Abstract

The baculovirus protein P143 is essential for viral DNA replication in vivo, likely as a DNA helicase. We have demonstrated that another viral protein, LEF-3, first described as a single-stranded DNA binding protein, is required for transporting P143 into the nuclei of insect cells. Both of these proteins, along with several other early viral proteins, are also essential for DNA replication in transient assays. We now describe the identification, nucleotide sequences, and transcription patterns of the Choristoneura fumiferana nucleopolyhedrovirus (CfMNPV) homologues of p143 and lef-3 and demonstrate that CfMNPV LEF-3 is also responsible for P143 localization to the nucleus. We predicted that the interaction between P143 and LEF-3 might be critical for cross-species complementation of DNA replication. Support for this hypothesis was generated by substitution of heterologous P143 and LEF-3 between two different baculovirus species, Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus and CfMNPV, in transient DNA replication assays. The results suggest that the P143-LEF-3 complex is an important baculovirus replication factor.

The family Baculoviridae represents a unique group of large rod-shaped enveloped viruses carrying a double-stranded circular DNA genome and replicating only in invertebrates. Many of the advances in understanding the molecular biology of baculoviruses have resulted from studies of variants of the type species Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV).Nucleopolyhedroviruses (NPVs) replicate in cell nuclei and are characterized by the production of two virion phenotypes, the budded virions and the occlusion-derived virions. Both forms are produced following infection of cells in culture and are characteristic of late stages of the viral replication cycle following initiation of viral DNA replication at about 8 h postinfection (37). The early events prior to this time are characterized by the expression of several viral gene products, some of which have been shown to be essential for viral DNA replication. Nine viral genes (ie-1, ie-2, p143, dnapol, lef-1, lef-2, lef-3, pe38, and p35) are involved in directing replication of plasmids carrying viral DNA inserts in transfected cells (20, 31, 38). These data supported earlier genetic analysis of a conditional lethal AcMNPV mutant defective in DNA replication (13), which led to the description of the p143 gene: its nucleotide sequence and the identification of the lesion in the 1,221-amino-acid open reading frame (ORF) (143 kDa) responsible for the temperature-sensitive DNA negative phenotype (29). The p143 gene is essential for viral DNA replication in vivo since no replication occurs in cells infected at the nonpermissive temperature with ts8 (29).

Biochemical characterization of extracts from AcMNPV-infected cells showed that P143 copurified through hydroxylapatite and coeluted from single-stranded DNA cellulose with another viral protein called LEF-3, suggesting a possible direct interaction between P143 and LEF-3 (22, 39). LEF-3, also demonstrated to be essential for DNA replication in transient assays, is a single-stranded DNA binding protein (14) that forms a homotrimer in solution (11). We have also clearly demonstrated that with AcMNPV, LEF-3 is necessary for the transport of P143 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (39). These results have been confirmed by a yeast two-hybrid analysis of P143 and LEF-3 that also revealed an interaction between these two proteins (12). P143 also binds to DNA in a non-sequence-specific manner (22), a characteristic of some replication proteins including DNA helicases, DNA polymerases, primases and their accessory factors, DNA ligases and DNA topoisomerases (4).

P143 may also play a role in the species specificity of baculovirus replication. Although P143 from AcMNPV and that from Bombyx mori NPV (BmNPV) share about 95% identity in their amino acid sequences, substituting a small number of amino acids that are different between the two P143 proteins (AcMNPV P143 amino acids 564 and 577 with the BmNPV P143 amino acids 565 and 578) dramatically altered the host range of AcMNPV. These changes permitted AcMNPV to replicate more efficiently in B. mori cell lines and to kill B. mori larvae (3, 18). In addition, several attempts have been made to complement AcMNPV P143 with homologous genes from other baculovirus species but all of these have failed (5, 12, 15), suggesting that there are important differences in P143 from different viral species that regulate P143 function during replication.

We have been investigating the genetic organization of a baculovirus specific for the spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana), called C. fumiferana NPV (CfMNPV), because it has potential for use in forestry as a biological pest control agent against the spruce budworm. We have previously shown that the replication of CfMNPV and AcMNPV is host cell specific (25) and therefore decided to investigate the possible role of P143 and LEF-3 in this specificity. We now report the identification and sequences of the CfMNPV p143 and lef-3 homologues and investigations into their interactions together and in combination with their AcMNPV homologues in determining their intracellular localization as well as their ability to complement each other in transient DNA replication assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and virus.

C. fumiferana 124T cells (Cf124T) and CfMNPV (strain EC1) were propagated and maintained as previously described (25). Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf21) cells and AcMNPV strain HR3 were propagated and maintained as previously described (29).

Sequence analysis and plasmid constructs.

The location of the CfMNPV p143 gene was previously mapped by Southern hybridization to the right end of the BamHI E fragment region (34). The complete CfMNPV p143 sequence was constructed by using a series of synthetic oligonucleotides as primers on plasmid clones of the CfMNPV BamHI E (pCfBamE) and HindIII MN2 (pCfHindMN2) fragments. Both strands were completely sequenced (4,783 nt).

The location of the CfMNPV lef-3 gene was predicted to lie downstream of the CfMNPV dnapol gene, previously shown to overlap the left end of the CfMNPV EcoRI G fragment (26). Sequence analysis of the right end of CfMNPV EcoRI G revealed homology with the AcMNPV lef-3 gene so the right end of EcoRI G and the left end of the adjoining EcoRI H fragments were sequenced with universal and synthesized oligonucleotide primers. Some reactions used pCfHindB as template in order to sequence through the EcoRI G-H junction site. The sequencing reactions were performed by the core facility for protein and DNA chemistry (CORTEC, Queen's University). The sequences were compiled and analyzed with computer programs AssemblyLIGN and MacVector (Accelrys Inc.).

The CfMNPV p143 ORF was subcloned by digesting pCfBamE with BamHI and PacI to release a 3,911-bp fragment containing the complete P143 ORF. This fragment was cloned into BamHI- and PacI-digested pNEB193 to generate pNEB193-Cfp143. The 3,924-bp BamHI-SalI fragment of pNEB193-Cfp143 was cloned either into BglII- and SalI-digested pIE1 h/PA (8) to generate pIE1hrCfp143 or into SalI- and BamHI-digested pBluescript SK(−) to generate pCfP143-SB(3.9).

The complete lef-3 ORF was amplified by PCR using purified CfMNPV DNA as template with primers C-6493 (5′-CGGGATCCTAAATCAGTTGGCAAG-3′) and C-6795 (5′-CGGGATCCACATGATGGCCACCAAAC-3′). The amplification product was digested with BamHI and ligated into BamHI-digested pBluescript SK(−) to generate pBSCfLEF-3. pBSCfLEF-3 was digested with BamHI and the 1.3-kb fragment carrying the CfMNPV lef-3 ORF was cloned into pIE1/hr/PA cut with BglII to generate pIE1hrCflef-3. The 1.3-kb BamHI fragment was also cloned into pGEX-3X (35) to generate pGEX3-CfLEF-3, in preparation for overexpression of CfMNPV LEF-3 in Escherichia coli.

The CfMNPV p143 coding region was cloned in frame with the green fluorescence protein (GHP) by amplifying the GFP region of pEGFP-1 (Clontech) with primers C-3417 (5′-GAG AAA GGC GGA CAG GTA TCC-3′) and C-14112 (5′-TCG AGA TCT CTT GTA CAG CTC GTC C-3′, where the underlined sequence generated a new BglII site at the C terminus of the GFP ORF). The product was digested with BamHI and BglII and ligated into pIE1hrCfp143 digested with BamHI to generate pIE1hrCfp143GFP.

Preparation of polyclonal antibodies to LEF-3.

The CfMNPV LEF-3 protein was expressed as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion product by inducing JM109 cells transformed with pGEX3-CfLEF-3 with 0.4 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 16 h at 37°C. The cells were collected by centrifugation and suspended in equilibration buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 2 mM EDTA, 0.4 M NaCl) and 2 mM mercaptoethanol. Following sonication, the suspension was centrifuged (8,000 × g for 10 min) and the supernatant was loaded onto an equilibrated glutathione agarose column (Sigma). After washing with 50 mM Tris (pH 8), the GST-CfLEF-3 fusion protein was eluted with 10 mM reduced glutathione in 50 mM Tris (pH 8). The AcMNPV LEF-3 protein was expressed as a His-tagged fusion product by cloning the open reading frame into pRSET-B (Invitrogen) to produce pRSETB-Aclef3 and inducing transformed BL21(DE3)pLysS cells with 0.4 mM IPTG for 2 h at 37°C. Inclusion bodies containing LEF-3 protein were purified. New Zealand White rabbits received intramuscular injections of 100 μg of protein in Titremax (CedarLane Laboratories) and received boosters three times, every 3 weeks. The rabbit antiserum was collected 3 days after the last boost.

RNA transcription.

Total intracellular RNA was extracted from either mock- or CfMNPV-infected Cf124T cells at various times postinfection using guanidine-phenol (9, 10). Poly(A)+ RNA was selected from total RNA on oligo(dT)-cellulose using the Micro-Fast Track kit (Invitrogen). Total RNA (30 μg) or poly(A)+ RNA (700 ng) was denatured with formaldehyde, electrophoresed through agarose gels, and transferred by downward blotting (19) in 50 mM sodium hydroxide to positively charged nylon membranes (Nytran Plus; Schleicher and Schuell). The blots were neutralized in 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) for 15 min, and the RNA was fixed to the membrane by baking for 2 h at 80°C. The blots were prehybridized at 60°C for 24 h and then hybridized with 32P-labeled riboprobes at 60°C for 24 h in solutions containing 50% formamide, 5× SSC, 0.1% polyvinyl pyrrolidone, 0.1% Ficoll, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.5), and denatured herring testis DNA (100 μg/ml) (7). Following three washes of 30 min each in 0.1× SSC at 65°C, the membranes were exposed to X-ray film. The sizes of the transcripts were determined from RNA standards (Invitrogen).

A strand-specific riboprobe specific for the CfMNPV lef-3 ORF was generated by linearizing pBSCfLEF-3 with XhoI and radiolabeling cRNA with [32P]UTP in the presence of T3 RNA polymerase. A strand-specific riboprobe specific for the CfMNPV p143 ORF was generated by BamHI digestion of pCfP143-SB(3.9) and radiolabeling cRNA with [32P]UTP in the presence of T7 RNA polymerase.

The 5′ and 3′ termini of the p143 and lef-3 mRNAs, derived from total intracellular RNA harvested at 18 h postinfection, were identified using a 5′- and 3′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) system following the manufacturer's protocols (Invitrogen). A cDNA of the 5′ end of the p143 mRNA, generated with primer C-1360 (5′-CGCAAAGGCTGTTAAAGGTAG-3′), was PCR amplified using the abridged anchor primer (Invitrogen) and primer C-22031 (5′-GGAATTCCAAACAGTTTAACGGGCGGC-3′). Then, a second PCR was prepared using the abridged universal amplification primer (Invitrogen) and the nested primer C-8114. The product of this reaction was purified and sequenced using a second nested primer, C-22303 (5′-CACCATCCATTCTTGAACAGG-3′). A cDNA of the 5′ end of the lef-3 mRNA, generated with primer C-5774 (5′-CAGTTGGCAAGCGCGAGC-3′), was PCR amplified using the abridged anchor primer (Invitrogen) and primer C-21845 (5′-GTGTAGTAGTCGTCGTCGGTGTTGG-3′). Then, a second PCR was prepared using the abridged universal amplification primer and the nested primer C-6721 (5′-GTAACACTCTTGCTCAACC-3′). The product of this reaction was purified and sequenced using a nested primer C-10435 (5′-GCAATCGTTTACGTGCTC-3′). A cDNA of the 3′ end of the p143 mRNA was generated with an oligo(dT)-containing adaptor primer (Invitrogen) and primer C-0089 (5′-CTCTGGCGTATCTAACGCAG-3′). The product was PCR amplified with primer C-22080 (5′-CAAGACGCTGCTGGACAACGAC-3′) and the abridged universal amplification primer (Invitrogen). The product of this reaction was purified and sequenced with the nested primer C-22081 (5′-CACAACTACGACGAGCGTGG-3′). A cDNA of the 3′ end of the lef-3 mRNA was generated with an oligo(dT)-containing adaptor primer (Invitrogen) and primer C-21846 (5′-CCAACACCGACGACGACTACTACAC-3′). The product was PCR amplified with primer C-21912 (5′-GGAATTCAATGGAGGAAGACGACAGC-3′) and the abridged universal amplification primer (Invitrogen). The product of this reaction was purified and sequenced with the nested primer C-22437 (5′-GTTGGGTTTGCTGAAATACG-3′).

Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence.

Infected cell extracts were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-10% PAGE). Gels were either stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-C) for immunoblotting. The immunoblot membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk powder overnight and then probed with a 1:10,000 dilution of rabbit polyclonal antibodies, washed, incubated with a 1:30,000 dilution of donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, and visualized with a chemiluminescent detection system (NEN).

Sf21 cells on coverslips, either infected with whole virus or transfected with plasmid DNA, were prepared for immunofluorescence by washing with PBS, fixing with 10% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, washing, and then permeabilizing in 100% methanol for 20 min at −20°C. Following three washes with PBS-T (PBS plus 0.1% Tween 20), the cells were blocked for 1 h in 1% goat serum in PBS-T, then incubated with rabbit-polyclonal anti-AcMNPV P143 (1:1,000) and/or mouse-monoclonal anti-AcMNPV LEF-3 (1:1,000) antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Following a wash with PBS-T, the coverslips were incubated for 1 h in goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 568 (Molecular Probes) and/or goat-anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes). The coverslips were again washed with PBS-T, then mounted on glass microscope slides in 50% glycerol. The slides were examined with a Meridian InSight Plus confocal microscope and a KX85 camera (Apogee Instruments). Color images were generated and analyzed with Max Im DL version 2.00 (Cyanogen Productions) (Cancer Research Labs at Queen's University).

Transient DNA replication assays.

Sf21 cells (106 cells) in 35-mm-diameter dishes were washed three times with 1 ml of TC-100 medium and then replaced with TC-100 (1.5 ml per dish). A 20× stock of DOPE/DDAB (6, 36) liposome chemicals was mixed by vortexing with 1 ml of sterile water. An equal molar amount of plasmids expressing all of the AcMNPV genes essential for viral DNA replication (AcMNPV replication library: pAcie1, pAclef-1, pAclef-2, pAclef-3, pAcdnapol, pAcp143, pAcp35, and pAcie2pe38) (40) was mixed with a 1:6 ratio of DOPE/DDAB liposome reagent and diluted to a final volume of 200 μl with TC-100. In some experiments, the plasmids pAcLEF-3 and pAcp143 were replaced with CfMNPV-expressing plasmid pIE1hrCflef-3, pIE1hrCfp143, or pIE1hrCfp143GFP. After incubation of the transfection mixture for 30 min at room temperature, 500 μl of TC-100 medium was added to the DNA-DOPE mixture, and the entire mixture was added to washed Sf21 monolayers and incubated at 28°C for 6 h. After incubation, the cells were washed three times with TC-100 medium, covered with fresh TC-100 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, and incubated at 28°C for 48 h. The replication of plasmid DNA was monitored by DpnI digestion of the total intracellular DNA as previously described (38).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers. The sequence of the CfMNPV p143 gene region has been deposited with GenBank under the accession number AF127530. The sequence of the CfMNPV lef-3 gene region has been deposited with GenBank under the accession number AF127908.

RESULTS

Identification and sequence of the CfMNPV p143 and lef-3 genes.

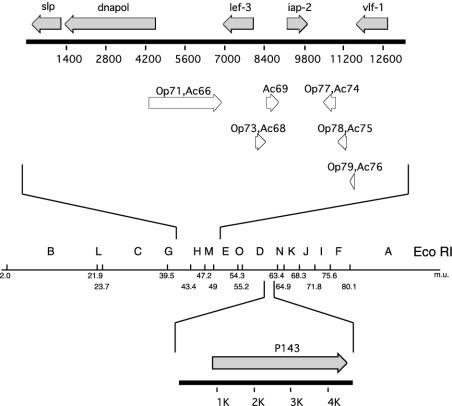

The promoter region of the CfMNPV p143 gene was previously located within the HindIII MN2 region, a region at the right end of the CfMNPV BamHI E fragment (34). Plasmid clones of these fragments were used as templates with a variety of synthetic primers to complete 4,788 bp of sequence that revealed a large open reading frame (ORF) of 3,684 bp, predicted to code for a protein of 1,228 amino acids (141.7 kDa) (Fig. 1). The product of this ORF was about 85% identical with the amino acid sequence of Orgyia pseudotsugata NPV (OpMNPV) P143 and 57% identical with AcMNPV P143 (Table 1). Although recognizable, the CfMNPV P143 gene was only 21 to 36% identical to the homologous genes of other NPV and granulovirus (GV) P143s (Table 1). All of the NPV P143s were conserved in size, ranging from 1,218 to 1,223 amino acids; however, the GV P143s were smaller (1,124 to 1,159 amino acids). Comparisons of the P143 amino acid sequences revealed that CfMNPV P143 retains the conserved helicase motifs (motifs I, Ia, II, III, IV, V, and VI) that we previously predicted in the AcMNPV P143 protein (24, 29). The motifs A, B, and C, characterized by superfamily 3 helicase (21), were also highly conserved among all the baculovirus P143 proteins. Additional regions of P143 contain conserved amino acids, including a region previously shown to extend the host range of AcMNPV to B. mori cells (AcMNPV amino acids 551 to 578, CfMNPV amino acids 558 to 584). This 27-amino-acid region is 74% identical between AcMNPV and CfMNPV and is highly conserved between all P143 proteins identified to date.

FIG. 1.

Location of identifiable ORFs in the sequenced region of p143 and lef-3. The regions of CfMNPV that were sequenced to identify the lef-3 (above) and p143 (below) genes are indicated and oriented on the CfMNPV genome EcoRI restriction fragment map. The presence of ORFs with predicted functions is indicated as filled arrows above the scale in base pairs. ORFs with homologues in OpMNPV and AcMNPV and their numbers but no specific function are indicated as open arrows below the scale line.

TABLE 1.

Similarities between P143 amino acid sequences

| Protein | % Identity (similarity) to:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AcMNPV (1,221)a | BmNPV (1,222) | OpMNPV (1,223) | LdMNPV (1,218) | SeMNPV (1,222) | PxGV (1,124) | TnGV (1,158) | XcGVb (1,159) | |

| CfMNPV | 57 (15) | 56 (15) | 85 (6) | 36 (21) | 36 (20) | 22 (16) | 21 (18) | 21 (18) |

| AcMNPV | 95 (1) | 58 (14) | 39 (21) | 40 (18) | 24 (16) | 23 (17) | 24 (17) | |

| BmNPV | 57 (14) | 39 (21) | 41 (18) | 24 (17) | 23 (17) | 24 (17) | ||

| OpMNPV | 35 (21) | 36 (19) | 22 (16) | 21 (18) | 21 (18) | |||

| LdMNPV | 48 (19) | 24 (15) | 23 (17) | 24 (17) | ||||

| SeMNPV | 24 (17) | 24 (15) | 24 (15) | |||||

| PxGV | 47 (19) | 47 (18) | ||||||

| TnGV | 88 (6) | |||||||

The number of amino acid residues in the individual P143 proteins is given in parentheses.

XcGV, Xestia c-nigrum GV.

The CfMNPV lef-3 gene was predicted to map downstream of the DNA polymerase gene previously identified near the right end of the CfMNPV EcoRI G fragment (26). Sequence analysis of this region identified a 1,119-bp ORF (373 amino acids, 43.0 kDa) predicted to code for the CfMNPV lef-3 homologue. ORFs corresponding to iap2 (252 amino acids, 28.1 kDa) and vlf-1 (374 amino acids, 43.2 kDa) homologues were also identified in this region (Fig. 1). CfMNPV LEF-3 is about 75% identical in amino acid sequence with the OpMNPV LEF-3 protein but exhibits much lower levels of similarity with other baculovirus LEF-3 proteins (Table 2). In addition, the LEF-3 proteins varied considerably in size from 297 amino acids (Plutella xylostella GV [PxGV]) to 422 (Spodoptera exigua NPV). The sequences of the upstream genes slp, dnapol, and part of orf71 have been previously described (26, 27).

TABLE 2.

Similarities between LEF-3 amino acid sequences

| Protein | % Identity (similarity) to:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AcMNPV (385)a | BmNPV (385) | OpMNPV (373) | LdMNPV (374) | SeMNPV (422) | PxGV (297) | HaSNPV (379)b | XcGV (351) | |

| CfMNPV | 39 (21) | 39 (22) | 75 (10) | 22 (17) | 24 (17) | 12 (14) | 23 (20) | 9 (19) |

| AcMNPV | 91 (2) | 39 (22) | 26 (18) | 25 (16) | 15 (15) | 23 (20) | 11 (18) | |

| BmNPV | 39 (23) | 25 (18) | 25 (17) | 15 (14) | 23 (19) | 12 (18) | ||

| OpMNPV | 24 (17) | 24 (19) | 12 (15) | 22 (21) | 9 (20) | |||

| LdMNPV | 26 (21) | 11 (13) | 24 (21) | 13 (18) | ||||

| SeMNPV | 10 (13) | 26 (15) | 12 (15) | |||||

| PxGV | 12 (15) | 18 (15) | ||||||

| HaSNPV | 12 (17) | |||||||

The number of amino acid residues in the individual LEF-3 proteins is given in parentheses.

HaSNPV, Helicoverpa armigera SNPV.

Transcription analysis of p143 and lef-3.

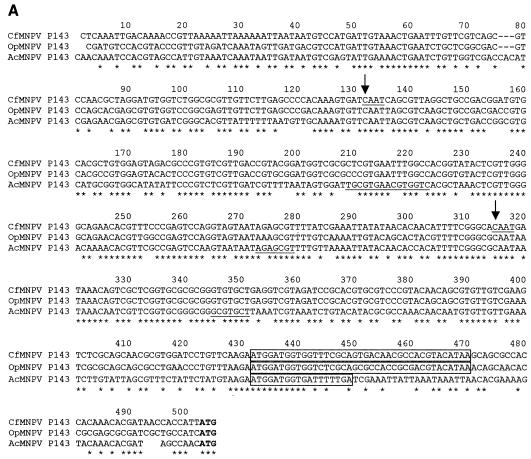

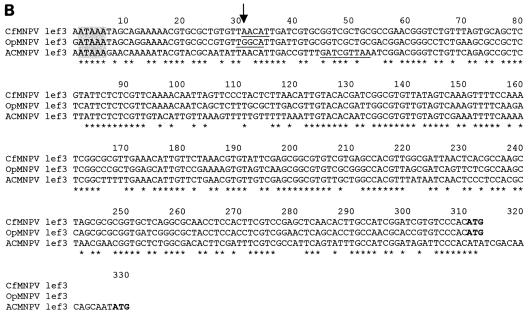

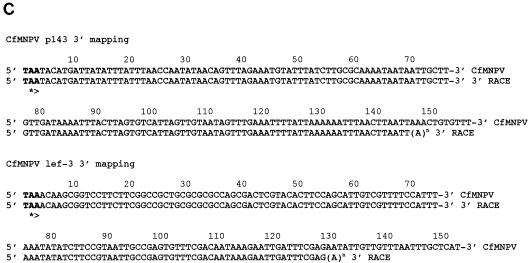

The expression of the CfMNPV p143 and lef-3 genes was investigated by Northern blot analysis using gene-specific riboprobes hybridized to poly(A)+ RNA prepared from Cf124T cells at various times after CfMNPV infection. A 4.4-kb transcript was detected by 6 h postinfection with a p143-specific probe spanning the complete p143 ORF (Fig. 2B). This transcript continued to increase in abundance from 12 through 48 h postinfection and appeared to be the major mRNA from this region. A comparison of the p143 promoter regions of CfMNPV with OpMNPV (2) and AcMNPV (30) showed that all three encode minicistrons upstream of the start codon for the P143 ORF (Fig. 3A). CfMNPV and OpMNPV both encode a 12-amino-acid minicistron while AcMNPV encodes a five amino acid minicistron. The P143 transcription start sites were identified by 5′ RACE using primers shown in Fig. 2A. Two different mRNA preparations were used to generate cDNAs and both cDNA preparations were subjected to PCR and sequence analysis. The results were identical. Two PCR products, produced with primer C-8114 (Fig. 2C), were sequenced identifying a strong start site at 188 (more abundant PCR product) and a weaker site at 371 nucleotides upstream of the translation start codon. Both of these sites initiated within the sequence CAAT (Fig. 3A) and are conserved in OpMNPV and AcMNPV but the AcMNPV p143 transcription start site was previously mapped by primer extension analysis about 30 nucleotides closer to the translation start codon (30). The major start site mapped 10 nucleotides upstream of a CAGT sequence that is conserved between CfMNPV and OpMNPV. Although the sequence downstream of p143 is relatively A/T rich, there is no potential polyadenylation signal sequence (AATAAA) in the sequenced region downstream of the p143 ORF. However, 3′ RACE sequencing of the PCR produced with primer C-22080 mapped the p143 polyadenylation addition site 142 nucleotides downstream of the stop codon, following a highly AT-rich region of almost 30 nucleotides. Together these data indicate a minimum size of 4,015 nucleotides for the p143 transcript, in good agreement with the size of the p143 mRNA seen on Northern blots.

FIG. 2.

Expression and mapping of P143 and LEF-3 transcripts. The upper diagrams (A) show the orientation of the mRNAs, the open reading frames, and the location of the strand-specific riboprobes used in the Northern analysis for the CfMNPV p143 and lef-3 genes. Also shown are the names and locations of the primers used in the 5′ and 3′ RACE analysis to map the 5′ and 3′ ends of the p143 and lef-3 mRNAs. (B) Poly(A)+ RNA, prepared from CfMNPV-infected Cf124T cells at the times indicated was resolved by 0.6% agarose gel electrophoresis. Blots of these gels were probed with strand-specific riboprobes corresponding to the p143 and lef-3 genes. Similarly prepared poly(A)+ RNA from mock-infected cells was included as controls (M). The exposures were long, to enable the detection of virus-specific mRNA at the early time point (6 h postinfection). The sizes of the detectable transcripts are indicated on the right side of each blot. (C) PCR products generated from the 5′and 3′ RACE analysis of the p143 and lef-3 mRNA were separated on agarose gels. Sequence analysis of these products revealed the 5′ transcription start site and 3′ polyadenylation site for each gene (shown in Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Promoter sequence for p143 and lef-3. An alignment of the promoter regions of the p143 (A) and lef-3 (B) genes from CfMNPV, OpMNPV, and AcMNPV is shown. TATA-box-like sequences are shaded, the location of published transcription start sites are underlined, minicistron coding regions are boxed and the translation start codons are in bold. The locations of the transcription start sites for the CfMNPV p143 and lef-3 genes, as determined by sequence analysis of PCR products, are shown with arrows. (C) The sequences of the 3′ ends of the p143 and lef-3 mRNAs as determined by 3′ RACE and sequence analysis of PCR products are shown below the appropriate genomic sequence.

A 1.6-kb transcript was detected at 6 h postinfection with a CfMNPV lef-3-specific probe spanning the complete lef-3 ORF plus 187 downstream nucleotides. This mRNA increased dramatically in abundance from 12 through 48 h postinfection (Fig. 2B). In addition, many larger transcripts were detected at 24 and 48 h postinfection. The lef-3 transcription start site was mapped by 5′ RACE and sequencing of the PCR product produced with primer C-6721 (Fig. 2C). A single site at the beginning of the sequence AACATTGA 279 nucleotides upstream of the lef-3 ORF and 26 nucleotides downstream of a putative TATA box (Fig. 3B) was identified (Fig. 3B). A comparison of the CfMNPV lef-3 promoter region with those of OpMNPV (1) and AcMNPV (23) revealed a conserved TATA box sequence about 25 nucleotides upstream of the transcription start site. The CfMNPV and OpMNPV lef-3 transcription start sites mapped within one nucleotide of each other, just upstream of a conserved CATTGA sequence. However, the transcription start site for the AcMNPV lef-3 gene has been mapped about 14 nucleotides further downstream (23) (Fig. 3B). The 3′ RACE and sequencing of the PCR product produced with primer C-22437 (Fig. 2C) mapped the lef-3 transcript polyadenylation site to 125 nucleotides downstream of the translation stop codon and 14 nucleotides downstream of a polyadenylation addition signal. The determined size for the lef-3 mRNA (1,528 nucleotides) was in good agreement with the estimated size of the transcript (1.6 kb) observed on Northern blots.

Protein expression of CfMNPV lef-3.

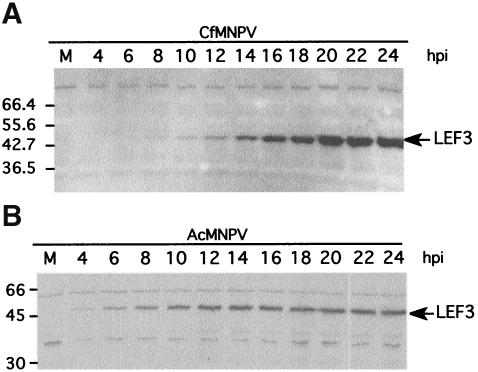

The expression of the CfMNPV lef-3 gene was investigated by immunoblotting to determine the time and level of protein expression in CfMNPV-infected cells. Cf124T cells, infected with CfMNPV, were harvested at various time points postinfection and the infected cell samples were analyzed by immunoblotting using a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against CfMNPV LEF-3. A 44-kDa band, first detected by 8 h postinfection, increased in expression levels through to 24 h postinfection (Fig. 4). The CfMNPV LEF-3 protein increased in expression until at least 48 h postinfection (data not shown). The observed molecular mass coincided closely with the predicted molecular mass of 43.0 kDa for the CfMNPV LEF-3 gene. As expected for a protein required for viral DNA replication, the CfMNPV lef-3 gene was expressed prior to the reported time of initiation of viral DNA replication (25). For comparison, an immunoblot of AcMNPV-infected Sf21 cells was prepared. AcMNPV LEF-3 was easily detectable at 4 h postinfection confirming that the virus replication cycle proceeds faster for AcMNPV than CfMNPV as previously noted (25). Similar blots were also probed with polyclonal antibodies against the AcMNPV P143 protein but no signal was detected, indicating that these antibodies did not cross-react with CfMNPV P143 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Temporal expression of CfMNPV LEF-3 in infected cells. Cf124T cells, infected with CfMNPV, were harvested at the indicated times after infection (A). Whole-cell extracts were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE, blotted onto nitrocellulose filters, and then probed with polyclonal antibodies against CfMNPV LEF-3. CfMNPV LEF-3 was first clearly detectable at 8 h postinfection. For comparison, a similar blot of extracts prepared from AcMNPV-infected Sf21 cells and probed with LEF-3-specific polyclonal antibody is shown. (B) AcMNPV LEF-3 was first detectable at 4 h postinfection.

Interaction between AcMNPV and CfMNPV P143 and LEF-3.

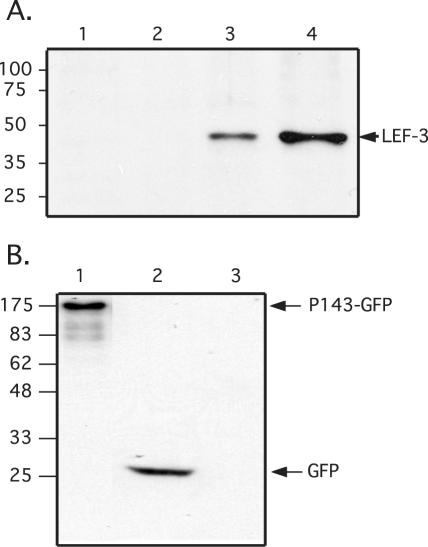

We have previously shown that in AcMNPV-infected Sf21 cells, LEF-3 is essential for the translocation of P143 into the nucleus (39). It was important to demonstrate that this function is required in other baculovirus systems since the lef-3 gene is not conserved in all baculoviruses. In addition, because we were interested in investigating the interaction between the CfMNPV LEF-3 and P143 proteins in the absence of other viral proteins, plasmids expressing the CfMNPV p143 (pIE1hrCfp143) or lef-3 (pIE1hrCflef-3) genes, both driven by the AcMNPV immediate-early promoter-1 (ie-1), were constructed and individually transfected into Sf21 cells. To confirm the expression of CfMNPV LEF-3 from this plasmid, Sf21 cell extracts obtained at 24 h posttransfection were analyzed by immunoblotting. CfMNPV-infected Cf124T cells were used as a positive control. A 44-kDa CfMNPV protein was observed in both pIE1hrCflef-3-transfected Sf21 cells and in CfMNPV-infected Cf124T cells (Fig. 5A). Larger amounts of LEF-3 were observed in Sf21 cells transfected with the expression vector than were observed in CfMNPV-infected Cf124T cells, clearly demonstrating the expression of large amounts of LEF-3 in the transfected cells. No band was detected in the control mock-infected cells.

FIG. 5.

Expression of LEF-3 and P143-GFP following transfection or infection and detected by immunoblotting. (A) Whole-cell extracts (5 × 104 cells per lane) were prepared from mock-infected Sf21 cells (lane 1), mock-infected Cf124T cells (lane 2), CfMNPV-infected Cf124T cells (lane 3), or pIE1hrCflef-3-transfected Sf21 cells (lane 4) at 24 h posttransfection or postinfection. The extracts were analyzed by SDS-10% PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with LEF-3-specific polyclonal antibody. The relative mobility of molecular weight markers is shown on the left and the immunoreactive proteins are labeled on the right. (B) Whole-cell extracts (5 × 104 cells per lane) were prepared from pIE1hrCfp143GFP-transfected Sf21 cells (lane 1), pAcGFP-transfected Sf21 cells (lane 2), and mock-transfected Sf21 cells (lane 3) harvested at 24 h posttransfection. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed by SDS-11.25% PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with anti-GFP monoclonal antibody. The relative mobility of the molecular weight markers is shown on the left and the immunoreactive proteins are labeled on the right.

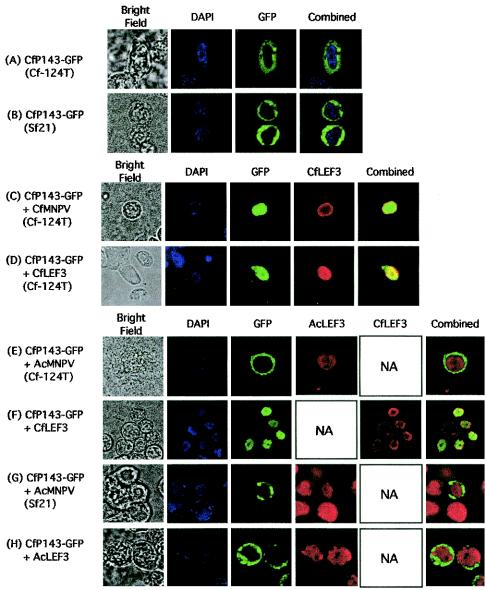

Attempts were made to monitor the expression of CfMNPV P143 in pIE1hrCfp143-transfected Sf21 cell extracts by immunoblotting using a polyclonal antibody against AcMNPV P143 but no cross-reactivity was seen (data not shown). Therefore, in order to monitor the expression and localization of CfMNPV P143, a plasmid was constructed where the CfMNPV p143 gene was fused in frame with the GFP reporter gene and the fusion product was driven by the AcMNPV ie-1 promoter (pIE1hrCfp143GFP). A protein of the predicted size was observed in extracts of pIE1hrCfp143GFP-transfected cells when probed with an antibody directed against GFP (Fig. 5B). Intracellular location of the fusion protein was monitored by direct fluorescence microscopy. When pIE1hrCfp143GFP was transfected on its own, GFP fluorescence was only observed in the cytoplasm in both Sf21 and Cf124T cells (Fig. 6A and B), supporting our previous data with AcMNPV that, on its own, P143 remains cytoplasmic (39). These results also demonstrated that the AcMNPV ie-1 promoter was functional in both Sf21 and Cf124T cells since both Lef-3 and P143 were expressed under the control of this promoter in Cf124T cells, a result that has not been previously demonstrated. When pIE1hrCfp143GFP was transfected into Cf124T cells that were subsequently infected with CfMNPV, CfMNPV P143-GFP localized to the nucleus (Fig. 6C). This result demonstrated that the fusion of GFP to P143 did not interfere with its recognition and successful translocation to the nucleus by the CfMNPV LEF-3 protein. We confirmed that this translocation was mediated by the CfMNPV LEF-3 protein by cotransfecting pIE1hrCfp143GFP and pIE1hrCflef-3 into Cf124T or Sf21 cells (Fig. 6D). GFP fluorescence was observed in the nuclei of cotransfected cells, clearly demonstrating that GFP-tagged CfMNPV P143 could interact with CfMNPV LEF-3. These results also demonstrate that no C. fumiferana cell-specific factors were required for the interaction between CfMNPV P143 and LEF-3 since correct nuclear localization occurred in both Cf124T and Sf21 cells.

FIG. 6.

Intracellular localization of P143 and LEF-3 following transfection detected by immunofluorescence. Cf124T (A, C, D, and E) or Sf21 (B and F to H) cells, transfected with plasmids expressing CfMNPV P143 fused to GFP (pIE1hrCfp143GFP) (A to H), CfMNPV LEF-3 (pIE1hrCflef-3) (D and H), or AcMNPV LEF-3 (pAcLEF-3) (G), were mock infected or infected with CfMNPV (C) or AcMNPV (E and F). At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were either observed directly for GFP fluorescence or were also processed for immunofluorescence using antibodies directed against CfMNPV LEF-3 (CfLEF3) or AcMNPV LEF-3 (AcLEF3). Nuclear DNA was stained with DAPI. Only infection with CfMNPV or cotransfection with CfMNPV LEF-3 resulted in nuclear GFP fluorescence from CfMNPV P143-GFP.

We then investigated the interaction of P143 and LEF-3 derived from the two different species of baculoviruses, AcMNPV and CfMNPV. Cf124T cells or Sf21 cells were transfected with pIE1hrCfp143GFP, then infected with AcMNPV. GFP fluorescence was detectable in the cytoplasm in both cell lines (Fig. 6E and G), indicating that AcMNPV LEF-3 did not transport CfMNPV P143 to the nucleus in either cell line. These results suggest that a specific interaction between homologous P143 and LEF-3 is required for the correct nuclear transport of P143. This hypothesis was confirmed by cotransfecting Sf21 cells with pIE1hrCfp143GFP and plasmids expressing either AcMNPV LEF-3 or CfMNPV LEF-3. Nuclear fluorescence of P143, indicating transport to the nucleus, was only observed when CfMNPV LEF-3 was present (Fig. 6F and H). Because the correct localization of P143 and LEF-3 to the nucleus is required for baculovirus DNA replication, we then investigated the interaction of the heterologous gene products to determine whether this interaction was necessary for DNA replication.

Heterologous proteins in DNA replication.

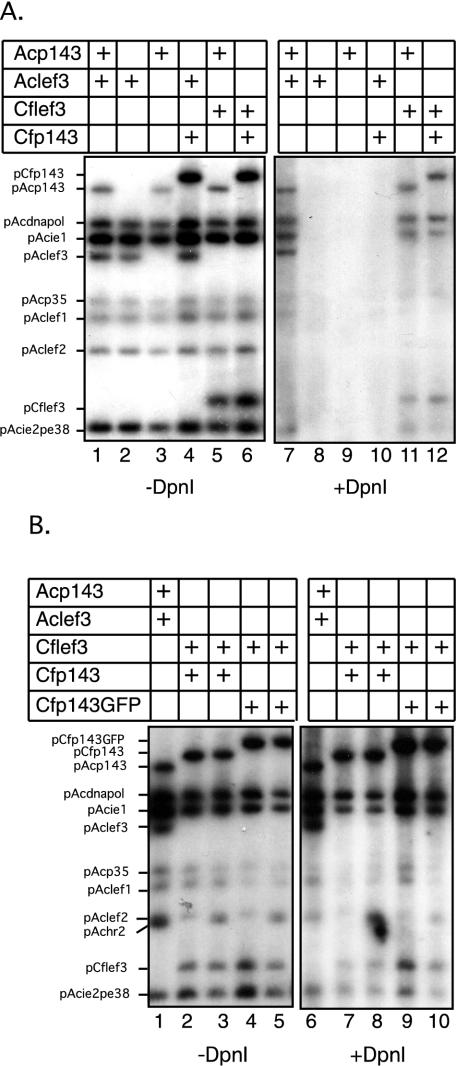

DNA replication assays were performed by transfecting Sf21 cells with a series of plasmids that together express nine AcMNPV genes (ie-1, ie-2, p143, dnapol, lef-1, lef-2, lef-3, pe38, and p35) necessary for viral replication. Total intracellular DNA was harvested at 48 h posttransfection and digested with DpnI to distinguish between unreplicated input plasmid DNA and newly replicated DNA. As we have previously shown (40), when all nine AcMNPV genes are expressed together, they support the replication of any plasmid DNA, including those expressing the viral proteins (Fig. 7). If any of the plasmids, including those expressing P143 or LEF-3, was eliminated from the mixture, no plasmid replication occurred (Fig. 7A, lanes 8 and 9). Replacement of AcMNPV p143 with its CfMNPV homologue did not restore replication function (Fig. 7A, lane 10) but replacement of AcMNPV lef-3 by its CfMNPV homologue did (Fig. 7A, lane 11). Replacement of both AcMNPV p143 and lef-3 genes with their CfMNPV homologues also restored plasmid DNA replication (Fig. 7A, lane 12). These results demonstrated that CfMNPV LEF-3 did interact with either AcMNPV P143 or CfMNPV P143 and complemented viral DNA replication in the presence of the other AcMNPV genes. However, CfMNPV P143 alone did not support plasmid DNA replication in the presence of the AcMNPV gene products. Because the immunofluorescence data discussed above demonstrated that CfMNPV P143 fluorescence was not detectable in the nuclei of cells expressing AcMNPV LEF-3, these results suggest that only a small fraction of the expressed P143 is required to support DNA replication in the nucleus. The immunofluorescence analysis was done with a plasmid that expressed a P143-GFP fusion protein, so we confirmed the functionality of this fusion protein in DNA replication by replication assays. The plasmid pIE1hrCfp143GFP worked as well as a plasmid expressing normal CfMNPV P143 in supporting DNA replication (Fig. 7B, lanes 9 and 10). Thus, these data show for the first time that cross species complementation of P143 in baculovirus transient replication assays can occur, even with distantly related NPVs, if P143 is correctly transported to the nucleus.

FIG. 7.

Transient plasmid DNA replication in the presence of heterologous P143 and LEF-3 proteins. Sf21 cells were transfected with a collection of plasmids, which together expressed the AcMNPV genes necessary for plasmid DNA replication (ie-1, dnapol, lef-1, lef-2, p35, pe38, and ie-2) except p143 and lef-3. In separate transfections, this library was supplemented with plasmids expressing the AcMNPV p143 (Acp143), AcMNPV lef-3 (Aclef3), CfMNPV p143 (Cfp143) or CfMNPV lef-3 (Cflef3) genes. Following incubation for 48 h, total intracellular DNA was prepared and digested with EcoRI (−DpnI) to linearize the plasmids or with EcoRI and DpnI (+DpnI) to detect replicated plasmid DNA. Southern blots of these restriction digestion DNA preparations were probed with labeled pUC19 DNA. Replication of input plasmid DNA was detected in the presence of plasmidsexpressing AcMNPV P143 and LEF-3, CfMNPV P143 and LEF-3, and AcMNPV P143 and CfMNPV LEF-3 (A). Similar assays were also done with a plasmid expressing the CfMNPV P143-GFP fusion protein (B). This protein also supported plasmid DNA replication in the presence of CfMNPV LEF-3.

DISCUSSION

The baculovirus protein P143 was first shown to be essential for viral replication by analysis of a temperature sensitive AcMNPV mutant defective in viral DNA replication (13, 29). We later showed that another viral protein, LEF-3, identified as a single-stranded DNA binding protein (14) with DNA-destabilizing properties (33), was an essential transporter for localizing AcMNPV P143 to the nuclei of infected cells (39). We predicted that a major function of P143 would be to provide DNA unwinding activity during viral DNA replication (29). The helicase activity of P143 has recently been confirmed (32). There is also some evidence to suggest that P143 may play a role in species specificity of virus infection. Substitution of as few as two amino acids within a specific region of P143 between the very closely related baculoviruses AcMNPV and BmNPV altered the replication efficiency of AcMNPV in B. mori cells (3, 17). However, the basis of the block of AcMNPV replication in B. mori cells was not investigated. To investigate the possible role of P143 in regulating viral DNA replication in other host species, we identified, cloned and sequenced p143 and lef-3 from CfMNPV. The CfMNPV P143 predicted amino acid sequence was highly similar to that of OpMNPV (85% identical) but only 58% identical with that of AcMNPV P143. LEF-3 is less highly conserved among baculoviruses, but CfMNPV LEF-3 was still most similar to the OpMNPV homologue (75% identical) and only 39% identical with AcMNPV LEF-3. The transcription patterns of both the CfMNPV p143 and lef-3 genes were consistent with their being early genes, essential for viral DNA replication. Both gene transcripts were detectable by 6 h postinfection, well before the time of increase in CfMNPV DNA replication (25). In addition, the transcripts for both genes increased in abundance up to 48 h postinfection, suggesting that they were transcribed for extended periods in Cf124T cells. These data support our previous studies, which revealed a slower replication cycle of CfMNPV in these cells than AcMNPV in Sf21 cells (25). The similarity between the CfMNPV genes and their OpMNPV homologues was also evident in the sequence and location of their transcription start sites. We identified the CfMNPV LEF-3 transcription start site by 5′ RACE to be located 25 nucleotides downstream of a potential TATA box sequence starting at the first A in the sequence AACATTGA. This corresponds exactly with the identified OpMNPV LEF-3 start site (1). The AcMNPV LEF-3 transcription start site was mapped about 14 nucleotides downstream of this region (23). Two CfMNPV P143 transcription start sites were identified by 5′ RACE, at 188 and 371 nucleotides upstream of the translation start codon. Both of these sites represent conserved regions in OpMNPV and AcMNPV, although the AcMNPV p143 transcription start site was mapped about 30 nucleotides closer to the translation start codon (30). Together, these results support our previous hypothesis that the promoter structures of genes involved in viral DNA replication are different from those of other early genes, many of which have transcription starts sites beginning with CAGT, likely reflecting different regulatory pathways for these genes. A CAGT sequence located 10 nucleotides downstream of the mapped p143 transcription start site is also present in OpMNPV. However, our 5′ RACE analysis indicated that this site was not used as a transcription start site.

Antibodies raised against CfMNPV LEF-3 reacted with a 44-kDa polypeptide expressed in virus-infected Cf124T cells from about 8 h postinfection, correlating well with the expression of the CfMNPV lef-3 transcript. Immunofluorescence studies showed that CfMNPV LEF-3 was always observed in the nucleus indicating that it carries the necessary signals required for nuclear localization. Unfortunately, our polyclonal antibodies directed against AcMNPV P143 did not cross-react with the CfMNPV gene product and we have had no success at overexpressing this protein to prepare CfMNPV P143-specific antibodies so we could not study CfMNPV P143 expression directly in virus-infected cells. We developed an alternative method by preparing a plasmid which expressed a CfMNPV P143-GFP fusion protein. The expression of the fusion protein was monitored by fluorescence of the GFP reporter component. These studies revealed that P143 remained cytoplasmic when expressed on its own, but was nuclear when coexpressed with CfMNPV LEF-3 or in CfMNPV-infected Cf124T cells. These biochemical data confirm our previous immunofluorescence data that the nuclear localization of P143 requires the presence of LEF-3 although the specific role that LEF-3 plays in this process is unknown. Because LEF-3 may exist as a homotrimer (11), it is too large to diffuse through nuclear pores on its own, so it likely carries a nuclear localization target signal, which provides a signal sequence for LEF-3 interaction with cellular importin complexes for delivery to the nuclear pores and nuclear import (16). Because P143 does not appear to carry a nuclear signal sequence, the interaction between P143 and LEF-3 must establish a complex that is then recognized by this host transporting machinery. We have initiated studies to identify possible cellular components of this complex.

CfMNPV P143-GFP was also localized to the nuclei of Sf21 cells in the presence of CfMNPV LEF-3, suggesting that no C. fumiferana-specific cell factors are essential for the correct translocation of the P143-LEF-3 complex to the nucleus. However, AcMNPV LEF-3 or whole AcMNPV virus infection resulted in cytoplasmic fluorescence of CfMNPV P143-GFP in Sf21 cells, suggesting that virus species specificity is important to the interaction of P143 and LEF-3. Other researchers have attempted to rescue AcMNPV P143 with a heterologous P143 from OpMNPV, SeMNPV or Trichoplusia ni GV, but these experiments were unsuccessful (2, 5, 15). In these cases, rescue of P143 function was monitored by transient DNA replication assays. Based on those published results, we hypothesized that one reason these experiments failed was the lack of the homologous LEF-3, which would recognize and transport P143 to its site of action in the nucleus. Our replication assay results confirmed this hypothesis. As expected, CfMNPV P143 did not rescue DNA replication in the presence of all the other AcMNPV replication genes. However, replacing both AcMNPV P143 and LEF-3 with their CfMNPV counterparts restored the replication function in the presence of the remainder of the AcMNPV replication proteins. These results suggest that a major factor in baculovirus replication is represented by the P143-LEF-3 complex. Our transient replication assays demonstrated that replacement of AcMNPV LEF-3 with CfMNPV LEF-3 also restored replication function. This suggests that there are less stringent requirements for P143-LEF-3 interaction in nuclear localization than for the function of P143, possibly in conjunction with LEF-3, during DNA replication. However, no specific role of LEF-3 in baculovirus DNA replication has been demonstrated, so it is still not clear what its actual function is. We also confirmed that adding the GFP tag to P143 did not disrupt its ability to function during viral DNA replication since this construct was still able to rescue DNA replication in the transient assays. These results demonstrate that this fusion protein will be a useful tool for investigating the in vivo localization of P143 during viral replication. We are continuing to investigate the interaction of these and other viral proteins in the assembly of a functional replication complex in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Don Back for the Northern blotting, Linda Guarino for the monoclonal antibody against AcMNPV LEF-3, and Marilyn Garrett and Colin Inalsingh for technical assistance.

This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahrens, C. H., C. Carlson, and G. F. Rohrmann. 1995. Identification, sequence, and transcriptional analysis of lef-3, a gene essential for Orgyia pseudotsugata baculovirus DNA replication. Virology 210:372-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahrens, C. H., and G. F. Rohrmann. 1996. The DNA polymerase and helicase genes of a baculovirus of Orgyia pseudotsugata. J. Gen. Virol. 77:825-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argaud, O., L. Croizier, M. López-Ferber, and G. Croizier. 1998. Two key mutations in the host-range specificity domain of the p143 gene of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus are required to kill Bombyx mori larvae. J. Gen. Virol. 79:931-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell, S. P., and A. Dutta. 2002. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71:333-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bideshi, D. K., and B. A. Federici. 2000. The Trichoplusia ni granulovirus helicase is unable to support replication of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus in cells and larvae of T. ni. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1593-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell, M. J. 1995. Lipofection reagents prepared by a simple ethanol injection technique. BioTechniques 18:1027-1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carstens, E. B. 1982. Mapping the mutation site of an Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus polyhedron morphology mutant. J. Virol. 43:809-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cartier, J. L., P. A. Hershberger, and P. D. Friesen. 1994. Suppression of apoptosis in insect cells stably transfected with baculovirus p35: dominant interference by N-terminal sequences p351-76. J. Virol. 68:7728-7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chomczynski, P. 1993. A reagent for the single-step simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA and proteins from cell and tissue samples. BioTechniques 15:532-537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162:156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans, J. T., and G. F. Rohrmann. 1997. The baculovirus single-stranded DNA binding protein, LEF-3, forms a homotrimer in solution. J. Virol. 71:3574-3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans, J. T., G. S. Rosenblatt, D. J. Leisy, and G. F. Rohrmann. 1999. Characterization of the interaction between the baculovirus ssDNA-binding protein (LEF-3) and putative helicase (P143). J. Gen. Virol. 80:493-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon, J. D., and E. B. Carstens. 1984. Phenotypic characterization and physical mapping of a temperature-sensitive mutant of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus defective in DNA synthesis. Virology 138:69-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hang, X., W. Dong, and L. A. Guarino. 1995. The lef-3 gene of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus encodes a single-stranded DNA-binding protein. J. Virol. 69:3924-3928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heldens, J. G. M., Y. Liu, D. Zuidema, R. W. Goldbach, and J. M. Vlak. 1997. Characterization of a putative Spodoptera exigua multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus helicase gene. J. Gen. Virol. 78:3101-3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jans, D. A., C-Y. Xiao, and M. H. C. Lam. 2000. Nuclear targeting signal recognition: a key control point in nuclear transport? BioEssays 22:532-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamita, S. G., and S. Maeda. 1996. Abortive infection of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus in Sf-9 cells after mutation of the putative DNA helicase gene. J. Virol. 70:6244-6250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamita, S. G., and S. Maeda. 1997. Sequencing of the putative DNA helicase-encoding gene of the Bombyx mori nuclear polyhedrosis virus and fine-mapping of a region involved in host range expansion. Gene 190:173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koetsier, P. A., J. Schorr, and W. Doerfler. 1993. A rapid optimized protocol for downward alkaline Southern blotting of DNA. BioTechniques 15:260-262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kool, M., C. H. Ahrens, R. W. Goldbach, G. F. Rohrmann, and J. M. Vlak. 1994. Identification of genes involved in DNA replication of the Autographa californica baculovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:11212-11216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koonin, E. V. 1993. A common set of conserved motifs in a vast variety of putative nucleic acid-dependent ATPases including MCM proteins involved in the initiation of eukaryotic DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:2541-2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laufs, S., A. Lu, L. K. Arrell, and E. B. Carstens. 1997. Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus p143 gene product is a DNA-binding protein. Virology 228:98-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, Y., A. L. Passarelli, and L. K. Miller. 1993. Identification, sequence, and transcriptional mapping of lef-3, a baculovirus gene involved in late and very late gene expression. J. Virol. 67:5260-5268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, G., and E. B. Carstens. 1999. Site-directed mutagenesis of the AcMNPV p143 gene: effects on baculovirus DNA replication. Virology 253:125-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, J. J., and E. B. Carstens. 1993. Infection of Spodoptera frugiperda and Choristoneura fumiferana cell lines with the baculovirus Choristoneura fumiferana nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Can. J. Microbiol. 39:932-940. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu, J. J., and E. B. Carstens. 1995. Identification, localization, transcription and sequence analysis of the Choristoneura fumiferana nuclear polyhedrosis virus DNA polymerase gene. Virology 209:538-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, J. J., and E. B. Carstens. 1996. Identification, molecular cloning, and transcription analysis of the Choristoneura fumiferana nuclear polyhedrosis virus spindle-like protein gene. Virology 223:396-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu, A. 1993. Nucleotide sequence, transcriptional mapping, regulation, and overexpression of an essential early baculovirus gene. Ph.D. thesis. Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

- 29.Lu, A., and E. B. Carstens. 1991. Nucleotide sequence of a gene essential for viral DNA replication in the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology 181:336-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu, A., and E. B. Carstens. 1992. Transcription analysis of the EcoRI D region of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus identifies an early 4-kilobase RNA encoding the essential p143 gene. J. Virol. 66:655-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu, A., and L. K. Miller. 1995. The roles of eighteen baculovirus late expression factor genes in transcription and DNA replication. J. Virol. 69:975-982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDougal, V. V., and L. A. Guarino. 2001. DNA and ATP binding activities of the baculovirus DNA helicase P143. J. Virol. 75:7206-7209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mikhailov, V. S. 2000. Helix-destabilizing properties of the baculovirus single-stranded DNA-binding protein (LEF-3). Virology 270:180-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu, W., J. J. Liu, and E. B. Carstens. 1996. Studies of Choristoneura fumiferana nuclear polyhedrosis virus gene expression in insect cells. Virology 217:564-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith, D. B., and K. S. Johnson. 1988. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene 67:31-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Staggs, D. R., D. W. Burton, and L. J. Deftos. 1996. Importance of liposome complexing volume in transfection optimization. BioTechniques 21:792-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tjia, S. T., E. B. Carstens, and W. Doerfler. 1979. Infection of Spodoptera frugiperda cells with Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. II. The viral DNA and the kinetics of its replication. Virology 99:391-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu, Y., and E. B. Carstens. 1996. Initiation of baculovirus DNA replication: early promoter regions can function as infection-dependent replicating sequences in a plasmid-based replication assay. J. Virol. 70:6967-6972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu, Y., and E. B. Carstens. 1998. A baculovirus single-stranded DNA binding protein, LEF-3, mediates the nuclear localization of the putative helicase P143. Virology 247:32-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu, Y., G. Liu, and E. B. Carstens. 1999. Replication, integration, and packaging of plasmid DNA following cotransfection with baculovirus viral DNA. J. Virol. 73:5473-5480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]