Abstract

Context

Adolescent pregnancy prevention is difficult because sex itself is intermittent, occurring after days, weeks or months of abstinence. An understanding of why sexually experienced adolescents decide to have sex after a period of abstinence will allow clinicians to better tailor counseling.

Methods

For up to 4.5 years, 354 adolescent women were interviewed and STI tested every three months, and asked to complete 3 months of daily diaries twice a year. We examined periods of abstinence in the daily diaries, using survival analysis to estimate the effect of intrapersonal, relationship, and STI-related factors on the risk of ending an abstinence period with sex.

Results

Participants reported 9236 abstinence periods, mean 30.9 days. Shorter, intermediate and longer abstinence periods were identified from the cumulative hazard plot. The risk of ending a shorter abstinence period increased with age (Hazard Ratio = 1.07), sexual interest (HR = 1.14), positive mood (HR = 1.03), daily partner support (HR=1.14), quarterly relationship quality (HR=1.02) and distant STI (HR=1.16); the risk decreased with negative mood (HR=0.98) and recent STI (HR=0.91). During intermediate periods the association with recent STI switched directions (HR=1.40). Longer periods showed associations only with age (HR=1.24), sexual interest (HR=1.33), and relationship quality (HR=1.10).

Conclusions

Intrapersonal, relationship, and STI related factors influence the decision to have sex after a period of abstinence. The direction and strength of these associations varied with the length of abstinence, highlighting the importance of a young woman's recent patterns of sexual activity.

Keywords: Sexual Abstinence, Adolescent, Sexually Transmitted Disease, Sexual Behavior, Affect, Survival Analysis, Sexual Desire, Sexual Partner

Introduction

Counseling sexually experienced adolescent women about pregnancy and STI prevention is difficult because sex itself is often intermittent, occurring after days, weeks or months of abstinence. These periods constitute abstinence in that no sexual activity occurs and, often, none is planned or anticipated (see, for example, Loewenson, 2004).1 What exactly constitutes “abstinence” is poorly defined across research, program, policy and clinical realms.2-4 There is no consistency in what length of time without sex is needed to be “abstinent,” which behaviors are included or excluded in “abstinence,” or whether it is not a question of behavior, but of intention and motivation.5-7

The large public investment in “abstinence-only” sexuality education has diminished curricular attention given to topics that are of greater relevance to adolescents with sexual experience, such as contraception, condom use and decision-making about sex within relationships.8 Additionally, there exists such a strong socio-cultural and clinical emphasis on first sex as both transformative and risky, that many adolescents themselves say that sexual experience precludes abstinence.7 Yet, abstinence is still relevant to sexually experienced adolescents: several studies show that 10% to 20% of sexually experienced adolescents report no sexual intercourse within the past 3-6 months.9-11 Few prevention programs or clinical guidelines take into account the varying patterns of sexual abstinence among sexually experienced adolescent women. From a clinical perspective, these data are needed to permit clinicians to better target abstinence and sexuality counseling.

Influences on general adolescent sexual decision-making have been well studied. Three areas of importance are intrapersonal factors, such as mood and sexual interest,12, 13 relationship factors, such as intimacy and relationship quality,14, 15 and STI-related factors, such as risk perception and recent infection.9, 16 These three areas of importance (interpersonal, relationship, and STI-related) are drawn from attribution theory, which describes an interaction between intrapersonal attributes and emotions, and interpersonal and other situational contexts (e.g. STI).17 While the above influences have been closely examined for first sexual experiences, less is known about how these factors influence the decision to have sex again after different length periods of abstinence. Our objectives were: (1) To describe intrapersonal, relationship and STI-related factors on the risk of having sex after a period of abstinence among high risk adolescent women; and (2) to examine whether these factors differ for periods of abstinence of varying duration.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

As part of a larger cohort study of STI, 354 adolescent women were enrolled from primary care clinics, and were followed for up to 4.5 years of observation time between 1999 and 2006. The clinics serve primarily low and middle income urban communities with high rates of early sexual onset and STIs,18 representing a population of particular interest for STI and pregnancy prevention. Inclusion criteria included female gender, ages 14.0-17.9 years at enrollment, and not pregnant. Sexual experience was not an inclusion criterion, although 80.5% of participants were sexually experienced at enrollment, and 19.5% of participants initiated sexual intercourse during the study. Each adolescent provided written consent and parents provided written permission. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Indiana University Purdue University at Indianapolis–Clarian.

The larger study utilized both quarterly interviews and 3 month periods of daily diary collection (for a detailed description of study procedures, see Fortenberry, 2005 and Ott, 2008).12, 19 Each 3 month diary collection period was initiated and terminated by a quarterly interview and was followed by a rest period of similar length, providing two diary collection periods per year. For this analysis, we use data for up to 4.5 years of observation time. The face-to-face interviews covered a range of partner-specific behaviors and relationship attributes.

Measures

Measure choice was influenced by clinical relevance and previous empirical data, 9,12-16 and draws from attribution theory.17

Abstinence periods

We defined an abstinence period as one or more consecutive days of no vaginal sex reported on daily diaries. Abstinence periods started the day after a diary report of sex and ended with a diary report of sex. They were censored by either a missing diary day or by the start or end of a diary period. We used abstinence periods as our unit of analysis, and a single participant could contribute multiple abstinence periods. We note that abstinence periods are behaviorally defined, and do not encompass motivations, attitudes or moral characteristics that are a part of the literature on adolescent abstinence.7 To retain our focus on sexually experienced adolescents, abstinence periods prior to or ending in a first episode of vaginal sex (coital debut) were omitted from the analysis. Censoring was common: 37% of all abstinence periods, and 92 % of longer abstinence periods (>39 days) were censored.

Intrapersonal factors

Intrapersonal factors included daily positive mood, daily negative mood, and sexual interest. The positive mood scale consisted of 3 items, (α = .81, range 3-15) asking whether the participant had felt cheerful, happy or friendly that day.12 The negative mood scale consisted of 3 items (α = .76, range 3-15) asking whether the participant had felt irritable, angry or unhappy that day.12 All mood and sexual interest items used a 5 point Likert-type response scale ranging from “not at all” to “all day.” Sexual interest was measured by a single item with the above 5 point response scale, asking whether the participant was interested in having sex at any point during that day.12

Our only data on an individual's contraceptive motivation for abstinence was a single question on a subset of interviews asking whether participants used sexual abstinence to avoid pregnancy.a Only 10 of the 108 participants (9%) asked this question reported using abstinence to avoid pregnancy. The subset was too small to include in the larger analysis.

Relationship factors

Partner-specific relationship factors were measured on two levels: daily partner support, and quarterly relationship quality. At enrollment and each follow-up visit, participants were asked to identify sex partners by first name or initial in order to examine partner-specific attitudes and behaviors within a specific interview or diary. Daily partner support consisted of 4 items (α=0.86, range 0-4) assessing occurrence on that day (no or yes) of the following interactions: “We talked about my feelings”; “He let me know he cared about me”; “He made me feel loved”; and “He made me feel special.” Higher scores indicating greater partner support for the day.

Quarterly relationship quality consisted of 6 items (α=0.91, range 6-24), that assessed positive emotional and affiliational aspects of a relationship. Participants were asked to respond on a 4 point Likert-type scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) to items such as, “We have a strong emotional relationship,” and “He is a very important person in my life.” Because of misspellings of partners- first names in the diary data, we were unable to link the partner listed in quarterly interview to the partner in the diaries, and therefore chose to use relationship quality reported for the first partner listed on the interview. This is a reasonable approximation, as participants listed only one sexual partner for 99.6% of diaries where sex was reported and 83.1% of interviews where participants reported the number of sexual partners.

Sexually transmitted infections

Participants were tested for C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, and T. vaginalis using PCR on self- or provider-collected vaginal swabs at enrollment and quarterly visits. We defined a “recent STI” as one of the above three infections diagnosed in the quarterly visit at the start of the diary collection period. We defined a “distant STI” as occurring in any quarterly interview prior to the most recent quarterly interview. We differentiated between “recent” (i.e. diagnosed at their last clinic visit) and “distant” (having an STI diagnosed more than 3 months ago) STI because previous research by our group has shown that temporary periods of abstinence are a common response to a new STI diagnosis. 9

Analysis

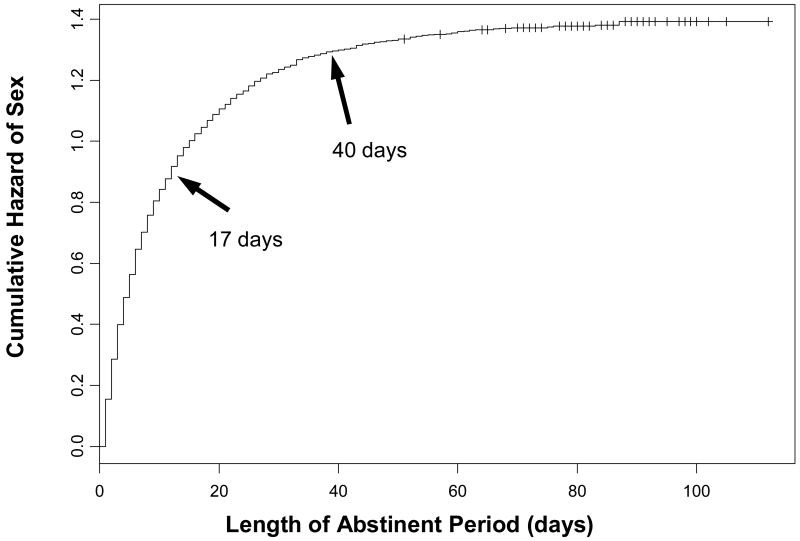

We used a survival analysis approach to examine the length of abstinent periods. First, we plotted the cumulative hazard of abstinent periods (i.e. the time to sex after a period of abstinence). We identified three distinct sections of the cumulative hazard plot with three different slopes. We divided abstinent periods into 3 groups based upon these three distinct sections, which we labeled, shorter (<17 days), intermediate (17 days-39 days), and longer (40 days-112 days) abstinence periods. Abstinent periods longer than the diary collection period (3 months) were treated as censored, which limited our ability to examine even longer periods of abstinence.

We tested each of these groups for associations between the time to sex and intrapersonal, relationship and STI-related variables using frailty models. Frailty models are proportional hazard models controlling for multiple observations from each participant, and were used to estimate the effect of intrapersonal, relationship and STI_related factors on the risk, or hazard, of ending shorter, intermediate, and longer abstinence periods.20 In contrast to survival models, which estimate the population average hazard of an event (in our case, sex ending an abstinence period), frailty models estimate the within-subject hazard, by incorporating into the model each participant's own risk for having sex. This allowed us to examine, within individuals, how specific behaviors are related, rather than examining differences in behaviors between groups of individuals. A separate model was used for each intrapersonal, relationship, and STI-related factor.

Sensitivity Analyses

We performed three sensitivity analyses. First we examined the influence of missing diary data. In our analyses, we considered diaries missing the sexual intercourse item or missing daily diaries as censored. To examine whether this approach influenced results, we imputed missing data, ran the models, and compared results from the models using imputed missing data to those counting missing data as censored. The imputation of missing sexual event data was performed by comparing a random number generated from a uniform distribution to the subject-specific daily probability of having sex. If the subject-specific probability was less than the random number, then a sexual event was imputed. Compared to the original models, the models using imputed data had fewer censored abstinence periods (30% versus 39%), but similar associations with intrapersonal, relationship, and STI-related influences. Because randomly censored data should not influence our point estimate but instead cause wider confidence intervals,20 and our imputations did not suggest systematic missing data, for our final models, we treated missing diary days as censored.

Second, we examined the influence of the length of the abstinence period on results. We examined how using just 2 groups influenced results, and performed these analyses using 2 different cut-points (14 days and 21 days). For both cut-points, we observed similar results with age, intrapersonal factors, and relationship factors. Recent and distant STI showed similar associations with shorter and longer periods, but the intermediate-length findings were lost by only having one cut-point. We chose to use the empirically derived three groups (<17 days, 17-39 days, 40+ days) as the results for the shorter and longer periods were robust at several different cut-points, and we were able to examine the intermediate periods.

Third, we examined the possibility that pregnancy may influence models of longer length abstinence periods. From a quarterly interview question asking about whether the participant was currently pregnant, we identified 670 (out of 9236) abstinence periods in which the participant was pregnant. We compared censoring during periods in which the participant was pregnant (29% censored) and for all abstinence periods (37%). We then re-ran the models excluding abstinence periods in which the participant was pregnant. Associations with intrapersonal, relationship, and STI-related factors in models excluding pregnancy were similar to results using all data, so we used all data.

Results

Participants

Participants were 90% African American, 8% white, and 2% other or multi-racial. The mean number of diary days contributed by a participant was 334 days (range of 5 to 783 days). The average daily completion rate per participant per diary period was 95.6% (SD, 10.0%). Other analyses have not shown significant bias in diary completion and item non-response within returned diaries.12

Mean at the start of diary periods was 17.3 years (SD 1.1 years). (See table 1). On an intrapersonal level, mean daily positive and negative mood were 9.2 (SD 3.6) and 5.7 (SD 2.9), respectively. Mean daily sexual interest was 1.6 (SD 1.1). On a relationship level, daily partner support was 1.9 (SD 1.1), and quarterly relationship quality was 19.5 (SD 1.1). Participants were diagnosed with an STI at the start of 17% of diary periods, and had a history of an STI in 63% of diary periods.

TABLE 1. Description of Intrapersonal, Relational and STI-related Factors by Diary Period.

| Mean (SD) or Percent | |

|---|---|

| Age | 17.3 (1.8) |

| Daily Positive Mood | 9.2 (3.6) |

| Daily Negative Mood | 5.7 (2.9) |

| Daily Sexual Interest | 1.6 (1.1) |

| Daily Partner Support | 1.9 (1.7) |

| Quarterly Relationship Quality | 19.5 (3.9) |

| Recent STI | 17.1% |

| Distant STI | 63.1% |

Note: 354 participants contributed 1573 3-month periods of diary collection. Within each diary period, they could have one or more abstinence periods.

Abstinence Periods

The 354 participants contributed 9236 abstinence periods. Of these periods, 63% ended with a diary report of sex, and 37% were censored by either a missing diary day, or the start or end of a diary period. The mean length of an abstinence period was 30.9 days (standard error, 0.58 days), the median length was 7 days (95% CI 6, 7 days) and the range was 1 to 112 days.

The cumulative hazard plot of time to sex ending an abstinence period is shown in Figure 1. The slope showed a steep increase in risk for shorter periods (< 17 days), a less steep increase for intermediate periods (17-39 days), and a fairly steady risk for longer period (40-112 days).

Figure 1. Cumulative Hazard Plot.

Cumulative hazard of sex after different length periods of abstinence. Arrows mark inflection points dividing shorter, intermediate, and longer length abstinent periods.

Intrapersonal, Relational, and STI-related Factors

Table 1 shows a summary of intrapersonal, relationship and STI factors for the first day of the first abstinence period for each diary period. Table 2 shows the results of univariate frailty models for the risk of sex ending an abstinence period as related to each of the intrapersonal, relationship and STI related influences.

Table 2. Intrapersonal, Relationship, and STI-Related Influences on the Risk of Ending Different Length Abstinent Periods.

| Hazard Ratioa (Confidence Interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Shorter Periods | Intermediate Periods | Longer Periods |

| Age | 1.07 *** (1.05-1.09) | 1.08 * (1.01-1.15) | 1.24 * (1.05-1.45) |

| Daily Positive Mood | 1.03 *** (1.02-1.04) | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | 0.99 (0.92-1.07) |

| Daily Negative Mood | 0.98 *** (0.97-0.99) | 0.95 ** (0.92-0.99) | 1.03 (0.93-1.13) |

| Daily Sexual Interest | 1.14 *** (1.11-1.17) | 1.16 *** (1.07-1.25) | 1.33 * (1.07-1.67) |

| Daily Partner Support | 1.14 *** (1.12-1.17) | 1.12 *** (1.05-1.18) | 1.14 (0.96-1.34) |

| Quarterly Relationship Quality | 1.02 *** (1.01-1.03) | 1.05 ** (1.02-1.08) | 1.10 * (1.01-1.19) |

| Quarterly Recent STI | 0.91 * (0.83-1.00) | 1.40 * (1.06-1.85) | 0.93 (0.43-2.00) |

| Quarterly Distant STI | 1.16 * (1.03-1.29) | 1.18 (0.90-1.54) | 1.30 (0.67-2.52) |

p<.001,

p<.01,

p<.05

Hazard Ratios were determined from univariate frailty models. Each hazard ratio is from a different model.

Shorter abstinence periods

The risk of ending a shorter abstinence period with sex was associated with all intrapersonal, relational and STI-related factors in the model (see column 1, Table 1). Each year increase in age increased the risk of ending a shorter period by 7% (p<.001). One unit increase in daily positive mood increased the risk by 3% (p<.001); while one unit increase in daily negative mood decreased the risk of sex by 2% (p<.001). One unit increase in daily sexual interest increased the risk of sex by 14% (p<.001). One unit increase in daily partner support increased the risk of sex by 14% (p<.001), and one unit increase in quarterly relationship quality increased the risk of sex 2% (p<.001). A recent STI diagnosis decreased the risk of sex ending a shorter abstinence period by 9% (p≤.05), and a distant STI increased the risk by 16%.

While the effect of positive mood, negative mood and relationship quality appear small, the hazard ratios presented are for one unit increase only. The mood scales ranged from 3-15, the relationship quality scale ranged from 6-24. For positive mood, an increase from the scale midpoint to the upper end is 6 units, translating into an increase in the risk of sex ending a shorter abstinence period by 18%; a similar increase in negative mood translates into a decrease in the risk by 12%. For relationship quality, an increase from the midpoint of the scale to the upper end is 9 points, translating into an increase in the risk by 18%.

Intermediate abstinence periods

Intermediate abstinence periods resembled shorter abstinence periods, showing associations with age, sexual interest, negative mood, relationship factors, and recent STI (See column 2, Table 1). However there were two important differences. First, positive mood was not associated with a significant change in the risk of sex ending an intermediate abstinence period. Second, in contrast to the decrease seen with shorter abstinence periods, a recent STI increased the risk of sex ending an intermediate abstinence period by 40% (p<.05).

Longer abstinent periods

Similar to shorter and intermediate periods, longer abstinent periods were associated with age (increased risk of 24% for each year of age, p<.05), daily sexual interest (increased risk of 33% for each unit increase in sexual interest, p<.05), and quarterly relationship quality (increased risk 10% for each unit increase in relationship quality, p<.05) (See column 3, Table 1). In contrast to shorter abstinent periods, none of the mood or STI measures were associated with the risk of sex ending a longer abstinent period.

Discussion

We found that factors associated with the decision to have sex after a period of abstinence differed based upon how long the adolescent had been abstinence. Beyond our overall results, three specific findings, in particular, extend our understanding of adolescent sexual behavior. First, an STI diagnosed at the visit just prior to the abstinence period was associated with a lower risk of sex for shorter length abstinence periods, but a higher risk for intermediate length periods. This switch is consistent with research showing that, after a period of abstinence in response to an STI diagnosis, many adolescents resume their relationship with that partner.9,18 We hypothesize that the switch may represent relationship turmoil after an STI, followed by “making-up.” The literature on adolescent sexual decision-making suggests two potential mediators of this finding: changes in perceived risk of STI in the period immediately following an STI diagnosis,16, 21, 22 and changes in partner closeness and relationship quality.12, 21 Alternatively, this switch could represent adherence to CDC recommendations about abstinence for shorter periods, 23 until both partners have completed treatment, and then resumption of sex after treatment. From a clinical perspective, this result suggests that, in the context of an STI diagnosis, counseling for post-treatment abstinence may not be sufficient. Our data suggest anticipation of resumption of sexual activity is also warranted. Return visits for retesting, as suggested by CDC guidelines,23 could provide an opportunity for reinforcement of STI and pregnancy prevention messages that include abstinence as an option. From a program perspective, this switch suggests that fear-based STI prevention strategies may be misguided, and that, instead, STI prevention should focus on the relationship contexts of sexual decision-making.

Second, mood was associated with the decision to have sex only after shorter periods of abstinence, and this association was not observed for intermediate and longer periods of abstinence. A large body of literature demonstrates associations between depressed mood and sexual risk behaviors.24 However, recent studies using daily diaries and momentary sampling have demonstrated close temporal associations between improved mood and sexual thoughts and behaviors.12, 25, 26 Our work expands this understanding by demonstrating that these temporal associations between mood and sex are more important to decisions about sex after shorter periods of abstinence, but this mood does not appear to be as important to decision-making about sex after longer periods of abstinence. From a clinical perspective, the associations between intrapersonal factors, such as mood, and sexual behavior warrant attention when counseling individuals after short periods of abstinence.

Third, in contrast to our findings with mood, relationships and sexual interest showed associations with a higher likelihood of sex for shorter, intermediate, and longer abstinence periods. This is consistent with both qualitative and quantitative work demonstrating the importance of romantic relationships, relationship quality, and intimacy to sexually experienced adolescents.7, 27-29 Our findings bridge short-term studies demonstrating the importance of relationship quality in sexual decisions,12 and longer-term, longitudinal studies with similar findings.21 The importance of relationships in all three groups (shorter, intermediate, and longer abstinent periods) additionally challenges commonly held assumptions about adolescent sexual behavior. Adolescent sexual intercourse is frequently presented as an entirely opportunity driven risk behavior. Our data present a more nuanced picture, in which sexual intercourse is associated with important relationship attributes, such as partner support and perceptions of relationship quality. A developmental framework that identifies sexual intercourse as an expression of relationship closeness and commitment may be more appropriate.

This analysis has several limitations. First, the amount of censoring in intermediate and longer abstinence periods may limit our ability to detect small differences in those groups. Second, we only examined vaginal sex, rather than more inclusively considering anal and oral sex. This analytic decision was made because anal and oral sex carry different pregnancy and STI risks, and other analyses by our group suggest that influences on oral and anal sex differ. 30 Third, we defined abstinence periods purely in terms of behavior, although in practice the designation of abstinence often has value and contextual implications.7 Fourth, there are many different reasons for abstinence. In this analysis, we individually examine mood, sexual interest, relationships, and STIs. We also considered pregnancy. However, there are other partner-related, motivations and circumstantial factors that we did not address, such as relationship dissolution and partner change, parental supervision, or the use of hormonal contraception. Finally, our study was done with urban, African-American young women from a community with high rates of STI. Young women with different STI risk may have different “cut-points” for shorter versus longer abstinence periods, or different intrapersonal and relationship factors, and these will need to be identified.

Implications

Our findings have potential implications both for prevention programs and for clinical care of adolescents. Prevention programs may want to adapt their content to the typical pattern of sexual activity in their target population. Clinicians, in order to provide more targeted and timely sexual health counseling, may want to ask not only whether an adolescent is sexually active, but when they last had sex. If there has been a longer interval since last sex, the counseling can focus on relationships and “readiness” for sex. If it has been a shorter interval since last sex, counseling may additionally want to focus on immediate influences on decision-making, such as mood and sexual interest.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of these analyses were presented at Midwestern Society for Pediatric Research Annual Meeting, Indianapolis, IN, October 19, 2006, and the Society for Adolescent Medicine National Meeting, Denver, CO, March 30, 2007.

Funding/Support: This work was funded by NIH R01 HD 044387 and U19 AI031494-15 for the design and conduct of the study, data management, data analysis, and manuscript review. NIH 1 K23 HD 049444-01A2 funded data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

The instruments were revised mid-way through the study period, and an item explicitly asking about the use of abstinence as a way to avoid pregnancy was added at that point.

References

- 1.Loewenson PR, et al. Primary and secondary sexual abstinence in high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34(3):209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Administration for Children and Families. [May 21, 2007]; Grants Notice: Community-Based Abstinence Education Program, < http://www.acf.hhs.gov/grants/open/HHS-2007-ACF-ACYF-AE-0099.html>.

- 3.Ott MA, et al. Counseling adolescents about abstinence in the office setting. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2007;20(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santelli J, et al. Abstinence and abstinence-only education: a review of U.S. policies and programs. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(1):72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders SA, Reinisch JM. Would you say you “had sex” if…? Jama. 1999;281(3):275–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuster MA, et al. The sexual practices of adolescent virgins: genital sexual activities of high school students who have never had vaginal intercourse. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(11):1570–1576. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ott MA, et al. Perceptions of sexual abstinence among high-risk early and middle adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(2):192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindberg LD, et al. Changes in formal sex education: 1995-2002. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38(4):182–189. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.182.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortenberry JD, et al. Post-treatment sexual and prevention behaviours of adolescents with sexually transmitted infections. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78(5):365–368. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.5.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eaton DK, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2007. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2008;57(4):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abma JC, et al. Teenagers in the United States: sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, 2002. Vital and Health Statistics. 2004;23(24):1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fortenberry JD, et al. Daily mood, partner support, sexual interest, and sexual activity among adolescent women. Health Psychology. 2005;24(3):252–257. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Sullivan LF, Brooks-Gunn J. The timing of changes in girls' sexual cognitions and behaviors in early adolescence: a prospective, cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37(3):211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aalsma MC, et al. Family and friend closeness to adolescent sexual partners in relationship to condom use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(3):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rostosky SS, et al. Sexual behaviors and relationship qualities in late adolescent couples. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23(5):583–597. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ott MA, et al. The trade-off between hormonal contraceptives and condoms among adolescents. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2002;34(1):6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiner B. Attribution, emotion, and action. In: Sorrentino RM, Higgins ET, editors. Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1986. pp. 281–312. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz BP, et al. Sexual behavior among adolescent women at high risk for sexually transmitted infections. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2001;28(5):247–251. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ott MA, et al. The Influence of Hormonal Contraception on Mood and Sexual Interest among Adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(4):605–613. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9302-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data : Extending the Cox Model. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosengard C, et al. Perceived STD risk, relationship, and health values in adolescents' delaying sexual intercourse with new partners. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80(2):130–137. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.006056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford CA, et al. Perceived risk of chlamydial and gonococcal infection among sexually experienced young adults in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004 Nov-Dec;36(6):258–264. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.258.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recommendations and Reports. 2006;55(RR-11):1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown LK, et al. Depressive symptoms as a predictor of sexual risk among African American adolescents and young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(3):444, e441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shrier LA, et al. Affect and sexual behavior in adolescents: a review of the literature and comparison of momentary sampling with diary and retrospective self-report methods of measurement. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):e573–581. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shrier LA, et al. A momentary sampling study of the affective experience following coital events in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(4):357, e351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ott MA, et al. Greater expectations: Adolescents' positive motivations for sex differ by gender and sexual experience. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38(2):84–89. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.084.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cantor N, Sanderson CA. The functional regulation of adolescent dating relationships and sexual behavior: An interaction of goals, strategies, and situations. In: Heckhausen J, Dweck CS, editors. Motivation and self-regulation across the life span. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 185–215. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gebhardt WA, et al. Need for intimacy in relationships and motives for sex as determinants of adolescent condom use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33(3):154–164. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hensel DJ, et al. Variations in coital and noncoital sexual repertoire among adolescent women. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(2):170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]