Abstract

Described herein is a method for the joining of complex peptides to complex oligosaccharides via an N-linkage. The ω-aspartylation is conducted with coupling fully deprotected glycosylamine with a peptide containing a unique thioacid at the ω-aspartate carboxyl. In the presence of HOBT, under conditions which, in principle, allow for oxidation, complex components are combined in encouraging yields to produce structurally and stereochemically defined N-linked glycopolypeptides wherein the carbohydrate domain can be quite complex. Various mechanisms for oxidative coupling are proposed.

Introduction

Glycoproteins play pivotal roles in an array of biological processes, from intercellular communication to neuronal development and fertilization.1,2,3 For instance, protein glycosylation is understood to be essential in promoting proper protein folding, thereby governing proteolytic stability. Unfortunately, rigorous investigations as to the relationship between the structure and function of glycoproteins have been complicated by the often prohibitive difficulties in obtaining homogeneous samples from natural sources. This situation arises from the fact that glycoproteins, biosynthesized through nonspecific post-translational glycosylation, are typically isolated as horrific mixtures of difficultly separable glycoforms.

Our laboratory,4 and others,5 have sought to respond to this challenge through the development of general strategies for the de novo chemical synthesis of homogeneous glycoproteins. Notwithstanding substantial advances in this regard, the total synthesis of significantly sized N-linked glycopolypeptides, let alone N-linked glycoproteins, remains a daunting task. The challenges can be encompassed in four broad categories: (i) assembly of complex oligosaccharide fragments; (ii) actual merger of the oligosaccharide and peptide domains; (iii) ligation of component glycopeptide and peptide fragments to provide the fully elaborated glycoprotein structure; and (iv) deprotection, if necessary.

In the past two decades, our laboratory has attempted to advance the field of glycopeptide and glycoprotein synthesis through the development of enabling methodologies, both in constructing oligosaccharides and in combining polypeptides, including glycopolypeptides. Recent years have brought forth major advances in the ability to reach single glycoforms of even highly complex oligosaccharide targets. One of the initiatives from our laboratory involved the development of “glycal assembly” for carbohydrate synthesis.6 This method provides access to very complex, highly branched oligosaccharides with generally excellent levels of stereocontrol, while easing the complexities of protecting group management. Additionally, significant efforts in our laboratory have focused on the development of a broad menu of useful methods for the ligation of peptide and glycopeptide fragments.7,8,9 However, at the outset of the program we describe herein, solutions to the second challenge stated above; i.e., the actual construction of the β-N-linkage required to connect the oligosaccharide and peptidic domains in nature’s way, remained problematic.

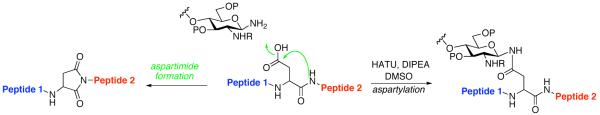

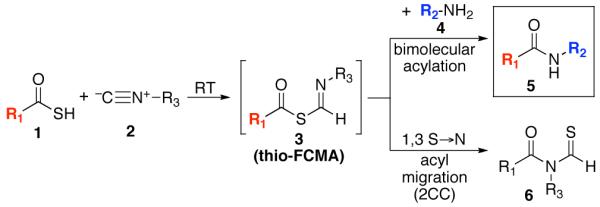

The current, state-of-the-art method for merging glycans to peptides through a natural N-linkage10 involves appendage of a fully deprotected anomeric β-glycosylamine of a complex oligosaccharide, to a properly protected and differentiated, ω-aspartoyl acyl donor in the setting of a peptide, i.e. the Lansbury reaction.11 This approach must overcome several limitations. First, the anomeric glycan amine is relatively weakly nucleophilic and is also vulnerable to hydrolytic conversion to the free reducing sugar. The ω-aspartylation reaction can be seriously compromised by a competing side reaction, wherein, in the presence of a requisite base (such as diisopropylethylamine [DIPEA]), the activated ω-aspartyl donor undergoes cyclization with the NH of the adjacent amino acid. Depending on the nature of the peptide and the amount of base used, the levels of aspartimide formation may be prohibitive.12 For instance, when the next amino acid located at the C-terminus of the aspartate residue is of the glycine, serine, or alanine type, aspartimide formation is particularly pronounced. Since the weak nucleophilicity and the lability of the anomeric glycosylamine are given, we focused on enhancing the intermolecular acyl donor capacity of the ω-aspartoyl function. It was reasoned that if the need for external base in the Lansbury method could be avoided, competition from aspartimide formation could well be attenuated.12 It was with this view that we began.

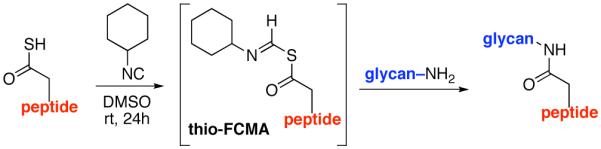

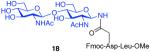

Along these lines, we recently disclosed the development of an efficient, base-free method for the generation of complex amide bonds. Our line of discovery arose from revisitation of long known, but under-appreciated functional groups, i.e. isonitriles.13,14 The presumed mechanism of our amidation reaction starts with addition of a thio acid (1) to an isonitrile (2) thereby generating a thio formimidate-carboxylate mixed anhydride (termed a thio-FCMA i.e. intermediate 3). In the absence of external nucleophile, 3 undergoes 1,3-S→N acyl migration to generate 6 via what we have referred to13 as a two-component coupling (2CC). Alternatively, the intermediate thio-FCMA 3, being a powerful acyl donor, can be intercepted by an external amine nucleophile (cf. 4), thus leading to the formation of amide product (5).15 This reaction proceeds readily at room temperature, thereby providing even quite hindered amides in high yields. Notably, this new amide forming reaction does not require the presence of an added base. It was in this context, that we theorized as to whether this newly developed thio-FCMA amide coupling method could be applied to the challenge of “ω-aspartylation” as required for the synthesis of N-linked glycopeptides (vide supra). More specifically, we envisioned a setting wherein thioacid 1 would represent the aspartate residue of a peptide fragment, and structure 2 would correspond to a “throwaway” isonitrile16 which might otherwise revert to its corresponding thioformamide, 6. Hopefully, in the presence of trapping agent 4, thio-FCMA 3 would be interdicted to produce 5. To reach our objective, wherein 5 corresponds to N-linked glycopeptides, the nucleophile must be the fully deprotected β-anomeric glycosylamine of a suitably complex oligosaccharide.

Results and Discussion

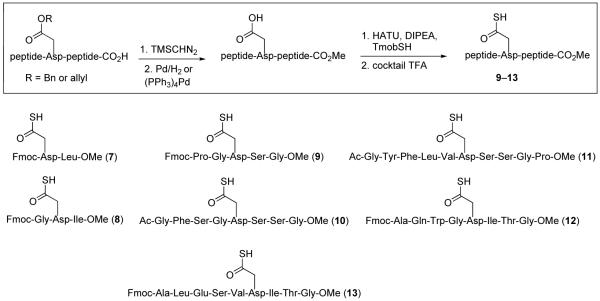

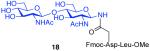

As shown in Figure 3, a range of peptides containing ω-Asp thioacids was prepared for evaluation. The general synthetic procedure for 9–13 is outlined in Figure 3 (thioacids 7 and 8 were prepared from previously described procedures;14b details may be found in the Supporting Information section). The requirement of emplacement of a thioacid function at the ω-aspartyl terminus does not constitute a significant complication to the method. Solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) served well to provide the protected peptide substrates.17a,b Following conversion of the C-terminal carboxylic acids to their methyl ester functions, and subsequent deprotection of the ω-aspartate esters, the ω-aspartyl carboxylate moieties were converted to thioesters. Upon treatment with cocktail TFA18 and purification by RP-HPLC, the ω-aspartyl thioacid peptide substrates (9–13) were in hand. Notably, peptides 9–11 were well suited for a discriminating evaluation since they comprise aspartimide-prone (Asp-Ser) sequences.12

Figure 3.

Thioacid peptides 7–13.

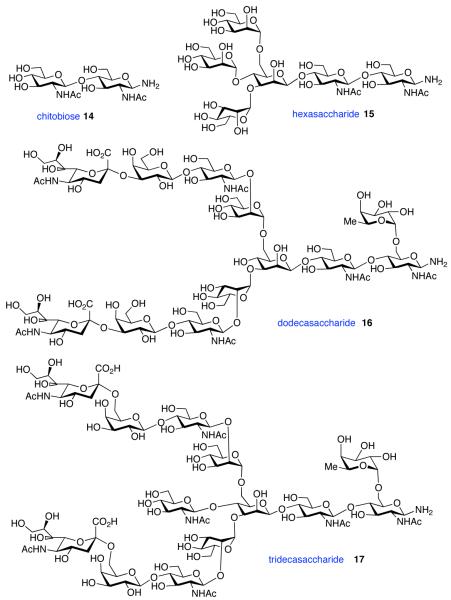

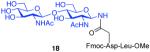

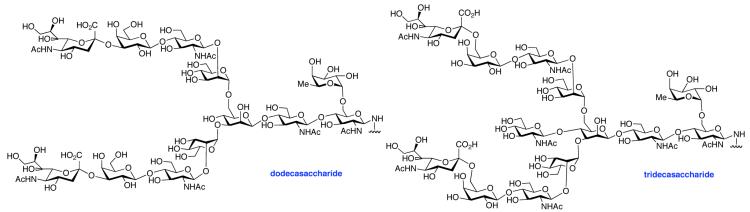

The glycosylamines selected for inclusion in this study are presented in Figure 4; i.e. chitobiose, 14, hexasaccharide 15, dodecasaccharide 16, and the particularly complex tridecasaccharide, 17. The syntheses of these putative γ-aspartyl acceptors have been described.19

Figure 4.

Oligosaccharides 14–17.

With the peptide thioacids and glycosylamine substrates in place, we were in a position to attempt their merger, through a natural ω-asparagine linkage. As shown in Table 1, entry 1, in the presence of cyclohexylisonitrile, dipeptide thioacid 7 and glycosylamine 14 successfully underwent internal base-free aspartylation to afford the glycopeptide adduct in 70% yield, along with low levels of peptide carboxylic acid, aspartimide, and products arising from apparent intramolecular S→N rearrangement of the thio-FCMA (cf. Figure 2, compound 6, where R1 = C-terminal peptide and R3 = cyclohexyl). Attempts to accomplish coupling with more complex peptide and glycosylamine substrates (entries 2-3) required the use of significant excesses of peptide thioacid (3 eq), in order for glycopeptide adducts to be obtained in moderate to good yield. Coupling of thioacid peptide 13 with glycosylamine 15 proceeded in only 19% yield, even when 4 eq of peptide were used (entry 4). Nonetheless, the results shown in Table 1 already seemed to comprise significant progress in the convergent formation of N-linked glycopolypeptides.

Table 1.

Thio-FCMA mediated Aspartylation.a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | peptide + glycan ratio (P:G) |

isonitrile | product | yield |

| 1 |

7 + 14 (1.5:1) |

2.0 eq. |

|

70% |

| 2 |

9 + 14 (3:1) |

5.0 eq. |

|

59% |

| 3 |

9 + 15 (3:1) |

5.0 eq. |

|

80% |

| 4 |

13 + 15 (4:1) |

8.0 eq. |

|

19% |

Key. DMSO, 4Å MS, 2–8 eq. cyclohexyl isonitrile.

Figure 2.

Proposed base-free amide β-asparagine linkage through interception of a thio-FCMA (formimidate carboxylate mixed anhydride) intermediate.

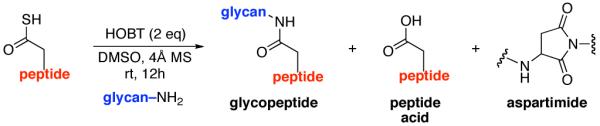

In the light of these encouraging proof of principle findings, we sought to identify improved reaction conditions which would allow for the use of fewer equivalents of peptide thioacid, and would give rise to adducts with higher efficiency (still operating in the mechanistic logic adumbrated in Figure 2). We also hoped to better evaluate the mechanism proposed for the results shown in Tabe 1. It was in this context that we came upon a fortuitous discovery. In conducting a necessary control experiment, which we fully expected to be negative, it was observed that the reaction of peptide 7 and chitobiose 14 reacted to form small amounts of coupled product (~20%) in the absence of cyclohexylisonitrile. At the time, this was unsettling, since the isonitrile had been assumed to be the de-facto activating agent. However, based on analogy with our recent discoveries in the field of classical peptide bond formation,20 we soon postulated that coupling might be proceeding through low levels of an adventitious oxidation agent (air!). Interestingly, when 2 eq. of HOBT21 were added to the reaction, conducted under air, the yields of the glycopeptides were enhanced to as high as 85%, accompanied by small amounts of peptide carboxylic acid and very low levels of aspartimide.

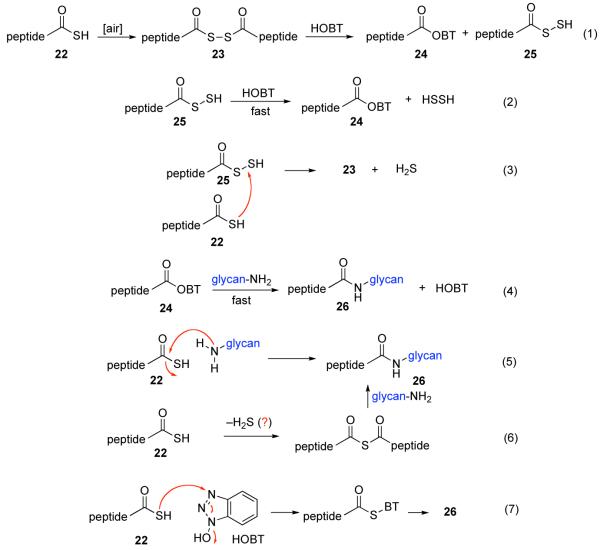

It is well to emphasize that the result of the control experiment does not invalidate the thio-FCMA mechanism proposed above. Indeed, that pathway must be operative at some level, since significant levels of the thioformamide 6 type products are produced when isonitrile 2 was in fact employed. However, there is clearly another, perhaps concurrent, operative pathway which does not involve the isonitrile–mediated thio-FCMA pathway. By analogy to our recent findings resulting in a novel route to peptide ligation,20 we now propose, a mechanistic framework which is not unlike that suggested by Liu and Orgel,22,23 to explain the oxidative acylation of thioacids as a route to the formation of amides under prebiotic conditions, although with two major caveats. First, our chemistry seems to operate via low levels of oxidation (air) and does not require strong oxidizing agents. Moreover, the method works even with the rather weakly nucleophilic and quite labile β-anomeric glycosyl amine even when the glycans are quite complex. As a mechanistic model, it is proposed that perhaps, upon exposure to air, the peptide thioacid (22) suffers low levels of oxidation to afford a strong acyl donor intermediate (Figure 5, eq. 1). For the sake of discussion rather than on the basis of solid proof, we consider a structure of the type 23 in an oxidation-mediated mechanistic format to rationalize our results (vide infra). Conjecturing further, perhaps in the presence of HOBT, 23 reacts to give rise to HOBT ester 24, along with 25. The latter could rapidly react with HOBT, to also yield 24 (eq. 2), which is then activated for coupling with the glycosylamine nucleophile (24→26, eq. 4). Alternatively, 22 can react with 25 to reconstitute 23 (eq. 3) which re-enters the cycle as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Possible mechanisms for HOBT-mediated oxidation.

Several findings support this oxidative mechanistic proposal. Thus, when the reaction is performed under conditions designed to suppress the oxidation, the resulting yields of N-linked glycan are sharply attenuated. Furthermore, even when only one equivalent of peptide thioacid is used, in the presence of air, the glycopeptide product yields are well over 50%, suggesting that oxidized intermediates (perhaps 23) can ultimately give rise to two coupling acyl donors (possibly another molecule of 23) thus allowing the yields to rise to their observed levels.

While the data above, particularly in the context of the earlier experiments, are strongly suggestive that the thioacid (22) undergoes oxidative activation at substoichiometric levels, they do not preclude the possibility of concurrent non-oxidative variations to account for the acyl donor quality of the thioacid. For instance, nothing in our data package convincingly precludes the possibility that a thioacid, such as 22, has some intrinsic acyl donor capacity that can be tapped for non-oxidative amide bond formation (eq. 5). Alternatively, it is possible that two thioacid molecules could give rise to a thio-anhydride, which, of course, can function as an acyl donor (eq. 6). Conceivably, even the per thioacid (25, generated as shown in eq. 1) has inherent acyl donor capacity. Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility that the thioacid reacts with HOBT to produce a thiol-BT acyl donor (eq. 7). Clearly, this cannot be the sole pathway, since the asparagine linkage can be established in the absence of HOBT. The precise delineation of the operative mechanism(s) could well require extensive research. However, the data in hand point to substoichiometric oxidation as an important pathway leading to amide from thioacid and β-anomeric glycosyl amines.

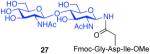

As shown in Table 2, the HOBT-mediated protocol has been extended to an impressive range of complex peptide thioacid and oligosaccharide domains. Thus, the aspartimide-prone peptides, 10 and 11, were successfully merged with chitobiose 14 and hexasaccharide 15 in good yields (entries 4-6, 8). In the coupling of 11 and 15, an excess of peptide (1.5:1) was used, given the complexity of the hexasaccharide component. In this case, a 75% yield of coupled product was obtained, and the excess peptide thioacid had decomposed to carboxylic acid and aspartimide (entry 8). Coupling of peptide 11 with dodecasaccharide 16 gave glycopeptide 33 in 49% yield (entry 9). The aspartylation of peptide 11 with the complex tridecasaccharide 17 proceeded in 39% yield (entry 10). By comparison, aspartylation under standard conditions18 is accomplished in only 20% yield following the use of larger excesses of peptide thioacid acyl donors.

Table 2.

HOBT-mediated Aspartylation

| entry | peptide + glycan ratio (P:G) |

product | yielda |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

7 + 14 (1:2) No HOBT |

|

20% |

| 2 |

7 + 14 (1:1.5) |

|

85%b |

| 3 |

8 + 14 (1:2) |

|

75%c |

| 4 |

10 + 14 (1:2) |

|

52%d |

| 5 |

10 + 15 (1:1) |

|

50%e |

| 6 |

11 + 14 (1:2) |

|

55%f |

| 7 |

12 + 15 (1:1.5) |

|

52%g |

| 8 |

11 + 15 (1.5:1) |

|

75%h |

| 9 |

11 + 16 (1.8:1) |

|

49% |

| 10 |

11 + 17 (1.8:1) |

|

39% |

Isolated yield. The ratio of products was determined by LC-MS of the crude reaction mixture (product:acid:aspartimide)

89:10:1.

82:17:1.

59:37:4.

52:44:2.

60:35:5.

63:34:3.

62:34:4.

Conclusion

In summary, we have uncovered (with the aid of significant happenstance) a highly promising route to accomplish aspartylation of a range of oligosaccharides and peptides, including those of serious levels of complexity. Of course, the ultimate utility of the method will require further testing as to “battle-readiness” in maximally challenging settings. Given the rather formidable targets, now under very active synthetic pursuit in our laboratory (erythropoietin (EPO),24 follicle stimulating hormone (FSH)25 and the glycopeptide recognition element of IgG antibodies),19b there will be no lack of opportunities for such evaluations.

In conclusion, we describe herein the development of a novel, base-free method for the aspartylation of peptides and complex glycans. Under this protocol, the significant problem of peptide aspartimide formation is largely attenuated. Application of this protocol to the synthesis of complex glycoprotein fragments is now underway.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Merger of glycan and peptide domains through aspartylation; undesired base-induced aspartimide formation.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (CA103823 to SJD). We thank Dr. George Sukenick, Ms. Hui Fang, and Ms. Sylvi Rusli of the Sloan-Kettering Institute’s NMR core facility for mass spectral and NMR spectroscopic analysis, and Ms. Rebecca Wilson and Dr. William Berkowitz for valuable discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. General experimental procedures, including spectroscopic and analytical data for new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Bertozzi CR, Kiessling LL. Science. 2001;291:2357. doi: 10.1126/science.1059820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Rudd PM, Elliot T, Cresswell P, Wilson IA, Dwek RA. Science. 2001;291:2370. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Varki A. Glycobiology. 1993;3:97. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).For a recent review, see: Kan C, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:9047. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.09.032.

- (5).For a recent review, see: Gamblin DP, Scanlan EM, Davis BG. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:131. doi: 10.1021/cr078291i.

- (6).(a) Danishefsky SJ, Bilodeau MT. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996;35:1380. [Google Scholar]; (b) Danishefsky SJ, Allen JR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:836. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000303)39:5<836::aid-anie836>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Wan Q, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:9248. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Chen J, Wan Q, Yuan Y, Zhu J, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8521. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen J, Wang P, Zhu J, Wan Q, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;66:2277. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.01.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Tan Z, Shang S, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:9500. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).For a highly creative simulation of asparagine linkages, see: Rabuka D, Forstner MB, Groves JT, Bettozzi CR. J. Am. Soc. Chem. 2008;130:5947. doi: 10.1021/ja710644g.

- (11).Cohen-Anisfeld ST, Lansbury PT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:10531. Anisfeld ST, Lansbury PT. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:5560. For an excellent catalog of other aspartylation methods, see reference 5.

- (12).(a) Bodanszky M, Natarajan S. J. Org. Chem. 1975;40:2495. doi: 10.1021/jo00905a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bodanszky M, Kwei JZ. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1978;12:69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tam JP, Riemen MW, Merrifield RB. Pept. Res. 1988;1:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Li X, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5446. doi: 10.1021/ja800612r. Li X, Yuan Y, Kan C, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13225. doi: 10.1021/ja804709s. and references to the original isonitrile literature therein.

- (14).(a) Wu X, Li X, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1523. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yuan Y, Zhu J, Li X, Wu X, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:2329. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.02.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wu X, Stockdill JL, Wang P, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4098. doi: 10.1021/ja100517v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Rao Y, Li X, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12924. doi: 10.1021/ja906005j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Of course, the resultant thio-formamide could be recycled to the amine precursor of the isonitrile at the manufacture level. (b) We also note that through the use of hindered isonitriles, the S→N rearrangement can be suppressed to the point where it is negligible.

- (17).(a) Merrifield RB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:2149. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lloyd-Williams P, Albericio F, Giralt E. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:11065. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sole NA, Barany G. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:5399. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Wu B, Hua Z, Warren JD, Ranganathan K, Wan Q, Chen G, Tan Z, Chen J, Endo A, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:5577. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.09.045. Wang P, Zhu J, Yuan Y, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16669. doi: 10.1021/ja907136d. For the synthesis of hexasaccharide 15, see Supporting Information.

- (20).Wang P, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17045. doi: 10.1021/ja1084628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).König W, Geiger R. Chem. Ber. 1970;103:788. doi: 10.1002/cber.19701030319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Liu R, Orgel LE. Nature. 1997;389:52. doi: 10.1038/37944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).An earlier perception of the oxidative possibility, also in a stoichiometric sense, appeared in 1952. See: Sheehan JC, Johnson DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952;74:4726.

- (24).(a) Tan Z, Shang S, Halkina T, Yuan Y, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5424. doi: 10.1021/ja808704m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yuan Y, Chen J, Wan Q, Tan Z, Chen G, Kan C, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5432. doi: 10.1021/ja808705v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kan C, Trzupek JD, Wu B, Wan Q, Chen G, Tan Z, Yuan Y, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5438. doi: 10.1021/ja808707w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Nagorny P, Fasching B, Li X, Chen G, Aussedat B, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5792. doi: 10.1021/ja809554x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.