Abstract

Lower urinary tract function is regulated by spinal and supraspinal reflexes that coordinate the activity of the urinary bladder and external urethral sphincter (EUS). Two types of EUS activity (tonic and bursting) have been identified in rats. This study in urethane-anesthetized female rats used cystometry, EUS electromyography, spinal cord transection (SCT) at different segmental levels, and analysis of the effects of 5-HT1A receptor agonist (8-OH-DPAT) and antagonist (WAY100635) drugs to examine the origin of tonic and bursting EUS activity. EUS activity was elicited by bladder distension or electrical stimulation of afferent axons in the pelvic nerve (pelvic-EUS reflex). Tonic activity evoked by bladder distension was detected in spinal cord-intact rats and after acute and chronic T8–9 or L3–4 SCT but was abolished after L6–S1 SCT. Bursting activity was abolished by all types of SCT except chronic T8–9 transection. 8-OH-DPAT enhanced tonic activity, and WAY100635 reversed the effect of 8-OH-DPAT. The pelvic-EUS reflex consisted of an early response (ER) and late response (LR) when the bladder was distended in spinal cord-intact rats. ER remained after acute or chronic T8–9 and L3–4 SCT, but was absent after L6–S1 SCT. LR occurred only in chronic T8–9 SCT rats where it was enhanced or unmasked by 8-OH-DPAT. The results indicate that spinal serotonergic mechanisms facilitate tonic and bursting EUS activity. The circuitry for generating different patterns of EUS activity appears to be located in different segments of the spinal cord: tonic activity at L6–S1 and bursting activity between T8–9 and L3–4.

Keywords: bladder, electromyography, 5-HT1A receptor, pelvic nerve, bursting

The storage and release of urine are dependent on the coordinated activity of the urinary bladder smooth muscle and the external urethral sphincter (EUS) striated muscle in the lower urinary tract (LUT). This coordination is mediated by neural mechanisms in the brain and spinal cord that are stimulated by afferent input from the bladder. In normal rats, the EUS exhibits tonic activity before the onset of voiding and bursting activity during voiding. It is believed that bursting activity represents rhythmic contractions and relaxations of the EUS that are necessary for efficient bladder emptying (20). A detailed analysis (4) of the EUS bursting pattern has shown that it consists of silent (urethral opening) and active (urethral closing) periods, averaging 104 and 67 ms in duration, respectively. Efficient voiding depends on the duration and number of urethral openings during voiding. Suppression of EUS bursting activity with neuromuscular blocking agents decreases voiding efficiency (31).

Initial studies in deeply anesthetized rats indicated that tonic EUS activity elicited by bladder distension persists after acute or chronic transection of the thoracic spinal cord, whereas EUS bursting is eliminated in spinal cord-transected animals (15, 16). However, subsequent experiments revealed that EUS bursting does occur in lightly anesthetized or awake rats in which the thoracic spinal cord was transected 4–6 wk before the experiments (4), indicating that both patterns of EUS activity can be generated by circuitry in the lumbosacral spinal cord.

EUS electromyography (EMG) activity is also evoked by electrical stimulation of bladder afferent axons in the pelvic nerve (pelvic-EUS reflex) (1). Evoked reflexes consisted of transient early responses (ER) and prolonged late responses (LR) composed of burst firing. The LR but not the ER was abolished by acute spinal cord transection (SCT) at T8–9. It was proposed that ER and LR might be mediated, respectively, by the reflex circuits responsible for tonic and bursting EUS activity.

Bursting activity has also been identified in the periurethral striated muscles (bulbocavernosus and ischiocavernous muscles) involved in ejaculation in male rats (22). The ejaculation reflex is mediated by a spinal pattern generator (6, 29) located in L3–4 spinal segments. Because pseudorabies virus (PRV) tracing studies also revealed PRV-labeled neurons in this same region following injection of PRV into the EUS of female rats (21), we hypothesized that neurons in the L3–4 spinal segments might be involved in the generation of EUS bursting activity during voiding. This possibility was examined by evaluating the effect of acute or chronic transection of the spinal cord at several segmental levels (T8–9, L3–4, or L6–S1) on 1) tonic and bursting EUS activity induced by bladder distension and 2) the ER and LR evoked by pelvic nerve stimulation.

In the same animals, we also conducted pharmacological experiments to evaluate the effects of a 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)-tetralin (8-OH-DPAT) and antagonist N-[2-[4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1-piperazinyl] ethyl]-N-(2-pyridinyl) cyclohexanecarboxamide trihydrochloride (WAY100635) to determine whether serotonergic modulation of tonic and bursting EUS activity is mediated by drug actions on different levels of the spinal cord. A previous study (18) showed that 8-OH-DPAT enhanced reflex micturition when administered intravenously, intrathecally, or intracerebroventricularly. On the other hand, WAY100635 suppressed reflex micturition when administered by the same routes (14, 25).

Preliminary findings have been presented (2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experiments were performed using urethane-anesthetized female Sprague-Dawley rats with an intact spinal cord (intact-SC, n = 10) or following acute (n = 18) or chronic (n = 18) transections of the spinal cord. To expose the dorsal surface of the spinal cord for acute transection, a laminectomy was performed under urethane (1.2 g/kg sc) anesthesia at spinal segments T8–9 (n = 7), L3–4 (n = 7), or L6–S1 (n = 4) 1–2 h before the physiological recordings. The dura was left intact and covered with cotton soaked in mineral oil to prevent drying. Then, the skin incision was closed with sutures and the animal was turned over on its back to provide access to the urinary bladder and urethral sphincter. The experimental protocols were approved by University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Experiments on Spinal-Intact and Acute Spinal-Transected Rats

A polyethylene tube (PE-50) filled with physiological saline was inserted into the jugular vein for intravenous administration of drugs. The urinary bladder was exposed via a midline abdominal incision. A PE-50 catheter filled with saline was inserted through an incision in the bladder dome and secured with cotton thread. The catheter was attached to an infusion pump and a pressure transducer via a T connector. To record the EUS EMG, the pubic symphysis was removed to expose the urethra and EUS. Two fine, insulated silver-wire electrodes (0.05-mm diameter) with exposed tips were inserted into the muscle on both sides of the midurethra 5–8 mm from the bladder neck. The left pelvic nerve was isolated. By retracting skin flaps, a pool was formed around the pelvic nerve, bladder, and urethra and filled with mineral oil (37°C) to prevent drying. For electrical stimulation, bipolar silver-wire electrodes were positioned on a pelvic nerve (usually on the left side) at a location 3–5 mm from the major pelvic ganglion.

Urodynamic examination usually began 1–2 h after the induction of anesthesia. After the bladder was emptied, it was filled by continuous transvesical cystometry (CMG) at an infusion rate of 0.123 ml/min with physiological saline at room temperature. This procedure, which will be termed “bladder filling,” produces repeated micturition reflexes at intervals varying between 60 to 200 s. The urethral outlet was opened to allow fluid in the bladder to be eliminated during each micturition reflex. The EUS EMG activity was amplified 20,000-fold and filtered (high-frequency cutoff at 3,000 Hz and low-frequency cutoff at 100 Hz). Bladder pressure and EUS EMG activity were stored on a personal computer at the sampling rate of 2,500 Hz.

The pelvic nerve afferent-evoked EUS reflex (pelvic-EUS reflex) was studied before and after bladder distension. Bladder pressure was increased by injecting saline (0.2 ml) into the bladder (termed “bladder distension”). This volume is less than the volume (0.6–0.8 ml) necessary to induce micturition. The pelvic-EUS reflex was elicited by single shocks (Grass S88 stimulator) to the pelvic nerve and recorded from the EUS on the both sides. The electrical stimulation consisted of uniphasic pulses at frequencies between 0.1 and 1.0 Hz with a pulse width of 0.05 ms. Submaximal stimulus intensities that ranged between 4 and 10 V in different experiments were set in each experiment at four to six times the threshold for eliciting a detectable reflex. The evoked pelvic-EUS reflex activity was amplified 20,000-fold with a preamplifier (P511AC, Grass Instruments), filtered (high-frequency cutoff at 3,000 Hz, low-frequency cutoff at 3 Hz in combination with a 60-Hz notch filter), and sampled at 5,000 Hz.

After all control recordings were obtained, the animal was carefully turned to lie on its abdomen. The incision over the spinal cord was opened, and then the dura, spinal cord (caudal T9 spinal segment, caudal L4 spinal segment or rostral S1 spinal segment), and spinal roots were completely transected with fine iris scissors. The severed ends of the spinal cord typically retracted 1–2 mm and were inspected under a surgical microscope to ensure complete transection. In L6–S1 SCT rats, a 22-gauge needle was inserted into the spinal cord to destroy the remainder of the S1 spinal segment. Gelfoam was placed between the severed ends of the spinal cord. The overlying muscle and skin were sutured. The animal was then turned on its back. After 1 h, the electrophysiological recordings were repeated. Following the physiological experiments, an extensive laminectomy was performed at the spinal transection sites to confirm the extent of the transections. In all animals, it was obvious that the cord was completely sectioned because the rostral and caudal segments of the cord were completely disconnected.

Experiments in Chronic Spinal Cord-Injured Rats

Animals were examined 2–5 wk after SCT at different spinal segments: T8–9 (n = 6), L3–4 (n = 7), and L6–S1 (n = 5). Spinal transection was performed under 2–2.5% halothane anesthesia using aseptic surgical technique as described above. After the laminectomy, the dura, the spinal cord (caudal T9 spinal segment, caudal L4 spinal segment or rostral S1 spinal segment), and spinal roots were cut with fine iris scissors. The severed ends of the spinal cord typically retracted 1–2 mm and were inspected under a surgical microscope to ensure complete transection. In L6–S1 SCT rats, a 22-gauge needle was inserted into the spinal cord to destroy the remainder of the S1 spinal segment. Gelfoam was placed between the severed ends of the spinal cord. The overlying muscle and skin were sutured. The animals were treated with an antibiotic (ampicillin 250 mg/kg sc) for 7–10 days. To prevent overdistension of the bladder, urine was expressed manually three times per day until automatic micturition developed (7–12 days postsurgery), and then the bladder was expressed one or two times per day.

The chronic SCT animals were studied under urethane anesthesia (0.8 g/kg sc). The surgical procedures were the same as those used in animals with acute spinal transection, including the placement of catheters in the jugular vein and bladder dome as well as placement of electrodes in the EUS and on the left pelvic nerve. EUS EMG recordings were obtained before and after drug treatments. Following the experiments, the area of the spinal transection was examined grossly after an extensive laminectomy was performed. In most of the chronic SCT experiments, it was obvious that the cord was completely sectioned because the rostral and caudal segments of the cord were completely disconnected. In some chronic SCT animals in which the region of the transection was obscured by scar tissue and Gelfoam, the cord was fixed in paraformaldehyde, sectioned on a cryostat, and the sections were Nissl stained. The histology revealed that the spinal cord was completely transected.

Drugs

Following the physiological studies, pharmacological experiments were conducted to examine the effects of serotonergic drugs on the CMG, EUS EMG, and the pelvic-EUS reflexes. 8-OH-DPAT (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and WAY100635 (Sigma) were dissolved in normal saline for intravenous administration. Drug doses were calculated for the base of each compound and selected based on results from previous experiments (2, 3, 14, 27). Single doses of 8-OH-DPAT (1 mg/kg) and WAY100635 (1 mg/kg) were administered intravenously. In most experiments, 8-OH-DPAT was administered 30 min before WAY100635. Electrophysiological recordings were obtained before and after drug administration.

Data Analysis

Asynchronous tonic and bursting EUS EMG activity and pelvic-EUS reflexes were rectified and measured by integrating the area under the curve (AUC) (mV-ms or μV-ms) with a personal computer (2, 3, 12, 24). The tonic and bursting EUS EMG activity were measured over the same length of time (1 s) in every experiment. In this paper, the AUC is termed the “reflex area.” The reflex area of the ER of pelvic-EUS reflex was measured over the duration of the reflex response, while the reflex area of the LR of pelvic-EUS reflex was measured over a period of 500 ms, starting from the first action potential. Compared with reflex amplitude, the reflex area was more consistent over long periods of recording and therefore more suitable for representing the intensity of reflex activity. The quantitative data in the paper represent the reflex area of the ER and LR. Twenty single-sweep recordings were analyzed and averaged to obtain each data point in the same animal. The results are given as means ± SE. The reflex areas obtained before and after bladder distension as well as before and after drug administration were evaluated statistically using Student’s t-test. The independent t-test was used to evaluate differences in results between two groups of animals. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Bladder and EUS Activity Evoked by Bladder Distension

Intact spinal cord

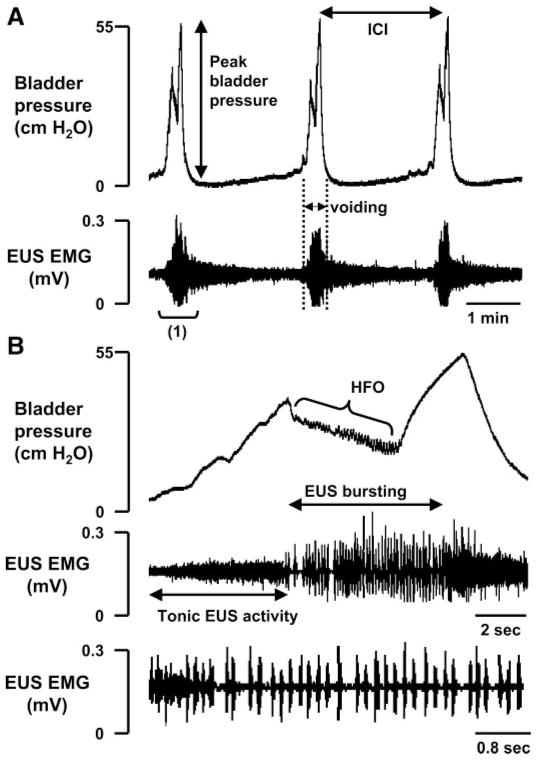

During continuous-infusion CMGs in intact-SC rats (n = 10) before the onset of voiding when the bladder was inactive, the EUS exhibited low-amplitude tonic activity. The tonic EUS activity increased in amplitude at the onset of micturition and then shifted to a large amplitude bursting pattern during voiding (Fig. 1). The average interval between reflex bladder voiding contractions [i.e., the intercontraction interval (ICI)] was 109.9 ± 10.1 s (Table 1) when the bladder was infused at a rate of 0.123 ml/min (Fig. 1A). During voiding, the CMGs showed a sudden increase in bladder pressure and then a decrease accompanied by high-frequency oscillations (HFOs) correlated with the EUS bursting activity (Fig. 1B). Following the period of HFOs, a second peak in bladder pressure (Table 1) occurred, accompanied by tonic EUS activity (Fig. 1B). Voiding is thought to occur during the period of EUS bursting and decreased bladder pressure. The EUS bursting consisted of high-frequency spikes occurring at a frequency of 6–8 Hz (15–17). In the present experiments, the average frequency of EUS bursting was 6.3 ± 1.1 Hz.

Fig. 1.

Bladder pressure (top traces) and external urethral sphincter (EUS) electromyography (EMG) activity (bottom traces) recorded in the rat with intact spinal cord. A: bladder pressure gradually increased during bladder filling at the rate of 0.123 ml/min. A large increase in bladder pressure, which indicates the start of micturition, was accompanied by large-amplitude EUS EMG activity. The bladder pressure consisted of a biphasic response: an initial rise in pressure followed by a decline and then a late secondary rise in pressure. The large-amplitude EUS EMG activity was followed by a prolonged after-discharge that continued for at least half of the intercontraction interval (ICI). B: record at a faster sweep of the time period indicated in A as “(1).” Before the onset of voiding when the bladder was inactive, the EUS exhibited tonic activity. At the beginning of the micturition reflex, tonic EUS activity increased and then converted to bursting activity as bladder pressure declined at the start of voiding. High-frequency oscillations (HFO) occurred in the bladder pressure recording during voiding. Bottom trace shows a fast sweep of the bursting period and conversion of tonic EUS activity to bursting activity at the beginning of voiding.

Table 1.

Drug effects on the frequency of reflex bladder contractions (intercontraction interval) and amplitude of bladder contractions (peak pressure) during cystometry in rats with intact-SC and in chronic T8 –9 SCT, L3– 4 SCT, or L6 –S1 SCT rats

| Intact-SC (n = 10) |

Chronic T8–9 SCT (n = 6) |

Chronic L3–4 SCT (n = 7) |

Chronic L6–S1 SCT (n = 5) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICIs, s | Peak Pressure, cmH2O | ICIs, s | Peak Pressure, cmH2O | ICIs, s | Peak Pressure, cmH2O | Peak Pressure, cmH2O | |

| Before drugs | 109.9±10.1 | 55.7±3.8 | 67.2±1.0§ | 44.8±2.2§ | 84.4±1.7‡§ | 35.1±2.7§ | 13.1±4.4§ |

| 8-OH-DPAT | 124.2±6.7 | 41.7±1.5* | 157.8±2.0* | 33.9±0.9* | 133.1±4.1* | 32.2±2.2 | 13.5±3.2§ |

| WAY100635 | 74.3±5.3* | 47.2±0.6*† | 77.2±1.0† | 39.3±1.3† | 93.1±1.9† | 32.4±1.7 | 13.1±1.8§ |

Values are mean values ± SE. ICIs, intracontraction intervals; SC, spinal cord; SCT, spinal cord transection. Bold values indicate 5 chronic T8-9 SCT rats were treated with drugs. ICIs were not measured in L6-S1 SCT animals because large-amplitude voiding contractions were absent in these animals.

P < 0.05, significantly changed compared with control before drugs.

P < 0.05, significantly changed compared with records after 8-OH-DPAT.

P < 0.05, significantly different compared with chronic T8–9 SCT rats prior to drugs.

P < 0.05, significantly reduced compared with intact-SC rats.

Twenty minutes after administration of 8-OH-DPAT, the ICI was not significantly changed (Table 1) but bladder pressure was significantly decreased (Table 1), and, as reported previously (1, 2), tonic and bursting EUS EMG activity were increased (Table 2). The subsequent administration of WAY100635 significantly decreased the ICI (Table 1), significantly increased bladder pressure (Table 1), and suppressed tonic and bursting EUS EMG activity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Drug effects on tonic and bursting EUS activity (area, mV-ms) during bladder filling or voiding in rats with intact-SC and chronic SCT at T8 –9 and L3– 4

| Intact-SC (n = 10) |

Chronic T8–9 SCT (n = 6) |

Chronic L3–4 SCT (n = 7) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tonic Activity During Filling | EUS Bursting During Voiding | Tonic Activity During Filling | EUS Activity During Voiding | Tonic Activity During Filling | Tonic Activity During Voiding | |

| Before drugs | 21.4±0.6 | 98.1±2.6 | 16.2±0.1 | 77.7±1.5(a) | 14.6±0.5 | 49.2±0.2 |

| 8-OH-DPAT | 43.7±1.2* | 165.4±4.1* | 36.1±1.1*(d) | 122.6±3.8* (b, d) | 37.4±0.9* | 119.4±2.6* |

| WAY100635 | 18.9±0.4† | 95.6±1.9† | 20.3±0.5† (d) | 88.7±7.3† (c, d) | 19.3±0.4† | 72.6±3.9*† |

Values are means ± SE. EUS, external urethral sphincter.

EUS tonic activity (n = 4) and EUS bursting activity (n = 2).

EUS bursting activity.

EUS tonic activity.

Drugs were tested in 5 of the chronic T8–9 SCT rats.

P < 0.05, significantly increased compared with control before drugs.

P < 0.05, significantly reduced compared with records after 8-OH-DPAT.

Acute SCT

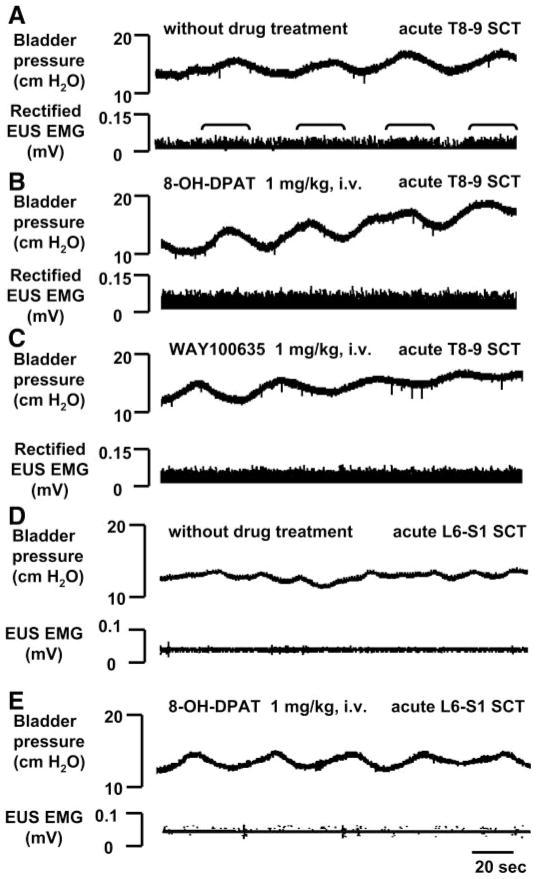

To determine the contribution of the brain and different segments of the spinal cord to the reflex activity of the EUS and bladder, we examined the changes in reflex activity after transection of the spinal cord at different segmental levels. Following acute T8–9 (n = 7, Fig. 2, A–C) or L3–4 (n = 7) spinal transection, large-amplitude bladder contractions were eliminated and only low-amplitude (12–20 cmH2O peak pressure) higher frequency (ICI 40–100 s) nonvoiding bladder contractions occurred. Tonic EUS activity persisted after cord transection, but EUS bursting was completely eliminated (Fig. 2A). Tonic EUS activity also increased during the small-amplitude bladder contractions, indicating that pathways in the spinal cord can generate a bladder-to-EUS reflex. 8-OH-DPAT and WAY100635 did not alter low-amplitude bladder activity. Tonic EUS activity was not significantly enhanced (Fig. 2B) by 8-OH-DPAT in acute T8–9 SCT rats. However, subsequent administration of WAY100635 significantly reduced (40–60%, n = 5) the firing (Fig. 2C). In acute L3–4 SCT rats, 8-OH-DPAT significantly increased tonic EUS activity by 15–28%. WAY100635 reversed the effect of 8-OH-DPAT.

Fig. 2.

Effects of serotonergic drugs on small-amplitude bladder contractions (top traces) and rectified tonic EUS EMG activity (bottom traces) in 2 rats after T8–9 (A–C) and L6–S1 (D and E) acute spinal cord transection (SCT). A: a small increase in tonic EUS activity occurred during bladder contractions (brackets), but EUS bursting activity did not occur. B: after 8-OH-DPAT, the amplitude of tonic EUS activity increased but bladder contractions did not significantly change. C: WAY100635 reduced the facilitatory effect of 8-OH-DPAT on tonic EUS activity. Neither 8-OH-DPAT nor WAY100635 affected small-amplitude bladder contractions. The interval between administration of 8-OH-DPAT and WAY100635 was 30 min. All records (A–C) were obtained in the same animal. D and E: acute L6–S1 SCT eliminated EUS EMG activity and the effects of 8-OH-DPAT.

To determine whether tonic EUS activity and drug effects were dependent on pathways in the lumbosacral spinal cord, the L6–S1 spinal cord was transected. In acute L6–S1 SCT rats (n = 4), both tonic and bursting EUS activity were abolished (Fig. 2D); however, low-amplitude nonvoiding bladder activity remained (15.2 ± 2.7 cmH2O). This activity was presumably mediated by nonneural mechanisms in the bladder smooth muscle. 8-OH-DPAT did not alter bladder activity or unmask EUS EMG activity in these animals (Fig. 2E).

Chronic spinal cord injury

Immediately after SCT, spontaneous release of urine was abolished in all animals; thus it was necessary to manually express the bladders. Large volumes of urine were expressed from the bladder during the first few days after SCT, but in T8–9 and L3–4 SCT rats the volumes decreased when spontaneous micturition was reestablished after ~1 wk (4, 5, 16). However, in L6–S1 SCT rats, spontaneous micturition did not recover and large volumes of urine were expressed from the bladder during the entire post-SCT period.

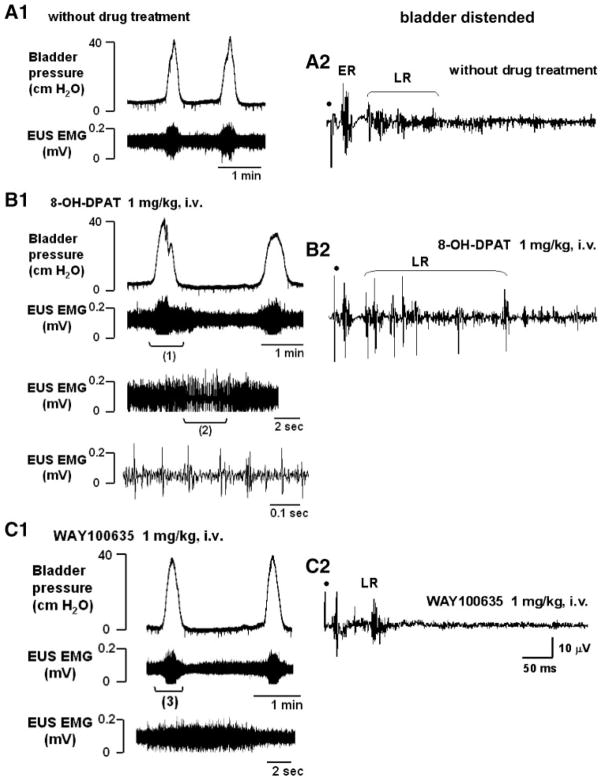

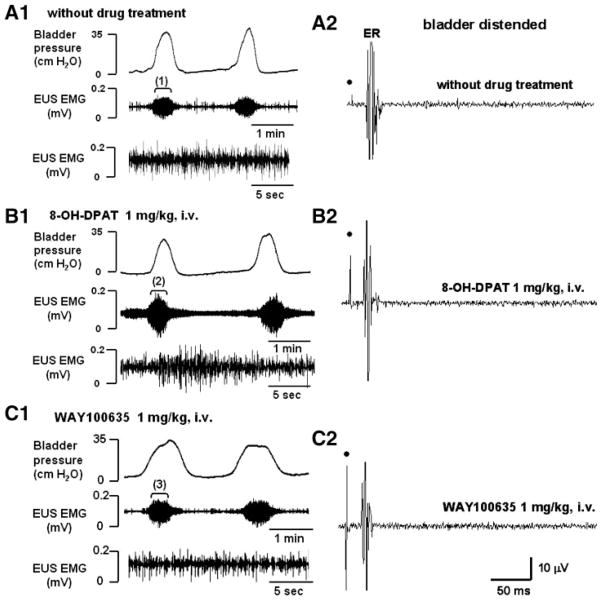

In chronic SCT rats 2–5 wk after spinal cord transection, bladder and EUS EMG activity were markedly different in the three groups of animals transected at different segmental levels. The ICIs during continuous-infusion CMGs in animals transected at T8–9 was significantly shorter (Table 1 and Fig. 3A1) than the ICIs in animals transected at L3–4 (Table 1 and Fig. 4A1) or in intact-SC animals. The peak intravesical pressures during voiding (Table 1) were 44.8 ± 2.2 cmH2O in chronic T8–9 SCT rats and 35.1 ± 2.7 cmH2O in chronic L3–4 SCT rats. These values were significantly lower than those in spinal-intact rats. In four of six chronic T8–9 SCT rats and all chronic L3–4 SCT rats, tonic EUS activity remained but EUS bursting was abolished during bladder filling. However, two animals at 5 wk after T8–9 SCT exhibited EUS bursting during voiding.

Fig. 3.

Effects of serotonergic drugs on the bladder (top left traces), EUS EMG activity (bottom left traces), and pelvic-EUS reflex (right traces) in a rat with T8–9 chronic SCT (4 wk). A1: before drug treatment, the bladder exhibited rhythmic, large-amplitude micturition contractions during bladder filling. During the bladder contractions, the low-amplitude tonic EUS activity was enhanced but EUS bursting did not occur. A2: early response (ER) and a small-amplitude late response (LR) in the pelvic-EUS reflex was present when the bladder was distended. B1: 8-OH-DPAT increased the tonic EUS activity and unmasked EUS bursting during voiding. Trace 3 shows a fast sweep of EUS EMG activity during period (1) that included the bursting. Trace 4 shows a faster sweep of the EUS bursting during period (2) in trace 3. B2: after 8-OH-DPAT, the LR was markedly increased. C1: WAY100635 reversed the effect of 8-OH-DPAT. The large-amplitude tonic activity was reduced and the EUS bursting during voiding was eliminated. Trace 3 is a fast sweep of the period (3) showing that EUS bursting was eliminated by WAY100635, leaving only tonic EUS activity when the bladder pressure increased during a micturition reflex. C2: after WAY100635 the burst firing of the LR was suppressed. Dot, electrical stimulation (4 V, 1.0 Hz, pulse width 0.05 ms). All traces (A2–C2) represent a recording of a single reflex response.

Fig. 4.

Effects of serotonergic drugs on the bladder (top left traces), EUS EMG activity (bottom left traces), and pelvic-EUS reflex (right traces) in a rat with chronic L3–4 SCT during bladder filling and repeated voiding. A1, B1, C1: in each record, EUS EMG activity is shown at a slow time base (middle trace) and an expanded time base (bottom trace) of the sequence of recording indicated by the brackets (1, 2, 3) in the middle traces. A1: before drug treatment, the bladder exhibited rhythmic micturition contractions during bladder filling. At the peak of the contractions, tonic EUS activity was markedly enhanced. EUS bursting activity did not occur. B1: 8-OH-DPAT enhanced tonic EUS activity but did not unmask EUS bursting. C1: WAY100635 reversed the effect of 8-OH-DPAT on tonic EUS activity. A2–C2: the ER remained, but the LR was absent in the chronic L3–4 SCT rat. The ER was not affected by drugs. Dot, electrical stimulation (6 V, 1.0 Hz, pulse width 0.05 ms).

In chronic L6-S1 SCT rats, both tonic and bursting EUS activity and large-amplitude bladder contractions were abolished. The peak intravesical pressures during the small-amplitude nonvoiding bladder contractions were significantly lower than the values in intact-SC rats and chronic T8–9 and L3–4 SCT rats.

In chronic T8–9 SCT rats during continuous-infusion CMGs, 8-OH-DPAT significantly increased the ICIs by 134% compared with the values of ICIs before drug treatment (Table 1). 8-OH-DPAT also significantly decreased the peak bladder pressure by 24% (Table 1) and facilitated tonic EUS activity (122% increase in area) as well as EUS bursting (57% increase in area) (Table 2). 8-OH-DPAT also unmasked bursting in animals (n = 4) when it was not evoked by bladder distension alone. During voiding in 8-OH-DPAT-treated rats, tonic EUS activity shifted to EUS bursting (Fig. 3B1). The frequency of EUS bursting was 4–6 Hz. The subsequent administration of WAY100635 reversed the effect of 8-OH-DPAT, significantly decreasing the ICIs by 51% and increasing peak bladder pressure by 15% (Table 1). WAY100635 decreased the area of tonic EUS activity by 43% (Table 2) during bladder filling and completely suppressed EUS bursting during voiding (Fig. 3C1).

In chronic L3–4 SCT rats, the ICIs during continuous-infusion CMGs were significantly increased by 57% after 8-OH-DPAT (Table 1). However, neither 8-OH-DPAT nor WAY100635 produced significant changes in the peak bladder pressure during voiding (Table 1). 8-OH-DPAT significantly increased the tonic EUS activity by 156% (Fig. 4B1 and Table 2) but did not unmask EUS bursting during voiding. WAY100635 partially reversed the effect of 8-OH-DPAT, significantly decreasing the ICIs by 30% (Table 1), decreasing the area of tonic EUS activity by 48% during bladder filling, and decreasing the area of tonic EUS activity by 39% during voiding (Fig. 4C1 and Table 2).

In chronic L6-S1 SCT rats, 8-OH-DPAT did not change bladder activity or unmask EUS EMG activity.

EUS Activity Elicited by Electrical Stimulation of the Pelvic Nerve

Intact spinal cord

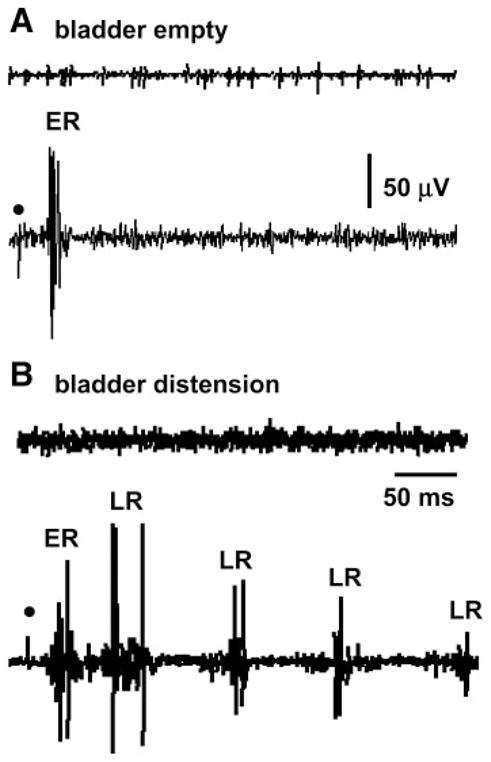

When the bladder was distended, the EUS activity evoked by electrical stimulation of the pelvic nerve in intact-SC rats consisted of a large-amplitude, short-latency (18.3 ± 0.5 ms), short-duration (15.7 ± 1.4 ms) ER and a long-latency (average 104.8 ± 3.5 ms), long-duration (>100 ms) LR (Fig. 5). When the bladder was empty, only the ER was detected in every recording and the LR occurred inconsistently in 20% of recordings. The ER was not significantly changed by bladder distention.

Fig. 5.

Pelvic-EUS reflex was enhanced by bladder distension in a rat with an intact spinal cord. A: top trace shows the EUS-EMG activity without electrical stimulation. Bottom trace shows the pelvic-EUS reflex elicited by a single shock to the pelvic nerve (dot) when the bladder was empty. Reflex responses consisted of a large ER. B: top trace shows the EUS-EMG activity without electrical stimulation when the bladder was distended by 0.2 ml of saline. Bottom trace shows that the LR of pelvic-EUS reflex was unmasked but the ER was not changed by bladder distension. All traces were obtained in the same animal and represent a recording of a single reflex response. Dot, 4 V, 0.1 Hz, pulse width 0.05 ms.

When the bladder was empty, 8-OH-DPAT did not significantly enhance the ER. However, when the bladder was distended (0.2 ml of saline) 8-OH-DPAT significantly increased the areas of ER and LR by 18 ± 0.1 and 85 ± 0.9%, respectively (n = 10). Subsequent administration of WAY100635 20–30 min after 8-OH-DPAT decreased the areas of ER and LR by 58 ± 0.7 and 65 ± 0.4% (n = 8), respectively.

Acute SCT

When the bladder was distended or empty in acute T8–9 (n = 7) and L3–4 (n = 7) SCT rats, electrical stimulation of the pelvic nerve elicited an ER at a latency that was not significantly different (average 17.8 ± 0.2 ms) from that in intact-SC rats. When the bladder was distended, the LR, was absent in acute T8–9 and L3–4 SCT rats. In acute L6-S1 SCT rats (n = 4), neither an ER nor an LR was detected.

In acute T8–9 SCT rats, 8-OH-DPAT did not significantly change the area of ER but unmasked a small LR (latency, 84.2 ± 5.1 ms) in two of seven rats. The area of the LR after 8-OH-DPAT and during bladder distention was 20 ± 9.1% (n = 2) of the average area in intact-SC rats. In these two experiments when the bladder was distended, WAY100635 reduced by 74 ± 10.6% (n = 2) the facilitatory effect of 8-OH-DPAT. In another five rats when the bladder was distended, neither 8-OH-DPAT nor WAY100635 significantly changed the areas of the ER and LR.

In acute L3–4 SCT rats when the bladder was distended, 8-OH-DPAT (n = 5) produced a small, but statistically significant increase in the area of ER (16 ± 0.3% increase) but did not unmask an LR. WAY100635 completely reversed the effect of 8-OH-DPAT. In acute L6-S1 SCT rats (n = 4), 8-OH-DPAT did not unmask an ER or an LR.

Chronic spinal cord injury

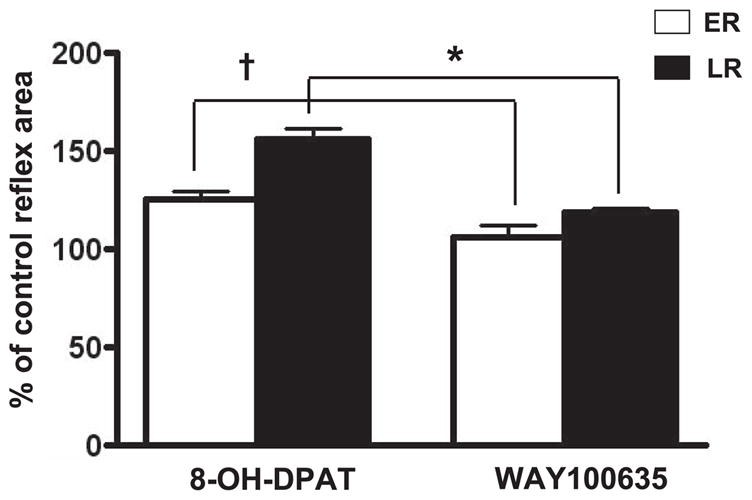

In chronic T8–9 SCT rats (Fig. 3A2), the pelvic-EUS reflex consisted of the ER and LR when the bladder was distended but only an ER when the bladder was empty. The latency and duration of ER in chronic T8–9 SCT rats (n = 6) were not significantly different from values in intact-SC rats. However, the latency of the LR (62 ± 4.1 ms) was shorter than that in intact-SC rats (average 104.8 ± 3.5 ms). When the bladder was distended, 8-OH-DPAT (n = 5) increased the areas of the ER and LR by 26 and 56%, respectively (Figs. 3B2 and 6). WAY100635 reversed the effect of 8-OH-DPAT (n = 5), significantly suppressing the areas of ER and LR by 18 and 38%, respectively (Figs. 3C2 and 6). The latencies of ER and LR were not significantly changed after drug treatments.

Fig. 6.

Area of the pelvic-EUS ER and LR reflexes in chronic T8–9 SCT rats when the bladder was distended. The ER and LR were significantly enhanced 26 (P < 0.05) and 56% (P < 0.05), respectively, by 8-OH-DPAT (n = 5). WAY100635 (n = 5) significantly decreased ER and LR by 18 and 38%, respectively, after 8-OH-DPAT. *, †: P < 0.05, significantly decreased compared with records after 8-OH-DPAT.

In chronic L3–4 SCT rats (n = 7, Fig. 4A2), the ER remained, but the LR was absent when the bladder was empty or distended. The area of ER in chronic L3–4 SCT rats was 31 ± 2.7% larger than the area of ER in chronic T8–9 SCT rats. Neither 8-OH-DPAT (Fig. 4B2) nor WAY100635 (Fig. 4C2) elicited significant changes in the ER.

In chronic L6-S1 SCT rats (n = 5), in which the ER and LR were absent, neither bladder distension nor drugs unmasked reflex responses.

DISCUSSION

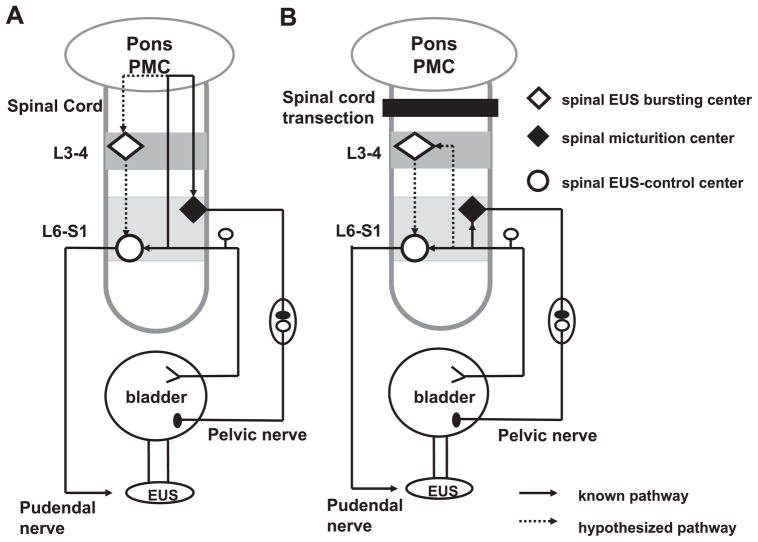

The present study examined the effect of acute and chronic SCT at different segmental levels on 1) reflex activity of the bladder and EUS and 2) the effects of 5-HT1A receptor agonists and antagonists on the bladder and EUS reflexes. The results indicate that tonic and bursting EUS activity are mediated by distinct spinal reflex pathways that are organized at different segmental levels (Fig. 7). The properties of tonic and bursting EUS activity were similar, respectively, to those of the ER and LR of the pelvic-EUS reflexes. This raises the possibility that a common reflex mechanism mediates the ER and tonic EUS activity (termed type 1 responses for the purpose of this discussion) and another mediates the LR and EUS bursting (termed type 2 responses). It seems likely that these two types of EUS responses contribute to different LUT functions.

Fig. 7.

Diagram showing putative reflex pathways mediating reflex micturition and tonic and bursting EUS activity in spinal cord-intact (A) and chronic SCT T8–9 rats (B). A: spinobulbospinal micturition reflex pathway is shown by the solid line passing through the pontine micturition center (PMC) in the rostral brain stem. The hypothesized pathway mediating EUS bursting is shown by the dotted line also passing through the PMC. In spinal cord-intact rats, when the bladder is distended, afferent input from bladder mechanoreceptors passes via the pelvic nerve to the L6–S1 spinal cord to the spinal EUS-control center to generate tonic EUS activity and the ER. Input from the L6–S1 spinal cord passes to the PMC, which then projects to the lumbosacral micturition center to generate reflex bladder contractions and to L3–4 bursting center to generate EUS bursting. The spinal EUS bursting center provides an excitatory input to the spinal EUS-control center to initiate an excitatory outflow to the EUS. The spinal EUS-control center in the L6–S1 spinal cord consists of interneuronal and motoneuronal circuitry that regulates EUS activity. B: after SCT, descending input from the PMC to spinal centers is interrupted. This initially eliminates the micturition reflex, the LR, and EUS bursting. The ER and tonic EUS activity mediated by a spinal reflex pathway are preserved. However, in chronic SCT rats it is hypothesized that reorganization of synaptic connections in the spinal cord leads to the reemergence of the micturition reflex as well as the LR and EUS bursting. This reorganization depends on the formation of new pathways between pelvic primary afferent nerves and the L3–4 spinal EUS bursting center (dotted line) and spinal micturition center (solid line) or upregulation of pathways that exist in the spinal intact animals.

The conclusion that type 1 and type 2 responses are mediated by distinct spinal pathways is based on the effect of SCT at three segmental levels. Both responses were eliminated by acute or chronic L6-S1 SCT. This is attributable to interruption of the motor innervation of the EUS as well as the pelvic afferent input that projects to the L6–S1 spinal cord. Acute or chronic L3–4 SCT that preserves the afferent and efferent limbs of the pelvic-EUS reflex pathway did not suppress type 1 responses that are organized at L6–S1. However, injury at L3–4 abolished type 2 responses, indicating that pathways at or rostral to this level were essential for the generation of type 2 responses. Because type 2 responses were eliminated by acute T8–9 SCT but recovered after chronic T8–9 SCT, it seems reasonable to conclude that type 2 responses are normally dependent on supraspinal pathways (Fig. 7A) but can reemerge after elimination of those pathways in chronic SCT rats when circuitry between T9 and L4 is preserved.

Although the mechanisms underlying the recovery of type 2 responses after T8–9 SCT are uncertain, it is noteworthy that the latency of the LR was significantly shorter (62 ms) in chronic T8–9 SCT rats than in intact-SC rats (105 ms). This raises the possibility that neuroplasticity involving the reorganization of synaptic connections in the spinal cord is responsible for the recovery of type 2 responses. Similar mechanisms seem to be responsible for the recovery of reflex bladder activity after SCT (8, 9).

Previous studies revealed that the micturition reflex in intact-SC rats is mediated by a long-latency (120 ms) spinobulbospinal reflex pathway passing through a coordination center in the rostral pons (8, 19). The estimated long central delay for the micturition reflex (~60 ms) is similar to the estimated central delay for the LR (90 ms, based on a 105-ms reflex latency minus 15 ms for peripheral afferent and efferent conduction times). Thus the LR, like the micturition reflex, may be mediated by a spinobulbospinal pathway in intact-SC rats (Fig. 7A).

In chronic SCT rats, the central delay for the micturition reflex is dramatically shortened from 60 ms to <5 ms (19), while the central delay for the LR is also shortened but is still considerably longer (47 ms, based on 62-ms reflex latency minus 15 ms for peripheral conduction time) than that of the micturition reflex. The difference in central delays between the LR and the micturition reflex may reflect differences in the spinal pathways. Micturition occurs via a segmental pathway at L6–S1, while the LR seems to be dependent on a more complex intersegmental pathway involving L6–S1 and more rostral lumbar segments (Fig. 7B). This difference in the organization of the two reflex mechanisms is supported by the finding that large-amplitude bladder contractions and voiding persist in chronic L3–4 SCT rats, whereas type 2 responses were eliminated in these animals. The presence of PRV-labeled neurons in the rostral lumbar spinal cord after injection of PRV into the EUS (21) is consistent with the idea that circuitry in this region of the spinal cord is involved in EUS function.

On the other hand, the ER must be mediated via a spinal segmental pathway in L6–S1 because it survives after L3–4 SCT. The ER also has a short central delay (3–4 ms) (1), comparable to that of the spinal micturition reflex. Similarly, EUS reflex activity and reflexes in pudendal nerve motor axons elicited by electrical stimulation of afferent axons in the pudendal nerve (i.e., the pudendal-EUS reflex) also occur after a short central delay (4.5–8.5 ms) (3, 23). Thus the long central delay of the spinal LR stands in marked contrast to the short central delays of other spinal reflexes involved in LUT function. This is consistent with the view that the LR is mediated by more complex intersegmental circuitry.

The relationship between bladder activity and the ER-LR EUS reflexes indicates that these two types of EUS reflexes have different functions. Although the ER was enhanced by activation of mechanosensitive bladder afferents during bladder distension, it could also be elicited by electrical stimulation of the pelvic nerve in the absence of bladder distension. The LR was usually absent or very weak under empty bladder conditions but was unmasked or markedly facilitated by bladder distension. The facilitated LR consisted of prominent bursts of firing lasting for hundreds of milliseconds and occurring at intervals similar to the intervals of EUS bursting during voiding. Thus the LR very likely represents a transient activation of the EUS pattern generator that mediates rhythmic contractions and relaxations of the EUS during voiding. A similar pattern generator in the lumbar spinal cord may be responsible for the bursting activity of periurethral striated muscles that occurs during ejaculation in the male rat (29). The presence of an ER under empty bladder conditions or during bladder filling before micturition suggests that the ER is related to continence mechanisms and most likely is responsible for tonic EUS activity occurring before voiding.

Activation of 5-HT1A receptors in the central nervous system (CNS) with 8-OH-DPAT is known to facilitate reflex micturition (18); thus it was not surprising that 8-OH-DPAT also facilitated the LR that is linked with voiding. The facilitatory effect of 8-OH-DPAT on LR is attributable to an action in the spinal cord because it occurred in chronic T8–9 SCT rats. 8-OH-DPAT also induced EUS bursting in response to bladder distension and facilitated bladder emptying in chronic SCT rats (11). It is possible that an additional facilitatory effect on the brain might contribute to enhancement of the LR in intact-SC animals; however, this was not explored.

Previous studies in intact-SC rats revealed that WAY100635 alone, a 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, not only reversed the facilitatory effect of 8-OH-DPAT but also suppressed reflex bladder activity (14, 25) and EUS bursting induced by bladder distension (1). This indicates that EUS bursting is tonically facilitated by an endogenous serotonergic mechanism in anesthetized animals with an intact neuraxis. Thus the interruption of bulbospinal serotonergic pathways might contribute to the elimination of type 2 responses after acute T8–9 SCT. However, other mechanisms must also contribute to the effect of acute SCT because 8-OH-DPAT produced only a partial recovery of the LR in these preparations. 8-OH-DPAT also facilitated type 1 responses in intact-SC rats as well as in acute-and chronic-SCT rats. This effect occurred in T8–9 and L3–4 SCT rats, indicating that the effect was mediated by an action on the L6–S1 spinal cord, whereas the facilitatory effect on type 2 responses was eliminated in L3–4 SCT rats. The serotonergic drugs could act at multiple sites because 5-HT1A receptors are widely distributed in the dorsal horn and dorsal gray commissure of the rat spinal cord (28). We conclude that the facilitatory effect of 5-HT1A receptor activation on type 2 responses may be related to an action on the spinal pathways rostral to L4, whereas the facilitatory effect on type 1 responses may be mediated by effects on the spinal pathways in L6–S1 segments.

The facilitatory effect of 8-OH-DPAT on type 1 and type 2 responses indicates that serotonergic mechanisms can modulate the two opposing functions of the LUT: urine storage and voiding. This apparent paradoxical effect is not unprecedented because α1-adrenergic mechanisms (30) and muscarinic mechanisms in the CNS (13) have also been shown to facilitate continence and voiding mechanisms. Interest in the role of serotonin in the control of the urethral sphincter has been stimulated by recent reports that duloxetine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is useful for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (10). Duloxetine is thought to act by enhancing monoaminergic facilitation of the spinal pathways controlling the EUS (7, 26). More information about the mechanisms underlying serotonergic control of EUS activity may provide new insights into the pathophysiology of urinary incontinence and lead to more effective treatments.

Acknowledgments

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant NIDDK-49430 to W. C. de Groat and National Science Council Grants NSC-93–2213-E-075A-002 and NSC 93–2213-E-006–117 in Taiwan to C. L. Cheng and J. J. Chen, respectively.

References

- 1.Chang HY, Cheng CL, Chen JJ, de Groat WC. Abstract Viewer (Online). Program No. 541.13. Society for Neuroscience; 2004. Role of glutamatergic and serotonergic mechanisms in urethral sphincter reflexes in urethane-anesthetized rats. http://www.sfn.org. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang HY, Cheng CL, Chen JJ, Negoita FA, de Groat WC. Abstract Viewer (Online). Program No. 48.17. Society for Neuroscience; 2005. Influence of serotonergic mechanisms in the spinal cord on external urethral sphincter function during voiding. http://www.sfn.org. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang HY, Cheng CL, Peng CW, Chen JJ, de Groat WC. Reflexes evoked by electrical stimulation of afferent axons in the pudendal nerve under empty and distended bladder conditions in urethane-anesthetized rats. Neurosci Meth. 2006;150:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng CL, de Groat WC. The role of capsaicin-sensitive afferent fibers in the lower urinary tract dysfunction induced by chronic spinal cord injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng CL, Ma CP, de Groat WC. Effect of capsaicin on micturition and associated reflexes in chronic spinal rats. Brain Res. 1995;678:40–48. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coolen LM, Allard J, Truitt WA, McKenna KE. Central regulation of ejaculation. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Groat WC. Influence of central serotonergic mechanisms on lower urinary tract function. Urology. 2002;59:30–36. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01636-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Groat WC, Booth AM, Yoshimura N. Neurophysiology of micturition and its modification in animal models of human disease. In: Maggi CA, editor. The Autonomic Nervous System: Nervous Control of the Urogenital System. London, UK: Harwood; 1993. pp. 247–289. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Mechanisms underlying the recovery of lower urinary tract function following spinal cord injury. Progr Brain Res. 2005;152:59–84. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)52005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dmochowski RR, Miklos JR, Norton PA, Zinner NR, Yalcin I, Bump RC Duloxetine Urinary Incontinence Study Group. Duloxetine versus placebo for the treatment of North American women with stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2003;170:1259–1263. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000080708.87092.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolber PC, Gu C, Fraser MO, Thor KB. Abstract Viewer. Program No. 608.16. Society for Neuroscience; 2003. Relief of bladder-sphincter dyssynergia by a 5HT1A serotonin receptor agonist in rats with chronic spinal cord injury. http://www.sfn.org. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes GM, Rogers RC, Bresnahan JC, Beattie MS. External anal sphincter hyperreflexia following spinal transection in the rat. J Neurotrauma. 1998;15:451–457. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishiura Y, Yoshiyama M, Yokoyama O, Namiki M, de Groat WC. Central muscarinic mechanisms regulating voiding in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:933–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakizaki H, Yoshiyama M, Koyanagi T, de Groat WC. Effects of WAY100635, a selective 5-HT1A-receptor antagonist on the micturition-reflex pathway in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R1407–R1413. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.5.R1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruse MN, Belton AL, de Groat WC. Changes in bladder and external urethral sphincter function after spinal cord injury in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1993;264:R1157–R1163. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.6.R1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruse MN, de Groat WC. Spinal pathways mediate coordinated bladder urethral sphincter activity during reflex micturition in decerebrate and spinalized neonatal rats. Neurosci Lett. 1993;152:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90503-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruse MN, Noto H, Roppolo JR, de Groat WC. Pontine control of the urinary bladder and external urethral sphincter in the rat. Brain Res. 1990;532:182–190. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91758-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lecci A, Giuliani S, Santicioli P, Maggi CA. Involvement of 5-hydroxy-tryptamine 1A receptors in the modulation of micturition reflexes in the anesthetized rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:181–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mallory B, Steers WD, de Groat WC. Electrophysiological study of micturition reflexes in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1989;257:R410–R421. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.2.R410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maggi CA, Giuliani S, Santicioli P, Meli A. Analysis of factors involved in determining urinary bladder voiding cycle in urethananesthetized rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1986;251:R250–R257. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.251.2.R250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marson L. Identification of central nervous system neurons that innervate the bladder body, bladder base, or external urethral sphincter of female rats: a transneuronal tracing study using pseudorabies virus. J Comp Neurol. 1997;389:584–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenna KE, Chung SK, McVary KT. A model for the study of sexual function in anesthetized male and female rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1991;261:R1276–R1285. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.5.R1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKenna KE, Nadelhaft I. The pudendo-pudendal reflex in male and female rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1989;27:67–77. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(89)90130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stalberg E, Andreassen S, Falck B, Lang H, Rosenfalck A, Trojaborg W. Quantitative analysis of individual motor unit potentials: a proposition for standardized terminology and criteria for measurement. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1986;3:313–348. doi: 10.1097/00004691-198610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Testa R, Guarneri L, Poggesi E, Angelico P, Velasco C, Ibba M, Cilia A, Motta G, Riva C, Leonardi A. Effect of several 5-hydroxytrypt-amine1A receptor ligands on the micturition reflex in rats: comparison with WAY100635. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:1258–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thor KB, Katofiasc MA. Effects of duloxetine, a combined serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, on central neural control of lower urinary tract function in the chloralose-anesthetized female cat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1014–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thor KB, Katofiasc MA, Danuser H, Springer J, Schaus JM. The role of 5-HT1A receptors in control of lower urinary tract function in cats. Brain Res. 2002;946:290–297. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02897-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thor KB, Nickolaus S, Helke CJ. Autoradiographic localization of 5-hydroxytryptamine1A, 5-hydroxytryptamine 1B and 5-hydroxytryptamine 1C/2 binding sites in the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1993;55:235–252. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90469-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Truitt WA, Coolen LM. Identification of a potential ejaculation generator in the spinal cord. Science. 2002;297:1566–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.1073885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshiyama M, Yamamoto T, de Groat WC. Role of spinal alpha(1)-adrenergic mechanisms in the control of lower urinary tract in the rat. Brain Res. 2002;882:36–44. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02688-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshiyama M, de Groat WC, Fraser MO. Influences of external urethral sphincter relaxation induced by alpha-bungarotoxin, a neuromuscular junction blocking agent, on voiding dysfunction in the rat with spinal cord injury. Urology. 2000;55:956–960. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00474-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]