Abstract

We assess whether there is evidence of an association between socioeconomic position (SEP) and HIV risk-relevant behavior among lower income heterosexual men and women in San Francisco. Respondents residing in low income areas with high heterosexual AIDS case burden in San Francisco were recruited through long-chain referral in 2006–2007. Risk measures included unprotected vaginal intercourse, concurrency and exchange sex. SEP was defined as household annual income, per capita income, and employment. Analyses utilized mixed and fixed effects models. A total of 164 men and 286 women were included in the study. SEP was only significant in the case of exchange sex among men: men reporting annual income greater than $30,000 had significantly lower odds of exchange sex relative to other men. Evaluating the connection between economic status and HIV requires additional studies covering diverse populations. Future studies should focus on community economic context as well as individual SEP.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Risk behavior, Heterosexual transmission, Socioeconomic status

Introduction

Socioeconomic position (SEP) refers to the range of socioeconomic circumstances, such as income, education and occupation, by which individuals are hierarchically stratified in society [1]. Although it has been asserted that SEP may contribute to HIV prevalence and incidence in certain populations [2–5], empirical explorations of the SEP-HIV connection in developing countries have yielded equivocal results [6–9] and few such studies have been conducted in the US [10]. Nevertheless, some have advocated for the use of income-generating programs—the broad array of income, asset, education, and skill development activities intended to help families and individuals increase income and build assets—as HIV prevention tools in the US [11, 12]. Such programs may be particularly useful in light of the scale-up and replication challenges surrounding HIV behavioral interventions [13, 14]. However, it is yet to be determined whether these programs can be sustainably effective with respect to economic development and HIV prevention. If income-generating programs do not result in reductions in HIV—either due to the challenges of blended objectives, or because of a lack of relationship between SEP and HIV—the potential exists for political and social backlash to activities that may otherwise be beneficial in their own right. The present study is one attempt to explore the relationship between SEP and HIV.

Several theories have been offered to explain the potential link between SEP and HIV [15–20]. First, poverty, low income and economic hardship have been identified as influencing the psychological well-being of persons through their effects on psychological distress and depression [16, 21–24]. Although there is little evidence that negative affective moods and depression are directly related to sexual behavior [25, 26], they are positively correlated with substance use [27–29], which in turn is associated with increased HIV risk-related behavior [30–32]. Additionally, chronic stressful events and depression have been linked to weakened immunity [23], which may lead to increased susceptibility to HIV infection [33].

Second, lower SEP may constrict an individual’s capability—the set of alternative ways of being and doing [34–36]. This has been extensively discussed with respect to female empowerment and HIV [37–39], with a focus on women’s ability to ensure their partners’ condom use [40]. Poverty and lower income are also likely to constrain livelihood options—the financial means whereby one lives [41]. For some women and men this may necessitate the exchange of sex for material or economic gain. Exchange sex is a key determinant in HIV-related risk behavior among men and women [42, 43].

Third, owing to the intersection of race and class in the US, and the concomitant factors of racism, classism and residential segregation, persons with different incomes are likely members of substantially different social and sexual networks [4, 44, 45]. Network effects are considered to be important to the transmission and acquisition of HIV and STIs both independent of behavior and due to their effect on sexual behavior [5, 20, 46–49]. Theoretically, the same sexual behaviors (e.g., unprotected intercourse) can have vastly different consequences depending on the prevalence of HIV within a sexual network and number of overlapping partners [50, 51]. Additionally, the high rates of incarceration among lower income men and women, particularly African Americans, may exert a strong influence on marital ties, marriage formation and concurrency (having multiple overlapping sexual partners) [4, 5].

Economic interventions are likely to be of limited benefit to HIV prevention unless they are able to address the relevant individual, social and structural factors that influence behavior and transmission. At best, however, most economic interventions will improve an individual’s socioeconomic factors (e.g., income) at the margins. Economic intervention participants are more likely to transition from ‘poor’ to ‘less poor’ than from ‘poor’ to ‘rich.’ Thus, we assessed whether associations between marginal differences in SEP and HIV risk-related behavior were evident among a group of predominantly lower-income heterosexuals in San Francisco. We explored four risk-related behaviors that are relevant to the theories outlined above: unprotected vaginal intercourse (UVI), substance use during UVI, concurrency, and exchange sex.

Methods

Study Population

Data are drawn from the first wave of the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance survey of heterosexuals (NHBS-HET) in San Francisco, which was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and conducted by the San Francisco Public Health Department [52]. The target population included men and women who were potentially at higher risk of HIV infection through male–female sexual transmission. These men and women were identified as those who had sex with persons of the opposite sex and who resided in ‘high risk areas’ (HRAs) in San Francisco, which were defined as the top 20% of census tracts with the highest heterosexual AIDS case burdens and the highest poverty rates. Recruitment of participants was conducted over the course of 1 year, from September 2006 through September 2007. A long-chain referral procedure was used to recruit men and women aged 18 through 50 who reported sex with at least one person of the opposite sex in the prior 12 months, and who were recruited by other eligible participants in their social networks as verified by a recruitment coupon. Persons reporting unemployment owing to disability or retirement were excluded from the sample studied here.

The long-chain referral procedure is based on RDS sampling methodology [53], and utilized systematic snowball sampling. Each participant was limited to recruiting up to three other participants, forcing the creation of long chains of recruitment to increase sample diversity. Although information on referral chains and respondents’ network sizes are typically used to develop weights for population inferences [54, 55], construction of weights was not applicable for this study as modifications to the long-chain referral procedure violated key assumptions of the RDS process. Notably, as we were intent on assuring a focus on HRAs and keeping the sample from mirroring a population of heterosexuals at risk of HIV due to injection drug use, the team decided to ‘break’ chains where referred respondents identified as IDU or resided outside of the HRAs. Such respondents were permitted to participate in the survey but were not given coupons to refer others to the study.

HIV Risk-Relevant Sexual Behavior

Our primary focus is on HIV risk-relevant sexual behavior. We operationalized risk-relevant behavior in five ways. First, respondents were asked to report on the number of sexual partners they had in the 12 months prior to the survey, and the number of these partners with whom they had UVI. We used the total number of UVI partners as our first measure of risk-relevant behavior. Our second measure was an indicator of exchange sex: whether a respondent reported having vaginal intercourse with any partners “in exchange for things like money or drugs” during the prior 12 months. The exchange sex indicator was coded as 1 if the respondent reported at least one of his/her partners as an exchange partner and 0 otherwise. These items permit examination of associations between SEP and global measures of risk-relevant behaviors, which are utilized in most standard behavioral surveys. As an alternative to global measures we relied on partner-level measures of risk-relevant behavior derived from the NHBS-HET San Francisco supplemental questionnaire. In the supplemental questionnaire respondents were asked to report on sexual episodes with each of up to five partners. Owing to the cognitive and logistical demands of partner-level inquiries the recall period was limited to the prior 6 months. Respondents reported on which of each of the prior 6 months they had sexual intercourse with a given partner. We used the measure of overlapping partners in each of the prior 6 months as a concurrency proxy, where respondents were classified as either having no concurrent partners (no partners or only one partner) or any concurrent partners (two or more partners) in the month. Our fourth and fifth measures utilized data on total UVI episodes and UVI episodes while ‘high or drunk’, respectively.

Socioeconomic Position

Our key explanatory variable of interest is SEP. We used three measures relevant to income-generating interventions. Total annual household income is classified into five groups: <$5,000, $5,000–9,999, $10,000–14,999, $15,000–29,999, and $30,000 or more. Household per capita income was calculated by dividing the midpoint income value of each of the eight original NHBS-HET income categories (income was top-coded at $75,000) by the number of household members who depended on the income. Employment status was classified into five groups: unemployed/homemaker, full-time, part-time, student and other (Because our focus in on income and employment we do not examine educational attainment as an SEP factor).

Other Variables

Our models adjusted for potential confounders. Age was classified into four groups: 18–24, 25–29, 30–39, and 40–50 years old. Marital status was classified as ‘currently married or cohabitating’, ‘formerly married (separated/divorced/widowed)’ and ‘never married’. In analyses of number of sexual episodes with partners we adjusted for whether the respondent identified the partner as a main or non-main (casual/exchange) partner, and whether the respondent knew the partner’s HIV serostatus. Analyses also adjusted for whether the respondent resided in or out of a designated HRAs.

Data Analysis

We present descriptive statistics for the pooled sample stratified by sex and marital status. We present counts using boxplots in which the dark horizontal bars indicate the median and the bottom and top of the boxes represent the interquartile range. Regression models were constructed in order to determine the association of SEP on each of the HIV risk-related behaviors after adjusting for confounders and within-person correlations. Our analysis of the association between SEP and total UVI partners was conducted using negative binomial fixed effects models, adjusting for age, current marital status and residence in HRAs. Binomial logisitic regression was used to examine the relationship between SEP and the proportion of respondents reporting exchange sex. Analysis of concurrency was conducted using a mixed effects binomial model. The concurrency dataset was structured with six observations for each individual representing each of the preceding 6 months. Concurrency models adjusted for age, HRA residence and an indicator of marital status. Our analyses of the association between SEP and UVI episodes (both total episodes and episodes while high or drunk) were conducted using a mixed effects Poisson model where partner-level data was clustered within individuals. The UVI Poisson models adjusted for age, HRA residence, an indicator of whether the partner was a main partner, and an indicator of whether the serostatus of the partner was unknown to the respondent. For all analyses the three SEP variables—total household income, household per capita income and employment—were entered alternatively. In the UVI episode analyses we also test an interaction term between the socioeconomic measure and the main partner indicator. All analyses were stratified by sex.

Results

The sample consisted of 164 men and 286 women. The majority of respondents reported never having been married: 78% of men and 77% of women. Only 8% of men and 6% of women reported being currently married. The majority of respondents were black (over 80% of men and women). The sample was predominately lower-income although displaying a range of SEP characteristics. In 2007, the median household income in San Francisco County was $67,333 and approximately 11% of residents had a household income below the Federal Poverty Line (which was $10,210 for a single adult). Within our sample, 45% of men and 55% of women reported household income below $10,000, and 18 and 12% of men and women, respectively, reported an income above $30,000. Roughly 42% of men and 38% of women reported full or part time employment, and 49 and 48% of men and women, respectively, reported being unemployed or homemakers. Most (76% of men and 73% of women) respondents resided in HRAs. The distribution of education was similar across sexes: 21% reported having less than a high school degree, 48% had a high school diploma or GED, and 31% had at least some postsecondary education.

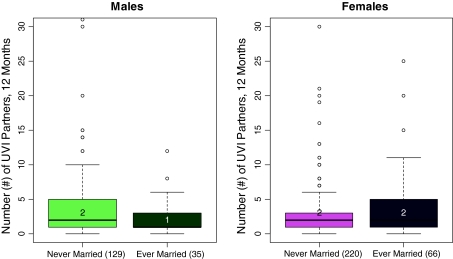

In general, none of our measures of socioeconomic position—household income, per capita income and employment status—produced significant results for any of the HIV risk-relevant measures. With respect to total UVI partners in the prior 12 months, men reported a mean of four and women reported a mean of five. As evident in Fig. 1, the mean values are substantially influenced by the presence of outliers for both men and women. Men and women reported a median of two UVI partners in a 12 month period. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) for the mean number of partners (our inferential model) was roughly one regardless of income, per capita income, or employment status for both men and women (Table 1). Exceptions were evident among male respondents when income categories were used. Although the pattern is suggestive of a modest gradient decline in UVI partners as income increases the only significant income effect was evident for men with an annual income of $15,000–$29,000 compared to men with income less than $5,000 (IRR 0.52, P < .01). For both men and women respondents who identified as having ‘other’ employment had significantly higher rates of UVI partners compared to employed persons (IRR 2.0, P < .05) (‘Other’ employment respondents are those who were students or did not consider themselves employed, unemployed or a homemaker. Disabled and retired persons were excluded.). Owing to lack of significant findings, we do not present relative risk tables for subsequent analyses.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of total UVI partners in 12 months among respondents, by sex and marital status. Note: Values in parentheses reflect the total number of respondents. Boxes represent the interquartile range, and the dark horizontal line indicates the median

Table 1.

Incidence rate ratios (IRR) of number of unprotected vaginal intercourse partners in 12 months by sex

| Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | (95% CI) | IRR | (95% CI) | |

| Model 1: income | ||||

| <$5,000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| $5,000–9,999 | 1.02 | (0.58, 1.79) | 0.71 | (0.47, 1.06) |

| $10,000–14,999 | 0.71 | (0.42, 1.21) | 0.96 | (0.60, 1.54) |

| $15,000–29,999 | 0.52** | (0.32, 0.86) | 0.70 | (0.43, 1.13) |

| $30,000 or over | 1.09 | (0.66, 1.78) | 0.96 | (0.55, 1.67) |

| AIC | 731 | 1,362 | ||

| Model 2: per capita income | ||||

| Log income per capita | 0.97 | (0.82, 1.14) | 0.90 | (0.76, 1.06) |

| AIC | 734 | 1,360 | ||

| Model 3: employment | ||||

| Employed (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Unemployed | 1.43 | (0.98, 2.09) | 1.32 | (0.94, 1.87) |

| Other | 2.00* | (1.10, 3.65) | 1.91* | (1.18, 3.08) |

| AIC | 739 | 1,363 | ||

All models adjusted for age, marital status and residence in designated high risk area

AIC Akaike information criterion measure of model fit

* P < .05, ** P < .01

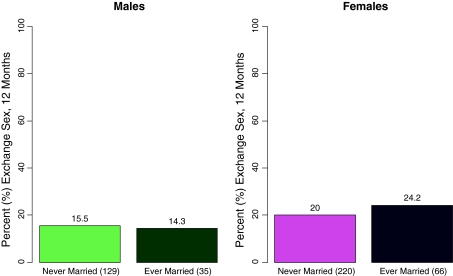

Roughly 15% of men and 21% of women reported having at least one exchange sex partner of the opposite sex in the prior 12 months. A slightly larger proportion of women who had ever married reported having exchange sex in the prior 12 months compared to women who had never married (Fig. 2). There were no differences in the relative odds of exchange sex based on SEP, with the exception that men with an income of $30,000 or more had lower odds of exchange sex compared to other men (ROR 0.09, P < .05).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of respondents reporting exchange sex in the prior 12 months, by sex and marital status. Note: Values in parentheses reflect the total number of respondents

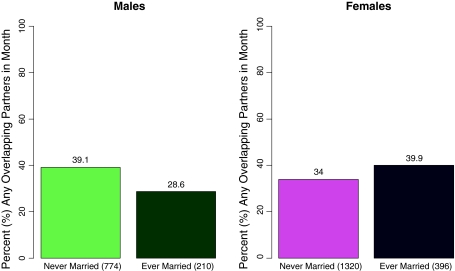

The concurrency analysis consisted of 984 respondent-month observations on 164 men and 1,716 observations on 286 women. Concurrency—having overlapping partners in a given month—was identified in 37% of male observations and 35% of the female observations. Differences were evident by marital status for both men and women, but the patterns differed between men and women (Fig. 3). Whereas, the proportion of concurrent observations declines for men who were ever married (29%) compared to men who were never married (39%), it increases among women who were ever married (40%) compared to women who were never married (34%). These unadjusted differences reflect different gender distributions in marital status. In the adjusted model, married men and women had significantly lower odds of concurrent partners compared to those who never married (ROR 0.04–0.07, P < .01). There were no significant differences in the relative odds ratios of concurrency by any of our SEP measures.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of respondent-month observations with two or more overlapping partners in a month (6 month recall period), by sex and marital status. Note: Values in parentheses reflect the total number of respondent-month observations

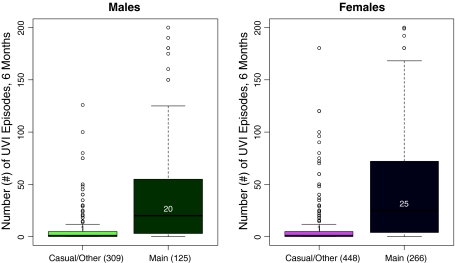

Analyses of per partner UVI episodes consisted of 475 partner observations on 161 men, and 738 observations on 283 women (Excluded respondents did not report sexual intercourse with any partner of the opposite sex during the prior 6 months.). Men reported 19 mean UVI episodes per partner (SD 56) compared to 25 mean UVI episodes reported by women (SD 52). Partner type and outliers exert substantial influence on the mean number of episodes as evident in Fig. 4. With casual partners the median UVI per partner episodes was one for both men and women, in contrast to a median of 20–25 UVI episodes with main partners. Compared to sexual episodes with casual partners the IRR of UVI with main partners was significantly greater for men (IRR 7.2, P < .001) and women (IRR 7.7, P < .001) in the multivariable Poisson regression models. Men and women reported significantly fewer UVI episodes with partners of undisclosed HIV-infection status compared with partners of known HIV status (IRR 0.6 and 0.5, respectively, P < .001). No significant associations were evident between the measures of SEP and UVI episodes in the models. Findings were similar with respect to per partner episodes of UVI while high or drunk. Men reported a mean of 17 UVI episodes while high or drunk (SD 59) and women reported a mean of 20 UVI episodes while high or drunk (SD 44). In multivariable models no SEP measures were significantly associated with UVI episodes in the presence of substances.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of per partner UVI episodes in the prior 6 months among respondent-partner observations, by sex and partner type. Note: Values in parentheses reflect the total number of respondent-partner observations. Boxes represent the interquartile range, and the dark horizontal line indicates the median

Discussion

Advocacy of income-generating programs as HIV prevention tools must be grounded on evidence of potential effectiveness, sustainability and a connection between economic circumstances and HIV risk. The goal of the present study was to assess whether evidence of an association between SEP and HIV risk-relevant behaviors could be identified in a cross-sectional observational study of lower-income heterosexuals. In general, we found no evidence of a direct association for either men or women. The case for an association between poverty and HIV is typically grounded on the basis of regional or racial/ethnic associations [12]. Our lack of significant findings here may support, rather than refute this conception of an SEP-HIV link. Respondents in the sample tended to reside in the same geographic areas within San Francisco, which are the poorest areas of the city. The contextual effect of neighborhood economic circumstances may be more important to HIV risk than individual economic status. Thus, income generating programs that target individuals may be less effective than programs that target community economic development. Alternatively, the absence of a demonstrated association between residence in the geographically bound HRAs and the five measures of risk-relevant behavior would suggest that social/sexual networks may be a more important focus for HIV prevention than geographic targeting alone.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess individual economic circumstances and HIV risk-relevant behavior among almost exclusively lower income heterosexuals in the US. We should note that the data used here were drawn from a non-probability sample, which is likely not fully representative of the heterosexual population in San Francisco’s HRAs. Moreover, the focus on HRAs precludes our ability to assess community economic context as a determinant of HIV risk-relevant behaviors. Additional studies encompassing more diverse geographic and household populations are necessary in determining how structural factors such as SEP may contribute to HIV risk among heterosexuals. Notably, heterosexual transmission constitutes a smaller proportion of AIDS cases in the West compared to the South and Northeast regions of the country [56], and regions differ substantially with respect to the socioeconomic contexts they, their states and rural and urban areas face [57]. Consequently, associations between SEP and HIV are likely to differ across geographic and residential characteristics.

HIV transmission in sexual partnerships is a function of exposure, infectivity and susceptibility. We have addressed the potential influence of SEP on behaviors relevant to HIV exposure. The study is limited by the restricted and blunt definitions of SEP, and by the inability to address structural factors such as segregation and networks that may be relevant to exposure. Other studies should also examine whether SEP is associated with differences in infectivity and susceptibility among lower income heterosexuals. Factors such as material hardship and health care access may be important determinants of differentials in infectivity and susceptibility. Future studies that better account for the complexity of both SEP and HIV risk, and that are designed to provide comparative analyses of the role of contextual differences will be best suited for exploring potential associations between SEP and HIV among lower-income heterosexuals.

Conclusion

Although we were unable to identify a consistent or significant relationship between SEP and risk-relevant behavior, we do not conclude from these findings that economic interventions will not influence HIV risk. In the absence of a direct SEP-HIV link, economic interventions may influence other proximal factors to HIV risk such as self-efficacy and agency. Given the dearth of studies addressing the topic of SEP and HIV, however, it is difficult to make a case for or against economic interventions as HIV prevention tools. Further investigation of the SEP-HIV link is warranted. Studies should utilize broader SEP measures and move beyond sexual behavior to incorporate other factors relevant to HIV exposure, infectivity and susceptibility among lower-income heterosexuals. Use of household or venue-based probability sampling will improve sample and network diversity and better support population-level inference. Multisite observational studies can exploit residential and temporal differences in local-level economic circumstances to approximate a ‘natural experiment’ better capable of providing comparative data on the potential SEP-HIV link. Such research will provide an important foundation for development and implementation of effective policies and programs to reduce heterosexual HIV transmission in the US.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the San Francisco NHBS team for their contributions and the NHBS respondents for their participation. The National HIV Behavioral Surveillance was funded by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC grant U62 PS000961-01).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9671-6

References

- 1.Robert SA. Socioeconomic position and health: the independent contribution of community socioeconomic context. Annu Rev Sociol. 1999;25:489–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.25.1.489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J, Pronyk P, Barnett T, Watts C. Exploring the role of economic empowerment in HIV prevention. AIDS. 2008;22:S57–S71. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000341777.78876.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poundstone KE, Strathdee SA, Celentano DD. The social epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:22–35. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S115–S122. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the Southern United States: sexual networks and social context. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(7):S39–S45. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillespie S, Kadiyala S, Greener R. Is poverty or wealth driving HIV transmission? AIDS. 2007;21:S5–S16. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300531.74730.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hargreaves JR, Bonell CP, Boler T, Boccia D, Birdthistle I, Fletcher A, et al. Systematic review exploring time trends in the association between educational attainment and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22(3):403–414. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2aac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishra V, Assche SRV, Greener R, Vaessen M, Hong R, Ghys PD, et al. HIV infection does not disproportionately affect the poorer in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 7):S17–S28. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300532.51860.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wojcicki JM. Socioeconomic status as a risk factor for HIV infection in women in East, Central and southern Africa: a systematic review. J Biosoc Sci. 2005;37(1):1–36. doi: 10.1017/S0021932004006534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FEA, Coyne-Beasley T, Doherty I, Stancil TR, et al. Heterosexually transmitted HIV infection among African Americans in North Carolina. JAIDS. 2006;41(5):616–623. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191382.62070.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherman SG, German D, Cheng Y, Marks M, Bailey-Kloche M. The evaluation of the JEWEL project: an innovative economic enhancement and HIV prevention intervention study targeting drug using women involved in prostitution. AIDS Care. 2006;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stratford D, Mizuno Y, Williams K, Courtenay-Quirk C, O’Leary A. Addressing poverty as risk for disease: recommendations from CDC’s consultation on microenterprise as HIV prevention. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(1):9–20. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albarracin D, Durantini MR, Earl A. Empirical and theoretical conclusions of an analysis of outcomes of HIV-prevention intervention. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15(2):73–78. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00410.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbst JH, Sherba RT, Crepaz N, DeLuca JB, Zohrabyan L, Stall RD, et al. A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men. JAIDS. 2005;39(2):228–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aral SO, Adimora AA, Fenton KA. Understanding and responding to disparities in HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in African Americans. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):337–340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnett T, Weston M. Wealth, health, HIV and the economics of hope. AIDS. 2008;22:S27–S34. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327434.28538.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkman LF, Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 137–173. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogben M, Leichliter JS. Social determinants and sexually transmitted disease disparities. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(12):S13–S18. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818d3cad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishnan S, Dunbar MS, Minnis AM, Medlin CA, Gerdts CE, Padian NS. Poverty, gender inequities, and women’s risk of human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:101–110. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stratford D, Ellerbrock TV, Chamblee S. Social organization of sexual-economic networks and the persistence of HIV in a rural area in the USA. Cult Health Sex. 2007;9(2):121–135. doi: 10.1080/13691050600976650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caplan LJ, Schooler C. Socioeconomic status and financial coping strategies: the mediating role of perceived control. Soc Psychol Q. 2007;70(1):43–58. doi: 10.1177/019027250707000106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feldman PJ, Steptoe A. How neighborhoods and physical functioning are related: the roles of neighborhood socioeconomic status, perceived neighborhood strain, and individual health risk factors. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27(2):91–99. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross CE, Huber J. Hardship and depression. J Health Soc Behav. 1985;26(4):312–327. doi: 10.2307/2136655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahn JR, Fazio EM. Economic status over the life course and racial disparities in health. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:76–84. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crepaz N, Marks G. Are negative affective states associated with HIV sexual risk behaviors? A meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. 2001;20(4):291–299. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.20.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schroder KEE, Johnson CJ, Wiebe JS. An event-level analysis of condom use as a function of mood, alcohol use, and safer sex negotiations. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38(2):283–289. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markou A, Kosten TR, Koob GF. Neurobiological similarities in depression and drug dependence: a self-medication hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18(3):135–174. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conner KR, Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Meta-analysis of depression and substance use and impairment among intravenous drug users (IDUs) Addiction. 2008;103(4):524–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conner KR, Pinquart M, Holbrook AP. Meta-analysis of depression and substance use and impairment among cocaine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;98(1–2):13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryant KJ. Expanding research on the role of alcohol consumption and related risks in the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(10–12):1465–1507. doi: 10.1080/10826080600846250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raj A, Reed E, Santana MC, Walley AY, Welles SL, Horsburgh CR, et al. The associations of binge alcohol use with HIV/STI risk and diagnosis among heterosexual African American men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101(1–2):101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson FS, Cleland CM, Chaple M, Hamilton Z, Prendergast ML, Rich JD. Substance use, mental health problems, and behavior at risk for HIV: evidence from CJDATS. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(4):459–469. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan DJ. Factors affecting sexual transmission of HIV-1: current evidence and implications for prevention. Curr HIV Res. 2005;3(3):223–241. doi: 10.2174/1570162054368075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gasper D. What is the capability approach? Its core, rationale, partners and dangers. J Socio Econ. 2007;36:335–359. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2006.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nussbaum M, Sen AK, editors. The quality of life. Oxford: Clarendon; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sen AK. Commodities and capabilities. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinkham S, Malinowska-Sempruch K. Women, harm reduction and HIV. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(31):168–181. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Logan TK, Cole J, Leukefeld C. Women, sex, and HIV: social and contextual factors, meta-analysis of published interventions, and implications for practice and research. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(6):851–885. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greig FE, Koopman C. Multilevel analysis of women’s empowerment and HIV prevention: quantitative survey results from a preliminary study in Botswana. AIDS Behav. 2003;7(2):195–208. doi: 10.1023/A:1023954526639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blankenship KM, Friedmann SR, Dworkin S, Mantell JE. Structural interventions: concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moser C, Dani AA, editors. Assets, livelihoods, and social policy. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elifson KW, Boles J, Darrow WW, Sterk C. HIV seroprevalence and risk factors among clients of female and male prostitutes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;20(2):195–200. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199902010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones D, Irwin K, Inciardi J, The Multicenter Crack Cocaine. HIV Infection Study Team The high-risk sexual practices of crack-smoking sex workers recruited from the streets of three American cities. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25(4):187–193. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199804000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Massey DS, Denton NA. American apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams DR. African–American health: the role of social environment. J Urban Health. 1998;75(2):300–321. doi: 10.1007/BF02345099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaplan MS, Crespo CJ, Huguet N, Marks G. Ethnic/racial homogeneity and sexually transmitted disease: a study of 77 Chicago community areas. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(2):108–111. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818b20fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laumann EO, Youm YM. Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: a network explanation. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26(5):250–261. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21(15):2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1007–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kretzschmar M. Sexual network structure and sexually transmitted disease prevention: a modeling perspective. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27(10):627–635. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200011000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morris M, Kretzschmar M. Concurrent partnerships and the spread of HIV. AIDS. 1997;11:641–648. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gallagher KM, Sullivan PS, Lansky A, Onorato IM. Behavioral surveillance among people at risk for HIV infection in the US: the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(S1):32–38. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44(2):174–199. doi: 10.1525/sp.1997.44.2.03x0221m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling II: deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 2002;49(1):11–34. doi: 10.1525/sp.2002.49.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociol Methodol. 2004;34:193–239. doi: 10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00152.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in urban and rural areas of the United States, 2006. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Supplemental Report 2008;13(No. 2):[inclusive page numbers].

- 57.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2008. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, US Census Bureau, Current Population Reports; 2009. [Google Scholar]