Pietrobon R, Curtis DJ, Scharver CH, Turner DA. Prospective analysis of incidence and risk factors of dysphagia in spine surgery patients: comparison of anterior cervical, posterior cervical, and lumbar procedures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:1441–1446. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000129100.59913.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart M, Johnston RA, Stewart I, Wilson JA. Swallowing performance following anterior cervical spine surgery. Br J Neurosurg. 1995;9:605–609. doi: 10.1080/02688699550040882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tervonen H, Niemela M, Lauri ER, Back L, Juvas A, Räsänen P, Roine RP, Sintonen H, Salmi T, Vilkman SE, Aaltonen LM. Dysphonia and dysphagia after anterior cervical decompression. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:124–130. doi: 10.3171/SPI-07/08/124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson DH, Campbell DD. Anterior cervical discectomy without bone graft. Report of 71 cases. J Neurosurg. 1977;47:551–555. doi: 10.3171/jns.1977.47.4.0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winslow CP, Winslow TJ, Wax MK. Dysphonia and dysphagia following the anterior approach to the cervical spine. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:51–55. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yue WM, Brodner W, Highland TR. Persistent swallowing and voice problems after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with allograft and plating: a 5- to 11-year follow-up study. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:677–682. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeidman SM, Ducker TB, Raycroft J. Trends and complications in cervical spine surgery: 1989–1993. J Spinal Disord. 1997;10:523–526. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199712000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]