Abstract

Oxidation is a common form of DNA damage to which purines are particularly susceptible. We previously reported that oxidized dGTP is potentially an important source of DNA 8-oxodGMP in mammalian cells and that the incorporated lesions are removed by DNA mismatch repair (MMR). MMR deficiency is associated with a mutator phenotype and widespread microsatellite instability (MSI). Here, we identify oxidized deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) as an important cofactor in this genetic instability. The high spontaneous hprt mutation rate of MMR-defective msh2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts was attenuated by expression of the hMTH1 protein, which degrades oxidized purine dNTPs. A high level of hMTH1 abolished their mutator phenotype and restored the hprt mutation rate to normal. Molecular analysis of hprt mutants showed that the presence of hMTH1 reduced the incidence of mutations in all classes, including frameshifts, and also implicated incorporated 2-oxodAMP in the mutator phenotype. In hMSH6-deficient DLD-1 human colorectal carcinoma cells, overexpression of hMTH1 markedly attenuated the spontaneous mutation rate and reduced MSI. It also reduced the incidence of −G and −A frameshifts in the hMLH1-defective DU145 human prostatic cancer cell line. Our findings indicate that incorporation of oxidized purines from the dNTP pool may contribute significantly to the extreme genetic instability of MMR-defective human tumors.

Mismatch repair (MMR) removes DNA mismatches that evade proofreading during replication. This versatile postreplicative repair system efficiently corrects single base mismatches and loops of one to three extrahelical nucleotides (insertion deletion loops [IDLs]) that arise during the replication of repetitive DNA tracts. IDLs are considered to be the result of spontaneous, slippage-dependent misalignment between primer and template DNA strands. Error correction is initiated by the binding by one of two mismatch recognition complexes that have overlapping specificities. This ensures efficient repair of all of the common replication errors. The hMutSα and hMutSβ mismatch recognition factors are heterodimers of hMSH2/hMSH6 and hMSH2/hMSH3, respectively. hMutSα preferentially initiates correction of base-base mismatches and small IDLs, whereas hMutSβ targets larger IDLs (for reviews, see references 26 and 31). Complete excision and replacement of the mismatched section of DNA also involves heterodimeric complexes between the hMLH1 and hPMS2 (or hMLH3) proteins, PCNA (43), RPA, DNA polymerase δ, and hEXO1 (44).

Because of its central role in replication error correction, cells in which MMR is incapacitated by inactivating mutations in hMSH2, hMLH1, hPMS2, or hMSH6 have high spontaneous mutation rates. This mutator effect is observed as a dramatic increase in the frequency of base substitutions and frameshifts. Frameshifts derive from uncorrected IDLs and are generally located in repetitive DNA sequences. These are located within the coding sequences of genes, as well as in the numerous noncoding microsatellite regions distributed throughout the genome. Alterations in the length of multiple microsatellites are a characteristic feature of MMR-deficient cells, and this microsatellite instability (MSI) is diagnostic for MMR deficiency in both cell lines and tumors (1).

MSI is a defining feature of tumors arising in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) families. HNPCC individuals have a germ line mutation in one of the MMR genes—most commonly hMSH2 or hMLH1. The increased mutation rate that accompanies somatic inactivation of the second allele accelerates the development of colorectal and other typical cancers in these individuals. In addition to these familial cases, a significant proportion of sporadic cancers exhibit MSI. In these cases, epigenetic silencing of an MMR gene, most commonly hMLH1, inactivates MMR. Organs, tumors, and cell lines from MMR gene knockout mice recapitulate this genetic instability and display both increased mutation rates and MSI (for a review, see reference 11). By analogy to HNPCC, the cancer proneness of these mice is generally considered to reflect an increased rate of accumulation of inactivating mutations in key target genes that normally function to prevent unlimited cellular proliferation.

Although it has been generally assumed that the mutator phenotype of MMR-deficient cells reflects uncorrected spontaneous DNA polymerase errors (42), MMR is also known to process some altered or damaged DNA bases. For example, O6-methylguanine, a lesion induced by treatment with methylating carcinogens, is known to miscode during DNA replication and DNA containing O6-methylguanine base pairs is bound by hMutSα (10, 17, 30). As a result, MMR-defective cells are hypermutable by these agents (3) and this hypermutability by spontaneous DNA lesions is a potential contributor to the mutator phenotype.

Oxidation is a significant and constant source of spontaneous DNA damage. The oxidized purine 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoG) is a particularly frequent DNA lesion that, during replication, can form base pairs with adenine (41) to promote the formation of G → T transversions (46, 12). The extent of the threat posed by DNA 8-oxoG is emphasized by the existence of a highly conserved three-tier system that protects against the mutagenic properties of 8-oxoG. Two complementary arms of the base excision repair (BER) pathway bring about the removal of 8-oxoG from DNA. In the first, the hOGG1 DNA glycosylase initiates excision of the oxidized purine from resting DNA in which 8-oxoG is paired with C. An additional BER pathway, initiated by the MYH DNA glycosylase, a homolog of the Escherichia coli MutY protein, removes adenine misincorporated opposite 8-oxoG during replication. This promotes the eventual removal of the oxidized purine from DNA via hOGG1-mediated processing of the 8-oxoG · C base pairs generated during repair. Purine dNTPs are also subject to oxidative damage, and the oxidized products are substrates for incorporation into DNA during replication. To avoid this, human cells sanitize the dNTP pool by hydrolyzing oxidized purine dNTPs. This degradation is carried out by hMTH1, a homolog of the E. coli MutT protein that hydrolyzes 8-oxodGTP (36).

There is mounting evidence that MMR also contributes to reducing the burden of oxidized DNA bases. Treatment of E. coli MMR mutants with H2O2 increases the instability of repetitive sequences in extrachromosomal plasmid DNA (25). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the mutator phenotype of MSH2- and MSH6-defective strains is significantly decreased by anaerobic growth, suggesting that a large fraction of spontaneous mutagenesis in MMR-deficient strains is caused by the persistence of oxidatively damaged bases (18). Yeast MMR processes 8-oxoG · A base pairs, and its ability to excise A incorporated opposite 8-oxoG may compensate for the apparent absence of a MutY homolog in this organism (37). The mammalian MMR system also participates in minimizing the levels of oxidative DNA damage. Thus, the steady-state level of DNA 8-oxoG is significantly elevated in MMR-deficient mouse (15) and human (14) cells. Consistent with this, hMutSα binds to some 8-oxoG-containing base pairs (35). The efficiency of excision of the oxidized purine by BER appears to be similar in MMR-proficient and -defective cells. We have provided evidence that MMR removes 8-oxodGMP incorporated during replication (14) and suggested that this new role for MMR represents a fourth level of protection against the dangers of oxidized DNA bases.

To determine the full impact of incorporated oxidized DNA precursors on spontaneous mutation in MMR-defective cells, we characterized spontaneous mutations in msh2−/− mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) in which hMTH1 cDNA is expressed. We also analyzed the influence of increased hMTH1 expression on MSI. The findings indicate that (i) the oxidized purine dNTP pool is a significant contributor to mutation in MMR-deficient cells, (ii) both 8-oxodGTP and 2-oxodATP are implicated in mutation, and (iii) incorporation of oxidized DNA precursors is a significant influence on MSI in repair-defective human tumor cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, DNA transfection, and analysis of hMTH1 activity in transfectants.

All cells were grown routinely in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Gibco-BRL). Cell lines were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere (90% nominal humidity). Exponentially growing msh2−/− MEFs were transfected (Lipofectamine; GIBCO-BRL) with pcDEBdelta carrying hygromycin resistance together with the cDNA for hMTH1d, the major 18-kDa form of hMTH1 (29). Hygromycin (400 μg/ml; GIBCO-BRL)-resistant clones were isolated after 15 to 20 days. hMTH1 expression in transfectants was quantitated by measurement of dGTPase activity in cell extracts and monitored by Western blotting as previously described (14). For dGTPase determinations, extracts were prepared from 2 × 107 cells in 200 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)-1 mM EDTA-10 mM dithiothreitol-0.2% Triton X-100. Reaction mixtures (20 μl) contained 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 8 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 100 μM [α-32P]dGTP (2 Ci/mmol; Amersham), and cell extract. Following 10 min of incubation at 37°C, reactions were terminated by chilling to 0°C and addition of EDTA to 10 mM. Aliquots (2.5 μl) were applied to thin-layer polyethyleneimine-cellulose plates, which were developed in 1 M LiCl. Dried plates were exposed to X-rays film, and dGTP and dGMP were quantitated by using the National Institutes of Health V1.59 software package. One unit of hMTH1 produces 1 pmol of dGMP per min in the standard assay. For Western blotting cell extracts were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-7.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane with a Trans-Blot cell apparatus (Bio-Rad), and probed overnight with anti-hMTH1 antibody, followed by the appropriate secondary antibody. Blots were developed by using the ECL detection reagents (Amersham).

8-OxoG determinations.

8-OxodG was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (HPLC/EC) as previously described (7) following DNA extraction, RNase treatment, and enzymatic hydrolysis. DNA was extracted by a high-salt protein precipitation method. Briefly, cells were lysed with sodium dodecyl sulfate and digested with protease (Qiagen) at 37°C for 1 h. Proteins were precipitated by adding NaCl to 1.5 M, and DNA in the supernatant was collected by addition of 2 volumes of ethanol. The DNA pellet was resuspended in Tris-EDTA, incubated with RNases A and T1 at 37°C for 1 h, and precipitated again with ethanol. Enzymatic digestion was then performed at 37°C with nuclease P1 (Boehringer Mannheim) for 2 h and alkaline phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim) for 1 h. Enzymes were precipitated by addition of CHCl3, and the upper layer was stored for analysis of 8-oxodG at −80°C under N2. The DNA hydrolysate was analyzed by HPLC/EC (Coulochem I; ESA Inc.) with a C18 5-μm Uptishere column (250 by 46 mm; Interchim) equipped with a C18 guard column. The eluent was 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 5.5, containing 9% methanol, at a flow rate of 0.7 ml/min. The potentials applied were 150 and 400 mV for E1 and E2, respectively. The retention time of 8-oxodG was ∼23 min. Deoxyguanosine was measured in the same run of corresponding 8-oxodG with a UV detector (model SPD-2A; Shimadzu) at 256 nm; the retention time was ∼17 min.

Mutation rate analysis at the hprt gene and DNA sequencing of mutants.

Cells were plated at low density (100 cells/dish) and grown in complete medium to a density of 0.4 × 106 to 1 × 106 per dish before plating of the entire culture (50 to 60 independent cultures) into medium supplemented with 6-thioguanine (5 μg/ml; Sigma). The mutation rate was calculated as μ = M C−1 ln2, where C is the number of cells at selection time and M is −ln(P0), where P0 is the proportion of cultures with no mutants. One 6-thioguanine-resistant mutant was isolated per culture to ensure mutation independence. Cytoplasmic RNA was extracted and used to synthesize hprt cDNA by SuperScript One-Step reverse transcription-PCR (Invitrogen) in a final volume of 50 μl containing 1 μg of RNA, 0.2 μM primers (45), RT/Platinum TaqMix (1 μl), and buffer provided with the enzyme. Cycles included 30 s at 55°C; 2 min at 94°C; 35 cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C; and a final 10 min at 72°C. Reverse transcription-PCR products were cleaned with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen), used in sequencing reactions (25 cycles of 10 s at 96°C, 5 s at 50°C, and 4 min at 60°C), and analyzed with an ABI Prism 310 automatic sequencer.

MSI.

Genomic DNA was isolated from subclones of clonal isolates of DLD1, DLD1/clone 2A, DU145, and DU145/clone 1. Ninety-six-well plates were seeded at a density of <1 cell/well, and DNA was prepared from approximately 2 × 104 cells/well. DNA samples (10 ng) were used in PCRs with BAT26, BAT25, or SMT15 primers (2 pmol/μl), dNTPs (200 mM) in a reaction buffer containing 0.5 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). Following the initial denaturation (95°C for 2 min), BAT26 and BAT25 were amplified by 35 cycles of 60 s at 95°C, 60s at 55°C, and 60 s at 72°C, followed by 10 min at 72°C. SMT15 was amplified by using a four-stage protocol (49) as follows: four cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 64°C, and 2 min at 70°C; four cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 61°C, and 2 min at 70°C; four cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 58°C, and 2 min at 70°C; and four cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 2 min at 70°C. Amplification products (10 μl) were digested with 0.4 U of T4 DNA polymerase (Roche) for 30 min at 37°C, denatured in deionized formamide for 2 min at 95°C, and analyzed with an ABI Prism 310 automatic sequencer.

RESULTS

Biological consequences of hMTH1 overexpression.

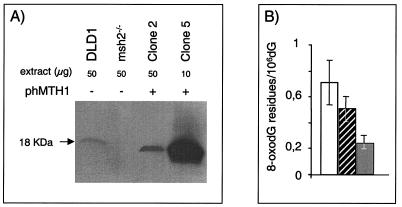

hMTH1 cDNA (29) was transfected into msh2-defective MEFs (14). hMTH1 expression in pooled transfectants and clonal isolates was measured by dGTPase assay and Western blotting. The low level of dGTPase activity in untransfected msh2−/− MEFs (0.4 U/mg of protein) was increased 10-fold in the pooled transfectants (pool 1) and also in a clonal isolate, clone 2, that contained 4.2 and 3.9 U/mg of protein, respectively. Screening of individual transfectants identified clone 5, in which dGTPase activity was increased around 50-fold, to 20.4 U/mg of protein. Western blotting of clone 2 and 5 extracts confirmed that the enhanced enzyme activity was correlated with an increased level of the hMTH1 protein (Fig. 1A). The apparent absence of the mouse MTH protein from untransfected msh2−/− extracts is most likely due to the low affinity of the human antibody for its mouse homolog since hMTH1 was detectable in Western blots of extracts of human DLD1 cells that contain comparable enzyme activity (0.6 U/mg of protein).

FIG. 1.

Expression of hMTH1 in msh2-defective MEFs. (A) Western blot of msh2−/− MEFs. Clone 2 and 5 extracts were probed with antibody against hMTH1. The DLD1 human colorectal carcinoma cell line is shown for comparison. (B) Steady-state levels of DNA 8-oxoG in untransfected and hMTH1-transfected msh2−/− MEFs. DNA was extracted from exponentially growing cells, and 8-oxoG was determined by HPLC/EC as described in Materials and Methods. Values are the mean ± standard deviation of several independent determinations (n = 7 for msh2−/−; n = 5 for clones 2 and 5). Data for untransfected msh2−/− MEFs (unfilled bar), clone 2 (hatched bar), and clone 5 (filled bar) are shown.

hMTH1 expressed in msh2−/− MEFs was active in excluding 8-oxodGMP from DNA. Direct measurements of DNA 8-oxodG in clones 2 and 5 confirmed that the steady-state level of the oxidized purine was significantly reduced from around 0.7 8-oxodG residues per 106 dGMP residues in nontransfected msh2−/− MEFs to 0.5 and 0.25 8-oxodG residues per 106 dGMP residues in clones 2 and 5, respectively (Fig. 1B).

hMTH1 expression reduced the mutator effect in msh2−/− MEFs. There was an inverse relationship between hMTH1 expression and the hprt mutation rate (Table 1). The rate in msh2−/− MEFs was 3.1 × 10−6 mutations/cell/generation (mean of the three independent determinations), a value 25-fold higher than rates in wild-type mouse cells (16). This value is compatible to the reported 10- to 20-fold increase in spontaneous mutation rates in msh2−/− mouse tissues (4). Modest hMTH1 overexpression (around 10 times the endogenous level) in the pooled transfectants and in clone 2 halved this to 1.4 × 10−6 mutations/cell/generation. The 50-fold-enhanced hMTH1 expression in clone 5 was associated with a 17-fold reduction to 0.18 × 10−6 mutations/cell/generation. This is close to the calculated values for wild-type mouse cells (16). (We were unable to calculate mutation rates in msh2+/+ MEFs because of multiple copies of the hprt gene.) Transfection with the empty vector did not alter the hprt mutation frequency, and Western blot analysis indicated that all hMTH1-expressing clones remained msh2 defective (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Mutation rates at the hprt gene in untransfected and hMTH1-expressing msh2−/− MEFs

| Cells | No. of replica cultures | Final cell no. (105) | Fraction of culture without mutants (P0) | Mutation rate (μ) ± SD (10−6) | Mean value of μ | Relative mutation rate decrease | hMTH1 activity (U/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| msh2−/− MEFs | |||||||

| Expt 1 | 50 | 7.25 | 3/50 | 2.69 ± 0.40 | 3.06 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Expt 2 | 50 | 5.32 | 15/50 | 1.57 ± 0.28 | |||

| Expt 3 | 44 | 4.33 | 2/44 | 4.29 ± 0.28 | |||

| hMTH1 pool 1 | 48 | 8.26 | 3/48 | 1.94 ± 0.39 | 1.6 | 4.2 | |

| hMTH1 clone 2 | |||||||

| Expt 1 | 10 | 10.69 | 1/10 | 1.49 ± 0.63 | 1.38 | 2.1 | 3.9 |

| Expt 2 | 50 | 3.80 | 25/50 | 1.26 ± 0.25 | |||

| hMTH1 clone 5 | |||||||

| Expt 1 | 50 | 8.15 | 42/50 | 0.148 ± 0.052 | 0.18 | 16.9 | 20.4 |

| Expt 2 | 50 | 12.30 | 41/50 | 0.112 ± 0.037 | |||

| Expt 3 | 54 | 12.00 | 33/54 | 0.284 ± 0.063 |

These findings indicate that a substantial fraction of mutations arising in msh2-defective MEFs are prevented by improved dNTP pool sanitation. In particular, a 50-fold-increased hMTH1 expression level effectively abolishes the mutator phenotype associated with msh2 deficiency. Incorporation of oxidized dNTPs is therefore a major contributor to the mutator phenotype of msh2−/− MEFs.

hMTH1 and the hprt mutational spectrum.

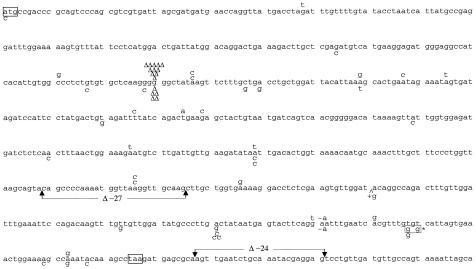

hMTH1 hydrolyzes several oxidized purine dNTPs, including 8-oxodGTP, 2-oxodATP, and 8-oxodATP (20). In order to investigate the contribution of these oxidized precursors to spontaneous mutagenesis in MMR-defective cells, we compared spontaneous hprt mutational spectra in msh2−/− MEFs and hMTH1-overexpressing clone 5. Independent mutants from both cell lines were sequenced. Table 2 shows the frequency and rate of each type of mutation for each cell line. As expected for MMR-deficient cells, frameshifts were the major single mutational type in msh2−/− MEFs. They comprised more than one-third of all mutations (12 of 33; 36.4%). Base substitutions comprised around 60% of the total and were equally distributed between transitions and transversions (27.2 and 33.4%, respectively). There was a significant predominance of AT → GC over other transitions (8 of 33 mutations; 24.2%), whereas the four possible transversions were approximately equally represented.

TABLE 2.

Class distribution of hprt mutations occurring in untransfected msh2−/− MEFs and hMTH1-expressing clone 5

| Change(s) | Untransfected msh2−/−

|

hMTH1-expressing clone 5

|

Reduction factora | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occurrence (%) | Mutation rate (10−7) | Occurrence (%) | Mutation rate (10−7) | ||

| Frameshifts | 12 (36.4) | 11.3 | 7 (22.6) | 0.41 | 27.6 |

| Transitions | |||||

| G · C → A · T | 1 (3.0) | 0.9 | 0 | ||

| A · T → G · C | 8 (24.2) | 7.5 | 3 (9.7) | 0.17 | 44.1 |

| Transversions | |||||

| A · T → C · G | 3 (9.1) | 2.8 | 15 (48.4) | 0.87 | 3.2 |

| A · T → T · A | 4 (12.1) | 3.7 | 1 (3.2) | 0.06 | 61.7 |

| G · C → C · G | 2 (6.1) | 1.9 | 3 (9.7) | 0.17 | 11.2 |

| G · C → T · A | 2 (6.1) | 1.9 | 1 (3.2) | 0.06 | 31.7 |

| Large deletions | 1 (3.0) | 0.9 | 1 (3.2) | 0.06 | 15.0 |

| Total | 33 | 3.1 | 31 | 0.18 | 17.2 |

Fold decrease in the mutation rate in hMTH1-expressing clone 5.

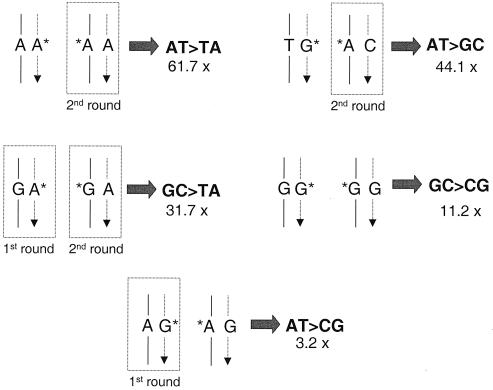

hMTH1 expression in clone 5 cells altered the distribution of mutations. The contributions of frameshifts and transitions were both reduced. When the differences in mutation rate between msh2−/− MEFs and clone 5 are taken into account, hMTH1 expression decreased the rates of frameshifts 27.6-fold and of A · T → G · C transitions 44.1-fold. There was a more modest effect on the rate of transversions, which was reduced only 8.9-fold. AT → TA and GC → TA mutations were particularly affected, whereas there was a surprisingly minimal impact on A → C transversion rates, which were reduced only 3.2-fold.

The type and location of the mutation, the surrounding sequence, and the resulting amino acid change are summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 2. Base substitutions appeared to be randomly distributed, although there was some clustering, e.g., the four base substitutions at position 581 in clone 5. In a single case (mutant 53), a double mutation, formed by two TA → GC transversions within three base pairs, was found in clone 5. In contrast, essentially all frameshifts were located within the run of six consecutive guanines at positions 207 to 213, which are a known frameshift hot spot in MMR-defective cells (30). Within this hot spot, all of the mutations scored were −1 deletions. A single +G frameshift was observed in clone 5, and it was located in a nonrepetitive sequence. We conclude that overexpression of hMTH1 reduced the rate of −1 frameshift mutations within the acknowledged G6 target by 34-fold. Thus, improved dNTP pool sanitation has a profound effect on the incidence of the type of mutations that are regarded as signatures of MMR deficiency. The striking reduction in frameshifts in the G6 target suggests that incorporation of 8-oxodGMP influences the generation of these mutations in an MMR-deficient cell.

TABLE 3.

Spontaneous mutations in hprt locus of untransfected msh2−/− MEFs and hMTH1-expressing clone 5

| Site | Target sequencea | Mutation | Codon | Amino acid change | Mutant(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| msh2−/− | |||||

| 58 | CCTAGATTT | G→T | GAT→TAT | Asp→Tyr | 9 |

| 191 | GTGGCCCTC | C→G | GCC→GGC | Ala→Gly | 2 |

| 202 | TGTGCTCAA | C→T | CTC→TTC | Leu→Phe | 23 |

| 217 | CTATAAGTT | A→G | AAG→GAG | Lys→Glu | 18, 37 |

| 249 | TTAAAGCAC | A→G | AAA→AAG | Stop | 26 |

| 257 | CTGAATAGA | A→C | AAT→ACT | Asn→Thr | 39 |

| 265 | AAATAGTGA | A→T | AGT→TGT | Ser→Cys | 1 |

| 296 | GATTTTATC | T→C | TTT→TCT | Phe→Ser | 32 |

| 305 | AGACTGAAG | T→A | CTG→CAG | Leu→Gln | 13 |

| 309 | TGAAGAGCT | G→C | AAG→AAC | Lys→Asn | 15 |

| 207-213 | AAGGGGGGCT | −G | 6, 7, 11, 20, 21, 27, 30, 33, 38, 42, 49 | ||

| 385 | AAAGAATGT | A→T | AAT→TAT | Asn→Tyr | 12 |

| 409 | TATAATTGA | A→T | ATT→TTT | Ile→Phe | 19 |

| 476 | GTTAAGGTT | A→C | AAG→ACG | Lys→Thr | 4, 45 |

| 496 | GGTGAAAAG | A→G | AAA→GAA | Lys→Glu | 35 |

| 599 | TTCAGGAAT | G→T | AGG→AGT | Arg→Met | 29 |

| 601-602 | CAGGAATTT | −A | 25 | ||

| 611 | AATCACGTT | A→G | CAC→CGC | His→Arg | 28 |

| 643 | AGCCAAATA | A→G | AAA→GAA | Lys→Glu | 36 |

| 668 | CGCAAGTTG | A→G | AGT→GGT | Ser→Gly | 14 |

| 668-691 | Deletion (−24) | 16 | |||

| Clone 5 | |||||

| 1 | GTCATGCCG | A→C | ATG→CTG | Met→Leu | 20 |

| 143 | GAAAGACTT | G→C | AGA→ACA | Arg→Thr | 29 |

| 197 | CTCTGTGTG | G→C | TGT→TCT | Cys→Ser | 12 |

| 207-213 | AAGGGGGGCT | −G | 4, 5, 9b, 21, 43 | ||

| 208 | CAAGGGGGG | G→T | GGG→TGG | Gly→Trp | 18b |

| 227 | TTTGCTGAC | C→G | GCT→GGT | Ala→Gly | 36 |

| 230 | GCTGACCTG | A→G | GAC→GGC | Asp→Gly | 27a |

| 249 | TTAAAGCAC | A→T | AAA→AAT | Lys→Asn | 47b |

| 290 | ACTGTAGAT | T→G | GTA→GGA | Val→Gly | 25 |

| 349 | AGTTATTGG | A→C | ATT→CTT | Ile→Leu | 13 |

| 370 | CTCAACTTT | A→C | ACT→CCT | Asn→Pro | 2 |

| 409 | ATAATTGAC | A→C | ATT→CTT | Ile→Leu | 14, 27 |

| 459-485 | Deletion (−27) | 40 | |||

| 521 | GGAT ACA | +G | 7 | ||

| 563 | GTTGTTGGA | T→G | GTT→GGT | Val→Gly | 7a |

| 581 | CTTGACTAT | A→G | GAC→GGC | Asp→Gly | 26 |

| 581 | CTTGACTAT | A→C | GAC→GCC | Asp→Ala | 28, 54, 23b |

| 601-602 | CAGGAATTTG | −A | 41 | ||

| 618 | GTTTGTGTCAT | T→G | TGT→TGG | Cys→Trp | 34 |

| 618 | GTTTGTGTCAT | T→G | TGT→TGG | Cys→Trp | 53* |

| 620 | GTTTGTGTCAT | T→G | GTC→GGC | Val→Gly | 53* |

| 639 | GAAAAGCCA | A→C | AAA→AAC | Lys→Asn | 6b |

| 643 | AAGCCAAATAC | A→G | AAA→GAA | Lys→Glu | 10 |

| 647 | AAATACAAA | A→C | TAC→TCC | Tyr→Ser | 35 |

Nucleotides affected are in boldface.

FIG. 2.

Locations of hprt mutations in msh2−/− MEFs and in clone 5. Changes found in msh2−/− MEFs and in clone 5 are shown above and below the sequence, respectively. Deletions are indicated by Δ and are single bases unless otherwise indicated. +g is a single-base insertion. The asterisk indicates a double mutant.

hMTH1 overexpression and the mutator phenotype in MMR-defective human cells.

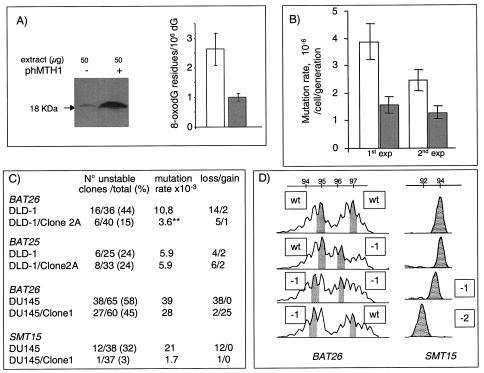

To determine whether improved dNTP pool sanitation affected the mutator phenotype of MMR-defective human cells, hMTH1 was overexpressed in the hMSH6-defective human colorectal carcinoma DLD1 cells. Clone 2A expressed a 10-fold-increased level of hMTH1, as determined by enzyme assay and Western blotting. This is comparable to that of clone 2 of the transfected msh2−/− MEFs (Fig. 3A). This increased hMTH1 expression reduced steady-state DNA 8-oxoG from 2.6 residues per 106 dGMP residues in DLD-1 to 0.9 residues per 106 residues in DLD1/clone 2A. The spontaneous HPRT mutation rate also decreased by two- to threefold in two independent experiments: from 3.9 × 10−6 to 1.5 × 10−6 per cell/generation and from 2.4 × 10−6 to 1.2 × 10−6 per cell/generation (Fig. 3B). These changes are comparable to those we observed in msh2−/− MEFs expressing similar levels of hMTH1. Oxidized purine deoxynucleotides make a significant contribution to the mutator phenotype of these MMR-defective human colorectal carcinoma cells.

FIG. 3.

hMTH1 overexpression and the mutator phenotype of MMR-defective human cells. (A) Western blotting and steady-state levels of DNA 8-oxoG in untransfected DLD-1 (− and unfilled bar) and hMTH1-overexpressing clone 2A (+ and filled bar). Values for 8-oxoG determinations are the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. (B) HPRT mutation rates in untransfected DLD-1 (unfilled bars) and clone 2A (filled bars). Two independent determinations are shown. (C) MSI at BAT26, BAT25, and SMT15. DNAs from independent subclones of untransfected DLD-1 and DU145 and their hMTH1-overexpressing clones (DLD-1/clone 2A and DU145/clone 1) were amplified by PCR. The total number and the number of unstable clones are shown together with the percentage of unstable clones. Mutation rates were calculated as follows: number of unstable clones/total number of clones × number of generations. The number of clones with −1/−2 changes (loss) or +1/+2 changes (gain) is indicated. (D) Examples of MSI at BAT26 and SMT15 in DU145. The values designate different allele sizes. The alterations are shown next to the appropriate panel. wt, wild type.

MSI is the most dramatic manifestation of the mutator effect in MMR-deficient human tumors. We therefore examined whether hMTH1 expression affected MSI in DLD-1. Single nucleotide frameshifts within mononucleotide repeats predominate in these hMSH6-defective cells (6). We therefore examined the BAT26 mononucleotide repeat (A26) microsatellite. Subclones of DLD-1 and of DLD-1/clone 2A were isolated by single-cell plating, and the BAT26 repeat was analyzed by PCR. BAT26 alleles were altered in 16 (44%) of 36 DLD-1 subclones. This corresponds to a mutation rate of 10.8 × 10−3 per generation at this locus. Expression of hMTH1 in DLD-1/clone 2A reduced the frequency of BAT26 mutation threefold, to 15% (6 of 40; Fisher exact test, P = 0.003), corresponding to a rate of 3.6 × 10−3 per generation (Fig. 3C). A similar analysis of the BAT25 (A25) locus did not reveal a difference between DLD1 and DLD-1/clone 2A, however. The overwhelming majority of changes in BAT26 were base losses. This bias was also observed in the hMTH1-expressing clones. Thus, hMTH1 expression clearly influences MSI by reducing the frequency of −A deletions in BAT26. The unchanged mutation rate at BAT25 suggests that the contribution of oxidized purines is influenced by the sequence context of the repeat.

We also examined the effect of hMTH1 on MSI in the human prostatic cancer cell line DU145. This MMR-defective cell line has a profound mutator phenotype and bears mutations in both the hMLH1 and hMSH3 MMR genes (9). The BAT26 mutation rate was reduced 1.3-fold by 10-fold-increased hMTH1 activity in a clonal isolate (DU145/clone 1). More strikingly, hMTH1 expression dramatically altered the nature of the changes at BAT26. All (38 of 38) BAT26 mutations in DU145 were single A deletions. In contrast, there were only 2 deletions (of 27) among DU145/clone 1 mutations. This indicates that hMTH1 has a selective effect in reducing −1-base changes. This possibility was explored further by analyzing the SMT15 locus, which contains a run of eight G's. Increased hMTH1 expression in DU145/clone 1 reduced the mutation rate at this locus 10-fold (Fig. 3C). Again, all of the changes in DU145 were −G deletions. Examples of changes at BAT26 and SMT15 are shown in Fig. 3D. Thus, BAT26 and SMT15 provide clear evidence that oxidized NTPs have a significant influence on MSI. This can affect both A and G repeat microsatellites. The stability of BAT25 indicates that exceptions do exist and that additional factors, such as surrounding sequences, may also play a part. The selective effect of hMTH1 expression in reducing the frequency of −1-base deletions is particularly noteworthy.

Thus, hMTH1 expression affects two of the defining characteristic of MMR-defective cells. It reduces HPRT mutation rates. It also significantly ameliorates MSI at some, but not all, loci by preventing −1-base deletions. We conclude that the pool of oxidized purine dNTPs significantly influences the mutator phenotype of MMR-defective cells.

DISCUSSION

We previously demonstrated that the oxidized dNTP pool makes a significant contribution to the steady-state level of oxidized purine bases in DNA of MMR-defective cells and suggested that this is likely to be an important factor in their genomic instability (14). Here we provide direct evidence that improved dNTP pool sanitation attenuates two defining features of genetic instability in MMR-defective cells. Overexpression of hMTH1 in msh2−/− MEFs reduced mutation rates in the expressed hprt gene. It influenced the incidence of several different types of base substitution and prevented frameshifts in the acknowledged G6 target in this gene. Overexpression of hMTH1 in two MMR-defective human cell lines significantly reduced instability at mononucleotide repeats, indicating that oxidized dNTPs are a significant contributor to MSI. This effect was to some extent locus dependent and selectively affected −1-base changes.

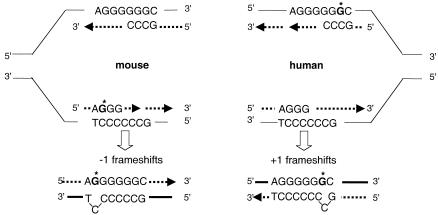

The mutational spectrum in msh2−/− MEFs that express a high level of hMTH1 provides important clues to the events underlying their mutator phenotype. The range of hMTH1 substrates includes 8-oxodGTP, 2-oxodATP, and 8-oxodATP (20). One important implication of our data is that incorporation of both oxidized guanine and adenine contributes significantly to the mutator effect of MMR-defective cells. By comparison to 8-oxoadenine (47), 8-oxoG and 2-oxoA are both considered to be highly mutagenic. The pairing properties of 2-oxoA are particularly promiscuous, and it can direct incorporation of dCMP or dAMP to produce AT → GC transitions and AT → TA transversions, respectively (28). The most dramatic effect of hMTH1 expression was on the last two classes of base substitutions. AT → GC and AT → TA mutation rates decreased 44- and 62-fold, respectively. The most straightforward explanation for these findings is that during replication, 2-oxodAMP is incorporated opposite T. In the absence of MMR, the oxidized purine persists and forms the premutagenic mismatches 2-oxoA · C and 2-oxoA · A in the following round of replication (Fig. 4). It is interesting that a large increase in mutations at A · T base pairs is the major factor in the increased mutator phenotype of thymic lymphomas that arise in msh2−/− mice (50).

FIG. 4.

Oxidized purines and mutations in msh2−/− MEFs expressing hMTH1. The major mutational types that are modulated by hMTH1 expression (fold decrease in rate indicated) are shown. It is proposed that mutations arise via oxidized purines that are incorporated into the daughter DNA strand (dotted line, arrowed) during DNA replication. In some cases, the same mutations can be derived from replication of template oxidized base incorporated during a previous round of replication. These are shown where appropriate. Base pairs involving oxidized bases shown boxed are those that have been previously identified by studies using purified DNA polymerases or inferred from in vitro replication studies. Template strands are designated by solid lines. AT → TA transversions and AT → GC transitions are considered to arise from incorporation of 2-oxodAMP opposite the correct base and miscoding of oxidized A (A*) present in the parental strand in the second round of replication (28). Incorporation of 2-oxodAMP opposite a G (24, 38) or miscoding of 8-oxoG when present in the template strand might both lead to GC → TA transversions (46, 12). GC → CG transversions derive from G* · G mismatches. DNA polymerase eta is indeed able to direct, at low efficiency, the incorporation of guanine opposite a template 8-oxoG (23, 48). Incorporation of 8-oxodGMP opposite an A by replicative DNA polymerases (40) is the most plausible mismatch originating AT → CG transversions.

2-OxodAMP is also directly mutagenic. It can be incorporated opposite G (27) to generate GC → TA transversions (24, 38). Consistent with a simple reduction in the level of 2-oxodAMP incorporation, hMTH1 expression also prevented this type of mutation. We note, however, an alternative route by which these mutations may arise that is also susceptible to modulation by hMTH1. GC → TA transversions are signature mutations of template 8-oxoG. They could arise at persistent 8-oxodGMP that was incorporated in a previous replication round (Fig. 4). The contribution of persistent 8-oxodGMP is likely to be minimized by BER mediated by Ogg-1 and Myh, both of which are fully operative in these MMR-defective cells. We suggest that reversing the potentially mutagenic incorporation of 2-oxodAMP is a previously unrecognized function of MMR.

The minimal impact of hMTH1 expression (only threefold) on AT → CG transversions is surprising. These mutations arise via the A · 8-oxoG mismatches that are an acknowledged product of 8-oxodGMP incorporation in in vitro replication systems (40). In addition, the mutator phenotype of E. coli mutT mutant strains is largely due to increases in this class of transversions (2). The modest effect of hMTH1 overexpression suggests that the majority of AT → CG transversions in an MMR-defective background are the consequence of A · G mismatches.

One of the most significant findings is the dramatic reduction in −G frameshifts in the G6 tract of the hprt gene. This identifies oxidized dNTPs as a major contributor to frameshift mutagenesis in these msh2−/− cells—a finding that is consistent with the reported phenotype of mth1 knockout mice. Although these animals do not have an overt mutator phenotype, they do display an increased frequency of −A frameshifts in mononucleotide runs of the transgenic rpsL gene (19). We conclude that, in addition to causing base substitutions, oxidized dNTPs make a significant contribution to the production of −1-base frameshifts that are normally corrected by the mouse MMR system.

Increased hMTH1 expression in the two MMR-deficient human cell lines provided further evidence that oxidized dNTPs contribute to the mutator effect of repair-defective cells—and that they particularly influence frameshifts. Although we were unable to isolate transfectants with high hMTH1 expression, a modest level had a significant impact on the phenotype of both DLD-1 and DU145. The HPRT mutation rate in DLD-1 was reduced between two and threefold. Since the majority of HPRT− mutations in these hMSH6-deficient cells are base substitutions—with a relatively minor contribution from frameshifts (5, 34)—these data are consistent with hMTH1 preventing base substitutions in human HPRT as it does in its mouse counterpart. hMTH1 expression in DLD-1 also provided evidence of a significant impact on frameshifts—and by implication on MSI. The mutation rate at BAT26 was reduced about threefold. Although hMTH1 expression in hMHL1-defective DU145 did not produce a measurable decrease in the overall HPRT mutation rate (unpublished observation), it confirmed the influence on frameshifts. Although the decrease in the mutation rate at BAT26 was modest, it was accompanied by a 10-fold reduction in the rate in the G8 tract of SMT15. There were also important qualitative changes. Loss of the hMLH1 (but also of hPMS2 or hMSH2) MMR proteins in human tumor cell lines leads to an accumulation of +G frameshifts in the G6 target sequence of the HPRT gene (5, 39, 22). hMTH1 expression in the human cell lines, as in the msh2−/− MEFs, selectively affected minus frameshifts. This was apparent at both BAT26 and SMT15. Thus, oxidized dNTPs contribute to the generation of single-base deletions in repetitive mononucleotide sequences of MMR-defective human and mouse cells.

These findings have two important implications. The first concerns the designation of MSI. There are two An mononucleotide runs in the recommended panel of microsatellites (8). Our findings indicate that instability at BAT26 is likely to be influenced by changes in oxidative metabolism that increase steady-state levels of oxidized purine dNTPs. Secondly, the selective influence of oxidized dNTPs on −1 deletions has implications for the measurement of mutation rates. HPRT provides a particularly good example. In MMR-defective mouse cells, most hprt mutations are −G frameshifts in a G6 sequence. The same G6 sequence is a target in MMR-defective human cells, but in this case, mutations are overwhelmingly +G. Our data indicate that changes in oxidized purine dNTP levels have a more profound influence on −1-base alterations than on +1-base changes. The effect on mutation rates in MMR-defective cells of deranged oxidative metabolism and changes in steady-state oxidized purine dNTPs will therefore depend on the particular genetic target. We note that our data indicate the involvement of oxidized dNTPs in MSI at mononucleotides. Their influence on dinucleotide repeats remains undefined.

The oxidized dNTP that influences frameshifts in BAT26 remains unidentified. The different behaviors of BAT26 and BAT25 are, however, consistent with some of the known properties of 2-oxodATP. 2-OxoA in a double-stranded vector replicated in COS-7 cells induces −A deletions. Importantly, this effect was extremely dependent on both the sequence context of the modified purine and the orientation of its replication. More frameshifts were introduced by lagging-strand 2-oxoA (28). Effects on lagging-strand replication offer a plausible explanation for our finding that oxidized purine dNTPs favor the production of −1-base deletions and may contribute to the qualitative difference between mouse (predominantly −1 changes) and human (predominantly +1 changes) HPRT frameshifts (Fig. 5). In human cells, an origin of replication is located in the first intron of HPRT (13) and the G6 sequence is replicated by the lagging-strand DNA polymerase. In the mouse, the origin and direction of replication of the G6 tract in the third exon are not known. We propose that replication of the G6 target sequence in mouse cells is in the direction opposite to that of its human counterpart. Minus frameshifts might then arise in the msh2−/− mouse cells as a consequence of slippage of the C-containing template strand caused by 8-oxoG in the lagging daughter DNA strand during replication of the C6 tract. This is consistent with the increased propensity of the lagging-strand DNA polymerase to produce frameshifts compared to the more processive leading-strand polymerases (21, 33). It is also compatible with the acknowledged tendency of mammalian DNA polymerases to produce −1 frameshifts more frequently in runs of template pyrimidines owing to the relatively poor stacking of pyrimidines compared to purines (32). In human cells, the G6 sequence is replicated by the lagging-strand DNA polymerase and +1 deletions predominate. It is possible that the direction of replication might influence the type of frameshift intermediates generated by oxidized dNTPs.

FIG. 5.

Model of frameshift formation in the hprt gene following 8-oxodGMP incorporation. In human cells, the origin of replication has been mapped in the first intron and the transcribed strand containing G6 is replicated by the lagging-strand polymerase (13). The location of the origin in mouse cells is unknown. The leading and lagging strands are indicated by arrowed, dotted lines. In mouse cells, −1 frameshifts might arise via an IDL of the C-containing template strand favored by an 8-oxoG in the lagging daughter DNA strand. The inversion in the types of frameshifts in human cells (+G) could be related either to the incorporation of the oxidized purine by a leading-strand DNA polymerase or to the presence of an 8-oxoG in the template strand favoring +1 frameshifts via unstacking of the pyrimidine-containing primer strand during lagging-strand synthesis.

In summary, the oxidized purine dNTPs—both dATP and dGTP—contribute significantly to the mutator phenotype of MMR-deficient cells. Their effects are quite complex. They include the simple production of promutagenic mispairings between oxidized purines and normal bases that would usually be subject to correction by MMR. More subtly, they promote the slippage and/or misalignments that are intermediates in frameshift mutation. Their effects on frameshifts are not uniform, and reduction of oxidized dNTP levels is particularly associated with a decreased frequency of −1 deletions in repeated sequences. The extent of the mutator effect will therefore represent a complex interplay among oxidized-dNTP levels, the DNA sequence, and possibly other factors, such as the direction of replication. An important implication of these findings is that the extreme genome instability associated with loss of MMR might be prevented by antioxidant treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to M.B. from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, Ministero della Salute and the European Union.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaltonen, L. A., P. Peltomaki, F. S. Leach, P. Sistonen, L. Pylkkanen, J.-P. Mecklin, H. Jarvinen, S. M. Powell, J. Jen, S. R. Hamilton, G. M. Petersen, K. W. Kinzler, B. Vogelstein, and A. de la Chapelle. 1993. Clues to the pathogenesis of familial colorectal cancer. Science 260:812-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akiyama, M., T. Horiuchi, and M. Sekiguchi. 1987. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the mutT mutator of Escherichia coli that causes A:T to C:G transversion. Mol. Gen. Genet. 206:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrew, S. E., M. McKinnon, B. S. Cheng, A. Francis, J. Penney, A. H. Reitmair, T. W. Mak, and F. R. Jirik. 1998. Tissues of MSH2-deficient mice demonstrate hypermutability on exposure to a DNA methylating agent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1126-1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrew, S. E., A. H. Reitmair, J. Fox, L. Hsiao, A. Francis, M. McKinnon, T. W. Mak, and F. R. Jirik. 1997. Base transitions dominate the mutational spectrum of a transgenic reporter gene in MSH2 deficient mice. Oncogene 15:123-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharyya, N., A. Ganesh, G. Phear, B. Richards, A. Skandalis, and M. Meuth. 1995. Molecular analysis of mutations in mutator colorectal carcinoma cell lines. Hum. Mol. Genet. 4:2057-2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharyya, N. P., A. Skandalis, A. Ganesh, J. Groden, and M. Meuth. 1994. Mutator phenotypes in human colorectal carcinoma cell lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:6319-6323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianchini, F., S. Elmstahl, C. Martinez-Garcia, A. L. van Kappel, T. Douki, J. Cadet, H. Ohshima, E. Riboli, and R. Kaaks. 2000. Oxidative DNA damage in human lymphocytes: correlations with plasma levels of alpha-tocopherol and carotenoids. Carcinogenesis 21:321-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boland, C. R., S. N. Thibodeau, S. R. Hamilton, D. Sidransky, J. R. Eshleman, R. W. Burt, S. J. Meltzer, M. A. Rodriguez-Bigas, R. Fodde, G. N. Ranzani, and S. Srivastava. 1998. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 58:5248-5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyer, J. C., A. Umar, J. I. Risinger, J. R. Lipford, K. M., S. Yin, C. Barrett, R. D. Kolodner, and T. A. Kunkel. 1995. Microsatellite instability, mismatch repair deficiency and genetic defects in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 55:6063-6070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branch, P., G. Aquilina, M. Bignami, and P. Karran. 1993. Defective mismatch binding and a mutator phenotype in cells tolerant to DNA damage. Nature 362:652-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buermeyer, A. B., S. M. Deschenes, S. M. Baker, and R. M. Liskay. 1999. Mammalian DNA mismatch repair. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33:533-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng, K. C., D. S. Cahill, H. Kasai, S. Nishimura, and L. A. Loeb. 1992. 8-Hydroxyguanine, an abundant form of oxidative DNA damage, causes G → T and A → C substitutions. J. Biol. Chem. 267:166-172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen, S. M., B. P. Brylawski, M. Cordeiro-Stone, and D. G. Kaufman. 2002. Mapping of an origin of DNA replication near the transcriptional promoter of the human HPRT gene. J. Cell Biochem. 85:346-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colussi, C., E. Parlanti, P. Degan, G. Aquilina, D. Barnes, P. Macpherson, P. Karran, M. Crescenzi, E. Dogliotti, and M. Bignami. 2002. The mammalian mismatch repair pathway removes DNA 8-oxodGMP incorporated from the oxidized dNTP pool. Curr. Biol. 12:912-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeWeese, T. L., J. M. Shipman, N. A. Larrier, N. M. Buckley, L. R. Kidd, J. D. Groopman, R. G. Cutler, H. te Riele, and W. G. Nelson. 1998. Mouse embryonic stem cells carrying one or two defective Msh2 alleles respond abnormally to oxidative stress inflicted by low-level radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11915-11920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drake, J. W., B. Charlesworth, D. Charlesworth, and J. F. Crow. 1998. Rates of spontaneous mutation. Genetics 148:1667-1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duckett, D. R., J. T. Drummond, A. I. Murchie, Y. T. Reardon, A. Sancar, D. M. Lilley, and P. Modrich. 1996. Human MutSα recognizes damaged DNA base pairs containing O6-methylguanine, O4-methylthymine, or the cisplatin d(GpG) adduct. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:6443-6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Earley, M. C., and G. F. Crouse. 1998. The role of mismatch repair in the prevention of base pair mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15487-15491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egashira, A., K. Yamauchi, K. Yoshiyama, H. Kawate, M. Katsuki, M. Sekiguchi, K. Sugimachi, H. Maki, and T. Tsuzuki. 2002. Mutational specificity of mice defective in the MTH1 and/or the MSH2 genes. DNA Repair 1:881-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujikawa, K., H. Kamiya, H. Yakushiji, Y. Fujii, Y. Nakabeppu, and H. Kasai. 1999. The oxidized forms of dATP are substrates for the human MutT homologue, the hMTH1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274:18201-18205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gawel, D., P. Jonczyk, M. Bialoskorska, R. M. Schaaper, and I. J. Fijalkowska. 2002. Asymmetry of frameshift mutagenesis during leading- and lagging-strand replication in Escherichia coli. Mutat. Res. 501:129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glaab, W. E., J. I. Risinger, A. Umar, J. C. Barrett, T. A. Kunkel, J. C. Carrett, and K. R. Tindall. 1998. Characterization of distinct human endometrial carcinoma cell lines deficient in mismatch repair that originated from a single tumor. J. Biol. Chem. 41:26662-26669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haracska, L., S. L. Yu, R. E. Johnson, L. Prakash, and S. Prakash. 2000. Efficient and accurate replication in the presence of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine by DNA polymerase eta. Nat. Genet. 25:458-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inoue, M., H. Kamiya, K. Fujikawa, Y. Ootsuyama, N. Murata-Kamiya, T. Osaki, K. Yasumoto, and H. Kasai. 1998. Induction of chromosomal gene mutations in Escherichia coli by direct incorporation of oxidatively damaged nucleotides. New evaluation method for mutagenesis by damaged DNA precursors in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 273:11069-11074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson, A. L., R. Chen, and L. A. Loeb. 1998. Induction of microsatellite instability by oxidative DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:12468-12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiricny, J. 2000. Mediating mismatch repair. Nat. Genet. 24:6-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamiya, H., and H. Kasai. 2000. 2-Hydroxy-dATP is incorporated opposite G by Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III resulting in high mutagenicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1640-1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamiya, H., and H. Kasai. 1997. Mutations induced by 2-hydroxyadenine on a shuttle vector during leading and lagging strand syntheses in mammalian cells. Biochemistry 36:11125-11130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang, D., J. Nishida, A. Iyama, Y. Nakabeppu, M. Furuichi, T. Fujiwara, M. Sekiguchi, and K. Takeshige. 1995. Intracellular localization of 8-oxo-dGTPase in human cells, with special reference to the role of the enzyme in mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 270:14659-14665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kat, A., W. G. Thilly, W.-H. Fang, M. J. Longley, G.-M. Li, and P. Modrich. 1993. An alkylation-tolerant, mutator human cell line is deficient in strand-specific mismatch repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6424-6428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolodner, R. D., and G. T. Marsischky. 1999. Eukaryotic DNA mismatch repair. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9:89-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kunkel, T. A. 1990. Misalignment-mediated DNA synthesis errors. Biochemistry 29:8003-8011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunkel, T. A., and K. Bebenek. 2000. DNA replication fidelity. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:497-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lettieri, T., G. Marra, G. Aquilina, M. Bignami, N. E. Crompton, F. Palombo, and J. Jiricny. 1999. Effect of hMSH6 cDNA expression on the phenotype of mismatch repair-deficient colon cancer cell line HCT15. Carcinogenesis 20:373-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazurek, A., M. Berardini, and R. Fishel. 2001. Activation of human MutS homologs by 8-oxo-guanine DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 26:26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mo, J.-Y., H. Maki, and M. Sekiguchi. 1992. Hydrolytic elimination of a mutagenic nucleotide, 8-oxodGTP, by human 18-kilodalton protein: sanitization of nucleotide pool. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:11021-11025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ni, T. T., G. T. Marsischky, and R. D. Kolodner. 1999. MSH2 and MSH6 are required for removal of adenine misincorporated opposite 8-oxo-guanine in S. cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 4:439-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nunoshiba, T., T. Watanabe, Y. Nakabeppu, and K. Yamamoto. 2002. Mutagenic target for hydroxyl radicals generated in Escherichia coli mutant deficient in Mn- and Fe-superoxide dismutases and Fur, a repressor for iron-uptake systems. DNA Repair 31:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohzeki, S., A. Tachibana, K. Tatsumi, and T. Kato. 1997. Spectra of spontaneous mutations at the hprt locus in colorectal carcinoma cell lines defective in mismatch repair. Carcinogenesis 18:1127-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavlov, Y. I., D. T. Minnick, S. Izuta, and T. A. Kunkel. 1994. DNA replication fidelity with 8-oxodeoxyguanosine triphosphate. Biochemistry 33:4695-4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shibutani, S., M. Takeshita, and A. P. Grollman. 1991. Insertion of specific bases during DNA synthesis past the oxidation-damaged base 8-oxodG. Nature 349:431-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strand, M., T. A. Prolla, R. M. Liskay, and T. D. Petes. 1993. Destabilization of tracts of simple repetitive DNA in yeast by mutation affecting mismatch repair. Nature 365:274-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Umar, S., A. B. Buermeyer, J. A. Simon, D. C. Thomas, A. B. Clark, R. M. Liskay, and T. A. Kunkel. 1996. Requirement for PCNA in DNA mismatch repair at a step preceding DNA synthesis. Cell 87:65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei, K., A. B. Clark, E. Wong, M. F. Kane, D. J. Mazur, T. Parris, N. K. Kolas, R. Russell, H. Hou, Jr., B. Kneitz, G. Yang, T. A. Kunkel, R. D. Kolodner, P. E. Cohen, and W. Edelmann. 2003. Inactivation of exonuclease 1 in mice results in DNA mismatch repair defects, increased cancer susceptibility, and male and female sterility. Genes Dev. 17:603-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wijnhoven, S. W., H. J. Kool, C. T. van Oostrom, R. B. Beems, L. H. Mullenders, A. A. van Zeeland, G. T. van der Horst, H. Vrieling, and H. van Steeg. 2000. The relationship between benzo[a]pyrene-induced mutagenesis and carcinogenesis in repair-deficient Cockayne syndrome group B mice. Cancer Res. 60:5681-5687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood, M. L., M. Dizdaroglu, E. Gajewski, and J. M. Essigmann. 1990. Mechanistic studies of ionizing radiation and oxidative mutagenesis: genetic effects of a single 8-hydroxyguanine (7-hydro-8-oxoguanine) residue inserted at a unique site in a viral genome. Biochemistry 29:7024-7032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wood, M. L., A. Esteve, M. L. Morningstar, G. M. Kuziemko, and J. M. Essigmann. 1992. Genetic effects of oxidative DNA damage: comparative mutagenesis of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine and 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:6023-6032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuan, F., Y. Zhang, D. K. Rajpal, X. Wu, D. Guo, M. Wang, J. S. Taylor, and Z. Wang. 2000. Specificity of DNA lesion bypass by the yeast DNA polymerase eta. J. Biol. Chem. 275:8233-8239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, L., J. Yu, J. K. Willson, S. D. Markowitz, K. W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 2001. Short mononucleotide repeat sequence variability in mismatch repair-deficient cancers. Cancer Res. 61:3801-3805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang, S., R. Lloyd, G. Bowden, B. W. Glickman, and J. G. de Boer. 2002. Thymic lymphomas arising in Msh2 deficient mice display a large increase in mutation frequency and an altered mutational spectrum. Mutat. Res. 500:67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]