Summary

SHP2 phosphatase is a positive transducer of growth factor and cytokine signaling. SHP2 is also a bona fide oncogene; gain-of-function SHP2 mutations leading to increased phosphatase activity cause Noonan syndrome as well as multiple forms of leukemia and solid tumors. We report that tautomycetin (TTN), an immunosuppressor in organ transplantation, and its engineered analog TTN D-1 are potent SHP2 inhibitors. TTN and TTN D-1 block T cell receptor-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation and ERK activation as well as activating SHP2-induced hematopoietic progenitor hyperproliferation and monocytic differentiation. Crystal structure of the SHP2•TTN D-1 complex reveals that TTN D-1 occupies the SHP2 active site in a manner similar to that of a peptide substrate. Collectively, the data support the notion that SHP2 is a cellular target for TTN and provide a potential mechanism for the immunosuppressive activity of TTN. Moreover, the structure furnishes molecular insights upon which novel therapeutics targeting SHP2 can be developed based on the TTN scaffold.

INTRODUCTION

The Src homology-2 domain containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2 (SHP2) is a positive transducer of growth factor- and cytokine-mediated signaling pathways essential for cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis (Neel et al., 2003). The catalytic activity of SHP2 is required for full activation of the Ras–ERK1/2 cascade that is mediated through SHP2-catalyzed dephosphorylation of substrates that are negatively regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation (Neel et al., 2003; Tiganis and Bennett, 2007). Not surprisingly, SHP2 has been identified as a bona fide oncogene from the protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) superfamily; gain-of-function SHP2 mutations leading to increased PTP activity are known to cause the autosomal dominant disorder Noonan syndrome as well as multiple forms of leukemia and solid tumors (Tartaglia and Gelb, 2005; Chan et al., 2008). Accordingly, SHP2 represents an exciting target for multiple cancers. Unfortunately, obtaining SHP2 inhibitors with optimal potency and pharmacological properties has been difficult, due primarily to the highly conserved and positively charged nature of the active site pocket shared by all PTP family members.

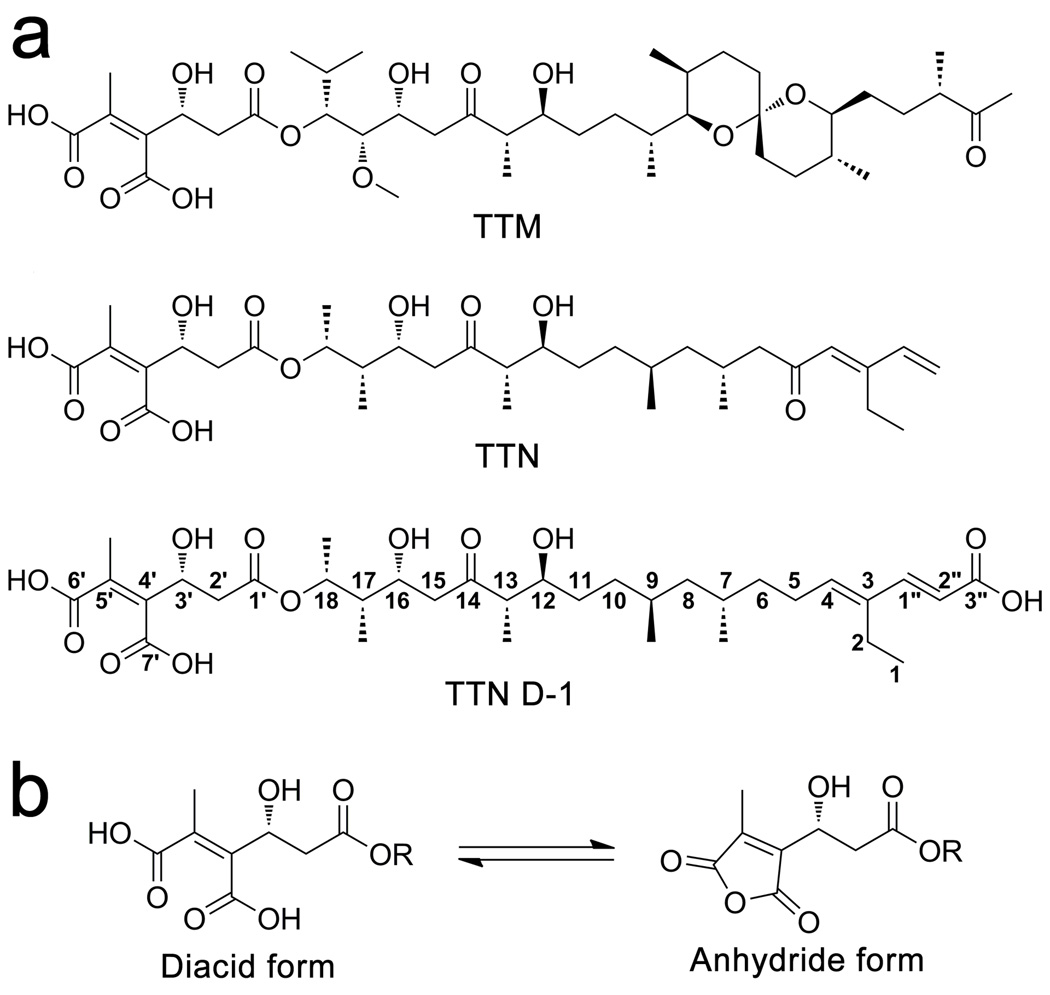

Tautomycin (TTM) and tautomycetin (TTN) are polyketide natural products originally isolated as antifungal antibiotics from Streptomyces spiroverticillatus and Streptomyces griseochromogens, respectively (Cheng et al., 1987; Cheng et al., 1989) (Figure 1). They are structurally similar, differing only in the presence of a spiroketal group on TTM, which is replaced by a dienone moiety in TTN. TTM and TTN were later found to possess inhibitory activity against serine/threonine protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) and 2A (PP2A) (MacKintosh and Klumpp, 1990; Mitsuhashi et al., 2001). Despite their similarities in structure and PP1/2A inhibitory activity, TTN, but not TTM, has been identified as a potent immunosuppressor of activated T cells in organ transplantation (Shim et al., 2002; Han et al., 2003). TTN exerts its immunosuppressive activity by blocking T-cell receptor (TCR) induced tyrosine phosphorylation, leading to inhibition of T cell proliferation and cell-specific apoptosis (Shim et al., 2002). Furthermore, TTN has also been suggested as a potential lead for anticancer drug discovery due to its growth inhibitory activity against colorectal cancer cells (Lee et al., 2006). Thus, TTN may serve as a promising lead for the development of new immunosuppressive and anti-tumor agents. To this end, identification of the cellular target(s) of TTN will significantly advance the progress toward TTN-based therapeutics. Strikingly, although TTM and TTN exhibit similar potency toward PP1/PP2A, TTM, unlike TTN, has no effect on tyrosine phosphorylation in T cells and does not elicit any immunosuppressive activity (Shim et al., 2002). Consequently, the immunosuppressive activity of TTN is unlikely related to its PP1/PP2A inhibitory activity and instead may be mediated by an effect on a novel target.

Figure 1.

Structures of (a) TTM, TTN, and the engineered analog TTN D-1 and (b) the diacid and anhydride forms. See also figure S1.

In an effort to identify novel SHP2 inhibitors and to search for TTN’s cellular target(s), we screened a natural product library of TTN, TTM, and nine engineered analogs featuring the TTN and TTM scaffolds (Figure S1 in Supporting Information) against SHP2 as well as a panel of PTPs. TTN and its engineered analog TTN D-1 (Figure 1), but not TTM, were found to inhibit the activity of SHP2. We showed that TTN and TTN D-1 block TCR-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation and ERK1/2 activation as well as activating SHP2-induced hematopoietic progenitor hyperproliferation and monocytic differentiation. Moreover, we determined the X-ray crystal structure of SHP2 with TTN D-1 bound to its active site. Together with the biochemical data, this structure supports the notion that SHP2 is a cellular target for TTN and provides molecular insights upon which novel therapeutics targeting SHP2 can be developed based on the TTN scaffold for multiple cancers and immunosuppression.

RESULTS

Identification of TTN as a SHP2 inhibitor

Given the observed effect of TTN on tyrosine phosphorylation, we explored whether TTN or its structurally related natural products could modulate the catalytic activity of the PTPs, a family of signaling enzymes that work together with protein tyrosine kinases to regulate the cellular level of protein tyrosine phosphorylation (Hunter, 2000; Tonks, 2006). We produced TTN and TTM, along with nine engineered analogs featuring the TTN and TTM scaffolds (Figure S1, Li et al., 2008; Ju et al., 2009; Li et al., 2009; Luo et al., 2010) and evaluated them as potential modulators of PTP activity. The effect of the compounds on PTP-catalyzed hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) was assessed at pH 7 and 25 °C. Members of the PTP superfamily that were included in the screen were the cytosolic PTPs, PTP1B, SHP1, SHP2, Lyp, HePTP, Meg2, and FAP1, the receptor-like PTPs, CD45, LAR, and PTPα, the dual specificity phosphatases VHR, VHX, and Cdc14, and the low molecular weight PTP. When assayed at 10 µM concentration, neither TTM nor its analogs exhibited any inhibitory activity against the panel of PTPs. Remarkably, TTN and one of its engineered analogs TTN D-1 (Figure 1) reduced SHP2 activity by 80–90% at 10 µM concentration. Importantly, TTN and TTN D-1 were highly specific for SHP2, exhibiting no significant activity (<30% inhibition at 10 µM concentration) toward the rest of the PTP panel.

To further characterize SHP2 inhibition by TTN and TTN D-1, the IC50 values for TTN and TTN D-1 were measured at a pNPP concentration fixed at the experimentally determined Km for each PTP. Therefore, all of the IC50 values reported in this study directly reflect the true affinity of the compound for the enzymes tested. As shown in Table 1, TTN inhibits SHP2 with an IC50 of 2.9 µM, while it is less effective toward other PTPs, with an IC50 value of 14.6 µM for SHP1, 20 µM for Lyp, 41.2 µM for PTP1B, and greater than 50 µM for HePTP, PTPα, CD45, VHR and Cdc14. Thus, TTN displays at least a 5-fold preference for SHP2 over all PTPs examined. Similar results were obtained for TTN D-1 (Table 1). To establish the mechanism of SHP2 inhibition by TTN and TTN D-1, the inhibition constants and mode of inhibition were determined. As shown in Figure S2, TTN and TTN D-1 act as competitive inhibitors of the SHP2-catalyzed reaction, with Ki values of 1.6 ± 0.1 µM and 2.3 ± 0.2 µM, respectively. This agrees well with the IC50 value determined at the substrate Km. Together, the results indicate that TTN and TTN D-1 are among the most potent and specific SHP2 inhibitors reported to date.

Table 1.

IC50 (µM) of TTN and TTN D-1 for a panel of PTPs

| PTP | TTN | TTN D-1 |

|---|---|---|

| SHP2 | 2.9±0.2 | 4.4±0.4 |

| SHP1 | 14.6±1.1 | 20.7±2.1 |

| PTP1B | 41.2±4.4 | 28.0±3 |

| Lyp | 20.0±2 | >50 |

| HePTP | >50 | >50 |

| PTPα | >50 | >50 |

| CD45 | >50 | >50 |

| VHR | >50 | >50 |

| Cdc14A | >50 | >50 |

All measurements were made using pNPP as a substrate at pH 7.0, 25 °C, and I=0.15 M. See also Figure S2.

TTN blocks SHP2 mediated signaling

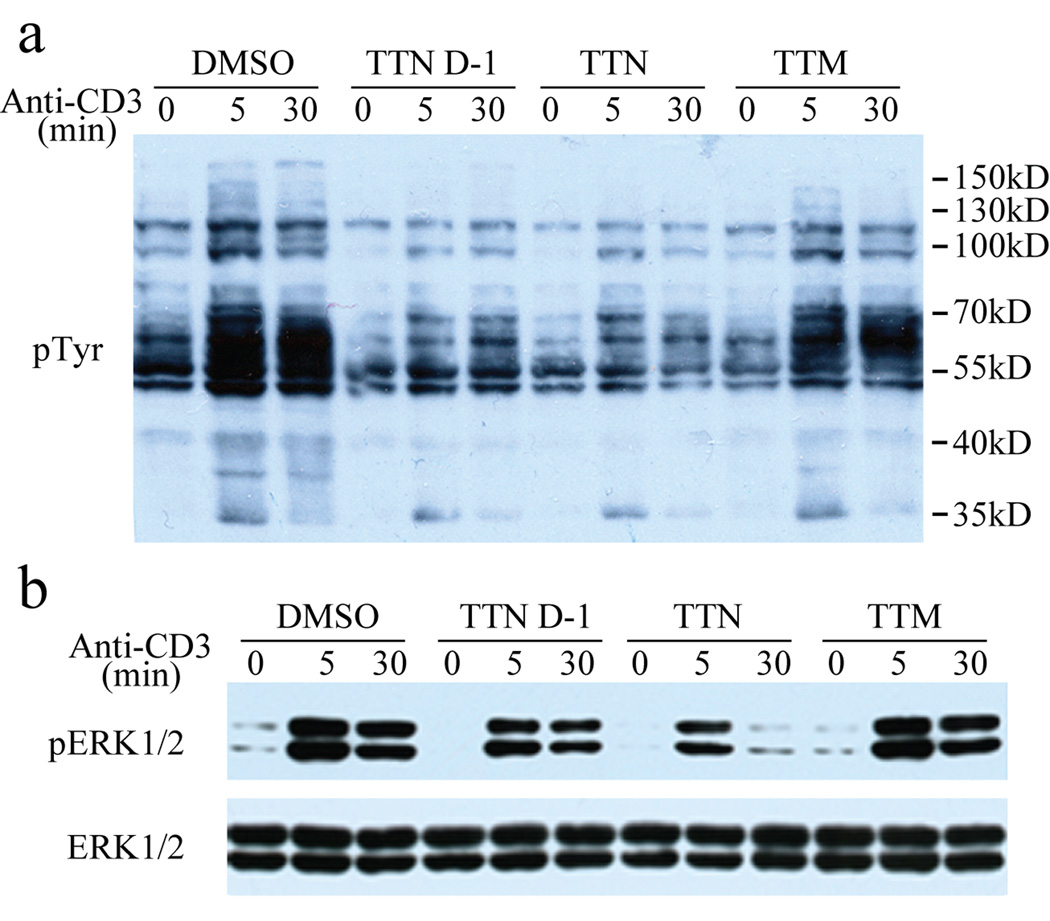

TTN induces immunosuppression by attenuation of TCR-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation and ERK1/2 activity in T cells (Shim et al., 2002). However, the mechanism of action for TTN’s ability to block TCR signaling remains undefined. We hypothesized that TTN may exert its immunosuppressive effect by inhibiting SHP2, as SHP2 is a positive mediator downstream of almost all growth factor and cytokine receptors and its phosphatase activity is required for activation of the Ras/ERK1/2 kinase pathway (Neel et al., 2003). Indeed, SHP2 deletion has been shown to cause decreased TCR signaling and impaired ERK1/2 activation in T cells (Nguyen et al., 2006). Given the observed potency and selectivity of TTN and TTN D-1 toward SHP2, we proceeded to evaluate their ability to inhibit SHP2-dependent signaling inside the cell. Previous studies showed that TTN inhibits human primary T-cell tyrosine phosphorylation at 1 µg/mL (1.65 µM) concentration (Shim et al., 2002), which is close to the measured Ki value of TTN for SHP2. We found that at similar concentrations (2–4 µM), TTN efficiently attenuated TCR-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation in Jurkat T cells (Figure 2a and Figure S3). Importantly, TTN D-1 also blocked TCR-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation whereas TTM, which does not inhibit SHP2 activity, had no effect on tyrosine phosphorylation in Jurkat cells. Additionally, TTN and TTN D-1 also strongly reduced the TCR-mediated ERK1/2 activation whereas TTM elicited no appreciable change in ERK1/2 phosphorylation level (Figure 2b and Figure S3). Moreover, II-B08, a structurally unrelated small molecule inhibitor of SHP2 (Zhang et al., 2010), is also capable of inhibiting anti-CD3-induced tyrosine phosphorylation and ERK1/2 activation in Jurket T cells (Figure S4), providing further evidence that the effect of TTN and TTN D-1 on TCR-mediated signaling was due at least in part to inhibition of SHP2.

Figure 2.

Effect of TTN and TTN D-1 on TCR-mediated signaling in Jurkat T cells. Cells were pretreated with 2 µM TTN, TTN D-1, or TTM for 2 hours and stimulated with 10 µg/mL anti-CD3 antibody. Cell lysates were immunoblotted by anti-pTyr for total tyrosine phosphorylation (a) and by anti-phospho-ERK1/2 and anti-ERK1/2 for activated ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 (b). See also Figure S3 and Figure S4.

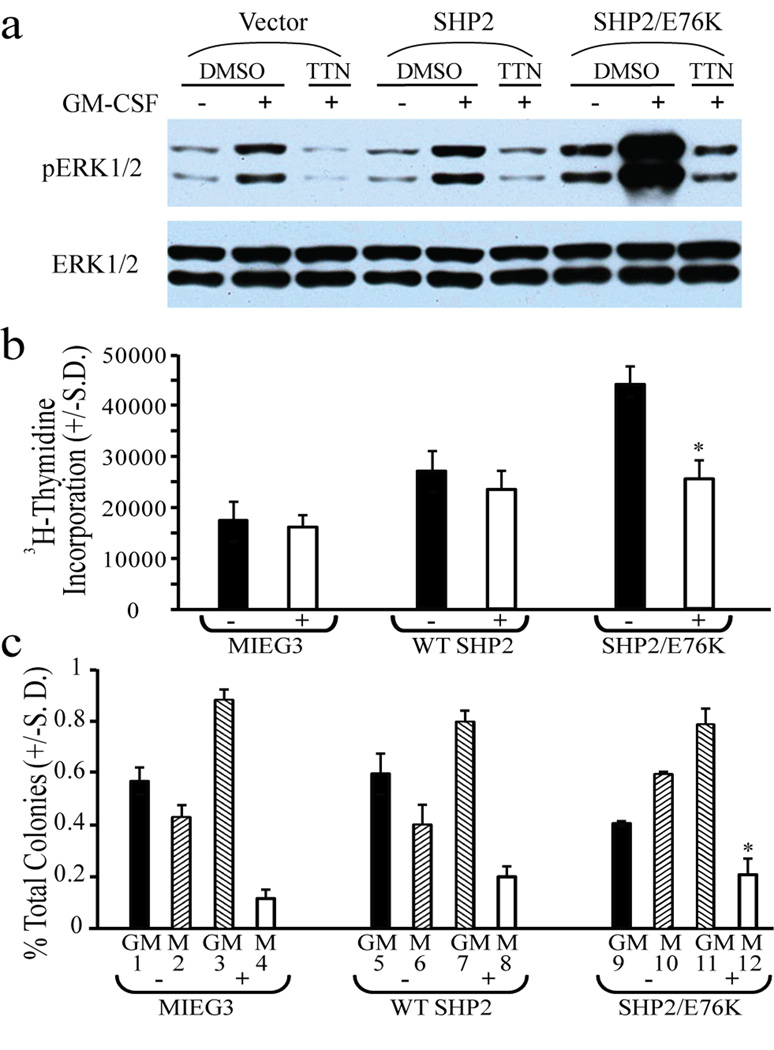

To further establish SHP2 as a cellular target for TTN, we also studied the effect of TTN on several other cellular processes mediated by SHP2. Germline SHP2 mutations are commonly found in the congenital disorder, Noonan syndrome, and somatic gain-of-function SHP2 mutations are frequently observed in the childhood leukemia, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML), as well as in childhood and adult acute myeloid leukemia and various solid tumors (Tartaglia and Gelb, 2005; Chan et al., 2008). Peripheral blood hematopoietic progenitors from JMML patients are hypersensitive to the cytokine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Emanuel et al., 1991). We showed previously that introduction of gain-of-function SHP2 mutations (SHP2/D61Y and SHP2/E76K) into hematopoietic progenitors induces hypersensitivity to GM-CSF (Chan et al., 2005), hyperactivation of GM-CSF-stimulated ERK1/2, and skewed monocytic differentiation (Chan et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2009). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that treatment of mutant SHP2-bearing hematopoietic progenitors with TTN would attenuate GM-CSF-stimulated hyperproliferation, ERK1/2 hyperactivation, and skewed monocytic differentiation.

For biochemical studies, macrophage progenitor cells expressing empty vector (MIEG3), wild-type SHP2, or SHP2/E76K were serum- and growth factor-deprived for 16 hours. Cells were pre-treated with DMSO or 2 µM TTN for 2 hours, and then cultures either remained unstimulated or were stimulated with GM-CSF at 50 ng/mL for 60 minutes. As predicted, TTN abrogated the GM-CSF induced ERK1/2 activation in macrophage progenitors as well as effectively inhibited the ERK1/2 hyperactivation in the SHP2/E76K-expressing cells (Figure 3a). We next examined the effect of TTN on GM-CSF-stimulated hyperproliferation of SHP2/E76K-expressing hematopoietic progenitors. Cells were serum- and growth factor-deprived for 6 hours and then cultured in complete medium with GM-CSF (1 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of 2 µM TTN for 24 hours and pulsed with [3H] thymidine to measure proliferation. As previously observed, in response to low GM-CSF stimulation, the SHP2/E76K-expressing progenitors hyperproliferated compared to the MIEG3- or WT SHP2-expressing progenitors (Chan et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2008), and TTN effectively reduced the proliferation of SHP2/E76K-expressing progenitors (Figure 3b). Under these conditions, the progenitors expressing SHP2/E76K appear to be more sensitive to TTN compared to those expressing MIEG3 or wild-type SHP2. Additionally, as previously observed (Yang et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2009), a significantly greater number of colony forming unit-macrophage (CFU-M) were generated from progenitors expressing SHP2/E76K, with a concomitant reduction in CFU-granulocyte/macrophage (CFU-GM) compared to progenitors transduced with MIEG3 or wild-type SHP2 (Figure 3c, compare #9/10 to #5/6 and #1/2). However, when plated in the presence of 2 µM TTN, the development of CFU-M was reduced in all cells types and, notably, the progenitor colony type distribution for the SHP2/E76K-expressing cells was similar to the MIEG3- and wild-type SHP2-expressing cells in the presence of TTN (Figure 3c, compare #11/12 to #7/8 and #3/4). Collectively, these findings indicate that i) TTN inhibits SHP2-dependent signaling, ii) inhibition of SHP2 phosphatase activity with TTN effectively reduces ERK1/2 activation, and iii) TTN is able to selectively reduce proliferation and normalize differentiation of mutant SHP2-expressing hematopoietic cells.

Figure 3.

Effect of TTN on SHP2-mediated processes in hematopoietic progenitors. (a) TTN abrogated the GM-CSF induced ERK1/2 activation in macrophage progenitors. Cells were serum- and growth factor-deprived for 16 hours, treated with 2 µM TTN for 2 hours, and stimulated with GM-CSF 50 ng/mL for 60 min followed by preparation of protein extracts. Extracts were evaluated by immunoblot using α-phospho-ERK1/2 for activated ERK levels and α-ERK1/2 for total ERK levels. (b) Effect of TTN on GM-CSF-stimulated hyperproliferation of SHP2/E76K-expressing hematopoietic progenitors. 3H-thymidine incorporation assay of transduced, sorted bone marrow LDMNCs in the presence of GM-CSF 1 ng/mL +/− 2 µM TTN, (two independent experiments, cultures plated in triplicate, *p=0.02 for SHP2/E76K in 2 µM TTN vs. SHP2/E76K in DMSO). (c) Effect of TTN on GM-CSF-stimulated monocytic differentiation of SHP2-bearing hematopoietic progenitors. Transduced, sorted bone marrow LDMNCs plated into methylcellulose-based colony assays in GM-CSF 1 ng/mL +/− 2 µM TTN, colony morphology (CFU-GM or CFU-M) was assessed by light microscopy, n=2, *p=0.03 for SHP2/E76K CFU-M in 2 µM TTN vs. SHP2/E76K CFU-M in DMSO.

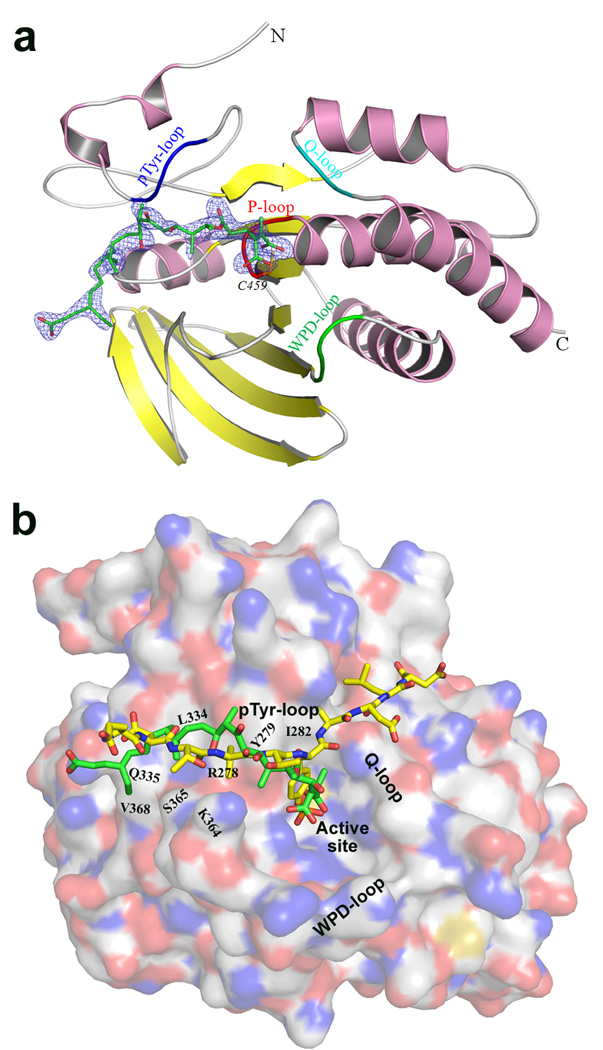

Structural basis of TTN/TTN D-1 specificity for SHP2

To provide further evidence that SHP2 is a molecular target of TTN, we determined the crystal structure of SHP2 in complex with TTN D-1, as crystallization attempts for the SHP2-TTN complex were unsuccessful. The structure of SHP2•TTN D-1 was solved by molecular replacement, using the apo-form of SHP2 catalytic domain as the search model (Barr et al., 2009), and refined to a crystallographic R-factor of 16.7% (Rfree 21.5%) at 2.3 Å resolution. Table 2 summarizes data collection and refinement statistics. The atomic model of SHP2•TTN D-1 includes one protein monomer in an asymmetric unit, which contains residues 262–313, 325–526 and all atoms of TTN D-1. The structure of SHP2•TTN D-1 is similar to the apo structure used for molecular replacement modeling, with an overall root-mean-square-derivation (RMSD) of 0.38 Å between all Cα atoms. The existence of TTN D-1 in the complex was revealed by the unbiased Fo − Fc difference map (Figure 4a). Unambiguous electron densities were observed for all surface loops except loop F314-K324, including the PTP signature motif or the P-loop (residues 458–465, which harbors the active site nucleophile C459 and R465 for recognition of the phosphoryl moiety in the substrate), the pTyr recognition loop (residues 277–284, which confers specificity to pTyr), the WPD loop (residues 421–431, which contains the general acid-base catalyst D425), and the Q-loop (residues 501–507, which contains the conserved Q506 required to position and activate a water molecule for hydrolysis of the phosphoenzyme intermediate) (Zhang, 2003).

Table 2.

Crystallographic Data and Refinement Statistics for SHP2•TTN D-1 Complex

| Data Collection | |

| Space group | P21 |

| Cell Dimensions | |

| a (Å) | 39.5 |

| b (Å) | 76.0 |

| c (Å) | 48.4 |

| β (deg) | 98.9 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.00 - 2.30 |

| Highest resolution shell (Å) | 2.38 - 2.30 |

| Unique observations | 12,544 |

| Completeness (%) | 97.5 (74.6)a |

| Redundancy | 3.6 |

| Rmerge (%)b | 5.6 (25.2)a |

| <I>/<σI> | 19.7 (2.5)a |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.00 ~ 2.30 |

| No. of reflections used (F≥1.5σF) | 11,753 |

| Rworkc/Rfreed (%) | 16.7/21.5 |

| No. of atoms | |

| protein | 2,070 |

| inhibitor (1 molecule) | 46 |

| waters | 156 |

| RMS deviations from ideal | |

| bonds (Å) | 0.0058 |

| angles (deg) | 1.17 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 31.9 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| allowed | 99.6 |

| not allowed | 0.4 |

The value in parentheses corresponds to the highest resolution shell.

Rmerge = ΣhΣi|I(h)i − 〈I(h)〉|/ΣhΣiI(h)i.

Rwork = Σh|F(h)calcd − F(h)obsd|/ΣhF(h)obsd, where F(h)calcd and F(h)obsd were the refined calculated and observed structure factors, respectively.

Rfree was calculated for a randomly selected 3.9% of the reflections that were omitted from refinement.

Figure 4.

Structure of TTN D-1 bound SHP2. (a) Ribbon diagram of SHP2 catalytic domain in complex with TTN D-1. α-helices and β-strands are colored in pink and yellow, respectively. The P-loop is shown in red, the WPD loop in green, pTyr loop in blue, and Q loop in cyan. TTN D-1 is shown in stick model with unbiased Fo−Fc map contoured at 3.0 σ calculated before the ligand and waters were added to the model. (b) Binding mode comparison between SHP2•TTN D-1 and SHP1•pTyr peptide substrate. The structure of SHP1•peptide (PDB accession #: 1FPR) was superimposed onto our structure of SHP2•TTN D-1. The peptide (EDILTpYADLD) (yellow) and TTN D-1 (green) are shown in stick model.

Under neutral conditions, both TTM and TTN exist as equilibrating mixtures of two interconverting anhydride and diacid forms in an approximately 5:4 ratio (Cheng et al., 1987; Cheng et al., 1990a&b) (Figure 1b). As shown in Figure 4a, TTN D-1 binds to SHP2 in an extended conformation, with the diacid moiety penetrating into SHP2 active site. This is consistent with TTN and TTN D-1 being competitive inhibitors of SHP2 (Figure S2). Interestingly, if the structure of phosphopeptide-bound SHP1 (Yang et al., 2000), a close homolog of SHP2, predicts the orientation of substrate peptide binding to SHP2, then the polyketide backbone of TTN D-1 in our structure occupies exactly where substrate residues N-terminal to pTyr would otherwise bind in SHP2 (Figure 4b). Superimposition of the SHP1•phosphopeptide structure onto that of SHP2•TTN D-1 reveals that the diacid moiety is localized at almost the same position of pTyr, and the remaining polyketide backbone of TTN D-1 occupies the substrate-binding groove defined by I282, Y279, R278, Q335, K364, S365, L334 and V368. Thus, the binding mode of TTN D-1 mimics that of pTyr peptide substrates.

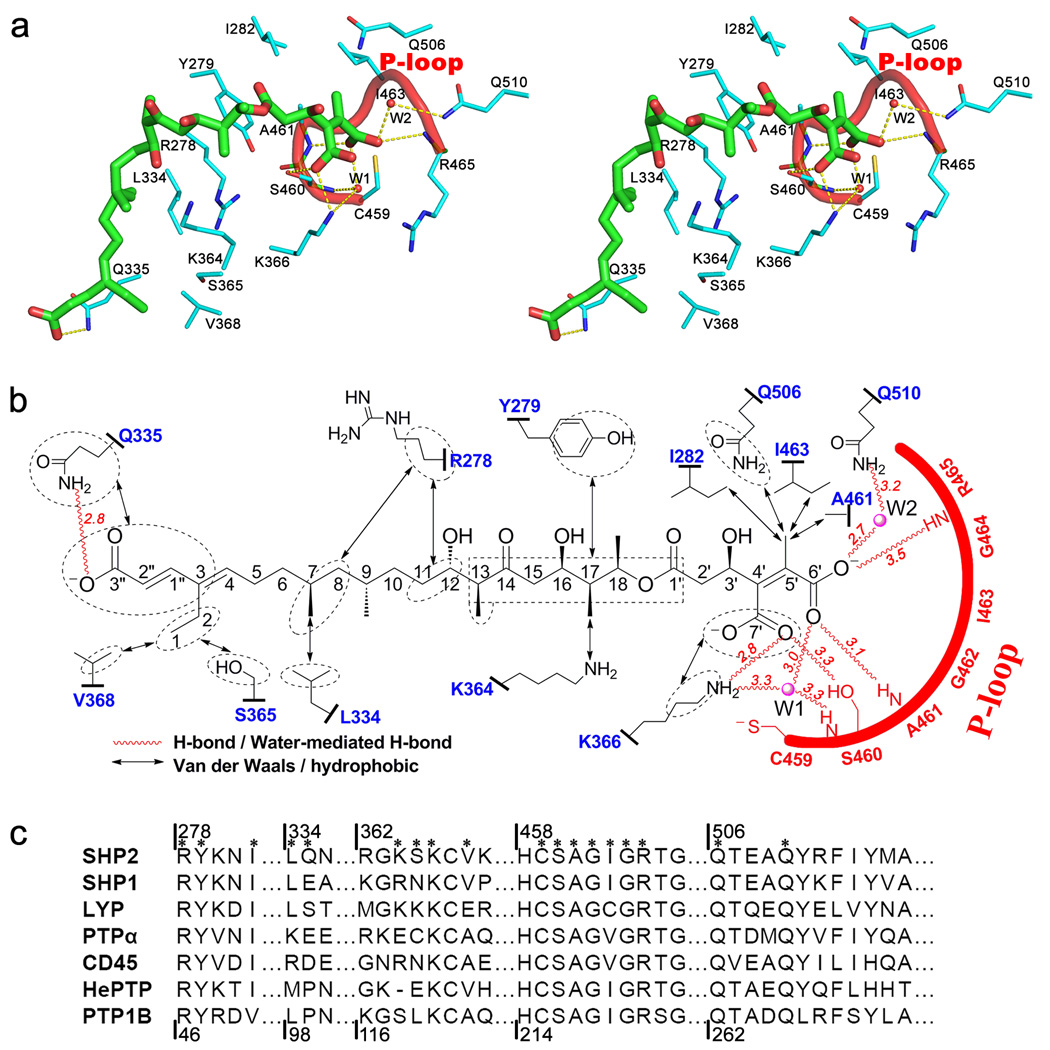

A rich network of interactions is responsible for the precise positioning of TTN D-1 in the complex (Figure 5). The TTN D-1 diacid is anchored via four direct and three water-mediated hydrogen bonds with SHP2 active site residues R465, A461, S460, Q510, and K366, consistent with the diacid form as the active isomer for SHP2 inhibition. Specifically, the carboxylate group attached to C6’ makes two H-bonds with the main-chain amides of A461 and R465 in the P-loop, and also engages in polar interactions with the main chain of S460 as well as side chains of K366 and Q510, which are mediated by waters W1 and W2. One of the C7’ carboxylate oxygen interacts directly with the side chains of S460 and K366.

Figure 5.

Potential interactions between SHP2 and TTN D-1. (a) Stereo view showing interactions between TTN D-1 and SHP2. TTN D-1 (green carbon) and interacting residues in SHP2 (cyan carbon) are represented in stick model, and P-loop is depicted in red cartoon. Yellow dash lines indicate H-bond interactions. (b) Interaction diagram of TTN D-1 and SHP2. The number adjacent to each H-bond indicates the distance (in Å) between two polar heavy atoms. (c) Amino acid sequence alignment of 7 human PTPs for which selectivity data were obtained for TTN and TTN D-1. Residues involved in the interaction with TTN D-1 revealed by our structure are marked by *; Sequence numbers in SHP2 and PTP1B are labeled at the top and bottom, respectively.

In addition to the polar interactions between the diacid head group and SHP2 active site, the rest of the TTN D-1 molecule is primarily involved in hydrophobic interactions with SHP2 (Figure 5). The methyl group connected to C5’ sits within a hydrophobic pocket consisting of A461, I463, I282, and Q506, which further tighten-up the interaction of the diacid moiety with SHP2 active site. The polyketide backbone bends around the phenyl ring of Y279 and makes Van der Waals contacts with a number of residues lining the hydrophobic groove. These include interactions between the side chain of Y279 and carbon atoms from C1’ to C13; Cα, Cβ and Cγ of R278 with C8, C11 and C12; K364 with the methyl group on C17; L334 with the methyl group on C7; S365 and V368 with C1 and C2, and Q335 with the acrylic acid tail. Finally, the terminal carboxylate at C3” is bound primarily through a H-bond with the side chain of Q335.

Our biochemical and cellular data indicate that TTN and TTN D-1 exhibit similar affinity for SHP2. As shown in Figure 1, TTN differs from TTN D-1 only in the very right end portion of the molecule with TTN D-1 bearing an extra carboxyl group at C3” but lacking the ketone at C5 (Figure 1). This suggests that the left-hand side of these compounds is essential for SHP2 inhibition but the end of the right-half is exchangeable. Indeed, the structure of SHP2•TTN D-1 reveals that binding of TTN D-1 to SHP2 is dominated by the left 2/3 of TTN D-1, which is identical in TTN (Figure 5a&b). Molecular modeling indicates that a new polar interaction could form between the C5 carbonyl in TTN and the side chain of R278, which may compensate for the lost polar interaction between Q335 and C3”-COOH in TTN D-1.

In addition to revealing a molecular mechanism for SHP2 inhibition by TTN D-1 and TTN, the structure of the SHP2•TTN D-1 complex also provides a potential explanation for the inactivity of TTM toward SHP2. The major structural differences between TTM and TTN reside in the region distal to the diacid moiety (Figure 1). Assuming that the left-half of the TTM molecule binds SHP2 in the same manner as TTN D-1 does, the rigid and twisted spiroketal moiety will experience severe steric clash with residues R278 and L334. This illustrates why TTM and analogs lack SHP2 inhibitory activity. Finally, the structure of the SHP2•TTN D-1 complex identifies 18 SHP2 residues involved in binding TTN D-1 (Figure 5c). Although many of the residues important for TTN D-1 recognition are not unique to SHP2, no single PTP has the same combinations of all contact residues, which suggest that the binding surface defined by these residues in SHP2 is unique and likely responsible for the observed TTN/TTN D-1 selectivity. For example, the corresponding residues of Q335, K364 and S365 are switched to Glu, Arg and Asn in SHP1 (Figure 5b&c), which may account for the observed difference in TTN and TTN D-1 binding affinity between SHP1 and SHP2.

DISCUSSION

The immunosuppressive activity exhibited by TTN differs from other bacteria and fungi derived immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclosporin A (CsA), FK506 (tacrolimus), and rapamycin (Gerber et al., 1998). CsA and FK506 exert their pharmacological effects by binding to endogenous proteins called immunophilins, and the immunophilin and drug complex inhibits the activity of the serine/threonine protein phosphatase calcineurin (PP2B) (Liu et al., 1991), which is activated when intracellular calcium level rises upon T cell activation (Flanagan et al., 1991; Bierer et al., 1990). Similar to FK506, rapamycin also binds to the FK506-binding protein family of immunophilins. However, the complex of rapamycin/FK506-binding protein has no effect on calcineurin activity but instead blocks the TOR (target of rapamycin) pathway triggered by the IL-2 receptor (Chung et al., 1992; Kuo et al., 1992). In contrast, the immunosuppressive activity of TTN results from its ability to block tyrosine phosphorylation of intracellular signaling molecules downstream of the TCR (Shim et al., 2002), although the mechanistic basis of TTN’s immunosuppressive activity remains to be established.

Originally isolated as antifungal antibiotics, the only known biochemical activity for TTN and its structurally related natural product TTM is their ability to inhibit serine/threonine protein phosphatases PP1 and PP2A (MacKintosh and Klumpp, 1990; Mitsuhashi et al., 2001). Since TTM does not elicit any immunosuppressive activity (Shim et al., 2002), it is unlikely that TTN’s immunosuppressive activity results from PP1 or PP2A inhibition. Instead, a yet unidentified molecular target may be required to explain the immunosuppressive activity of TTN. In this study, we establish that TTN and its engineered analog TTN D-1 are potent and competitive SHP2 inhibitors. We provide evidence that TTN and TTN D-1 block tyrosine phosphorylation and ERK activity in T cells and attenuate gain-of-function SHP2-induced hematopoietic progenitor hyperproliferation and monocytic differentiation. In addition, we obtain a crystal structure of SHP2 with TTN D-1 bound to its active site, which offers molecular insights into the origin of TTN/TTN D-1 selectivity for SHP2. Collectively, the biochemical, cellular and structural data support the notion that SHP2 is a cellular target for TTN, and furnish a plausible mechanism for TTN’s observed immunosuppressive and anticancer activity.

Protein tyrosine phosphorylation is the key cellular event that controls TCR signaling. The Src family kinases are responsible for tyrosine phosphorylation of intracellular signaling molecules downstream of the TCR (Brdicka et al., 2005). SHP2 exerts a positive effect on cell signaling, and is required for Src and Ras-ERK1/2 activation downstream of most growth factor and cytokine receptors, including TCR (Neel et al., 2003; Tiganis and Bennett; 2007; Nguyen et al., 2006). SHP2 can activate the Src kinases by dephosphorylating Csk (C-terminal Src kinase) binding protein Cbp/PAG, which prevents the access of Csk (which inactivates Src) to the Src kinases (Zhang et al., 2004). Ras activation by SHP2 involves SHP2 catalyzed dephosphorylation of tyrosine-phosphorylated sites of receptor molecules that bind p120 RasGAP (Agazie and Hayman, 2003) and Sprouty (Hanafusa et al., 2004), a negative regulator of Ras. Thus, the observed decrease in TCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation and ERK1/2 activation by TTN is fully consistent with TTN being an inhibitor of SHP2. However, this does not exclude the possibility that other targets (e.g. PP1 and PP2A) may also contribute to TTN’s biological activities. In this regard, we note that although TTN inhibits PP1 and PP2A in the low nM range in biochemical assays, often 1–5 µM concentrations of TTN are required to exert a cellular effect (Luo et al., 2002; Mitsuhashi et al., 2003; Mitsuhashi et al., 2008). As shown in this study, TTN at this concentration range will also inhibit SHP2 activity. Future investigation with more potent and selective small molecule probes will be required to resolve whether TTN’s immunosuppressive effect results primarily from SHP2 inhibition.

The PTP family provides an exciting array of validated (Zhang, 2001) but previously deemed undruggable diabetes/obesity, autoimmunity and oncology targets. Identification of the polyketide natural product TTN as a SHP2 inhibitor has profound implication in drug discovery targeting the PTPs, which have proven to be exceptionally challenging targets for the development of new therapeutic agents. The main problem is poor membrane permeability and lack of cellular efficacy of existing PTP inhibitors, which have limited further advancement of such compounds as drug candidates (Zhang and Zhang, 2007). Bioactive natural products are very promising leads for drug development because they are evolutionarily selected and validated for interfering and interacting with biological targets. Given its excellent in vivo activity, TTN serves as a promising lead for the development of more potent and specific SHP2 inhibitors. To this end, the crystal structure of SHP2 bound to TTN D-1 should facilitate structure-based design effort based on the TTN scaffold.

The fact that TTN is of microbial origin should greatly ease the concern to produce the complex natural product lead and generate its structural analogs for further mechanistic studies and clinical developments. Thus, promising leads of complex microbial natural products can be produced by large-scale fermentation, thereby significantly reducing production cost and environmental concerns. Furthermore, we have recently cloned and characterized the biosynthetic gene cluster for TTN in S. griseochromogenes (Li et al., 2009). Judicial application of the combinatorial biosynthetic strategies to the TTN biosynthetic machinery for TTN analogs has already been demonstrated (Luo et al., 2010), as exemplified by the discovery of TTN D-1 as an SHP2 inhibitor in this study. Taken together, the current study sets an outstanding stage to rationally engineer the TTN biosynthetic machinery, guided by the SHP2•TTN D-1 structure, for the development of novel analogs, some of which could be further exploited as SHP2-specific inhibitors for clinical applications in immunosuppression, leukemia, and cancer.

SIGNIFICANCE

TTN and its structurally related natural product TTM are potent inhibitors of PP1 and PP2A. Interestingly, TTN has been identified as an effective immunosuppressor in organ transplantation. Since TTM does not elicit any immunosuppressive activity, it is unlikely that TTN’s immunosuppressive activity results from PP1 or PP2A inhibition. Here we show that TTN and TTN D-1, an engineered analog of TTN, are competitive inhibitors of SHP2, a positive mediator for growth factor and cytokine signaling through activation of the Ras/ERK cascade and a bona fide oncogene associated with multiple forms of leukemia and solid tumors. Biochemical studies indicate that TTN and TTN D-1 block SHP2-mediated pathways and the crystal structure of the SHP2•TTN D-1 complex reveals that TTN D-1 occupies the SHP2 active site in a manner similar to that of a peptide substrate. Collectively, the work is significant for two major reasons. (1) It identifies SHP2 as a novel cellular target for TTN and provides a potential mechanism for the immunosuppressive activity of TTN. (2) It furnishes a novel natural product scaffold for the development of therapeutic agents for a large family of validated but previously deemed undruggable PTP targets, including SHP2.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

TTM, TTN, and the engineered analogs are produced as described previously (Li et al., 2008; Ju et al., 2009; Li et al., 2009; Luo et al., 2010). Polyethylene glycol (PEG3350) and buffers for crystallization were purchased from Hampton Research Co. p-Nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) was purchased from Fluke Co. Dithiothreitol (DTT) was provided by Fisher (Fair Lawn, NJ). All of other chemicals and reagents were of the highest commercially available grade. The expression and purification of the SHP2 catalytic domain (residues 262–528) were described previously (Zhang et al., 2010).

Kinetic analysis of SHP2 inhibition by TTM, TTN and analogs

The PTP activity was assayed using pNPP as a substrate at 25°C in 50 mM 3,3-dimethylglutarate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 1 mM EDTA with an ionic strength of 0.15 M adjusted by NaCl. TTM, TTN and the engineered analogs were analyzed for inhibition of a panel of PTPs at 10 µM compound concentration. For each enzyme screened, test compounds were diluted to 20 µM in 100 µL and combined with 50 µL pNPP at a concentration of 4X Km. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 50 µL of 4X concentrated enzyme and pNPP was allowed to convert to the product p-nitrophenol. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 50 µL of 5N NaOH. Nonenzymatic hydrolysis of pNPP was corrected by measuring the control without the addition of enzyme. Production of p-nitrophenol was monitored by a Spectra MAX385 microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices) at 405 nm using a molar extinction coefficient of 18,000 M−1cm−1. IC50 values were calculated by fitting the absorbance at 405 nm versus inhibitor concentration to the following equation:

where AI is the absorbance at 405 nm of the sample in the presence of inhibitor; A0 is the absorbance at 405 nm in the absence of inhibitor; and [I] is the concentration of the inhibitor.

Ki Measurement

The SHP2-catalyzed hydrolysis of pNPP in the presence of TTN or TTN D-1 was assayed at 25 °C and in the assay buffer described above. The mode of inhibition and Ki value were determined in the following manner. At various fixed concentrations of the inhibitor (0–3 Ki), the initial rate at a series of pNPP concentrations was measured by following the production of p-nitrophenol as describe above, ranging from 0.2- to 5-fold the apparent Km values. The data were fitted to appropriate equations using SigmaPlot-Enzyme Kinetics to obtain the inhibition constant and to assess the mode of inhibition.

Cell Culture and Immunoblotting

Jurkat T cells were grown at 37 °C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were pretreated with different concentrations of TTN, TTN D-1, or TTM for 2 hours and stimulated with 10 µg/mL anti-CD3 antibody (OKT3; eBioscience) for 5 min and 30 min, respectively. Subsequently, cells were spinned down at 2000rpm in 4°C, and cell pellets were lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 50 mM NaF, 10 mM pyrophosphate, 5 mM idoacetate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and the protease inhibitor mixture. After 30 min lysing on ice, the cell lysates were centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 15 min. Total cellular proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose membrane, which was immunoblotted by appropriate antibodies followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Blots were developed using Pierce Pico ECL reagent (Thermo) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Biochemical Analysis

Bone marrow low density mononuclear cells (LDMNCs) were transduced with MIEG3 (empty vector), MIEG3-WT SHP2, or MIEG3-SHP2/E76K, sorted based on enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression, and cultured for 5 days in M-CSF 100 ng/mL to generate macrophage progenitors, as previously described20. Cells were serum- and growth factor-deprived for 16 hours, treated with 2 µM TTN for 2 hours, and stimulated with GM-CSF 50 ng/mL followed by preparation of protein extracts. Extracts were evaluated by immunoblot using α-phospho-ERK1/2 for activated ERK levels and α-ERK1/2 for total ERK levels (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA).

Hematopoietic Progenitor Analysis

Transduced, EGFP+ cells were subjected to 3H-thymidine incorporation assays, as previously described (Munugalavadla et al., 2007), or plated at a concentration of 8000 cells/mL in 0.9% methylcellulose-based media containing IMDM, 2 mM glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 80 µM β-mercaptoethanol, 30% FBS, and GM-CSF 1 ng/mL or with saturating concentrations of growth factors including IL-3 200 U/mL, erythropoietin 4 U/mL, and stem cell factor (SCF) 100 ng/mL. All growth factors were from Peprotech. Cultures were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37° C in 5% CO2 for 7 days and were scored for total colonies and for morphology to determine colony forming unit (CFU)-granulocyte-macrophage (GM) or CFU-monocyte (M).

Crystallization of SHP2 with TTN D-1 and X-ray Data Collection

All crystallization experiments were carried out at room temperature using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. For co-crystallization, 100 µL of the SHP2 stock (7.0 mg/mL) in 20 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 3.0 mM DTT was mixed with 1 µL of TTN D-1 stock (50 mM in DMSO). Protein drops were equilibrated against a reservoir solution containing 25% w/v polyethylene glycol 3350, 100 mM sodium chloride, and 100 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5). For X-ray data collection, the crystals were transferred into 5 µL of cryoprotectant buffer containing 30% w/v polyethylene glycol 3350, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM TTN D-1 and 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), and were allowed to soak for 30 min. The crystals were then flash-cooled by liquid nitrogen. X-ray data were collected at 19BM beamline at APS (Argonne, IL). Data were processed using the program HKL3000 (Otwinowski and Minow, 1997), and the statistics are provided in Table 2.

Structural Determination and Refinement

The structure of SHP2•TTN D-1 was solved by molecular replacement using the program AMoRe (Navaza, 1994). The apo structure of SHP2 (PDB entry code 3B7O) (Barr et al., 2009), without the solvent molecules and first 16 residues, was used as a search model. The resulting difference Fourier map indicated some alternative tracing, which was incorporated into the model. The map revealed the density for the bound TTN D-1 in the SHP2 active site. The structure was refined to 2.3 Å resolution with the program CNS1.1 (Brünger et al., 1998), first using simulated annealing at 2,500 K, and then alternating positional and individual temperature factor refinement cycles. The progress of the refinement was evaluated by the improvement in the quality of the electron density maps, and the reduced values of the conventional R factor (R = Σh||Fo| − |Fc||/Σh|Fo|), and the free R factor (3.8% of the reflections omitted from the refinement) (Brünger, 1992). Electron density maps were inspected and the model was modified on an interactive graphics workstation with the program O (Jones et al., 1991). Finally, water molecules were added gradually as the refinement progressed. They were assigned in the Fo − Fc difference Fourier maps with a 3σ cutoff level for inclusion in the model. The geometry of the final models was examined with the program PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993). The complex structure had 99.6% of the residues in the allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants CA69202, CA126937, CA113297, HL082981, and HL092524. Y.L. is the recipient of a visiting scholar fellowship from Chinese Academy of Sciences. The authors also wish to thank Jun O. Liu for very helpful comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- PTP

protein tyrosine phosphatase

- SHP2

Src homology-2 domain containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2

- TTM

tautomycin

- TTN

tautomycetin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data deposition: The coordinates for the structure of the SHP2•TTN D-1 complex (accession number 3MOW) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank.

References

- Agazie YM, Hayman MJ. Molecular mechanism for a role of SHP2 in epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:7875–7886. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7875-7886.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr AJ, Ugochukwu E, Lee WH, King ON, Filippakopoulos P, Alfano I, Savitsky P, Burgess-Brown NA, Müller S, Knapp S. Large-scale structural analysis of the classical human protein tyrosine phosphatome. Cell. 2009;136:352–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierer BE, Mattila PS, Standaert RF, Herzenberg LA, Burakoff SJ, Crabtree G, Schreiber SL. Two distinct signal transmission pathways in T lymphocytes are inhibited by complexes formed between an immunophilin and either FK506 or rapamycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:9231–9235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brdicka T, Kadlecek TA, Roose JP, Pastuszak AW, Weiss A. Intramolecular regulatory switch in ZAP-70: analogy with receptor tyrosine kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:4924–4933. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.4924-4933.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT. Free R value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature. 1992;355:472–475. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan G, Kalaitzidis D, Neel BG. The tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 (PTPN11) in cancer. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2008;27:179–192. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9126-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RJ, Leedy MB, Munugalavadla V, Voorhorst CS, Li Y, Yu M, Kapur R. Human somatic PTPN11 mutations induce hematopoietic-cell hypersensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 2005;105:3737–3742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XC, Kihara T, Kusakabe H, Magae J, Kobayashi Y, Fang RP, Ni ZF, Shen YC, Ko K, Yamaguchi I, et al. A new antibiotic, tautomycin. J. Antibiot. 1987;40:907–909. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XC, Kihara T, Ying X, Uramoto M, Osada H, Kusakabe H, Wang BN, Kobayashi Y, Ko K, Yamaguchi I, et al. A new antibiotic, tautomycetin. J. Antibiot. 1989;42:141–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XC, Ubukata M, Isono K. The structure of tautomycetin, a dialkylmaleic anhydride antibiotic. J. Antibiot. 1990a;43:890–896. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XC, Ubukata M, Isono K. The structure of tautomycin, a dialkylmaleic anhydride antibiotic. J. Antibiot. 1990b;43:809–819. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J, Kuo CJ, Crabtree GR, Blennis J. Rapamycin-FKBP specifically blocks growth-dependent activation of and signaling by the 70 kd S6 protein kinases. Cell. 1992;69:1227–1236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90643-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel PD, Bates LJ, Castleberry RP, Gualtieri RJ, Zuckerman KS. Selective hypersensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by juvenile chronic myeloid leukemia hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 1991;77:925–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan WM, Corthesy B, Bram RJ, Crabtree GR. Nuclear association of a T-cell transcription factor blocked by FK-506 and cyclosporin A. Nature. 1991;352:803–807. doi: 10.1038/352803a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber DA, Bonham CA, Thomson AW. Immunosuppressive agents: recent developments in molecular action and clinical application. Transplant. Proc. 1998;30:1573–1579. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han DJ, Jeong YL, Wee YM, Lee AY, Lee HK, Ha JC, Lee SK, Kim SC. Tautomycetin as a novel immunosuppressant in transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:547. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03905-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanafusa H, Torii S, Yasunaga T, Matsumoto K, Nishida E. Shp2, an SH2-containing protein-tyrosine phosphatase, positively regulates receptor tyrosine kinase signaling by dephosphorylating and inactivating the inhibitor Sprouty. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:22992–22995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312498200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. Signaling – 2000 and beyond. Cell. 2000;100:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard GJ. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju J, Li W, Yuan Q, Peters NR, Hoffmann FM, Rajski SR, Osada H, Shen B. Functional chacaterization of ttm unvels new tautomycin analogs and insights into tautomycin biosynthesis and activity. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1639–1642. doi: 10.1021/ol900293j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CJ, Chung J, Fiorentino DF, Flanagan WM, Blenis J, Crabtree GR. Rapamycin selectively inhibits interleukin-2 activation of p70 S6 kinase. Nature. 1992;358:70–73. doi: 10.1038/358070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Hutchinson SG, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Lee JS, Kim SE, Moon BS, Kim YC, Lee SK, Lee SK, Choi KY. Tautomycetin inhibits growth of colorectal cancer cells through p21cip/WAF1 induction via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5:3222–3231. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Ju J, Rajski SR, Osada H, Shen B. Characterization of the tautomycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces spiroverticillatus unveiling new insights into dialkylmaleic anhydride and polyketide biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:28607–28617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804279200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Luo Y, Ju J, Rajski SR, Osada H, Shen B. Characterization of the Tautomycetin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces griseochromogenes provides new insight into dialkylmaleic anhydride biosynthesis. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:450–459. doi: 10.1021/np8007478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Farmer JD, Jr, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell. 1991;66:807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Li W, Ju J, Yuan Q, Peters NR, Hoffmann FM, Huang SX, Bugni TS, Rajski S, Osada H, et al. Functional characterization of TtnD and TtnF, unveiling new insights into tautomycetin biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6663–6671. doi: 10.1021/ja9082446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Peterson A, Garcia BA, Coombs G, Kofahl B, Heinrich R, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Yost HJ, Virshup DM. Protein phosphatase 1 regulates assembly and function of the beta-catenin degradation complex. EMBO J. 2007;26:1511–1521. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKintosh C, Klumpp S. Tautomycin from the bacterium Streptomyces verticillatus. Another potent and specific inhibitor of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A. FEBS Lett. 1990;277:137–140. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80828-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi S, Matsuura N, Ubukata M, Oikawa H, Shima H, Kikuchi K. Tautomycetin is a novel and specific inhibitor of serine/threonine protein phosphatase type 1, PP1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;287:328–331. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi S, Shima H, Tanuma N, Matsuura N, Takekawa M, Urano T, Kataoka T, Ubukata M, Kikuchi K. Usage of tautomycetin, a novel inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), reveals that PP1 is a positive regulator of Raf-1 in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:82–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi S, Shima H, Li Y, Tanuma N, Okamoto T, Kikuchi K, Ubukata M. Tautomycetin suppresses the TNFalpha/NF-kappaB pathway via inhibition of IKK activation. Int. J. Oncol. 2008;33:1027–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munugalavadla V, Sims EC, Borneo J, Chan RJ, Kapur R. Genetic and pharmacologic evidence implicating the p85 alpha, but not p85 beta, regulatory subunit of PI3K and Rac2 GTPase in regulating oncogenic KIT-induced transformation in acute myeloid leukemia and systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2007;110:1612–1620. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-053058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaza J. AMoRe: an automated package for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1994;50:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Neel BG, Gu H, Pao L. The 'Shp'ing news: SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatases in cell signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:284–293. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TV, Ke Y, Zhang EE, Feng GS. Conditional deletion of Shp2 tyrosine phosphatase in thymocytes suppresses both pre-TCR and TCR signals. J. Immunol. 2006;177:5990–5996. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minow W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JH, Lee HK, Chang EJ, Chae WJ, Han JH, Han DJ, Morio T, Yang JJ, Bothwell A, Lee SK. Immunosuppressive effects of tautomycetin in vivo and in vitro via T cell-specific apoptosis induction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:10617–10622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162522099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia M, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome and related disorders: genetics and pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2005;6:45–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiganis T, Bennett AM. Protein tyrosine phosphatase function: the substrate perspective. Biochem. J. 2007;402:1–15. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonks NK. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: from genes, to function, to disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:833–846. doi: 10.1038/nrm2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Cheng Z, Niu T, Liang X, Zhao ZJ, Zhou GW. Structural basis for substrate specificity of protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:4066–4071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Kondo T, Voorhorst CS, Nabinger SC, Ndong L, Yin F, Chan EM, Yu M, Würstlin O, Kratz CP, et al. Increased c-Jun expression and reduced GATA2 expression promote aberrant monocytic differentiation induced by activating PTPN11 mutants. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;29:4376–4393. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01330-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Li Y, Yin F, Chan RJ. Activating PTPN11 mutants promote hematopoietic progenitor cell-cycle progression and survival. Exp. Hematol. 2008;36:1285–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Zhang Z-Y. PTP1B as a drug target: recent development in PTP1B inhibitor discovery. Drug Discovery Today. 2007;12:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SQ, Yang W, Kontaridis MI, Bivona TG, Wen G, Araki T, Luo J, Thompson JA, Schraven BL, Philips MR, et al. Shp2 regulates SRC family kinase activity and Ras/Erk activation by controlling Csk recruitment. Mol. Cell. 2004;13:341–355. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, He Y, Liu S, Yu Z, Jiang ZX, Yang Z, Dong Y, Nabinger SC, Wu L, Gunawan AM, et al. Salicylic acid-based small molecule inhibitor for the oncogenic Src homology-2 domain containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2 (SHP2) J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:2482–2493. doi: 10.1021/jm901645u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z-Y. Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases: Prospects for Therapeutics. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2001;5:416–423. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z-Y. Mechanistic studies on protein tyrosine phosphatases. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. & Mol. Biol. 2003;73:171–220. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(03)01006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.