Abstract

Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 converts sugars and various polysaccharides into acids and solvents. This bacterium, however, is unable to utilize cellulosic substrates, since it is able to secrete very small amounts of cellulosomes. To promote the utilization of crystalline cellulose, the strategy we chose aims at producing heterologous minicellulosomes, containing two different cellulases bound to a miniscaffoldin, in C. acetobutylicum. A first step toward this goal describes the production of miniCipC1, a truncated form of CipC from Clostridium cellulolyticum, and the hybrid scaffoldin Scaf 3, which bears an additional cohesin domain derived from CipA from Clostridium thermocellum. Both proteins were correctly matured and secreted in the medium, and their various domains were found to be functional.

Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 is one of the best-known solventogenic bacteria that convert sugars and various polysaccharides into acids and solvents (4, 5, 11, 13, 15, 27, 28). Unfortunately, this bacterium is unable to grow on crystalline cellulose, although its genome contains a large cluster of genes involved in the cellulolysis process (15, 23). This cluster starts with the cipA gene encoding the scaffoldin CipA, followed by eight genes encoding mostly glycosylhydrolases derived from GH families 48, 9, and 5. C. acetobutylicum secretes very small quantities of a cellulosome of ∼665 kDa devoid of activity on crystalline cellulose and possessing very low activity on carboxymethyl cellulose or phosphoric-acid-swollen cellulose (22, 23). Recently, the gene encoding a truncated CipA was overexpressed in the bacterium, leading to the formation of a minicellulosome in C. acetobutylicum (24). As with normal cellulosome, this recombinant minicellulosome was found to be inactive against crystalline cellulose. The reasons for these cellulosomes being so poorly produced are not yet clearly established. Since C. acetobutylicum grows very well on cellobiose, it may be possible to engineer the bacterium to grow on cellulose by introducing cellulases from another cellulolytic bacterium. The mesophilic Clostridium cellulolyticum was chosen as the donor for cel genes. This bacterium produces a cellulosome of ∼700 kDa which efficiently degrades crystalline cellulose (1, 6). Almost all cel genes are clustered on a 26-kb fragment including cipC, coding for the scaffoldin CipC (18). Several components of the cellulosome have been extensively studied from the biochemical and structural points of view (1, 7, 12, 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 26). The dockerin domains of the cellulases interact closely with the cohesin domains of the scaffoldin (16), and it has been demonstrated that the cohesins of CipC recognize all the dockerin-containing enzymes from C. cellulolyticum (18). On the other hand, recognition between the cohesins and dockerins of the two clostridial species C. cellulolyticum and the thermophilic Clostridium thermocellum was shown to be species specific (17). Based on these observations, chimeric miniscaffoldins containing a cohesin from each species have been built by Fierobe et al. (2, 3). These chimeric proteins allowed the in vitro reconstitution of minicellulosomes containing two different cellulases, one possessing a C. cellulolyticum dockerin (cellulasec) and the other harboring a C. thermocellum dockerin (cellulaset). It was shown that the binding of various enzyme pairs on the hybrid scaffoldins induced a significant increase in activity toward crystalline cellulose, especially when the hybrid scaffoldin contained a cellular binding module (CBM). Our goal is thus to produce in C. acetobutylicum the most efficient minicellulosomes containing a chimeric scaffoldin and two selected enzymes.

In this study, we describe the production in C. acetobutylicum of two heterologous miniscaffoldins: miniCipC1 containing CBM3a, one X2 module, and the cohesin 1 module of CipC of C. cellulolyticum, and the chimeric Scaf3, in which the cohesin 3 module of the scaffoldin CipA of C. thermocellum was fused with the C-terminal region of miniCipC1.

Cloning of cipC1 in C. acetobutylicum.

The DNA fragment coding for miniCipC1, including the signal peptide, was amplified from C. cellulolyticum genomic DNA using the primers cipC1D and cipC1R (Table 1). The internal BamHI site of the fragment was suppressed by PCR using the primers MutB-D and MutB-R. This fragment was introduced between the BamHI and NarI sites of the pSOS95 shuttle vector (kindly provided by P. Soucaille, INSA, Toulouse, France) under the control of the strong constitutive promoter of the C. acetobutylicum thiolase gene (thl). The transcriptional terminator used was that of the acetoacetate decarboxylase gene (adc). Unfortunately, no Escherichia coli transformant colony was obtained. It was hypothesized that the thl promoter was recognized by the E. coli transcription machinery and that the production of miniCipC1 would disrupt the secretion machinery, leading to cell death. This hypothesis was confirmed by the cloning of the gene encoding the mature form of miniCipC1 using the same vector. Intracellular overproduction of the protein was observed in E. coli DH5α (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Name | Sequence (5′ → 3′)a | Localization | Underlined sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| SosA | TCCTGCAGGTCGACTTTTTAACAA | thl promoter | SalI restriction site |

| SosB | ATTGTTATCCGCTCACAATTCAACTTAATTATACCCACTATTATTATTTT | lac operator 1 | |

| SosD | ATTGTGAGCGGATAACAATTTTAGAGAAAACGTATAAATTAGGGATAAACTATGGA | lac operator 1 | |

| SosE | TAAATTCTGGATCCTACGGGGTAACAGA | thl promoter | BamHI restriction site |

| LacD2 | TCGATCTAGAAATTGTGAGCGGATAACAATTAAAGCTCCTGCAGG | lac operator 2 | SalI extension |

| LacR2 | TCGACCTGCAGGAGCTTTAATTGTTATCCGCTCACAATTTCTAGA | lac operator 2 | SalI extension |

| CipC1D | GGGGATCCAGAATTTAAAAGGAGGGATTAAAATGCGTAAAAAGTCTTTAGCA | cipC1 | BamHI restriction site |

| CipC1R | TTCCGGCGCCTTATACTGCTACTTTAAGTTCCTTTG | cipC1 | NarI restriction site |

| MutB-D | CAGCTGGAGGTTCCATAGAGAT | BamHI mutation in cipC1 | |

| MutB-R | ATCTCTATGGAACCTCCAGCTG | BamHI mutation in cipC1 | |

| rMC1SOS1 | GGTGGGGGATCCTTCGAACTACTCGAGTTCCTTTGTAGGTTGAGTACC | Used for construction of scaf3 | BamHI, AsuII, XhoI restriction sites |

lac operator sequences are italicized; stop codons are in boldface.

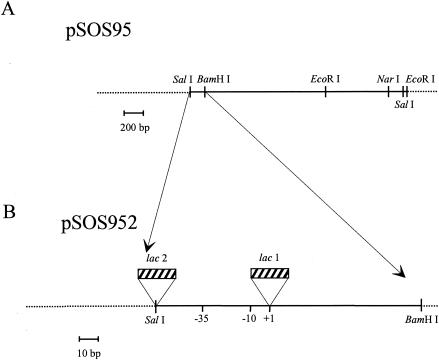

The promoter region of the pSOS95 vector was therefore modified by adding two lac operators (21 bp each) immediately upstream and downstream of the thiolase promoter region, which thus remained intact, in the pSOS952 plasmid (Fig. 1B). The primers used are listed in Table 1. The first lac operator was generated by three PCR steps, using pSOS95 as the matrix. The first step generated an 86-bp fragment, using the forward primer SosA and the reverse primer SosB. The second step generated a 111-bp PCR fragment, using the forward primer SosD and the reverse primer SosE. The entire fragment (178 bp) containing the lac operator was amplified by PCR from a mixture of both overlapping fragments by using the external primers SosA and SosE. After double digestion with SalI and BamHI, the lac operator 1 fragment was subsequently ligated into a similarly digested vector pSOS95, resulting in the vector pSOS95m. The second lac operator was inserted into the pSOS95m plasmid at the SalI restriction site. The DNA fragment was obtained by simple hybridization of oligonucleotides LacD2 and LacR2.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the cloning region of pSOS95 (A) and position of the two lac operators inserted upstream and downstream of the thiolase of the promoter region (B) to construct the pSOS952 derivatives.

E. coli SG-13009, containing the pREP4 repressor plasmid, was used as the recipient strain for the resulting pSOS952 plasmid and its recombinant forms. The DNA fragment coding for miniCipC1 with the signal peptide was cloned successfully using pSOS952. The resulting pSOS952-cipC1 plasmid was methylated in vivo in E. coli ER 2275 carrying the pAN1 methylating plasmid (10) and was used to transform C. acetobutylicum by electrotransformation (14).

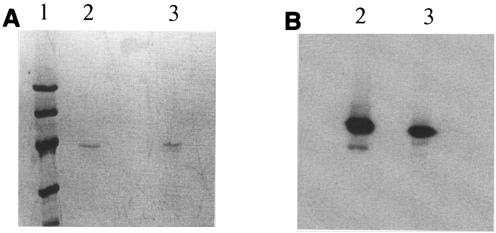

One clone was selected to inoculate 2YT medium (containing, per liter, 16 g of tryptone, 10 g of yeast extract, and 5 g of NaCl) supplemented with cellobiose (5 g/liter) and erythromycin (40 μg/ml). After growth overnight, the cells were harvested and the supernatant was adjusted to pH 6.5 with 1 M phosphate buffer and loaded onto an Avicel (Fluka PH 101) column equilibrated with 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5. After two washes with 50 and 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, respectively, the protein was eluted from Avicel with 1% triethylamine solution, dialyzed, and concentrated in an Amicon apparatus using a polyether-sulfone (10-kDa cutoff) membrane. When subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), this fraction was found to contain mainly a protein, called miniCipC1cab, with a molecular mass of 43,000 Da, which is in good agreement with the theoretical mass of miniCipC1 (43,500 Da). Furthermore, the electrophoretic profile was identical to that of the control protein miniCipC1eco [recombinant miniCipC1 produced in E. coli BL21(DE3) from pETcipC1] (16) (Fig. 2A). These two proteins were specifically recognized by the polyclonal antibodies raised against CBM3a (Fig. 2B). N-terminus microsequencing of the protein produced in C. acetobutylicum (AGTGV) matched perfectly with the N terminus of C. cellulolyticum cellulosomal CipC, thus confirming that the purified protein is miniCipC1. Finally, it was estimated that ∼15 mg of pure miniCipC1 can be obtained from 1 liter of overnight culture. These results showed that, as expected, the presence of the two lac operators did not prevent the expression of the gene coding for miniCipC1 in C. acetobutylicum.

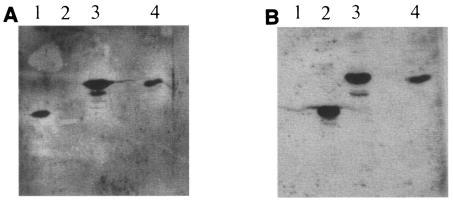

FIG. 2.

Production of CipC1 by C. acetobutylicum. Lane 1, molecular mass markers (LMW; Amersham) (from top to bottom: 94, 67, 43, 30, 20, and 14 kDa); lanes 2, CipC1eco (0.1 mg/ml) purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) recombinant clone; lanes 3, sample of CipC1cab produced in C. acetobutylicum. (A) SDS-PAGE gel stained with Coomassie blue; (B) Western blot; detection with antiserum raised against CBM3a.

Production of Scaf3 by C. acetobutylicum.

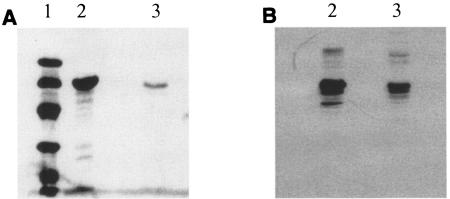

Since miniCipC1 was easily synthesized by C. acetobutylicum, the production of the chimeric protein Scaf3 was carried out. Scaf3 consists of C. cellulolyticum miniCipC1 followed by cohesin 3 from C. thermocellum CipA. To obtain this construct, the 3′ end of cipC1 in pSOS952-cipC1 was modified by introducing an XhoI site upstream of the stop codon and AsuII and BamHI sites downstream, using the primers CipC1D (forward) and rMC1SOS1 (reverse). The amplified fragment, digested by BamHI, was ligated into BamHI-linearized pSOS952. Then, the cohesin 3 coding sequence, obtained from XhoI digestion of pETscaf3 (2), was ligated into the XhoI site of the recombinant pSOS952 plasmid previously obtained, leading to the plasmid pSOS952-scaf3. In the Scaf3 protein produced from this construction, the two cohesin modules are separated by a 44-amino-acid linker. The same protocol as for miniCipC1 was used to produce Scaf3. The fraction eluted from cellulose mainly contained a protein with an apparent mass of 64 kDa on SDS-PAGE, which is in good agreement with the theoretical mass (61,6467 Da) calculated from the chimeric Scaf3 (2) (Fig. 3A). This protein was also recognized by the polyclonal antibodies raised against CBM3a (Fig. 3B) and was produced in its complete form, showing that the long linker located between the two cohesin domains was not cleaved. It was estimated that 10 mg of pure protein can be obtained from 1 liter of culture.

FIG. 3.

Production of Scaf3 by C. acetobutylicum. Lane 1, molecular mass markers (LMW; Amersham) (from top to bottom: 94, 67, 43, 30, 20, and 14 kDa); lanes 2, control Scaf3eco (1.1 mg/ml) produced in E. coli BL21(DE3); lanes 3, sample of Scaf3cab produced in C. acetobutylicum. (A) SDS-PAGE gel stained with Coomassie blue; (B) Western blot; detection with antiserum raised against CBM3a.

Interaction of miniCipC1 and Scaf3 with dockerin domains from C. cellulolyticum and C. thermocellum.

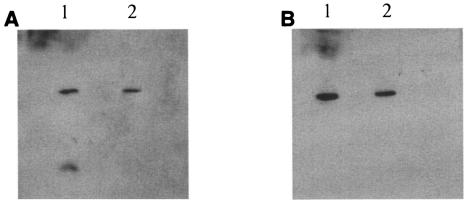

To verify the functionality of the cohesins in miniCipC1 and Scaf3 produced by C. acetobutylicum, specific cohesin-dockerin interactions were performed. After SDS-PAGE, miniCipC1cab and the control miniCipC1eco were blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes and overlaid with either the C. cellulolyticum cellulase Cel48Fc or Cel9Ec. The blotting membranes were subsequently incubated with antiserum raised against Cel48F or Cel9E. In both cases, a band corresponding to miniCipC1 (control or miniCipC1cab) was revealed, showing that Cel48Fc or Cel9Ec was able to interact with the cohesin domain of miniCipC1 produced by C. acetobutylicum (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Interaction of miniCipC1 with Cel48Fc and Cel9Ec. Lanes 1, control miniCipC1eco; lanes 2, sample of miniCipC1cab produced in C. acetobutylicum. (A) Blot overlaid with Cel9Ec and revealed with antiserum raised against Cel9E. (B) Blot overlaid with Cel48Fc and revealed with antiserum raised against Cel48F.

A second set of experiments was carried out to control the functionality of the two cohesins in Scaf3 produced in C. acetobutylicum (Scaf3cab). MiniCipC1cab and Scaf3cab, as well as two control proteins, Scaf3eco (2) and C2-CBMt-eco (3) (the latter is a fragment of CipA from C. thermocellum that contains cohesin 2 and CBM3a), were blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes and overlaid with either Cel9Ec or Cel9Et (harboring a C. thermocellum dockerin). The membranes were subsequently incubated with antiserum raised against Cel9E. As can be seen in Fig. 5A, only miniCipC1cab, Scaf3eco, and Scaf3cab were stained when the membrane was overlaid with Cel9Ec. On the other hand, only the two control proteins C2-CBMt and Scaf3ecol, as well as Scaf3cab, were revealed when the blot was overlaid with Cel9Et (Fig. 5B). All these data suggest that C. acetobutylicum is able to produce functional foreign cohesin domains originating from mesophilic or thermophilic clostridia.

FIG. 5.

Interaction of miniCipC1 and Scaf3 with Cel9Ec and Cel9Et. Lanes 1, control miniCipC1eco; lanes 2, control C2-CBMteco; lanes 3,: control Scaf 3eco; lanes 4, Scaf3cab. (A) Blot overlaid with Cel9Ec. (B) Blot overlaid with Cel9Et. The two blots were revealed with antiserum raised against Cel9E.

These experiments showed that it is possible to produce a hybrid scaffoldin protein in C. acetobutylicum, which is the first step in the production in vivo of a well-defined minicellulosome. The challenge now is to produce, in an active form, the more suitable enzymes selected from a C. cellulolyticum cellulase library. Previous studies have shown that the most efficient minicellulosome was obtained with the complex including the endoprocessive cellulase Cel48F and the endocellulase Cel9G bound onto a single CBM-containing scaffoldin. Such a complex is ∼4-fold more active on Avicel than the mixture Cel48F plus Cel9G in the free state (3).

So far, only one heterologous expression of a cellulase gene (engB from Clostridium cellulovorans) has been reported in C. acetobutylicum ATCC 824 (8). The secretion in the extracellular medium was so poor that the recombinant cellulase could be detected only by Western blotting. Two glycoside hydrolases, Cel6A and Cel5D, from the eukaryotic organism Neocallimastix patriciarum have been produced in Clostridium beijerinckii (9). The two genes were functionally expressed, and the resulting enzymes were excreted into the extracellular medium. Nevertheless, it seems that the production of these enzymes was also very low, not enough to promote significant degradation of cellulose.

Attempts to produce Cel48F and Cel9G with suitable dockerins in C. acetobutylicum are underway. If successful, it will be possible to build a C. acetobutylicum strain able to secrete the most efficient minicellulosome, containing two cellulases and a hybrid scaffoldin. This would constitute a starting point for the development of an industrial process to convert cellulose directly into solvents.

Acknowledgments

We thank Philippe Soucaille for helpful discussions and Odile Valette for technical assistance. We are grateful to Monique Casalot for proofreading the manuscript

This work was financially supported by the AGRICE Program (CNRS-ADEME) no. 9901057.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belaich, J. P., C. Tardif, A. Belaich, and C. Gaudin. 1997. The cellulolytic system of Clostridium cellulolyticum. J. Biotechnol. 57:3-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fierobe, H. P., A. Mechaly, C. Tardif, A. Belaich, R. Lamed, Y. Shoham, J. P. Belaich, and E. A. Bayer. 2001. Design and production of active cellulosome chimeras. J. Biol. Chem. 276:21257-21261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fierobe, H. P., E. A. Bayer, C. Tardif, M. Czjzek, A. Mechaly, A. Belaich, R. Lamed, Y. Shoham, and J. P. Belaich. 2002. Degradation of cellulose substrates by cellulosome chimeras. J. Biol. Chem. 277:49621-49630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher, R. J., J. Helms, and P. Dürre. 1993. Cloning, sequencing and molecular analysis of the sol operon of Clostridium acetobutylicum, a chromosomal locus involved in solventogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 175:6959-6969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontaine, L., I. Meynial-Salles, L. Girbal, X. Yang, C. Croux, and P. Soucaille. 2002. Molecular characterization and transcriptional analysis of adhE2, a gene encoding an NADH-dependent aldehyde-alcohol dehydrogenase responsible for butanol production in alcohologenic cultures of Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. J. Bacteriol. 184:821-830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gal, L., S. Pagès, C. Gaudin, A. Belaich, C. Reverbel-Leroy, C. Tardif, and J. P. Belaich. 1997. Characterization of the cellulolytic complex (cellulosome) produced by Clostridium cellulolyticum. J. Bacteriol. 63:903-909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gal, L., C. Gaudin, A. Belaich, S. Pagès, C. Tardif, and J. P. Belaich. 1997. CelG from Clostridium cellulolyticum: a multidomain endoglucanase acting efficiently on crystalline cellulose. J. Bacteriol. 179:6595-6601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim, A. Y., G. T. Attwood, S. C. Holt, B. A. White, and H. P. Blaschek. 1994. Heterologous expression of endo-b-1,4-glucanase from Clostridium cellulovorans in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 following transformation of the engB gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:337-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Contreras, A. M., H. Smidt, J. Van Der Oost, P. A. M. Claassen, H. Mooibroek, and W. M. De Vos. 2001. Clostridium beijerinckii cells expressing Neocallimastix patriciarum glycoside hydrolases show enhanced lichenan utilization and solvent production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5127-5133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mermelstein, L. D., and E. T. Papoutsakis. 1993. In vivo methylation in Escherichia coli by the Bacillus subtilis phage è3 TI methyltransferase to protect plasmids from restriction upon transformation of Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1077-1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell, W. J. 1998. Physiology of carbohydrate to solvent conversion by clostridia. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 39:31-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosbah, A., A. Belaich, O. Bornet, J. P. Belaich, B. Henrissat, and H. Darbon. 2000. Solution structure of the module X2-1 of unknown function of the cellulosomal scaffolding protein CipC of Clostridium cellulolyticum. J. Mol. Biol. 304:201-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nair, R. V., E. M. Green, D. E. Watson, G. N. Benett, and E. T. Papoutsakis. 1999. Regulation of the sol locus gene for butanol and acetone formation in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 by a putative transcriptional repressor. J. Bacteriol. 181:319-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakotte, S., S. Schaffer, M. Böhringer, and P. Dürre. 1998. Electroporation of, plasmid isolation from and plasmid conservation in Clostridium acetobutylicum DSM 792. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 50:564-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nölling, J., G. Breton, M. V. Omelchenko, K. S. Makarova, Q. Zeng, R. Gibson, H. M. Lee, J. Dubois, D. Qiu, J. Hitti, GTC Sequencing Center Production, Finishing and Bioinformatics Teams, Y. L. Wolf, R. L. Tatusov, F. Sabathé, L. Doucette-Sam, P. Soucaille, M. J. Daly, G. N. Bennett, E. V. Koonin, and D. G. Smith. 2001. Genome sequence and comparative analysis of the solvent-producing bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 183:4823-4838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pagès, S., A. Belaich, C. Tardif, C. Reverbel-Leroy, C. Gaudin, and J. P. Belaich. 1996. Interaction between the endoglucanase CelA and the scaffolding protein CipC of the Clostridium cellulolyticum cellulosome. J. Bacteriol. 178:2279-2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pagès, S., A. Belaich, J. P. Belaich, E. Morag, R. Lamed, Y. Shoham, and E. A. Bayer. 1997. Species-specificity of the cohesin-dockerin interaction between Clostridium thermocellum and Clostridium cellulolyticum: prediction of specificity determinants of the dockerin domain. Proteins 29:517-527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagès, S., A. Belaich, H. P. Fierobe, C. Tardif, C. Gaudin, and J. P. Belaich. 1999. Sequence analysis of scaffolding protein CipC and ORFXp, a new cohesin-containing protein in Clostridium cellulolyticum: comparison of various cohesin domains and subcellular localization of ORFXp. J. Bacteriol. 181:1801-1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsiegla, G., M. Juy, C. Reverbel-Leroy, C. Tardif, J. P. Belaich, H. Driguez, and R. Haser. 1998. The crystal structure of the processive endocellulase CelF of Clostridium cellulolyticum in complex with thiooligosaccharide inhibitor at 2.0 Å resolution. EMBO J. 19:5551-5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reverbel-Leroy, C., A. Bernadac, C. Gaudin, A. Belaich, J. P. Belaich, and C. Tardif. 1996. Molecular study and overexpression of the Clostridium cellulolyticum celF cellulase gene in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 142:1013-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reverbel-Leroy, C., S. Pagès, A. Belaich, J. P. Belaich, and C. Tardif. 1997. The processive endocellulase CelF, a major component of the Clostridium cellulolyticum cellulosome: purification and characterization of the recombinant form. J. Bacteriol. 179:46-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabathé, F. 2002. Le métabolisme des polyosides chez Clostridium acetobutylicum: etude fonctionnelle du cellulosome. Ph.D. thesis. Université de Provence, Marseille, France.

- 23.Sabathé, F., A. Belaich, and P. Soucaille. 2002. Characterization of the cellulolytic complex (cellulosome) of Clostridium acetobutylicum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 217:15-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabathé, F., and P. Soucaille. 2003. Characterization of the CipA scaffolding protein and in vivo production of a minicellulosome in Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 185:1092-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimon, L. J., S. Pagès, A. Belaich, J. P. Belaich, E. A. Bayer, R. Lamed, Y. Shoham, and F. Frolow. 2000. Structure of the family IIIa scaffoldin CBD from the cellulosome of Clostridium cellulolyticum at 2.2 Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D 56:1560-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spinelli, S., H. P. Fierobe, A. Belaich, J. P. Belaich, B. Henrissat, and C. Cambillau. 2000. Crystal structure of a cohesin module from Clostridium cellulolyticum: implications for dockerin recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 304:189-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thormann, K., L. Feustel, K. Lorene, S. Nakojje, and P. Dürre. 2002. Control of butanol formation in Clostridium acetobutylicum by transcriptional activation. J. Bacteriol. 184:1966-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vasconcelos, I., L. Girbal, and P. Soucaille. 1994. Regulation of carbon and electron flow in Clostridium acetobutylicum grown in chemostat culture at neutral pH on mixtures of glucose and glycerol. J. Bacteriol. 176:1443-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]