Abstract

High-throughput cell-based screens of genome-size collections of cDNAs and siRNAs have become a powerful tool to annotate the mammalian genome, enabling the discovery of novel genes associated with normal cellular processes and pathogenic states, and the unraveling of genetic networks and signaling pathways in a systems biology approach. However, the capital expenses and the cost of reagents necessary to perform such large screens have limited application of this technology. Efforts to miniaturize the screening process have centered on the development of cellular microarrays created on microscope slides that use chemical means to introduce exogenous genetic material into mammalian cells. While this work has demonstrated the feasibility of screening in very small formats, the use of chemical transfection reagents (effective only in a subset of cell lines and not on primary cells) and the lack of defined borders between cells grown in adjacent microspots containing different genetic material (to prevent cell migration and to aid spot location recognition during imaging and phenotype deconvolution) have hampered the spread of this screening technology. Here, we describe proof-of-principles experiments to circumvent these drawbacks. We have created microwell arrays on an electroporation-ready transparent substrate and established procedures to achieve highly efficient parallel introduction of exogenous molecules into human cell lines and primary mouse macrophages. The microwells confine cells and offer multiple advantages during imaging and phenotype analysis. We have also developed a simple method to load this 484-microwell array with libraries of nucleic acids using a standard microarrayer. These advances can be elaborated upon to form the basis of a miniaturized high-throughput functional genomics screening platform to carry out genome-size screens in a variety of mammalian cells that may eventually become a mainstream tool for life science research.

Introduction

Advent of the post genome sequencing era has highlighted the need to develop novel tools to assign gene function. Functional annotation of the mammalian genome has proven particularly difficult because tools that allow swift and systematic gene functionalization are lacking. Unlike bacteria, yeast, C. Elegans, Drosophila and other lower organisms, where large genetic screens can be carried out with relative ease to discern gene purpose, tools to delineate gene function, signaling pathways and genetic networks in mammalian cells have been very limited. The recent discovery and application of RNA interference (RNAi) gene silencing technology has dramatically expanded the ability of biologists to perturb gene function in mammalian cells on a global scale 1–5. RNAi takes advantage of existing cellular mechanisms to bring about specific gene knockdown. Together with screens of large cDNA collections, genome-wide RNAi screens recently completed in mammalian cells are yielding a wealth of new gene annotations 6, 7. These high-throughput cell-based screens use 96 or 384-well plate platforms that require extensive usage of robotics for plate manipulation, liquid handling, and assay. The costs of reagents associated with this kind of genome-wide screens (genetic libraries, cell culture supplies, transfection and assay reagents) limit the number of replicates that are typically run, directly affecting the quality of the data obtained. In addition, the capital expenses associated with the robotics required to handle such large numbers of plates have kept high-throughput cell-based screening of genetic collections in mammalian cells out of reach of most laboratories. To fully realize the potential of cell-based genetic screening in mammalian cells it is imperative that an advanced screening technology platform be developed, one that miniaturizes the screening process and reduces capital and reagent costs.

The Sabatini group was the first one to pilot an approach to miniaturize functional genomic screening 8. They described the development of a substantially miniaturized ‘reverse transfection’ method for parallel chemical transfection of cDNAs into mammalian cells cultured on a glass microscope slide. Plasmids encoding various cDNAs were arrayed onto glass slides at defined spots using a standard microarraying robot. The printed array was incubated with a lipid transfection reagent to allow formation of transfection complexes, placed in a tissue culture dish, and cells were seeded on top. As the cells sat on the DNA spots, they took up the underlying DNA (reverse transfection) and the phenotypic consequences of overexpression of individual cDNAs were assessed in a highly parallel fashion at a later time point. Phenotypic analysis was typically carried out by fixing the cells and visualizing the results using a microarray scanner or an automated scope. Using this cell microarray format, ~5,000 genetic experiments can be conducted on a single microscope slide 9. This method has since been successfully applied to deliver siRNA and shRNA molecules to silence gene expression in a miniaturized format in immortalized cell lines 10–12. Furthermore, modification of the surface chemistry of the slide has allowed the development of cell microarrays of non-adherent cell lines, something that may have been presumed to be incompatible with this format 13.

These pilot experiments with cell microarrays have offered a glimpse of the potential of miniaturized formats to accelerate high-throughput functional genetic studies in mammalian cells. However, these approaches share three drastically weaknesses that drastically limit application of this technology in its present form. First, they rely on chemical transfection to deliver the nucleic acid of interest into cells. This precludes the use of hard-to-transfect cell lines and virtually all clinically relevant primary cells (not transfectable with chemical reagents). Second, cell microarrays lack physical barriers to contain cells transfected with one nucleic acid from migrating and mixing with cells transfected with another nucleic acid. Migration of cells between spots can lead to inter-spot contamination, confounding phenotypic analysis and hindering time-lapse studies (where spots are visited multiple times over the course of the assay). Third, because the cells grow in a lawn without reference points, it is difficult to identify with certainty the microscale regions corresponding to individual spots during automated image analysis, and minor errors in imaging (due to tolerances in the microscope stage or during microarraying) can lead to incorrect phenotypic annotations. Perhaps due to these weaknesses, cell microarrays have failed to evolve as a viable second generation genome-wide genomic screening platform for mammalian cells.

Here, we describe proof-of-concept experiments of a design for a next generation genome-wide mammalian genomic screening platform that addresses the limitations that hampered previous attempts. First, our platform will use electroporation to introduce nucleic acids into mammalian cells. Electroporation has been used to deliver microarrayed cDNAs into an overlaying cell culture on transparent conductive Indium-Tin Oxide (ITO)-coated glass slides 14. Electroporation enables efficient introduction of nucleic acids into hard-to-transfect primary cells and has been adapted to microscale formats 15. Second, our design contemplates the fabrication of a microwell array to create spatially defined regions of microscale cultures and to restrict cell motility. Third, the edges of the microwells allow for accurate determination of microscale culture position on the conductive substrate during image acquisition and phenotypic analysis, an essential component of a high-throughput genetic screening platform. Our results demonstrate the feasibility of creating a next generation electroporation-based platform for mammalian functional genomics screening.

Materials and methods

Optimization of electroporation parameters for HEK 293T cells

Optimization was conducted on diced ITO coated glass (unpolished, surface resistivity 4–8 Ω sq−1, Delta Technologies, MN) pieces as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1A, on a custom-built electroporation setup (Supp. Fig 1B). Briefly, pieces 1 cm × 2.5 cm were diced from single microscope slides, rinsed in de-ionized water and dried under a nitrogen stream. Thereafter, 100 µl of 10 µg ml−1 Fibronectin from human plasma (Sigma) was pipetted on the top half of the piece and allowed to coat for 2 hrs. After aspiration and washing with PBS, 2–3 ×104 HEK293T cells in 100 µl of media (DMEM, 10% FBS and antibiotics) were added to the same spot. The cells were allowed to adhere to the spot for 1 hr in the incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2, prior to washing with PBS and flooding with media. After 24 hrs of incubation, media was aspirated and the cultures were immediately placed in the electroporation setup. Alternatively, 2 ×105 cells were plated within each well of a 6-well dish on top of the pieces. Prior to electroporation, the bottom half of the pieces was wiped to create an electrolyte free area for cathode placement.

A stainless steel anode was placed on top of the ITO piece at a spacing of 1 mm and ice cold electroporation buffer (5.5 mM D-Glucose, 137 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.44 mM KH2PO4, 4.1 mM NaHCO3, 20 mM HEPES) was added between the two electrodes (the ITO conductive substrate being the cathode) of a BTX square-wave pulse electroporator (ECM830, Genetronics, CA). Several combinations of electroporation parameters, such as electric field (50 V cm−1 to 800 V cm−1), pulse-width (0.1 ms to 100 ms), and number of pulses (1–8) were applied to the electrodes. Additional discussion of the strategy for optimization of electroporation conditions for different cell lines can be found in the legend accompanying Supplementary Fig. 2. Propidium Iodide (40 µg/ml in electroporation buffer) was electroporated with each parameter set to determine transfection efficiency and cells were imaged 2 hr post-electroporation. Electroporated cells were incubated with a lentivirus encoding green fluorescent protein GFP (viral-GFP particles) for 24 hr to assess cell viability. Alternatively, cell viability was evaluated using 1 µg ml−1 of Calcein AM (Invitrogen). Alexa-488 fluor conjugated siRNA (Qiagen) was used at a concentration of 5 µM in electroporation buffer as a test for successful electroporation of siRNA molecules. Control (no electroporation) parameters in each case were 100 V cm−1, 1 ms and 1 pulse.

Parallel electroporation within microwell arrays

A 484-microwell array was created by essentially sticking a laser cut coverlay (FlexTac BGA Rework Stencil 22×22 array, thickness 100 µm, CircuitMedic, MA) to the center of a conductive ITO coated microscope slide using the pre-coated adhesive provided on the backside. Microwells were 500 µm in diameter and separated at 1 mm inter-well distance. The bonded microwell arrays were sterilized, washed with PBS and then soaked in 1 µg ml−1 fibronectin (Sigma) to increase cell adhesion within the microwells. The microwells were then washed in PBS to remove the unbound fibronectin and placed in a 10 cm tissue-culture dish. Thereafter, 7.5 × 106 HEK 293T cells were seeded into the tissue-culture dish containing the microwell array and placed in the incubator. 1 hr post-seeding the arrays were washed to remove unbound cells and fresh media was added.

The 484-microwell array ITO slides containing the microscale cultures were removed from the incubator after 24 hr. The left and right flanks of the ITO slides were wiped dry, keeping the microwell array wet with residual media. A hydrophobic barrier pen (Ted Pella, CA) was used to draw hydrophobic barriers on both the left and right flanks of the microwell array to restrict the electroporation buffer to the top of the microwell array. A stainless steel anode was placed at 1 mm space from the ITO surface using glass spacers. A stainless steel electrode provided contact to one end of the ITO slide to be used as a cathode. In the case of using a double cathode scheme, a conductive copper tape (3M Inc., MN) electrically shorted both ends of the ITO slide. Ice cold electroporation buffer containing the molecules to transfected (propidium iodide at 40 µg ml−1, Alexa-488 fluor conjugated siRNA at 5 µM or a plasmid encoding GFP at 300 µg ml−1) were added to the space between the anode and the microwell array. Electroporation was simultaneously conferred in all 484-microwells using an optimal parameter set as determined during optimization experiments (500 V cm−1, 1 ms pulse-width and 1 pulse). Thereafter, the microwell array was placed back in media and incubated for an additional 2 hr, with subsequent staining for viability using Calcein AM (Invitrogen, CA). Thereafter, the microculture array was fixed with 10% formalin (Sigma) and stored at 4°C. In the case of plasmid electroporation, GFP expression was assessed at 24 hr post-electroporation.

Electroporation of primary mouse macrophages in microwell arrays

Primary mouse macrophages were isolated from 2- to 3-month-old male C57BL/6 mice as described 16. Thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were plated on top of microwell ITO substrates in six-well plates at density of 1 × 106 cells per well. This seeding density achieved 30–50% confluence/microwell at 24 hr. Electroporation of propidium iodide was conducted as described above for ITO pieces. Parameters tested included electric field, pulse-width, and number of pulses. 2 hr post-electroporation, a live assay was conducted using Calcein AM (Invitrogen, CA) to determine remaining viability and nuclei stained with Hoechst (Invitrogen, CA) to determine the total number of cells within the microwells.

Finite element modeling and analysis of electric field

To study the variations of electric field on the microwell array region on an ITO slide, finite element modeling and analysis was conducted in FEMLAB (Comsol, CA) using the conductive DC module. The ITO surface was modeled with a thickness of 200 nm and material properties of conductivity 3.75e6 S m−1 and surface resistivity of 4 Ω sq−1. The anode was modeled as a positive contact (voltage 50 V) at a distance of 1 mm from the surface of the ITO, which served as the cathode (voltage 0 V). The intermediate region was modeled as a conductive media of conductivity 1.6 S m−1, equivalent to the measured conductivity of the electroporation buffer. After meshing and solving, the electric field intensities parallel to the z-axis (normal to the ITO surface) were plotted for analysis.

Cellular imaging and analysis

Cellular imaging of microscale cultures within individual microwells was carried out on a Nikon eclipse TE-2000U inverted fluorescence microscope with a cooled ccd camera (CoolSnap fx, Photometrics, AZ). Cellular images were analyzed in NIH ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij) for analysis of transfection, GFP expression and viability. High-resolution imaging of the entire 484-microwell array was conducted on a ProScanArray HT confocal laser slide scanner (Perkin Elmer, MA) and the images were analyzed with ImaGene software (BioDiscovery, CA) to determine individual microwell fluorescence intensities.

Microarraying within microwell arrays

Microarraying was carried out on a Biorobotics MicroGrid II microarrayer (Genomic Solutions, IL). To align the microwell array with the microarraying pins, a regular glass microscope slide was spotted with printing buffer and imaged on the ProScanArray HT confocal laser slide scanner (Perkin Elmer, MA). Similarly, the microwell array to be spotted within was imaged on the scanner at the identical settings. The two images were then overlaid in ImaGene software (BioDiscovery, CA) and the X and Y offset of the microwells from the microarrayed spots was determined. The microarrayer was then recalibrated with the offsets. Upon confirmation of precise alignment of the microwell array and the microarrayed spots in the imaging software, Alexa Fluor 488-labeled siRNA was microarrayed directly within the microwells. A stealth pin SMP10B (Arrayit, CA) with a spotting diameter of 365 µm was used for the arraying.

Results

Optimization of electroporation on ITO

Because electroporation can be used to introduce nucleic acids with high efficiency into virtually any cell type, including primary cells, we chose this method to form the basis of our platform design. As a first step, we strived to identify electroporation parameters that could be used to introduce exogenous molecules from solution into cells growing on transparent ITO with high efficiency and minimal loss of cell viability. A variety of electroporation parameters (differential voltage, pulse-width and number of pulses) were optimized for electroporation of propidium iodide into HEK 293T cells cultured on ITO coated glass substrates diced into pieces (protocol and electroporation setup shown in Supplementary Fig. 1A,B). Propidium Iodide is a membrane impermeant nucleic acid stain that is excluded from cells refractory to entry of exogenous molecules. Staining with propidium iodide is an indication that the cell has become receptive to entry of molecules from outside the cell that would generally be excluded. To confirm that propidium iodide staining is not simply a consequence of cell permeability due to cell death, electroporated cells also underwent a viral infection viability assay. Electroporated cells were incubated with a lentivirus encoding green fluorescent protein GFP (viral-GFP particles) for 24 hr. Live cells (not lysed by electroporation) are expected to maintain their integrity, be permissive to viral infection, and express GFP. Because viral infection, integration, and transgene expression (in this case GFP) are dependent on the cellular machinery of its host, this is a sensitive assay to evaluate the health of electroporated cells. Fig. 1A shows three representative parameter sets with their respective transfection and viability assays. The parameter set 500 V cm−1, 1 ms (pulse-width) and 1 pulse resulted in optimal (>99%) transfection efficiency and high viability for electroporating propidium iodide. Incubation of transfected cells with viral-GFP particles showed that cells remained viable after electroporation (Fig. 1B). Similar experiments were conducted with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated siRNA and the optimal electroporation parameters resulted in >99% transfection efficiency (Fig. 1C). The protocol on ITO-glass cut pieces provides a convenient method to optimize electroporation parameter sets that can be repeated if the cell type, exogenous molecule or other factors are changed, as is shown for human epithelial carcinoma (HeLa) cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). Certain electroporation parameter sets caused the ITO substrates to brown at the surface and were avoided (Supplementary Fig. 1C,D).

Figure 1.

Electroporation of exogenous molecules into HEK 293T cells growing on ITO without microwells. A) Phase contrast, transfection assay (Propidium Iodide fluorescence 2 hrs post-EP) and viability assay (Calcein AM 1 day post-EP) images for three different electroporation parameter sets (electric field intensities 100 V cm−1, 500 V cm−1 and 800 V cm−1 respectively, at constant pulse width of 1 ms and 1 square pulse). A scratch (not shown) was made on each of the ITO pieces to locate the culture area for the two assays at different time points. B) Further confirmation of viability post-EP. Cells electroporated with propidium iodide (top row: red) using the optimal electroporation parameter (500 V cm−1, pulse width 1 ms and 1 square pulse) were virally transduced with viral-GFP particles and assayed for viability 24 hr post-EP (bottom row: green). GFP expression is a confirmation of cell viability. C) Electroporation of Alexa Fluor 488- conjugated siRNA molecules using two electroporation parameter sets (100 V cm−1 and 500 V cm−1; constant pulse width of 1 ms and 1 square pulse) and assaying for transfection using Alexa Fluor 488 compatible excitation/emission filters 2 hr post-EP. EP: Electroporation.

Cellular cultures within a microwell array

Microwells offer numerous advantages for a miniaturized genomic screening platform: they can provide a physical marker for imaging and a barrier for microscale cultures to be contained. To evaluate the prospects of utilizing microwells in a high-throughput screening platform, a simple method was used to create microwell arrays on ITO-coated glass slides using laser-cut coverlays (Fig. 2A,B). Microwells were 500 µm in diameter and separated at 1 mm inter-well distance. These dimensions were chosen to ensure that enough cells can be accommodated per microwell to assess phenotypes with statistical power. Microscale cultures were then obtained within a 484-microwell array by flooding the array in a tissue culture dish and washing away unbound cells (Fig. 2C). The cells were subsequently electroporated and analyzed (Fig. 2 D,E). Prior to electroporation, phase contrast and cell viability (assessed with the vital dye Calcein AM) images of HEK 293T cells cultured within the microwell array were taken 24 hr post-seeding (Fig. 3A). All 484-microwells of the array had a similar degree of confluence, indicating that this approach to seed and culture cells in microwells is a robust method for obtaining uniform cell density. To assess the compatibility of the microwells with sensitive cell types such as primary cells, primary mouse macrophages were obtained and seeded within the microwell array. These cells adapted to the microwells with ease; no macrophage activation was seen (Fig. 4A).

Figure 2.

Schematic showing the step-by-step process from creation of microwell arrays to image analysis after electroporation. A) Bonding of a pre-cleaned ITO slide with a laser cut microwell array stencil/coverlay. B) Sterilization and coating with fibronectin to enhance cellular adhesion. C) Seeding of mammalian cells into the microwell array by placement of the substrate and cells in a tissue culture dish. 1 hr after seeding, the dish was gently washed to remove unbound cells. Cells inside the microwells experience minimal flow stress and remain attached during this step. D) Electroporate substrate using either a single or double cathode scheme. Post-electroporation incubation. E) Image acquisition of either single microwells under a microscope or whole slide scanning.

Figure 3.

Culture and electroporation of HEK 293T cells in microwell arrays on ITO-coated glass slides. A) Culture of HEK 293T cells within individual microwells 1 day after seeding. Top row: Phase contrast image of cells. Bottom row: live assay of cells using Calcein AM within microwells. B) Electroporation of HEK 293T cells growing within microwell arrays. Electroporation parameter set used: 500 V cm−1, 1 ms pulse-width and 1 square pulse. Top row: brightfield image of cells post-electroporation. Bottom row: fluorescence image of cells at appropriate molecule compatible excitation/emission spectra. Left column: electroporation of propidium iodide. Middle column: electroporation of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled siRNA. Right column: electroporation of plasmid encoding GFP. C) Estimation of transfected cell count in an individual microwell using software identification of the microwell edges as physical markers for identification of microscale culture spatial locations.

Figure 4.

Electroporation of primary macrophage cells within microwells and automated image analysis of microcultures. A) Electroporation of primary macrophages within microwell arrays. All images taken at 2 hr post-electroporation. Left column: Phase contrast image post-EP. Middle column: Transfection assay using Propidium Iodide post-electroporation. Right column: Live assay with Calcein AM post-EP. Top row: Control pulse (CP) 100 V cm−1, 1 ms pulse-width and 1 square pulse. Bottom row: Electroporation pulse (EP) 600 V cm−1, 1 ms pulse-width and 5 square pulses at 1 Hz. B) Automated microwell edge detection and image analysis estimating total cell nuclei (Hoechst), transfected cells (Propidium Iodide) and viable cells (Calcein AM) in individual microwells of the images shown in Fig. 4A.

The first step of phenotypic evaluation after a screen is completed is usually the identification of the spatial location of the cellular culture of interest on the substrate. For a miniaturized platform consisting of arrayed microscale cultures, the use of microwells may enhance the accuracy of image analysis and phenotype deconvolution. Imaging system stages are usually pre-programmed 10 to the exact location of the microscale cultures on the substrate, which leaves the task of identifying the spatial location of cellular cultures to the image analysis step. Considering equipment errors and tolerances, in the absence of physical markers, image analysis can at best estimate the location of the microscale cultures. With a physical marker, in this case the edge of the microwells, the spatial location of the microscale cultures can be identified with certainty (Fig. 3C). The software first identifies the edges of the microwells, which in turn determines the center of the microscale culture position. The software then crops out the microscale culture removing the unwanted microwell edges. With subsequent modules for thresholding, segmentation, and object identification, a variety of phenotypic analysis can be accomplished (in this example simply identifying 890 electroporated cells within a microwell). The presence of the microwells dramatically enhances the ability to precisely identify the microscale cellular cultures on the substrate, thus increasing the accuracy of phenotypic annotation.

Electroporation within microwells

Having obtained electroporation parameters for high transfection efficiency of exogenous molecules from solution into adherent cells on ITO slides, and having tested the feasibility of growing cellular microscale cultures within microwells created on this substrate, in-situ electroporation within microwells was then evaluated. HEK 293T cells growing within microwells were electroporated with three different exogenous molecules: propidium iodide, siRNA and plasmid DNA encoding GFP (Fig. 3B). Electroporation of HEK 293T cells within microwell arrays was conducted using the electroporation parameter set described above for cultures on ITO-coated glass pieces without microwells (500 V cm−1, 1 ms, 1 pulse) and with the exogenous molecule in solution. This resulted in transfection efficiencies >99% for propidium iodide and siRNA molecules within the microwells. It is interesting to note that the optimal electroporation parameters are essentially unchanged, even with the presence of a microwell array that effectively insulates a major region of the substrate leaving only small openings for the electroporation current to flow. This may be because the current density at the ITO-cell interface under constant voltage conditions remains essentially the same, even though the total current between cathode and anode varies due to a change of effective electrode area. With similar current density values at the interface, adherent cells in microwells should exhibit similar electroporation efficiency 17, as is the case in these experiments. Mouse primary macrophages were also successfully electroporated within the microwells (Fig. 4A). A different electroporation parameter set (600 V cm−1, 1 ms, 5 pulses) proved optimal for these cells. A viability assay indicated that most primary cells remained healthy post-electroporation. Microwell edge identification, microscale culture recognition, and cellular/nuclear object identification was carried out for images obtained in three distinct fluorescence channels (Hoechst: total cell nuclei count; Propidium Iodide: transfected cells; Calcein AM: viable cells). High transfection efficiency without loss of viability can be achieved in these primary cells (Fig. 4B). Measurements indicate cell viability to be 86% (for a control pulse) and 93% (for an electroporation pulse). These results indicate that electroporation itself does not induce cell death.

Highly parallel electroporation in a 484-microwell array

Next, we evaluated the electroporation efficiency in the 484-microwell array to determine transfection variability across the ITO coated glass slides under different cathode schemes. These slides have a surface resistivity of ~4–8 Ω sq−1, which could be high enough to ensure the surface conductivity required for electroporation, but low enough to cause noticeable voltage differences across the substrate from the point of electrode contact. Thus, it was expected that by increasing the cathode contacts on ITO, the voltage loss across the slide might be reduced. To examine this possibility, finite element analysis simulations were used to model the electric field pattern at the surface of the microwell array for a single cathode or a double cathode scheme. They predict very contrasting electric field patterns (Fig. 5A, top and bottom). With a single cathode, there is wide variation of electric field across the array (Fig. 5A, top and Fig. 5B, left graph). A double cathode scheme significantly reduces electric field variation (Fig. 5A, bottom and Fig. 5B, right graph).

Figure 5.

Effect of electrode configuration on electroporation efficiency variation across microwell array substrate. A.) Finite Element Analysis FEMLAB (Comsol, CA) simulations of electric field across a 484 microwell array on a conductive microscope slide using either a single or double cathode configuration. B) Analysis of mean and standard deviation, as a result of the simulations, by binning electric fields at the center of each microwell of the array using the single or double cathode configuration. Individual columns are binned at 10 V cm−1. Et shows the estimated threshold of electric field required for ~50% electroporation efficiency relative to maximum as determined by matching experimental data to simulated electric field values. C) Parallel electroporation of mammalian cells in 400 microwells of the array (the outermost microwells of the 484 microwell array were excluded to avoid potential edge effects) with propidium iodide using previously optimized parameters with the single cathode configuration or D) double cathode configuration. Insets on the left and right show a zoomed out 4×4 array from the left and right sides of the larger 484 microwell array. Bar graphs indicate electroporation efficiency (measured as relative fluorescent units, RFU, of internalized propidium iodide) using a single or double cathode configuration. Individual bars represent mean values across the 20 rows of a single column plotted left to right of the microwell array. E) Cell viability and transfection efficiency of a 400 microwell array 1 hr post-electroporation, with a double cathode set up. The adjacent plots on the top and side of each image indicate fluorescence intensity in the central row and column in each case.

These predictions were tested in experiments conducted on a 400-microwell array (the outer rows and columns were omitted from the 484-microwell array to avoid possible edge effects) using propidium iodide as the exogenous electroporated molecule. Parallel electroporation of the microwell array with a single cathode scheme resulted in clear variation in transfection efficiency from left to right (Fig. 5C). In contrast, a double cathode scheme yielded more uniform electroporation across the microwell array (Fig. 5D). These results were applied to calculate the threshold electric field, Et, necessary to obtain greater than 50% transfection of the maximum observed in any well in the microwell array. From the experimental data the column position where the efficiency dropped to ~50% was determined (Fig. 5C, right bar graph). The Et electric field value from the simulation was deemed to be ~250 V/cm (Fig. 5A). All microwells in the double cathode scheme are expected to be above this threshold, in sharp contrast to the single cathode scheme (Fig. 5B). This prediction was empirically borne out, as most microwells in the double cathode scheme exhibited 50% or greater electroporation efficiency when compared to the maximum (Fig. 5D, right bar graph). To evaluate the ability of the modified double cathode scheme to assure uniform transfection efficiency and cellular viability across the entire 400-microwell array, transfection efficiency and cell viability were measured post-electroporation. Fluorescent intensity plots were generated to profile the changes observed for the central rows and columns for each of these assays (Fig. 5E). These results indicate that a double cathode method minimizes variation in transfection efficiency while maintaining cell viability across the entire array. We also tested electroporation of a different molecule, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated siRNA, within the microwell array using the double cathode method. Similar results were obtained; transfection efficiency was relatively uniform across the array (Fig. 6).

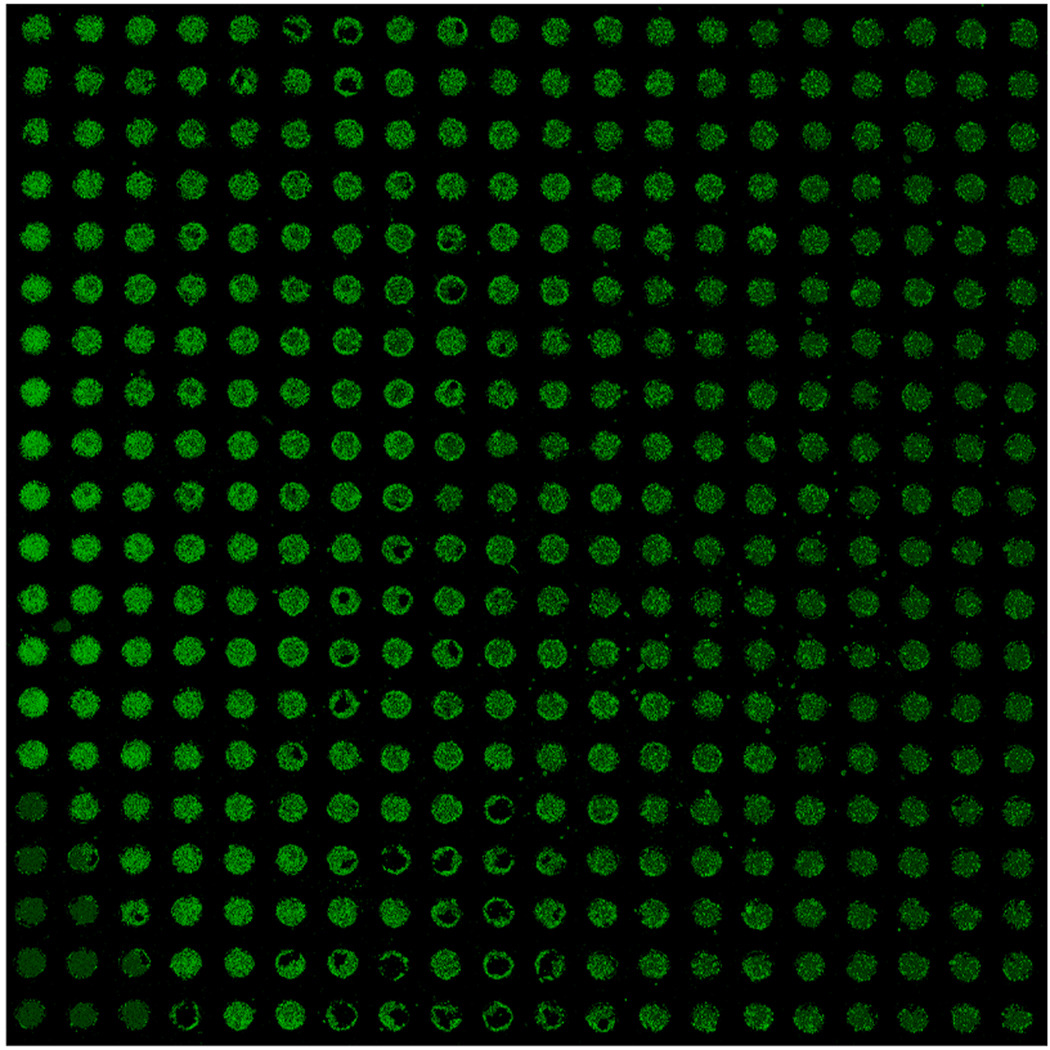

Figure 6.

Parallel electroporation of Alexa 488 fluor-siRNA into HEK 293T cells contained within the microwell array. Electroporation was conducted using the double cathode method with an electric field intensity of 500 Vcm−1, 1 ms pulse-width and 1 square pulse. Two hours post-electroporation, the cells were washed in PBS, fixed and scanned for green fluorescence on a ProScanArray HT confocal laser slide scanner (Perkin Elmer, MA). Prior to scanning, the microwell stencil was removed with forceps to eliminate auto-fluorescence from the stencil material. The artifact in the lower-left corner is due to handling with forceps.

Microarraying within microwells

Since our ultimate goal is to conduct multiplexed parallel electroporation of thousands of different molecules, a necessary component of our envisioned miniaturized high-throughput genetic screening platform will be the ability to quickly load large libraries of molecules onto the microstructure-bearing substrates. Standard microarray spotters allow microarraying of libraries (nucleic acids, proteins, and carbohydrates) from well-plates onto microscope slides with micron step resolution. These microarrayers are an excellent tool to achieve ‘world-to-chip’ ability. However, microarrayers are not usually constrained to spot within microwell structures; therefore they do not require precise alignment with pre-existing micro-sized features on the substrate. With the incorporation of microwell arrays onto the substrate, the requirement to align the microarrayer and spot precisely within individual microwells becomes a critical issue. One way to overcome this problem is to use a CCD camera in conjunction with the microarraying head to image the substrate and locate the features prior to printing. However, most standard microarrayers do not include these image-capable heads. As an alternative, we developed a simple iterative method to align microwells with the microarrayer to insure accurate spotting on the experimental substrate. First, a blank microscope slide is spotted with printing buffer using the same spotting parameters (inter-spot distance and array size) to be used on the final microwell array slide. This blank spotted slide and the microwell array-containing slide are then imaged independently in a slide scanner. Next, the two images are overlaid using image analysis software to determine X-Y alignment errors (Fig. 7A). Re-calibration of the microarrayer with these errors enables spotting to take place precisely within the microwell array. Using this approach, we were able to consistently microarray within the center of microwells (Fig. 7B). The average size of the spots obtained was 363 ± 17 µm which correlates well with the manufacturer’s spot size specification (365 µm) for the array pin used for spotting.

Figure 7.

Microarraying within microwells using an iterative process of imaging and calibration. A) A blank slide is spotted with printing buffer to determine the X-Y offset error from a microwell array slide to be printed on. Both slides are independently scanned and their images overlaid in software to determine the offset. B) After re-calibrating the microarrayer with the offset error, Alexa Fluor 488-labeled siRNA was spotted directly into alternating wells of the microwell array.

Discussion

To fully realize the potential of genome-wide cell-based genetic screening to annotate the mammalian genome, it is imperative that a next generation screening platform be developed, one that miniaturizes the screening process, thus reducing capital and reagent costs. Ideally, such a platform should possess at least five features: 1) the genetic molecules of a library must be loaded with ease into spatially separated microscale regions on a single substrate; 2) the cells of interest must thrive in the “loaded” substrate, but their motility should be restricted to individual microscale regions; 3) cells must be transfected in an efficient, highly-parallel, uniform manner at a controllable time point; 4) the method used to introduce nucleic acids into microscale cultures should be effective for both cell lines and primary cells; 5) the substrate containing the transfected microscale cultures must be compatible with existing automated imaging systems and analysis tools to allow for seamless identification of phenotypes.

As a first step towards these goals, here we have demonstrated the use of microwell arrays for parallel electroporation of exogenous molecules into microscale cultures on a single substrate. In these experiments, a 484-microwell array was created on a conductive and transparent ITO microscope dimension slide by bonding a laser-cut adhesive coverlay. The microwells allowed for consistent culture of mammalian cells (both primary cells and immortalized cell lines) within the array. These coverlays served as a quick and easy way to create microwell arrays for initial lab-on-a-chip experiments. However, to obtain precise straight edges and defined geometric features, microfabrication techniques using photopatternable polymers will need to be incorporated in future development.

ITO conductive slides have previously been used to achieve efficient electroporation of exogenous molecules into mammalian cells 18, but their utility in arrays of microscale cultures of the kind required to perform genome-wide genetic screens has not been explored. When the desired application is that of high-throughput screening of genetic libraries in mammalian cells, a critical requirement is to segregate both the individual nucleic acids and the cellular cultures into microscale domains on a single substrate prior to electroporation. Our results demonstrate that it is possible to create an array of microscale cellular cultures on conductive substrates using a microwell-based approach that allows for parallel electroporation of exogenous molecules (propidium iodide, siRNAs and plasmid DNA) from solution into cells contained within the microscale domains. With a single cathode electroporation scheme, we observed that voltage drops caused by the surface resistivity of ITO result in a non-uniform electric field across the microwell array and variable electroporation efficiency across the substrate. One way to resolve this issue would be to set the anode at a slight angle (~1 degree) above the cathode, but this requires precisely machined parts and spacers 18. A simpler alternative we have developed is that of using simultaneous multiple contacts on the ITO cathode to reduce voltage drops across the substrate. This scheme results in uniform electroporation efficiency across the microwell array, allowing for highly parallel electroporation on a single substrate. Future designs may incorporate additional electrodes and possibly patterns of cathode on the ITO to further optimize uniformity of electric field distribution.

The use of microwells significantly enhances the ability to identify the spatial location of microscale cellular cultures and improves the image acquisition and analysis steps. Microscale cultures can also be created using purely surface chemistry techniques to create patterned regions of cell adhesion/non-adhesion 14, but the lack of a physical marker makes it difficult to precisely identify the location of the cultures during imaging and analysis. Cartesian or angular shifts during imaging can complicate identification of the microscale domains and hamper downstream image analysis, obscuring phenotype evaluation. The microwell edges provide a clear physical indication of the spatial location of the cultures; they enable centering of individual microscale images during image processing and analysis. Moreover, the microwells provide physical containment for cells transfected with an individual nucleic acid, restricting migration and contamination of neighboring cellular cultures transfected with other nucleic acids. This feature may be particularly relevant for time-lapse studies, in which cells are monitored multiple times after transfection. Another advantage of microwells is that microscale cultures experience significantly lower flow shear stresses as indicated by simulations 19. This may minimize cell stripping during experimental protocols that could lead to inter-spot contamination. In the future it may be possible to use a combination of microwells and surface chemistry on the plateau areas to further prevent inter-well cell motility 20

The ability to transfer large libraries (i.e. genome-size) of genetic molecules swiftly and precisely is an important requirement for a miniaturized high-throughput screening platform. Contact pins or non-contact pin-less spotters offer a potential approach to transfer libraries of genetic molecules from stock well plates to the miniaturized platform. However, instrument and substrate edge tolerances make it challenging to ensure high-precision spotting of molecules within microscale regions and geometric microstructures such as the microwells we have described. To address this issue, we have developed a simple iterative process of imaging the microwell array and re-calibrating the microarrayer using overlaid images of blank slide prints that enables accurate spotting of genetic molecules within the microwell arrays. The precision of the spotting will increase further once microfabrication techniques are applied to create the microwell array and high-precision-cut substrates are used.

Here, we have demonstrated the ability to achieve parallel electroporation of exogenous molecules in solution into cells contained in a 484-microwell array. Maintaining similar microwell dimensions, and introducing changes to the microwell array design to scale the technology, it should be possible to conduct a genome-wide screen (~25,000 molecules) 21 in mammalian cells in a single substrate the size of a 96-well plate. However, an important component that remains to be explored is the ability to bind the spotted nucleic acid molecules within the microwells, so as to ensure their stability during cell culture and their subsequent release at the time of electroporation. Surface chemistry techniques will prove useful to attain this aim 22, but more experimentation is needed with substrates such as ITO to optimize binding and release parameters.

In summary, we have found conditions to achieve parallel introduction of exogenous molecules into primary and immortalized mammalian cells cultured within a 484-microwell array created on an ITO slide. The microwell array allows for the consistent generation of segregated microscale cultures. The microwell edges enable precise identification of the spatial location of the microscale cultures during image analysis. Finally, these microwell arrays are fully compatible with standard microarraying equipment, allowing swift transfer of nucleic acid libraries from stock plates onto the miniaturized platform. These advances provide a basis for the creation of a miniaturized high-throughput genetic screening platform for mammalian cells.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Perrimon N, Mathey-Prevot B. Genetics. 2007;175:7–16. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.069963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moffat J, Sabatini DM. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:177–187. doi: 10.1038/nrm1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannon GJ, Rossi JJ. Nature. 2004;431:371–378. doi: 10.1038/nature02870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Nature. 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho CY, Koo SH, Wang Y, Callaway S, Hedrick S, Mak PA, Orth AP, Peters EC, Saez E, Montminy M, Schultz PG, Chanda SK. Cell Metab. 2006;3:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rines DR, Gomez-Ferreria MA, Zhou Y, DeJesus P, Grob S, Batalov S, Labow M, Huesken D, Mickanin C, Hall J, Reinhardt M, Natt F, Lange J, Sharp DJ, Chanda SK, Caldwell JS. Genome Biology. 2008;9 doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-2-r44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziauddin J, Sabatini DM. Nature. 2001;411:107–110. doi: 10.1038/35075114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehner B, Fraser AG. Nat Methods. 2004;1:103–104. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1104-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mousses S, Caplen NJ, Cornelison R, Weaver D, Basik M, Hautaniemi S, Elkahloun AG, Lotufo RA, Choudary A, Dougherty ER, Suh E, Kallioniemi O. Genome research. 2003;13:2341–2347. doi: 10.1101/gr.1478703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheeler DB, Carpenter AE, Sabatini DM. Nature genetics. 2005;37 Suppl:S25–S30. doi: 10.1038/ng1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva JM, Mizuno H, Brady A, Lucito R, Hannon GJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6548–6552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400165101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato K, Umezawa K, Miyake M, Miyake J, Nagamune T. Biotechniques. 2004;37:444–448. 450, 452. doi: 10.2144/04373RR02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamauchi F, Kato K, Iwata H. Langmuir. 2005;21:8360–8367. doi: 10.1021/la0505059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee WG, Demirci U, Khademhosseini A. Integrative Biology. 2009;1:242–251. doi: 10.1039/b819201d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molteni V, Li X, Nabakka J, Liang F, Wityak J, Koder A, Vargas L, Romeo R, Mitro N, Mak PA, Seidel HM, Haslam JA, Chow D, Tuntland T, Spalding TA, Brock A, Bradley M, Castrillo A, Tontonoz P, Saez E. J Med Chem. 2007;50:4255–4259. doi: 10.1021/jm070453f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain T, Muthuswamy J. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1004–1011. doi: 10.1039/b707479d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raptis L, Firth KL. DNA Cell Biol. 1990;9:615–621. doi: 10.1089/dna.1990.9.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moeller HC, Mian MK, Shrivastava S, Chung BG, Khademhosseini A. Biomaterials. 2008;29:752–763. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochsner M, Dusseiller MR, Grandin HM, Luna-Morris S, Textor M, Vogel V, Smith ML. Lab on a Chip. 2007;7:1074–1077. doi: 10.1039/b704449f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.C. I. Human Genome Sequencing. Nature. 2004;431:931–945. doi: 10.1038/nature03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore EJ, Curtin M, Ionita J, Maguire AR, Ceccone G, Galvin P. Anal Chem. 2007;79:2050–2057. doi: 10.1021/ac0618324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.