Abstract

The dual antagonist effects of the mixed-action μ-opioid partial agonist/κ-opioid antagonist buprenorphine have not been previously compared in behavioral studies, and it is unknown whether they are comparably modified by chronic exposure. To address this question, the dose-related effects of levorphanol, trans-(−)-3,4-dichloro-N-methyl-N-[2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)cyclohexyl] benzeneacetamide (U50,488), heroin, and naltrexone on food-maintained behavior in rhesus monkeys were studied after acute and chronic treatment with buprenorphine (0.3 mg/kg/day). In acute studies, the effects of levorphanol and U50,488 were determined at differing times after buprenorphine (0.003–10.0 mg/kg i.m.). Results show that buprenorphine produced similar, dose-dependent rightward shifts of the levorphanol and U50,488 dose-response curves that persisted for ≥24 h after doses larger than 0.1 mg/kg buprenorphine. During chronic treatment with buprenorphine, the effects of levorphanol, U50,488, heroin, and naltrexone were similarly determined at differing times (10 min to 48 h) after intramuscular injection. Overall, results show that buprenorphine produced comparable 3- to 10-fold rightward shifts in the U50,488 dose-response curve under both acute and chronic conditions, but that chronic buprenorphine produced larger (10- to ≥30-fold) rightward shifts in the heroin dose-effect function than observed acutely. Naltrexone decreased operant responding in buprenorphine-treated monkeys, and the position of the naltrexone dose-effect curve shifted increasingly to the left as the time after daily buprenorphine treatment increased from 10 min to 48 h. These results suggest that the μ-antagonist, but not the κ-antagonist, effects of buprenorphine are augmented during chronic treatment. In addition, the leftward shift of the naltrexone dose-effect function suggests that daily administration of 0.3 mg/kg buprenorphine is adequate to produce opioid dependence.

Introduction

Buprenorphine, long available as an analgesic, is increasingly prescribed for the management of opioid dependence. Like methadone, buprenorphine is considered an agonist-based therapy because it has agonist effects at μ-opioid receptors and produces effects that are qualitatively comparable with those of morphine, heroin, and other μ-opioid agonists (Walsh et al., 1995b). Unlike methadone, however, buprenorphine is a relatively weak partial agonist and, under some conditions, the antagonist effects of buprenorphine predominate. For example, buprenorphine antagonizes [d-Ala2, NMe-Phe4,Gly-ol5]-enkephalin-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding in guinea pig caudate (Romero et al., 1999) and, in vivo, buprenorphine antagonizes the antinociceptive and ventilatory effects of morphine and other μ-opioid agonists (Walker et al., 1995; Liguori et al., 1996). Likewise, buprenorphine dose-dependently attenuates the physiological and subjective effects of hydromorphone in human studies (Bickel et al., 1988). On the other hand, antagonist-like effects of buprenorphine are evident in its ability to precipitate signs of opioid withdrawal in morphine-maintained monkeys (Woods and Gmerek, 1985) or methadone-maintained human subjects (Strain et al., 1995; Walsh et al., 1995a). The mixed agonist and antagonist actions of buprenorphine at μ-opioid receptors probably contribute to its relatively weak abuse and dependence liabilities, making it an attractive pharmacotherapy for opioid addiction.

The use of buprenorphine, as an analgesic for the relief of chronic pain or as a treatment for opioid addiction, has grown in recent years (Knudsen et al., 2009; Pergolizzi et al., 2009). It is surprising that, despite this increased use, the effects of chronically administered buprenorphine remain incompletely characterized. For example, the relatively low efficacy of buprenorphine has raised questions about whether or not it is able to produce opioid dependence, and the results of previous studies addressing the dependence liability of buprenorphine have yielded mixed results. Signs of opioid dependence have been reported in infants born to buprenorphine-maintained mothers and, as well, buprenorphine has been reported to maintain opioid dependence in human subjects that already were opioid-dependent (Eissenberg et al., 1996; Kayemba-Kay's and Laclyde, 2003). However, daily injections of buprenorphine given to drug-naive rhesus monkeys did not produce opioid dependence that could be characterized by either spontaneous or antagonist-precipitated withdrawal as assessed by changes in observed behavior (Cowan et al., 1974; Woods and Gmerek, 1985; Walker and Young, 2001).

Though generally characterized as a mixed agonist and antagonist at μ-opioid receptors, buprenorphine also has high affinity for κ-opioid receptors. Binding studies in Chinese hamster ovary cells transfected with opioid receptors and in cell membranes prepared from guinea pig caudate have revealed similar Ki values of buprenorphine at μ- and κ-opioid receptors (Romero et al., 1999; Huang et al., 2001). Unlike its mixed actions at μ-opioid receptor, buprenorphine acts only as an antagonist at κ-opioid receptors, both in vitro and in vivo (Leander, 1987, 1988; Romero et al., 1999; Huang et al., 2001). However, little attention has focused on the κ-opioid antagonist effects of buprenorphine and the question of how its κ-opioid actions might be altered during chronic treatment with buprenorphine has received still less attention.

The present studies were conducted to further evaluate the effects of chronically administered buprenorphine in nonhuman primates. Initially, the antagonist effects of acutely administered buprenorphine were determined when given in combination with μ- and κ-opioid agonists. Subsequently, the effects of μ- and κ-opioid agonists, as well as naltrexone, were studied in monkeys receiving daily injections of an effective antagonist dose of buprenorphine (0.32 mg/kg). Results indicate that acute injections of buprenorphine antagonized the response rate-decreasing effects of the μ-opioid agonist levorphanol and the κ-opioid agonist trans-(−)-3,4-dichloro-N-methyl-N-[2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)cyclohexyl]benzeneacetamide (U50,488). Daily treatment with 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine continued to antagonize the response rate-decreasing effects of levorphanol and U50,488 and produced an even greater antagonism of the response rate-decreasing effects of heroin. In addition, naltrexone had profound response rate-decreasing effects during the course of daily buprenorphine treatment. Overall, these results suggest that daily buprenorphine treatment is able to produce both μ-opioid receptor tolerance and opioid dependence in rhesus monkeys.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

Seven adult male and female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) weighing 5.0 to 6.9 kg, were studied in daily experimental sessions (5–7 days/week). The animals were individually housed, received a nutritionally balanced diet of monkey chow (High Protein Diet; Purina Mills, Framingham, MA) supplemented daily with fresh fruit, and had unlimited access to water. Monkeys could earn up to 90 g of food during experimental sessions and, in addition, received 70 to 98 g of food (10–14 chows) in their home cages after experimental sessions. Animal maintenance and research were conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the National Institutes of Health Committee on Laboratory Animal Resources (1996), and protocols were approved by the McLean Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Apparatus.

During experimental sessions, monkeys were seated in Plexiglas chairs within ventilated, sound-attenuating chambers. A single response lever was mounted on a panel that fastened to the front of the chair. Each press of the lever with a force of at least 0.25 N (lever press) produced an audible click of a relay and was recorded as a response. Colored lamps mounted above the levers could be illuminated and served as visual stimuli. A motor-driven feeder outside the chamber delivered food pellets via a connecting tube to an easily accessed food receptacle.

Schedule.

Monkeys were trained to lever-press under a schedule of food presentation in the presence of red stimulus lights, every 30th lever press (FR30) resulted in delivery of a 1-g banana-flavored food pellet. Each food pellet delivery was accompanied by a brief (200 ms) offset of visual stimuli. The daily session comprised five components, and each component consisted of a 10-min timeout period followed by a 3-min response period during which the FR30 schedule was in effect.

Plasma Analysis.

Monkeys received intramuscular injections of 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine in the home cage and were seated in Plexiglas chairs 0.5, 23.5, or 47.5 h later. One to two milliliters of blood was withdrawn from the leg vein directly into a heparin-coated tube. Plasma was separated and frozen at −70°C until analyzed. Sample analysis was performed at the Center for Human Toxicology at the University of Utah (Salt Lake City, UT), using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry with a 0.1 ng/ml lower limit of quantitation of analyte (Moody et al., 2002).

Drugs and Dosing Procedures.

Heroin, buprenorphine, and levorphanol were obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Rockville, MD); naltrexone was purchased from Sigma/RBI (Natick, MA), and U50,488 was obtained from Pfizer Inc. (Kalamazoo, MI). Heroin, levorphanol, naltrexone, and U50,488 were dissolved in saline; buprenorphine was dissolved in sterile water. Drugs were injected intramuscularly in volumes of 0.1 to 0.3 ml/kg; drug doses are expressed in terms of the weight of the free base. Test sessions were conducted once or twice per week; training sessions were conducted on intervening days. The acute effects of individual drugs were studied using cumulative dosing procedures: doses of a drug were administered 10 min before the start of successive response periods, and the total dose increased by 0.25 or 0.5 log10 unit increments throughout the session. During the chronic phase of the study, 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine was given as a single daily injection either before, during, or immediately after daily sessions.

Data Analysis.

Rates of responding were calculated by dividing the number of lever-press responses emitted during the time the stimulus lights were illuminated. Individual mean control values were calculated from response rates obtained during nondrug sessions, and rates of responding during drug sessions are expressed as a percentage of control response rates. Normalized data were used for all quantitative and statistical analysis using Prism version 5.03 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). ED50 values and 95% confidence limits (CL) were calculated by linear regression when more than two data points were available and otherwise were calculated by interpolation. In one instance, an ED50 value was calculated by extrapolation from a linear line based on three points above 50% (noted in Table 1). Individual dose ratio values were calculated from the log-transformed ED50 values and were averaged to obtain group means and S.E.M. Effects of drugs on response rates and differences in ED50 values were compared using one-way repeated measures analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett's method of multiple comparison procedures; significance was set at p < 0.05. Apparent pA2 values for individual data were calculated by Schild analysis. One monkey in the chronic buprenorphine group did not complete all studies; data from this monkey are not included in any quantitative analysis.

TABLE 1.

Dose-ratios for levorphanol and U50,488 baseline ED50 values divided by ED50 values obtained after 10-min or 24-h pretreatment with buprenorphine

| Buprenorphine (mg/kg) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 10.0 | |

| Levorphanol | ||||||||

| 10 min | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 10.0 ± 4.3 | 8.3 ± 2.8 | ||||

| 24 h | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 1.7 | 10.2 ± 3.2 | 17.8 ± 3.2 | |||

| U50,488 | ||||||||

| 10 min | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 5.2 ± 1.8 | 26.3 ± 16.3a | 27.3 ± 7.9 | ||||

| 24 h | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 1.5 | 8.1 ± 2.4 | 25.9 ± 7.8 | ||||

For one subject the postbuprenorphine ED50 value was calculated by extrapolation of a linear line based on three points above 50%.

Results

Acute Buprenorphine.

Control response rates under the schedule of food presentation averaged 4.14 ± 0.89 responses/s (range 2.90–6.01) for the three monkeys used in acute studies of buprenorphine and did not vary by more than 20% for any subject over the course of the experiments. Response rates after vehicle administration did not differ from response rates on days during which no injections were given. Buprenorphine also did not affect response rates; cumulative doses of 0.003 to 3.0 mg/kg resulted in mean response rates that ranged from 95 to 102% of control rates.

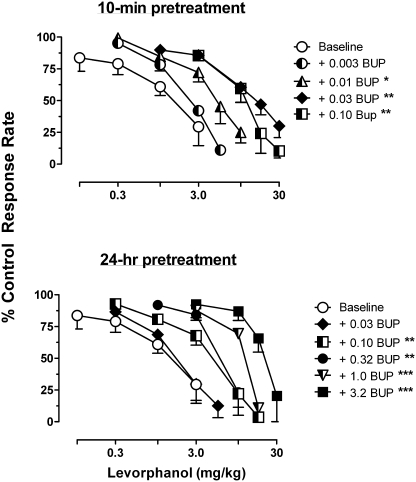

The μ-opioid agonist levorphanol decreased response rates in a dose-related manner, with a mean ED50 value (± S.E.M.) of 1.82 ± 0.55 mg/kg. As shown in Fig. 1, the effects of levorphanol were antagonized 10 min and 24 h after buprenorphine administration. After a 10-min pretreatment, 0.01 to 0.1 mg/kg buprenorphine produced statistically significant increases in levorphanol ED50 values (F4,2 = 14.13; p = 0.0011) reflected in dose-related 3- to 10-fold rightward shifts of the levorphanol dose-effect function. At 24 h after injection, the antagonist effects of buprenorphine were still orderly, although higher doses were needed to produce equivalent shifts of the levorphanol dose-effect function; changes in ED50 values were significantly different from baseline values after treatment with 0.1 to 3.0 mg/kg buprenorphine (F5,2 = 26.74; p < 0.0001).

Fig. 1.

Effects of buprenorphine (BUP) pretreatment on the response rate-decreasing effects of levorphanol. Single injections of BUP were given either 10 min (top) or 24 h (bottom) before determining the effects of levorphanol. Symbols and associated vertical lines represent the mean and S.E.M. obtained in three monkeys. Abscissae: cumulative dose of levorphanol in milligrams per kilograms of body weight. Ordinates: response rates expressed as a percentage of noninjection control response rates. Asterisks indicate that the levorphanol ED50 value in the presence of BUP was significantly different from the control ED50: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

The κ-opioid agonist U50,488 decreased response rates with a mean ED50 value of 0.48 ± 0.17 mg/kg. As shown in Fig. 2, the effects of U50,488 were antagonized at 10 min and 24 h after buprenorphine administration. After a 10-min pretreatment, 0.03 to 0.3 mg/kg buprenorphine produced dose-related 2- to 27-fold rightward shifts of the U50,488 dose-effect function, whereas after 24 h injections of higher doses of buprenorphine (1.0–10.0 mg/kg) were required to shift the U50,488 dose-effect function to the right. Changes in U50,488 ED50 values were significantly different from the baseline ED50 values at 10 min after treatment with 0.03 to 0.3 mg/kg buprenorphine (F4,2 = 43.47; p < 0.0001) and at 24 h after treatment with 1.0 to 10.0 mg/kg buprenorphine (F4,2 = 19.83; p = 0.0003).

Fig. 2.

Effects of buprenorphine pretreatment on the response rate-decreasing effects of U50,488. Abscissae: cumulative dose of U50,488 in milligrams per kilograms of body weight. Asterisks indicate that the U50,488 ED50 value in the presence of BUP was significantly different from the control ED50: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.Other details are as in Fig. 1.

The ratio of ED50 doses of levorphanol and U50,488 before and after treatment with buprenorphine are presented in Table 1. The overlap in the dose ratio values demonstrate that buprenorphine was equipotent in antagonizing the effects of levorphanol and U50,488, and this is borne out by results of Schild analysis of the data obtained at 10 min after buprenorphine injection. Schild analysis of the levorphanol dose-effect functions obtained 10 min after buprenorphine yield a slope (with 95% CL) of −0.60 (−1.10, −0.11) and an apparent pA2 value of 8.20; constraining the slope to −1 resulted in a pA2 value of 7.87. Analysis of the U50,488 dose-effect functions result in a Schild plot with a slope of −1.30 (−1.89, −0.70) and an apparent pA2 value of 7.44; constraining the slope to −1 resulted in a pA2 value of 7.59. Schild analysis of the effects of U50,488 at 24 h after buprenorphine yielded a slope 1.31 (−1.78, −0.85) and an X-intercept of 6.27 (6.40 when the slope is constrained to −1) and indicate that, relative to the dose required at 10-min, a 15-fold higher dose of buprenorphine is required to produce a 2-fold shift of the U50,488 dose-effect function [these results are not presented as a pA2 value because they probably reflect metabolism of buprenorphine over 24 h more than a decreased affinity of the receptor for buprenorphine]. Similar analysis could not be completed with the levorphanol data obtained at 24 h after injection of buprenorphine because the slope of the Schild plot, −0.60 (−0.77, −0.43) did not include −1 within its 95% CL, and imply that at 24 h after buprenorphine the interaction between levorphanol and buprenorphine is not a simple competitive interaction.

Antagonist Effects of Chronic Buprenorphine Treatment.

One monkey in the chronic buprenorphine group did not complete all studies; data from this monkey (M244) are discussed separately and are not included in quantitative analyses. For the remaining three monkeys used in studies of daily buprenorphine injections, control response rates under the FR30 schedule of food presentation averaged 2.15 ± 0.35 responses/s (range 1.73–2.84). Initial studies determined baseline dose-effect functions for levorphanol, heroin, U50,488, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. An analysis of variance of baseline ED50 values revealed that the potency of U50,488 and levorphanol did not significantly differ in the monkeys used in acute and chronic studies (F3,8 = 2.61, p = 0.12). However, in contrast to the absence of response rate-decreasing effects of buprenorphine in earlier acute studies, cumulative injections of 0.032 to 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine decreased response rates in two monkeys before chronic buprenorphine studies (Table 2). After determination of baseline dose-effect functions, a dosing regimen of 0.32 mg/kg/day buprenorphine was started; this dose of buprenorphine was selected based on the results of studies described above, as well as on previous studies, indicating that the effects of 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine in rhesus monkeys last approximately 24 h, whereas higher doses have effects that last 3 to 7 days or longer (Walker et al., 1995; Liguori et al., 1996; Kishioka et al., 2000). To minimize the influence of environmental associations on the development of tolerance, injections were given in the home cage or experimental chair before, during, or after daily training sessions on an irregular basis. This practice also allowed evaluation of the direct effects of buprenorphine immediately after injection or, alternatively, of spontaneous withdrawal that might be reflected by changes in response rates 24 h after buprenorphine. The daily dose of 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine had no effects on responding in two monkeys and initially decreased response rates in two monkeys. In the two animals in which buprenorphine decreased responding, response rates recovered to control values within 2 weeks in one monkey (M259) and within 4 weeks in the second monkey (M261). Further drug tests with a 10-min pretreatment time were not conducted in these monkeys until tolerance developed to the acute response rate-decreasing effects of buprenorphine itself.

TABLE 2.

Effects of buprenorphine on response rate before the onset of daily buprenorphine injections

Values are expressed as a percentage of control response rates.

| Subject | Buprenorphine (mg/kg) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 0.032 | 0.1 | 0.32 | 1.0 | |

| M257 | N.D. | 99.8 | 93.9 | 93.9 | 88.0 |

| M261 | N.D. | 77.1 | 28.9 | 0.0 | N.D. |

| M259 | 106.4 | 0.0 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

N.D., not determined.

Levorphanol produced response rate-decreasing effects in all monkeys before and during chronic dosing with 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine; however, there was a large amount of variation in the individual responses to levorphanol. Before the onset of the buprenorphine treatment, the mean ED50 value of levorphanol was 0.58 ± 0.40 mg/kg. At 10 min after buprenorphine injection, the levorphanol dose-effect function was shifted to the right in two of three monkeys, and dose-ratio values ranged from 1.2 to 135.5, with a mean value of 49.9 ± 42.9. At 24 h after buprenorphine, the levorphanol dose-effect function remained to the right of the baseline curve in only one monkey. These results contrast the effects of acute buprenorphine given in combination with levorphanol, in which 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine produced 3- to 8-fold shifts in all monkeys at 24 h.

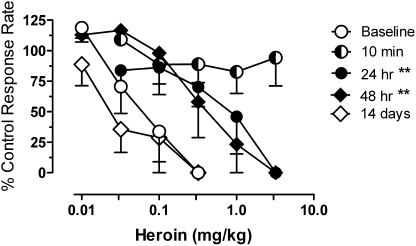

In untreated monkeys, 0.01 to 0.32 mg/kg heroin dose-dependently decreased response rates, with a mean ED50 value of 0.08 ± 0.03 mg/kg. The rate-decreasing effects of heroin were significantly attenuated in monkeys receiving 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine daily, with the position of the heroin dose-effect function dependent on the length of time after buprenorphine treatment (Fig. 3). In sessions conducted 10 min after the daily buprenorphine injection, doses of heroin up to 3.2 mg/kg had no response rate-decreasing effects. Response rate-decreasing effects of heroin emerged again at 24 and 48 h after the daily injection of buprenorphine, and the dose-effect function was shifted approximately 10-fold to the right of the baseline heroin dose-effect function at both time points. ED50 values for heroin at 24 and 48 h after buprenorphine were significantly different from baseline determinations (F3,2 = 30.73; p = 0.0005), and dose-ratio values for heroin were, respectively, 11.0 ± 1.1 and 6.9 ± 1.2 at the two time points. Redetermination of the effects of heroin 2 weeks after terminating daily injections of buprenorphine showed that the prechronic effects of heroin were fully recovered.

Fig. 3.

Effects of daily buprenorphine treatment on the response rate-decreasing effects of heroin. Heroin was injected using cumulative dosing procedures either before the onset of the daily dosing regimen (baseline) or at the indicated times after 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine. Abscissae: cumulative dose of heroin in milligrams per kilograms of body weight. Asterisks indicate that the heroin ED50 value in the presence of BUP was significantly different from the control ED50: **, p < 0.01. Other details are as in Fig. 1.

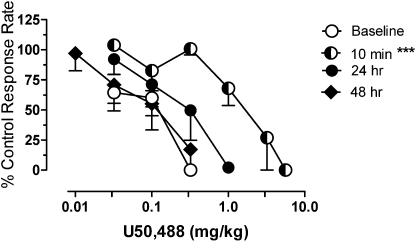

U50,488 also produced response rate-decreasing effects before, during, and after chronic dosing with 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine. Before the daily buprenorphine regimen, doses of 0.03 to 0.3 mg/kg U50,488 decreased response rates, with an ED50 value of 0.11 ± 0.03 mg/kg. In sessions conducted 10 min after injection of buprenorphine the dose-effect function for U50,488 was displaced more than 10-fold to the right of the baseline dose-effect function (Fig. 4), resulting in a significant increase in the U50,488 ED50 value (F4,2 = 16.8; p = 0.0006). The antagonism of the effects of U50,488 by buprenorphine decreased as the time interval between buprenorphine and U50,488 administration increased. At 24 h after buprenorphine, the U50,488 dose-effect function was still approximately 3-fold to the right of the baseline function, and at 48 h after 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine the baseline position of the U50,488 dose-effect function was fully recaptured. Dose-ratio analysis revealed values of 17.2 ± 3.5 at 10 min and 2.7 ± 1.3 at 24 h after buprenorphine; these data are in concordance with values after acute injections of buprenorphine (see Fig. 2 and Table 1). Thus, in most monkeys the effects of chronic buprenorphine in combination with U50,488 were similar to the effects of acute buprenorphine administration. In one monkey (M244), schedule-controlled responding was severely disrupted after determination of the U50,488 dose-response function at 10 min after buprenorphine. Efforts to re-establish stability were unsuccessful within the conditions of these studies. Consequently, further experiments in this animal were suspended and its data are not included in any analyses.

Fig. 4.

Effects of daily buprenorphine treatment on the response rate-decreasing effects of U50,488. ***, p < 0.001. Other details are as in Figs. 2 and 3.

Effects of Naltrexone During Chronic Buprenorphine Treatment.

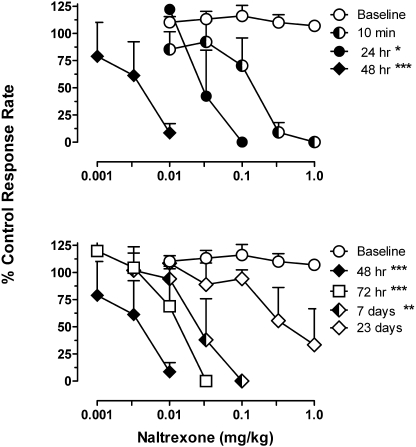

The effects of 0.001 to 1.0 mg/kg naltrexone on food-maintained responding were determined before, during, and after the regimen of daily buprenorphine dosing. As shown in Fig. 5, cumulative doses of naltrexone, up to 1.0 mg/kg, did not appreciably alter response rates before the onset of the daily buprenorphine regimen. During the course of treatment with buprenorphine, however, naltrexone dose-dependently reduced response rates with increasing potency over time. Doses of 0.32 to 1.0 mg/kg naltrexone were required to decrease response rates 10 min after treatment with buprenorphine, with an average ED50 value of 0.172 ± 0.068 mg/kg. The naltrexone dose effect function was shifted 5-fold further to the left at 24 h, with an average ED50 value of 0.034 ± 0.015 mg/kg. Naltrexone was most potent 48 h after buprenorphine: the average ED50 value was 0.005 ± 0.001 mg/kg, or 44-fold less than the value obtained from the dose-effect function determined 10 min after buprenorphine. At 72 h after buprenorphine, there was a slight recovery (ED50 value 0.013 ± 0.004), and 7 days after stopping the daily buprenorphine treatment the effects of naltrexone were similar to those obtained at 24 h after buprenorphine, with an ED50 of 0.030 ± 0.015 mg/kg (Fig. 5, bottom). The lack of effect of naltrexone under baseline conditions prevents a comparison of ED50 values relative to baseline; however, comparison of naltrexone ED50 values generated at different times after buprenorphine reveals that naltrexone ED50 values at 24 h to 7 days after buprenorphine were all statistically different from the ED50 value calculated at 10 min after buprenorphine (F4,2 = 21.84;p = 0.0002). Naltrexone continued to have some effects in two of three monkeys up to 23 days after stopping daily buprenorphine injections. Notwithstanding long-term daily treatment (106 ± 7 days), no overt signs of a spontaneous withdrawal syndrome were apparent upon cessation of the daily buprenorphine injection regimen.

Fig. 5.

Effects of daily buprenorphine treatment on the response rate-decreasing effects of naltrexone. Top, increase potency of naltrexone as time after buprenorphine increases from 10 min to 48 h is shown. Bottom, recovery toward the baseline dose-effect function after termination of the daily dosing regimen is shown. Abscissae: cumulative dose of naltrexone in milligrams per kilograms of body weight; other details are as in Fig. 3. Asterisks indicate that the naltrexone ED50 value in the presence of BUP was significantly different from the ED50 value obtained at 10 min after BUP: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Plasma Buprenorphine.

Plasma concentrations of buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine in monkeys that received a single dose of buprenorphine and in monkeys treated daily with buprenorphine are given in Table 3. There were no differences in plasma buprenorphine levels between the two groups at any time point; under both conditions buprenorphine was significantly lower at 24 or 48 h than at 1 h (F2,8 = 300.1, p < 0.0001). On the other hand, plasma levels of norbuprenorphine were higher in the chronically treated monkeys than in acutely treated monkeys at 1 h after injection (F1,48 = 8.01; p = 0.047); there were no other significant differences in plasma norbuprenorphine levels between the groups, and concentrations were lower at 24 or 48 h than at 1 h (F2,8 = 27.39; p = 0.0003).

TABLE 3.

Plasma concentrations of buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine at different times after injection of 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine

| Buprenorphine |

Norbuprenorphine |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 24 h | 48 h | 1 h | 24 h | 48 h | |

| ng/ml | ||||||

| Controla | 41.90 ± 4.24 | 2.24 ± 0.57 | 0.98 ± 0.31 | 0.24 ± 0.03 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Chronicb | 40.54 ± 0.58 | 5.51 ± 1.13 | 2.55 ± 0.50 | 0.43 ± 0.08 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.00 |

Values are mean ± S.E.M. for a group of three nondependent monkeys.

Values are mean ± S.E.M, for monkeys that received 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine daily.

Discussion

In studies of its acute effects, buprenorphine antagonized the response rate-decreasing effects of both levorphanol and U50,488 at 10 min and 24 h. Previous studies have documented the ability of buprenorphine to antagonize the effects of, separately, μ- or κ-opioid agonists (Leander, 1988; Walker et al., 1995; Liguori et al., 1996); the present studies extend these findings by directly comparing its μ- and κ- antagonist effects. In accordance with its similar binding affinities at μ- and κ-opioid receptors (Romero et al., 1999; Huang et al., 2001), the present results indicate that equivalent doses of buprenorphine will antagonize the behavioral effects of levorphanol and U50,488, with apparent pA2 values indicating only a 2- to 5-fold difference in the in vivo affinity of buprenorphine for μ- and κ-opioid receptors. Buprenorphine was less potent at 24 h than at 10 min after injection, and the loss of potency differed slightly across the two agonists. Thus, buprenorphine was approximately 10-fold less potent as an antagonist of levorphanol at 24 h, and was approximately 30-fold less potent as an antagonist of U50,488. These results suggest that buprenorphine may have a shorter duration of action at κ-opioid receptors than at μ-opioid receptors, although this suggestion needs to be strengthened with additional data. The relatively short duration of the κ-opioid antagonist effects of buprenorphine are especially noteworthy in view of the extremely long duration of action reported for selective κ-opioid antagonists such as norbinaltorphimine and (3R)-7-hydroxy-N-[(1S)-1-[[(3R,4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dimethyl-1-piperidinyl]methyl]-2-methylpropyl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-3-isoquinoline-carboxamide (Horan et al., 1992; Paronis et al., 1993; Carey and Bergman, 2001; Carroll et al., 2004). Overall, our results indicate that, under conditions in which its μ-opioid agonist effects are not evident, buprenorphine is a nonselective μ- and κ-opioid receptor antagonist and, at sufficient doses, has effects that can endure at least 24 h at both receptor types.

Previous studies have shown that continuous administration of nonselective opioid antagonists, such as naloxone and naltrexone, will up-regulate the number of receptors and increase the potency of μ- and κ-opioid agonists (Morris et al., 1988; Paronis and Holtzman, 1991; Sirohi et al., 2007). Similar increases in potency of a κ-agonist might be expected during chronic treatment with buprenorphine on the basis of its κ-antagonist actions; the present results provide no evidence of sensitization to the behavioral effects of U50,488 during daily treatment with 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine. It is conceivable that κ-opioid agonist effects of buprenorphine or its metabolites, which have been observed in vitro, might produce κ-opioid tolerance rather than sensitization as a consequence of daily treatment (Zhu et al., 1997; Huang et al., 2001). However, our data show no evidence of tolerance to the effects of U50,488 during daily treatment with buprenorphine. Taken together, these findings suggest that the effects of κ-opioid agonists such as U50,488 are not altered during daily buprenorphine administration.

The effects of heroin were profoundly antagonized during the daily buprenorphine regimen, as evident in the >30-fold rightward shift in its dose-effect function 10 min after injection of buprenorphine. Buprenorphine continued to attenuate the effects of heroin at 48 h after injection, a time at which the U50,488 dose-response curve had returned to its baseline position. The long-lasting rightward displacement of the heroin dose-effect function probably did not result from an increased accumulation of drug because plasma levels of buprenorphine were similar after acute or daily injection of 0.32 mg/kg buprenorphine. Moreover, based on results obtained with acutely administered buprenorphine, one might expect similar alterations in the effects of μ- and κ-opioid agonists if the increased antagonist effects of buprenorphine had resulted simply from an accumulation of drug over time. A more parsimonious explanation for the continued rightward displacement of the heroin dose-effect function is that antagonism by buprenorphine was comparable with that seen in acute studies and was augmented during the daily treatment regimen by buprenorphine-induced cross-tolerance to the rate-decreasing effects of heroin. This idea is supported by previous studies documenting tolerance to the antinociceptive or response rate-decreasing effects of buprenorphine and, as well, cross-tolerance to the behavioral effects of other μ-opioid agonists (Dykstra, 1985; Mello et al., 1985; Berthold and Moerschbaecher, 1988; Walker and Young, 2001).

Opioid tolerance is commonly accompanied by dependence, and buprenorphine's ability to produce tolerance suggests it may also induce opioid dependence. Antagonist-precipitated withdrawal is often used as an indicator of opioid dependence, because it produces physiological and behavioral effects similar to those of spontaneous withdrawal (O'Brien, 1975; Woods and Gmerek, 1985). For example, treatment with low, previously ineffective, doses of naltrexone or naloxone in morphine-maintained animals will produce somatic effects such as tremor, piloerection, and changes in gut motility and, as well, marked reductions in operant responding (Gellert and Sparber, 1977; Adams and Holtzman, 1990). In the present experiments, naltrexone did not seem to induce somatic signs in buprenorphine-maintained monkeys. However, buprenorphine-maintained monkeys were highly sensitive to the response rate-decreasing effects of naltrexone. This sensitivity to naltrexone was characterized by potency that increased with the time expired since the last previous buprenorphine injection, up to 48 h, and then decreased. Notwithstanding some variation among subjects in the recovery of baseline values, the time course of changes in naltrexone's potency after treatment with buprenorphine is highly suggestive of the type of precipitated withdrawal expected during treatment with conventional opioid agonists such as morphine (Gellert and Sparber, 1977; France and Woods, 1989; Paronis and Woods, 1997). The profound disruption of responding by low doses of naltrexone, in the absence of evidence of spontaneous withdrawal or naltrexone-precipitated somatic signs, supports the view that buprenorphine dependence may be less severe than dependence associated with other μ-opioid agonists. Nevertheless, the data obtained with heroin and naltrexone in buprenorphine-maintained monkeys suggest that, despite its low intrinsic activity, daily buprenorphine alone is sufficient to produce opioid tolerance and dependence in previously nondependent monkeys.

An unanticipated result of these studies was the observation that effects of levorphanol in buprenorphine-maintained animals, while variable, were more similar to the effects of U50,488 than to heroin insofar as baseline effects were recovered at 24 h after buprenorphine injection. Levorphanol has generally been viewed as a μ-opioid agonist although it binds κ-opioid receptors with only 10-fold lower affinity than μ-opioid receptors and can act as a high-efficacy agonist at κ-opioid receptors in transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells (Zhu et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 2004). The traditional view of levorphanol as a μ-opioid agonist may stem from its higher affinity for μ-opioid receptors or may simply reflect the fact that most assays in which the in vivo effects of levorphanol have been evaluated are especially sensitive to the effects of μ-opioid agonists, e.g., respiratory depression, rat tail flick, and morphine discrimination (Schaefer and Holtzman, 1977; Adams et al., 1990; Liguori et al., 1996). It is possible that, in the present studies, buprenorphine produced cross-tolerance to the μ-opioid effects of levorphanol, allowing κ-opioid actions to emerge.

In summary, buprenorphine was shown to be an effective μ- and κ-opioid antagonist when given acutely, with a duration of action longer than 24 h at doses of 0.3 mg/kg or higher. When administered daily, buprenorphine resulted in even greater apparent antagonism of μ-opioid agonists than when given acutely, probably reflecting the development of tolerance. Furthermore, during a period of daily buprenorphine treatment, relatively low doses of the opioid antagonist naltrexone were able to disrupt operant performance, an effect indicative of precipitated withdrawal. Despite rightward and leftward shifts in the position of the heroin and naltrexone dose-response functions, respectively, the effects of buprenorphine in antagonizing U50,488 were unchanged. These data suggest that μ-opioid antagonism by buprenorphine is accompanied by the development of tolerance and opioid dependence during chronic treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David E. Moody for analyzing plasma samples and Dr. Jill U Adams for assisting with preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Mental Health [Grant MH07658] and the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grants DA10566, DA15723 and Contract NO1DA-7-8074].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.110.173823.

- U50,488

- trans-(−)-3,4-dichloro-N-methyl-N-[2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)cyclohexyl]benzeneacetamide

- BUP

- buprenorphine

- FR30

- every 30th lever press

- CL

- confidence limits.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Paronis and Bergman.

Conducted experiments: Paronis and Bergman.

Performed data analysis: Paronis and Bergman.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Paronis and Bergman.

Other: Paronis and Bergman acquired funding for the research.

References

- Adams JU, Holtzman SG. (1990) Tolerance and dependence after continuous morphine infusion from osmotic pumps measured by operant responding in rats. Psychopharmacology 100:451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JU, Paronis CA, Holtzman SG. (1990) Assessment of relative intrinsic activity of μ-opioid analgesics in vivo by using β-funaltrexamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 255:1027–1032 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthold CW, 3rd, Moerschbaecher JM. (1988) Tolerance to the effects of buprenorphine on schedule-controlled behavior and analgesia in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 29:393–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA, Jasinski DR, Johnson RE. (1988) Buprenorphine: dose-related blockade of opioid challenge effects in opioid dependent humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 247:47–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey GJ, Bergman J. (2001) Enadoline discrimination in squirrel monkeys: effects of opioid agonists and antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 297:215–223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll I, Thomas JB, Dykstra LA, Granger AL, Allen RM, Howard JL, Pollard GT, Aceto MD, Harris LS. (2004) Pharmacological properties of JDTic: a novel κ-opioid receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol 501:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan A, Braude MC, Harris LS, May EL, Smith JP, Villarreal JE. (1974) Evaluation in nonhuman primates: Evaluation of the physical dependence capacities of oripavine-thebaine partail agonists in patas monkeys, in Narcotic Antagonists, pp 427–438, Raven Press, New York: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra LA. (1985) Effects of buprenorphine on shock titration in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 235:20–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T, Greenwald MK, Johnson RE, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. (1996) Buprenorphine's physical dependence potential: antagonist-precipitated withdrawal in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 276:449–459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France CP, Woods JH. (1989) Discriminative stimulus effects of naltrexone in morphine-treated rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 250:937–943 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellert VF, Sparber SB. (1977) A comparison of the effects of naloxone upon body weight and suppression of fixed-ratio operant behavior in morphine-dependent rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 201:44–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan P, Taylor J, Yamamura HI, Porreca F. (1992) Extremely long-lasting antagonist actions of nor-binaltorphimine (nor-BNI) in the mouse tail-flick test. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 260:1237–1243 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Kehner GB, Cowan A, Liu-Chen LY. (2001) Comparison of pharmacological activities of buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine: norbuprenorphine is a potent opioid agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 297:688–695 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayemba-Kay's S, Laclyde JP. (2003) Buprenorphine withdrawal syndrome in newborns: a report of 13 cases. Addiction 98:1599–1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishioka S, Paronis CA, Lewis JW, Woods JH. (2000) Buprenorphine and methoclocinnamox: agonist and antagonist effects on respiratory function in rhesus monkeys. Eur J Pharmacol 391:289–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ, Johnson JA, Roman PM. (2009) Buprenorphine adoption in the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. J Subst Abuse Treat 37:307–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leander JD. (1987) Buprenorphine has potent κ opioid antagonist activity. Neuropharmacology 26:1445–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leander JD. (1988) Buprenorphine is a potent κ-opioid receptor antagonist in pigeons and mice. Eur J Pharmacol 151:457–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liguori A, Morse WH, Bergman J. (1996) Respiratory effects of opioid full and partial agonists in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 277:462–472 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Bree MP, Lukas SE, Mendelson JH. (1985) Buprenorphine effects on food-maintained responding in Macaque monkeys. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 23:1037–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody DE, Slawson MH, Strain EC, Laycock JD, Spanbauer AC, Foltz RL. (2002) A liquid chromatographic-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometric method for determination of buprenorphine, its metabolite, norbuprenorphine, and a coformulant, naloxone, that is suitable for in vivo and in vitro metabolism studies. Anal Biochem 306:31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris BJ, Millan MJ, Herz A. (1988) Antagonist-induced opioid receptor up-regulation. II. Regionally specific modulation of μ, δ, and κ binding sites in rat brain revealed by quantitative autoradiography. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 247:729–736 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP. (1975) Experimental analysis of conditioning factors in human narcotic addiction. Pharmacol Rev 27:533–543 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paronis CA, Holtzman SG. (1991) Increased analgesic potency of μ agonists after continuous naloxone infusion in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 259:582–589 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paronis CA, Woods JH. (1997) Ventilation in morphine-maintained rhesus monkeys. I: Effects of naltrexone and abstinence-associated withdrawal. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 282:348–354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paronis CA, Waddell AB, Holtzman SG. (1993) Naltrexone in vivo protects μ receptors from inactivation by β-funaltrexamine but not κ-receptors from inactivation by nor-binaltorphimine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 46:813–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergolizzi JV, Jr, Mercadante S, Echaburu AV, Van den Eynden B, Fragoso RM, Mordarski S, Lybaert W, Beniak J, Orońska A, Slama O, et al. (2009) The role of transdermal buprenorphine in the treatment of cancer pain: an expert panel consensus. Curr Med Res Opin 25:1517–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero DV, Partilla JS, Zheng QX, Heyliger SO, Ni Q, Rice KC, Lai J, Rothman RB. (1999) Opioid peptide receptor studies. 12. Buprenorphine is a potent and selective μ/κ antagonist in the [35S]-GTP-γ-S functional binding assay. Synapse 34:83–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer GJ, Holzman SG. (1977) Discriminative effects of morphine in the squirrel monkey. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 201:67–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirohi S, Kumar P, Yoburn BC. (2007) μ-Opioid receptor up-regulation and functional supersensitivity are independent of antagonist efficacy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323:701–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strain EC, Preston KL, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE. (1995) Buprenorphine effects in methadone-maintained volunteers: effects at two hours after methadone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 272:628–638 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Young AM. (2001) Differential tolerance to antinociceptive effects of μ-opioids during repeated treatment with etonitazene, morphine, or buprenorphine in rats. Psychopharmacology 154:131–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Zernig G, Woods JH. (1995) Buprenorphine antagonism of μ opioids in the rhesus monkey tail-withdrawal procedure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 273:1345–1352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, June HL, Schuh KJ, Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. (1995a) Effects of buprenorphine and methadone in methadone-maintained subjects. Psychopharmacology 119:268–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. (1995b) Acute administration of buprenorphine in humans: partial agonist and blockade effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 274:361–372 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods JH, Gmerek DE. (1985) Substitution and primary dependence studies in animals. Drug Alcohol Depend 14:233–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A, Xiong W, Hilbert JE, DeVita EK, Bidlack JM, Neumeyer JL. (2004) 2-Aminothiazole-derived opioids. Biosteric replacement of phenols. J Med Chem 47:1886–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Luo LY, Li JG, Chen C, Liu-Chen LY. (1997) Activation of the cloned human κ opioid receptor by agonists enhances [35S]GTPγS binding to membranes: determination of potencies and efficacies of ligands. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 282:676–684 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]