Abstract

Chromatin immunoprecipitation identifies specific interactions between genomic DNA and proteins, advancing our understanding of gene-level and chromosome-level regulation. Based on chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments using validated antibodies, we define the genome-wide distributions of 19 histone modifications, one histone variant, and eight chromatin-associated proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos and L3 larvae. Cluster analysis identified five groups of chromatin marks with shared features: Two groups correlate with gene repression, two with gene activation, and one with the X chromosome. The X chromosome displays numerous unique properties, including enrichment of monomethylated H4K20 and H3K27, which correlate with the different repressive mechanisms that operate in somatic tissues and germ cells, respectively. The data also revealed striking differences in chromatin composition between the autosomes and between chromosome arms and centers. Chromosomes I and III are globally enriched for marks of active genes, consistent with containing more highly expressed genes, compared to chromosomes II, IV, and especially V. Consistent with the absence of cytological heterochromatin and the holocentric nature of C. elegans chromosomes, markers of heterochromatin such as H3K9 methylation are not concentrated at a single region on each chromosome. Instead, H3K9 methylation is enriched on chromosome arms, coincident with zones of elevated meiotic recombination. Active genes in chromosome arms and centers have very similar histone mark distributions, suggesting that active domains in the arms are interspersed with heterochromatin-like structure. These data, which confirm and extend previous studies, allow for in-depth analysis of the organization and deployment of the C. elegans genome during development.

Caenorhabditis elegans was the first animal with a completed genome sequence, which accelerated investigations into the molecular bases of a wide range of biological processes (The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998). All genome functions occur in the context of chromatin, which comprises DNA, histones, and other structural proteins and enzymes, which together regulate transcription and other aspects of genome dynamics. An especially widespread and important mode of regulation is mediated by post-translational modification of histone tails by specific enzymes (Kouzarides 2007). Therefore, deciphering how the genome is organized and deployed during development requires knowledge of the in vivo genomic locations of differentially modified histones.

The C. elegans genome has a number of features that make it a particularly powerful system for advancing our understanding of genome biology. The genome is compact, consisting of 100 Mb of DNA containing approximately 20,000 protein-coding genes. Most introns are short, and average intergenic distances are small. There is a good correspondence between genomic and experimental data, since the reference genome is derived from the Bristol N2 wild-type strain, the same strain used by the vast majority of C. elegans labs. Rapid molecular genetic and reverse genetic methods make it possible to efficiently assess the biological function of specific coding and non-coding sequences.

The C. elegans genome is organized into six chromosomes. Hermaphrodites have five pairs of autosomes and a pair of X chromosomes, whereas animals inheriting only one X chromosome develop as males. To equalize the expression of X-linked genes in the two sexes, transcription from both X chromosomes is partially repressed in somatic cells of hermaphrodites by a dosage compensation complex related to mitotic condensin (Meyer 2010). In both XX and XO worms, the X chromosomes are largely silenced in germ cells by a distinct and less-well-understood machinery than used in the soma (Schaner and Kelly 2006). C. elegans does not have a defined centromeric locus on each chromosome; instead, the chromosomes are holocentric, with centromeric function distributed along the length of each chromosome (Albertson and Thomson 1982; Maddox et al. 2004). During meiosis, a special region near one end of each chromosome, known as a “Homolog Recognition Region” or “Pairing Center,” mediates pairing and synapsis between homologous chromosomes through interactions with components of the nuclear envelope (MacQueen et al. 2005; Phillips et al. 2005; Phillips and Dernburg 2006). Meiotic crossover recombination is elevated on both distal regions or “arms” of the five autosomes, which are enriched for repeated sequences and where genes are more sparse and introns are relatively large compared to the central region of the chromosome (Barnes et al. 1995; The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998; Prachumwat et al. 2004). The X chromosome displays more uniform gene density and recombination rates along its length. Zones of highly condensed heterochromatin have not been observed by cytological analysis (Albertson et al. 1997).

The first C. elegans chromatin factors whose distributions were analyzed genome-wide were DPY-27 and SDC-3, members of the dosage compensation complex (Ercan et al. 2007). That and subsequent studies (Ercan et al. 2009; Jans et al. 2009) revealed that the dosage compensation complex is recruited to and spreads from specific sites on the X chromosome and is most concentrated upstream of active X-linked genes. Since then, a limited number of histone modifications or variants have been mapped in C. elegans. These studies showed that the organization of C. elegans genic chromatin has properties similar to those of other organisms and additionally provided novel insights into chromatin structure and function (Whittle et al. 2008; Gu and Fire 2009; Kolasinska-Zwierz et al. 2009; Ooi et al. 2009; Furuhashi et al. 2010; Greer et al. 2010; Hall et al. 2010; Rechtsteiner et al. 2010). For example, H3K4me3 and the histone variant HTZ-1/H2A.Z were found to be enriched in promoter regions of actively transcribed genes and H3K36me3 on gene bodies, with the latter more enriched on exons than introns and transmitted during embryogenesis independently of ongoing transcription (Whittle et al. 2008; Kolasinska-Zwierz et al. 2009; Furuhashi et al. 2010; Rechtsteiner et al. 2010). Further studies of H3K4me3 uncovered links with longevity and developmental life history (Greer et al. 2010; Hall et al. 2010). H3K9me3, a typical mark of silent chromatin, was observed to be at higher levels on silent genes but also enriched on chromosome arms (Gu and Fire 2009). These studies demonstrate the value of global mapping studies and argue for the usefulness of a more comprehensive map.

To better understand the relationships between genome organization and function in C. elegans, we have determined the distributions of 19 histone modifications, a histone variant, a histone methyltransferase, RNA Polymerase II, a nuclear envelope–associated protein, and proteins that participate in dosage compensation, initially in two different embryo populations and L3 larvae. Early embryos (EE) are expected to reflect a mix of chromatin status inherited through the oocyte and sperm and chromatin states associated with global activation of zygotic transcription, rapid mitotic division, and establishment of dosage compensation. Mixed stage embryos (MxE) have robust zygotic transcription of genes involved in tissue differentiation and morphogenesis, and most have fully implemented dosage compensation. L3 larvae primarily consist of fully differentiated somatic cells and mitotic germ cells. Using these data, we investigated how the distributions of numerous chromatin components are related to each other and to gene expression and other chromatin functions. All of the data are publicly available at the modENCODE Data Coordination Center website (http://intermine.modencode.org/) as a resource for the scientific community.

Results and Discussion

Histone modifications and chromatin factors cluster by function

A total of 44 ChIP-chip (chromatin immunoprecipitation on microarray) experiments were conducted in C. elegans early embryos, mixed stage embryos, or L3 larvae. Each experiment was performed at least in duplicate from independent C. elegans cultures and extract preparations. We used antibodies to detect genome-wide distributions for 19 different histone modifications (H3K4me1/2/3, H3K9me1/2/3, H3K27me1/3, H3K36me1/2/3, H3K79me1/2/3, H3K27ac, H4K8ac, H4K16ac, H4tetra-ac, and H4K20me1), one histone variant (HTZ-1), seven chromatin factors (DPY-26/27/28, SDC-3, MIX-1, LEM-2, MES-4), and RNA polymerase II. All antibodies used for ChIP were validated for target specificity (see Methods). The detection platform, NimbleGen Custom 2.1M Tiling arrays, provided almost complete tiled coverage across the genome with probes of 50 nt in length. Biological replicates displayed reproducibility when viewed on the genome browser and correlated well across the genome (Supplemental Fig. S1; Supplemental Table S1). Data were normalized and smoothed, and replicates were combined to identify enriched regions and genome-wide signal profiles (see Methods).

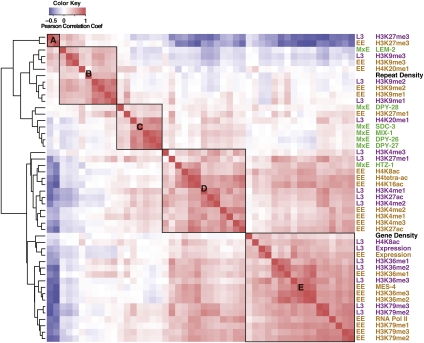

To investigate relationships between the distributions of particular modifications and chromatin-associated proteins, we first determined the genome-wide correlation of each ChIP data set with each of the other data sets. We included three other parameters—repeat density, gene density, and gene expression (RNA-seq) data—in these genome-wide comparisons. We next performed hierarchical clustering of the measured genome-wide correlation coefficients (Fig. 1). This analysis identified five major groups (A–E in Fig. 1). Each mark or protein analyzed at different stages was highly correlated between the stages and therefore clustered together, as did marks that are known to function in related mechanisms, such as transcriptional activation, repression, or dosage compensation. For example, H3K9me3 data in both EE and L3 (in Group B) were highly correlated with each other. Similarly, marks associated with transcription elongation such as H3K36me1/2/3 and H3K79me1/2/3 (in Group E) were also highly correlated with each other across developmental stages. The observation of similar patterns at different developmental stages suggests that these chromatin proteins and histone modifications perform their core functions throughout worm development. The comparative analysis of all of the data sets validated previously known or predicted functional relationships and suggested functions for some specific marks and factors. The most striking features of each group are described below.

Figure 1.

The distributions of histone marks, chromatin proteins, and genome features cluster into distinct groups. Data for all factors were clustered based on the pairwise Pearson correlations of the median signals in 1-kb windows along all chromosomes. (Red) Positive correlations; (blue) negative correlations. Factors are (brown) early embryo (EE), (green) mixed embryo (MxE), (purple) L3 larvae (L3), and (black) common features. Hierarchical clustering grouped all factors into two major groups, one related to transcriptionally repressed states (upper left) and the other related to transcriptionally active states (bottom right). The factors associated with repressed states clustered into three subgroups—A, B, and C. The factors associated with transcriptionally active states clustered into two subgroups—D associated with promoters and 5′ regions of genes and E associated with gene bodies. The dendrogram to the left of the heatmap shows the clustering tree. Pairs of horizontal branches linking two subclusters represent the distance of the two farthest separated factors in the subclusters calculated by the ChIP genome profile dissimilarity.

H3K27me3 distribution is anti-correlated with RNA levels

Group A (Fig. 1) includes H3K27me3 in both early embryos and L3s and is strongly anti-correlated with gene expression, RNA Pol II localization, and multiple marks associated with transcriptionally active regions (Fig. 1), indicating that H3K27me3 is enriched in transcriptionally silent regions of the worm genome. Consistent with this observation, the magnitude of H3K27me3 signals over protein-coding genes is inversely correlated with their expression levels (Supplemental Fig. S2). These findings are in accord with data from other experimental systems showing that H3K27me3 is associated with repressed genes (Muller and Verrijzer 2009).

Histone H3K9 methylation is coupled to the distribution of repetitive sequences and association with the nuclear membrane

Group B (Fig. 1) contains H3K9me1/2/3, LEM-2, and repetitive sequences. H3K9me3 is a hallmark of heterochromatin and is often enriched on repetitive sequences (Peters et al. 2003; Guenatri et al. 2004; Martens et al. 2005). The nuclear membrane protein LEM-2 is known to localize at the nuclear envelope (Lee et al. 2000; Ikegami et al. 2010). Analysis of the association of H3K9me3 and LEM-2 with genes ranked by expression levels revealed enrichment of both on silent genes (Supplemental Fig. S2). In addition, all three methylation states of H3K9 show enrichment on repeat sequences (Gerstein et al. 2010). These findings suggest that H3K9 methylation and/or association with the nuclear envelope help maintain silencing of repetitive sequences in worms and may contribute to the maintenance and stability of heterochromatin-like regions, as observed in other organisms (Peng and Karpen 2008).

H3K27me1 and H4K20me1 are enriched on the X chromosome

Group C (Fig. 1) is dominated by C. elegans dosage compensation proteins (DPY-26, DPY-27, DPY-28, SDC-3, and MIX-1). Consistent with extensive evidence that these proteins collaborate to repress expression of X-linked genes in XX hermaphrodites (Meyer 2005; Ercan et al. 2007), their ChIP data sets show higher signals on the X chromosome than on autosomes (Supplemental Fig. S2), as observed previously for some of these factors (Ercan et al. 2007, 2009; Jans et al. 2009). Interestingly, two histone modifications, H3K27me1 and H4K20me1, also group with the dosage compensation proteins (Supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting potential roles in dosage compensation (see below).

HTZ-1, H4 acetyl marks, and H3K4me1/2/3 are found at the promoters of heavily transcribed genes

Group D (Fig. 1) includes H3K4me2/3, H3K27ac, H4K8ac, H4K16ac, H4tetra-ac, and HTZ-1/H2A.Z, all of which are typically enriched in the promoter regions of highly expressed genes (Barski et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2008). Gene profile plots show these marks to be similarly enriched at the 5′ ends of highly expressed C. elegans genes (Supplemental Fig. S2). H3K4me3 and H3K27ac share especially similar profiles over promoters, suggesting coordinated regulation and perhaps similar roles.

RNA polymerase II is tightly associated with H3K36 and H3K79 methylation

Group E (Fig. 1) contains marks that overlie most of the transcribed regions of the genome, including RNA Pol II, H3K36me1/2/3, H3K79me1/2/3, and MES-4, an H3K36 methyltransferase. Also falling into this group are transcripts themselves, as mapped by RNA-seq (Gerstein et al. 2010). All of the marks in this group are enriched in the bodies of highly expressed genes (Supplemental Fig. S2). H3K79me2/3 is enriched in regions proximal to the transcript start site, while H3K36me3 is more uniformly distributed, as has been observed in human genes (Barski et al. 2007; Steger et al. 2008). Finding H3K79 methylation grouping with H3K36 methylation and RNA Pol II is consistent with the observation in mammalian systems that H3K79 methylation is ubiquitously coupled with gene transcription (Steger et al. 2008).

Worm chromosomes contain broad chromatin domains that differentiate the centers from the arms

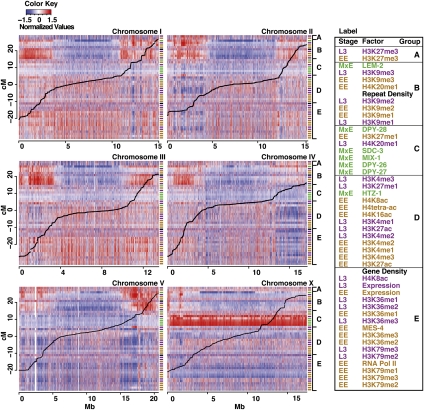

To examine whether histone modifications or chromatin proteins mark particular chromosomal regions on a global scale, we plotted ChIP-chip signals, ordered by group, across each worm chromosome (Fig. 2; see Supplemental Fig. S3 for an enlarged view of each chromosome). This analysis revealed striking broad domains of signal enrichment and depletion, with central regions having chromatin properties distinct from distal regions. Previous studies in C. elegans have revealed that the distal regions, termed “chromosome arms,” are distinct from the center in several respects. Gene expression is generally higher in central regions than in arm regions, and central regions contain more essential genes, especially on Chr I and III (The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998; Kamath et al. 2003). The arm regions, which span up to ∼4 Mb at each end, contain more repeated sequences (The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998). Moreover, the arms show markedly higher meiotic recombination rates than central regions (Barnes et al. 1995; The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998; Prachumwat et al. 2004). Recombination rates (Fig. 2, black lines) are fairly constant within arm and central regions, with transitions that vary in their abruptness both between chromosomes and on the two arms of each chromosome (Fig. 2; Barnes et al. 1995; Rockman and Kruglyak 2009).

Figure 2.

Histone marks and chromatin proteins show distinct patterns on different chromosomes and on the arms versus central region of each chromosome. The signal intensity of all analyzed factors is shown across all six chromosomes. Colored cells show median signals in 1-kb windows: (red) high signal, (blue) low signal. Each row corresponds to a factor. The order of factors is as shown in Figure 1 and in the key to the right. The colored labels to the right of each track indicate stage, as in Figure 1. (Thick black lines) Marey plots of recombination distances. Enlarged views of each chromosome are in Supplemental Figure S3.

Both arms of each autosome and the left arm of the X show strong association with the inner nuclear membrane protein LEM-2 (Fig. 2; Ikegami et al. 2010). Compared to chromosome centers, the arms are enriched in repressive histone marks, especially H3K9me1/2/3, and slightly depleted of active histone marks (Fig. 2). The boundaries between the arms and central domains that emerged from our analysis correspond well with recombination rate transition points (Fig. 2). Examination at higher resolution revealed that the domain transitions do not occur at precise locations (Supplemental Figs. S3, S4). At the transition from an arm to a central domain, H3K9 methylation density (especially H3K9me1 and H3K9me2) gradually decreases over several hundred kilobases and many genes, while the density of marks associated with gene activity such as H3K4me3, H3K36me3, and H3K79me3 gradually increases. Gradual transitions suggest that the domain structure of C. elegans chromosomes may not be maintained by unique boundary elements.

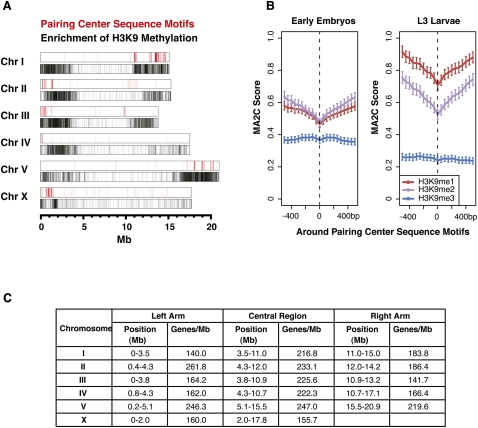

H3K9 methylation in Drosophila and mammals has been shown to be important for the stability of repetitive sequences (Peng and Karpen 2008). The enrichment of H3K9 methylation on the repeat-rich arm regions of C. elegans suggests a similar role. Consistent with this possibility, all three H3K9 methyl marks are enriched on transposable elements and other repeated sequences (Gerstein et al. 2010). Although H3K9me1/2/3 are enriched on both chromosome arms, enrichment is often higher on the arm that contains the meiotic pairing center (Fig. 3A). During meiosis, interactions between homologous chromosomes occur through the meiotic pairing centers. An unusual group of zinc finger proteins (ZIM proteins) binds to these regions, connecting the meiotic pairing centers to the microtubule cytoskeleton to promote chromosome movement and synapsis (Phillips and Dernburg 2006; Sato et al. 2009). A family of short, dispersed sequences that determine the meiotic pairing centers have been deduced from in vivo and in vitro binding experiments (Phillips et al. 2009). Although these sequences are distributed within the broad repressive chromatin domains (Fig. 3A), comparison of their locations with H3K9 methylation revealed that the sequences actually lie in regions with locally reduced levels of H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 (Fig. 3B). Association of H3K9me3 with the meiotic pairing arm has been previously noted and shown to be independent of ZIM binding (Gu and Fire 2009). Additional studies will be necessary to determine the possible contribution of H3K9 methylation to meiotic chromosome behavior.

Figure 3.

H3K9 methylation is enriched on chromosome arms, especially the arms with the pairing center. (A, red lines) Meiotic pairing center motif coordinates, obtained from a motif scan analysis (Phillips et al. 2009). On autosomes, >90% of these motifs lie within the pairing center regions, as do ∼65% of those on the X chromosome. (Below, black lines) Regions enriched in H3K9 methylation. (B) Average H3K9me1/2/3 signals around all pairing center motifs are shown in early embryo (EE) and L3 larvae (L3). (C) Approximate coordinates of chromosome arms and central regions as determined from enrichment of H3K9 methylation. The boundaries between chromosome arms and centers were determined by visual inspection, as the approximate midpoint of the transition region from high to low H3K9me enrichment (Supplemental Fig. S4).

Based on the patterns of H3K9 methylation (Fig. 2; Supplemental Fig. S3), we estimated the physical boundaries between the arms and central region of each chromosome (Fig. 3C). These coordinates agree well with the traditional definitions of the arms and central regions based on recombination rates (Barnes et al. 1995; Rockman and Kruglyak 2009). Consistent with the enrichment pattern of repressive H3K9me marks, genes on the arm regions show lower expression than those in the central regions (the average mRNA abundance of arm genes compared to genes in the chromosome centers was 1.4-fold lower in early embryos and 1.6-fold lower in L3s) (data not shown). However, there are well-expressed genes present on the arms, and gene profile plots show that they have distributions of active and repressive marks that are similar to the distributions on highly expressed genes in chromosome centers (Supplemental Fig. S5). These findings suggest that the gene expression environment on the arms is not analogous to that of classical heterochromatic domains, in which genes show distinct histone modification landscapes (Yasuhara and Wakimoto 2008). Consistent with this, some of the repressive domains, such as the left arm of Chr I, contain regions rich in active marks (Fig. 2; Supplemental Fig. S3). This observation suggests the broad repressive domains on the chromosome arms contain islands of active chromatin with robust gene expression potential. These transcriptionally active regions may correspond to the small chromatin loops recently proposed to emerge from the broad arm domains closely associated with the nuclear membrane (Ikegami et al. 2010).

Chr I and Chr III are more enriched for marks of transcriptionally active chromatin than other chromosomes, with Chr V and Chr X being the least enriched (Fig. 2). Gene expression profiling correlated with these findings: Chr I and Chr III have the most genes in the top quintile of expression and the fewest genes in the bottom quintile, while Chr V and Chr X have the fewest genes in the top quintile, and Chr V has the most genes in the bottom quintile (Supplemental Fig. S6A). Notably, Chr I and Chr III are especially enriched for genes that are ubiquitously expressed across worm stages and tissue types (Supplemental Fig. S6B,C) and for essential genes (Kamath et al. 2003).

We conclude, based on comparative analysis of histone marks and chromatin factors, that C. elegans chromosomes are organized into broad domains that differentiate the center of the chromosomes from the arms. Nuclear envelope association and the presence of repressive marks are the major features of the arms. In addition, the X chromosome exhibits specialized architecture, likely related to dosage compensation, which is discussed below.

Distinct dosage compensation and repressive histone marks on the X chromosome

In addition to the broad chromatin domains, a striking feature observed in the whole-chromosome views is the X-chromosome enrichment of factors in Group C, containing the dosage compensation proteins (Fig. 2). The C. elegans dosage compensation complex is loaded onto the X chromosomes at the 30–40-cell stage of embryogenesis to down-regulate gene expression from the two X chromosomes in hermaphrodite somatic cells by about half, to match gene expression levels from the single X chromosome in males (Meyer 2005). To complement the whole-chromosome view, we compared the enrichment profiles of dosage compensation factors and histone marks on X-linked genes versus autosomal genes, to identify possible associations between marks and X-chromosome repression (Fig. 4; Supplemental Fig. S2). The dosage compensation components DPY-26, DPY-27, and MIX-1 illustrate the already documented enrichment on X-linked genes, both in the high- and low-expression categories, relative to autosomal genes. Almost all histone marks show at least a subtle X versus autosome difference that is consistent with repression of genes on the X, with marks of activity often more enriched on autosomal genes and marks of repression more enriched on X-chromosome genes. Two marks, H4K20me1 and H3K27me1, show a profound difference between X and autosomal genes.

Figure 4.

Profiles of factors on X-linked and autosomal genes in the top and bottom expression bins. Average signal profiles in the 2 kb around transcript start sites (TSS) and transcript termination sites (TTS) are shown for selected factors (see Supplemental Fig. S2 for complete set) on four groups of genes: autosomal genes in the top 10% and bottom 10% of expression and X-linked genes in the top 10% and bottom 10% of expression. The top two rows are marks associated with active gene expression; the next two rows are marks associated with repression; the bottom row is components involved in dosage compensation.

H4K20me1 is more enriched on the transcribed regions of highly expressed X-linked genes compared to those on autosomes (Fig. 4). In L3s, enrichment of H4K20me1 is elevated compared to embryos and is even observed across silent genes. H3K27me1 signal shows strong enrichment on highly expressed X-linked genes in early embryos, but much weaker enrichment in L3s (Fig. 4). The distinct changes in X enrichment of H3K27me1 and H4K20me1 between early embryos and L3s suggest different roles for these two modifications. It is possible that H3K27me1 enrichment is related to germline repression of the X chromosomes (Reinke et al. 2004), as features of germline chromatin persist into early embryos (Rechtsteiner et al. 2010). On the other hand, H4K20me1 may be related to somatic dosage compensation, which starts in early embryos and is fully established in L3s. H4K20me1 has been implicated in gene repression in Drosophila and human cells and is known to be associated with X inactivation in mouse cells (Nishioka et al. 2002; Kohlmaier et al. 2004; Congdon et al. 2010). In humans, both H3K27me1 and H4K20me1 are found on actively transcribed regions (Barski et al. 2007). The intriguing possibilities that X-enriched H4K20me1 and/or H3K27me1 are involved in regulating X-linked gene expression are currently being explored.

Among the marks of active chromatin, H3K4me3, H3K79me3, and H3K27ac are similar between X-linked and autosomal genes in early embryos; relatively small differences exist in L3s. In contrast, H3K36me3 levels are significantly lower on highly expressed X-linked than autosomal genes at both stages. Given the association between H3K4me3 and RNA Pol II initiation and between H3K36me3 and RNA Pol II elongation, one possibility is that high H3K4me3 and low H3K36me3 on X genes in early embryos reflects efficient RNA Pol II initiation but failure to elongate. However, RNA Pol II profiles do not support the notion of paused RNA Pol II preferentially on X-linked genes (Supplemental Fig. S2). In-depth analysis in early embryos suggests instead that low H3K36me3 on X-linked genes reflects the distributions and activities of the two H3K36 histone methyltransferases, MES-4 and MET-1 (Rechtsteiner et al. 2010). MES-4, which can catalyze H3K36 methylation independently of RNA Pol II, associates preferentially with autosomal genes (Bender et al. 2006; Rechtsteiner et al. 2010). MET-1, which is presumed to depend on RNA Pol II like other H3K36 histone methyltransferases, can methylate genes on the X but is present at low levels in early embryos (Furuhashi et al. 2010; Rechtsteiner et al. 2010). The elevated H3K36me3 on highly expressed autosomal genes in L3s has not been similarly investigated, but may also be due to the autosome-concentrated activity of MES-4.

In summary, comparison of the X chromosome to the autosomes highlighted previously known features associated with dosage compensation and additionally points to potential roles for new features, such as H4K20me1, in differential regulation of genes on the X relative to autosomal genes.

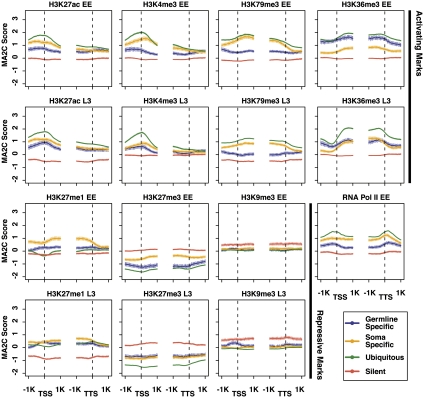

Histone marks on genes with different temporal–spatial patterns of expression

The above analyses explored differences in histone mark distributions by stage (early embryo and L3 larvae), chromosome (the five autosomes and the X), and expression level (top and bottom 10% of RNA accumulation). To investigate histone marks on genes expressed in different tissues, we categorized genes based on temporal and spatial expression data (Meissner et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2009; Rechtsteiner et al. 2010) (Methods). “Ubiquitous genes” (2580 in total) are expressed across different stages and tissues, whereas “silent genes” (415) include serpentine receptors that are not expressed in most stages and tissue types. These sets of genes are expected to be regulated similarly across cell types. We also examined two sets of genes that have spatially different expression: “germline-specific genes” (169) are expressed in the adult germline but not in isolated muscle, nerve, and intestine, while “soma-specific genes” (323) are expressed in isolated muscle, nerve, or intestinal tissue, but not in the adult germline. Since we are not yet able to ChIP from individual tissues, we reasoned that analysis of the patterns of histone modifications on genes expressed in a tissue-specific manner would likely be informative.

Ubiquitous genes generally show the highest levels of active chromatin marks and the lowest levels of repressive marks, in both early embryos and L3s, while silent genes generally show the reciprocal pattern (Fig. 5). Germline-specific and soma-specific genes generally have levels of active and repressive marks intermediate between the levels on ubiquitous and silent genes, possibly reflecting the fact that they are regulated differently in different tissues and that only a fraction of the cells in the extracts contribute to signal. A clear exception is H3K27me1, which is higher on both soma and germline genes than on ubiquitously expressed or inactive genes in early embryos and L3s (Fig. 5). This might indicate a role for H3K27me1 in tissue-specific gene expression. Also of note is that the H3K27me1 enrichment pattern groups with repressive marks in early embryos and with active marks in L3s (Fig. 1).

Figure 5.

Profiles of factors on genes with different spatial–temporal expression. Average signal profiles in the 2 kb around transcript start sites (TSS) and transcript termination sites (TTS) are shown for selected factors on four categories of genes: ubiquitously expressed genes, silent genes (genes encoding serpentine receptors), genes expressed specifically in somatic tissues, and genes expressed specifically in the maternal adult germline. The top two rows are marks associated with active gene expression; the bottom two rows are marks associated with repression.

The relative enrichment patterns of particular histone marks on germline-specific and soma-specific genes show interesting trends (Fig. 5). In early embryos, germline-specific genes are not being actively transcribed, while transcription of soma-specific genes is being newly activated (Baugh et al. 2003). Consistent with that, marks associated with ongoing gene expression, including RNA Pol II, H3K4me3, and H3K79me3, are higher on soma-specific genes than germline-specific genes. But surprisingly, the active mark H3K36me3 is significantly higher on germline-specific genes than soma-specific genes. As noted above, in-depth comparative analysis has revealed that H3K36me3 marks are propagated on germline-specific genes by the MES-4 histone methyltransferase in the absence of ongoing transcription (Furuhashi et al. 2010; Rechtsteiner et al. 2010). Consistent with the notion that germline-specific genes retain at least one mark of active chromatin (H3K36me3) in early embryos, these genes have very low levels of the repressive mark H3K27me3.

In L3s, germline- and soma-specific genes show very similar levels of enrichment for most marks analyzed (Fig. 5). This is consistent with L3s containing actively transcribing germline and somatic tissues and generating histone modifications mainly in conjunction with ongoing gene expression and with common regulation of chromosome organization. The notable exception is H3K79me3, which in both L3s and early embryos is significantly higher on soma-specific genes than germline-specific genes. We hypothesize that the histone methyltransferase(s) responsible for H3K79 methylation might be differently regulated in the germline and soma.

Conclusion

C. elegans is a powerful model system for studying genome and chromatin organization, as well as understanding gene regulation in biological processes and diseases. As part of the modENCODE Consortium, we present a comparative map of histone modifications and chromatin factors across different chromosomes, gene sets, and developmental stages. Our study yielded many unexpected observations, the most striking being the organization of C. elegans chromosomes into broad chromatin domains. This study represents an initial analysis of this rich data collection. With the data publicly available to the community, we expect that further analysis will yield new biological insights and additional surprises.

Methods

Antibodies

The antibodies used in this study are summarized in Supplemental Table S1. All antibodies against histone modifications were tested for specificity by Western and/or dot blot analysis (Antibody Validation Database, http://compbio.med.harvard.edu/antibodies/). For an antibody to pass Western blot analysis, the histone band in C. elegans nuclear extract constituted at least 50% of the total nuclear signal, was at least 10-fold more intense than any other single nuclear band, and was at least 10-fold more intense than the signal on recombinant, unmodified histone. For an antibody to pass dot blot analysis required that at least 75% of the total signal be specific to the cognate peptide. Mouse monoclonal antibodies against H3K9me2 (clone 6D11), H3K9me3 (clone 2F3), H3K27me3 (clone1E7), H3K36me2 (2C3), and H3K36me3 (13C9) were gifts from Hiroshi Kimura (Osaka University) (Kimura et al. 2008). Other antibodies against histone modifications are available commercially: mouse monoclonal antibodies against H3K4me2 (Wako 308-34809), H3K4me3 (Wako 305-34819), H3K27ac (Wako 306-34949), and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against H3K4me1 (Abcam ab8895), H3K4me3 (LP Bio AR-0169), H3K9me1 (Abcam ab9045), H3K27ac (Abcam ab4729), H3K27me1 (Upstate 07-448), H3K36me1 (Abcam ab9048), H3K79me1 (Abcam 2886), H3K79me2 (Abcam 3594), H3K79me3 (Abcam ab2621), H4K8ac (Abcam ab15823), H4K16ac (Millipore 07-329), H4 tetra-ac (LP Bio AR-0109), and H4K20me1 (Abcam ab9051). Antibodies against chromatin-associated proteins include RNA Pol II (Abcam ab0817), LEM-2 (SDI SDQ3891) (Ikegami et al. 2010), MES-4 (SDI SDQ0791) (Rechtsteiner et al. 2010), SDC-3 and DPY-27 (Ercan et al. 2007), DPY-26 and MIX-1 (Ercan et al. 2009), and HTZ-1 (Whittle et al. 2008). DPY-28 antibody was kindly provided by Kirsten Hagstrom.

Preparation of extracts and ChIP experiments

Extracts were prepared from N2 (wild-type) embryos and L3 larvae as described previously: early embryo (EE) extracts (Rechtsteiner et al. 2010), mixed embryo (MxE) extracts (Ercan et al. 2007), and L3 extracts (Kolasinska-Zwierz et al. 2009). Eight different matched EE extracts (containing an average of 37% <28-cell embryos, 30% 28–100-cell embryos, and 33% ∼100–300-cell embryos), seven different matched MxE extracts, and four different matched L3 extracts were prepared. Each ChIP experiment was done in at least two different extracts. ChIP experiments performed in this study are summarized in Supplemental Table S1. ChIP experiments were done and samples amplified using Ligation-Mediated PCR (LM-PCR) as previously described: EE ChIPs (Rechtsteiner et al. 2010); MxE ChIPs for SDC-3, DPY-27, and LEM-2 (Ercan et al. 2007); DPY-26, DPY-28, and MIX-1 (Ercan et al. 2009); HTZ-1 (Whittle et al. 2008); and L3 ChIPs (Kolasinska-Zwierz et al. 2009).

ChIP-chip microarray processing

The detection platform was NimbleGen Custom 2.1M Tiling arrays, with 50-mer probes, tiled every 50 bp for the WS170 (ce4) genome build, providing even and almost gap-free coverage across the whole C. elegans genome. Amplified samples were labeled, hybridized, and scanned at the Roche NimbleGen Research and Development Laboratory. Most ChIP samples were labeled with Cy5 and their input reference with Cy3 following the methods described in Selzer et al. (2005). Compared to ChIP-seq, ChIP-chip offers faster sample processing time and more accurate fold enrichment estimate, although less detection sensitivity and lower resolution.

ChIP-chip analysis

Accession numbers for all ChIP-chip experiments are in Supplemental Table S1. Supplemental material is available online at http://www.genome.org. ChIP-chip data were analyzed by MA2C algorithm (Song et al. 2007). First, probes were grouped based on their GC content, then the log2 ratios of probes between ChIP and input control within each group were normalized to a standard normal distribution using a robust mean variance method. A window sliding process was conducted across the whole genome, and the MA2C score was calculated as the median normalized log2 ratio among all probes in all replicates within a 600-bp window. All the experiments reported here were verified by at least two replicates performed from different chromatin extracts with a replicate correlation >0.6 across the genome. One exception was H4K20me1, which had a correlation of 0.58 between early embryo replicates, due to low signals of H4K20me1 in EE and its restriction to Chr X; replicates of H4K20me1 in EE did show consistent peaks and troughs in the Integrative Genome Browser (Supplemental Fig. S1; Nicol et al. 2009). The other exception was DPY-28, which had a correlation of 0.40. Its replicates were obtained from microarrays with different designs and had a dye swap, but displayed similar peaks of enrichment, especially on Chr X (data not shown).

Cluster and heatmap analyses

Groups of ChIP factors with similar genome-wide signals (Fig. 1) were determined using the hclust (complete linkage) function in R, with pairwise correlation coefficients (calculated using the cor [Pearson] function) as the similarity measure (The R Development Core Team 2009). Correlation coefficients were calculated using median values over 1-kb windows. Repeat density was calculated from all repeat annotations, including simple repeats, tandem repeats, and various types of transposable elements, from WormBase WS187 (lifted over to WS170). Repeat density and gene density, obtained from WormBase WS170 (coding genes only), were square-root-transformed, then normalized to a standard normal distribution. RNA-seq data for early embryo and L3, obtained from the Waterston lab via the modENCODE DCC (http://intermine.modencode.org/release-18/objectDetails.do?id=246001841 and id=246001910), were logarithm-transformed and then standardized to Z-scores. MA2C scores were used for all ChIP-chip data. The same median normalized data were used for the chromosome-wide heatmap display of ChIP-chip data, repeat density, gene density, and RNA-seq (Fig. 2).

H3K9me regions and arm boundary determination

One-kilobase windows were called as enriched for H3K9 methylation if their median me1, me2, or me3 value was over one standard deviation above the genome-wide mean. The boundaries between chromosome arms and centers were determined by visual inspection, as the approximate midpoint of the transition region from high to low H3K9me enrichment (Supplemental Fig. S4).

Aggregate gene profile plots

Aggregate profile plots were generated by aligning genes at their transcript start site (TSS) and transcript termination site (TTS), based on WormBase 170. For genes with multiple transcripts, the longest transcript was chosen. Genomic regions 1 kb upstream to 1 kb downstream from the TSS and TTS were divided into 40 50-bp bins each. Average MA2C scores of groups of genes were assigned to each bin as described in CEAS (Shin et al. 2009). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals of the mean of all the probe values in the respective bin. Profiles around pairing center motifs were obtained similarly.

Definition of gene sets with different spatial–temporal expression patterns

Gene classes were defined based on expression data, as described previously (Rechtsteiner et al. 2010). In brief, “ubiquitous” or housekeeping genes have transcripts (at least 1 tag) present in muscle, gut, neuron, and adult germline SAGE (Serial Analysis of Gene Expression) data sets (Meissner et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2009). “Silent” serpentine receptor genes are expressed in only a few mature neurons (Kolasinska-Zwierz et al. 2009). “Germline-specific” genes are expressed exclusively in the maternal germline, as their transcripts are present in the germline (Reinke et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2009), maternally loaded into embryos (Baugh et al. 2003), and absent from muscle, gut, and neuron SAGE data sets (Meissner et al. 2009). “Soma-specific” genes are expressed in muscle, gut, and neuron SAGE data sets (Meissner et al. 2009) but not in the adult germline (Reinke et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2009).

Transcriptional profiling

RNA was isolated from four early embryo and four L3 preparations used for ChIP, using Trizol and purified using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, catalog 74104). Samples were analyzed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer to ensure that rRNAs were not degraded and that RNA was free of protein and DNA contamination. Some samples were treated with DNase for 30 min at room temperature. Twenty micrograms of each RNA was hybridized to a single-color 4-plex NimbleGen expression array with 72,000 probes (three 60-mer oligo probes per gene). Quantile normalization (Bolstad et al. 2003) and the Robust Multichip Average (RMA) algorithm (Irizarry et al. 2003) were used to normalize and summarize the multiple probe values per gene to obtain one expression value per gene and sample. The expression values per gene were averaged across the four samples.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hiroshi Kimura and Kirsten Hagstrom for antibodies. C. elegans was provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota), which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources. This research is supported by modENCODE grant U01 HG004270 to the modENCODE consortium headed by J.D.L., with J.A., A.D., A.F.D., A.L.I., X.S.L., and S.S. as co-investigators.

Authors' contributions: T.L., A.R., M.C., H.S., and S.T. performed bioinformatics analysis; T.A.E., A.V., I.L., S.E., K.I., M.J., P.K., H.R., and T.T. performed ChIP-chip and expression experiments; and A.L.I., A.D., A.F.D., J.D.L., J.A., S.S., and X.S.L. were Project Directors.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article. The data in this paper are available online from the modENCODE Data Coordination Center website (http://intermine.modencode.org/). Accession numbers for all ChIP-chip experiments are in Supplemental Table S1.]

Article published online before print. Article, supplemental material, and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.115519.110.

References

- Albertson DG, Thomson JN 1982. The kinetochores of Caenorhabditis elegans. Chromosoma 86: 409–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertson DG, Rose AM, Villeneuve AM 1997. Chromosome organization mitosis, and meiosis. In C. elegans II (ed. Riddle DL et al. ), pp. 47–78 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TM, Kohara Y, Coulson A, Hekimi S 1995. Meiotic recombination, noncoding DNA and genomic organization in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 141: 159–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K 2007. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129: 823–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh LR, Hill AA, Slonim DK, Brown EL, Hunter CP 2003. Composition and dynamics of the Caenorhabditis elegans early embryonic transcriptome. Development 130: 889–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender LB, Suh J, Carroll CR, Fong Y, Fingerman IM, Briggs SD, Cao R, Zhang Y, Reinke V, Strome S 2006. MES-4: an autosome-associated histone methyltransferase that participates in silencing the X chromosomes in the C. elegans germ line. Development 133: 3907–3917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP 2003. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19: 185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: A platform for investigating biology. Science 282: 2012–2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congdon LM, Houston SI, Veerappan CS, Spektor TM, Rice JC 2010. PR-Set7-mediated monomethylation of histone H4 lysine 20 at specific genomic regions induces transcriptional repression. J Cell Biochem 110: 609–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercan S, Giresi PG, Whittle CM, Zhang X, Green RD, Lieb JD 2007. X chromosome repression by localization of the C. elegans dosage compensation machinery to sites of transcription initiation. Nat Genet 39: 403–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercan S, Dick LL, Lieb JD 2009. The C. elegans dosage compensation complex propagates dynamically and independently of X chromosome sequence. Curr Biol 19: 1777–1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuhashi H, Takasaki T, Rechtsteiner A, Li T, Kimura H, Checchi PM, Strome S, Kelly WG 2010. Trans-generational epigenetic regulation of C. elegans primordial germ cells. Epigenetics Chromatin 3: 15 doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-3-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein MB, Lu ZJ, Van Nostrand EL, Cheng C, Arshinoff BI, Tao L, Yip KY, Robilotto R, Rechtsteiner A, Ikegami K, et al. 2010. Integrative analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome by the modENCODE Project. Science 330: 1775–1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Maures TJ, Hauswirth AG, Green EM, Leeman DS, Maro GS, Han S, Banko MR, Gozani O, Brunet A 2010. Members of the H3K4 trimethylation complex regulate lifespan in a germline-dependent manner in C. elegans. Nature 466: 383–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu SG, Fire A 2009. Partitioning the C. elegans genome by nucleosome modification, occupancy, and positioning. Chromosoma 119: 73–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenatri M, Bailly D, Maison C, Almouzni G 2004. Mouse centric and pericentric satellite repeats form distinct functional heterochromatin. J Cell Biol 166: 493–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SE, Beverly M, Russ C, Nusbaum C, Sengupta P 2010. A cellular memory of developmental history generates phenotypic diversity in C. elegans. Curr Biol 20: 149–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami K, Egelhofer T, Strome S, Lieb JD 2010. C. elegans chromosome arms are anchored to the nuclear membrane via discontinuous association with LEM-2. Genome Biol. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-12-r120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP 2003. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4: 249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jans J, Gladden JM, Ralston EJ, Pickle CS, Michel AH, Pferdehirt RR, Eisen MB, Meyer BJ 2009. A condensin-like dosage compensation complex acts at a distance to control expression throughout the genome. Genes Dev 23: 602–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, et al. 2003. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421: 231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Hayashi-Takanaka Y, Goto Y, Takizawa N, Nozaki N 2008. The organization of histone H3 modifications as revealed by a panel of specific monoclonal antibodies. Cell Struct Funct 33: 61–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmaier A, Savarese F, Lachner M, Martens J, Jenuwein T, Wutz A 2004. A chromosomal memory triggered by Xist regulates histone methylation in X inactivation. PLoS Biol 2: E171 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolasinska-Zwierz P, Down T, Latorre I, Liu T, Liu XS, Ahringer J 2009. Differential chromatin marking of introns and expressed exons by H3K36me3. Nat Genet 41: 376–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T 2007. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128: 693–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KK, Gruenbaum Y, Spann P, Liu J, Wilson KL 2000. C. elegans nuclear envelope proteins emerin, MAN1, lamin, and nucleoporins reveal unique timing of nuclear envelope breakdown during mitosis. Mol Biol Cell 11: 3089–3099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen AJ, Phillips CM, Bhalla N, Weiser P, Villeneuve AM, Dernburg AF 2005. Chromosome sites play dual roles to establish homologous synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Cell 123: 1037–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox PS, Oegema K, Desai A, Cheeseman IM 2004. “Holo”er than thou: Chromosome segregation and kinetochore function in C. elegans. Chromosome Res 12: 641–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens JH, O'Sullivan RJ, Braunschweig U, Opravil S, Radolf M, Steinlein P, Jenuwein T 2005. The profile of repeat-associated histone lysine methylation states in the mouse epigenome. EMBO J 24: 800–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner B, Warner A, Wong K, Dube N, Lorch A, McKay SJ, Khattra J, Rogalski T, Somasiri A, Chaudhry I, et al. 2009. An integrated strategy to study muscle development and myofilament structure in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 5: e1000537 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer BJ 2005. X-chromosome dosage compensation. WormBook 2005: 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer BJ 2010. Targeting X chromosomes for repression. Curr Opin Genet Dev 20: 179–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J, Verrijzer P 2009. Biochemical mechanisms of gene regulation by Polycomb group protein complexes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 19: 150–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol JW, Helt GA, Blanchard SG Jr, Raja A, Loraine AE 2009. The Integrated Genome Browser: free software for distribution and exploration of genome-scale datasets. Bioinformatics 25: 2730–2731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka K, Rice JC, Sarma K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Werner J, Wang Y, Chuikov S, Valenzuela P, Tempst P, Steward R, et al. 2002. PR-Set7 is a nucleosome-specific methyltransferase that modifies lysine 20 of histone H4 and is associated with silent chromatin. Mol Cell 9: 1201–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi SL, Henikoff JG, Henikoff S 2009. A native chromatin purification system for epigenomic profiling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nucleic Acids Res 38: e26 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng JC, Karpen GH 2008. Epigenetic regulation of heterochromatic DNA stability. Curr Opin Genet Dev 18: 204–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters AH, Kubicek S, Mechtler K, O'Sullivan RJ, Derijck AA, Perez-Burgos L, Kohlmaier A, Opravil S, Tachibana M, Shinkai Y, et al. 2003. Partitioning and plasticity of repressive histone methylation states in mammalian chromatin. Mol Cell 12: 1577–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CM, Dernburg AF 2006. A family of zinc-finger proteins is required for chromosome-specific pairing and synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Dev Cell 11: 817–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CM, Wong C, Bhalla N, Carlton PM, Weiser P, Meneely PM, Dernburg AF 2005. HIM-8 binds to the X chromosome pairing center and mediates chromosome-specific meiotic synapsis. Cell 123: 1051–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CM, Meng X, Zhang L, Chretien JH, Urnov FD, Dernburg AF 2009. Identification of chromosome sequence motifs that mediate meiotic pairing and synapsis in C. elegans. Nat Cell Biol 11: 934–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prachumwat A, DeVincentis L, Palopoli MF 2004. Intron size correlates positively with recombination rate in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 166: 1585–1590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The R Development Core Team 2009. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: http://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/refman.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rechtsteiner A, Ercan S, Takasaki T, Phippen TM, Egelhofer TA, Wang W, Kimura H, Lieb JD, Strome S 2010. The histone H3K36 methyltransferase MES-4 acts epigenetically to transmit the memory of germline gene expression to progeny. PLoS Genet 6: e1001091 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke V, Gil IS, Ward S, Kazmer K 2004. Genome-wide germline-enriched and sex-biased expression profiles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 131: 311–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockman MV, Kruglyak L 2009. Recombinational landscape and population genomics of Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 5: e1000419 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Isaac B, Phillips CM, Rillo R, Carlton PM, Wynne DJ, Kasad RA, Dernburg AF 2009. Cytoskeletal forces span the nuclear envelope to coordinate meiotic chromosome pairing and synapsis. Cell 139: 907–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaner CE, Kelly WG 2006. Germline chromatin. WormBook 2006: 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer RR, Richmond TA, Pofahl NJ, Green RD, Eis PS, Nair P, Brothman AR, Stallings RL 2005. Analysis of chromosome breakpoints in neuroblastoma at sub-kilobase resolution using fine-tiling oligonucleotide array CGH. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 44: 305–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H, Liu T, Manrai AK, Liu XS 2009. CEAS: cis-regulatory element annotation system. Bioinformatics 25: 2605–2606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JS, Johnson WE, Zhu X, Zhang X, Li W, Manrai AK, Liu JS, Chen R, Liu XS 2007. Model-based analysis of two-color arrays (MA2C). Genome Biol 8: R178 doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger DJ, Lefterova MI, Ying L, Stonestrom AJ, Schupp M, Zhuo D, Vakoc AL, Kim JE, Chen J, Lazar MA, et al. 2008. DOT1L/KMT4 recruitment and H3K79 methylation are ubiquitously coupled with gene transcription in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol 28: 2825–2839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zang C, Rosenfeld JA, Schones DE, Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Peng W, Zhang MQ, et al. 2008. Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nat Genet 40: 897–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhao Y, Wong K, Ehlers P, Kohara Y, Jones SJ, Marra MA, Holt RA, Moerman DG, Hansen D 2009. Identification of genes expressed in the hermaphrodite germ line of C. elegans using SAGE. BMC Genomics 10: 213 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle CM, McClinic KN, Ercan S, Zhang X, Green RD, Kelly WG, Lieb JD 2008. The genomic distribution and function of histone variant HTZ-1 during C. elegans embryogenesis. PLoS Genet 4: e1000187 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara JC, Wakimoto BT 2008. Molecular landscape of modified histones in Drosophila heterochromatic genes and euchromatin-heterochromatin transition zones. PLoS Genet 4: e16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]