Abstract

Objective:

Interferon has antiproliferative and antiangiogenic properties. We sought to evaluate preliminary efficacy and determine the recommended phase II dose (RP2D) for pegylated interferon-α-2b (PI) in patients with unresectable progressive or symptomatic plexiform neurofibromas (PN).

Methods:

PI was administered weekly in cohorts of 3–6 patients during the dose-finding phase and continued for up to 2 years. Twelve patients were treated at the RP2D to further evaluate toxicity and activity.

Results:

Thirty patients (median age 9.3 years, range 1.9–34.7 years) were enrolled. No dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) was seen in patients treated at the 3 μg/kg dose level (DL) during the first 4 weeks. All 5 patients treated at the 4.5 μg/kg DL came off study or required dose reductions for behavioral toxicity or fatigue. Similar DLT on the 3 μg/kg DL became apparent over time. There was 1 DLT (myoclonus) in 12 patients enrolled at the 1.0 μg/kg DL. Eleven of 16 patients with pain showed improvement and 13 of 14 patients with a palpable mass had a decrease in size. Five of 17 patients (29%) who underwent volumetric analysis had a 15%–22% decrease in volume. Three of 4 patients with documented radiographic progression prior to enrollment showed stabilization or shrinkage.

Conclusions:

The RP2D of PI for pediatric patients with PN is 1 μg/kg/wk. Clinical and radiographic improvement and cessation of growth can occur.

Classification of evidence:

This study provides Class III evidence that pegylated interferon-α-2b in patients with unresectable, progressive, symptomatic, or life-threatening PNs results in radiographic reduction or stabilization of PN size.

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a common autosomal dominant neurogenetic disorder characterized by a wide variety of progressive cutaneous, neurologic, skeletal, and neoplastic manifestations.1 PN are one of several types of neurofibromas that may occur in patients with NF1 and are characterized by a proliferation of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, and mast cells occurring along the length of a nerve. They occur in 25%–50% of adults and children with NF1,2,3 and typically infiltrate adjacent normal tissue, making complete surgical resection usually impossible. As they grow, they frequently become disfiguring as well as disabling or even life-threatening.4,5 Regrowth following subtotal resection is common.6 Standard chemotherapy is not effective and there is currently no standard medical treatment despite various clinical trials.7–9

Interferons (IFNs) have both antiproliferative and antiangiogenic properties.10 A previous study evaluating daily injections of IFN-α-2a in patients with PN showed a high rate of prolonged stable disease as well as clinical improvement in approximately 20%.9 Conjugating proteins with polyethylene glycol (PEG) almost invariably lengthens the plasma half-life by reducing sensitivity to proteolysis, thereby increasing the area under the curve (AUC) and providing protracted activity.11 Pegylation of IFN enhances the therapeutic ratio in patients with hepatitis C,12 and PI has received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for this indication at a dose of 1 μg/kg/wk.

We sought to determine the RP2D, evaluate the toxicity profile, and obtain preliminary activity data for PI given as a weekly injection to patients with PN.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Institutional review boards at participating institutions approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from patients aged ≥18 years or from parents/legal guardians of children aged <18 years, with child assent when appropriate according to individual institutional policies. The trial was registered with www.ClinicalTrials.gov identification number NCT00253474.

Eligibility.

Patients ≥18 months of age with unresectable progressive, symptomatic, or life-threatening PN were eligible. Initially there was no upper age limit, but the study was amended to limit enrollment to patients <21 years after untoward toxicity was encountered in adult patients enrolled on dose levels (DL) 1 and 2. Patients who met the diagnostic criteria for NF1 as defined by the NIH Consensus Conference13 were not required to have biopsy proof of a PN. Evidence of radiographic progression was not necessary. Patients had to have recovered from all toxic effects of previous therapy for their PN, a life expectancy of at least 12 months, and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 0, 1, or 2. Adequate bone marrow (absolute neutrophil count ≥1,500/μL, Hb >10 g/dL, platelet count ≥100,000/μL), renal (normal serum creatinine for age or a creatinine clearance ≥70 mL/min/1.73 m2), and hepatic (total bilirubin <1.5 × normal and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase <2 × upper limit of normal) function was required. Baseline studies had to be obtained within 28 days of study entry.

Exclusion criteria included any clinically significant unrelated systemic illness, cardiovascular disease, or severe psychiatric condition, pregnancy or lactation, exposure to an investigational chemotherapy agent within 30 days, a visual pathway glioma requiring treatment with chemotherapy, or a history of any malignancy.

Study design.

PI was administered as a weekly subcutaneous injection for up to 2 years unless there was evidence of disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or the patient or parent requested to discontinue therapy. Patients or parents were taught to administer the medication in the outpatient setting. Acetaminophen (15 mg/kg up to maximum dose of 1,000 mg) was given 30 minutes prior to the first dose of PI and then every 4–6 hours as needed.

The initial starting dose of PI was 3.0 μg/kg/wk, with subsequent escalation to 4.5 μg/kg/wk. If one of the first 3 patients treated at any DL experienced DLT during the first 4 weeks of treatment, up to 3 additional patients were treated at that DL; if no DLT was observed during that time, the dose would be escalated. The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was defined as the DL immediately below that at which 2 or more patients in a cohort of up to 6 experienced DLT. Due to the observation of delayed toxicity at the first 2 DLs, the study was redesigned and amended to exclude patients >21 years old, extend the evaluation period to 8 weeks in a cohort of 12 patients, and de-escalate the dose to 1.0 μg/kg, the FDA-approved dose for the treatment of hepatitis C. If more than 2 of 12 patients developed DLT, the DL was to be de-escalated further to DL −1 (0.6 μg/kg/dose), and if necessary to 0.4 μg/kg/week. The RP2D was therefore defined as the level where 2 or fewer out of 12 patients developed DLT.

Toxicities were graded according to NCI Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC version 2.0). DLT was initially defined as grade 4 neutropenia or thrombocytopenia that persisted for ≥7 days and grade 3 or 4 nonhematologic toxicity (NHT) attributable to PI (excluding nausea and vomiting, infection, fever, or grade 3 hepatic toxicity that returned to grade 1 or less within 2 weeks of discontinuing PI). At the time, the DLT observation period was extended to include the first 8 weeks of treatment, the definition of DLT was amended to include intolerable behavioral/mood changes, such as hyperactivity, aggression, irritability, or depression that required dose reduction or discontinuation, and persistent (i.e., not transiently related to the injection) grade 2 or higher intolerable constitutional symptoms.

Toxicity evaluations and dose modifications.

Patients were seen at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12, then at months 4, 12, 18, and 24. Toxicity and clinical response to treatment, complete blood counts, and chemistries with liver function tests were evaluated at each visit. Patients who developed grade 4 NHT, grade 3 hyperbilirubinemia, or grade 2 or higher cardiopulmonary toxicity were to be taken off study. Patients with any other DLT had the drug held until toxicity resolved to grade 1 or better, at which point the drug could be restarted at the next lower DL.

Response evaluation.

MRI scans were performed at baseline and after cycles 3, 7, 12, 18, and 24 while on treatment. Initially, WHO solid tumor response criteria based on 2-dimensional tumor measurements were used to assess response. At the time the study was amended to treat patients at the 1.0 μg/kg DL, short T1-inversion recovery (STIR) imaging was required with each MRI scan so that volumetric analyses (VA) could be performed to allow for more sensitive measurement of changes in PN size. A detailed history and physical and patient/parent questionnaire at the time of each response evaluation was used to evaluate clinical response, including improvement in pain, decreased need for pain medications, and subjective decrease in visible mass.

Volumetric MRI method.

Axial and coronal STIR MRI were obtained to encompass the entire PNF using a slice thickness of 5–10 mm with no skips between slices. PN volume was determined as previously described using the MEDx software platform.14

RESULTS

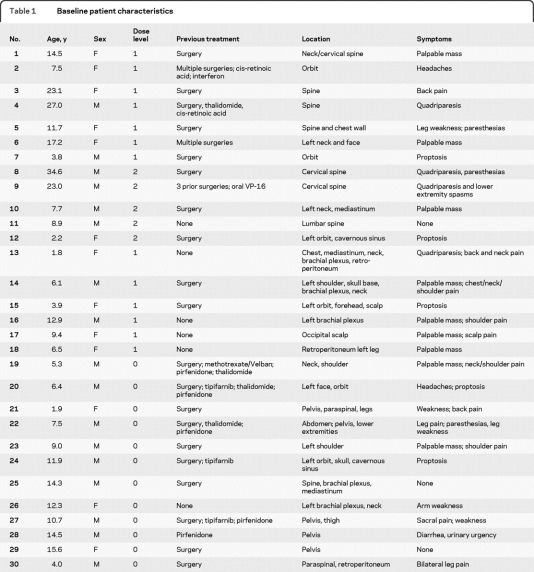

Thirty patients (median age 9.3 years, range 1.9–34.7 years) were enrolled between November 2001 and January 2006. All but one patient with a biopsy-proven PN met the clinical criteria for NF1.1 Twenty-four patients had previously undergone surgical debulking or other medical treatment for their PN (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

Toxicity.

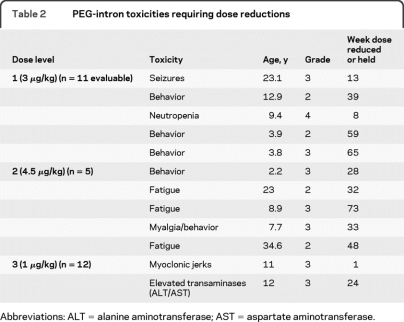

Dose level 1 (3.0 μg/kg).

Thirteen patients were enrolled, of whom 11 were evaluable for toxicity (table 2). One patient received a lower dose (1 μg/kg) due to a calculation error, which was not discovered until he came off study for an unrelated adverse event, and one adult patient withdrew consent after 3 weeks of therapy. Two patients were taken off study for toxicity. A 23-year-old woman developed a tonic-clonic seizure during week 13 of therapy. She was started on anticonvulsants and continued PI at a reduced dose but had a second seizure 4 weeks later. The PI was discontinued and she was removed from study and had no further seizures. A 3.8-year-old boy developed increasingly severe aggression, oppositional/defiant behavior, and hyperactivity, and was withdrawn from study after 15 months of treatment. Of the 9 remaining evaluable patients, 2 developed intolerable behavioral problems over time with hyperactivity, aggression, and oppositional/defiant behavior, and a third patient developed dose-limiting neutropenia.

Table 2.

PEG-intron toxicities requiring dose reductions

Abbreviations: ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase.

Dose level 2 (4.5 μg/kg).

Five patients were enrolled. Two patients (age 25 and 34 years) developed intolerable fatigue and discontinued the drug after 6–8 months of therapy. Of the 3 younger patients, one developed severe behavioral problems and depression after 2–3 months of treatment as well as severe myalgias requiring dose reduction. Another patient developed increased hyperactivity and behavioral outbursts within weeks of starting therapy, which became intolerable and required dose reduction. The third patient required dose reduction for persistently severe fatigue. All symptoms requiring dose reduction/withdrawal became intolerable after the evaluation period (4 weeks) was completed.

Dose level 0 (1.0 μg/kg).

Twelve patients were enrolled. There was one DLT in a 10-year-old boy who developed myoclonic jerks of his upper and lower extremities shortly after receiving the first dose of PI. The PI was held and over the next 3 weeks, the myoclonus became less frequent and eventually resolved. The PI was restarted at a dose of 0.6 μg/kg/wk but the myoclonus recurred, this time resolving within a few days. The PI was restarted at 0.3 μg/kg/wk but the myoclonus again recurred, at which point the patient was taken off study. A few weeks later, the myoclonus occurred again and continued intermittently for months after discontinuing the drug. A second patient developed grade 3 elevation of SGPT and SGOT after 6 months of treatment. These returned to normal after the drug was discontinued but the toxicity recurred when the PI was restarted at 0.6 μg/kg/week. The toxicity resolved when the drug was held but the family decided to stop treatment. This dose level was therefore determined to be the RP2D.

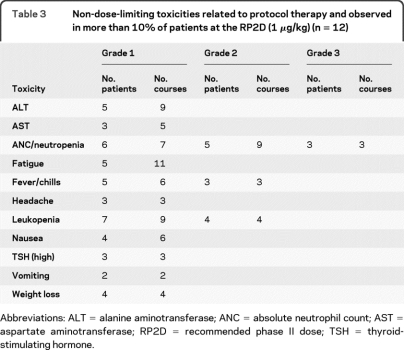

Constitutional symptoms (fever, chills, fatigue) were almost universal after the first dose and were more severe and less likely to subside over time at the higher DLs. Non-dose-limiting toxicities at the RP2D (table 3) consisted mostly of mild constitutional symptoms and nausea/vomiting that occurred within hours of each dose and generally improved over the first few weeks. Three patients developed an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), with a normal free T4. No treatment was required and the TSH returned to normal after therapy was completed. Mild grade 1 and 2 neutropenia was common. Three patients (25%) developed grade 3 neutropenia: in 2 patients the neutropenia occurred after several months of treatment and resolved to grade 1 or less despite continuing drug; 1 patient developed grade 3 neutropenia during the first month in conjunction with myoclonic jerks, with subsequent discontinuation of the drug.

Table 3.

Non-dose-limiting toxicities related to protocol therapy and observed in more than 10% of patients at the RP2D (1 μg/kg) (n = 12)

Abbreviations: ALT = alanine aminotransferase; ANC = absolute neutrophil count; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; RP2D = recommended phase II dose; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone.

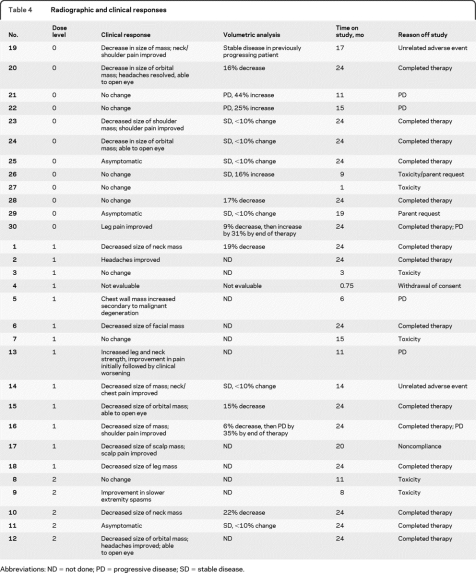

Responses.

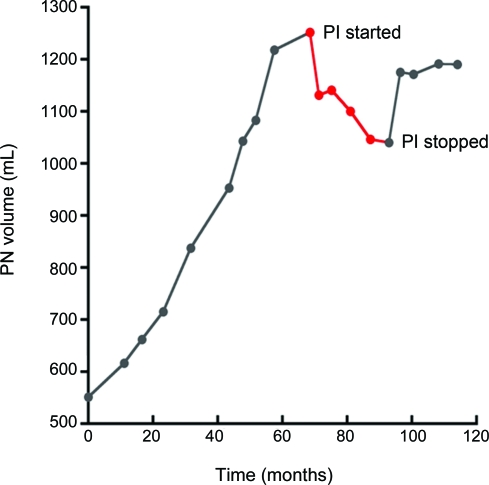

Responses are summarized in table 4. Eleven of 16 patients (69%) with baseline pain had improvement or resolution of pain after starting treatment, although 2 patients with initial improvement eventually developed clinical worsening. Thirteen of 14 patients (93%) with a visible or palpable mass had a subjective decrease in size, and 4 of 5 patients with proptosis secondary to an orbital PN showed noticeable improvement in the ability to open the eye. Twelve patients did not have VA performed either because they did not have STIR images obtained or because of small tumor size or poor contrast between the tumor and surrounding tissues. Seventeen patients had the necessary imaging performed at baseline and at some point during the study to be able to undergo VA of response. Five of these patients (29.4%) showed a 15%–22% decrease in the volume of their tumor during the course of treatment. Due to inconsistencies in the imaging obtained, VA was not able to be obtained at each time point for all patients, so that determination of the median time to best response was not possible. However, responses seemed to be fairly rapid, with a 10%–18% decrease in volume by 4–6 months in the 4 responding patients who had VA performed at the first time point. Responses tended to plateau or diminish after the first year. Of the 4 evaluable patients who had documented radiographic progression by VA prior to starting PI therapy, tumor volume stabilized or decreased in 3. All of these patients had developed progressive disease on various other therapeutic trials for PN. The figure shows the growth of a large pelvic tumor in patient 28 prior to, during, and following treatment with PI.

Table 4.

Radiographic and clinical responses

Abbreviations: ND = not done; PD = progressive disease; SD = stable disease.

Figure. Plexiform neurofibroma (PN) growth before, during (in red), and after treatment with pegylated interferon-α-2b (PI).

Patient 28: Pelvic PN volume prior to starting treatment, with a subsequent 17% decrease in size after starting PI, followed by an increase in volume after discontinuing treatment.

Five patients developed tumor progression 11–24 months after starting treatment, including 3 patients who showed initial clinical or radiographic improvement, or both. A sixth patient (no. 5) developed rapidly progressive disease after 6 months of treatment and was found to have malignant degeneration of a chest wall PN and died.

No patient had a >25% decrease in tumor size by 2D measurements.

DISCUSSION

IFNs exert antitumor activity through direct antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects as well as modulation of the host immune response.10 IFN is also a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis as evidenced by its utility in the treatment of life-threatening hemangiomas of infancy.15 In tumor cell lines, continuous and prolonged exposure to IFN optimizes both the antiproliferative and antiangiogenic effect16–19 and the highest response rates in patients with metastatic melanoma have been obtained with uninterrupted schedules.16 When IFN was removed from the medium, glioma cell line growth rapidly returned to the pretreatment rate.18

Although IFN-α has been used to treat a variety of neoplasms, the optimal dose has not been established. In vivo studies have not shown a clear dose-response relationship in solid tumors, other than for possibly melanoma.20 In CML, low-dose IFN is as effective as higher doses,21 whereas toxicity is clearly dose-related. In a study of the optimal anti-angiogenic dose and schedule of IFN-α-2a in a human bladder cancer cell line resistant to the antiproliferative effects of IFN implanted into the bladders of nude mice, doses far below the maximally tolerated dose produced the most significant inhibition of tumor growth, vascularization, and inhibition of angiogenesis-regulating genes.19 These effects were maximal when the IFN was given daily. Administration of higher doses failed to produce significant anti-angiogenic effects. The optimal dose in this study correlates with a PI dose of 0.3–0.4 μg/kg/wk. Indeed, in our study, responses were seen at the lower DLs, supporting the preclinical data. Furthermore, dose de-escalation was required due to intolerable fatigue in older patients and behavioral changes in younger patients. These toxicities typically developed after several weeks, necessitating a longer observation period in order to adequately assess tolerability. This is consistent with the conclusions of an analysis of NF-1–related trials that the clinical trial design and endpoints used in patients with refractory cancer are not necessarily appropriate for patients with NF1-related tumors.5

The responsiveness of PN to IFN was first reported in 200622 in a child with a PN of the pelvis causing severe pain due to nerve compression. The patient experienced dramatic pain relief within 2 weeks of starting IFN, although no objective decrease in the size of the tumor by standard imaging was seen. A randomized, noncomparative phase II trial treated 57 evaluable patients with unresectable PN with either cis-retinoic acid or IFN-α-2a.9 At 18 months of follow-up, 26 of 27 of patients (96%) treated with IFN were considered to be stable and 5 patients (18%) showed symptomatic improvement. Although the radiographic responses cannot be compared to the current trial given the different evaluation criteria, the percentage of patients who had improvement in pain and a subjective decrease in the size of the visible or palpable tumor seems better on our trial using the pegylated form of IFN.

A longitudinal study evaluating PN growth rate showed a significant variability among patients,23 making clinical trial design for treatment of these tumors challenging. No study to date has demonstrated significant radiographic responses using standard 2D response evaluation. This is most likely due to the innate resistance of the tumor to the therapeutic agents evaluated thus far. In addition, the infiltrating nature and large size of these tumors make 2D measurements, and therefore determination of change in size over time, imprecise. Since PN are bright compared with normal-surrounding tissue on STIR MRI, a program for automated volumetric analysis using STIR images that reproducibly quantifies the volume of these complex lesions and detects small changes over time was developed and validated at the National Cancer Institute.14,23 Using this technique, we found that approximately 30% of patients had a decrease in the volume of the tumor and an additional subset of patients with documented progression prior to starting the drug had a definite plateau in growth rate after starting PI. Since PN growth is often most rapid in younger children,23 the ability to halt growth during the period when these tumors grow the fastest is of tremendous benefit. Furthermore, approximately 70% of patients with baseline pain showed subjective improvement within weeks of starting therapy, and the majority of patients with a visible or palpable mass had a subjective decrease in tumor size, including a noticeable improvement in proptosis and the ability to open the eye. We acknowledge the limitations of using subjective assessments to determine clinical response and more stringent, validated criteria have been incorporated into an ongoing phase II study. Mandated STIR images at baseline and with each scheduled evaluation will also allow us to better understand the time course of response and the optimal duration of therapy.

Footnotes

- AUC

- area under the curve

- DL

- dose level

- DLT

- dose-limiting toxicity

- FDA

- Food and Drug Administration

- IFN

- interferon

- MTD

- maximum tolerated dose

- NF1

- neurofibromatosis type 1

- NHT

- nonhematologic toxicity

- PEG

- polyethylene glycol

- PI

- pegylated interferon-α-2b

- PN

- plexiform neurofibroma

- RP2D

- recommended phase II dose

- STIR

- short T1-inversion recovery

- TSH

- thyroid-stimulating hormone

- VA

- volumetric analyses.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Statistical analysis was conducted by Dr. Douglas M. Potter.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Jakacki serves as a consultant for OSI Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and receives research support from the NIH and the Brain Tumor Society. Dr. Dombi, Dr. Potter, Dr. Goldman, and Dr. Allen report no disclosures. Dr. Pollack serves on the editorial board of Journal of Neurosurgery and Pediatric Blood and Cancer; receives royalties from the publication of Principles and Practice of Pediatric Neurosurgery (Thieme, 2008); and receives research support from the NIH, the Brain Tumor Society, Children's Brain Tumor Foundation, and Children's Oncology Group. Dr. Wideman serves on the editorial board of The Oncologist.

REFERENCES

- 1. Goldberg Y, Dibbern K, Klein J, Riccardi VM, Graham JM., Jr Neurofibromatosis type I: an update and review for the primary physician. Clin Pediatr 1996; 35: 545–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hajdu SI. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors: histogenesis, classification and prognosis. Cancer 1993; 72: 3549–3552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huson SM, Harper PS, Compston DAS. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis: a clinical and population study in south-east Wales. Brain 1988; 111: 1355–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cnossen MH, de Goede-Bolder A, van den Broek KM, et al. A prospective 10 year follow up study of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Arch Dis Child 1998; 78: 408–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim A, Gillespie A, Dombi E, et al. Characteristics of children enrolled in treatment trials for NF1-related plexiform neurofibromas. Neurology 2009; 73: 1273–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Needle MN, Cnaan A, Dattilo J, et al. Prognostic signs in the surgical management of plexiform neurofibroma: the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia experience, 1974–1994. J Pediatr 1997; 131: 678–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gupta A, Cohen BH, Ruggieri P, Packer RJ, Phillips PC. Phase I study of thalidomide for the treatment of plexiform neurofibroma in neurofibromatosis 1. Neurology 2003; 60: 130–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Widemann BC, Dombi E, et al. Phase I trial of pirfenidone in children with neurofibromatosis 1 and plexiform neurofibromas. Pediatr Neurol 2007; 36: 293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Packer RJ, Gutmann DH, Rubenstein A, et al. Plexiform neurofibromas in NF1: toward biologic-based therapy. Neurology 2002; 58: 1461–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sen GC, Lengyel P. The interferon system: a bird's eye view of it's biochemistry. J Biol Chem 1992; 267: 5017–5020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nucci M, Shorr R, Abuchowski A. The therapeutic value of polyethylene glycol-modified proteins. Adv Drug Deliv Reviews 1991; 6: 133–151 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Rasenack J, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 1666–1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference: Neurofibromatosis: Conference Statement. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1988; 45: 575–578 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Solomon J, Warren K, Dombi E, Patronas N, Widemann B. Automated detection and volume measurement of plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1 using magnetic resonance imaging. Comput Med Imaging Graph 2004; 28: 257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ezekowitz RAB, Mulliken JB, Folkman J. Interferon alfa-2a therapy for life-threatening hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med 1992; 326: 1456–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Legha SS. The role of interferon alfa in the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Semin Oncol 1997; 24 (suppl): 24–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singh RK, Gutman M, Bucana CD, Sanchez R, Llansa N, Fidler IJ. Interferons-alpha and -β downregulate the expression of basic fibroblast growth factor in human carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92: 4562–4566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yung WK, Steck PA, Kelleher PJ, Moser RP, Rosenblum MG. Growth inhibitory effect of recombinant alpha and beta interferon on human glioma cells. J Neurooncol 1987; 5: 323–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Slaton JW, Perrotte P, Inoue K, Dinney CP, Fidler IJ. Interferon-alpha-mediated down-regulation of angiogenesis-related genes and therapy of bladder cancer are dependent on optimization of biological dose and schedule. Clin CA Res 1999; 5: 2726–2734 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wheatley K, Ives N, Hancock B, Gore M, Eggermont A, Suciu S. Does adjuvant interferon-alpha for high-risk melanoma provide a worthwhile benefit? A meta-analysis of the randomised trials. Cancer Treat Rev 2003; 29: 241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kluin-Nelemans HC, Buck G, Le Cessie S, et al. Randomized comparison of low-dose versus high-dose interferon-alfa in chronic myeloid leukemia: prospective collaboration of 3 joint trials by the MRC and HOVON groups. Blood 2004; 103: 4408–4415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kebudi R, Ayan I. Interferon-alpha for neurofibromas. Med Pediatr Oncol 1996; 26: 220–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dombi E, Solomon J, Gillespie AJ, et al. NF1 plexiform neurofibroma growth rate by volumetric MRI: relationship to age and body weight. Neurology 2007; 68: 643–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]