Abstract

Objective

Previously we identified palmitoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC 16:0), as well as linoleoyl-, arachidonoyl- and oleoyl-LPC (LPC 18:2, 20:4 and 18:1) as the most prominent LPC species generated by the action of endothelial lipase (EL) on high-density lipoprotein (HDL). In the present study, the impact of EL and EL-generated LPC on interleukin-8 (IL-8) synthesis was examined in vitro in primary human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) and in mice.

Methods and Results

Adenovirus-mediated overexpression of the catalytically active EL, but not its inactive mutant, increased endothelial synthesis of IL-8 mRNA and protein in a time- and HDL-concentration-dependent manner. While LPC 18:2 was inactive, LPC 16:0, 18:1 and 20:4 promoted IL-8 mRNA- and protein-synthesis, differing in potencies and kinetics. The effects of all tested LPC on IL-8 synthesis were completely abrogated by addition of BSA and chelation of intracellular Ca2+. Underlying signaling pathways also included NFkB, p38-MAPK, ERK, PKC and PKA. In mice, adenovirus-mediated overexpression of EL caused an elevation in the plasma levels of MIP-2 (murine IL-8 analogue) accompanied by a markedly increased plasma LPC/PC ratio. Intravenously injected LPC also raised MIP-2 plasma concentration, however to a lesser extent than EL overexpression.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that EL and EL-generated LPC, except of LPC 18:2, promote endothelial IL-8 synthesis, with different efficacy and kinetics, related to acyl-chain length and degree of saturation. Accordingly, due to its capacity to modulate the availability of the pro-inflammatory and pro-adhesive chemokine IL-8, EL should be considered an important player in the development of atherosclerosis.

Abbreviations: LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; EL, endothelial lipase; 16:0 LPC, palmitoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine; 18:2 LPC, linoleoyl-LPC; 20:4 LPC, arachidonoyl-LPC; 18:1 LPC, oleoyl-LPC; HAEC, human aortic endothelial cells; AA, arachidonic acid; NEFA, nonesterified fatty acids; FFA, free fatty acids; BSA, bovine serum albumin; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; NFκB, nuclear factor kappa B; 2-AG, 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol; p38-MAPK, p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase; ERK, extracellular regulated kinase; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; MIP-2, macrophage inflammatory protein 2-alpha; GFX, GF109203X

Keywords: Endothelial lipase (EL), Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), IL-8, Endothelial cells, Atherosclerosis, Adenovirus, Acyl-chain

1. Introduction

EL is a member of the triglyceride (TG) lipase gene family localized on the surface of vascular endothelial cells [1,2]. By virtue of its phospholipase activity, EL cleaves HDL-phosphatidylcholine (HDL-PC) liberating free fatty acids (FFA) and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) [3,4]. Experiments in genetically modified mice, either overexpressing or lacking functional EL revealed an inverse relationship between plasma HDL cholesterol level and EL expression [5,6]. The capacity of EL to decrease HDL plasma concentrations together with its ability to promote monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells [7], suggest EL to be an atherogenic enzyme. However, the results obtained from atherosclerosis studies using EL knock out (ko) models were conflicting, with decreased aortic atherosclerosis in double EL-/apoE-ko mice [8] and no differences in a separate study where both EL-/apoE-ko and EL-/LDL receptor-ko mice were used [9].

In a previous study, we demonstrated that in addition to the well characterized 1-palmitoyl (16:0) LPC, EL generates substantial amounts of unsaturated LPC 18:1, 18:2 and 20:4, respectively [10]. Saturated 16:0 LPC represents the well characterized standard LPC, shown to induce various signaling pathways thereby promoting the production of inflammatory molecules, including IL-8, in human vascular endothelial cells [11].

The physiological concentrations of LPC in body fluids ranges between 100 and 170 μM [12] with even millimolar levels in hyperlipidemic subjects [13]. LPC in plasma are distributed between albumin and other carrier serum proteins and lipoproteins [14,15]. Furthermore, free LPC may transiently exist due to an excessive lipolysis when the concentrations of FFA and LPC locally exceed the binding capacity of albumin and carrier proteins [15].

Interleukin-8 (IL-8) is a pro-inflammatory chemokine which acts as an important chemoattractant for neutrophils and monocytes, and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [16]. It is synthesized by various types of vascular cells, including endothelial cells, where inflammatory stimuli and bioactive lipids have been shown to augment its production [11,17].

Since studies investigating the impact of LPC on endothelial chemokine secretion used exclusively 16:0 LPC [11,18] nothing is known about the impact of length and degree of saturation of the LPC-acyl chain on IL-8 production in vascular endothelial cells, the main source of EL.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine the effect of EL on the generation of IL-8 and to compare the impact of the “standard” 16:0 LPC with that of unsaturated LPC, abundantly generated by EL, on IL-8 production in primary human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) and in vivo in mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. LPC

LPC 16:0, 18:1, 18:2 and 20:4 were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. LPC were dissolved and stored at −20 °C in chloroform/methanol under argon atmosphere. Required amounts of LPC were dried under a stream of nitrogen or argon and re-dissolved in PBS (pH 7.4) for cell culture experiments or in pyrogen-free saline (NaCl) for in vivo experiments.

2.2. Cell culture

Human primary aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) were obtained from Lonza and maintained in endothelial cell growth medium [EGM-MV Bullet Kit = EBM medium + growth supplements + FCS (Lonza)] supplemented with 50 IU/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were cultured in gelatine-coated dishes at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere and were used for experiments from passage 5 to 10. Cells were seeded (75000/well) in 12-well plates 48 h before exposure to HDL or LPC.

2.3. Isolation of human HDL

HDL (subclass 3, d = 1.125–1.21 g/ml) was prepared by sequential ultracentrifugation of plasma obtained from normolipidemic blood donors as described previously [19].

2.4. Adenovirus generation

Adenoviruses (Ad) encoding human EL (EL), catalytically inactive mutant EL (MUT) containing Asp192 → Asn substitution and bacterial β-galactosidase (LacZ) were prepared exactly as described previously [19].

2.5. Adenoviral infection of HAEC

HAEC (75,000/well) were seeded in 12-well plates. Forty-eight hours later, confluent cells were infected with EL-Ad, EL-MUT-Ad or LacZ-Ad at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 in endothelial basal medium (EBM) without fetal calf serum (FCS). Following a 2 h-infection period, cells were grown in complete EBM for additional 24 h. Thereafter, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with EBM medium without supplements and without serum for 3 h. This medium is referred to as a serum-free medium throughout the text. Thereafter, medium was removed and replaced with fresh serum-free medium supplemented with indicated concentrations of HDL.

2.6. LPC treatment of HAEC

2.6.1. LPC cytotoxycity:

Initial time- and concentration-dependent experiments revealed that in a serum-free medium in the absence of bovine serum albumin (BSA) all tested LPC at concentrations up to 10 μM were not toxic to HAEC (for incubations up to 8 h), as determined by monitoring the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), using a cytotoxicity detection kit (LDH) (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

2.6.2. Experiments under serum-free conditions:

48 h after plating, cells were washed with PBS, and incubated in serum-free medium for 3 h. Thereafter, medium was removed and replaced with fresh serum-free medium supplemented with different concentrations of LPC. In some experiments as indicated in the respective figure legends, LPC were applied along with BSA at a molar ratio of 1:1 and 5:1, respectively.

2.6.3. Experiments in the presence of serum:

Here, washing steps and preincubation steps with serum-free medium were omitted. Due to the presence of BSA and other binding proteins in serum, 100 μM LPC was applied for the incubation in serum-containing medium (5%) (to ascertain the presence of free LPC).

Medium was collected in pre-chilled tubes following exposure to HDL or LPC, centrifuged and used for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay and IL-8 quantification. Cells were washed with PBS and lysed for RNA or protein isolation.

2.7. Pharmacological inhibitors

HAEC were pre-treated with respective pharmacological inhibitors or vehicle (DMSO) for 45 min in serum-containing medium before the addition of fresh FCS-medium containing LPC. Following inhibitors were applied: Bapta/AM (Ca2+ chelator; 10 μM), PDTC (NFκB inhibitor; 30 μM), SB203580 (p38-MAPK inhibitor; 5 μM), PD98059 (ERK inhibitor; 30 μM), GFX (PKC inhibitor; 1 μM), H-89 (PKA inhibitor; 10 μM), genistein/daizein (tyrosin kinase inhibitor/negative control; 100 μM), U-73122/U73343 (PLC inhibitor/negative control; 2 μM each). For treatment with pertussis toxin (PTX) cells were preincubated with 0.1 μg/ml PTX for 17 h. All inhibitors were from Sigma.

2.8. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Please see Supplemental Methods.

2.9. Western blotting

EL expression was examined exactly as described [19]. Please see supplemental Methods for details.

2.10. IL-8 and MIP-2 measurements by ELISA

IL-8 was measured in cell culture media by an ELISA Kit (eBioscience, San Diego, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Protein content of cell culture wells was initially determined to be equal for all treatments.

MIP-2, a mouse IL-8 analogue, was measured in mouse plasma by an ELISA Kit according to manufacturers instructions (Komabiotech, Seoul, Korea).

2.11. Experiments in mice

2.11.1. Intravenous (i.v.) injection of adenovirus

10–12 weeks old male C57Bl/6J mice (5 per group) were injected with 3 × 109 particles of LacZ- or EL-Ad in 100 μl of 0.9% NaCl via tail vein injection. Six hours later, blood was collected from the retroorbital plexus into EDTA-containing tubes and centrifuged. Plasma was stored at −70 °C before analysis of MIP-2 or lipid extraction. The efficiency of EL-overexpression was estimated indirectly by measuring HDL-cholesterol plasma concentration, which was markedly decreased (>50%) in EL-Ad but unaltered in LacZ-Ad injected animals (data not shown).

2.11.2. Injection of LPC

Following a 6 h-fasting period, 10–12 weeks old male C57Bl/6J mice (4–7 per group) were treated with 20 mg/kg LPC in 0.9% NaCl (or NaCl alone) via tail vein injection. Five hours later, blood was collected from the retroorbital plexus, centrifuged immediately and stored at −70 °C for measurements of MIP-2. For both adenovirus- and LPC-vein injection as well as for blood collection, mice were anaesthetized with Isoflurane (Pharmacia & Upjohn SA, Guyancourt, France). Animal experiments were approved by the Austrian Ministry of Education, Science and Culture according to the regulations for animal experimentation.

2.12. Lipid extraction, HPLC and Mass Spectrometry

100 μl of mouse plasma was extracted according to Bligh and Dyer [20] and analysed by HPLC and mass spectrometry (supplemental Methods).

2.13. Statistical analysis

Cell culture experiments were performed at least three times and values are expressed as mean plus SEM. Statistical significance was determined by the Student's unpaired t-test (two-tailed) and with application of Welch's correction, where required. Group differences were considered significant for p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***).

3. Experimental results

3.1. EL-generated lipids promote IL-8 expression in HAEC

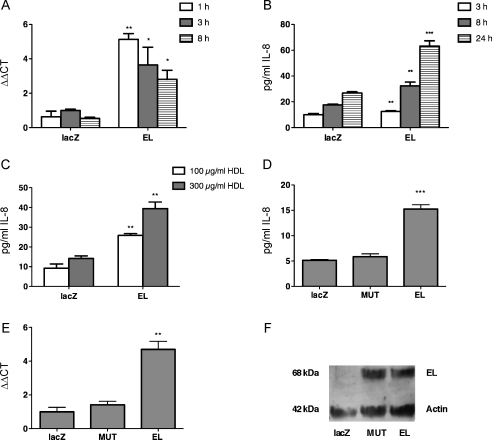

Adenovirus mediated overexpression of EL and subsequent incubation with HDL increased IL-8 mRNA content in HAEC, with the strongest (5-fold) increase detected 1 h after HDL addition (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B, the EL-expressing cells secreted significantly more (1.2-, 1.7- and 2.4-fold, respectively) IL-8 protein, at all tested time points (3, 8 and 24 h, respectively), than LacZ control cells. Secreted IL-8 mass correlated directly with HDL-concentration (Fig. 1C). Enzymatically inactive EL (MUT), expressed at similar level as EL (Fig. 1F), failed to raise IL-8 protein (Fig. 1D) and IL-8 mRNA (Fig. 1E), respectively, arguing for the role of EL-derived lipids in IL-8 upregulation.

Fig. 1.

Overexpression of EL induces IL-8 mRNA and protein expression. LacZ or EL-overexpressing HAEC were incubated in a serum-free medium with 100 μg/ml HDL for the indicated time periods. Subsequently, (A) IL-8 mRNA content was determined by qRT-PCR and (B) IL-8 protein secretion was assessed in cell supernatants by ELISA. Results shown are mean ± SEM of one representative experiment performed in triplicates out of 3 experiments. (C) As in (B) except that HAEC were incubated with 100 μg/ml and 300 μg/ml HDL for 24 h. (D) As in (B) except that in addition to LacZ and EL a catalytically inactive form of EL (MUT) was expressed in HAEC and incubated with HDL for 3 h. (E) As in (A) except that in addition to LacZ and EL, MUT was expressed in HAEC and incubated with HDL for 3 h. (F) Western blot analysis of EL and MUT as well as of ß-actin in HAEC infected with LacZ-, EL- and MUT-Ad.

3.2. EL-generated LPC promote IL-8 expression in HAEC

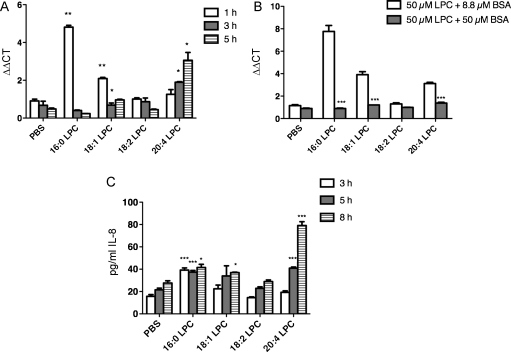

Next we tested the capacity of LPC 16:0, 18:1, 18:2 and 20:4 to induce IL-8 expression. While LPC 16:0 and 18:1 elicited a maximal 5- and 2-fold, respectively, increase in IL-8 mRNA after 1 h of incubation, a maximal 3-fold upregulation was observed at 5 h of incubation with LPC 20:4. LPC 18:2 had no effect on IL-8 mRNA expression (Fig. 2A). The observed LPC-mediated upregulation of IL-8 mRNA could be completely abolished upon addition of equimolar amounts of NEFA-free BSA (50 μM NEFA-free BSA + 50 μM LPC) (Fig. 2B). However, when based on the assumption that one mol of BSA binds 5 mol of LPC [21] the BSA concentration was adjusted to yield roughly 10 μM of free LPC (8.8 μM NEFA-free BSA + 50 μM LPC), the upregulation of IL-8 mRNA could be restored (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

EL-generated LPC induce IL-8 mRNA and protein expression. HAEC were incubated with 100 μM LPC in medium containing 5% FCS for the indicated time points, followed by the determination of (A) IL-8 mRNA abundance by qRT-PCR and (C) IL-8 protein in supernatants by ELISA. (B) HAEC were incubated with 50 μM LPC in serum-free medium containing either 50 μM (equimolar) or 8.8 μM (∼10 μM free LPC) BSA for 1 h. Subsequently, relative IL-8 mRNA abundance was determined by qRT-PCR as described in Section 2. Results shown are mean ± SEM of one representative experiment performed in triplicates out of 3 experiments.

While the 16:0 LPC-elicited IL-8 protein secretion was maximally increased (2.6-fold) after 3 h, a maximal 18:1 LPC-elicited increase (1.3-fold) was achieved after 8 h. In contrast, the 20:4 LPC-elicited IL-8 protein secretion was significantly increased after 5 h (1.9-fold) and 8 h (2.9-fold), respectively (Fig. 2C).

3.3. LPC-elicited IL-8 mRNA upregulation is dependent on intracellular Ca2+ and NFκB

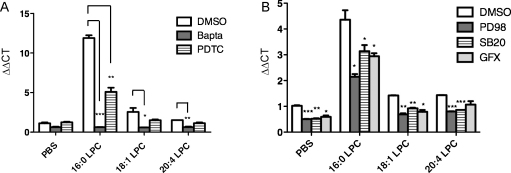

Since 16:0 LPC is known to activate different signaling pathways [11,22], we examined whether the tested LPC differ in the activation of signaling pathways underlying IL-8 mRNA upregulation. As shown in Fig. 3A, the Ca2+ chelator Bapta/AM completely abolished the effect of all LPC on IL-8 mRNA levels. Similarly, the NFκB-inhibitor PDTC partially attenuated the effects of all tested LPC on IL-8 mRNA (albeit statistically significant only for 16:0 LPC) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

LPC induce IL-8 mRNA via Ca2+ and NFkB signaling. (A) HAEC were preincubated with an intracellular Ca2+-chelator (Bapta A/M), a specific NFkB inhibitor (PDTC) or with vehicle (DMSO) for 45 min before they were exposed to 100 μM LPC in medium containing 5% FCS for 1 h. Subsequently, relative IL-8 mRNA abundance was determined by qRT-PCR as described in Section 2. Results shown are mean ± SEM of one representative experiment performed in duplicates out of 3 experiments. (B) As in (A) except that HAEC were preincubated with ERK inhibitor (PD98), p38-MAPK inhibitor (SB20) or PKC inhibitor (GFX).

The inhibitors of p38-MAPK (SB203580), ERK (PD98059), PKC (GFX) and PKA (H-89) reduced the stimulatory effects of all tested LPC; however, they also led to a constitutive reduction in control cells (Fig. 3B). The inhibition of tyrosin-kinases (genistein) and phospholipase C (U-73122) did not have any effect on the IL-8 mRNA upregulation by all tested LPC as compared to the respective negative control inhibitors (daizein and U-73343) (data not shown). Similarly, pertussis toxin (PTX), an inhibitor of the Gi/o-proteins failed to affect the upregulation of IL-8 mRNA by all tested LPC (suppl. Fig. 1).

3.4. EL-derived LPC promote the expression of MIP-2 in vivo

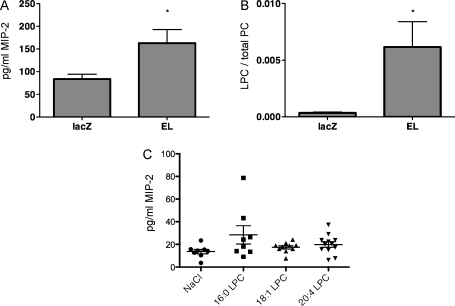

To demonstrate the capacity of EL to elicit expression of IL-8 in vivo, MIP-2 (a mouse analogue of IL-8) was measured in mice upon adenovirus-mediated EL overexpression. As shown in Fig. 4A, the MIP-2 plasma concentrations were significantly higher in EL-overexpressing mice compared with lacZ control mice. Importantly, the LPC/PC ratio was markedly higher in EL than in lacZ control mice (Fig. 4B), clearly demonstrating an efficient generation of EL-derived LPC in vivo. Taken together, these results strongly argue for the role of EL-derived LPC in MIP-2 upregulation. Indeed, as depicted in Fig. 4C, although not statistically significant compared with NaCl controls, MIP-2 plasma values were also increased in mice treated with single LPC, whereby the effects of LPC 16:0 and 20:4 were slightly more pronounced than that of LPC 18:1.

Fig. 4.

Adenovirus mediated EL-overexpression and i.v. injected LPC induce MIP-2 (IL-8 analogue) in mouse plasma. (A) Blood was collected from fed, male C57Bl/6J mice, 6 h after i.v. injection of 3 × 109 virus particles of LacZ- or EL-Ad. MIP-2 plasma values were determined by ELISA as described in Section 2. Values are mean ± SEM of a representative experiment (with 5 animals per group) out of 2 experiments. (B) Plasma LPC and PC contents of mice described in (A) were determined by LC–MS/MS and expressed as a ratio of total LPC and PC species. Values are mean ± SEM of a representative experiment (with 5 animals per group) out of 2 experiments. (C) Following a 6 h fasting period, 8–12 mice per group were injected via tail vein with either 20 mg/kg LPC in a total volume of 100 μl NaCl or NaCl alone. Five hours later, blood was collected from the retroorbital plexus into tubes containing EDTA, followed by immediate centrifugation for the determination of MIP-2 in plasma. Results are mean ± SEM of 2 experiments.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the role of EL and the most prominent EL-generated LPC in the modulation of endothelial IL-8 expression. To our knowledge, no study has so far addressed the effect of EL and LPC other than 16:0 LPC, on the endothelial production of IL-8. The fact that only enzymatically active EL induced IL-8 mRNA and protein in HAEC clearly implicates the EL-generated cleavage products of HDL-phospholipids in IL-8 induction. Since FFA are well known to induce IL-8 expression in endothelial cells [23], the present study focused on the impact of EL-generated LPC.

The LPC concentration of 10 μM in the absence of serum or 100 μM in the presence of 5% FCS used in our study was within the (patho)physiological range of 100 μM–1.7 mM [12,13] and identical to conditions in previous studies examining the impact of LPC 16:0 on the inflammatory response in vascular endothelial cells [11,18]. In line with previous findings [11], 16:0 LPC elicited a rapid and pronounced upregulation of IL-8 mRNA. The 18:1 LPC-elicited IL-8 mRNA induction was also rapid; however, compared with that of 16:0 LPC this effect was much less pronounced, and resulted in a delayed increase in IL-8 protein secretion, which became obvious only after 5–8 h of incubation. The observed delay in IL-8 protein secretion, relative to IL-8 mRNA upregulation might possibly be due to prior protein storage in secretory organelles as described by Knipe et al. [24].

In contrast to a rapid, short-lived IL-8 mRNA increase elicited with the LPC 16:0 and 18:1, the 20:4 LPC-elicited IL-8 mRNA increase was slow-developing and time-dependent, accompanied by a delayed onset of IL-8 protein secretion (Fig. 2A and C). Considering the potency of oxidized phospholipids to induce IL-8, we tested whether the observed, slow-developing 20:4 LPC-elicited IL-8 response reflects the action of oxidized 20:4 LPC generated during the incubation period [25]. As the effect of 20:4 LPC on IL-8 mRNA induction could not be prevented by coincubation with the antioxidant Trolox, oxidative modification of 20:4 LPC was not likely to account for the observed kinetics of IL-8 increase (Suppl. Fig. 2). Alternatively, the slow-developing 20:4 LPC effect on IL-8 expression might be explained by the action of slow-emerging metabolic conversion products of 20:4 LPC, like arachidonic acid (AA), the precursor of eicosanoids, capable of modulating IL-8 expression [26] or 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol (2-AG) capable of affecting IL-8 expression as well [27].

In line with the capacity of LPC 16:0, 18:1 and 20:4 [28] to increase intracellular Ca2+ and to activate NFκB [29], we identified a crucial role for cytosolic Ca2+ and NFκB in IL-8 induction. The differences in IL-8 regulation might reflect the acyl-chain dependent capability of LPC to increase cytosolic Ca2+, as found in our recent study [28]. Since inhibition of p38-MAPK, ERK, PKC and PKA also led to a constitutive reduction of IL-8 in control cells, the respective pathways rather seem to be involved in the basal response and might only play a minor role in the LPC-mediated IL-8 induction. Considering a delayed 20:4 LPC-mediated IL-8 mRNA upregulation we also tested the effects of inhibitors at 4 h. While the impact of p38-MAPK- and ERK-inhibition at 4 h was similar to that observed at 1 h (Fig. 3B), other tested inhibitors were either detrimental to HAEC, or like PDTC (NFκB inhibitor), markedly induced IL-8 mRNA in control cells (not shown). Accordingly, the impact of inhibitors could not be addressed conclusively at 4 h of incubation.

In contrast to previous findings [11] PTX failed to alter the impact of the tested LPC on IL-8 (suppl. Fig. 1). This might be due to a more pronounced contribution of PTX-sensitive pathways to LPC signaling in microvascular endothelial cells than in HAEC [11].

The tested LPC increased the plasma levels of MIP-2, a mouse homolog of IL-8, however, without reaching statistical significance. The reason might be a too low plasma concentration of applied LPC resulting in complete binding and neutralization by serum proteins and consequently reduced bioavailability of the free unbound form, a prerequisite for their biological effects including IL-8 upregulation [11,30] (Fig. 2B).

In contrast to injected LPC, adenovirus-mediated EL overexpression in mice led to a significant increase in MIP-2 accompanied by a marked increase of the LPC/PC ratio in mouse plasma. The more profound effect of EL overexpression as compared to single LPC on MIP-2 plasma levels might be explained by a sustained EL-mediated provision of a mixture of LPC but also FFA, which are established inducers of IL-8. Additionally, due to excessive EL-mediated lipolysis a high plasma concentration of lipolytic products (LPC and FFA) might lead to a saturation of lipid binding domains on albumin and other plasma carrier proteins, yielding increased concentrations of the free LPC, which are capable of triggering biological effects.

Here we show that EL induces endothelial IL-8 expression by the generation of lipolytic products during the enzymatic cleavage of HDL phospholipids. The most prominent EL-generated lipids tested in our study, LPC 16:0, 18:1, 18:2 and 20:4 exhibited different, acyl-chain related potencies and kinetics of IL-8 induction, dependent on intracellular Ca2+ and partially on NFκB. In contrast to in vitro experiments, where IL-8 upregulation reflected response of vascular endothelial cells to EL-lipids, upregulated plasma MIP-2 reflected the induction of various cell types responsive to EL-derived LPC (and FFA).

Taken together, it is conceivable that attenuation of EL-activity, could be a promising strategy for the prevention and treatment of LPC-triggered inflammatory processes in the vasculature.

Conflict of interest statement

A. Heinemann has received research support and consultancy fees from Astra Zeneca.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF; grants P19473-B05 to S.F. and P22521-B18 to A.H.) the Jubilee Foundation of the Austrian National Bank (grants 12778 to S.F. and 11967 to A.H.), and the Lanyar Foundation (grants 328 to S.F. and 315 to A.H.). We thank Martina Ofner, Michaela Tritscher and Birgit Reiter for excellent technical assistance and Isabella Hindler for help with the care of the mice.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Jaye M., Lynch K.J., Krawiec J. A novel endothelial-derived lipase that modulates HDL metabolism. Nat Genet. 1999;21:424–428. doi: 10.1038/7766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirata K., Dichek H.L., Cioffi J.A. Cloning of a unique lipase from endothelial cells extends the lipase gene family. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14170–14175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCoy M.G., Sun G.S., Marchadier D. Characterization of the lipolytic activity of endothelial lipase. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:921–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strauss J.G., Hayn M., Zechner R., Levak-Frank S., Frank S. Fatty acids liberated from high-density lipoprotein phospholipids by endothelial-derived lipase are incorporated into lipids in HepG2 cells. Biochem J. 2003;371:981–988. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishida T., Choi S., Kundu R.K. Endothelial lipase is a major determinant of HDL level. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:347–355. doi: 10.1172/JCI16306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma K., Cilingiroglu M., Otvos J.D. Endothelial lipase is a major genetic determinant for high-density lipoprotein concentration, structure, and metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2748–2753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438039100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kojma Y., Hirata K., Ishida T. Endothelial lipase modulates monocyte adhesion to the vessel wall: a potential role in inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54032–54038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishida T., Choi S.Y., Kundu R.K. Endothelial lipase modulates susceptibility to atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein-E-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45085–45092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406360200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko K.W., Paul A., Ma K., Li L., Chan L. Endothelial lipase modulates HDL but has no effect on atherosclerosis development in apoE−/− and LDLR−/− mice. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:2586–2594. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500366-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gauster M., Rechberger G., Sovic A. Endothelial lipase releases saturated and unsaturated fatty acids of high density lipoprotein phosphatidylcholine. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1517–1525. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500054-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murugesan G., Sandhya Rani M.R., Gerber C.E. Lysophosphatidylcholine regulates human microvascular endothelial cell expression of chemokines. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1375–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabini R.A., Galassi R., Fumelli P. Redusced Na(+)- K(+)-ATPase activity and plasma lysophosphatidylcholine concentrations in diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1994;43:915–919. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.7.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen L., Liang B., Froese D.E. Oxidative modification of low density lipoprotein in normal and hyperlipidemic patients: effect of lysophosphatidylcholine composition on vascular relaxation. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:546–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ojala P.J., Hermansson M., Tolvanen M. Identification of alpha-1 acid glycoprotein as a lysophospholipid binding protein: a complementary role to albumin in the scavenging of lysophosphatidylcholine. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14021–14031. doi: 10.1021/bi061657l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croset M., Brossard N., Polette A., Lagarde M. Characterization of plasma unsaturated lysophosphatidylcholines in human and rat. Biochem J. 2000;345(Pt 1):61–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boisvert W.A. Modulation of atherogenesis by chemokines. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hastings N.E., Simmers M.B., McDonald O.G., Wamhoff B.R., Blackman B.R. Atherosclerosis-prone hemodynamics differentially regulates endothelial and smooth muscle cell phenotypes and promotes pro-inflammatory priming. Am J Physiol – Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1824–C1833. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00385.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kume N., Cybulsky M.I., Gimbrone M.A., Jr. Lysophosphatidylcholine, a component of atherogenic lipoproteins, induces mononuclear leukocyte adhesion molecules in cultured human and rabbit arterial endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1138–1144. doi: 10.1172/JCI115932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strauss J.G., Zimmermann R., Hrzenjak A. Endothelial cell-derived lipase mediates uptake and binding of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles and the selective uptake of HDL-associated cholesterol esters independent of its enzymic activity. Biochem J. 2002;368:69–79. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bligh E.G., Dyer W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y.L., Im Y.J., Ha N.C., Im D.S. Albumin inhibits cytotoxic activity of lysophosphatidylcholine by direct binding. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;83:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou Y., Kim C.H., Chung J.H. Upregulation of endothelial adhesion molecules by lysophosphatidylcholine. Involvement of G protein-coupled receptor GPR4. FEBS J. 2007;274:2573–2584. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stentz F.B., Kitabchi A.E. Palmitic acid-induced activation of human T-lymphocytes and aortic endothelial cells with production of insulin receptors, reactive oxygen species, cytokines, and lipid peroxidation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:721–726. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knipe L., Meli A., Hewlett L., Bierings R., Dempster J., Skehel P., Hannah M.J., Carter T. A revised model for the secretion of tPA and cytokines from cultured endothelial cells. Blood. 2010;116:2183–2191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeh M., Gharavi N.M., Choi J. Oxidized phospholipids increase interleukin 8 (IL-8) synthesis by activation of the c-src/signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT)3 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30175–30181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leik C.E., Walsh S.W. Linoleic acid, but not oleic acid, upregulates production of interleukin-8 by human vascular smooth muscle cells via arachidonic acid metabolites under conditions of oxidative stress. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kishimoto S., Kobayashi Y., Oka S. 2-Arachidonoylglycerol, an endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand, induces accelerated production of chemokines in HL-60 cells. J Biochem. 2004;135:517–524. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riederer M., Ojala P., Hrzenjak A. Acyl chain-dependent effect of lysophosphatidylcholine on endothelial prostacyclin production. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:2957–2966. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M006536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su Z., Ling Q., Guo Z.G. Effects of lysophosphatidylcholine on bovine aortic endothelial cells in culture. Cardioscience. 1995;6:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vuong T.D., Braam B., Willekes-Koolschijn N. Hypoalbuminaemia enhances the renal vasoconstrictor effect of lysophosphatidylcholine. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1485–1492. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.