Abstract

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection is the most significant cause of viral death in infants worldwide. The significant morbidity and mortality associated with this disease underscores the urgent need for the development of an RSV vaccine. The development of an RSV vaccine has been hampered by our limited understanding of the human host immune system, which plays a significant role in RSV pathogenesis, susceptibility and vaccine efficacy. As a result, animal models have been developed to better understand the mechanisms by which RSV causes disease. Within the past few years, a revolutionary variation on these animal models has emerged – age at time of initial infection – and early studies in neonatal mice (aged <7 days at time of initial infection) indicate the validity of this model to understand RSV infection in infants. This article reviews available information on current murine and emerging neonatal mouse RSV models.

Keywords: cotton rat, human, infant, mouse, neonate, respiratory syncytial virus

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading viral respiratory pathogen in infants and young children worldwide [1]. Most children are infected during their first RSV season; and by 2 years of age, almost all children have been infected with RSV and over 50% have been infected twice [2–4]. Few infants are infected prior to 2 months of age and the highest incidence of infection is seen between 3 and 4 months of age [2]. The global burden of this disease is estimated at 64 million cases and 160,000 deaths annually [101]. Yearly in the USA, it is responsible for 85,000 to 144,000 infant hospitalizations [5]. Healthcare costs are estimated at US$365–585 million per year [6], and the economic impact, in relation to days lost from work, is greater than that of influenza [7]. Mortality rates from primary infection are 0.005–0.02% for healthy and 1–3% for hospitalized children [8,9]. Importantly, long-term resistance to RSV infection does not develop and reinfection is common and often causes severe illness among those with chronic lung or heart disease [10,101].

Despite the considerable worldwide impact of RSV infection, a vaccine to protect against RSV remains elusive. There is also a need for safe and efficacious therapeutics against RSV infection. Ribavirin is the only approved antiviral therapy for RSV; however, it is rarely used in the pediatric population owing to its teratogenic potential and its limited effectiveness [11–13]. Humanized monoclonal antibodies (RespiGam® and Synagis®, MedImmune, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) are often used to prevent infections in infants and are currently only recommended for use in high-risk infants and young children. Unfortunately, these antibodies are only partially effective and are administered to less than 5% of the at-risk children [13]. Development of an effective vaccine and/or therapeutics has been hampered significantly by our lack of understanding of the virus, the host immune system at time of initial infection (i.e., infant/neonatal immunity), and the interaction between the virus and the host immune system.

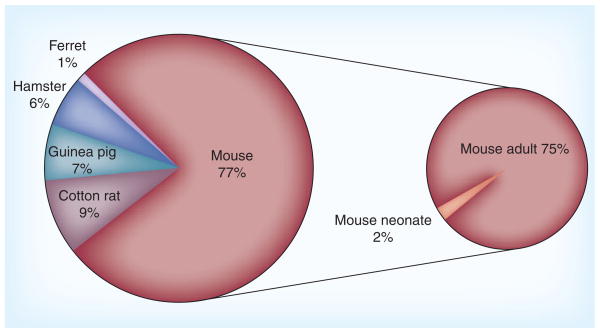

Studies are not feasible in humans because of safety issues; consequently, several animal models have been developed to better understand the mechanisms by which RSV causes disease. The most common include rodents, cows, sheep and nonhuman primates. Each model has its advantages and disadvantages and the model chosen often depends on the end points being studied (Table 1). For example, studies focusing on immune mechanisms of disease are generally performed in mouse models owing to their immunological similarity with humans. Other reasons include the availability of numerous reagents including immunochemicals and genetically modified strains, not to mention reduced animal husbandry and housing costs. Animal models have proven valuable in understanding RSV pathogenesis; however, the majority of these studies were performed in adult animal models (Figure 1) and it is unclear how accurately data derived from these models reflect human disease. In fact, it could be argued that the use of adult animal models is the reason for the discrepancies between human and animal model data. Current data suggest that a more relevant model for the human infant is the neonatal mouse. This article will give an overview of currently used murine RSV models, discuss their relevance to human disease, and explore the emerging neonatal mouse model.

Table 1.

Age-specific characteristics of the immune response to respiratory syncytial virus.

| Immune responses | Adult mice | Neonatal mice | Human infants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cellular | ||||

| B cells/antibodies | IgG2a>IgG2b>IgG1> IgE [74] | IgG2a>IgG1>IgGA> IgE [50] | +/− IgA>IgG>IgM [75]; B-cell receptor lacks somatic mutation [76] | |

| CD4+ T cells | ++: Th1>Th2 [77] | +: Th2>Th1 [50] | ++: Th2>Th1 [78,79] | |

| CD8+ T cells | +++ [80] | +: less IFN-γ producing [80] | +++ [81,82] | |

| Dendritic cells | Both subsets increase after infection [83] | mDCs stay the same; pDCs decrease after infection [Cormier SA, Unpublished Data] | Both increase in nasal wash [84] | |

| Alveolar macrophages | +++ [49] | +++ [49] | Increase in the lung parenchyma and alveolar spaces [15] | |

| Neutrophils | + [49] | + [49] | +++ [85] | |

| Eosinophils | +/− [49] | + [49] | +/− [85] | |

| Natural killer cells | +++ [86] | ? | +/− [78] | |

|

Cytokines | ||||

| Proinflammatory cytokines | IL-1β | ++ [87] | ? | ++ [88] |

| IL-6 | + [15,87,89] | ++ [Cormier SA, Unpublished Data] | ++ [87,90,91] | |

| TNF-α | + [15,89] | + [Cormier SA, Unpublished Data] | ++ [90,91] | |

| Immunoregulatory cytokines | IFN-γ | +++ [49] | +/− [49] | − [92] |

| IFN-α/β | +++ [93] | IFN-α; +/− IFN-β [Cormier SA, Unpublished Data] | ||

| IL-9 | ++ [80] | +++ [80] | + [90] | |

| IL-4 | + [80] | + [50] | + [94] | |

| IL-12 (p40) | ++[87] | +++ [50] | ||

| IL-12 (p70) | + [87] | + | ||

| IL-13 | + [49] | ++ [49] | +/− [94] | |

| IL-17 | ++ [87] | + | + [94] Undetectable in nasopharyngeal secretions [20] | |

|

Chemokines | ||||

| CCL5 | +++ [80] | + [80] | +++ [90] | |

−: Not detected; +/−: Very little; +: Low; ++: Medium; +++: High; ?: Unknown.

CCL: C–C motif chemokine ligand; DC: Dendritic cell; mDC: Myeloid dendritic cell; pDC: Plasmacytoid dendritic cell.

Figure 1. PubMed manuscripts referencing the use of rodents in studies of respiratory syncytial virus.

Data is displayed as percent of all rodent studies.

RSV in humans

In human infants, RSV causes both upper and lower respiratory tract infection with an incubation time ranging from 2 to 8 days [102]. Clinical symptoms include runny nose, sneezing, coughing and/or fever. Most infants recover from the infection in 1–2 weeks; however, 25–40% develop clinically significant disease as evidenced by outpatient visits or hospitalizations (0.5–2% require hospitalization) [14].

Severe RSV infection in infants induces bronchiolitis, interstitial pneumonitis and sometimes alveolitis [15]. The peribronchiolar infiltrates include primarily macrophages/monocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils and occasionally eosinophils. Interstitial inflammatory cells are primarily mononuclear cells and occasionally neutrophils. In the alveolar spaces, macrophages/monocytes are the cells that predominate.

A biased Th2-cell response to RSV has been speculated to be, at least partially, responsible for RSV pathogenesis in human infants [16]. Although inconsistent cytokine data has been reported due to different specimen collection methods and sample population diversity, Th2 cytokines including IL-4 and IL-5 have been found significantly elevated in the serum of RSV-infected infants compared with that of influenza-infected infants [17]. IL-4 is also detected more often than IFN-γ in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of RSV-infected infants [18]. Moreover, detection of IL-4 and IL-5 in the blood of infants is associated with more severe RSV disease, whereas elevated IFN-γ levels are associated with milder disease [19].

Recent data from infants further indicate that, in addition to a Th2-biased immune response, there is also an insufficient T-cell response, which plays a role in RSV pathogenesis. In fact, only low numbers of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are recruited to lungs of RSV-infected infants [15,20]. Interestingly, CD3+ cells are recruited to the airway and lung parenchyma after RSV infection in infants, but a substantial number of them are double-negative cells [15]. This CD3+CD4−CD8− population remains poorly defined and could represent T-regulatory cells [21]; natural killer T cells, which have been observed in a mouse model of RSV [22], or double-negative T cells, which have been observed in lungs of RSV-infected mice [23,24].

Another important characteristic of severe RSV infection in human infants is that the infection causes significant airway obstruction due to sloughing of epithelial cells, papillary projections of the epithelium and macrophage recruitment to the airway lumen [15]. The sloughed epithelial cells are positive for RSV antigen, indicating infection of these cells by the virus, whereas the papillary projections are negative for RSV antigen. Following RSV infection, bronchiolar epithelial cells become caspase-3 positive, suggesting that sloughed epithelial cells undergo apoptosis [20]. In summary, these observations suggest that RSV infects epithelial cells and possibly other cells, causes apoptosis of these cells, and eventually leads to the obstruction of the airway.

Current murine models

A quick search of PubMed reveals that the most common experimental nonprimate model of RSV infection excluding cows is murine models, including BALB/c mice and cotton rats (Figure 1).

The adult mouse model

Mouse models of RSV infection and induced disease have been developed and used extensively to understand mechanisms linking RSV with subsequent wheeze (i.e., asthma). In general, significant acute pulmonary inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness are observed in the majority of mouse models. Following RSV infection, viral load usually peaks by the fourth day and wanes by the eighth day. Peribronchovascular inflammation is observed as early as 3 days post-infection (dpi) and reaches a maximum at 6 dpi with a clear involvement of alveolar space [25]. The infiltrates are composed primarily of lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages [25], with a few neutrophils and eosinophils [26]. NK cells are the first lymphocyte subpopulation to enter the lung during an RSV infection and are responsible for the high amount of IFN-γ seen early in the infection [27–29]. This is followed by the recruitment of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and the release of type I cytokines (IL-12 and IFN-γ) with low levels of type II cytokines (IL-4, -5 and -13) [26–29]. CD8+ T cells [30] accompanied by IFN-γ [28] are the main effectors responsible for facilitating viral clearance, but also induce host tissue damage and pathology.

Human infants vaccinated with formalin-inactivated RSV (FI-RSV) and subsequently infected with community-acquired RSV developed severe respiratory illness, whereas nonvaccinated children infected with RSV showed significantly milder symptoms [31]. Clinical symptoms of the vaccine-enhanced illness were typically wheezing, cough and coryza. Lung histopathology of the children who died revealed severe infiltration of monocytes and eosinophils [31–33]. Adult mice have been used extensively to understand FI-RSV-enhanced disease. Similar to humans, FI-RSV-vaccinated mice challenged with RSV develop extensive pulmonary pathologies and characteristic Th2 responses including elevated levels of IL-4, -5 and -13; reduced levels of IL-12; and pulmonary eosinophilia [34,35]. Also, similar to humans, the mice developed high titers of RSV-specific antibodies that fail to offer protection from subsequent infection [34,35].

Many of the immunological responses of mice to RSV infection are similar to humans, and the use of this model system has greatly enhanced our understanding of RSV pathogenesis. However, there are a few significant differences between mice and men that should be considered. The most important is that RSV is a human pathogen and replicates poorly in mice. This requires high inoculums for productive infection and induction of pathology. Second, viral replication does not appear to occur in the bronchioles of mice as it does in humans; in fact, RSV primarily infects alveolar pneumocytes in mice [36]. Lung histopathology induced by RSV in mice differs from that of humans in some aspects, including reduced neutrophil involvement and lack of airway obstruction [25]. Finally, clinical illness is monitored by weight loss and ruffled fur instead of runny nose, sneezing, cough and/or fever.

The cotton rat model

Cotton rats were developed as an RSV model because they are highly susceptible to RSV and permissive to RSV replication [37]. RSV is detectable in both nasal tissue and lungs of infected cotton rats at 2 dpi. Pulmonary viral load usually peaks by the fifth day of infection. Viral load wanes from this point forward and becomes undetectable by 8 dpi [38]. In stark contrast to mouse models of RSV, viral replication in the rat lung is 50–1000-fold greater [39].

Respiratory syncytial virus infection in cotton rats induces pulmonary histopathology similar to that observed in humans, although it does not cause overt clinical symptoms. Infected animals develop prominent epithelial degeneration of nasal mucosa, discernable peribronchiolitis, perivasculitis and interstitial pneumonitis [38]. These pathologies are present as early as 2 dpi peak at 6 dpi, and decline by 8 dpi [38]. In contrast to human data, the primary cells recruited to the lungs are neutrophils and lymphocytes [40].

In addition to modeling natural RSV infection, cotton rats have also been used extensively to study vaccine-enhanced disease [41]. Cotton rats vaccinated with FI-RSV develop enhanced disease upon RSV challenge. The vaccinated cotton rats experience more prominent pulmonary inflammation as observed in human infants who received FI-RSV as a vaccine and subsequently acquired RSV. However, there are differences between cotton rat and human responses to FI-RSV. FI-RSV-vaccinated cotton rats experienced extensive pulmonary inflammation consisting of neutrophils and lymphocytes, not monocytes and eosinophils as in humans [31–33]. Human data suggest a Th2-type immune response in the lung characterized by eosinophilia [31], which is not shown in cotton rat models. In fact, FI-RSV-vaccinated cotton rats express augmented cytokines of both types, including Th2 (IL-4, -5 and -9) and Th1 (IFN-γ and IL-12p40) upon challenge [42].

Cotton rats are the pharmaceutical model of choice and are used to study the efficacy of a variety of antiviral drugs and prophylaxis reagents. The two approved reagents (RespiGam® and Synagis®, [MedImmune]) for prevention of RSV infection were both tested in the cotton rat model and progressed to clinical trials without further examination in primate models [43–46]. Even the dose of the drug being used in human infants was accurately predicted from the cotton rat model.

We hypothesize that age-dependent differences in immune response to RSV exists in the cotton rat as they do in humans. In fact, one study reported that neonatal cotton rats (aged 3 days) infected with RSV showed a higher (~tenfold) viral load in the nasal tissue, tracheas and lungs compared with viral load in adults [47]. Therefore, we suggest that a more relevant model of human disease can be obtained through the development of a neonatal cotton rat RSV-infection model.

In summary, both mice and cotton rats are valuable models to help understand human RSV infection. Cotton rats are extremely useful in developing pharmaceuticals for RSV therapy and prophylaxis, as they are highly permissive for RSV infection [47] and the lung histopathology induced by RSV infection in cotton rats is more similar to human infants. The major limitation of this model is that the cotton rat fails to develop a Th2-skewed immune response to RSV as observed in humans. Although mice are less permissive for RSV replication as compared with cotton rats, the plethora of reagents make them invaluable in elucidating the mechanisms of RSV pathogenesis. In addition, a Th2-biased response to RSV reinfection in mice has been independently reported by different laboratories, including ours [48–50].

Age of initial RSV infection plays a key role in pathogenesis

The immune systems of neonates and adults differ substantially. In neonates, total lymphocyte and dendritic cell numbers are significantly lower compared with adults [51]. Lymphoid follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal center structures of secondary lymphoid tissue, known to be crucial for antibody development, are absent at birth and form between a few days to a few weeks of age [52]. The complete development of antigen-presenting cells is achieved several weeks after birth [53].

The age of initial infection is considered to be an important risk factor for RSV-mediated diseases [14]. Infants are particularly susceptible to RSV infection and rates of infection and disease severity are highest in those under 6 months of age [54]. Both the increased susceptibility to RSV infection and disease severity are believed to be partly due to an immature immune system [55,56]; however, other factors such as airway size and maturation status of the lung, although not discussed here, may also contribute to the increased susceptibility and disease severity.

Several retrospective and prospective studies suggest a link between RSV lower respiratory tract infections and later development of asthma in infants [57–62]. The Tucson Children’s Respiratory study demonstrates that children with even mild RSV infections are four-times more likely to have recurrent, frequent wheeze to age 13 years [61]. By contrast, an 18–20 year prospective cohort study from Finland clearly demonstrates that severe bronchiolitis (RSV was responsible for 71% of viral diagnoses [63]) requiring hospitalization in infancy is a significant risk factor for asthma that extends into early adulthood and is independent of atopy [64]. In the Tucson Children’s Respiratory study, increased risk for RSV-associated wheeze was almost insignificant at age 13; whereas in the Finland study, increased risk for asthma persisted to age 20 years (end point of the study). The Finnish study is consistent with a more recent study performed in Sweden in which history of hospitalization for RSV bronchiolitis was the significant risk factor identified at 18 years of age for current asthma [65]. A more recent study, The Tennessee Children’s Respiratory Initiative, using a cohort of more than 95,000 infants also further demonstrates a role for severe respiratory viral infection in the development of asthma [14]. The reasons for the discrepancy between the studies are unclear but may have to do with the cohorts used in the studies. The birth cohort in the Tucson study consisted of infants and young children, birth to 3 years of age, with mild wheezing, which in most cases did not require hospitalization. The birth cohort in the Finland and Sweden study consisted of infants (<24 months and <12 months, respectively, with 91% younger than 6 months of age at time of hospital admission) with severe bronchiolitis requiring hospitalization [61,64,65]. In total, these studies establish that age at initial infection and severity of RSV-induced bronchiolitis is a strong predictor of asthma susceptibility. To answer the question of whether severe RSV infection predisposes to asthma, age-relevant mouse models are being used.

A mouse model of neonatal RSV infection, which recapitulates many of the pathologies associated with RSV infection in infants, has recently been developed. In this model, mice infected as neonates (aged ≤7days) develop long-term ‘asthma’ characterized by increased airway hypersensitivity, mucus hyperproduction, Th2 cytokine and cellular responses and airway remodeling [48,49,66,67]. Data from these mouse models closely resemble the data from human epidemiological studies (i.e., that the age of initial infection is the major determinant in the persistence of lung dysfunction into early adulthood). In mice, when primary RSV infection occurs in the first week of life, a subsequent RSV infection or allergen challenge causes severe lung immuno- and patho-physiology similar to asthma [48,49,67]. However, when primary RSV infection occurs in weanlings or adults, overt pulmonary pathophysiology does not persist and is significantly less severe following secondary RSV infection [49] or allergen challenge [66]. The emerging data suggest that disease outcome of RSV infection even in the mouse is dictated by the age at initial infection. This further suggests that an inchoate immunological response may be responsible for disease outcome and therefore highlights the importance of the neonatal mouse model for a disease that affects human infants.

Expert commentary & five-year view

Although intensive research efforts have been made to understand the pathogenesis of RSV infection, many questions remain unanswered. Although RSV has been prioritized for control and vaccine development by national and global health organizations for more than 50 years, no effective vaccine or therapy exists.

Progress in RSV vaccine development has been very slow owing to the detrimental effects of the FI-RSV vaccine. The failure of the FI-RSV vaccine was primarily a consequence of our limited understanding of the pathophysiology of RSV infection and most importantly due to our lack of knowledge of the infant immune system. Even today the importance given towards the understanding of the pathogenesis of RSV infection in an age-relevant model is minimal, with the majority of RSV studies being conducted in adult animal models. Attaining more knowledge of neonatal/infant immune responses is essential if we are to develop effective vaccines not only for RSV but for other pediatric diseases.

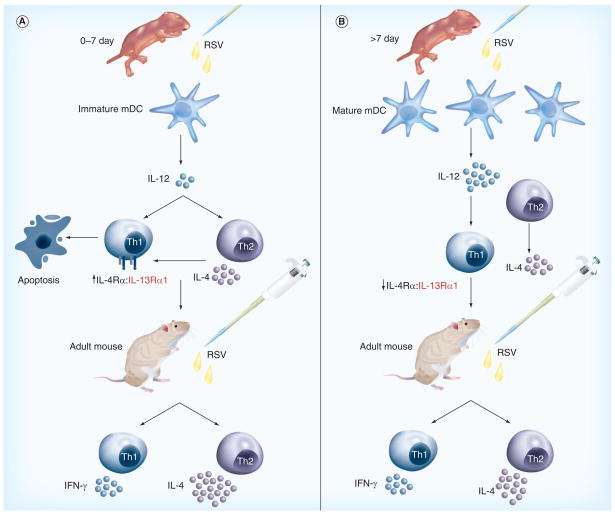

As soluble mediators of the immune system, Th2 cytokines may play a key role in infantile/neonatal RSV pathogenesis (Figure 2). IL-4 and IL-13 are classical Th2 cytokines that have been known to be central mediators in RSV-mediated airway disease in both mouse models [68] and humans [69,70]. Similarly, the receptors of IL-4 and IL-13 have also been shown to be key players in RSV pathogenesis [16,69–71]. IL-4 has two receptors, the type I and type II receptor. The type I receptor is composed of IL-4 receptor α (IL-4Rα) and the common γ chain (γc) and initiates Th2 cell differentiation. The type II IL-4 receptor is composed of the IL-4Rα and IL-13 receptor α1 (IL-13Rα1) subunits. IL-13 shares the type II receptor with IL-4 and binds an additional receptor, IL-13 receptor α2. In human infants, genetic studies demonstrate that variations in the IL-4Rα gene are associated with severity of RSV bronchiolitis [71].

Figure 2. Summary of the immune responses against respiratory syncytial virus.

(A) Neonatal mice express elevated levels of IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 on Th1 cells. RSV infection of neonatal mice results in the rapid production (<24 h) of Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-13. Signaling by IL-4/IL-13 through the IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 on Th1 cells results in their specific depletion by apoptosis. The immaturity of neonatal mDC inhibits their effective production of IL-12 in response to RSV infection and this, in turn, results in the prolonged elevation of IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 levels on Th1 cells [95]. As the neonatal mouse matures to an adult, IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 declines on Th1 cells. Upon reinfection with RSV as an adult, IL-4/IL-13 no longer produce Th1 cell apoptosis and stimulate RSV-specific Th2 cells resulting in an immune response that appears to be Th2 biased. (B) Adult mice express low levels of IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 on Th1 cells. RSV infection of adult mice results in the rapid production of Th2 and Th1 cytokines. Apoptosis of Th1 cells is greatly minimized by the reduced levels of the receptors on adult Th1 cells owing to development and to the increase in IL-12 production from the more mature mDC. Consequently, a Th1 and Th2 response develops.

mDC: Myeloid dendritic cells; R: Receptor; RSV: Respiratory syncytial virus.

In support of the human data, studies from our laboratory using a neonatal mouse model and pharmacological knockdown of IL-4Rα reveals that IL-4Rα is required in the pathogenesis of neonatal RSV infection [50]. Our data clearly indicate that reduction of IL-4Rα in the lung at the time of initial infection inhibits the development of Th2 cell subsets following primary and secondary RSV infection. The reasons for this are just being realized and are dependent on the use of neonatal models.

In neonatal mice, IL-4Rα [Cormier SA, Unpublished Data] and IL-13Rα1 [72] expression is elevated on Th1 cells compared with adult Th1 cells. However, the function of these receptors on Th1 cells is unlike that of Th2 cells; in particular, data from our laboratory and from Zaghouani’s group using different models (RSV vs ovalbumin, respectively) demonstrate that IL-4/IL-13 induced by RSV infection or ovalbumin treatment in the neonate results in the specific depletion of Th1 cells [72,73] [Cormier SA, Unpublished Data]. Our data further suggest that downregulating IL-4Rα allows for the survival of Th1 cells in the presence of Th2 cytokines such as IL-4/IL-13. These findings strengthen the importance of the age of initial infection of RSV in determining disease outcome and suggest that immunomodulatory agents administered at the time of vaccination may be the key to a successful vaccine.

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact reprints@expert-reviews.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grants to Stephania A Cormier (5R01ES015050 and P42ES013648). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. A patent application has been filed by Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center as a result of research with IL-4Rα in neonates with Stephania A Cormier as the inventor. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.LC, Ciuryla V, Ciesla G, Liu L. Economic impact of respiratory syncytial virus-related illness in the US: an analysis of national databases. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22(5):275–284. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glezen WP, Taber LH, Frank AL, Kasel JA. Risk of primary infection and reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140(6):543–546. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140200053026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeck KD. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis: clinical aspects and epidemiology. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 1996;51(3):210–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson FW, Collier AM, Clyde WA, Jr, Denny FW. Respiratory-syncytial-virus infections, reinfections and immunity. A prospective, longitudinal study in young children. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(10):530–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197903083001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stang P, Brandenburg N, Carter B. The economic burden of respiratory syncytial virus-associated bronchiolitis hospitalizations. Arch Ped Adolesc Med. 2001;155(1):95–96. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming DM, Elliot AJ, Cross KW. Morbidity profiles of patients consulting during influenza and respiratory syncytial virus active periods. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135(7):1099–1108. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807007881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chanock R, Roizman B, Myers R. Recovery from infants with respiratory illness of a virus related to chimpanzee coryza agent (CCA). I. Isolation, properties and characterization. Am J Hyg. 1957;66(3):281–290. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruuskanen O, Ogra PL. Respiratory syncytial virus. Curr Probl Pediatr. 1993;23(2):50–79. doi: 10.1016/0045-9380(93)90003-U. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bont L, Versteegh J, Swelsen WT, et al. Natural reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus does not boost virus-specific T-cell immunity. Pediatr Res. 2002;52(3):363–367. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeVincenzo J. Pre-emptive ribavirin for ‘RSV’ in BMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26(1):113–114. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimpen JL, Schaad UB. Treatment of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis: 1995 poll of members of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16(5):479–481. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199705000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Red Book. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2009;2009(1):560–569. [Google Scholar]

- 14••.Wu P, Dupont WD, Griffin MR, et al. Evidence of a causal role of winter virus infection during infancy in early childhood asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(11):1123–1129. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-579OC. First human study to demonstrate the importance of age at initial infection in determining risk for developing childhood asthma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JE, Gonzales RA, Olson SJ, Wright PF, Graham BS. The histopathology of fatal untreated human respiratory syncytial virus infection. Mod Pathol. 2007;20(1):108–119. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Openshaw PJ. Antiviral immune responses and lung inflammation after respiratory syncytial virus infection. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2(2):121–125. doi: 10.1513/pats.200504-032AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sung RY, Hui SH, Wong CK, Lam CW, Yin J. A comparison of cytokine responses in respiratory syncytial virus and influenza A infections in infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160(2):117–122. doi: 10.1007/s004310000676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mobbs KJ, Smyth RL, O’Hea U, et al. Cytokines in severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002;33(6):449–452. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee FE, Walsh EE, Falsey AR, et al. Human infant respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-specific type 1 and 2 cytokine responses ex vivo during primary RSV infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(12):1779–1788. doi: 10.1086/518249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welliver TP, Garofalo RP, Hosakote Y, et al. Severe human lower respiratory tract illness caused by respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus is characterized by the absence of pulmonary cytotoxic lymphocyte responses. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(8):1126–1136. doi: 10.1086/512615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang ZX, Yang L, Young KJ, DuTemple B, Zhang L. Identification of a previously unknown antigen-specific regulatory T cell and its mechanism of suppression. Nat Med. 2000;6(7):782–789. doi: 10.1038/77513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson TR, Hong S, Van Kaer L, Koezuka Y, Graham BS. NK T cells contribute to expansion of CD8+ T cells and amplification of antiviral immune responses to respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol. 2002;76(9):4294–4303. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4294-4303.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Openshaw PJ. Pulmonary epithelial T cells induced by viral infection express T cell receptors α/β. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21(3):803–806. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Openshaw PJ. Flow cytometric analysis of pulmonary lymphocytes from mice infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;75(2):324–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham BS, Perkins MD, Wright PF, Karzon DT. Primary respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice. J Med Virol. 1988;26(2):153–162. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890260207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Openshaw PJ. Potential mechanisms causing delayed effects of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(3 Pt 2):S10–S13. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.supplement_1.2011111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Openshaw PJ. Immunity and immunopathology to respiratory syncytial virus. The mouse model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(4 Pt 2):S59–S62. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/152.4_Pt_2.S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boelen A, Andeweg A, Kwakkel J, et al. Both immunisation with a formalin-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine and a mock antigen vaccine induce severe lung pathology and a Th2 cytokine profile in RSV-challenged mice. Vaccine. 2000;19(7–8):982–991. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Schaik SM, Obot N, Enhorning G, et al. Role of interferon γ in the pathogenesis of primary respiratory syncytial virus infection in BALB/c mice. J Med Virol. 2000;62(2):257–266. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200010)62:2<257::aid-jmv19>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarze J, Cieslewicz G, Joetham A, et al. CD8 T cells are essential in the development of respiratory syncytial virus-induced lung eosinophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness. J Immunol. 1999;162(7):4207–4211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31••.Kim HW, Canchola JG, Brandt CD, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89(4):422–434. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120955. Report on the human respiratory syncytial virus vaccine administered to infants in the 1960s demonstrating that severity of community-acquired respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was greater in vaccinated than in unvaccinated infants and children. The youngest infants at the time of vaccination were more severely affected even though high levels of serum-neutralizing antibody were detected. Post-mortem examination revealed excess eosinophilic infiltrates in the lungs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapikian AZ, Mitchell RH, Chanock RM, Shvedoff RA, Stewart CE. An epidemiologic study of altered clinical reactivity to respiratory syncytial (RS) virus infection in children previously vaccinated with an inactivated RS virus vaccine. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89(4):405–421. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chin J, Magoffin RL, Shearer LA, Schieble JH, Lennette EH. Field evaluation of a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine and a trivalent parainfluenza virus vaccine in a pediatric population. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89(4):449–463. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connors M, Kulkarni AB, Firestone CY, et al. Pulmonary histopathology induced by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) challenge of formalin-inactivated RSV-immunized BALB/c mice is abrogated by depletion of CD4+ T cells. J Virol. 1992;66(12):7444–7451. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7444-7451.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waris ME, Tsou C, Erdman DD, Zaki SR, Anderson LJ. Respiratory synctial virus infection in BALB/c mice previously immunized with formalin-inactivated virus induces enhanced pulmonary inflammatory response with a predominant Th2-like cytokine pattern. J Virol. 1996;70(5):2852–2860. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2852-2860.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore E, Barber J, Tripp R. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) attachment and nonstructural proteins modify the type I interferon response associated with suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins and IFN-stimulated gene-15 (ISG15) Virol J. 2008;5(1):116. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clyde WA., Jr Experimental models for study of common respiratory viruses. Environ Health Perspect. 1980;35:107–112. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8035107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piazza FM, Johnson SA, Darnell ME, et al. Bovine respiratory syncytial virus protects cotton rats against human respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Virol. 1993;67(3):1503–1510. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1503-1510.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wyde PR, Ambrose MW, Meyerson LR, Gilbert BE. The antiviral activity of SP-303, a natural polyphenolic polymer, against respiratory syncytial and parainfluenza type 3 viruses in cotton rats. Antiviral Res. 1993;20(2):145–154. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(93)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prince GA, Prieels JP, Slaoui M, Porter DD. Pulmonary lesions in primary respiratory syncytial virus infection, reinfection, and vaccine-enhanced disease in the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) Lab Invest. 1999;79(11):1385–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prince GA, Jenson AB, Hemming VG, et al. Enhancement of respiratory syncytial virus pulmonary pathology in cotton rats by prior intramuscular inoculation of formalin-inactiva ted virus. J Virol. 1986;57(3):721–728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.3.721-728.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boukhvalova MS, Prince GA, Soroush L, et al. The TLR4 agonist, monophosphoryl lipid A, attenuates the cytokine storm associated with respiratory syncytial virus vaccine-enhanced disease. Vaccine. 2006;24(23):5027–5035. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meissner HC, Welliver RC, Chartrand SA, et al. Immunoprophylaxis with palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, for prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infection in high risk infants: a consensus opinion. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18(3):223–231. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199903000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ottolini MG, Porter DD, Hemming VG, et al. Effectiveness of RSVIG prophylaxis and therapy of respiratory syncytial virus in an immunosuppressed animal model. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24(1):41–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prince GA, Mathews A, Curtis SJ, Porter DD. Treatment of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis and pneumonia in a cotton rat model with systemically administered monoclonal antibody (palivizumab) and glucocorticosteroid. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(5):1326–1330. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sami IR, Piazza FM, Johnson SA, et al. Systemic immunoprophylaxis of nasal respiratory syncytial virus infection in cotton rats. J Infect Dis. 1995;171(2):440–443. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prince GA, Jenson AB, Horswood RL, Camargo E, Chanock RM. The pathogenesis of respiratory syncytial virus infection in cotton rats. Am J Pathol. 1978;93(3):771–791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48••.Culley FJ, Pollott J, Openshaw PJ. Age at first viral infection determines the pattern of T cell-mediated disease during reinfection in adulthood. J Exp Med. 2002;196(10):1381–1386. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020943. First mouse study to demonstrate the importance of age at initial infection in determining T-cell responses to primary and secondary infection in later life. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49••.Dakhama A, Park JW, Taube C, et al. The enhancement or prevention of airway hyperresponsiveness during reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus is critically dependent on the age at first infection and IL-13 production. J Immunol. 2005;175(3):1876–1883. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1876. This mouse study demonstrated that infection of neonatal mice with RSV followed by reinfection in the adult resulted in airways hyper-responsiveness, airway eosinophilia and mucus hyperproduction. The pathology associated with neonatal RSV infection was dependent on IL-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ripple M, You D, Giaimo J, et al. Immunomodulation with IL-4Rα antisense oligonucleotide prevents respiratory syncytial virus-mediated pulmonary disease. J Immunol. 2010;185:4804–4811. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adkins B, Leclerc C, Marshall-Clarke S. Neonatal adaptive immunity comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(7):553–564. doi: 10.1038/nri1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu YX, Chaplin DD. Development and maturation of secondary lymphoid tissues. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:399–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun CM, Fiette L, Tanguy M, Leclerc C, Lo-Man R. Ontogeny and innate properties of neonatal dendritic cells. Blood. 2003;102(2):585–591. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boyce TG, Mellen BG, Mitchel EF, Jr, Wright PF, Griffin MR. Rates of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection among children in medicaid. J Pediatr. 2000;137(6):865–870. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.110531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Forster J, Streckert HJ, Werchau H. The humoral immune response of children and infants to an RSV infection: its maturation and association with illness. Klin Padiatr. 1995;207(6):313–316. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1046559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilczynski J, Lukasik B, Torbicka E, Tranda I, Brzozowska-Binda A. The immune response of small children by antibodies of different classes to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) proteins. Acta Microbiol Pol. 1994;43(3–4):369–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sims DG, Downham MA, Gardner PS, Webb JK, Weightman D. Study of 8-year-old children with a history of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy. Br Med J. 1978;1(6104):11–14. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6104.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pullan CR, Hey EN. Wheezing, asthma, and pulmonary dysfunction 10 years after infection with respiratory syncytial virus in infancy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;284(6330):1665–1669. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6330.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McConnochie KM, Roghmann KJ. Bronchiolitis as a possible cause of wheezing in childhood: new evidence. Pediatrics. 1984;74(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murray M, Webb MS, O’Callaghan C, Swarbrick AS, Milner AD. Respiratory status and allergy after bronchiolitis. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67(4):482–487. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.4.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stein RT, Sherrill D, Morgan WJ, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus in early life and risk of wheeze and allergy by age 13 years. Lancet. 1999;354(9178):541–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sigurs N, Gustafsson PM, Bjarnason R, et al. Severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy and asthma and allergy at age 13. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(2):137–141. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-730OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Korppi M, Halonen P, Kleemola M, Launiala K. Viral findings in children under the age of two years with expiratory difficulties. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1986;75(3):457–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1986.tb10230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Piippo-Savolainen E, Remes S, Kannisto S, Korhonen K, Korppi M. Asthma and lung function 20 years after wheezing in infancy: results from a prospective follow-up study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(11):1070–1076. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.11.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sigurs N, Aljassim F, Kjellman B, et al. Asthma and allergy patterns over 18 years after severe RSV bronchiolitis in the first year of life. Thorax. 2010 doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.121582. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Becnel D, You D, Erskin J, Dimina DM, Cormier SA. A role for airway remodeling during respiratory syncytial virus infection. Respir Res. 2005;6(1):122. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67••.You D, Becnel D, Wang K, et al. Exposure of neonates to respiratory syncytial virus is critical in determining subsequent airway response in adults. Respir Res. 2006;7(107) doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-107. First mouse study to demonstrate that neonatal RSV infection led to long-term inflammatory airway disease characterized by airway hyper-reactivity, peribronchial and perivascular inflammation and subepithelial fibrosis It further demonstrated that neonatal RSV infection could predispose to increased susceptibility to allergic asthma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dakhama A, Lee YM, Ohnishi H, et al. Virus-specific IgE enhances airway responsiveness on reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus in newborn mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(1):138–145.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choi EH, Lee HJ, Yoo T, Chanock SJ. A common haplotype of interleukin-4 gene IL4 is associated with severe respiratory syncytial virus disease in Korean children. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(9):1207–1211. doi: 10.1086/344310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Puthothu B, Krueger M, Forster J, Heinzmann A. Association between severe respiratory syncytial virus infection and IL13/IL4 haplotypes. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(3):438–441. doi: 10.1086/499316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hoebee B, Rietveld E, Bont L, et al. Association of severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis with interleukin-4 and interleukin-4 receptor α polymorphisms. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(1):2–11. doi: 10.1086/345859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72•.Li L, Lee HH, Bell JJ, et al. IL-4 utilizes an alternative receptor to drive apoptosis of Th1 cells and skews neonatal immunity toward Th2. Immunity. 2004;20(4):429–440. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00072-x. Demonstrated that neonatal mouse Th1 cells express high levels of IL-13Rα and that IL-4 signaling through this receptor induces Th1 cell death resulting in a Th2 skewed recall response to antigen. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73•.Lee HH, Hoeman CM, Hardaway JC, et al. Delayed maturation of an IL-12-producing dendritic cell subset explains the early Th2 bias in neonatal immunity. J Exp Med. 2008;205(10):2269–2280. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071371. Mouse neonatal dendritic cells are incapable of producing sufficient quantities of IL-12 to suppress IL-13Rα expression on Th1 cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dakhama A, Park JW, Taube C, et al. The role of virus-specific Immunoglobulin E in airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(9):952–959. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200311-1610OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reed JL, Welliver TP, Sims GP, et al. Innate immune signals modulate antiviral and polyreactive antibody responses during severe respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(8):1128–1138. doi: 10.1086/597386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams JV, Weitkamp JH, Blum DL, LaFleur BJ, Crowe JE., Jr The human neonatal B cell response to respiratory syncytial virus uses a biased antibody variable gene repertoire that lacks somatic mutations. Mol Immunol. 2009;47(2–3):407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tripp RA, Hou S, Etchart N, et al. CD4+ T cell frequencies and Th1/Th2 cytokine patterns expressed in the acute and memory response to respiratory syncytial virus I-ed-restricted peptides. Cell Immunol. 2001;207(1):59–71. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Larranaga CL, Ampuero SL, Luchsinger VF, et al. Impaired immune response in severe human lower tract respiratory infection by respiratory syncytial virus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(10):867–873. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181a3ea71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bendelja K, Gagro A, Bace A, et al. Predominant type-2 response in infants with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection demonstrated by cytokine flow cytometry. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121(2):332–338. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tregoning JS, Yamaguchi Y, Harker J, Wang B, Openshaw PJ. The role of T cells in the enhancement of respiratory syncytial virus infection severity during adult reinfection of neonatally sensitized mice. J Virol. 2008;82(8):4115–4124. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02313-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heidema J, Lukens MV, van Maren WW, et al. CD8+ T cell responses in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of infants with severe primary respiratory syncytial virus infections. J Immunol. 2007;179(12):8410–8417. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lukens MV, van de Pol AC, Coenjaerts FE, et al. A systemic neutrophil response precedes robust CD8(+) T-cell activation during natural respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants. J Virol. 2010;84(5):2374–2383. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01807-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smit JJ, Rudd BD, Lukacs NW. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells inhibit pulmonary immunopathology and promote clearance of respiratory syncytial virus. J Exp Med. 2006;203(5):1153–1159. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gill MA, Palucka AK, Barton T, et al. Mobilization of plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cells to mucosal sites in children with respiratory syncytial virus and other viral respiratory infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(7):1105–1115. doi: 10.1086/428589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Everard ML, Swarbrick A, Wrightham M, et al. Analysis of cells obtained by bronchial lavage of infants with respiratory syncytial virus infection. Arch Dis Child. 1994;71(5):428–432. doi: 10.1136/adc.71.5.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hussell T, Openshaw PJ. Intracellular IFN-γ expression in natural killer cells precedes lung CD8+ T cell recruitment during respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Gen Virol. 1998;79(Pt 11):2593–2601. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-11-2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mejias A, Chavez-Bueno S, Raynor MB, et al. Motavizumab, a neutralizing anti-respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) monoclonal antibody significantly modifies the local and systemic cytokine responses induced by RSV in the mouse model. Virol J. 2007;4:109. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lindgren C, Grogaard J. Reflex apnoea response and inflammatory mediators in infants with respiratory tract infection. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85(7):798–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hayes PJ, Scott R, Wheeler J. In vivo production of tumour necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 in BALB/c mice inoculated intranasally with a high dose of respiratory syncytial virus. J Med Virol. 1994;42(4):323–329. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890420402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McNamara PS, Flanagan BF, Selby AM, Hart CA, Smyth RL. Pro- and anti-inflammatory responses in respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(1):106–112. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00048103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Matsuda K, Tsutsumi H, Okamoto Y, Chiba C. Development of interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor α activity in nasopharyngeal secretions of infants and children during infection with respiratory syncytial virus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2(3):322–324. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.3.322-324.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Roman M, Calhoun WJ, Hinton KL, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants is associated with predominant Th-2-like response. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(1):190–195. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.1.9611050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guerrero-Plata A, Casola A, Garofalo RP. Human metapneumovirus induces a profile of lung cytokines distinct from that of respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol. 2005;79(23):14992–14997. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14992-14997.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bermejo-Martin JF, Tenorio A, Ortiz de Lejarazu R, et al. Similar cytokine profiles in response to infection with respiratory syncytial virus type a and type B in the upper respiratory tract in infants. Intervirology. 2008;51(2):112–115. doi: 10.1159/000134268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95•.Rose S, Lichtenheld M, Foote MR, Adkins B. Murine neonatal CD4+ cells are poised for rapid Th2 effector-like function. J Immunol. 2007;178(5):2667–2678. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2667. The Th2 cytokine regulatory region (CNS-1) exists in a hypomethylated state in neonatal mice, predisposing them to rapid, effector-like Th2 function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Websites

- 101.WHO. Acute respiratory infections: respiratory syncytial virus. www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/ari/en/index3.html.

- 102.Centers for disease control and prevention. Respiratory syncytial virus infection. www.cdc.gov/rsv.