Abstract

Objective To review the association between current enterovirus infection diagnosed with molecular testing and development of autoimmunity or type 1 diabetes.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies, analysed with random effects models.

Data sources PubMed (until May 2010) and Embase (until May 2010), no language restrictions, studies in humans only; reference lists of identified articles; and contact with authors.

Study eligibility criteria Cohort or case-control studies measuring enterovirus RNA or viral protein in blood, stool, or tissue of patients with pre-diabetes and diabetes, with adequate data to calculate an odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals.

Results The 24 papers and two abstracts (all case-control studies) that met the eligibility criteria included 4448 participants. Study design varied greatly, with a high level of statistical heterogeneity. The two separate outcomes were diabetes related autoimmunity or type 1 diabetes. Meta-analysis showed a significant association between enterovirus infection and type 1 diabetes related autoimmunity (odds ratio 3.7, 95% confidence interval 2.1 to 6.8; heterogeneity χ2/df=1.3) and clinical type 1 diabetes (9.8, 5.5 to 17.4; χ2/df=3.2).

Conclusions There is a clinically significant association between enterovirus infection, detected with molecular methods, and autoimmunity/type 1 diabetes. Larger prospective studies would be needed to establish a clear temporal relation between enterovirus infection and the development of autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes.

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes is believed to result from a complex interplay between genetic predisposition, the immune system, and environmental factors.1 In recent decades there has been a rapid rise in the incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide, especially in those under the age of 5.2 3 4 5 6 In Europe, from 1989-2003 the average annual increase was 3.9%, too fast to be accounted for by genetics alone.4 Evidence in support of a putative role for viral infections in the development of type 1 diabetes comes from epidemiological studies that have shown a significant geographical variation in incidence, a seasonal pattern to disease presentation,2 3 7 8 and an increased incidence of diabetes after enterovirus epidemics.9

Enteroviruses are perhaps the most well studied environmental factor in relation to type 1 diabetes. A possible link was first reported by Gamble et al in 1969,10 with many subsequent studies, in humans and animal models of diabetes, showing an association, particularly with coxsackievirus B-4. Higher rates of enterovirus infection, defined by detection of enterovirus IgM or IgG, or both, viral RNA with reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT PCR), and viral capsid protein, have been found in patients with diabetes at diagnosis compared with controls.11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Prospective studies have also shown more enterovirus infections in children who developed islet autoantibodies or subsequent diabetes, or both; as well as a temporal relation between infection and autoimmunity.13 18 19 20

The relation between enterovirus infection and diabetes is not consistent across all studies,21 22 23 24 however, and the subject remains controversial.25 Furthermore, in animal models viral infections might also protect from diabetes.25 A systematic review of coxsackie B virus serological studies did not show an association with type 1 diabetes,26 but to date there has been no systematic review of molecular studies. Based on the hypothesis that enterovirus infection increases the risk of pancreatic islet autoimmunity or type 1 diabetes, or both, we carried out a systematic review of controlled studies that used molecular virological methods to investigate the association between enteroviruses and type 1 diabetes.

Methods

Two reviewers (WGY and MEC) independently conducted a systematic search for controlled observational studies of enterovirus and type 1 diabetes mellitus. Databases searched were PubMed (from 1965 to May 2010) and Embase (from 1974 to May 2010). Search terms (exploded, all subheadings) used were: ‘diabetes mellitus’, ‘enterovirus’, ‘coxsackievirus’, ‘ECHOvirus’, ‘polymerase chain reaction’, ‘PCR’, ‘RNA’, ‘DNA’, ‘nucleic acid’, and ‘capsid protein’. The search was limited to studies in humans in any language and was supplemented by hand searching reference lists in the identified papers and by direct contact with authors.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were case-control or cohort studies (including those published as letters or abstracts); measured enterovirus RNA or viral capsid protein in blood, stool, or tissue of patients with pre-diabetes and diabetes; and provided adequate data to enable calculation of odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. No restrictions were placed on the study population. We included only those studies that used molecular methods for viral detection (such as RT-PCR (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction), in situ hybridisation, or immunostaining for detection of viral capsid protein) to identify current or recent infection and because molecular testing is now standard for diagnosis of acute enterovirus infection.

The results of identified studies were classified into two groups, pre-diabetes and diabetes, depending on whether autoimmunity or type 1 diabetes was the outcome. There were four main categories of cases: autoantibody positive, newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes, established type 1 diabetes, and eventual type 1 diabetes. The latter three were combined into the diabetes group.

We calculated unadjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and P values for enterovirus identification in patients with pre-diabetes versus no diabetes and patients with diabetes versus no diabetes from the published figures using the Mantel-Haenszel method. The analysis was performed with both fixed and random effects models. Because of the presence of significant heterogeneity we have presented only the results from random effects models. Combined odds ratios were also calculated for different subgroups of studies according to study design. Statistical heterogeneity was explored with Cochrane’s Q test and the I2 statistic, which provides the relative amount of variance of the summary effect caused by heterogeneity between studies.

We assessed study quality using the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale (NOS) for case-control studies, as recommended by Cochrane collaboration.27 Three areas were evaluated—selection, comparability, and exposure—giving a possible total score 9, with 5 or more classed as good methods. In the comparability category, studies were assessed as to whether they controlled for age and sampling time as these are the two factors most likely to affect the incidence of enterovirus infection.

Results

Our search returned a total of 114 publications and abstracts. After review of titles and abstracts, we identified and included 25 relevant papers—two letters and 23 articles. We also included data from two studies published as abstracts only. All were case-control studies (six were nested case-control studies that used samples collected prospectively20 22 28 29 30). One was excluded because it was a pilot study13 analysing the same data as a duplicate publication.20 Of the 26 remaining studies, eight contained more than one case group14 16 22 31 32 33 34 35 and these were analysed separately, giving a total of 34 studies. Of these, nine were studies of pre-diabetes (198 cases and 733 controls) and 25 were studies of diabetes (1733 cases and 1784 controls).

Characteristics of included studies

Thirty studies used RT-PCR or in situ hybridisation to detect enterovirus RNA, while four performed immunostaining for the enterovirus capsid protein vp1 on autopsy pancreas specimens (tables 1 and 2). Within the pre-diabetes group, all except two of the studies defined autoimmunity as positivity for at least one autoantibody associated with type 1 diabetes (table 1). Study populations varied in age distribution. While most studies investigated children and adolescents (aged 16 and below), some included adults up to age 53.

Table 1.

Summary of molecular studies investigating pre-diabetes and enteroviruses

| Study | Country | Cases/controls | Cases | Autoantibodies detected | Age in cases | Controls | Method of detection | EV type sequenced |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Shaheeb, 201030 | Australia | 13/198 | Autoantibody positive children with first degree relative with T1DM | At least two of ICA, GADA, IA2A, or IAA | Birth cohort from VIGR study | Children from same cohort negative for autoantibody | EV RNA in serum (RT-PCR) | — |

| Coutant, 200232 | France | 5/49 | Autoantibody positive siblings of probands with diabetes | ICA, GADA | Age 2.4-16.5 | Healthy children matched for age, sex, place, and sampling date | EV RNA in serum (RT-PCR) | — |

| Graves, 200322 | USA | 13/13 | Autoantibody positive (eventual); sibling offspring cohort | At least one of IAA, GADA, or ICA | From DAISY cohort study, children at moderate to high risk of developing T1DM | Age matched children from same cohort negative for autoantibody | EV RNA in serum, saliva, and rectal swab (RT-PCR) | — |

| 13/26 | Autoantibody positive (eventual); newborn screened cohort | |||||||

| Moya-Suri, 200533 | Germany | 50/50 | Autoantibody positive | At least one of IAA, GADA, ICA, or IA2A | Median age 12, IQR 10-14 | Children from same cohort negative for autoantibody | EV RNA in serum (RT-PCR) | CVB-4, CVB-2, CVB-6 |

| Salminen, 200320 | Finland | 41/196 | Autoantibody positive children (samples taken 6 months before seroconversion) | At least one of ICA, GADA, IAA, or IA2A | Birth cohort from DIPP study | Children from same cohort negative for autoantibody | EV RNA in serum (RT-PCR) | — |

| Sadeharju, 200328 | Finland | 19/84 | Autoantibody positive (eventual), from Trial to Reduce IDDM in Genetically at Risk (TRIGR) study | At least one of IAA, GADA, or IA2A | Birth cohort from TRIGR study | Children from same study cohort negative for autoantibody and matched for sex, HLA, and intervention group | EV RNA in serum (RT-PCR) | — |

| Salminen, 200429 | Finland | 12/53 | Autoantibody positive (eventual) | At least one | Birth cohort from DIPP study | Children from same study cohort negative for autoantibody (matched for age, sex, and HLA DQ haplotype) | EV RNA in stool samples (RT-PCR) and/or serum | PV-3, CVA-9, CVB-3, CVB-4, CVB-5, EV-3, EV-11, EV-18, EV-24, EV-25 |

| Sarmiento, 200716 | Cuba | 32/63 | First degree relatives with ICA positive T1DM | ICA | Mean age 13.5 (SD 9.5), range 1-46 | Healthy people verified negative for ICA with no family history of diabetes | EV RNA in serum (RT-PCR) | — |

T1DM=type 1 diabetes mellitus; ICA=islet cell autoantibody; GADA=glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibody; IA2A=islet cell antigen antibody; IAA=insulin autoantibody; EV RNA=enterovirus RNA; RT PCA=reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; IQR=interquartile range.

Table 2.

Summary of molecular studies investigating type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and enteroviruses

| Study | Country | Cases/controls | Cases and details of diabetes | Age of cases (years unless specified) | Controls | Method of detection | EV type sequenced |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andreoletti, 199714 | France | 12/15 | Newly diagnosed with metabolic decompensation | Mean 28.2 (SD 10.4) | Healthy adults | EV RNA in peripheral blood (RT PCR) | CVB-3, CVB-4 |

| Previously diagnosed with metabolic decompensation | Mean 32.6 (SD 13.3) | ||||||

| Buesa-Gomez, 199460 | USA | 2/5 | Fatal acute onset | 14 months and 3 years | Children who died from non-diabetic causes | Coxsackie RNA in autopsy pancreatic samples (RT PCR) | — |

| Clements, 199541 | UK | 14/45 | Newly diagnosed | Mean 3.9, range 1.4-6.0 | Normal subjects matched for age, sex, sample date, and place | EV RNA in serum (RT PCR) | CVB-3, CVB-4 |

| Coutant, 200232 | France | 16/49 | Newly diagnosed (within 1 month of diagnosis) | Range <6 | Healthy children matched for age, sex, sample date, and place | EV RNA in serum (RT PCR) | — |

| Craig, 200358 | Australia | 206/160 | Newly diagnosed (within 2 weeks of diagnosis) | Median 8.2, range 0.7-15.7 | Children without diabetes from community | EV RNA in plasma or stool samples (RT PCR) | EV-71 |

| Dahlquist, 200436 | Sweden | 600/600 | Eventual diabetes, on Swedish childhood diabetes register | Neonate | People without diabetes from same biobank | EV RNA in newborn blood spots (RT PCR) | — |

| Dotta, 200746 | Italy | 6/26 | Recent onset | Range 14-50 | Normal multi-organ donors | EV vp1 immunostaining in autopsy pancreatic samples (Dako anti-vp1) | CVB-4 |

| Foulis, 199038 | UK | 147/43 | 88 recent onset (duration <1 year), 59 established (duration 1-19 years) | Range 1-37 | Normal autopsy pancreases from 11 neonates, 21 children, 11 adults | EV vp1 immunostaining in autopsy pancreatic samples | — |

| Foy, 199535 | UK | 17/42 | Newly diagnosed (on day of diagnosis) | Median 11, range 2-35 | Patients without diabetes, matched for age and sex | EV RNA in peripheral blood (RT PCR) | — |

| 38/42 | Duration 2 months-10 years | Median 11, range 3-16 | |||||

| Kawashima 200461 | Japan | 61/58 | Type 1 diabetes | Range 9 months - 40 years | Healthy people | EV RNA in serum (RT PCR) | CVB-2, CVB-3, CVB-4, CVB-5 |

| Lönnrot, 200031 | Finland | 11/34 | Eventual diabetes, from DiMe Study | Mean 8.4, range 2.6-17 | Children from same study cohort who did not develop T1DM or autoantibodies | EV RNA in serum (RT PCR) | — |

| 47/34 | Newly diagnosed | Mean 4.4 | |||||

| Maha, 200334 | Egypt | 40/30 | Recent onset (<1 year) | Mean 11.30 (SD 2.16) | Normal healthy children | EV RNA in serum (RT PCR via tissue culture) | CVB-4, CVB-6 |

| 30/30 | Duration >1 year | Mean 11.80 (SD 2.70) | |||||

| Moya-Suri, 200533 | Germany | 47/50 | Newly diagnosed (median 5 days from diagnosis) | Median 13, IQR 11-15 | Children from same study negative autoantibodies | EV RNA in serum (RT PCR) | CVB-4, CVB-2, CVB-6 |

| Nairn, 199912 | UK | 110/182 | Newly diagnosed (within 1 week from diagnosis) | Mean 7.1, range 3 months-16 years | Children without diabetes (matched for age, location, time of sampling) | EV RNA in serum (RT PCR) | PV1-3, CVA-21, CVA-24, EV-70 |

| Oikarinen, 200739 | Finland | 12/10 | Established (duration 0-51 years, median 13) | Median 30, range 18-53 | Patients without diabetes from same hospital department | vp1 immunostaining in small bowel mucosa (Dako anti-vp1) | — |

| Richardson, 200917 | UK | 72/119 | Recent onset (8.2 (SD 4.1) months from diagnosis) | Mean 12.65 (SD 1.1), range 1-42 | Normal autopsy pancreases from 11 neonates, 39 children and 69 adults | EV vp1 immunostaining in autopsy pancreatic samples (Dako anti-vp1) | — |

| Sarmiento, 200716 | Cuba | 34/68 | Newly diagnosed (0.78 (SD 2.4) days from diagnosis) | Mean 7.3 (SD 4.5), range 1-15 | Healthy subjects, verified ICA negative and no family history of diabetes | EV RNA in serum (RT PCR) | — |

| Schulte, 201043 | Nether-lands | 10/20 | Newly diagnosed (within 1 month of diagnosis) | Mean 9.7, range 5-14 | Children of same age range in hospital with non-endocrine disorders | EV RNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (RT PCR) | HEV-B |

| Toniolo, 201044 | Italy | 112/58 | Newly diagnosed | Mean 6.8, median 9.0, range 2-16 |

Healthy children | EV RNA in peripheral blood (RT PCR) | HEV-A, HEV-B, HEV-C, HEV-D |

| Yin, 200240 | Sweden | 24/24 | Newly diagnosed (within 1 week from diagnosis) | Mean 8.4, range 1.6-15.7 | Healthy children from nearby counties | EV RNA in PBMCs (RT PCR) | CVB-5, EV-5, CVB-4 |

| Ylipaasto, 200442 | Finland/ Germany | 65/40 | Duration: few weeks to 19 years | Range 18-52 | Non-diabetic pancreases (age-sex matched) | EV RNA in autopsy pancreatic samples (RNA probes and in situ hybridisation) | — |

EV RNA=enterovirus RNA; RT PCA=reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

Quality of evidence

The Newcastle-Ottawa scores ranged from 3 to 8, with 24 studies scoring 5 or more (table 3), indicating reasonably good methodological quality overall, with no studies reporting a non-response rate.

Table 3.

Quality of evidence in molecular studies investigating type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and enteroviruses

| Study | NHMRC level of evidence* | Newcastle-Ottawa scale score | Diagnostic criteria for autoimmunity and/or type 1 diabetes given? | Cases and controls matched? | Details of viral detection given? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | HLA | Place | Sample time | |||||

| Andreoletti, 199714 | III-3 | 4 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (referenced) |

| Al-Shaheeb, 201030 | II | 7 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Buesa-Gomez, 199460 | III-3 | 4 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Clements, 199541 | III-3 | 6 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Coutant, 200232 | III-3 | 6 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Craig, 200358 | III-3 | 6 | Yes (diabetes register) | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Dahlquist, 200436 | II | 7 | Yes (diabetes register) | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes (referenced) |

| Dotta, 200746 | III-3 | 5 | No | No | No | No | No | NA | Yes |

| Foulis, 199038 | III-3 | 3 | No | No | No | No | No | NA | Yes |

| Foy, 199535 | III-3 | 6 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Graves, 200322 | II | 7 | Yes for autoimmunity, no for diabetes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kawashima, 200461 | III-3 | 5 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Lönnrot, 200031 | II | 6 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Maha, 200334 | III-3 | 5 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Moya-Suri, 200533 | III-3 | 7 | Yes for autoimmunity, no for diabetes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Nairn, 199912 | III-3 | 7 | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes (referenced) |

| Oikarinen, 200739 | III-3 | 4 | No | No | No | No | No | NA | Yes |

| Richardson, 200917 | III-3 | 4 | No | No | No | No | No | NA | Yes |

| Sadeharju, 200328 | II | 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes (referenced) |

| Salminen, 200320 | II | 6 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes (referenced) |

| Salminen, 200429 | II | 7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Sarmiento, 200716 | III-3 | 6 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Schulte, 201043 | III-3 | 4 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Toniolo, 201044 | III-3 | 7 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Yin, 200240 | III-3 | 7 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Ylipaasto, 200442 | III-3 | 5 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

NA=not available.

*II=nested case-control study; III-3=case-control study.59

Pre-diabetes

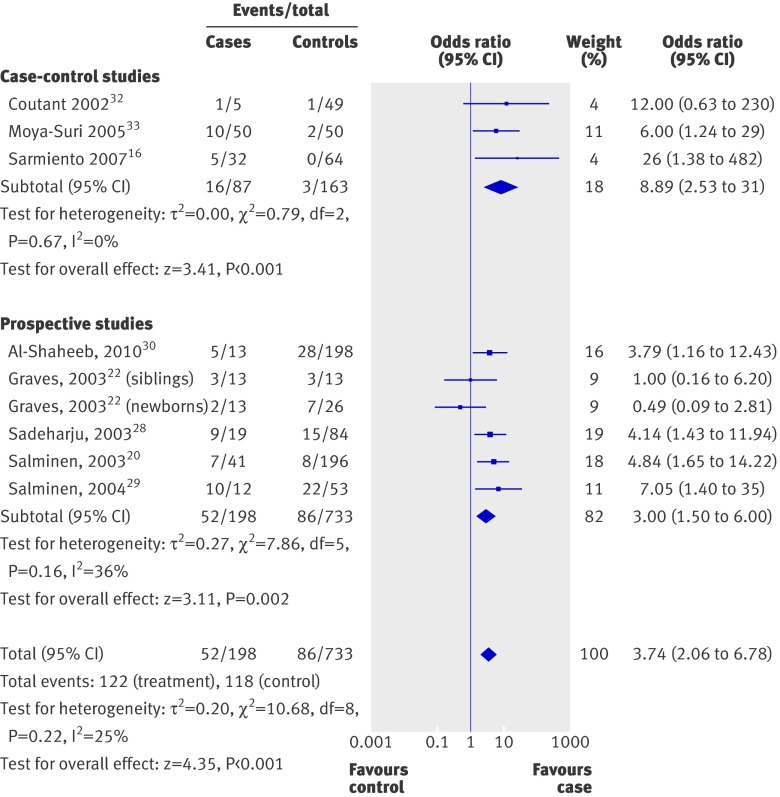

Figure 1 presents the individual and summary odds ratio of the nine pre-diabetes studies . Odds ratios ranged from 0.1 to 483, with a summary odds ratio of 3.7 (95% confidence interval 2.1 to 6.8; P<0.001). There was some evidence for heterogeneity across the studies (χ2/df=1.34), but this value did not reach significance (P=0.22). When we analysed the results from the six nested case-control studies separately, the summary odds ratio was 3.0 (1.5 to 6.0; P=0.002) (table 4).

Fig 1 Odds ratios for enterovirus positivity in patients with pre-diabetes versus no diabetes

Table 4.

Combined odds ratios for pre-diabetes studies stratified by study type

| Type of study | No of studies | Combined OR (95% CI) | P value | χ2/df* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 9 | 3.7 (2.1 to 6.8) | <0.001 | 1.34 |

| Nested case-control studies | 6 | 3.0 (1.5 to 6.0) | 0.002 | 1.57 |

| Studies in Europe | 5 | 5.2 (2.8 to 9.6) | <0.001 | 0.17 |

*Cochrane χ2 divided by degrees of freedom. Values >1 indicate heterogeneity.

Three of the nested case-control studies also separately examined the six or 12 month period preceding the first appearance of autoantibodies.20 22 The summary odds ratio was 3.6 (1.3 to 9.8; P=0.01). Five studies also sequenced the HLA haplotypes of their participants and two included those with low risk HLA genotypes. For those with high HLA risk haplotypes (five studies, 112 cases, 551 controls), the combined odds ratio was 3.5 (1.7 to 7.1; P<0.001).20 22 28 29 30 Only two studies (21 cases, 158 controls) included participants with low risk HLA genotypes, with conflicting results (0.4, (0.04 to 4.8)22 and 9.3 (1.9 to 45)30), but the combined odds ratio was not significant (2.3, 0.1 to 56; P=0.62).

Type 1 diabetes

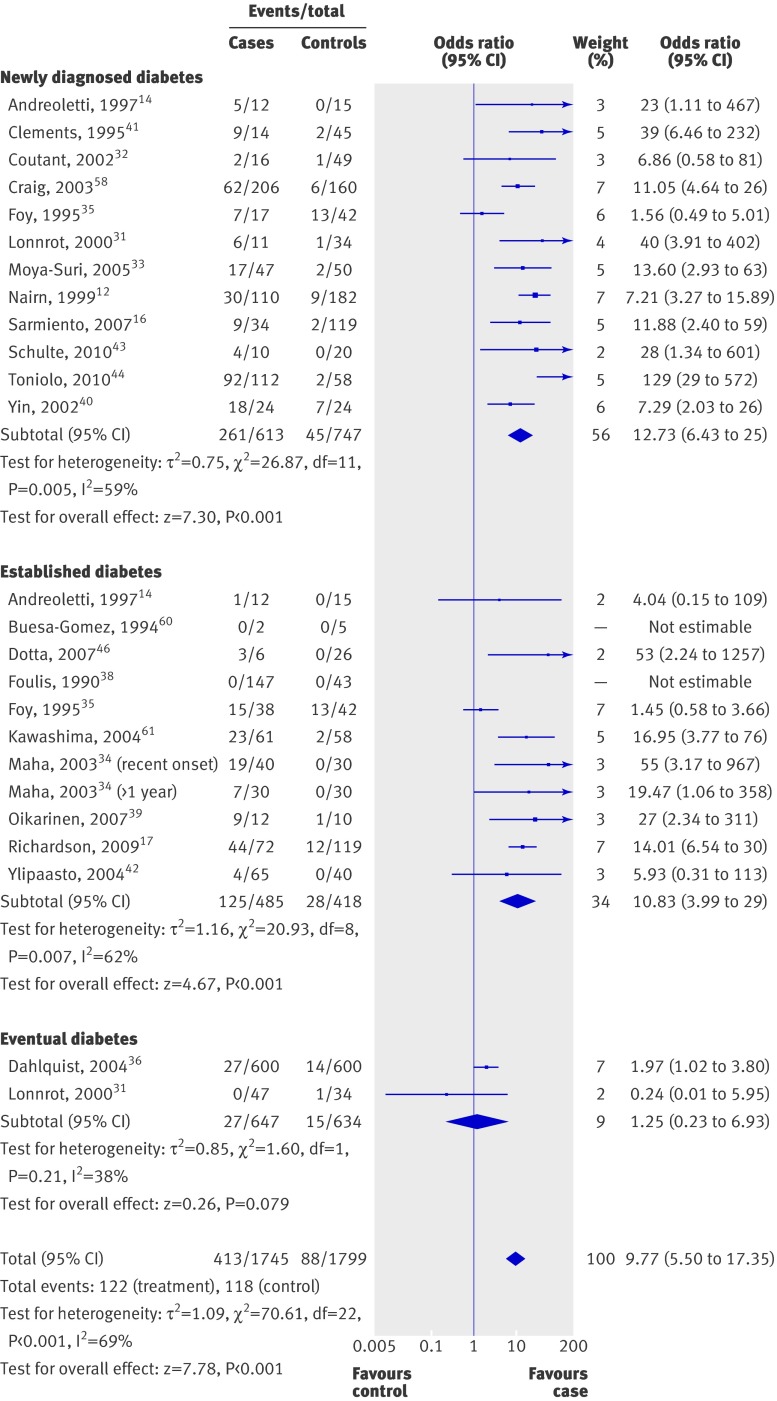

Figure 2 shows the individual and summary odds ratios of the 25 studies of patients with type 1 diabetes . All studies except one32 showed an odds ratio over 1 for enterovirus positivity in patients with diabetes. Odds ratios ranged from 0.24 to 129, with a summary odds ratio of 10 (5.5 to 17; P<0.001). There was significant heterogeneity across the studies (χ2/df=3.21; P<0.001).

Fig 2 Odds ratios for enterovirus positivity in patients with and without diabetes

We carried out a subgroup analysis with respect to method of enterovirus detection (RNA or capsid protein) and case selection (newly diagnosed v established v eventual diabetes; table 5, fig 2). The combined odds ratios for newly diagnosed, established, and eventual diabetes were 13 (6 to 25), 11 (4 to 29), and 1.25 (0.2 to 7), respectively. The combined odds ratio of studies that used RNA detection was 8.8 (4.7 to 17; P<0.001), while for studies that performed immunostaining for enterovirus capsid protein, the odds ratio was 15 (7.5 to 31). There was no significant heterogeneity across studies that measured enteroviral vp1 protein, probably because of the similarity in study design.

Table 5.

Summary odds ratios of diabetes studies including sensitivity analyses

| No of studies | OR (95% CI) | P value | χ2/df* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes (all studies) | 25 | 9.8 (5.5 to 17.4) | <0.001 | 3.21 |

| Method of virus detection: | ||||

| RNA | 21 | 8.8 (4.7 to 16.7) | <0.001 | 3.37 |

| vp1 | 4 | 15.4 (7.5 to 31.5) | <0.001 | 0.35 |

| Case definition: | ||||

| Newly diagnosed | 12 | 12.7 (6.4 to 25.2) | <0.001 | 2.44 |

| Established (including recent onset) | 11 | 10.8 (4.0 to 29.4) | <0.001 | 2.62 |

| Eventual | 2 | 1.3 (0.2 to 6.9) | 0.79 | 1.60 |

| Study location: | ||||

| Europe only | 19 | 8.6 (4.3 to 17.3) | <0.001 | 3.75 |

| Non-European countries | 6 | 13.5 (7.1 to 25.8) | <0.001 | 0.34 |

| Study quality: | ||||

| NOS score ≥5 | 18 | 9.0 (4.6 to 17.5) | <0.001 | 3.77 |

NOS=Newcastle-Ottawa.

*Cochrane χ2 divided by degrees of freedom. Values >1 indicate heterogeneity.

We used sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the results by country and study quality. For the 19 studies conducted in Europe,12 14 17 31 32 33 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 the combined odds ratio was 8.6 (4.3 to 17; P<0.001), with significant heterogeneity (χ2/df=3.75, P<0.001). The odds ratio was comparatively higher for the non-European studies (13.5, 7.1 to 26), with low heterogeneity, though there was considerable overlap of the confidence intervals between the two groups. When we excluded the studies with poor methodological quality (Newcastle-Ottawa score <5), the combined odds ratio was similar (8.9, 4.6 to 17; P<0.001). Subgroup analysis by HLA genotype was not performed because none of the studies performed HLA genotyping on all cases and controls.

Discussion

This systematic review of 33 prevalence studies, involving 1931 cases and 2517 controls, shows a clinically significant association between enterovirus infection and islet autoimmunity or type 1 diabetes. The association between enterovirus infection, detected with molecular methods, and diabetes was strong, with almost 10 times the odds of enterovirus infection in children at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes compared with controls (9.8, 5.5 to 17.4), while the odds of infection was also higher in children with pre-diabetes than in controls (3.7, 2.1 to 6.8). There was some evidence for geographical differences; in non-European studies the odds ratio was 13.5 (7.1 to 25.8) compared with 8.6 (4.3 to 17.3) in European studies, though there was considerably overlap in the confidence intervals. While the findings from this meta-analysis of observational studies cannot prove that enterovirus infection has a causal role in pathogenesis of diabetes, the results provide additional support to the direct evidence of enterovirus infection in pancreatic tissue of individuals with type 1 diabetes.45 46

Strengths and weaknesses

We made every effort to reduce potential bias in this review, through use of pre-defined inclusion criteria, independent searches by two reviewers, no language restriction, and searching of references lists and conference proceedings. We included studies in children and adults, reducing the risk of bias resulting from high rates background infection in children.47 48 Studies from throughout the world were included, reducing the risk of geographical bias related to infection rates. Most studies, however, were from European countries, where the incidence of type 1 diabetes is higher. Given the heterogeneity of the study populations, we used random effects models, providing more conservative effect estimates.

Several limitations could have influenced our findings, including factors inherent in a meta-analysis of observational studies. There was significant heterogeneity in study design and methods used. Only 10 studies matched for three or more potential confounding factors (age, genetic risk, geographical location, and sampling time). Most of the included studies used children without diabetes or who were negative for antibodies as controls, but there could have been unmeasured factors influencing their risk of developing diabetes. Other environmental factors might modify the risk of type 1 diabetes, such as cows’ milk,49 vitamin D,50 and weight gain in infancy,51 but it is not possible to control for all of these potential confounders in case-control studies. Finally, enterovirus PCR primers had varying sensitivity and specificity, and not all studies reported the validation and limits of detection of their PCR method. Samples were obtained from various sites (serum, stool, throat swabs, etc) and because enteroviruses invade and replicate at mucosal surfaces, detection rates are likely to be higher in samples obtained from the gastrointestinal tract.52 53

The overall methodological quality of the studies of the studies was relatively good, with 26 publications scoring 5 or more of 9 on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. Eleven studies included fewer than 50 participants, giving rise to the possibility of small study effects. The four largest studies of diabetes (involving more than 1000 cases and controls), however, showed a clear association between enterovirus infection and clinical diabetes.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

A previous meta-analysis of coxsackie B virus serological studies found no significant association between type 1 diabetes and serology positivity,26 though summary estimates were not calculated because of significant heterogeneity between studies. Several major differences between the two meta-analyses could explain the discrepant findings. Firstly, most studies included in our review detected most enteroviruses by using PCR primers targeting the highly conserved 5′ untranslated region of the enterovirus genome, whereas serological studies examined only certain serotypes. Secondly, molecular methods for detection of enteroviruses are significantly more sensitive than serology.54 55 Thirdly, the detection of enterovirus RNA or vp1 identifies only current or recent infection. The latter is also a limitation of molecular methods, though this would probably cause bias towards under-reporting of infection rates and estimation of a lower than actual effect size. We could not examine whether participants had multiple enterovirus infections or the same persistent infection before the development of autoimmunity or type 1 diabetes.

Autoimmunity was mostly defined as a positive result for at least one autoantibody associated with type 1 diabetes, and the presence of a single antibody does not confer a high lifetime risk of clinical diabetes compared with positive results for multiple antibodies.56 57 Prospective studies are also limited by the frequency of sample collection, which might be only six or 12 months apart, and it is noteworthy that the only prospective study reporting an odds ratio under 1 had the longest sampling intervals.22 A temporal association between seroconversion to autoimmunity and infection could be under-reported because of lack of sampling at the time of infection or seroconversion, or both, in some individuals.

Maternal enterovirus infection might also be a risk factor for autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes. We did not specify maternal infection in our inclusion criteria, though among the “eventual diabetes” group enterovirus RNA was more commonly detected in dried blood spots from newborn infants who subsequently developed type 1 diabetes. Two of the included studies in the pre-diabetes group examined maternal enterovirus infection by using serology and showed little or no association between infection and subsequent development of autoimmunity in their offspring.20 28

There is conflicting evidence as to whether the presence or absence of high risk HLA genotypes modifies the association between enterovirus infection and type 1 diabetes. Several groups have reported higher rates of enterovirus infection in children with low risk HLA genotypes.16 58 Unfortunately, we could not do a subgroup analysis by HLA genotype in the diabetes studies because most studies did not do HLA genotyping in control participants. In the pre-diabetes group, the odds ratio of enterovirus infection in high risk HLA participants (3.5) was not different from the overall odds ratio (3.4), and the conflicting results from the two studies with low risk participants do not support an association between enterovirus infection and autoimmunity. Ideally, future studies should include individuals with low risk HLA genotypes to explore whether genetic risk modifies the effect of enterovirus infection on the risk of type 1 diabetes.

Conclusion

Our results show an association between type 1 diabetes and enterovirus infection, with a more than nine times the risk of infection in cases of diabetes and three times the risk in children with autoimmunity. The odds of having an enterovirus infection in people with established diabetes (odds ratio 11) suggest that persistent enterovirus infection is also common among patients with type 1 diabetes. While it is not possible to determine a causal relation between infection and type 1 diabetes with a randomised controlled trial, larger multicentre international prospective studies could examine interactions between type 1 diabetes and various environmental, geographical, and genetic factors.

What is already known on this topic

Observational studies have shown an association between enteroviruses and type 1 diabetes

A systematic review of serological studies only found no association

What this study adds

A review of molecular studies showed an association between current enterovirus infection and type 1 diabetes

Contributors: WGY performed the literature search, extracted, analysed, and interpreted the data, and drafted the article. MEC conceived and designed the review, helped extract and interpret the data, and revised the article critically for intellectual content. WDR revised the article critically for intellectual content and approved the final draft for publication. WDR is guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;342:d35

References

- 1.Hober D, Sauter P. Pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes mellitus: interplay between enterovirus and host. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2010;6:279-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamond PG. Incidence and trends of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide 1990-1999. Diabet Med 2006;23:857-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.EURODIAB. Variation and trends in incidence of childhood diabetes in Europe. Lancet 2000;355:873-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson C, Dahlquist G, Gyürüs E, Green A, Soltész G. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989-2003 and predicted new cases 2005-20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet 2009;373:2027-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong J, Craig M, Cameron F, Clarke C, Rodda C, Donath S, et al. Marked increase in type 1 diabetes mellitus incidence in children aged 0-14 yrs in Victoria, Australia, from 1999 to 2002. Pediatr Diabetes 2007;8:67-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taplin C, Craig M, Lloyd M, Taylor C, Crock P, Silink M, et al. The rising incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes in New South Wales, 1990-2002. Med J Aust 2005;183:243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green A, Patterson C. Trends in the incidence of childhood-onset diabetes in Europe 1989-1998. Diabetologia 2001;44:3-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimpimaki T, Kupila A, Hamalainen AM, Kukko M, Kulmala P, Savola K, et al. The first signs of B-cell autoimmunity appear in infancy in genetically susceptible children from the general population: the Finnish Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:4782-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagenknecht LE, Roseman JM, Herman WH. Increased incidence of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus following an epidemic of coxsackievirus B5. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133:1024-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gamble D, Kinsley M, Fitzgerald M, Bolton R, Taylor K. Viral antibodies in diabetes mellitus. BMJ 1969;3:627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helfand RF, Gary HE Jr, Freeman CY, Anderson LJ, Pallansch MA. Serologic evidence of an association between enteroviruses and the onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pittsburgh Diabetes Research Group. J Infect Dis 1995;172:1206-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nairn C, Galbraith DN, Taylor KW, Clements GB. Enterovirus variants in the serum of children at the onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 1999;16:509-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lönnrot M, Korpela K, Knip M, Ilonen J, Simell O, Korhonen S, et al. Enterovirus infection as a risk factor for beta-cell autoimmunity in a prospectively observed birth cohort: the Finnish Diabetes Prediction and Prevention Study. Diabetes 2000;49:1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreoletti L, Hober D, Hober-Vandenberghe C, Belaich S, Vantyghem MC, Lefebvre J, et al. Detection of coxsackie B virus RNA sequences in whole blood samples from adult patients at the onset of type I diabetes mellitus. J Med Virol 1997;52:121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig ME, Howard NJ, Silink M, Rawlinson WD. Reduced frequency of HLA DRB1*03-DQB1*02 in children with type 1 diabetes associated with enterovirus RNA. J Infect Dis 2003;187:1562-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarmiento L, Cabrera-Rode E, Lekuleni L, Cuba I, Molina G, Fonseca M, et al. Occurrence of enterovirus RNA in serum of children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes and islet cell autoantibody-positive subjects in a population with a low incidence of type 1 diabetes. Autoimmunity 2007;40:540-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson S, Willcox A, Bone A, Foulis A, Morgan N. The prevalence of enteroviral capsid protein vp1 immunostaining in pancreatic islets in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2009;52:1143-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyöty H, Hiltunen M, Knip M, Laakkonen M, Vähäsalo P, Karjalainen J, et al. A prospective study of the role of coxsackie B and other enterovirus infections in the pathogenesis of IDDM. Childhood Diabetes in Finland (DiMe) Study Group. Diabetes 1995;44:652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiltunen M, Hyöty H, Knip M, Ilonen J, Reijonen H, Vähäsalo P, et al. Islet cell antibody seroconversion in children is temporally associated with enterovirus infections. J Infect Dis 1997;175:554-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salminen K, Sadeharju K, Lönnrot M, Vähäsalo P, Kupila A, Korhonen S, et al. Enterovirus infections are associated with the induction of beta-cell autoimmunity in a prospective birth cohort study. J Med Virol 2003;69:91-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuvemo T, Dahlquist G, Frisk G, Blom L, Friman G, Landin-Olsson M, et al. The Swedish childhood diabetes study III: IgM against coxsackie B viruses in newly diagnosed type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic children—no evidence of increased antibody frequency. Diabetologia 1989;32:745-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graves P, Rotbart H, Nix W, Pallansch M, Erlich H, Norris J, et al. Prospective study of enteroviral infections and development of beta-cell autoimmunity: diabetes autoimmunity study in the young (DAISY). Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2003;59:51-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hadden D, Connolly J, Montgomery D, Weaver J. Coxsackie B virus diabetes. BMJ 1972;4:729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juhela S, Hyoty H, Roivainen M, Harkonen T, Putto-Laurila A, Simell O, et al. T-cell responses to enterovirus antigens in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2000;49:1308-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filippi CM, von Herrath MG. Viral trigger for type 1 diabetes: pros and cons. Diabetes 2008;57:2863-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green J, Casabonne D, Newton R. Coxsackie B virus serology and type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of published case-control studies. Diabet Med 2004;21:507-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells G, Shea BO, Connell D. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis. 2010. www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 28.Sadeharju K, Hamalainen AM, Knip M, Lonnrot M, Koskela P, Virtanen SM, et al. Enterovirus infections as a risk factor for type I diabetes: virus analyses in a dietary intervention trial. Clin Exp Immunol 2003;132:271-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salminen KK, Vuorinen T, Oikarinen S, Helminen M, Simell S, Knip M, et al. Isolation of enterovirus strains from children with preclinical type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2004;21:156-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Shaheeb A, Talati R, Catteau J, Sanderson K, Niang Z, Rawlinson W, et al. Enterovirus infections are common in children at risk of type 1 diabetes and associated with transient and persistent autoimmunity. Diabetes 2010;59(suppl 1):A 67-OR. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lönnrot M, Salminen K, Knip M, Savola K, Kulmala P, Leinikki P, et al. Enterovirus RNA in serum is a risk factor for beta-cell autoimmunity and clinical type 1 diabetes: a prospective study. J Med Virol 2000;61:214-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coutant R, Palmer P, Carel JC, Cantero-Aguilar L, Lebon P, Bougneres PF. Detection of enterovirus RNA sequences in serum samples from autoantibody-positive subjects at risk for diabetes. Diabet Med 2002;19:968-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moya-Suri V, Schlosser M, Zimmermann K, Rjasanowski I, Gurtler L, Mentel R. Enterovirus RNA sequences in sera of schoolchildren in the general population and their association with type 1-diabetes-associated autoantibodies. J Med Microbiol 2005;54:879-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maha MM, Ali MA, Abdel-Rehim SE, Abu-Shady EA, El-Naggar BM, Maha YZ. The role of coxsackieviruses infection in the children of insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Egyptian Public Health Assoc 2003;78:305-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foy CA, Quirke P, Lewis FA, Futers TS, Bodansky HJ. Detection of common viruses using the polymerase chain reaction to assess levels of viral presence in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Diabet Med 1995;12:1002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dahlquist G, Forsberg J, Hagenfeldt L, Boman J, Juto P. Increased prevalence of enteroviral RNA in blood spots from newborn children who later developed type 1 diabetes: a population-based case-control study. Diabetes Care 2004;27:285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dotta F, Censini S, van Halteren A, Marselli L, Masini M, Dionisi S, et al. Coxsackie B4 virus infection of cells and natural killer cell insulitis in recent-onset type 1 diabetic patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:5115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foulis AK, Farquharson MA, Cameron SO, McGill M, Schönke H, Kandolf R. A search for the presence of the enteroviral capsid protein VP1 in pancreases of patients with type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes and pancreases and hearts of infants who died of coxsackieviral myocarditis. Diabetologia 1990;33:290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oikarinen M, Tauriainen S, Honkanen T, Oikarinen S, Vuori K, Kaukinen K, et al. Detection of enteroviruses in the intestine of type 1 diabetic patients. Clin Exp Immunol 2007;151:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin H, Berg A-K, Tuvemo T, Frisk G. Enterovirus RNA is found in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in a majority of type 1 diabetic children at onset. Diabetes 2002;51:1964-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clements GB, Galbraith DN, Taylor KW. Coxsackie B virus infection and onset of childhood diabetes. Lancet 1995;346:221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ylipaasto P, Klingel K, Lindberg AM, Otonkoski T, Kandolf R, Hovi T, et al. Enterovirus infection in human pancreatic islet cells, islet tropism in vivo and receptor involvement in cultured islet beta cells. Diabetologia 2004;47:225-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulte BM, Bakkers J, Lanke KHW, Melchers WJG, Westerlaken C, Allebes W, et al. Detection of enterovirus RNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of type 1 diabetic patients beyond the stage of acute infection. Viral Immunol 2010;23:99-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toniolo A, Maccari G, Federico G, Salvatoni A, Bianchi G, Baj A. Are enterovirus infections linked to the early stages of type 1 diabetes? American Society for Microbiology Meeting, San Diego, CA; 23-27 May 2010 (abstract).

- 45.Yoon JW, Austin M, Onodera T, Notkins AL. Isolation of a virus from the pancreas of a child with diabetic ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med 1979;300:1173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dotta F, Censini S, van Halteren A, Marselli L, Masini M, Dionisi S, et al. Coxsackie B4 virus infection of cells and natural killer cell insulitis in recent-onset type 1 diabetic patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2007;104:5115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacques J, Moret H, Minette D, Leveque N, Jovenin N, Deslee G, et al. Epidemiological, molecular, and clinical features of enterovirus respiratory infections in French children between 1999 and 2005. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tseng F, Huang H, Chi C, Lin T, Liu C, Jian J, et al. Epidemiological survey of enterovirus infections occurring in Taiwan between 2000 and 2005: analysis of sentinel physician surveillance data. J Med Virol 2007;79:1850-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luopajärvi K, Savilahti E, Virtanen S, Ilonen J, Knip M, Åkerblom H, et al. Enhanced levels of cow’s milk antibodies in infancy in children who develop type 1 diabetes later in childhood. Pediatr Diabetes 2008;9:434-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bener A, Alsaied A, Al-Ali M, Al-Kubaisi A, Basha B, Abraham A, et al. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in type 1 diabetes mellitus and healthy children. Acta Diabetol 2009;46:183-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Couper J, Beresford S, Hirte C, Baghurst P, Pollard A, Tait B, et al. Weight gain in early life predicts risk of islet autoimmunity in children with a first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doornum GJJ, Schutten M, Voermans J, Guldemeester GJJ, Niesters HGM. Development and implementation of real-time nucleic acid amplification for the detection of enterovirus infections in comparison to rapid culture of various clinical specimens. J Med Virol 2007;79:1868-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rotbart HA, Hayden FG. Picornavirus infections: a primer for the practitioner. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:913-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Doornum G, Schutten M, Voermans J, Guldemeester G, Niesters H. Development and implementation of real-time nucleic acid amplification for the detection of enterovirus infections in comparison to rapid culture of various clinical specimens. J Med Virol 2007;79:1868-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iturriza-Gómara M, Megson B, Gray J. Molecular detection and characterization of human enteroviruses directly from clinical samples using RT-PCR and DNA sequencing. J Med Virol 2006;78:243-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barker JM, Barriga KJ, Yu L, Miao D, Erlich HA, Norris JM, et al. Prediction of autoantibody positivity and progression to type 1 diabetes: Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:3896-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hummel M, Bonifacio E, Schmid S, Walter M, Knopff A, Ziegler A. Brief communication: early appearance of islet autoantibodies predicts childhood type 1 diabetes in offspring of diabetic parents. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Craig ME, Howard NJ, Silink M, Rawlinson WD. Reduced frequency of HLA DRB1*03-DQB1*02 in children with type 1 diabetes associated with enterovirus RNA. J Infect Dis 2003;187:1562-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.NHMRC. NHMRC additional levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines. Australian Government, 2009.

- 60.Buesa-Gomez J, de la Torre JC, Dyrberg T, Landin-Olsson M, Mauseth RS, Lernmark A, et al. Failure to detect genomic viral sequences in pancreatic tissues from two children with acute-onset diabetes mellitus. J Med Virol 1994;42:193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kawashima H, Ihara T, Ioi H, Oana S, Sato S, Kato N, et al. Enterovirus-related type 1 diabetes mellitus and antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase in Japan. J Infect 2004;49:147-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]