Abstract

A2A adenosine receptors are considered an excellent target for drug development in several neurological and psychiatric disorders. It is noteworthy that the responses evoked by A2A adenosine receptors are regulated by D2 dopamine receptor ligands. These two receptors are co-expressed at the level of the basal ganglia and interact to form functional heterodimers. In this context, possible changes in A2A adenosine receptor functional responses caused by the chronic blockade/activation of D2 dopamine receptors should be considered to optimise the therapeutic effectiveness of dopaminergic agents and to reduce any possible side effects. In the present paper, we investigated the regulation of A2A adenosine receptors induced by antipsychotic drugs, commonly acting as D2 dopamine receptor antagonists, in a cellular model co-expressing both A2A and D2 receptors. Our data suggest that the treatment of cells with the classical antipsychotic haloperidol increased both the affinity and responsiveness of the A2A receptor and also affected the degree of A2A–D2 receptor heterodimerisation. In contrast, an atypical antipsychotic, clozapine, had no effect on A2A adenosine receptor parameters, suggesting that the two classes of drugs have different effects on adenosine–dopamine receptor interaction. Modifications to A2A adenosine receptors may play a significant role in determining cerebral adenosine effects during the chronic administration of antipsychotics in psychiatric diseases and may account for the efficacy of A2A adenosine receptor ligands in pathologies associated with dopaminergic system dysfunction.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11302-010-9201-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: A2A adenosine receptors, D2 dopamine receptor antagonists, A2A binding parameters, Receptor functioning, Receptor crosstalk

Introduction

The endogenous neuromodulator adenosine controls and integrates a wide range of brain functions [1] and is involved in the etiopathogenesis of several pathologies ranging from epilepsy to neurodegenerative disorders and psychiatric conditions. The adenosine system has thus been recognised as a prime target for the development of new therapeutics to treat these diseases.

From epidemiological to animal studies, it is clear that extracellular adenosine acting at adenosine receptors (ARs) influences the functional outcome of a broad spectrum of brain injuries. In the brain, A2AARs are mainly expressed at the level of neurons, glial cells [2–7] and peripheral inflammatory cells, playing a role in both neuroprotection and neurodegeneration [8–10]. The alterations in A2AAR density and functional responsiveness that occurred during pathological conditions (i.e. neurological and psychiatric diseases) represent a crucial aspect in the balance between the protective and toxic effects exerted by this receptor subtype at the central level. Using a rat model of focal ischaemia, it has been demonstrated that increases in A2AAR density may contribute to A2AAR-mediated neuron death [11]. In addition, an increase in A2AAR density and/or functionality has also been detected in psychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia [12] and bipolar disorders [13]: in these pathologies, alterations in A2AAR parameters have been related to the chronic use of antipsychotic drugs, D2 dopamine receptor (DR) antagonists [14–16], and also the functional crosstalk between the adenosine and dopamine systems.

In recent years, it has been indicated that adenosine and dopamine interact functionally in the brain and that this structural association may have pathophysiological and therapeutic implications [17–19]. In the corpus striatum and mesolimbic areas, where the two receptors mostly co-localise [20], it has been demonstrated that they are structurally associated to form functional heterodimers in which the adenosine and dopamine receptors mutually antagonise their respective responses [21–25]. On the basis of these results, A2AAR agonists have been suggested as possible drugs, in association with antipsychotics, for the treatment of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia and bipolar disorders [26, 27].

Investigation of the molecular mechanisms involved in the crosstalk between A2AARs and D2DRs and the effects of antipsychotic drugs on A2AAR modulation may represent a crucial starting point to (1) clarify the role of the adenosine system in several psychiatric disorders; (2) optimise antipsychotic therapy; and (3) reduce the possible side effects inherent in hyperactivity of the adenosine system induced by the chronic administration of antipsychotic drugs, such as extrapyramidal symptoms.

For this purpose, we established a cellular model in which these receptors are stably co-expressed at high levels, and we investigated the effects of D2DR antagonists (haloperidol and clozapine) on A2AAR binding parameters and functional responsiveness. The availability of this cellular model allowed us to overcome the problem of recovering biological samples from patients in quantities sufficient for biochemical analysis.

Materials and methods

Calcium phosphate transfection of D2L receptor in CHO cells

Cell lines co-expressing A2AARs and D2DRs were obtained by calcium phosphate transfection. A solution of 100 μl of 2.5 M CaCl2 and 10 μg of plasmid pcDNA3.1/Hygro(+) containing human D2L (long-form) DR was diluted 1/10 in TE buffer (1 mM Tris–HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.6) to a final volume of 500 μl. One volume of this 2x CaH/DNA solution was added quickly to an equal volume of 2X HEPES solution (140 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM Na2HPO4, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.05 at 23°C). The two solutions were mixed quickly and added dropwise to Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably transfected with A2AAR [28]. After 1 day, the plates were washed twice with NaCl 0.9% and new medium without antibiotics was added. The following day, 0.5 mg/ml Hygromycin was added to the media to initiate selection for stably transfected cells. Selection continued with periodic treatment of cells with different concentrations of antibiotic to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/ml.

Cell culture

CHO cells stably transfected with human A2AARs and D2LDRs were grown adherently and were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with nutrient mixture F12 (DMEM/F12) containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (200 U/ml), streptomycin (200 μg/ml), and l-glutamine (4 mM) at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

Cell treatments

CHO cells co-transfected with A2AARs and D2DRs were plated using complete media supplemented with 0.2 mg/ml Hygromycin and 0.2 mg/ml Geneticin (G418) in order to maintain selection pressure for D2DR and A2AAR, respectively. After 48 h, cells were treated for 1–24 h with 1 nM–10 μM of the antipsychotic haloperidol or clozapine under serum-deprived conditions using DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1% FBS. At the end of the treatments, membrane fractions were prepared and protein concentrations were detected according to the Bio-Rad method [29] using bovine albumin as a reference standard. Control and treated cells were used for A2AAR binding and functional assays.

D2DR binding assay

Cells were washed twice with a 0.9% NaCl solution, detached with hypotonic buffer (1 mM HEPES, 2 mM EDTA) and incubated for 10 min at 4°C. The suspension was homogenised and centrifuged at 48,000×g for 20 min at 4°C. The pellet was then suspended in binding buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 155 mM NaCl, pH 7.4).

D2DR saturation binding assays were performed by incubating aliquots of CHO cell membranes (30 μg) in 1 ml of binding buffer supplemented with 1.5 mM ascorbic acid in the presence of increasing D2DR antagonist, cis-N-(1-benzyl-2-methylpyrrolidine-3-yl)-5-chloro-2-methoxy-4-methylaminobenzamide ([3H]YM 09151-2) concentrations. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 1.5 mM dopamine. The cells were incubated for 1 h at 30°C, and the binding reaction was terminated by rapid filtration under vacuum through Whatman GF/C glass fibre filters (Millipore Corporation) pretreated with 0.6% polyethylenimine. The filters were washed three times with 4 ml of filtration buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 155 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and then counted in 4 ml of scintillation cocktail.

A2AAR binding assay

Cells were washed twice with cold PBS (9.1 mM NaH2PO4, 1.7 mM Na2HPO4, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and detached with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). Cells were harvested, homogenised and centrifuged at 48,000×g for 20 min at 4°C before the pellet was suspended in binding buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4).

Competitive binding assays (cold analysis) were performed by incubating 30 μg of CHO membranes with 2 U/ml adenosine deaminase (ADA) in 0.5 ml of binding buffer containing 10 nM of the AR agonist [3H]5′-N-ethylcarboxamide adenosine (NECA) and increasing concentrations of unlabeled NECA (0.1 nM–1 μM). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 100 μM N6-[(R)-1-methyl-2-phenyl-ethyl]adenosine. Cells were incubated for 3 h at 25°C, and the binding reaction was terminated by rapid filtration under vacuum through Whatman GF/C glass fibre filters (Millipore Corporation). Filters were washed three times with 4 ml of binding buffer and counted in 4 ml of scintillation cocktail.

A2AAR and D2DR immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

CHO cells, treated without (control) or with 1 μM haloperidol or 1 μM clozapine for 24 h, were lysed for 60 min at 4°C by the addition of 200 μl RIPA buffer (9.1 mM NaH2PO4, 1.7 mM Na2HPO4, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, and 0.1% SDS, protease inhibitor cocktail).

Extracts were then equalised by protein assay, and A2AARs and D2DRs were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates using A2AAR (Alpha Diagnostic cat no. A2AR12-A) or D2DR (Alpha Diagnostic cat no. D2R12-A) antibodies, respectively. Cell lysates (1 mg) were pre-cleared with protein A Sepharose (1 h at 4°C) to precipitate and eliminate IgG. Samples were then centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C (14,000×g); the supernatants were incubated with anti-A2AAR or anti-D2DR receptor antibody (3 μg/sample) overnight at 4°C under constant rotation and then immunoprecipitated with protein A Sepharose (2 h at 4°C). Immunocomplexes, after being washed, were resuspended in Laemmli solution and boiled for 5 min and were then resolved by SDS-PAGE (10%), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed overnight at 4°C with primary antibody anti-A2AAR (1:500). Membranes, after incubation with the secondary antibody, were developed using Millipore chemioluminescent reagents. The specificity of A2AAR immunoreactive bands were evaluated using wild-type CHO cells as a negative control.

AC activity at A2AAR

Cells were washed twice with cold PBS and detached with ice-cold hypotonic buffer (5 mM Tris, 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). The cell suspension was homogenised on ice (Ultra-Turrax, 2 × 15 s at full speed) and the homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000×g at 4°C. The supernatant was then centrifuged for 45 min at 100,000×g, and the membrane pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.4, and immediately used in functional assays.

The potency of the agonist NECA against A2AAR was determined by assessing the ability of increasing agonist concentrations to stimulate cAMP accumulation. The procedure was carried out as previously described [30], with minor modifications. A total volume of 100 μl of incubation medium contained 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, approximately 200,000 cpm of [α-32P]ATP, 100 μM unlabeled ATP, 10 μM GTP, 100 μM cyclic AMP, 1 mM MgCl2, 500 μM Ro 20-1724, 0.4 mg/ml creatine kinase, 5 mM creatine phosphate, 2 mg/ml bovine serum albumin and 0.2 U/ml ADA.

Data analysis

For data analysis and graphic presentation, the nonlinear multipurpose curve fitting computer programme Graph-Pad Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) was used. For saturation and competition binding studies, Scatchard analysis was performed, whilst sigmoidal dose–response curve fitting was used for functional data. Statistical analyses of binding and functional data (expressed as means ± SEM) were performed using Student’s t test. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

A2AAR and D2DR equilibrium binding parameters in CHO cells

A2AAR and D2DR equilibrium binding parameters were evaluated in CHO cells expressing only a single or both receptor subtypes. The results obtained by Scatchard analysis of saturation (for D2DRs) and competition (for A2AARs) binding data are reported in Table 1. A representative Scatchard plot of binding data is also shown in Electronic supplementary material (ESM) Fig. 1. The results demonstrated that co-expression of both A2AARs and D2DRs induced significant changes in receptor binding parameters in terms of Bmax and/or Kd values.

Table 1.

[3H]NECA (for A2AAR) and [3H]YM 09151-2 (for D2DR) equilibrium binding parameters in transfected CHO cells

| [3H]YM09151-2 | [3H]NECA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHO D2 | CHO A2/D2 | CHO A2A | CHO A2/D2 | |

| Kd (nM) | 0,049 ± 0,01 | 0.060 ± 0.01 | 12.91 ± 1.10 | 26.2 ± 1.34** |

| Bmax (fmol/mg) | 841 ± 87.1 | 1600 ± 173* | 2712 ± 184 | 9740 ± 1210** |

*P < 0.01; **P < 0.001

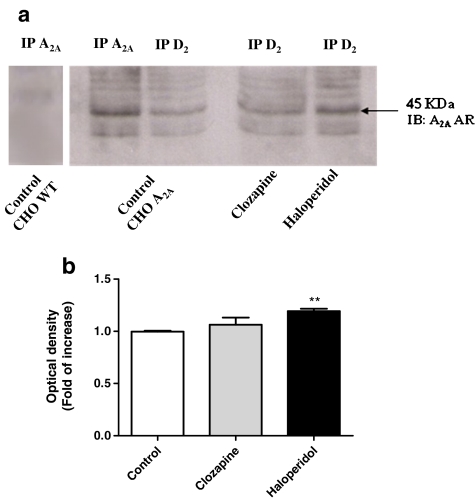

Co-immunoprecipitation of A2AARs and D2DRs in CHO cells

The presence of a structural interaction between A2AARs and D2DRs in co-transfected CHO cells was evaluated by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting assay. CHO cells treated with 1 μM haloperidol or 1 μM clozapine for 24 h and the respective controls were immunoprecipitated using an anti-D2DR and then immunoblotted with an A2AAR antibody. In parallel, lysates from control cells were also immunoprecipitated using A2AAR antibody and immunoblotted with the same antibody. In A2AAR immunoprecipitates obtained from control cells, the anti-A2A AR antibody recognised a 45-kDa protein corresponding to the A2AAR subtype [31]. In parallel, no significant labelling was detected in wild-type CHO cells not expressing the A2AAR subtype, demonstrating the specificity of antibody immunoreactivity. The A2AAR immunoblotting performed on immunoprecipitated D2DR from control cells revealed the same major band of approximately 45 kDa corresponding to A2AAR (Fig. 1a), demonstrating that A2AARs co-immunoprecipitated with D2DRs and suggesting that these receptors form a heteromeric complex. Cell treatment with haloperidol caused a significant increase in immunoprecipitated A2A AR, as demonstrated by the densitometric analysis of the A2AAR immunoreactive band (1.19 ± 0.02 increase in optical density vs. control, set to 1, P < 0.01; Fig. 1b). In contrast, no significant change in the levels of immunoprecipitated A2AAR was detected following cell treatment with clozapine. These results suggest that only the classical drug affected the heteromeric association between A2AARs and D2DRs, increasing the levels of co-immunoprecipitated A2AARs–D2DRs.

Fig. 1.

Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblotting (IB) of A2AAR. CHO cells were treated with medium alone (control) or with 1 μM haloperidol or 1 μM clozapine for 24 h. One milligram of protein was immunoprecipitated using a polyclonal antibody against D2DR and resolved by SDS electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and A2AAR IB was performed using a polyclonal antibody against A2AAR. In control A2AAR-transfected cells, but not in wild-type cells, A2AARs were detected following immunoprecipitation with the A2A AR antibody. Immunoreactive proteins were visualised by chemioluminescence (a). Densitometric analysis of A2A AR immunoreactive bands (b)

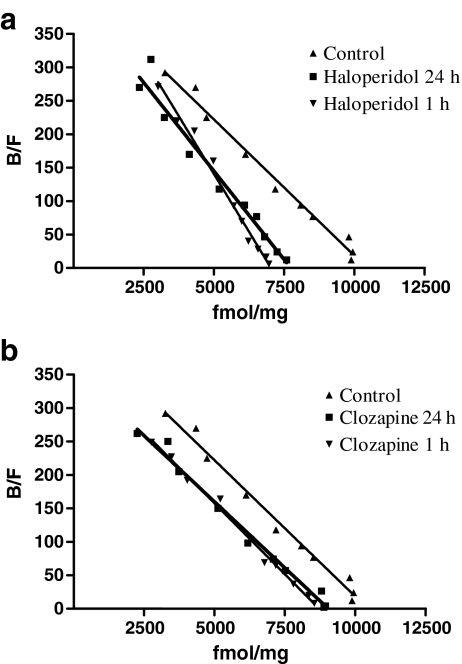

Effect of antipsychotic drugs on A2AAR equilibrium binding parameters

Because antipsychotic cell treatments were performed under serum deprivation, we first evaluated the effect of 24-h exposure to low serum levels (1% FBS) on A2AAR binding. A2AAR Scatchard analysis showed [3H]NECA Kd values of 26.2 ± 1.34 nM and a Bmax of 9,740 ± 1,210 fmol/mg of proteins (Fig. 3a). These values were not significantly different from those obtained in control cells (10% serum, P > 0.05), suggesting that serum limitation did not affect A2A AR binding parameters in CHO cells.

Fig. 3.

Effect of antipsychotic treatment on [3H] NECA binding parameters of A2AAR. CHO cells were treated for 1–24 h with medium alone (a), 1 μM haloperidol (b) or 1 μM clozapine (c), and then [3H]NECA competitive binding experiments were performed. Graphs show a representative Scatchard plot of [3H] NECA competitive binding data obtained from three experiments yielding similar results

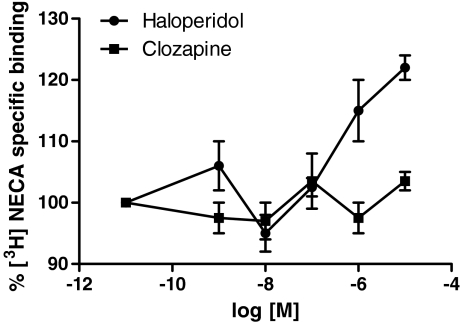

Cells were treated for 24 h with the classical and atypical antipsychotics haloperidol and clozapine at different concentrations (ranging from 1 nM to 10 μM), and then [3H]NECA-specific binding to A2AARs was evaluated. The results (Fig. 2) showed that haloperidol, but not clozapine, was able to significantly increase [3H]NECA binding when used at high concentrations of 1 and 10 μM. A2A AR binding parameters were evaluated following treatment with haloperidol and clozapine for short (1 h) and long time periods (24 h). Treatment of cells with haloperidol for 1 and 24 h induced a significant increase in [3H]NECA affinity for A2AAR (Kd: 1 h, 15 ± 1.41 nM; 24 h, 18.1 ± 1.36 nM, P < 0.01 vs. control cells) without significant changes in A2AAR density (Bmax: 1 h, 7,100 ± 720 fmol/mg proteins; 24 h, 6,640 ± 1,580 fmol/mg of proteins, P > 0.05 vs. control cells; Fig. 3a). Treatment with 1 μM clozapine (Fig. 3b) for either 1 or 24 h did not change the affinity or density of A2AAR compared to controls (Kd: 1 h, 24.3 ± 1.45 nM; 24 h, 27.7 ± 0.68 nM, P > 0.05 vs. control cells; Bmax: 1 h, 8,720 ± 635 fmol/mg proteins; 24 h, 8,460 ± 1,190 fmol/mg proteins, P > 0.05 vs. control cells).

Fig. 2.

Effect of different haloperidol or clozapine concentrations on [3H] NECA-specific binding of A2AAR. CHO cells were treated for 24 h with medium alone or haloperidol or clozapine (1 nM–10 μM) and then [3H]NECA binding assays were performed. Data are expressed as the percentage of [3H]NECA-specific binding with respect to untreated control cells (100%) and represent the mean ± SEM of three different experiments

In addition, we evaluated the levels of D2DR following treatment with the antipsychotics by means of radioligand binding. We demonstrated that following treatment with 1 μM haloperidol for 24 h, 59% of the receptors were labelled with respect to untreated control cells (specific binding, 198.1 vs. 334.9 fmol/mg proteins, P < 0.001). In contrast, when the cells were treated with 1 μM clozapine, no significant change in D2 DR-specific binding was detected (378.2 fmol/mg proteins, P > 0.05 vs. control cells), suggesting that following 24-h treatment with this drug, D2DRs were not affected.

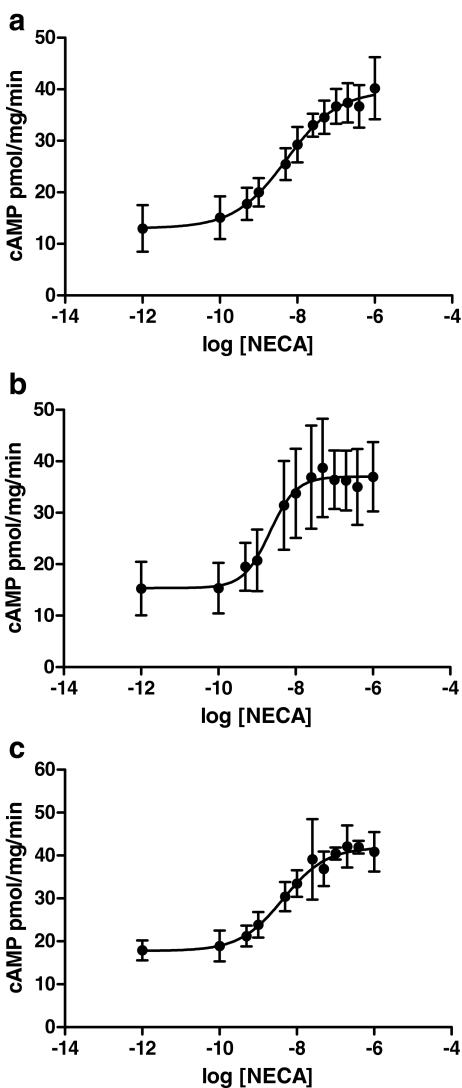

Effect of antipsychotic drugs on A2AAR functional responsiveness

The effect of treatment with the antipsychotics for 24 h on A2AAR functional responsiveness was evaluated by assessing NECA-stimulated activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC). In control cells, NECA activated AC with an EC50 value of 5.09 ± 0.67 nM (Fig. 4a). After treatment with 1 μM haloperidol (Fig. 4b), a significant increase in A2AAR responsiveness compared to the control was observed (haloperidol: EC50 = 3.64 ± 0.57 nM, P < 0.01 vs. control cells). Cells treated with 1 μM clozapine (Fig. 4c) did not show any significant change in NECA-mediated AC activation (clozapine: EC50 = 4.82 ± 1.26 nM, P > 0.05 vs. control cells). The maximal efficacy of the agonist NECA to stimulate cAMP accumulation was not affected following treatment with both tested antipsychotic compounds (maximal effect: P > 0.05 vs. control cells).

Fig. 4.

Effect of antipsychotic treatment on A2AAR functional responsiveness. CHO cells were treated for 24 h with medium alone (a), with 1 μM haloperidol (b) or with 1 μM clozapine (c), and then the ability of different NECA concentrations to stimulate cAMP accumulation was evaluated. Data are expressed as picomoles per milligram proteins per minute and represent the mean ± SEM of four different experiments

Discussion

For the first time, we have demonstrated that the classical antipsychotic haloperidol affected A2AAR-mediated responses in CHO cells co-expressing high levels of A2AARs and D2DRs. In particular, haloperidol favoured the structural interaction between A2A–D2 receptors, causing an increase in A2AAR binding affinity and functional responsiveness.

These results suggest that during chronic treatment with classical antipsychotic drugs, A2AAR underwent subtle regulatory changes affecting its receptor binding properties and functional responsiveness. These receptor changes represent a crucial aspect in further clarifying the pathophysiological role of adenosine in psychiatric diseases and should be taken into account (1) in developing new drugs as well as (2) in preventing possible side effects of drugs indirectly modulating the adenosine system. In our specific context, the underlying regulation of A2AAR during antipsychotic administration represents an important target for the optimisation of pharmacological therapy in pathologies associated with psychotic symptoms.

To investigate this issue, we developed a CHO cell line that stably co-expressed both A2A and D2 receptors at high levels. In this clone, a monomeric form of A2AAR [32] was detected both in A2AAR and D2DR immunoprecipitates, suggesting that A2AAR and D2DR aggregate to form a heteromeric complex in basal conditions. The treatment with haloperidol caused an increase in immunoprecipitated A2AAR, suggesting that blocking D2DR favours the structural A2/D2 receptor interaction. These data are in accordance with Vidi et al. [25] who demonstrated the ligand-dependent heterodimerisation of D2 and A2A receptors in living neuronal cells. In particular, they have demonstrated that the formation of A2A/D2 heteromers is increased in living neuronal cells following treatment with sulpiride, a D2DR antagonist, for 18 h. In addition, we were not able to detect any significant changes in the levels of A2A–D2 receptor interaction following treatment with clozapine, suggesting that the two classes of drugs regulate the structural interaction of the two receptor proteins differently at the membrane level.

We then investigated the effects of short- and long-term cell treatment with classical and atypical antipsychotics on A2AAR binding parameters and functional responsiveness. The co-expression of A2AARs and D2DRs in the same cells induced a significant increase in [3H]NECA Kd and Bmax values, suggesting that A2AAR are modulated by the presence of D2DR at the level of the plasma membrane in the absence of D2DR receptor ligands. When the cells were treated with haloperidol for 1 or 24 h, a significant increase in A2A agonist affinity was detected without any changes in receptor density. A significant increase in A2AAR functional responsiveness was also observed. In a previous report [13], we demonstrated that in platelets of human patients with bipolar disorders, chronic administration of classical antipsychotics induced an increase in A2AAR affinity and responsiveness associated with receptor up-regulation. The difference in the regulation of A2AAR density induced by haloperidol in platelets and in transfected cells could be ascribed to the in vivo and in vitro experimental conditions; in fact, the treatment of CHO cells with the drug for 24 h is probably not representative of chronic treatment in patients.

In parallel, we demonstrated that the atypical antipsychotic clozapine did not have any effect on A2AAR binding and functional parameters. Despite their common therapeutic usage, the differences in A2AAR regulation induced by these two classes of antipsychotics confirmed that these drugs have different mechanisms of action at the molecular level. Indeed, a crucial point that distinguishes antipsychotics is the degree of dopamine D2DR occupancy and the kinetics of drug–receptor dissociation, on which the drug response and some unpleasant side effects depend. Classical antipsychotics, such as haloperidol, have high D2DR occupancy and slow dissociation rates compared to atypical antipsychotics [33]; occupancy increases above 80% and is connected with increased extrapyramidal side effects, elevation of prolactin levels [34, 35] and dyskinesias. Clozapine, an atypical drug, shows a much lower occupancy (16%–68%) and a fast dissociation rate; this may explain its lack of extrapyramidal side effects and prolactin elevation [36, 37]. These differences in D2DR occupancy were confirmed in our experimental conditions. In fact, we showed that following treatment with haloperidol for 24 h and the subsequent washing of the cells, only 59% of D2DR binding sites are labelled by the D2DR antagonist [3H]YM 09151-2. These results could be explained by supposing that (1) the drug remained bound to the receptor, causing receptor occupancy of about 41%, and (2) the long time block of D2DR by the antagonist, haloperidol, caused receptor down-regulation. Only in “in vivo” experiments has it been demonstrated that the chronic administration of haloperidol to rats for 14 days or 8 months induced dysregulation of D2DR expression levels in different brain regions [38, 39]. Otherwise, in striatal and astroglial cell cultures, treatment with antipsychotics for 12 h is not enough to induce changes in D2DR expression levels [40]. These data lead us to speculate that the effects of 24-h haloperidol treatment on D2DR binding in CHO cells are presumably due to receptor occupation rather than to receptor down-regulation.

Clozapine is completely removed from D2DR binding sites and did not affect D2DR-specific binding, probably as a consequence of its rapid dissociation constant. These differences in D2 receptor occupancy may be at the root of specific effects observed in A2AAR regulatory mechanisms, and it is possible to speculate that the degree of D2DR occupancy is important in the regulation of A2AAR responses. This hypothesis might also be supported by data obtained in immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrating that only haloperidol, but not clozapine, was able to increase A2A/D2 heteromeric association. Further studies are in progress to investigate the role of this heteromeric association in the control of A2A receptor responsiveness induced by antipsychotics.

The main conclusion of this study is that blockade of D2DRs induced changes in A2AAR responses, confirming the existence of functional crosstalk between the adenosine and dopamine systems. As a consequence, the hyperresponsiveness of A2AARs, induced by haloperidol treatment, could justify the proposed use of A2AAR agonists in association with classical antipsychotic therapy [17, 26, 27, 41, 42] in several psychiatric diseases associated with a dopamine system hyperactivity.

On the other hand, one should not forget the neurodegererative and toxic effects that A2AARs exert at the central level [43–49]. In this context, A2AAR hyperactivity may have important pathophysiological implications and might contribute to, induce or exacerbate neurodegenerative effects in several psychiatric diseases. In this scenario, the choice of the antipsychotic, and particularly its dosage, should always follow an investigation of the individual’s proneness to other diseases.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Scatchard plot of [3H]YM09151-2 (D2DRs) (a) and [3H]NECA (A2AARs) (b) binding data performed in CHO cells co-expressing both D2DRs and A2AARs. Graphs show a representative Scatchard plot from saturation (a) and competition (b) binding studies performed three times with similar results (PPT 144 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant funded by Monte dei Paschi di Siena Foundation.

Footnotes

M. Letizia Trincavelli and S. Cuboni equally contributed to the study.

References

- 1.Boison D. Adenosine as a modulator of brain activity. Drug News Perspect. 2007;20:607–611. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2007.20.10.1181353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiebich BL, Biber K, Lieb K, Calker D, Berger M, Bauer J, Gebicke-Haerter PJ. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in rat microglia is induced by adenosine A2a-receptors. Glia. 1996;18:152–160. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199610)18:2<152::AID-GLIA7>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterfreund RA, MacCollin M, Gusella J, Fink JS. Characterization and expression of the human A2a adenosine receptor gene. J Neurochem. 1996;66:362–368. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brodie C, Blumberg PM, Jacobson KA. Activation of the A2A adenosine receptor inhibits nitric oxide production in glial cells. FEBS Lett. 1998;429:139–142. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00556-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svenningsson P, Moine C, Fisone G, Fredholm BB. Distribution, biochemistry and function of striatal adenosine A2A receptors. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;59:355–396. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(99)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hettinger BD, Lee A, Linden J, Rosin DL. Ultrastructural localization of adenosine A2A receptors suggests multiple cellular sites for modulation of GABAergic neurons in rat striatum. J Comp Neurol. 2001;431:331–346. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010312)431:3<331::AID-CNE1074>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu L, Frith MC, Suzuki Y, Peterfreund RA, Gearan T, Sugano S, Schwarzschild MA, Weng Z, Fink JS, Chen JF. Characterization of genomic organization of the adenosine A(2A) receptor gene by molecular and bioinformatics analyses. Brain Res. 2004;1000:156–173. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JF, Pedata F. Modulation of ischemic brain injury and neuroinflammation by adenosine A2A receptors. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:1490–1499. doi: 10.2174/138161208784480126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haskó G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:759–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayne M, Fotheringham J, Yan HJ, Power C, Bigio MR, Peeling J, Geiger JD. Adenosine A2A receptor activation reduces proinflammatory events and decreases cell death following intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:727–735. doi: 10.1002/ana.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trincavelli ML, Melani A, Guidi S, Cuboni S, Cipriani S, Pedata F, Martini C. Regulation of A(2A) adenosine receptor expression and functioning following permanent focal ischemia in rat brain. J Neurochem. 2008;104:479–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deckert J, Brenner M, Durany N, Zöchling R, Paulus W, Ransmayr G, Tatschner T, Danielczyk W, Jellinger K, Riederer P. Up-regulation of striatal adenosine A(2A) receptors in schizophrenia. NeuroReport. 2003;14:313–316. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200303030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martini C, Tuscano D, Trincavelli ML, Cerrai E, Bianchi M, Ciapparelli A, Lucioni A, Novelli L, Catena M, Lucacchini A, Cassano GB, Dell’Osso L. Upregulation of A2A adenosine receptors in platelets from patients affected by bipolar disorders under treatment with classical antipsychotics. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldessarini RJ. Treatment research in bipolar disorder: issues and recommendations. CNS Drugs. 2002;16:721–729. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216110-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brambilla P, Barale F, Soares JC. Atypical antipsychotics and mood stabilization in bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology. 2003;166:315–332. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sundram S, Joyce PR, Kennedy MA. Schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder: perspectives for the development of therapeutics. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3:393–407. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferré S, O’Connor WT, Snaprud P, Ungerstedt U, Fuxe K. Antagonistic interaction between adenosine A2A receptors and dopamine D2 receptors in the ventral striopallidal system. Implications for the treatment of schizophrenia. Neurosci. 1994;63:765–773. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90521-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferré S, Quiroz C, Woods AS, Cunha R, Popoli P, Ciruela F, Lluis C, Franco R, Azdad K, Schiffmann SN. An update on adenosine A2A–dopamine D2 receptor interactions: implications for the function of G protein-coupled receptors. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:1468–1474. doi: 10.2174/138161208784480108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azdad K, Gall D, Woods AS, Ledent C, Ferré S, Schiffmann SN. Dopamine D2 and adenosine A2A receptors regulate NMDA-mediated excitation in accumbens neurons through A2A–D2 receptor heteromerization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:972–986. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fink JS, Weaver DR, Rivkees SA, Peterfreund RA, Pollack AE, Adler EM, Reppert SM. Molecular cloning of the rat A2 adenosine receptor: selective co-expression with D2 dopamine receptors in rat striatum. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1992;14:186–195. doi: 10.1016/0169-328X(92)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canals M, Marcellino D, Fanelli F, Ciruela F, Benedetti P, Goldberg SR, Neve K, Fuxe K, Agnati LF, Woods AS, Ferré S, Lluis C, Bouvier M, Franco R. Adenosine A2A-dopamine D2 receptor–receptor heteromerization: qualitative and quantitative assessment by fluorescence and bioluminescence energy transfer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46741–46749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuxe K, Ferré S, Canals M, Torvinen M, Terasmaa A, Marcellino D, Goldberg SR, Staines W, Jacobsen KX, Lluis C, Woods AS, Agnati LF, Franco R. Adenosine A2A and dopamine D2 heteromeric receptor complexes and their function. J Mol Neurosci. 2005;26:209–220. doi: 10.1385/JMN:26:2-3:209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai SJ. Adenosine A2a receptor/dopamine D2 receptor hetero-oligomerization: a hypothesis that may explain behavioral sensitization to psychostimulants and schizophrenia. Med Hypotheses. 2005;64:197–200. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navarro G, Carriba P, Gandía J, Ciruela F, Casadó V, Cortés A, Mallol J, Canela EI, Lluis C, Franco R. Detection of heteromers formed by cannabinoid CB1, dopamine D2, and adenosine A2A G-protein-coupled receptors by combining bimolecular fluorescence complementation and bioluminescence energy transfer. Scientific World Journal. 2008;8:1088–1097. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vidi PA, Chemel BR, Hu CD, Watts VJ. Ligand-dependent oligomerization of dopamine D(2) and adenosine A(2A) receptors in living neuronal cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:544–751. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.047472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dixon DA, Fenix LA, Kim DM, Raffa RB. Indirect modulation of dopamine D2 receptors as potential pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia: I. Adenosine agonists. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:480–488. doi: 10.1345/aph.18215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wardas J. Potential role of adenosine A2A receptors in the treatment of schizophrenia. Front Biosci. 2008;13:4071–4096. doi: 10.2741/2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klotz KN, Hessling J, Hegler J, Owman C, Kull B, Fredholm BB, Lohse MJ. Comparative pharmacology of human adenosine receptor subtypes—characterization of stably transfected receptors in CHO cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1998;357:1–9. doi: 10.1007/PL00005131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klotz KN, Cristalli G, Grifantini M, Vittori S, Lohse MJ. Photoaffinity labeling of A1-adenosine receptors. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:14659–14664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albasanz JL, Rodríguez A, Ferrer I, Martín M. Adenosine A2A receptors are up-regulated in Pick’s disease frontal cortex. Brain Pathol. 2006;16:249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2006.00026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hillion J, Canals M, Torvinen M, Casado V, Scott R, Terasmaa A, Hansson A, Watson S, Olah ME, Mallol J, Canela EI, Zoli M, Agnati LF, Ibanez CF, Lluis C, Franco R, Ferre S, Fuxe K. Coaggregation, cointernalization, and codesensitization of adenosine A2A receptors and dopamine D2 receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18091–18097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kapur S, Seeman P. Does fast dissociation from the dopamine D(2) receptor explain the action of atypical antipsychotics? A new hypothesis. Am J Psych. 2001;158:360–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baron JC, Martinot JL, Cambon H, Boulenger JP, Poirier MF, Caillard V, Blin J, Huret JD, Loc’h C, Maziere B. Striatal dopamine receptor occupancy during and following withdrawal from neuroleptic treatment: correlative evaluation by positron emission tomography and plasma prolactin levels. Psychopharmacology. 1989;99:463–472. doi: 10.1007/BF00589893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlegel S, Schlösser R, Hiemke C, Nickel O, Bockisch A, Hahn K. Prolactin plasma levels and D2-dopamine receptor occupancy measured with IBZM-SPECT. Psychopharmacology. 1996;124:285–287. doi: 10.1007/BF02246671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RM, Ansari MS, Riccardi P, Li R, Jayathilake K, Dawant B, Meltzer HY. Occupancy of striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptors by clozapine and quetiapine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1991–2001. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Catafau AM, Penengo MM, Nucci G, Bullich S, Corripio I, Parellada E, García-Ribera C, Gomeni R, Merlo-Pich E. Pharmacokinetics and time-course of D(2) receptor occupancy induced by atypical antipsychotics in stabilized schizophrenic patients. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:882–894. doi: 10.1177/0269881107083810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ritter LM, Meador-Woodruff JH. Antipsychotic regulation of hippocampal dopamine receptor messenger RNA expression. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42:155–164. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Florijn WJ, Tarazi FI, Creese I. Dopamine receptor subtypes: differential regulation after 8 months treatment with antipsychotic drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:561–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reuss B, Unsicker K. Atypical neuroleptic drugs downregulate dopamine sensitivity in rat cortical and striatal astrocytes. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;18:197–209. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rimondini R, Ferré S, Ogren SO, Fuxe K. Adenosine A2A agonists: a potential new type of atypical antipsychotic. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;17:82–91. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00033-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferré S, Ciruela F, Canals M, Marcellino D, Burgueno J, Casadó V, Hillion J, Torvinen M, Fanelli F, Benedetti Pd P, Goldberg SR, Bouvier M, Fuxe K, Agnati LF, Lluis C, Franco R, Woods A. Adenosine A2A–dopamine D2 receptor–receptor heteromers. Targets for neuro-psychiatric disorders. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2004;10:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ikeda K, Kurokawa M, Aoyama S, Kuwana Y. Neuroprotection by adenosine A2A receptor blockade in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2002;80:262–270. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen JF, Sonsalla PK, Pedata F, Melani A, Domenici MR, Popoli P, Geiger J, Lopes LV, Mendonça A. Adenosine A2A receptors and brain injury: broad spectrum of neuroprotection, multifaceted actions and “fine tuning” modulation. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;83:310–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Genovese T, Melani A, Esposito E, Mazzon E, Paola R, Bramanti P, Pedata F, Cuzzocrea S. The selective adenosine A2A receptor agonist CGS 21680 reduces JNK MAPK activation in oligodendrocytes in injured spinal cord. Shock. 2009;32:578–585. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181a20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kochanek PM, Hendrich KS, Jackson EK, Wisniewski SR, Melick JA, Shore PM, Janesko KL, Zacharia L, Ho C. Characterization of the effects of adenosine receptor agonists on cerebral blood flow in uninjured and traumatically injured rat brain using continuous arterial spin-labeled magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1596–1612. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cassada DC, Tribble CG, Young JS, Gangemi JJ, Gohari AR, Butler PD, Rieger JM, Kron IL, Linden J, Kern JA. Adenosine A2A analogue improves neurologic outcome after spinal cord trauma in the rabbit. J Trauma. 2002;53:225–229. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200208000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reece TB, Davis JD, Okonkwo DO, Maxey TS, Ellman PI, Li X, Linden J, Tribble CG, Kron IL, Kern JA. Adenosine A2A analogue reduces long-term neurologic injury after blunt spinal trauma. J Surg Res. 2004;121:130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reece TB, Okonkwo DO, Ellman PI, Maxey TS, Tache-Leon C, Warren PS, Laurent JJ, Linden J, Kron IL, Tribble CG, Kern JA. Comparison of systemic and retrograde delivery of adenosine A2A agonist for attenuation of spinal cord injury after thoracic aortic crossclamping. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Scatchard plot of [3H]YM09151-2 (D2DRs) (a) and [3H]NECA (A2AARs) (b) binding data performed in CHO cells co-expressing both D2DRs and A2AARs. Graphs show a representative Scatchard plot from saturation (a) and competition (b) binding studies performed three times with similar results (PPT 144 kb)