Abstract

A novel magnetic bead-based protein kinase assay was developed using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) and immuno-chemifluorescence as two independent detection techniques. Abltide substrate was immobilized onto magnetic beads via non-covalent biotin-streptavidin interactions. This non-covalent immobilization strategy facilitated peptide release and allowed MALDI-TOF MS analysis of substrate phosphorylation. The use of magnetic beads provided rapid sample handling and allowed secondary analysis by immuno-chemifluorescence to determine the degree of substrate phosphorylation. This dual detection technique was used to evaluate the inhibition of c-Abl kinase by imatinib and dasatinib. For each inhibitor, IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) values determined by these two different detection methods were consistent and close to values reported in the literature. The high-throughput potential of this new approach to kinase assays was preliminarily demonstrated by screening a chemical library consisting of 31 compounds against c-Abl kinase using a 96-well plate. In this proof-of-principle experiment, both MALDI-TOF MS and immuno-chemifluorescence were able to compare inhibitor potencies with consistent values. Dual detection may significantly enhance the reliability of chemical library screening and identify false positives and negatives. Formatted for 96-well plates and with high-throughput potential, this dual detection kinase assay may provide a rapid, reliable and inexpensive route to the discovery of small molecule drug leads.

Keywords: Kinase assays, MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, Magnetic beads, Immuno-chemifluorescence, Protein phosphorylation, Inhibitors

Introduction

Protein phosphorylation is considered a critical post-translational modification [1], regulating processes such as signal transduction, apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism in all living cells [2,3]. The deregulation of protein phosphorylation is directly responsible for the pathogenesis of several inherited and acquired human diseases, ranging from cancer to immune disorders [4-6]. The selective inhibition of protein kinases is an effective approach for the treatment of a wide range of human cancers [7-10]. The clinical success of imatinib in the targeted treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), by the direct inhibition of Bcr-Abl, stimulated interest in the development of more potent inhibitors [11-13]. Toward this end, a variety of kinase assay techniques are being developed for the discovery and efficient evaluation of novel small-molecule inhibitors [14-30].

Peptides are widely used as substrates for kinase assays because they are easy to synthesize, characterize, and manipulate compared to protein substrates. The detection of phosphorylated amino acids on peptide substrates can be accomplished via antibody-based recognition and labeling or label-free methods such as mass spectrometry (MS) [30-33]. In a typical antibody-based ELISA kinase assay, a peptide substrate is immobilized and reacted with a kinase. The phosphorylated substrate is probed with a phospho-specific antibody and enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody with readout by chemiluminescence or chemifluorescence. This method is sensitive, straightforward and routinely used in laboratory and clinical settings. On the other hand, mass spectrometry detects the peptide mass before and after phosphorylation. The difference in mass before and after reaction with a kinase is calculated and matched with the expected addition of an HPO3 ion. While immuno-chemifluorescence depends on the availability of a phosphorylated amino acid and/or sequence-specific antibody, mass spectrometry provides a non-biased analysis of reaction products.

Peptide substrates were immobilized on magnetic beads to facilitate rapid handling and product isolation. Magnetic beads have been used extensively in many fields of biochemistry, molecular biology, and medicine [34]. They are well-suited to automated procedures because robotics are available to rapidly distribute and separate the particles in 96-well plates [35]. Magnetic beads have already been used to enrich endogenous phosphopeptides from cell lysates in preparation for MS analysis [36,37]. Herein, we designed and developed a novel magnetic bead-based kinase assay (Figure 1) in which a synthetic peptide substrate is immobilized on magnetic beads via a non-covalent streptavidin-biotin interaction. Phosphorylated peptides are analyzed by on-bead immuno-chemifluorescence using a primary antibody against phosphorylated tyrosine and a secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody. The fluorescence intensity is used to estimate the degree of substrate phosphorylation. Separately, peptide substrates are released from the beads and analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS to estimate the degree of substrate phosphorylation by relative ionization intensity. Although each detection technique presents separate advantages in sensitivity and accuracy, data from this dual detection system yield results that are validated with higher confidence than with either technique used alone.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of a magnetic bead-based kinase assay with two independent detection techniques. Label-free MALDI-TOF MS was used to detect the change in peptide molecular mass from incorporated phosphate. Separately immuno-chemifluorescence was used to detect fluorescence from the oxidation of HRP enzyme substrates. 1° Ab and 2° Ab represent primary and secondary antibodies respectively.

Materials and methods

Materials

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (≥99.5%, ultra for molecular biology, Fluka), Ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA) (≥97%, Sigma-Aldrich), Dithiothreitol (DTT) (99%, Alfa Aesar), Amplex® Red reagent (Molecular Probes™, Invitrogen), Anti-phosphotyrosine (4G10®) HRP conjugate (Millipore), Hydrogen peroxide, 30 wt.% solution in water (Sigma-Aldrich), HRP conjugated sheep anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA), BupH™ phosphate buffered saline packs (Thermo Scientific, Pierce Protein Research Products), Maleimide-PEG11-biotin (MAL-dPEG11 ™-biotin, Quanta Biodesign, Ltd.), Streptavidin MagneSphere® paramagnetic particles (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), Bovine serum albumin (BSA) (United States Biological, Swampscott, MA, USA), recombinant c-Abl (Upstate, Charlottesville, VA, USA), 96-well magnetic-ring stand (Ambion Inc.) were used as received. Abltide with an amino-terminal cysteine (CGGGGSGGGKGEAIYAAPFAKKKG) was prepared according to the procedure reported previously [25].

Kinase Inhibitors

Imatinib mesylate (Novartis) was provided by Wendy Stock (The University of Chicago). Dasatinib (free base) was purchased from LC Laboratories® (Woburn, MA, USA). A chemical library consisting of 31 ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors were synthesized using methods developed by Klutchko [38] and Boschelli [39]. Each compound was provided at 10 mM in DMSO and further diluted into three different concentrations (500 nM, 5μM, 50 μM) with DMSO.

Immobilization of Abltide onto Magnetic Beads

Magnetic beads at their original concentration (1 mg/ml) were washed with BupH™ PBS buffer. A magnetic stand (DynaMag™-2 Magnet, Invitrogen) was used to collect the beads against the side of a tube, and supernatant was removed by pipette. 10 mM of Abltide (CGGGGSGGGKGEAIYAAPFAKKKG) in BupH™ PBS buffer and 40 mM of Maleimide-PEG11-biotin in DMF were mixed (4:1, v/v). The reaction mixture was centrifuged for 1 h to prevent dimerization of peptide due to the sulfhydryl oxidation. The resulting biotinylated peptide solution was directly conjugated to magnetic beads without further purification. 5 μL of 8 mM biotinylated peptide in BupH™ PBS buffer-DMF mixture solution was added to washed magnetic beads and mixed at room temperature for 1 h. Peptide-conjugated magnetic beads were washed four times with 0.1% Tween 20 in BupH™ PBS buffer (all percentages mentioned in the text are % (v/v) unless otherwise specified) to reduce non-specific binding and washed with sterilized water four times to give 1.2 mL of peptide-conjugated magnetic beads in water. Abltide-conjugated magnetic beads were stored at 4 °C.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

Dasatinib and imatinib were assayed in vitro using recombinant c-Abl. Abltide-conjugated magnetic beads were blocked with 10% BSA (w/v) in kinase buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.50, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.01% Brij-35) for 2 h at 4 °C. A typical 50 μL-kinase reaction buffer contained 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 0.01% Brij-35, 1.2 mg/ml BSA, 50 μM ATP, 0.10 mg/ml BSA-blocked magnetic beads, 0.0068 U recombinant c-Abl as well as various concentrations of inhibitors. To determine IC50 values of imatinib and dasatinib, a series of kinase reactions with inhibitor concentrations of 0, 1, 10, 100, 200, 500, 103, 104, 105 nM for imatinib and 0, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 100, 1000 nM for dasatinib) were performed at 30 °C for 1 h. After kinase reactions, magnetic beads were separated and washed twice. Kinase-treated beads were stored in 50 μL water at 4 °C.

Immuno-chemifluorescence Analysis

20 μL of beads were washed and blocked with 1% (w/v) BSA in TBS-T buffer at room temperature for 1 h. After blocking, kinase-treated magnetic beads were washed with TBS-T twice, and incubated in a 1:1000 dilution of primary antibody 4G10 in TBS-T at room temperature for 1 h. Beads were washed twice with TBS-T and incubated with a 1:2000 dilution of secondary antibody in TBS-T at room temperature for 30 min. Kinase-treated magnetic beads were washed twice with TBS-T buffer and followed addition of 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5). 50 μL of freshly prepared 50 μM Amplex® Red reagent and 1 mM H2O2 in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) were added to each well. The intensity of the generated fluorescence was detected using a Quad-4-monochromator microplate reader (Tecan Safire 2) with an excitation wavelength of 532 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm.

MALDI-TOF MS Analysis

30 μL of kinase-treated magnetic beads were collected and resuspended in 3 μL of water. 0.5 μL was spotted onto a MALDI sample plate and dried under vacumm. The same volume of a matrix solution, composed of 10 mg/ml of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 50% acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA, was spotted onto the surface of each sample and allowed to dry. The MALDI sample plate was loaded into a Voyager-DE Biospectrometry mass spectrometer. The MALDI-TOF MS analysis was operated in delayed extraction mode using a 3-ns pulse nitrogen laser (337 nm) for desorption and ionization and an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. Positively charged ions were detected using time-of-flight in linear mode. Commercial peptides, Des-Arg Bradykinin ([M+H]+ 904) and Neurotensin ([M+H]+ 1673) were used as external standards for accurate mass calibration. The degree of phosphorylation of Abltide immobilized on magnetic beads, expressed by phosphorylation ratio, is defined as the ratio of ion intensities for the phosphorylated to unphosphorylated biotinylated Abltide substrates and calculated by the following equation reported previously by Katayama et. al [40,41].

where Ep is the phosphorylation ratio of peptide substrate, IP-bP and IUP-bP are the intensities of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated biotinylated peptide peaks in a single MALDI spectrum.

Chemical Screening

A chemical library consisting of 31 compounds was screened against c-Abl kinase activity. For each inhibitor, three working concentrations of 500 nM, 5 μM and 50 μM were prepared by diluting 10 mM with DMSO. 50 μL kinase inhibition assays were performed in clear 96-well V-bottom microplates (Greiner, NC, USA). Reactions contained a buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 0.01% Brij-35, 1.2 mg/ml BSA, 50 μM ATP as well as 5 μL of BSA-blocked magnetic beads bearing peptide substrates, 0.068 U of purified recombinant c-Abl and 1 μL of working inhibitor solution. Control samples were treated with 1 μL of DMSO, corresponding to 2% final concentration in all samples. Following incubation at 30 °C for 1 h, beads were magnetically isolated and washed twice with sterilized water to remove salts. Beads were then analyzed by both the MALDI and immuno-chemifluorescence techniques as described. The amount of substrate phosphorylation was calculated by the intensity of two MALDI peaks corresponding to phosphorylated and un-phosphorylated peptides. The fluorescence intensity in each well was monitored by the Tecan Safire 2 microplate reader, with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 532 nm and 590 nm respectively. The fluorescence intensity indirectly reflects the degree of phosphorylation in each sample.

Results and discussion

Our goal was to describe a dual detection kinase assay method and test it by comparing the efficacy of small-molecule inhibitors against c-Abl kinase. Toward this end, a peptide substrate specific to c-Abl was immobilized on magnetic beads to allow the rapid separation of product from reagents prior to detection. The peptide substrate, Abltide (CGGGGSGGGKEAIYAAPFAKKKG), based on an optimized recognition sequence [42], included a series of non-reactive glycine residues to provide distance between the amino-terminal site of immobilization and the single tyrosine to be phosphorylated. Abltide was biotinylated at the amino-terminal cysteine using maleimide-PEG11-biotin, a sulfhydryl-reactive biotin reagent with a polyethylene glycol (PEG) spacer [43]. Immediately following biotinylation and without further purification, Abltide was immobilized on streptavidin-coated beads. After immobilization, peptide-conjugated magnetic beads were washed and further analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. Minor peaks representing non-specifically bound un-biotinylated peptide (P) were detected along with the main peak corresponding to biotinylated peptide (bP) (Figure 2A). This non-specific substrate binding was reduced by washing with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS buffer. Peptide-conjugated magnetic beads had an estimated loading capacity of 4 nmoles of biotinylated Abltide substrates per mL of beads by MALDI-TOF MS, which was close to the estimate of 7.0 nmole per mL of beads provided by a standard bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Estimation of bead loading capacity in Supporting Information). Only 2 – 3.5 pmoles of immobilized biotinylated peptide were necessary for detection by MALDI-TOF MS with a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of 1350. This further confirmed that peptide substrates can be successfully immobilized and released from magnetic beads through the non-covalent streptavidin-biotin interaction. MALDI-TOF MS is able to detect biotinylated Abltide without the need for specific labeling treatments.

Figure 2.

A representative set of MALDI-TOF MS spectra showing Abltide released from magnetic beads before (A) and after (B) phosphorylation by c-Abl kinase. Singly and doubly-charged molecular ion peaks of biotinylated Abltide substrates (bP) were observed at m/z = 3088.66 and 1545.64 respectively, very close to their theoretical values of m/z = 3088.57 ([MbP+H]+) and 1544.79 ([MbP+2H]2+) before phosphorylation (Figure A), and m/z = 3088.66 and 1545.43 after phosphorylation (Figure B). The peak at m/z = 3105.05 represents oxidized products. Un-biotinylated Abltide (P) was observed at m/z = 2167.47 (theoretical m/z =2167.11 ([MP+H]+)), bound non-specifically to streptavidin or the bead surface through hydrophobic or ionic interactions. Singly and doubly-charged molecular ion peaks of phosphorylated biotinylated Abltide were observed at m/z = 3168.56 and 1585.37 (Figure B) (theoretical m/z = 3168.54 ([MbP+HPO3]+) and 1584.78 ([MbP+H2PO3]2+)). Minor peaks at m/z = 2167.33 and 2247.18 were attributed to non-specifically bound un-phosphorylated and phosphorylated un-biotinylated Abltide, which can be removed by washing with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS buffer.

To test the accessibility of substrate and the sensitivity of our method, immobilized Abltide was phosphorylated by purified recombinant c-Abl. 5 μL of conjugated beads (1 mg/ml) containing approximately 20 – 35 pmoles of peptide substrate were used per 50 μL kinase reaction. By MALDI-TOF MS, three pairs of ions were observed per spectrum (Figure 2B), representing the phosphorylated and un-phosphorylated forms of 1) singly-charged biotinylated Abltide, 2) doubly-charged biotinylated Abltide, and 3) singly-charged un-biotinylated Abltide. Despite this distribution, the relative intensity of phosphorylated product was consistent in each set of peaks. Therefore, the relative degree of substrate phosphorylation was calculated as a percentage from ratio of peak intensities from the singly-charged phosphorylated and un-phosphorylated pair. The advantage of using MALDI-TOF MS to detect substrate phosphorylation is the unambiguous assignment of product peaks with an 80 Da difference in mass following the incorporation of HPO3 [44]. This property is characteristic of phophotyrosine (p-Tyr) residues analyzed by MS. On the other hand, phosphoserine (P-Ser) and phosphothreonine (P-Thr) residues generate a characteristic shift in mass by 97 Daltons as a result of losing H3PO4 by β-elimination [33].

Although MALDI-TOF MS is not inherently quantitative, the relative intensity of the phosphorylated and un-phosphorylated substrate ion peaks can be used to determine the relative degree of substrate phosphorylation [41,45]. By this method, 40% of immobilized Abltide was phosphorylated in 1 h using 0.0068 U of c-Abl kinase with 50 μM ATP at 30 °C. This relatively low degree of phosphorylation may be attributed to limited accessibility of the peptide substrate at the bead surface. In particular, streptavidin on the bead surface may occlude the bound peptide substrate from easy access to kinases in solution. In general, solid-phase kinase assays have been characterized as less efficient that solution-phase kinase reactions [46]. Post-reaction capture of phosphorylated substrates, after solution-phase kinase reactions, has been used as an alternative to solid-phase kinase assays. Although post-reaction substrate capture provides both high reaction rates and substrate isolation prior to analysis, the technique was not used for this initial characterization of the method [20]. Future applications may benefit from the phosphorylation of biotinylated substrates in solution followed by capture on streptavidin-coated magnetic beads.

Kinase-treated and untreated magnetic beads bearing peptide substrates were also analyzed by immuno-chemifluorescence. This method used HRP enzyme to catalyze the oxidization of Amplex® red substrate and generate a fluorescent resorufin product. The distinct difference in fluorescence intensity (ca. 40,000 vs. 1,000) between kinase-treated and untreated peptide-conjugated magnetic beads demonstrated that phosphorylated peptides on magnetic beads can be detected with high sensitivity by immuno-chemifluorescence. Thousand-fold signal-to-noise ratios were obtained by both immuno-chemfluorescence and MALDI-TOF MS. The specificity of MALDI-TOF MS for the unambiguous identification of product and the amplified signal sensitivity available through chemifluorescent immuno-detection provide parallel platforms for the separate validation of kinase activity and inhibition.

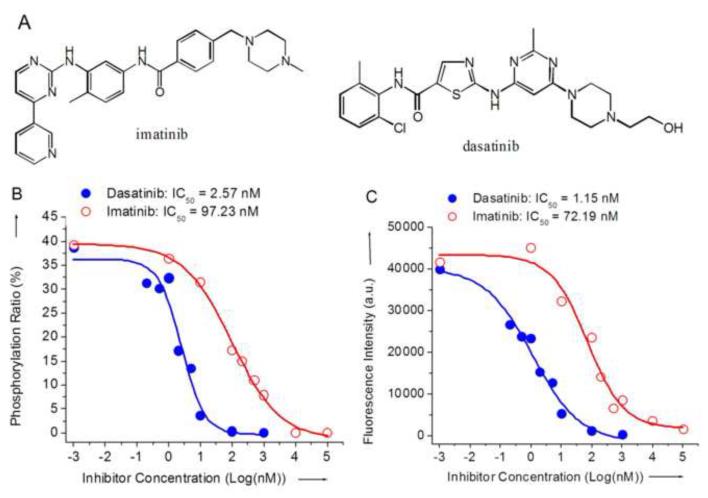

Two clinically relevant Bcr-Abl/c-Abl kinase inhibitors, imatinib [11] and dasatinib [47] (structures, see Figure 3A), were used to demonstrate kinase-specific phosphorylation of Abltide. Phosphorylated Abltide peaks decreased in intensity with increasing concentrations of imatinib (Figure S2 in Supporting Information) and dasatinib. The dose-dependent decrease in Abltide phosphorylation was monitored by MALDI-TOF MS and chemifluorescent immuno-detection to demonstrate that both methods generated similar results (Figures 3B and 3C). IC50 values were calculated from a sigmoidal curve fit. Values were consistent (Figure 3) with previously published results (typical IC50 values are reported using c-Abl and peptide substrates at 25-440 nM [11,48-53] for imatinib and 0.6-14 nM [51-55] for dasatinib). Validated by two separate detection methods, the phosphorylation of immobilized peptide substrates provided an efficient reporter for kinase activity and inhibition in this magnetic bead-based kinase assay.

Figure 3.

(A) Chemical structures of imatinib and dasatinib. (B, C) Inhibition assays using imatinib and dasatinib against c-Abl kinase and its substrate Abltide. The degree of phosphorylation was determined by two separate techniques. (B) Detected by MALDI-TOF MS, the phosphorylation ratio was calculated from the ratio of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated peak intensities, each data point is the average based on triplicate spectra. (C) Detected by immuno-chemifluorescence, Amplex® Red fluorescence intensity was measured at 590 nm with an excitation wavelength of 532 nm.

To demonstrate the potential for high throughput, a chemical library consisting of 31 compounds (Table S1 in Supporting Information) was screened against c-Abl kinase. Arranged in a 96-well plate, each inhibitor was tested at three concentrations: 10 nM, 100 nM, and 1000 nM. Control samples were treated with DMSO alone. Following the kinase reaction, peptide-conjugated magnetic beads were washed in-plate by magnetic separation and analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS and immuno-chemifluorescence (Figure 4A and 4B). With a variety of chemical structures constructed from the pyrido-[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffold, these experimental inhibitors demonstrate the effect of changing substituent chemical groups. Twelve different inhibitors in the chemical library (Inhibitors 1-4, 6, 7, 9-13, 22 in Figure 4 and Table S1) were previously screened with cells expressing wild-type and mutant Bcr-Abl [56]. Our results indicate that these compounds inhibited Bcr-Abl kinase activity with higher potency than imatinib (Inhibitor 28). Two of the most active compounds were PD166326 and DV-M016. DV2-103 (Inhibitor 14) is an inactive pyridopyrimidine and displayed no inhibitory effects even at 1000 nM.

Figure 4.

Screening compounds for c-Abl kinase inhibition in a 96-well plate using MALDI-TOF MS (A) and immuno-chemifluorescence (B). Some compounds were known c-Abl kinase inhibitors. Inhibitor 14 is an inactive control pyridopyrimidine that did not affect kinase activity, even at 1000 nM. Inhibitors 21-25 were found to be less effective than other inhibitors. Known kinase inhibitors PD166326 (Inhibitor 1) and dasatinib (Inhibitor 31) were shown to be potent against c-Abl kinase. Inhibitor 28 (imatinib) was shown to be less effective than dasatinib.

Our observations using both MALDI-TOF MS and immuno-chemifluorescence are consistent with results from an in vitro enzyme-coupled assay that was used to screen these inhibitors. Confirming our results, previous experiments using a two-dimensional presentation of Abltide in a hydrogel-based kinase assay demonstrated that Inhibitors 21-25 were less effective than PD166326 (Inhibitor 1) [25]. Similarly, known kinase inhibitors, PD166326 (Inhibitor 1) and dasatinib (Inhibitor 31), have been confirmed to be more potent for c-Abl kinase inhibition than imatinib (Inhibitor 28). Previously reported IC50 values for several inhibitors are available (Table S1) and reflect the degree of kinase inhibition that we observed. Taken together, these methods provide an effective means for ranking inhibitors with high confidence within a large compound library. Both MALDI-TOF MS and immuno-chemifluorescence are able to distinguish between inhibitor efficacies using only 3 data points per method per inhibitor.

Conclusions

Using a model system consisting of the Abltide peptide substrate and c-Abl kinase, a library of kinase inhibitors were evaluated using our magnetic bead-based kinase assay. For each inhibitor, IC50 values were consistent between the two detection methods and were comparable to values reported in the literature. Using a chemical library of 31 compounds, we demonstrated that both MALDI-TOF MS and immuno-chemifluorescence generated consistent results. With respect to general expense and opportunities for miniaturization, our dual-detection technique used 10 nmol of peptide substrate to produce enough magnetic beads bearing peptide substrates for 200 individual kinase reactions. For each batch of beads produced, 5 μl of magnetic beads at the stock concentration of 1 mg/ml was sufficient for one kinase reaction. Only 1 μl each of kinase-treated magnetic beads was required for MALDI-TOF MS and immuno-chemifluorescence detection of substrate phosphorylation, resulting in a cost of less than $1 per data point. Easily adapted to 96-well plates and with high-throughput capability, this dual detection kinase assay may improve the dependability of rapid drug screening by avoiding the false positives and negatives that often dominate pharmaceutical hit-lists.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wendy Stock for kindly providing imatinib. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HG003864, GM074691, and CA126764.

Abbreviations used

- MALDI-TOF MS

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- MS

mass spectrometry

- CML

chronic myelogenous leukemia

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- EGTA

ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid

- DMF

N,N-Dimethylformamide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

Footnotes

Subject category: Protein kinase assays

Appendix A. Supplementary data Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Pawson T, Scott JD. Signaling through scaffold, anchoring, and adaptor proteins. Science. 1997;278:2075–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hunter T. Signaling - 2000 and beyond. Cell. 2000;100:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hunter T. Protein-kinases and phosphatases - the yin and yang of protein-phosphorylation and signaling. Cell. 1995;80:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Demichelis F, Setlur SR, Beroukhim R, Perner S, Korbel JO, LaFargue CJ, Pflueger D, Pina C, Hofer MD, Sboner A, Svensson MA, Rickman DS, Urban A, Snyder M, Meyerson M, Lee C, Gerstein MB, Kuefer R, Rubin MA. Distinct genomic aberrations associated with ERG rearranged prostate cancer. Gene Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:366–380. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Alonso A, Sasin J, Bottini N, Friedberg I, Osterman A, Godzik A, Hunter T, Dixon J, Mustelin T. Protein tyrosine phosphatases in the human genome. Cell. 2004;117:699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 2001;411:355–365. doi: 10.1038/35077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhang JM, Yang PL, Gray NS. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gibbs JB. Mechanism-based target identification and drug discovery in cancer research. Science. 2000;287:1969–1973. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Varmus H. The new era in cancer research. Science. 2006;312:1162–1165. doi: 10.1126/science.1126758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Thompson CB. Attacking cancer at its root. Cell. 2009;138:1051–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Druker BJ, Tamura S, Buchdunger E, Ohno S, Segal GM, Fanning S, Zimmermann J, Lydon NB. Effects of a selective inhibitor of the Abl tyrosine kinase on the growth of Bcr-Abl positive cells. Nat. Med. 1996;2:561–566. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Collins I, Workman P. New approaches to molecular cancer therapeutics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:689–700. doi: 10.1038/nchembio840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rix U, Superti-Furga G. Target profiling of small molecules by chemical proteomics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:616–624. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhu H, Bilgin M, Bangham R, Hall D, Casamayor A, Bertone P, Lan N, Jansen R, Bidlingmaier S, Houfek T, Mitchell T, Miller P, Dean RA, Gerstein M, Snyder M. Global analysis of protein activities using proteome chips. Science. 2001;293:2101–2105. doi: 10.1126/science.1062191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhu H, Snyder M. Protein arrays and microarrays. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2001;5:40–45. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Greis KD. Mass spectrometry for enzyme assays and inhibitor screening: An emerging application in pharmaceutical research. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2007;26:324–339. doi: 10.1002/mas.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Inamori K, Kyo M, Nishiya Y, Inoue Y, Sonoda T, Kinoshita E, Koike T, Katayama Y. Detection and quantification of on-chip phosphorylated peptides by surface plasmon resonance imaging techniques using a phosphate capture molecule. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:3979–3985. doi: 10.1021/ac050135t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mori T, Inamori K, Inoue Y, Han X, Yamanouchi G, Niidome T, Katayama Y. Evaluation of protein kinase activities of cell lysates using peptide microarrays based on surface plasmon resonance imaging. Anal. Biochem. 2008;375:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Han X, Shigaki S, Yamaji T, Yarnanouchi G, Mori T, Niidome T, Katayama Y. A quantitative peptide array for evaluation of protein kinase activity. Anal. Biochem. 2008;372:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shults MD, Kozlov IA, Nelson N, Kermani BG, Melnyk PC, Shevchenko V, Srinivasan A, Musmacker J, Hachmann JP, Barker DL, Lebl M, Zhao CF. A multiplexed protein kinase assay. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:933–942. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bernsteel DJ, Roman DL, Neubig RR. In vitro protein kinase activity measurement by flow cytometry. Anal. Biochem. 2008;383:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Houseman BT, Huh JH, Kron SJ, Mrksich M. Peptide chips for the quantitative evaluation of protein kinase activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:270–274. doi: 10.1038/nbt0302-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kim YP, Oh E, Oh YH, Moon DW, Lee TG, Kim HS. Protein kinase assay on peptide-conjugated gold nanoparticles by using secondary-ion mass spectrometric imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:6816–6819. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Oishi J, Han X, Kang JH, Asami Y, Mori T, Niidorne T, Katayarna Y. High-throughput colorimetric detection of tyrosine kinase inhibitors based on the aggregation of gold nanoparticles. Anal. Biochem. 2008;373:161–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wu D, Mand MR, Veach DR, Parker LL, Clarkson B, Kron SJ. A solid-phase Bcr-Abl kinase assay in 96-well hydrogel plates. Anal. Biochem. 2008;375:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wu D, Nair-Gill E, Sher DA, Parker LL, Campbell JM, Siddiqui M, Stock W, Kron SJ. Assaying Bcr-Abl kinase activity and inhibition in whole cell extracts by phosphorylation of substrates immobilized on agarose beads. Anal. Biochem. 2005;347:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Brueggemeier SB, Wu D, Kron SJ, Palecek SP. Protein-acrylamide copolymer hydrogels for array-based detection of tyrosine kinase activity from cell lysates. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:2765–2775. doi: 10.1021/bm050257v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Parker LL, Brueggemeier SB, Rhee WJ, Wu D, Kent SBH, Kron SJ, Palecek SP. Photocleavable peptide hydrogel arrays for MALDI-TOF analysis of kinase activity. Analyst. 2006;131:1097–1104. doi: 10.1039/b607180e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kinumi T, Niki E, Shigeri Y, Matsumoto H. Affinity-tagged phosphorylation assay by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ATPA-MALDI): Application to calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J. Biochem. 2005;138:791–796. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Akita S, Umezawa N, Kato N, Higuchi T. Array-based fluorescence assay for serine/threonine kinases using specific chemical reaction. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:7788–7794. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Greis KD, Zhou ST, Burt TM, Carr AN, Dolan E, Easwaran V, Evdokimov A, Kawamoto R, Roesgen J, Davis GF. MALDI-TOF MS as a label-free approach to rapid inhibitor screening. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rathore R, Corr J, Scott G, Vollmerhaus P, Greis KD. Development of an inhibitor screening platform via mass spectrometry. J. Biomol. Screen. 2008;13:1007–1013. doi: 10.1177/1087057108326143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].McLachlin DT, Chait BT. Analysis of phosphorylated proteins and peptides by mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2001;5:591–602. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lundeberg J, Pettersson B, Uhlen M. Direct DNA sequencing of polymerase chain reaction products using magnetic beads. Nucleic Acid Protocols Handbook. 2000:523–531. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ficarro SB, Adelmant G, Tomar MN, Zhang Y, Cheng VJ, Marto JA. Magnetic bead processor for rapid evaluation and optimization of parameters for phosphopeptide enrichment. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:4566–4575. doi: 10.1021/ac9004452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hsiao HH, Hsieh HY, Chou CC, Lin SY, Wang AHJ, Khoo KH. Concerted experimental approach for sequential mapping of peptides and phosphopeptides using c18-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:1313–1324. doi: 10.1021/pr0604817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li YC, Lin YS, Tsai PJ, Chen CT, Chen WY, Chen YC. Nitrilotriacetic acid-coated magnetic nanoparticles as affinity probes for enrichment of histidine-tagged proteins and phosphorylated peptides. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:7519–7525. doi: 10.1021/ac0711440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Klutchko SR, Hamby JM, Boschelli DH, Wu ZP, Kraker AJ, Amar AM, Hartl BG, Shen C, Klohs WD, Steinkampf RW, Driscoll DL, Nelson JM, Elliott WL, Roberts BJ, Stoner CL, Vincent PW, Dykes DJ, Panek RL, Lu GH, Major TC, Dahring TK, Hallak H, Bradford LA, Showalter HDH, Doherty AM. 2-substituted aminopyrido 2,3-d pyrimidin-7(8H) ones. Structure-activity relationships against selected tyrosine kinases and in vitro and in vivo anticancer activity. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:3276–3292. doi: 10.1021/jm9802259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Boschelli DH, Wu ZP, Klutchko SR, Showalter HDH, Hamby JM, Lu GH, Major TC, Dahring TK, Batley B, Panek RL, Keiser J, Hartl BG, Kraker AJ, Klohs WD, Roberts BJ, Patmore S, Elliott WL, Steinkampf R, Bradford LA, Hallak H, Doherty AM. Synthesis and tyrosine kinase inhibitory activity of a series of 2-amino-8H-pyrido 2,3-d pyrimidines: Identification of potent, selective platelet-derived growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:4365–4377. doi: 10.1021/jm980398y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kang JH, Katayama Y, Han AS, Shigaki S, Oishi J, Kawamura K, Toita R, Han XM, Mori T, Niidome T. Mass-tag technology responding to intracellular signals as a novel assay system for the diagnosis of tumor. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kang JH, Toita R, Oishi J, Niidome T, Katayama Y. Effect of the addition of diammonium citrate to alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) matrix for the detection of phosphorylated peptide in phosphorylation reactions using cell and tissue lysates. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:1925–1931. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zhou S, Carraway KL, Eck MJ, Harrison SC, Feldman RA, Mohammadi M, Schlessinger J, Hubbard SR, Smith DP, Eng C, Lorenzo MJ, Ponder BAJ, Mayer BJ, Cantley LC. Catalytic specificity of protein-tyrosine kinases is critical for selective signaling. Nature. 1995;373:536–539. doi: 10.1038/373536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Inamori K, Kyo M, Matsukawa K, Inoue Y, Sonoda T, Tatematsu K, Tanizawa K, Mori T, Katayama Y. Optimal surface chemistry for peptide immobilization in on-chip phosphorylation analysis. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:643–650. doi: 10.1021/ac701667g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Parker L, Engel-Hall A, Drew K, Steinhardt G, Helseth DL, Jabon D, McMurry T, Angulo DS, Kron SJ. Investigating quantitation of phosphorylation using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2008;43:518–527. doi: 10.1002/jms.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kang JH, Kuramoto M, Tsuchiya A, Toita R, Asai D, Sato YT, Mori T, Niidome T, Katayama Y. Correlation between phosphorylation ratios by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometric analysis and enzyme kinetics. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2008;14:261–265. doi: 10.1255/ejms.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wu D, Sylvester JE, Parker LL, Zhou G, Kron SJ. Peptide reporters of kinase activity in whole cell lysates. Biopolymers (Pept. Sci.) 2010;94:475–486. doi: 10.1002/bip.21401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Shah NP, Tran C, Lee FY, Chen P, Norris D, Sawyers CL. Overriding imatinib resistance with a novel ABL kinase inhibitor. Science. 2004;305:399–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1099480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Buchdunger E, Zimmermann J, Mett H, Meyer T, Muller M, Druker BJ, Lydon NB. Inhibition of the abl protein-tyrosine kinase in vitro and in vivo by a 2- phenylaminopyrimidine derivative. Cancer Res. 1996;56:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Huron DR, Gorre ME, Kraker AJ, Sawyers CL, Rosen N, Moasser MM. A novel pyridopyrimidine inhibitor of Abl kinase is a picomolar inhibitor of Bcr-Abl-driven K562 cells and is effective against STI571-resistant Bcr-Abl mutants. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:1267–1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Min DH, Su J, Mrksich M. Profiling kinase activities by using a peptide chip and mass spectrometry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:5973–5977. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bantscheff M, Eberhard D, Abraham Y, Bastuck S, Boesche M, Hobson S, Mathieson T, Perrin J, Raida M, Rau C, Reader V, Sweetman G, Bauer A, Bouwmeester T, Hopf C, Kruse U, Neubauer G, Ramsden N, Rick J, Kuster B, Drewes G. Quantitative chemical proteomics reveals mechanisms of action of clinical ABL kinase inhibitors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/nbt1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].O’Hare T, Walters DK, Stoffregen EP, Jia TP, Manley PW, Mestan J, Cowan-Jacob SW, Lee FY, Heinrich MC, Deininger MWN, Druker BJ. In vitro activity of Bcr-Abl inhibitors AMN107 and BMS-354825 against clinically relevant imatinib-resistant Abl kinase domain mutants. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4500–4505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Brasher BB, Van Etten RA. c-Ab1 has high intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity that is stimulated by mutation of the Src homology 3 domain and by autophosphorylation at two distinct regulatory tyrosines. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35631–35637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005401200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Rix U, Hantschel O, Duernberger G, Rix LLR, Planyavsky M, Fernbach NV, Kaupe I, Bennett KL, Valent P, Colinge J, Kocher T, Superti-Furga G. Chemical proteomic profiles of the BCR-ABL inhibitors imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib, reveal novel kinase and nonkinase targets. Blood. 2007;110:4055–4063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hantschel O, Rix U, Schmidt U, Burckstummer T, Kneidinger M, Schutze G, Colinge J, Bennett KL, Ellmeier WR, Valent P, Superti-Furga G. The Btk tyrosine kinase is a major target of the Bcr-Abi inhibitor dasatinib. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:13283–13288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702654104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].von Bubnoff N, Veach DR, Miller WT, Li WQ, Peschel C, Bornmann WG, Clarkson B, Duyster J. Inhibition of wild-type and mutant Bcr-Abl by pyrido-pyrimidine-type small molecule kinase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6395–6404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.