Abstract

PURPOSE

To assess the long-term biocompatibility and photochromic stability of a new photochromic hydrophobic acrylic intraocular lens (IOL) under extended ultraviolet (UV) light exposure.

SETTING

John A. Moran Eye Center, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA.

DESIGN

Experimental study.

METHODS

A Matrix Aurium photochromic IOL was implanted in right eyes and a Matrix Acrylic IOL without photochromic properties (n = 6) or a single-piece AcrySof Natural SN60AT (N = 5) IOL in left eyes of 11 New Zealand rabbits. The rabbits were exposed to a UV light source of 5 mW/cm2 for 3 hours during every 8-hour period, equivalent to 9 hours a day, and followed for up to 12 months. The photochromic changes were evaluated during slitlamp examination by shining a penlight UV source in the right eye. After the rabbits were humanely killed and the eyes enucleated, study and control IOLs were explanted and evaluated in vitro on UV exposure and studied histopathologically.

RESULTS

The photochromic IOL was as biocompatible as the control IOLs after 12 months under conditions simulating at least 20 years of UV exposure. In vitro evaluation confirmed the retained optical properties, with photochromic changes observed within 7 seconds of UV exposure. The rabbit eyes had clinical and histopathological changes expected in this model with a 12-month follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

The new photochromic IOL turned yellow only on exposure to UV light. The photochromic changes were reversible, reproducible, and stable over time. The IOL was biocompatible with up to 12 months of accelerated UV exposure simulation.

Studies suggest that blue light-filtering intraocular lenses (IOLs) protect lipofuscin-containing retinal pigment epithelial cells from blue-light damage. There is indirect evidence showing that this may result in a reduced risk for macular degeneration or its progression.1–4 Therefore, blue light–filtering IOLs have become part of the modern cataract surgeon's armamentarium and are currently widely used.5,6 However, there is controversy in the literature over the value of these yellow-chromophore IOLs. Furthermore, potential side effects of constantly filtering blue light include a negative impact on color vision, night vision, and sleep and circadian rhythms.7–16

A new photochromic IOL developed by Medennium (Matrix Aurium) has an ultraviolet (UV)-visible absorption curve similar to the AcrySof Natural IOL (Alcon Laboratories, Inc.) when exposed to UV light. Under photopic conditions, the optic of the IOL turns yellow in color and blue light is absorbed. The IOL behaves as a standard UV–filtering IOL in an indoor environment when the optic of the IOL is colorless with no filtering of blue light. This concept theoretically eliminates the potential side effects of yellow IOLs, while patients still benefit from improved night vision after cataract surgery, additional protection to the macula against blue light in daylight conditions, and improved contrast sensitivity, as shown in clinical studies of yellow IOLs.17

In a previous in vivo study, rabbits eyes with the photochromic IOL were exposed to UV light for 1 hour daily and followed for 6 months, with histopathologic evaluation thereafter. The photochromic property of the IOL was found to be reversible, reproducible, stable over time, and unchanged after the 6-month implantation period.17 In vitro tests simulating up to 23 years of in vivo intraocular exposure to UV light according to specifications by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards18 also showed long-term stability of the photochromic property. In the current in vivo study, we evaluated the biocompatibility and photochromic stability of the Matrix Aurium IOL during a 12-month implantation period with 9 hours of UV light exposure a day. The conditions used in this study represent an accelerated 20-year sunlight exposure simulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Matrix Aurium is a photochromic foldable IOL with a proprietary hydrophobic acrylic material. The design available for this study was 3-piece with blue polyvinylidene fluoride haptics. The overall diameter of the IOL was 12.5 mm and the optic, 6.0 mm. The IOL had a 5-degree posterior optic–haptic angulation and square optic edges. Transmission spectra of the IOL, obtained before and after projection of UV light, were provided in a previous study.17

In Vivo Study

Eleven New Zealand white rabbits weighing between 2.4 kg and 3.2 kg were acquired from approved vendors and treated in accordance with guidelines set forth by the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology. Eleven study IOLs (Matrix Aurium) were used in this study. There were 2 groups of control IOLs. Control IOL 1 was a 3-piece hydrophobic Matrix Acrylic (n = 6), the counterpart of the photochromic IOL except without the photochromic property. Control IOL 2 was a commercially available 1-piece hydrophobic acrylic model (n = 5) with an incorporated blue-light filter (AcrySof Natural SN60AT, Alcon Laboratories, Inc.). The control IOLs had the same dioptric power as the study IOL (+21.00 diopters). The study IOL was implanted in the right eye of each rabbit, and the control IOLs were randomized for implantation in the left eye.

The same surgeon (N.M.) performed all phacoemulsification with IOL implantation procedures as described in previous studies. Briefly, a 3.2 mm partial-thickness superior limbal incision was made. After sodium hyaluronate 1.6% (Amvisc Plus) was injected, a forceps was used to create a capsulorhexis with a diameter aimed at 5.0 mm. After hydrodissection, phacoemulsification (Alcon CooperVision Series 10 000) was performed. Next, 0.5 half mL of epinephrine 1:1000 and 0.5 mL of heparin (10 000 USP units/mL) were added to each 500 mL of irrigation solution to maintain pupil dilation and control inflammation. After reinjection of the same ophthalmic viscosurgical device (OVD), the incision size was increased to 3.5 mm and the IOLs (study and controls) were folded with the appropriate forceps and implanted in the capsular bag. The wound was closed with 10-0 monofilament nylon suture after the OVD was removed. Correct in-the-bag IOL placement and centration and 360-degree coverage of the IOL optic by the capsulorhexis were verified at the end of the procedure.

The UV light installed in the rabbit room was in standard fluorescent-light housing with a ballast holding 40 W black-light bulbs with a T12 shape (120 cm long, 4 cm diameter, Philips Electronics) delivering up to 5 mW/cm2 of 365 nm light. The rabbits were housed in 6-bank racks, with 2 cages per level. The sources were fixed to the wall in front of the rabbit cages in a vertical position approximately 60 cm from the cages to ensure that each animal would be exposed to the same amount of UV light. Throughout the follow-up period, the UV light sources were programmed to turn on for 3 hours in every 8-hour period, equivalent to 9 hours of UV light exposure in a 24-hour period. The calculation for the exposure period was based on the ISO guidelines.19 On a sunny day, an IOL is exposed to UVA intensity (I1) of 0.3 mW/cm2. The rabbits were exposed to an intensity of 5 mW/cm2. The ISO standard states that 40% to 50% of UVA is absorbed by the cornea and aqueous, leaving an exposure of 2.5 mW/cm2 (I2) for the IOLs. The standard sets a typical daylight exposure period of 3 hours (Et1) and the rabbits were exposed to UVA light for 9 hours (Et2). An intensity factor, n, of 1 is used, related to normal or standard solar light exposure while standing on the ground. The calculation gives the study time, T2, required to simulate 20 years of sunlight exposure for an IOL (T1):

Using the set of assumptions given in ISO 11979-5, 2006,19 a test period of 12 months is actually equivalent to 25 years. A conservative approach was used in this study in that the study IOLs had UVA exposure equivalent to at least 20 years in a human eye.

The eyes were evaluated by slitlamp examination for ocular inflammatory response 1, 2, and 3 weeks postoperatively as well as at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months. The follow-up period was extended an additional 6 months because ophthalmologic and veterinary examinations of the rabbits concluded that nothing contraindicated the extension. Slitlamp examinations were therefore also performed at 8, 10, and 12 months in addition to the biweekly sign-off of the rabbits' general health conditions by a veterinary physician. A standard scoring method in specific categories was used at each examination. The examination included assessment of corneal edema and the presence of cell and flare in the anterior chamber. Posterior capsule opacification (PCO) development was also assessed at each slitlamp examination during the first 4 weeks and scored from grade 0 to grade 4. Clinical color photographs of each eye with the pupil fully dilated were obtained with a digital camera coupled to the slitlamp at each time point. The photographs of the eyes with the study IOLs were obtained without and then with the presence of a UV light source projected onto the IOL. The UV light source was a penlight (MicroLux-UV, Electro-Lite Corp.) placed 5 cm in front of the eye. It delivers up to 20 mW/cm2 at 365 nm via a UV light-emitting diode. The time required for the photochromic change to occur in the study IOL was recorded as well.

Postmortem Study

After a follow-up of 12 months, the animals were anesthetized and then humanely killed with a 1.0 mL intravenous injection of pentobarbital sodium–phenytoin sodium. Their globes were enucleated and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 24 hours. The globes were sectioned in a coronal plane just anterior to the equator. The same penlight used during slitlamp examination was used to assess photochromic changes in the study IOLs in the postmortem examination from a posterior or Miyake-Apple view of the anterior segment. The IOLs were then carefully removed from the capsular bag and the globes processed for standard light microscopy and stained with hematoxylin–eosin, periodic acid-Schiff stain, and Masson trichrome. The analyses of the sections focused on the presence of inflammatory cellular reactions, necrosis, cell vacuolization, and other indicators in different intraocular structures.

Representative explanted study and control IOLs (2 of each type) were evaluated for surface cell reactions using a modified implant cytology technique. Briefly, the IOLs were placed in formalin and then in 70% alcohol (30 seconds). They were then immersed in hematoxylin (2 minutes), washed in running water for 10 seconds, and immersed in eosin (2 minutes). They were subsequently immersed in 100% alcohol (3 seconds) and xylene (30 seconds) and then fixed on a glass slide with mounting media and covered with a cover slip.

The remaining explanted IOLs were sent back to the manufacturer in vials containing sterile distilled water for further analyses. The optical surfaces were thoroughly cleaned using foam swabs after short ultrasonic agitation in a mild 2% detergent solution. Optical properties were evaluated in accordance with ISO 11979-5, 200619 and ISO 11979-2, 1979.20 The IOLs were evaluated using an FS-3 slitlamp (Nikon Corp.) after equilibration for 72 hours in aqueous at 37°C. They were then analyzed with a Cary 3 UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Varian, Inc.) using an integrating sphere accessory. The cleaned IOLs were placed in a cuvette fixture with a 3.0 mm aperture and scanned from 800 to 300 nm wavelength to collect the light-transmission curve. Photochromic IOLs were exposed to 365 nm wavelength light (UVA) at an intensity of 1 mW/cm2 for 30 seconds to activate the photochromic color change. To retard rapid recovery of the optic to the colorless form, the IOLs were frozen with a short blast of liquid 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane. They were then scanned from 600 to 300 nm to collect a light-transmission curve at the activated yellow state.

RESULTS

All surgeries were uneventful. The IOLs were well centered, with the haptics oriented at 3 o'clock and 9 o'clock. They were symmetrically fixated in the bag with 360-degree capsulorhexis overlap of the periphery of the optic. During the first postoperative week, the eyes generally had superior corneal edema and mild flare and cells, which usually resolved by the 2-week examination. One eye with control IOL 1 developed endophthalmitis during the first postoperative week. The rabbit was humanely killed and excluded from the study.

At the 4-week examination, the mean PCO score was 0.9 ± 0.96 (SD) for the study IOL, 1.0 ± 0.93 for control IOL 1, and 1.6 ± 1.14 for control IOL 2; the differences between the 3 groups were not statistically significant because of the small sample size (P = .4623, Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test). When PCO was observed with control IOL 2, it had a tendency to start at the level of the optic–haptic junctions, which was not observed with the study IOL or control IOL 1. Evaluation of PCO formation was usually inconclusive after the 4-week examination because the rabbit has an accelerated proliferative and regenerative capacity. No anterior capsule opacification was observed in any group up to 4 weeks; however, in general, this parameter could not be assessed after this time point. Posterior synechiae and inflammatory deposits on the IOL surfaces (generally giant cells) started to appear at the 4-week examination and were progressively more significant in all groups of IOLs. The IOLs in all groups were well centered up to 4 weeks. However, a progressive increase in capsule bag opacification as well as synechia formation led to IOL decentration and tilt, iris bombe, and IOL optic capture by the pupil in some eyes in all groups.

The color change in the study IOLs was difficult to appreciate under slitlamp examination up to 4 weeks because of the bright red reflex in albino rabbit eyes. The whitish background provided by PCO formation observed in the majority of eyes, especially from the 2-month examination on, made it significantly easier to appreciate the color change in the study IOL. In most cases, the color change occurred within 5 seconds of UV exposure with the penlight (Figure 1). Even though appreciation of the color change was more difficult at 12 months because of factors such as synechiae and iris bombe, the change could still be observed and occurred within 6 seconds in 7 of 10 study IOLs and within 9 or 13 seconds in the other 3. Postmortem gross analysis of the eyes from the Miyake-Apple view confirmed that all IOLs were fixated in the capsular bag. Before penlight exposure with UV light, all study IOLs appeared colorless. Photochromic changes were observed in as fast as 2 seconds in 1 eye, 4 seconds in 6 eyes, 6 seconds in 2 eyes, and 7 seconds in 1 eye (Figure 2).

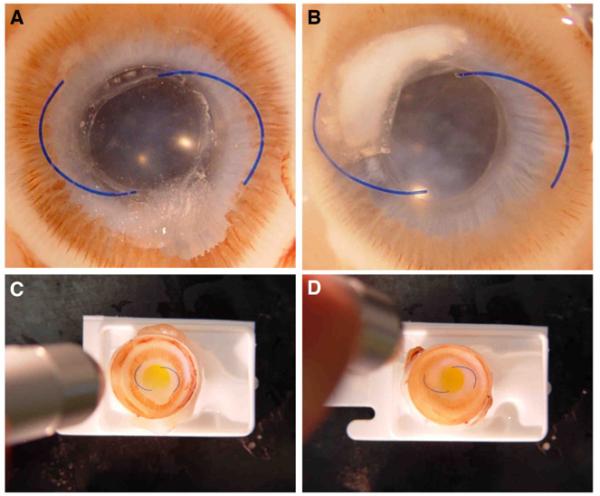

Figure 1.

Slitlamp photographs obtained 10 months after implantation of the study and control IOLs in rabbit eyes. A and B: Eyes with a study IOL before UV light projection. C and D: Same eyes during the UV light projection (purple reflex). The PCO formation in both eyes, by impairing the red reflex, made observation and documentation of the IOL photochromic change easier.

Figure 2.

Postmortem gross photographs obtained at the end of the clinical follow-up period (12 months). A and B: Miyake-Apple view of eyes with a study IOL before UV light projection. C and D: Same eyes during the UV light projection, causing IOL photochromic change (from colorless to yellow optics). The penlight UV source can be seen on the left of each photograph.

Analyses of multiple histopathologic sections obtained from eyes in all groups showed no sign of untoward inflammatory reaction or toxicity in different intraocular structures, including the cornea, iris, ciliary body, lens capsule, and retina. The cornea and anterior segment in all of the eyes were intact and showed no signs of inflammatory changes. The anterior chamber was deep in most of the eyes, although there was obliteration of the peripheral anterior chamber in eyes that had significant posterior synechia with iris bombe formation. The iris showed signs of posterior synechia formation with adherence to the remnant anterior lens capsule in many of the eyes in all groups. There were no significant differences in posterior synechia formation between eyes with the study IOL and eyes in the 2 control IOL groups.

Examination of the explanted IOLs prepared according to the modified implant cytology technique under light microscopy showed a moderate amount of giant cells on the surface of all IOLs in all groups. There were also some epithelioid cells and fibroblast-like cells on the surface of the IOLs. There were no differences between the 3 IOL groups in cell deposits.

In vitro evaluation of the explanted IOLs confirmed that the photochromic change occurred within 7 seconds of UV exposure in all study IOLs (Figure 3). The optical properties of the explanted IOLs were measured and found to be within the norm for IOLs, meeting the product specifications. The IOL power, resolution efficiency, UV-filtering properties, clarity, and the photochromic color-switching properties were unchanged for the photochromic IOLs at the end of the study. Table 1 shows the optical properties measured for 6 explanted photochromic IOLs and 1 of each control IOL.

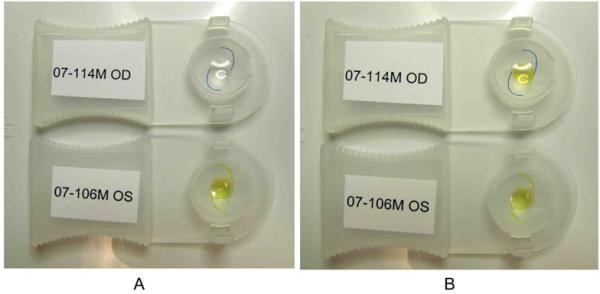

Figure 3.

Gross photographs of explanted study IOL (top) and control IOL 2 (bottom) before (A) and immediately after (B) exposure of the IOLs to an UV penlight for 7 seconds.

Table 1.

Optical properties of the photochromic IOLs after 1 year implantation in a rabbit model.

| Power (D) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOL | Labeled | Measured | Resolution (% of Theoretical) | % Transmission at 550 nm | UV Cutoff (nm) | %Transmission at 440 nm After UV Exposure* |

| Photochromic 1 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 70 | 96.6 | 384.3 | 34.6 |

| Photochromic 2 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 70 | 90.0 | 384.6 | 33.8 |

| Photochromic 3 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 70 | 90.0 | 384.4 | 26.7 |

| Photochromic 4 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 83 | 95.8 | 384.1 | 24.1 |

| Photochromic 5 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 70 | 90.0 | 383.3 | 28.1 |

| Photochromic 6 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 70 | 96.2 | 384.2 | 26.8 |

| Control IOL 1 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 83 | 96.0 | 383.7 | 92.6† |

| Control IOL 2 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 70 | 90.0 | 403.7 | 37.8‡ |

IOL = intraocular lens; UV = ultraviolet

Exposure to ultraviolet light intensity of 1 mW/cm2 for 30 seconds, comparable to midday intensity outdoors in Southern California

Colorless IOL

Permanently yellow IOL

Slitlamp examination and spectrophotometry showed no signs of calcification or other absorbed foreign materials in the explanted IOLs and no evidence of discoloration, opacities, infiltrates, or glistenings in the photochromic explants. Light transmission measured in a model eye with a laser light source at 550 nm was 90% or greater. No changes were observed in the light-transmission curve for the clear and activated photochromic IOLs when compared with non-aged photochromic IOLs after 1 year of intraocular implantation. The mean light transmission in the blue spectral region was 32.1% after UV activation of the explanted photochromic IOLs, comparable to the 37.8% light transmission for the yellow control IOL (Figure 4). There was no significant alteration in the rate of color change between the colorless and yellow forms after the IOLs were exposed to UV light equivalent to 20 years of sunlight exposure. There was no evidence of photobleaching or increased yellowness of the colorless unactivated form of the IOL.

Figure 4.

Light-transmission curves of the explanted IOLs 1 year after implantation in a rabbit model simulating 20 years of UV light exposure. Mean curves for the colorless and activated photochromic IOLs were calculated from the data for 5 explanted IOLs.

DISCUSSION

This is the second rabbit study we have performed to assess the biocompatibility and photochromic stability of the Matrix Aurium IOL. In the previous study,17 the IOLs were implanted in the right eye of 6 New Zealand rabbits. The left eyes had implantation of an AcrySof SA60AT or AcrySof Natural SN60AT IOL (3 each). The same type of UV light source was installed in the rabbit room throughout the study and turned on for 1 hour daily. After a clinical follow-up of 6 months, the rabbits were humanely killed and their eyes enucleated. Three study IOLs and 2 control AcrySof Natural SN60AT IOLs were evaluated in vitro on UV exposure after explantation. The other IOLs and the rabbit eyes had a histopathologic examination. The photochromic change was observed on UV light exposure throughout the clinical follow-up of 6 rabbits as well as after explantation of the IOLs. Postoperative clinical inflammatory reactions and cellular reactions on the surface of the explanted IOLs were similar in the study group and the control group. No sign of untoward toxicity was observed in the histopathologic sections of the rabbit eyes in any group.

The conditions used in this study (1-year follow-up with 9 hours of UV light exposure/day) represent accelerated sunlight-exposure simulation of at least 20 years, according to the standards set by ISO 11979-5, 2006.19 The results were similar to those in the previous in vivo 6-month study,17 which found biocompatibility of the IOL material and no fatigue of its photochromic property. Findings such as posterior synechiae, inflammatory deposits on IOL surfaces, capsular bag opacification, IOL decentration, iris bombe, or IOL optic capture were observed in some eyes in all groups by the end of the follow-up period. These are not uncommonly observed in long-term rabbit studies because the inflammatory and proliferative reactions in this animal model are exacerbated in relation to the human eye.21,22 Heparin must be used intraoperatively in phacoemulsification studies because disruption of the blood–aqueous barrier causes massive protein release into the anterior chamber in this animal.21,22 A series of studies by Gwon et al.23–26 showed the great potential for lens epithelial cells of rabbits to proliferate, even in the absence of IOL implantation. This was so evident in some cases that actual lens regeneration was observed in the late postoperative period (8 months). The regeneration and proliferation of the material are also accelerated, and 6 to 8 weeks in the rabbit eye corresponds to approximately 2 years in the human eye.

Our current results also confirmed the results in previous in vitro testsA performed in aged (equivalent to 23 years of in vivo intraocular exposure to UV light) IOLs before and after neodymium:YAG (Nd:YAG) laser application, according to specifications by the ISO 11979 standard. Fifteen photochromic IOLs were placed in UV-grade quartz tubes with balanced salt solution at 37°C and were irradiated with a xenon lamp. The irradiance level of the xenon lamp (close to solar spectrum) was set to 25 mW/cm2 in 300 to 400 nm. The irradiation was applied for 3 hours, followed by a 1-hour dark period; light and dark phases cycled continuously for 28 days. Spectrophotometry of the balanced salt solution did not show the presence of leachable substances. The IOLs were clear without haze, vacuoles, or microcracks under slitlamp inspection. Light-transmission curves of the aged IOLs were comparable with those of to non-aged IOLs.

In another in vitro test,B 5 aged and 5 non-aged photochromic IOLs were evaluated with an Nd:YAG laser test. Each IOL was immersed in an optical cuvette containing 2 mL of a balanced salt solution. Using an energy setting of 5 mJ, the Nd:YAG laser was focused on the posterior optic surface and each IOL was exposed to 50 single pulses, spread evenly over the central optical zone. The IOLs were removed from the cuvette, and the balanced salt solution from the aged group and that from the non-aged IOL group were submitted separately for analysis of released substances. The photochromic properties of the aged IOLs and non-aged IOLs were evaluated after laser application and the results compared with those of photochromic IOLs that were not treated with the Nd:YAG laser. The balanced salt solution from aged and non-aged IOL samples showed no signs of toxicity in cell culture. No fragmented polymer or photochromic dye residues were found on spectrophotometry. The photochromic analysis showed that the photochromic properties were not lost in the laser-treated groups compared with the non-treated group.

It is not known whether the exact amount of energy that reached the rabbit eyes in the current study was the exact amount delivered because no measurements were performed. The conclusion that the photochromic properties do not change over the long-term is supported by the above-mentioned in vitro studies, which can be considered the worst-case scenario in terms of UV light exposure. However, an in vitro study cannot fully mimic the complex interactions between an implant and physiologic active intraocular tissues. Therefore, an in vivo study was necessary to complement the in vitro information.

According to the IOL's manufacturer, the change in the dye molecule responsible for the change in optic color under UV exposure occurs in seconds with ease because of the soft nature of the hydrophobic acrylic material used in the manufacture of this IOL. The optic color change occurs much slower (minutes) and with hindrance in sunglasses manufactured from rigid materials, which also contributes to their fatigue with a use life of approximately 5 years before the photochromic properties are lost. Other factors that contributes to the significantly shorter photochromic stability of sunglasses is their extraocular situation, with direct exposure to sunlight and high oxygen concentrations in air leading to faster material degradation, free radical generation, and oxidative decomposition.27,28

This IOL received European Conformité Européenne mark approval in April 2007 and is commercially available overseas in more than 23 countries in a 3-piece design with polyvinylidene fluoride haptics. In a prospective comparative clinical study of 15 patients in Mexico,C the Matrix Aurium IOL was randomly selected to be implanted in 1 eye and an AcrySof SN60WF IOL (yellow aspheric IOL, Alcon Laboratories, Inc.) in the other eye. The corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) in each eye was measured using Snellen charts under various lighting conditions. The authors found that although the CDVA with both IOLs increased with increasing illumination levels, the Matrix Aurium outperformed the SN60WF under low-level illumination conditions (from 11 to 500 lux). When CDVA was measured outdoors under sunlight, use of UV-filtering sunglasses was associated with a more significant reduction in CDVA in the AcrySof SN60WF group.C We are not aware of clinical studies comparing the CDVA between the Matrix Aurium IOL and a non-chromophore conventional IOL under low-light conditions.

In summary, this study simulated accelerated 20-year sunlight exposure of the Matrix Aurium photochromic IOL in the rabbit model. The photochromic change was found to be reversible (the optic returned to colorless after discontinuation of UV light projection) and reproducible (the photochromic change was observed at different time points in the clinical follow-up). Also, the photochromic property of the optic material was stable over time and was still present and unchanged after a 12-month implantation period. The rabbit eyes had clinical and histopathological changes that are normally expected in this model with a long follow-up, and there was no difference between study eyes and control eyes in biocompatibility.

Synopsis.

Photochromic changes under ultraviolet light of a new photochromic IOL were reversible, reproducible and stable over time during a 1-year rabbit study simulating at least 20 years of sunlight exposure.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc, New York, New York, to the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, University of Utah, and by a research grant from Medennium Inc., Irvine, California, USA. Preclinical development by Medennium Inc. was funded by an SBIR grant from the National Eye Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Biography

Footnotes

Mary Mayfield, HT, John A. Moran Eye Center, University of Utah, assisted with the histopathologic preparations

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the ASCRS Symposium on Cataract, IOL and Refractive Surgery, San Francisco, California, USA, April 2009

Financial Disclosure: No author has a financial or proprietary interest in any material or method mentioned. Additional financial disclosures are found in the footnotes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sparrow JR, Miller AS, Zhou J. Blue light-absorbing intraocular lens and retinal pigment epithelium protection in vitro. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:873–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sparrow JR, Nakanishi K, Parish CA. The lipofucsin fluorophore A2E mediates blue light-induced damage to retinal pigmented epithelial cells. [Accessed October 8, 2010];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000 41:1981–1989. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/cgi/content/full/41/7/1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Group Risk factors associated with age-related macular degeneration; a case-control study in the age-related eye disease study: Age-Related Eye Disease Study Report number 3. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:2224–2232. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00409-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van der Schaft TL, Mooy CM, de Bruijn WC, Mulder PGH, Pamever JH, de Jong PTVM. Increased prevalence of disciform macular degeneration after cataract extraction with implantation of an intraocular lens. [Accessed October 8, 2010];Br J Ophthalmol. 1994 78:441–445. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.6.441. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC504819/pdf/brjopthal00030-0019.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuthbertson FM, Peirson SN, Wulff K, Foster RG, Downes SM. Blue light-filtering intraocular lenses: review of potential benefits and side effects. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:1281–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernest PH. Light-transmission-spectrum comparison of foldable intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:1755–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2003.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mester U, Holz F, Kohnen T, Lohmann C, Tetz M. Intraindividual comparison of a blue-light filter on visual function: AF-1 (UY) versus AF-1 (UV) intraocular lens. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah SA, Miller KM. Explantation of an AcrySof natural intraocular lens because of a color vision disturbance. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:941–942. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodríguez-Galietero A, Montés-Micó R, Muñoz G, Albarrán-Diego C. Blue-light filtering intraocular lens in patients with diabetes: contrast sensitivity and chromatic discrimination. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:2088–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ao M, Chen X, Huang C, Li X, Hou Z, Chen X, Zhang C, Wang W. Color discrimination by patients with different types of light-filtering intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niwa K, Yoshino Y, Okuyama F, Tokoro T. Effects of tinted intraocular lens on contrast sensitivity. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1996;16:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mainster MA. Intraocular lenses should block UV radiation and violet but not blue light. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:550–555. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.4.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mainster MA, Sparrow JR. How much blue light should an IOL transmit? [Accessed October 8, 2010];Br J Ophthalmol. 2003 87:1523–1529. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.12.1523. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1920564/pdf/bjo08701523.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pons A, Delgado D, Campos J. Determination of the action spectrum of the blue-light hazard for different intraocular lenses. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2007;24:1545–1550. doi: 10.1364/josaa.24.001545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Gelder RN. Blue light and the circadian clock [letter] [Accessed October 8, 2010];Br J Ophthalmol. 2004 88:1353. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.042861/045120. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1772367/pdf/bjo08801353.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mainster MA. Violet and blue light blocking intraocular lenses: photoprotection versus photoreception. [Accessed October 8, 2010];Br J Ophthalmol. 2006 90:784–792. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.086553. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1860240/pdf/784.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner L, Mamalis N, Romaniv N, Haymore J, Haugen B, Hunter B, Stevens S. New photochromic foldable intraocular lens: preliminary study of feasibility and biocompatibility. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:1214–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.01.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Organization for Standardization . Ophthalmic Implants – Intraocular Lenses – Part 2: Optical Properties and Test Methods. ISO; Geneva, Switzerland: 1979. pp. ISO 11979–2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.International Organization for Standardization . Ophthalmic Implants – Intraocular Lenses – Part 5: Biocompatibility. ISO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2006. pp. ISO 11979–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Organization for Standardization . Ophthalmic Implants – Intraocular Lenses – Part 2: Optical Properties and Test Methods. ISO; Geneva, Switzerland: 1999. pp. ISO 11979–2. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner L, Chew J, Mamalis N. Experimental evaluation of ophthalmic devices and solutions using rabbit models. Vet Ophthalmol. 2006;9:281–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2006.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bito LZ. Species differences in the responses of the eye to irritation and trauma: a hypothesis of divergence in ocular defense mechanisms, and the choice of experimental animals for eye research. Exp Eye Res. 1984;39:807–829. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(84)90079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gwon AE, Gruber L, Mundwiler E. A histologic study of lens regeneration in aphakic rabbits. [Accessed October 8, 2010];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990 31:540–547. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/cgi/reprint/31/3/540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gwon AE, Jones RL, Gruber LJ, Mantras C. Lens regeneration in juvenile and adult rabbits measured by image analysis. [Accessed October 8, 2010];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992 33:2279–2283. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/cgi/reprint/33/7/2279.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gwon A, Gruber L, Mantras C, Cunanan C. Lens regeneration in New Zealand albino rabbits after endocapsular cataract extraction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:2124–2129. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/cgi/reprint/34/6/2124.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gwon A, Gruber LJ, Mantras C. Restoring lens capsule integrity enhances lens regeneration in New Zealand albino rabbits and cats. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1993;19:735–746. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dubest R, Levoir P, Meyer JJ, Aubard J, Baillet G, Giusti G, Guglielmetti R. Computer-controlled system designed to measure photodegradation of photochromic compounds. Rev Sci Instrum. 1993;64:1803–1808. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maeda S. Spirooxazines. In: Crano JC, Gulielmetti RJ, editors. Organic Photochromic and Thermochromic Compounds. Volume 1: Main Photochromic Families. Plenum Press; New York, NY: 1999. pp. 96–110. [Google Scholar]

Other Cited Material

- A.Werner L, Mamalis N, Wilcox C, Zhou S. In Vitro and in Vivo Studies for Evaluation of the Matrix Acrylic Aurium Photochromic Intraocular Lens. XXV Congress of the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons; Stockholm, Sweden. September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- B.Brubaker JW, Espandar L, Davis DK, Wilcox C, Mamalis N. Stability of a Novel Photochromic IOL After Simulated 20 Years in the Eye Using Nd:YAG Laser Exposure Test. ASCRS Symposium on Cataract, IOL and Refractive Surgery; Chicago, Illinois, USA. April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- C.Méndez D, Méndez A. First Photochromic Intraocular Lens (Matrix Acrylic Aurium) – Two Year Clinical Experience in Humans. annual meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology; Atlanta, Georgia, USA. November 2008. [Google Scholar]