Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni is a gastrointestinal pathogen that is able to modify membrane and periplasmic proteins by the N-linked addition of a 7-residue glycan at the strict attachment motif (D/E)XNX(S/T). Strategies for a comprehensive analysis of the targets of glycosylation, however, are hampered by the resistance of the glycan-peptide bond to enzymatic digestion or β-elimination and have previously concentrated on soluble glycoproteins compatible with lectin affinity and gel-based approaches. We developed strategies for enriching C. jejuni HB93-13 glycopeptides using zwitterionic hydrophilic interaction chromatography and examined novel fragmentation, including collision-induced dissociation (CID) and higher energy collisional (C-trap) dissociation (HCD) as well as CID/electron transfer dissociation (ETD) mass spectrometry. CID/HCD enabled the identification of glycan structure and peptide backbone, allowing glycopeptide identification, whereas CID/ETD enabled the elucidation of glycosylation sites by maintaining the glycan-peptide linkage. A total of 130 glycopeptides, representing 75 glycosylation sites, were identified from LC-MS/MS using zwitterionic hydrophilic interaction chromatography coupled to CID/HCD and CID/ETD. CID/HCD provided the majority of the identifications (73 sites) compared with ETD (26 sites). We also examined soluble glycoproteins by soybean agglutinin affinity and two-dimensional electrophoresis and identified a further six glycosylation sites. This study more than doubles the number of confirmed N-linked glycosylation sites in C. jejuni and is the first to utilize HCD fragmentation for glycopeptide identification with intact glycan. We also show that hydrophobic integral membrane proteins are significant targets of glycosylation in this organism. Our data demonstrate that peptide-centric approaches coupled to novel mass spectrometric fragmentation techniques may be suitable for application to eukaryotic glycoproteins for simultaneous elucidation of glycan structures and peptide sequence.

Campylobacter jejuni is a Gram-negative, microaerophilic, spiral-shaped, motile bacterium that is the most common cause of food- and water-borne diarrheal illness worldwide (1). Typical infections are acquired via the consumption of undercooked poultry where C. jejuni is found commensally (2). Symptoms in humans range from mild, non-inflammatory diarrhea to severe abdominal cramps, vomiting, and inflammation (3). Prior infection with C. jejuni is a common antecedent of two chronic immune-mediated disorders: Guillain-Barré syndrome (4) and immunoproliferative small intestine disease (5). A unique molecular trait of C. jejuni is the ability to post-translationally modify proteins by the N-linked addition of a 7-residue glycan (GalNAc-α1,4-GalNAc-α1,4-(Glcβ1,3)- GalNAc-α1,4-GalNAc-α1,4-GalNAc-α1,3-Bac-β1 where Bac is bacillosamine (2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxyglucopyranose)) (6) at the consensus sequon (D/E)XNX(S/T) where X is any amino acid except proline (7).

The N-linked C. jejuni heptasaccharide is encoded by the pgl (protein glycosylation) gene cluster (8–10), and the glycan is transferred to proteins by the PglB oligosaccharyltransferase (11) at the periplasmic face of the inner membrane (12). Removal of the N-glycosylation gene cluster (or indeed pglB alone) results in C. jejuni that displays poor adherence to and invasion of epithelial cell lines (13) and reduced colonization of the chicken gastrointestinal tract (14). Although this demonstrates a requirement for glycosylation in virulence, the proteins that mediate this are still unknown, and the overall role of glycan attachment remains to be elucidated. Our current understanding of the structural context of glycosylation in C. jejuni suggests that it does not play a role in steric stabilization by conferring structural rigidity as seen in eukaryotes (15) but occurs preferably on flexible loops and unordered regions of proteins (16–18). To investigate the role of glycosylation in protein function, recent studies have utilized mutagenesis to remove the N-linked sequon from three glycoproteins: Cj1496c (19), Cj0143c (20), and VirB10 (21). Removal of glycosylation from Cj1496c and Cj0143c had little effect on protein function; however, glycan attachment was required for correct localization of VirB10. Although the exact role of the glycan remains largely unknown, it appears to be site-specific with a single site, Asn97, influencing localization of VirB10, whereas a second site, Asn32, is dispensable (21). It is clear that a more comprehensive analysis of the C. jejuni glycoproteome is required. A further complication in the elucidation of N-linked glycosylation is the use of the NCTC 11168 strain, which because of laboratory passage (22, 23) may not be the most appropriate model in which to study the virulence properties of glycan attachment. For example, we have recently shown that a surface-exposed virulence factor, JlpA, is glycosylated at two sites (Asn146 and Asn107) in all sequenced C. jejuni strains except NCTC 11168, which contains only Asn146 (24).

Glycoproteomics in C. jejuni is also a major technical challenge. Unlike eukaryotic N-linked glycans, the C. jejuni glycan is resistant to removal by protein N-glycosidase F (24) and chemical liberation via β-elimination (6) possibly because of the structure of the unique linking sugar, bacillosamine (25). Analysis therefore requires complementary methodology to elucidate the sites of glycosylation in the presence of the glycan. Preferential fragmentation of the glycan itself during collision-induced dissociation (CID) generally results in poor recovery of peptide fragment ions, and thus identification of the underlying protein and site of attachment remains problematic. MS3 has been attempted for site identification (6, 26); however, the data are limited by the requirement for sufficient ions for two rounds of tandem MS. We have also shown previously that C. jejuni encodes several hydrophobic integral membrane and outer membrane proteins possessing multiple transmembrane-spanning regions that are not amenable to gel-based approaches (27), particularly those using lectins for glycoprotein purification (28). We hypothesize that N-linked glycosylation is more widespread than previously demonstrated (6, 7, 26) because these studies examined only soluble proteins (6, 26) or used lectin affinity (6, 7), which limits the amount and type of detergents that can be used. Recent work (26) has demonstrated the potential of exploiting the hydrophilic nature of the C. jejuni glycan to enable glycopeptide enrichment.

The ability to generate product ions useful for the identification of a glycosylated peptide is governed by three factors: the peptide backbone, the glycan, and the fragmentation approach. Multiple strategies exist to separately exploit the first two of these parameters (29, 30), but it is only recently that selective fragmentation of modified peptides has been available through electron transfer dissociation (ETD)1 and electron capture dissociation (31, 32). ETD/electron capture dissociation enable the selective cleavage of the peptide while maintaining the carbohydrate structure, and this has been demonstrated using eukaryotic glycopeptides (33, 34) and more recently glycopeptides isolated from the pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae (35). A more recent fragmentation approach is higher energy collisional (C-trap) dissociation (HCD), which uses higher fragmentation energies than standard CID and enables identification of modifications, such as phosphotyrosine (36), via diagnostic immonium ions and high mass accuracy over the full mass range in MS/MS. HCD has not previously been applied to glycopeptides.

We applied several enrichment and MS fragmentation approaches to the characterization of the glycoproteome of C. jejuni HB93-13. Sequence analysis determined that the HB93-13 genome contains 510 N-linked sequons ((D/E)XNX(S/T)) in 382 proteins of which 261 (with 371 potential N-linked sites) are predicted to pass through the inner membrane and are therefore the subset that may be glycosylated. We examined trypsin digests of whole cell and membrane protein preparations using zwitterionic hydrophilic interaction chromatography (ZIC-HILIC) and graphite enrichment of gel-separated proteins using several mass spectrometric techniques (CID, HCD, and ETD). This is the first study to demonstrate the potential of using the high energy fragmentation of HCD to overcome the signal disruption caused by labile glycan fragmentation and to provide peptide sequencing within a single step. Manual data analysis was also simplified as the GalNAc fragment ion (204.086 Da) provides a signature that can be used to highlight glycopeptides within a complex mixture. We identified 81 glycosylation sites, including 47 not described previously in the literature and a single site that cannot be unambiguously assigned. The majority of these are present on proteins not amenable to traditional gel-based analyses, such as hydrophobic transmembrane proteins. Our work more than doubles the previously known N-linked C. jejuni glycoproteome and provides a clear rationale for other studies where the peptide and glycan need to remain associated.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Determination of Sequon Distribution in C. jejuni

The C. jejuni HB93-13 translated genome sequence (available through NCBI (NCBI entry NZ_AANQ00000000)) was subjected to in silico digestion with trypsin to identify the entire complement of theoretical peptides containing the N-linked sequon. Predicted sites were manually assessed to ensure that no sequons were missed where lysine or arginine are present as “X” in the motif (D/E)XNX(S/T). Peptides containing the sequon were extracted using the FASTA database “retrieve motif” function of the GPMAW 8.1 software package (Lighthouse Data, Odense, Denmark). Protein mass and grand average hydropathy (GRAVY) values were determined by ProtParamexpasy.org/tools/protparam.html. Predicted subcellular localization of the sequon-containing proteins was obtained using the program PSORTb v. 2.0 (37) and by cross-referencing predicted sequon-containing proteins with their UniProt entries (http://www.uniprot.org).

Bacterial Cultivation

C. jejuni HB93-13 (ATCC 700297) cells were cultured in parallel on Skirrow's agar plates (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) in a microaerophilic environment of 5% O2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2 at 37 °C for 48 h. Plates were flooded with 5 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and colonies were removed with a cell scraper. Cells were washed three times in PBS and collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g. Cells were lyophilized and stored at −80 °C.

Extraction of Whole Cell Lysates

10 mg of freeze-dried bacteria were suspended in 1 ml of 40 mm Tris, and 150 units of Benzonase (Sigma) were added. Proteins were released using six rounds of tip probe sonication (Branson Sonifier B250, Darbury, CT) for 30 s with 1 min on ice between rounds. Cellular debris were removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. Protein quantitation was performed using a QubitTM kit (Invitrogen), and samples were split into 1-mg aliquots, then vacuum-dried, and stored at −20 °C.

Preparation of Membrane Protein-enriched Fractions

Membrane protein-enriched fractions were prepared as described (38). Briefly, 30 mg of freeze-dried cells were resuspended in 1 ml of 40 mm Tris (pH 7.8) with 150 μl of Benzonase and tip probe-sonicated for 4 × 30 s with 1 min on ice between rounds. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected and stored on ice. Pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of 40 mm Tris, resonicated, and collected a further three times (4-ml final supernatant). Supernatants were mixed with 6 volumes of 0.1 m sodium carbonate and incubated with gentle stirring on ice for 1 h. Membrane fragments were collected at 35,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The resulting pellet was washed twice in 35 ml of 40 mm Tris, and protein was quantitated as described above. Samples were split into aliquots of ∼1 mg in low bind tubes and vacuum-dried.

Trypsin Digestion

Dried whole cell lysates and membrane protein-enriched fractions were resuspended in 6 m urea, 2 m thiourea, 40 mm NH4HCO3. The solutions were reduced for 1 h with 10 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) followed by alkylation using 40 mm iodoacetamide for 1 h in the dark. Alkylation was quenched using 10 mm DTT. A 1:1000 (w/w) dilution of endoproteinase Lys-C (Sigma) was added, and digestion was allowed to proceed for 4 h at 25 °C. Samples were diluted 1:4 with 40 mm NH4HCO3 and digested with a 1:100 (w/w) dilution of porcine sequencing grade trypsin (Promega, Madison WI) overnight at 25 °C. Samples were dialyzed against ultrapure water overnight using a Mini Dialysis kit with a molecular mass cutoff of 1000 Da (Amersham Biosciences). Peptides were collected by vacuum centrifugation.

Enrichment of Glycopeptides by ZIC-HILIC

ZIC-HILIC enrichment was performed according to Hägglund et al. (39) with minor modifications. Microcolumns composed of 10-μm ZIC-HILIC resin (Sequant, Umeå, Sweden) packed into Proxeon (Odense, Denmark) P10 C8 tips to a bed length of 0.5 cm were washed with ultrapure water. Samples were resuspended in 80% acetonitrile (ACN), 5% formic acid (FA), and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Samples were adjusted to a concentration of 0.4 μg/μl. 20 μg of peptide material were loaded onto the column and washed with 10 load volumes of 80% ACN, 5% FA. Peptides were eluted with 2 load volumes of ultrapure water and concentrated using vacuum centrifugation.

Reversed Phase LC-Tandem CID/HCD-MS

ZIC-HILIC enriched glycopeptide fractions were resuspended in 0.1% FA and further separated using a 20-cm, 100-μm-inner diameter, 360-μm-outer diameter ReproSil-Pur C18 AQ 3-μm (Dr. Maisch, Ammerbuch-Entringen, Germany) reversed phase capillary column using a trapless EASY-nLC system (Proxeon). The peptides were eluted using a gradient from 100% phase A (0.1% formic acid) to 40% phase B (0.1% formic acid, 80% ACN) over 148 min at 200 nl/min directly into an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA). The LTQ-Orbitrap XL was operated in a data-independent mode, automatically switching between MS, CID, and HCD. For each MS scan, the two most abundant precursor ions were selected for fragmentation first using CID (collision energy, 35) to provide glycan identification and then subsequently using HCD (collision energy, 45) to obtain peptide fragmentation information. Raw data were viewed in Xcalibur v2.0.7 (Thermo Scientific). Putative glycopeptides were highlighted by searching HCD data for the presence of the 204.086 m/z GalNAc ion and confirmed by fragment ions generated by CID from the 7-mer C. jejuni glycan. Glycopeptides were characterized based on the masses of the complete glycopeptide and the peptide (following glycan removal) with a tolerance of 10 ppm using the GPMAW 8.1 “find peptide in FASTA db” module and the HB93-13 translated genome. The glycopeptide sequences were then validated by manual assignment of peptide fragment ions and were only accepted if these were matched within 0.02 Da with all prominent ions assigned.

Reversed Phase LC-Tandem CID/ETD-MS

ZIC-HILIC glycopeptide fractions in 0.1% FA were also separated on a ProteColTM C18 column (300-μm inner diameter × 100-mm length; SGE Analytical Science, Ringwood, Australia) equilibrated in solvent A (0.1% FA in water) using a trapless UltiMate 3000 intelligent LC system (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). After loading for 8 min, a gradient from 0 to 50% solvent B (0.1% FA in ACN) at 5 μl/min was applied over 112 min followed by a column wash in 80% solvent B for 5 min into an HCT Ultra ion trap/ETD mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Columns were re-equilibrated in 100% solvent A for 9 min before injecting the next fraction. The HCT Ultra ETD system was operated in a data-independent mode, automatically switching between MS (600–3000 m/z scan window) and CID and ETD (150–3000 m/z scan window). For each MS2 scan, the selected ion was subjected to CID to induce glycan fragmentation and then subsequently switched to ETD for 200 ms with ∼500,000–600,000 fluoranthene ions. All ETD was conducted with the smart decomposition function in the Esquire Control Software (Bruker), and the data were viewed in DataAnalysis v4.0 (Bruker). Glycopeptides were highlighted by searching CID data for the presence of 407 or 366 m/z disaccharide ions (corresponding to HexNAc-HexNAc and HexNAc-Hex, respectively) and by confirming the presence of the complete 7-residue glycan by manual inspection. Identified glycopeptides were characterized based on the glycopeptide and peptide (following removal of glycan) mass with a mass tolerance of 1.5 Da using the GPMAW 8.1 bioinformatics tool (as above). Assigned glycopeptide sequences were confirmed by manual interpretation of the ETD spectra and accepted if >5 peptide fragment ions were matched (0.8-Da tolerance). Tryptic digests of whole cell lysates and membrane protein-enriched fractions were run in duplicate using both CID/HCD and CID/ETD.

Soybean Lectin Affinity Enrichment and 2-DE of C. jejuni Glycoproteins

Protein extracts were prepared by the glycine method as described previously (6, 24). Freeze-dried proteins were resuspended in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (0.05 m Tris-HCl, 0.15 m NaCl (pH 7.5)) and centrifuged to remove insoluble material. Extracted proteins were passed through lectin columns comprising 250 μl of soybean agglutinin (SBA)-agarose slurry (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in Poly-Prep chromatography columns (Bio-Rad) previously equilibrated with 40 bed volumes of TBS. The lectin column was washed with 60 volumes of TBS, and the SBA-bound proteins were eluted with 100 mm N-acetyl-d-galactosamine in TBS. The eluted proteins were dialyzed against ultrapure water (as described above). Bound and unbound samples were resuspended in 2-DE sample buffer (5 m urea, 2 m thiourea, 0.1% carrier ampholytes, 2% (w/v) CHAPS, 2% (w/v) sulfobetaine 3–10, 2 mm tributylphosphine (TBP); Bio-Rad), and 250 μg of protein were used to reswell precast 17-cm pH 4–7 immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strip gels (Bio-Rad). Isoelectric focusing was performed using an IEF cell (Bio-Rad) apparatus for a total of 80 kV-h. The proteins in the IPG strips were reduced, alkylated, and detergent-exchanged by immersion in equilibration buffer (6 m urea, 2% SDS, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mm tributylphosphine, 2.5% (v/v) acrylamide monomer, 375 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.8)) for 10 min prior to loading the IPG strips onto precast 12.5% T, 2.5% C polyacrylamide gels (20 cm2). Strips were then embedded in 0.5% agarose in cathode buffer (192 mm glycine, 25 mm Tris, 0.1% SDS). Second dimension gel electrophoresis was carried out at 4 °C. Gels were stained as described previously (38).

Protein Identification from Two-dimensional Gels by MALDI-MS

Protein spots were excised from the gel and processed as described (40). Briefly, spots were destained in a 60:40 solution of 40 mm NH4HCO3 (pH 7.8), 100% ACN for 1 h. Gel pieces were vacuum-dried for 1 h and rehydrated in 8 μl of 12 ng/μl trypsin at 4 °C for 1 h. Excess trypsin was removed, and gel pieces were resuspended in 25 μl of 40 mm NH4HCO3 and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Peptides were concentrated and desalted using C18 Perfect PureTM tips (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and eluted in matrix (α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Sigma) at 8 mg/ml in 70% (v/v) ACN, 1% (v/v) FA) directly onto a target plate. Peptide mass maps were generated by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) using a Voyager DE-STR mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA). Spectra were examined in Data Explorer v4.5 (Applied Biosystems), and mass calibration was performed using the trypsin autolysis peaks, m/z 2211.11 and m/z 842.51. Peak lists were generated by manual assignment. Data from peptide mass maps were used to identify proteins using searches of the NCBI, Swiss-Prot, and TrEMBL databases via the program Mascot v2.1 (www.matrixscience.com). Identification parameters were as described previously (38).

Glycopeptide Enrichment Using Graphite Microcolumns

Glycosylation sites from gel-separated proteins were elucidated as described (29). Tryptic peptides were further digested overnight using proteinase K (400 ng in ultrapure water; Sigma). Protein digests were then passed through Poros 20 R2 resin (Applied Biosystems) microcolumns, and the hydrophilic flow-through was applied to hand-held graphite microcolumns (activated carbon; Sigma) constructed as described previously (41). Bound glycopeptides were eluted from the graphite column using 30% (v/v) ACN, 0.2% (v/v) FA and vacuum-dried. Glycopeptides were resuspended in 0.1% FA and loaded into Econo12 static tips (New Objective, Woburn, MA) and analyzed on a Q-STAR XL mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems) using electrospray ionization (ESI; direction injection). Following MS scans, individual parent ions were manually selected for MS/MS, and the instrument switched into product ion mode. Collision energy was manually set between 60 and 100 depending on the m/z of the parent ion. Data were acquired for up to 10 min and summed. Spectra were examined in Analyst v1.1 (Applied Biosystems).

Database Interrogation of Identified Glycopeptides

To further validate glycopeptide assignments from CID/HCD/ETD-MS or from gel-separated proteins, Mascot v2.2 searches were conducted via the Australasian Proteomics Computational Facility (www.apcf.edu.au). Searches were carried out with the same parameters used for manual interpretation with no protease specificity, instrument selected as ESI-QUAD-TOF (as previous reports suggest quadrupole-like fragmentation within HCD spectra (36)), and the fixed modification carbamidomethyl (Cys) and variable modifications oxidation (Met) and deamidation (Asn). ETD data were searched with the addition of the Campylobacter glycan mass (elemental composition C56H91N7O34; Asn) and with the instrument setting set to ETD-Trap. The ion score cutoff was set to 19, and all data were searched against a decoy database. All resulting matches were found to correspond to those assigned by manual sequence assignment and with a zero false positive rate generated against the decoy database. Several manually assigned glycopeptides within our data set did not generate Mascot scores, particularly those with low mass (for example, peptides derived from trypsin/proteinase K digests) and those with unusual modifications (for example, cysteine oxidation or formylation). Manual assignments of all MS/MS spectra leading to glycopeptide identifications are supplied in the supplemental data. CID and HCD spectra were annotated according to Domon and Costello (42) for glycan fragmentation and Roepstorff and Fohlman (43) for peptide fragmentation. ETD data were annotated using the nomenclature outlined by Kjeldsen et al. (44). Monosaccharides were denoted according to the nomenclature outlined by the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (http://glycomics.scripps.edu/CFGnomenclature.pdf) with the addition of provisional nomenclature to denote bacillosamine.

RESULTS

In Silico Identification of N-Linked Sequons in C. jejuni HB93-13

To test our hypothesis that the extent of N-linked glycosylation is greater than currently understood, we analyzed the C. jejuni HB93-13 theoretical proteome to identify tryptic peptides containing the N-linked sequon ((D/E)XNX(S/T) where X is any amino acid except proline; Ref. 7). A total of 510 sequon-containing tryptic peptides from 382 proteins were identified (supplemental Table S1). These proteins could be divided into eight localization classes based on PSORTb v.2.0 prediction and corresponding UniProt entries (supplemental Fig. S1). As the N-linked glycosylation machinery of C. jejuni occurs at the periplasmic face of the inner membrane (12), only non-cytoplasmic proteins were considered “putative” glycoproteins. We removed those proteins that were predicted to localize to the cytoplasm and created a final theoretical glycoproteome of 261 proteins containing 371 N-linked sequons. We assessed these proteins to predict their solubilization properties for lectin and gel-based studies by examining protein mass and predicted hydrophobicity (GRAVY value; supplemental Table S1). Predicted masses ranged from 5 to 166 kDa, and GRAVY scores ranged from −1.241 to 1.194 (supplemental Fig. S2). The predictions show that 54 (20.7%) of the potential glycoproteins have positive GRAVY values, whereas a further 15 proteins have very high (>110 kDa (three proteins)) or low (<10 kDa (12 proteins)) mass and are therefore unlikely to be compatible with gel-based technologies (27).

Development of Enrichment and Fragmentation Strategies for C. jejuni Glycopeptides

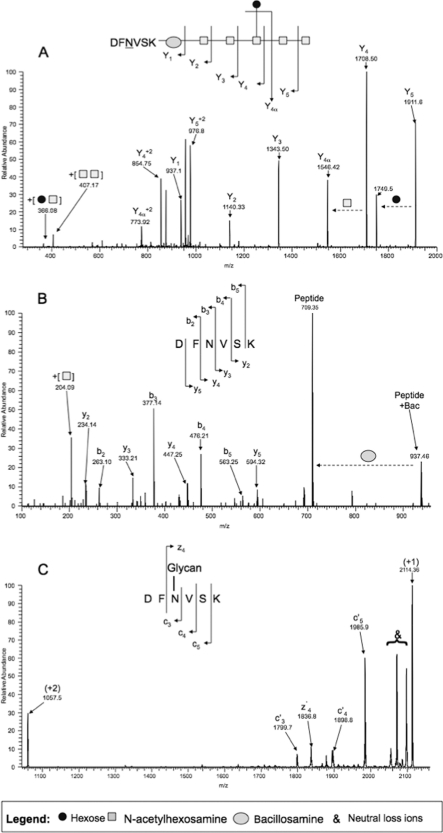

We utilized the previously identified C. jejuni glycoprotein PEB3 (6) (also known as the major antigenic protein Peb3) isolated from 2-DE gels (supplemental Fig. S3, spot 8B) as a standard for optimizing glycopeptide enrichment and MS fragmentation approaches. MALDI-MS of trypsinized PEB3 revealed multiple peptides corresponding to the predicted PEB3 sequence but a clear absence of the known glycopeptide ion of 2114.18 m/z (Fig. 1A). PEB3 digests were then passed through ZIC-HILIC microcolumns, and the bound peptides were analyzed by MALDI-MS (Fig. 1B). A prominent 2114.18 m/z ion could be identified with very little interference from other peptide ions. ESI-MS/MS of the ZIC-HILIC bound 1057.1 m/z ion (z = 2 form of the 2114.18 m/z ion) resulted in the generation of fragment ions corresponding to the C. jejuni 7-residue glycan but no fragmentation of the peptide backbone (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

ZIC-HILIC glycopeptide enrichment of C. jejuni glycoprotein PEB3 (NCBI database accession number YP_002343730) digested with trypsin. A, MALDI-MS of trypsin-digested PEB3; labeled peaks correspond to non-glycosylated PEB3 peptides. B, MALDI-MS of ZIC-HILIC enriched PEB3 tryptic peptides; the dominant 2114.1813 m/z peak corresponds to the known glycopeptide 88DFNVSK93 with addition of the C. jejuni glycan (1405.560 Da). Peaks labeled with * correspond to non-glycosylated tryptic peptides. Na+, sodium adduct of 2114.18-Da glycopeptide. The chemical structure of the C. jejuni heptasaccharide is shown in Weerapana and Imperiali (47).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of CID-, HCD-, and ETD-MS for fragmentation of C. jejuni PEB3 glycopeptide 2114.1813 m/z. A, CID-MS; the MS/MS spectrum is dominated by fragment ions generated from the glycan (depicted according to the nomenclature of Domon and Costello (42)). B, HCD-MS; eight of 10 peptide-related b and y ions were detected with a mass accuracy of 0.02 Da. The diagnostic 204.086 m/z GalNAc ion and complete peptide (709.35 m/z) attached to the linking bacterial sugar bacillosamine (937.46 m/z) were also detected. C, ETD-MS; exclusive c and z fragment ions (four peptide-related fragment ions could be assigned). ETD is dominated by charge-reduced species and multiple ions corresponding to neutral loss species (denoted with &).

To confidently identify C. jejuni glycopeptides, the fragmentation of both peptide and glycan is essential because enzymes, such as protein N-glycosidase F, and chemical β-elimination do not remove the attached glycan. We therefore optimized two methods to obtain peptide backbone fragmentation in the presence of the glycan using HCD- and ETD-MS (Fig. 2, B and C, respectively). Both methods enabled the identification of peptide fragment ions and were highly complementary. ETD of the 2114.18-Da glycopeptide (Fig. 2C) retained the glycan attachment, thus enabling confirmation of the glycosylation site, but resulted in spectra dominated by charge-reduced species and neutral loss ions within 60 Da of the parent ion (for a list of common neutral loss ions, see Ref. 45) when both the 2+ (1057.5 m/z) and 3+ (data not shown; induced by the addition of m-nitrobenzyl alcohol (46)) ions were fragmented. HCD of the same glycopeptide (Fig. 2B) did not retain the glycan on the peptide but enabled high resolution detection of product ions corresponding to the peptide backbone and the diagnostic GalNAc oxonium ion, 204.086 m/z. Because each technique provided additional, complementary information regarding the PEB3 standard glycopeptide, we decided to use both types of fragmentation in LC-MS/MS strategies on complex peptide mixtures derived from C. jejuni membrane protein-enriched fractions and whole cell lysates. As charge reduction was the dominant fragmentation effect within the ETD spectrum, we also decided to utilize an extended ion trap ETD to enable identification of ions with m/z >2000.

Application of ZIC-HILIC Enrichment and CID/HCD- and CID/ETD-MS to Complex C. jejuni Glycopeptide Mixtures

We examined C. jejuni glycopeptides from two different sample preparation techniques: (i) whole cell lysates (WCL) and (ii) membrane protein-enriched fractions (consisting of inner and outer membrane, periplasmic, and integral membrane proteins as reported previously (38)) Glycopeptides from complex tryptic peptide mixtures were enriched using ZIC-HILIC and identified by LC-MS/MS with CID (to confirm the presence of the glycan) followed by either HCD or ETD. A total of 130 glycopeptides (representing 75 glycosylation sites) were identified from duplicate data sets of each of the four techniques (Table I and supplemental Table S2).

Table I. Identification of glycopeptides in C. jejuni HB93-13.

The N-linked attachment site is underlined. MT score, Mascot score; MV, manually validated and searched against the HB93-13 translated genome (generally, MS/MS spectra needed manual validation where a non-specific cleavage had occurred at the C terminus of the peptide, particularly those glycopeptides generated by trypsin/proteinase K digestion following 2-DE). X indicates that the peptide was confidently identified by the designated experimental approach. Precursor mass (in Da) includes the presence of the 7-mer glycan with mass of 1405.7293 Da. Numbers in parentheses (“Sequence” column) represent mass modifications of the immediately preceding amino acid. Total row, number of identified peptides (the number of glycosylation sites is shown in parentheses, and the number of glycosylation sites found only by that sample preparation technique and mass spectral approach is shown in square brackets). Memb, membrane protein-enriched fraction. MS/MS data for each of the identified glycopeptides are contained in the supplemental data. Mox, oxidized Met; ABC, ATP-binding cassette.

| CJ no. | Gene name | Protein name | Precursor mass (charge) | Sequence | MT score | Memb (HCD) | WCL (HCD) | Memb (ETD) | WCL (ETD) | 2-DE/graphite (CID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cj0011c | Cj0011c | Putative non-specific DNA-binding protein | 1329.5885 (2+) | 49EANFTSIDDLK59 | 77 | X | ||||

| 1393.6375 (2+) | 49EANFTSIDDLKK60 | 89a | X | X | ||||||

| 1229.5472 (2+) | 51NFTSIDDLK60 | 40 | X | |||||||

| Cj0017c | dsbI | Disulfide bond formation protein | 1068.9869 (2+) | 3E(−1)INKTK8 | MV | X | ||||

| Cj0081 | cydA | Cytochrome bd oxidase subunit I | 918.0594 (3+) | 351ESNDTIAMoxANHK362 | 28 | X | X | |||

| 1368.5880 (2+) | 351ESNDTIAMANHK362 | 70 | X | X | X | |||||

| 763.1000 (4+) | 348LAKESNDTIAMANHK362 | 26 | X | |||||||

| Cj0089 | Cj0089 | Putative lipoprotein | 1130.4585 (2+) | 70NCGDFNK76 | 43 | X | X | X | ||

| 1146.4434 (2+) | 70NC(+32)GDFNK76 | MV | X | X | ||||||

| Cj0114 | Cj0114 | Putative periplasmic protein | 1295.2516 (3+) | 88LSQVEENNQNIENNFTSEIQK108 | 39 | X | ||||

| 1325.6099 (2+) | 149NELNDVNLSVK159 | 64 | X | |||||||

| 1147.5250 (2+) | 152NDVNLSVK159 | 57 | X | |||||||

| 1055.5700 (2+) | 176IENNNT181 | MV | X | |||||||

| 964.8700 (2+) | 99ENNF102 | MV | X | |||||||

| 894.4600 (2+) | 101NFT103 | MV | X | |||||||

| 964.9800 (2+) | 171DSNST175 | MV | X | |||||||

| 1015.5300 (2+) | 170TDSNST175 | MV | X | |||||||

| Cj0143c | Cj0143c | Putative periplasmic solute-binding protein | 1385.9929 (3+) | 22NLEQEQNTSSNLVSVSIAPQAFFVK46 | 44 | X | ||||

| Cj0152c | Cj0152c | Putative membrane protein | 872.0646 (3+) | 248EKDFNISLDK257 | 40 | X | X | |||

| 1440.0188 (3+) | 121TFFKDEQNNTSATVIDIIGQAQENLK146 | 68 | X | |||||||

| 1179.0249 (2+) | 250DFNISLDK257 | 50 | X | |||||||

| 1326.9381 (3+) | 161AQETNQTESVLPSQNISLQENDK183 | 49 | X | |||||||

| 1424.6668 (2+) | 147SLGGNNVVVIDNNK160 | 74 | X | |||||||

| Cj0168c | Cj0168c | Putative periplasmic protein | 1409.6226 (2+) | 21ANTPSDVNQTHTK33 | 63 | X | X | |||

| 1431.1250 (2+) | 21ANTPSDVNQTH(+43)TK33 | MV | X | |||||||

| 1253.0372 (2+) | 23TPSDVNQTHT32 | 54 | X | |||||||

| 1345.5759 (2+) | 21ANTPSDVNQTHT32 | 77 | X | X | ||||||

| 878.3920 (3+) | 23TPSDVNQTHTK33 | 43 | X | |||||||

| Cj0200c | Cj0200c | Putative periplasmic protein | 1029.9275 (2+) | 32YDNNK36 | 40 | X | ||||

| 1186.0178 (2+) | 29AQIYDNNK36 | 55 | X | |||||||

| 1242.6513 (2+) | 28IAQIYDNNK36 | 81 | X | X | ||||||

| 1150.5011 (2+) | 30QIYDNNK36 | 40 | X | |||||||

| 1243.0544 (2+) | 28IAQIYDN(+1)NK36 | 58 | X | |||||||

| Cj0235c | secG | Putative protein export protein | 1552.2238 (2+) | 107SIAPSAPQLPSDVNSSK123 | 96 | X | ||||

| Cj0238 | Cj0238 | Putative mechanosensitive ion channel family protein | 1187.2269 (3+) | 21FIDANISKEDEGIYALVEK40 | 68 | X | ||||

| 1193.5294 (3+) | 53KNNDENSSTFNGILSEFEK71 | 26 | X | |||||||

| Cj0256 | Cj0256 | Putative sulfatase family protein | 764.1000 (4+) | 205TIANDAYRENNHTK219 | 26 | X | ||||

| Cj0277 | mreC | Rod shape-determining protein | 1227.0515 (2+) | 88ILEDQNSTK96 | 67 | X | X | X | ||

| 1170.5079 (2+) | 89LEDQNSTK96 | 30 | X | |||||||

| Cj0289c | peb3 | Major antigenic protein PEB3 | 1057.9614 (2+) | 88DFNVSK93 | 52 | X | X | |||

| 1436.6679 (3+) | 66DADILFGASDQSALAIASDFGKDFNVSK93 | 30 | X | |||||||

| 1071.9578 (2+) | 88DFNVSK(+28)93 | MV | X | |||||||

| 993.8900 (2+) | 88DFNVS92 | MV | X | |||||||

| Cj0313 | Cj0313 | Putative integral membrane protein | 1188.5621 (2+) | 196DGNITLLPK204 | 19 | X | ||||

| Cj0365c | cmeC | Outer membrane multidrug efflux system protein CmeC | 1149.5037 (2+) | 47ENNSSITK54 | 36 | X | X | X | X | |

| 1061.4976 (3+) | 39LGALSWEKENNSSITK54 | 61 | X | X | ||||||

| Cj0366c | cmeB | Inner membrane multidrug efflux system protein CmeB | 1031.1547 (3+) | 634DRNVSADQIIAELNK648 | 48 | X | X | X | ||

| 1073.8524 (3+) | ||||||||||

| 962.8652 (5+) | 634DRNVSADQIIAELNKK649 | 59 | X | X | X | |||||

| 620ENAAAMoxFIGLQDWKDRNVSADQIIAELNKK649 | MV | X | ||||||||

| Cj0367c | cmeA | Periplasmic multidrug efflux system protein CmeA | 978.9151 (2+) | 121DFNR124 | MV | X | X | |||

| 935.7463 (3+) | 113ATFENASKDFNR124 | 44 | X | X | ||||||

| 1392.3308 (3+) | 268AIFDNNNSTLLPGAFATITSEGFIQK293 | 29 | X | |||||||

| Cj0371 | Cj0371 | UPF0323 lipoprotein Cj0371 | 1105.4789 (2+) | 75DLNGTER81 | 19 | X | X | X | X | |

| 1325.1357 (2+) | 71VVLKDLNGTER81 | 39 | X | X | ||||||

| Cj0397c | Cj0397c | Putative uncharacterized protein | 1641.7391 (2+) | 101ENINDFNNTALQNELK116 | 44 | X | X | X | X | |

| Cj0399 | Cj0399 | Colicin V production protein | 1447.1699 (2+) | 173LQDIVSDLNNTQK185 | 49 | X | X | X | ||

| 1540.2033 (2+) | 173LQDIVSDLNNTQKGE187 | 69 | X | X | X | |||||

| Cj0454c | Cj0454c | Putative membrane protein | 666.4000 (3+) | 90SENNK94 | MV | X | ||||

| Cj0494 | Cj0494 | Putative exporting protein | 1119.8798 (2+) | 25EDNNITK31 | 19 | X | ||||

| Cj0511 | Cj0511 | Putative secreted protease | 1282.9293 (3+) | 56TLAIVEQYYVDDQNISDLVDK76 | 20 | X | ||||

| 991.4800 (2+) | 67DQNIS71 | MV | X | |||||||

| Cj0515 | Cj0515 | Putative periplasmic protein | 1252.5579 (2+) | 102FDFNISVEK110 | 39 | X | ||||

| 1060.1492 (3+) | 96TTENTKFDFNISVEK110 | 23 | X | |||||||

| 1384.6657 (3+) | 226QGIENLKGDFNASSAFYYAILPLSK250 | 23 | X | |||||||

| Cj0530 | Cj0530 | Putative periplasmic protein | 1700.7441 (2+) | 514TLNFEDFNASVNDAYFK530 | 26 | X | ||||

| Cj0587 | Cj0587 | Putative integral membrane protein | 1225.5690 (2+) | 282DNNLSLIQK290 | 35 | X | ||||

| Cj0599 | Cj0599 | Putative OmpA family membrane protein | 1336.1043 (2+) | 94AELEANITNYK104 | 34 | X | ||||

| 1290.5834 (2+) | 167LDNNITIDEK176 | 68 | X | |||||||

| 1213.0360 (2+) | 109DLNSTLDNK117 | 79 | X | |||||||

| 1334.5977 (2+) | 109DLNSTLDNKDK119 | 44 | X | X | ||||||

| Cj0608 | Cj0608 | Putative outer membrane efflux protein | 1382.6036 (2+) | 35DLNLTYDWYR44 | 34 | X | ||||

| Cj0610c | Cj0610c | Putative periplasmic protein | 889.7469 (3+) | 80SIDENLSKIDK90 | 39 | X | X | X | ||

| 1156.0142 (2+) | 80SIDENLSK87 | 45 | X | X | ||||||

| 1162.5294 (2+) | 329LKEENASK336 | 37 | X | X | ||||||

| Cj0648 | Cj0648 | Putative membrane protein | 1266.0752 (2+) | 47AYESNTSIIK56 | 39 | X | ||||

| Cj0652 | pbpC | Penicillin-binding protein | 1262.5768 (2+) | 95NLFPDLNASK104 | 57 | X | ||||

| 1176.5179 (3+) | 465SIENNNTTIENQMDENKK482 | 68 | X | X | ||||||

| Cj0694 | Cj0694 | Putative periplasmic protein | 1766.2998 (2+) | 306DQNISESDVYYPIDLLNK323 | 61 | X | X | |||

| 1092.4721 (2+) | 129PTGDFNK135 | 43 | X | |||||||

| 1352.0686 (2+) | 125EFQDPTGDFNK135 | 77 | X | X | ||||||

| 1388.6364 (3+) | 301DNFQKDQNISESDVYYPIDLLNK323 | 48 | X | |||||||

| 1484.3569 (3+) | 125EFQDPTGDFNKTIYYELLNANNLTPK150 | 47 | X | |||||||

| 1116.5178 (4+) | 298NGKDNFQKDQNISESDVYYPIDLLNK323 | 37 | X | |||||||

| 993.4000 (2+) | 131GDFNK135 | MV | X | |||||||

| 991.4200 (2+) | 306DQNIS310 | MV | X | |||||||

| Cj0734c | hisJ | Histidine-binding protein HisJ/CjaC | 875.4028 (3+) | 25NKESNASVELK35 | 40 | X | X | X | ||

| 1191.5326 (2+) | 27ESNASVELK35 | 45 | X | X | X | |||||

| Cj0783 | napB | Periplasmic nitrate reductase small subunit | 1691.2910 (2+) | 44VNLVEANFTTLQPGESTR61 | 95 | X | ||||

| 1378.6194 (2+) | 50NFTTLQPGESTR61 | 52 | X | |||||||

| Cj0843c | Cj0843c | Putative secreted transglycosylase | 976.7976 (3+) | 169KYDLDLNTSLVNK181 | 50 | X | ||||

| 972.9079 (2+) | 374DYNK377 | MV | X | |||||||

| 969.9200 (2+) | 97DANLT101 | MV | X | |||||||

| 833.8800 (2+) | NK | MV | X | |||||||

| 941.9600 (2+) | 327DANAS331 | MV | X | |||||||

| Cj0846 | Cj0846 | Uncharacterized metallophosphoesterase | 808.3913 (3+) | 277IKVDLNTSK285 | 58 | X | ||||

| Cj0982c | cjaA | Putative amino acid transporter periplasmic solute-binding protein CjaA | 957.1007 (2+) | 137DSNITSVEDLKDK149 | 44 | X | X | X | ||

| 1313.5840 (2+) | 137DSNITSVEDLK147 | 65 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 1456.6504 (2+) | 137D(+43)SNITSVEDLK147 | MV | X | |||||||

| 1154.2383 (3+) | 128VALGVAVPKDSNITSVEDLK147 | 39 | X | |||||||

| 1235.2794 (3+) | 128VALGVAVPKDSNITSVEDLKDK149 | 49 | X | |||||||

| 1184.5814 (3+) | 137DSNITSVEDLKDKTLLLNK155 | 73 | X | X | ||||||

| 878.0588 (5+) | 128VALGVAVPKDSNITSVEDLKDKTLLLNK155 | 33 | X | |||||||

| Cj0983 | jlpA | Putative lipoprotein JlpA | 1533.7144 (2+) | 141VVSDINASLFQQDPK155 | 66 | X | ||||

| 1213.0540 (2+) | 104GEANTSISIK113 | 40 | X | |||||||

| Cj1007c | Cj1007c | Putative mechanosensitive ion channel family protein | 954.9128 (2+) | 17DVNR20 | MV | X | ||||

| Cj1013c | Cj1013c | Putative cytochrome c biogenesis protein | 1610.7531 (2+) | 178ENNNSDPLLVLMLSQK193 | 71 | X | ||||

| 1077.4534 (2+) | 731DGNWTR736 | 32 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 1490.0282 (3+) | 229IDENLTLSSSENLHFLSMoxLDGQNLDLK255 | 20 | X | |||||||

| 1484.6973 (3+) | 229IDENLTLSSSENLHFLSMLDGQNLDLK255 | 35 | X | |||||||

| 1052.8304 (3+) | 529QDLNSTLPVVNTNHAK544 | 78 | X | |||||||

| 1570.2273 (2+) | 529Q(−17)DLNSTLPVVNTNHAK544 | MV | X | |||||||

| Cj1032 | cmeE | Membrane fusion component multidrug efflux system CmeE | 1212.0459 (2+) | 198IDQNGTELK206 | 81 | X | X | X | X | |

| 870.0715 (3+) | 198IDQNGTELKGK208 | 40 | X | |||||||

| 1136.8521 (3+) | 190LGDDFFYKIDQNGTELK206 | 52 | X | X | ||||||

| 1026.8700 (2+) | 198IDQNGT203 | MV | X | |||||||

| Cj1053c | Cj1053c | Putative integral membrane protein | 1040.9696 (2+) | 75DINVSK80 | 33 | X | ||||

| Cj1055c | Cj1055c | Putative sulfatase protein | 1371.5885 (2+) | 612GYYFESNDTLK622 | 76 | X | ||||

| Cj1126c | pglB | PglB oligosaccharyltransferase | 1263.2407 (3+) | 532DYNQSNVDLFLASLSKPDFK550 | 67 | X | X | |||

| Cj1345c | Cj1345c | Putative periplasmic protein | 1079.9741 (2+) | 59DYNITK64 | 45 | X | X | |||

| 1108.4829 (2+) | 59DYNITKG65 | 34 | X | |||||||

| 1033.9613 (2+) | 155EINASK160 | 33 | X | |||||||

| 1077.4760 (2+) | 154SEINASK160 | 29 | X | X | ||||||

| 1499.6764 (2+) | 154SEINASKYPDLENI167 | 73 | X | |||||||

| 1185.5154 (2+) | 152DTSEINASK160 | 55 | X | |||||||

| 969.9300 (2+) | 155EINAS159 | MV | X | |||||||

| 1020.4300 (2+) | 347VDGNET352 | MV | X | |||||||

| Cj1373 | Cj1373 | Putative integral membrane protein | 1409.6415 (2+) | 128PNIESQDINRTK(−2)139 | MV | X | ||||

| Cj1444c | kpsD | Capsule polysaccharide export system periplasmic protein KpsD | 1062.4711 (2+) | 50ENNLTK55 | 32 | X | X | X | X | |

| 1062.9628 (2+) | 50EN(+1)NLTK55 | 45 | X | |||||||

| 1119.0129 (2+) | 50ENNLTKI56 | 24 | X | |||||||

| Cj1496c | Cj1496c | Putative periplasmic protein | 1226.0612 (2+) | 69EAEVNATLAK78 | 31 | X | X | |||

| 1133.9692 (2+) | 165NLDNNASN172 | MV | X | |||||||

| 983.95 (2+) | 69EAEVN73 | MV | X | |||||||

| 1019.5700 (2+) | 69EAEVNA74 | MV | X | |||||||

| Cj1565c | pflA | Paralyzed flagellum protein | 1215.2135 (3+) | 446ASDEVFFALGDNNASFLHQR465 | 39 | X | X | |||

| 1309.5977 (2+) | 495EGNFSAILAYK505 | 52 | X | |||||||

| Cj1621 | Cj1621 | Putative periplasmic protein | 1180.0341 (2+) | 193TYSLDLNK200 | 45 | X | ||||

| Cj1661 | Cj1661 | Possible ABC transport system permease | 1111.0022 (2+) | 185LIGENNR191 | MV | X | ||||

| Cj1670c | cgpA | Putative periplasmic protein | 1111.0151 (2+) | 68INLDVNK74 | 57 | X | X | |||

| 1054.4736 (2+) | 69NLDVNK74 | 52 | X | |||||||

| 1197.9047 (3+) | 25TDQNITLVAPPEFQKEEVK43 | 36 | X | X | ||||||

| 940.9097 (2+) | 71DVNK74 | MV | X | X | ||||||

| 1306.6148 (3+) | 53SITFNYINLDGSEDKINLDVNK74 | 60 | X | |||||||

| 1322.6129 (3+) | 19DENPFKTDQNITLVAPPEFQKE40 | 21 | X | |||||||

| 1398.6488 (3+) | 19DENPFKTDQNITLVAPPEFQKEEV42 | 44 | X | |||||||

| 1279.5972 (3+) | 19DENPFKTDQNITLVAPPEFQK39 | 55 | X | |||||||

| 1048.9500 (2+) | 25TDQNIT30 | MV | X | |||||||

| 883.4900 (2+) | 72VNK74 | MV | X | |||||||

| 997.4000 (2+) | 70LDVNK74 | MV | X | |||||||

| 1254.6200 (2+) | 100VTIPEKNSSK109 | MV | X | |||||||

| 920.9900 (2+) | 106NSSK109 | MV | X | |||||||

| Not assigned | 947.9185 (2+) | DLNK | MV | X | ||||||

| Total | 53 proteins | 154 unique peptides (81 glycosylation sites) | 53 (35) [8] | 100 (65) [28] | 27 (19) [2] | 19 (16) [0] | 24 (17) [6] |

a Where multiple techniques identified the same protein, the Mascot score is shown from the HCD analysis.

26 of 75 sites were identified using both HCD and ETD (Fig. 3) (for example, 70NCGDFNK76 (the site of glycosylation is underlined) of the putative lipoprotein Cj0089c (Fig. 4, A and B)). CID/HCD identified 49 unique sites, whereas CID/ETD identified two novel sites not seen in HCD (Fig. 3). Comparisons of the data generated from WCL and membrane protein-enriched fractions showed that the combination of WCL and CID/HCD generated the highest number of confident matches (Table 1; 100 glycopeptides representing 65 glycosylation sites (28 of which were not identified in the other data sets; for example, 282DNNLSLIQK290 from probable integral membrane protein Cj0587 (Fig. 4C)). A further eight unique glycosylation sites were generated through the use of membrane protein-enriched fractions and analyzed by CID/HCD from a total of 53 glycopeptides (35 glycosylation sites). The WCL and membrane protein-enriched fractions both generated significantly fewer confident matches when analyzed by CID/ETD (19 glycopeptides (16 glycosylation sites) from WCL and 27 glycopeptides (19 glycosylation sites) from membrane protein-enriched fractions); however, two novel sites (from Cj0256 (Fig. 4D) and Cj0454c) were identified from the membrane fractions.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of CID/HCD and CID/ETD glycopeptide identifications from C. jejuni HB93-13. A total of 75 sites were identified.

Fig. 4.

Novel C. jejuni glycosylation sites identified using HCD- and ETD-based approaches. HCD-MS (A) and ETD-MS (B) of the glycopeptide 70NCGDFNK76 from putative lipoprotein Cj0089c are shown. C, HCD-MS of the glycopeptide 282DNNLSLIQK290 from probable integral membrane protein Cj0587. D, ETD-MS of the glycopeptide 205TIANDAYRENNHTK218 from putative sulfatase Cj0256. See supplemental Table S2 and supplementary data for all annotated spectra. ETD is dominated by charge-reduced species and multiple ions corresponding to neutral loss species (denoted with &). Intens, intensity.

We were somewhat surprised at the relative distribution of identified glycopeptides when compared between the WCL and membrane fractions (Fig. 5). Substantially more identifications were achieved using WCL compared with membrane preparations (65 versus 38); however, an additional 10 glycosylation sites (eight from CID/HCD and two from CID/ETD, representing nine glycoproteins) were unique to the membrane fractions. Seven of these nine glycoproteins were predicted to be integral membrane proteins, and analysis of their GRAVY values indicated that four were positive, suggesting some enrichment of these poorly soluble proteins.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of glycopeptide identifications from whole cell lysates and membrane protein-enriched fractions.

Analysis of Soluble Glycoproteins by 2-DE and Graphite Glycopeptide Enrichment

We were previously able to identify novel glycosylation sites in the JlpA lipoprotein using SBA enrichment, which binds the N-acetylgalactosamine residues within the C. jejuni glycan (6), and 2-DE with trypsin/proteinase K digestion coupled to graphite glycopeptide purification (24). We therefore used this approach to determine whether additional novel glycosylation sites could be identified on a proteome-wide scale in the HB93-13 strain and thus complement our gel-free data sets. Glycoproteins enriched by SBA affinity were separated using 2-DE (supplemental Figs. S3 and S4), digested with trypsin, and identified by MALDI-MS (supplemental Table S3). Identified proteins were further digested with proteinase K, which results in very small glycopeptides of 3–5 amino acid residues because the large attached glycan sterically hinders the protease, whereas non-glycosylated peptides are digested to near completion. The resulting glycopeptides were then enriched using graphite microcolumns and subjected to direct injection ESI (CID)-MS/MS. We identified 16 glycosylation sites (from nine glycoproteins) by this approach of which six corresponded to novel sites not identified using CID/HCD or CID/ETD (for example, 97DANLT101 from Cj0843c (Fig. 6 and Table I)).

Fig. 6.

CID-MS of SBA-bound, 2-DE-separated, trypsin/proteinase K-digested, and graphite-purified glycopeptide (97DANLT101) from secreted transglycosylase (Cj0843c). See supplemental Table S2 and supplemental data for all annotated spectra.

Summary of Identified C. jejuni HB93-13 Glycosylation Sites

Prior to this study, a total of 44 glycosylation sites had been confirmed in C. jejuni (6, 7, 11, 12, 19–21, 24, 26). Our in silico predictions confirmed that 41 of these sites were possible in the C. jejuni HB93-13 genome (conserved sequons). Comparisons between the glycosylation sites identified in our study and those of previously identified glycoproteins revealed that 80.5% (33 of the 41 known) glycosylation sites and 96.6% (28 of the previously known 29) of the glycoproteins were identified within this study (supplemental Table S4). We therefore identified 47 novel glycosylation sites in 25 previously unknown glycoproteins. GRAVY value and mass calculation showed that our gel-free/lectin-free strategy of combining ZIC-HILIC glycopeptide enrichment with CID/HCD and CID/ETD fragmentation allowed the identification of novel hydrophobic glycoproteins (17 with a GRAVY score >0; supplemental Table S1). A total of 91 glycosylation sites have now been confirmed in C. jejuni with 89 of these localized to chromosomally encoded proteins (two sites on plasmid-borne VirB10).

Assessment of Glycoprotein Localization, Function, and Strain Diversity

Protein database entries (UniProt) and prediction software (PSORT; http://www.psort.org/) were used to cluster the identified glycoproteins based on their cellular localization (Fig. 7). The majority of proteins were predicted to localize to the cytoplasmic (inner) membrane (38%) or periplasm (28%), although outer membrane proteins (17%) and lipoproteins (7%) were also identified. No cytoplasmic proteins were identified. Proteins were also grouped according to predicted function using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/kegg2.html; Fig. 8). The largest group within the identified glycoproteome were those with no known function (34.0%); other significant groups included membrane transporters (20.8%) and small molecule-binding proteins (9.4%).

Fig. 7.

Predicted subcellular localization of glycoproteins from C. jejuni HB93-13 identified in this study.

Fig. 8.

Functional classification of identified C. jejuni glycoproteins. 34% of identified proteins have no known function with the largest group of predicted functions belonging to membrane transport (21%; 11 proteins).

Our previous data on the JlpA surface glycolipoprotein (24) indicated that glycosylation sites may vary between strains. We therefore examined the predicted proteomes of multiple sequenced C. jejuni strains to determine the degree of sequon conservation for the 89 chromosomally encoded glycosylation sites identified thus far in C. jejuni. Genome-derived protein sequences from 10 C. jejuni strains and the subspecies C. jejuni doylei were examined. From 926 protein sequences, we identified 903 conserved N-linked glycosylation sequons (97.52%), indicating a very high degree of conservation among glycosylation sites across strains of C. jejuni (supplemental Table S4).

DISCUSSION

The discovery of an N-linked glycosylation pathway in C. jejuni has led to a detailed understanding of the enzymes required for the generation and attachment of the Campylobacter N-glycan to protein substrates (47, 48). The primary goal of this study therefore was to further our knowledge of the substrates of glycosylation in this organism through the development of peptide-centric approaches to enrich and identify C. jejuni glycopeptides in a high throughput manner. Generation of such data, however, is not trivial. The N-linked glycan is resistant to protein N-glycosidase F treatment and β-elimination and is unique in composition, thus nullifying most approaches designed for eukaryotic N-linked glycoproteins. CID-MS/MS of these glycopeptides results in product ions generated predominantly from the fragmentation of the glycan without concurrent generation of peptide backbone information. We therefore investigated the C. jejuni glycoproteome using a gel-free strategy combining the enrichment of glycopeptides by ZIC-HILIC chromatography with novel fragmentation strategies of CID/HCD-MS/MS and CID/ETD-MS/MS. To our knowledge this is the first study to use CID/HCD fragmentation for simultaneous identification of glycan structure and peptide sequence.

The hydrophilicity of the C. jejuni glycan was exploited by ZIC-HILIC enrichment (49) optimized using the glycoprotein PEB3 (Fig. 1), and 75 individual glycosylation sites (130 unique glycopeptides) were identified by CID/HCD and CID/ETD. The identified glycopeptides ranged in mass from 474.25 to 3404.73 Da (glycan mass not included; average mass, 1469.7Da). The observed mass distribution was significantly lower than the average for the predicted, non-cytoplasmic glycopeptidome (average, 2050.7Da; 371 sequon-containing peptides; supplemental Table S1). This suggests that ZIC-HILIC enrichment coupled with LC-MS may be biased against higher mass glycopeptides. A further six glycosylation sites were elucidated by lectin affinity coupled to 2-DE and trypsin/proteinase K digestion with graphite purification. Further examination showed that these correspond to sites located within large tryptic peptides (>∼2500 Da) that were not detected by the gel-free approach. As an example, two graphite-purified, trypsin/proteinase K-derived glycopeptides were identified from Cj0114 within a single tryptic peptide, 158TITPSVVVSTTDSNSTIENNNTQNTQDDK188. MS3 or CID/HCD of trypsin-derived Cj0114 would be incapable of unambiguously assigning the site of glycosylation for variants where only one site is occupied. This bias against larger mass tryptic peptides may also explain the absence of nine previously identified, chromosomally encoded glycopeptides in our ZIC-HILIC data sets (see below).

CID/HCD yielded 100 and 53 positively identified glycopeptides post-ZIC-HILIC enrichment from C. jejuni whole cell lysates and membrane protein-enriched fractions, respectively. HCD offers an advantage in providing a glycopeptide-specific ion signature (204.086 m/z from GalNAc) to facilitate glycopeptide identification within a complex peptide mixture. Because the C. jejuni glycan contains five GalNAc residues, there is also amplification of this single sugar oxonium ion, allowing rapid screening. This ion is not typically visible in ion trap CID scans because of the loss of the lower ∼28% of the m/z trap range relative to the precursor. Less intense sugar-specific fragment ions of 366 m/z (GalNAc-Glc) and 407 m/z (GalNAc-GalNAc) may be detected but have lower signal amplification than the 204.086 m/z ion detected in HCD.

Although a direct comparison between the total number of glycopeptides identified by HCD and ETD is not possible because identical samples could not be split from a single LC run, instrument differences do in part provide a rationale for the numbers generated. CID/ETD has a time delay needed for capturing ions for CID and then switching to capture ions for ETD (50) unlike CID/HCD where ions are split between the ion and orbital traps, allowing effectively concurrent ion detection. This delay in CID/ETD lowers the duty cycle and may help to explain the lower number of glycopeptides identified within this data set. These lower numbers were likely also due to the use of ETD in the extended ion mode, which was needed to improve identification of higher mass (>2000 m/z) ions. Furthermore, because of the lower resolution of the ion trap, the 366 and 407 m/z ions are less specific than the 204.086 m/z ion seen in HCD. We suggest that for glycopeptides with a complex glycan composed of multiple monomers of the same composition the use of HCD is a viable approach to not only simplify analysis but also enable glycopeptide identification in a fashion similar to immonium ion scanning of other post-translational modifications, such as acetylated lysine (51) and phosphotyrosine (36).

HCD fragmentation produced peptide sequence-associated fragment ions from charge 2+ precursors, whereas ETD showed a clear preference for higher charge state precursors. These data are in agreement with previous work showing that collision-induced fragmentation occurs according to the mobile proton model linked to peptide charge state and amino acid composition (52). HCD fragmentation results in the loss of glycan structure from the parent ion (except for the sugar monomers), enabling detection of the less intense peptide fragment ions. The assignment of the glycosylation site itself is therefore dependent on the presence of the sequon (7), which is more specific in C. jejuni than in eukaryotes with an Asp/Glu required at the −2 position. The fragmentation of ions by ETD is largely governed by the precursor mass to charge ratio, leading to enhanced fragmentation of precursors with charge states greater then 2+ (53). Recent glycopeptide studies have shown that precursors with m/z >850 exhibit reduced peptide fragment ion information because of decreased ETD efficiency at higher m/z (54). Our data conform to these studies because the glycopeptides predominantly identified by ETD here exhibited m/z below 1000 (only three of 34 peptides with m/z >1000). The major benefit of ETD was the maintenance of the glycan attached to Asn, enabling confirmation of the site of glycosylation. Optimization of ETD for a large modification (1406 Da for the C. jejuni glycan) and amino acid (Asn) requires the mass window to be widened to account for charge reduction and the mass distance between fragment ions around the site of the retained modification (Fig. 4, B and D).

Selective enrichment and effective peptide fragmentation are essential for the identification of novel glycosylation sites. Recent work described enrichment of C. jejuni glycopeptides by ion-pairing normal phase chromatography (26), although only nine peptides could be identified compared with 130 (corresponding to 75 glycosylation sites) by gel-free methods in our current study. This is most likely because of the use of MS3 by Ding et al. (26) that lowers the total number of unique ions that can be examined in a single experiment as sequential fragmentation events are required as well as the ion dilution effects that result in reduced ion intensities of MS2 and MS3 fragment ions. Our work has identified 81 glycosylation sites, 47 of which had not been previously recognized (one could not be unambiguously assigned). Prior to this study, only 44 sites had been identified (6, 7, 11, 12, 19–21, 24, 26) of which 33 were found here. Two previously identified sites we could not identify were from the plasmid-encoded protein VirB10 (21) that is not present in the HB93-13 strain used here. A further site in the Cj0864 protein (26) does not contain the sequon in HB93-13 or any theoretical C. jejuni proteome we examined and was previously thought to arise from a substitution/mutation event resulting in an Asp at the −2 position of the sequon (supplemental Table S4). The remaining eight sites we were unable to identify are located in larger tryptic peptides (1753.9–4555.3 Da; average, 2546.41 Da) compared with those identified by gel-free methods in our study (average, 1469.7 Da).

The 53 C. jejuni glycoproteins identified within this study were grouped by predicted function (Fig. 8). The largest cluster, apart from functionally unknown proteins, were those predicted to be involved in membrane transport, including that of small molecules and amino acids. A second cluster included proteins involved in cell membrane and shape maintenance (Fig. 8). Such proteins are thought to be involved in the in vivo survival of C. jejuni and to undergo extensive transcriptional changes in in vivo models of C. jejuni infection (55). We identified all three components of the CmeABC antibiotic efflux system, including CmeB (Cj0366c), the product of a gene that undergoes a 300-fold up-regulation during in vivo compared with in vitro growth (55) and that is critical for resistance to bile in the gastrointestinal system (56). This protein also represents an example of an extremely hydrophobic glycoprotein (12 predicted transmembrane-spanning regions and a GRAVY value of +0.259 (27)), which was previously unrecognized as it is not compatible with lectin affinity, gel-based strategies. Interestingly, a further efflux protein, CmeE, was also identified as a glycoprotein, although the other members of this second efflux system (CmeDF) do not contain N-linked sequons.

Comparison of identified sequons across several sequenced C. jejuni genomes showed that glycosylation sites are generally highly conserved (supplemental Table S4). The surface lipoprotein JlpA, however, is notable for the two sites it contains in most strains except NCTC11168 where only one site is present (24). NCTC11168 also does not maintain the 173DLNTS177 glycosylation site of Cj0843 due to a Ser → Gly alteration at residue 177. This suggests that alterations do exist between strains but are generally very rare for N-linked sites. We utilized multiple novel approaches to perform a comprehensive analysis of the C. jejuni glycoproteome. Our data show that CID/HCD and CID/ETD are complementary approaches for identifying sites of glycosylation in the presence of an attached glycan. We are also the first to show that multiple integral membrane proteins are glycosylated in C. jejuni, and by specifically examining such proteins using a peptide-based, gel-free approach, we have doubled the number of glycosylation sites within the verified C. jejuni glycoproteome. This work further demonstrates that peptide-centric approaches coupled to novel mass spectrometric fragmentation techniques may be suitable for application to eukaryotic glycoproteins for simultaneous elucidation of glycan structures and peptide sequence.

Footnotes

* This work was supported in part by grants from the Australian Research Council (ARC Grant DP0664922) and The University of Sydney (Bridging Support Grant U1336).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S4 and Figs. S1–S4.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S4 and Figs. S1–S4.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- ETD

- electron transfer dissociation

- 2-DE

- two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

- HCD

- higher energy collisional dissociation

- WCL

- whole cell lysates

- ZIC-HILIC

- zwitterionic hydrophilic interaction chromatography

- FA

- formic acid

- SBA

- soybean agglutinin

- Hex

- hexose

- HexNAc

- N-acetylhexosamine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zilbauer M., Dorrell N., Wren B. W., Bajaj-Elliott M. (2008) Campylobacter jejuni-mediated disease pathogenesis: an update. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102, 123–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Young K. T., Davis L. M., Dirita V. J. (2007) Campylobacter jejuni: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 665–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Janssen R., Krogfelt K. A., Cawthraw S. A., van Pelt W., Wagenaar J. A., Owen R. J. (2008) Host-pathogen interactions in Campylobacter infections: the host perspective. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21, 505–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nachamkin I. (2002) Chronic effects of Campylobacter infection. Microbes Infect. 4, 399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lecuit M., Abachin E., Martin A., Poyart C., Pochart P., Suarez F., Bengoufa D., Feuillard J., Lavergne A., Gordon J. I., Berche P., Guillevin L., Lortholary O. (2004) Immunoproliferative small intestinal disease associated with Campylobacter jejuni. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 239–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Young N. M., Brisson J. R., Kelly J., Watson D. C., Tessier L., Lanthier P. H., Jarrell H. C., Cadotte N., St Michael F., Aberg E., Szymanski C. M. (2002) Structure of the N-linked glycan present on multiple glycoproteins in the Gram-negative bacterium, Campylobacter jejuni. . J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42530–42539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kowarik M., Young N. M., Numao S., Schulz B. L., Hug I., Callewaert N., Mills D. C., Watson D. C., Hernandez M., Kelly J. F., Wacker M., Aebi M. (2006) Definition of the bacterial N-glycosylation site consensus sequence. EMBO J. 25, 1957–1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Linton D., Dorrell N., Hitchen P. G., Amber S., Karlyshev A. V., Morris H. R., Dell A., Valvano M. A., Aebi M., Wren B. W. (2005) Functional analysis of the Campylobacter jejuni N-linked protein glycosylation pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 1695–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Szymanski C. M., Yao R., Ewing C. P., Trust T. J., Guerry P. (1999) Evidence for a system of general protein glycosylation in Campylobacter jejuni. Mol. Microbiol. 32, 1022–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wacker M., Linton D., Hitchen P. G., Nita-Lazar M., Haslam S. M., North S. J., Panico M., Morris H. R., Dell A., Wren B. W., Aebi M. (2002) N-Linked glycosylation in Campylobacter jejuni and its functional transfer into E. coli. Science 298, 1790–1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nita-Lazar M., Wacker M., Schegg B., Amber S., Aebi M. (2005) The N-X-S/T consensus sequence is required but not sufficient for bacterial N-linked protein glycosylation. Glycobiology 15, 361–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kelly J., Jarrell H., Millar L., Tessier L., Fiori L. M., Lau P. C., Allan B., Szymanski C. M. (2006) Biosynthesis of the N-linked glycan in Campylobacter jejuni and addition onto protein through block transfer. J. Bacteriol. 188, 2427–2434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Szymanski C. M., Burr D. H., Guerry P. (2002) Campylobacter protein glycosylation affects host cell interactions. Infect. Immun. 70, 2242–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karlyshev A. V., Everest P., Linton D., Cawthraw S., Newell D. G., Wren B. W. (2004) The Campylobacter jejuni general glycosylation system is important for attachment to human epithelial cells and in the colonization of chicks. Microbiology 150, 1957–1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Helenius A., Aebi M. (2004) Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 1019–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kowarik M., Numao S., Feldman M. F., Schulz B. L., Callewaert N., Kiermaier E., Catrein I., Aebi M. (2006) N-Linked glycosylation of folded proteins by the bacterial oligosaccharyltransferase. Science 314, 1148–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Slynko V., Schubert M., Numao S., Kowarik M., Aebi M., Allain F. H. (2009) NMR structure determination of a segmentally labeled glycoprotein using in vitro glycosylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 1274–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rangarajan E. S., Bhatia S., Watson D. C., Munger C., Cygler M., Matte A., Young N. M. (2007) Structural context for protein N-glycosylation in bacteria: the structure of PEB3, an adhesin from Campylobacter jejuni. Protein Sci. 16, 990–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kakuda T., DiRita V. J. (2006) Cj1496c encodes a Campylobacter jejuni glycoprotein that influences invasion of human epithelial cells and colonization of the chick gastrointestinal tract. Infect. Immun. 74, 4715–4723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davis L. M., Kakuda T., DiRita V. J. (2009) A Campylobacter jejuni znuA orthologue is essential for growth in low zinc environments and chick colonization. J. Bacteriol. 191, 1631–1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Larsen J. C., Szymanski C., Guerry P. (2004) N-Linked protein glycosylation is required for full competence in Campylobacter jejuni 81-176. J. Bacteriol. 186, 6508–6514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carrillo C. D., Taboada E., Nash J. H., Lanthier P., Kelly J., Lau P. C., Verhulp R., Mykytczuk O., Sy J., Findlay W. A., Amoako K., Gomis S., Willson P., Austin J. W., Potter A., Babiuk L., Allan B., Szymanski C. M. (2004) Genome-wide expression analyses of Campylobacter jejuni NCTC11168 reveals coordinate regulation of motility and virulence by flhA. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20327–20338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gaynor E. C., Cawthraw S., Manning G., MacKichan J. K., Falkow S., Newell D. G. (2004) The genome-sequenced variant of Campylobacter jejuni NCTC 11168 and the original clonal clinical isolate differ markedly in colonization, gene expression, and virulence-associated phenotypes. J. Bacteriol. 186, 503–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scott N. E., Bogema D. R., Connolly A. M., Falconer L., Djordjevic S. P., Cordwell S. J. (2009) Mass spectrometric characterization of the surface-associated 42 kDa lipoprotein JlpA as a glycosylated antigen in strains of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Proteome Res. 8, 4654–4664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu X., McNally D. J., Nothaft H., Szymanski C. M., Brisson J. R., Li J. (2006) Mass spectrometry-based glycomics strategy for exploring N-linked glycosylation in eukaryotes and bacteria. Anal. Chem. 78, 6081–6087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ding W., Nothaft H., Szymanski C. M., Kelly J. (2009) Identification and quantification of glycoproteins using ion-pairing normal-phase LC and MS. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 2170–2185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cordwell S. J. (2006) Technologies for bacterial surface proteomics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 320–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lotan R., Beattie G., Hubbell W., Nicolson G. L. (1977) Activities of lectins and their immobilized derivatives in detergent solutions. Implications on the use of lectin affinity chromatography for the purification of membrane glycoproteins. Biochemistry 16, 1787–1794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Larsen M. R., Højrup P., Roepstorff P. (2005) Characterization of gel-separated glycoproteins using two-step proteolytic digestion combined with sequential microcolumns and mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4, 107–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Selby D. S., Larsen M. R., Calvano C. D., Jensen O. N. (2008) Identification and characterization of N-glycosylated proteins using proteomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 484, 263–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bakhtiar R., Guan Z. (2005) Electron capture dissociation mass spectrometry in characterization of post-translational modifications. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 334, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mikesh L. M., Ueberheide B., Chi A., Coon J. J., Syka J. E., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F. (2006) The utility of ETD mass spectrometry in proteomic analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1764, 1811–1822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alley W. R., Jr., Mechref Y., Novotny M. V. (2009) Characterization of glycopeptides by combining collision-induced dissociation and electron-transfer dissociation mass spectrometry data. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 23, 161–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Catalina M. I., Koeleman C. A., Deelder A. M., Wuhrer M. (2007) Electron transfer dissociation of N-glycopeptides: loss of the entire N-glycosylated asparagine side chain. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 21, 1053–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vik A., Aas F. E., Anonsen J. H., Bilsborough S., Schneider A., Egge-Jacobsen W., Koomey M. (2009) Broad spectrum O-linked protein glycosylation in the human pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4447–4452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Olsen J. V., Macek B., Lange O., Makarov A., Horning S., Mann M. (2007) Higher-energy C-trap dissociation for peptide modification analysis. Nat. Methods 4, 709–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gardy J. L., Laird M. R., Chen F., Rey S., Walsh C. J., Ester M., Brinkman F. S. (2005) PSORTb v. 2.0: expanded prediction of bacterial protein subcellular localization and insights gained from comparative proteome analysis. Bioinformatics 21, 617–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cordwell S. J., Len A. C., Touma R. G., Scott N. E., Falconer L., Jones D., Connolly A., Crossett B., Djordjevic S. P. (2008) Identification of membrane-associated proteins from Campylobacter jejuni strains using complementary proteomics technologies. Proteomics 8, 122–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hägglund P., Matthiesen R., Elortza F., Højrup P., Roepstorff P., Jensen O. N., Bunkenborg J. (2007) An enzymatic deglycosylation scheme enabling identification of core fucosylated N-glycans and O-glycosylation site mapping of human plasma proteins. J. Proteome Res. 6, 3021–3031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cordwell S. J. (2002) Acquisition and archiving of information for bacterial proteomics: from sample preparation to database. Methods Enzymol. 358, 207–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Larsen M. R., Cordwell S. J., Roepstorff P. (2002) Graphite powder as an alternative or supplement to reversed-phase material for desalting and concentration of peptide mixtures prior to matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry. Proteomics 2, 1277–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Domon B., Costello C. E. (1988) A systematic nomenclature for carbohydrate fragmentation in FAB-MS/MS spectra of glycoconjugate. Glycoconj. J. 5, 397–409 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roepstorff P., Fohlman J. (1984) Proposal for a common nomenclature for sequence ions in mass spectra of peptides. Biomed. Mass Spectrom. 11, 601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kjeldsen F., Hasekmann K. F., Budnik B. A., Jensen F., Zubarev R. A. (2002) Dissociative capture of hot (3–13 eV) electrons by polypeptide polycations: an efficient process accompanied by secondary fragmentation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 356, 201–206 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Good D. M., Wenger C. D., McAlister G. C., Bai D. L., Hunt D. F., Coon J. J. (2009) Post-acquisition ETD spectral processing for increased peptide identifications. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 20, 1435–1440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kjeldsen F., Giessing A. M., Ingrell C. R., Jensen O. N. (2007) Peptide sequencing and characterization of post-translational modifications by enhanced ion-charging and liquid chromatography electron-transfer dissociation tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 79, 9243–9252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Weerapana E., Imperiali B. (2006) Asparagine-linked protein glycosylation: From eukaryotic to prokaryotic systems. Glycobiology 16, 91R–101R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Szymanski C. M., Wren B. W. (2005) Protein glycosylation in bacterial mucosal pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 225–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hägglund P., Bunkenborg J., Elortza F., Jensen O. N., Roepstorff P. (2004) A new strategy for identification of N-glycosylated proteins and unambiguous assignment of their glycosylation sites using HILIC enrichment and partial deglycosylation. J. Proteome Res. 3, 556–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Han H., Xia Y., Yang M., McLuckey S. A. (2008) Rapidly alternating transmission mode electron-transfer dissociation and collisional activation for the characterization of polypeptide ions. Anal. Chem. 80, 3492–3497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Couttas T. A., Raftery M. J., Bernardini G., Wilkins M. R. (2008) Immonium ion scanning for the discovery of post-translational modifications and its application to histones. J. Proteome Res. 7, 2632–2641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Paizs B., Suhai S. (2005) Fragmentation pathways of protonated peptides. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 24, 508–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Good D. M., Wirtala M., McAlister G. C., Coon J. J. (2007) Performance characteristics of electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 1942–1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Darula Z., Medzihradszky K. F. (2009) Affinity-enrichment and characterization of mucin core 1-type glycopeptides from bovine serum. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 2515–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stintzi A., Marlow D., Palyada K., Naikare H., Panciera R., Whitworth L., Clarke C. (2005) Use of genome-wide expression profiling and mutagenesis to study the intestinal lifestyle of Campylobacter jejuni. Infect. Immun. 73, 1797–1810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lin J., Cagliero C., Guo B., Barton Y. W., Maurel M. C., Payot S., Zhang Q. (2005) Bile salts modulate expression of the CmeABC multidrug efflux pump in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7417–7424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]