Abstract

The clamp-loader–helicase interaction is an important feature of the replisome. Although significant biochemical and structural work has been carried out on the clamp-loader–clamp–DNA polymerase α interactions in Escherichia coli, the clamp-loader–helicase interaction is poorly understood by comparison. The τ subunit of the clamp-loader mediates the interaction with DnaB. We have recently characterised this interaction in the Bacillus system and established a τ5–DnaB6 stoichiometry. Here, we have obtained atomic force microscopy images of the τ–DnaB complex that reveal the first structural insight into its architecture. We show that despite the reported absence of the shorter γ version in Bacillus, τ has a domain organisation similar to its E. coli counterpart and possesses an equivalent C-terminal domain that interacts with DnaB. The interaction interface of DnaB is also localised in its C-terminal domain. The combined data contribute towards our understanding of the bacterial replisome.

Keywords: DNA replication, clamp-loader, DnaB helicase, atomic force microscopy

Introduction

The dnaX gene in Escherichia coli codes for the τ and γ polypeptides with the latter being the result of a translational frameshift that generates a premature stop codon.1,2 The resulting polypeptides differ in the C-terminal (Cτ) domain of τ (lacking in γ) that corresponds to approximately one-third of the τ sequence. Both τ and γ form the central structural core of the clamp-loader complex that binds and delivers the processivity factor, β, onto primed DNA.3–5 The translational frameshift event in the E. coli dnaX gene is the result of a sequence signal of six adenine residues in the sequence A-AAA-AAG followed by a stop codon and a region of potential secondary structure.6 Similar features are documented in the sequence of the Thermus thermophilus dnaX gene,7 although in this organism a different transcriptional slippage mechanism has been suggested, albeit without ruling out the possibility of translational frameshifting.8 It is assumed that no such translational or transcriptional frameshift takes place in the dnaX genes of Bacillus subtilis or other Gram-positive organisms, with only the full-length τ being produced.9 Although the domain organization of the E. coli τ protein has been studied in some detail,3,10,11 the domain organization of the B. subtilis protein is relatively unknown. A simple amino acid sequence comparison reveals that overall the two proteins share a high degree of identity in the first two-thirds of their sequences, that is equivalent to γ, but no homology in the last one-third that is equivalent to Cτ.9,12 Based upon these comparisons the B. subtilis proteins equivalent to E. coli γ and Cτ have been constructed encompassing residues 1–372 and 373–563, respectively.12 Another important difference is the presence of two different DNA polymerases in the B. subtilis DNA replication fork.13 The functional significance of these differences between Gram negative and positive organisms is not clear at present and several questions remain unanswered. (i) Why is there no need for the shorter γ protein in B. subtilis? (ii) Is the domain organization of the E. coli and B. subtilis τ proteins different? (iii) Is the DnaB–τ interaction mediated exclusively by an equivalent Cτ domain in B. subtilis, as is the case in the E. coli system? (iv) Is this interaction functionally and structurally equivalent in the two systems? (v) What is the architectural organisation of the complex? (vi) Can a translational or transcriptional frameshift event occur in the B. subtilis dnaX gene? Our data presented here address these important questions. We characterized the Bacillus τ–DnaB interaction in vitro using DnaB from Bacillus stearothermophilus and τ from B. subtilis (the choice of these proteins is fully justified by Haroniti et al.14) and showed that τ has a domain organisation similar to its E. coli counterpart. The interaction with DnaB is mediated by an equivalent Cτ domain and involves the C-terminal domain of DnaB. Our atomic force microscopy (AFM) images reveal that the complex involves a crescent-shaped τ oligomer interacting with a bell-shaped DnaB. We have already established that this interaction involves a pentameric τ interacting with a hexameric DnaB.14 The combined data from these studies offer the first insight into the structural organisation of this complex and allow us to build a structural model. The significance of the proposed model is discussed based upon these and previous data from the E. coli system.

Results and Discussion

Domain organisation of the Bacillus τ protein

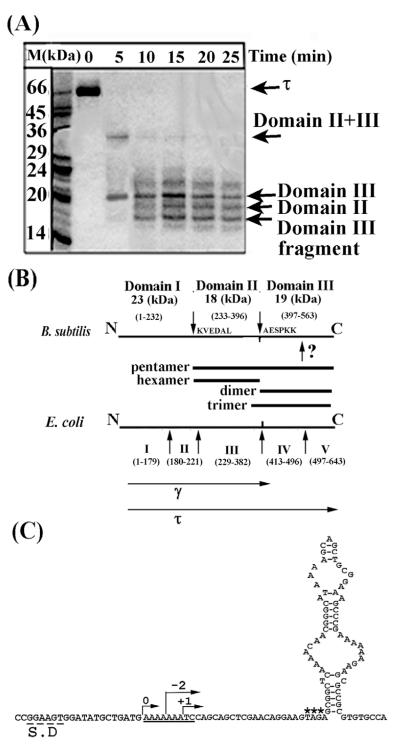

Using limited proteolysis, we identified two internal papain-sensitive sites that separate τ into three domains (Figure 1(A) and (B)). Furthermore, another proteolytic site within domain III implies that this domain has two sub-domains but we were unable to identify this site, as the domain III fragment obtained by proteolysis (Figure 1(A) and (B)) gave the sequence AESPKK at its N terminus. We cloned the equivalent gene fragments and over-expressed and purified the various domains (Figure 1(A) and (B)). The only exception was domain I, which, although over-expressed in large quantities, appeared in the insoluble fraction and despite our efforts to solubilise it we were unsuccessful (data not shown). A comparison with the amino acid sequence and domain organisation of the E. coli τ protein revealed broad similarities (Figure 1(B)). All the τ domains formed oligomers, as shown by gel-filtration (data not shown) and their oligomerisation properties are summarised in Figure 1(B). However, these data should be treated with caution, as gel-filtration is not an accurate method for determining oligomerisation states.14 Domain II is equivalent to domain III in E. coli (Figure 1(B)), which has been shown to be the major domain for the oligomerisation of the homo-tetrameric τ protein, converting to a heteropentamer in the presence of δδ′.15,16 Another important difference from the E. coli system is the apparent oligomeric state of the Cτ domain (consisting of domains IV and V in E. coli and domain III in B. subtilis). Cτ has been reported to be a monomer but in our case it appears as dimer. Another group showed independently the same apparent oligomeric state for the B. subtilis Cτ.12 A notable observation was the apparent difference in the oligomerisation states of domains III and IIIa, which differ only by 22 amino acid residues (Figure 1(B)). Domain IIIa was not identified by limited proteolysis but was instead defined by amino acid sequence comparisons between the E. coli and B. subtilis τ proteins. It contains 22 amino acid residues extra at its N terminus that include the important L381 discussed by Haroniti et al.14 This domain formed an apparent trimer compared to the dimer formed by the shorter domain III, highlighting the importance of this region in the organisation of the τ oligomer.14

Figure 1.

Domain organisation of the B. subtilis τ protein. (A) An SDS-PAGE gel showing proteolytic fragments of τ produced by limited proteolysis with papain over time. Arrows indicate the identified domains, as shown. (B) Diagrams showing the papain cleavage sites and comparing the domain organisation of the B. subtilis and E. coli τ proteins. Bars indicate all the domains that were constructed and purified. The γ and τ proteins are indicated. The unidentified papain site within domain III is indicated by a question mark. The molecular mass and apparent oligomerisation states of the domains are indicated. (C) Sequence elements in the B. subtilis dnaX gene that may mediate a translational frameshift event. The Shine–Dalgarno sequence is labelled S.D, the translational slippage signal is underlined, asterisks label the stop codon and a potential stem-loop structure is shown immediately downstream from the stop codon. Arrows indicate the correct frame 0 and −2, +1 frames that will result in premature termination.

Despite some differences in the oligomerisation states of individual domains, these data show a similar domain organisation for the E. coli and subtilis τ proteins and raise two important questions. (i) Why is there no need for a γ protein in B. subtilis, particularly since domains I and II together could constitute the γ version and (ii) is domain III the E. coli Cτ equivalent that interacts with DnaB? Upon careful examination of the dna X gene sequence near the boundary between domains II and III we detected a potential translational frameshift followed by a stop codon and a region of potential secondary structure (Figure 1(C)), raising the possibility that a similar translational frameshift may also operate in B. subtilis. It is intriguing that a Shine–Dalgarno sequence is present upstream from the frameshift signal and such sequences are thought to bind to 16 S rRNA and increase the frequency of the frameshifting events.17 Either a −2 or a +1 frameshift will result in encountering a stop codon at the base of the stem-loop secondary structure. Although −1 frameshifts are more common, +1 frameshifts are known to occur by slipping in widely diverse species.17 Obviously this is not definitive evidence that such a frameshift occurs in B. subtilis but demonstrates that all the necessary factors are present for the production of the shorter γ poly-peptide. The second question, whether domain III interacts with DnaB, was investigated by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) experiments utilising the various purified domains and His-tagged DnaB.

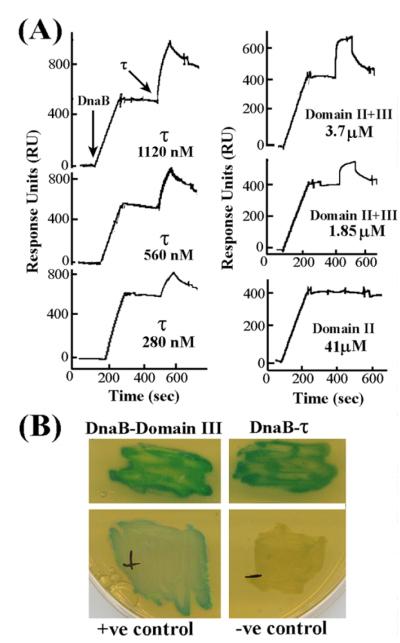

Investigating the τ–DnaB interaction by SPR and Y2H

The τ-DnaB interaction was investigated by immobilising His-tagged DnaB on the surface of a chip coated with nickel and then passing the various τ domains over it. Full-length τ generated a strong response at high nanomolar concentrations (280 nM, 560 nM and 1120 nM, referring to monomers) indicating a strong interaction (Figure 2(A)). Domain II + III also generated a good response but at low micromolar concentrations (1.85 μM and 3.7 mM, referring to monomers) indicating a weaker interaction with DnaB compared to full-length τ. Binding kinetic analysis for the DnaB–τ interaction revealed that the data fit well to a simple Langmuir 1:1 association model, assuming a hexamer:pentamer complex, with apparent Kd value of 2.3 nM. These data compare well with an apparent Kd of 4 nM reported for the DnaB–τ interaction in the E. coli system.11 Domain II did not interact with DnaB even at high micromolar concentration (41 μM, referring to monomers). Domain III was problematic, as it exhibited high non-specific binding to the Ni2+-coated chip even in the absence of immobilized DnaB, making it impossible to detect a specific interaction with DnaB (data not shown). Instead, the interaction of domain III with DnaB was confirmed by Y2H (Figure 2(B)). No stable interaction of any of the τ-domains with DnaB could be detected by gel-filtration experiments (data not shown). Our data do not rule out the possibility that domain I may be involved somehow in the DnaB interaction. The fact that domain II + III interacts more weakly than the full-length τ with DnaB may indicate involvement of domain I, or may be a consequence of a change in the shape of the oligomer that, in turn, affects its interaction with DnaB. At present, we cannot distinguish between these two possibilities. Nevertheless, our finding that domain III and not domain II is involved in the interaction with DnaB is in agreement with the finding that domain IV in E. coli (equivalent to domain III in B. subtilis) is the element interacting with DnaB.11

Figure 2.

Domain III of τ interacts with DnaB. (A) Sensograms from SPR experiments showing the interaction of τ and domain II + III at different concentrations (as indicated) with immobilized, His-tagged DnaB. Domain II does not interact with DnaB even at a very high concentration. The concentrations of the injected proteins are indicated and refer to monomers. Arrows indicate injection points. (B) Y2H analysis of τ–DnaB interactions showing full-length τ and domain III interacting with DnaB. Experimental details are described in Experimental Procedures.

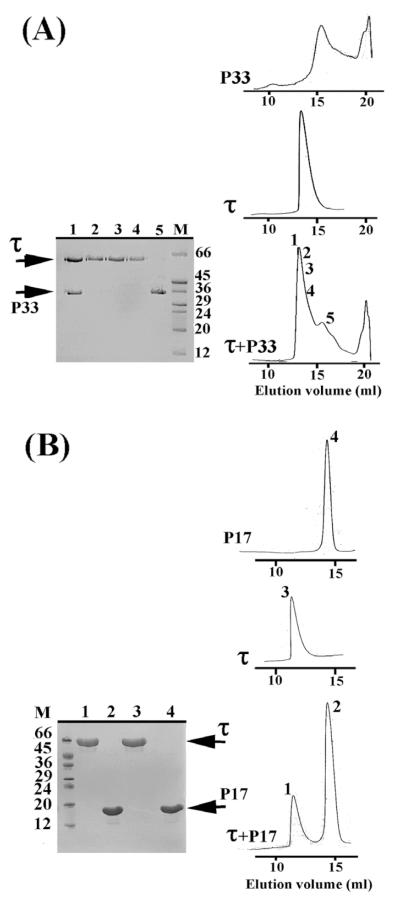

The τ protein interacts with the P33 domain of DnaB

Having established that domain III interacts with DnaB, we proceeded to investigate whether any of the previously identified P17 (N-terminal) and P33 (C-terminal) domains of DnaB can interact with τ. These domains were identified and constructed by sequence comparisons with the E. coli DnaB protein.18 We were able to detect and isolate a stable complex between the C-terminal P33 domain and τ by gel-filtration (Figure 3(A)). By comparison, P17 did not form a complex with τ under similar experimental conditions (Figure 3(B)). We established from our previous studies with the full-length proteins that the τ–DnaB complex dissociates at high ionic strength conditions, suggesting that the nature of the interaction is predominantly ionic.14 Therefore, the above experiments were carried out at low ionic strength conditions (100 mM NaCl). However, P33 has been shown to form hexamers only at high ionic strength conditions, whereas at 100 mM NaCl it exists as a mixture of lower oligomers.18 Despite this, P33 still interacted with τ, implying that the integrity of the helicase hexamer is not essential for its interaction with τ. The functional significance of this interaction in vitro was investigated further.

Figure 3.

DnaB interacts with τ via its P33 domain. Gelfiltration studies showing that, τ interacts with P33 (C-terminal domain) (A) and not with P17 (N-terminal domain) (B). Elution profiles of all the proteins are as indicated and SDS-PAGE gels verifying the presence of various proteins in relevant peaks are shown. The numbers of lanes in the gels correspond to the same numbers shown in elution profiles.

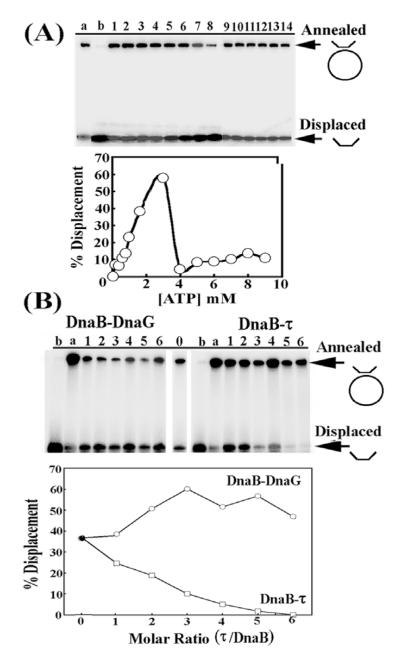

τ Inhibits helicase activity but does not affect the ATPase activity of DnaB in vitro

The activity profile of the B. stearothermophilus DnaB is dependent on the concentration of ATP, as ATP is inhibitory at high concentrations.18 Using a short oligonucleotide annealed onto ssM13 DNA, we established the helicase activity profile as a function of ATP concentration and showed that under our experimental conditions at concentrations of ATP up to 3 mM the helicase activity is stimulated and then inhibited sharply (Figure 4(A)). This helicase activity profile is consistent with our previous studies that showed a similar pattern for its ATPase activity profile.18 We then carried out helicase assays in the presence of increasing concentrations of τ using 2 mM ATP and found that the helicase activity was inhibited gradually reaching almost complete inhibition at molar ratios of τ to DnaB higher than 4:1, referring to pentamer:hexamer (Figure 4(B)). We investigated the nature of this inhibition by examining the effect of τ on the ATPase activity of DnaB and showed that τ has no effect either at 1:1 or at 9:1 molar ratios of pentamer:hexamer (data not shown). At this point we should make clear that no helicase and no ATPase activities could be detected for τ using our experimental conditions (data not shown). We conclude from these data that inhibition of the helicase activity is not the result of an inhibition of the ATPase activity. The molecular mechanism of this inhibition as well as its significance in vivo are unclear and apparently contradictory to previous reports that τ-mediated stimulation of DnaB is crucial for the fast progression of the DNA replication fork.19 One explanation, albeit speculative, might be that τ interacts with the replicative helicase in two different modes, a stimulatory mode once the processivity clamp has been loaded and an inhibitory mode just before the processivity clamp is loaded, thus slowing the helicase in preparation for clamp-loading. Our τ–DnaB complex may be mimicking the latter. Interestingly, the E. coli τ has been reported to possess a processivity switch that regulates the repeated loadings of the β clamp on the lagging strand20 and the same switch may regulate its interaction with the helicase. Of course, alternative explanations like the effects of other accessory replisomal proteins are equally plausible and it may be that the δ′γτ2δ pentamer interacts in a functional manner different from that of our τ pentamer.

Figure 4.

The effect of τ on DnaB activity in vitro. (A) The helicase activity of DnaB as a function of ATP concentration. Arrows indicate annealed (substrate) and displaced (product) oligonucleotides. Lanes 1–14 are presented as percentage displacement of annealed oligo-nucleotides as a function of ATP concentration. Increasing concentrations of τ inhibit DnaB. The data are shown also in graphical representation. (B) The helicase activity of DnaB as a function of increasing τ to DnaB molar ratio (pentamer:hexamer). For comparison, a control experiment of the helicase activity of DnaB as a function of increasing DnaG:DnaB (monomer:monomer) molar ratio is shown. Lanes 1–6 are presented as percentage displacement of annealed oligonucleotides as a function of increasing τ to DnaB molar ratio. Increasing concentrations of DnaG stimulate DnaB. Lanes a and b in both panels represent annealed and boiled controls, respectively.

The molecular architecture of the τ–DnaB complex

The structural information on the DnaB and τ proteins includes NMR and crystal structures for the N-terminal domain of the E. coli DnaB21,22 and a crystal structure of the E. coli clamp-loader with a truncated version of the γ protein complexed to δδ′.3 The crystal structure of the small subunit from the RFC of Pyrococcus furiosus23 also resembles the structure of the E. coli clamp-loader in terms of subunit architecture and packing, and previous AFM images of the eukaryotic RFC showed ATP-induced conformational changes related to the clamp loading mechanism.24 The structure of DnaB has been investigated with extensive microscopy studies establishing a bell-like structure with ATP-induced conformational changes.25,26 Currently, there is no structural information on the clamp-loader–helicase complex in any system.

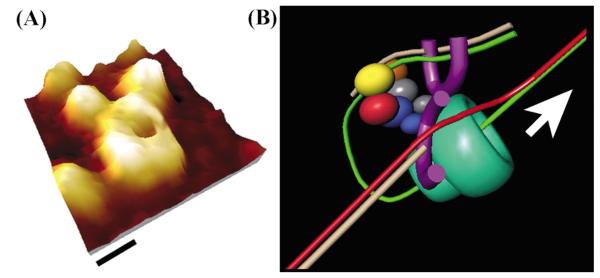

Using AFM, we obtained low-resolution images of our τ and DnaB proteins as well as their complex (Figures 5–7). It should be noted that in all images, larger field views were first obtained, before focussing upon features of interest. In each Figure we thus provide such larger field views, in addition to the higher-resolution images of individual complexes. A common observation in all of these images is that a range of different-sized features are observed, with relatively low numbers of large complexes (e.g. hexamers, or pentamers). This is not surprising when considering that the samples are air-dried onto the substrate prior to imaging. Indeed, one would expect to see a range of features corresponding to various disassembled forms of the respective complexes i.e. from the monomeric form to the fully intact complex. Consistent with this, within all images the smallest observed features were always comparable with the dimensions predicted for the respective monomeric proteins. However, only the largest observed multimeric complexes were considered for the present study (indicated by circled features), and subsequently analysed.

Figure 5.

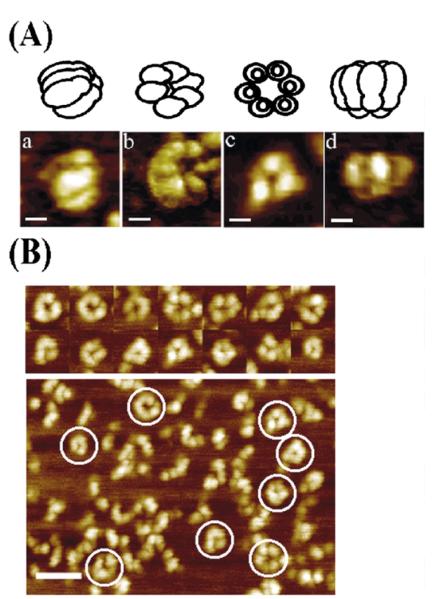

AFM images of DnaB. (A) Selected AFM images of DnaB adsorbed onto mica. Each image represents different views of DnaB observable with the AFM, as a result of alternative adsorption orientations and/or conformations onto the mica, along with models on top of each image for clarity. Images (phase) a and d, recorded with a nanotube AFM probe, show side-views of hexamers lying parallel with the surface. Image b (phase) shows a view of a partially tilted DnaB molecule with a 6-fold symmetry. Image c (topography) shows a “trimer of dimers” view down the 3-fold symmetry axis. For all images, the scale bars represent 10 nm. (B) Some representative examples (topography) of molecules viewed from a distance are shown together with a representative field view. The selected images shown in (A) are highly representative samples from a large number of field views obtained from many imaging experiments. The scale bar represents 50 nm.

Figure 7.

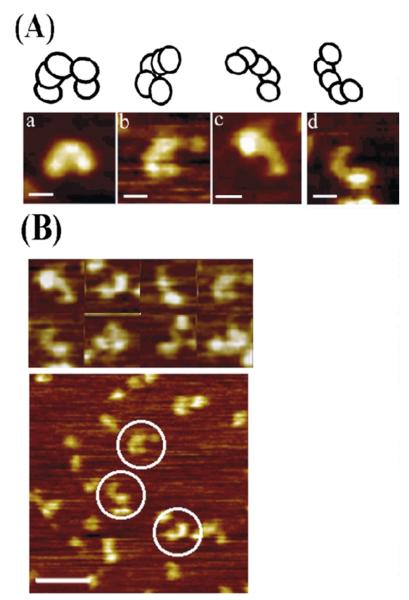

AFM topography images of the τ–DnaB complex. (A) AFM images of the τ–DnaB complex in different views with schematic models on top, showing possible orientations and/or conformations. For all images, the scale bars represent 10 nm. (B) Two representative examples of larger field views with molecules viewed from a distance are shown. By comparison with DnaB and τ images, the number of complexes observed was clearly lower (see the text for explanation). The scale bar represents 50 nm.

As expected from its amino acid sequence homology to the E. coli DnaB and from its similar domain organisation, the B. stearothermophilus DnaB forms bell-shaped hexamers with the narrow end of the bell containing the N-terminal and the wider end the C-terminal domains of the monomeric subunits (Figure 5(A)). The images shown in Figure 5(A) are highly representative images from numerous larger field views. Some representative distant images are shown in Figure 5(B). The use of some phase image data here is consistent with the work of Stark et al. that demonstrates the resolution of submolecular structural features on protein arrays.27 When considering AFM data it is important to note that the apparent dimensions of biomolecules are typically overestimated due to the convolution of the probe profile into the image data28 and compression effects of the imaging probe “flattening” the relatively soft molecule.29 The potential for molecular distortion due to the adsorption at the mica-solution interface must also be borne in mind. For interpretation of the data, it is nevertheless useful to estimate the effect of probe convolution through the use of software routines that extract the contribution of the probe, i.e. neglecting compression effects.30,31 In the case of DnaB, this reduces the observed molecular diameter from 25.5(±1.2) nm to approximately 22 nm. This compares with a diameter of approximately 15 nm observed by electron microscopy (EM) of negatively stained DnaB25,26 and cryoEM-based reconstructions of the E. coli DnaB–DnaC complex.32 This apparent difference between the EM analysis of the E. coli DnaB and our AFM analysis of the B. stearothermophilus DnaB may be due to differences in their hydration shells or from the different mechanisms of image formation, tip profiling compared to electron density contrast, the state of the DnaB during analysis, and the inability, as yet, to account quantifiably for molecular compression effects in AFM data. In addition, it is clear that in our data the molecules are adopting many different orientations and/or conformations at the mica-solution interface making averaging unsuitable. Despite this, we observed 3-fold, 6-fold and some open hexamers, in agreement with EM.

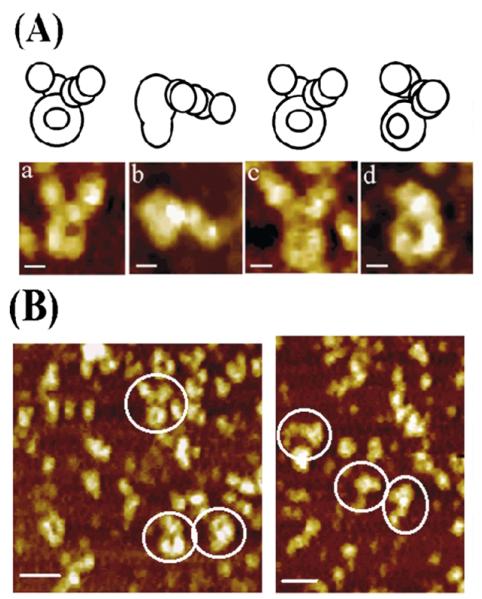

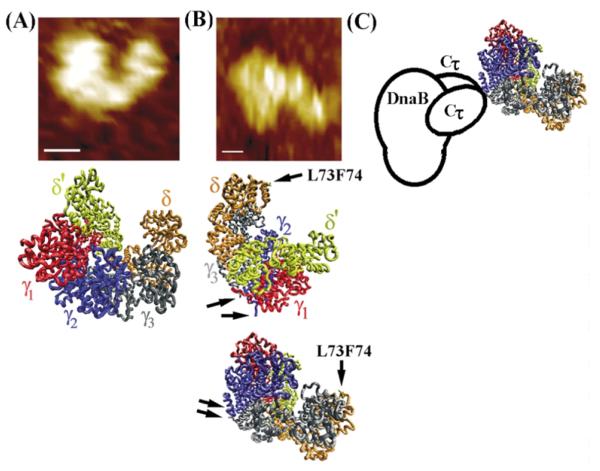

The B. subtilis τ protein forms a crescent-shaped structure (Figure 6(A)) that resembles the overall structures of the eukaryotic RFC24 and the E. coli γ complex.3 As for DnaB, the images shown in Figure 6(A) are highly representative images from numerous larger field views. Some representative distant images are shown in Figure 6(B). Accounting for probe convolution as for the DnaB reduces the observed size of the τ protein to within approximately 10% of the dimensions determined from the crystal structure of the E. coli γ complex. Images of the τ–DnaB complex showed the bell-shaped DnaB interacting with the crescent-shaped τ (Figure 7(A)). Compared to DnaB and τ images, relatively fewer images of the τ–DnaB complex were observed and those shown in Figure 7(A) are the best selected ones. Representative distant images for the complex are also shown in Figure 7(B). Lesser stability of the complex relative to the individual protein oligomers may be a reason for the low number of complexes observed. Imaging of the complex was carried out at lower concentrations to avoid over-crowding that might lead to non-specific aggregation. The interaction involves the wider end of the bell (C-terminal domains of DnaB) with both ends of the crescent projecting away from the bell. This is consistent with our earlier finding that τ interacts with the P33 (C-terminal) domain of DnaB. Our previous study14 showed that even in the absence of δδ′ τ forms pentamers that interact with the hexameric DnaB and therefore these crescent-shaped structures are likely to represent pentamers of τ. These pentamers are remarkably similar in their overall shape to the E. coli δ′γ3δ clamp–loader complex (Figure 8). It is likely that τ and the clamp–loader complex form very similar structures, particularly since the δ′δ subunits are structurally related to τ.

Figure 6.

AFM topography images of τ. (A) AFM images of τ in different views with schematic models on top, showing possible orientations and/or conformations. For all images, the scale bars represent 10 nm. (B) Some representative examples of molecules viewed from a distance are shown together with a representative field view. The selected images shown in (A) are highly representative samples from a large number of field views obtained from many imaging experiments. The scale bar represents 50 nm.

Figure 8.

The architecture of the τ–DnaB complex. (A) The shape of the B. subtilis τ protein resembles the E. coli clamp–loader complex. Comparison of the AFM topography image of τ (top) with the crystal structure of the clamp– loader complex (middle). (B) The architecture of the complex based upon the AFM topography image shown (top). Two possible orientations of the clamp-loader complex are shown. Arrows indicate the C-termini of the black and blue subunits (equivalent to τ1 and τ2, respectively) and the L73, F74 residues of δ that interact with the β clamp. (C) A model of the τ-DnaB complex. The clamp-loader interacts with the helicase via two Cτ domains of two τ subunits.

The E. coli clamp loader structure revealed that the δ′ and δ subunits are located at either end of a crescent-shaped complex defining a distinct polarity. Recent cross-linking studies revealed a polarity in the E. coli clamp loader defined as δ′γτ2τ1δ.33 By analogy, we can then define this polarity in the crystal structure of the clamp–loader complex (Figure 8(A)). The red subunit (γ1) will be equivalent to γ and the blue and black subunits (γ2, γ3) to τ2 and τ1, respectively. This analogy and a comparison of our images with the crystal structure of the clamp loader complex give us an insight into how the clamp-loader interacts with the helicase.

A number of structural features are consistent with this model. First the C-terminal ends of the blue (τ2) and black subunits (τ1) are positioned towards the helicase (see arrows in Figure 8(B)) and the Cτ domains that interact with the helicase are likely to project outwards and make contact with the helicase (Figure 8(C)). Obviously the spatial orientation of the Cτ domains relative to the other subunits is not known yet and also our images cannot define the Cτ of which τ subunit interacts with DnaB and in these respects the proposed model is speculative. The architecture of the τ–DnaB complex proposed here has another important topological consequence. Both δ′ and δ as well as γ are facing the opposite side from the view presented in Figure 8(A). The δ subunit that anchors the b clamp via its L73, F74 residues3,4 and δ′ will be located at the tips of the crescent pointing away from the helicase and ideally positioned to interact with β (Figure 8).

A model for the wider architecture of the replisome

Based upon our data and the extensive studies of the E. coli replisome, we propose a model for the wider architecture of the replisome including the replicative hexameric helicase (Figure 9). DnaB encircles the lagging strand translocating along in the 5′ –3′ direction and acts as a docking platform onto which the clamp–loader complex binds. The leading strand comes outside the helicase. The lagging strand goes through the helicase and loops back out through the clamp-loader ideally positioned for the repeated loadings of β required on this strand, as shown in Figure 9. Assuming some structural flexibility in the spatial position of the clamp-loader and/or the leading strand, the former could be adjusted to load β behind the leading-strand core polymerase if the need arises. The two core polymerases interact with one face of the two Cτ domains. This is consistent with previous studies that showed different interaction interfaces of Cτ with DnaB and α,10,11 and with our limited proteolysis studies that showed a two-subdomain structure for Cτ (see above). One of these sub-domains may interact with the helicase and the other with α. The γ subunit interacts with χψ, that in turn interact with SSB (not shown in Figure 9). Indeed, χψ interact exclusively with the γ in the natural holoenzyme,34 and χ associates with SSB.35,36 This may act as a communication bridge with the primase DnaG. In the E. coli system, the mode of action of the primase on the lagging strand is believed to be distributive,37 and its association with the primed site is the result of an interaction with SSB.38 The removal of the primase from the priming site signifies the switch from priming to polymerisation, and is mediated by the χ subunit that competes with the primase for SSB and displaces it from the primed site. This switch will be communicated to the clamp-loader on the lagging strand via the γ-χψ–SSB–DnaG interactions. Our model is consistent with the recent model suggested for the processivity switch mediated by Cτ during lagging-strand synthesis.20

Figure 9.

A model showing the organisation of the core-polymerase–clamp-loader–helicase complex. (A) A 3D topography reconstruction of the τ–DnaB complex (image a from Figure 7A). Based upon this and other images, a schematic model for the architecture of the clamp-loader helicase is shown in (B): the helicase (bell-shaped green) encircles the lagging strand (green) and translocates along the 5′ –3′ direction as indicated by the arrow. The Cτ domains project out of the two τ subunits (shown in grey and blue) “tag” the clamp-loader at the side of the helicase. The two core polymerases are shown in violet. Core 1 (front) and core 2 (back) for the leading (red) and lagging (green) strand, respectively, are on either side of the clamp-loader also interacting with the Cτ domains. The clamp-loader is ideally positioned to carry out repeated β-loading reactions on the lagging strand (as shown) but also on the leading strand if the need arises. The γ subunit (red) is situated towards the lagging-strand side forming a γ–χψ–SSB-DnaG communication pathway (not shown) for repeated priming/polymerisation switches required on this strand. The newly synthesized strands are shown in pale brown. The colour coding of the clamp-loader subunits are the same as in Figure 8 for comparison.

The complexity of replisome organisation makes it difficult to elucidate by X-ray crystallography. Microscopy offers an alternative and complementary approach and, although it provides low-resolution structural information, it is a powerful tool for elucidating the architecture of large macro-molecular assemblies. Our data present a unique insight into the structure of the bacterial clamp-loader–helicase complex and provide additional structural information towards our understanding of such a complicated molecular machine as the bacterial replisome.

Experimental Procedures

Limited proteolysis

Identification of distinct domains was carried out by limited proteolysis using trypsin, papain and subtilisin (Sigma). Proteolytic reactions were carried out using a 1:2000–5000 protease to τ molar ratios in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Samples were removed every five minutes and the protease was inactivated by addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer (1% (w/v) SDS, 2.5% (w/v) DTT, 01% (w/v) bromophenol blue and 10% (v/v) glycerol) and heating at 95 °C for five minutes prior to SDS-PAGE analysis. Protein fragments were identified by N-terminal protein sequencing, using an Applied Biosystems Inc. model 473A apparatus.

Construction of τ domains and His-tagged DnaB

All plasmid constructs carrying the domains were prepared by PCR of the appropriate gene fragments using the pET28adnaX14 plasmid as template, followed by cloning into the Nco I and Bam HI restriction sites of pET28a (Novagen). The initiation codon was provided by the ATG in the Nco I site and a stop codon was present just upstream from the Bam HI site. The forward and reverse cloning oligonucleotides used were:

5′-GATATCCTGCCATGGGGAAAGTCGAAGATGCGCTT-3′

5′-CGCAGCTGCGGATCCttaTTTTATGCCCGTTGT-3′

5′-GGCATAAAACCATGGCAGCTGCGGAAAGCCCG-3′

5′-CTCGAGTGCGGCCGCAAGCTTGTC-3′

5′-GATATCCTGCCATGGGGAAAGTCGAAGATGCGCTT-3′

5′-CTCG AGTGCG GCCGC AAGCT TGTC-3′

for domains II, III and II + III, respectively. A longer version of domain III (domain IIIa) including an extra 22 amino acid residues at the N terminus was constructed using the oligonucleotides:

5′-GAAGTGGATCCATGGGGCTGATGAAAAAAATC-3′

5′-CTCGAGTGCGGCCGCAAGCTTGTC-3′.

The Nco I site is shown in bold, underlined letters in all the forward primers, whereas the Bam HI site and the stop codon are shown in bold, underlined and italic letters, respectively, for the domain II reverse primer. The reverse primer used for all the other domains was downstream from the Bam HI site.

The plasmid construct carrying the His-tagged DnaB protein was prepared by excising the dnaB gene as an Nde I-HindIII fragment out of the pET22dnaB plasmid18 and inserting it in the same sites in the pET28a plasmid, thus creating a hexahistidine tag at the N terminus. The plasmids carrying the P17 and P33 fragments of DnaB were described elsewhere.18 His-tagged DnaB was indistinguishable from untagged DnaB as assessed by its oligomeric state (forms hexamers) and its unaffected biochemical function (ATPase, helicase and ssDNA-binding activities), (data not shown).

Protein purifications

The DnaB, τ and DnaG proteins were prepared as described.14,18 The P17 and P33 (N and C domains of DnaB were purified as described.18 The His-tagged DnaB was overexpressed in BL21 (DE3) E. coli cells. The protein was purified by a combination of a 5 ml His-Trap column loaded with nickel (Amersham), as recommended by the manufacturer, followed by gel-filtration through a Superose 6 column equilibrated with 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 100 mM NaCl. The relevant fractions were pooled, made to 10% glycerol, fast-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Overexpression of the τ domains, subsequent sonication and clarification of the supernatants were as described for the full-length τ-protein. Domain I of τ overexpressed in the insoluble fraction and our efforts to solubilise it failed. Thus we did not purify this domain. For all the other domains, the protein pellet was then dissolved in buffer B (50 mM glycine (pH 9.5), 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) and the conductivity of the solution was adjusted to 6–8 mS prior to loading onto a HiTrapQ column, equilibrated in buffer B. The protein was eluted through a linear salt gradient (0–0.8 M NaCl) over 120 ml at 3 ml/minute. Fractions containing the relevant protein were pooled and the conductivity adjusted to 6–8 mS prior to loading onto a MonoQ column, equilibrated in buffer B. The protein was eluted through a linear salt gradient (0–0.4 M NaCl) over 105 ml at 3 ml/minute. Fractions containing the relevant protein were pooled and the protein was precipitated with (NH4)2SO4. The protein pellet was dissolved in 5 ml of buffer A (50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) plus 100 mM NaCl and applied onto a preparative Superdex S-75 gel-filtration column equilibrated in the same buffer. The relevant fractions were pooled, made to 10% (v/v) glycerol, and fast-frozen as small portions in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. All proteins were >98% pure as assessed by SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue (data not shown).

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

The SPR experiments were carried out in a BIAcoreX instrument (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden), using a microfluidic cartridge linked to two identical flow cells (Fc1 and Fc2) within a nitrilotriacetate (NTA) chip. Fc2 was loaded with Ni2+ by injecting 0.5 mM NiCl2 in eluent buffer (20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 50 μM EDTA, 0.005% (v/v) surfactant P20). His-tagged DnaB was captured reversibly onto Fc2, by injecting 60 nM DnaB (referring to hexamers) in eluent buffer plus 25 mM imidazole. Fc1 was used as reference for all injections and all non-specific signals were subtracted from the signals observed in Fc2. This concentration of DnaB was chosen to give a consistent response without saturating the matrix (100–500 RU). All τ domains and full-length protein (at various concentrations, as indicated) were injected at 20 μl/minute in eluent buffer plus 25 mM imidazole. Faster flow-rates were used to check that the response is consistent over a range of flow-rates, thus eliminating any effects on the data by mass transfer (data not shown). At the end of each experiment, the chip was regenerated, by injecting eluent buffer with 3 mM EDTA before the next injection. All solutions used were filtered and degassed under vacuum. Data were evaluated using BIAevaluation 3.0.2 (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Qualitative comparisons were carried out by aligning overlayed sensograms at the injection start point on the X-axis and zeroing the baseline on the Y-axis at this point. Basic quantitative binding kinetic analysis was carried out only for the DnaB:t interaction assuming a 1:1 Langmuir association model. The precise stoichiometry of the domain II + III:DnaB complex is not known and this makes a similar analysis complicated. These experiments were intended only to determine which τ-domain interacts with DnaB rather than to determine accurate kinetic data.

Yeast-two hybrid (Y2H)

The Y2H experiments were carried out using the MATCHMAKER Two-Hybrid system 2 from Clontech. The dnaX gene and the fragment carrying domain III of τ were cloned as Nco I-Xho I fragments in the same sites of pACT2, while DnaB was cloned as an Nco I-Xho I fragment in the Nco I-Sal I sites of pAS2-1. The positive control is based upon the p53-simian virus 40 (SV40) τ antigen interaction using the pAV3-1 plasmid carrying the GAL4 DNA-binding domain fused to murine p53 and a trp nutritional selection marker, and the pTD1 plasmid carrying the GAL4 activation domain fused to the SV40 large T antigen and a leu nutritional selection marker. The negative control shows that there is no interaction between DnaB and SV40 large T antigen, using the pAS2-1-DnaB and pTD1 plasmids, described above. All plasmids were transformed into yeast by electroporation as described,39 and the detection of positive interactions was carried out by the agarose overlay method.40

Gel-filtration

The interaction of τ with the P17 and P33 domains of DnaB was studied by gel-filtration using the Superdex S200 10/30 and Superose 6 10/30 columns, respectively. P33 4.54 μM (monomers) and τ 3.1 μM (monomers) proteins were mixed in 40 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 100 mM NaCl and left at room temperature for ten minutes before being loaded onto the column equilibrated in the same buffer. Buffer was pumped through the column at 0.5 ml/minute and 0.5 ml fractions were collected. Control experiments using P33 and τ proteins alone were carried out in an identical manner. Samples from the peaks were analysed by SDS PAGE and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. The interaction of P17 (22. 5 μM) with τ (11.68 μM) was studied in a similar manner using τ and P17.

Helicase assays

The DnaB helicase activity was assayed by monitoring the displacement of a short radiolabelled oligonucleotide annealed onto ssM13mp18 DNA, as described.41 Briefly, reactions were carried out in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 20 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 2 mM ATP, 1.15 nM DNA substrate (one molecule of DNA substrate is defined as one molecule of M13 ssDNA with one molecule of radiolabelled oligonucleotide annealed to it), 115.5 nM DnaB (referring to hexamers and equivalent to approximately one hexamer per 72 nucleotides of M13 ssDNA) at 37 °C for 30 minutes. The effect of τ on the DnaB helicase activity was examined by adding increasing concentrations of τ in the reaction mixture, thus increasing the τ:DnaB molar ratio (pentamer to hexamer), as indicated. A control reaction under identical conditions using the primase DnaG, shown to stimulate DnaB,18 was carried out for comparison. These reactions were carried out for 30 minutes at 37 °C. All other experimental details were as described.41 No displacement activity could be detected for τ under our experimental conditions.

ATPase assays

The ATPase activity of DnaB was assayed by linking it to NADH oxidation, using 10 nM DnaB (referring to hexamers) at varying concentrations of ATP, as described.40 The effect of τ on the activity of DnaB was measured by mixing the two proteins for ten minutes at room temperature, prior to adding them into the reaction mixture. Small and large amounts of τ(8.3 nM and 66 nM, referring to pentamers) were used to examine the effect at roughly equimolar ratio of hexamer (DnaB):pentamer (τ) and at high excess of τ.

Atomic force microscopy

Protein samples dissolved in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol were typically diluted to between 10 μg/ml and 85 μg/ml in dilution buffer, (the same buffer without glycerol). Samples (15–20 μl) were incubated with freshly cleaved mica (Agar Scientific) for two to ten seconds, rinsed with 5 ml of distilled water and allowed to dry under a gentle flow of nitrogen gas. The shorter incubation times were typically utilized for more highly concentrated samples, to prevent excess surface coverage of the protein. AFM was conducted in air at room temperature, with a scanning rate typically between 1.5 Hz and 2.5 Hz in tapping mode using a Nanoscope IIIa with a type E scanner (Veeco, Bicester, UK). The cantilevers used were silicon tapping probes with a spring constant of 34.4–74.2 N/m (Olympus, OMCL-AC160TS). The tapping set-point was adjusted to minimise probe-sample interactions. To provide the maximum possible resolution, carbon nanotube AFM probes, fabricated in-house, were also utilised where specified. Images were recorded in both topography and phase modes with a pixel size of 512 × 512, flattened and analysed with WSxM software 3.0 Beta 2.3 (Nanotec Electronica S.L, Spain). Tip profile derivation was executed using SPIP Metrology software package (Image Metrology, Denmark).

Acknowledgements

We thank Kevin Bailey for N-terminal protein sequencing and Dr Kevin Brady for help with Figure 9. This work was supported by the BBSRC (42/B15519 grant to P.S.) and the Wellcome Trust (064751 grant to P.S.). S.A. is a Pfizer Global Research and Development Lecturer, C.A. and A.H. are postgraduate students, supported by the BBSRC and a University of Nottingham Research Scholarship, respectively. Carbon nanotube AFM probes were developed through an EPSRC Metrology for Life Sciences Programme project. We thank Dr Janet Jacobs for help preparing the carbon nanotube probes.

Abbreviations used

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- Y2H

yeast two-hybrid

- EM

electron microscopy

References

- 1.Blinkowa AL, Walker JR. Programmed ribosomal frameshifting generates the Escherichisa coli DNA polymerase III gamma subunit from within the tau subunit reading frame. Nucl. Acids Res. 1990;18:1725–1729. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.7.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsuchihashi Z. Translational frameshifting in the Escherichia coli Dnax gene in vitro. Nucl. Acids Res. 1991;19:2457–2462. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.9.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeruzalmi D, O’Donnell M, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the processivity clamp loader gamma (γ) complex of E. coli DNA polymerase III. Cell. 2001;106:429–441. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeruzalmi D, Yurieva, Zhao Y, Young M, Stewart J, Hingorani M, et al. Mechanism of processivity clamp opening by the δ subunit wrench of the clamp loader complex of E. coli DNA polymerase III. Cell. 2001;106:417–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellison V, Stillman B. Opening of the clamp: an intimate view of an ATP-driven biological machine. Cell. 2001;106:655–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00498-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flower AM, McHenry CS. The γ subunit of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme of Escherichia coli is produced by ribosomal frameshifting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:3713–3717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yurieva O, Skangalis M, Kuriyan J, O’Donnell M. Thermus thermophilis dnaX homolog encoding γ- and τ-like proteins of the chromosomal replicase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:27131–27139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen B, Wills NM, Nelson C, Atkins JF, Gesteland RF. Nonlinearity in genetic decoding: homologous DNA replicase genes use alternatives of transcriptional slippage or translational frameshifting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1683–1688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruck I, O’Donnell M. The replication machine of a Gram-positive organism. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:28971–28983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003565200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao D, McHenry CS. τ binds and organizes Escherichia coli replication proteins throughdistinct domains. Partial proteolysis of terminally tagged τ to determine candidate domains and assign domain V as the τ binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:4433–4440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009828200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao D, McHenry CS. τ binds and organizes Escherichia coli replication proteins through distinct domains. Domain IV, located within the unique C terminus of τ, binds the replication fork helicase, DnaB. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:4441–4446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez-Himenez MI, Meas P, Alonso JC. Bacillus subtilis τ subunit of DNA polymerase III interacts with bacteriophage SPP1 replicative DNA helicase G40P. Nucl. Acids Res. 2002;30:5056–5064. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dervyn E, Suski C, Daniel R, Bruand C, Chapuis J, Errington J, et al. Two essential DNA polymerases at the bacterial replication fork. Science. 2001;294:1716–1719. doi: 10.1126/science.1066351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haroniti A, Till R, Smith MCM, Soultanas P. The clamp-loader-helicase interaction in Bacillus. Leucine 381 is critical for pentamerisation and helicase binding of the Bacillus τ protein. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10955–10964. doi: 10.1021/bi034955g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glover BP, Pritchard AE, McHenry CS. τ binds and organizes Escherichia coli replication proteins through distinct domains. Domain III shared by γ and τ oligomerizes DnaX. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:35842–35846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pritchard AE, Dallmann GH, Glover BP, McHenry CS. A novel assembly mechanism for the DNA polymerase III holoenzyme DnaX complex: association of δδ′ with DnaX4 forms DnaX3δδ′. EMBO J. 2000;19:6536–6545. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farabaugh PJ. Programmed translational frameshifting. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1996;30:507–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bird LE, Pan H, Soultanas P, Wigley DB. Mapping protein:protein interactions within a stable complex of DNA primase and DnaB helicase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Biochemistry. 2000;39:171–182. doi: 10.1021/bi9918801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S, Dallmann HG, McHenry CS, Marians KJ. Coupling of a replicative polymerase and helicase: a τ–DnaB interaction mediates rapid replication fork movement. Cell. 1996;84:643–650. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leu FP, Georgescu R, O’Donnell M. Mechanism of the E. coli τ processivity switch during lagging strand synthesis. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:315–327. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fass D, Bogden CE, Berger JM. Crystal structure of the N-terminal domain of the DnaB hexameric helicase. Structure. 1999;7:691–698. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weigelt J, Brown SE, Miles CS, Dixon NE, Otting G. NMR structure of the N-terminal domain of E. coli DnaB helicase: implications for structure rearrangements in the helicase hexamer and its biological function. Structure. 1999;7:681–690. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oyama T, Ishino Y, Cann IKO, Ishino S, Morikawa K. Atomic structure of the clamp loader small subunit from Pyrococcus furiosus. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:455–463. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiomi Y, Usukura J, Masamura Y, Takeyasu K, Nakayama Y, Obuse C, et al. ATP-dependent structural change of the eukaryotic clamp-loader protein, replication factor C. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:14127–14132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu X, Jezewska J, Bujalowski W, Egelman EH. The hexameric E. coli DnaB helicase can exist in different quaternary states. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;259:7–14. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang S, Yu X, Vanloock MS, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W, Egelman EH. Flexibility of the rings: structural asymmetry in the DnaB hexameric helicase. J. Mol. Biol. 2002:839–849. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00711-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stark M, Möller C, Müller DJ, Guckenberger R. From images to interactions: high-resolution phase imaging in tapping-mode atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2001;80:3009–3018. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76266-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams PM, Davies MC, Jackson DE, Roberts CJ, Shakesheff KM, Tendler SJB. Toward true surface recovery: studying distortions in scanning probe microscopy image data. Langmuir. 1996;12:3468–3471. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X, Davies MC, Roberts CJ, Tendler SJB, Williams PM, Davies J, Dawkes AC. Attractive tapping: a method to minimise topography distortions in tapping mode atomic force microscopy. Probe Microsc. 2001;2:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitching S, Williams PM, Davies MC, Roberts CJ, Tendler SJB. Quantifying surface topography and scanning probe image reconstruction. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 1999;17:273–279. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts CJ, Davies MC, Tendler SJB, Williams PM, Davies J, Dawkes AC, et al. The discrimination of IgM and IgG type antibodies and Fab’ and F(Ab)2 antibody fragments on an industrial substrate using scanning force microscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 1996;62:149–155. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(95)00143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin C. San, Radermacher M, Wolpensinger B, Engel A, Miles CS, Dixon NE, Carazo JM. Three-dimensional reconstructions from cryo-electron microscopy images reveal an intimate complex between helicase DnaB and its loading partner DnaC. Structure. 1998;6:501–509. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bullard JM, Pritchard AE, Song MS, Glover BP, Wieczorek A, Chen J, et al. A three-domain structure for the † subunit of the DNA polymerase III holoenzyme † domain III binds δ′ and assembles into the DnaX complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:13246–13256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108708200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glover BP, McHenry CS. The DnaX-binding subunits δ′ and ψ are bound to γ and not τ in the DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:3017–3020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelman Z, Yuzhakov A, Andjelkovic J, O’Donnel M. Devoted to the lagging strand, the subunit of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme contacts SSB to promote processive elongation and sliding clamp assembly. EMBO J. 1998;17:2436–2449. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glover BP, McHenry CS. The χψ subunits of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme bind single-stranded DNA binding protein (SSB) and facilitate replication of an SSB-coated template. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23476–23484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu YB, Ratnakar PVAL, Mahanty BK, Bastia D. Direct physical interaction between DnaG primase and DnaB helicase of Escherichia coli is necessary for optimal synthesis of primer RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:12902–12907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuzhakov A, Kelman Z, O’Donnell M. Trading places on DNA: a three-point switch underlies primer hand off from primase to the replicative DNA polymerase. Cell. 1999;96:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80968-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker DM, Guarente L. High-efficiency transformation of yeast by electroporation. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:182–187. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dumay H, Rubbi L, Sentenac A, Marck C. Interaction between yeast RNA polymerase III and transcription factor TFIIIC via ABC10α and τ131 subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:33462–33468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soultanas P, Wigley DB. Site-directed mutagenesis reveals roles for conserved amino acid residues in the hexameric DNA helicase DnaB from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Nucl. Acids Res. 2002;30:4051–4060. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]