Abstract

Purpose of review

This review discusses how the bronchial artery circulation is interrupted following lung transplantation and what may be the long-term complications of compromising systemic blood flow to allograft airways.

Recent findings

Preclinical and clinical studies have shown that the loss of airway microcirculations is highly associated with the development of airway hypoxia and an increased susceptibility to chronic rejection.

Summary

The bronchial artery circulation has been highly conserved through evolution. Current evidence suggests that the failure to routinely perform bronchial artery revascularization at the time of lung transplantation may predispose patients to develop the bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome.

Keywords: bronchial artery circulation, chronic rejection, hypoxia, ischemia, lung transplantation

Introduction

Lung transplantation is an effective treatment for end-stage pulmonary parenchymal and vascular disease. However, long-term survival following this procedure remains suboptimal compared with other solid organs owing to the development of chronic rejection or bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS). BOS develops in 30–50% of lung transplant recipients at 3–5 years following transplantation and manifests pathologically as fibro-obliteration of the small airways. The increased incidence of chronic rejection has been suggested to be related to the fact that lung transplants are the only solid organ allografts that do not routinely undergo direct systemic arterial reconnection at the time of surgery [1••]. Under normal settings, the airways are supplied by a dual circulation derived from the bronchial arteries and the pulmonary artery. Prior to transplantation, approximately 50% of the blood flow to airways normally comes from the bronchial arteries and approximately 50% from the poorly oxygenated pulmonary artery circulation [2]. Because only the pulmonary artery circulation is surgically restored at the time of transplantation, the bronchial anastomosis and distal airways may be exquisitely susceptible to further ischemia and hypoxic injury. In fact, early attempts at the lung transplantation were complicated by the development of airway dehiscence or stenosis. Improvements in surgical technique including the use of omental wrapping or telescoping of the bronchial anastomosis led to improved anastomotic healing and the incidence of airway dehiscence decreased. Bronchial artery revascularization at the time of lung transplantation was originally touted as a technique to preserve the anastomosis site by limiting tissue ischemia in the early 1990s. However, given the improvement in airway healing with the anastomotic surgical techniques, reconnection of the bronchial arteries, at the time of transplantation, was deemed unnecessary [3]. This review will address the anatomy of the bronchial artery circulation, the fate of bronchial arteries following lung transplantation, the link between hypoxia, ischemia and fibrosis, and, finally, the rationale for considering reinstitution of bronchial artery revascularization at the time of transplantation.

Normal bronchial artery anatomy

The bronchial artery circulation is part of the systemic circulation, normally arising as two main vessels entering the airways at the hila, and originating from either the aorta, the intercostals arteries or, rarely, the internal mammary and coronary arteries [4•]. This circulation has been highly conserved through mammalian evolution, but its function has not been clearly established [5]. The bronchial artery blood vessels form a plexus with communicating vessels that empty into pulmonary veins to form the bronchopulmonary circulation in normal airways. Bronchial arteries supply the bronchial mucosa as well as the visceral pleura.

The fate of airway microvasculature following lung transplantation

Currently, despite the feasibility of performing bronchial artery revascularization at the time of lung transplantation, the bronchial artery circulation is not routinely reattached under current surgical practice. Preclinical canine studies have demonstrated that the bronchial artery circulation can be slowly restored de novo (i.e. by secondary intention) following transplantation through the process of angiogenesis [6,7]. Similarly, heart–lung transplant recipients occasionally develop systemic collateral circulation to the airways from the coronary arteries [8,9]. The de novo regrowth of bronchial arteries had not been assessed systematically in clinical lung transplantation until recently. Dhillon et al. [1••] reported on the sources of airway perfusion and on the state of airway oxygenation in single lung transplant recipients. They first demonstrated by ventilation perfusion imaging that pulmonary blood flow was preferentially shunted from the native to the transplanted lung by 3 months [73% (Tp) vs. 27% (native)], and tha this shunting was still evident by 12 months [78% (Tp) vs. 22% (native)]. However, as determined by measurement of airway oxygenation, transplanted airways remained relatively hypoxic compared with airways in native (diseased) lungs and to airways in normal lungs. Further, CT-angiography studies failed to demonstrate an identifiable bronchial artery circulation beyond the anastomotic level within the transplanted lung. The authors concluded that airway hypoxia might be due, in part, to the failure of bronchial arteries to regrow into the lung following transplantation. Thus, even though preclinical models and isolated cases of heart–lung transplant patients have demonstrated de-novo growth of bronchial arteries into airways by second intention, this appears to be a limited and very late phenomena in lung transplant recipients; if this regrowth can be said to occur routinely at all as the only patient showing evidence of bronchial artery regrowth was more than a year out posttransplant. This review will discuss how the failure to restore the bronchial artery circulation by primary intention may ultimately have important implications for the overall function and health of the distal airways.

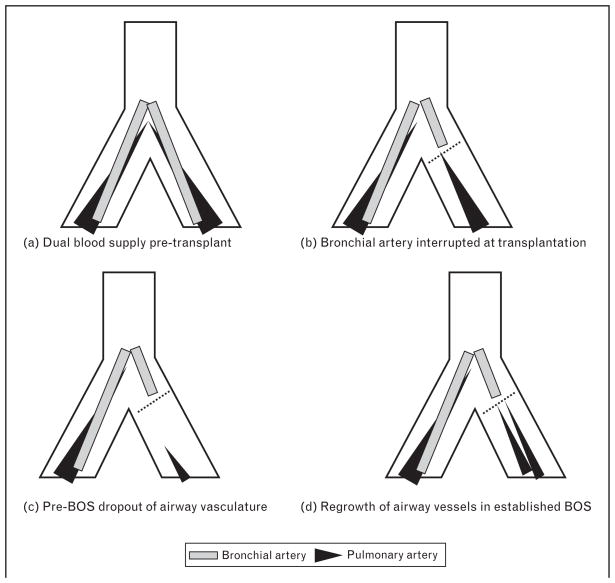

Interest in the development of airway revascularization following lung transplantation increased after the report of recent investigations into the potential role of the loss of airway vascularity in the development of BOS. Autopsy studies from Luckraz et al. [10,11] demonstrated a significant loss of microvasculature in nonobliterated small airways from BOS lungs; suggesting that microvascular loss and airway ischemia is a preceding condition to airway fibrosis. Lung transplant patients who died without BOS had a normal number of blood vessels around their airways. However, in those patients who died with BOS, otherwise normal airways adjacent to BOS airways (i.e. pre-BOS airways) exhibited a significantly diminished microvasculature whereas in adjacent lung with BOS, there were increased numbers of small caliber blood vessels. The cause for the loss of vascularity in pre-BOS airways could be due to immune-mediated injury and inflammation whereas the increase in vascularity in BOS airways could represent angiogenesis in the response to such injury. Loss of a functional microvasculature in an orthotopic airway transplant model identified those grafts that could not be rescued from fibrosis with immuno-therapy [12••]. This preclinical study suggested that steroid-resistance in chronic rejection may be attributed, in part, to the destruction of the microvasculature in grafts. This study also demonstrated how acute rejection could culminate in profound airway hypoxia as graft vessels are destroyed, inflammation becomes significant and airways become transiently ischemic. These concepts describing the dynamic changes of the airway vasculature in lung transplant recipients are summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. The dual circulation of airways following lung transplantation.

This figure models a single lung transplant recipient and how the normal circulation changes following lung transplantation. (a) Cartoon shows normal overlapping bronchial and pulmonary circulations in nontransplanted lung. Airways are normally supplied by a plexus of vessels receiving contribution from both pulmonary artery and bronchial artery circulations. (b) The highly oxygenated bronchial artery circulation is sacrificed at the time of transplantation. The pulmonary artery circulation may primarily supply airways at this time. The dashed line indicates the anastomosis line of a single lung transplant recipient. (c) Pre-BOS dropout of microvasculature is likely of pulmonary artery origin. (d) Return of small neovessels in established BOS. The small gray line extending beyond the anastomosis line represents a putative de-novo bronchial artery possibly growing into the airway in response to airway hypoxia. This regrowth is not radiologically evident within the first year of lung transplantation. Adapted from [1••,10].

Hypoxia, ischemia and airway fibroproliferation

The mechanisms by which hypoxia and ischemia facilitate postinflammatory fibrosis are not established but the clustering of hypoxia, ischemia, inflammation and fibrosis is routinely observed in several clinical situations such as normal skin wound healing [13••] and chronic kidney diseases [14•]. In pulmonary fibrosis in mice and in humans, microarray data sets demonstrate hypoxic signaling to be among the most statistically important dys-regulated pathways [15–17]. In-vitro studies have demonstrated profibrotic phenotypic changes in fibroblasts as a response to hypoxia [18,19]. Epithelial and endothelial cells can undergo mesenchymal transition (EMT) under ischemia to become a source of activated fibroblasts [20]. Hypoxia likely directly contributes to the progression of fibrosis by increasing the release of major extracellular matrix proteins [21••]. Transforming growth factor-β2-induced fibrosis is associated with intense vaso-constriction and tissue hypoxia [22]. Finally, loss of a functional microcirculation should interfere with the effective tissue delivery of systemic immunosuppression. Which of the earlier-mentioned phenomena (i.e. activated fibroblasts, EMT, release of matrix proteins, or altered drug delivery) contributes most significantly to airway fibrosis is not known, but it is clear that inflamed tissue subject to low pO2 and ischemia appears to be at increased risk for fibrotic remodeling.

Potential benefits of restoring the bronchial artery circulation at the time of lung transplantation

As noted before, only the pulmonary artery circulation is restored at the time of transplantation rejection and the highly oxygenated bronchial artery circulation is sacrificed in all lung transplant recipients. Therefore, following lung transplantation, the low O2 pulmonary artery circulation is the major source of blood and microvasculature for transplanted lungs. Exclusion of this rearterialization step may have more distant effects not evident in the early postoperative clinical course. Preclinical and preliminary clinical studies demonstrate that performing bronchial artery revascularization at the time of transplantation improves tissue perfusion with more highly oxygenated blood [23,24], is durable [25], is associated with less epithelial metaplasia [26], is protective of pulmonary endothelium and type II pneumocytes [27], and may postpone the development of BOS, whereas improving patient survival [28].

There are other sequelae, beyond hypoxia, which may occur following the loss of the bronchial artery circulation and could contribute to airway disease. Restoration of the bronchial artery circulation at the time of lung transplantation would theoretically benefit these putative deficits as well. These deficits include the loss of airway nutrition, altered lymphatic flow, decreased airway-lining fluid, attenuated innate immune defenses, diminished clearance of small particles and reduced control of airway temperature and humidity [4•,29]. The bronchial circulation is responsible for the formation of the epithelial-lining fluid, which plays a role in the local defenses against inhaled irritants and foreign substances. In contrast to the pulmonary circulation, bronchial artery vascular transudates appear to contribute to lymphatic flow [30]. What happens to lymphatic flow in the absence of this bronchial artery contribution is not known. A functional bronchial artery circulation is required for the maintenance of normal mucociliary transport [31]. Interrupting the bronchial artery likely leads to interference with absorbing and clearing airway particles [30]. Finally, the airway mucosa responds to the cooling of airways following the inhalation of cold air by increasing bronchial blood flow and by doing this, improves heat and water transfer from the air. This same circulation is capable of conserving moisture in dry environments such that only one-tenth of the normal humidity is exhaled [31]. Therefore, the loss of a bronchial circulation could negatively impact the regulation of airway temperature and humidity. In summary, whereas exaggerated tissue hypoxia with inflammation could occur in the absence of a bronchial artery circulation, there are several other functions normally performed by the bronchial artery circulation that could also contribute to tissue fibrosis. The potential benefits of restoring the bronchial artery circulation at the time of lung transplantation could limit the loss of these normal functions and, in so doing, promote the health of the transplant.

Conclusion

Chronic airway hypoxia and ischemia owing to vascular interruption or injury may be a significant risk factor for airway fibrosis following transplantation [24,32,33]. The bronchial artery normally performs numerous functions, which are likely lost in the absence of reconnection. Emerging preclinical and clinical evidence suggests that bronchial artery revascularization performed at the time of lung transplantation may have graft-protective effects, which will make patients less susceptible to the development of BOS. A multicenter trial now appears to be warranted to study this question.

Acknowledgments

Work supported by HL095686 (MN) and VA Merit BX000509 (MN)

Lung Transplantation and editors Petterson and Budev.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Additional references related to this topic can also be found in the Current World Literature section in this issue (p. 657).

- 1••.Dhillon GS, Zamora MR, Roos JE, et al. Lung transplant airway hypoxia. A diathesis to fibrosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:230–236. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200910-1573OC. A clinical study of single lung transplant recipients illustrating that despite pulmonary artery blood flow being shunted to the transplanted lung, transplant airways are relatively hypoxic; this finding was attributed to the lack of radiologically demonstrable bronchial arteries in transplant airways. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barman SA, Ardell JL, Parker JC, et al. Pulmonary and systemic blood flow contributions to upper airways in canine lung. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:H1130–H1135. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.5.H1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson GA. Airway revascularization: is it necessary? Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:807–808. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)90335-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4•.Paredi P, Barnes PJ. The airway vasculature: recent advances and clinical implications. Thorax. 2009;64:444–450. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.100032. A review of recent advances in the study of airway vasculature. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernard SL, Luchtel DL, Glenny RW, Lakshminarayan S. Bronchial circulation in the marsupial opossum, Didelphis marsupialis. Respir Physiol. 1996;105:77–83. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(96)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearson FG, Goldberg M, Stone RM, Colapinto RF. Bronchial arterial circulation restored after reimplantation of canine lung. Can J Surg. 1970;13:243–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegelman SS, Hagstrom JW, Koerner SK, Veith FJ. Restoration of bronchial artery circulation after canine lung allotransplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1977;73:792–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guthaner DF, Wexler L, Sadeghi AM, et al. Revascularization of tracheal anastomosis following heart-lung transplantation. Invest Radiol. 1983;18:500–503. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh SP, Nath H, McGiffin D, Kirklin J. Coronary tracheal collaterals after heart-lung transplant. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1490–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luckraz H, Goddard M, McNeil K, et al. Is obliterative bronchiolitis in lung transplantation associated with microvascular damage to small airways? Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1212–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luckraz H, Goddard M, McNeil K, et al. Microvascular changes in small airways predispose to obliterative bronchiolitis after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:527–531. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12••.Babu AN, Murakawa T, Thurman JM, et al. Microvascular destruction identifies murine allografts that cannot be rescued from airway fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3774–3785. doi: 10.1172/JCI32311. This study established that the microvasculature in transplanted airways undergoing rejection is actually transiently lost. The implications of interrupted blood flow to a transplant for a period of days are examined and discussed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13••.Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07039. This is an outstanding review of normal wound repair illustrates the roles of hypoxia and ischemia in reparative fibrotic remodeling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14•.Fine LG, Norman JT. Chronic hypoxia as a mechanism of progression of chronic kidney diseases: from hypothesis to novel therapeutics. Kidney Int. 2008;74:867–872. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.350. In chronic kidney disease, functional impairment correlates with tissue fibrosis characterized by inflammation, accumulation of extracellular matrix, tubular atrophy and capillary rarefaction. Loss of the microvasculature denotes a hypoxic milieu and suggested an important role for hypoxia as an explanation for the progressive nature of fibrosis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cosgrove GP, Brown KK, Schiemann WP, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a role in aberrant angiogenesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:242–251. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1151OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaminski N, Rosas IO. Gene expression profiling as a window into idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis pathogenesis: can we identify the right target genes? Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:339–344. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-011TK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuo F, Kaminski N, Eugui E, et al. Gene expression analysis reveals matrilysin as a key regulator of pulmonary fibrosis in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6292–6297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092134099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cool CD, Groshong SD, Rai PR, et al. Fibroblast foci are not discrete sites of lung injury or repair: the fibroblast reticulum. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:654–658. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-205OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karakiulakis G, Papakonstantinou E, Aletras AJ, et al. Cell type-specific effect of hypoxia and platelet-derived growth factor-BB on extracellular matrix turnover and its consequences for lung remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:908–915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manotham K, Tanaka T, Matsumoto M, et al. Transdifferentiation of cultured tubular cells induced by hypoxia. Kidney Int. 2004;65:871–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21••.Distler JH, Jungel A, Pileckyte M, et al. Hypoxia-induced increase in the production of extracellular matrix proteins in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:4203–4215. doi: 10.1002/art.23074. Results from this key study demonstrated that hypoxia contributes directly to the progression of fibrosis in patients with SSc by increasing the release of major extracellular matrix proteins. Targeting of hypoxia pathways is suggested to be of therapeutic value in patients with SScs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ledbetter S, Kurtzberg L, Doyle S, Pratt BM. Renal fibrosis in mice treated with human recombinant transforming growth factor-beta2. Kidney Int. 2000;58:2367–2376. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundset A, Tadjkarimi S, Khaghani A, et al. Human en bloc double-lung transplantation: bronchial artery revascularization improves airway perfusion. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:790–795. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)01273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamler M, Nowak K, Bock M, et al. Bronchial artery revascularization restores peribronchial tissue oxygenation after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:763–766. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norgaard MA, Efsen F, Andersen CB, et al. Medium-term patency and anatomic changes after direct bronchial artery revascularization in lung and heart-lung transplantation with the internal thoracic artery conduit. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;114:326–331. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norgaard MA, Andersen CB, Pettersson G. Airway epithelium of transplanted lungs with and without direct bronchial artery revascularization. Eur J Cardio-thorac Surg. 1999;15:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(98)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nowak K, Kamler M, Bock M, et al. Bronchial artery revascularization affects graft recovery after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:216–220. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.2012101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norgaard MA, Andersen CB, Pettersson G. Does bronchial artery revascularization influence results concerning bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and/or obliterative bronchiolitis after lung transplantation? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;14:311–318. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(98)00182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner EM, Blosser S, Mitzner W. Bronchial vascular contribution to lung lymph flow. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:2190–2195. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.6.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner EM, Foster WM. Importance of airway blood flow on particle clearance from the lung. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:1878–1883. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.5.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deffebach ME, Charan NB, Lakshminarayan S, Butler J. The bronchial circulation. Small, but a vital attribute of the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:463–481. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.2.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yousem SA. The pulmonary pathologic manifestations of the CREST syndrome. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:467–474. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90002-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pettersson G, Arendrup H, Mortensen SA, et al. Early experience of double-lung transplantation with bronchial artery revascularization using mammary artery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1994;8:520–524. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(94)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]