Abstract

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy is being used to determine the structures of membrane proteins involved in the regulation of apoptosis and ion transport. The Bcl-2 family includes pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins that play a major regulatory role in mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis or programmed cell death. The NMR data obtained for 15N-labeled anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL in lipid bilayers are consistent with membrane association through insertion of the two central hydrophobic α-helices that are also required for channel formation and cytoprotective activity. The FXYD family proteins regulate ion flux across membranes, through interaction with the Na+, K+-ATPase, in tissues that perform fluid and solute transport or that are electrically excitable. We have expressed and purified three FXYD family members, Mat8 (mammary tumor protein), CHIF (channel-inducing factor) and PLM (phospholemman), for structure determination by NMR in lipids. The solid-state NMR spectra of Bcl-2 and FXYD proteins, in uniaxially oriented lipid bilayers, give the first view of their membrane-associated architectures.

Keywords: NMR, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, FXYD, Mat8, PLM, CHIF, apoptosis, membrane proteins, lipid bilayers

INTRODUCTION

NMR spectroscopy is ideally suited for the structure determination of membrane proteins in lipid environments. Solution NMR methods for structure determination can be utilized on samples consisting of proteins dissolved in lipid micelles, while solid-state NMR methods can be applied to samples of membrane proteins in planar lipid bilayers.1,2 The latter approach is especially attractive because it enables structures to be determined in a native-like environment. Furthermore, since the lipid bilayers are oriented with respect to the applied magnetic field, the samples preserve the intrinsic directional character of membrane protein structure and function. For membrane proteins that can be expressed, isotopically labeled, and purified chromatographically, reconstitution in oriented lipid bilayers gives single-line spectra with line widths that rival those from single crystals3 and with characteristic patterns that directly reflect protein structure and topology.4–6 This direct relationship between spectrum and structure provides the basis for a method that permits the simultaneous sequential assignment of resonances and measurement of orientational restraints for backbone structure determination in the two-dimensional solid-state NMR 1H/15N PISEMA spectra from a limited set of uniformly and selectively 15N-labeled samples.7,8 Here we describe solid-state NMR structural studies of two families of membrane-associated proteins involved in the regulation of apoptosis, or programmed cell death, and ion transport. The spectra provide the first view of these protein structures in membranes, and also provide the starting point for three-dimensional structure determination which should give significant insights to their biological functions.

Bcl-2 family proteins

The Bcl-2 family includes both anti-apoptotic, or cyto-protective, proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL) and pro-apoptotic, or death-promoting, proteins (Bid, Bax).9–12 Imbalances in their relative expression levels or activities result in insufficient cell death, as in cancer and autoimmunity, or excessive cell death, as in Alzheimer’s disease, stroke and AIDS. The Bcl-2 proteins exert their apoptotic activities through dimerization with other Bcl-2 family proteins, binding to other non-homologous proteins, and through the formation of ion channels or pores, that are believed to play an important role in apoptosis by perturbing mitochondrial physiology leading to the release of cytochrome c. Their function is also regulated by subcellular location, as they cycle between soluble and membrane-bound forms. For example, anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL is found predominantly in mitochondrial, endoplasmic reticulum, or nuclear membranes, and pro-apoptotic Bax is found in the cytosol when inactive, but is stimulated by death signals to insert in the mitochondrial outer membrane, where it participates in cytochrome c release and mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis.

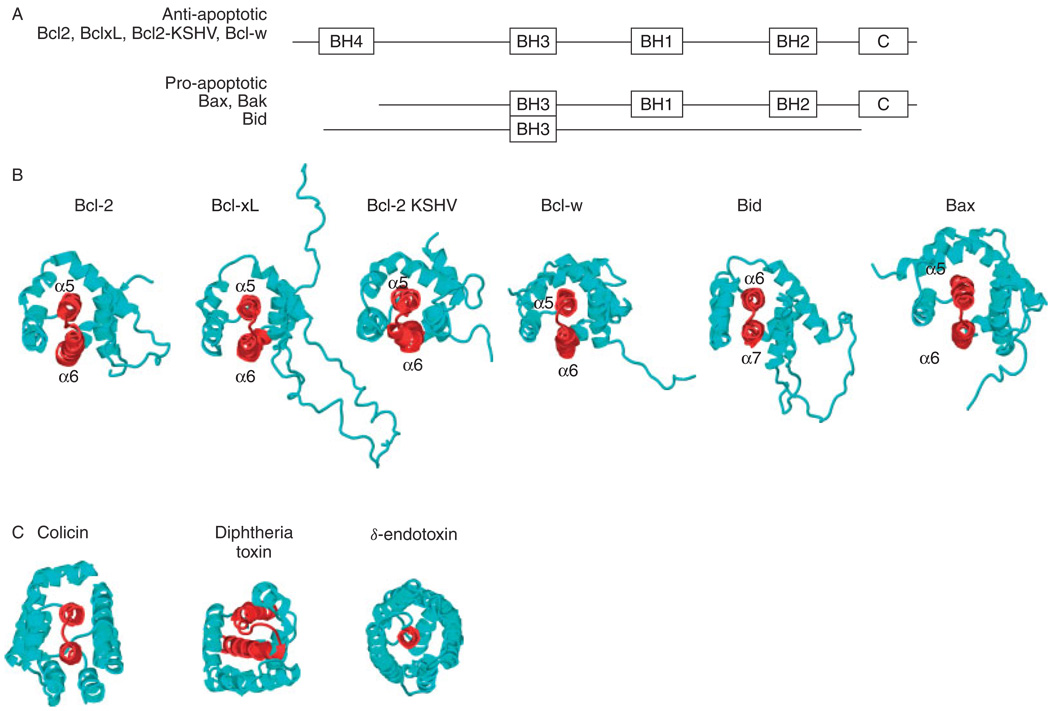

The Bcl-2 domains required for apoptotic activity and dimerization have been determined by deletional and mutational analyses, and corroborated by their solution structures, solved primarily by NMR spectroscopy.13–23 The proteins are built in modules of up to four highly conserved Bcl-2 homology (BH) domains, of which the BH3 domain is highly conserved and essential for cell killing activity and for oligomerization with other family members [Fig. 1(A)]. Several family members also have a hydrophobic C-terminal domain, which is probably involved in membrane association. The solution structures are very similar [Fig. 1(B)], despite the lack of extensive sequence homology, and consist of two central and largely hydrophobic or α-helices, flanked on two sides by amphipathic helices and a large flexible loop which connects the first two helices. Notably, the structures also bear a striking similarity to those of the pore-forming domains of bacterial toxins, known to form ion channels in bacterial membranes [Fig. 1(C)], and indeed, several Bcl-2 proteins, including Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, Bax and Bid, form ion channels under conditions where bacterial toxins also form channels.24–27 Solution NMR studies of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL and pro-apoptotic Bax, in lipid micelles, indicate that the structures in membrane environments are very different.20,28 The three-dimensional membrane-associated structures are not known, but may be key to the functional differences between pro- and anti-apoptotic members of the family. The expression and purification of several Bcl-2 family proteins have been described,29–31 and here we present the first structural studies in lipid bilayer membranes.

Figure 1.

Conserved Bcl-2 homology (BH) domains (A) and solution structures (B) of the Bcl-2 protein super family.13–23 The PDB file numbers of the structures are given in parentheses for Bcl-2 (1G5M), Bcl-xL (1LXL), Bax (1F16), Bid (2BID, 1DDB), KSHV-Bcl-2 (1K3K3) and Bcl-w (1O0L, 1MK3). The structures are highly homologous to those of (C) the channel-forming domains of the bacterial toxins, colicin (1COL), diphteria toxin (1DDT) and δ-endotoxin (1DLC).

FXYD family proteins

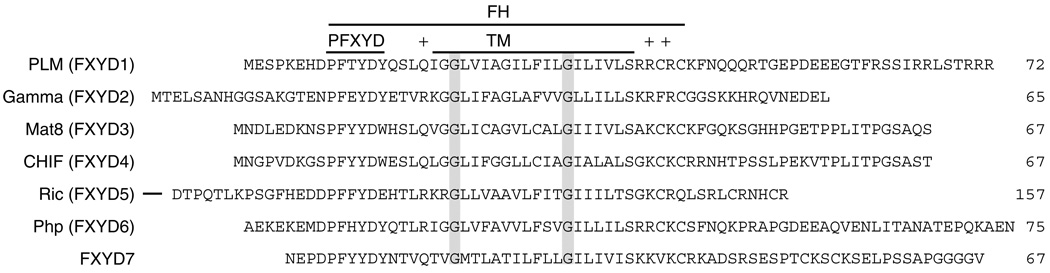

The FXYD family proteins are expressed abundantly in tissues that perform fluid and solute transport (breast/mammary gland, kidney, colon, pancreas, prostate, liver, lung and placenta), or that are electrically excitable (muscle, nervous system), where they function to regulate the flux of transmembrane ions, osmolytes and fluids.32 The protein sequences are highly conserved through evolution, and are characterized by a 35-amino acid FXYD homology (FH) domain, which includes the transmembrane (TM) domain (Fig. 2). The short motif PFXYD (Pro, Phe, X, Tyr, Asp), preceding the transmembrane domain, is invariant in all known mammalian examples, and identical in other vertebrates, except for the proline. X is usually Tyr, but can also be Thr, Glu or His. In all these proteins, conserved basic residues flank the TM domain, the extracellular N-termini are acidic and the cytoplasmic C-termini are basic. PLM (phospholemman) is one of the best characterized members of this family, and the major substrate of hormone-stimulated phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase A and C in the heart.33 CHIF (channel-inducing factor) is upregulated by aldosterone and corticosteroids in mammalian kidney and intestinal tracks, where it regulates Na+ and K+ homeostasis.34 Mat8 (mammary tumor protein 8 kDa) is expressed in breast, prostate, lung, stomach, and colon, and also in human breast tumors, breast tumor cell lines and prostate cancer cell lines, after malignant transformation by oncogenes.35,36 Other FXYD proteins are also induced by oncogenic transformation. All three proteins, PLM, Mat8 and CHIF, induce ionic currents in Xenopus oocytes and PLM also forms ion channels in phospholipid bilayers.35,37,38 The identification of several FXYD family members, including PLM and CHIF, as regulators of Na+, K+-ATPase, points to a mechanism for regulation of the pump that involves the expression of an auxiliary subunit.39–42 Recently, we described the recombinant expression, purification and sample preparation in lipid micelles and bilayers for three members of the FXYD family: Mat8, PLM and CHIF.43

Figure 2.

Amino acid sequences of the FXYD membrane proteins. The FXYD homology (FH) domain encompasses the FXYD consensus sequence and the transmembrane (TM) domain is flanked by conserved positively charged residues. Conserved Gly residues in the TM domain are highlighted in gray.

EXPERIMENTAL

Protein expression and purification

Cloning, protein expression in E. coli and protein purification, have been described for both Bcl-2 and FXYD family proteins.29–31,43 For protein expression, transformed E. coli clones were grown on minimal M9 media [100 µg ml−1 ampicillin, 7.0 g l−1 Na2HPO4, 3.0 g l−1 KH2PO4, 0.5 g l−1 NaCl, 11 mg l−1 CaCl2, 120 mg l−1 MgSO4, 50 mg l−1 thiamine, 1% (v/v) LB, 10 g l−1 d-glucose, 1 g l−1(NH4)2SO4]. For uniformly 15N-labeled proteins, (15NH4)2SO4 (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA, USA) was supplied as the sole nitrogen source. The identity, purity and secondary structure folds of the proteins were characterized by N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis, MALDI/TOF mass spectrometry, CD spectroscopy and solution NMR spectroscopy.

The anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL was expressed in a pET vector, as a soluble protein lacking C-terminal residues 212–233, with a N-terminal (His)6 tag. After Ni affinity purification, Bcl-xL was further purified by anion-exchange chromatography [HiPrep 16/10 Q FF (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ USA); linear gradient of NaCl, in 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0], followed by size-exclusion chromatography [Sephacryl-100 (Amersham Biosciences) in 20 mm sodium phosphate, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm NaN3, pH 7].

The FXYD proteins PLM, CHIF and Mat8 were expressed in a pET vector as fusions with the His-Tag–TrpΔLE partner, which promotes the formation of inclusion bodies.44 After Ni affinity purification, the fusion protein was reacted with CNBr to release intact FXYD, and the resulting mixture was purified first by size-exclusion chromatography [Sephacryl-100 (Amersham Biosciences) in 10 mm sodium phosphate, 4 mm SDS, 23 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm NaN3, pH 7.5] and then by preparative reversed-phase HPLC [Delta-Pak C4 column, 15 µm, 300 Å, 300 × 7.8 mm i.d. (Waters, Milford, MA, USA); linear gradient of acetonitrile in 9 : 1 water–acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid].

Solid-state NMR samples

Samples of Bcl-xL in lipid bilayers were prepared by mixing 2 mg of 15N labeled Bcl-xL, dissolved in buffer (10% β-octylglucoside, 20 mm sodium phosphate, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm NaN3, pH 7.0), with 100 mg of lipid, DOPC (dioleoylphosphatidylcholine) and DOPG (dioleoylphosphatidylglycerol) in a molar ratio of 6 : 4, which had been sonicated to form unilamellar vesicles. After mixing, 5 ml of water were added, the mixture was quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen, allowed to thaw at room temperature and bath-sonicated for 30 s. Detergent was removed by dialyzing the preparation against two changes of 4 l of buffer, followed by two changes of 4 l of water, over 18 h. The reconstituted vesicles were concentrated by ultrafiltration and spread on the surface of 35 glass slides, excess water was evaporated at 42 °C and the slides were stacked.

Samples of CHIF and Mat8 in lipid bilayers were prepared by first dissolving 2 mg of 15N-labeled protein in 0.5 ml of TFE with 50 µl of β-mercaptoethanol and then adding 100 mg of lipid, DOPC–DOPG (8 : 2 molar ratio), in 1 ml of CHCl3. After spreading this solution on the surface of 35 glass slides, the solvents were removed under vacuum overnight and the slides were stacked. For both Bcl-xL and FXYDs, oriented lipid bilayers were formed by equilibrating the stacked slides (dimensions 11 × 20 × 0.06 mm) (Paul Marienfeld, Germany) for 24 h at 40 °C in a chamber containing a saturated solution of ammonium phosphate, which provides an atmosphere of 93% relative humidity. The samples were wrapped in Parafilm and then sealed in thin polyethylene film prior to insertion in the NMR probe. Hydrogen-exchanged samples were prepared by exposing the stacked oriented bilayer samples to an atmosphere saturated with 2H2O. This was achieved by placing the sample in a closed chamber containing 2H2O and incubating at 40 °C for 24 h.

NMR spectroscopy

Solid-state NMR spectra were obtained at 23 °C on a Bruker (Billerica, MA, USA) AVANCE 500 spectrometer with a wide-bore 500/89 Magnex (Yarnton, UK) magnet, and on a Chemagnetics-Otsuka Electronics (Fort Collins, CO, USA) CMX400 spectrometer, with a wide-bore 400/89 Oxford Instruments (Abingdon, UK) magnet. The laboratory-built double-resonance (1H/15N or 1H/31P) probes had square r.f. coils wrapped directly around the samples. The 15N spectra were obtained with single contact 1 ms CPMOIST45,46 and the 31P spectra with a single pulse. Both were acquired with continuous 1H irradiation (r.f. field strength 63 kHz), in order to decouple the 1H–15N and 1H–31P dipolar interactions. The 15N and 31P chemical shifts were referenced to 0 ppm for liquid ammonia and phosphoric acid. The NMR data were processed using the programs NMRPipe47 and FELIX (Accelerys, San Diego, CA, USA) on Linux/Dell (Round Rock, TX, USA) or Silicon Graphics (Mountain View, CA, USA) computer workstations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL

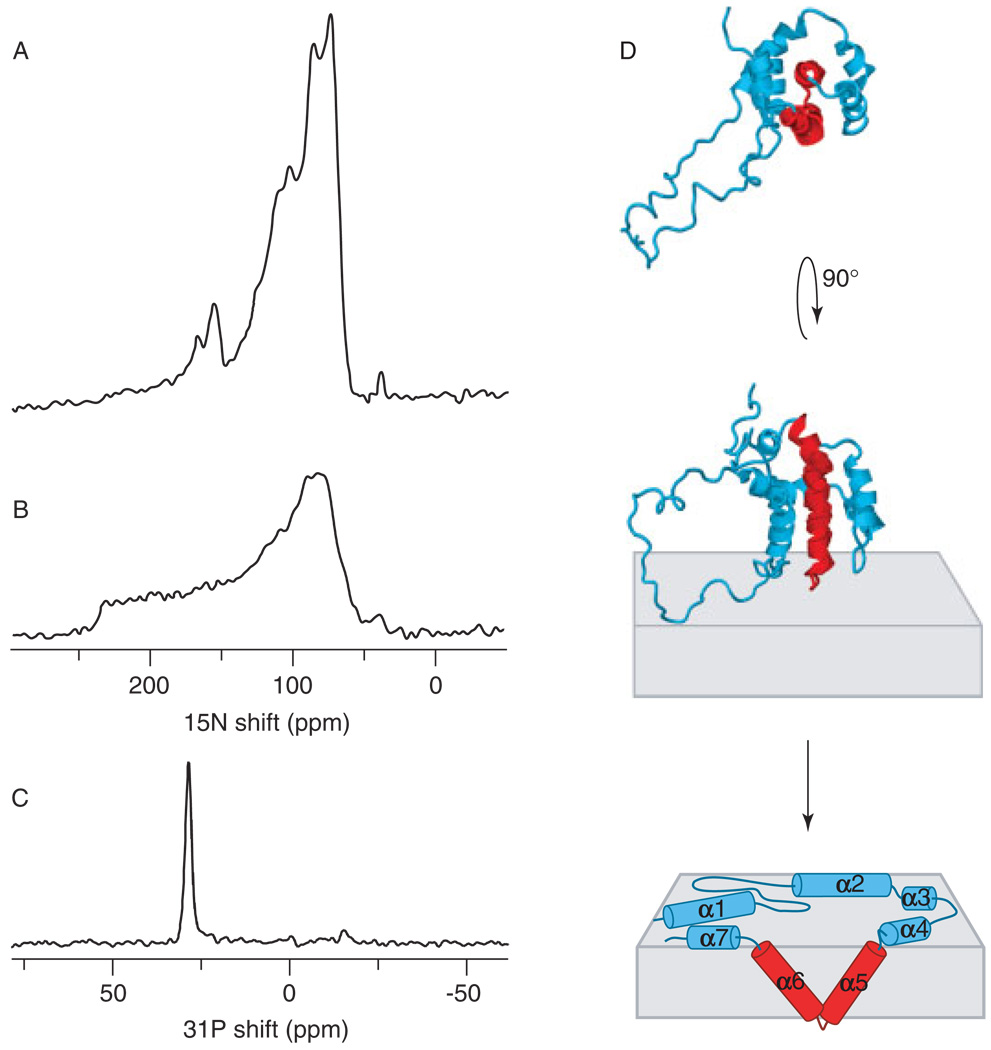

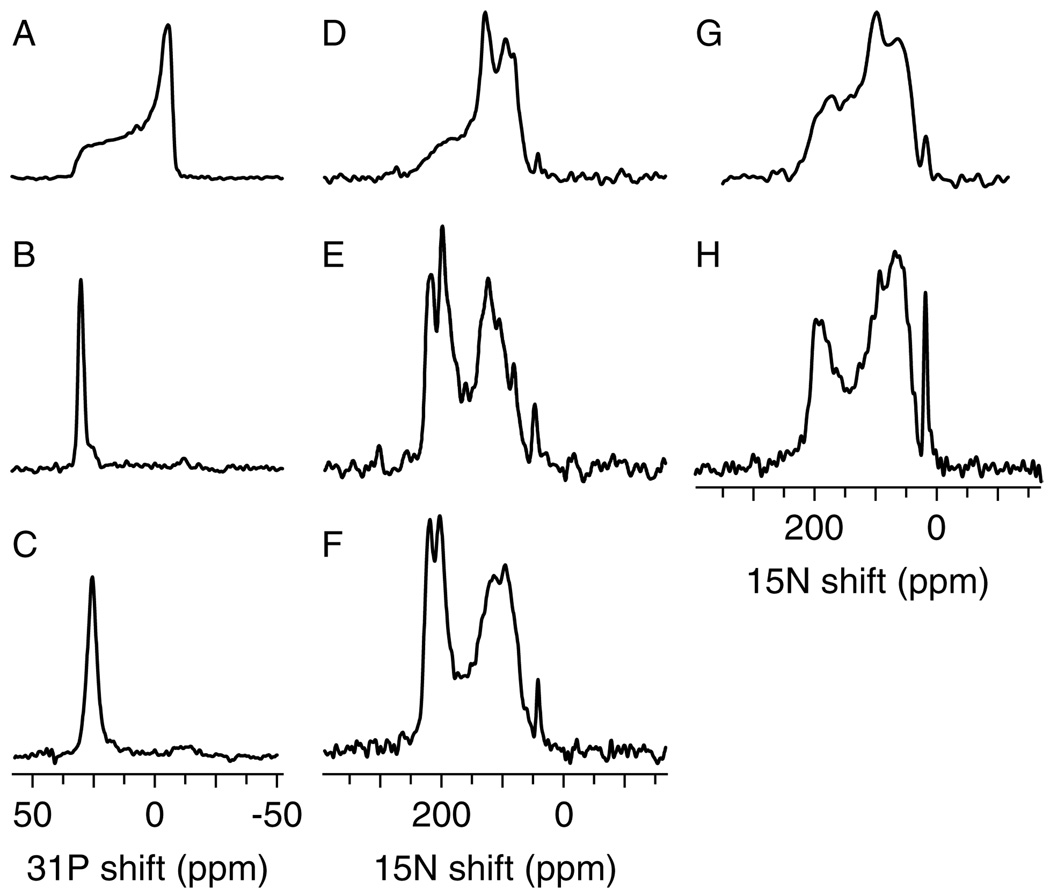

The spectra in Figure 3 were obtained from samples of Bcl-xL in oriented [Fig. 3(A) and (C)] and unoriented [Fig. 3(B)] lipid bilayers. The spectra from unoriented samples are excellent indicators of protein dynamics, because motional averaging has pronounced effects on powder patterns. The spectrum from the unoriented sample of Bcl-xL, which spans the full range (60–220 ppm) of the amide 15N chemical shift interaction, shows no evidence of motional averaging. The intensity near 35 ppm, also present in the spectrum from the oriented sample, is from the protein amino groups, which have a considerably narrower 15N chemical shift anisotropy. In contrast, the spectrum obtained from oriented Bcl-xL [Fig. 3(A)] is very different, as it is separated into discernable resonances with distinctly increased intensity near 170 and 80 ppm. The dominant spectral features reflect a structural model where resonances near 170 ppm are from the membrane-inserted helices and resonances near 80 ppm are from helices resting on the membrane surface. The phospholipid phase and the degree of phospholipid bilayer alignment can be assessed with 31P NMR spectroscopy of the lipid phosphate headgroup. The 31P NMR spectrum obtained for oriented lipids with Bcl-xL has a single resonance near 30 ppm, which is characteristic of intact and highly oriented membranes in a bilayer arrangement [Fig. 3(C)]. The presence of a single peak demonstrates that the samples are highly oriented, as required for NMR structure determination. Thus, taken together, the 15N and 31P spectra provide evidence that Bcl-xL, an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family protein, inserts in membranes, and does so without disruption of the membrane integrity.

Figure 3.

31P and 15N chemical shift solid-state NMR spectra of uniformly 15N-labeled Bcl-xL in oriented (A, C) and unoriented (B) lipid bilayers. The data support an umbrella model for membrane association of Bcl-2 family proteins (D), illustrated here for Bcl-xL (PDB file 1LXL).14

Like the pore-forming domain of bacterial colicin, Bcl-xL has two central hydrophobic helices, α5 and α6, that are long enough to span the membrane, and are required for both channel formation and cytoprotective activity.48 We find that this structural similarity between the soluble forms of the two proteins appears to extend to their membrane associated structures. For colicin, insertion of the hydrophobic helical hairpin into the membrane is supported by planar bilayer experiments,49 fluorescence energy transfer50 and solid-state NMR.51,52 Membrane association occurs when the colicin soluble helical bundle unfolds, exposing the hydrophobic helical hairpin which inserts in the membrane, while the rest of the protein forms a helical network on the membrane surface, adopting a so-called umbrella conformation.50,53 The solid-state NMR data in Fig. 3(A) suggest that Bcl-xL associates with membranes in a similar fashion, as illustrated in Fig. 3(D), with the α5–α6 helical hairpin inserting in the membrane.

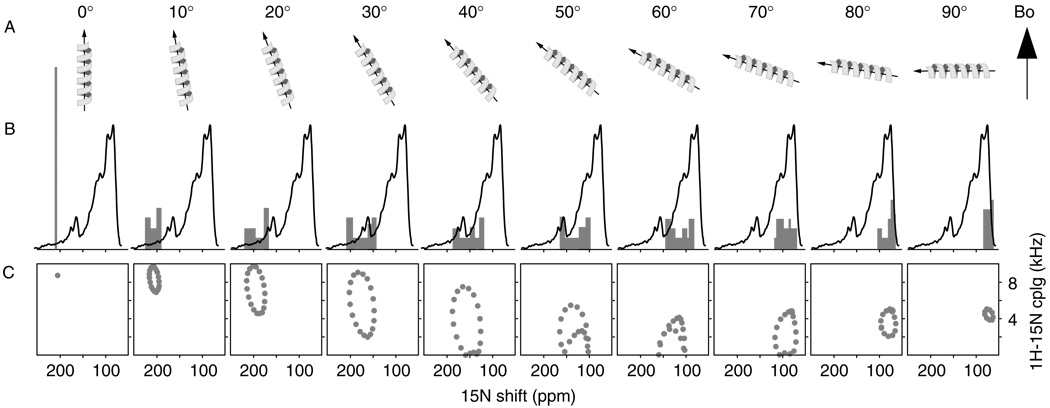

The two-dimensional 1H/15N PISEMA (Polarization Inversion with Spin Exchange at the Magic Angle)54 spectra of oriented proteins display characteristic patterns of resonances that reflect helical wheel projections of protein residues, and that are sensitive to the tilt and rotation of helices in membranes [Fig. 4(C)].4–6 These two-dimensional patterns serve as sensitive and visually accessible indices of membrane protein secondary structure and topology, but the positions of resonances in the corresponding one-dimensional projections can also provide good estimates of helix tilt [Fig. 4(B)]. Thus, in the spectrum from oriented Bcl-xL, the observation of 15N chemical shifts near 170 ppm suggests that the membrane-inserting helices cross the lipid bilayer with a substantial angle. We determined this angle to be around 40°, by comparing the Bcl-xL spectrum [Fig. 4(B), black] with the spectra calculated for helices at varying degrees of tilt [Fig. 4(B), gray]. For helices with this tilt, the 15N resonances are spread over a frequency range of about 60 ppm and, depending on helix rotation, they can be segregated into two major bands of equal intensity centered at 175 and 125 ppm. In the spectrum of oriented Bcl-xL, we determined the ratio of spectral intensities centered at 170 ppm (I170) and 80 ppm (I80) to be I170 : I80 = 15 : 85. This is consistent with a model for membrane association, where the α5 and α6 helices of Bcl-xL, which make up about 20% of the total protein, span the membrane with a tilt of 40°, adding to the spectral intensity at both 170 and 125 ppm, while the other helices rest on the membrane surface, adding to spectral intensity at 80 ppm. This is the umbrella model shown in Fig. 3(D).

Figure 4.

Experimental (black) and calculated (gray) solid-state NMR spectra for a 20-residue α-helix, with uniform dihedral angles (ϕ/ψ = −65/−40°), at different helix tilts relative to the magnetic field direction and the membrane normal (A). The calculated one-dimensional spectra (gray) are superimposed with the spectrum from uniformly 15N-labeled Bcl-xL in oriented lipid bilayers (black) (B). The two-dimensional 1H/15N PISEMA spectra trace out the characteristic resonance Pisa wheels from helices associated with membranes (C).

The solid-state NMR samples of Bcl-xL in oriented lipid bilayers were prepared with the same Bcl-xL constructs and methods for sample preparation that were used for the ion-channel activity studies, which provided the initial evidence for membrane insertion by Bcl-xL. Nevertheless, we note that resonances at chemical shifts for transmembrane amide nitrogens simply imply amide NH bonds aligned with the bilayer normal, and demonstrating that these are indeed transmembrane domains requires the resolution and assignment of resonances in two- and three-dimensional spectra, followed by structure determination.

FXYD proteins

The solid-state NMR spectra of 15N-labeled CHIF and Mat8 in lipid bilayers are shown in Fig. 5. The degree of phospholipid bilayer alignment can be assessed with 31P NMR spectroscopy of the lipid phosphate headgroup, as shown in Fig. 5(A) and (B). The 31P NMR spectra obtained for the CHIF samples are characteristic of intact liquid-crystalline bilayers, in both unoriented [Fig. 5(A)] and oriented [Fig. 5(B)] samples. Moreover, the spectrum from the oriented sample has a single peak near 30 ppm, as expected for highly aligned bilayers with this lipid composition (DOPC–DOPG, 8 : 2 molar ratio). These spectra demonstrate that the samples are highly oriented.

Figure 5.

31P and 15N chemical shift solid-state NMR spectra of uniformly 15N-labeled CHIF (A–F) and Mat8 (G, H) in lipid bilayers. Spectra were obtained from unoriented lipid bilayer samples (A, D, G), from oriented lipid bilayer samples (B, E, H) and from hydration-optimized lipid bilayers containing CHIF (C, F).

The one-dimensional 15N chemical shift spectra of CHIF [Fig. 5(D) and (E)] and Mat8 [Fig. 5(G) and (H)] provide a first view of the topology adopted by FXYD proteins in membranes. A preliminary analysis of the solid-state NMR data is possible since both CD and NMR spectroscopy in micelles show that the overall secondary structure of these proteins is α-helical.43 Many membrane proteins in lipid bilayers are largely immobile on the NMR time-scales, and their resonances are therefore not motionally averaged but have frequencies that reflect the orientation of their respective sites relative to the direction of the magnetic field. In our samples, the lipid bilayer plane is perpendicular to the magnetic field direction, and therefore each resonance frequency reflects the orientation of its corresponding protein site relative to the membrane.

In the spectra of CHIF and Mat8 in oriented bilayers [Fig. 5(E) and (H)], the resonance intensity near 200 ppm arises from backbone amide sites in the FXYD transmembrane helix that have their NH bonds nearly perpendicular to the plane of the membrane, while the intensity near 80 ppm is from sites in the N- and C-termini, with NH bonds nearly parallel to the membrane surface. The rather narrow dispersion of 15N resonances centered around 200 ppm suggests that the transmembrane helix crosses the lipid bilayer membrane with a very small tilt angle. The spectrum of CHIF, in particular, has significant resolution with identifiable peaks at frequencies throughout the range of the 15N amide chemical shift, and is strikingly different from that obtained from unoriented bilayers, which provides no resolution [Fig. 5(D)]. The peak near 35 ppm results from the amino groups of the lysine side-chains and the N-terminus.

For both CHIF and Mat8 in unoriented bilayers, most of the backbone sites are structured and immobile on the timescale of the 15N chemical shift interaction (10 kHz), and contribute to the characteristic amide powder patterns between about 220 and 60 ppm [Fig. 5(D) and (G)]. Some of the backbone sites, probably near the N- and C-termini, are mobile, and give rise to the resonance band centered near 120 ppm. Therefore, while certain resonances near 120 ppm in the spectrum of oriented CHIF may reflect specific orientations of their corresponding sites, some others arise from mobile backbone sites.

Recently, we described the preparation of oriented, hydration-optimized lipid bilayer samples, for NMR structure determination of membrane proteins.55 The samples consist of planar phospholipid bilayers, containing membrane proteins, that are oriented on single pairs of glass slides, and that have significantly reduced water content. The hydration-optimized samples overcome some of the difficulties associated with multi-dimensional, high-resolution, solid-state NMR spectroscopy of membrane proteins. They have greater stability over the course of multi-dimensional NMR experiments, they have lower sample conductance for greater r.f. power efficiency and allow greater r.f. coil filling factors to be obtained for improved experimental sensitivity. Sample preparation was illustrated for the FXYD membrane protein CHIF; in going from fully hydrated to hydration-optimized conditions, samples of CHIF in bilayers retained a high degree of alignment, as evidenced from the 31P NMR spectrum [Fig. 5(C)], and also retained the protein structural features, as reflected in the 15N spectrum [Fig. 5(F)].

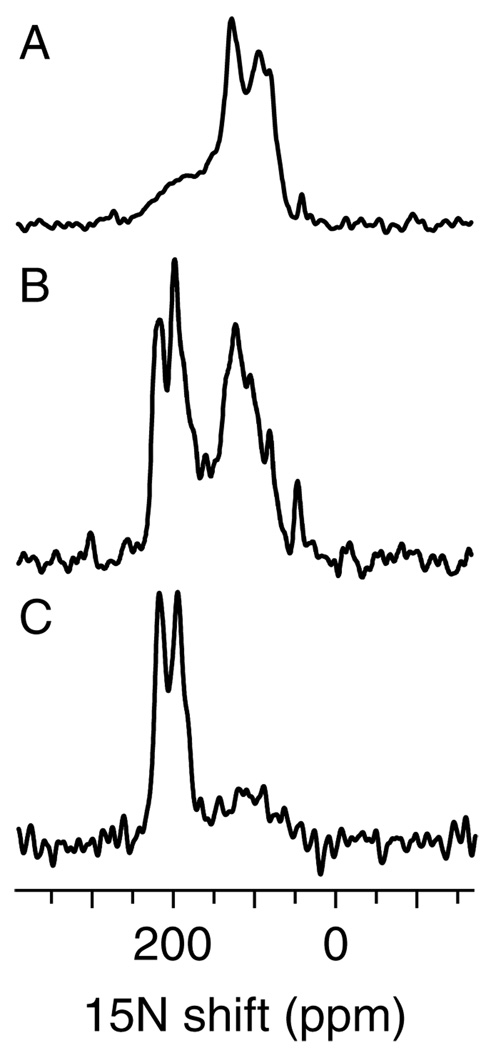

Hydrogen exchange experiments are useful for identifying hydrogen-bonded residues, and can also provide evidence of transmembrane helices. When the CHIF sample was exposed to deuterated water, the amide hydrogens in the transmembrane helix did not exchange whereas those in the rest of the protein underwent hydrogen exchange, and their resonances disappeared from the spectrum [Fig. 6(C)]. Thus, the spectra in Fig. 6 provide evidence for a tight hydrogen bonding network in the transmembrane helix of CHIF.

Figure 6.

15N chemical shift solid-state NMR spectra of uniformly 15N-labeled CHIF in unoriented (A) and oriented (B, C) lipid bilayers. Resonances near 200 ppm are from residues in the transmembrane helix that are resistant to hydrogen exchange, and are visible in the spectra obtained both after hydration with H2O (A, B) and after hydration with 2H2O (C).

CONCLUSIONS

The Bcl-2 family proteins act as powerful promoters or repressors of programmed cell death. These proteins cycle between soluble forms with globular structures determined primarily by NMR, and membrane-bound forms, that probably perturb mitochondrial physiology leading to the release of cytochrome c in mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis, and whose structures have not yet been determined. The 15N solid-state NMR spectra of the anti-apoptotic family member Bcl-xL in oriented lipid bilayers are consistent with a model for membrane association where the protein inserts its central hydrophobic helices in the membrane, while the remaining helices fold up to rest on the membrane surface. This is similar to the umbrella model proposed for membrane association of the structurally homologous channel-forming bacterial colicins. The 31P NMR spectra obtained from the oriented lipids in the sample demonstrate that membrane association of Bcl-xL maintains the lipid bilayer membranes intact, and highly oriented samples can be prepared for structural studies.

The FXYD membrane proteins regulate ion, osmolyte and fluid homeostasis in a variety of tissues, and are emerging as auxiliary tissue-specific and physiological state-specific subunits of the Na+,K+-ATPase. The cloning, expression and purification of the recombinant FXYD family members PLM, CHIF and Mat8 enable NMR structural studies to be performed in membrane environments, since the proteins can be isotopically labeled, and obtained in quantities that are suitable for NMR structure determination. The 15N-solid-state NMR spectra from oriented lipid bilayer samples provide a first view of the topological features of their transmembrane and terminal domains. The ability to produce milligram quantities of pure FXYD proteins lays the foundation for functional studies that, together with structure determination, can provide important structure–activity correlations. For example, the reconstitution of Na+,K+-ATPase activity in the presence of FXYD proteins would be an important step in understanding the mechanism of pump regulation, while the incorporation of FXYD proteins in lipid bilayers would enable ion channel activities to be characterized by measuring specific ionic currents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (R01CA82864 to F.M.M. and R01GM60554 to J.C.R.), the Department of the Army Breast Cancer Research Program (DAMD17-00-1-0506 and DAMD17-02-1-0313 to F.M.M.), and the California Breast Cancer Research Program (8WB0110 to F.M.M.). It utilized the Burnham Institute NMR Facility supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (P30CA30199), and the Biomedical Technology Resources for Solid-state NMR of Proteins at the University of California San Diego, supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (P41EB002031).

REFERENCES

- 1.Marassi FM. Concepts Magn. Reson. 2002;14:212. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opella SJ, Ma C, Marassi FM. Methods Enzymol. 2001;339:285. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)39319-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marassi FM, Ramamoorthy A, Opella SJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:8551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marassi FM. Biophys. J. 2001;80:994. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marassi FM, Opella SJ. J. Magn. Reson. 2000;144:150. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, Denny J, Tian C, Kim S, Mo Y, Kovacs F, Song Z, Nishimura K, Gan Z, Fu R, Quine JR, Cross TA. J. Magn. Reson. 2000;144:162. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marassi FM, Opella SJ. J. Biomol. NMR. 2002;23:239. doi: 10.1023/a:1019887612018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marassi FM, Opella SJ. Protein Sci. 2003;12:403. doi: 10.1110/ps.0211503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed JC. Nature (London) 1997;387:773. doi: 10.1038/42867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1899. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vander Heiden MG, Thompson CB. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:E209. doi: 10.1038/70237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams JM, Cory S. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:61. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fesik SW. Cell. 2000;103:273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muchmore SW, Sattler M, Liang H, Meadows RP, Harlan JE, Yoon HS, Nettesheim D, Chang BS, Thompson CB, Wong SL, Ng SL, Fesik SW. Nature (London) 1996;381:335. doi: 10.1038/381335a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aritomi M, Kunishima N, Inohara N, Ishibashi Y, Ohta S, Morikawa K. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:27 886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petros AM, Medek A, Nettesheim DG, Kim DH, Yoon HS, Swift K, Matayoshi ED, Oltersdorf T, Fesik SW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:3012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041619798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sattler M, Liang H, Nettesheim D, Meadows RP, Harlan JE, Eberstadt M, Yoon HS, Shuker SB, Chang BS, Minn AJ, Thompson CB, Fesik SW. Science. 1997;275:983. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chou JJ, Li H, Salvesen GS, Yuan J, Wagner G. Cell. 1999;96:615. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonnell JM, Fushman D, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ, Cowburn D. Cell. 1999;96:625. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80573-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki M, Youle RJ, Tjandra N. Cell. 2000;103:645. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Q, Petros AM, Virgin HW, Fesik SW, Olejniczak ET. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062525799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denisov AY, Madiraju MS, Chen G, Khadir A, Beauparlant P, Attardo G, Shore GC, Gehring K. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:21 124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301798200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinds MG, Lackmann M, Skea GL, Harrison PJ, Huang DC, Day CL. EMBO J. 2003;22:1497. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schendel SL, Reed JC. Methods Enzymol. 2000;322:274. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)22028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minn AJ, Velez P, Schendel SL, Liang H, Muchmore SW, Fesik SW, Fill M, Thompson CB. Nature (London) 1997;385:353. doi: 10.1038/385353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antonsson B, Montessuit S, Lauper S, Eskes R, Martinou JC. Biochem. J. 2000;345((Pt 2)):271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlesinger PH, Gross A, Yin XM, Yamamoto K, Saito M, Waksman G, Korsmeyer SJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:11 357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Losonczi JA, Olejniczak ET, Betz SF, Harlan JE, Mack J, Fesik SW. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11 024. doi: 10.1021/bi000919v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zha H, Aime-Sempe C, Sato T, Reed JC. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:7440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zha H, Fisk HA, Yaffe MP, Mahajan N, Herman B, Reed JC. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:6494. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schendel SL, Xie Z, Montal MO, Matsuyama S, Montal M, Reed JC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:5113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sweadner KJ, Rael E. Genomics. 2000;68:41. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmer CJ, Scott BT, Jones LR. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:11 126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Attali B, Guillemare E, Lesage F, Honore E, Romey G, Lazdunski M, Barhanin J. Nature (London) 1993;365:850. doi: 10.1038/365850a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrison BW, Moorman JR, Kowdley GC, Kobayashi YM, Jones LR, Leder P. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:2176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaarala MH, Porvari K, Kyllonen A, Vihko P. Lab. Invest. 2000;80:1259. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moorman JR, Palmer CJ, John JE, 3rd, Durieux ME, Jones LR. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:14 551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Attali B, Latter H, Rachamim N, Garty H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:6092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arystarkhova E, Donnet C, Asinovski NK, Sweadner KJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:10 162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beguin P, Crambert G, Guennoun S, Garty H, Horisberger JD, Geering K. EMBO J. 2001;20:3993. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beguin P, Crambert G, Monnet-Tschudi F, Uldry M, Horisberger JD, Garty H, Geering K. EMBO J. 2002;21:3264. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crambert G, Fuzesi M, Garty H, Karlish S, Geering K. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11 476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182267299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crowell KJ, Franzin CM, Koltay A, Lee S, Lucchese AM, Snyder BC, Marassi FM. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1645:15. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(02)00473-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staley JP, Kim PS. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1822. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pines A, Gibby MG, Waugh JS. J. Chem. Phys. 1973;59:569. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levitt MH, Suter D, Ernst RR. J. Chem. Phys. 1986;84:4243. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsuyama S, Schendel SL, Xie Z, Reed JC. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:30 995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.30995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kienker PK, Qiu X, Slatin SL, Finkelstein A, Jakes KS. J. Membr. Biol. 1997;157:27. doi: 10.1007/s002329900213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindeberg M, Zakharov SD, Cramer WA. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;295:679. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim Y, Valentine K, Opella SJ, Schendel SL, Cramer WA. Protein Sci. 1998;7:342. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumashiro K, Schmidt-Rohr K, Murphy OJ, Ouellette KL, Cramer WA, Thompson LK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:5043. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elkins P, Bunker A, Cramer WA, Stauffacher CV. Structure. 1997;5:443. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu CH, Ramamoorthy A, Opella SJ. J.Magn. Reson. A. 1994;109:270. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marassi FM, Crowell KJ. J. Magn. Reson. 2003;161:64. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00182-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]