Abstract

The liver has enormous regenerative capacity. Following acute liver injury, hepatocyte division regenerates the parenchyma but, if this capacity is overwhelmed during massive or chronic liver injury, the intrinsic hepatic progenitor cells (HPCs) termed oval cells are activated. These HPCs are bipotential and can regenerate both biliary epithelia and hepatocytes. Multiple signalling pathways contribute to the complex mechanism controlling the behaviour of the HPCs. These signals are delivered primarily by the surrounding microenvironment. During liver disease, stem cells extrinsic to the liver are activated and bone-marrow-derived cells play a role in the generation of fibrosis during liver injury and its resolution. Here, we review our current understanding of the role of stem cells during liver disease and their mechanisms of activation.

Keywords: Liver regeneration, Liver cirrhosis, Oval cells, Stem cells, Bone marrow

Introduction

Chronic liver disease is common and has severe clinical consequences that arise from the loss of functional hepatocytes and excessive scar formation. Currently, therapies are insufficient to treat these disorders effectively. Great interest has therefore been shown in characterising the regenerative capacity of the liver in order to manipulate this process therapeutically. The liver has an exceptional regenerative capacity that is now appreciated to occur both by replication of differentiated hepatocytes and through activation of the intrahepatic stem cell compartment. Hepatic stem cells are described as facultative as they only participate in hepatocyte replacement when regeneration by mature hepatocytes is overwhelmed or impaired. At present, the consensus is that a bipotential hepatic progenitor cell (HPC) population expands in human liver diseases and a variety of animal models (Roskams et al. 2003b; Santoni-Rugiu et al. 2005). Stem-cell-directed therapy thus offers the hope of improving outcomes during chronic liver disease. Unsurprisingly, interest has more recently turned to delineating the control mechanisms of the HPCs. Together with indigenous hepatic stem cells, stem cells within the bone marrow (BM) are also activated during liver disease and play central roles in inflammation and tissue remodelling. Here, we aim to review critically the evidence for the presence of stem cells within the liver and the mechanisms of their activation, together with the role of extrahepatic stem cells during liver disease.

Somatic stem cells are expected to display certain characteristics: (1) self-renewal, (2) multipotentiality, (3) transplantability and (4) functional long-term tissue reconstitution. Stem cells themselves are required to maintain their undifferentiated state while dividing. Progenitor cells in contrast show a limited ability to self-renew. They comprise distinct subpopulations with variable lineage potential. Moreover, unlike stem cells, progenitor cells divide rapidly but cannot be serially transplanted and hence have been named transit amplifying cells (Shafritz et al. 2006). Activation in the context of stem cells refers to an expansion of cell number by proliferation combined with differentiation towards different lineages. HPCs are thought to be bipotential progenitors capable of forming either hepatocytes or cholangiocytes. In rodents, HPCs have historically been called oval cells (OCs) because of their histological appearance.

HPC characterisation

HPCs are heterogeneous, consisting of a spectrum of cells ranging from an immature phenotype to mature cholangiocytes and intermediate hepatocytes. Although markers for the most immature progenitor cells have not been identified, there are currently a variety of established markers for constituents of the HPC compartment (Table 1). Many HPC markers are expressed by mature cholangiocytes and hepatocytes and by embryonic bipotential hepatoblasts. No universal HPC marker, specific to this compartment, has been identified to date. This is likely to be a feature of the progressive differentiation of HPCs during which they vary their marker expression. Currently, there is a genuine requirement for a thorough understanding of the step-wise marker expression in HPCs akin to that described for the development of haematopoietic stem cells.

Table 1.

Adult HPC markers with representative references

| Oval cell marker and abbreviations | References |

|---|---|

| Adult biliary marker | |

| Cytokeratin 19 (CK19) | Bisgaard et al. 1993 |

| CK7 | Paku et al. 2005 |

| CK14 | Bisgaard et al. 1993 |

| γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase (γGT) | Cameron et al. 1978 |

| Glutathione-S-transferase P (GST-P) | Tee et al. 1992 |

| Muscle pyruvate kinase (MPK) | Akhurst et al. 2005 |

| OV-6 (recognises CK14 and CK19) | Bisgaard et al. 1993 |

| OV1 | Sanchez et al. 2004 |

| A6 | Engelhardt et al. 1993 |

| OC.2 and OC.3 | Hixson and Allison 1985 |

| Connexin 43 | Zhang and Thorgeirsson 1994 |

| CX3Cl1 | Yovchev et al. 2007 |

| CD24 | Yovchev et al. 2007 |

| MUC1 | Yovchev et al. 2007 |

| Deleted in malignant brain tumour 1 (DMBT1) |

Bisgaard et al. 2002 |

| Adult hepatocyte markers | |

| Albumin | Tian et al. 1997 |

| CK8 | Libbrecht et al. 2000b |

| CK18 | Libbrecht et al. 2000b |

| α1-Antitrypsin | Gauldie et al. 1980 |

| Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (HNF4) | Nagy et al. 1994 |

| HBD.1 | Faris et al. 1991 |

| c-Met | Hu et al. 1993 |

| Fetal hepatocyte markers | |

| α-Fetoprotein (αFP) | Evarts et al. 1987 |

| Delta-like protein (dlk) | Yovchev et al. 2007 |

| Aldolase A and C | Lamas et al. 1987 |

| c-Met | Hu et al. 1993 |

| Cadherin 22 | Yovchev et al. 2007 |

| CD24 | Yovchev et al. 2007 |

| CD44 | Kon et al. 2006 |

| Adult haematopoietic markers | |

| c-kit | Fujio et al. 1994 |

| CXCR4 | Zheng et al. 2006 |

| CD34 | Omori et al. 1997 |

| Sca-1 | Petersen et al. 2003 |

The early HPC markers described to date include c-kit, sca-1, NCAM, spermatogenic immunoglobulin superfamily (SgIGSF) and multidrug resistance transporters, which denote a side-population (SP) phenotype. The SP phenotype was originally described in the haematopoietic system and relates to the ability to efflux the dye Hoechst 33342. It appears to identify cells with immature characteristics, particularly with regard to hepatic embryogenesis (Tsuchiya et al. 2005) and carcinogenesis (Chiba et al. 2006). Another feature of immature cells is the absence of cytokeratin 7 (CK7) expression; CK7 is expressed as HPCs acquire a mature phenotype (Paku et al. 2005), which is in keeping with the demonstration of CK7 in the later stages of hepatic organogenesis (Shiojiri et al. 1991). Alpha-fetoprotein (αFP) is an OC marker that is also expressed during human hepatic embryogenesis and carcinogenesis. It appears to be present in intermediate ducts (Alpini et al. 1992) with prolonged expression for over 3 weeks following partial hepatectomy (PH) with retrorsine treatment (Gordon et al. 2000) and is also expressed by more differentiated hepatocyte-like cells in rats (Evarts et al. 1989). αFP expression is however notable by its absence during the OC response in mice (Jelnes et al. 2007).

Mechanisms of hepatic regeneration

The anatomical position of the liver and its physiological role place it in a toxin-rich environment. As such, it is required to tolerate frequent exposure to toxins. In addition, persistent insults such as viral disease, immunological or genetic disorders may continually challenge the liver. Evolutionarily, the liver has adapted to cope well with such insults and the regenerative capacity of the adult mammalian liver is immense. An injured liver is able to call upon a two-tier regenerative strategy comprised initially of mature hepatocyte followed, if need be, by HPCs (Alison 1998; Fig. 1).

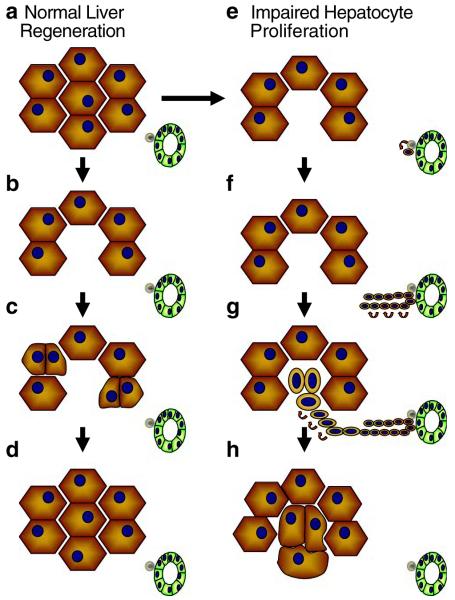

Fig. 1.

Injury of the healthy liver (a) may be repaired in two ways. Either regeneration from the fully differentiated hepatocyte compartment (brown) is maintained (b) or it is impaired (e). In the case of maintained hepatocyte proliferation, replacement of damaged hepatocytes is quickly and efficiently achieved by division of pre-existing hepatocytes (c) resulting in the restoration of hepatocyte number (d) without expansion of HPCs. If hepatocyte injury occurs in the context of impaired hepatocyte proliferation (e), then stem cells (grey) located in the terminal biliary tree (green) are activated leading to the generation of a transit amplifying compartment (black, f), which spreads into the liver parenchyma (g). These cells are able to replace damaged hepatocytes, often forming regenerative nodules (h)

Hepatocyte-mediated regeneration

Normally, the turnover of hepatocytes in the liver is slow with hepatocytes having a life span of approximately 1 year. Acute liver injury, for example PH, results in rapid and effective regeneration with hepatocytes undergoing mitosis leading to subsequent restoration of liver function within two cycles of division (Fausto et al. 2006). This process in pigs has recently been shown to include telomerase activation (Wege et al. 2007). Naturally, the question has been raised as to whether hepatocytes themselves function as stem cells. Landmark transplantation studies in fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase knockout (FAH −/−) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) transgenic mice have demonstrated that hepatocytes possess a virtually unlimited proliferative potential. They are capable of a least 69 cell divisions and can restore normal architecture and impaired function in the injured liver (Rhim et al. 1994; Overturf et al. 1997). Furthermore, Grompe and coworkers have shown, in the FAH−/− mouse, that adult hepatocytes expand clonally (Overturf et al. 1999) and may be serially transplanted (Overturf et al. 1997). These models however rely on a strong selection advantage against native hepatocytes. In addition, wild-type hepatocytes have been suggested to show multipotentiality when transplanted into the livers of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV) knockout mice followed by PH and retrosine treatment. DPPIV is an exopeptidase expressed on the bile canalicular surface of hepatocytes in addition to diffuse cytoplasmic expression by bile duct epithelia. Using this model, Michalopoulos et al. (2005) have shown that transplanted DPPIV+ cells reconstitute bile ducts following bile duct ligation (BDL); the authors, in their previous work, note however that this hepatocyte infusion is not entirely pure (Michalopoulos et al. 2001). Notwithstanding, this study raises the possibility that hepatocytes may, in specific circumstances, display multipotentiality. Therefore, under certain conditions, hepatocytes may show many of the characteristics of stem cells. The models demonstrating self-renewal nervertheless share continual selection pressure for transplanted hepatocytes versus indigenous epithelia in the context of persistent liver injury. Whether human hepatocytes are capable of acting as true stem cells remains doubtful.

HPC-mediated regeneration

Rodent HPC models

The first description of candidate hepatic progenitor-like cells was made in 1937 (Kinosita 1937) with the subsequent naming of OCs in rodents following a report by Farber in 1956 (Farber 1956). These cells are characteristically ’small ovoid cells with scant lightly basophilic cytoplasm and pale blue-staining nuclei” and are not seen in the uninjured mammalian liver. In rodents, a variety of liver injury models have been used to induce an OC response (for a comprehensive list, see Santoni-Rugiu et al. 2005). PH alone in the otherwise uninjured rodent results in a regenerative response by the mature epithelial compartment but not by OCs. Analysis of carcinogenesis models such as 2-N-acetylaminofluorene (AAF) in combination with PH has demonstrated that the mitogenic stimulus of the PH may stimulate OCs when hepatocyte-mediated regeneration is inhibited (Solt and Farber 1976). AAF is converted to an active cytotoxic/mitoinhibitory N-hydroxy derivative by the cytochromes of mature hepatocytes (Alison 1998). OCs, by virtue of the low level expression of hepatocytic cytochromes, are resistant to this toxic effect and, as such, expand following AAF/PH. The carcinogenic alkaloid retrorsine specifically inhibits hepatocyte proliferation by a similar mechanism (Laconi et al. 1999) and, like AAF, has been used in combination with the mitogenic stimulus of PH or toxins, such as carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and allyl alcohol, to induce an OC response. Diets, such as the carcinogenic choline-deficient ethionine-supplemented (CDE) diet or the 3,5-diethoxycarbonlyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine-supplemented (DDC) diet, also stimulate an OC response and have more recently become increasingly popular models particularly in mice.

Investigation of OCs has made remarkable progress since the seminal work by Thorgeirsson and coworkers (Evarts et al. 1987, 1989) who demonstrated that rats treated with AAF followed by PH (AAF/PH) exhibited OC proliferation beginning in the periportal region. At later time points in these models, label-retaining basophilic hepatocytes were seen in the mid-parenchyma suggesting a precursor/product relationship. Further work has shown that OCs stream into regenerative nodules (Vig et al. 2006). The tracing of tritiated thymidine transfer from OCs to parenchymal cells in combination with differentiation markers has revealed the bipotentiality of HPCs, which are able to form either hepatocytes or cholangiocytes (Evarts et al. 1989; Holic et al. 2000). Indeed, HPCs themselves may express mature hepatocyte or biliary duct markers such as CK18 or CK19 (see Table 1. Observations by electron microscopy to study cell ultrastructure have shown a differentiation gradient of cells from more primitive progenitors to differentiated hepatocytes and cholangiocytes (De Vos and Desmet 1992; Mandache et al. 2002). This bipotentiality is furthermore demonstrated by the generation of stable OC lines that are capable of differentiating into cholangiocyte or hepatocyte-like cells in vitro (Lazaro et al. 1998). In addition, these cells are also capable of engrafting following transplantation and expanding in the recipient liver (Faris and Hixson 1989; Yasui et al. 1997). Therefore, HPCs, in rodents at least, appear to possess the characteristics of progenitor cells, in addition to possessing a variety of markers implying stem cell function (e.g. c-kit, CD34 and flt3). Meticulous studies in rodents have demonstrated that OCs are predominantly derived from the terminal ducts, known as the canals of Hering, in the biliary tree (Saxena et al. 1999; Theise et al. 1999; Paku et al. 2001). Following activation, these OCs expand, forming ductular structures extending between the biliary tree and hepatocytes (Paku et al. 2001). This anatomical position at the interface between the parenchyma and the portal tract mesenchyme is also the site of bipotential hepatoblasts during hepatic organogenesis. Although differences have been noted (Dudas et al. 2006), many phenotypic and functional parallels exist between embryonic bipotential hepatoblasts and adult HPCs (Shafritz et al. 2006).

HPCs in human liver disease

In humans, HPC activation is believed to take the form of a ductular reaction. This is morphologically and immunohistochemically analogous to the rodent OC response. The clinical relevance of the HPC reactions is implied by its frequency in a wide variety of human liver diseases including fulminant hepatic failure, chronic viral hepatitis, alcoholic disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, immune cholangiopathies and hereditary liver disorders (Roskams et al. 1991, 2003a, 2003b; Falkowski et al. 2003; Roskams 2003; Fig. 2). During acute liver injury, HPC regeneration may be seen occurring synchronously with a degree of hepatocyte replication. The presence of HPC activation during chronic liver disease however is probably a feature of eventual exhaustion of hepatocyte proliferation over many years or decades (Wiemann et al. 2002; Marshall et al. 2005). Characteristically, the magnitude of HPC activation corresponds to the severity of liver fibrosis and inflammation (Lowes et al. 1999; Libbrecht et al. 2000a; Roskams et al. 2003a). In addition, the more aggressive a hepatocellular injury, the higher the proportion of observed HPCs that resemble intermediate hepatocytes. This implies that an escalating hepatocyte deficiency promotes a greater degree of differentiation down the progenitor cell/hepatocyte axis (Roskams et al. 2003b).

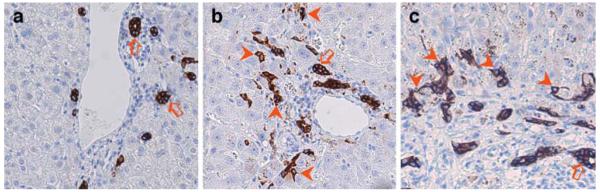

Fig. 2.

Human ductular reaction in a patient with recurrent hepatitis C infection following cadaveric liver transplantation. a Pre-perfusion biopsy of donor liver prior to both implantation and hepatitis C infection; note the CK7+ cells in the bile ducts (arrows). b, c Biopsies from the same liver 1 and 6 months, respectively, after transplantation and hepatitis C infection. These sections show CK7+ HPCs (arrowheads) extending from the periportal regions into the parenchyma.

Despite the apparently stereotyped HPC response seen across a wide range of human diseases, there is heterogeneity both between species and injury models (Jelnes et al. 2007). For example, the expression of αFP, which is characteristically seen in rodent OC reactions, is rare in the human ductular reaction. Differing characteristics are seen between models; for instance, the expression of DMBT1 (deleted in malignant brain tumour 1) is seen following hepatocelluar injury but not during human cholestatic liver disease or following BDL in rodents (Bisgaard et al. 2002). Consistent with an atypical HPC response in the BDL model, dexamethasone does not effect ductule formation following BDL in rats but inhibits OC activation following AAF/PH (Nagy et al. 1998).

In contrast to observations in rodents, the characteristics of stem cells have not been demonstrated in human ductular reactions to date. Sequential biopsies taken from patients have shown HPC proliferation and suggest their differentiation by observing a progressive increase in intermediate hepatocytes in association with their progressive extension into the liver lobule over time (Roskams et al. 1991; Demetris et al. 1996; Falkowski et al. 2003). Proliferating cells have been isolated from human liver capable of hepatocyte-like differentiation (Herrera et al. 2006). Further characterisation is required however to confirm these initial observations.

Mechanisms of HPC activation

The mechanisms controlling the HPC response are under intense investigation. In general, although many of the signals that control liver regeneration in the normal liver (i.e. via hepatocyte replication) are involved in HPC-mediated regeneration, acute liver injury does not significantly activate the HPC compartment. The most common context in which the HPC reaction is seen is when the cell cycle in hepatocyte regeneration is blocked either by toxins or replicative senescence in rodent models or human disease. Nevertheless, the two modes of liver regeneration are not entirely mutually exclusive, as HPC and hepatocyte replication can be observed simultaneously in some injury models (Rosenberg et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2003). This may simply be a function of the location, duration and/or magnitude of these specific signals. However, other factors such as cellular environment are likely to be highly relevant in generating the HPC response. Certainly, the wide range of candidate signals, with many showing only modest effects, suggests a significant signal redundancy in HPC control.

Observational studies show a correlation between liver disease severity and the magnitude of the HPC response (Lowes et al. 1999; Libbrecht et al. 2000a). A central role of inflammatory cytokines has also been suggested in rodents (Knight et al. 2005a). These observations are consistent with the dramatic inhibition of OC responses noted upon treatment with anti-inflammatory agents (Davies et al. 2006; Nagy et al. 1998). In terms of specific signals, many have been studied directly during HPC activation in vitro and in vivo (for an overview, see Table 2). Most of these signals are also seen during PH; however, they often exhibit differences in either the intensity or duration of the signal.

Table 2.

Key functional studies in animal models for investigating control mechanisms of OC activation. Manipulation of target signal is shown by arrows: ↑ indicates upregulation, whereas ↓ indicates inhibition of signalling. For OC models, M and R denote murine and rat studies, respectively (explanations of other abbreviations can be found in the Abbreviations list)

| Signal | OC model | Effect on OCs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF | |||

| ↓ In vivo | 50% CDE diet (M) | ↓ Expansion | Knight et al. 2000 |

| ↑ In vitro | LE6 cells IV (R) | ↑ Proliferation | Kirillova et al. 1999 |

| ↑ In vitro | LE6 cells IV (R) | ↑ Mitogenesis | Brooling et al. 2005 |

| TWEAK | |||

| ↑ In vivo | Uninjured (M) | ↑ Expansion | Jakubowski et al. 2005 |

| ↑ In vivo | Uninjured adults (M) | ↑ Expansion | |

| ↓ In vivo | DDC diet (M) | ↓ Expansion | |

| ↑ In vitro | NRC line (R) | ↑ Mitogenesis | |

| LTα | |||

| ↓ In vivo | CDE diet (M) | ↓ Expansion | Knight and Yeoh 2005 |

| LTβ | |||

| ↓ In vivo | CDE diet (M) | ↓ Expansion | Akhurst et al. 2005 |

| STAT3 | |||

| ↑ In vivo | None (M) | ↑ Expansion | Yeoh et al. 2007 |

| ↑ In vivo | CDE diet (M) | ↑ Expansion, migration | Yeoh et al. 2007 |

| IL6 | |||

| ↓ In vivo | 50% CDE diet (M) | ↓ Proliferation | Knight et al. 2000 |

| ↑ In vitro | PIL2/PIL4 lines (M) | ↑ Proliferation | Matthews et al. 2004 |

| ↑ In vivo | CDE diet (M) | ↑ Expansion, proliferation | Yeoh et al. 2007 |

| ↓ In vivo | AAF/PH (R) | ↓ Expansion | Nagy et al. 1998 |

| OSM | |||

| ↑ In vitro | PIL2/PIL4 lines (M) | ↓ Growth | Matthews et al. 2005 |

| ↑ In vitro | Primary OCs (M) | Equal growth | Matthews et al. 2005 |

| IFNγ | |||

| ↑ In vivo | Uninjured (M) | OC-like expansion | Toyonaga et al. 1994 |

| ↓ In vivo | CDE diet (M) | ↓ Expansion | Akhurst et al. 2005 |

| ↑ In vivo | 2/3 PH (M) | ↑ Expansion | Brooling et al. 2005 |

| IFNα | |||

| ↑ In vitro | PIL2/PIL4 lines (M) | ↓ Proliferation | Lim et al. 2006 |

| ↑ In vivo | CDE diet (M) | ↓ Expansion, proliferation | |

| HGF | |||

| ↑ In vivo | AAF (R) | ↑ Proliferation | Nagy et al. 1996 |

| ↑ In vivo | AAF/PH (R) | ↑ Early expansion | Hasuike et al. 2005 |

| ↑ In vivo | AAF/PH (R) | ↑ Expansion | Oe et al. 2005 |

| EGF | |||

| ↑ In vivo | AAF (R) | ↑ Proliferation | Nagy et al. 1996 |

| ↑ In vitro | MOC lines (M) | ↑ Proliferation | Isfort et al. 1997 |

| TGFβ | |||

| ↑ In vivo | DDC diet (M) | ↓ Expansion | Preisegger et al. 1999 |

| ↑ In vitro | LE2/LE6 cells (R) | ↓ Proliferation | Nguyen et al. 2007 |

| SCF | |||

| ↓ In vivo | AAF/PH (R) | ↓ Expansion | Matsusaka et al. 1999 |

| Sympathetic nervous system | |||

| ↓ In vivo | 50% CDE diet (M) | ↓ Expansion | Oben et al. 2003 |

| Parasympathetic nervous system | |||

| ↓ In vivo | Galactosamine (R) | ↓ Expansion | Cassiman et al. 2002 |

Tumour necrosis factor superfamily

Members of the pro-inflammatory tumour necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily include TNFα and TWEAK (TNF-like weak induction of apoptosis), both of which appear to play pivotal roles in HPC activation. While many members of the TNF superfamily, including TNFα and lymphotoxin (LT), play important roles in both HPC and hepatocyte-mediated regeneration (Knight and Yeoh 2005; Fausto et al. 2006), TWEAK stands out by demonstrating differential effects on the mature hepatocyte and progenitor cell compartments (Jakubowski et al. 2005). TWEAK is upregulated during hepatic injury, both in rodents and in a variety of human diseases, and mediates pro-proliferative effects directly on OCs via the Fn14 receptor (Jakubowski et al. 2005). TWEAK is sufficient, although not necessary, to induce a modest OC response, whereas its inhibition results in an attenuated murine OC response. This therefore positions TWEAK as arguably the most important intercellular signal inducing the hepatic HPC response. It is produced predominantly by monocytes, particularly following interferon-γ (IFNγ) stimulation (Nakayama et al. 2000), and is initially expressed as a membrane -ound molecule that can also be released in a soluble form. TWEAK activates nuclear factor kappaB, which is pro-proliferative to OCs (Kirillova et al. 1999); it may also play a role in the proliferation of other mesenchymal progenitors (Girgenrath et al. 2006), including promoting angiogenesis (Jakubowski et al. 2002), and may contribute to hepatic embryogenesis and carcinogenesis (Kawakita et al. 2005).

TNFα production is increased during chronic human liver disease (Tilg et al. 1992). It is known to be predominantly produced by macrophages but also by other cells types, including lymphocytes and fibroblasts (Locksley et al. 2001), and is upregulated during the rodent OC response (Knight et al. 2000; Akhurst et al. 2005). Cellular activity is mediated via the TNF R1 and TNF R2 receptors. Administration of TNFα to OC lines in vitro results in proliferation (Kirillova et al. 1999). Furthermore, TNF R1 knockout mice show a markedly impaired OC response (Knight et al. 2000). No study to date, including that with TNFα/LTα knockout mice (Knight and Yeoh 2005), has shown an absolute requirement for TNFα but all suggest that TNFα is required for an optimal OC response.

LT-α, LT-β and LIGHT are also members of the TNF superfamily and are involved in a variety of processes including influencing cell survival and proliferation. LT-α, like TNF, binds TNF R1, which as described previously plays an important role in the control of the OC response. Its role in HPC activation is suggested but not confirmed by the demonstration that LT-α/TNFα double-knockout mice develop an attenuated OC response following the CDE diet (Knight and Yeoh 2005). LT-α may also act in combination with LT-β via the formation of a heterotrimer (LTα1β2), which is the ligand for a separate receptor; LT-β receptor (LT-βR). LT-β expression is upregulated during rodent OC activation and during chronic human liver disease. Both LT-β knockout and LT-βR knockout mice show a partially impaired OC response (Akhurst et al. 2005). Another ligand for LT-βR called LIGHT is potentially therefore also involved. LIGHT is predominantly expressed by lymphocytes (Hansson 2007) and, although its effects on HPCs have not been directly investigated, it is known to signal to hepatocytes via LT-βR (Lo et al. 2007).

GP130 activators

A variety of cytokines, including interleukin 6 (IL6), oncostatin M (OSM) and leukaemia inhibitor factor (LIF), act through the gp130 signalling pathway. Following homodimerisation, gp130 activates the JAK (Janus kinase)/STAT (signal transductor and activator of transcription) and ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) pathways. STAT3 and its targets are upregulated during the rodent OC response and during human chronic liver disease (Sanchez et al. 2004; Subrata et al. 2005) and also play an established role in hepatocyte-mediated regeneration following PH (Fausto et al. 2006).

Aside from TWEAK, gp130 is the only signal demonstrated to date capable of initiating an OC response alone. This has been revealed in uninjured gp130Y757F mice with constitutively active gp130 (Subrata et al. 2005). Another of the downstream targets of gp130, viz. the ERK-1/2 pathway, has been shown by the same investigators to be a negative regulator of OC expansion. Therefore, gp130 is potentially a key element in the activation and expansion of hepatic HPCs. IL-6 is the best characterised of the gp130 activators; it is produced by a variety of cell types including macrophages, fibroblasts and endothelia. Recent studies have demonstrated that IL-6 is pro-proliferative to the OC response and that IL-6 knockout mice demonstrate a reduced OC response (Fischer et al. 1997; Knight et al. 2000; Yeoh et al. 2007). Treatment of OC lines with IL-6 results in proliferation and migration (Matthews et al. 2004; Yeoh et al. 2007). IL-6 signals via the type I cytokine receptor CD126 (IL-6Rα) together with the signal transducing gp130 homodimer principally activating STAT3 (Yeoh et al. 2007). IL-6 expression increases in both acute and chronic human disease and rodent liver injury models (Streetz et al. 2003; Akhurst et al. 2005; Fausto et al. 2006). Thus, IL-6 is a key signal in hepatocyte proliferation but is not in itself capable of inducing an OC response (Yeoh et al. 2007). The source of IL-6 during liver injury is likely to be activated leucocytes, including Kupffer cells and lymphocytes (Streetz et al. 2003); however, IL6 production has also been described from HPCs themselves, raising the possibility of autocrine stimulation (Matthews et al. 2004).

LIF and OSM both participate in a variety of processes including the regulation of growth and differentiation. The action of LIF is mediated via the LIF receptor (LIFR), which is composed of LIFRβ and gp130. Its downstream effect in OCs occurs predominantly via STAT1 (Kirillova et al. 1999). Both LIF and LIFR are upregulated during the OC reaction in the rat (Omori et al. 1996) and in human cirrhotic livers, with LIFRβ localising to proliferating CK7+ intermediate hepatobiliary cells (Znoyko et al. 2005). Although the effects of LIF on HPC proliferation are not clear, it does have stimulatory effects on other progenitor cells, including murine haematopoietic progenitors (Metcalf and Gearing 1989). LIF has also been described to have effects of hepatocyte differentiation. Murine embryonic bodies when cultured with LIF are maintained in a undifferentiated state but differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells upon its removal (Chinzei et al. 2002). OSM also activates gp130, either via its own OSM receptor (OSMRβ) subunit or via LIFR (Heinrich et al. 2003). OSM influences extrahepatic progenitor cell activity and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, in addition to inducing an acute phase response. It is produced by hepatic macrophages in humans and is upregulated during both cirrhotic human liver disease (Znoyko et al. 2005) and the rodent OC reaction (Matthews et al. 2005). Both murine OCs and human intermediate hepatobiliary cells express OSMRβ, which induces activation of STAT3 (Znoyko et al. 2005; Matthews et al. 2005). OSM has been described to promote the proliferation and differentiation of fetal hepatoblasts (Kinoshita et al. 1999) and OCs lines (Yin et al. 1999, 2002), respectively. Conflicting data however have come from an immortalised p-53-deficient OC line (Matthews et al. 2005). Further investigation is required to clarify the role of OSM in HPC activation.

Interferon γ

There is strong evidence for a role of the inflammatory cytokine IFNγ in HPC activation. It is characteristically expressed by T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. Although it also activates the JAK-STAT pathway, in contrast to many gp130-mediated signals, INFγ signals predominantly through the STAT1 pathway (Croker et al. 2003). Its role in HPC activation was initially examined in a transgenic mouse with constitutive hepatic IFNγ expression by using a serum amyloid P component gene promoter. These mice demonstrated cords of small cells morphologically similar to OCs in the context of progressive liver inflammation (Toyonaga et al. 1994). Since then, OCs have been found to possess functional IFNγ receptors and IFNγ expression has been shown during the OC reaction (Bisgaard et al. 1999). Varying effects, including proliferation, are seen when IFNγ is administered to OC lines (Brooling et al. 2005). More consistent effects have been seen during in vivo manipulation, with reduced OC expansion being seen in IFNγ knockout mice (Akhurst et al. 2005) and IFNγ treatment stimulating an OC response following PH in mice (Brooling et al. 2005). These observations are consistent with the impaired OC response seen in BALB/c mice that lack Th1 signalling, of which IFNγ is a key component (Knight et al. 2007). Caution however should be exercised as reduced OC expansion has also been noted in vitro (Brooling et al. 2005) and IFNγ may have indirect effects upon the OC response via the inhibition of hepatocyte proliferation (Fausto et al. 2006). IFNγ has been proposed to be a factor in determining hepatocyte versus HPC-mediated regeneration, although convincing data to support this hypothesis are lacking.

Type I interferons

The effects of the type 1 interferons (IFNα and IFNβ) on HPCs appear to differ significantly from that of IFNγ. IFNα signals predominantly through STAT3 in murine liver (Lim et al. 2006). Analysis of paired human liver biopsies reveals that both successful and unsuccessful IFNα treatment of hepatitis C virus is associated with a reduced number of HPCs (Lim et al. 2006; Tsamandas et al. 2006). This effect is not reliant on hepatitis C, as IFNα reduces OC proliferation both in vitro and in vivo in the absence of hepatitis C infection (Lim et al. 2006). Furthermore, IFNα appears to promote differentiation particularly into hepatocyte-like cells. The effects of IFNβ on HPCs are unknown, although, like IFNα, it impairs regeneration following PH alone (Wong et al. 1995; Theocharis etal. 1997). Its role in HPC activation therefore warrants further investigation.

Primary growth factors

The role of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in stimulating hepatocyte proliferation in the primed liver has been well described (Fausto et al. 2006). Like hepatocytes, OCs also express the HGF receptor c-Met (Hu et al. 1993; Muller et al. 2002). The expression of HGF is increased following PH/AAF in the rat (Evarts et al. 1993; Hu et al. 1993), as is uPA (Nagy et al. 1996), which can release HGF stored in its bound form on the ECM. HGF levels are also increased in the serum of patients with chronic liver disease and of those experiencing acute injury compared with healthy controls (Shiota et al. 1995). HGF is both mitogenic to, and promotes the differentiation of, OCs in vivo (Nagy et al. 1996; Hasuike et al. 2005). This is in concordance with similar effects on embryonic hepatic stem cells (Suzuki et al. 2003). There is therefore strong evidence for a role of HGF in influencing HPC behaviour; however, elevations of HGF in the context of PH alone are insufficient to stimulate HPC expansion.

Transforming growth factor-α (TGFα) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) are structurally related membrane-bound growth factors that bind the EGF receptor (EGFR) of adjacent cells, in turn initiating a variety of effects including the upregulation of the EGFR and cell proliferation (Leahy 2004). Membrane-bound pro-TGFα may also be cleaved to release a soluble signal capable of autocrine and paracrine signalling. In rodents, TGFα and EGF are produced predominantly by stellate cells, which are known to line OC ductules (Paku et al. 2001), whereas the EGFR is expressed by OCs (Evarts et al. 1992). TGFα is upregulated following AAF/PH injury in rodents (Evarts et al. 1993) and both EGF and TGFα localise to ductular reactions in human chronic liver disease (Hsia et al. 1994; Komuves et al. 2000). EGF is mitogenic to OCs in vitro suggesting a role of both growth factors in HPC activation.

The fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) are a family of growth factors that bind their FGF receptors (FGFR) with the aid of heparin sulphate proteoglycans (Pellegrini 2001). FGFs are involved in hepatic embryogenesis (Jung et al. 1999) and are upregulated in both the rat AAF/PH model (Marsden et al. 1992) and during human chronic liver disease (Jin-no et al. 1997). Whereas FGFR2 is upregulated in a variety of liver injuries and is expressed by numerous cell types, FGFR1 in adult rats is upregulated specifically during HPC-inducing injury and is expressed by OCs (Hu et al. 1995). In keeping with their role in organogenesis, FGFs induce a hepatocyte-like phenotype in BM-derived “multipotent adult progenitor cells” in vitro (Schwartz et al. 2002).

Transforming growth factor-β

TGFβ is well known to limit hepatocyte-mediated regeneration by inhibiting hepatocyte proliferation and inducing apoptosis (Fausto et al. 2006) and is actively expressed by myofibroblasts following OC-inducing injury (Park and Suh 1999). Active expression of TGFβ in a transgenic mouse fed on the DDC diet results in a reduced OC response (Preisegger et al. 1999). Concordantly, TGFβ is inhibitory to OC lines in vitro (Nguyen et al. 2007), although TGFβ is less inhibitory of mitosis in OCs than in hepatocytes.

Stem cell factor

Stem cell factor (SCF) acts via the c-kit receptor and has well-described functions including the promotion of cell survival and the proliferation and differentiation of haematopoietic progenitor cells. Expression of SCF is increased in the AAF/PH model but not following PH alone. Its receptor, c-kit, is an established HPC marker. Functional investigation of c-kit by using a dysfunctional c-kit receptor suggests that SCF is pro-proliferative to OCs in the rat (Matsusaka et al. 1999). Interestingly, as discussed previously, gp130 and c-kit activation is regarded as the minimal requirement for the expansion of haematopoietic progenitors (Fischer et al. 1997) and, therefore, SCF is also potentially a key player in HPC activation.

Connective tissue growth factor

Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) is a matrix-associated heparin-binding protein that mediates cell proliferation and differentiation and ECM remodelling in a variety of tissues. It is regulated by TGFβ and is known to be upregulated both in animal models of HPC activation (Pi et al. 2005) and human chronic liver disease (Paradis et al. 2001; Gressner et al. 2006). Inhibition of CTGF during rat OC proliferation results in reduced cellular proliferation and expression of αFP (Pi et al. 2005).

Stromal-cell-derived factor 1

The chemokine stromal-cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) uniquely binds to the CXCR4 receptor and plays a variety of roles including cell trafficking, proliferation and organogenesis. CXCR4 is expressed by a variety of progenitor cells and SDF-1 is upregulated during human chronic liver disease (Terada et al. 2003). There is however some disagreement over the source of SDF-1 during the hepatic OC response with reports suggesting either hepatocytic or periportal production (Hatch et al. 2002; Mavier et al. 2004; Zheng et al. 2006). None-the-less, SDF-1 is clearly upregulated following OC-inducing rodent injury. SDF-1 has been shown to be both pro-proliferative (Pi et al. 2005) and chemotactic (Hatch et al. 2002) to OCs.

Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor γ

Intracellular peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) may also mediated a degree of OC control. Their principally described role is in the control of lipid metabolism in response to binding to fatty acid and eicosanoid ligands. Their pro-proliferative role during HPC activation is suggested by in vivo and in vitro studies showing that administration of a PPARγ inhibitor attenuates OC growth (Knight et al. 2005b). This effect may in part be mediated by prostaglandins, as PPARγ might be activated by prostaglandin J2 (Forman et al. 1995). Prostaglandin production is inhibited by COX2 inhibitors, which themselves are known to inhibit the OC reaction (Davies et al. 2006).

Spermatogenic immunoglobulin superfamily

SgIGSF is an intercellular adhesion molecule that can bind either homophilically or heterophilically; it is expressed on HPCs both in humans and in rodents and appears to identify an immature phenotype (Ito et al. 2007). Signal inhibition by using a blocking antibody results in the inhibition of ductular formation in an in vitro model. The report of Ito et al. (2007) not only highlights this molecule as a potential further addition to the already complex array of signals mediating OC control, but also emphasises the ongoing nature of the description of new pathways mediating such control.

Neural input

Fewer intermediate hepatobiliary cells are seen in transplanted graft livers that develop recurrent disease than in matched liver biopsies taken from untransplanted patients. This observation has led to the hypothesis that denervation as result of transplantation directly affects the HPC response. Expression of both adrenoreceptors and muscarinic receptors corresponding to the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system respectively has been described on OCs. The inhibition of the sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous systems either chemically or surgically in rodents results in the expansion or contraction of the HPC response, respectively (Cassiman et al. 2002; Oben et al. 2003). The mechanism of action of neurotransmitters on HPCs together with the demonstration that neurons make direct functional contract with these cells are topics that remain to be investigated.

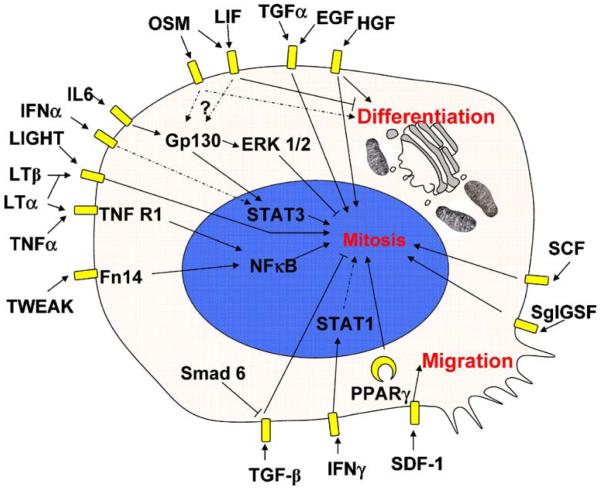

As discussed above, a variety of signals have been implicated in the activation of HPCs (see Fig. 3). Many of these signals are known to be delivered by cells that are seen surrounding the HPC reaction. This raises the hypothesis of there being a specialised niche regulating HPC behaviour both physiologically and during disease. The ECM plays a key role in other stem cell niches and is seen surrounding HPCs (Paku et al. 2001); it is therefore also implicated in forming the hepatic stem cell niche.

Fig. 3.

A variety of influence HPC behaviour by modulating mitosis, differentiation and migration (abbreviations are explained in Table 1 and in the Abbreviations list)

Role of extrahepatic stem cell activation during liver disease

Over the last decade, the importance of BM stem cell (BMSC) activation during liver disease has become apparent. CD34-positive and CD133-positive cells appear to be upregulated following liver transplantation or PH in the diseased liver (De Silvestro et al. 2004; Gehling et al. 2005; Lemoli et al. 2006). Similarly, cells with haematopoietic stem cell markers are mobilised following liver injury in rodents (Fujii et al. 2002) and, in this context, are recruited to the liver (Kollet et al. 2003). There has been considerable interest in the possibility that the BM contributes to liver parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells. Furthermore, current data point towards a role in modulating hepatic fibrosis, in addition to the control of HPC behaviour outlined above.

Hepatic parenchymal regeneration by BM

Work carried out during the last 10 years has made apparent that OCs express a variety of markers, such as c-kit and sca-1, that had previously been thought of as haematopoietic (see Table 1; Petersen et al. 2003). Furthermore, BM-derived stem cells have been shown to differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells in vitro (Yamazaki et al. 2003; Yamada et al. 2006). When hepatocytes were identified that expressed extrahepatic markers in both rodent (Petersen et al. 1999) and human liver (Alison et al. 2000; Theise et al. 2000), the exciting possibility that BM-derived cells were transdifferentiating into hepatocytes was raised. Examination by using Y chromosome tracking in human liver specimens from either female patients with a previous BM transplant from male donors, or male patients who had received a liver transplant from female donors demonstrated that a number (varying from 0%–40% depending upon the study) of hepatocytes possessed a Y chromosome (Thorgeirsson and Grisham 2006). The implication was, therefore, that BM-derived cells were crossing lineage boundaries via transdifferentiation to form hepatocytes. This was investigated in detail in rodents including the FAH−/− mouse, a model for human hereditary type I tyrosinaemia in which hepatic injury may be inhibited at will by the administration of a protective chemical ([2-(2-nitro-4-fluoromethylbenzoyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione], NTBC). NTBC prevents hepatotoxicity by blocking the formation of fumarylacetoacetate. When FAH−/− mice are given BM and the protection of NTBC is gradually withdrawn, hepatocytes expressing markers of the transplanted BM are seen to reconstitute the mouse liver (Lagasse et al. 2000). Subsequent work however has convincingly shown that, instead of plasticity, monocyte-hepatocyte fusion is the mechanism by which BM cells rescue a genetically deficient phenotype in the FAH−/− mouse (Alvarez-Dolado et al. 2003; Vassilopoulos et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2003b; Camargo et al. 2004; Willenbring et al. 2004). These monocyte-hepatocyte fusion events are rare but rescue in the FAH−/− model is nevertheless attributable to the proliferation of these fusion cells (Wang et al. 2002). This occurs as selective pressure is applied against native hepatocytes lacking the correcting wild-type genes. In the absence of such selective pressure, however, significant hepatocytes replacement is rarely seen and, at most, occurs at a level far below that of native hepatocytes turnover (Yannaki et al. 2005; Thorgeirsson and Grisham 2006). Despite initial reports that HPCs may be in part BM-derived (Petersen et al. 1999), more recent studies suggest that this does not occur to any significant degree (Wang et al. 2003a; Menthena et al. 2004; Vig et al. 2006). OCs from BM transplanted mice neither express the BM-tracking marker to any significant degree nor show clustering suggestive of the expansion of BM-derived OCs. Importantly, transplantation of an OC fraction into the FAH−/− mouse in one study has shown that transplantable cells are not BM-derived (Wang et al. 2003a). Some ongoing uncertainty exists in this area, however, as a recent report suggests that the OCs may indeed be BM-derived (Oh et al. 2007). The study investigated DPPIV+ cells after DPPIV-deficient rats were transplanted with wild-type BM. AAF/PH was used in these animals to induce an OC response and resulted in DPPIV+ cells within the liver (Oh et al. 2007). DPPIV is however not a specific hepatocyte marker and is expressed by sinusoidal endothelia (Koivisto et al. 2001) and T lymphocytes (Vivier et al. 1991).

BM contribution to hepatic non-parenchymal cells

Kupffer cells/macrophages

Although approximately 80% of the liver mass is comprised of parenchymal epithelial cells, a number of other cell types play a variety of key physiological roles within the liver. Leucocyte-derived populations remain as resident monocytes (Kupffer cells), whereas other populations transiently traffic through the liver. At least a proportion of hepatic Kupffer cells are BM-derived (Abe et al. 2003; Higashiyama et al. 2007). Kupffer cells have been implicated in a variety of processes during hepatic disease including inflammation, regeneration, fibrosis and ECM remodelling. Administration of gadolinium chloride, which inhibits Kupffer cells, prevents the expansion of OCs positive for muscle pyruvate kinase, in response to BDL in rats (Olynyk et al. 1998). This is consistent with the intimate spatial relationship between Kupffer cells and OCs (Yin et al. 1999). Similarly, gadolinium chloride treatment is able to reduce fibrosis in thioacetamide-treated rats (Ide et al. 2005) consistent with the putative role of Kupffer cells and macrophages in the process of hepatic fibrosis and ECM remodelling. This role has been corroborated by using an inducible macrophage-specific depletion model in mice during or following CCl4 injury; this work has demonstrated that both the generation and resolution of fibrosis are macrophage-dependent (Duffield et al. 2005). The mechanism of tissue remodelling may include the expression of the matrix-remodelling metalloproteinase MMP-9 by BM-derived F4/80+ macrophages during the resolution of fibrosis following CCl4 injury (Higashiyama et al. 2007).

Hepatic stellate cells

Sustained injury occurring in human chronic liver disease is usually accompanied by progressive fibrosis and potentially by cirrhosis resulting from excessive deposition of collagen and other components of the ECM. Central to this process is the population of matrix-secreting myofibroblasts, which, at least in part, are formed following the activation of hepatic stellate cells (Henderson and Iredale 2007). Myofibroblasts not only deposit ECM, but also alter its degradation by the expression of tissue inhibitors of MMP. Investigations in rodent models by using labelled BM transplantation (Baba et al. 2004; Russo et al. 2006) or human studies following sex mis-matched liver or BM transplants (Forbes et al. 2004) have shown a significant BM contribution to populations of both hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts and this process does not appear to occur through cell fusion. Other studies of the BDL model have found only a small proportion (5%–10%) of collagen-producing cells are BM-derived (Kisseleva et al. 2006).

Endothelial progenitors

Capillaries extend alongside the smallest branches of the biliary tree during chronic rejection following liver transplantation, consistent with new vessel formation paralleling progenitor ductules (Gouw et al. 2006). A least a proportion of liver sinusoidal cells that expand following liver injury are BM-derived (Gao et al. 2001; Fujii et al. 2002; Taniguchi et al. 2006). These cells produce a variety of growth factors including HGF, EGF and TGFα, all of which have been implicated in modulating the HPC response (Taniguchi et al. 2006).

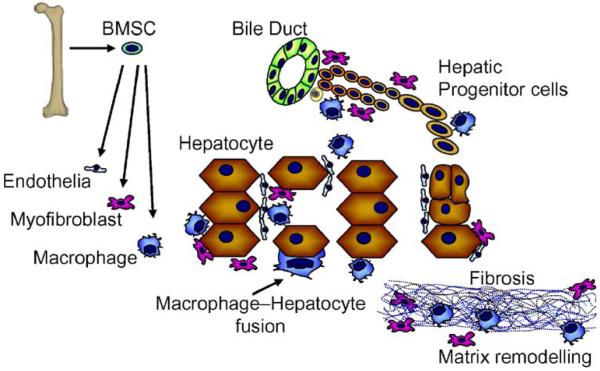

The BM is therefore able to produce a variety of cells in response to liver injury (Fig. 4). These various populations described to date orchestrate an assortment of functions during liver injury. BM-derived cells act as precursors to a variety of non-parenchymal cells. In doing so, the BM significantly contributes to the deposition, remodelling and resolution of hepatic fibrosis. The role of the BM in parenchymal cell regeneration appears to be minimal. Under carefully controlled experimental conditions, the BM can make dramatic contributions to hepatocyte regeneration, albeit via fusion with pre-existing hepatocytes rather than by transdifferentiation.

Fig. 4.

Overview of HPC activation during liver injury. During hepatic injury, regeneration of hepatocytes may occur from hepatocytes or by expansion and differentiation of HPCs. Bone marrow stem cells (BMSC) are also activated forming macrophages, myofibroblasts and endothelial cells. Macrophages may fuse with hepatocytes. Macrophages and myofibroblasts also play key roles in both the production and resolution of fibrosis in the liver

Functions of BM-derived stem cells during human liver disease

To date only a handful of clinical trials have investigated the role of stem cell mobilisation therapy or stem cell infusion in adults. G-CSF (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor) has been used to induce haematopoietic stem cell mobilisation to the peripheral blood of patients with cirrhosis (Gaia et al. 2006). In association with the mobilisation of CD34+ and CD133+ cells, only two out of eight patients showed moderate improvement in liver function. Trials of cell therapy have included a cohort of patients with liver cancer in whom portal vein embolisation was used to induce compensatory hypertrophy in the contralateral liver lobe prior to surgical resection. Thirteen patients underwent portal vein embolisation, six of whom received an infusion of autologous CD133+ BMSC. This non-randomised trial demonstrated a marginal but significant increase in liver volume and reduced time to surgery in patients receiving autologous BMSC infusions (Furst et al. 2007). Another uncontrolled study in five patients with cirrhosis investigated the effects of autologous CD34+ BMSCs. Three of these patients showed transient improvements in biochemical markers such as bilirubin and albumin over the following 2 months (Gordon et al. 2006). A case report has described clinical improvement following infusion of autologous G-CSF mobilised CD34+ BM cells in a single patient with hepatic failure (Gasbarrini et al. 2006). Autologous monocyte therapy has also been attempted by using a larger number of unsorted cells extracted from the BM of cirrhotic patients. In the nine patients receiving BM, an improvement in the Child-Pugh score was noted with an increase in intrahepatic cell proliferation in the patients biopsied after treatment (Terai et al. 2006). Despite these encouraging reports, caution must be exercised. Only one of these trials used controls (non-randomised) and all were performed in a small number of patients. Engraftment or colonisation of infused cell was not investigated in any of the studies. Therefore, a considerable amount of further investigation is required in this area.

HPCs and cancer

A final consideration of the activation of stem cells during liver disease should include their potential role in carcino-genesis (see the review by Morrison and Alison in this issue). Chronic activation of HPCs occurs at a time when liver cancer develops. Inhibition of the rodent HPC response during the long-term CDE diet is associated with a reduction in the incidence of cancerous lesions (Knight et al. 2000). The occurrence of mixed forms of liver cancer with features of both hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma is consistent with a bipotential HPC origin (Alison 2005; Roskams 2006), as are the similarities in gene expression between HCC subtypes and OCs (Lee et al. 2006). Clearly, these observations have implications for the use of HPC-directed therapies.

Concluding remarks

To date, a great deal has been learnt about stem cell activation, during liver disease, from experimental studies in well established rodent models. From a clinical perspective, an understanding of regenerative processes is essential in guiding patient management and for offering new therapies to harness or augment the impressive capacity of the liver for regeneration. Stem cells are at the hub of such regeneration in chronic liver disease but also appear to be involved in fibrogenesis and carcinogenesis within the liver.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Training Fellowship to T.G.B.; S.L. is supported by an EASL Sheila Sherlock Fellowship Post-Doctoral Fellowship.

Abbreviations

- αFP

Alpha-fetoprotein

- AAF

2-N-acetylaminofluorene

- BDL

Bile duct ligation

- BM

Bone marrow

- BMSC

Bone marrow stem cell

- CCl4

Carbon tetrachloride

- CDE

Choline-deficient ethionine-supplemented

- CK

Cytokeratin

- CTGF

Connective tissue growth factor

- DDC

3,5-Diethoxycarbonlyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine-supplemented

- DPPIV

Dipeptidyl peptidase IV

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- FAH −/−

Fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase knockout

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR

FGF receptor

- G-CSF

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HPC

Hepatic progenitor cell

- IFN

Interferon

- IL

Interleukin

- JAK

Janus kinase

- LIF

Leukaemia inhibitor factor

- LIFR

LIF receptor

- LT

Lymphotoxin

- MMP

Metalloproteinase

- OC

Oval cell

- OSM

Oncostatin M

- OSMR

OSM receptor

- PH

Partial hepatectomy

- PPAR

Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor

- SCF

Stem cell factor

- SDF-1

Stromal-cell-derived factor 1

- SgIGSF

Spermatogenic immunoglobulin superfamily

- STAT

Signal transductor and activator of transcription

- TGF

Transforming growth factor

- TNF

Tumour necrosis factor

- TWEAK

TNF-like weak induction of apoptosis

- uPA

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator

References

- Abe S, Lauby G, Boyer C, Rennard SI, Sharp JG. Transplanted BM and BM side population cells contribute progeny to the lung and liver in irradiated mice. Cytotherapy. 2003;5:523–533. doi: 10.1080/14653240310003576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhurst B, Matthews V, Husk K, Smyth MJ, Abraham LJ, Yeoh GC. Differential lymphotoxin-beta and interferon gamma signaling during mouse liver regeneration induced by chronic and acute injury. Hepatology. 2005;41:327–335. doi: 10.1002/hep.20520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alison M. Liver stem cells: a two compartment system. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:710–715. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alison MR. Liver stem cells: implications for hepatocarcinogenesis. Stem Cell Rev. 2005;1:253–260. doi: 10.1385/SCR:1:3:253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alison MR, Poulsom R, Jeffery R, Dhillon AP, Quaglia A, Jacob J, Novelli M, Prentice G, Williamson J, Wright NA. Hepatocytes from non-hepatic adult stem cells. Nature. 2000;406:257. doi: 10.1038/35018642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpini G, Aragona E, Dabeva M, Salvi R, Shafritz DA, Tavoloni N. Distribution of albumin and alpha-fetoprotein mRNAs in normal, hyperplastic, and preneoplastic rat liver. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:623–632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Fike JR, Lee HO, Pfeffer K, Lois C, Morrison SJ, Alvarez-Buylla A. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;425:968–973. doi: 10.1038/nature02069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba S, Fujii H, Hirose T, Yasuchika K, Azuma H, Hoppo T, Naito M, Machimoto T, Ikai I. Commitment of bone marrow cells to hepatic stellate cells in mouse. J Hepatol. 2004;40:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgaard HC, Parmelee DC, Dunsford HA, Sechi S, Thorgeirsson SS. Keratin 14 protein in cultured nonparenchymal rat hepatic epithelial cells: characterization of keratin 14 and keratin 19 as antigens for the commonly used mouse monoclonal antibody OV-6. Mol Carcinog. 1993;7:60–66. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940070110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgaard HC, Muller S, Nagy P, Rasmussen LJ, Thorgeirsson SS. Modulation of the gene network connected to interferon-gamma in liver regeneration from oval cells. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1075–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgaard HC, Holmskov U, Santoni-Rugiu E, Nagy P, Nielsen O, Ott P, Hage E, Dalhoff K, Rasmussen LJ, Tygstrup N. Heterogeneity of ductular reactions in adult rat and human liver revealed by novel expression of deleted in malignant brain tumor 1. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1187–1198. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64395-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooling JT, Campbell JS, Mitchell C, Yeoh GC, Fausto N. Differential regulation of rodent hepatocyte and oval cell proliferation by interferon gamma. Hepatology. 2005;41:906–915. doi: 10.1002/hep.20645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo FD, Finegold M, Goodell MA. Hematopoietic myelomonocytic cells are the major source of hepatocyte fusion partners. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1266–1270. doi: 10.1172/JCI21301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron R, Kellen J, Kolin A, Malkin A, Farber E. Gamma-glutamyltransferase in putative premalignant liver cell populations during hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1978;38:823–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassiman D, Libbrecht L, Sinelli N, Desmet V, Denef C, Roskams T. The vagal nerve stimulates activation of the hepatic progenitor cell compartment via muscarinic acetylcholine receptor type 3. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:521–530. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64208-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba T, Kita K, Zheng YW, Yokosuka O, Saisho H, Iwama A, Nakauchi H, Taniguchi H. Side population purified from hepatocellular carcinoma cells harbors cancer stem cell-like properties. Hepatology. 2006;44:240–251. doi: 10.1002/hep.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinzei R, Tanaka Y, Shimizu-Saito K, Hara Y, Kakinuma S, Watanabe M, Teramoto K, Arii S, Takase K, Sato C, Terada N, Teraoka H. Embryoid-body cells derived from a mouse embryonic stem cell line show differentiation into functional hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2002;36:22–29. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croker BA, Krebs DL, Zhang JG, Wormald S, Willson TA, Stanley EG, Robb L, Greenhalgh CJ, Forster I, Clausen BE, Nicola NA, Metcalf D, Hilton DJ, Roberts AW, Alexander WS. SOCS3 negatively regulates IL-6 signaling in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:540–545. doi: 10.1038/ni931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies RA, Knight B, Tian YW, Yeoh GC, Olynyk JK. Hepatic oval cell response to the choline-deficient, ethionine supplemented model of murine liver injury is attenuated by the administration of a cyclo-oxygenase 2 inhibitor. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1607–1616. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silvestro G, Vicarioto M, Donadel C, Menegazzo M, Marson P, Corsini A. Mobilization of peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cells following liver resection surgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:805–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos R, Desmet V. Ultrastructural characteristics of novel epithelial cell types identified in human pathologic liver specimens with chronic ductular reaction. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:1441–1450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetris AJ, Seaberg EC, Wennerberg A, Ionellie J, Michalopoulos G. Ductular reaction after submassive necrosis in humans. Special emphasis on analysis of ductular hepatocytes. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:439–448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudas J, Elmaouhoub A, Mansuroglu T, Batusic D, Tron K, Saile B, Papoutsi M, Pieler T, Wilting J, Ramadori G. Prosperorelated homeobox 1 (Prox1) is a stable hepatocyte marker during liver development, injury and regeneration, and is absent from “oval cells”. Histochem Cell Biol. 2006;126:549–562. doi: 10.1007/s00418-006-0191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffield JS, Forbes SJ, Constandinou CM, Clay S, Partolina M, Vuthoori S, Wu S, Lang R, Iredale JP. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:56–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt NV, Factor VM, Medvinsky AL, Baranov VN, Lazareva MN, Poltoranina VS. Common antigen of oval and biliary epithelial cells (A6) is a differentiation marker of epithelial and erythroid cell lineages in early development of the mouse. Differentiation. 1993;55:19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1993.tb00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evarts RP, Nagy P, Marsden E, Thorgeirsson SS. A precursor-product relationship exists between oval cells and hepatocytes in rat liver. Carcinogenesis. 1987;8:1737–1740. doi: 10.1093/carcin/8.11.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evarts RP, Nagy P, Nakatsukasa H, Marsden E, Thorgeirsson SS. In vivo differentiation of rat liver oval cells into hepatocytes. Cancer Res. 1989;49:1541–1547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evarts RP, Nakatsukasa H, Marsden ER, Hu Z, Thorgeirsson SS. Expression of transforming growth factor-alpha in regenerating liver and during hepatic differentiation. Mol Carcinog. 1992;5:25–31. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940050107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evarts RP, Hu Z, Fujio K, Marsden ER, Thorgeirsson SS. Activation of hepatic stem cell compartment in the rat: role of transforming growth factor alpha, hepatocyte growth factor, and acidic fibroblast growth factor in early proliferation. Cell Growth Differ. 1993;4:555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkowski O, An HJ, Ianus IA, Chiriboga L, Yee H, West AB, Theise ND. Regeneration of hepatocyte “buds” in cirrhosis from intra-biliary stem cells. J Hepatol. 2003;39:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber E. Similarities in the sequence of early histological changes induced in the liver of the rat by ethionine, 2-acetylamino-fluorene, and 3′-methyl-4-dimethylaminoazobenzene. Cancer Res. 1956;16:142–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faris RA, Hixson DC. Selective proliferation of chemically altered rat liver epithelial cells following hepatic transplantation. Transplantation. 1989;48:87–92. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198907000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faris RA, Monfils BA, Dunsford HA, Hixson DC. Antigenic relationship between oval cells and a subpopulation of hepatic foci, nodules, and carcinomas induced by the “resistant hepatocyte” model system. Cancer Res. 1991;51:1308–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausto N, Campbell JS, Riehle KJ. Liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2006;43:S45–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.20969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M, Goldschmitt J, Peschel C, Brakenhoff JP, Kallen KJ, Wollmer A, Grotzinger J, Rose-John S. A bioactive designer cytokine for human hematopoietic progenitor cell expansion. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:142–145. doi: 10.1038/nbt0297-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes SJ, Russo FP, Rey V, Burra P, Rugge M, Wright NA, Alison MR. A significant proportion of myofibroblasts are of bone marrow origin in human liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:955–963. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun RP, Spiegelman BM, Evans RM. 15-Deoxy-delta 12, 14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPAR gamma. Cell. 1995;83:803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Hirose T, Oe S, Yasuchika K, Azuma H, Fujikawa T, Nagao M, Yamaoka Y. Contribution of bone marrow cells to liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. J Hepatol. 2002;36:653–659. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujio K, Evarts RP, Hu Z, Marsden ER, Thorgeirsson SS. Expression of stem cell factor and its receptor, c-kit, during liver regeneration from putative stem cells in adult rat. Lab Invest. 1994;70:511–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst G, Schulte am Esch J, Poll LW, Hosch SB, Fritz LB, Klein M, Godehardt E, Krieg A, Wecker B, Stoldt V, Stockschlader M, Eisenberger CF, Modder U, Knoefel WT. Portal vein embolization and autologous CD133+ bone marrow stem cells for liver regeneration: initial experience. Radiology. 2007;243:171–179. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431060625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaia S, Smedile A, Omede P, Olivero A, Sanavio F, Balzola F, Ottobrelli A, Abate ML, Marzano A, Rizzetto M, Tarella C. Feasibility and safety of G-CSF administration to induce bone marrow-derived cells mobilization in patients with end stage liver disease. J Hepatol. 2006;45:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, McAlister VC, Williams GM. Repopulation of liver endothelium by bone-marrow-derived cells. Lancet. 2001;357:932–933. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasbarrini A, Rapaccini GL, Rutella S, Zocco MA, Zocco P, Leone G, Pola P, Gasbarrini G, Di Campli C. Rescue therapy by portal infusion of autologous stem cells in a case of drug-induced hepatitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;39:878–882. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauldie J, Lamontagne L, Horsewood P, Jenkins E. Immunohistochemical localization of alpha 1-antitrypsin in normal mouse liver and pancreas. Am J Pathol. 1980;101:723–735. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehling UM, Willems M, Dandri M, Petersen J, Berna M, Thill M, Wulf T, Muller L, Pollok JM, Schlagner K, Faltz C, Hossfeld DK, Rogiers X. Partial hepatectomy induces mobilization of a unique population of haematopoietic progenitor cells in human healthy liver donors. J Hepatol. 2005;43:845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgenrath M, Weng S, Kostek CA, Browning B, Wang M, Brown SA, Winkles JA, Michaelson JS, Allaire N, Schneider P, Scott ML, Hsu YM, Yagita H, Flavell RA, Miller JB, Burkly LC, Zheng TS. TWEAK, via its receptor Fn14, is a novel regulator of mesenchymal progenitor cells and skeletal muscle regeneration. EMBO J. 2006;25:5826–5839. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon GJ, Coleman WB, Grisham JW. Temporal analysis of hepatocyte differentiation by small hepatocyte-like progenitor cells during liver regeneration in retrorsine-exposed rats. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:771–786. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64591-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MY, Levicar N, Pai M, Bachellier P, Dimarakis I, Al-Allaf F, M’Hamdi H, Thalji T, Welsh JP, Marley SB, Davies J, Dazzi F, Marelli-Berg F, Tait P, Playford R, Jiao L, Jensen S, Nicholls JP, Ayav A, Nohandani M, Farzaneh F, Gaken J, Dodge R, Alison M, Apperley JF, Lechler R, Habib NA. Characterization and clinical application of human CD34+ stem/progenitor cell populations mobilized into the blood by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1822–1830. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouw AS, Heuvel MC, Boot M, Slooff MJ, Poppema S, Jong KP. Dynamics of the vascular profile of the finer branches of the biliary tree in normal and diseased human livers. J Hepatol. 2006;45:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.03.015. van den. de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gressner AM, Yagmur E, Lahme B, Gressner O, Stanzel S. Connective tissue growth factor in serum as a new candidate test for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1815–1817. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.070466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson GK. Medicine. LIGHT hits the liver. Science. 2007;316:206–207. doi: 10.1126/science.1142238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasuike S, Ido A, Uto H, Moriuchi A, Tahara Y, Numata M, Nagata K, Hori T, Hayashi K, Tsubouchi H. Hepatocyte growth factor accelerates the proliferation of hepatic oval cells and possibly promotes the differentiation in a 2-acetylaminofluorene/partial hepatectomy model in rats. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1753–1761. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch HM, Zheng D, Jorgensen ML, Petersen BE. SDF-1alpha/CXCR4: a mechanism for hepatic oval cell activation and bone marrow stem cell recruitment to the injured liver of rats. Cloning Stem Cells. 2002;4:339–351. doi: 10.1089/153623002321025014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Haan S, Hermanns HM, Muller-Newen G, Schaper F. Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem J. 2003;374:1–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson NC, Iredale JP. Liver fibrosis: cellular mechanisms of progression and resolution. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;112:265–280. doi: 10.1042/CS20060242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera MB, Bruno S, Buttiglieri S, Tetta C, Gatti S, Deregibus MC, Bussolati B, Camussi G. Isolation and characterization of a stem cell population from adult human liver. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2840–2850. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashiyama R, Inagaki Y, Hong YY, Kushida M, Nakao S, Niioka M, Watanabe T, Okano H, Matsuzaki Y, Shiota G, Okazaki I. Bone marrow-derived cells express matrix metalloproteinases and contribute to regression of liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2007;45:213–222. doi: 10.1002/hep.21477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hixson DC, Allison JP. Monoclonal antibodies recognizing oval cells induced in the liver of rats by N-2-fluorenylacetamide or ethionine in a choline-deficient diet. Cancer Res. 1985;45:3750–3760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holic N, Suzuki T, Corlu A, Couchie D, Chobert MN, Guguen-Guillouzo C, Laperche Y. Differential expression of the rat gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase gene promoters along with differentiation of hepatoblasts into biliary or hepatocytic lineage. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64564-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia CC, Thorgeirsson SS, Tabor E. Expression of hepatitis B surface and core antigens and transforming growth factor-alpha in “oval cells” of the liver in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Med Virol. 1994;43:216–221. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890430304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Evarts RP, Fujio K, Marsden ER, Thorgeirsson SS. Expression of hepatocyte growth factor and c-met genes during hepatic differentiation and liver development in the rat. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1823–1830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Evarts RP, Fujio K, Marsden ER, Thorgeirsson SS. Expression of fibroblast growth factor receptors flg and bek during hepatic ontogenesis and regeneration in the rat. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:1019–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide M, Kuwamura M, Kotani T, Sawamoto O, Yamate J. Effects of gadolinium chloride (GdCl3) on the appearance of macrophage populations and fibrogenesis in thioacetamide-induced rat hepatic lesions. J Comp Pathol. 2005;133:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isfort RJ, Cody DB, Stuard SB, Randall CJ, Miller C, Ridder GM, Doersen CJ, Richards WG, Yoder BK, Wilkinson JE, Woychik RPJ. The combination of epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta induces novel phenotypic changes in mouse liver stem cell lines. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:3117–3129. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.24.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito A, Nishikawa Y, Ohnuma K, Ohnuma I, Koma Y, Sato A, Enomoto K, Tsujimura T, Yokozaki H. SgIGSF is a novel biliary-epithelial cell adhesion molecule mediating duct/ductule development. Hepatology. 2007;45:684–694. doi: 10.1002/hep.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski A, Browning B, Lukashev M, Sizing I, Thompson JS, Benjamin CD, Hsu YM, Ambrose C, Zheng TS, Burkly LC. Dual role for TWEAK in angiogenic regulation. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:267–274. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski A, Ambrose C, Parr M, Lincecum JM, Wang MZ, Zheng S, Browning B, Michaelson JS, Baetscher M, Wang B, Bissell DM, Burkly LC. TWEAK induces liver progenitor cell proliferation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2330–2340. doi: 10.1172/JCI23486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelnes P, Santoni-Rugiu E, Rasmussen M, Friis SL, Nielsen JH, Tygstrup N, Bisgaard HC. Remarkable heterogeneity displayed by oval cells in rat and mouse models of stem cell-mediated liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2007;45:1462–1470. doi: 10.1002/hep.21569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen CH, Jauho EI, Santoni-Rugiu E, Holmskov U, Teisner B, Tygstrup N, Bisgaard HC. Transit-amplifying ductular (oval) cells and their hepatocytic progeny are characterized by a novel and distinctive expression of delta-like protein/preadipocyte factor 1/fetal antigen 1. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1347–1359. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63221-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin-no K, Tanimizu M, Hyodo I, Kurimoto F, Yamashita T. Plasma level of basic fibroblast growth factor increases with progression of chronic liver disease. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:119–121. doi: 10.1007/BF01213308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J, Zheng M, Goldfarb M, Zaret KS. Initiation of mammalian liver development from endoderm by fibroblast growth factors. Science. 1999;284:1998–2003. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5422.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakita T, Shiraki K, Yamanaka Y, Yamaguchi Y, Saitou Y, Enokimura N, Yamamoto N, Okano H, Sugimoto K, Murata K, Nakano T. Functional expression of TWEAK in human colonic adenocarcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Sekiguchi T, Xu MJ, Ito Y, Kamiya A, Tsuji K, Nakahata T, Miyajima A. Hepatic differentiation induced by oncostatin M attenuates fetal liver hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7265–7270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinosita R. Studies on the cancerogenic chemical substances. Trans Soc Pathol Jpn. 1937;27:329–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillova I, Chaisson M, Fausto N. Tumor necrosis factor induces DNA replication in hepatic cells through nuclear factor kappaB activation. Cell Growth Differ. 1999;10:819–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisseleva T, Uchinami H, Feirt N, Quintana-Bustamante O, Segovia JC, Schwabe RF, Brenner DA. Bone marrow-derived fibrocytes participate in pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2006;45:429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B, Yeoh GC. TNF/LTalpha double knockout mice display abnormal inflammatory and regenerative responses to acute and chronic liver injury. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;319:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-1003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B, Yeoh GC, Husk KL, Ly T, Abraham LJ, Yu C, Rhim JA, Fausto N. Impaired preneoplastic changes and liver tumor formation in tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1 knockout mice. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1809–1818. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B, Matthews VB, Akhurst B, Croager EJ, Klinken E, Abraham LJ, Olynyk JK, Yeoh G. Liver inflammation and cytokine production, but not acute phase protein synthesis, accompany the adult liver progenitor (oval) cell response to chronic liver injury. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005a;83:364–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B, Yeap BB, Yeoh GC, Olynyk JK. Inhibition of adult liver progenitor (oval) cell growth and viability by an agonist of the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) family member gamma, but not alpha or delta. Carcinogenesis. 2005b;26:1782–1792. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B, Akhurst B, Matthews VB, Ruddell RG, Ramm GA, Abraham LJ, Olynyk JK, Yeoh GC. Attenuated liver progenitor (oval) cell and fibrogenic responses to the choline deficient, ethionine supplemented diet in the BALB/c inbred strain of mice. J Hepatol. 2007;46:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto UM, Hubbard AL, Mellman I. A novel cellular phenotype for familial hypercholesterolemia due to a defect in polarized targeting of LDL receptor. Cell. 2001;105:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]