SUMMARY

Meiotic recombination occurs between one chromatid of each maternal and paternal homolog (homolog bias) versus between sister chromatids (sister bias). Physical DNA analysis reveals that meiotic cohesin/axis component Rec8 promotes sister bias, likely via its cohesion activity. Two meiosis-specific axis components, Red1/Mek1kinase, counteract this effect. With this precondition satisfied, other molecules directly specify homolog bias per se. Rec8 also acts positively to maintain homolog bias during crossover recombination. These observations point to sequential release of double-strand break ends from association with their sister. Red1 and Rec8 are found to play distinct roles for sister cohesion, DSB formation and recombination progression kinetics. Also, the two components are enriched in spatially distinct domains of axial structure that develop prior to DSB formation. We propose that Red1 and Rec8 domains provide functionally complementary environments whereby inputs evolved from DSB repair and late-stage chromosome morphogenesis are integrated to give the complete meiotic chromosomal program.

INTRODUCTION

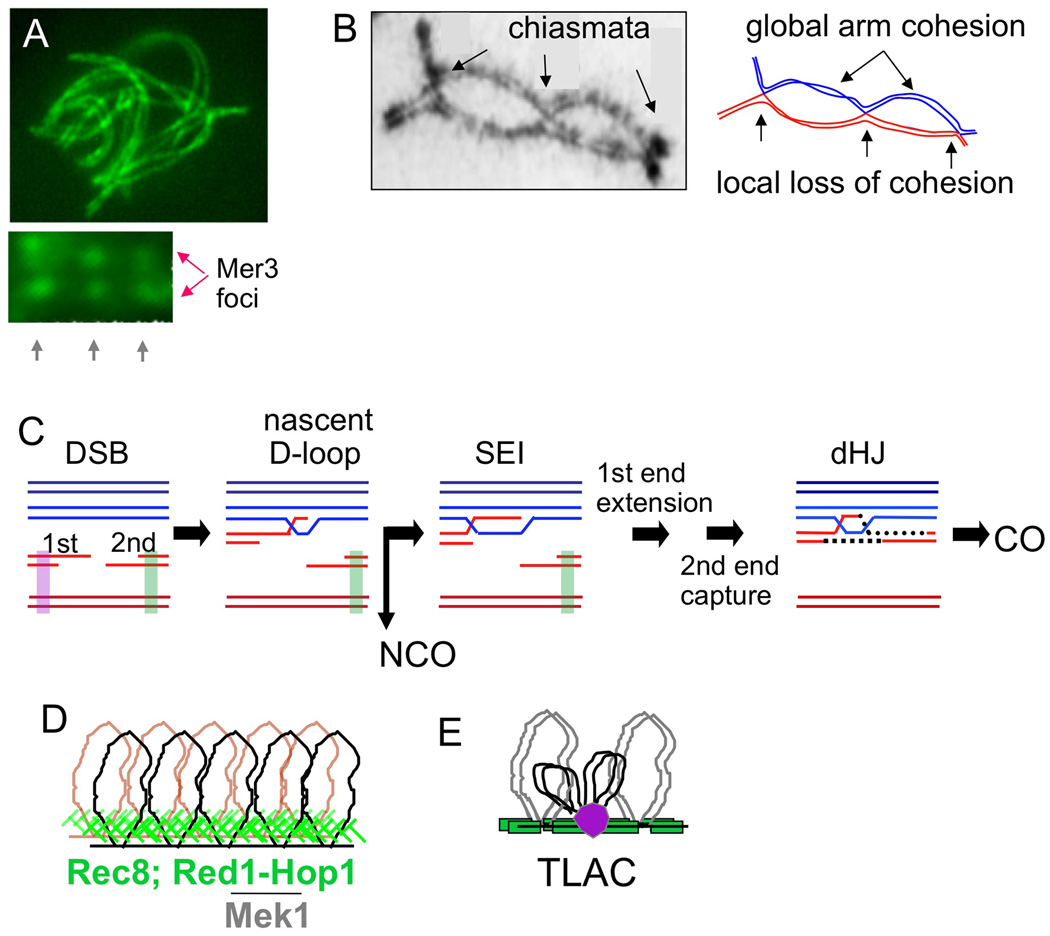

Meiosis involves a complex program of inter-homolog (IH) interactions mediated by DNA recombination. Recombination directs homolog pairing, promoting both homology recognition and physical juxtaposition of whole chromosomes in space (Figure 1A; Storlazzi et al., 2010). Later, recombination-generated crossovers (COs), plus cohesion along sister chromatid arms, create connections that direct homolog segregation at Meiosis I (MI) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Meiotic inter-homolog interactions.

(A, top) Presynaptic alignment of homolog axes (Sordaria image by D. Zickler). (A, bottom) Coaligned axes exhibit matched pairs of DSB-associated Mer3 complexes in an "ends-apart" configuration (Storlazzi et al., 2010). (B) Homologs are connected by COs between homologs plus global sister connections along chromosome arms (chiasmata; from Jones and Franklin, 2006). Note local sister separation at chiasmata. (C) Meiotic recombination between one sister of each homolog (Hunter, 2006). Purple and green bars = proposed sister cohesion near DSBs. (D) Cooriented sister linear loop array. (E) Recombining DNAs in chromatin loops are tethered to axes via axis/recombinosome (purple ball) contacts in “tethered-loop axis complexes” (Blat et al., 2002).

Meiotic recombination initiates after DNA replication. Thus, sister chromatids are present throughout. Nonetheless, in accord with its roles for IH interactions, this recombination usually occurs between two homolog chromatids rather than between sisters (homolog bias; Figure 1C; Zickler and Kleckner, 1999; Hunter, 2006). In contrast, recombinational repair of DNA damage in the mitotic cycle occurs preferentially between sister chromatids (sister bias), thus minimizing collateral damage (Bzymek et al., 2010).

In both situations, partner bias is specifically programmed, with chromosome structure components playing central roles. During mitotic repair, the sister may be favored partly because it is nearby; however, this intrinsic tendency is reinforced by sister chromatid cohesins (e.g. Covo et al., 2010; Heidiger-Pauli, 2010). During meiosis, recombination occurs in the context of tightly conjoined sister chromatid structural axes, which are implicated in many effects including partner choice. These axes comprise co-oriented linear arrays of loops whose bases are AT-rich “axis-association sites” that preferentially bind specific proteins (Figure 1D; Blat et al., 2002; Kleckner, 2006). Recombinosomes bind directly to regions between these sites and are associated with axes via tethered-loop axis complexes (Figure 1E; Blat et al., 2002). In budding yeast, and similarly in other organisms, homolog bias requires two interacting meiosisspecific axis components, Red1 and Hop1, plus their associated Rad53-related kinase Mek1 (Figure 1D; Schwacha and Kleckner 1994, 1997; Niu et al., 2005, 2007; Latypov et al., 2010; Terentyev et al., 2010; Goldfarb and Lichten, 2010; Martinez-Perez et al., 2005; Sanchez-Moran et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2010).

Meiotic homolog bias is established very early (Hunter, 2006). Recombination initiates via programmed DSBs whose 5' termini are rapidly resected, giving 3' single-stranded (ss) DNA tails. A "first" DSB end then contacts a homolog partner chromatid, e.g. via a nascent D-loop (Figure 1C). The "second" DSB end likely remains associated with its donor chromosome via interaction with its sister, yielding an "ends-apart" configuration, also seen cytologically (Figure 1A). Homolog bias persists thereafter. A few nascent D-loop interactions are designated for maturation into IH crossover (IH-CO) products. COs arise via single-end invasions (IH-SEIs) and double Holliday junctions (IH-dHJs). Remaining interactions are mostly resolved as IH noncrossover products (IH-NCOs) via other intermediates.

Here we further define roles of meiotic chromosome structure components for homolog bias, other recombination aspects, and chromosome morphogenesis. Of special interest is Rec8, a meiosis-specific homolog of general kleisin/cohesin Mcd1/Scc1/Rad21 (hereafter Mcd1). Rec8 occurs abundantly along conjoined sister axes (Klein et al., 1999) and, in yeast, is the only other known meiosis-specific axis component besides Red1/Hop1/Mek1. Sister cohesion, thus Rec8, is expected a priori to play a role in homolog-versus-sister partner discrimination. Two opposite models could be envisioned. (I) Tight conjunction of sister axes might block a DSB from interacting with its sister, thus forcing use of a homolog partner by default; Red1/Hop1/Mek1 would exert their effects by promoting such sister axis conjunction (Niu et al., 2005, 2007; Thompson and Stahl, 1999; Bailis and Roeder, 1998). (II) Rec8-mediated reinforcement of sister cohesion might favor inter-sister (IS) recombination, as during mitotic repair, thereby inhibiting use of the homolog. Cohesion would then be locally modulated for use of the homolog to predominate during meiosis.

In support of the second possibility, two features of recombination intrinsically require local loosening of sister relationships. (1) Recombination occurs between one chromatid of each homolog. Thus, at all sites, sister cohesion must be locally compromised. (2) CO at the DNA level is accompanied by exchange at the structural/axis level (“axis exchange”; Kleckner, 2006; Figure 1B). Thus, at CO sites, but not NCO sites, sisters must be locally differentiated and separated at both the DNA and axis levels (Blat et al., 2002). In fact, Rec8 is specifically absent at chiasmata (Eijpe et al., 2003) and local separation is seen at CO sites while recombination is in progress during prophase (Storlazzi et al., 2008).

However, despite these local modulations, sister cohesion must concomitantly be maintained globally along chromosome arms to enable regular homolog pairing at prophase and regular segregation at MI (Figure 1B). Thus, meiotic chromosomes face conflicting demands for global cohesion maintenance versus local weakening of cohesion at recombination sites.

Results presented below define distinct, but integrated, roles for Rec8/cohesion and Red1/Mek1kinase in homolog bias, sister cohesion, and recombination timing/kinetics; present evidence for association of recombinosomes with developing chromosome axes before DSB formation; and show that Red1 and Rec8 localize to different chromosomal domains on a per-cell basis. Multiple general implications emerge.

RESULTS

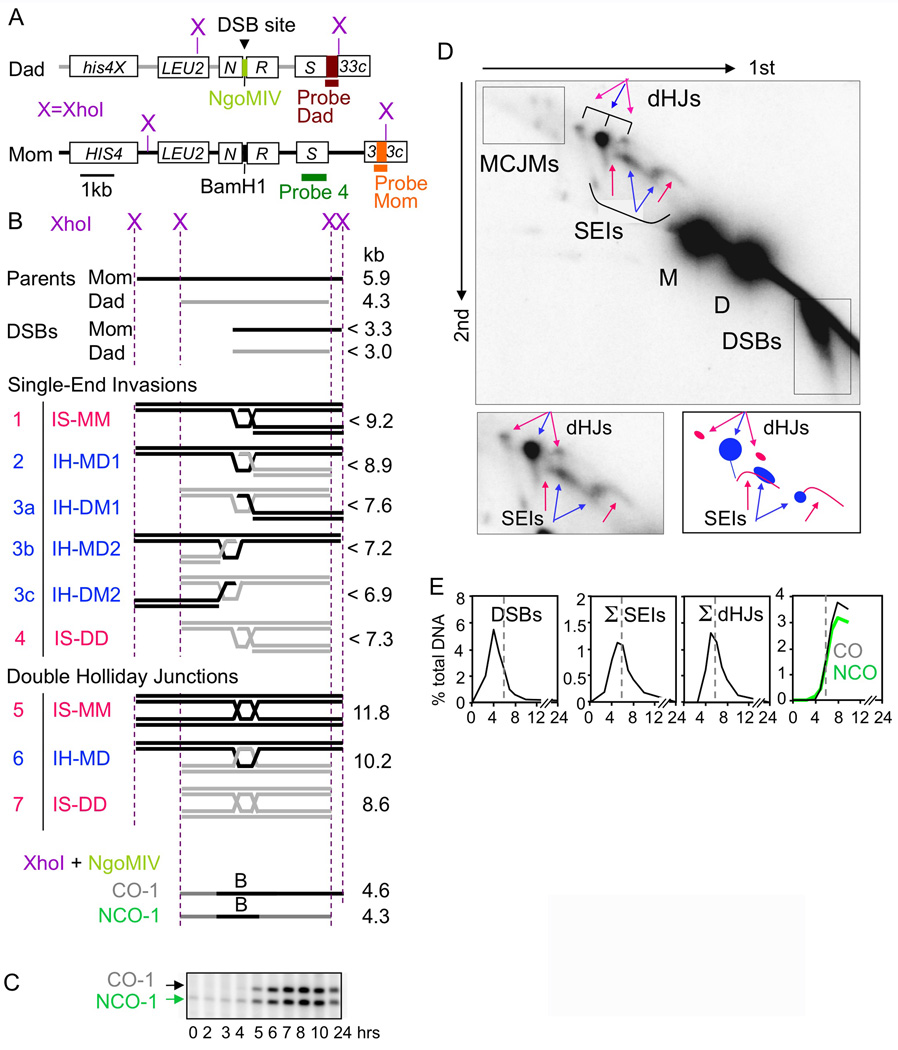

Physical analysis of recombination

Recombination intermediates and products were analyzed at the HIS4LEU2 hot spot (Figure 2A–D; Hunter and Kleckner, 2001; Oh et al., 2007). In cultures undergoing synchronous meiosis, samples were taken at desired time points and subjected to DNA extraction, restriction digestion, and one- and two-dimensional (1D and 2D) gel electrophoresis. Species of interest were detected by Southern blotting (Probe 4; except as noted). DSBs, SEIs and dHJs are detected in 2D gels, which separate species first by molecular weight (MW) and then by shape. IH-COs and -NCOs are detected via diagnostic fragments in 1D gels. In WT meiosis, intermediates appear and disappear and products emerge (Figure 2E).

Figure 2. Physical analysis of meiotic recombination.

(A) HIS4LEU2 locus (Martini et al., 2006) and Southern blot probes. (B) DNA species generated by indicated digests. (C) Fragments diagnostic of IH-COs and IH-NCOs, each representing a subset of total products (Storlazzi et al., 1995). (D) Top: 2D gel displaying parental and intermediate species (B; plus multi-chromatid joint molecules, “MCJMs” (Oh et al., 2007). Bottom: Cartoon. IH/IS species in blue/pink (B, text). (E) Recombination in WT meiosis (Σ = IH+IS). See also Figure S1.

Recombination in the absence of Rec8 and/or Red1 or, analogously, Rec8 and/or Mek1kinase, was examined in two isogenic sets of WT, single and double mutant strains. Alleles were complete deletion mutations (rec8Δ, red1Δ) or mek1as, which encodes a mutant protein whose kinase activity can be abolished by a chemical inhibitor (Niu et al., 2005). mek1as(−IN) and mek1as(+IN) denote absence or presence of inhibitor added at t=0, respectively. Time courses were performed for all strains at both 33°C and 30°C with samples taken at t = 0, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10 and 24h after initiation of meiosis. The same patterns occur at both temperatures. 33°C data are shown to permit optimal comparison with zmm mutants (Börner et al., 2004; below). Each strain, at each temperature, was examined in multiple independent time courses (N=53) with highly consistent results (Figure S1A).

All mutants have reduced DSB levels (below) and thus reduced total recombinational interactions. To permit direct comparisons among all strains with regard to post-DSB effects, levels of all species shown in graphs are normalized such that they are presented on a “per DSB” basis. Specifically: for all mutants, levels of all species are increased to those predicted if DSB levels would be the same as in WT.

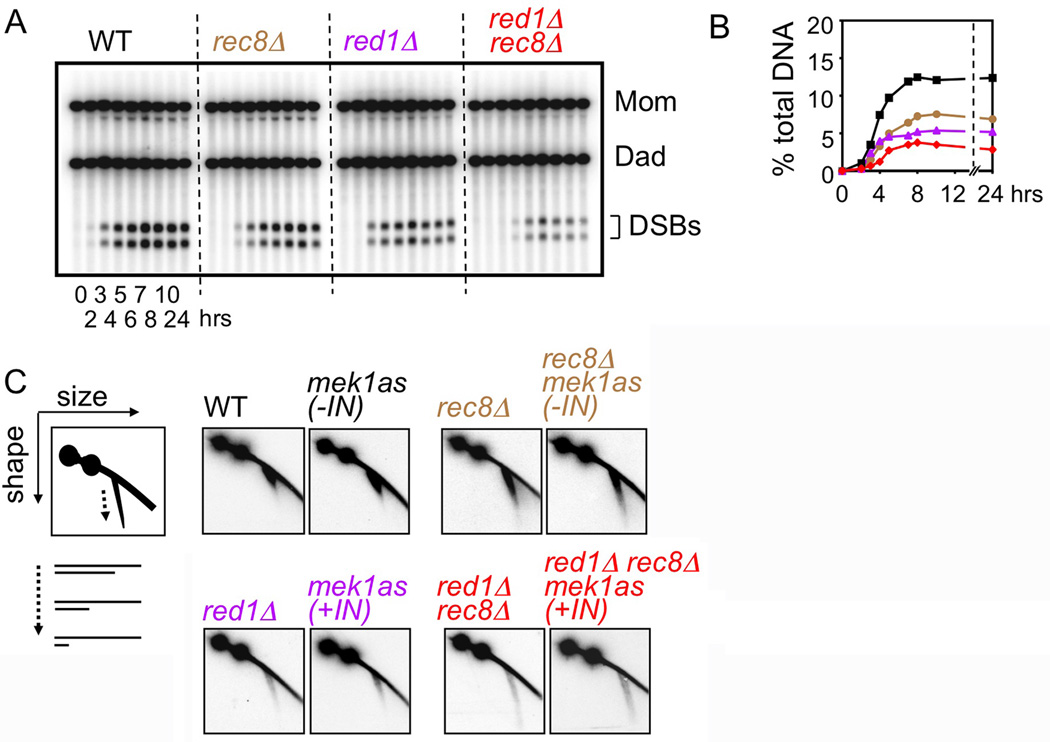

DSB formation and resection

DSBs were assayed in rec8Δ and/or red1Δ using a background where DSBs accumulate rather than turning over (rad50S; Figure 3AB). At HIS4LEU2, each single mutant exhibits modestly reduced DSB levels. The double mutant exhibits approximately the product of the two individual defects. Thus, Rec8 is required for DSB formation, similarly to, but largely independently of, Red1. DSB deficits occur in rec8Δ at three other DSB hot spots (A.J. unpublished), as for red1Δ at the same sites (Blat et al., 2002), and for rec8Δ genome-wide (Kuguo et al, 2009). mek1as(+IN) confers the same reduction in HIS4LEU2 DSBs as red1Δ (K.K. unpublished).

Figure 3. DSB levels and resection.

(A) 1D gel showing rad50S DSBs. (B) Quantification of DSB levels in (A). (C) 2D gel detection of DSB resection: cartoon plus WT/ mutant data from time point of maximum abundance.

WT and mek1as(−IN) DSBs exhibit ~500nt 3' single-stranded (ss) DNA tails (Hunter, 2006), sensitively revealed by 2D gels (Figure 3C). rec8Δ and rec8Δ mek1as(−IN) exhibit modest hyper-resection; red1Δ and mek1as(+IN) exhibit dramatic hyper-resection; double mutants exhibit more hyper-resection than either component single mutant (Figure 3C). Thus, Rec8 and Red1/Mek1kinase each contribute to control of DSB end resection, via distinct effects.

Homolog bias in WT

CO-fated interactions yield IH-dHJs plus two types of IS-dHJs as seen in 2D gels (Schwacha and Kleckner 1994, 1997; Figure 2D). The ratio of IH-dHJs to IS-dHJs (summed from both parents) is 5:1 in WT and mek1as(−IN) (Figure 4B; Figures S1B, S2–S4), reflecting homolog bias for CO recombination. Homolog bias is also robust for NCOs: at HIS4LEU2, total IH events (COs plus NCOs), account for ~90% of total DSBs (Martini et al., 2006; N. Hunter, personal communication).

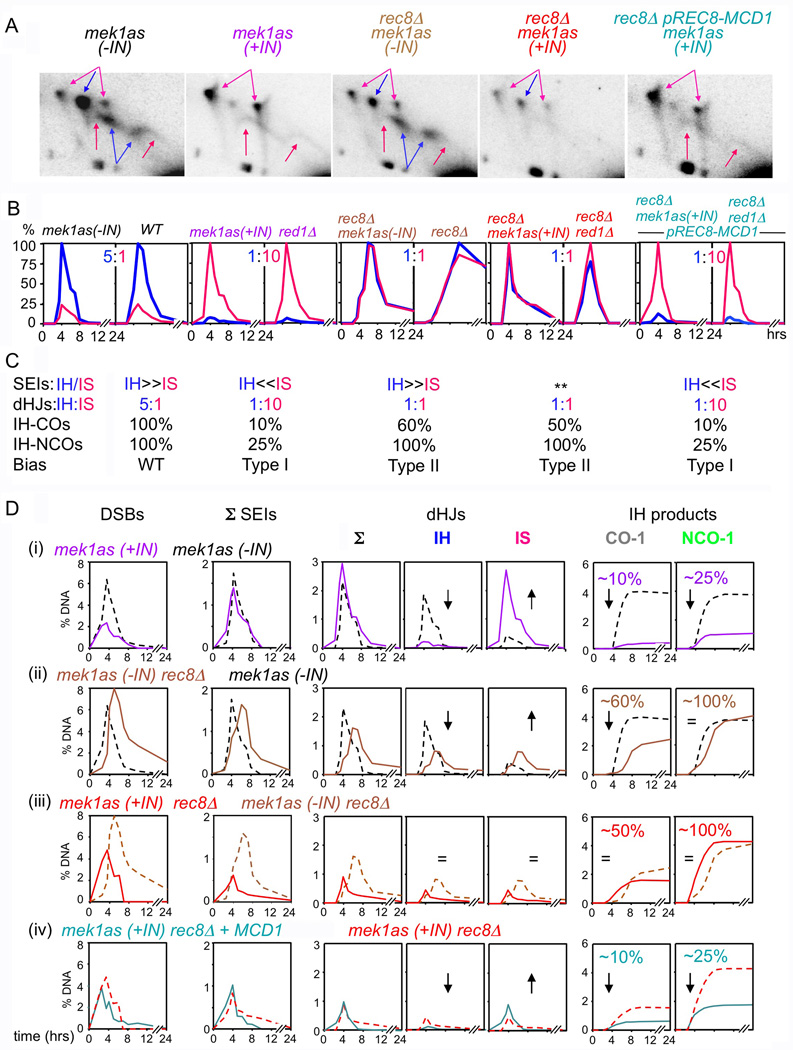

Figure 4. Partner choice in chromosome structure mutants.

(A) Gels of SEIs/dHJs at time point of maximum level in (B). Blue = IH; Pink = IS. (**) SEI levels too low for accurate IH/IS discrimination. (B) IH/IS dHJ levels over time plotted as % maximum level of most abundant species. (C) Summary of data in (A, B, D) and thus-defined Type I/Type II phenotypes. (D) Time course analysis of mek1as strain set displayed as pair-wise comparisons between featured strain (solid line) and appropriate reference strain (dashed line). All species levels in mutants are normalized for DSB reductions to permit “per-DSB” comparisons (text). Gels are presented without such adjustment with parental signals at the same intensities in all panels to indicate absolute levels. Corresponding full gels in Figure S2. Analogous data for MEK1 ± red1Δ strains in Figures S3, S4. Note: in rec8Δ, as well as in rec8Δmek1as(−IN), nearly all DSBs progress to products, albeit with a significant delay (Figure S3 legend). See also Figure S2–S5.

In the absence of Red1/Mek1kinase, homolog bias is converted to sister bias

In red1Δ and mek1as(+IN), total dHJ levels (IH+IS) are the same as in WT/mek1as(−IN). However, in both mutants, IH-dHJs are strongly reduced while IS-dHJs are compensatorily increased, yielding an IH:IS dHJ ratio of 1:10 (versus 5:1 in WT) (Figure 4A–D). Absolute IH-CO levels are also strongly reduced in both mutants, as are IH-NCO levels (Figure 4D). These findings, plus prior findings (Introduction), point to a general defect in homolog bias at an early step in recombination, prior to CO/NCO differentiation, with consequences for both branches. This constellation of mutant phenotypes is defined as "Type I" (Figure 4C). It is interpreted as reflecting roles for Red1 and Mek1kinase in "establishment" of homolog bias. Thus: in WT meiosis, Red1/Mek1kinase converts sister bias into homolog bias at an early step.

Homolog bias is detectable at the SEI stage

Previous studies identified IH-SEIs (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001). IS-SEI signals were not identified. In red1Δ and mek1as(+IN), where IH interactions are strongly reduced and IS interactions are strongly increased, IH-SEI signals are not visible; however, in the “SEI” region of the gel (Figure 2D), two arc signals are prominent (Figure 4A, 5A). These signals correspond to Mom-Mom and Dad-Dad IS-SEI species: (i) The centers of mass of the two signals occur at the expected MW positions, ~9.2 and ~7.3 kb (Figure 5A). (ii) Hybridization with homolog-specific probes shows that each signal contains only material from the appropriate parent (Figure 5A). (iii) The two signals appear and disappear, coordinately, with the same kinetics as IH-SEIs in WT strains (Figure 4D). (iv) The two arc species are not DNA replication intermediates: they appear two hours after completion of replication (e.g. below); further, replication intermediates are not recovered in the DNA extraction procedure used (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001).

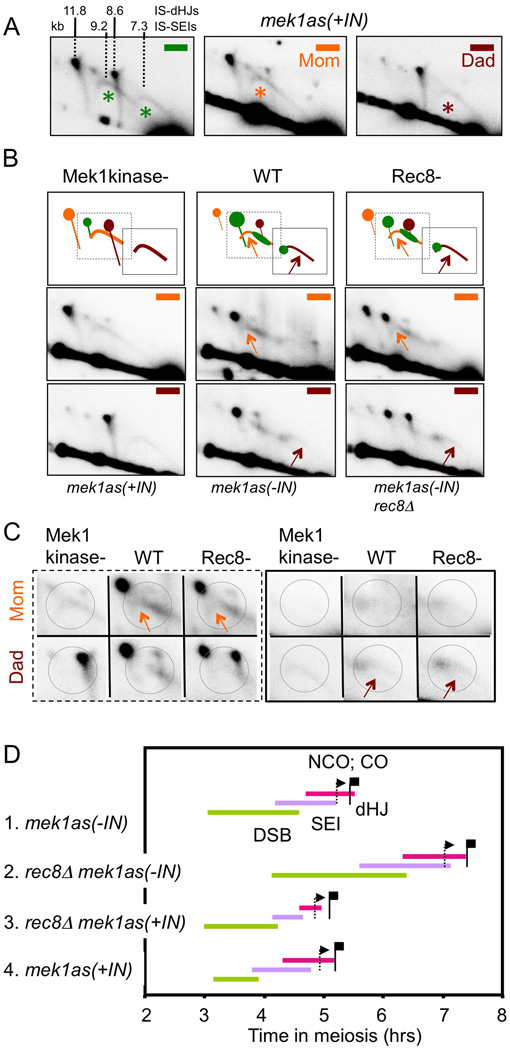

Figure 5. Identification of IS-SEIs.

(A) dHJs/SEIs from mek1as(+IN) visualized with general, Mom- and Dad-specific probes (green, orange, brown; Figure 2A); predicted species sizes from Figure 2B indicated. (*) marks IS-SEI. (B) dHJs/SEIs from WT and mutants visualized with Mom- and Dad-specific probes. Gel regions (bottom); cartoon (top) including regions expanded in (C); arrows indicate regions of IS-SEI signals visible in WT/rec8Δ. (C) Enlarged views of gel areas boxed in (B) cartoon; circles denote regions of differential Mom/Dad hybridization. (D) Timing and kinetics of recombination in indicated strains. For any intermediate species of interest, integration of the primary data (e.g. Figure 4D) yields three parameters: average lifespan; time of appearance in 50% of cells; and time of disappearance (one lifespan later) (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001). These parameters are denoted, for DSBs, SEIs and dHJs, by the length, beginning and end, respectively, of a corresponding line. Times at which IH-CO and IH-NCO products have appeared in 50% of cells (i.e. at half their final level) shown by corresponding flags. Analogous data for MEK1± red1Δ strain set in Figure S6. See also Figure S2, S4–S6.

The same IS-SEI arcs are also detectable in WT and mek1as(−IN) (Figure 5BC). IH-SEIs form prominent bar signals that hybridize to both Mom- and Dad-specific probes. IH-SEIs are detectable by the presence of weak signal in flanking regions corresponding, respectively, to the higher MW portion of Mom-Mom IS-SEIs and the lower MW portion of Dad-Dad IS-SEIs (Figure 5BC, arrows/circles). Each signal migrates with appropriate mobility, is detected only with the appropriate homolog-specific probe, and is rarer than IH-SEIs as expected from homolog bias. Other portions of IS-SEI arcs overlap IH-SEI bars. These patterns are confirmed in Rec8− strains (Figure 5BC).

The unique arc shape of IS-SEI signals is seen in WT, as well as Red1−/Mek1kinase−. Thus it is not mutant-specific but is characteristic of IS (versus IH) interactions per se. Each arc spans MWs both higher and lower than “expected” (Figure 5AB). Lower MW material is explained by DSB hyper-resection, prominent in the mutants but discernible at a low level in WT/mek1as(−IN) (Figure 3C). Higher MW material implies occurrence of DNA synthesis, presumably to extend 3' strand termini.

Despite their unusual morphology, these species clearly represent CO-designated IS-SEIs. (i) In a strain specifically defective CO recombination versus NCO recombination, IS-SEI levels are coordinately reduced, with the same altered variation over time, as all known CO-specific species (zip3Δ; Figure S5). (ii) IS-SEIs appear and disappear with the same kinetics as IH-SEIs, qualitatively and quantitatively (red1Δ/mek1as(+IN) vs WT/mek1as(−IN) in Figures 4D, S3; WT/mek1as(−IN) gels in Figures S2, S4). (iii) In Red1−/Mek1kinase− strains, where IS-dHJs occur at the same high levels as IH-dHJs in WT meiosis, there are no other detectable species in the MW region of a 2D gel where SEIs should appear; moreover, the IS-SEI levels in these mutants are the same as for IH-SEIs in WT. Thus: the arc morphology of IS-SEIs suggests that the 3’ end status of CO-fated IS-SEIs is intrinsically less stringently controlled than that of CO-fated IH-SEIs.

In the absence of Rec8, homolog bias is established, then lost, during CO formation, at the SEI-to-dHJ transition

In rec8Δ and mek1as(−IN) rec8Δ, DSBs, SEIs and dHJs appear and disappear, and IH-CO and IH-NCO products appear, all at substantial levels (Figure 4D; Figure S3 legend). IH-NCO levels are very similar to those in WT/mek1as(−IN) strains, suggesting that homolog bias is established normally for NCO recombination (Figure 4D, S3). Further, just as in WT/mek1as(−IN), IH-SEIs are more abundant than IS-SEIs (Figure 5BC). Thus, homolog bias is established efficiently also for CO recombination.

However: the ratio of IH:IS dHJs in both Rec8− strains is 1:1 (versus 5:1 in WT) and the IH-CO level, while high, is modestly reduced (Figure 4A–D). Such effects could be explained in two ways: (i) IH-SEIs might be lost to unknown fates, thus specifically reducing the level of IH-dHJs and IH-COs. (ii) Homolog bias might be lost at the SEI-to-dHJ transition, with all SEIs progressing, but with each SEI having an equivalent probability of giving rise to either an IH-dHJ or an IS-dHJ (IH:IS dHJ = 1:1) and a commensurate reduction in IH-COs. We favor the second scenario:

-

-

In rec8Δ mek1as(−IN), total dHJ levels are very similar to those in REC8 mek1as(−IN); however, the level of IH-dHJs is reduced while the level of IS-dHJs is compensatorily increased (Figure 4D). Thus, SEIs progress efficiently to dHJs but are concomitantly redistributed between IH and IS species.

-

-

In scenario (i), differential loss of IH-SEIs to the same level as IS-SEIs predicts that IH-COs will be reduced to ~20% the WT level; in scenario (ii) equi-partitioning of SEIs to IH- and IS-dHJs predicts that IH-CO levels will be reduced to ~60% the WT level (Figure S3). In rec8Δ mek1as(−IN), IH-COs occur at ~60% the WT level (Figure 4D).

-

-

The IH:IS dHJ ratio in Rec8− mutants is exactly 1:1 (Figure 4B; 1.04±0.14; range = 0.83~1.25; N=12). It seems improbable that equivalency would arise by chance as in (i) and probable that it reflects an intrinsic feature of recombination as in (ii) (Discussion). Also, random interaction of a DSB with available partners would give a 2:1 IH:IS dHJ ratio; thus, it is not the case that a DSB has access to all possible partner chromatids (two sisters and one homolog) at the SEI-to-dHJ transition.

The Rec8− partner choice phenotype is defined as "Type II” (Figure 4C). It is interpreted to mean that homolog bias is: (a) efficiently established; (b) efficiently maintained both throughout NCO formation (giving normal IH-NCO levels) and during CO formation through the SEI stage (giving normal IH bias for SEIs); but (c) lost at the SEI-to-dHJ transition, with all SEIs (IH and IS) progressing efficiently but with either type of SEI having an equal probability of giving either an IH- or IS-dHJ (IH:IS dHJ = 1:1) and corresponding products, giving a 40% reduction in IH-COs to 60% the WT level.

This interpretation is supported by comparison of rec8Δ with zip3Δ (Figure S5). Zip3 represents a prominent group of CO-specific functions (ZMM’s; Börner et al., 2004). Differently from rec8Δ, zip3Δ: (a) shows defective progression of DSBs to CO-specific intermediates and a severe reduction in IH-COs; (b) exhibits this defect at the DSB-to-SEI transition; and (c) does not eliminate homolog bias among residual SEIs and dHJs (IH:IS dHJ = 3:1). rec8Δ zip3Δ exhibits the sum of both single mutant defects: severe reductions in SEIs, dHJs and IH-COs (zip3Δ), robust homolog bias at the SEI stage and for NCO recombination (both mutants), and IH:IS dHJ = 1:1 (rec8Δ)

Rec8 promotes sister bias and Red1/Mek1 antagonizes that effect, thus making homolog bias possible

rec8Δ mek1as(+IN) and rec8Δ red1Δ double mutants exhibit the same phenotype as rec8Δ mek1as(−IN) and rec8Δ RED1: IH:IS dHJ = 1:1; WT levels of IH-NCOs; and IH-COs reduced to ~60% the WT level (Figure 4). IH/IS SEI status cannot be assessed because levels are too low, reflecting reduced total DSBs (above) and rapid turnover of intermediates (below). Nonetheless, since all other predicted phenotypes are observed, we conclude that in Rec8− Red1−/Mek1kinase− double mutants, as in Rec8− single mutants, homolog bias is established normally, but is not maintained during CO recombination (Type II; Figure 4C). This correspondence is confirmed by inactivating Mek1 kinase in rec8Δ mek1as strain at various times in meiosis: a 1:1 IH:IS dHJ ratio is seen regardless of whether inhibitor is added at t=0 (Rec8− Mek1kinase− condition), t=7h (Rec8− Mek1kinase+ condition), or any point in between (K.K. unpublished).

These results were unexpected. Absent further complexities, a double mutant should have exhibited the earlier "establishment" defect of Red1−/Mek1kinase− (Type I), not the later "maintenance" defect of Rec8− (Type II). Several new features are thus revealed:

Homolog bias is established even when both Red1/Mek1kinase and Rec8 are absent (in double mutants); thus, other components directly mediate this process.

Red1/Mek1kinase is important for establishment of homolog bias when Rec8 is present (Red1−/Mek1kinase− single mutants) but not when Rec8 is absent (double mutants). Thus, formally, Rec8 specifies an inhibitor of bias and Red1/Mek1kinase is required to remove that inhibitor. In Rec8− strains, there is no inhibitor of homolog bias; thus, homolog bias is established, regardless of whether the inhibitor of the inhibitor is present (Rec8− Red1+/Mek1kinase+) or absent (Rec8− Red1−/Mek1kinase−).

When Rec8 is present and Red1/Mek1kinase is absent, sister bias is observed (above). Thus, in its inhibitory role, Rec8 mediates sister bias, concomitantly precluding establishment of homolog bias. Red1/Mek1kinase counteracts these effects, converting sister bias back to homolog bias.

Maintenance of bias during CO recombination is defective in both Rec8− and Rec8− Red1−/Mek1kinase−. Red1/Mek1kinase might be irrelevant for bias maintenance. Alternatively, Red1/Mek1kinase may also be required for maintenance of bias, in addition to Rec8, with both functions being essential for the same step. If so, a bias maintenance defect would be observed also in Red1−/Mek1kinase− single mutants. Supporting this model: residual IH products arising in those mutants exhibit the same differential reduction of COs versus NCOs, by ~60%, as Rec8−.

Meiotically-expressed Mcd1 fully substitutes for Rec8 during establishment of homolog bias

The general kleisin ortholog of Rec8, Mcd1, is not prominent in meiosis but can be expressed meiotically from the REC8 promoter (pREC8-MCD1) (Lee and Amon, 2003). Expression of Mcd1 in Rec8− Red1−/Mek1kinase− double mutants fully restores a Rec8+ Red1−/Mek1kinase− phenotype. That is, expression of Mcd1 converts the double mutant Type II phenotype back to the Type I phenotype of the single mutant (Figure 4). Thus, Mcd1 fully substitutes for Rec8 as an inhibitor of homolog bias establishment and concomitant promoter of sister bias. Also, expression of Mcd1 in Rec8− Red1+/Mek1kinase+ single mutants has no effect on establishment of bias: IH-NCOs still occur at WT-like levels and substantial levels of IH-COs also occur (K.K. unpublished). Thus, the inhibitory effects of Mcd1 are efficiently counteracted by Red1/Mek1kinase, just as for Rec8.

Expression of Mcd1 in Rec8− Red1+/Mek1kinase+ single mutants increases the IH:IS dHJ ratio from 1:1 to 2:1, but not to the 5:1 observed in WT (K.K. unpublished). This likely implies that Mcd1 can substitute only partially for Rec8 during maintenance of bias during CO recombination.

Red1/Mek1kinase and Rec8 regulate progression of recombination

In a given strain, the time at which a given species appears in 50% of cells, its duration (lifespan), and the time at which it disappears in 50% of cells (one lifespan after it appears) can all be defined (Figures 5D; S6). All mutants exhibit altered timing/kinetics of recombination.

Lines 1 vs 2

Absence of Rec8 delays DSB formation by two hours (asterisk). Since replication is only modestly perturbed (Cha et al., 2000), this delay arises after S-phase. Absence of Rec8 also significantly prolongs DSB, SEI and dHJ lifespans. However, nearly all DSBs do finally emerge as products (Figures 4D, S2, S4).

Lines 2 vs 3

All delays in Rec8− strains are absent in Rec8− Red1−/Mek1kinase− strains and the mek1as(−IN) allele is "hypomorphic" for this effect (Figures 5D vs S6; S3). Thus: Red1/Mek1kinase mediates all rec8Δ timing delays. Importantly, since Rec8− Red1+/Mek1kinase+ and Rec8− Red1−/Mek1kinase− strains both exhibit a Type II phenotype (above), Red1/Mek1kinase affects the rate of recombination progression in rec8Δ but not its outcome. Red1/Mek1/Hop1 also mediates timing delays in WT meiosis (Malone et al., 2004). In both Rec8− and in WT, Red1/Mek1/Hop1 may sense local recombination status and block progression to the next stage until prior steps are properly completed (Discussion).

Lines 1 vs 4

Red1−/Mek1kinase− single mutants exhibit reduced DSB lifespans relative to WT. However, SEI/dHJ lifespans and the time of appearance of products are unaltered. Thus, reduced DSB lifespan could reflect promiscuous DSB end resection/extension of IS-fated events (above).

Lines 3 vs 1 or 4

Rec8− Red1−/Mek1kinase− strains exhibit dramatically shorter SEI and dHJ lifespans than either Rec8+ Red1−/Mek1kinase− or WT. Rec8 may act as a regulatory “brake” for recombinational progression, independent of limitations conferred by Red1/Mek1kinase; when both factors are absent, interactions race through biochemical steps (Discussion).

Rec8 and Red1 are both required for normal sister cohesion

Sister relationships were examined in intact cells using fluorescent repressor/operator arrays at two loci, each located in the middle of a long chromosome arm and present on one homolog of a diploid (Figures 6A; S7). In WT, cohesion is maintained throughout prophase: separated sister loci (two-focus cells) appear at MI (Figure 6B). The same is true in red1Δ (Figure 6B). However, some premature sister separation was seen for Red1−/Mek1− mutants in spread preparations (Bailis and Roeder 1998), e.g. due to increased spatial resolution.

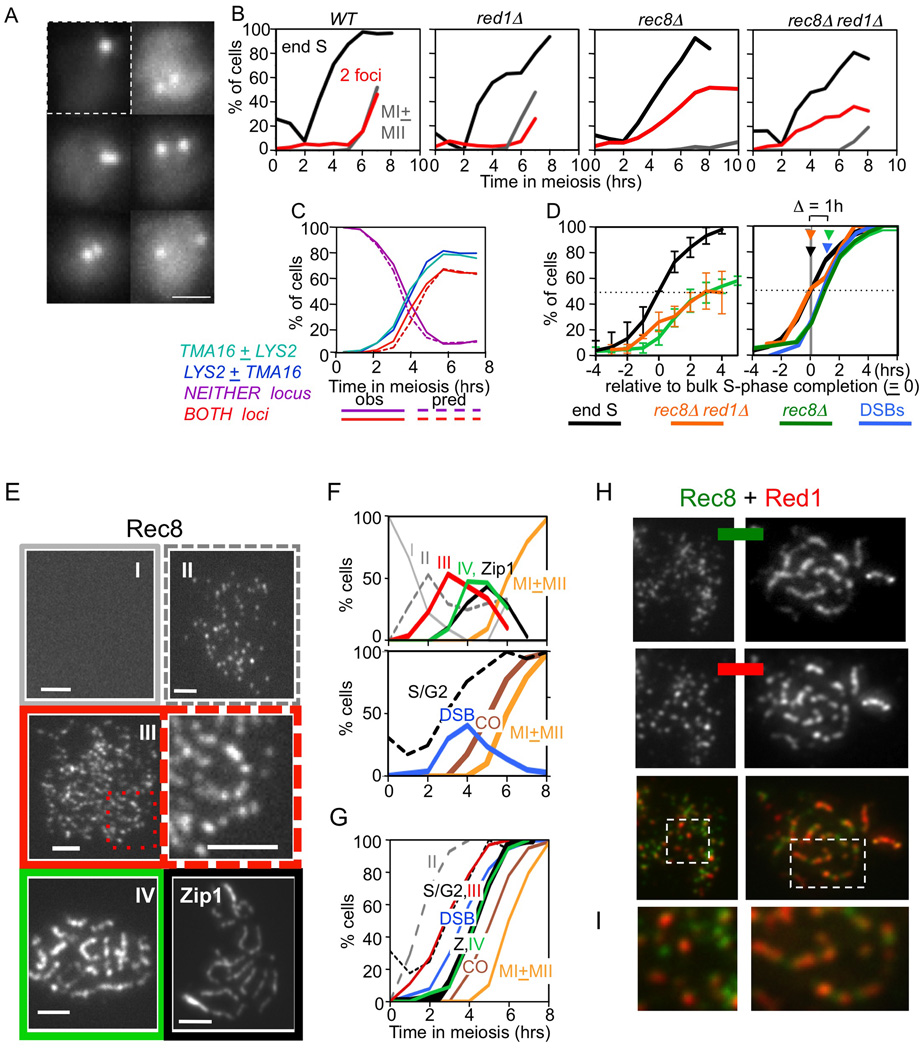

Figure 6. Sister cohesion and axis morphogenesis.

(A) Strains carrying lacO and/or tetO array(s) and expressing a cognate fluorescently-tagged Lac and/or Tet repressor were analyzed for sister association in fixed whole cells. One focus = unreplicated, or replicated but unseparated, sisters (upper left). Two foci = replicated and visibly distinct sisters (other panels). Bar= 1µm. (B) Percentages of cells in representative cultures showing: 4C DNA content (black); visibly distinct sisters at a single locus as in (A) (red); or first or both meiotic divisions (grey). (C) For a strain carrying lac and tet arrays at different loci, percentages of cells exhibiting separation at each locus considered individually, at neither locus or at both loci (solid lines) and corresponding percentages predicted for independent loss of cohesion at the two loci (dashed lines). Predicted percentages at each time point given by the binomial distribution, assuming that 5% of cells fail to enter meiosis (Padmore et al., 1991). (D) Averages of multiple experiments for rec8Δ and rec8Δ red1Δstranis. Values at each time point were normalized to the time when 50% of cells exhibited 4C DNA content (new "t=0"), thus correcting for culture-to-culture variation in timing of meiosis initiation. Left: absolute percentages of cells that have completed DNA replication (4C; grey; N=12, including WT and mutant cultures) and of two-focus cells in rec8Δ (green; N=5) or rec8Δ red1Δ (orange; N=3). Values = average ± SD. Note: SDs for the two mutant curves do not overlap; thus, differences in their average values are meaningful. Right: curves at left were normalized to their final values, which represent completion of the corresponding events in 100% of meiotically active cells, thus permitting comparisons with one another and with appearance of DSBs (from panel E). Arrows indicate times when 50% of cells have completed each event. (E) Chromosome spreads of WT cells immunostained for Rec8-myc or Zip1. Rec8 patterns were assigned to categories I–IV (text). Boxed region from (III) enlarged at right. Zip1 pachytene pattern also shown. Bar = 2µm. (F) Top: appearance and disappearance of nuclei for each category in (E) over time in meiosis (N>100 for each time point). Bottom: timing of other events in the same culture. (G) Fraction of cells that have progressed up to, or beyond, each indicated stage, given by cumulative curves derived from noncumulative curves in (F) (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001). (H) Co-immunostaining of Rec8-myc and Red1 at leptotene/zygotene (left) and pachytene (right) in spread chromosomes. (I) Enlargements of regions boxed in (H). See also Figure S7.

In rec8Δ and red1Δ rec8Δ, nuclei with separated sisters appear early and their level rises to a final value of 50–60% (Figure 6B; Klein et al, 1999). Residual sister association is likely not mediated by Mcd1: (i) 50% residual association is observed in mnd2Δ, where premature activation of separase should eliminate Mcd1 as well as Rec8 (Penkner et al., 2005); and (ii) 50% residual association is seen in Mcd1-deficient mitotic cells where Rec8 is absent (Díaz-Martínez et al., 2008).

Sister association might be absent in Rec8− strains via ~50% loss at each individual locus in every cell. Alternatively, 50% of cells might exhibit full association at all loci while 50% exhibit complete absence at all loci. The first situation pertains: if sister relationships are analyzed simultaneously at two arm loci, the frequencies of nuclei exhibiting two foci at both loci, or at neither locus, match the predictions of the binomial distribution for independent absence of association at each locus (Figure 6C).

Sister association is established during S-phase. Multiple independent cultures were evaluated for both DNA replication and sister association over time (Figure 6D). The percentage of cells that has completed S-phase is the percentage exhibiting a 4C DNA content. For a given locus, the percentage of cells lacking Rec8-mediated sister association is the fraction of two-focus cells at that time point divided by the fraction of two-focus cells at late times when Rec8− mediated association is absent in all cells (above). In both rec8Δ and red1Δ rec8Δ, two-focus cells appear after completion of S-phase. Thus, Rec8 is not required for establishment of sister association but is required for its maintenance after S-phase, as known for all previously studied organisms (discussion in Storlazzi et al., 2008). Also, two-focus cells appear about an hour earlier in red1Δ rec8Δ than in rec8Δ (Figure 6D). Thus, Red1 promotes sister association in the absence of Rec8 as well as WT.

Rec8 and Red1 localize to distinct domains along organized chromosomes prior to DSB formation

Do pre-DSB recombinosomes interact with chromosome structure components even prior to DSB formation and homolog bias establishment? In budding yeast, a challenge to this idea is the fact that silver-staining axial elements (AEs) and defined lines of immunostaining for chromosome structure components become apparent ~90 min after DSB formation, concomitant with SEI formation at zygotene (Padmore et al., 1991; Hunter and Kleckner, 2001). To further characterize axis morphogenesis, nuclei exhibiting detectable Rec8 signals were sorted into four categories. Category (I): no staining. Category (II): modest numbers of foci with no indication of organization. Category (III): larger numbers of foci with a clear tendency for linear arrays. Category (IV): strongly staining lines or rows of prominent foci (Figure 6E). Nuclei of the four categories disappear (I) and appear (II–IV) progressively. As expected, Category IV appears contemporaneously with SC formation (lines of SC component Zip1) well in advance of COs and MI (Figure 6FG). Identification of Category III reveals that longitudinal chromosome organization is present much earlier: Category III appears after completion of S-phase but an hour prior to DSB formation, assayed in the same culture (Figure 6G). The same patterns are seen for Red1 (B.W. unpublished).

Co-staining for Red1 and Rec8 further reveals that the two types of axis components exhibit distinct patterns of loading along chromosomes, both early and late (Figure 6H). Both components occur broadly throughout the chromosomes; however, regions of abundance for Red1 are often depleted for Rec8, and vice versa. Red1−rich and Rec8-rich domains are seen to alternate along a chromosome (e.g. Figure 6I).

Discussion

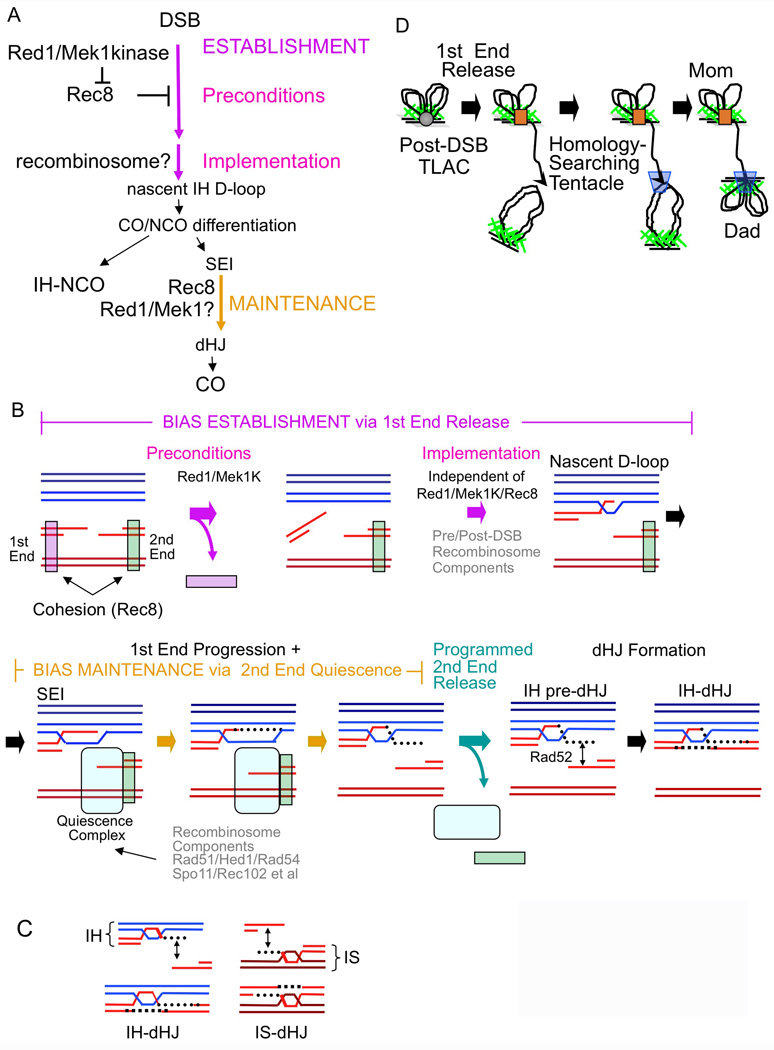

The present study suggests that Rec8 promotes sister bias, likely via its cohesin function, thereby inhibiting establishment of homolog bias. The role of Red1/Mek1kinase is to counteract this effect (Figure 7A). Despite this interplay, when Red1 and Red1/Mek1kinase are both absent, homolog bias is still established efficiently. Thus, these structural components satisfy “preconditions” for homolog bias, which is then directly implemented by other components (Figure 7A). During CO recombination, but not NCO recombination, bias also must be actively maintained, at the SEI-to-dHJ transition. Rec8 is required positively for this effect (Figure 7A). Red1/Mek1kinase might be similarly involved. All roles of Rec8 and Red1 for partner choice mirror the competing dictates of meiosis for maintenance of cohesion globally versus disruption locally at sites of recombination. Taken together with other results, our findings have additional implications.

Figure 7. Roles of structural components for meiotic recombination.

(A) Formal logic for establishment and maintenance of homolog bias as defined by mutant phenotypes. (B) Quiescence and release of the first DSB end from its sister in relation to establishment of homolog bias, and of the second DSB end from its sister in relation to maintenance of homolog bias. (C) Initiation of pre-dHJ formation at a homolog-associated first end, or a sister-associated second end, yields an IH-dHJ or an IS-dHJ respectively. (D) Release of the first DSB end from its tethered-loop axis complex yields a nucleus-scaled homolog-searching tentacle.

Interplay of Rec8-mediated cohesion and Red1/Mek1kinase for establishment of homolog bias

Mcd1 substitutes efficiently for Rec8 in promoting sister bias; further, Red1/Mek1 kinase can overcome this effect as effectively as it does that of Rec8. Mcd1 also substitutes effectively for Rec8 for sister chromatid arm cohesion. Thus, Rec8− mediated sister bias is likely promoted by cohesion per se. This meiotic role of Rec8 is analogous to recently-described Mcd1 roles in promoting sister bias for recombinational repair of DSBs in non-meiotic cells (Introduction).

Meiosis requires that cohesion be robust globally, to ensure regular homolog pairing during prophase and homolog segregation at MI (Introduction). We infer that meiotic components Red1/Mek1kinase are required to counteract this cohesion locally, in the vicinity of recombinational interactions, thereby opening up the possibility for actual implementation of homolog bias via other meiosis-specific features. In this role, Red1/Mek1 likely works together with Hop1, the third yeast meiotic axis component. Hop1 interacts closely with Red1/Mek1, physically, cytologically, and functionally with respect to several activities, including homolog bias: in a hop1Δ mutant, at HIS4LEU2, only IS-dHJs are observed, to the exclusion of IH-dHJs (Schwacha and Kleckner, 1994) exactly as in red1Δ (above). This role of Hop1/Red1/Mek1kinase is the only role for these proteins in homolog bias establishment because corresponding mutations have no effect on establishment if Rec8/cohesion is absent.

The effect of Red1/Mek1kinase on Rec8-mediated cohesion could occur prior to, concomitant with, or after DSB formation, by any of several possible mechanisms. An early effect is supported by our finding that Rec8 and Red1/Mek1 play multiple roles, sometimes interactively, prior to/concomitant with DSB formation, i.e. for sister cohesion, for the levels and timing of DSBs, and in early formation of distinct spatial domains.

Homolog bias is likely implemented by components of pre/post-DSB recombinosomes, including Dmc1 (Sheridan and Bishop, 2006). Thus: precondition effects (Figure 7A) likely reflect a layer of structural control that is superimposed upon recombinosome-mediated events.

Our findings exclude several previous models for establishment of homolog bias. (i) With respect to Introduction Model 1: cohesion-mediated sister cohesion does not promote bias; rather it inhibits bias; also, Red1/Mek1kinase does not promote sister cohesion; rather it counteracts cohesion (see also Terentyev et al., 2010). (ii) It was proposed that Mek1-mediated phosphorylation of Rad54 plays a role in homolog bias (Niu et al., 2009). The present study suggests that the only role of Red1/Mek1kinase is to counteract Rec8-mediated cohesion. Mek1 phosphorylation of Rad54 may be important primarily for DNA damage “checkpoint” responses, e.g. in dmc1Δ where Mek1/Rad54 interactions were examined; indeed, a non-phosphorylatable rad54 mutant has no phenotype in WT meiosis (Niu et al., 2009). (iii) A recent report asserts that Mek1 mediates homolog bias independent of Rec8 (Callender and Hollingsworth, 2010). However, that study examined only progression of DSBs (which we show here is not correlated with partner choice), and did not examine whether progressing DSBs ended up in IH or IS interactions.

Maintenance of bias during CO recombination

For homolog bias maintenance, Rec8 is required and Mcd1 does not effectively substitute. Thus, meiosis-specific Rec8 functions are involved. Such roles might still be cohesion-related, or not. Intriguingly, Red1/Mek1kinase may work together with Rec8 for maintenance of bias (despite working in opposition to Rec8 during bias establishment). Similarly, Red1/Mek1kinase is implicated in promoting sister cohesion (despite also counteracting its inhibitory effects). Perhaps Red1/Mek1 and Rec8 roles for bias maintenance both reflect meiotic cohesion-favoring effects.

Maintenance of homolog bias is required specifically during CO recombination. Perhaps this is because CO recombination, but not NCO recombination, involves accompanying local exchange of individual chromatid axes (Introduction), and thus is more dependent on sister stabilization factors to maintain overall chromosome integrity during disruptive recombinational transitions (Storlazzi et al., 2008).

Establishment and maintenance of homolog bias via programmed quiescence and release of first- and second-DSB ends

During CO recombination, the two ends of each DSB interact with a partner duplex in ordered sequence (Introduction; Figure 7B). A “first” DSB end engages the partner in stable strand invasion (SEI-formation), then primes DNA extension synthesis and resultant formation of pre-dHJs. After pre-dHJ formation, this end is captured into the developing recombination complex by single-strand annealing. Apparently, during the intervening period, the second end remains associated with its sister, at both the DNA and axis levels (Introduction). This “ends-apart” scenario has further implications. (i) At the time of DSB formation, both DSB ends would be sister-associated. (ii) The first DSB end would be released from this association to permit interaction with a homolog chromatid. (iii) The “second” DSB end must remain biochemically quiescent while the first DSB end progresses. (iv) The second DSB end must also eventually be released from its sister to permit its capture into the recombination complex, during the SEI-to-dHJ transition, which occurs at early/mid-pachytene when SC is fully formed (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001). Since early/mid pachytene is an important global transition point for meiosis (Kleckner et al., 2004), release of quiescence could be a regulated event, which in turn would imply that quiescence itself is specifically programmed.

In correspondence to these implications (Figure 7B): (i) Sister-association of DSB ends is supported by our finding that cohesin Rec8 is relevant to events prior to and during DSB formation as well as immediately ensuing homolog bias.

(ii) Rec8/cohesion concomitantly promotes sister bias and inhibits use of the homolog. Perhaps it inhibits release of the first DSB end from its sister. Red1/Mek1kinase would then counteract this inhibition, making first end release possible, thereby satisfying preconditions for meiotic homolog bias. Recombinosome components would then ensure that the released end selects a homolog partner rather than its sister.

(iii) Rec8 could mediate maintenance of bias at the SEI-to-dHJ transition by mediating second-end quiescence. The events that normally give rise to in IH-dHJ are initiated at the first/homolog-associated DSB end (above). If these same events initiated, instead, at the second, sister-associated DSB end, the consequence would be formation of an IS-dHJ rather than an IH-dHJ (Figure 7C). The rec8Δ phenotype of loss of bias at the SEI stage can be explained, and in such a way as to give a 1:1 IH:IS dHJ ratio, if Rec8-mediated second-end quiescence would be defective such that pre-dHJ formation can be initiated with equal probability on either end. Red1/Mek1kinase might also contribute to second-end quiescence (above).

Initiation of pre-dHJ formation at both ends of the same DSB seems to be quite rare. Such events would yield MCJMs (Oh et al., 2007). While somewhat elevated in Rec8− strains, MCJMs are not dramatically prominent (K.K. unpublished). To explain this and other features of the data we suggest that communication between the two DSB ends, via a recombination intermediate that spans the SC (Storlazzi et al., 2010), may ensure that initiation of pre-dHJ formation (i.e. initiation 3’ extension synthesis) can initiate on only one of the two ends of any given DSB. In WT, Rec8 acts to favor initiation at the homolog-associated end; in Rec8−, this bias is lost. Also, the Rec8− phenotype is probably not explained by a failure to resolve MCJMs, because resolution-defective mutants still exhibit reasonable homolog bias (IH:IS dHJ = 3:1; e.g. Oh et al., 2007).

(iv) Modulation of Rec8-mediated sister association would be required for second-end release (Figure 7B).

Programmed quiescence and release of the second DSB end also explains other findings (Figure 7B). (i) Yeast encodes both Dmc1, a meiosis-specific RecA homolog implicated specifically in IH interactions, and Rad51, the general RecA homolog; meiosis also specifies a direct inhibitor of Rad51, Hed1; and it is proposed that Dmc1 binds to the first DSB end while Rad51 binds to the second DSB end (Hunter, 2006; Sheridan and Bishop, 2006). Thus: a key role of Rad51/Hed1 could be to promote second end quiescence. Accordingly, a rad52 allele specifically defective in abundant loading of Rad51 confers the same 1:1 IH:IS dHJ ratio as a Rec8− mutant (Lao et al., 2008).

(ii) Components of preDSB recombinosomes, e.g. Rec102 in yeast and Spo11 transesterase in several organisms, remain on the chromosomes after DSB formation, into pachytene; further Rec102 is released abruptly, specifically at early/mid-pachytene, i.e. at the time of second-end release (Kee et al, 2004; Romanienko and Camerini-Otero, 2000). preDSB recombinosome components may remain bound (at the second DSB end) in order to mediate second-end quiescence.

(iii) Retention of a Rad51-mediated second end/sister interaction leaves open the possibility for return to a mitotic-like inter-sister DSB repair reaction if meiotic IH recombination goes awry, with IS events triggered by activation of second-end release. Accordingly: (i) in mouse, DSBs that lack an homologous partner sequence remain unresolved until early-mid pachytene; and (ii) in allohexaploid wheat, recombinational interactions between homeologous sequences are specifically lost, presumptively to IS repair, at this same stage (Mahadevaiah, 2004; Zickler and Kleckner, 1999).

Establishment of DSB/homolog connections via a nucleus-scaled homology-searching tentacle

Tethered-loop axis complexes are clearly present shortly after DSB formation by both molecular and cytological criteria (Blat et al., 2002; Zickler and Kleckner, 1999). It is less clear whether this association is created prior to DSB formation, concomitant with development of axial structure, or after DSB formation, with post-DSB complexes associating with already-developed structure. One prior finding points to pre-DSB recombinosome/axis association: DSBs and DSB-associated Dmc1 complexes occur, preferentially, half way between flanking axis association sites, rather than randomly with respect to those sites (Blat et al., 2002; Kuguo et al, 2009; F.Klein, personal communication). Thus: developing recombination complexes and axis-association sites must communicate prior to DSB formation. Here we provide additional evidence to this effect. (1) All known meiotic axis components are required for maximal levels of DSBs including Rec8 as shown here and elsewhere. (2) Red1/Rec8 interplay is important for the timing of DSB formation. (3) Red1 and Rec8 localize in abundant domains that exhibit longitudinal linearity before DSBs form.

Together, these results support a picture in which DSBs occur in tethered-loop axis complexes that contain both sisters, with DSBs occurring preferentially mid-way between flanking axis-association sites (Figure 1E, 7D). If so, release of a first DSB end (above) will release a tentacle whose length is approximately half the length of a chromatin loop (Figure 7D). Budding yeast loops are 10–15kb in length (Blat et al., 2002). A released tentacle would thus be ~7kb, i.e. ~0.3 or ~2µm of nucleosomal filament or naked DNA respectively. These lengths are similar to the diameter of the meiotic yeast nucleus, ~2 µm. Release of a tentacle would thus permit a DSB to search for a homologous partner without the dramatic stirring forces that would otherwise be required to bring DSB ends in contact with homologous partners. Recent findings support long-distance homology recognition (Storlazzi et al., 2010). Importantly, chromatin loop size scales with genome size (Zickler and Kleckner, 1999; Kleckner, 2006), which in turn scales with nucleus size. Thus, DSB formation should universally release a nucleus-scaled homology-searching tentacle (Figure 7D).

Structure-mediated control of recombinational progression

Previous considerations suggest that meiotic chromosome structure plays a central role in controlling the timing of recombination progression in WT meiosis (e.g. Börner et al., 2008). Our results suggest that Red1/Mek1 and Rec8 are involved in "putting the brakes" on recombination progression and that they act via distinct effects. As a result, when both types of components are absent, biochemical events proceed extremely rapidly.

Red1/Mek1 impedes recombination in both WT and Rec8− strains. Further, Mek1 is Rad53-related, and Rad53 is the primary downstream target of ATR, the replication and DSB repair regulatory surveillance kinase. Thus, Red1/Mek1 might monitor local developments within individual recombinational interactions, ensuring that each biochemical step is completed and new components properly loaded before the next biochemical step can occur (Schwacha and Kleckner, 1997). These effects likely also involve Pch2 (Börner et al., 2008). How might Rec8 participate in progression timing? Perhaps Rec8 responds to global regulatory signals derived from the cell cycle, licensing major transitions nucleus-wide. Such effects would link recombination progression to overall cell status and periodically reinforce nucleus-wide synchrony. Together, Red1/Hop1/Mek1 and Rec8 would integrate local "surveillance" signals and global cell cycle-related signals to control progression at both levels.

Domainal differentiation and evolution of the meiotic inter-homolog interaction program

Red1 and Rec8 play functionally distinct roles in every process examined here: sister association and several aspects of recombination including (i) opposing effects for homolog bias establishment; (ii) cooperative roles for maintenance of homolog bias; and (iii) distinct roles for regulation of recombination progression. However, in a mutant lacking both Rec8 and Red1, recombination is still executed normally: initiation, establishment of homolog bias and CO/NCO differentiation occur; CO recombination proceeds via SEIs and dHJs; and CO and NCO products are both formed efficiently. Thus: these structural components only modulate basic biochemical events, which are directly executed by other (i.e. recombinosome) components.

Red1 and Rec8 tend to be enriched in spatially distinct domains along chromosomes on a per-cell basis. We propose that Red1 and Rec8 carry out their distinct but coordinated roles (for cohesion, homolog bias and recombinational progression) via corresponding spatially distinct domains. We proposed previously that meiotic chromosomes might comprise two functionally and structurally different types of regions: interaction domains and stabilization domains, which would occur alternately along chromosomes (Zickler and Kleckner, 1999). Interaction domains would encourage structural destabilizations needed for pairing and recombination; stabilization domains would provide structural snaps that counteract such destabilization, thereby maintaining chromosome integrity. Red1−rich regions (which are also Hop1-rich regions; Börner et al., 2008) and Rec8-rich regions could be these two types of domains. In support of this idea: (i) CO sites are associated primarily with Red1/Hop1 domains (Joshi et al., 2009); and (ii) Red1 is more strongly required for DSB formation and, separately, to ensure that a DSB gives an IH product (i.e. homolog bias) in domains where it is more abundant than in domains where it is less abundant (Blat et al., 2002). Domainal recombinosome/axis organization could arise easily if each emerging pre-DSB recombination complex tends to nucleate development of a surrounding Red1 domain, concomitantly constraining positions of Rec8 domains.

In the context of domainal control, a specific idea regarding homolog bias emerges. Red1 domains might comprise zones in which, because of they way they developed, Rec8-mediated cohesion is relatively depleted and where, additionally, Red1/Mek1 mediates another type of sister association. This alternative mode would compensate for the deficit of Rec8 but, unlike cohesin-mediated cohesion, would be susceptible to recombination-directed destabilization. Rec8 domains, in contrast, would comprise zones of cohesin-mediated cohesion that is robust and insensitive to recombinosome-directed effects. This model can explain how Red1 could act both positively and negatively for sister cohesion. Further, when Red1 is absent, recombinosome-nucleated formation of Red1 domains would not occur, and unconstrained loading of Rec8 would confer sister bias.

We previously proposed that meiosis evolved by integration of elements from mitotic DSB repair and elements of late-stage mitotic (G2-anaphase) chromosome morphogenesis, with functional linkage achieved via tethering of recombinosomes to structural axes (Kleckner et al., 2004; Kleckner, 1996). These two sets of evolutionary inputs could be implemented via spatial and functional domainal organization along the chromosomes.

Red1/Hop1/Mek1kinase domains would mediate effects evolved from mitotic DSB repair, modulating execution of recombination and controlling local progression (above), while Rec8 domains would mediate effects evolved from modulation of cohesion status that normally occur during the latter stages of the mitotic cell cycle.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Time Courses

All strains are isogenic heterothallic SK1 derivatives (Extended Experimental Procedures). Proper synchronization of a meiotic culture is critical for these studies. Thus far, only sporulation in liquid medium allows optimal synchrony of the population. For 33°C analysis, cells were kept at 30°C through t = 2.5 hours with shift to 33°C occurring thereafter (for rationale, see Börner et al., 2004). For analysis of mutants containing mek1as, a single culture was synchronized and divided into two identical sporulation cultures then in one of the two cultures, Mek1 kinase activity was inhibited by addition of fresh 1 µM 1-NA-PP1 (USBiological) (Niu et al., 2005).

DNA Physical Analysis

Strains for recombination analyses are homozygous for leu2::hisG, ura3 (ΔPst1-Sma1), ho::hisG, nuc1::HPHMX4 with MATα/MATa HIS4::LEU2-(BamHI)/his4X::LEU2-(NgoMIV)-URA3. Chromosomal DNA preparation and physical analysis were performed as described previously (Schwacha and Kleckner, 1994; Hunter and Kleckner, 2001). For DNA physical analysis in 2D gels, genomic DNA was digested with XhoI and loaded onto an agarose gel lacking ethidium bromide in TBE. Gels were stained in TBE containing ethidium bromide, and portions of lanes containing DNA species of interest were cut out and placed across a 2D apparatus gel tray at 90° degree to the direction of electrophoresis. Agarose containing ethidium bromide in TBE was poured around the gel slices and allowed to solidify. Electrophoresis in the second dimensional gel was performed at 4°C in pre-chilled TBE containing ethidium bromide. For CO/NCO assays, DNA digested with both XhoI and NgoMIV was analyzed on 1D gel electrophoresis. For all analyses, DNA species were quantified by phosphorimager analysis, with care to avoid saturation of detection (Extended Experimental Procedures; Hunter and Kleckner, 2001; Oh et al., 2007).

Microscopy

Samples for FACS, sister cohesion, and divisions were fixed in 40% ethanol and 0.1 M sorbitol, then stored at −20°C. FACS and divisions were performed as described in Cha et al., 2000 except that Sytox Green (Molecular Probes) was used to specifically stain DNA rather than propidium iodide. For cohesion analysis cells were spun down, resuspended in 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 µg/ml DAPI and visualized immediately. Immunofluorescence was performed on chromosome spreads. Primary antibodies were mouse monoclonal anti-myc, rabbit anti-Red1, and goat polyclonal anti-Zip1 (Santa Cruz).

Additional experimental details are described in the Supplemental Information.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kleckner laboratory members and many other colleagues for helpful comments; A.Amon for Tet repressor/operator and pREC8-MCD1 strains; and N.Hollingsworth for mek1as. Research was supported by grant N.I.H. GMS-044794 to N.K.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bailis JM, Roeder GS. Synaptonemal complex morphogenesis and sister-chromatid cohesion require Mek1-dependent phosphorylation of a meiotic chromosomal protein. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3551–3563. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blat Y, Protacio RU, Hunter N, Kleckner N. Physical and functional interactions among basic chromosome organizational features govern early steps of meiotic chiasma formation. Cell. 2002;111:791–802. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börner GV, Barot A, Kleckner N. Yeast Pch2 promotes domainal axis organization, timely recombination progression, and arrest of defective recombinosomes during meiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:3327–3332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711864105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börner GV, Kleckner N, Hunter N. Crossover/noncrossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell. 2004;117:29–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzymek M, Thayer NH, Oh SD, Kleckner N, Hunter N. Double Holliday Junctions are Intermediates of DNA Break Repair. Nature. 2010;1464:937–941. doi: 10.1038/nature08868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callender TL, Hollingsworth NM. Mek1 suppression of meiotic double-strand break repair is specific to sister chromatids, chromosome autonomous and independent of Rec8 cohesin complexes. Genetics. 2010;185:771–782. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.117523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha RS, Weiner BM, Keeney S, Dekker J, Kleckner N. Progression of meiotic DNA replication is modulated by interchromosomal interaction proteins, negatively by Spo11p and positively by Rec8p. Genes Dev. 2000;14:493–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covo S, Westmoreland JW, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. Cohesin Is limiting for the suppression of DNA damage-induced recombination between homologous chromosomes. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Martínez LA, Giménez-Abián JF, Clarke DJ. Chromosome cohesion - rings, knots, orcs and fellowship. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:2107–2114. doi: 10.1242/jcs.029132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijpe M, Offenberg H, Jessberger R, Revenkova E, Heyting C. Meiotic cohesin REC8 marks the axial elements of rat synaptonemal complexes before cohesins SMC1beta and SMC3. J. Cell Biol. 2003;160:657–670. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb T, Lichten M. Frequent and Efficient Use of the Sister Chromatid for DNA Double-Strand Break Repair During Budding Yeast Meiosis. PLoS Biology. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000520. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidinger-Pauli JM, Mert O, Davenport C, Guacci V, Koshland D. Systematic reduction of cohesin differentially affects chromosome segregation, condensation, and DNA repair. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:957–963. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter N. Meiotic Recombination. In: Aguilera A, Rothstein R, editors. Molecular Genetics of Recombination. Heidelberg: Topics in Current Genetics, Springer-Verlag; 2006. pp. 381–442. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter N, Kleckner N. The single-end invasion: an asymmetric intermediate at the double-strand break to double-holliday junction transition of meiotic recombination. Cell. 2001;106:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GH, Franklin FC. Meiotic crossing-over: obligation and interference. Cell. 2006;126:246–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi N, Barot A, Jamison C, Börner GV. Pch2 links chromosome axis remodeling at future crossover sites and crossover distribution during yeast meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee K, Protacio RU, Arora C, Keeney S. Spatial organization and dynamics of the association of Rec102 and Rec104 with meiotic chromosomes. EMBO J. 2004;23:1815–1824. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleckner N. Meiosis: how could it work? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1996;93:8167–8174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleckner N, Zickler D, Jones GH, Dekker J, Padmore R, Henle J, Hutchinson J. A mechanical basis for chromosome function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101:12592–12597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402724101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleckner N. Chiasma formation: chromatin/axis interplay and the role(s) of the synaptonemal complex. Chromosoma. 2006;115:175–194. doi: 10.1007/s00412-006-0055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein F, Mahr P, Galova M, Buonomo SB, Michaelis C, Nairz K, Nasmyth K. A central role for cohesins in sister chromatid cohesion, formation of axial elements, and recombination during yeast meiosis. Cell. 1999;98:91–103. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80609-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugou K, Fukuda T, Yamada S, Ito M, Sasanuma H, Mori S, Katou Y, Itoh T, Matsumoto K, Shibata T, et al. Rec8 guides canonical Spo11 distribution along yeast meiotic chromosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:3064–3076. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao JP, Oh SD, Shinohara M, Shinohara A, Hunter N. Rad52 promotes post invasion steps of meiotic double-strand-break repair. Mol. Cell. 2008;29:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latypov V, Rothenberg M, Lorenz A, Octobre G, Csutak O, Lehmann E, Loid lJ, Kohli J. Roles of Hop1 and Mek1 in meiotic chromosome pairing and recombination partner choice in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1570–1581. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00919-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Amon A. Role of Polo-like kinase CDC5 in programming meiosis I chromosome segregation. Science. 2003;300:482–486. doi: 10.1126/science.1081846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevaiah SK, Turner JM, Baudat F, Rogakou EP, de Boer P, Blanco-Rodríguez J, Jasin M, Keeney S, Bonner WM, Burgoyne PS. Recombinational DNA double-strand breaks in mice precede synapsis. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:271–276. doi: 10.1038/85830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone RE, Haring SJ, Foreman KE, Pansegrau ML, Smith SM, Houdek DR, Carpp L, Shah B, Lee KE. The signal from the initiation of meiotic recombination to the first division of meiosis. Eukaryot. Cell. 2004;3:598–609. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.3.598-609.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Perez E, Villeneuve AM. HTP-1-dependent constraints coordinate homolog pairing and synapsis and promote chiasma formation during C. elegans meiosis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2727–2743. doi: 10.1101/gad.1338505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini E, Diaz RL, Hunter N, Keeney S. Crossover homeostasis in yeast meiosis. Cell. 2006;126:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H, Wan L, Baumgartner B, Schaefer D, Loidl J, Hollingsworth NM. Partner choice during meiosis is regulated by Hop1-promoted dimerization of Mek1. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:5804–5818. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H, Li X, Job E, Park C, Moazed D, Gygi SP, Hollingsworth NM. Mek1 kinase is regulated to suppress double-strand break repair between sister chromatids during budding yeast meiosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:5456–5467. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00416-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H, Wan L, Busygina V, Kwon Y-H, Allen JA, Li X, Kunz RC, Kubota K, Wang B, Sung P, et al. Regulation of meiotic recombination via Mek1-mediated Rad54 phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. 2009;36:393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SD, Lao JP, Hwang PY, Taylor AF, Smith GR, Hunter N. BLM ortholog Sgs1 prevents aberrant crossing over by suppressing formation of multichromatid joint molecules. Cell. 2007;130:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmore R, Cao L, Kleckner N. Temporal comparison of recombination and synaptonemal complex formation during meiosis in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1991;66:1239–1256. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penkner A, Prinz S, Ferscha S, Klein F. Mnd2, an essential antagonist of the anaphase-promoting complex during meiotic prophase. Cell. 2005;120:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanienko PJ, Camerini-Otero RD. The mouse Spo11 gene is required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:975–987. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Moran E, Santos JL, Jones GH, Franklin FC. ASY1 mediates AtDMC1-dependent interhomolog recombination during meiosis in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2220–2233. doi: 10.1101/gad.439007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha A, Kleckner N. Identification of joint molecules that form frequently between homologs but rarely between sister chromatids during yeast meiosis. Cell. 1994;76:51–63. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha A, Kleckner N. Interhomolog bias during meiotic recombination: meiotic functions promote a highly differentiated interhomolog-only pathway. Cell. 1997;90:1123–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80378-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan S, Bishop DK. Red-Hed regulation: recombinase Rad51, though capable of playing the leading role, may be relegated to supporting Dmc1 in budding yeast meiosis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1685–1691. doi: 10.1101/gad.1447606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storlazzi A, Xu L, Cao L, Kleckner N. Crossover and noncrossover recombination during meiosis: timing and pathway relationships. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1995;92:8512–8516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storlazzi A, Tesse S, Ruprich-Robert G, Gargano S, Pöggeler S, Kleckner N, Zickler D. Coupling meiotic chromosome axis integrity to recombination. Genes Dev. 2008;22:796–809. doi: 10.1101/gad.459308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storlazzi A, Gargano S, Ruprich-Robert G, Falque M, David M, Kleckner N, Zickler D. Recombination Proteins Mediate Meiotic Spatial Chromosome Organization and Pairing. Cell. 2010;141:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terentyev Y, Johnson R, Neale MJ, Khisroon M, Bishop-Bailey A, Goldman AS. Evidence that MEK1 positively promotes interhomologue double-strand break repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4348–4360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D, Stahl F. Genetic control of recombination partner preference in yeast meiosis: isolation and characterization of mutants elevated for meiotic unequal sister-chromatid recombination. Genetics. 1999;153:621–641. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H-Y, Ho H-C, Burgess SM. Mek1 kinase governs outcomes of meiotic recombination and the checkpoint response. Current Biology. 2010;20:1707–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickler D, Kleckner N. Meiotic chromosomes: integrating structure and function. Ann. Rev. Genet. 1999;33:603–754. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.