Abstract

Relocation of euchromatic genes near the heterochromatin region often results in mosaic gene silencing. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, cells with the genes inserted at telomeric heterochromatin-like regions show a phenotypic variegation known as the telomere-position effect, and the epigenetic states are stably passed on to following generations. Here we show that the epigenetic states of the telomere gene are not stably inherited in cells either bearing a mutation in a catalytic subunit (Pol2) of replicative DNA polymerase ɛ (Pol ɛ) or lacking one of the nonessential and histone fold motif-containing subunits of Pol ɛ, Dpb3 and Dpb4. We also report a novel and putative chromatin-remodeling complex, ISW2/yCHRAC, that contains Isw2, Itc1, Dpb3-like subunit (Dls1), and Dpb4. Using the single-cell method developed in this study, we demonstrate that without Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC, the epigenetic states of the telomere are frequently switched. Furthermore, we reveal that Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC function independently: Pol ɛ operates for the stable inheritance of a silent state, while ISW2/yCHRAC works for that of an expressed state. We therefore propose that inheritance of specific epigenetic states of a telomere requires at least two counteracting regulators.

The eukaryotic genome is packaged into either euchromatin or heterochromatin. Heterochromatin is defined cytologically as the fraction of the genome that is constitutively condensed throughout the cell cycle (25) and corresponds to regions of highly repeated DNA such as centromeres or telomeres (13). In this region, DNA-mediated metabolisms, such as transcription, recombination, and replication, are generally inactive. In the case of chromosomal DNA replication, heterochromatin replicates in late S phase, while euchromatic regions replicate in early S phase (27).

In a simple eukaryote, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, although its genome is too small to define heterochromatin cytologically, the HMR and HML cryptic mating-type loci, ribosomal DNA (rDNA) repeats, and telomeres are loci affected by silencing (22, 26, 52). Like heterochromatin in higher eukaryotes, HM loci and telomeric regions are replicated in late S phase (17, 47), and these silenced regions are associated with histone hypoacetylation (5, 8, 23, 39). The silencing process has three phases, establishment or assembly of a silent chromatin, its maintenance through the cell cycle, and its inheritance to daughter cells, as described by Lau et al. (35). Factors that are involved in these phases of silencing are identified from studies of mutant strains that lose silencing. Mutations in SIR2, SIR3, and SIR4 eliminate the silencing at HM loci, whereas mutations in SIR1 partially reduce it, because Sir1 is required only for establishment, whereas Sir2, Sir3, and Sir4 are required for both establishment and maintenance (45). Sir2, Sir3, and Sir4 form a Sir complex at HM loci (40). The Sir complex does not directly bind DNA but rather interacts with DNA-binding factors, including Rap1, Orc, and Abf1, that bind to silencer DNA elements sandwiching HM loci (28). rDNA encoding 35S rRNA consists of 100 to 200 times the number of tandem repeats in a 9-kb unit on chromosome XII and is localized in the nucleolus. In rDNA silencing, the RENT complex, which is distinct from the Sir complex and which consists of Sir2, Net1, and Cdc14, represses homologous recombination as well as transcription of transgenes in the rDNA repeats (50, 55).

When a wild-type gene is located near a telomere in budding yeast, it is subjected to telomere position effect (TPE) variegation, which provides heritable silent and expressed states and reversible switching between the epigenetic states (22). The silent state of the telomeric gene is attributable to a heterochromatin-like structure that consists of several proteins, such as Sir proteins and hypoacetylated histones, that spread from the telomeric ends (1, 23). The Sir complex but not Sir1 interacts with tandemly reiterated Rap1 molecules bound to the telomere repeat sequence and spreads into subtelomeric DNA to form a silent heterochromatin-like structure. Spreading of Sir proteins into the HM loci and subtelomeric DNA is probably facilitated by the interaction of Sir3/Sir4 with hypoacetylated histones H3/H4 and Sir2, a NAD-dependent histone deacetylase (14, 23, 24, 54), and blocked by Dot1-catalyzed methylation of histone H3 (33, 36, 42).

For the maintenance and inheritance of silencing, a silent state must be propagated when chromosomal DNA is replicated. A previous study showed that the trans activator Ppr1 overcomes a silent state of the URA3 gene integrated near telomere in G2/M-phase arrested cells, but not in G1- or early S-phase arrested cells (2), suggesting that progression through the S phase is required for switching from a silent to an expressed state in TPE. Furthermore, Zhang et al. (63) recently showed that mutant forms of the replication protein PCNA are defective in silencing as well as in interacting with CAF-1, a replication-coupled chromatin assembly factor, and they suggested that DNA replication machinery is linked to chromatin assembly and silencing.

One of the replicative polymerases, DNA polymerase ɛ (Pol ɛ) (56), is composed of a catalytic-subunit Pol2, Dpb2, Dpb3, and Dpb4 in S. cerevisiae, and the subunit composition of Pol ɛ is evolutionarily conserved in eukaryotes (37, 38). Although Pol2 and Dpb2 are essential for DNA replication (56), the histone fold motif-containing subunits, Dpb3 (3) and Dpb4 (44), are dispensable and their function remains unclear. A counterpart of Dpb4, p17 in human cells, was recently reported to be a subunit of not only Pol ɛ but also CHRAC (chromatin accessibility complex) (38, 46). CHRAC consisting of ISWI, Acf1, and two small subunits was purified from Drosophila and human cells and shown to catalyze chromatin remodeling (12, 46). In budding yeast, a similar complex was reported to catalyze chromatin remodeling although small subunits had not been detected (19, 30, 31, 59).

Because several histone fold motif-containing proteins have been reported to interact with histones (10), we examined whether these nonessential subunits may play a role in chromatin configuration. Using the single-cell method, we found that deletions of Dpb3 and Dpb4 confer defects of TPE in different manners. This is because Dpb4 is shared by Pol ɛ and the ISW2/CHRAC complex, a putative chromatin remodeling factor counteracting Pol ɛ for TPE. From these observations, we propose a model to maintain chromatin structure when chromosomal DNA is replicated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

The yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. YPDA (YPD with 0.04 g of adenine/liter) and synthetic complete (SC) media were used as previously described (22), except that 100 mg of adenine/liter was added but leucine was not.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| YTI249 | MATaade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3 trp1-1 ura3-1 VIIL-adh4::URA3-TEL VR::ADE2-TEL (W303 background) |

| YTI456 | YTI249 itc1Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI452 | YTI249 isw2Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI442 | YTI249 dls1Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI250 | YTI249 dpb3Δ-1::KanMX6 |

| YTI457 | YTI250 itc1Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI453 | YTI250 isw2Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI443 | YTI250 dls1Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI266 | YTI249 dpb4Δ-1::HIS3 |

| YTI458 | YTI266 itc1Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI454 | YTI266 isw2Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI444 | YTI266 dls1Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI268 | YTI250 dpb4-1Δ::HIS3 |

| YTI258 | MATapol2-11 VIIL adh4::URA3-TEL VR::ADE2-TEL (W303 background) |

| YTI394 | YTI249 cac1Δ-1::LEU2 |

| YTI395 | YTI250 cac1Δ-1::LEU2 |

| YTI396 | YTI266 cac1Δ-1::LEU2 |

| YTI280 | MATabar1Δ::hisG ade2Δ::hisG can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3 trp1-1 ura3-1 (W303 background) |

| YTI448 | YTI280 VR::α2ADE2-TEL |

| YTI449 | YTI448 dpb3Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI450 | YTI448 dpb4Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI451 | YTI448 dls1Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI297 | MATaURA3 bar1Δ::hisG ade2Δ::hisG can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3 trp1-1 (W303 background) |

| YTI468 | YTI297 dpb3Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI469 | YTI297 dpb4Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI470 | YTI297 dls1Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI279 | MATaADE2 bar1Δ::hisG can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3 trp1-1 ura3-1 (W303 background) |

| YTI471 | YTI279 dpb3Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI472 | YTI279 dpb4Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI473 | YTI279 dls1Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI312 | MATabar1Δ::hisG ade2Δ::hisG ura3Δrvs can1-100 his3-11,15 his4 leu2-3 trp1-1 VIIL-adh4::URA3-TEL VR::ADE2-TEL (W303 background) |

| YTI446 | YTI312 sir3::SIR3-13MYC-KanMX6 |

| YTI464 | YTI446 dpb3Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI465 | YTI446 dpb4Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI466 | YTI446 dls1Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI467 | YTI446 sir2Δ::CgTRP1 |

| YTI189 (BJ2168)a | MATaprc1-407 prb1-1122 pep4-3 leu2 trp1 ura3-52 gal2 |

| YTI367 | BJ2168 dpb4::DPB4-5FLAG |

| YTI460 | YTI367 itc1::ITC1-13MYC-KanMX6 |

| YTI461 | YTI367 isw2::ISW2-13MYC-KanMX6 |

| YTI369 | YTI367 dpb3Δ-1::KanMX6 |

| YTI458 | YTI367 dls1Δ::TRP1 |

| YTI365 | YTI189 dpb3::DPB3-5FLAG |

| YTI459 | YTI189 dls1::DLS1-5FLAG-TRP1 |

Strain designation used by Woontner et al. (61).

Plasmid construction.

YEp112-DPB3 was constructed by subcloning the BamHI-KpnI DPB3 fragment from YCp111-DPB3 into the BamHI-KpnI site of YEplac112 (20). YEp112-DPB4 was constructed by subcloning the BamHI-HindIII DPB4 fragment from pRS315DPB4 (gift of A. Sugino) into the BamHI-HindIII site of YEplac112. pUCDPB4 was constructed by subcloning the 2.2-kb BamHI-SphI DPB4 fragment generated by PCR into the BamHI-SphI site of pUC18. YEp112-DPB3DPB4 was constructed by subcloning the 1.7-kb BglII-SphI DPB4 fragment from pUCDPB4 into the BamHI-SphI site of YEp112-DPB3.

Assay for silencing of telomeric URA3 and ADE2.

To assay telomeric silencing, the strains with telomeric URA3 and ADE2 at the telomeres of the left arm of chromosome VII and the right arm of chromosome V, respectively, were used (strains listed in Table 1). All the strains harbor YCplac111 (LEU2), because cells used in this study (W303 background) show slightly slow growth on synthetic medium. To assay silencing of telomeric URA3, freshly grown yeast cells were taken from SC medium and diluted to a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/ml. Then, 10-fold serial dilutions (2 × 107 to 2 × 102 cells/ml) were made, and 5-μl cell aliquots from each of the dilutions were spotted onto SC, SC-Ura, and SC 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) plates. The inoculated plates were incubated at 25°C for 3 days (SC and SC-Ura plates) or 4 days (SC 5-FOA plates), and pictures were taken. To assay silencing of telomeric ADE2, about 100 yeast cells of each strain from SC medium were spread onto SC plates. The plates were incubated at 25°C for 10 days, and pictures were taken.

Single-cell telomeric silencing assay.

Cells (YTI448 and its isogenic derivatives) carrying the α2 gene at the right arm of chromosome V were freshly grown in YPDA medium, streaked onto YPDA agar containing α-factor, and incubated at 30°C for 4 h. Among the 200 cells from the culture, the population of shmoo cells was defined as the silenced cells (off cells). The off cells were incubated in the absence of α-factor at 30°C until they started to bud, when the cells were reexposed to α-factor and the morphology of their daughters was observed. Daughters of the budding cells from the original culture (on cells) were separated, and their morphology in the presence of α-factor was observed. Five batches of either 20 or 100 cells from each strain were used for the assay. To follow each generation (pedigree assay), the procedures for on and off cells were successively repeated for the original 20 cells. Although several a-specific genes are derepressed in itc1Δ and isw2Δ cells (49), the a1-α2 complex represses the haploid-specific genes and consequently makes cells insensitive to α-factor. Therefore, this assay is also useful for itc1Δ and isw2Δ cells.

Immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation was performed according to the methods described by Zachariae et al. (62) and Takayama et al. (58) by using an anti-Flag antibody (M2)-conjugated agarose and lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 300 mM KCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 0.005% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 1× complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Boehringer-Mannheim], 1% Sigma protease inhibitor [Sigma], 2 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM NaF, 0.4 mM Na3VO4, 0.5 mM Na-pyrophosphate) containing 5 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml. From the immunocomplex, the proteins were eluted by incubation with 100 μg of 3× Flag peptides (Sigma) per ml. Superose 6 column (Amersham Biotech) chromatography of the eluates was performed in the lysis buffer.

ChIP assay.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis was performed essentially as described in reference 29. DNA purified from whole-cell extracts or coprecipitated with anti-c-myc antibodies (MBL) was analyzed by PCR. Primers specific for URA3 (ura3F [5′-CGAAAGCTACATATAAGGAACGTGC-3′] and ura3R [5′-CCCATGTCTCTTTGAGCAATAAAGC-3′]) were used to amplify the fragments, which were resolved on 2% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. Quantification was carried out with a LumiVision Analyzer instrument (AISIN).

RESULTS

Pol ɛ is required for TPE.

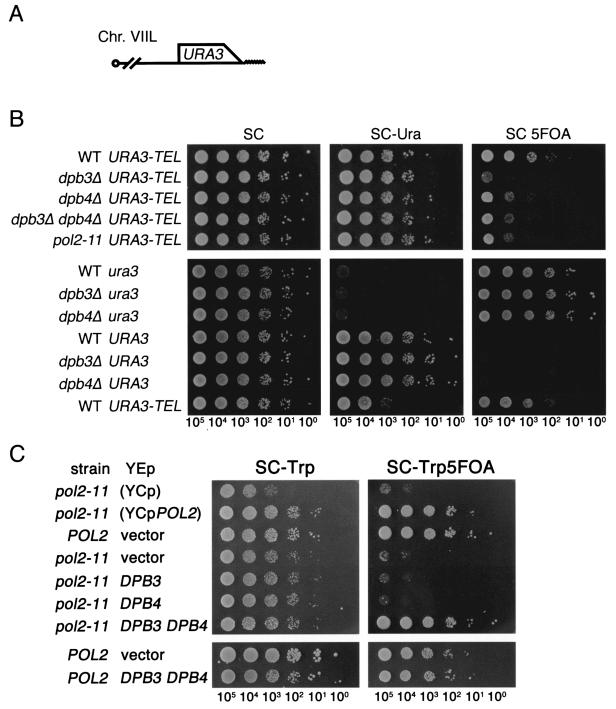

To determine whether Pol ɛ is involved in the maintenance of chromatin structure, we first investigated whether the deletions of DPB3 and DPB4 influence silencing of the URA3 gene integrated near the telomere of chromosome VII (22) (Fig. 1A). Expression of URA3 leads to cell growth on medium lacking uracil as well as to cell death on medium containing 5-FOA. In this assay, dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ mutant cells displayed partial expression of URA3, and this expression was more evident in dpb3Δ cells, while the expression of URA3 at the original locus was not affected (Fig. 1B, SC 5FOA). Moreover, the expression level in the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ double mutant was similar to that in dpb4Δ (Fig. 1B), indicating that the dpb4Δ mutation is epistatic to the dpb3Δ mutation. Furthermore, the pol2-11 mutation (9, 41) conferred partial expression of telomeric URA3 and this defect was suppressed by simultaneous introduction of high-copy-number DPB3 and DPB4 (Fig. 1C). Since Dpb3 and Dpb4 form a subassembly in vitro (15) and neither one of them suppressed the pol2-11 mutation (Fig. 1C), Dpb3 and Dpb4 seem to interact with Pol2 as a complex in vivo. This result further suggests that Dpb3, Dpb4, and Pol2 function for TPE as Pol ɛ.

FIG. 1.

DPB3 and DPB4 are involved in the regulation of TPE variegation. (A) Schematic diagram of the telomeric URA3 gene at chromosome VII. An open box and a wavy line represent the open reading frames of URA3 and the telomere, respectively. (B) Expression of URA3 at the telomere (VIIL::URA3-TEL) and internal chromosomal loci. To examine expression of the telomeric URA3 gene, the isogenic strains YTI249 (WT), YTI250 (dpb3Δ), YTI266 (dpb4Δ), YTI268 (dpb3Δ dpb4Δ) and YTI258 (pol2-11) were used. To examine expression of the URA3 gene at the internal chromosomal locus, the isogenic strains YTI279 (WT ura3), YTI471 (dpb3Δ ura3), YTI472 (dpb4Δ ura3), YTI297 (WT URA3), YTI468 (dpb3Δ URA3), and YTI469 (dpb4Δ URA3) were used. Cells freshly grown in SC medium were placed onto the indicated plates, after 10-fold serial dilution, and further incubated at 25°C for 3 days. The numbers under the photographs indicate the estimated number of cells placed on a spot. (C) Suppression of the pol2-11 mutation by increased dosage of DPB3 and DPB4. Wild-type (YTI249) and pol2-11 (YTI258) strains carrying a high-copy-number plasmid (YEplac112) (20) with DPB3, DPB4, or DPB3 DPB4 were subjected to a telomeric silencing assay as described for panel B. YCpPOL2 (YCp22POL2) (4) and YCp (YCplac22) (20) are CEN-based plasmids with and without POL2, respectively. Serial dilutions of cultures were inoculated onto the SC plates containing leucine and lacking tryptophan in the absence or presence of 5-FOA and incubated at 25°C. Note that the growth of pol2-11 mutant cells being slower than is apparent in panel B is probably attributable to the difference in the medium used for the plates. The numbers under the photographs indicate the estimated number of cells placed on a spot.

We also observed, in parallel, the expression of telomeric ADE2 on chromosome V (51), which shows phenotypic variegation of a silent (red) and an expressed (white) state by TPE and provides resultant red- and white-sector colonies (22) in wild-type cells (Fig. 2A). As expected, dpb3Δ cells formed white colonies as mutants defective in structural components of telomeric or subtelomeric chromatin (1) (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, dpb4Δ cells formed nonsectoring colonies with a solid light-pink color. Partial expression of ADE2 in each cell or a mixture of silent and expressed cells caused by frequent switching between alternative epigenetic states might confer a solid light-pink color. These possibilities were distinguished by the single-cell colony assay (see below).

FIG. 2.

Defects of TPE variegation in dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ, and dls1Δ mutations. (A) A colony color assay for cells carrying telomere-linked ADE2 (VR::ADE2-TEL). Freshly grown yeast cells of YTI249 (WT), YTI250 (dpb3Δ), YTI266 (dpb4Δ), YTI442 (dls1Δ), and YTI443 (dpb3Δ dls1Δ) strains were spread onto SC plates and further incubated at 25°C for 10 days. (B) High copy number of SIR3 does not enhance the telomere silencing in dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ cells. Freshly grown yeast cells of YTI249 (WT), YTI250 (dpb3Δ), and YTI266 (dpb4Δ) strains harboring a high-copy-number plasmid with the SIR3 gene (YEp-SIR3) were spread as described for panel A. Wild-type transformants with YEp-SIR3 form two types of sectoring colonies (red sector or white sector), and cells from each type colony were spread onto plates.

One of the replication proteins, PCNA, is suggested to be involved in the assembly of a silent chromatin (establishment) through CAF-1 (chromatin assembly factor 1) (63). To determine whether Dpb3 and Dpb4 function in the CAF-I-PCNA chromatin assembly pathway, we constructed double mutants bearing cac1Δ and either dpb3Δ or dpb4Δ. The CAC1 gene encodes one of three subunits of CAF-1. As shown in Table 2, dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ mutations enhanced the telomere silencing defect of cac1Δ cells, indicating that the roles of Dpb3 and Dpb4 in TPE are distinct from the CAF-I-PCNA chromatin assembly pathway.

TABLE 2.

Effect of dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ mutations with cac1Δ on telomere silencinga

| Allele | Frequency (SD)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| CAC1 | cac1Δ | |

| WT | 0.46 (±0.36) | 6.5 × 10−3 (±6.1 × 10−3) |

| dpb3Δ | 6.3 × 10−3 (±2.6 × 10−3) | 6.3 × 10−6 (±1.0 × 10−6) |

| dpb4Δ | 2.8 × 10−2 (±2.6 × 10−2) | 1.0 × 10−5 (±0.5 × 10−5) |

The dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ mutations in combinations with the cac1Δ mutation were tested for their effect on telomere silencing by determining the fraction of cells resistant to FOA. A telomeric silencing assay with the URA3 gene was performed with the isogenic YTI249 (WT), YTI250 (dpb3Δ), YTI266 (dpb4Δ), YTI394 (cac1Δ), YTI395 (cac1Δ dpb3Δ), and YTI396 (cac1 Δ dpb4Δ) strains. Values shown are from at least six independent experiments to determine the 5FOAR colonies of each strain.

It is also known that the increased dosage of Sir3 enhances the telomere silencing if the assembly of a silent chromatin is defective because Sir3 is a limiting factor for assembly of the Sir complex (48). We therefore introduced high-copy-number SIR3 into dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ cells and examined TPE using the colony color assay. While the wild-type cells harboring high-copy-number SIR3 frequently formed red-sectored colonies (enhancement of silencing), high-copy-number SIR3 did not affect the colony color of dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ cells (Fig. 2B), indicating that Sir3 is not a limiting factor in these cells.

Deletions of Dpb3 and Dpb4 show different switching patterns.

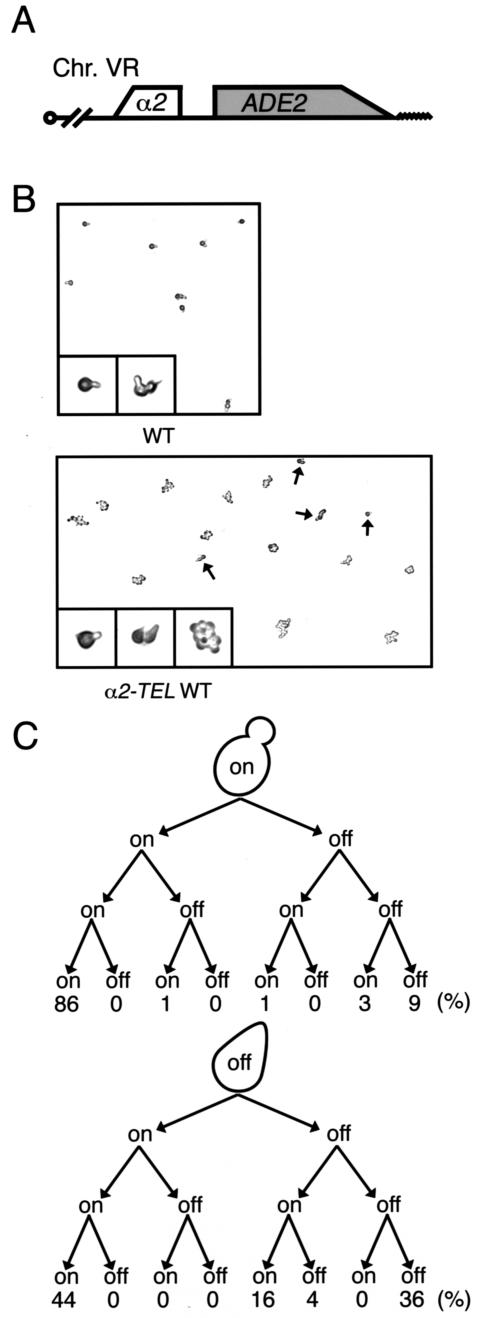

To monitor the switching between a silent and an expressed state in each cell division, we developed the single-cell telomeric silencing assay. In this assay, the α-factor sensitivity of a cells bearing the α2 gene (32) near the telomere of chromosome V (α2-TEL) (Fig. 3A) was used. When the telomere α2 gene is expressed (on), a cells (α2-TEL) behave like a/α diploid cells, which are insensitive to α-factor and consequently continue to divide (16, 45). Conversely, the α2-repressed cells (off) are sensitive to α-factor and arrest in the G1 phase with a shmoo shape (Fig. 3B). We first followed three successive divisions of each cell to examine whether the switching depends upon a previous event as a mating type switch (26) in budding yeast cells and found that cells switch their telomere states in an independent manner (Fig. 3C). Thus, we observed a single division of independent cells to measure their switching rate. We found that the switching rate from off to on (29%) is higher than that from on to off (4.3%) in wild-type cells (Table 3). In dpb4Δ cells, both switching rates increased, whereas in dpb3Δ cells the switching rate from off to on specifically increased. These results suggest that Dpb4 plays roles in switching in both directions, while Dpb3 is only involved in switching from off to on.

FIG. 3.

Single-cell assay of TPE. (A) Schematic diagram of telomeric ADE2 and α2 genes at chromosome V. Open boxes and a wavyline represent the open reading frames of the reporter genes and the telomere, respectively. (B) Expression of the telomeric α2 gene (VR::α2-TEL) in the YTI448 (α2-TEL WT) strain and the isogenic control YTI280 (WT) strain without α2-TEL. Cells were exposed to α-factor on YPDA plates at 30°C for 5 h. Pear-shaped cells, i.e., shmoos (cells with α2 unexpressed), and dividing cells (cells with α2 expressed) in each strain were magnified. The arrows indicate shmoo cells. (C) Pedigree assays of cells from strain YTI448 (WT) with α2 expressed (on) or silent (off). The procedure is described in detail in Materials and Methods.

TABLE 3.

Effect of dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ, and dls1Δ mutations on frequency of switching between silent and expressed states of telomere-linked α2a

| Genotype | Population of silenced cells (%) | Switching rate (%)b

|

Alternative switching rate (%)c

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On to off | Off to on | On to off | Off to on | ||

| WT α2-TEL | 21 | 4.3 (3.2-5.1) | 29 (23-38) | 24 | 16 |

| dpb4Δ α2-TEL | 26 | 20 (15-25) | 69 (56-75) | 30 | 19 |

| dpb3Δ α2-TEL | 10 | 4.2 (3.5-4.9) | 61 (53-70) | 19 | 20 |

| dls1Δ α2-TEL | 50 | 25 (20-30) | 27 (20-33) | 19 | 17 |

Each of the telomeric α2 strains, YTI448 (WT), YTI450 (dpb4Δ), YTI449 (dpb3Δ), and YTI451 (dls1Δ), or control strain YTI280 (WT without α2-TEL) was tested for its effect on telomeric silencing by the single-cell telomeric silencing assay. Note that all cells of WT, dpb4Δ, dpb3Δ, and dls1Δ strains without α2-TEL form shmoo on α-factor-containing medium.

Values are averages. Ranges are shown in parentheses.

Alternative switching values are the percentages of the mother cells generating on and off daughter cells among mothers generating switched daughter cells.

In this assay, the population of silenced cells among the dpb4Δ mutant cells was higher than that among the wild-type cells (Table 3), whereas the number of FOA-resistant cells (silenced cells) was reduced by the dpb4Δ mutation (Fig. 1B). This apparent disparity is probably caused by counting cells grown on FOA plates. To form a colony on an FOA plate, the cells should keep a silent state for several divisions. However, dpb4Δ cells were switching their epigenetic states at a high frequency (Table 3) and consequently hardly keeping a silent state.

The frequent switching between alternative epigenetic states also suggest that the solid-pink colony of dpb4Δ cells in the colony color assay (Fig. 2) is a mixture of silent and expressed cells. Furthermore, two daughter cells that originated from the same mother cell and individually showed a silent and an expressed state appeared (alternative switching [Table 3]), suggesting that the telomere states switch either in the daughter cells before budding or in the mother cell at or after DNA replication.

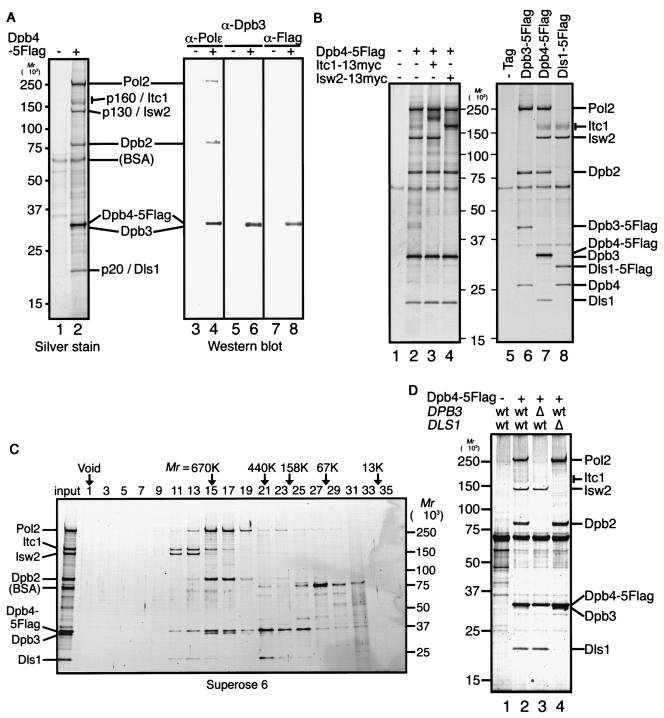

Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC share Dpb4.

The epistasis of dpb4Δ to dpb3Δ, together with different switching patterns in these mutants, suggested that Dpb4 is shared by Pol ɛ and an unknown complex that play counteracting roles for TPE. We therefore attempted to purify protein complexes containing Dpb4. For this purpose, we immunoprecipitated Dpb4 using cell extracts bearing 5Flag-tagged Dpb4 and an anti-Flag antibody. Dpb4-5Flag was eluted with 3× Flag peptide, and the eluates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Following silver staining, we observed seven distinct polypeptides (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 2). Western blot analysis with anti-Pol ɛ, anti-Dpb3, and anti-Flag antibodies identified Pol2, Dpb2, Dpb4-5Flag, and Dpb3 as p250, p80, p35, and p34, respectively (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 to 8). The remaining three polypeptides were identified by peptide mass fingerprinting analysis as Itc1 for p160, Isw2 for p130, and the product encoded by novel gene YJL065c for p20. These results were further confirmed by the introduction of a 13myc tag to Itc1 and Isw2 and a 5Flag tag to YJL065c, which resulted in a shifting up of the p160, p130, and p20 bands (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 to 4 and 8). Isw2 (59) is an ATPase subunit of the ISW2 ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex that is highly related to Drosophila ISWI (34). Itc1 (19) is also a subunit of the ISW2 chromatin-remodeling complex that contains an N-terminal WAC (WSTF/Acf1/cbp146) motif (6) that may be responsible for the functions of the ISWI complexes. YJL065c encodes a histone fold motif-containing polypeptide that has 31% identity (49% similarity) to Dpb3 over 151 amino acids (data not shown), which we named DLS1 (Dpb3-like subunit of ISW2/yCHRAC complex). To determine whether these polypeptides form a complex, we performed gel filtration column chromatography analysis of the immunoprecipitates. The Pol ɛ complex eluted in fractions 15 to 17 at a relative molecular mass of 670 kDa (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, Itc1, Isw2, Dpb4-5Flag, and Dls1 coeluted in fractions 11 to 13, encompassing the relative molecular masses of 1,000 to 670 kDa, suggesting that these four proteins form a complex distinct from Pol ɛ. These complexes were also isolated separately when we employed Dpb3-5Flag or Dls1-5Flag instead of Dpb4-5Flag (Fig. 4B, lanes 6 and 8). Similar results were obtained by the immunoprecipitation of Dpb4-5Flag from DPB3- or DLS1-deleted cell extracts (Fig. 4D, lanes 3 and 4). These results thus suggest that Dpb4 binds to either Pol2/Dpb2 or Isw2/Itc1 through its partnered histone motif protein, Dpb3 or Dls1. Since the composition of this novel complex (ISWI homolog, a WAC motif protein, and two histone fold motif proteins) is similar to that of chromatin accessibility complex (CHRAC) (60), a conserved chromatin-remodeling complex in higher eukaryotes, we named this complex yeast CHRAC-like complex (yCHRAC). Meanwhile, recent characterization of the ISW2 complex revealed that ISW2 exists mainly as a four-subunit complex (A. D. McConnel and T. Tsukiyama, personal communication). Thus, we designate this complex ISW2/yCHRAC. Interestingly, human Pol ɛ and CHRAC also share a common subunit, p17 (38, 46), suggesting that the relationship between Pol ɛ and the CHRAC-like complex (four-subunit ISW2 complex) is evolutionarily conserved.

FIG. 4.

Dpb4 is involved in two distinct complexes. (A) Anti-Flag immunoprecipitations were performed on protein extracts prepared from cells of YTI189 (wild-type allele, −) and YTI367 (5Flag-tagged allele, +). The immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (4 to 20% acrylamide) and visualized with silver stain (left panel). The immunoprecipitates were probed with anti-Pol ɛ (α-Pol ɛ), anti-Dpb3 (α-Dpb3), or anti-Flag (α-Flag) antibodies (right panels). (B) Anti-Flag immunoprecipitates from the cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE (4 to 20% acrylamide) and visualized with silver stain. The extracts were prepared from the indicated cells. In the left panel, a plus indicates a 5Flag-tagged gene and a minus indicates a wild-type allele. Strains used were YTI189 (no tag), YTI367 (DPB4-5FLAG), YTI460 (DPB4-5FLAG ITC1-13MYC), YTI461 (DPB4-5FLAG ISW2-13MYC), YTI365 (DPB3-5FLAG), and YTI459 (DLS1-5FLAG). (C) Silver staining of Superose 6 fractions (30 μl) separated by SDS-PAGE (5 to 20% acrylamide). The arrows indicate the positions of molecular weight markers, thyroglobulin (670 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), albumin (67 kDa), and RNase A (13 kDa). (D) Anti-Flag immunoprecipitations were performed on extracts prepared from cells of the indicated genotypes. +, epitope-tagged allele; −, wild-type deletion allele; wt, wild-type allele. The strains used were YTI189 (no tag), YTI367 (DPB4-5FLAG), YTI369 (DPB4-5LAG dpb3Δ), and YTI458 (DPB4-5FLAG dls1Δ). The protein band corresponding to Itc1 often smeared, probably because of modifications, as mentioned previously (21).

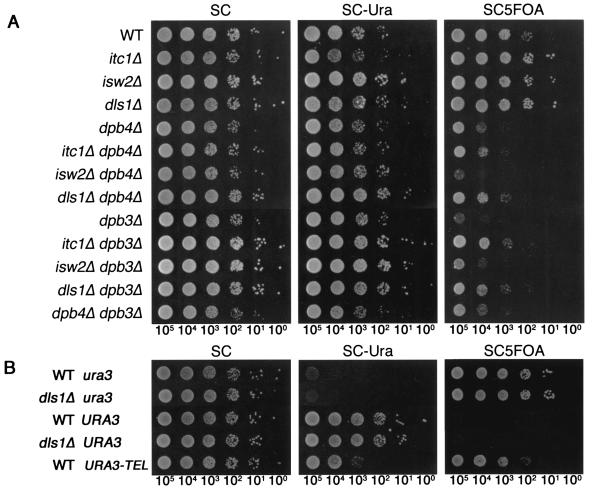

ISW2/yCHRAC counteracts Pol ɛ for TPE.

Since Dpb4 is shared by Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC, dpb4Δ cells lack both complexes, while dpb3Δ cells lack Pol ɛ but not ISW2/yCHRAC. We thus expected that ISW2/yCHRAC would counteract Pol ɛ for TPE by the reasons already described. As expected, the itc1Δ and dls1Δ mutations enhanced telomere silencing and restored it in dpb3Δ cells to the level in dpb4Δ cells, whereas they did not affect it in dpb4Δ cells (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, the isw2Δ mutation slightly enhanced the telomere-silencing defect in dpb4Δ mutant cells, suggesting that the Isw2 protein solely, not as a complex, or a putative complex of Isw2 with the other WAC domain protein (6), such as a product from YPL216w, plays a putative positive role in TPE. Moreover, in contrast to the dpb3Δ mutation, the dls1Δ mutation increased the switching rate from on to off but did not affect that from off to on (Table 3). As observed in the dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ mutations (Fig. 1B), the dls1Δ mutation did not affect the expression level of internal URA3 (Fig. 5B). Consistently, in the colony color assay, dls1Δ cells formed colonies with solid-red color while dpb3Δ dls1Δ formed colonies with solid-pink color, which suggests that dpb3Δ dls1Δ cells switch between alternative states at as a high frequency as dpb4Δ cells do (Fig. 2A). These results strongly suggest that Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC independently regulate epigenetic inheritance of silent and expressed states of TPE, respectively.

FIG. 5.

ISW2/yCHRAC counteracts Pol ɛ for TPE. The numbers under the photographs indicate the estimated number of cells placed on a spot. (A) Expression of the telomere-linked URA3 gene (VIIL::URA3-TEL) in the isogenic strains YTI249 (WT), YTI456 (itc1Δ), YTI452 (isw2Δ), YTI442 (dls1Δ), YTI266 (dpb4Δ), YTI458 (dpb4Δ itc1Δ), YTI454 (dpb4Δ isw2Δ), YTI444 (dpb4Δ dls1Δ), YTI250 (dpb3Δ), YTI457 (dpb3Δ itc1Δ), YTI453 (dpb3Δ isw2Δ), YTI443 (dpb3Δ dls1Δ), and YTI268 (dpb3Δ dpb4Δ) was assayed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. ITC1, ISW2, and DLS1 were deleted using TRP1, which makes cells grow slightly faster. Apparent weak suppression of dpb4Δ by itc1Δ and dls1Δ is caused by TRP1-marker effect. (B) Expression of URA3 at the internal chromosomal locus in dls1Δ mutant cells. The isogenic strains YTI279 (WT ura3), YTI473 (dls1Δ ura3), YTI297 (WT URA3), YTI470 (dls1Δ URA3), and YTI249 (WT URA3-TEL) were examined as described for panel A.

Chromatin structure in mutant cells.

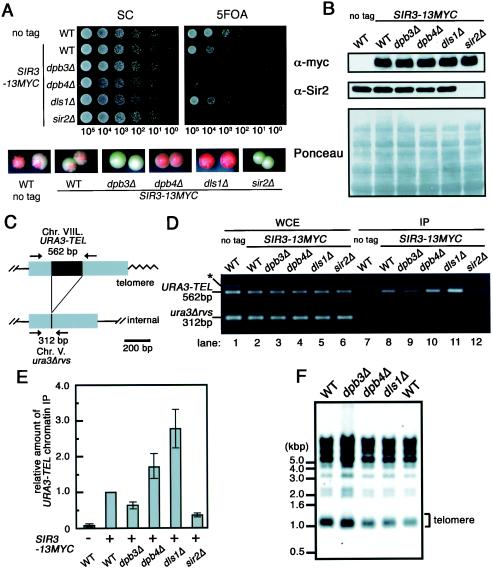

To form heterochromatin-like structure at telomeres, the Sir complex associates with telomeres (1). We therefore examined association of the Sir complex with the telomere in mutant cells using the ChIP assay. For this purpose, we replaced one of the genes encoding a subunit of the Sir complex, the SIR3 gene, by the SIR3-13MYC allele. Although the resultant cells bearing SIR3-13MYC showed slightly reduced telomere silencing, a similar effect of dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ, and dls1Δ on TPE was observed (Fig. 6A). We also observed similar levels of the Sir3-13myc protein in dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ, dls1Δ, and wild-type cells (Fig. 6B). Then, we performed the ChIP assay. As shown in Fig. 6D and E, the Sir3 protein associated with telomeric DNA, while its association is slightly reduced in dpb3Δ cells and is enhanced in dls1Δ cells. This is consistent with populations of on and off cells in these mutant-cell cultures (Table 3). Thus, this suggests that alteration of heterochromatin-like structure at the telomere in these mutant cells confers the defect of TPE. Moreover, the telomere length of dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ cells is almost the same as that of the wild-type cells (43), and we further found that wild-type, dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ, and dls1Δ cells have almost the same telomere length (Fig. 6F). Thus, these mutations reduce or enhance the telomere silencing, irrespective of the telomere length. Therefore, it is suggested that Pol ɛ functions for TPE through heterochromatin structure.

FIG. 6.

Association of Sir3 with telomeric URA3 in dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ, or dls1Δ mutant cells. (A) Silencing of the telomeric URA3 gene in strains with or without 13MYC epitope-tag allele of SIR3. The isogenic strains YTI312 (no tag, WT), YTI446 (SIR3-13MYC, WT), YTI464 (SIR3-13MYC, dpb3Δ), YTI465 (SIR3-13MYC, dpb4Δ), YTI466 (SIR3-13MYC, dls1Δ), and YTI467 (SIR3-13MYC, sir2Δ) were examined as described for Fig. 1 and 2. The numbers under the photographs indicate the estimated number of cells placed on a spot. (B) Steady-state protein levels of Sir3-13myc and Sir2 in the strains were determined by Western blot analysis using anti-myc antibodies (MBL) and anti-Sir2 antibodies (Santa Cruz). (C) The PCR primer set to amplify either telomeric URA3 or endogenous ura3 (ura3Δrvs) loci is shown. (D) Sir3 associations with the telomeric URA3 and endogenous ura3Δrvs loci (IP, lanes 7 to 12) were examined by ChIP assay using anti-c-myc antibodies. DNA from whole-cell extract was amplified as a control (WCE, lanes 1 to 6). The ChIP assay was performed on WT, dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ, dls1Δ, and sir2Δ cells (see panel C). (E) Relative amounts of URA3-TEL DNA in IP samples were quantified and normalized to input DNA, which were amplified from the same ChIPs in each strain (see panel D). (F) Telomere length in the isogenic strains YTI249 (WT), YTI250 (dpb3Δ), YTI266 (dpb4Δ), and YTI442 (dls1Δ). Yeast genomic DNA from each of the strains was digested with XhoI, separated on a 1.0% agarose gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and hybridized with poly-TG and poly-CA probes that hybridize to telomere repeat sequences.

DISCUSSION

We suggest in this paper that Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC are involved in TPE because mutants defective in subunits of Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC showed defect of TPE. Using the single-cell assay, we further found that Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC counteract for TPE noncompetitively. This finding gives us a novel view of TPE as described below. To explain the stochastic nature of switching epigenetic states, competition of the assembly of a silent chromatin and the transactivator has been proposed (2). This proposal predicts that when the switching rate for one direction is increased by a mutation, the other decreases and vice versa. This is not the case for Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC, because Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC function independently: Pol ɛ operates for stable inheritance of a silent state, while ISW2/yCHRAC works for that of an expressed state (Table 3). We therefore propose that Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC do not regulate the assembly of a silent chromatin and the transactivator in a competitive way, as previously proposed (2), but rather maintain or inherit proper configuration of the chromatin during cell division, probably during DNA replication. Two lines of evidence further support this idea. First, one of the replication proteins, PCNA, is suggested to be involved in the assembly of a silent chromatin (establishment) through CAF-1 (63). However, the roles of Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC seem to be distinct from that of CAF-I-PCNA (Table 2). Second, the dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ, and dls1Δ cells retain their silencing ability because mutations of Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC do not decrease but increase the switching rates (Table 3) and Sir3 is associated near the telomere in the ChIP assay in these mutants (Fig. 6). Thus, Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC seem not to affect the establishment of silencing. Note that the altered levels of association of Sir3 near telomere might reflect the maintenance or inheritance but not the establishment (assembly) of a silent chromatin in these mutant cells (Fig. 6D and E). This is further supported by the fact that high-copy-number SIR3 did not enhance the telomere silencing in dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ cells (Fig. 2B), because the increased dosage of Sir3 enhances the telomere silencing if the assembly of a silent chromatin is defective (48).

So far, we do not know whether Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC function for TPE directly or indirectly. However, we prefer the model of their direct involvement in maintenance or inheritance of chromatin structures because they do not influence the events that have been thought to affect TPE so far, telomere length and expression of Sir proteins (Fig. 6B and F). This is further strengthened by the recent observation that Dls1 as well as Dpb3 associates with the telomeric region in a chromosome-wide ChIP assay of yeast chromosome VI (K. Shirahige, personal communication). In recent studies, both human Pol ɛ (18) and ACF1-SNF2H (11), a human counterpart of Itc1-Isw2, were shown to be localized to late-replicating chromatin such as heterochromatin, and ACF1-SNF2H is required for efficient DNA replication in the heterochromatin region. We therefore suggest that Pol ɛ and the CHRAC-like complex (four-subunit ISW2 complex) in eukaryotic cells regulate duplication of the heterochromatin configuration that includes epigenetic information during or after DNA replication by their counteractions.

Since the small subunits of Pol ɛ are dispensable for the cell growth, their functions had not been well elucidated. The finding of their involvement in TPE suggests that Pol ɛ participates in not only chromosomal DNA replication but also duplication of chromatin structure. PCNA is also known to be involved in the maintenance of silencing as well as DNA replication, in cooperation with CAF-1 (63). Therefore, several replication proteins at replication forks seem to be involved in duplication of chromatin structure. Interestingly, Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC share a subunit, Dpb4. Since Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC are counteracting for TPE, it is likely that the ratio between Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC is kept constant, and consequently the silencing level of telomere is maintained constant.

Isw2 and Itc1 were shown to participate in repression of early meiotic genes and INO1 in mitotic cell cycle, which is mediated by the interaction with Ume6 (19, 21, 57) and PHO3, probably mediated by the interaction with a transcriptional regulator(s) other than Ume6 (31). Recently, it was also reported that Isw2 and Itc1 are required for full repression of a-type specific genes in α haploid and a/α diploid cells and this repression may be mediated by an a-type specific transcriptional regulator(s) (49) (it does not affect the single-cell telomere silencing assay). In the case of TPE, ISW2/yCHRAC works for derepression of URA3, ADE2, and α2, suggesting that it works irrespective of transcription regulators. Thus, it is likely that in TPE, ISW2/yCHRAC is directly involved in remodeling the chromatin structure, as shown in the association of Sir3 (Fig. 6D and E).

dpb3Δ cells displayed a partial defect in HMR silencing (our unpublished result, which does not affect the single-cell telomere assay [Table 3]) that also requires the Sir complex, and a previous study (53) reported that the mutation in DPB3 also caused a defect in rDNA silencing, which requires a distinct silencing complex, the RENT complex (55). Thus, Pol ɛ seems to maintain the configuration of common components of the heterochromatin-like structure, such as histones. Actually, YBL1 and YBL1-YCL1 (7), which are mouse counterparts of Dpb4 and Dpb4-Dls1, directly interact with histones in vitro. Therefore, it is conceivable that Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC directly regulate chromatin configuration through the interaction between histones and their histone fold subunits, Dpb4, Dpb3, and Dls1. From this viewpoint, although we could not coimmunoprecipitate them (our unpublished results), Pol ɛ and ISW2/yCHRAC may interact and respectively maintain hypoacetylated and hyperacetylated histones on chromatin and consequently counteract for the TPE.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Berman, S. Enomoto, D. E. Gottschling, D. Moazed, B. Stillman, and A. Sugino for providing various strains, plasmids, and antibodies; K. Shirahige and T. Tsukiyama for providing information before publication; and Y. Kamimura, S. Tanaka, and T. Tsukiyama for critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was partially supported by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aparicio, O. M., B. L. Billington, and D. E. Gottschling. 1991. Modifiers of position effect are shared between telomeric and silent mating-type loci in S. cerevisiae. Cell 66:1279-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aparicio, O. M., and D. E. Gottschling. 1994. Overcoming telomeric silencing: a trans-activator competes to establish gene expression in a cell cycle-dependent way. Genes Dev. 8:1133-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araki, H., R. K. Hamatake, A. Morrison, A. L. Johnson, L. H. Johnston, and A. Sugino. 1991. Cloning DPB3, the gene encoding the third subunit of DNA polymerase II of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:4867-4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araki, H., P. A. Ropp, A. L. Johnson, L. H. Johnston, A. Morrison, and A. Sugino. 1992. DNA polymerase II, the probable homolog of mammalian DNA polymerase ɛ, replicates chromosomal DNA in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 11:733-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bi, X., and J. R. Broach. 1997. DNA in transcriptionally silent chromatin assumes a distinct topology that is sensitive to cell cycle progression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:7077-7087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bochar, D. A., J. Savard, W. Wang, D. W. Lafleur, P. Moore, J. Côté, and R. Shiekhattar. 2000. A family of chromatin remodeling factors related to Williams syndrome transcription factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1038-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolognese, F., C. Imbriano, G. Caretti, and R. Mantovani. 2000. Cloning and characterization of the histone-fold proteins YBL1 and YCL1. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:3830-3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braunstein, M., A. B. Rose, S. G. Holmes, C. D. Allis, and J. R. Broach. 1993. Transcriptional silencing in yeast is associated with reduced nucleosome acetylation. Genes Dev. 7:592-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Budd, M., and J. L. Campbell. 1993. DNA polymerase δ and ɛ are required for chromosomal replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:496-505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caretti, G., M. C. Motta, and R. Mantovani. 1999. NF-Y associates with H3-H4 tetramers and octamers by multiple mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8591-8603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins, N., R. A. Poot, I. Kukimoto, C. Garcia-Jimenez, G. Dellaire, and P. D. Varga-Weisz. 2002. An ACF1-ISWI chromatin-remodeling complex is required for DNA replication through heterochromatin. Nat. Genet. 32:627-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corona, D. F., A. Eberharter, A. Budde, R. Deuring, S. Ferrari, P. Varga-Weisz, M. Wilm, J. Tamkun, and P. B. Becker. 2000. Two histone fold proteins, CHRAC-14 and CHRAC-16, are developmentally regulated subunits of chromatin accessibility complex (CHRAC). EMBO J. 19:3049-3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craig, I. W. 1994. Organization of the human genome. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 17:391-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Critchlow, S. E., and S. P. Jackson. 1998. DNA end-joining: from yeast to man. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:394-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dua, R., S. Edwards, D. L. Levy, and J. L. Campbell. 2000. Subunit interactions within the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase ɛ (Pol ɛ) complex. J. Biol. Chem. 275:28816-28825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duntze, W., V. MacKay, and T. R. Manney. 1970. Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a diffusible sex factor. Science 168:1472-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehrenhofer-Murray, A. E., R. T. Kamakaka, and J. Rine. 1999. A role for the replication proteins PCNA, RF-C, polymerase ɛ and Cdc45 in transcriptional silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 153:1171-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuss, J., and S. Linn. 2002. Human DNA polymerase ɛ colocalizes with proliferating cell nuclear antigen and DNA replication late, but not early, in S phase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8658-8666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelbart, M. E., T. Rechsteiner, T. J. Richmond, and T. Tsukiyama. 2001. Interactions of Isw2 chromatin remodeling complex with nucleosomal arrays: analyses using recombinant yeast histones and immobilized templates. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2098-2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gietz, R. D., and A. Sugino. 1988. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene 74:527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldmark, J. P., T. G. Fazzio, P. W. Estep, G. M. Church, and T. Tsukiyama. 2000. The Isw2 chromatin remodeling complex represses early meiotic gene upon recruitment by Ume6p. Cell 103:423-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottschling, D. E., O. M. Aparicio, B. L. Billington, and V. A. Zakian. 1990. Position effect at S. cerevisiae telomeres: reversible repression of Pol II transcription. Cell 63:751-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hecht, A., S. Strahl-Bolsinger, and M. Grunstein. 1996. Spreading of transcriptional repressor SIR3 from telomeric heterochromatin. Nature 383:92-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hecht, A., T. Laroche, S. Strahl-Bolsinger, S. M. Gasser, and M. Grunstein. 1995. Histone H3 and H4 N-termini interact with SIR3 and SIR4 proteins: a molecular model for the formation of heterochromatin in yeast. Cell 80:583-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heitz, E. 1928. Das Heterochromatin der Moose. Jahrb. Wiss. Bot. 69:762-818. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herskowitz, I., and Y. Oshima. 1981. Control of cell type in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: mating type and mating type interconversion, p. 181-209. In J. N. Strathern, E. W. Jones, and J. R. Broach (ed.), The molecular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces: life cycle and inheritance. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Holmquist, G. P. 1987. Role of replication time in the control of tissue-specific gene expression. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 40:151-173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holms, S. G., M. Braunstein, and J. R. Broach. 1996. Transcriptional silencing of the yeast mating-type genes, p. 467-487. In V. E. A. Russo, R. A. Martienssen, and A. D. Riggs (ed.), Epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 29.Kamimura, Y., Y. Tak, A. Sugino, and H. Araki. 2001. Sld3, which interacts with Cdc45 (Sld4), functions for chromosomal DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 20:2097-2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kassabov, S. R., N. M. Henry, M. Zofall, T. Tsukiyama, and B. Bartholomew. 2002. High-resolution mapping of changes in histone-DNA contacts of nucleosomes remodeled by ISW2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7524-7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kent, N. A., N. Karabetsou, P. K. Politis, and J. Mellor. 2001. In vivo chromatin remodeling by yeast ISWI homologs Isw1p and Isw2p. Genes Dev. 15:619-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurjan, J. 1993. The pheromone response pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Genet. 27:147-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lacoste, N., R. T. Utley, J. M. Hunter, G. G. Poirier, and J. Côté. 2002. Disruptor of telomeric silencing 1 is a chromatin-specific histone H3 methyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:30421-30424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langst, G., and P. B. Becker. 2001. Nucleosome mobilization and positioning by ISWI-containing chromatin-remodeling factors. J. Cell Sci. 114:2561-2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lau, A., H. Blitzblau, and S. P. Bell. 2002. Cell-cycle control of the establishment of mating-type silencing in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 16:2935-2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leeuwen, F., P. R. Gafken, and D. E. Gottschling. 2002. Dot1p modulates silencing in yeast by methylation of the nucleosome core. Cell 109:745-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, Y., H. Asahara, V. S. Patel, S. Zhou, and S. Linn. 1997. Purification, cDNA cloning, and gene mapping of the small subunit of human DNA polymerase ɛ. J. Biol. Chem. 272:32337-32344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li, Y., Z. F. Pursell, and S. Linn. 2000. Identification and cloning of two histone fold motif-containing subunits of HeLa DNA polymerase ɛ. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23247-23252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loo, S., and J. Rine. 1994. Silencers and domains of generalized repression. Science 264:1768-1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moazed, D., A. Kistler, A. Axelrod, J. Rine, and A. D. Johnson. 1997. Silent information regulator protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a SIR2/SIR4 complex and evidence for a regulatory domain in SIR4 that inhibits its interaction with SIR3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:2186-2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Navas, T. A., Z. Zhou, and S. J. Elledge. 1995. DNA polymerase links the DNA replication machinery to the S phase checkpoint. Cell 80:29-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ng, H. H., Q. Feng, H. Wang, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, Y. Zhang, and K. Struhl. 2002. Lysine methylation within the globular domain of histone H3 by Dot1 is important for telomeric silencing and Sir protein association. Genes Dev. 16:1518-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohya, T., Y. Kawasaki, S.-I. Hiraga, S. Kanbara, K. Nakajo, N. Nakashima, A. Suzuki, and A. Sugino. 2002. The DNA polymerase domain of Pol ɛ is required for rapid, efficient, and highly accurate chromosomal DNA replication, telomere length maintenance, and normal cell senescence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 277:28099-28108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohya, T., S. Maki, Y. Kawasaki, and A. Sugino. 2000. Structure and function of the fourth subunit (Dpb4p) of DNA polymerase ɛ in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:3846-3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pillus, L., and J. Rine. 1989. Epigenetic inheritance of transcriptional states in S. cerevisiae. Cell 59:637-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poot, R. A., G. Dellaire, B. B. Hülsmann, M. A. Grimaldi, D. F. V. Corona, P. B. Becker, W. A. Bickmore, and P. D. Varga-Weisz. 2000. HuCHRAC, a human ISWI chromatin remodelling complex contains hACF1 and two novel histone-fold proteins. EMBO J. 19:3377-3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raghuraman, M. K., E. A. Winzeler, D. Collingwood, S. Hunt, L. Wodicka, A. Conway, J. Lockhart, R. W. Davis, B. J. Brewer, and W. L. Fangman. 2001. Replication dynamics of the yeast genome. Science 294:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Renauld, H., O. M. Aparicio, P. D. Zierath, B. L. Billington, S. K. Chhablani, and D. E. Gottschling. 1993. Silent domains are assembled continuously from the telomere and are defined by promoter distance and strength, and by SIR3 dosage. Genes Dev. 7:1133-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruiz, C., V. Escribano, E. Morgado, M. Molina, and M. J. Mazón. 2003. Cell-type-dependent repression of yeast a-specific genes requires Itc1p, a subunit of the Isw2p-Itc1p chromatin remodeling complex. Microbiology 149:341-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shou, W., K. M. Sakamoto, J. Keener, K. W. Morimoto, E. E. Traverso, R. Azzam, G. J. Hoppe, R. M. Feldman, J. DeModena, D. Moazed, et al. 2001. Net1 stimulates RNA polymerase I transcription and regulates nucleolar structure independently of controlling mitotic exit. Mol. Cell 8:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singer, M. S., and D. E. Gottschling. 1994. TLC1: template RNA component of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase. Science 266:404-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith, J. S., and J. D. Boeke. 1997. An unusual form of transcriptional silencing in yeast ribosomal DNA. Genes Dev. 11:241-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith, J. S., E. Caputo, and J. D. Boeke. 1999. A genetic screen for ribosomal DNA silencing defects identifies multiple DNA replication and chromatin-modulating factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3184-3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strahl-Bolsinger, S., A. Hecht, K. Luo, and M. Grunstein. 1997. SIR2 and SIR4 interactions differ in core and extended telomeric heterochromatin in yeast. Genes Dev. 11:83-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Straight, A. F., W. Shou, G. J. Dowd, C. W. Turck, R. J. Deshaies, A. D. Johnson, and D. Moazed. 1999. Net1, a Sir2-associated nucleolar protein required for rDNA silencing and nucleolar integrity. Cell 97:245-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sugino, A. 1995. Yeast DNA polymerases and their role at the replication fork. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20:319-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sugiyama, M., and J. I. Nikawa. 2001. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Isw2p-Itc1p complex represses INO1 expression and maintains cell morphology. J. Bacteriol. 183:4985-4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takayama, Y., Y. Kamimura, M. Okawa, S. Muramatsu, A. Sugino, and H. Araki. 2003. GINS, a novel multi-protein complex required for chromosomal DNA replication in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 17:1153-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsukiyama, T., J. Palmer, C. C. Landel, J. Shiloach, and C. Wu. 1999. Characterization of the imitation switch subfamily of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 13:686-697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Varga-Weisz, P. D., M. Wilm, E. Bonte, K. Dumas, M. Mann, and P. B. Becker. 1997. Chromatin-remodelling factor CHRAC contains the ATPases ISWI and topoisomerase II. Nature 388:598-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woontner, M., P. A. Wade, J. Bonner, and J. A. Jaehning. 1991. Transcriptional activation in an improved whole-cell extract from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:4555-4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zachariae, W., T. H. Shin, M. Galova, B. Obermaier, and K. Nasmyth. 1996. Identification of subunits of the anaphase-promoting complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 274:1201-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang, Z., K. Shibahara, and B. Stillman. 2000. PCNA connects DNA replication to epigenetic inheritance in yeast. Nature 408:221-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]