Abstract

Group B streptococcus (GBS) strains with the highest ability to bind to human fibrinogen belong to the highly invasive clonal complex (CC) 17. To investigate the fibrinogen-binding mechanisms of CC17 strains, we determined the prevalence of fibrinogen-binding genes (fbsA and fbsB), and fbs regulator genes (rogB encoding an fbsA activator, rovS encoding an fbsA repressor and rgf encoding a two-component system [TCS] whose role on fbs genes was not determined yet) in a collection of 134 strains representing the major CCs of the species. We showed that specific gene combinations were related to particular CCs; only CC17 strains contained the fbsA, fbsB, and rgf genes combination. Non polar rgfAC deletion mutants of three CC17 serotype III strains were constructed. They showed a 3.2- to 5.1-fold increase of fbsA transcripts, a 4.8- to 6.7-fold decrease of fbsB transcripts, and a 52% to 68% decreased fibrinogen-binding ability, demonstrating that the RgfA/RgfC TCS inhibits the fbsA gene and activates the fbsB gene. The relative contribution of the two fbs genes in fibrinogen-binding ability was determined by constructing isogenic fbsA, fbsB, deletion mutants of the three CC17 strains. The ability to bind to fibrinogen was reduced by 49% to 57% in ΔfbsA mutants, and by 78% to 80% in ΔfbsB mutants, suggesting that FbsB protein plays a greater role in the fibrinogen-binding ability of CC17 strains. Moreover, the relative transcription level of fbsB gene was 9.2- to 12.7-fold higher than that of fbsA gene for the three wild type strains. Fibrinogen-binding ability could be restored by plasmid-mediated expression of rgfAC, fbsA, and fbsB genes in the corresponding deletion mutants. Thus, our results demonstrate that a specific combination of fbs genes and fbs regulator genes account for the high fibrinogen-binding ability of CC17 strains that may participate to their enhanced invasiveness for neonates as compared to strains of other CCs.

Introduction

Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus [GBS]) frequently asymptomatically colonizes the intestinal and/or urogenital tract of humans. It is the leading cause of invasive infections in neonates and has emerged as an increasingly cause of invasive diseases in immunocompromised and elderly adults [1], [2]. Several studies have emphasized the clonal structure of GBS species and demonstrated that GBS diseases are mostly caused by a limited set of clonal lineages [3]–[8]. Indeed, strains belonging to clonal complex (CC) 17 appear to be strongly able to invade the central nervous system (CNS) of neonates [9]–[13]. The remarkable homogeneity within this highly virulent lineage is likely of importance for disease pathogenesis, though few studies have been conducted to identify specific differences in virulence characteristics between lineages.

Various molecules either secreted or located at the bacterial surface account for the pathogenicity of GBS strains [14]–[17]. Among these molecules, FbsA and FbsB are proteins with no structural homology which both bind to human fibrinogen, mediate the bacterial adhesion to or invasion of epithelial and endothelial cells, and contribute to the bacterial escape from the immune system [18]–[22]. Deletion of the fbsB gene that has been described for a unique strain belonging to CC23 phylogenetic lineage, did not attenuate its fibrinogen-binding ability; conversely, deletion of the fbsA gene in this strain resulted in a loss of fibrinogen-binding activity, thus suggesting that FbsA protein was the major fibrinogen-binding protein in GBS [18], [20], [21]. However, while studying a collection of 111 human strains, we showed that the presence of the sole fbsA gene was not sufficient to result in strong binding ability to fibrinogen [17]. Indeed, the population of strains with the significantly highest ability to bind to fibrinogen had both the fbsB and fbsA genes and belonged to CC17 phylogenetic lineage [17]. Thus, the role of fbs genes and in particular the fbsB gene in the fibrinogen-binding ability of CC17 strains remains unclear and requires further investigation.

Two transcriptional regulators were shown to control the fbsA gene transcription in a CC23 GBS strain: RogB, a member of the RALP (RofA-like proteins) family, exerts a positive effect [23], and RovS, relative to the Rgg family of Gram-positive transcriptional regulators, exerts a negative effect [24]. In addition, Spellerberg et al. described a two-component system (TCS), the regulator of fibrinogen-binding rgfBDAC operon that principally encodes the response regulator RgfA and the histidine kinase RgfC [25]. Disruption of the rgfC gene altered the bacterial binding to fibrinogen. The role of rgf locus on fbs genes transcription was not studied yet, and it can be speculated that fbsA and/or fbsB genes are under the transcriptional control of the RgfA/RgfC TCS.

To investigate the mechanisms allowing the high fibrinogen-binding ability of CC17 strains (i) we determined the fbs genes and fbs regulator genes profile of 38 CC17 strains as compared to 96 GBS strains of the other four major phylogenetic lineages constituting this species, and found that specific gene combinations were related to particular CCs; (ii) we constructed non polar rgfAC deletion mutants of three CC17 strains in order to determine the role of rgf locus on fbs genes transcription; (iii) we quantified the transcription levels of fbsA and fbsB genes of these three strains, and constructed their fbsA and fbsB deletion mutants in order to determine the relative contribution of fbs genes in the fibrinogen-binding ability of CC17 strains.

Results

Prevalence of the fbs genes and of the fbs regulator genes in strains of CC17 and of the major other GBS clonal complexes

PCR was performed to characterize the presence of fbs genes (fbsA and fbsB) and their regulator genes (rogB, rovS and rgf) in a collection of 134 isolates representing the major clonal complexes of GBS species: CC1 (29 strains), CC10 (26 strains), CC17 (38 strains), CC19 (21 strains), and CC23 (20 strains) (Table 1). The fbsA gene was found in all CC17 and CC23 strains, in most strains of CC10 (92.3%) and CC1 (82.8%), and in only 23.8% of CC19 strains. The fbsB gene was found in all CC17 strains, in 75.0% of CC23 strains, and in only one CC19 strain (4.8%), whereas the CC1 and CC10 strains did not have an fbsB gene. The rovS gene was found in all strains of all the CCs. The rogB gene was found in all CC1, CC10, CC19 and CC23 strains and in only 21.0% of CC17 strains. The rgf locus was found in all CC17 and CC10 strains, in most CC1 strains (93.1%), and rarely in CC19 (14.3%) and CC23 (25.0%) strains. Thus, CC1 and CC10 strains shared the same profile containing the various fbs regulator genes and the fbsA gene, but not the fbsB gene. Most of CC19 strains lacked the fbsA and fbsB genes. The simultaneous presence of fbsA and fbsB genes was restricted to CC17 (100%) and CC23 (75%) strains. However, the regulator genes profile of these two groups of strains differed, since rgf locus and rogB gene were associated with CC17 and CC23, respectively. These data show that different fbs genes and fbs regulator genes profiles are related to the GBS phylogenetic lineages, and that CC17 strains have a unique configuration characterized by the fbsA, fbsB, rovS,and rgf genes combination and the absence of rogB gene.

Table 1. Prevalence of the fbs genes and of their regulator genes in a collection of 134 isolates belonging to the GBS major clonal complexes.

| Clonal complexes (CC) | |||||

| CC17 | CC19 | CC23 | CC1 | CC10 | |

| N° (%) | N° (%) | N° (%) | N° (%) | N° (%) | |

| n = 38 | n = 21 | n = 20 | n = 29 | n = 26 | |

| fbsA | 38 (100.0) | 5 (23.8) | 20 (100.0) | 24 (82.8) | 24 (92.3) |

| fbsB | 38 (100.0) | 1(4.8) | 15 (75.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| rovS | 38 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) | 20 (100.0) | 29 (100.0) | 26 (100.0) |

| rogB | 8 (21.0) | 21 (100.0) | 20 (100.0) | 29 (100.0) | 26 (100.0) |

| rgf | 38 (100.0) | 3 (14.3) | 5 (25.0) | 27 (93.1) | 26 (100.0) |

Expression of fbsA and fbsB genes in three non polar deletion ΔrgfAC mutant strains

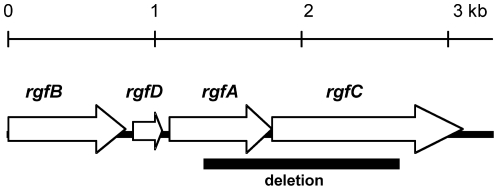

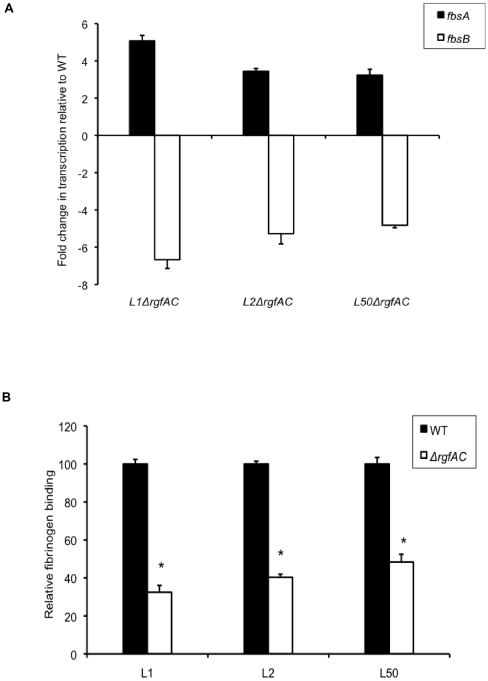

As the fbsA, fbsB and rgf genes combination was strictly restricted to the CC17 strains and that the role of the RgfA/RgfC TCS on the fbsB and fbsA genes expression was not explored yet, we constructed non polar deletion ΔrgfAC mutants of serotype III strains belonging to CC17 phylogenetic lineage. Since phenotypes can be strain specific despite genetic similarity, we constructed mutants of three epidemiologically unrelated isolates, L1, L2 and L50 strains that were isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of neonates suffering from meningitis. In these mutants, the last 374 bp of rgfA gene encoding the DNA-binding domains, as well as the first 1,055 bp of the 1,278-bp rgfC gene were deleted (Fig. 1). By quantifying the transcription level of downstream gene, we checked that these mutations were non polar. Real time RT-PCR was then used to quantify the transcription levels of fbsA and fbsB genes in the three ΔrgfAC mutant strains and in the parental strains (Fig. 2A). As compared to L1, L2, and L50 wild type strains, the transcription levels of the fbsB gene were respectively 6.67±0.47-, 5.28±0.54-, and 4.82±0.14-fold decreased in ΔrgfAC mutants. By contrast, the transcription levels of the fbsA gene were respectively 5.07±0.30-, 3.45±0.05-, and 3.24±0.32-fold increased in ΔrgfAC mutant strains as compared to the wild type strains. These results indicate that RgfA/RgfC exerts a negative effect on the transcription of the fbsA gene, and that it activates the transcription of the fbsB gene in CC17 isolates.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the rgf locus.

Open reading frames, direction of transcription and approximate gene sizes are indicated [25]. The segment that was deleted in ΔrgfAC mutant is represented as a heavy line below the genes.

Figure 2. Properties of ΔrgfAC mutant strains.

(A) Fold change in transcription levels of fbsA (filled boxes) and fbsB (open boxes) genes in the isogenic ΔrgfAC mutants as compared to the wild type L1, L2, and L50 strains (WT). The amount of transcripts of each gene was normalized to the amount of gyrA transcripts and expressed relative to the level of transcription in corresponding WT strain. Each experiment was performed at least three times. Boxes are means and bars are standard deviation of the means. (B) Binding ability to immobilized human fibrinogen of the isogenic ΔrgfAC mutants (open boxes) and the WT strains (filled boxes). Flat bottomed 96-well polystyrene plates were coated with 21 nM human fibrinogen and 5×106 to 5×108 CFU per ml were added for 90 min at 37°C. Binding ability was calculated from the ratio between the number of bound bacteria and the number of bacteria present in the inoculum. The level of fibrinogen binding of WT strains is arbitrarily reported as 100 and the fibrinogen-binding levels of the isogenic mutants are relative values. Each experiment was performed at least three times. Boxes are means and bars are standard deviation of the means. * indicates that the binding values of the mutant strains were significantly lower than the values of the corresponding WT strains, at a P value of <0.001.

To investigate whether RgfA/RgfC regulated fbs genes through the rovS gene that encodes an fbsA inhibitor, we quantified the rovS gene transcription levels in L1 ΔrgfAC mutant as compared to the parental strain, and found no significant difference (1.29±0.11-fold that of the wild type strain).

Binding of the three ΔrgfAC mutant strains to immobilized human fibrinogen

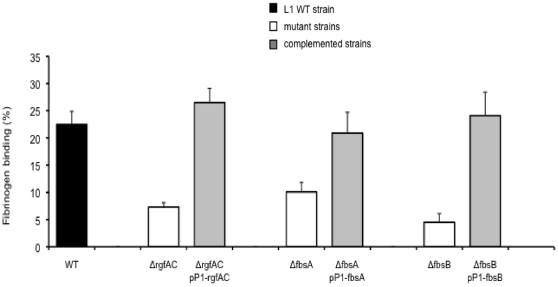

To further characterize the three ΔrgfAC mutant strains, we compared their fibrinogen-binding ability with that of the wild type L1, L2 and L50 strains. The percentage of bacteria that bound to fibrinogen was respectively 22.5% ±2.4%, 25.3% ±1.4%, and 23.2% ±3.4% for the three wild type strains, and 7.3% ±0.8%, 10.2% ±1.6%, and 11.2% ±1.1% for the isogenic ΔrgfAC mutants. Thus, as depicted in Fig. 2B, the three ΔrgfAC mutants showed respectively a 68%, 60%, and 52% decreased fibrinogen-binding ability as compared to L1, L2, and L50 wild type strains (P<0.001). Furthermore, plasmid-mediated expression of rgfAC in L1ΔrgfAC mutant strain restored its fibrinogen-binding ability to the wild-type level. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 3, the fibrinogen-binding ability of the complemented strain L1ΔrgfAC/pP1-rgfAC (26.5% ±2.6%) was significantly higher (P<0.001) than that of L1ΔrgfAC mutant (7.3% ±0.8%) and was similar to that of the wild type L1 strain (22.5% ±2.4%).

Figure 3. Binding ability to immobilized human fibrinogen of the wild type (WT) L1 strain, and of isogenic mutant and complemented strains for rgfAC, fbsA, and fbsB genes.

Flat bottomed 96-well polystyrene plates were coated with 21 nM human fibrinogen and 5×106 to 5×108 CFU per ml were added for 90 min at 37°C. Binding ability was calculated from the ratio between the number of bound bacteria and the number of bacteria present in the inoculum. Each experiment was performed at least three times. Boxes are means and bars are standard deviation of the means. The binding values of the mutant strains were significantly lower, at a P value of <0.001, than the values of the L1WT strain and of the corresponding complemented strains carrying rgfAC, fbsA, and fbsB genes on the pP1 plasmid.

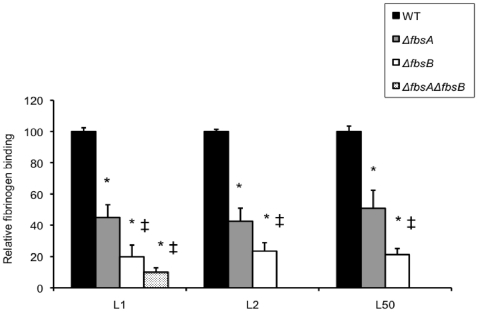

Binding of ΔfbsA, ΔfbsB, and ΔfbsAΔfbsB mutant strains to immobilized human fibrinogen

In order to investigate the relative contribution of FbsA and FbsB proteins in the interaction of GBS CC17 strains with human fibrinogen, fbsA and fbsB genes were deleted in the genome of L1, L2 and L50 strains, and both genes were deleted in the genome of L1 strain. The growth curves of the mutants and of the wild type parental strains in TH broth did not differ significantly. The wild type strains and their isogenic mutants (ΔfbsA, ΔfbsB, and ΔfbsAΔfbsB) were subsequently tested for their fibrinogen-binding ability. For L1 strain, the percentage of bacteria that bound to fibrinogen was 22.5% ±2.4% for wild type strain, 10.1% ±1.7% for ΔfbsA, 4.5% ±1.6% for ΔfbsB, and 2.2% ±0.7% for ΔfbsAΔfbsB. Thus, as shown in Fig. 4, deletion of fbsA gene reduced the fibrinogen-binding ability of L1 wild type strain by 55% (P<0.001), whereas deletion of fbsB gene resulted in a 80% decrease (P<0.001), and deletion of both fbsA and fbsB genes resulted in a 90% decrease of this ability (P<0.001). Similar results were obtained with ΔfbsA and ΔfbsB mutants of L2 and L50 strains (Fig. 4). Moreover, the fibrinogen-binding abilities of ΔfbsB and of ΔfbsAΔfbsB mutant strains were significantly lower than those of ΔfbsA mutant strains (P<0.001). In addition, plasmid-mediated expression of fbsA and of fbsB in L1ΔfbsA and in L1ΔfbsB mutants, respectively, restored their fibrinogen-binding ability to the wild-type level. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 3, the fibrinogen-binding ability of the complemented strains L1ΔfbsA/pP1-fbsA (20.9% ±3.8%) and L1ΔfbsB/pP1-fbsB (24.1% ±4.3%) were significantly higher (P<0.001) than those of L1ΔfbsA (10.1% ±1.7%) and L1ΔfbsB (4.5% ±1.6%) mutants and were similar to that of the wild type L1 strain (22.5% ±2.4%). Taken together, these data suggest a greater role of the fibrinogen-binding protein FbsB as compared to FbsA in the binding ability to human fibrinogen of CC17 GBS strains.

Figure 4. Binding ability to immobilized human fibrinogen of the wild type (WT) S. agalactiae strains and isogenic ΔfbsA, ΔfbsB, ΔfbsAΔfbsB deletion mutants.

Flat bottomed 96-well polystyrene plates were coated with 21 nM human fibrinogen and 5×106 to 5×108 CFU per ml were added for 90 min at 37°C. Binding ability was calculated from the ratio between the number of bound bacteria and the number of bacteria present in the inoculum. The fibrinogen-binding level of WT L1, L2, and L50 strains is arbitrarily reported as 100 and the fibrinogen-binding levels of the various isogenic mutants are relative values. Each experiment was performed at least three times. Boxes are means and bars are standard deviation of the means. * indicates that the binding values of the mutant strains were significantly lower than the values of the corresponding WT strains, at a P value of <0.001. ‡ indicates that the binding values of the ΔfbsB and ΔfbsAΔfbsB mutant strains were significantly lower than the values of ΔfbsA mutant strains, at a P value of <0.001.

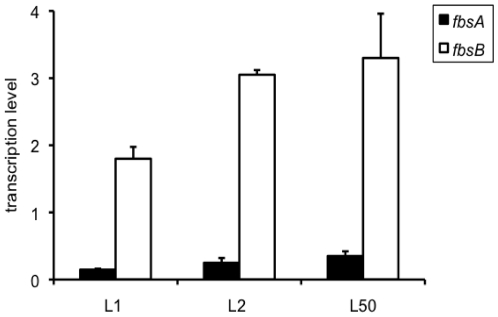

Relative transcription level of fbsA and fbsB genes

In order to determine if the greater role of FbsB as compared to FbsA in the binding ability to fibrinogen of CC17 strains was related to a higher transcription of fbsB, we quantified fbsA and fbsB gene transcripts by real-time PCR in the three wild type strains L1, L2 and L50. As shown in Fig. 5, the relative transcription level of fbsB gene was respectively 12.24±2.38-, 12.67±3.30- and 9.17±2.19-fold higher than that of fbsA gene for the three strains.

Figure 5. Transcription levels of fbsA and fbsB genes in three wild type CC17 strains.

The amount of transcripts of fbsA gene (filled boxes) and fbsB gene (open boxes) in L1, L2, and L50 wild type strains was normalized to the amount of gyrA transcripts. Each experiment was performed at least three times. Boxes are means and bars are standard deviation of the means.

Quantification of fbsA and fbsB gene transcripts in mutant strains

By real-time PCR, we quantified the transcript levels of fbsA and fbsB genes in ΔfbsA, ΔfbsB, and ΔfbsAΔfbsB mutants and in the parental strain L1. As expected, no fbsA transcripts were detected in ΔfbsA and in ΔfbsAΔfbsB mutants; likewise, no fbsB transcripts were detected in ΔfbsB and ΔfbsAΔfbsB mutants. Deletion of fbsA gene had no significant effect on the fbsB gene transcription, since in ΔfbsA mutant, the transcription level of fbsB was 1.4±0.2-fold that of the wild type strain. Similarly, deletion of fbsB gene had no significant effect on the fbsA gene transcription since the transcription level of fbsA in ΔfbsB mutant was 0.96±0.03-fold that of the wild type strain. These data demonstrate that the fbsA and fbsB genes expression are independent of each other.

Discussion

Overrepresentation of CC17 clone among invasive neonatal strains is now well recognized worldwide [9]-[13], and highlights the fact that this clone is well adapted to neonate infection pathogenesis and may possess specific virulence traits that enhance CNS invasiveness in this population [14], [26]. We here studied the molecular events involved in the fibrinogen-binding ability of CC17 strains that were previously shown to bind significantly more strongly to human fibrinogen than strains of other lineages that constitute the species [17]. We first looked for the fbs genes and the fbs regulator genes in a collection of 134 GBS isolates belonging to the major GBS phylogenetic lineages. No gene was specific of either CC17 or other CCs strains, but specific gene combinations were related to particular CCs, indicating that fibrinogen binding is a multigenic process that results from various gene combinations. Only CC17 strains contained the fbsA, fbsB, and rgf genes combination. The rogB gene was rarely found in CC17 strains but present in all strains of other CCs. Accordingly, the rogB gene is missing in the sequenced genome of CC17 strain COH1 [27], and the absence of this gene was also reported in a collection of 20 CC17 strains [14]. Thus, each CC was characterized by a particular profile of fbs genes and fbs gene regulators that may account for differences in their fibrinogen-binding abilities.

As only CC17 strains contained the fbsA, fbsB, and rgf genes combination, we constructed non polar ΔrgfAC mutants of three serotype III CC17 strains that showed a 52% to 68% decreased binding ability to fibrinogen, a 4.8- to 6.7-fold decreased transcript level of fbsB gene, and at the same time a 3.2- to 5.1-fold increased transcript level of fbsA gene. These data demonstrate that RgfA/RgfC is implicated in fbsB gene activation and in fbsA gene inhibition. Spellerberg et al. have described that the response regulator RgfA and the histidine kinase RgfC display respectively 55% and 45% similarities with AgrA and AgrC of Staphylococcus aureus [25]. The accessory gene regulator (agr) locus consists of the four cotranscribed agrBDCA genes that regulate the expression of S. aureus virulence factors. In general, secreted proteins, including several of the known S. aureus toxins, are up-regulated by agr whereas surface proteins such as protein A and extracellular matrix adhesins are down-regulated [28]–[32]. Thus, our results showing the increased transcription of the fbsA gene encoding a surface protein, as well as the decreased transcription of the fbsB gene encoding a secreted protein in ΔrgfAC mutant strain, are in agreement with the control of cell surface and secreted molecules through agr locus of S. aureus. Similarly, Spellerberg et al. found that rgf locus down regulated the surface-anchored C5a peptidase scpB gene [25]. Response regulators may modify genes expression by direct binding to the genes promoters or by action on other regulators that, in turn regulate target genes expression [16], [33]–[36]. As RovS was shown to directly bind to the promoter of fbsA and hence to negatively regulate its transcription [24], we quantified rovS transcript levels in a ΔrgfAC mutant in order to determine whether RgfA/RgfC regulated fbsA through rovS gene. We found that the rovS transcription was not altered in this mutant. Thus, it is likely that RgfA/RgfC- and RovS- mediated control of fbsA are independent of each other. Finally, RgfA/RgfC appears to be an important multigene regulator in the hyper virulent CC17 lineage, and is therefore worthy of further disease association studies.

Phenotypic comparison of three CC17 wild type strains with their mutants deleted for the fbsA and fbsB genes demonstrated that FbsB protein was the major fibrinogen binding protein of these strains. Indeed, inactivation of the fbsB gene substantially reduced fibrinogen-binding ability (78 to 80%), while deletion of fbsA gene reduced only partially (49 to 57%) this ability. Our findings showing the implication of both FbsA and FbsB proteins in the fibrinogen-binding ability of CC17 strains with a major role of FbsB are in contrast with previous reports suggesting that FbsA protein was the major fibrinogen-binding protein in the CC23 serotype III 6313 GBS strain [18], [20], [21]. The reasons for these phenotype differences between isolates are not completely understood but can be related to differences in fbs genes regulation depending on the genetic background of the GBS strains. Interestingly, CC17 strains and CC23 6313 strain that both contain fbsA and fbsB genes, possess a distinct fbs regulator profile: contrarily to CC17 strains, 6313 strain has no functional rgfBDAC locus and moreover possesses rogB gene [23]. This configuration that leads to an up-regulation of the fbsA gene, is thus in agreement with the major role of FbsA in the fibrinogen-binding process of CC23 strains. On the contrary, the higher implication of FbsB as compared to FbsA in the fibrinogen-binding ability of CC17 strains may be explained by the fact that the fbsA gene expression is inhibited by two mechanisms: on one hand by the RgfA/RgfC inhibitor, and on the other hand by the absence of the RogB activator. Indeed, in the three CC17 strains studied, the mean transcription level of fbsB gene was significantly higher (11.4±1.9-fold) than that of fbsA gene. Thus, depending on the genetic background of the GBS strains, several fbs regulatory circuits may be defined and may account for the differences in the relative implication of fbs genes in GBS binding-ability to human fibrinogen.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that a specific combination of fbs genes and fbs regulator genes may account for the CC17 strains enhanced ability to bind to human fibrinogen, a host protein whose synthesis is dramatically increased during inflammation or under exposure to stress such systemic infections [37].

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

A total of 134 unrelated human strains representing the genetic diversity of S. agalactiae species were included in the present study: 52 strains from the CSF of infected neonates, 16 strains from the gastric fluid of colonized asymptomatic neonates, 26 strains from vaginal swabs of colonized asymptomatic pregnant women, and 40 strains from infected nonpregnant adult patients. Neonatal specimens were obtained from infected neonates suffering of meningitis and from non infected neonates with risk factor, and vaginal specimens were obtained from asymptomatic pregnant women during the process of routine clinical diagnostic procedures, as part of the usual prenatal and postnatal screening. All these strains were isolated between 1986 and 1990 from 25 general hospitals throughout France [7]. According to the information we obtained from the Institutional Review Board (more than 20 years ago), this type of strains did not require an ethics approval and the patient consent. Adult specimens were isolated from sites of infection (skin, osteoarticular, and blood infections) of patients admitted to hospitals in various regions of France from 2002 to 2008. The local ethical committee (CPP, Comité de Protection des Personnes, Tours-Centre) exempted the study of adult specimens from review because they were of existing diagnostic specimens, and waived the need for consent due to the fact that the samples received were analyzed anonymously.

All strains had previously been serotyped on the basis of capsular polysaccharides or by PCR [7], [38]. Six serotypes were identified i.e. serotypes Ia (19 strains), Ib (18 strains), II (17 strains), III (51 strains), IV (2 strains), and V (23 strains), and four strains were not typeable. All strains had previously been analyzed by MLST according to Jones et al. [5]. Strains were grouped into clonal complexes (CCs) that include isolates sharing five to seven identical alleles.

GBS strains were stored at −80°C in Schaedler-vitamin K3 broth (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) with 10% glycerol. The bacteria were grown for 24 h on 5% horse blood Trypticase soja (TS) agar plates (bioMérieux) at 37°C.

Escherichia coli DH5α and MC1061 were used for cloning purposes. They were grown at 37°C in Luria Broth. E. coli and GBS clones carrying the pG+host5 and pP1 plasmids were selected in the presence of 300 µg/ml and 2 µg/ml erythromycin, respectively.

Construction of S. agalactiae mutants

The thermosensitive plasmid pG+host5 [39] was used for the construction of mutants of the CC17 serotype III L1 wild type GBS strain deleted for fbsA gene, for fbsB gene, for both genes, and for rgfAC genes by a method previously described by Schubert et al. [20]. For the deletion of fbsA gene, two DNA fragments flanking the fbsA gene were amplified by PCR using the primer set fbsA_del1 (5′-CCGCGGATCCGAATATGCTACCATCAC)/fbsA_del2 (5′-CCCATCCACTAAACTTAAACA TTCCTGATTTCCAAGTTC) and the primer set fbsA_del3 (5′-TGTTTAAGTTTAGTGGATG GGGCTGCGGTTTGAGACGC)/fbsA_del4 (5′-TGGCACAAGCTTTACCTGCTGAGCGAC TTG). Complementary DNA sequences in the primers fbsA_del2 and fbsA_del3 are shown in italics, and the BamHI and HindIII restrictions sites in primers fbsA _del1 and fbsA _del4 are underlined. The fbsA-flanking PCR products were mixed in equal amounts and subjected to a crossover PCR with the primers fbsA _del1 and fbsA _del4, resulting in one PCR product that carried the two fbsA-flanking regions. The crossover PCR product and the plasmid pG+host5 were digested with BamHI and HindIII, ligated and transformed into E. coli DH5α. The resulting plasmid, pG+host5ΔfbsA, was electroporated into GBS L1 isolate [40], and transformants were selected by growth on erythromycin (2 µg/ml) TS agar at 28°C. Cells in which pG+host5ΔfbsA had integrated into the chromosome were selected by growth of the transformants at ≥37°C with erythromycin selection. Four of such clones were serially passaged for 6 days in Todd-Hewitt (TH) broth (Sigma, St Quentin Fallavier, France) at 28°C without antibiotic pressure to facilitate the excision of plasmid pG+host5ΔfbsA, leaving the desired fbsA deletion in the chromosome. Dilutions of the serially passaged cultures were plated onto TS agar and single colonies were tested for erythromycin susceptibility to identify pG+host5ΔfbsA excisants.

The fbsB gene was deleted in the chromosome of L1 wild type strain and in L1ΔfbsA mutant strain as described above, using the following primers: fbsB_del1 (5′-CCGCGGATCCGTCATGTTACTAATCTTATGC), fbsB_del2 (5′-CCCATCCACTAAACTTA ACACAATCCAAAACGCAATAGG), fbsB_del3 (5′-TGTTTAAGTTTAGTGGATGGGGATC AAGCTTTTGTAGCTAG), and fbsB_del4 (5′-GGGGGTACCCTTCATTAACAATATCTG AG). The non polar deletion mutant strain ΔrgfAC was constructed by deletion of the last 374 bp of the rgfA gene encoding the DNA-binding domain, and of the first 1.055 bp of the rgfC gene in the chromosome of L1 wild type strain (Fig. 1), as described above using the following primers: rgfA_del1 (5′-CCGCGGATCCTCAACAGGCACGTTTAGAGAGA), rgfA_del2 (5′-CCCATCCACTAAACTTAAACAAACGTCTTCAATCCTTCTGCT), rgfC_del3 ( 5′-TGTTTAAGTTTAGTGGATGGGGATAACGCTATTGAGGCATCT), and rgfC_del4 (5′-GGGGGTACCATCACTGGTGGTGGTTGGAT). Complementary DNA sequences in the primers fbsB_del2 and fbsB_del3 and in the primers rgfA_del2 and rgfC_del3 are shown in italics, and the BamHI and KpnI restrictions sites in primers fbsB _del1 and fbsB_del4 and in primers rgfA _del1 and rgfC_del4 are underlined.

Successful gene deletions in ΔfbsA, ΔfbsB, ΔfbsAΔfbsB, and ΔrgfAC mutant strains were confirmed by PCR using primers flanking the deletion site and then by sequencing the amplified fragment.

Plasmid-mediated expression of fbsB, fbsA, and rgfAC in S. agalactiae

The pP1 plasmid [41] was used for complementation analysis of L1 ΔfbsB, ΔfbsA and ΔrgfAC isogenic mutants. The fbsA, fbsB, and rgfAC genes, including their ribosomal binding sites, were amplified from chromosomal DNA of L1 GBS strain by PCR using the Herculase Hotstart DNA Polymerase (Stratagene, Santa Clara, USA) and the following primer sets: fbsB_compl1 (5′-GGGGAGCT CTATTATCTCGTGATAAGTTTTTGATG)/fbsB_compl2 (5′-CCGCGGATCCTTTAAGAT CGCCTTGATAGCAG) for fbsB gene, fbsA_compl1 (5′-GGGGAGCTCAAAAGTAAGGAG AAAATTAATTGTTC)/fbsA_compl2 (5′-CCGCGGATCCCCGATTCCTTTTTATTGATTG C) for fbsA gene, and rgf_compl1 (5′-GGGGAGCTCTCAACAGGCACGTTTAGAGAG)/rgf_compl2 (5′-CCGCGGATCCATCACTGGTGGTGGTTGGATTG) for rgfAC genes. The SacI and BamHI restriction sites used for cloning are underlined. The fbsB, fbsA and rgfAC-containing PCR products and the plasmid pP1 were digested with SacI and BamHI, ligated and transformed into E. coli MC1061. The plasmid pP1 and the resulting plasmids pP1-fbsB, pP1-fbsA and pP1-rgfAC were subsequently transformed by electroporation into the corresponding L1 isogenic mutants ΔfbsB, ΔfbsA and ΔrgfAC.

DNA amplification

Bacterial genomic DNA (20 ng), extracted and purified by conventional methods [42], was used as the template for PCR assays. All primers used (Table 2) were purchased from Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium). The widely distributed lmb gene [43], used as a control, was amplified with primer set lmb130/lmb970. Four primer sets designed in various sites of the rogB gene were used to amplify the rogB gene, and two primer sets were used to amplify rgfBDAC locus, rovS, fbsA, and fbsB genes. The mixture (20 µL) contained primers (0.2 µM each), deoxynucleoside triphosphates (200 µM each), Taq DNA polymerase (0.5 U) (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), and 1.5 mM MgCl2, in 1X buffer. The PCR consisted of an initial 5 min hold at 94°C followed by 30 cycles, each of 1 min denaturation at 94°C, 0.5 min annealing at 55°C or at 50°C, and 1 min elongation at 72°C, followed by a final 10 min elongation step at 72°C (GeneAmp® PCR System 2700, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA).

Table 2. Oligonucleotide primers.

| Name of primer | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Amplified fragment size | Target genes in reference strain | GBS reference strain |

| lmb130 | GTTGTGAGTTTAGTAATGATAGC | 840 bp | lmb | R268 [43] |

| lmb970 | GATATGTCTTGTTCCGCTTG | |||

| rogB59 | GCTATGATTACTACCCTTCCATTACTC | 130 bp | rogB | 6313 [23] |

| rogB189 | TTCGATATTCAGAGAGAGTTGACTG | |||

| rogB298 | GATTCAGGCAGGTTCCCTTT | 891 bp | ||

| rogB1189 | CGGCTATTTGTATCGGAGGA | |||

| rogB350 | GTGCAACTGCTTATCGCATAC | 794 bp | ||

| rogB1144 | GGTGAGCACAAAGGAGAAGAA | |||

| rogB822 | TTGGTCTGAGAAGCGTATCG | 131 bp | ||

| rogB953 | GCAACTTTTACCAACTCGTCA | |||

| rgfB1 | TCTATGGCAAAATGCTTAACG | 1086 | rgfBD | O90R [25] |

| rgfD155 | TCTCTAAACGTGCCTGTTGAA | |||

| rgfD89 | ACGAGGAGACGAAAGTGAAT | 2277 | rgfDAC | |

| rgfC | CGCAAAGTTCTATGGTTCAAAA | |||

| rovS114 | CAAGGTTTGAGAGAGGAGAGTCA | 631 bp | rovS | NEM 316 [24] |

| rovS745 | TCCTGAAGAAGTATCACCAAGTTTT | |||

| rovS82 | AGCAGATGAGCACCTATCCA | 146 bp | ||

| rovS228 | TGAGTGTGCGCCTTAGAATG | |||

| fbsA282 | CAACTTATAGGGAAAAATCCAC | 123 bp | fbsA | 176H4A [20] |

| fbsA 405 | AGTTAACATCGGTCTATTAGC | |||

| fbsA86 | ATCAAGTCCTGTATCTGCTAT | 469 bp | ||

| fbsA555rc | TTCATTGCGTCTCAAACCG | |||

| fbsB354 | GCGATTGTGAATAGAATGAGTG | 129 bp | fbsB | NEM316 [18], [45] |

| fbsB483 | ACAGAAGCGGCGATTTCATT | |||

| fbsB143 | TCGGTCATAAAATAGCGTATGG | 1567 bp | ||

| fbsB1710rc | AAGAATTCAACGGTCGGCTTCGT | |||

| gyrA | CGGGACACGTACAGGCTACT | 128 bp | gyrA | NEM316 [45] |

| rgyrA | CGATACGAGAAGCTCCCACA |

Quantification of specific transcripts with real-time PCR

S. agalactiae L1 wild type isolate and isogenic mutant strains were grown in 50 ml of TH broth to stationary growth phase ([OD595] = 1.2). Bacterial cells pelleted by centrifugation were lysed mechanically with 0.25–0.5 mm glass beads (Sigma) in Tissue Lyser (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for 6 min at 30 Hz. RNA was purified by using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), then treated with DNase using DNAfree kit (Ambion, Cambridgeshire, UK) and checked for DNA contamination by PCR amplification without prior reverse transcription. As no amplicons were obtained, the possibility of DNA contamination during RNA preparation could be excluded. Reverse transcription of 1 µg of RNA was performed with random hexanucleotides and the Quantiscript Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed in a 25 µl reaction volume containing cDNA (50 ng), 12.5 µl QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen), and 0.3 µM of each gene-specific primer set in an iCycler iQ detection system (BioRad). The specific primers for gyrA, fbsA (fbsA282/fbsA405), fbsB (fbsB354/fbsB483) and rovS (rovS82/rovS228) genes were used (Table 2). The PCR consisted of an initial 15 min hold at 95°C followed by 40 cycles, each of 15 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 58°C, and 30 sec with fluorescence acquisition at 72°C. The specificity of the amplified product was verified by generating a melting-curve with a final step of 50 cycles of 10 sec at an initial temperature of 70°C, increasing 0.5°C each cycle up to 95°C. The quantity of cDNA for the investigated genes was normalized to the quantity of gyrA cDNA in each sample. The gyrA gene was chosen as an internal standard since gyrase genes represent ubiquitously expressed house-keeping genes that are frequently used for the normalization of gene expression in quantitative reverse transcription-PCR experiments [23], [24], [44]. The transcription levels of fbsB, fbsA and rovS genes in wild type isolates were treated as the basal levels. Each experiment was performed at least three times. Gene transcript levels of isogenic mutant strains were expressed as fold-transcript levels relative to those of the parental strains. A twofold difference was interpreted as a significant difference in expression between the parental and the mutant strains.

Binding of S. agalactiae to immobilized human fibrinogen

All binding assays were performed in triplicate as previously described [17]. Briefly, flat bottomed 96-well polystyrene plates were coated for 18 h at 4°C with 21 nM human fibrinogen (Diagnostica Stago, Asnières, France) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2). Bacterial cells were harvested from overnight cultures in TH broth and resuspended in PBS. Fibrinogen-coated wells were washed, and then 50 µl of PBS containing 5×106 to 5×108 CFU per ml were added to each well. After incubation for 90 min at 37°C, non binding bacteria were removed by washing with PBS. Bound bacteria were subsequently unbound by the addition of a 0.01% solution of protease/serine protease mix (Sigma) to each well, then the viable bacteria were quantified by plating serial dilutions onto TS agar plates. The percentage of binding to human fibrinogen was obtained by the ratio between the number of bound bacteria and the number of bacteria present in the inoculum. Statistically significant difference in fibrinogen-binding ability was determined at 95% confidence level (P<0.05) for a two-sample t-test assuming unequal variance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Emmanuelle Maguin for supplying pG+host5 plasmid.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by grant no 200700025461 from the Region Centre, France. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Farley MM. Group B streptococcal disease in nonpregnant adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:556–561. doi: 10.1086/322696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuchat A. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease in the United States: shifting paradigms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:497–513. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisharat N, Jones N, Marchaim D, Block C, Harding RM, et al. Population structure of group B streptococcus from a low-incidence region for invasive neonatal disease. Microbiology. 2005;151:1875–1881. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27826-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatellier S, Ramanantsoa C, Harriau P, Rolland K, Rosenau A, et al. Characterization of Streptococcus agalactiae strains by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2573–2579. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2573-2579.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones N, Bohnsack JF, Takahashi S, Oliver KA, Chan M, et al. Multilocus sequence typing system for group B streptococcus. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2530–2536. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2530-2536.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musser JM, Mattingly SJ, Quentin R, Goudeau A, Selander RK. Identification of a high-virulence clone of type III Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus) causing invasive neonatal disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1989;86:4731–4735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quentin R, Huet H, Wang FS, Geslin P, Goudeau A, et al. Characterization of Streptococcus agalactiae strains by multilocus enzyme genotype and serotype: identification of multiple virulent clone families that cause invasive neonatal disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2576–2581. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2576-2581.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rolland K, Marois C, Siquier V, Cattier B, Quentin R. Genetic features of Streptococcus agalactiae strains causing severe neonatal infections, as revealed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and hylB gene analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1892–1898. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1892-1898.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohnsack JF, Whiting A, Gottschalk M, Dunn DM, Weiss R, et al. Population structure of invasive and colonizing strains of Streptococcus agalactiae from neonates of six U.S. Academic Centers from 1995 to 1999. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1285–1291. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02105-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones N, Oliver KA, Barry J, Harding RM, Bisharat N, et al. Enhanced invasiveness of bovine-derived neonatal sequence type 17 group B streptococcus is independent of capsular serotype. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:915–924. doi: 10.1086/500324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manning SD, Springman AC, Lehotzky E, Lewis MA, Whittam TS, et al. Multilocus sequence types associated with neonatal group B streptococcal sepsis and meningitis in Canada. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1143–1148. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01424-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martins ER, Pessanha MA, Ramirez M, Melo-Cristino J. Analysis of group B streptococcal isolates from infants and pregnant women in Portugal revealing two lineages with enhanced invasiveness. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3224–3229. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01182-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poyart C, Réglier-Poupet H, Tazi A, Billoët A, Dmytruk N, et al. Invasive group B streptococcal infections in infants, France. Emerging Infect Dis. 2008;14:1647–1649. doi: 10.3201/eid1410.080185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brochet M, Couvé E, Zouine M, Vallaeys T, Rusniok C, et al. Genomic diversity and evolution within the species Streptococcus agalactiae. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1227–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maisey HC, Doran KS, Nizet V. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of group B Streptococcus virulence. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2008;10:e27. doi: 10.1017/S1462399408000811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajagopal L. Understanding the regulation of Group B streptococcal virulence factors. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:201–221. doi: 10.2217/17460913.4.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenau A, Martins K, Amor S, Gannier F, Lanotte P, et al. Evaluation of the ability of Streptococcus agalactiae strains isolated from genital and neonatal specimens to bind to human fibrinogen and correlation with characteristics of the fbsA and fbsB genes. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1310–1317. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00996-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutekunst H, Eikmanns BJ, Reinscheid DJ. The novel fibrinogen-binding protein FbsB promotes Streptococcus agalactiae invasion into epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3495–3504. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3495-3504.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobsson K. A novel family of fibrinogen-binding proteins in Streptococcus agalactiae. Vet Microbiol. 2003;96:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(03)00206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schubert A, Zakikhany K, Schreiner M, Frank R, Spellerberg B, et al. A fibrinogen receptor from group B Streptococcus interacts with fibrinogen by repetitive units with novel ligand binding sites. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:557–569. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schubert A, Zakikhany K, Pietrocola G, Meinke A, Speziale P, et al. The fibrinogen receptor FbsA promotes adherence of Streptococcus agalactiae to human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6197–6205. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6197-6205.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tenenbaum T, Bloier C, Adam R, Reinscheid DJ, Schroten H. Adherence to and invasion of human brain microvascular endothelial cells are promoted by fibrinogen-binding protein FbsA of Streptococcus agalactiae. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4404–4409. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4404-4409.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutekunst H, Eikmanns BJ, Reinscheid DJ. Analysis of RogB-controlled virulence mechanisms and gene repression in Streptococcus agalactiae. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5056–5064. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5056-5064.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samen UM, Eikmanns BJ, Reinscheid DJ. The transcriptional regulator RovS controls the attachment of Streptococcus agalactiae to human epithelial cells and the expression of virulence genes. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5625–5635. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00667-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spellerberg B, Rozdzinski E, Martin S, Weber-Heynemann J, Lütticken R. rgf encodes a novel two-component signal transduction system of Streptococcus agalactiae. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2434–2440. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2434-2440.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tazi A, Disson O, Bellais S, Bouaboud A, Dmytruk N, et al. The surface protein HvgA mediates group B streptococcus hypervirulence and meningeal tropism in neonates. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2313–2322. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tettelin H, Masignani V, Cieslewicz MJ, Donati C, Medini D, et al. Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial “pan-genome”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2005;102:13950–13955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506758102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janzon L, Arvidson S. The role of the delta-lysin gene (hld) in the regulation of virulence genes by the accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J. 1990;9:1391–1399. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li S, Arvidson S, Möllby R. Variation in the agr-dependent expression of alpha-toxin and protein A among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus from patients with septicaemia. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;152:155–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novick RP, Ross HF, Projan SJ, Kornblum J, Kreiswirth B, et al. Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J. 1993;12:3967–3975. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Queck SY, Jameson-Lee M, Villaruz AE, Bach TL, Khan BA, et al. RNAIII-independent target gene control by the agr quorum-sensing system: insight into the evolution of virulence regulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Cell. 2008;32:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Recsei P, Kreiswirth B, O'Reilly M, Schlievert P, Gruss A, et al. Regulation of exoprotein gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus by agar. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;202:58–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00330517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang S, Ishmael N, Hotopp JD, Puliti M, Tissi L, et al. Variation in the group B Streptococcus CsrRS regulon and effects on pathogenicity. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1956–1965. doi: 10.1128/JB.01677-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kreikemeyer B, McIver KS, Podbielski A. Virulence factor regulation and regulatory networks in Streptococcus pyogenes and their impact on pathogen-host interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:224–232. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(03)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogura M, Tsukahara K, Tanaka T. Identification of the sequences recognized by the Bacillus subtilis response regulator YclJ. Arch Microbiol. 2010;192:569–580. doi: 10.1007/s00203-010-0586-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshida T, Qin L, Egger LA, Inouye M. Transcription regulation of ompF and ompC by a single transcription factor, OmpR. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17114–17123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rivera J, Vannakambadi G, Höök M, Speziale P. Fibrinogen-binding proteins of Gram-positive bacteria. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98:503–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salloum M, van der Mee-Marquet N, Domelier A, Arnault L, Quentin R. Molecular characterization and prophage DNA contents of Streptococcus agalactiae strains isolated from adult skin and osteoarticular infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1261–1269. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01820-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biswas I, Gruss A, Ehrlich SD, Maguin E. High-efficiency gene inactivation and replacement system for Gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3628–3635. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3628-3635.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Framson PE, Nittayajarn A, Merry J, Youngman P, Rubens CE. New genetic techniques for group B streptococci: high-efficiency transformation, maintenance of temperature-sensitive pWV01 plasmids, and mutagenesis with Tn917. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3539–3547. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3539-3547.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dramsi S, Biswas I, Maguin E, Braun L, Mastroeni P, et al. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into hepatocytes requires expression of InlB, a surface protein of the internalin multigene family. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:251–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis J. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. Molecular Cloning: a laboratory manual.1659 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spellerberg B, Rozdzinski E, Martin S, Weber-Heynemann J, Schnitzler N, et al. Lmb, a protein with similarities to the LraI adhesin family, mediates attachment of Streptococcus agalactiae to human laminin. Infect Immun. 1999;67:871–878. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.871-878.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al Safadi R, Amor S, Hery-Arnaud G, Spellerberg B, Lanotte P, et al. Enhanced expression of lmb gene encoding laminin-binding protein in Streptococcus agalactiae strains harboring IS1548 in scpB-lmb intergenic region. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10794. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glaser P, Rusniok C, Buchrieser C, Chevalier F, Frangeul L, et al. Genome sequence of Streptococcus agalactiae, a pathogen causing invasive neonatal disease. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1499–1513. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]