Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of this study was to assess predictors of MRI-identified septal delayed enhancement mass at the right ventricular (RV) insertion sites in relation to RV remodeling, altered regional mechanics, and pulmonary hemodynamics in patients with suspected pulmonary hypertension (PH).

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Thirty-eight patients with suspected PH were evaluated with right heart catheterization and cardiac MRI. Ten age- and sex-matched healthy volunteers acted as controls for MRI comparison. Septal delayed enhancement mass was quantified at the RV insertions. Systolic septal eccentricity index, global RV function, and remodeling indexes were quantified with cine images. Peak systolic circumferential and longitudinal strain at the sites corresponding to delayed enhancement were measured with conventional tagging and fast strain-encoded MRI acquisition, respectively.

RESULTS

PH was diagnosed in 32 patients. Delayed enhancement was found in 31 of 32 patients with PH and in one of six patients in whom PH was suspected but proved absent (p = 0.001). No delayed enhancement was found in controls. Delayed enhancement mass correlated with pulmonary hemodynamics, reduced RV function, increased RV remodeling indexes, and reduced eccentricity index. Multiple linear regression analysis showed RV mass index was an independent predictor of total delayed enhancement mass (p = 0.017). Regional analysis showed delayed enhancement mass was associated with reduced longitudinal strain at the basal anterior septal insertion (r = 0.6, p < 0.01). Regression analysis showed that basal longitudinal strain remained an independent predictor of delayed enhancement mass at the basal anterior septal insertion (p = 0.02).

CONCLUSION

In PH, total delayed enhancement burden at the RV septal insertions is predicted by RV remodeling in response to increased afterload. Local fibrosis mass at the anterior septal insertion is associated with reduced regional longitudinal contractility at the base.

Keywords: delayed enhancement, fast strain-encoded imaging, MRI, pulmonary hypertension, tagging

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a complex chronic disorder of the pulmonary circulation that has a variety of causes. It is diagnostically and therapeutically challenging and usually has a poor prognosis [1, 2]. PH occurs as a result of remodeling of the distal pulmonary arterioles (and venules in the case of pulmonary venous hypertension), which leads to elevated pressure and resistance in the pulmonary vascular bed and to right ventricular (RV) structural and functional remodeling. High mortality is related to progressive RV dysfunction and failure. Although a definite diagnosis requires invasive measurements obtained at right heart catheterization, reliable noninvasive RV functional and structural monitoring is highly desirable because RV function is the single most important determinant of symptoms and survival [3, 4].

Echocardiography is the tool most widely available for monitoring of patients with PH. However, the technique has several limitations that impair accurate evaluation of RV performance, including operator dependence and patient-dependent echo windows [5, 6]. Cardiac MRI is considered the standard of reference for RV anatomic and functional assessment and is an accurate and reproducible tool for measurement of RV global function [7–9]. MRI myocardial tagging techniques, including conventional tagging and fast strain-encoded imaging, can be used for detailed analysis of regional myocardial deformation [10–12]. Furthermore, scar burden can be accurately quantified with delayed contrast enhancement imaging [13].

Different cardiac MRI patterns of delayed enhancement have been described in association with various myocardial ischemic and nonischemic pathologic condition [14–16]. A number of the pathologic mechanisms are associated with altered regional deformation at the scar sites [17, 18]. The presence of delayed enhancement at the septal RV insertion sites has been described in association with PH, and the extent of the enhancement has been positively correlated with increased after-load and inversely correlated with RV performance [19, 20]. However, the relevance of delayed enhancement and its relation to altered regional mechanics at the corresponding sites has not been investigated, to our knowledge.

We hypothesized that delayed enhancement mass correlates with indexes of RV global and regional morphologic and functional impairment and with pulmonary hemodynamic measurements in patients with known or suspected PH. To investigate this hypothesis, we assessed predictors of MRI-quantified septal delayed enhancement mass at the RV insertion sites in relation to RV remodeling, altered regional mechanics, and pulmonary hemodynamics.

Subjects and Methods

This prospective study was conducted at two major clinical centers after approval by the respective institutional review boards. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants at the two sites.

Patient Sample

From January 2007 through March 2009, a total of 38 consecutively registered patients (29 women, nine men; mean age for all patients, 60.4 ± 11.4 [SD] years; 26 at Johns Hopkins Hospital, 12 at the University Hospital Heidelberg) who were referred for evaluation of clinically known or suspected PH were examined with cardiac MRI and right heart catheterization. PH was defined as mean pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) > 25 mm Hg. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) was defined as PH with a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) ≤ 15 mm Hg, and pulmonary venous hypertension was defined as PH with a PCWP > 15 mm Hg. The underlying cause of PH was determined after comprehensive workup.

A group of 10 healthy age- and sex-matched volunteers (five women, five men; mean age, 55.6 ± 6.0 years) was included in the study. Exclusion criteria were any evidence of known causes of PH (scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell disease, chronic obstructive lung disease, HIV infection, sleep apnea), systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic or nonischemic heart disease, and history of smoking. A lipid profile was obtained and the Framingham risk score calculated for each participant; Framingham 10-year risk > 10% was an exclusion criterion. Control subjects underwent the same MRI protocol as patients with suspected PH. For ethical reasons, the controls did not undergo right heart catheterization.

Right Heart Catheterization

Under fluoroscopic guidance with a multiparameter monitor, right heart catheterization with a pulmonary artery catheter through the right internal jugular vein was performed on all PH patients. Quantified hemodynamic variables included: PCWP, right atrial pressure, mean PAP, systolic and diastolic PAP, cardiac index (thermodilution), pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI), and mixed venous oxygen saturation. All patients completed the right heart catheterization procedure without complications.

MRI

Cine imaging

Twenty-six patients underwent 3-T MRI (TRIO, Siemens Healthcare) and 12 patients 1.5-T MRI (Achieva, Philips Healthcare). A stack of parallel short-axis cine images encompassing both ventricles from base to apex was generated from the four-chamber horizontal long-axis view. Cine images were acquired during short breath-holds with a retrospectively gated turbo FLASH gradient-echo sequence at 3 T (26 patients) and a steady-state free precession sequence at 1.5 T (12 patients). Steady-state free precession cine images were acquired at TR/TE, 2.8/1.4; flip angle, 60–90°; bandwidth, 900–1000 Hz/pixel; number of views per segment, 12. Gradient-echo turbo FLASH cine images were acquired at 46/3.2; flip angle, 15°; bandwidth, 260 Hz/pixel; acceleration factor, 2 (generalized autocalibrating partial parallel acquisition); number of segments, 11. Slice thickness was 8 mm; matrix size, 256 × 192; field of view (FOV), 35 × 35 cm; acquired temporal resolution, 40 milliseconds; number of reconstructed cardiac phases, 30.

Conventional tagging

For quantification of circumferential strain, conventional tagging images were acquired with spatial modulation of magnetization in the short-axis plane. Three slices orthogonal to the interventricular septum at the basal, mid, and apical ventricular levels were generated from the four-chamber cine acquisition. Imaging parameters for 3-T MRI were as follows: 32.8/3.2; flip angle, 10°; number of signals acquired, 1; FOV, 35 × 35 cm; reconstruction matrix size, 256 × 192. For 1.5-T MRI, the parameters were 4.0/1.8; flip angle, 5°; number of signals acquired, 2; FOV, 40 × 40 cm; reconstruction matrix size, 256 × 256; slice thickness, 8 mm; slice spacing, 8 mm.

Fast strain-encoded imaging

Fast strain-encoded imaging is used to quantify myocardial strain and can be performed in a single heartbeat [12]. Because it does not require a breath-hold and thus imaging impediment due to dyspnea is decreased, this technique is useful in the evaluation of patients with PH. Strain-encoded imaging relies on modified 1:1 spatial modulation of magnetization tagging pulse sequence that is an extension of the stimulated echo acquisition mode sequence [12]. In the strain-encoded imaging sequence, the tag planes are parallel to the image plane. This configuration contrasts to that of conventional tagging, in which tag planes are orthogonal [21]. Myocardial deformation through the cardiac cycle changes the local frequency of the tags, changing the regional signal intensity of the images depending on the modulation frequency. The resulting images are encoded with strain values of the myocardial deformation. By combining localized field excitation, interleaved tuning, and spiral readout are for image acquisition, cine real-time strain-encoded images covering the whole cardiac cycle can be acquired in a single heartbeat (fast strain-encoded imaging) [12].

For quantification of longitudinal strain at the RV insertion sites, non-breath-hold fast strain-encoded imaging was performed in the short-axis plane. Three slices were acquired at the same locations used for conventional tagging with the following parameters for all patients: 9.2/0.8; temporal resolution, 29 milliseconds; flip angle, 30°; slice thickness, 10 mm; slice spacing, 0–4 mm; FOV, 25.6 × 25.6 cm; reconstruction matrix size, 64 × 64; in-plane spatial resolution, 4 × 4 mm; acquisition duration, 1 second.

Delayed enhancement imaging

With a 2D inversion recovery phase-sensitive fast gradient-echo sequence, delayed enhancement images were acquired at the same slice locations as the short- and long-axis cine images. Imaging was performed 10 minutes after administration of 0.2 mmol/kg of gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist, Bayer Healthcare). Parameters for 3-T MRI were as follows: 8.6/3.4; flip angle, 25°; FOV, 35 × 35 cm; reconstruction matrix size, 256 × 156; slice thickness, 10 mm; slice spacing, 0 mm. For 1.5-T MRI the parameters were as follows: 3/1.06; flip angle, 15°; FOV, 35 × 35 cm; reconstruction matrix size, 256 × 256; slice thickness, 10 mm; slice spacing, 0 mm. Inversion time was adjusted for each patient to null the normal myocardium. The typical inversion time ranged from 200 to 350 milliseconds.

Image Analysis

Cine short-axis image analysis

For quantification of global ventricular function, short-axis cine images were analyzed with QMASS software (version 6.2.1, Medis). The end-diastolic phase was defined as the largest ventricular volume, and the end-systolic phase was defined as the smallest left ventricular (LV) volume. Epicardial and endocardial ventricular borders were manually contoured by a trained radiologist for quantification of ventricular mass and functional indexes. Quantified indexes included end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes, ejection fraction, stroke volume, cardiac output, and end-diastolic mass. All indexes were normalized to body surface area. Ventricular mass index (RV end-diastolic mass divided by LV end-diastolic mass) was derived for all patients. Systolic eccentricity index was quantified at the midbasal level as described by Ryan et al. [22]. The measurements used to calculate the eccentricity index, a measure of septal displacement, were made in the short-axis view at end-systole. This index was calculated with the equation D1 / D2, where D1 is the minor-axis dimension perpendicular to and bisecting the septum and D2 is the minor-axis dimension of the left ventricle parallel to the septum. In addition, diastolic frames were used to quantify septomarginal trabecular mass. The septomarginal trabecula is an RV muscular band originating from the interventricular septum near the base of the heart near the anterior RV attachment site [23]. Septomarginal trabecular mass has been found to correlate with the severity of PH [24].

Delayed enhancement

A consensus reading was obtained from two radiologists (8 and 4 years of experience in cardiac imaging) blinded to the right heart catheterization data. Both readers visually identified areas of septal delayed enhancement. Hyperenhanced regions at the anterior and posterior RV insertion sites at the LV septum were manually contoured on each short-axis slice, yielding delayed enhancement volume. The volume of delayed enhancement, calculated with the QMASS software, was converted to delayed enhancement mass through multiplication by myocardial density (1.05 g/cm3) [19]. The delayed enhancement masses at the insertion sites were summed to yield scar burden at the basal, mid, and apical ventricular levels.

Tagging and fast strain-encoded imaging analysis

Tagging and fast strain-encoded short-axis images were analyzed with HARP and SENC software (Diagnosoft) to quantify circumferential and longitudinal strain at the septal RV insertion sites, repectively. For both tagging and fast strain-encoded image analysis, regions of interest were placed at each insertion site to quantify the peak systolic strain (at areas corresponding to delayed enhancement regions) at the basal, mid, and apical ventricular levels. Peak systolic circumferential and longitudinal strain, expressed as percentage shortening (negative strain), were calculated from the strain time curves generated at each insertion point. Myocardial strain is defined as the percentage change in tissue length from the length in the resting state at end-diastole (L0) to the length after myocardial contraction at peak-systole (L), as follows:

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed with SPSS software (version 16.0, SPSS). Data are presented as median and 25th to 75th percentile range. Correlations between delayed enhancement mass, right heart catheterization hemodynamics, and global and regional cardiac function parameters were explored with Spearman's rho coefficients. Multiple-group comparisons were tested with the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney test for intergroup comparisons when the Kruskal-Wallis yielded a significant difference. Fisher's least significant difference technique was used to maintain the alpha level with multiple comparisons [25]. Differences in total delayed enhancement mass based on cause of PH in the two major groups comprising our patient sample—those with idiopathic PAH and those with scleroderma-related PAH—were tested by Mann-Whitney test. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to assess the relation between total delayed enhancement mass and mean PAP derived at right heart catheterization, cardiac MRI–derived RV function parameters, ventricular mass index (RV mass divided by LV mass), and eccentricity index. The Mann-Whitney test was used for regional strain comparison between PH and control groups. Comparison of correlation coefficients of the 1.5-T and 3-T subgroups was performed with the Z test for the equality of the two correlations after Fisher r-to-Z transformation. A value of p < 0.05 was generally considered significant.

Results

Among 38 patients who underwent right heart catheterization, 32 (84%) were found to have PH (24 women, eight men; mean PAP, 47 ± 13 mm Hg). The underlying causes of PH included idiopathic PAH in 13 cases, scleroderma-related PAH in 15 cases, and venous PH in four cases. As expected, compared with healthy controls, PH patients had reduced RV function and greater RV remodeling as denoted by increased ventricular mass index (p < 0.001) and septomarginal trabecular mass (p < 0.001). LV functional analysis revealed a significantly lower LV end-systolic volume index (Table 1). Similarly, PH patients had lower RV ejection fraction, higher septomarginal trabecular mass index, and higher ventricular mass index than patients with suspected but absent PH. However, no significant difference was noted between the latter group and healthy subjects (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics, Hemodynamics, and Ventricular Function

| Characteristic |

Patients With PH (n = 32) |

Patients Without PH (n = 6) |

Controls (n = 10) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 64.0 (53.2–68.0) | 59.0 (53.7–67.5) | 54.5 (50.75–58.0) | 0.17 |

| No. of women | 24 | 5 | 5 | 0.25 |

| Mean pulmonary artery pressure (mm Hg) | 45.0 (39.2–52.75)a | 17.5 (16.5–20.0)a | < 0.001 | |

| Systolic pulmonary artery pressure (mm Hg) | 79 (62–85)a | 29.0 (27.0–36.2)a | < 0.001 | |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (mm Hg) | 10 (7.2–11.7) | 7.5 (5.7–8.5) | 0.06 | |

| Pulmonary vascular resistive index (dyne s/cm5/m2) | 1,066.9 (642.3–1,496.9)a | 236.0 (208.5–384.7)a | < 0.001 | |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 2.4 (2.1–3.2) | 3.0 (2.4–4.0) | 0.15 | |

| LV end-diastolic volume index (mL/ m2) | 52.39 (43.3–64.8) | 60.0 (56.9–63.9) | 64.7 (51.7–74.9) | 0.06 |

| LV end-systolic volume index (mL/ m2) | 16.43 (11.7–21.9)b | 18.6 (17.3–21.7) | 22.6 (18.7–29.3)b | 0.05 |

| LV stroke volume (mL) | 65.4 (51.3–76.7) | 63.0 (56.9–75.2) | 75.8 (66.1–84.7) | 0.16 |

| LV stroke volume index (mL/ m2) | 35.2 (29.8–43.9) | 40.3 (36.9–44.2) | 41.3 (36.5–47.5) | 0.09 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 68.7 (62.2–73.4) | 68.9 (64.5–71.0) | 65.4 (58.9–69.4) | 0.27 |

| LV end-diastolic mass index (g/m2) | 56.3 (46.7–65.2)c | 66.6 (55.6–72.3) | 72.8 (62.7–84.4)c | 0.01 |

| RV end-diastolic volume index (mL/m2) | 84.6 (76.2–99.1) | 75.8 (62.3–85.9) | 75.9 (58.3–87.8) | 0.10 |

| RV end-systolic volume index (mL/ m2) | 43.38 (35.7–65.8)b | 31.8 (23.8–47.9) | 34.9 (20.9–42.6)b | 0.03 |

| RV stroke volume (mL) | 64.42 (51.1–73.4) | 62.8 (56.7–74.5) | 75.4 (68.5–84.4) | 0.14 |

| RV stroke volume index (mL/ m2) | 34.9 (30.7–43.3) | 40.1 (36.0–44.0) | 40.9 (36.8–46.8) | 0.08 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 4.83 (3.7–5.6) | 4.7 (4.2–5.2) | 5.4 (4.5–6.1) | 0.25 |

| RV ejection fraction (%) | 44.7 (31.1–52.5)c,d | 56.7 (45.3–61.9)d | 54.5 (50.4–62.0)c | 0.01 |

| RV end-diastolic mass index (g/m2) | 32.9 (23.5–41.4)b,d | 22.9 (18.7–28.8)d | 25.3 (20.0–29.2)b | 0.04 |

| Septomarginal trabecular mass index (g/m2) | 2.4 (1.6–3.9)c,d | 0.9 (0.7–1.6)d | 0.8 (0.5–1.1)c | < 0.001 |

| Ventricular mass index | 0.6 (0.4–0.7)a,c | 0.35 (0.33–0.40)a | 0.3 (0.2–0.3)c | < 0.001 |

| Eccentricity index | 0.77 (0.61–0.87)c,d | 0.96 (0.86–1.0)d | 0.97 (0.93–0.98)c | < 0.01 |

| Total delayed enhancement mass (g) | 4.1 (1.3–7.5)a,c | 0.0 (0.0–0.88)a | 0c | < 0.001 |

Note—Values are median with 25th to 75th percentile range in parentheses. Kruskal-Wallis test was used for multiple-group comparison and was followed by Mann-Whitney test for intergroup comparison when Kruskal-Wallis test showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) all groups. PH = pulmonary hypertension, LV = left ventricular, RV = right ventricular.

p < 0.01 for patients with versus those without PH.

p < 0.05 for patients with PH versus controls.

p < 0.01 for patients with PH versus controls.

p < 0.05 for patients with versus those without PH.

Prevalence and Distribution of Delayed Enhancement

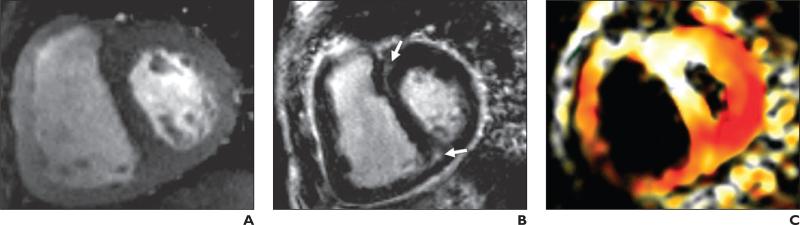

Thirty-one of 32 PH patients (Figs. 1A and 1B) had delayed enhancement at the septal RV insertions, compared with one of six patients with suspected but absent PH (Fig. 2). A significant difference was noted in the mean total delayed enhancement mass of both groups (PH patients, 4.6 ± 3.3 g; patients with suspected but absent PH, 0.6 ± 1.5 g; p = 0.001). Twenty-four of 32 (75%) PH patients had anterior septal insertion delayed enhancement, and 31 of 32 (97%) patients had posterior septal insertion delayed enhancement (p = 0.026). At the anterior septal insertion, delayed enhancement mass at the apex was significantly lower than at the mid and basal ventricular levels after adjustment to total LV mass at the same levels (p = 0.001). At the posterior septal insertion, no significant difference was noted between basal, mid, and apical ventricular levels after adjustment to total LV mass at the corresponding levels (p = 0.06). No delayed enhancement was seen in the control group.

Fig. 1.

72-year-old woman with catheterization-proven pulmonary hypertension; mean pulmonary arterial pressure, 53 mm Hg.

A, Cine gradient-echo basal short-axis view shows thickened right ventricular wall and flattened interventricular septum.

B, Gradient-echo inversion recovery image corresponding to A shows areas of left ventricular delayed enhancement at anterior and posterior right ventricular septal insertions (arrows).

C, Peak systolic fast strain-encoded image corresponding to A and B shows reduced longitudinal strain at anterior right ventricular septal insertion (white) compared with posterior septal insertion (red). On color-coded image, red represents relatively higher longitudinal contractility and white relatively lower longitudinal contractility.

Fig. 2.

59-year-old woman with scleroderma but without pulmonary hypertension; mean pulmonary arterial pressure, 18 mm Hg.

A, Cine gradient-echo basal short-axis view.

B, Gradient-echo inversion recovery image corresponding to A showing no delayed enhancement at right ventricular septal insertions.

C, Peak systolic fast strain-encoded image corresponding to A and B shows normal longitudinal strain at right ventricular attachment sites (red). On color-image, red represents relatively higher longitudinal contractility and white relatively lower longitudinal contractility.

To explore the potential effect of cause of PH on total delayed enhancement mass, we compared total delayed enhancement mass in the two major groups of our patient sample: those with scleroderma-related PAH and those with idiopathic PAH. Patients with idiopathic PAH had a higher total delayed enhancement burden (6.2 ± 3.3 g) than did those with scleroderma-related PAH (3.2 ± 2.7 g) (p = 0.02) without significant differences in cardiac dysfunction or RV hypertrophy. After adjustment to mean PAP, which was significantly higher in idiopathic PAH, a trend toward significantly higher total delayed enhancement mass was still noted in patients with idiopathic PAH (p = 0.06).

Delayed Enhancement and Right Heart Catheterization Hemodynamic Parameters

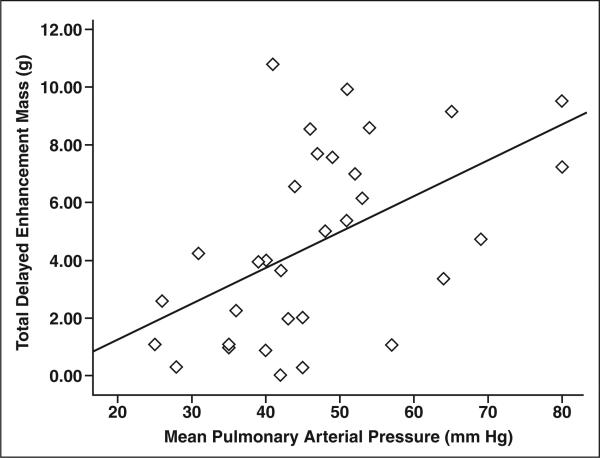

For the 32 PH patients, total delayed enhancement mass in grams correlated significantly with mean PAP (r = 0.55, p = 0.001) (Fig. 3) and PVRI (r = 0.43, p = 0.01). In addition, a negative correlation was found between total delayed enhancement mass and cardiac index (–0.50, p = 0.004) (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Scatterplot shows significant direct correlation between total delayed enhancement mass and mean pulmonary arterial pressure (r = 0.55, p < 0.01) in all patients with pulmonary hypertension (n = 32).

TABLE 2.

Correlation Between Total Delayed Enhancement Mass and Right Heart Catheterization and MR Global Function Indexes in Patients With Pulmonary Hypertension (n = 32)

| Parameter |

r |

p |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 0.07 | 0.69 |

| Mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 0.55 | 0.001 |

| Systolic pulmonary arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 0.5 | 0.006 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (mm Hg) | 0.12 | 0.49 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistive index (dyne s/cm5/m2) | 0.43 | 0.01 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | –0.50 | 0.004 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | –0.21 | 0.23 |

| LV end-diastolic volume index (mL/m2) | –0.24 | 0.20 |

| LV end-systolic volume index (mL/m2) | –0.08 | 0.64 |

| LV stroke volume index (mL/m2) | –0.34 | 0.06 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | –0.19 | 0.30 |

| LV end-diastolic mass index (g/m2) | –0.01 | 0.97 |

| RV end-diastolic volume index (mL/m2) | 0.35 | 0.04 |

| RV end-systolic volume index (mL/m2) | 0.50 | 0.005 |

| RV stroke volume index (mL/m2) | –0.36 | 0.04 |

| RV ejection fraction (%) | –0.47 | 0.006 |

| RV mass index (g/m2) | 0.58 | < 0.001 |

| Eccentricity index | –0.52 | 0.002 |

| Septomarginal trabecular mass index (g/m2) | 0.71 | < 0.001 |

| Ventricular mass index | 0.70 | < 0.001 |

Note—LV = left ventricular, RV = right ventricular.

Delayed Enhancement and Biventricular Function

Significant correlations were found between total delayed enhancement mass and reduced RV function parameters, including RV end-diastolic volume index (r = 0.35, p = 0.04), RV end-systolic volume index (0.50, p = 0.005), RV ejection fraction (r = –0.47, p = 0.006), and RV stroke volume index (r = –0.36, p = 0.04) (Table 2). In addition, significant correlation was present between total delayed enhancement mass and eccentricity index (r = –0.52, p = 0.002).

Delayed Enhancement and Regional Function

Regional functional analysis at the anterior septal insertion revealed reduced longitudinal strain at the basal and apical levels (p < 0.05) with trend to significance at the midventricular level (p = 0.05) (Fig. 1C). Reduced circumferential strain was noted only at the midventricular level (p = 0.023). At the posterior septal insertion, only reduction in circumferential strain was noted at the mid and apical ventricular levels (p < 0.05) (Table 3). In all PH patients, anterior septal insertion delayed enhancement mass correlated significantly with reduced longitudinal strain at the basal ventricular level (r = 0.60, p < 0.01). At the posterior septal insertion, however, delayed enhancement mass did not correlate significantly with regional strain (Table 4). Reduced longitudinal shortening at the basal anterior septal insertion correlated highly with increased mean PAP (r = 0.7, p < 0.001), PVRI (r = 0.55, p < 0.01), reduced RV ejection fraction (r = –0.6, p < 0.001), and increased ventricular mass index (r = 0.6, p < 0.01).

TABLE 3.

Regional Strain at Right Ventricular Attachment Sites in Patients With Pulmonary Hypertension Compared With Controls

| Value |

Patients With Pulmonary Hypertension (n = 32) |

Controls (n = 10) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal strain (%) | |||

| Anterior septal insertion | |||

| Base | –14.0 (–9.7 to 17.1) | –18.9 (–17.7 to 19.9) | 0.01 |

| Midportion | –14.7 (–12.1 to 19.0) | –17.6 (–16.5 to 21.1) | 0.05 |

| Apex | –17.0 (–12.1 to 20.4) | –21.1 (–18.9 to 22.8) | 0.01 |

| Posterior septal insertion | |||

| Base | –20.1 (–13.3 to 23.9) | –19.0 (–16.5 to 23.8) | 0.84 |

| Midportion | –16.2 (–13.5 to 22.7) | –18.0 (–13.9 to 20.4) | 0.98 |

| Apex | –17.1 (–12.9 to 20.0) | –16.8 (–14.5 to 18.8) | 0.99 |

| Circumferential strain (%) | |||

| Anterior septal insertion | |||

| Base | –13.7 (–9.2 to 17.2) | –16.9 (–15.2 to 18.1) | 0.07 |

| Midportion | –14.1 (–10.4 to 18.3) | –18.8 (–17.8 to 21.1) | 0.02 |

| Apex | –17.0 (–12.7 to 20.7) | –18.1 (–14.8 to 22.8) | 0.30 |

| Posterior septal insertion | |||

| Base | –12.4 (–9.7 to 15.3) | –15.9 (–10.7 to 16.9) | 0.21 |

| Midportion | –11.5 (–9.6 to 13.6) | –16.8 (–11.6 to 18.1) | 0.04 |

| Apex | –12.3 (–7.7 to 15.8) | –16.6 (–14.2 to 18.2) | 0.04 |

Note—Mann-Whitney test was used for regional strain comparison between pulmonary hypertension and control groups. Data are presented as median and 25th to 75th percentile range.

TABLE 4.

Correlations Between Delayed Enhancement Mass and Regional Strain in Corresponding Regions in Patients With Pulmonary Hypertension (n = 32)

| Delayed Enhancement Mass (g) |

Longitudinal Strain |

Circumferential Strain |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior septal insertion | ||

| Base | 0.60a | 0.1 |

| Mid | 0.25 | 0.41b |

| Apex | 0.34 | 0.17 |

| Posterior septal insertion | ||

| Base | 0.31 | –0.14 |

| Mid | 0.03 | –0.3 |

| Apex | 0.02 | –0.01 |

p < 0.01.

p < 0.05.

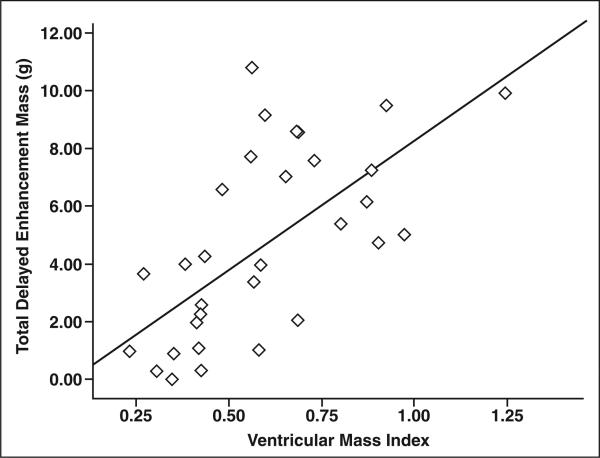

Delayed Enhancement and Markers of Right Ventricular Remodeling

Total delayed enhancement mass correlated significantly with RV mass index (r = 0.58, p < 0.001), septomarginal trabecular mass index (r = 0.71, p < 0.001), and ventricular mass index (r = 0.70, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4 and Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Scatterplot shows significant direct correlation between total delayed enhancement mass and ventricular mass index (r = 0.70, p < 0.001) in all patients with pulmonary hypertension (n = 32).

Predictors of Septal Delayed Enhancement Mass

In multiple linear regression analysis in which mean PAP, RV ejection fraction, eccentricity index, ventricular mass index, and MRI system type were covariates, ventricular mass index was an independent predictor of total delayed enhancement mass (β = 7.9; p = 0.026; 95% CI, 1.03–14.9). When ventricular mass index was replaced with RV and LV mass indexes separately, only RV mass index was an independent predictor of total delayed enhancement mass (β = 0.16; p = 0.017; 95% CI, 0.03–0.28).

Regional multiple linear regression analysis was performed to predict local delayed enhancement mass at the anterior and posterior septal insertions. The parameters in the model were mean PAP, RV mass index, eccentricity index, longitudinal strain, and circumferential strain. Basal longitudinal strain was an independent predictor of delayed enhancement mass at the basal anterior septal insertion (β = 0.1; p = 0.02; 95% CI, 0.019–0.18).

3-T and 1.5-T Sample Subanalysis

Subanalysis performed on the data acquired from the 3-T (n = 26) and 1.5-T (n = 12) examinations separately showed no significantly different correlations between total delayed enhancement mass and global and regional function or catheter-acquired hemodynamics in the two groups.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first in which delayed septal enhancement at the RV insertion sites has been characterized in detail with respect to the effect of regional mechanics in patients with PH. Delayed enhancement was frequently detected at the RV insertion sites in 97% (31/32) of PH patients and 17% (1/6) of patients with suspected but absent PH and was absent in the control group. In accordance with our hypothesis, total delayed enhancement mass correlated significantly with the degree of RV functional and hemodynamic impairment. These findings are in agreement with those of previous MRI studies of delayed enhancement in PH patients [19, 20, 26]. In our study, RV mass index was the main predictor of total delayed enhancement mass. This finding suggests that the amount of delayed enhancement at the RV attachment sites is directly related to the degree of RV remodeling in response to increased afterload. Delayed enhancement at the RV insertion sites has been reported previously, particularly in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [27, 28]. McCann et al. [19] identified areas of fibrosis at the RV septal insertions at autopsy of two PH patients who did not undergo cardiac MRI. On the basis of this observation and our findings, we conclude that delayed enhancement at the RV insertions most likely represents underlying fibrosis.

Interestingly, negative correlation was observed between total delayed enhancement mass at the RV insertion sites and eccentricity index. This finding reflects the role played by the interventricular septum in interventricular dependence. Although always present, ventricular interdependence is most apparent with changes in loading conditions. Under elevated pressure load, increased RV pressure shifts the interventricular septum toward the left, altering LV geometry and affecting LV filling, which was reflected by lower LV enddiastolic volume in the PH group than in controls. Therefore, our results suggest that septal bowing in response to increased RV afterload accentuates the tension at the insertion sites and may be a contributor to development of delayed enhancement [26, 29, 30].

In PH patients, reduction of basal longitudinal strain and increased delayed enhancement mass at the anterior RV insertion correlated significantly with increased RV afterload, that is, mean PAP and PVRI. They were also correlated with markers of global RV dysfunction and remodeling.

As described by Ho and Nihoyannopoulos [31], the architectural arrangement of the RV muscle fibers differs from that of the LV fibers. In the RV, the deep muscle layer is composed primarily of longitudinal fibers as opposed to the circumferential arrangement in the LV. This arrangement contributes to the predominantly longitudinal RV shortening responsible for blood ejection during systole.

Despite higher prevalence of delayed enhancement at the posterior septal insertion, no significant association with reduced regional function was detected. At the basal anterior septal insertion, however, reduced longitudinal strain was an independent predictor of anterior septal insertion delayed enhancement mass. This finding could be attributed to the difference in mechanical forces acting on both insertions, being part of anatomically and functionally distinct regions, namely the RV outflow and inflow tracts [32]. The basal anterior septal insertion is generally under greater tension caused by its proximity to the RV outflow tract, especially at the basal level. In PH, the outflow tract forms a resistive element to prevent high pressure generated in the body of the RV free wall from affecting the pressure-sensitive pulmonary vasculature [33]. The septomarginal trabecular hypertrophy that occurs as part of RV remodeling close to the basal anterior septal insertion was also associated with higher anterior septal insertion delayed enhancement mass [23]. Similarly, the differences between the two septal regions with respect to fiber architecture and fiber compliance [34] also may account for the quantitatively different changes in longitudinal and circumferential shortening observed at both sites.

That the work in this study was performed at two centers is a possible limitation of the study. To eliminate potential differences due to different field strengths and techniques, we performed separate subanalyses for the 1.5-T and 3-T cohorts. We calculated the correlations of delayed enhancement mass for global and regional function indexes and catheter hemodynamics separately without significantly different results. We therefore conclude that the use of two MRI systems of different field strengths did not change the conclusions of this study.

Also in this study we assessed only the circumferential and longitudinal components of myocardial deformation. We did not, however, investigate the radial component. Radial strain data acquired by tagging usually have the greatest variability because they are based on the lowest spatial density of tag lines (two or three lines across the myocardial thickness), and this limitation would be further accentuated toward the RV septal insertions [35].

In PH, total delayed enhancement burden at the RV septal insertions is predicted by RV remodeling in response to increased RV after-load. Local fibrosis mass at the anterior septal insertion is associated with reduced regional longitudinal contractility at the base. Further research needs to be conducted to evaluate the prognostic value of delayed enhancement at the RV insertion sites in patients with PH.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant NIH 1P50HL08946 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

N. F. Osman is a founder and a shareholder in Diagnosoft, Inc. The terms of this arrangement have been approved by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

References

- 1.Elliot C, Kiely DG. Pulmonary hypertension: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Med. 2004;4:211–215. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.4-3-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc., and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1573–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chin KM, Kim NH, Rubin LJ. The right ventricle in pulmonary hypertension. Coron Artery Dis. 2005;16:13–18. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humbert M. The burden of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:1–2. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00055407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher MR, Criner GJ, Fishman AP, et al. Estimating pulmonary artery pressures by echocardiography in patients with emphysema. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:914–921. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00033007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher MR, Forfia PR, Chamera E, et al. Accuracy of Doppler echocardiography in the hemodynamic assessment of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:615–621. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200811-1691OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grothues F, Moon JC, Bellenger NG, Smith GS, Klein HU, Pennell DJ. Interstudy reproducibility of right ventricular volumes, function, and mass with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Am Heart J. 2004;147:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pennell DJ, Sechtem UP, Higgins CB, et al. Clinical indications for cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR): consensus panel report. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2004;6:727–765. doi: 10.1081/jcmr-200038581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tandri H, Daya SK, Nasir K, et al. Normal reference values for the adult right ventricle by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1660–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zerhouni EA, Parish DM, Rogers WJ, Yang A, Shapiro EP. Human heart: tagging with MR imaging—a method for noninvasive assessment of myocardial motion. Radiology. 1988;169:59–63. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.1.3420283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fayad ZA, Ferrari VA, Kraitchman DL, et al. Right ventricular regional function using MR tagging: normals versus chronic pulmonary hypertension. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39:116–123. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan L, Stuber M, Kraitchman DL, Fritzges DL, Gilson WD, Osman NF. Real-time imaging of regional myocardial function using fast-SENC. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:386–395. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Parrish TB, et al. Relationship of MRI delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, and contractile function. Circulation. 1999;100:1992–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.19.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingkanisorn WP, Rhoads KL, Aletras AH, Kellman P, Arai AE. Gadolinium delayed enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance correlates with clinical measures of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2253–2259. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tandri H, Saranathan M, Rodriguez ER, et al. Noninvasive detection of myocardial fibrosis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy using delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, Judd RM, Sechtem U, Kim RJ. Delayed enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance assessment of non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1461–1474. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srichai MB, Schvartzman PR, Sturm B, Kasper JM, Lieber ML, White RD. Extent of myocardial scarring on nonstress delayed-contrast-enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance imaging correlates directly with degrees of resting regional dysfunction in chronic ischemic heart disease. Am Heart J. 2004;148:342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soler R, Rodriguez E, Monserrat L, Mendez C, Martinez C. Magnetic resonance imaging of delayed enhancement in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: relationship with left ventricular perfusion and contractile function. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:412–420. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200605000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCann GP, Gan CT, Beek AM, Niessen HW, Vonk Noordegraaf A, van Rossum AC. Extent of MRI delayed enhancement of myocardial mass is related to right ventricular dysfunction in pulmonary artery hypertension. AJR. 2007;188:349–355. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanz J, Dellegrottaglie S, Kariisa M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of septal delayed contrast enhancement in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:731–735. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osman NF, Sampath S, Atalar E, Prince JL. Imaging longitudinal cardiac strain on short-axis images using strain-encoded MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:324–334. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan T, Petrovic O, Dillon JC, Feigenbaum H, Conley MJ, Armstrong WF. An echocardiographic index for separation of right ventricular volume and pressure overload. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:918–927. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James TN. Anatomy of the crista supraventricularis: its importance for understanding right ventricular function, right ventricular infarction and related conditions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;6:1083–1095. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80313-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shehata ML, Skrok J, Lossnitzer D, et al. Pulmonary hypertension: role of septomarginal trabeculation and moderator band complex assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11(suppl 1):P91. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levin JR, Serlin RC, Seaman MA. A controlled, powerful multiple-comparison strategy for several situations. Psychol Bull. 1994;115:153–159. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blyth KG, Groenning BA, Martin TN, et al. Contrast enhanced-cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1993–1999. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choudhury L, Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, et al. Myocardial scarring in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:2156–2164. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moon JC, McKenna WJ, McCrohon JA, Elliott PM, Smith GC, Pennell DJ. Toward clinical risk assessment in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with gadolinium cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1561–1567. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haddad F, Hunt SA, Rosenthal DN, Murphy DJ. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease. Part I. Anatomy, physiology, aging, and functional assessment of the right ventricle. Circulation. 2008;117:1436–1448. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.653576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcus JT, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Roeleveld RJ, et al. Impaired left ventricular filling due to right ventricular pressure overload in primary pulmonary hypertension: noninvasive monitoring using MRI. Chest. 2001;119:1761–1765. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.6.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho SY, Nihoyannopoulos P. Anatomy, echocardiography, and normal right ventricular dimensions. Heart. 2006;92(suppl 1):i2–i13. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.077875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kukulski T, Hubbert L, Arnold M, Wranne B, Hatle L, Sutherland GR. Normal regional right ventricular function and its change with age: a Doppler myocardial imaging study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2000;13:194–204. doi: 10.1067/mje.2000.103106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armour JA, Pace JB, Randall WC. Interrelationship of architecture and function of the right ventricle. Am J Physiol. 1970;218:174–179. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.218.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armour JA, Randall WC. Structural basis for cardiac function. Am J Physiol. 1970;218:1517–1523. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.218.6.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore CC, Lugo-Olivieri CH, McVeigh ER, Zerhouni EA. Three-dimensional systolic strain patterns in the normal human left ventricle: characterization with tagged MR imaging. Radiology. 2000;214:453–466. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.2.r00fe17453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]