Abstract

Docetaxel is currently the most effective drug for the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), but it only extends life by an average of 2 months. Lycopene, an antioxidant phytochemical, has antitumor activity against prostate cancer (PCa) in several models and is generally safe. We present data on the interaction between docetaxel and lycopene in CRPC models. The growth-inhibitory effect of lycopene on PCa cell lines was positively associated with insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) levels. In addition, lycopene treatment enhanced the growth-inhibitory effect of docetaxel more effectively on DU145 cells with IGF-IR high expression than on those PCa cell lines with IGF-IR low expression. In a DU145 xenograft tumor model, docetaxel plus lycopene caused tumor regression, with a 38% increase in antitumor efficacy (P = .047) when compared with docetaxel alone. Lycopene inhibited IGF-IR activation through inhibiting IGF-I stimulation and by increasing the expression and secretion of IGF-BP3. Downstream effects include inhibition of AKT kinase activity and survivin expression, followed by apoptosis. Together, the enhancement of docetaxel's antitumor efficacy by lycopene supplementation justifies further clinical investigation of lycopene and docetaxel combination for CRPC patients. CRPC patients with IGF-IR-overexpressing tumors may be most likely to benefit from this combination.

Introduction

Most advanced prostate cancer (PCa) patients respond well to initial treatment with androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) [1,2]. However, nearly all patients eventually develop resistance to ADT and disease progression [1,2]. Docetaxel-based chemotherapy has recently shown significant but short-lived survival benefit and has become the major remaining treatment option for castration-resistant PCa (CRPC) [3]. However, with the demonstrated survival benefit of approximately 2 months, median survival of 18 to 20 months and a response rate of only approximately 50%, the docetaxel-based chemotherapy remains palliative for men with CRPC. Therefore, there is a need for investigation and development of novel agents that can add to and improve the docetaxel-based therapy.

PCa is a biologically complex and highly heterogeneous disease [4–6]. The complex interactions of nutrients with genetic and hormonal effectors not only contribute to the development of distinct clinical pictures of PCa among different geographical regions [4–6] but also make PCa an especially amenable target for preventive and therapeutic intervention through nutritional combinations. Lycopene is a plant carotenoid naturally present in tomatoes and tomato products [7]. Lycopene accumulates in prostate tissue and functions as a potent antioxidant in in vitro systems [7–10]. In a large prospective cohort study, Giovannucci et al. [11] reported that consumption of lycopene-rich foods was associated with a 30% to 40% reduction in the PCa risk and that the preventive effects of lycopene-rich foods are more pronounced in subgroups with aggressive disease, older men, or men without a family history of PCa. Moreover, lycopene was shown to inhibit both IL-6 signaling and the IGF-I pathways that participate in resistance to ADT and chemotherapy (e.g., docetaxel) [12–20]. Therefore, lycopene could be an attractive agent in augmenting docetaxel-based chemotherapy for treatment of men with CRPC.

Alternatively, lycopene could potentially function as a potent antioxidant in PCa per se to inhibit oxidative stresses and DNA damage [21–24], antagonizing the therapeutic effects of docetaxel [21]. Despite the recommendations from oncology societies not to take supplements during chemotherapy [21], many patients do mix conventional and alternative treatments. Therefore, there is an urgent clinical need to address whether the concurrent use of lycopene supplements with docetaxel-based chemotherapy would antagonize or enhance antitumor efficacy.

In this study, we demonstrate that lycopene enhances the effect of docetaxel on the growth of CRPC cell lines both in vitro and in vivo. PCa cell lines expressing high insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) levels are more sensitive to the growth-inhibitory effect of lycopene compared with those cell lines with low IGF-IR. Our data suggest that one potential mechanism of lycopene's action is inactivation of IGF-IR by inhibiting IGF-I stimulation and by increasing the expression and secretion of IGF-BP3. Downstream effects include inhibition of AKT kinase activity and survivin expression, followed by apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines, Plasmid, Stable Transfection, Compounds, and Reagents

The LNCaP, LAPC-4, DU145, 22Rv1, and PC-3 cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS.

The PCDNA3.1, containing a full-length 4.7-kb fragment of IGF-IR, was described previously in detail [25]. LNCaP cells were stably transfected with pcDNA3.1(+)/IGF-IR using FuGENE 6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Transfected cells were selected with G418 (800 µg/ml) starting at 48 hours after transfection, and all of the stable transfectants were pooled to avoid cloning artifacts. Pooled stable clones of LNCaP cells expressing IGF-IR weremaintained in RPMI containing 10%FBS and 500 µg/ml G418.

Tetrahydrofuran (THF) containing 0.025% butylated hydroxytoluene was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Pure all-trans lycopene was purchased from Wako Chemicals, Inc (Irvine, CA) and dissolved in THF to a concentration of 15 mM. This stock solution was prepared with minimal exposure to air and light and stored at -80°C. LycoVit 10% cold water dispersible (CWD) was from BASF Corporation (Shreveport, LA), which contains microencapsulated synthetic lycopene. There is 11.45% total lycopene with 77% all-trans and 23% total cis-lycopene, and less than 2% vitamin E in this product. Docetaxel injection solution was obtained from the UCI Medical Center Pharmacy. Picropodophyllin (PPP), a potent and selective IGF-IR kinase inhibitor, was purchased from Biaffin GmbH & CoKG (Kassel, Germany). Thymidine, 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), propidium iodide (PI), and other chemicals were from Sigma.

Antibodies for AKT, phospho-AKT, and survivin were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc (Beverly, MA). Antibodies against IGF-IRβ and β-actin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). IGF-BP3 antibody was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Ki67 antibody was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Dead End Colorimetric Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) System was from Promega (Madison, WI).

MTT Assay

The MTT assay was performed as previously described [26]. Dose response curves for growth inhibition were generated as a percentage of vehicle-treated control. Immediately before the experiment, THF lycopene aliquots from the stock solution were added to culture medium to achieve a final concentration of 0.05, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 50, and 100 µM. The final maximum concentration of THF in the culture medium was 0.1%, which did not affect cell viability as indicated by comparison with control medium. PPP was dissolved in ethanol and added to the culture medium to achieve a final concentration of 7.8, 15.6, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 nM. Cells were treated for 3 days. MTT was added to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. The reaction mixture was incubated for 3 hours at 37°C, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm.

DNA Histogram Analysis

Cells were treated with vehicle controls (0.1% DMSO, 0.1% THF, or 0.1% DMSO + 0.1% THF), 1 µM lycopene, 10 µM lycopene, 1 nM docetaxel, 31.25 nM PPP, 1 or 10 µM lycopene plus 1 nM docetaxel, or 31.25 nM PPP plus 1 nM docetaxel for 24 hours. After the stated treatments, cells were stained with PI in PBS. All analyses of cells were done using appropriate scatter gates to exclude cellular debris and aggregated cells. Ten thousand events were collected for each sample stained PI.

Western Blot Analysis and Immunoprecipitation

Clarified protein lysates (20–80 µg) were denatured and resolved by 8% to 16% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, probed with antibodies, and visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system.

Total protein (500 µg) was precleared with protein A-agarose and then precipitated with 2 µg of anti-IGF-IRβ or IgG antibody overnight at 4°C. Agarose beads were washed four times with lysis buffer and resuspended in SDS-PAGE 2x sample buffer. Proteins were eluted by boiling the beads and subjected to immunoblot analysis of antiphosphotyrosine or anti-IGF-IRβ.

In Vivo Tumor Model

NCR-nu/nu (nude) mice were obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). DU145 cells were concentrated to 1 x 106 per 100 µl of PBS and injected subcutaneously into the right flank of each mouse. Once xenografts started growing, their sizes were measured twice a week. The tumor volume was calculated by the formula: 0.5236L1(L2)2, where L1 is the long axis and L2 is the short axis of the tumor. Once mice bearing the DU145 tumors (eight per group) developed a tumor size of approximately 200 mm3, they were randomly assigned to four different treatment groups including vehicle control (water), 15 mg/kg LycoVit 10% CWD daily, 10 mg/kg docetaxel weekly for three doses, and 15 mg/kg lycopene daily plus three weekly doses of docetaxel. Lycopene was given as LycoVit 10% CWD suspended in cold water by gavage. Docetaxel was given by intraperitoneal injection. At the end of the experiment, tumors were excised and weighed, blood was collected, and all were stored at -80°C until additional analysis.

To assess if these treatments affected survival or tumor growth delay of mice bearing DU145 tumors, these mice were administered vehicle control (water), lycopene (15 mg/kg per day) alone, docetaxel (5 or 10 mg/kg per week for three doses) alone or combination of both and followed up until the tumor volume reached 1500 mm3. All mice that died prematurely or were killed had necropsy done on them to ensure that there were no pathologic disease other than tumor-related disease.

Immunohistochemical Staining for Ki67 and Survivin

Tumor tissues were harvested and fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned. Antigen retrieval was done using 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 15 minutes. Sections were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-Ki67 antibody (1:500 dilution) or antisurvivin (1:50) in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature in a humidity chamber followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. Slides were then incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody. Slides were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin and photographed using a light microscope. Negative control samples were exposed to a secondary antibody with a similar IgG isotype to the primary antibody. Proliferating cells were quantified by counting Ki67-positive cells (brown stained) and total number of cells at five arbitrarily selected fields at x400 magnification.

TUNEL Staining for Apoptotic Cells

Apoptotic cells were detected using the DeadEnd Colorimetric TUNEL system following the manufacturer's protocol. The extent of apoptosis was evaluated by counting the TUNEL-positive cells (brown-stained) as well as the total number of cells in five randomly selected fields at x400 magnification.

Statistics

Comparisons of cell cycle population, proliferation and apoptosis indices, cell viability between treatment and control were conducted using Student t test or one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni t test. For tumor growth experiments, repeated-measures ANOVA was used to examine the differences in tumor sizes among treatments, time points, and treatment-time interactions. Additional posttests were done to examine the differences in tumor sizes between control and treatments at each time point by using conservative Bonferroni method. To correlate cell growth-inhibitory effect of levels and IGF-IR protein expression on Western blots, Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated from their IC50 values and from densitometry measurements of protein bands. Log-rank test was used to analyze the survival of tumor-bearing mice between control and treatment groups. All statistical tests were two-sided. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Lycopene Enhances the Growth-Inhibitory Effect of Docetaxel on PCa Cell Lines

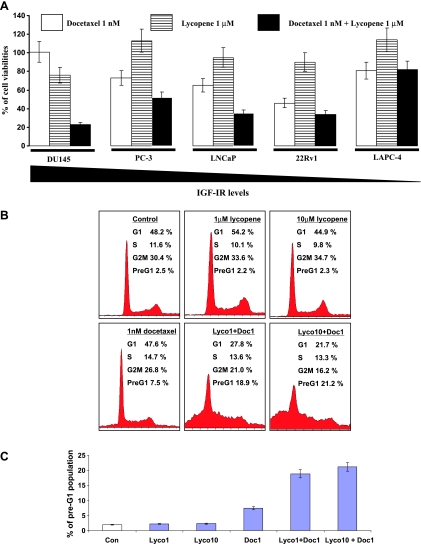

To examine whether lycopene can interfere with or enhance the anti-PCa activity of docetaxel, we have treated 22Rv1, LNCaP, LAPC-4, DU145, and PC-3 cells with 1 nM docetaxel, 1 µM lycopene (a pharmacologically achievable concentration) [7], or combination of both for 3 days. One nanomolar of docetaxel inhibited the cell growth of 22Rv1, LNCaP, LAPC-4, PC-3, and DU145 by approximately 54%, 35%, 19%, 27%, and 0%, respectively, whereas 1 µMlycopene reduced their growth by 10% (22Rv1), 5% (LNCaP), 19% (LAPC-4), 0% (PC-3), and 24% (DU145) (Figure 1A). When these cells were treated with the combination of docetaxel and lycopene, the cell densities of DU145, PC-3, 22Rv1, LNCaP, and LAPC-4 were further reduced by 78%, 21%, 20%, 21%, and 0%, respectively, compared with docetaxel alone (Figure 1A). The growth-inhibitory effect of the combination on DU145, PC-3, 22Rv1, and LNCaP cells was greater than the effects of docetaxel treatment alone (ANOVA test, P values < .05; Figure 1A). Notably, the growth-inhibitory effect of the combination on DU145 cells with higher IGF-IR expression is the most pronounced among the tested cell lines. These results suggest a synergistic and/or additive effect of docetaxel and lycopene on cell growth depending on cell types.

Figure 1.

Lycopene enhances the effect of docetaxel on reduction of cell viabilities and induction of apoptosis. (A) A total of 5 x 104 22Rv1, LNCaP, LAPC-4, DU145, and PC-3 cells were plated in 24-well culture plates. After 24 hours, the medium was changed to fresh medium and treated with vehicle controls (0.1% DMSO alone, 0.1% THF alone, or 0.1% DMSO plus 0.1% THF), 1 nM docetaxel (blank bars), 1 µM lycopene (strip bars), and 1 nM docetaxel plus 1 µM lycopene (solid bars). The medium was changed daily, after 72 hours of treatments; the number of viable cells was measured by the MTT assay and expressed relative to their vehicle controls. Each point is the mean of four independent plates. Bars, ±SE. (B and C) DU145 cells were stained by PI and pre-G1, and the cell cycle populations were analyzed by flow cytometry. Con, Lyco1, Lyco10, and Doc1 denote vehicle control, 1 µM lycopene, 10 µM lycopene, and 1 nM docetaxel, respectively. A representative photograph of cell cycle population distribution for each treatment is presented. Each bar represents the mean ± SE from three independent experiments.

Cell cycle analysis further revealed that lycopene and docetaxel combination resulted in a significant increase in the pre-G1 population of DU145 cells compared with either lycopene or docetaxel treatment alone (Figure 1, B and C; P values < .05, ANOVA test). This result suggests that lycopene may increase DU145 cell sensitivity to docetaxel-mediated apoptosis. Its effects in other cell lines were less marked (data not shown).

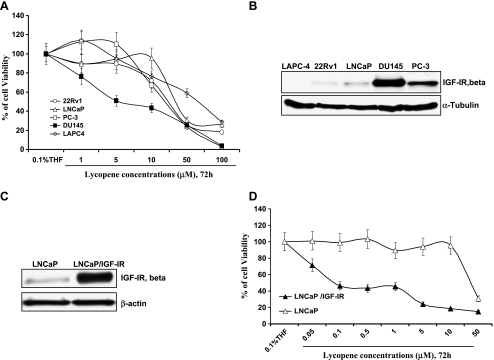

The Inhibitory Effect of Lycopene on the Growth of PCa Cell Lines Is Associated with the Levels of IGF-IR

Figure 2A show that DU145 cells with higher levels of IGF-IR were approximately three- to seven-fold more sensitive to the inhibitory effect of lycopene on cell viability than other tested cell lines. Table 1 shows that the IC50 values of lycopene for DU145, PC-3, LNCaP, 22Rv1, and LAPC-4 cells were estimated to be 5.1, 15, 36 16, and 50 µM, respectively, and their levels of IGF-IR (Figure 2B) were estimated by densitometry to be 9.3 (DU145), 4.1 (PC-3), 2.0 (LNCaP), 1.0 (22Rv1), and 0.8 (LAPC-4), respectively. There was a trend that cell lines with more IGF-IR expression are more sensitive to lycopene treatment (Pearson correlation coefficient, -0.58; Student t test, P values < .05). However, in addition to difference in IGF-IR levels, these cell lines have other distinct characteristics (e.g., androgen receptor, p53, and PTEN status) that may influence their response to lycopene or docetaxel [27]. To avoid these confounding factors, we established a pair of isogenic cell lines: parental LNCaP and LNCaP stably expressing high levels of IGF-IR (LNCaP/IGF-IR) (Figure 2C). Figure 2D shows that LNCaP/IGF-IR cells were approximately 400-fold more sensitive to the effect of lycopene on reduction of cell viability than parental LNCaP cells (IC50 values for LNCaP and LNCaP/IGF-IR were 36 and 0.08 µM, respectively). This result suggests that IGF-IR may be a critical factor for the growth-inhibitory effect of lycopene.

Figure 2.

The inhibitory effect of lycopene on the viability of PCa cell lines is dependent on their IGF-IR levels. (A) A total of 5 x 104 22Rv1, LNCaP, LAPC-4, DU145, and PC-3 cells were plated in 24-well plates. After 24 hours, the medium was changed to fresh medium and treated with vehicle control (0.1% THF) and different concentrations of lycopene (1–100 µM). The medium was changed daily. After 72 hours of treatments, cell viability was measured by MTT assay. Viable cell number relative to their vehicle controls for different treatments is calculated. Each point is the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. Each sample was counted in duplicate. (B and C) IGF-IR expression was analyzed by immunoblot analysis followed by densitometry. (D) LNCaP and LNCaP/IGF-R cells were treated similarly as described in A with 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, and 50 µM lycopene for 72 hours. Cell viability is determined by MTT assays. The percentage of cell viabilities relative to their vehicle controls for different treatments is calculated. Each point is the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. Each sample was counted in duplicate.

Table 1.

The Relationship between IGF-IR Levels and the IC50 Values of Lycopene in PCa Cell Lines.

| LNCaP/IGF-IR | DU145 | PC-3 | LNCaP | 22RV1 | LAPC-4 | |

| IC50 values of lycopene | 0.08 | 5.1 | 15 | 36 | 16 | 50 |

| IGF-IR levels estimated | 77.19 | 9.3 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

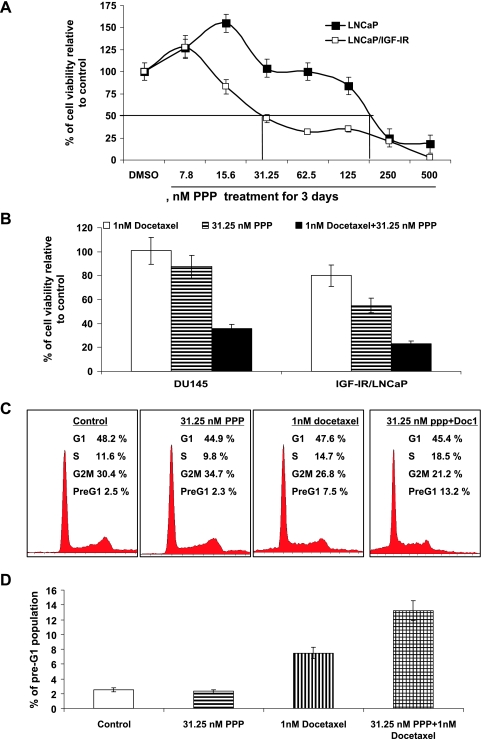

PPP, a Selective IGF-IR Kinase Inhibitor, Also Potentiates the Growth-Inhibitory Effect of Docetaxel on DU145 and LNCaP Overexpressing IGF-IR Cell Lines

We next examine whether IGF-IR expression was related to the effectiveness of PPP, a selective IGF-IR kinase inhibitor, on PCa cell growth, and whether PPP could enhance the efficacy of docetaxel on PCa cell growth. Figure 3A shows that LNCaP overexpressing IGF-IR were approximately seven-fold times more sensitive to PPP treatment for its growth-inhibitory effect than the parental LNCaP cell line. This result suggested that inhibition of IGF-IR activation by an IGF-IR kinase inhibitor also, at least in part, required IGF-IR expression for its capacity to reduce PCa cell growth.

Figure 3.

PPP potentiates the growth-inhibitory effect of docetaxel on DU145 and LNCaP overexpressing IGF-IR cell lines. (A) LNCaP and LNCaP/IGF-R cells were treated similarly as described above with 0.1% DMSO or 7.8, 15.6, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250 or 500 nM PPP, a specific IGF-IR kinase inhibitor for 72 hours. Cell viabilities are determined by MTT assays. The percentage of cell viabilities relative to their vehicle controls for different treatments is calculated. Each point is the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. Each sample was counted in duplicate. (B) DU145 and LNCaP/IGF-R cells were treated similarly as described above with 0.1% DMSO, 31.25 nM PPP, 1 nM docetaxel, or 1 nM docetaxel plus 31.25 nM PPP for 72 hours. Cell viabilities are determined by MTT assays. The percentage of cell viabilities relative to their vehicle controls for different treatments is calculated. Each point is the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. Each sample was counted in duplicate. (C and D) DU145 Cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO, 31.25 nM PPP, 1 nM docetaxel, or 1 nM docetaxel (Doc1) plus 31.25 nM PPP for 24 hours. Cells were stained by PI and pre-G1, and cell cycle populations were analyzed by flow cytometry. A representative photograph of cell cycle population distribution for each treatment is presented. Bars represent the means from three independent experiments. Standard errors are less than 5%.

Figure 3B shows that 31.25 nM PPP in combination with 1 nM docetaxel for the treatment of DU145 and LNCaP/IGF-IR cell lines increased the absolute reduction of cell growth by approximately 65% to 58%, respectively, compared with docetaxel treatment alone (P values < .01, Student t test). Furthermore, cell cycle analysis of pre-G1 population showed that lycopene significantly potentiated the apoptotic effect of docetaxel in DU145 cells (Figure 3, C and D). These results confirm that inhibition of IGF-IR activity can enhance the anti-PCa activities of docetaxel.

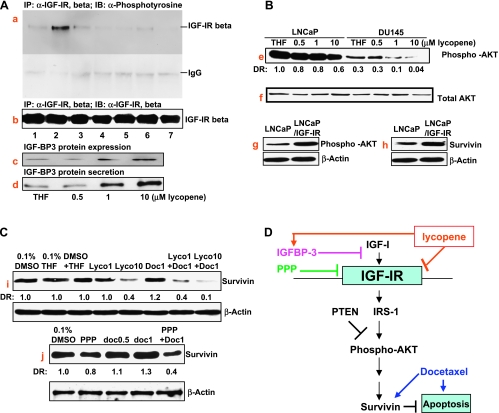

Lycopene Inhibits IGF-I-Induced IGF-IR Activation and Increases IGF-BP3 Expression and Secretion, Leading to Inhibition of Downstream Signaling Events

Because the inhibitory effect of lycopene on the growth of PCa cell lines is associated with cellular IGF-IR levels, we examined whether lycopene inhibited IGF-I-induced IGF-IR activation. Figure 4A (panels a and b) shows that pretreatment of serum-starved DU145 cells with lycopene or PPP for 2 hours attenuated IGF-I-induced IGF-IR phosphorylation without changing IGF-IR protein levels, suggesting that lycopene may directly interfere with IGF-I activation of IGF-IR or IGF-IR kinase activity. In addition, Figure 4A (panels c and d) shows that treatment of DU145 cells with lycopene for 24 hours resulted in a dose-dependent increase of IGF-BP3 protein expression and secretion. The increased IGF-BP3 levels seen after lycopene treatment are also expected to block IGF-I activation of IGF-IR through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms.

Figure 4.

The effect of lycopene on IGF-IR and its mediated AKT/survivin pathway in PCa cells. (A) DU145 cells at 70% confluency were serum-starved for 36 hours. During the last 2 hours of serum starvation, lycopene, PPP, and docetaxel at indicated concentrations were added into the medium. After these treatments, cells were incubated with PBS or 100 ng/ml IGF-I for 15 minutes at 37°C. Cell lysates were prepared, IGF-IR was immunoprecipitated using anti-IGF-IRβ antibody, and Western blot analyses were performed using anti-phosphotyrosine (panel a) or anti-IGF-IRβ (panel b). Lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 denote vehicle control, vehicle control + 100 ng/ml IGF-I, 1 µM lycopene, 1 µM lycopene + 100 ng/ml IGF-I, 10 µM lycopene + 100 ng/ml IGF-I, 50 nM PPP + 100 ng/ml IGF-I, and 1 µM lycopene + 1 nM docetaxel + 100 ng/ml IGF-I, respectively. Panel c: DU145 cells in the serum medium were treated by lycopene at indicated concentrations for 24 hours. IGF-BP3 expression in protein lysates was determined by Western blot analysis. Panel d: DU145 in serum-free medium were treated by lycopene at indicated concentrations for 48 hours. IGF-BP3 secretion was determined by Western blot analysis of concentrated conditioned medium. (B) LNCaP and DU145 cells were treated with 0.1% THF (vehicle control), 0.5, 1, or 10 µM lycopene for 24 hours. Phospho-AKT and total AKT in the treated DU145, LNCaP, and LNCaP/IGF-IR cells were determined by Western blot analysis. DR denotes densitometry measurement ratio relative to vehicle control. (C) DU 145 cells were treated with vehicle controls (0.1% DMSO, 0.1% THF, or 0.1% DMSO + 0.1% THF), 1 µM lycopene (lyco1), 10 µM lycopene (lyco10), 0.5 nM docetaxel (doc0.5), 1 nM docetaxel (doc1), 15.6 nM PPP, 1 or 10 µM lycopene plus 1 nM docetaxel, or 15.6 nM PPP plus 1 nM docetaxel. DRs are densitometry ratios relative to vehicle controls. (D) Graphical presentation of the proposed mechanisms of lycopene in inhibiting the IGF-IR-medicated survival pathway for the enhancement of resistance to docetaxel-induced apoptosis.

Figure 4A (panels e and f) shows that lycopene treatment caused a dose-dependent decrease of active AKT (as indicated by its phosphorylation) without affecting total AKT protein levels. The inhibitory effect of lycopene on AKT activation is more pronounced in DU145 than in LNCaP cells. Compared with DU145 cells, LNCaP cell line has a higher level of AKT phosporylation owing to its loss of PTEN [25], although it expresses less IGF-IR. It is possible that the downstream events of the IGF-IR signaling, AKT and survivin, will be more subjected to the IGF-IR regulation in DU145 cells than in LNCaP cells. Indeed, compared with their vehicle controls, 1 µM lycopene decreased the levels of phospho-AKT in LNCaP and DU145 cells by approximately 20% and 60%, respectively. In addition, Figure 4A (panels g and h) shows that LNCaP cells overexpressing IGF-IR have increased protein levels of active AKT and antiapoptotic protein survivin compared with the parental LNCaP cell line.

Figure 4C (panels i and j) shows that docetaxel alone slightly increases the protein expression of survivin, whereas docetaxel in combination with lycopene or the IGF-IR kinase inhibitor, PPP, seems to synergistically downregulate the protein expression of survivin in DU145 cells. Taken together, these results suggest that lycopene inhibits IGF-IR activation leading to inactivation of the AKT/survivin pathway.

Lycopene Supplement Enhances the Antitumor Efficacy of Docetaxel and Prolongs the Survival of Tumor-Bearing Mice in a Xenograft Model

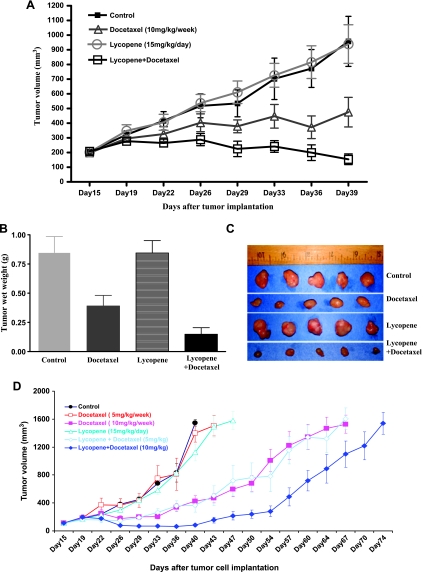

Figure 5A shows that docetaxel and docetaxel-plus-lycopene treatments result in a significant decrease in the growth rate of DU145 tumors compared with vehicle control or 15 mg/kg lycopene supplement alone (ANOVA, P values < .05). The inhibitory effect of lycopene supplement plus docetaxel on tumor growth is more pronounced than that of docetaxel alone treatment (ANOVA, P values < .05). The tumor weights of DU145 cells in control, docetaxel, lycopene, and docetaxel-plus-lycopene groups recorded at the end of the treatment were 0.85 ± 0.36, 0.39 ± 0.24, 0.84 ± 0.28, and 0.15 ± 0.15 g (mean tumor weight ± SD), respectively. Lycopene significantly enhanced the antitumor efficacy of docetaxel by approximately 38% (Student t test, P = .042; Figure 5, B and C).

Figure 5.

Lycopene supplementation improves the antitumor efficacy of docetaxel in the DU145 tumor xenograft model. DU145 cells (1 x 106) were injected into the right flank of NCR-nu/nu (nude) mice. Once tumors started growing, their sizes were measured twice weekly in two dimensions, throughout the study. The tumor volume was calculated by the formula: 0.5236L1(L2)2, where L1 is the long diameter and L2 is the short diameter. Tumor volume (mm3) is represented as the mean of eight mice in each group. When tumor volume reached 200 mm3 measured by caliper, mice bearing DU145 tumors were randomly divided into four or six different groups as indicated. Control group of mice received water by gavage. Lycopene was given daily via gavage for the whole period, and docetaxel was intraperitoneally injected into mice bearing DU145 tumors weekly for three doses. (A) Tumor growth curve, points, and mean tumor volumes. Bars, SE. (B) Mean wet weights of tumors from different groups of treatments. At the termination of the study, tumors were excised from each mouse in different groups and weighed. Bars, SE. (C) Photographs of tumors from different groups of treatments. (D) Tumor growth curve for tumor volumes to reach 1500 mm3, points, mean tumor volumes. Bars, SE.

The efficacy of lycopene supplement (15 mg/kg per day), docetaxel (5 or 10 mg/kg per week for three doses), or combination of each was further assessed using growth delay, measured as the time from the start of tumor cell implantation for either tumor in a mouse to reach a volume of approximately 1500 mm3 or when a mouse died spontaneously. Administration of a higher dose of docetaxel (10 mg/kg per week) or combination of lycopene supplement with a lower (5 mg/kg per week) or higher (10 mg/kg per week) dose of docetaxel prolonged the survival time of mice (Figure 5D), compared with control, lycopene alone, or low-dose docetaxel alone. The median times for tumors to reach 1500 mm3 in the control, lycopene supplement, and lower-dose docetaxel groups are 41.5 ± 6, 43 ± 7, and 45 ± 3 days, respectively. The median times for tumors to reach 1500 mm3 in the higher dose of docetaxel and combination of lycopene supplements with the high or low dose of docetaxel groups are 62 ± 8, 64 ± 8, and 70 ± 4 days, respectively, which demonstrated significantly delayed tumor growth by an average of 21 to 32 days relative to the controls (Figure 5D; log-rank tests, P values < .001). The efficacy of lycopene supplement in combination with the lower dose of docetaxel (5 mg/kg per week) to delay tumor growth and prolonging the survival of tumor-bearing mice was almost equal to that of the higher dose of docetaxel (10 mg/kg per week) alone. These results confirm that lycopene supplementation enhanced the antitumor efficacy of docetaxel even at its suboptimal dose.

Lycopene Supplement and Docetaxel Combined Treatment Induced a Significant Tumor Morphology Alternation Resembling of Mitotic Catastrophe with Apoptosis, as well as Decreased Cell Proliferation and Survivin Expression in Tumor Tissues

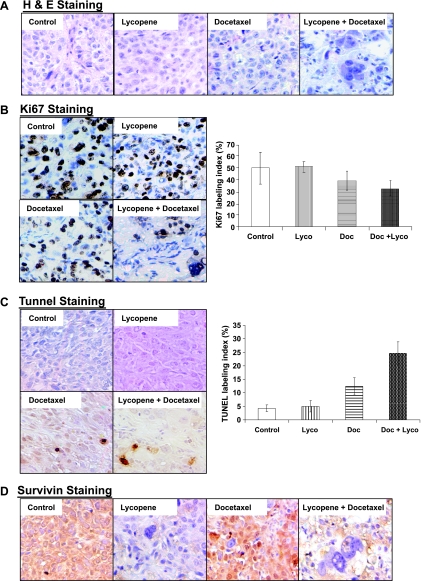

Histologic analysis of hematoxylin and eosin-stained tumor sections from DU145 xenograft-bearing mice treated with lycopene supplementation plus or minus docetaxel demonstrated a dramatic change in tissue and cell morphology when compared with vehicle control, lycopene supplement, or docetaxel alone (Figure 6A). These changes include low cell density and multinucleated cells with condensed chromatin staining and pyknosis, indicating mitotic catastrophe and apoptosis.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry of DU145 tumors from mice treated with lycopene, docetaxel, or their combination. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tumor sections from different treatment groups including vehicle control, lycopene (15 mg/kg per day), docetaxel (10 mg/kg per week), and lycopene (15 mg/kg per day) plus docetaxel (10 mg/kg per week). Original magnification, x200. (B) At the end of the experiment, mice were killed, tumor tissues were analyzed for immunohistochemical staining of Ki67, and photomicrographs were taken as described in Materials and Methods. Proliferation index was calculated as the number of Ki67-positive cells x 100/total number of cells counted under x200 magnification in five randomly selected areas in each tumor sample. (C) Apoptotic cell population in tissues from various group swas analyzed by TUNEL assay as described inMaterials and Methods. Apoptotic index was calculated as the number of positive cells x 100 / total number of cells counted under x200 magnification in five randomly selected areas in each tumor sample. Mean ± SE from eightmice in each group. (D) Immunostaining of survivin in tumor sections from the indicated treatment groups. Original magnification, x200.

To examine whether these treatments affected cell proliferation and apoptosis in in vivo situations, tumor xenograft tissue sections were analyzed by immunohistochemistry for Ki67, a marker for cell proliferation, and TUNEL, a marker for apoptotic response (Figure 6B). As shown in Figure 6C, compared with controls, xenograft samples from docetaxel alone and lycopene supplement-plus-docetaxel groups showed a marked increase in number of TUNEL-positive cells. Quantitative evaluation of apoptosis showed that docetaxel (10 mg/kg per week) alone and docetaxel-plus-lycopene supplement (15 mg/kg per day) led 12.4% ± 3.2% and 24.6% ± 4.3% apoptotic cells, respectively, compared with control or lycopene supplement alone showing 4.3% ± 1.2% or 5% ± 2.1% apoptotic cells (P values < .01). Docetaxel plus lycopene supplement resulted in an increase in apoptotic cells approximately 98% or 392% more than that of either docetaxel or lycopene supplement alone (P values < .05). The quantification of Ki67-positive cells in tumor sections showed no statistically significant difference among the four different treatment groups (P values < .05). Together, these results suggest that the enhancement of the antitumor efficacy of docetaxel by lycopene supplement may be through mechanisms of apoptosis induction.

These tumor sections were further stained with antisurvivin antibody. Figure 4G shows that tumor sections from mice treated with lycopene alone or lycopene supplement in combination with docetaxel demonstrated significantly less staining of survivin protein, whereas docetaxel alone seemed to slightly increase the staining of survivin in tumor sections.

Discussion

Lycopene has been suggested as a promising nutritional component for the prevention and treatment of PCa [11,15]. As a result, many men with PCa increase their intake of lycopene through dietary supplements [28], although there are no large-scale trials to provide evidence-based clinical practice guidelines [29–32]. In addition, docetaxel has recently become the first-line chemotherapeutic regimen for CRPC patients. Because lycopene is a potent antioxidant, there is a concern whether lycopene could protect tumor cells as well as the healthy cells from oxidative damage generated by docetaxel-based chemotherapy and therefore attenuate the antitumor efficacy of docetaxel [21]. In this study, our data clearly demonstrate that lycopene supplementation can significantly enhance the antitumor efficacy of docetaxel in the regression of established tumors in a CRPC xenograft model. This result should justify further clinical investigation of potential benefits of lycopene and docetaxel combinations for treatment of CRPC patients.

Several in vitro cell culture studies [33] have suggested that androgen-induced increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in prostate epithelial cells may play a key role in prostate cancer occurrence, recurrence, and progression. Therefore, agents that prevent the production and chronic accumulation of ROS might be useful in the treatment of prostate cancer. Venkateswaran et al. [34,35] reported that combinations of antioxidants (i.e., lycopene, vitamin E, and selenium) resulted in a significant reduction in both prostate cancer and liver metastasis in the Lady transgenic mice, although the authors in this article did not examine whether the anti-prostate cancer effects of these antioxidants were due to their antioxidant properties. However, the authors did show that a combination of vitamin E and selenium did not effectively inhibit prostate cancer in the Lady transgenic mice. Consistently, Limpens et al. [36] described that a lycopene and vitamin E combination reduced tumor growth and prostate-specific antigen plasma levels in an orthotopic mouse model of human prostate cancer. Taken together, these studies suggested that lycopene is necessary for the inhibitory effect of this combination on prostate cancer and that nonantioxidant mechanisms are also involved in their antineoplastic actions. Because there are concerns about the use of antioxidants during chemotherapy [21], the ability of lycopene to inhibit cancer growth through nonantioxidant mechanismsmay provide justification for combination therapies involving this agent and cytotoxic drugs like docetaxel.

IGF-IR not only plays a role in prostate carcinogenesis [37,38] but also is elevated in metastatic PCa and is associated with resistance to androgen withdraw [17,18,39]. In addition, maintaining IGF-responsiveness enables PCa survival and growth and is partially acquired through androgen-regulated IGF-IR expression [28]. These results suggest that IGF-IR is a critical target for prevention and treatment of CRPC. Lycopene has been shown to inhibit IGF-I signaling by down-regulation of IGF-I expression and up-regulation of IGF-BPs [13,14,40,41]. In this study, we showed that lycopene exhibited more potent inhibitory effects on the growth of DU145 cells with higher expression levels of IGF-IR than those PCa cell lines (e.g., LNCaP, 22Rv1, LAPC-4, PC-3) with lower expression levels of IGF-IR. Moreover, transfected LNCaP cells stably expressing high levels of IGF-IR were approximately 400-fold more sensitive to lycopene than parental LNCaP cells (IC50 for lycopene in LNCaP/IGF-IR was 0.08 µM vs an IC50 of 36 µM for parental LNCaP cells). Intriguingly, although lycopene has been reported to be accumulated in LNCaP cells to levels that are 4.5 times higher than in DU145 cells [42], the growth-inhibitory effects of lycopene on DU145 cells is approximately seven times more pronounced than that on LNCaP cells (IC50 for DU145 vs LNCaP are 5.1 vs 36 µM). This evidence indicates that IGF-IR levels may be more relevant to the growth-inhibitory effect of lycopene on PCa cell lines than cellular concentrations of lycopene. We hypothesized that lycopene existing in extracellular or membrane compartments may also play a role on IGF-IR activation. Our results confirmed that lycopene increased the expression and secretion of IGF-BP3, which sequesters the IGF-IR ligand. We also showed for the first time that lycopene treatment for only 2 hours can inhibit IGF-I-induced IGF-IR phosphorylation in DU145 cells. This result suggests a direct effect of lycopene on IGF-IR activation. We also showed for the first time that lycopene can inhibit IGF-I-induced IGF-IR phosphorylation in DU145 cells. Further studies are in progress to determine whether lycopene can directly bind to IGF-I or IGF-IR and then inhibit IGF-IR kinase activity.

The general mechanism of IGF-IR activation is to enhance survival and protect cells from apoptosis [16]. In addition, the IGF-IR interacts with, and influences, various signaling molecules such as ER, AR, EGFR, HER-2, and the DNA damage response pathway [16]. Together, these properties of IGF-IR activation provide mechanisms through which it can cause resistance to multiple anticancer therapies including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted therapies [16,25]. Therefore, in general, anticancer therapies targeting the IGF axis are promising approaches for enhancing the efficacy of many conventional cancer therapies, including docetaxel-based chemotherapy [43]. We show here that the synergistic growth-inhibitory effect of lycopene and docetaxel was only found on those PCa cancer cell lines with higher IGF-IR levels. This result provides a clue that CRPC patients with high levels of IGF-IR activity may be most likely to benefit from combined therapy with lycopene and docetaxel.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that docetaxel causes cell death through mitotic catastrophe as well as through caspase-dependent and -independent effects [44–46]. Our study showed that lycopene significantly enhanced the apoptotic effect of docetaxel in PCa both in vitro in cell cultures and in vivo in a xenograft model. The histologic analysis of tumor tissue sections revealed that the combination of lycopene and docetaxel resulted in a significant increase in the number of tumor cells with abnormal DNA condensation and multinucleation, consistent with mitotic catastrophe. Further study showed that the docetaxel and lycopene combination could synergistically downregulate survivin expression both in vitro and in vivo. Survivin is an antiapoptotic protein and plays a role in cell cycle regulation during mitosis [47]. Survivin inhibition, alone or in combination with the other therapies, has been shown to induce or enhance apoptosis and mitotic catastrophe in tumor cells [47]. In addition, survivin is regulated by IGFs and is associated with the resistance to castration and progression in PCa [47–49]. On the basis of evidences described, we can argue that survivin, serving as a critical downstream event for the combined effects of lycopene and docetaxel, may be a useful biomarker for predicting the outcome or response of this combined therapy in clinical studies.

In summary, these data provide a rationale for the clinical investigation of the efficacy and safety profile of lycopene in combination with docetaxel in CRPC patients. In particular, combining lycopene with docetaxel may provide clinical benefit for men with metastatic CRPC, for whom morbidity and mortality remain high despite wide use of docetaxel chemotherapy. The mechanism of this combined therapy seems to involve the IGF-IR/survivin pathway and is mediated by mitotic catastrophe and apoptosis.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute ( grant CA122558 to X.Z.).

References

- 1.Hsing AW, Devesa SS. Trends and patterns of prostate cancer: what do they suggest? Epidemiol Rev. 2001;23:3–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a000792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:34–45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagher R, Li N, Abraham S, Rahman A, Sridhara R, Pazdur R. Approval summary: docetaxel in combination with prednisone for the treatment of androgen-independent hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8147–8151. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haenszel W, Kurihara M. Studies of Japanese migrants. I. Mortality from cancer and other diseases among Japanese in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1968;40:43–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crawford ED. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. Urology. 2003;62(6 suppl 1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Culig Z. Androgen receptor cross-talk with cell signaling pathways. Growth Factors. 2004;22:179–184. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinton SK. Lycopene: chemistry, biology, and implications for human health and disease. Nutr Rev. 1998;56(2 pt 1):35–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell JK, Engelmann NJ, Lila MA, Erdman JW. Phytoene, phytofluene, and lycopene from tomato powder differentially accumulate in tissues of male Fisher 344 rats. Nutr Res. 2007;27:794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wertz K, Siler U, Goralczyk R. Lycopene: modes of action to promote prostate health. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;430:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erdman JW, Jr, Ford NA, Lindshield BL. Are the health attributes of lycopene related to its antioxidant function? Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;483:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giovannucci E, Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Intake of carotenoids and retinol in relation to risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1767–1776. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siler U, Barella L, Spitzer V, Schnorr J, Lein M, Goralczyk R, Wertz K. Lycopene and vitamin E interfere with autocrine/paracrine loops in the Dunning prostate cancer model. FASEB J. 2004;18:1019–1021. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1116fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, Allen JD, Arnold JT, Blackman MR. Lycopene inhibits IGF-I signal transduction and growth in normal prostate epithelial cells by decreasing DHT-modulated IGF-I production in co-cultured reactive stromal cells. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:816–823. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu C, Lian F, Smith DE, Russell RM, Wang XD. Lycopene supplementation inhibits lung squamous metaplasia and induces apoptosis via up-regulating insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 in cigarette smoke-exposed ferrets. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3138–3144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Breemen RB, Pajkovic N. Multitargeted therapy of cancer by lycopene. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:339–351. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casa AJ, Dearth RK, Litzenburger BC, Lee AV, Cui X. The type I insulin-like growth factor receptor pathway: a key player in cancer therapeutic resistance. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3273–3287. doi: 10.2741/2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krueckl SL, Sikes RA, Edlund NM, Bell RH, Hurtado-Coll A, Fazli L, Gleave ME, Cox ME. Increased insulin-like growth factor I receptor expression and signaling are components of androgen-independent progression in a lineage-derived prostate cancer progression model. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8620–8629. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plymate SR, Haugk K, Coleman I, Woodke L, Vessella R, Nelson P, Montgomery RB, Ludwig DL, Wu JD. An antibody targeting the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor enhances the castration-induced response in androgen-dependent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6429–6439. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domingo-Domenech J, Oliva C, Rovira A, Codony-Servat J, Bosch M, Filella X, Montagut C, Tapia M, Campás C, Dang L, et al. Interleukin 6, a nuclear factor-κB target, predicts resistance to docetaxel in hormone-independent prostate cancer and nuclear factor-κB inhibition by PS-1145 enhances docetaxel antitumor activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5578–5586. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng S, Tang Q, Sun M, Chun JY, Evans CP, Gao AC. Interleukin-6 increases prostate cancer cells resistance to bicalutamide via TIF2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:665–671. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawenda BD, Kelly KM, Ladas EJ, Sagar SM, Vickers A, Blumberg JB. Should supplemental antioxidant administration be avoided during chemotherapy and radiation therapy? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:773–783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rehman A, Bourne LC, Halliwell B, Rice-Evans CA. Tomato consumption modulates oxidative DNA damage in humans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;262:828–831. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porrini M, Riso P. Lymphocyte lycopene concentration and DNA protection from oxidative damage is increased in women after a short period of tomato consumption. J Nutr. 2000;130:189–192. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsiao G, Wang Y, Tzu NH, Fong TH, Shen MY, Lin KH, Chou DS, Sheu JR. Inhibitory effects of lycopene on in vitro platelet activation and in vivo prevention of thrombus formation. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;146(4):216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Y, Zi X, Zhao Y, Mascarenhas D, Pollak M. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling and resistance to trastuzumab (Herceptin) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1852–1857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.24.1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zi X, Simoneau AR. Flavokawain A, a novel chalcone from kava extract, induces apoptosis in bladder cancer cells by involvement of Bax protein-dependent and mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway and suppresses tumor growth in mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3479–3486. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobel RE, Sadar MD. Cell lines used in prostate cancer research: a compendium of old and new lines-part 1. J Urol. 2005;173:342–359. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000141580.30910.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmerman RA, Thompson IM., Jr Prevalence of complementary medicine in urologic practice. A review of recent studies with emphasis on use among prostate cancer patients. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kucuk O, Sarkar FH, Sakr W, Djuric Z, Pollak MN, Khachik F, Li YW, Banerjee M, Grignon D, Bertram JS, et al. Phase II randomized clinical trial of lycopene supplementation before radical prostatectomy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:861–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark PE, Hall MC, Borden L, Jr, Miller AA, Hu JJ, Lee WR, Stindt D, D'Agostino R, Jr, Lovato J, Harmon M, et al. Phase I-II prospective dose-escalating trial of lycopene in patients with biochemical relapse of prostate cancer after definitive local therapy. Urology. 2006;67:1257–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ansari MS, Gupta NP. A comparison of lycopene and orchidectomy vs orchidectomy alone in the management of advanced prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2003;92:375–378. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwenke C, Ubrig B, Thürmann P, Eggersmann C, Roth S. Lycopene for advanced hormone refractory prostate cancer: a prospective, open phase II pilot study. J Urol. 2009;181:1098–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehraein-Ghomi F, Lee E, Church DR, Thompson TA, Basu HS, Wilding G. JunD mediates androgen-induced oxidative stress in androgen dependent LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2008;68:924–934. doi: 10.1002/pros.20737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venkateswaran V, Fleshner NE, Sugar LM, Klotz LH. Antioxidants block prostate cancer in Lady transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5891–5896. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venkateswaran V, Klotz LH, Ramani M, Sugar LM, Jacob LE, Nam RK, Fleshner NE. A combination of micronutrients is beneficial in reducing the incidence of prostate cancer and increasing survival in the Lady transgenic model. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:473–483. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Limpens J, Schröder FH, de Ridder CM, Bolder CA, Wildhagen MF, Obermüller-Jevic UC, Krämer K, van Weerden WM. Combined lycopene and vitamin E treatment suppresses the growth of PC-346C human prostate cancer cells in nude mice. J Nutr. 2006;136:1287–1293. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.5.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DiGiovanni J, Kiguchi K, Frijhoff A, Wilker E, Bol DK, Beltrán L, Moats S, Ramirez A, Jorcano J, Conti C. Deregulated expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 in prostate epithelium leads to neoplasia in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3455–3460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hellawell GO, Turner GD, Davies DR, Poulsom R, Brewster SF, Macaulay VM. Expression of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor is upregulated in primary prostate cancer and commonly persists in metastatic disease. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2942–2950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Genua M, Pandini G, Sisci D, Castoria G, Maggiolini M, Vigneri R, Belfiore A. Role of cyclic AMP response element-binding protein in insulin-like growth factor-I receptor up-regulation by sex steroids in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7270–7277. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riso P, Brusamolino A, Martinetti A, Porrini M. Effect of a tomato drink intervention on insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 serum levels in healthy subjects. Nutr Cancer. 2006;55:157–162. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5502_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graydon R, Gilchrist SE, Young IS, Obermüller-Jevic U, Hasselwander O, Woodside JV. Effect of lycopene supplementation on insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3: a double-blind, placebocontrolled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61:1196–1200. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu A, Pajkovic N, Pang Y, Zhu D, Calamini B, Mesecar AL, van Breemen RB. Absorption and subcellular localization of lycopene in human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2879–2885. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Bono JS, Attard G, Adjei A, Pollak MN, Fong PC, Haluska P, Roberts L, Melvin C, Repollet M, Chianese D, et al. Potential applications for circulating tumor cells expressing the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3611–3616. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fabbri F, Amadori D, Carloni S, Brigliadori G, Tesei A, Ulivi P, Rosetti M, Vannini I, Arienti C, Zoli W, et al. Mitotic catastrophe and apoptosis induced by docetaxel in hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217:494–501. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mediavilla-Varela M, Pacheco FJ, Almaguel F, Perez J, Sahakian E, Daniels TR, Leoh LS, Padilla A, Wall NR, Lilly MB, et al. Docetaxel-induced prostate cancer cell death involves concomitant activation of caspase and lysosomal pathways and is attenuated by LEDGF/p75. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:68. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castedo M, Perfettini JL, Roumier T, Andreau K, Medema R, Kroemer G. Cell death by mitotic catastrophe: a molecular definition. Oncogene. 2004;23(16):2825–2837. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang M, Latham D, Delaney M, Chakravarti A. Survivin mediates resistance to antiandrogen therapy in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:2474–2482. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vaira V, Lee C, Goel H, Bosari S, Languino L, Altieri D. Regulation of survivin expression by IGF-1/mTOR signaling. Oncogene. 2007;26:2678–2684. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shariat S, Lotan Y, Saboorian H, Khoddami SM, Roehrborn CG, Slawin KM, Ashfaq R. Survivin expression is associated with features of biologically aggressive prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;100:751–757. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]