Abstract

Protein kinase C (PKC) is a multigene family of serine/threonine kinases. PKC is involved in regulating adrenal and gonadal steroidogenesis; however, the functional relevance of the different PKC isoenzymes remains obscure. In this study, we demonstrate that MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells express several PKC isoforms to varying levels and that the activation of PKC signaling, by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) elevated the expression and phosphorylation of PKCα, -δ, -ε, and -μ/protein kinase D (PKD). These responses coincided with the expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein and progesterone synthesis. Targeted silencing of PKCα, δ, and ε and PKD, using small interfering RNAs, resulted in deceases in basal and PMA-mediated StAR and steroid levels and demonstrated the importance of PKD in steroidogenesis. PKD was capable of controlling PMA and cAMP/PKA-mediated synergism involved in the steroidogenic response. Further studies pointed out that the regulatory events effected by PKD are associated with cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and c-Jun/c-Fos-mediated transcription of the StAR gene. Chromatin immunoprecipitation studies revealed that the activation of phosphorylated CREB, c-Jun, and c-Fos by PMA was correlated with in vivo protein-DNA interactions and the recruitment of CREB-binding protein, whereas knockdown of PKD suppressed the association of these factors with the StAR promoter. Ectopic expression of CREB-binding protein enhanced the trans-activation potential of CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos in StAR gene expression. Using EMSA, a −83/−67-bp region of the StAR promoter was shown to bind PKD-transfected MA-10 nuclear extract in a PMA-responsive manner, targeting CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos proteins. These findings provide evidence for the presence of multiple PKC isoforms and demonstrate the molecular events by which selective isozymes, especially PKD, influence PMA/PKC signaling involved in the regulation of the steroidogenic machinery in mouse Leydig cells.

The functional relevance of PKCμ/PKD isoenzyme in the regulation of StAR expression and steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig cells is discussed.

Protein kinase C (PKC), a family of widely expressed serine/threonine kinases, is activated by a number of extracellular signals and has been implicated in regulating numerous signaling networks, including those involved in differentiation, membrane trafficking, secretion, and gene expression (1,2,3,4). Molecular cloning, to date, has characterized multiple distinct PKC isoforms that are subdivided into three groups based on their structural features and activating cofactor requirements (5,6). As such, conventional PKCs (designated as α, β, and γ) are activated by diacylglycerol (DAG), phosphatidylserine and calcium (Ca2+) signaling. Novel isoforms (δ, ε, θ, and η) are regulated by DAG and phosphatidylserine and do not require Ca2+ for kinase activity. Both conventional and novel PKCs possess a tandem repeat of zinc finger-like cysteine-rich motifs in their regulatory domain that confers phospholipid-dependent phorbol ester and DAG binding. On the other hand, atypical PKC isoforms (λ, ζ, and ι) require phospholipid for activation and do not bind phorbol esters. All of these PKCs possess a highly conserved catalytic domain (1,5).

PKCμ/protein kinase D (PKD) is considered as a fourth subgroup of serine/threonine protein kinase with homology to conventional PKC isoforms in the regulatory domain, whereas a catalytic domain exhibits a low degree of sequence similarity to other PKCs (5,7,8). Importantly, PKD contains additional protein modules, including the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, which is not present in any of the PKCs and has been shown to play a vital role in kinase regulation (9,10,11). In fact, PKD, together with two other members, PKD2 and PKD3/PKDν, represents a distinct family of protein kinases (5,7). PKD binds phorbol esters and DAG with high affinity. PKD is autophosphorylated on a serine residue (Ser916 and Ser910 in murine and human, respectively), and this phosphorylation event essentially determines the activation state of this kinase (12,13).

The rate-limiting and regulated step in steroid hormone biosynthesis is the transfer of cholesterol from the outer to the mitochondrial inner membrane, a process mediated by the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) in steroidogenic tissues (14,15,16,17,18,19,20). Regulation of the StAR protein is mediated by multiple signaling events, including the PKA and PKC pathways, and involves transcriptional and posttranslational activation in the adrenal glands and gonads (reviewed in Refs. 18 and 21,22,23). Noteworthy, whereas PKC-mediated induction of steroid synthesis is remarkably low compared with PKA signaling, it modulates gonadotropin and/or cAMP/PKA-stimulated steroidogenic responsiveness (24,25,26) and thus may play important roles in various adrenal and gonadal steroidogenic functions. Transcription of the StAR gene is influenced by multiple DNA regulatory elements, including cAMP response-element (CRE)-binding protein (CREB)/CRE modulator and activator protein-1 (AP-1, Fos/Jun) (18,23,27,28). CREB-binding protein (CBP) and its functional homolog, p300, are transcriptional coactivators, which interact with a variety of transcription factors and thus play critical roles in gene regulation (23,29).

The biochemical and physiological significance of various PKC isoforms remains poorly understood. Generally, most PKCs are found in a wide variety of mammalian tissues. The differential expression of PKCs in several tissues suggests that distinct PKC isoforms may be independently regulated, respond to discrete ligands, and perform distinct cellular functions. Likewise, it has been demonstrated that PKCs are associated with a number of biological processes, including corpus luteum formation (2,30), growth and development of breast cancer (31), mitogenesis and angiogenesis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma (32,33), and the male reproductive system (4,34). In mouse testis/Leydig cells, previous studies have detected conventional and novel isoforms, namely PKCα, -δ, -γ, -ε, and -θ, by Northern and immunohistochemical analyses (4,34,35). Given the importance of the StAR protein in steroidogenesis and to better understand the link between PKCs and testicular function, studies demonstrating the precise role of PKC(s) in regulating Leydig cell steroidogenic function are warranted. Using MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells (a cell line that closely resembles its normal counterpart and has been widely used in studying physiological functions) as an in vitro model, the present studies provide evidence for the presence of a number of previously undetected PKC isoforms, notably PKD, and demonstrate the functional relevance of selective isoenzymes in the regulation of PKC/phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) signaling involved in StAR expression and steroidogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Cells, plasmids, transfections, and luciferase assays

MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells (36) were cultured in HEPES-buffered Waymouth MB/752 medium supplemented with 15% horse serum containing antibiotics, as described previously (37,38).

The 5′-flanking −151/−1-bp region of the mouse StAR promoter was synthesized using a PCR-based cloning strategy and inserted into the Xho1 and HindIII cloning sites of the pGL3 basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI) that contains firefly luciferase as a reporter gene (39,40,41). The pRL-SV40 plasmid containing the Renilla luciferase gene driven by SV40 promoter was obtained from Promega. Expression plasmids used for wild-type (WT) and mutant PKCs, CREB, CBP, c-Jun, and c-Fos have been previously described (37,39,42,43,44). All clones were verified by restriction mapping and confirmed by automated sequencing on a PE Biosystems 310 genetic analyzer (ABI PRISM 310; PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) at the Texas Tech University Biotechnology Core Facility.

For promoter analysis, MA-10 cells were cultured in either 12- or six-well plates to 65–75% confluency and transfected using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN) under optimized conditions (26,37). In brief, the −151/−1 StAR reporter plasmid was transfected with WT CREB, c-Jun/c-Fos, CBP, and mutant PKC expression plasmids (1:1). Transfection efficiency was normalized by cotransfecting 10–20 ng pRL-SV40 vector. The amount of DNA used in transfections was equalized with pcDNA3.1 empty expression vector (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

Transfection with PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) was performed using X-tremeGENE siRNA transfection reagent (Roche), using the procedures described previously (38,41). Silencer negative control, and the PKCα (no. 1, 5′-GCAACCAUCCAACAACCUG-3′, and no. 2, 5′-CGUUCAAAUUAAAACCUUC-3′), PKCδ (no. 1, 5′-CAGAGUCUGUCGGAAUAUA-3′, and no. 2, 5′-GAUUCAAGGUUUAUAACUA-3′), PKCε (no. 1, 5′-CCAAAAGAGAUGUCAAUAA-3′, and no. 2, 5′-GCACUUGCGUUGUCCACAA-3′), and PKD (no. 1, 5′-CAGCGAAUGUAGUGUAUUA-3′, and no. 2, 5′-GGAUGUGGUCUGAAUUACC-3′) specific siRNAs were obtained as annealed oligos (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX). The siRNAs were transfected using final concentrations ranging from 50–100 nm, as specified in the figure legends.

Luciferase activity in the cell lysates was determined by the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega), as described previously (37,39). Briefly, cells were washed with 0.01 m PBS, and 250–300 μl of the lysis buffer was added to the plates. After centrifugation, the supernatant was measured for relative light units using a TD 20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA).

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting studies were carried out using total cellular protein (25,26,41). Equal amounts of total protein (20–30 μg) were solubilized in sample buffer and loaded onto either 8 or 10% SDS-PAGE (Mini Protean II System; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). After electrophoresis, the proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto Immuno-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad), which were then probed with the specific antibodies (Abs) that recognize PKCα, phospho (P)-PKCα (Thr638), PKCδ, P-PKCδ (Thr505), PKCε, PKCμ, P-PKD (Ser916), CREB, P-CREB (Ser133), c-Jun, and P-c-Jun (Ser73) (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA); P-PKCε (Ser729), CBP (sc-7300), and c-Fos (sc52) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); P-c-Fos (Biosource International Inc., Camarillo, CA); total StAR (45); P-StAR (25); β-actin (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX); and CYP11A1 (Chemicon International Inc., Temecula, CA). The incubation with primary Abs was carried out overnight at 4 C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with appropriate secondary Abs for 1 h and washed again, and immunodetection of proteins was determined with the Chemiluminescence Imaging Western Lightning Kit (PerkinElmer). The membranes were exposed to x-ray films (Marsh Bio Products Inc., Rochester, NY) and the intensity of immunospecific bands was quantified using a computer-assisted image analyzer (Visage 2000; BioImage, Ann Arbor, MI). Detection of different proteins was assessed using identically processed membranes; however, where appropriate, the same membranes were also analyzed by stripping and reprobing with different Abs.

Real-time PCR and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from different treatment groups using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc.-BRL, Grand Island, NY). Semiquantitative real-time PCR was employed for determining StAR and GAPDH cDNAs, as described previously (46,47). The following oligos were used as primers and probes: StAR (forward), 5′-CCGGGTGGATGGGTCAA-3′; StAR (reverse), 5′-CACCTCTCCCTGCTGGATGTA-3′; StAR (TaqMan), 5′-CGACGTCGGAGCTCTCTGCTTGG-3′; GAPDH (forward), 5′-GCAGTGGCAAAGTGGAGATTG-3′; GAPDH (reverse), 5′-GTGAGTGGAGTCATACTGGAACATG-3′; and GAPDH (TaqMan), 5′-TCAACGACCCCTTCATTGACCTC-3′. The expression of the StAR gene was normalized against GAPDH using the comparative cycle threshold method (46,47).

The expression of different PKC isoforms was analyzed using a quantitative RT-PCR under optimized conditions (25,41). The primers used for amplifying different mouse PKC isoform cDNAs are provided in Supplemental Table 1 (published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). The variation in RT-PCR efficiency was assessed with the L19 ribosomal protein gene as an internal control, using the following primer pairs: forward, 5′-GAAATCGCCAATGCCAACTC-3′, and reverse, 5′-TCTTAGACCTGCGAGCCTCA-3′ (25,41). RT and PCR were run sequentially in the same assay tube using 2 μg total RNA. The molecular sizes of different PKC isoforms (Supplemental Table 1) and L19 (405 bp) were determined on 1% agarose gels, which were vacuum dried and exposed to x-ray films (Marsh Bio Products) for 1–5 h. Relative levels of PKC isoforms and L19 were quantified using the Visage 2000 image analysis system.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assays were carried out following the manufacturer’s instructions (Upstate/Chemicon, Temecula, CA), as described previously (26,44). Briefly, cells were incubated with formaldehyde (1%) for 10 min at 37 C to cross-link DNA and its associated proteins. Cells were then collected and resuspended in lysis buffer and sonicated for nine cycles of 10-sec pulses using a Tekmar Sonic Disruptor (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The supernatant containing chromatin was cleared with protein A-agarose/salmon sperm DNA 50% slurry for 30 min at 4 C with agitation. After centrifugation, the supernatant was immunoprecipitated with 4–5 μg of Abs specific to P-CREB, P-c-Jun, P-c-Fos, and CBP (as above) for 16 h at 4 C and followed by incubation with protein A-agarose/salmon sperm for an additional 1 h. IgG was used as a negative control. The chromatin-antibody-protein A-agarose complexes were washed sequentially with low-salt, high-salt, LiCl, and Tris/EDTA buffers and eluted with an elution buffer (1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1 m NaHCO3). NaCl (5 m) was added to the eluate that was then incubated at 65 C for 4 h to reverse the formaldehyde cross-linking. The resulting samples were treated with 0.5 m EDTA, 1 m Tris-Hcl (pH 6.5) and proteinase K for 1 h at 45 C, and the purified DNA samples were amplified by PCR. PCR was performed with 75–100 ng DNA and the proximal mouse StAR promoter primers (forward, 5′-CTGGTCCTCCCTTTACACAGTC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GGCGCAGATCCAGTGCGCTGC-3′), spanning bases −170/−149 and −21/−1, respectively (38,44). PCR products were determined on 2% agarose gels. Gels were vacuum dried and exposed to x-ray films (Marsh Bio Products), and the resulting signals were analyzed (Visage 2000).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

EMSA experiments were carried out using nuclear extracts (NE) obtained from PKD-transfected MA-10 cells under optimized conditions (37,41,44). The sense strand of the oligonucleotide used was −83/−67 bp, 5′-GGAATGACTGATGACTTTT-3′. The probe was engineered and synthesized by heating sense and antisense primers to 65 C for 5 min in annealing buffer [10 mm Tris-HCl, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA (pH 7.5)]. The doubled-stranded oligonucleotide was end-labeled with [α32P]dCTP using Klenow fill-in reaction, and DNA-protein binding assays were performed (41,44). Briefly, NE (10–15 μg) was incubated with CREB, c-Jun, and c-Fos Abs for 45 min on ice in a 20-μl reaction buffer [25 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA, 4% Ficoll, 10 mm dithiothreitol, 2 μg poly deoxyinosine-deoxycytidine, 40 ng/μl BSA, and 12 mm MgCl2 (pH 7.9)]. The 32P-labeled probe was then added to the mixture, and the incubation was continued for an additional 15 min at room temperature. The reaction mixture was then subjected to electrophoresis on 5% polyacrylamide gels, which were dried and exposed to x-ray films, and the resulting signals were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated three to seven times. Statistical analysis was performed by either Student’s t test or ANOVA followed by Fisher’s protected least significant differences test using the StatView (Abacus Concepts Inc., Berkeley, CA). Results presented are the mean ± se, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Detection of PKC isoforms and their roles in steroidogenesis in MA-10 cells

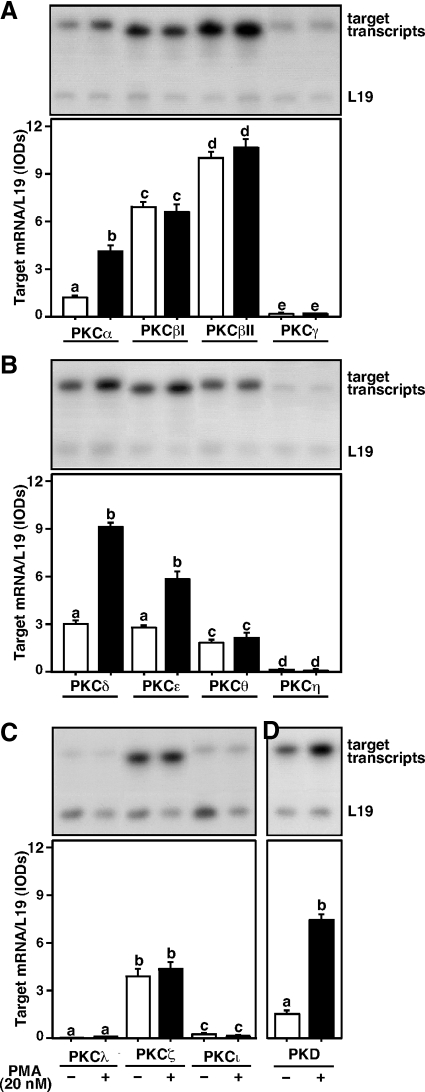

The expression of conventional (Fig. 1A), novel (Fig. 1B), atypical (Fig. 1C), and PKD (Fig. 1D) PKC isoforms was determined employing a quantitative RT-PCR approach. Treatment of MA-10 cells with a PKC activator, PMA (20 nm), for 6 h resulted in 2.5 ± 0.4-, 2.9 ± 0.3-, 2.3 ± 0.4-, and 4.2 ± 0.5-fold increases in PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD mRNAs over untreated cells, respectively. Under similar experimental paradigms, PMA had no apparent effects on PKCβI, -βII, -θ, and -ζ mRNA levels. Alternatively, basal expression of PKCγ, -η, -λ, and -ι mRNAs were virtually undetectable and were unresponsive to PMA. Because PMA significantly increased (P < 0.05) PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD mRNAs, their roles in steroidogenesis were evaluated in subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Detection of various PKC isoforms in MA-10 cells. Cells were treated without (white bar) or with (black bar) 20 nm PMA for 6 h and subjected to isolation of total RNA for determining relative expression of different PKC isoforms by RT-PCR analysis. Representative autoradiograms illustrate expression of PKCα, -βI, -βII, and -γ (A); PKCδ, -ε, -θ, and -η (B); PKCλ, -ζ, and -ι (C); and PKD (D) in control and stimulated groups. L19 expression was assessed as loading controls. Integrated OD (IOD) values of each band were quantified, normalized with the corresponding L19 bands, and presented as target mRNA/L19. Data represent the mean ± se of four independent experiments. Letters above the bars indicate that these groups differ significantly from each other at least at P < 0.05.

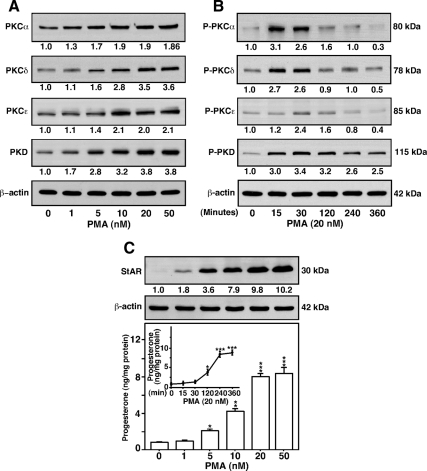

MA-10 cells treated with PMA demonstrated both enhanced expression and phosphorylation of PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 2). In particular, PMA (0–50 nm, 6 h) demonstrated 1.9 ± 0.3-, 3.5 ± 0.5-, 2.1 ± 0.3-, and 3.8 ± 0.4-fold increases in PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD protein levels over their respective basal levels, when compared at optimal stimulating doses (20–50 nm) (Fig. 2A). The results presented in Fig. 2B show that phosphorylation (P) of PKCα (Thr638), -δ (Thr505), and -ε (Ser729) in response to PMA was maximally induced between 15 and 30 min, decreased thereafter with time, and fell below control levels by 360 min. In parallel, the optimal activation of P-PKD was observed by 15–30 min, slightly decreased thereafter, but remained elevated over basal at 360 min. PMA was found to increase StAR protein expression in a dose-responsiv manner, demonstrating a maximum of 10.2 ± 0.9-fold over basal (Fig. 2C). However, PMA had no detectable effect on P-StAR (data not shown) (24,26). Dose- and time-dependent (inset) increases in PMA-mediated expression/phosphorylation of PKCα, -δ, and -ε, PKD, and StAR were maximally associated with a 4.9 ± 1.1-fold induction in progesterone synthesis over basal (1.6 ± 0.3 ng/mg protein) (Fig. 2C). In fact, the modest elevation in progesterone secretion, concomitant with a marked increase in StAR protein expression, by PMA, was likely due to the involvement of a StAR phosphorylation-independent event in steroid synthesis.

Figure 2.

Effect of PMA on expression and phosphorylation of PKCα, -δ, and -ε, PKD, StAR, and progesterone synthesis. MA-10 cells were treated either with increasing (0–50 nm, 6 h) or with a fixed (20 nm, 0–360 min) dose of PMA and subjected to preparation of cellular protein for immunoblotting. Representative immunoblots show expression (A) and phosphorylation (B) of PKCα, -δ, and -ε, PKD, and StAR (C) in different groups using 25–30 μg of total protein. The average integrated ODs for different PKC isoforms and StAR were normalized to those of β-actin for each treatment. The fold change of these values is presented below the blots relative to unstimulated cells. Results are representative of four to seven independent experiments. C, The levels of progesterone in media, obtained with either varying doses or different time points (inset) in response to PMA, were determined and expressed as nanograms per milligram protein (n = 4, ±se). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. control.

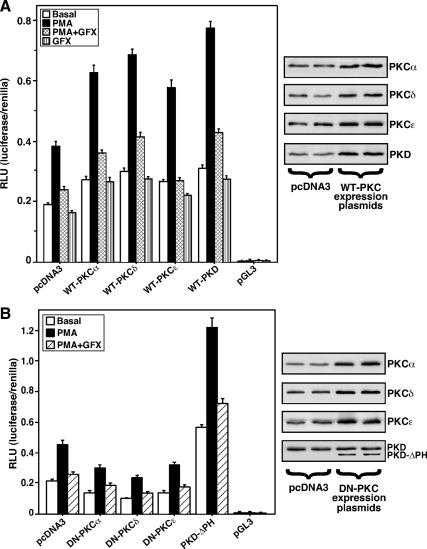

Functional assessment of the roles of PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD in the steroidogenic response

The impact that PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD have on PMA-mediated StAR expression and steroidogenesis was elucidated by overexpression and silencing studies. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, MA-10 cells transfected with the −151/−1-bp StAR reporter segment in the presence of WT PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD expression plasmids demonstrated PMA-mediated increases in luciferase activity by 2- to 3-fold over the responses seen with mock-transfected (pcDNA3) cells. The use of the −151/−1-bp StAR segment was based on previous findings (26,41). Cells pretreated with a PKC inhibitor GF-10923X (GFX, 20 μm) (26,48) for 30 min diminished (P < 0.05) PMA-induced StAR promoter responsiveness. The results obtained with WT PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD overexpression were further assessed using a dominant-negative (DN) mutant strategy. Cells transfected with DN PKCα, -δ, and -ε isoforms, which bind and inhibit their activity, diminished basal StAR promoter responsiveness by 48–67% but did not affect PMA-induced activity (Fig. 3B). In contrast, StAR reporter activity was significantly augmented (P < 0.01) in cells expressing a PKD-ΔPH mutant lacking the PH domain, when compared with pcDNA3 and WT PKD-transfected cells, suggesting the PH domain plays an inhibitory role in StAR gene expression. The protein levels after overexpression of the different WT and DN PKC isoforms was assessed by immunoblotting (in duplicates) and demonstrated increased levels (P < 0.05) of these isoenzymes over their respective pcDNA3-transfected controls (Fig. 3, A and B, right panels).

Figure 3.

Roles of PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD isoforms in PMA mediated StAR promoter responsiveness. MA-10 cells were transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3), WT (A), and DN (B) mutants of PKCα, -δ, or -ε or a PKD mutant lacking the PH domain (PKD-ΔPH), within the context of the −151/−1 StAR luciferase reporter segment, in the presence of pRL-SV40, as described in Materials and Methods. pGL3 basic (pGL3) was used as a control. After 36 h of transfection, cells were pretreated without or with PKC inhibitor GFX (20 μm) for 30 min and then treated for 6 h in the absence (basal) or presence of PMA (20 nm), PMA plus GFX, and GFX, as indicated. After 36 h of transfection, cells were also determined for protein levels by Western blotting. Representative immunoblots (n = 3) illustrate expression (in duplicates) of different WT and DN PKC isoforms in control (pcDNA3) and PKC-overexpressing cells (A and B, right panels). Luciferase activity in the cell lysates was determined and expressed as relative light units (RLU, luciferase/renilla). Data represent the mean ± se of five independent experiments.

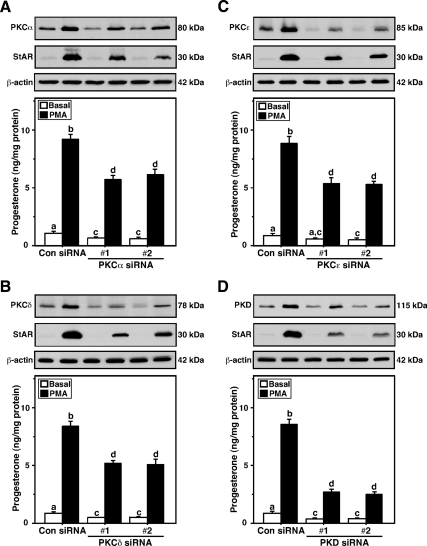

The roles of PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD in steroidogenesis were further evaluated by the silencing of these isoforms in MA-10 cells. Cells transfected with 100 nm of either of two (no. 1 and no. 2) PKCα (Fig. 4A), -δ (Fig. 4B), and -ε (Fig. 4C) and PKD (Fig. 4D) specific siRNAs (see Materials and Methods) decreased endogenous protein levels between 70 and 90% when compared with respective negative control siRNAs. The decreased levels of these PKCs were associated with 38–66% reduction in basal and PMA-mediated StAR expression and progesterone synthesis (Fig. 4). In particular, knockdown results demonstrated that PKD profoundly affected both StAR and steroid levels, indicating that this isoenzyme is largely involved in steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig cells.

Figure 4.

Silencing of PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD isoenzymes in MA-10 cells and its consequences on StAR expression and steroid synthesis. Cells were transfected with either a negative control siRNA (Con siRNA) or two different (no. 1 and no. 2) PKCα (A), -δ (B), and -ε (C) and PKD (D) specific siRNAs at 100 nm concentration each, as described in Materials and Methods. After 48 h of transfection, cells were treated without (basal) or with PMA (20 nm) for an additional 6 h, and cells were subjected to cellular protein preparation for immunoblotting. Representative immunoblots illustrate expression of PKCα, -δ, and -ε, PKD, and StAR in different treatment groups using 20–30 μg of total protein. β-Actin expression was assessed as loading controls. Immunoblots are representative of five to seven independent experiments. C, Accumulation of progesterone in media of different treatment groups was determined (n = 5, ±se) and expressed as nanograms per milligram protein. Letters above the bars indicate that these groups differ significantly from each other at least at P < 0.05.

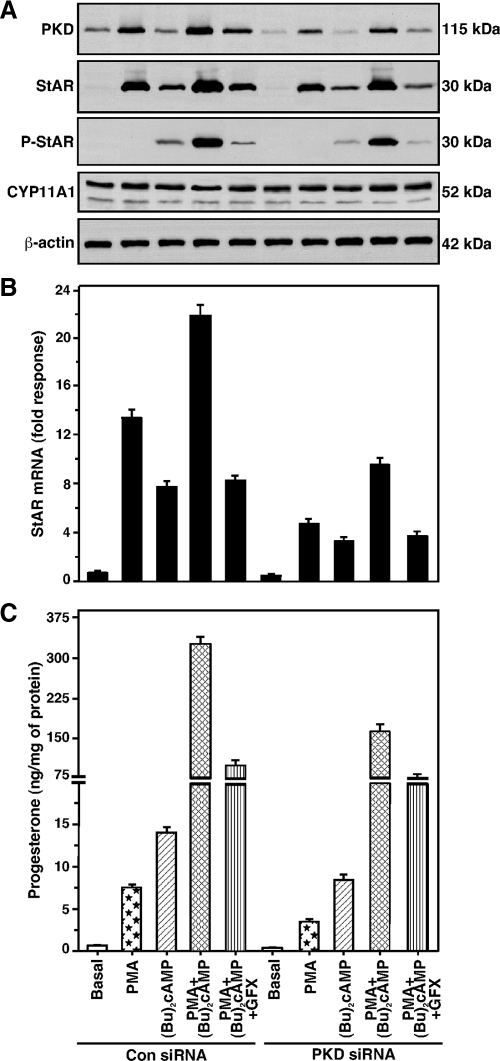

PKC can modulate the activity of cAMP/PKA signaling involved in StAR expression and steroid synthesis (24,26); thus, it was of interest whether PKD could influence cAMP responsiveness. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the combined effects of PMA and dibutyryl cAMP [(Bu)2cAMP, 0.1 mm] in PKD, StAR, P-StAR, StAR mRNA, and progesterone levels were significantly decreased (P < 0.05) in PKD-deficient MA-10 cells (transfected with 50 nm of each siRNA, 100 nm total). Whereas PKD knockdown diminished StAR protein and progesterone levels, it had no effect on the expression of CYP11A1 protein. Under similar experimental conditions, treatments with PMA, (Bu)2cAMP, and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP were also demonstrated to have no apparent effects on CYP11A1 protein levels, indicating they elevate steroid synthesis without altering the expression of this enzyme. PMA and (Bu)2cAMP in combination resulted in a 2.7 ± 0.4-fold increase in PKD protein expression over PMA treatment alone. The combined effects of these agents also markedly increased StAR protein and P-StAR (Fig. 5A), StAR mRNA (Fig. 5B), and progesterone (Fig. 5C) levels. (Bu)2cAMP had no effect on expression of the PKD protein, but it significantly enhanced (P < 0.01) StAR expression and steroid synthesis (Fig. 5). Progesterone levels were augmented 4.5 and 14.6-fold by PMA and (Bu)2cAMP, respectively; however, their combination resulted in a 356 ± 24-fold increase in steroid synthesis, an effect that was concomitant with the elevation in P-StAR. This indicates that phosphorylation of StAR, in the presence of a low level of PKA activity [effected by the addition of (Bu)2cAMP], is critical for obtaining maximal cholesterol transferring activity in the regulation of steroid synthesis by PKC signaling. On the other hand, depletion of PKD affected (P < 0.01) both PMA- and PMA- plus (Bu)2cAMP-mediated responses, demonstrating the importance of PKD in controlling the combined effects of PKC and PKA signaling involved in steroidogenesis.

Figure 5.

Effect of PKD knockdown on PMA- and (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR, P-StAR, StAR mRNA, CYP11A1, and progesterone levels. MA-10 cells were transfected with either a negative control siRNA (Con siRNA) at 100 nm or a mixture of two PKD-specific siRNAs at 50 nm each (100 nm total, PKD siRNA). After 48 h of transfection, cells were pretreated without or with GFX (20 μm) for 30 min and then treated without or with PMA (20 nm), (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm), or a combination of them for 6 h, as indicated. Cells were then processed for either immunoblotting or real-time RT-PCR, as described in Materials and Methods. A, Representative immunoblots illustrate PKD, StAR, P-StAR, and CYP11A1 levels in different treatment groups using 25–30 μg of total cellular protein. β-Actin expression was assessed as a loading control in immunoblotting. B, Levels of StAR mRNAs of the same treatment groups were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Immunoblots and RT-PCR analyses are representative of four to six independent experiments. C, Accumulation of progesterone in media of the same groups was determined and expressed as nanograms per milligram protein (n = 4, ±se).

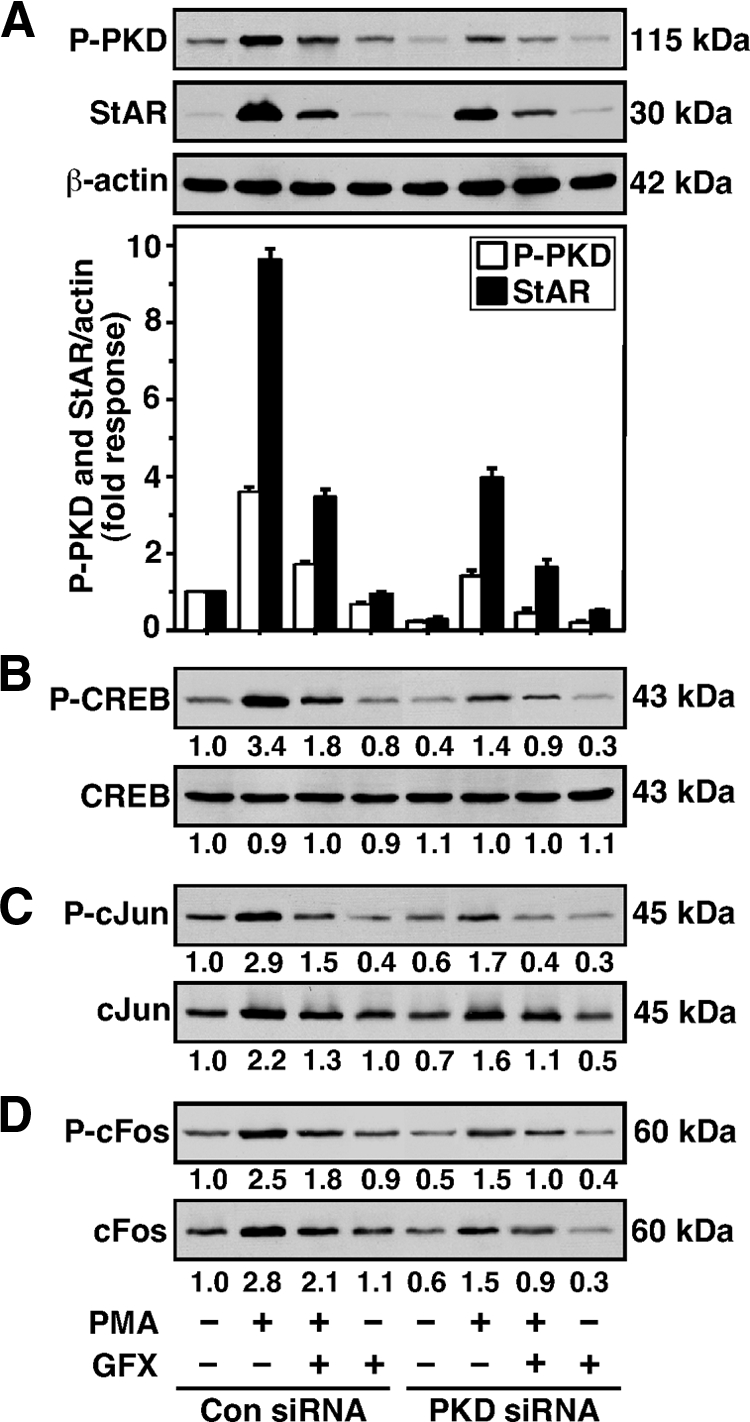

PKD signaling involves CREB- and c-Jun/c-Fos-mediated transcription of the StAR gene

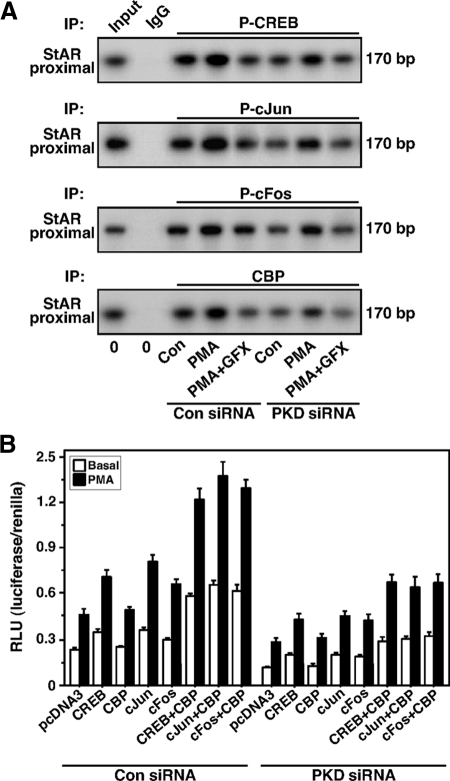

To obtain molecular insight into these mechanisms, the functional involvement of CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos in PKD signaling was assessed, because these transcription factors have been demonstrated to be instrumental in StAR gene transcription (23,28). MA-10 cells were transfected with either 100 nm of a negative control siRNA or 50 nm of two PKD (100 nm total) specific siRNAs (Fig. 6). Cells treated with PMA resulted in 3.6 and 9.8-fold increases in P-PKD and StAR levels, respectively, levels that were markedly affected in PKD-deficient cells (Fig. 6A). Alternatively, PMA showed a 3.4 ± 0.5-fold induction of P-CREB over untreated cells (Fig. 6B). The amounts of total CREB were unaltered by any of these treatments. Additionally, PMA enhanced P-c-Jun and c-Jun levels by 2.9 ± 0.3- and 2.2 ± 0.4-fold over respective basal values (Fig. 6C). Simultaneously, P-c-Fos (2.5 ± 0.4-fold) and c-Fos (2.8 ± 0.5-fold) levels were enhanced by PMA (Fig. 6D). GFX diminished (P < 0.05) PMA-induced PKD, StAR, P-CREB, P-c-Jun/c-Jun, and P-c-Fos/c-Fos responses. The silencing of PKD decreased expression/phosphorylation of CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos by 50–70%, and consequently StAR and steroid (not illustrated) levels, suggesting that inhibition of PKD affects CREB- and c-Jun/c-Fos-mediated StAR gene transcription.

Figure 6.

Silencing of PKD on StAR, CREB, c-Jun, and c-Fos levels in MA-10 cells. Cells were transfected with either a negative control (Con siRNA) or a mixture of two PKD siRNAs (PKD siRNA), as described in the legend of Fig. 5. After 48 h of transfection, cells were pretreated without or with GFX (20 μm) for 30 min, then treated in the absence or presence of PMA (20 nm) for 6 h, and then subjected to cellular protein preparation. Representative immunoblots illustrate P-PKD and StAR (A), P-CREB and CREB (B), P-c-Jun and c-Jun (C), and P-c-Fos and c-Fos (D) in different treatment groups, using 20–30 μg of total cellular protein. The average integrated ODs for P-PKD and StAR were normalized to those of β-actin for each treatment. Integrated OD values for P-CREB, CREB, P-c-Jun, c-Jun, P-c-Fos, and c-Fos were quantified. The fold changes of these values are reported for each treatment relative to the unstimulated control siRNA group. Compiled data from four experiments are presented in A (±se, lower panel). Immunoblots shown are representative of three to six independent experiments.

To determine whether knockdown of PKD suppresses the association of CREB, c-Jun, and c-Fos with the StAR promoter, ChIP studies were performed (Fig. 7A). Treatment with PMA resulted in 2.8 ± 0.4-, 2.1 ± 0.3-, 2.4 ± 0.4-fold increases in the association of P-CREB, P-c-Jun, and P-c-Fos with the proximal StAR promoter, respectively. The increased association of P-CREB, P-c-Jun, and P-c-Fos with the StAR promoter, by PMA, was reduced (P < 0.05) approximately 50% in PKD-knockdown MA-10 cells. GFX further affected PMA-induced association of these factors. No signal was observed with IgG. The association of CBP (1.9 ± 0.2-fold) in response to PMA was found to be qualitatively similar to those of P-CREB and P-c-Jun/P-c-Fos, demonstrating the physical interactions of P-CREB- and P-c-Jun/P-c-Fos-DNA in CBP recruitment to the StAR promoter. Interestingly, cells deficient in PKD significantly diminished (P < 0.01) PMA-mediated association of P-CREB, P-c-Jun, P-c-Fos, and CBP with the StAR promoter when compared with respective controls. The functional integrity of CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos in CBP recruitment was further evaluated in determining StAR promoter responsiveness. MA-10 cells transfected with wild-type CREB, c-Jun, and c-Fos expression plasmids, within the context of the −151/−1 StAR segment, demonstrated an approximately 2-fold increase over the responses seen in mock-transfected cells in StAR promoter activity in response to PMA (Fig. 7B). Ectopic expression of CBP further enhanced (P < 0.05) the trans-activation potential of both CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos in StAR gene expression. The efficacies of CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos in PMA-mediated trans-activation of the StAR gene were decreased by 50–64% in PKD-knockdown MA-10 cells. The latter event also reduced (P < 0.05) the trans-activating effect of CBP in CREB- and c-Jun/c-Fos-mediated StAR gene expression. In fact, the inhibition of endogenous PKD effectively weakens CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos responsiveness, affects recruitment of CBP to the StAR promoter, and results in trans-repression of the StAR gene.

Figure 7.

Effect of PKD knockdown on association of P-CREB, P-c-Jun, P-c-Fos, and CBP with the StAR promoter and its relevance to StAR gene expression. MA-10 cells were transfected with either a negative control (Con siRNA) or a mixture of two PKD siRNAs (PKD siRNA), as described in the legend of Fig. 5. After 48 h of transfection, cells were pretreated without or with GFX (20 μm) for 30 min and then treated in the absence or presence of PMA (20 nm) for an additional 30 min as indicated, and ChIP assays were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Cross-linked sheared chromatin obtained from different treatment groups was immunoprecipitated (IP) either with IgG or anti-P-CREB, anti-P-c-Jun, anti-P-c-Fos, and anti-CBP Abs. Recovered chromatin was subjected to PCR using the −170/−1-bp region of the StAR promoter. A, Representative autoradiograms illustrate the association of P-CREB, P-c-Jun, P-c-Fos, and CBP to the proximal StAR promoter. Data are representative of three to four independent experiments. B, Cells were transfected either with empty vector (pcDNA3), CREB, c-Jun, c-Fos, and CBP expression plasmids, or a combination of them as indicated, within the context of the −151/−1 StAR reporter segment in the presence of pRL-SV40. After 36 h of transfection, cells were treated in the absence (basal) or presence of PMA (20 nm) for an additional 6 h. Luciferase activity in the cell lysates was determined and expressed as relative light units (RLU, luciferase/renilla). Data represent the mean ± se of four independent experiments.

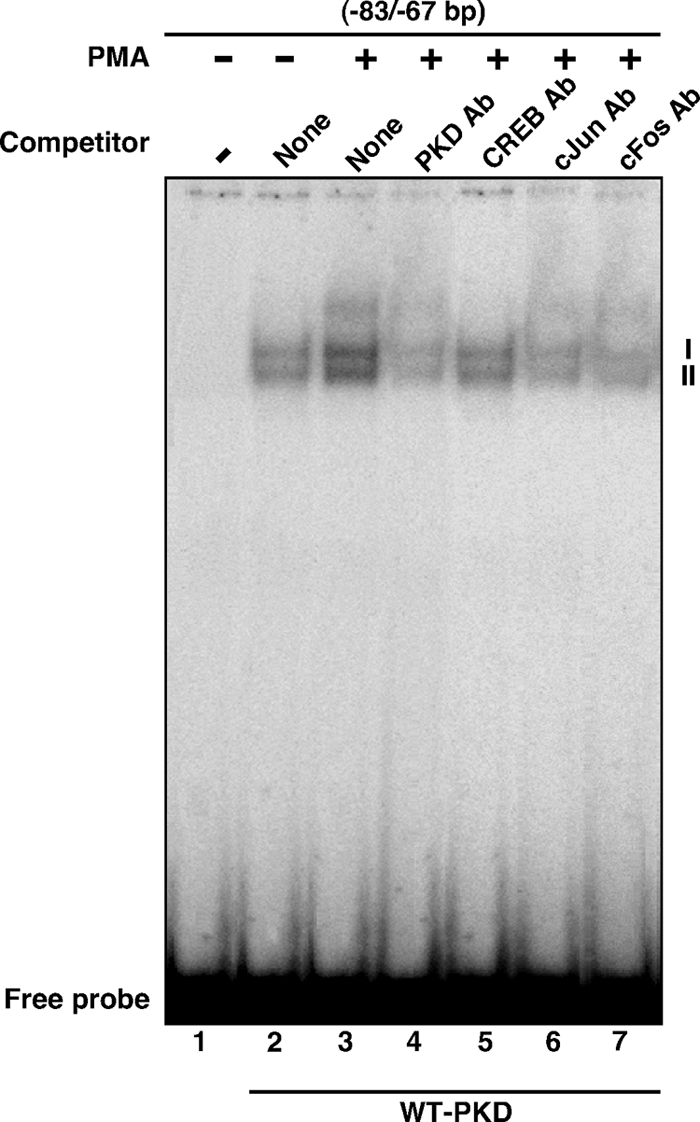

To better understand the involvement of CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos in PKD/PKC signaling, EMSA DNA-protein binding was carried out with WT PKD-transfected MA-10 NE, using an oligonucleotide probe (−83/−67 bp) that can recognize both CRE- and AP-1-binding proteins (23,26,28). As depicted in Fig. 8, a 32P-labeled probe demonstrated the formation of two major complexes (I and II) with NE obtained from untreated MA-10 cells (lane 2). Treatment with a low dose of PMA (10 nm) further enhanced (P < 0.01) DNA-protein binding (compare lanes 2 and 3). The increase in PMA-responsive DNA-protein binding was essentially abolished by PKD Ab (lane 4) or by an unlabeled oligoprobe (not illustrated). Additionally, DNA-protein complexes were markedly inhibited by CREB (lane 5), c-Jun (lane 6), and c-Fos (lane 7) Abs. The binding pattern was similar, but less abundant, with NE obtained from mock-transfected MA-10 cells (data not shown). These findings demonstrate that the molecular events involved in PKD-mediated regulation of StAR expression and steroidogenesis requires the functional association of CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos. Altogether, PKD appears to constitute a predominant endogenous isoenzyme involved in PMA/PKC-mediated regulation of the steroidogenic response in MA-10 mouse Leydig cells.

Figure 8.

Binding of MA-10 NE to the 83/−67-bp region of the StAR promoter, using EMSA. MA-10 cells were transfected with WT PKD expression plasmid. After 48 h of transfection, cells were treated without (lane 2) or with (lanes 3–7) 10 nm PMA for 6 h and then subjected to NE preparation. NEs (12–15 μg) obtained from different treatment groups were incubated with the 32P-labeled probe specific to the −83/−67-bp region of the StAR promoter. DNA-protein complexes (I and II) were challenged without (lanes 2 and 3) or with PKD (lane 4), CREB (lane 5), c-Jun (lane 6), and c-Fos (lane 7) Abs. Migration of free probes is shown for each lane. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

Regulation of Leydig cell steroidogenesis is predominantly mediated through the interaction of LH/hCG with its specific receptor that results in multiple intracellular modifications including the activation of cAMP-dependent PKA and the phosphorylation of proteins (18,49,50). Ligand-receptor interaction also activates phospholipase C and triggers the induction of the PKC pathway. PKC is a multigene family of Ser/Thr kinases and has been demonstrated to be involved in controlling several physiological functions, including steroidogenesis. We have reported that PKC modulates the activity of cAMP/PKA signaling and thus plays important roles in regulating StAR expression and steroid synthesis in gonadal tissues. The experimental approaches used in the present study extend these observations by elucidating the molecular events in which a number of isoenzymes, especially PKCμ/PKD, act to drive PKC/PMA signaling involved in regulating the steroidogenic machinery in mouse Leydig cells.

Screening of PKC isoforms and their roles in PMA-mediated steroidogenesis provide evidence that 1) MA-10 mouse Leydig cells primarily express PKCα, -βI, -βII, -δ, -ε, -θ, and -ζ and PKD isoforms to varying levels, 2) the induction of PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD expression and phosphorylation correlates with StAR expression and steroid synthesis, 3) the interference with expression of these PKCs affects the steroidogenic response, 4) PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD exhibit diverse effects on transcription of the StAR gene, 5) a constitutively active mutant of PKD is capable of enhancing StAR gene expression, and 6) regulation of PKD-dependent steroidogenesis potentially involves CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos functions. Previously, it has been demonstrated that testis/Leydig cells express PKCα, -δ, -γ, -ε, and -θ isoforms, and as a consequence, roles for these PKCs in spermatogenesis, spermatocyte protection, and fertilization have been proposed (4,34,35). Our current data demonstrate that MA-10 cells express a number of additional PKC isoenzymes and that PKCα, -δ, and -ε and PKD isoforms are involved in regulating PMA-mediated steroidogenesis.

A novel aspect to the present studies is the characterization of the role of PKD in the regulation of StAR expression and steroid synthesis. PKD, a distinct member of the PKC family, is induced by a wide variety of extracellular stimuli and functions in diverse regulatory events (8,51,52,53,54). The results presented here demonstrate that the activation of PKC signaling (by PMA) induced both the expression and phosphorylation (Ser916) of PKD, events that were associated with the steroidogenic response. Conversely, depletion of PKD protein suppressed both StAR and steroid levels but did not affect CYP11A1 expression. It has been demonstrated that PKCι enhances the transcriptional activity of CYP11A1 in JC-410 granulosa cells (55), suggesting tissue-specific effects of PKCs on different steroidogenic genes. In constitutively steroidogenic H295R human adrenocortical cells, angiotensin II-treated aldosterone and cortisol secretion correlates with the activation of PKD but not its expression (53). These indicate that regulation of PKD-dependent steroidogenesis in Leydig cells (by PMA) and adrenocortical cells (by angiotensin II) involves discrete mechanisms. However, this seeming contradiction could de due to differences in cell signaling specificity, effector-receptor coupling, and/or the involvement of unknown factor(s) involved in controlling StAR expression and steroidogenesis.

In view of our current data, it appears that the PKC isoform PKD, which plays an important role in controlling PMA/PKC signaling, is also involved in the PMA and cAMP/PKA-mediated regulation of the steroidogenic response. The inhibition of endogenous PKD was found to be effective in decreasing the combined effects of PMA and (Bu)2cAMP on StAR expression and progesterone synthesis. Whereas both PMA and (Bu)2cAMP increased StAR and steroid levels, they had no apparent effects on the expression of CYP11A1. Thus, these agents acutely increase cholesterol mobilization and delivery to the steroidogenic complex, resulting in enhanced progesterone production without increasing protein levels of CYP11A1, observations that are in agreement with trophic hormone- and/or cAMP-stimulated steroid synthesis in a number of gonadal and adrenal cells (38,56,57,58,59). Conversely, chronic stimulation of steroid biosynthesis has been demonstrated to increase the transcription of the steroidogenic genes, including CYP11A1 (60,61). Extracellular stimuli mediate PKD activation via PKC-dependent signaling (13,54,62); thus, it appears unlikely that PKD directly affects cAMP/PKA responsiveness. As a result, it is conceivable that PKD influences signaling cross talk between the PKC and PKA pathways. This hypothesis agrees with our observations demonstrating that both WT and constitutively active PKD-ΔPH plasmids were able to increase the combined effects of PMA and (Bu)2cAMP on StAR gene transcription (data not shown). Nonetheless, the roles of other factors that have been demonstrated to be sensitized to low levels of PKA (for example, Ca2+/K+ signaling and arachidonic acid) on StAR expression and steroid synthesis cannot be excluded (63,64). These findings reveal a novel connection between PKD and PKA signaling that may have important implications for a better understanding of signal transduction pathways in gonadal and adrenal cells.

A substantial body of evidence indicates that the PH domain of PKD plays a key role in kinase activation and function (9,11,43). Noteworthy, the PKD PH domain exhibits an autoinhibitory response in kinase activity, because mutant PKD proteins associated with partial deletions and/or amino acid substitutions within the PH domain have been shown to be constitutively active in cells (10,11). Use of a PKD-ΔPH mutant in the present study demonstrated increases in basal and PMA-mediated StAR promoter activity over the responses seen with WT PKD. This suggests that PKD exerts opposing effects in regulating StAR gene transcription. In support of this mechanism, constitutively active PKD plasmids displaying increased levels of aldosterone synthase and 11β-hydroxylase genes in H295R adrenocortical cells have been demonstrated (53). PKCs can bind to the PH domain of PKD, and a number of PKC isozymes have been reported to be upstream kinases of PKD that are capable of mediating PKD activation (11,65). These include PKCα and -ε (isoforms that are also involved in influencing steroidogenesis in the present study), which may contribute to conformational alterations that lead to differential effects on the PH domain. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that a balance between the inducer and repressor functions generated through the PH domain of PKD may allow for fine tuning events involved in regulating steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig cells.

The combinatorial action of several enhancer and silencer DNA regulatory elements (binding within the proximal −150-bp region of the mouse StAR promoter) constitute a family of transcription factors that function in the transcriptional regulation of the StAR gene (reviewed in Ref. 23). Transcriptional synergy requires the simultaneous interaction of multiple factors with CBP/p300 or relevant coactivators involved in the communication between transcription factors and the basal transcriptional machinery (29,44,66). In the present study, we observed that the regulation of PKD-dependent steroidogenesis, in conjunction with PKC signaling, is tightly linked with CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos actions. The relevance of these factors in PKD signaling was verified by three independent approaches demonstrating that alteration/inhibition of PKD markedly affected the steroidogenic response. First, expression/phosphorylation of PKD was found to be coordinately associated with CREB- and c-Jun/c-Fos-mediated StAR gene transcription. Second, in vivo ChIP data revealed that the activation of P-CREB, P-c-Jun, and P-c-Fos by PMA was concurrent with that of CBP, indicating the physical interaction of P-CREB- and P-c-Jun/P-c-Fos-DNA in CBP recruitment to the StAR promoter. Studies have demonstrated that phosphorylation of CREB at Ser133 is a prerequisite for its interaction with CBP (67). On the other hand, Jun and Fos phosphorylation have been shown to have inverse actions in DNA binding and gene expression, suggesting a complex relationship between phosphorylation and function (44,68). Third, a transcription factor-rich region of the StAR promoter specifically binds to MA-10 NE in a PKD/PMA-responsive manner and that DNA-protein binding was markedly affected by CREB, c-Jun, and c-Fos Abs, indicating nuclear proteins recognized by this region were essentially the CRE and AP-1 family proteins. In addition, CBP was found to increase the efficacies of CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos in PMA-induced transcription of the StAR gene, and the responses were effectively suppressed under conditions of PKD deficiency, demonstrating that CBP acts as an integrator among diverse signaling pathways. In accordance with this, CBP/p300 has been shown to modulate the activity of CREB, Fos/Jun, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β, and GATA-4 and plays integral roles in regulating transcription of a number of genes including StAR (23,44,66,69). Taken together, the activation of PKD/PKC signaling by PMA triggers phosphorylation of CREB and c-Jun/c-Fos, which results in interaction of these factors with CBP/p300 and subsequent modulation of their trans-activation potential involved in the regulation of StAR expression and steroid biosynthesis in mouse Leydig cells. The eventual effects of PKCα, -δ, and -ε in steroidogenesis may involve regulatory events similar to those of PKD and will require additional investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. A. Toker (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) and A. R. Brasier (The University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX) for the generous gifts of wild-type and mutant PKD and CBP expression plasmids, respectively. We also thank Dr. W. L. Miller (University of California, San Francisco, CA) for the gift of StAR Ab. The technical assistance of Ms. Yuping Sun is acknowledged.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HD-17481 and with funds from the Robert A. Welch Foundation Grant B1–0028.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Abbreviations: Ab, Antibody; AP-1, activator protein-1; CBP, CREB-binding protein; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CRE, cAMP response element; CREB, CRE-binding protein; DAG, diacylglycerol; DN, dominant negative; GFX, GF-109203X; NE, nuclear extract; P, phospho; PH domain, pleckstrin homology domain; PKC, protein kinase C; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; (Bu)2cAMP, dibutyryl cAMP; StAR, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein; siRNA, small interfering RNA; WT, wild type.

First Published Online November 3, 2010

References

- Nishizuka Y 1995 Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. FASEB J 9:484–496 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CA, Maizels ET, Hunzicker-Dunn M 1999 Activation of PKCδ in the rat corpus luteum during pregnancy. Potential role of prolactin signaling. J Biol Chem 274:37499–37505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker PJ, Murray-Rust J 2004 PKC at a glance. J Cell Sci 117:131–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, Zhang J, Gasana V, Fu W, Liu Y, Zong Z, Yu B 2005 Differential expression of protein kinase C alpha and delta in testes of mouse at various stages of development. Cell Biochem Funct 23:415–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde AM, Sinnett-Smith J, Van Lint J, Rozengurt E 1994 Molecular cloning and characterization of protein kinase D: a target for diacylglycerol and phorbol esters with a distinctive catalytic domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:8572–8576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niino YS, Irie T, Takaishi M, Hosono T, Huh N, Tachikawa T, Kuroki T 2001 PKCθII, a new isoform of protein kinase C specifically expressed in the seminiferous tubules of mouse testis. J Biol Chem 276:36711–36717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes FJ, Prestle J, Eis S, Oberhagemann P, Pfizenmaier K 1994 PKCμ is a novel, atypical member of the protein kinase C family. J Biol Chem 269:6140–6148 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lint J, Rykx A, Maeda Y, Vantus T, Sturany S, Malhotra V, Vandenheede JR, Seufferlein T 2002 Protein kinase D: an intracellular traffic regulator on the move. Trends Cell Biol 12:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias T, Rozengurt E 1998 Protein kinase D activation by mutations within its pleckstrin homology domain. J Biol Chem 273:410–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz P, Döppler H, Johannes FJ, Toker A 2003 Tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase D in the pleckstrin homology domain leads to activation. J Biol Chem 278:17969–17976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron RT, Rozengurt E 2003 Protein kinase C phosphorylates protein kinase D activation loop Ser744 and Ser748 and releases autoinhibition by the pleckstrin homology domain. J Biol Chem 278:154–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SA, Rozengurt E, Cantrell D 1999 Characterization of serine 916 as an in vivo autophosphorylation site for protein kinase D/protein kinase Cμ. J Biol Chem 274:26543–26549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SA, Iglesias T, Rozengurt E, Cantrell D 2000 Spatial and temporal regulation of protein kinase D (PKD). EMBO J 19:2935–2945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark BJ, Wells J, King SR, Stocco DM 1994 The purification, cloning, and expression of a novel luteinizing hormone-induced mitochondrial protein in MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells. Characterization of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR). J Biol Chem 269:28314–28322 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Sugawara T, Strauss JF 3rd, Clark BJ, Stocco DM, Saenger P, Rogol A, Miller WL 1995 Role of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in adrenal and gonadal steroidogenesis. Science 267:1828–1831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocco DM, Clark BJ 1996 Regulation of the acute production of steroids in steroidogenic cells. Endocr Rev 17:221–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson LK, Strauss 3rd JF 2000 Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and the intramitochondrial translocation of cholesterol. Biochim Biophys Acta 1529:175–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Stocco DM 2005 Regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression: functional and physiological consequences. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord 5:93–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WL 2007 StAR search–what we know about how the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein mediates mitochondrial cholesterol import. Mol Endocrinol 21:589–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Dyson MT, Stocco DM 2009 Regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene expression: present and future perspectives. Mol Hum Reprod 15:321–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson LK, Strauss 3rd JF 2001 Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein: an update on its regulation and mechanism of action. Arch Med Res 32:576–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocco DM, Wang X, Jo Y, Manna PR 2005 Multiple signaling pathways regulating steroidogenesis and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression: more complicated than we thought. Mol Endocrinol 19:2647–2659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Dyson MT, Stocco DM 2009 Role of basic leucine zipper proteins in transcriptional regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol 302:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo Y, King SR, Khan SA, Stocco DM 2005 Involvement of protein kinase C and cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependent kinase in steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression and steroid biosynthesis in Leydig cells. Biol Reprod 73:244–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Chandrala SP, King SR, Jo Y, Counis R, Huhtaniemi IT, Stocco DM 2006 Molecular mechanisms of insulin-like growth factor-I mediated regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in mouse Leydig cells. Mol Endocrinol 20:362–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Huhtaniemi IT, Stocco DM 2009 Mechanisms of protein kinase C signaling in the modulation of 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-mediated steroidogenesis in mouse gonadal cells. Endocrinology 150:3308–3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Wang XJ, Stocco DM 2003 Involvement of multiple transcription factors in the regulation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene expression. Steroids 68:1125–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yivgi-Ohana N, Sher N, Melamed-Book N, Eimerl S, Koler M, Manna PR, Stocco DM, Orly J 2009 Transcription of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in the rodent ovary and placenta: alternative modes of cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate dependent and independent regulation. Endocrinology 150:977–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo N, Goodman RH 2001 CREB-binding protein and p300 in transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem 276:13505–13508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A, Choudhary E, Inskeep EK, Flores JA 2005 Effects of selective protein kinase c isozymes in prostaglandin2α-induced Ca2+ signaling and luteinizing hormone-induced progesterone accumulation in the mid-phase bovine corpus luteum. Biol Reprod 72:976–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam M, Krett NL, Maizels ET, Cutler Jr RE, Peters CA, Smith LM, O'Brien ML, Park-Sarge OK, Rosen ST, Hunzicker-Dunn M 1999 Regulation of protein kinase C delta by estrogen in the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. Mol Cell Endocrinol 148:109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavalle CR, George KM, Sharlow ER, Lazo JS, Wipf P, Wang QJ 24 May 2010 Protein kinase D as a potential new target for cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha S, Tanasanvimon S, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E 16 July 2010 Role of protein kinase D signaling in pancreatic cancer. Biochem Pharmacol 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HM, Jin E, Park ST, Kim JJ, Yoon HS, Oh YK, Oh KS, Chung YT 2000 Expression of protein kinase C genes in normal (+/+) and W mutant alleles (Wsh/Wsh, W/Wv) mice testes. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 22:91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batarseh A, Giatzakis C, Papadopoulos V 2008 Phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate acting through protein kinase Cε induces translocator protein (18-kDa) TSPO gene expression. Biochemistry 47:12886–12899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli M 1981 Characterization of several clonal lines of cultured Leydig tumor cells: gonadotropin receptors and steroidogenic responses. Endocrinology 108:88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Eubank DW, Stocco DM 2004 Assessment of the role of activator protein-1 on transcription of the mouse steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene. Mol Endocrinol 18:558–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Dyson MT, Jo Y, Stocco DM 2009 Role of dosage-sensitive sex reversal, adrenal hypoplasia congenita, critical region on the X chromosome, gene 1 in protein kinase A- and protein kinase C-mediated regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression in mouse Leydig tumor cells: mechanism of action. Endocrinology 150:187–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Dyson MT, Eubank DW, Clark BJ, Lalli E, Sassone-Corsi P, Zeleznik AJ, Stocco DM 2002 Regulation of steroidogenesis and the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein by a member of the cAMP response-element binding protein family. Mol Endocrinol 16:184–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Eubank DW, Lalli E, Sassone-Corsi P, Stocco DM 2003 Transcriptional regulation of the mouse steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene by the cAMP response-element binding protein and steroidogenic factor 1. J Mol Endocrinol 30:381–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Stocco DM 2008 The role of JUN in the regulation of PRKCC-mediated STAR expression and steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig cells. J Mol Endocrinol 41:329–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh JW, Weinstein IB 2003 Roles of specific isoforms of protein kinase C in the transcriptional control of cyclin D1 and related genes. J Biol Chem 278:34709–34716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz P, Doppler H, Toker A 2004 Protein kinase Cδ selectively regulates protein kinase D-dependent activation of NF-κB in oxidative stress signaling. Mol Cell Biol 24:2614–2626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Stocco DM 2007 Crosstalk of CREB and Fos/Jun on a single cis-element: transcriptional repression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene. J Mol Endocrinol 39:261–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose HS, Whittal RM, Baldwin MA, Miller WL 1999 The active form of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, StAR, appears to be a molten globule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:7250–7255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewski MP, Dyson MT, Manna PR, Stocco DM 2009 Involvement of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in gonadal steroidogenesis and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression. Reprod Fertil Dev 21:909–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson MT, Kowalewski MP, Manna PR, Stocco DM 2009 The differential regulation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein-mediated steroidogenesis by type I and type II PKA in MA-10 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 300:94–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Jo Y, Stocco DM 2007 Regulation of Leydig cell steroidogenesis by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2: role of protein kinase A and protein kinase C signaling. J Endocrinol 193:53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS 2001 New signaling pathways for hormones and cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate action in endocrine cells. Mol Endocrinol 15:209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli M, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL 2002 The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor, a 2002 perspective. Endocr Rev 23:141–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozengurt E, Rey O, Waldron RT 2005 Protein kinase D signaling. J Biol Chem 280:13205–13208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz P, Döppler H, Toker A 2005 Protein kinase D mediates mitochondrion-to-nucleus signaling and detoxification from mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell Biol 25:8520–8530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero DG, Welsh BL, Gomez-Sanchez EP, Yanes LL, Rilli S, Gomez-Sanchez CE 2006 Angiotensin II-mediated protein kinase D activation stimulates aldosterone and cortisol secretion in H295R human adrenocortical cells. Endocrinology 147:6046–6055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang QJ 2006 PKD at the crossroads of DAG and PKC signaling. Trends Pharmacol Sci 27:317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban RJ, Bodenburg YH, Jiang J, Denner L, Chedrese J 2004 Protein kinase Cι enhances the transcriptional activity of the porcine P-450 side-chain cleavage insulin-like response element. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 286:E975–E979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherradi N, Capponi AM, Gaillard RC, Pralong FP 2001 Decreased expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein: a novel mechanism participating in the leptin-induced inhibition of glucocorticoid biosynthesis. Endocrinology 142:3302–3308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima K, Yoshii K, Fukuda S, Orisaka M, Miyamoto K, Amsterdam A, Kotsuji F 2005 Luteinizing hormone-induced extracellular-signal regulated kinase activation differently modulates progesterone and androstenedione production in bovine theca cells. Endocrinology 146:2903–2910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Chandrala SP, Jo Y, Stocco DM 2006 cAMP-independent signaling regulates steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig cells in the absence of StAR phosphorylation. J Mol Endocrinol 37:81–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Poon SL, Chen J, Cheng L, HoYuen B, Leung PC 2009 Leptin interferes with 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) signaling to inhibit steroidogenesis in human granulosa cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 7:115–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson ER, Waterman MR 1988 Regulation of the synthesis of steroidogenic enzymes in adrenal cortical cells by ACTH. Annu Rev Physiol 50:427–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WL 1988 Molecular biology of steroid hormone synthesis. Endocr Rev 9:295–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rykx A, De Kimpe L, Mikhalap S, Vantus T, Seufferlein T, Vandenheede JR, Van Lint J 2003 Protein kinase D: a family affair. FEBS Lett 546:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Pakarinen P, El-Hefnawy T, Huhtaniemi IT 1999 Functional assessment of the calcium messenger system in cultured mouse Leydig tumor cells: regulation of human chorionic gonadotropin-induced expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein. Endocrinology 140:1739–1751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Walsh LP, Reinhart AJ, Stocco DM 2000 The role of arachidonic acid in steroidogenesis and steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) gene and protein expression. J Biol Chem 275:20204–20209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brändlin I, Hübner S, Eiseler T, Martinez-Moya M, Horschinek A, Hausser A, Link G, Rupp S, Storz P, Pfizenmaier K, Johannes FJ 2002 Protein kinase C (PKC)η-mediated PKCμ activation modulates ERK and JNK signal pathways. J Biol Chem 277:6490–6496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman E, Yivgi-Ohana N, Sher N, Bell M, Eimerl S, Orly J 2006 Transcriptional activation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene: GATA-4 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta confer synergistic responsiveness in hormone-treated rat granulosa and HEK293 cell models. Mol Cell Endocrinol 252:92–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrivia JC, Kwok RP, Lamb N, Hagiwara M, Montminy MR, Goodman RH 1993 Phosphorylated CREB binds specifically to the nuclear protein CBP. Nature 365:855–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abate C, Baker SJ, Lees-Miller SP, Anderson CW, Marshak DR, Curran T 1993 Dimerization and DNA binding alter phosphorylation of Fos and Jun. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:6766–6770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi H, Christenson LK, Chang L, Sammel MD, Berger SL, Strauss 3rd JF 2004 Temporal and spatial changes in transcription factor binding and histone modifications at the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) locus associated with StAR transcription. Mol Endocrinol 18:791–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.