Abstract

Imaging systems that exploit arrays of photodetectors in curvilinear layouts are attractive due to their ability to match the strongly nonplanar image surfaces (i.e., Petzval surfaces) that form with simple lenses, thereby creating new design options. Recent work has yielded significant progress in the realization of such “eyeball” cameras, including examples of fully functional silicon devices capable of collecting realistic images. Although these systems provide advantages compared to those with conventional, planar designs, their fixed detector curvature renders them incompatible with changes in the Petzval surface that accompany variable zoom achieved with simple lenses. This paper describes a class of digital imaging device that overcomes this limitation, through the use of photodetector arrays on thin elastomeric membranes, capable of reversible deformation into hemispherical shapes with radii of curvature that can be adjusted dynamically, via hydraulics. Combining this type of detector with a similarly tunable, fluidic plano-convex lens yields a hemispherical camera with variable zoom and excellent imaging characteristics. Systematic experimental and theoretical studies of the mechanics and optics reveal all underlying principles of operation. This type of technology could be useful for night-vision surveillance, endoscopic imaging, and other areas that require compact cameras with simple zoom optics and wide-angle fields of view.

Keywords: biomimetic, electronic eyeball camera, flexible electronics, fluidic tunable lens, hydraulic actuation

Mammalian eyes provide the biological inspiration for hemispherical cameras, where Petzval-matched curvature in the photodetector array can dramatically simplify lens design without degrading the field of view, focal area, illumination uniformity, or image quality (1). Such systems use photodetectors in curvilinear layouts due to their ability to match the strongly nonplanar image surfaces (i.e., Petzval surfaces) that form with simple lenses (2–4). Historical interest in such systems has culminated recently with the development of realistic schemes for their fabrication, via strategies that overcome intrinsic limitations associated with the planar operation of existing semiconductor processes (4–6). The most promising procedures involve either direct printing of devices and components onto curved surfaces (6) or geometrical transformation of initially planar systems into desired shapes (1, 7–9). All demonstrated designs involve rigid, concave device substrates, to achieve improved performance compared to planar cameras when simple lenses with fixed magnification are used. Interestingly, biology and evolution do not provide guides for achieving the sort of large-range, adjustable zoom capabilities that are widely available in man-made cameras. The most relevant examples are in avian vision, where shallow pits in the retina lead to images with two fixed levels of zoom (50% high magnification in the center of the center of the field of view) (10). Also, changes in imaging properties occur, but in an irreversible fashion, during metamorphosis in amphibian vision to accommodate transitions from aquatic to terrestrial environments (11).

The challenge in hemispherical imagers is that, with simple optics, the curvature of the Petzval surface changes with magnification in a manner that leads to mismatches with the shape of detector array. This behavior strongly degrades the imaging performance, thereby eliminating any advantages associated with the hemispherical detector design. The solution to this problem demands that the curvature of the detector array changes in a coordinated manner with the magnification, to ensure identical shapes for the image and detector surfaces at all zoom settings. In the following, we report a system that accomplishes this outcome by use of an array of interconnected silicon photodetectors on a thin, elastomeric membrane, in configurations that build on advanced concepts of stretchable electronics (12–14). Actuating a fluidic chamber beneath the membrane causes it to expand or contract in a linear elastic, reversible fashion that provides precise control of the radius of curvature. Integrating a similarly actuated fluidic plano-convex lens yields a complete, hemispherical camera system with continuously adjustable zoom.

Results and Discussion

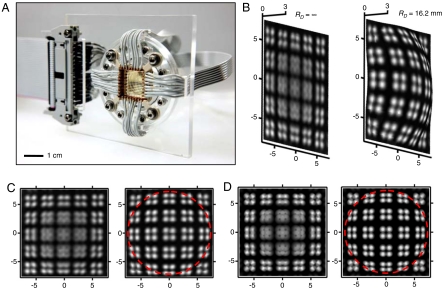

Fig. 1A provides a schematic illustration of the elements of the device and Fig. 1B shows a picture of an integrated system. The upper and lower components correspond to an adjustable, plano-convex zoom lens and a tunable, hemispherical detector array, respectively. The lens uses adapted versions of similar components described elsewhere (15–18); it consists of a water-filled cavity (1-mm thick, in the planar, unpressurized state) between a thin (0.2 mm) membrane of the transparent elastomer poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) on top and a glass window (1.5-mm thick) underneath. Pumping water into this cavity deforms the elastomer into a hemispherical shape, with a radius of curvature that depends on the pressure. This curvature, together with the index of refraction of the PDMS and water, defines the focal length of the lens and, therefore, the magnification that it can provide. Fig. 1C shows images of the detector array viewed through the fluidic lens, at two different positive pressures. The changes in magnification evident in Fig. 1C are reversible and can be quantified through measurement and mechanics modeling. Fig. 1D presents side view images and data collected at various states of deformation. The lens adopts an approximately hemispherical shape for all tuning states, with an apex height and radius of curvature (RL) that change with pressure in a manner quantitatively consistent with theory (blue curves) and finite element analysis (green circles), as shown in the graph of Fig. 1D. (Details on the lens profile appear in the SI Appendix.)

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of the camera, including the tunable lens (Upper) and tunable detector (Lower) modules. The lens consists of a fluid-filled gap between a thin (0.2 mm) PDMS membrane and a glass window (1.5-mm thick), to form a plano-convex lens with 9-mm diameter and radius of curvature that is adjustable with fluid pressure. The tunable detector consists of an array of interconnected silicon photodiodes and blocking diodes (16 × 16 pixels) mounted in a thin (0.4 mm) PDMS membrane, in a mechanically optimized, open mesh serpentine design. This detector sheet mounts on a fluid-filled cavity; controlling the pressure deforms the sheet into concave or convex hemispherical shapes with well-defined, tunable levels of curvature. (B) Photograph of a complete camera. (C) Photographs of the photodetector array imaged through the lens, tuned to different magnifications. The left and right images were acquired at radius of curvature in the lens of 5.2 and 7.3 mm. In both cases, the radius of curvature of the detector surface was 11.4 mm. The distance of the center part of the detector from the bottom part of the lens was 25.0 mm. (D) Angled view optical images of the tunable lens at three different configurations (Upper), achieved by increasing the fluid pressure from left to right. The lower frame shows measurements of the height and radius of curvature of the lens surface as a function of applied fluid pressure. The results reveal changes that are repeatable and systematic (experimental; □ and ▪ symbols) and quantitatively consistent with analytical calculations of the mechanics (analytical; blue lines) and finite element analysis (FEA, green symbols).

The most important, and most challenging, component of the camera is the tunable detector array. As is well known, the image formed by a plano-convex lens lies on a Petzval surface that takes the form of an elliptic paraboloid of revolution (1, 7), well approximated by a hemisphere in many cases of practical interest. The curvature depends strongly on magnification. As a result, the shape of the detector surface must change to accommodate different settings in the lens configuration. Fig. 1 A and B and Fig. 2 provide illustrations, images, and other details of a system that affords the required tunability, via stretchable designs actuated by hydraulics. The detector consists of an array of unit cells, each of which includes a thin (1.25 μm) silicon photodiode and blocking diode; the latter facilitates passive matrix readout. Narrow metal lines [Cr (5 nm)/Au (150 nm)] encapsulated with thin films of polyimide (∼1 μm) on top and bottom provide ribbon-type interconnects between these cells, in a neutral mechanical plane layout that isolates the metal from bending induced strains. The interconnects have serpentine shapes to form an overall system with an open mesh geometry. These collective features enable the array to accommodate large strains associated with deformation of a thin (0.4 mm) supporting membrane of PDMS (13, 14). The fabrication involves planar processing of the devices and interconnects on a rigid substrate; release and transfer to the PDMS represents the final step. The area coverages of the device islands and the photosensitive regions are ∼30% and ∼13%, respectively. Previously reported mechanical designs can be used to achieve coverages up to ∼60%.(9) Typical yields of working pixels were ∼95%. An additional ∼1–2% of the pixels fail after extensive mechanical cycling. For the images presented in the following, we used overscanning procedures to eliminate effects of defective pixels. (Details on device fabrication, transfer processes, hydraulic tuning systems, device yields, and overscanning procedures appear in Materials and Methods and the SI Appendix.)

Fig. 2.

(A) Tilted view of a photodetector array on a thin membrane of PDMS in flat (Upper) and hemispherically curved (Lower) configurations, actuated by pressure applied to a fluid-filled chamber underneath. (B) Three-dimensional rendering of the profile of the deformed surface measured by a laser scanner. Here, the shape is close to that of a hemisphere with a radius of curvature (RD) of 13.3 mm and a maximum deflection (HD) of 2.7 mm. Calculated (blue) and measured (red) unit cell positions appear as squares on this rendered surface. (Upper) Three-dimensional rendering of circumferential strains in the silicon devices (squares) and the PDMS membrane determined by finite element analysis (Lower). (C) Angled view optical images of the tunable detector in three different configurations (Top), achieved by decreasing the level of negative pressure applied to the underlying fluid chamber from left to right. Measurements of the apex height and radius of curvature of the detector surface as a function of applied fluid pressure reveal changes that are repeatable and systematic (experimental) and quantitatively consistent with analytical calculations of the mechanics (analytical; blue lines) and finite element analysis (FEA, green symbols), as shown in the middle frame. Laser scanning measurements of the profiles of the deformed detector surface show shapes are almost perfectly hemispherical, consistent with analytical mechanics models. Here, each measured profile (symbols) is accompanied by a corresponding analytical calculated result (lines) (Bottom). (D) Optical micrograph of a 2 × 2 array of unit cells, collected from a region near the center of a detector array, in a deformed state (Left) and maximum principal strains in the silicon and metal determined by finite element analysis (Right) for the case of overall biaxial strain of 12%. These strains are far below those expected to cause fracture in the materials.

Mounting the membrane with the photodector array bonded to its surface onto a plate with a circular opening (circular, with diameter D) above a cylindrical chamber (Fig. 1 A and B), filling this chamber with distilled water, and connecting input and output ports to an external pump prepares the system for pneumatic tuning. Fig. 2A shows tilted views of a representative device in its initial, flat configuration (i.e., no applied pressure; upper frame) and in a concave shape induced by extracting liquid out of the chamber (i.e., negative applied pressure; lower frame). (See Movie S1 for real-time operation of its deformation.) The exact shapes of the deformed surfaces, and the positions of the photodetectors in the array are both critically important to operation. A laser scanner tool (Next Engine) provided accurate measurements of the shapes at several states of deformation (i.e., applied pressures). For all investigated pressures, the detector surfaces exhibit concave curvature well characterized by hemispherical shapes. Fig. 2B shows a rendering of the laser-scanned surface. Measured profiles yield the peak deflection (H, at the center of the membrane) and the radius of curvature (RD, also near the center). Top down images define the two-dimensional positions (i.e., along polar r and θ axes of Fig. 2B) of the photodetectors, at each deformed state. Projections onto corresponding measurements of the surface shape yield the heights (i.e., along the z axis). The outcomes appear as red squares in Fig. 2B. Comparison to analytical mechanics modeling of the positions (blue squares) shows excellent agreement. The photodetector surface deforms to a hemispherical shape due to water extraction, which implies a uniform meridional strain in the deformed surface, and therefore a uniform spacing between photodetectors in this direction (19). Mechanics analysis yields predictions for H as a function of the applied pneumatic pressure caused by water extraction and also a simple expression for the radius of curvature: RD = (D2 + 4H2)/(8H). Both results appear as blue curves in the middle frame of Fig. 2C; they show excellent agreement with experiment (black squares) and finite element analysis (green circles). A photodetector with an initial position given by (r,θ,0) in cylindrical coordinates on the flat surface moves to a new position given by (RD sin ϕ,θ,RD - H - RD cos ϕ) on the deformed surface, where φ = (2r/D) sin-1[4DH/(D2 + 4H2)] is the polar angle (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). (See SI Appendix for details on the modeling.) The analytically obtained photodetector positions are indicated as blue squares in the upper frame of Fig. 2B, which shows excellent agreement with both experiment and finite element analysis (lower frame of Fig. 2B), and therefore validates the hemispherical shape of the deformed detector surface. Similar modeling can be used to define the distribution of strains across both the PDMS membrane and the array of silicon photodiodes and blocking diodes. The results (Fig. 2B) show strains in both materials that are far below their thresholds for fracture (> 150% for PDMS; ∼1% for silicon). The overall computed shape of the system also compares well to measurement. Further study illustrates that this level of agreement persists across all tuning states, as illustrated in Fig. 2C. Finite element analysis (lower frame of Fig. 2B) shows that the serpentine interconnects have negligible effects on the photodetector positions (20). Understanding their behavior is nevertheless important because they provide electrical interconnection necessary for operation. Three-dimensional finite element analysis of a square 2 × 2 cluster of four unit cells appears in Fig. 2D. The color shading shows the maximum principal strains in the silicon and metal, which are the most fragile materials in the detectors. The calculated peak strains in the materials are all exceptionally low, even for this case where the overall biaxial strain is ∼12%, corresponding to the point of highest strain in the array when tuned to the most highly curved configuration.

Fig. 3A presents a picture of a completed detector with external interconnection wiring to a ribbon cable that interfaces with an external data acquisition system (1). Here, a top-mounted fixture with a circular opening supports 32 electrode pins that mechanically press against corresponding pads at the periphery of the detector array. A compression element with four cantilever springs at each corner ensures uniformity in the applied pressure, to yield a simple and robust interconnection scheme (no failures for more than 100 tuning cycles). These features and the high yields on the photodetector arrays enable cameras that can collect realistic images, implemented here with resolution enhancements afforded by scanning procedures to allow detailed comparison to theory (see SI Appendix). To explore the basic operation, we first examine behavior with a fixed imaging lens. Representative images collected with the detector in planar and hemispherical configurations appear in Fig. 3B. The object in this case consists of a pattern of discs (diameters, 2 mm; distances between near neighbors, 3 mm; distances between distant neighbors, 5 mm), placed 75 mm in front of a glass plano-convex lens (diameter, 9 mm; focal length, 22.8 mm). The image in the flat state corresponds to a distance of 26.2 mm from the lens, or 5.5 mm closer to the lens than the nominal position of the image computed with thin lens equations. At this location, the regions of the image in the far periphery of the field of view (i.e., the four corners) are in focus. The center of the field of view is not simultaneously in focus because of the Petzval surface curvature associated with the image. Deforming the detector array into a concave shape moves the center region away from the lens and toward the position of the image predicted by the thin lens equation. The hemispherical shape simultaneously aligns other parts of the detector with corresponding parts of the image. As a result, the entire field of view comes into focus at once. Planar projections of these images are shown in Fig. 3C. Simulated images based on experimental parameters appear in Fig. 3D. The results used ray-tracing calculations and exploited the cylindrical symmetry of the device (21, 22). In particular, fans of rays originating at the object (75 mm in front of the lens) were propagated through the system to determine relevant point spread functions (PSFs). Placing corresponding PSFs for every point at the object plane, using a total of 10,000 rays, onto the surface of a screen defined by the shape of the detector yielded images suitable for direct comparison to experiment.

Fig. 3.

(A) Photograph of a deformable detector array with external electrical interconnections. Electrode pins on a mounting plate press against matching electrodes at the periphery of the array to establish connections to a ribbon cable that leads to a data acquisition system. (B) Images of a test pattern of bright circular discs, acquired by the device in flat (Left) and deformed hemispherical (Right) configurations, collected using a glass plano-convex lens (diameter, 9 mm; focal length, 22.8 mm). The images are rendered on surfaces that match those of the detector array. The distance between the lens and the source image is 75 mm. The radius of curvature and the maximum deflection in this deformed state are 16.2 and 2.2 mm, respectively. The image in the flat case was collected at a distance of 5.5 mm closer to the lens than the focal location expected by the thin lens approximation (31.7 mm). In this position, only the far peripheral regions of the image are in focus. The image in the curved configuration was acquired simply by actuating the detector into this shape, without changing any other aspect of the setup. This deformation brings the entire field of view into focus, due to matching of the detector shape to the Petzval surface. (C) Planar projections of these images. The dashed circle indicates the area under deformation. (D) Modeling results corresponding to these two cases, obtained by ray-tracing calculation. The outcomes show quantitative agreement with the measurements. The dashed circle indicates the area under deformation.

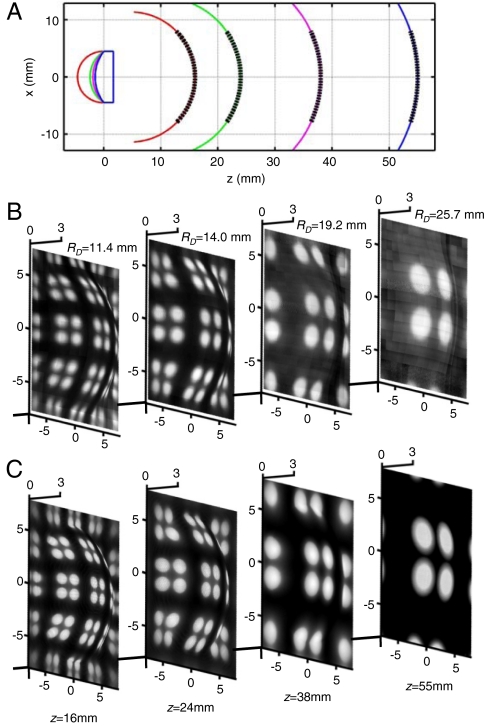

To demonstrate full capabilities and adjustable zoom, we acquired images with the tunable, fluidic lens. Ray-tracing analysis for the case of an object at 67 mm from the lens provided matched parameters of RL, RD, and z, the distance to the center of the image surface, as example configurations for different magnification settings. Fig. 4A shows two-dimensional representations of Petzval surfaces for four different lens shapes, all plano-convex with hemispherical curvature, corresponding to (RL, RD, z) values of (4.9, 11.4, 16 mm), (6.1, 14.0, 24 mm), (7.3, 19.2, 38 mm), and (11.5, 25.7, 55 mm). As expected, increasing RL increases the focal length and the magnification, thereby increasing z and RD. Current setups involve manual adjustment of the distance between the detector and the lens. Images collected at these four settings appear in Fig. 4B. The object in this case is an array of circular discs, similar to those used in Fig. 3, but with diameters of 3.5 mm, pitch values of 5 and 8.5 mm. The optical magnifications are 0.24, 0.36, 0.57, and 0.83, corresponding to a 3.5× adjustable zoom capability. Uniformity in focus obtains for all configurations. (Further comparison with flat detector appears in the SI Appendix.) Optical modeling, using the same techniques for the results of Fig. 3, show quantitative agreement.

Fig. 4.

(A) Ray-tracing analysis of the positions and curvatures of the image surfaces (i.e., Petzval surfaces; Right) that form with four different geometries of a tunable plano-convex lens (Left). Actual sizes of detector surfaces are shown as dashed lines. (B) Images acquired by a complete camera system, at these four conditions. These images were collected at distances from the lens (z) of 16, 24, 38, and 55 mm with corresponding radii of curvature of the lens surface (RL) of 4.9, 6.1, 7.3, and 11.5 mm. The radii of curvature (RD) of the detector surface, set to match the computed Petzval surface shape, were 11.4, 14.0, 19.2, and 25.7 mm. These images were acquired by a scanning procedure described in Materials and Methods The object consists of a pattern of light circular discs (diameter, 3.5 mm; pitches between circles, 5 and 8.5 mm). (C) Images computed by ray-tracing analysis, at conditions corresponding to the measured results. The axis scales are in millimeters.

Conclusions

The results demonstrate that camera systems with tunable hemispherical detector arrays can provide adjustable zoom with wide-angle field of view, low aberrations, using only a simple, single-component, tunable plano-convex lens. The key to this outcome is an ability to match the detector geometry to a variable Petzval surface. This type of design could complement traditional approaches, particularly for applications where compound lens systems necessary for planar or fixed detectors add unwanted size, weight, or cost to the overall system; night-vision cameras and endoscopes represent examples. Although the fill factor and total pixel count in the reported designs are moderate, there is nothing fundamental about the process that prevents significant improvements. The hydraulic control strategy represents one of several possible actuation mechanisms. Although the present design incorporates two separate pumps and manual z-axis positioning, with suitable setups it should be possible for a single actuator to adjust both lens and detector, and their separation, simultaneously, in a coordinated fashion. These kinds of concepts, or other approaches in which microactuators are embedded directly on the elastomer, as a class of hybrid hard and soft microelectromechanical system device, might be useful to explore.

Materials and Methods

Fabrication of Silicon Photodetector Arrays on Elastomeric Membranes.

The detector arrays were made by doping a sheet of silicon in a configuration designed for pairs of photodiodes and blocking diodes in a 16 × 16 square matrix. In particular, the top layer of an silicon on insulator wafer (1.25-μm-thick silicon on a 400-nm-thick layer of silicon dioxide on a silicon substrate, p type, 〈100〉 direction, Soitec) was p and n doped sequentially through a masking layer of silicon dioxide (900-nm thick) deposited by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (SLR730, Unaxis/Plasma-Therm) and patterned by photolithography and etching. For p doping, the sample was exposed to a boron source for 30 min at 1,000 °C in an N2 environment (custom 6-in. tube furnace). The n doping used a phosphorous source under the same conditions for 10 min (Model 8500 Dual-Stack Diffusion/Oxidation Furnaces, Lindberg/Tempress). Each unit cell was then isolated by reactive ion etching (RIE; Unaxis/Plasma-Therm) through the silicon layer in a patterned defined by photolithography. Interconnects consisted of metal lines [Cr (5 nm)/Au (150 nm)] deposited by sputtering (AJA International, Inc.) and encapsulated with polyimide (∼1 μm, from polyamic acid solution, Sigma Aldrich) on top and bottom. Just prior to transfer, the buried silicon dioxide was removed by wet etching (30 min, hydrofluoric acid 49%) through an array of holes (3 μm in diameter) etched through the silicon.

A stamp of PDMS (SYLGARD 184 Silicone elastomer kit, Dow Corning) was used to transfer the resulting photodetector array to a thin (0.4 mm) membrane of PDMS that was preexposed to ultraviolet-induced ozone for 2.5 min. Before peeling back the stamp, the entire assembly was baked at 70 °C for 10 min to increase the strength of bonding between the array and the membrane.

Completing the Tunable Detector System.

The membrane supporting the detector array was cut into a circular shape (49 mm in diameter), and then placed on a machined plate with a hole (13 or 15 mm in diameter) at the center. A cylindrical chamber, with volume of 3.5 mL, was then attached to the bottom of this plate. The membrane was mechanically squeezed at the edges to form a seal and, at the same time, to yield slight radial tensioning, through the action of structures on the plate designed for this purpose. The bottom chamber has two inlets, one of which connects to a stop cock (Luer-lock polycarbonate stop cocks, McMaster-Carr) and the other to a custom syringe pump capable of controlling the volume of liquid moving in and out of the camber with a precision of ∼0.05 mL. Distilled water fills the system. A gauge (diaphragm gauge 0 ∼ 3 psi, Noshok) was used to monitor the pressure.

For electrical connection, the top insulating layers covering the electrode pads at the periphery of the detector array were removed by RIE (CS 1701 Reactive Ion Etching System, Nordson MARCH) through an elastomeric shadow mask. These electrodes press against copper electrode pins on a mounting plate designed with four cantilever springs at its corners. To ensure good electrical contact, the surfaces of the pins were polished and then coated with metal layers by electron beam deposition [Cr (20 nm)/Au (400 nm)]. Each electrode pin was connected to an electrical wire using conductive epoxy (CW2400, Chemtronics); these wires were assembled with a pin connector which connects to a ribbon cable.

Fabricating the Tunable Lens.

The tunable lens simply consists of a thin PDMS membrane (0.2 mm in thickness, 25.4 mm in diameter) and a glass window (12.5 mm in diameter, 1.5 mm in thickness; Edmund Optics) attached to a plastic supporting piece by epoxy (ITW Devcon). The separation between the PDMS membrane and the glass window was ∼1 mm. To ensure a watertight seal, the membrane was squeezed between two plastic plates. A hole in the top plate defined the diameter of the lens (9 mm). Gauges (diaphragm gauge 0 ∼ 10 psi, Noshok; differential gauge 0 ∼ 20 psi, Orange Research) were used to measure the pressure.

Capturing Images.

Diffusive light from an array of light emitting diodes (MB-BL4X4, Metaphase Technologies) provided a source for illumination. The objects consisted of printed transparency films (laser photoplotting, CAD/Art Services) or metal plates machined by laser cutting. In all cases, images were rendered by combining datasets collected by stepping the detector along two orthogonal axes x, y normal to the optic axis. Either 10 or 20 steps with spacings of 92 μm for each axis were used to achieve effective resolutions of 100 times larger than the number of photodetectors. Lookup tables and automated computer codes were used, in some cases, to eliminate the effects of malfunctioning pixels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank T. Banks, and J.A.N.T. Soares for help using facilities at the Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory. The authors also appreciate M.J. Kim, D. Stevenson, G. Shin, K.J. Yu, J.H. Lee, D.H. Kim, D.G. Kim, H.C. Ko, and J.S. Ha for valuable comments and help. The fundamental aspects of hard and soft materials integration and the overall system construction were supported by Defense Advanced Research Planning Agency N66001-10-1-4008 and Sharp. The optical design and the theoretical mechanics were supported by National Science Foundation Emerging Frontiers in Research and Innovation, and Electrical, Communications, and Cyber Systems ECCS-0824129, respectively.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1015440108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ko HC, et al. A hemispherical electronic eye camera based on compressible silicon optoelectronics. Nature. 2008;454:748–753. doi: 10.1038/nature07113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grayson T. Curved focal plane wide field of view telescope design. Proc SPIE. 2002;4849:269–274. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rim SB, et al. The optical advantages of curved focal plane arrays. Opt Express. 2008;16:4965–4971. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.004965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dinyari R, et al. Curving monolithic silicon for nonplanar focal plane array applications. Appl Phys Lett. 2008;92:091114-1–091114-3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hung PJ, Jeong KH, Liu GL, Lee LP. Microfabricated suspensions for electrical connections on the tunable elastomer membrane. Appl Phys Lett. 2004;85:6051–6053. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu X, Davanco M, Qi XF, Forrest SR. Direct transfer patterning on three dimensionally deformed surfaces at micrometer resolutions and its application to hemispherical focal plane detector arrays. Org Electron. 2008;9:1122–1127. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung I, et al. Paraboloid electronic eye cameras using deformable arrays of photodetectors in hexagonal mesh layouts. Appl Phys Lett. 2010;96:021110-1–021110-3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko HC, et al. Curvilinear electronics formed using silicon membrane circuits and elastomeric transfer elements. Small. 2009;5:2703–2709. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin G, et al. Micromechanics and advanced designs for curved photodetector arrays in hemispherical electronic-eye cameras. Small. 2010;6:851–856. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proctor NS, Lynch PJ. Manual of Ornithology: Avian Structure and Function. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoskins SG. Metamorphosis of the amphibian eye. J Neurobiol. 1990;21:970–989. doi: 10.1002/neu.480210704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khang DY, Jiang HQ, Huang Y, Rogers JA. A stretchable form of single-crystal silicon for high-performance electronics on rubber substrates. Science. 2006;311:208–212. doi: 10.1126/science.1121401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DH, et al. Ultrathin silicon circuits with strain-isolation layers and mesh layouts for high-performance electronics on fabric, vinyl, leather, and paper. Adv Mater. 2009;21:3703–3707. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DH, et al. Materials and noncoplanar mesh designs for integrated circuits with linear elastic responses to extreme mechanical deformations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18675–18680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807476105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai FS, et al. Miniaturized universal imaging device using fluidic lens. Opt Lett. 2008;33:291–293. doi: 10.1364/ol.33.000291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai FS, et al. Fluidic lens laparoscopic zoom camera for minimally invasive surgery. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15:030504-1–030504-3. doi: 10.1117/1.3420192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu HB, Zhou GY, Leung HM, Chau FS. Tunable liquid-filled lens integrated with aspherical surface for spherical aberration compensation. Opt Express. 2010;18:9945–9954. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.009945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang DY, et al. Fluidic adaptive lens with high focal length tunability. Appl Phys Lett. 2003;82:3171–3172. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang SD, et al. Mechanics of hemispherical electronics. Appl Phys Lett. 2009;95:181912-1–181912-3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song J, et al. Mechanics of noncoplanar mesh design for stretchable electronic circuits. J Appl Phys. 2009;105:123516-1–123516-6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Born M, Wolf E. Principles of Optics. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 1999. pp. 204–210. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walther A. The Ray and Wave Theory of Lenses. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1995. pp. 283–294. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.