Abstract

The intracellular concentration of the Escherichia coli factor for inversion stimulation (Fis), a global regulator of transcription and a facilitator of certain site-specific DNA recombination events, varies substantially in response to changes in the nutritional environment and growth phase. Under conditions of nutritional upshift, fis is transiently expressed at very high levels, whereas under induced starvation conditions, fis is repressed by stringent control. We show that both of these regulatory processes operate on the chromosomal fis genes of the enterobacteria Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, Erwinia carotovora, and Proteus vulgaris, strongly suggesting that the physiological role of Fis is closely tied to its transcriptional regulation in response to the nutritional environment. These transcriptional regulatory processes were previously shown to involve a single promoter (fis P) preceding the fis operon in E. coli. Recent work challenged this notion by presenting evidence from primer extension assays which appeared to indicate that there are multiple promoters upstream of fis P that contribute significantly to the expression and regulation of fis in E. coli. Thus, a rigorous analysis of the fis promoter region was conducted to assess the contribution of such additional promoters. However, our data from primer extension analysis, S1 nuclease mapping, β-galactosidase assays, and in vitro transcription analysis all indicate that fis P is the sole E. coli fis promoter in vivo and in vitro. We further show how certain conditions used in the primer extension reactions can generate artifacts resulting from secondary annealing events that are the likely source of incorrect assignment of additional fis promoters.

Gene regulatory proteins in bacteria are generally controlled in response to environmental changes in order to generate a suitable cellular response (9, 12, 20, 36). A common strategy is to exert allosteric regulation of specific transcription regulators by methods such as ligand binding (7, 14, 47) and covalent modification (16, 17, 37, 48). Another strategy is to control the availability of transcriptional regulators, which can rely on molecular processes such as sequestration (39, 40), proteolysis (18), and control of synthesis at transcriptional or posttranscriptional levels (15, 19, 23, 29, 30). The Escherichia coli DNA binding protein Fis (factor for inversion stimulation) serves as a transcription regulator of numerous genes, including ribosomal and tRNA genes (5, 11, 21, 34, 45, 52, 53), and its activity appears to be controlled largely by drastic changes in its intracellular level, which, in turn, is affected by changes in the nutritional environment (2, 35, 38, 49).

When saturated cultures of E. coli are diluted in rich media, the amounts of Fis protein and mRNA rapidly increase from undetectable to very high levels during the early logarithmic growth phase. The levels then decrease during late logarithmic growth and again become undetectable during the stationary phase (2, 35, 38). The magnitude of this regulation is emphasized by the finding that Fis is the most abundant DNA binding protein during the early logarithmic growth phase in cells grown in rich media (1). If, on the other hand, E. coli cells are starved for amino acids, fis expression becomes inhibited by stringent control (38, 50). It is therefore tempting to speculate that the level of Fis may serve as a way for cells to monitor and rapidly respond to changes in the nutritional quality of the environment.

Growth phase-dependent regulation and stringent control are distinct transcriptional regulatory mechanisms that act upon the fis promoter (fis P) to regulate fis expression (2, 50). This is the only promoter that was previously identified to be responsible for expression of the fis operon, which is comprised of yhdG (encoding a tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase) and fis (2, 4, 38, 44, 50, 51). In Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, a very similar promoter sequence was found that precedes the fis operon and is similarly expressed in a growth phase-dependent fashion (42). Very similar fis promoter sequences have also been found in Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, Erwinia carotovora, and Proteus vulgaris, which are capable of initiating transcription from a multicopy plasmid placed in an E. coli host (3). In recent work, however, it was reported that there are at least four promoters, designated P1, P2, P3, and P4, that precede the E. coli fis operon and contribute to its expression and regulation (31). Moreover, results of primer extension assays have suggested that P2 (and not the previously identified fis P or P1) is the predominant promoter in vivo. Thus, we wished to further investigate the contribution of these promoters to the expression and regulation of fis.

In this study we examined the pattern of expression of fis within its natural chromosomal loci in K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris in response to a nutrient upshift or induced starvation. We found that the corresponding regulatory processes are very strongly conserved in these bacteria, thus emphasizing their importance in controlling the activity of Fis in response to sudden changes in the nutritional environment. In addition, we conducted a rigorous examination of the E. coli fis promoter region and concluded that a single promoter (fis P) is involved in the expression and growth phase-dependent regulation of fis. Given the strong conservation of this promoter sequence, it is also likely to play a unique role in fis expression and regulation in other bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and enzymes.

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., Fisher Scientific Co., VWR Scientific, or Life Technologies Inc. (GIBCO BRL). E. coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme (Eσ70) was purchased from EPICENTRE. S1 nuclease, Taq polymerase, and avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase (RT) were obtained from Roche Molecular Biochemicals. Superscript II RT (a modified form of moloney murine leukemia virus RT) and Thermoscript (a modified version of AMV RT) were obtained from Invitrogen Corp., DNA Sequenase was obtained from U.S. Biochemical Corp., and all other enzymes were obtained from New England BioLabs Inc., unless otherwise indicated. An RNeasy RNA purification kit was obtained from Qiagen, Inc. A MICROBExpress kit was obtained from Ambion, Inc. Deoxyribonucleotides, ribonucleotides, and the radioisotopes [α-32P]dATP and [γ-32P]ATP were purchased from Amersham Biosciences Corp. Dideoxynucleotides were obtained from Invitrogen Corp. or U.S. Biochemical Corp. Oligonucleotides were synthesized with a Perkin-Elmer automatic DNA synthesizer at the Department of Biological Sciences, University at Albany, SUNY, or were obtained from The Center for Comparative Functional Genomics at The University at Albany, SUNY, or from Operon Technologies Inc. (Alameda, Calif.).

Plasmids, bacterial strains, and growth conditions.

All plasmids used in this work are briefly described in Table 1. E. coli strains MG1655 (F− λ− prototroph) and RJ1880 (MG1665 relAΔ1251 spoTΔ1207) were obtained from R. L. Gourse (University of Wisconsin, Madison). E. coli strains CSH50 [ara Δ(lac pro) thi rpsL], RJ1800 (MG1655 fis::kan), RZ211 (CSH26 recA56 srl str), and RJ1561 (RZ211 fis::kan) were obtained from R. C. Johnson (University of California, Los Angeles). K. pneumoniae strain KC2668 [hutC515 Δ(bla-2)] was obtained from R. A. Bender (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor). E. carotovora subsp. carotovora Ecc71 (lac) was obtained from A. K. Chatterjee (University of Missouri). S. marcescens Bizio and P. vulgaris Hauser were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Referenceb |

|---|---|---|

| pMB261a | K. pneumoniae fis operon region from 201 bp upstream of yhdG to 45 bp downstream of the yhdG initial nucleotide, cloned into the EcoRI and XbaI sites of pRJ800 | 3 |

| pMB262a | P. vulgaris fis operon region from 205 bp upstream of yhdG to 45 bp downstream of the yhdG initial nucleotide, cloned into the EcoRI and XbaI sites of pRJ800 | 3 |

| pMB340a | K. pneumoniae fis operon region from the beginning of yhdG to the eighth codon of fis, cloned into the EcoRI and SphI sites of pRJ800 | |

| pMB341a | S. marcescens fis operon region from the beginning of yhdG to the eighth codon of fis, cloned into the EcoRI and SphI sites of pRJ800 | |

| pMB342a | P. vulgaris fis operon region from the beginning of yhdG to the eighth codon of fis, cloned into the EcoRI and SphI sites of pRJ800 | |

| pMB343 | E. carotovora fis operon region from the beginning of yhdG to the eighth codon of fis, cloned into the KpnI and SphI sites of pRJ800 | |

| pMB388a | E. carotovora fis operon region from 140 bp upstream of yhdG to 45 bp downstream of the yhdG initial nucleotide, cloned into the EcoRI and XbaI sites of pRJ800 | |

| pMB391a | S. marcescens fis operon region from 140 bp upstream of yhdG to 45 bp downstream of the yhdG initial nucleotide, cloned into the EcoRI and XbaI sites of pRJ800 | |

| pRJ800 | pBR322 derived; pUC18 polylinker region precedes a (trp-lac)W200 fusion; Ampr | 2 |

| pRJ804 | 1,622 bp KpnI fragment containing the E. coli fis promoter region from position −762 to position 860 relative to fis P, cloned into the KpnI site of pUC18 | 2 |

| pRJ807 | E. coli fis under Ptac control within pBR322-based vector; Ampr Kanr | 41 |

| pRJ920a | E. coli fis operon region from the 13th codon of yhdG (Sau3AI site) to the 16th codon of fis (HpaI site), cloned between the EcoRI and SmaI sites of pRJ800 | 2 |

| pRJ1028a | E. coli fis P region from position −375 to position 83 relative to the fis P start site, cloned within pRJ800 EcoRI and HindIII sites | 44 |

| pRJ1071a | E. coli fis P region from position −168 to position 83 relative to the fis P start site (or 201 bp upstream of yhdG to 45 bp downstream of the yhdG initial nucleotide), flanked by EcoRI and PstI sites in pRJ800 | 44 |

| pRO362 | E. coli fis P region from position −168 to position 83 relative to the fis P start site, cloned into the pRJ800 EcoRI and BamHI sites of pKK223-3 (Pharmacia), replacing the tac promoter; Ampr | |

| pRO468 | E. coli fis P region from position −168 to position 83 relative to the fis P start site, with the fis P −10 promoter region replaced with a perfect match to the consensus −10 sequence, cloned into the pRJ800 EcoRI and BamHI sites of pKK223-3 (Pharmacia), replacing the tac promoter; Ampr | |

| pTP435 | pKK223-3 (Pharmacia) cleaved with BamHI and HindIII, blunt ended, and recircularized to delete the tac promoter; Ampr | |

| pTP438a | E. coli fis P region from position −194 to position 83 relative to the fis P start site, cloned into the pRJ800 EcoRI and HindIII sites | |

| pTP439a | E. coli fis P region from position −194 to position −42 relative to the fis P start site, cloned into the pRJ800 EcoRI and HindIII sites | |

| pTP455 | E. coli fis P region from position −194 to position −42 relative to the fis P start site, cloned into the pRJ800 EcoRI and HindIII sites in the orientation opposite that of pTP439 |

The DNA fragments are oriented within pRJ800 such that a promoter transcribing towards the fis gene would be expected to transcribe the fis-lac operon fusion.

Plasmids were constructed during this study, unless indicated otherwise.

Bacterial culture media were obtained from Difco Laboratories. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (24) or in 2X YT medium (16 g of tryptone per liter, 10 g of yeast extract per liter, 5 g of NaCl per liter; pH 7.4) at 37°C with shaking. K. pneumoniae and S. marcescens were grown in LB medium at 37°C, P. vulgaris was grown in tryptic soy broth (17 g of tryptone per liter, 3 g of Bacto Soytone [Difco] per liter, 2.5 g of dextrose per liter, 5 g of NaCl per liter, 2.5 g of K2HPO4 per liter; pH 7.4) at 37°C, and E. carotovora was grown in brain heart infusion (200 g of calf brain infusion per liter, 250 g of beef heart infusion per liter, 10 g of Bacto Proteose Peptone [Difco] per liter, 2 g of dextrose per liter, 5 g of NaCl per liter, 2.5 g of Na2HPO4 per liter; pH 7.4) at 32°C (which was a more favorable growth temperature for this organism). Plasmid-containing cells were selected by addition of 100 μg of ampicillin per ml (for E. coli and K. pneumoniae), 400 μg of ampicillin per ml (for S. marcescens), or 750 μg of ampicillin per ml (for E. carotovora) to the medium. E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and E. carotovora were made competent and transformed with pRJ800-based plasmids by using the CaCl2 treatment described previously for E. coli (26). S. marcescens was transformed by electroporation by using a Bio-Rad bacterial transformation apparatus under the conditions described previously for E. coli (25). We were unable to transform P. vulgaris by either method.

Stringent control assays were performed as described previously (43). Saturated cell cultures were diluted in rich medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05 and grown to an OD600 of 0.15 (or 0.20 for S. marcescens and E. carotovora). At these stages of growth, a portion of each cell culture was collected for preparation of total RNA. One half of the remainder of the culture was treated with 1 mg of serine hydroxamate (SeOH) per ml, and the other half received an equivalent volume of sterile H2O as a control. After 30 min of treatment, both cultures were harvested for preparation of total RNA. All three RNA samples were subjected to Northern blot analysis by using the corresponding fis gene as the 32P-labeled DNA probe.

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described previously (24). Generally, saturated cultures of bacterial strains carrying pRJ800-based plasmids were diluted 50-fold in rich medium, grown for 75 min with shaking (or for 90 min in the case of E. carotovora), and analyzed for β-galactosidase activity, unless otherwise indicated. The values are given as averages and standard deviations for three independent assays.

RNA preparation.

Total RNA was generally prepared by using the hot acid phenol extraction method (8), which in our hands gives consistent RNA yields (within 10%) from equivalent quantities of cells. In some cases a Qiagen RNeasy total RNA isolation kit was used to isolate total RNA from E. coli strains by following the supplier's recommended procedures (Qiagen, Inc.). The two methods resulted in comparable RNA quality, as judged by an OD260/OD280 ratio of about 1.75. E. coli 16S and 23S rRNA were separated from total RNA with a MICROBExpress kit (Ambion, Inc.) by using the recommended procedure. The rRNA was recovered from the magnetic beads by heating the beads at 65°C for 15 min in 20 μl of RNase-free TE buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA), followed by magnetic separation of the beads.

Northern blots.

Saturated cell cultures were diluted 100-fold in appropriate rich medium and grown with shaking at 37°C (or 32°C for E. carotovora). At various times during growth of the cultures, comparable quantities of cells (as determined by OD600 values) were withdrawn for preparation of total RNA by the hot acid phenol method. The entire RNA contents were electrophoresed in 1% agarose gels containing 7% formaldehyde and transferred to nitrocellulose filters as described previously (46). Hybridizations were performed at 42°C in a 50% formamide hybridization solution. The fis gene corresponding to the bacterium analyzed was used as a probe and was labeled with [α-32P]dATP by extension of random primers, as described previously (46). The fis mRNA signals were detected by autoradiography and were quantified by using a Storm 860 PhosphorImager and the ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif.).

S1 nuclease mapping.

S1 nuclease mapping was performed as described previously (46). A single-stranded DNA probe that was end labeled with 32P was made by subjecting primer oRO109 (5′-GCTGATATTGTCCGATG) that was 5′ end labeled with 32P to 30 cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension by using Taq polymerase and pRJ1071 cleaved with EcoRI and HindIII as the template. The resulting antisense DNA strand extended from position 54 to position −168 (5′ to 3′ direction) relative to the fis promoter (fis P). Approximately 40,000 cpm of the DNA probe was mixed with 10 μg of total cellular RNA in 30 μl of hybridization buffer [40 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES) (pH 6.4), 1 mM EDTA, 0.4 M NaCl, 80% formamide], heated at 85°C for 10 min, and then allowed to hybridize at 30°C for 16 h. The sample was then mixed with 300 μl of an S1 nuclease solution (0.28 M NaCl, 50 mM sodium acetate, 4.5 mM ZnSO4, 20 μg of sonicated denatured salmon sperm DNA per ml, 200 U of S1 nuclease) and incubated at 37°C for 90 min. The reaction was stopped by addition of 80 μl of a solution containing 4 M ammonium acetate, 50 mM EDTA, and 50 μg of yeast tRNA per ml. The mixture was extracted with 1 volume of buffer-equilibrated 1:1 phenol-chloroform (46) and then again with 1 volume of chloroform. The nucleic acids in the aqueous layer were precipitated by addition of 2.5 volumes of cold ethanol and incubation at −20°C for 2 h. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g, dried, resuspended in formamide loading buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 50% formamide, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 0.2% xylene cyanol), and analyzed by electrophoresis on 8% polyacrylamide-7 M urea gels with TBE (90 mM Tris-borate [pH 8.0], 2 mM EDTA) as the running buffer.

Primer extension.

Primer extension reactions were conducted by using 10 μg of total RNA under different conditions depending on the RT used. Reactions with AMV RT were performed at 47°C with 1 to 2 U of enzyme, as previously described (13, 51) except where otherwise indicaed. Reactions with Thermoscript RT were performed at temperatures indicated below with 2 U of enzyme by using the supplier's recommended procedures (Invitrogen Corp.). Reactions with SuperScript II RT were performed at 42°C with 200 U of enzyme according to the suppliers recommended procedure (Invitrogen Corp.) or with 20 U of enzyme. Reactions were performed with the following primers that were 5′ end labeled with 32P: oRO109 (5′-GCTGATATTGTCCGATG), which anneals to a region downstream of the fis promoter from position 54 to position 38; oRO446 (5′-CGCTGCGATCAGGCGATTTCT), which is complementary to the region from position 77 to position 57 relative to the fis promoter start site; and oRO447 (5′-AGGTCTGTCTGTAATGCCAG), which is complementary to the region from position 104 to position 85.

In vitro transcription.

Transcription reactions were performed either with a 283-bp linear DNA fragment containing the fis promoter region from position −168 to position 83 relative to the predominant fis promoter start site or with supercoiled plasmid pRO362 containing the same fis promoter region and a rho-independent transcription terminator that is expected to terminate transcription approximately 345 bp downstream of the fis P transcription start site. The reactions were performed in 20-μl mixtures (final volume) by combining 0.1 pmol of linear DNA or 0.01 pmol of supercoiled DNA with 0.5 pmol of RNA polymerase in transcription buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 100 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 100 μM dithiothreitol) and 25 mM potassium glutamate (when linear templates were used) or 200 mM KCl (when supercoiled DNA templates were used). The mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 5 min to allow formation of open complexes. RNA synthesis was then initiated from Tinear templates by addition of 10 μg of heparin per ml, 80 μM CTP, 80 μM GTP, 80 μM UTP, 4 μM ATP, and 2.5 μCi of [α-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol). For supercoiled templates, the same nucleotide mixture was added without the heparin. Transcripts were also synthesized in the presence of 80 μM ATP, 80 μM CTP, 80 μM GTP, 4 μM UTP, and 2.5 μCi of [α-32P]UTP to verify that the transcripts observed were not affected by the overall purine concentrations. The mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and the reactions were stopped by addition of 2.4 μl of stop buffer (5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.25 M EDTA) and 12 μl of formamide containing 0.05% bromophenol blue and 0.05% xylene cyanol. The samples were heated at 92°C for 2 min and separated on 6% polyacrylamide-7 M urea gels in TBE buffer. The gels were then subjected to autoradiography.

Nucleic acid sequencing.

DNA sequencing was performed with alkali-denatured double-stranded plasmid DNA by using Sequenase, version 2.0 (U.S. Biochemical Corp.) as specified by the supplier. RNA sequencing was performed in two steps. First, 20 μg of total cellular RNA was denatured at 65°C for 5 min in the presence of 7 pmol of primer labeled at the 5′ end with 32P, 400 μM dATP, 400 μM dCTP, 400 μM dGTP, and 400 μM dTTP in a 40-μl mixture and quickly frozen in a dry ice-ethanol bath. The extension and termination reactions were then performed together by combining 8 μl of the thawed RNA mixture with 1× SuperScript II buffer (Invitrogen Corp.), 8 mM dithiothreitol, 14 U of RNaseOUT (Invitrogen Corp.), 160 U of SuperScript II RT, and either 600 μM ddATP, 600 μM ddCTP, 600 μM ddGTP, or 600 μM ddTTP in 14 μl and incubating the preparation at 42°C for 30 min. The reactions were stopped by addition of 11.5 μl of a solution containing 90% formamide, 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 0.05% xylene cyanol, heated at 90°C for 3 min, and loaded on a 8% polyacrylamide-7 M urea gel for electrophoresis with TBE buffer. The gel was subjected to autoradiography.

RESULTS

fis expression in enteric bacteria.

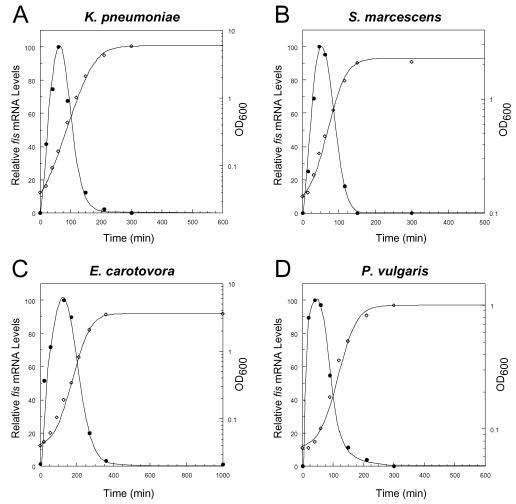

In order to explore the generality of the fis regulation pattern previously observed in E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (2, 38, 42), we examined the fis mRNA expression patterns generated from chromosomal fis genes of four additional enteric bacteria. Saturated cultures of K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris were diluted 100-fold in rich medium and grown for various lengths of time, after which cells were harvested and used for preparation of total RNA. Northern blot analysis, performed with RNA from comparable quantities of cells and the fis gene corresponding to the gene from each bacterium as the 32P-labeled DNA probe, showed that all four bacteria indeed exhibit a growth phase-dependent fis mRNA expression pattern (Fig. 1). The maximum mRNA levels occurred during the early logarithmic growth phase, and then the levels decreased as the cells proceeded through mid-logarithmic and late logarithmic growth phases. During stationary phase, fis mRNA was not detected.

FIG. 1.

Patterns of expression of fis mRNA in several enteric bacteria. Saturated cultures of K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris were diluted 100-fold in rich medium and grown at 37°C (or 32°C in the case of E. carotovora) with continuous shaking. Total RNA obtained from comparable quantities of cells (as determined by OD600) during the growth of the cultures was subjected to Northern blot analysis by using the corresponding bacterial fis genes as 32P-labeled probes. The relative fis mRNA levels (•) were measured by using a Storm 860 PhosphorImager and the ImageQuant software and are expressed relative to the maximum value in each set, which was assigned a value of 100%. Cell growth (⋄) was monitored by determining OD600.

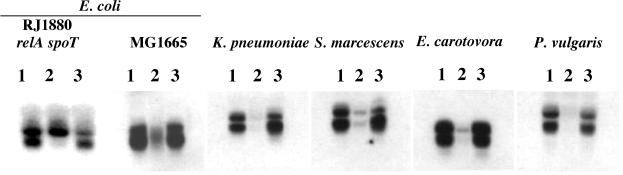

Northern blot and primer extension analyses previously demonstrated that the E. coli fis gene is also subject to negative regulation by stringent control (38, 50). Mutations in the −35 promoter region and in the G+C-rich discriminator DNA sequence located between the −10 region and the transcription start site altered stringent control of the promoter. To assess the general importance of this control mechanism in K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris, these bacteria were grown to early logarithmic growth phase in rich medium and then treated with 1 mg SeOH per ml, which was shown to induce starvation in E. coli (43). Northern blotting was performed as described above to compare the fis mRNA levels in SeOH-treated and nontreated cells (Fig. 2). Two transcripts were observed in the Northern blots that have been shown previously to be about 1,400 and 860 bases long (2). The size of the larger transcript corresponds to the distance from the fis promoter region to the end of the fis operon (Fig. 3A); the smaller transcript most likely results from processing of the larger transcript since significant promoter activity has not been identified in the yhdG regions that could account for this prominent signal (see below). SeOH treatment of E. coli cells (MG1655) resulted in a notable reduction in the fis mRNA level (Fig. 2, lane 2) compared to the level in the nontreated control (lane 3). However, in the relA spoT strain RJ1880, SeOH treatment did not result in an appreciable decrease in the fis mRNA level (lane 2) compared to the level in the nontreated culture (lane 3), as expected for a regulatory effect mediated by the stringent response. Curiously, only the larger transcript was observed in RJ1880 under SeOH-induced starvation conditions, suggesting that the putative mRNA processing event is prevented under these conditions. Treatment of K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris with SeOH resulted in considerable reductions in fis mRNA levels (lanes 2) compared to the levels in the nontreated controls (lanes 3), demonstrating that the expression of fis mRNA in these four enteric bacteria is subject to negative regulation by stringent control.

FIG. 2.

Effect of stringent control on fis mRNA levels in several enteric bacteria. Saturated cell cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 and grown to an OD600 between 0.15 and 0.20. Cell samples were removed for total RNA preparation (lanes 1), and the remainders of the cultures were divided in two parts. SeOH (1 mg/ml) was added to one half of each remaining culture, which was harvested after 30 min of growth for total RNA preparation (lanes 2). The other half of each culture received an equivalent volume of sterile H2O (as control) and was also harvested after 30 min of growth for total RNA preparation (lanes 3). Each lane was loaded with 10 μg of RNA. Northern blotting was performed by using 32P-labeled fis corresponding to each bacterium. The sources of bacterial RNA are indicated above the gels.

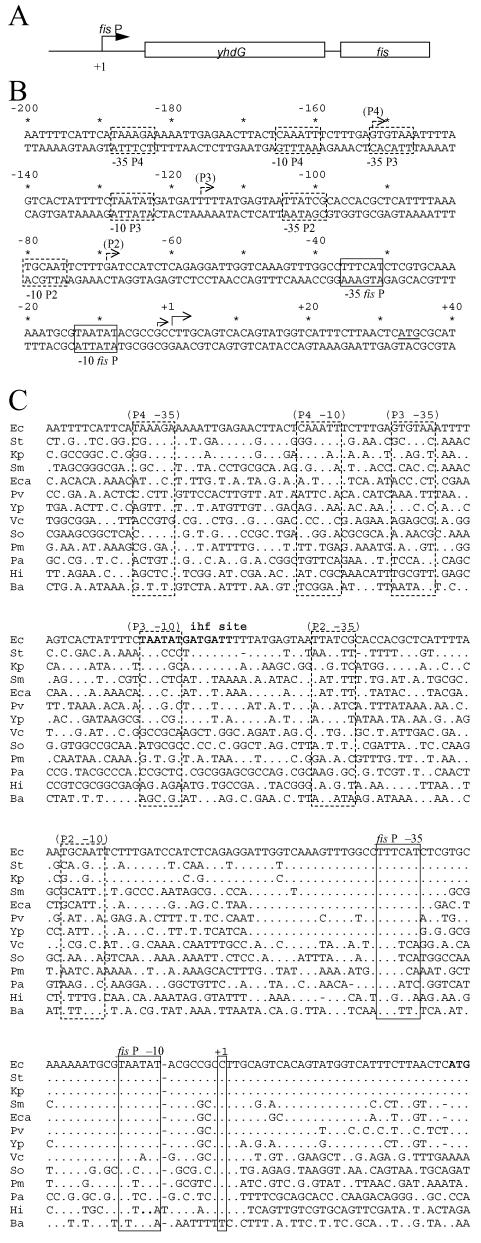

FIG. 3.

fis promoter region. (A) Schematic diagram of the fis operon. The rectangles represent open reading frames for fis and yhdG. The arrow represents the previously identified fis promoter (fis P). (B) DNA sequence of the E. coli fis promoter region from position −200 to position 40 relative to the predominant start site at position 1. The −35 and −10 promoter regions for fis P are enclosed in boxes, andthe solid arrows indicate the predominant and secondary transcription start sites for fis P. The dashed arrows indicate the positions of additional start sites that have also been reported for this region (31). The dashed boxes indicate the proposed −10 and −35 regions of these other promoters. The yhdG initiation codon is underlined, and the nucleotide position numbers relative to the fis P start site are indicated above the sequence both with numbers every 20 bp and with asterisks every 10 bp. (C) Comparison of fis promoter sequences of various bacteria. National Center for Biotechnology Information translated blastx was used to generate candidate fis operon sequences. Sequences preceding the fis operons were subjected to multiple-sequence alignment (10) and refined by hand. The DNA sequences shown are of E. coli (Ec) (GenBank accession no. NC000913), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (St) (NC003197), K. pneumoniae (Kp) (AF040380), S. marcescens (Sm) (AF040378), E. carotovora (Eca) (AF040381), P. vulgaris (Pv) (AF040379), Y. pestis (Yp) (NC004088), V. cholerae (Vc) (AE003852), S. oneidensis (So) (NC004347), P. multocida (Pm) (AE004439), P. aeruginosa (Pa) (AE004091), H. influenzae (Hi) (L42023), and B. aphidicola (Ba) (NC004061). The dots represent nucleotide matches with the E. coli sequence. Regions corresponding to the E. coli fis P −10 and −35 regions and its start site position (+1) are enclosed in solid boxes; regions corresponding to the putative P2, P3, and P4 promoters are enclosed in dashed boxes. A sequence pertaining to an ihf site is indicated by boldface type.

fis promoter region.

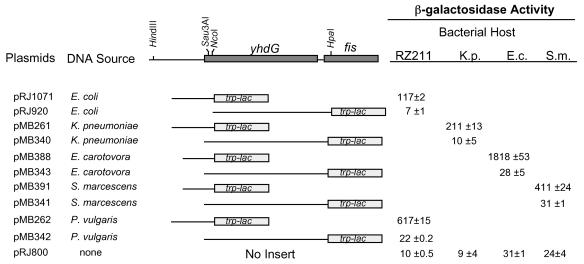

fis, yhdG, and DNA regions upstream of yhdG in K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris were previously cloned and sequenced (3). Sequences preceding the yhdG genes showed significant similarities with corresponding promoter sequences in E. coli, and transcriptional activity from these DNA regions could be detected when they were cloned in a plasmid and placed in an E. coli host. To verify that these sequences also displayed promoter function in their natural hosts and to determine if additional downstream promoters might contribute to the fis expression, we sought to transform the four bacterial species with plasmids carrying trp-lac fusions to their putative fis promoter regions or to the intervening DNA between the putative promoter region and fis. We succeeded in transforming K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, and E. carotovora but were unable to obtain P. vulgaris transformants. Hence, plasmids carrying the P. vulgaris fis operon regions were maintained and examined in E. coli strain RZ211. The results of β-galactosidase assays indicate that the DNA regions containing the entire yhdG gene and the initial eight codons of fis from E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and E. carotovora exhibited no transcriptional activity above the background levels observed with the pRJ800 vector alone, and negligible levels were detected from the corresponding regions from S. marcescens and P. vulgaris (Fig. 4). However, transcription activity was readily detected in the DNA regions containing 205 bp or less upstream of yhdG. These observations indicate that yhdG and fis are cotranscribed as an operon in all these bacteria from a promoter region that precedes yhdG (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 4.

Localization of the fis promoter region in several enteric bacteria. The plasmids indicated on the left were transformed into E. coli (RZ211), K. pneumoniae (K.p.), E. carotovora (E.c.), or S. marcescens (S.m.). The diagram at the top shows the fis operon that includes fis, yhdG, and DNA sequences upstream of yhdG. It is used as a reference to indicate the DNA regions of each bacterium (relative to yhdG and fis) that are fused to trp-lac in each plasmid. The restriction sites refer to sites in the E. coli sequence. Saturated cultures of cells carrying the plasmids were diluted 75-fold in rich medium, grown at 37°C (or 32°C in the case of E. carotovora) for 75 min, and used to measure β-galactosidase activity. The growth rates at the times that these measurements were taken were 2.4 doublings/h for E. coli and K. pneumoniae, 2.3 doublings/h for S. marcescens, and 2 doublings/h for E. carotovora. The values are averages ± standard deviations of three independent assays.

Single versus multiple fis promoters.

Primer extension analysis of the fis promoter regions in E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium previously identified a single promoter that initiated transcription approximately 33 nucleotides upstream of yhdG (2, 38, 42). A signal corresponding to transcription initiating at the same promoter was also identified in the analogous DNA regions of K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris when they were cloned on a plasmid and transformed in an E. coli strain (3). No other transcripts were detected from the DNA region preceding yhdG by as much as 300 bp. However, a recent report indicated that, on the basis of primer extension analysis and β-galactosidase assays, at least three additional promoters (referred to as P2, P3, and P4) were present upstream of the originally identified E. coli fis promoter (Fig. 3B) that contributed significantly to the fis expression, with P2 serving as a prominent promoter in vivo (31). Given the importance of these findings and the potential roles that such promoters might have in fis expression, we sought to examine more closely the activity of these promoters in vivo and in vitro, their contributions to fis expression, and the conservation of their sequences in other bacteria.

A comparison of the DNA sequence of the E. coli fis promoter region to the sequences of the corresponding regions in 12 other bacteria revealed a limited region of conservation from position −53 to position 21 relative to the E. coli fis P start site (Fig. 3C). This region is strongly conserved in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (99%), K. pneumoniae (99%), S. marcescens (88%), E. carotovora (89%), P. vulgaris (86%), and Yersinia pestis (84%). Although the levels of conservation in this region decrease to between 40 and 60% when several other bacteria are considered (Vibrio cholerae, Shewanella oneidensis, Pasteurella multocida, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus influenzae, and Buchnera aphidicola), the sequences representing the −35 and −10 promoter regions for fis P and the transcription initiation site are reasonably well conserved. However, the DNA region upstream of position −53, which includes the sequences proposed to serve as promoters P2, P3, and P4, shows a marked reduction in sequence conservation. The limited sequence conservation observed in the region designated the P3 −10 promoter region may reflect the position of an ihf binding site previously identified in E. coli and shown to be required for transcription stimulation of fis P (44). The higher percent conservation of fis P when compared to the designated upstream promoter sequences suggests that the latter are not essential to the conserved growth phase-dependent regulation and stringent control of fis observed among enteric bacteria.

Primer extension and S1 nuclease mapping.

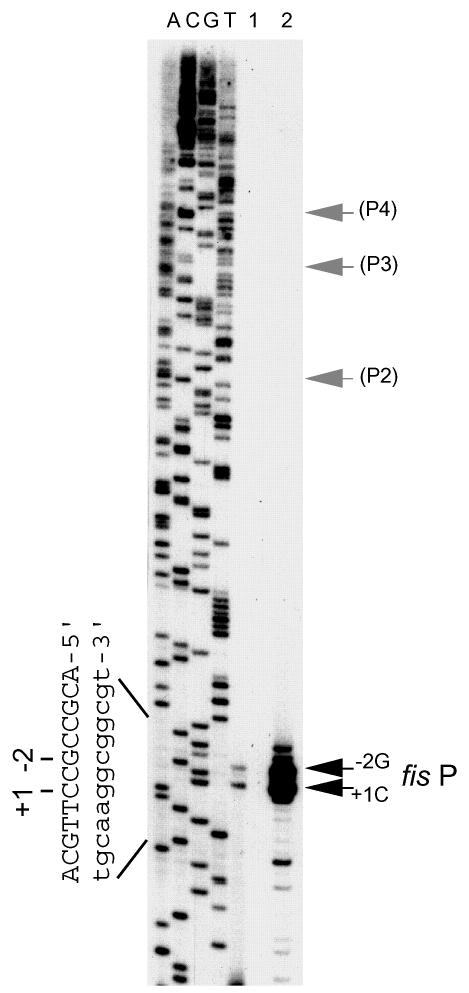

Concerned that our previous characterizations of the E. coli fis promoter region may have failed to identify salient promoters in addition to fis P, we sought to increase the rigor of our analysis. Primer extension analysis performed with total RNA from MG1655 cells grown to the early logarithmic phase reproducibly revealed only two transcription signals initiating at fis P (Fig. 5, lane 1). A primary signal initiated with CTP 33 nucleotides upstream of yhdG (designated position 1C), and a secondary signal initiated with GTP 2 nucleotides upstream of the primary signal (designated position −2G). To increase the sensitivity of detection of transcripts initiating in this region, we performed an identical primer extension analysis using RNA from MG1655 carrying the multicopy plasmid pRJ804 (Fig. 5, lane 2). This pUC18-based plasmid contains DNA sequences from position −762 to position 860 relative to the fis P transcription start site. The results show that the signals corresponding to the fis P transcripts initiating at positions 1C and −2G are greatly enhanced in the presence of this plasmid. However, we detected no additional signals that corresponded to transcription initiating from the previously designated P2, P3, and P4 promoters or any other promoter upstream of fis P. Such additional upstream promoter signals were not detected at any time during growth of the bacterial culture (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Primer extension analysis of the fis promoter region. Primer extension reactions were performed with primer oRO109 and 10 μg of total RNA from MG1655 (lane 1) or from MG1655 (lane 2) transformed with pRJ804 that was diluted 20-fold in LB medium from overnight cultures and grown at 37°C for 60 min. DNA sequencing reaction mixtures containing 32P-labeled oRO109 and pRJ804 as the template were electrophoresed in parallel in lanes A, C, G, and T (corresponding to the dideoxynucleotide used in each lane). The nucleotide sequence of the fis P transcription initiation region is indicated on the left. The lowercase letters indicate the nucleotides of the antisense strand read directly from the gel, and the uppercase letters indicate the sequence of the complementary sense strand. The positions of the fis P position 1 and −2 transcription initiation sites are indicated by black arrows, and the expected positions for the transcription initiation sites for promoters designated P2, P3, and P4 are indicated by gray arrows.

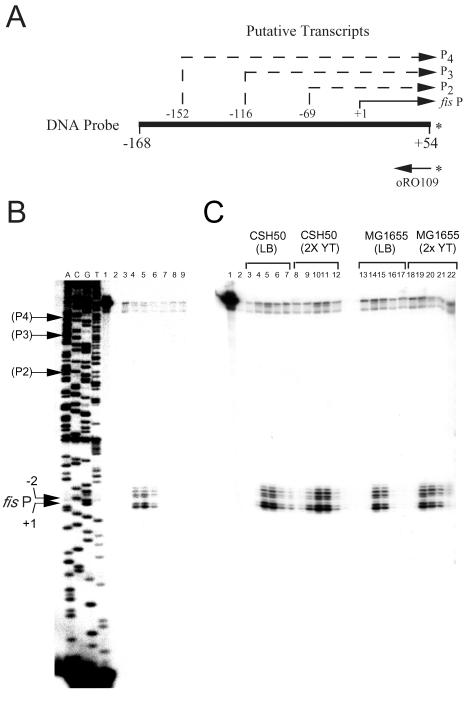

Two general concerns associated with the use of primer extension assays to map the positions of 5′ ends of transcripts are the potential for stable secondary RNA structures that may obstruct polymerization by the RT and the potential for secondary annealing sites for the short oligonucleotides used in these reactions that could yield false signals, a phenomenon often observed during PCR. The S1 nuclease mapping method (46), which does not rely on processive polymerization and utilizes a DNA probe that is considerably larger than the probes used for primer extension, overcomes these concerns. Thus, we performed S1 nuclease mapping using a single-stranded antisense DNA probe extending from position 54 to position −168 relative to the fis P transcription start site, in order to allow detection of RNA signals initiating at fis P, as well as promoters P2, P3, and P4 (Fig. 6A). Total RNA was isolated from MG1655 at various times after saturated cultures were diluted in LB medium and grown at 37°C, and the RNA was then subjected to S1 nuclease mapping (Fig. 6B). The results showed that there were two prominent sets of signals that exhibited a growth phase-dependent expression pattern (Fig. 6B, lanes 3 to 9). Their levels rapidly increased during the first 15 min of growth, decreased by 60 min, and continued to decrease thereafter. One set of signals mapped to positions 1 and 2 of the fis P transcription initiation region, and the other set of signals corresponded to positions −2 through −5 of the same promoter. The former set of signals was more intense than the latter set. These results are in very good agreement with the results of our primer extension analysis. Clusters of bands that differ by increments of one nucleotide are commonly observed when the S1 nuclease mapping method is used (6, 22, 27, 28). No additional signals were observed upstream of fis P that corresponded to transcripts initiating from the promoters designated P2, P3, and P4, even after long periods of X-ray film exposure.

FIG. 6.

S1 nuclease mapping of the fis promoter transcripts. (A) Schematic diagram of the single-stranded DNA probe used in S1 nuclease mapping. The horizontal line represents the DNA probe extending from position −168 to position 54 relative to fis P. The arrow below this line represents the oRO109 primer used to generate the DNA probe. The positions of the 5′ 32P label in both the primer and the resulting probe are indicated by asterisks. The relative position of the transcription start site for fis P is indicated above the line by a solid arrow, and the start site positions for the additional putative promoters P2, P3, and P4 are represented by dashed arrows. (B) S1 nuclease mapping of transcripts arising from the fis promoter region. A saturated culture of MG1665 was diluted 75-fold in LB medium, grown at 37°C, and harvested at various times for total RNA preparation. S1 nuclease mapping was performed with the DNA probe shown in panel A and 10 μg of total RNA. The resulting products were separated on an 8% polyacrylamide-7 M urea gel and subjected to autoradiography. Lanes A, C, G, and T contained the products of dideoxy DNA sequencing reactions for the fis promoter region performed with pRJ1028 as the template and primer oRO109 that was labeled at the 5′ end with 32P. Lane 1, untreated DNA probe; lane 2, DNA probe treated with S1 nuclease in the absence of RNA; lanes 3 through 9, S1 nuclease mapping performed with total RNA from MG1655 after growth at 37°C in LB medium for 0 min (lane 3), 5 min (lane 4), 15 min (lane 5), 60 min (lane 6), 150 min (lane 7), 300 min (lane 8), and 22 h (lane 9). The fis P start site positions identified based on primer extension assays and the start site positions of previously reported promoters P2, P3, and P4 are indicated on the left by arrows. (C) Comparison of S1 nuclease mapping results by using total RNA from strains CSH50 and MG1655 grown in either LB or 2X YT medium. Saturated cultures of each strain were diluted 75-fold in either LB or 2X YT medium and grown at 37°C. Cells were harvested at various times for total RNA preparation. The strains and growth media used are indicated above the lanes. S1 nuclease treatment was performed as described above. Lane 1, untreated DNA probe; lane 2, S1 nuclease-treated DNA probe in the absence of RNA; lanes 3 through 22, S1 nuclease mapping performed with total RNA from cells grown for 1 min (lanes 3, 8, 13, and 18), 15 min (lanes 4, 9, 14, and 19), 40 min (lanes 5, 10, 15, and 20), 60 min (lanes 6, 11, 16, and 21), or 150 min (lanes 7, 12, 17, and 22).

We considered whether strain differences, the growth medium used, or the methods of RNA preparation used may have accounted for our inability to detect transcripts initiating at P2 through P4. Thus, we performed S1 nuclease mapping of fis mRNA in CSH50 strains grown in 2X YT medium, as previously described for identification of promoters P2 through P4 (31), and compared the results with those obtained for CSH50 grown in LB medium or for MG1655 grown in 2X YT or LB medium. The results showed that the same set of transcripts corresponding to fis P were made in both strains, whether they were grown in LB or 2X YT medium (Fig. 6C). In addition, the method of RNA preparation (hot acid phenol versus Qiagen RNeasy RNA purification method) made no difference in the results (data not shown). A growth phase-dependent expression pattern was exhibited by these transcripts in all cases, and there were only small variations in the timing of the expression pattern. Thus, our results clearly show that fis P is the sole promoter for which transcription activity can be detected in vivo by either primer extension or S1 nuclease mapping assay.

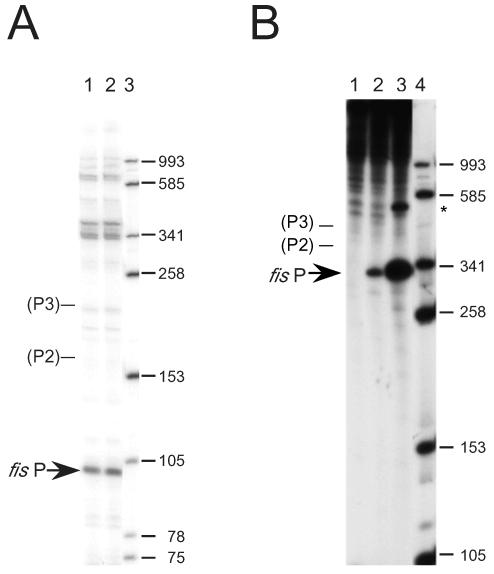

In vitro transcription from the fis promoter region.

In vitro transcription was used to detect 32P-labeled RNA synthesized from the fis promoter region from position −168 to position 83, which contained the complete sequences for fis P and the putative P2 and P3 promoters (Fig. 7). A 283-bp linear DNA template was used, so that the expected sizes for transcripts initiating at fis P, P2, and P3 were 103, 172, and 219 bases, respectively. A prominent 103-nucleotide signal was observed, whereas signals corresponding to 172 and 219 nucleotides were not discerned among a number of very-low-intensity signals (Fig. 7A). When the same DNA region was transcribed from a supercoiled DNA template (pRO362), a noticeable signal was observed at an approximate size expected for transcripts initiating at fis P and terminating at a rho-independent terminator located about 345 bases downstream from fis P (Fig. 7B, lane 2). This signal was not observed when the vector lacking the fis promoter region was used as the template (lane 1). In order to more confidently identify this transcript, we cloned a similar fis promoter region containing an up-promoter mutation in the fis P −10 region that created a perfect match with the consensus sequence (TATAAT) in pRO468. Transcription from equivalent quantities of this template gave a much higher signal intensity for the same transcript produced from the wild-type fis P region (lane 3), demonstrating that this signal originated from the fis promoter. Signals whose sizes corresponded to the sizes of transcripts originating from P2 (409 bases) and P3 (456 bases) were not observed. Thus, the results of our in vitro transcription experiments in which linear or supercoiled templates were used indicate that fis P is the predominant or sole promoter in the region from position −168 to position 83.

FIG. 7.

In vitro transcription of the fis promoter. (A) Runoff transcription reactions with a 283-bp DNA fragment containing the DNA sequences from position −168 to position 83 relative to the fis P transcription start site and an additional 20 bp downstream of position 83 originating from the vector DNA. This fragment contains the sequences attributed to fis P, as well as promoters P2 and P3. Transcripts from duplicate reaction mixtures were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide-7 M urea denaturing gel (lanes 1 and 2) and subjected to autoradiography. Lane 3 contained denatured DNA size standards, whose sizes (in numbers of nucleotides) are indicated on the right. The position of the 103-nucleotide transcript signal corresponding to fis P is indicated on the left by an arrow. The expected positions of transcripts originating from the putative promoters P2 and P3, based on their expected sizes (172 and 219 nucleotides, respectively), are also indicated. (B) In vitro transcription from fis P on a supercoiled plasmid. Gel electrophoresis was performed as described above. Lane 1, results with pTP435 (vector only); lane 2, results with pRO362 carrying the wild-type fis promoter region from position −168 to position 83; lane 3, results with pRO468 carrying a perfect match with the −10 promoter region in fis P; lane 4, DNA size standards. The position of the signal corresponding to the transcript originating from fis P and terminating at the primary rho-independent terminator is indicated on the left by an arrow. The expected positions of transcripts originating from promoters P2 and P3 are also indicated. The asterisk on the right indicates the position of a signal from pRO468 corresponding to a fraction of fis P transcripts terminating at a second rho-independent terminator on the vector.

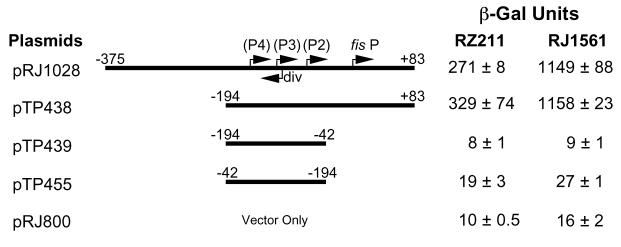

Deletion of fis P abolishes transcription from the fis promoter region.

Deletion of the fis promoter (or P1) was reported to result in a prominent increase in transcription from the putative upstream promoters P2 through P4 on the basis of β-galactosidase assays, presumably because their expression is partially occluded by fis P (31). To examine this effect, we cloned the DNA region from position −194 to position −42 next to the (trp-lac)W200 fusion in pTP439, such that expression of trp-lac would be under control of the putative promoters P2, P3, and P4 in the absence of fis P. We compared the transcriptional activity in vivo to that generated from pTP438 and pRJ1028, which contain a similar trp-lac fusion to the fis P region from position −194 to position 83 and from position −375 to position 83, respectively (Fig. 8). Plasmids pRJ1028 and pTP438 produced 1,149 and 1,158 β-galactosidase units, respectively, in fis strain RJ1561, demonstrating that there was a significant level of transcriptional activity in these DNA constructs compared to the level in the vector control. The levels in RZ211 cells were lower, 271 and 329 U, respectively, which is consistent with an effect attributed to Fis repression (2, 38, 44). The deletion of fis P in pTP439, which leaves the sequences for P2, P3, and P4 intact, caused transcription activity to decrease to levels comparable to those of the promoterless plasmid pRJ800 in both RZ211 and RJ1561 cells. No transcription was detected from this construct irrespective of the growth medium used (2X YT or LB medium) or the growth phase chosen to measure β-galactosidase activity (data not shown). We also cloned the fis P region from position −194 to position −42 within pTP455 in the orientation opposite that in pTP439 to examine if transcription could be detected from a divergent promoter (Fig. 8). A very low level of transcription was detected above the level of transcription of the pRJ800 control in both RZ211 and RJ1561, suggesting that the region from position −194 to position −42 harbors a weak divergent promoter.

FIG. 8.

Deletion analysis of the fis promoter region. The fis promoter regions preceding the trp-lac fusion in pRJ1028, pTP438, pTP439, and pTP455 are shown, and their upstream and downstream end points are indicated relative to the fis P transcription start site. Plasmid pRJ800, which lacks the fis promoter region, was used as a control. Saturated cultures of RZ211 or RJ1561 cells carrying these plasmids were diluted 50-fold in 2X YT medium, grown at 37°C for 75 min, and assayed for β-galactosidase (β-Gal) activity. The results, shown on the right, are averages ± standard deviations of three independent assays.

Effect of reaction conditions on primer extended signals.

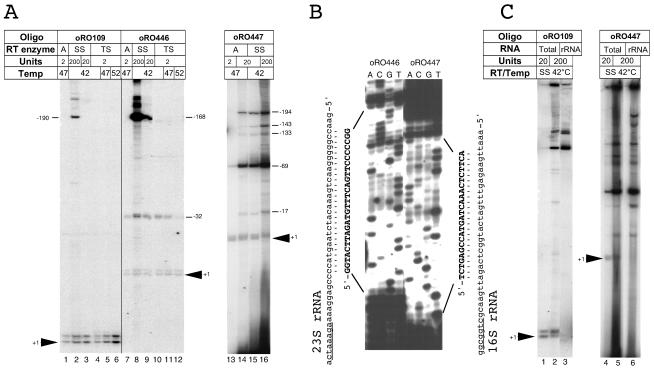

Given the striking discrepancy between our observations regarding the existence of a single promoter (fis P) and the previously reported observations regarding the existence of multiple promoters P1, P2, P3, and P4 involved in fis expression (31), we examined the possibility that differences in the conditions used in the primer extension reactions could account for the conflicting observations. Transcripts corresponding to P2, P3, and P4 were detected in primer extension assays by using SuperScript II RT according to the manufacturer's recommendations. We also employed this enzyme together with primer oRO109 and 10 μg of total RNA from MG1655 grown for 40 min in LB medium at 37°C. Under these conditions we observed the signals previously identified as fis P initiation signals at positions +1 and −2. In addition, two prominent larger-size signals were observed (Fig. 9A, compare lanes 1 and 2). The sizes of these additional signals, however, did not correspond to the sizes of any of the transcripts previously reported for P2, P3, or P4. Rather, they corresponded to an initiation event somewhere upstream of position −180 relative to the fis P start site. We noticed that the procedure recommended by the supplier (Invitrogen Corp.) called for a large amount of SuperScript II RT (200 U) in the reaction mixture, and we hypothesized that such conditions might facilitate extension of secondary priming events produced by the 17-mer oRO109. Indeed, when the amount of SuperScript II RT in the reaction mixture was reduced by as much as 10-fold (to 20 U), we detected only the fis P position +1 and −2 transcript signals (Fig. 9, lane 3). We also used Thermoscript RT, which is a modified version of AMV RT that exhibits increased activity at higher temperatures and can potentially reduce artifacts caused by secondary priming events. When 2 U of Thermoscript RT was used to extend oRO109 at 42, 47, and 52°C (lanes 4 to 6), we detected only the fis P signals for positions +1 and −2 at all temperatures, and the more prominent signals were detected at 52°C (lane 6). Thus, comparable results were obtained with three versions of the RT enzyme provided that their concentrations were not excessively high.

FIG. 9.

Examination of primer extension assay conditions. (A) Effects of reaction conditions and primers on the results of primer extension analysis of the fis promoter transcripts. Lanes 1 through 16 contained the products of primer extension reactions performed with 10 μg of total cellular RNA isolated from MG1655 which had been grown for 40 min in LB medium at 37°C following 75-fold dilution from a saturated culture. Reactions were performed with the following primers that were labeled at the 5′ end with 32P: oRO109 (lanes 1 through 6), oRO446 (lanes 7 through 12), and oRO447 (lanes 13 through 16). The reactions were performed with 2 U of AMV RT at 47°C (lanes 1, 7, and 13), 20 U of AMV RT at 47°C (lane 14), 200 U of SuperScript II RT at 42°C (lanes 2, 8, and 16), 20 U of SuperScript II RT at 42°C (lanes 3, 9, and 15), and 2 U of AMV Thermoscript RT at either 42°C (lanes 4 and 10), 47°C (lanes 5 and 11), or 52°C (lanes 6 and 12). The arrowheads labeled +1 indicate the positions of the fis P signals based on their gel migration relative to that of DNA sequencing products from the fis promoter region electrophoresed in parallel on the same gel (data not shown). The presumed start site positions of additional signals observed (relative to fis P) are also indicated on the sides of the gel according to the primers used in each set of reactions. Abbreviations: Oligo, oligonucleotide; A, AMV RT; SS, SuperScript II RT; TS, Thermoscript RT. (B) Dideoxy DNA sequence synthesized from RNA by using SuperScript II RT and primers oRO446 or oRO447. The sequencing reaction mixtures loaded in lanes A, C, G, and T contained the A, C, G, and T dideoxynucleotides, respectively. A portion of the sequence is shown in uppercase boldface letters on each side of the gel, and lowercase letters indicate 23S RNA and 16S RNA sequences that perfectly complemented the sequences obtained with oRO446 or oRO447, respectively. The underlined sequences (near the bottom) are regions of 23S and 16S rRNA that complement the 3′ regions of primers oRO446 and oRO447, respectively. (C) Primer extension signals obtained with rRNA. Primer extension reactions were performed with 5 μg of total RNA obtained from MG1655 grown and harvested as described above (lanes 1, 2, 4, and 5) or with 4 μg of purified rRNA (lanes 3 and 6) by using primer oRO109 (lanes 1, 2, and 3) or oRO447 (lanes 4, 5 and 6) and either 20 U (lanes 1 and 4) or 200 U (lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6) of SuperScript II RT. The arrowheads indicate the position of the fis P transcript signal.

We tested two additional primers, oRO446 and oRO447, that annealed to different positions on the fis mRNA. When 2 U of AMV RT was used together with oRO446, the two transcript signals initiating from fis P at positions +1 and −2 were observed, as was one other weak signal whose size corresponded to the size of a transcript initiating at position −32 (Fig. 9A, lane 7). When 200 U of SuperScript II RT was used, the same signals were observed together with several strong signals that were much larger (lane 8). Again, none of these signals corresponded to a transcript initiating at P2, P3, or P4. The strongest signals corresponded to a transcript initiating at position −168. When only 20 U of SuperScript II RT was used, there were large decreases in the intensities of these larger signals, and there were no appreciable decreases in the intensities of the signals that mapped to positions +1 and −2 or to position −32 (lane 9), which is consistent with the notion that the larger signals might have resulted from secondary primer-annealing events that were efficiently extended when very high concentrations of RT were used. When Thermoscript RT was used together with primer oRO446, the signals for positions +1 and −2 were observed for extension reactions performed at 42, 47, and 52°C. The position −32 signal was observed for reactions performed at 42 and 47°C but not for reactions performed at 52°C (lanes 10, 11, and 12), suggesting that the position −32 signal resulted from an oRO446 annealing event whose specificity was lower than that of the position +1 and −2 signals. Primer oRO447 also gave the signals corresponding to initiation at fis P under all conditions tested (lanes 13 to 16). With 2 U of AMV RT, the signals corresponding to fis P were the most prevalent signals (lane 13). When 20 U of AMV RT or 20 U of SuperScript II RT was used, a prominent signal corresponding to initiation at position −69 and several additional signals for initiation at positions −17, −133, −143, and −194 were also detected (lanes 14 and 15). The size of the signal for position −69 resembled the size of the signal previously reported for initiation at P2 when the same primer was used (31). When 200 U of SuperScript II RT was used, the five additional signals became even more intense, and several additional weak signals also appeared (lane 16). Thus, we consistently observed signals corresponding to fis P when we used three different primers and different RT concentrations, while multiple additional signals mapping to variable positions appeared when high concentrations of RT were used.

To gain further insight into the identities of some of the signals obtained with primers oRO446 and oRO447 when high RT concentrations were used, we performed RNA sequencing reactions using 10 μg of total mRNA from MG1665 grown to the early logarithmic growth phase in LB medium (Fig. 9A) and 160 U of SuperScript II RT. Much of the sequence information obtained was scrambled, suggesting that several different RNA sequences were simultaneously detected with the same primer. Nevertheless, certain regions of the sequencing gel allowed us to decipher a clear sequence (Fig. 9B). The oRO446 primer gave a sequence that perfectly complemented a region of the 23S rRNA, while the oRO447 primer gave a sequence that perfectly complemented a region of the 16S rRNA. A short stretch of six or seven bases was identified on the 23S or 16S rRNA that complemented the 3′ end of the corresponding primer used in each case. This demonstrated that oRO446 and oRO447 partially annealed to certain regions of 23S and 16S rRNA, respectively, serving as primers in the reactions. To confirm these observations, purified rRNA was also used in primer extension reactions with 200 U of SuperScript II RT and primer oRO109 or oRO447. The results showed that most of the prominent signals detected when total cellular RNA was used were also detected in reactions with purified rRNA (Fig. 9C, compare lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6). However, the signals corresponding to initiation at fis P were detected only when total cellular RNA was used in the primer extension reactions with either 20 or 200 U of SuperScript II RT (lanes 1, 2, 4, and 5). Together, these results indicate that prominent signals, other than those for fis P, obtained by this assay when high concentrations of RT were used were the result of secondary priming events at rRNAs and possibly other RNA targets.

DISCUSSION

Conservation of growth phase-dependent regulation and stringent control of fis.

We have shown that the growth phase-dependent fis expression pattern previously observed in E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (2, 35, 38, 42) in response to a nutrient upshift is also observed in four other enteric bacteria, K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris. In each of the four enteric bacteria, the relative fis mRNA levels originating from the chromosomal fis genes rapidly increased in response to a nutrient upshift, reached a peak during early logarithmic growth phase, decreased to low values during mid-logarithmic and late logarithmic growth, and became undetectable during stationary phase. The results of Western blot analysis showed that the Fis protein levels exhibited a similar growth phase-dependent pattern of expression in each of these bacteria (data not shown). Under induced starvation conditions, E. coli fis is negatively regulated by stringent control (38, 50). We obtained evidence that the same fis regulatory mechanism also operates in K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris. Thus, the cis- and trans-acting factors involved in these two regulatory processes are likely to be preserved in these bacteria. The conserved tight connection between the nutritional state of the cells and the control of fis expression suggests that an important function of Fis is to rapidly regulate cellular processes in response to abrupt changes in the nutritional environment. The role of Fis in stimulating transcription of ribosomal and tRNA genes (33, 34, 45) illustrates its involvement in optimizing the translational machinery in response to a nutritional upshift, a function that is probably conserved in all these bacteria, particularly since their Fis protein sequences are ≥98% identical (3). The ability of Fis to interact with its various DNA targets depends on both its changing intracellular concentration and the precise DNA sequence of each Fis binding site. Thus, Fis-dependent processes involving low-affinity binding sites are more likely to be highly sensitized to the nutritional quality of the environment.

The yhdG-fis operon structure is preserved in all four enteric bacteria examined. Little or no transcription activity was detected within the DNA region that includes yhdG and the intergenic region between yhdG and fis in K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, or P. vulgaris, while significant promoter activity was detected in the DNA regions preceding yhdG in all four species. A sequence comparison of the regions preceding yhdG showed that the E. coli fis promoter region from about position −53 to position 20 is very highly conserved among seven enteric bacteria. More specifically, the −35 and −10 promoter regions, the transcription start site, and the GC-rich discriminator region, which were shown to be required for either growth phase-dependent regulation of fis or its response to stringent control in E. coli (38, 50), are preserved in these bacteria, suggesting that the same promoter elements contribute similarly to regulation of fis expression in enteric bacteria. These elements are also generally conserved, albeit to a smaller extent, among six additional nonenteric bacteria, and it will be interesting to determine how fis is regulated in these organisms.

A single promoter (fis P) is responsible for expression and regulation of the fis operon in E. coli.

Results of β-galactosidase assays demonstrated that the E. coli fis promoter region is located upstream of yhdG (Fig. 4) (2). Because multiple promoters were identified recently in this region that contribute substantially to fis expression (31), we sought to detect these promoters in order to weigh their contributions to fis expression and regulation. However, the results of the primer extension analysis of both chromosomal and multicopy plasmid-derived transcripts in vivo, S1 nuclease mapping of chromosomally derived transcripts, and in vitro transcription of linear or supercoiled templates all clearly identified fis P as the only promoter contributing to the expression of fis in E. coli. We also examined the notion that the expression of putative upstream promoters may be repressed by fis P. However, in our hands, the complete deletion of fis P, which leaves the fis promoter region from position −42 to position −194 intact, resulted in no detectable promoter activity in vivo (on the basis of β-galactosidase assays) that could contribute to fis expression. Therefore, our results led us to conclude that in the region upstream of yhdG there is only one promoter, fis P, that significantly contributes to expression of the fis operon in E. coli.

The striking discrepancy between our detection of a single fis promoter and the detection of multiple fis promoters reported previously (31) deserved further attention. Our investigation of the primer extension conditions employed in the previous studies revealed that a large amount of SuperScript II RT in the reaction mixtures (as recommended by the manufacturer) is not suitable for reliable mapping of transcription initiation sites. Such conditions result in misleading multiple signals with various intensities that arise from extension of primers annealed to RNA targets with reduced specificity. In particular, we demonstrated that these conditions result in prominent signals originating from secondary primer annealing to 16S or 23S rRNA in addition to the signals originating at fis P. On the other hand, a substantial reduction in the RT concentration prevented detection of signals arising from reduced annealing specificity, while it allowed detection of the transcripts initiating at fis P. rRNAs are easy targets of partial annealing events because of their very high concentrations in the total cellular RNA. However, secondary annealing events at mRNAs might also be detected if the interactions are sufficiently stable. The problem of secondary annealing events can also be encountered when the primer extension procedure is used as the method of identifying transcripts generated in vitro. Therefore, confirmation by the more direct method of synthesizing labeled transcripts is essential.

When lower levels of enzyme are used (e.g., 1 U per 10 μg of total RNA), the kinetics of ternary complex formation (involving the primer, RNA, and enzyme) may be more strongly dependent upon the availability of longer-lived primer-RNA hybrids, as expected for the completely annealed primer. Thus, care should be taken to optimize the enzyme concentration in primer extension assays aimed at mapping specific transcription start sites, despite the manufacturer's recommendations. Even the choice of primers can be critical for identification of specific transcripts. Use of RT variants that are active at higher temperatures can assist in destabilizing incomplete hybrids. Finally, S1 nuclease mapping should be employed as an independent confirmatory approach. Our primer extension conditions, in which low concentrations of RT were used, were found to be much more reliable for mapping specific transcription initiation sites than the conditions used to detect multiple promoters in the fis promoter region (31), and the results were in excellent agreement with the results of our S1 nuclease mapping, in vitro transcription, and β-galactosidase assay experiments. Thus, we firmly concluded that fis P is the only promoter in the region preceding yhdG that significantly contributes to the transcription of fis.

We detected a low level of divergent transcription activity that originates somewhere upstream of fis P, since we observed it in a promoter region lacking fis P. Previously, an RNA polymerase binding site upstream of fis P from position −137 to position −68 was detected (2) that was subsequently reported to serve as a divergent promoter designated Pdiv (32). However, we have not been able to detect an in vivo transcript that maps to this putative promoter when either primer extension or S1 nuclease mapping is used with RNA obtained from cells in either the logarithmic or stationary growth phase (data not shown). The very low level of divergent transcription detected by the β-galactosidase assay suggests that the contribution of this transcription in vivo has little significance, especially since there are no open reading frames that can be expressed from this promoter in over 6 kb of DNA. It has previously been observed that, while deletion or mutation of an ihf binding site centered at position −114 resulted in a three- to fourfold reduction in fis P transcription, deletion of the putative divergent promoter had no additional effect on the transcription of fis P (44).

The strong conservation of the fis promoter sequence among enteric bacteria, which contrasts with the poor conservation of upstream sequences that include P2, P3, P4, and Pdiv, suggests that fis P is probably the principal if not the sole promoter responsible for fis expression and regulation in the other species studied. The fis P transcription initiation region is largely comprised of C and U in the promoters examined, suggesting that transcription initiation with a pyrimidine is a conserved property of this promoter. This is significant because it has been observed that the growth phase-dependent regulation of fis P in E. coli is strongly linked to the use of CTP or UTP as the primary initiation nucleotide (50, 51). The GC-rich discriminator region between the −10 promoter region and the transcription start site, which has been observed to be linked to the response to stringent control (38, 50), is also strongly conserved in these bacteria. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of the regulation of fis expression in response to changes in the nutritional state must focus on the properties of the unique fis promoter.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. C. Johnson, R. L. Gourse, A. K. Chatterjee, and R. A. Bender for providing strains used in this work.

This work was supported by funds from Public Health Service grant GM52051.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali Azam, T., A. Iwata, A. Nishimura, S. Ueda, and A. Ishihama. 1999. Growth phase-dependent variation in protein composition of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. J. Bacteriol. 181:6361-6370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball, C. A., R. Osuna, K. C. Ferguson, and R. C. Johnson. 1992. Dramatic changes in Fis levels upon nutrient upshift in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 174:8043-8056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beach, M. B., and R. Osuna. 1998. Identification and characterization of the fis operon in enteric bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 180:5932-5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop, A. C., J. Xu, R. C. Johnson, P. Schimmel, and V. de Crecy-Lagard. 2002. Identification of the tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase family. J. Biol. Chem. 277:25090-25095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosch, L., L. Nilsson, E. Vijgenboom, and H. Verbeek. 1990. FIS-dependent trans-activation of tRNA and rRNA operons of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1050:293-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd, C. H., and J. W. Gober. 2001. Temporal regulation of genes encoding the flagellar proximal rod in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 183:725-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bustos, S. A., and R. F. Schleif. 1993. Functional domains of the AraC protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90:5638-5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Case, C. C., S. M. Roels, J. E. Gonzalez, E. Simons, and R. Simons. 1988. Analysis of the promoters and transcripts involved in IS10 anti-sense transcriptional RNA control. Gene 72:219-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuang, S. E., D. L. Daniels, and F. R. Blattner. 1993. Global regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:2026-2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corpet, F. 1988. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:10881-10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez-Gil, G., P. Bringmann, and R. Kahmann. 1996. FIS is a regulator of metabolism in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 22:21-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottesman, S. 1984. Bacterial regulation: global regulatory networks. Annu. Rev. Genet. 18:415-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartz, D., D. S. McPheeters, R. Traut, and L. Gold. 1988. Extension inhibition analysis of translation initiation complexes. Methods Enzymol. 164:419-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolb, A., S. Busby, H. Buc, S. Garges, and S. Adhya. 1993. Transcriptional regulation by cAMP and its receptor protein. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62:749-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kucherer, C., H. Lother, R. Kolling, M. A. Schauzu, and W. Messer. 1986. Regulation of transcription of the chromosomal dnaA gene of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 205:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landini, P., L. I. Hajec, and M. R. Volkert. 1994. Structure and transcriptional regulation of the Escherichia coli adaptive response gene aidB. J. Bacteriol. 176:6583-6589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindahl, T., B. Sedgwick, M. Sekiguchi, and Y. Nakabeppu. 1988. Regulation and expression of the adaptive response to alkylating agents. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 57:133-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Little, J. W. 1993. LexA cleavage and other self-processing reactions. J. Bacteriol. 175:4943-4950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loewen, P. C., I. von Ossowski, J. Switala, and M. R. Mulvey. 1993. KatF (sigma S) synthesis in Escherichia coli is subject to posttranscriptional regulation. J. Bacteriol. 175:2150-2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magasanik, B. 2000. Global regulation of gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97:14044-14045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin, R. G., and J. L. Rosner. 1997. Fis, an accessorial factor for transcriptional activation of the mar (multiple antibiotic resistance) promoter of Escherichia coli in the presence of the activator MarA, SoxS, or Rob. J. Bacteriol. 179:7410-7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Master, S., T. C. Zahrt, J. Song, and V. Deretic. 2001. Mapping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis katG promoters and their differential expression in infected macrophages. J. Bacteriol. 183:4033-4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCann, M. P., C. D. Fraley, and A. Matin. 1993. The putative sigma factor KatF is regulated posttranscriptionally during carbon starvation. J. Bacteriol. 175:2143-2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, J. F. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 25.Miller, J. F., W. J. Dower, and L. S. Tompkins. 1988. High-voltage electroporation of bacteria: genetic transformation of Campylobacter jejuni with plasmid DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 85:856-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Minagawa, S., H. Ogasawara, A. Kato, K. Yamamoto, Y. Eguchi, T. Oshima, H. Mori, A. Ishihama, and R. Utsumi. 2003. Identification and molecular characterization of the Mg2+ stimulon of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:3696-3702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohr, C. D., J. K. MacKichan, and L. Shapiro. 1998. A membrane-associated protein, FliX, is required for an early step in Caulobacter flagellar assembly. J. Bacteriol. 180:2175-2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morigen, E. Boye, K. Skarstad, and A. Lobner-Olesen. 2001. Regulation of chromosomal replication by DnaA protein availability in Escherichia coli: effects of the datA region. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1521:73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagai, H., H. Yuzawa, and T. Yura. 1991. Interplay of two cis-acting mRNA regions in translational control of sigma 32 synthesis during the heat shock response of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 88:10515-10519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasser, W., M. Rochman, and G. Muskhelishvili. 2002. Transcriptional regulation of fis operon involves a module of multiple coupled promoters. EMBO J. 21:715-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nasser, W., R. Schneider, A. Travers, and G. Muskhelishvili. 2001. CRP modulates fis transcription by alternate formation of activating and repressing nucleoprotein complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:17878-17886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nilsson, L., and V. Emilsson. 1994. Factor for inversion stimulation-dependent growth rate regulation of individual tRNA species in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:9460-9465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nilsson, L., A. Vanet, E. Vijgenboom, and L. Bosch. 1990. The role of FIS in trans activation of stable RNA operons of E. coli. EMBO J. 9:727-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nilsson, L., H. Verbeek, E. Vijgenboom, C. van Drunen, A. Vanet, and L. Bosch. 1992. FIS-dependent trans activation of stable RNA operons of Escherichia coli under various growth conditions. J. Bacteriol. 174:921-929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ninfa, A. J. 1996. Regulation of gene transcription by extracellular stimuli, p. 1246-1262. In F. C. Neidhardt, J. L. Ingraham, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. American Society for Microbiology Press, Washington, D.C.

- 37.Ninfa, A. J., and B. Magasanik. 1986. Covalent modification of the glnG product, NRI, by the glnL product, NRII, regulates the transcription of the glnALG operon in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 83:5909-5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ninnemann, O., C. Koch, and R. Kahmann. 1992. The E. coli fis promoter is subject to stringent control and autoregulation. EMBO J. 11:1075-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohnishi, K., K. Kutsukake, H. Suzuki, and T. Lino. 1992. A novel transcriptional regulation mechanism in the flagellar regulon of Salmonella typhimurium: an antisigma factor inhibits the activity of the flagellum-specific sigma factor, sigma F. Mol. Microbiol. 6:3149-3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orsini, G., M. Ouhammouch, J. P. Le Caer, and E. N. Brody. 1993. The asiA gene of bacteriophage T4 codes for the anti-sigma 70 protein. J. Bacteriol. 175:85-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osuna, R., S. E. Finkel, and R. C. Johnson. 1991. Identification of two functional regions in Fis: the N-terminus is required to promote Hin-mediated DNA inversion but not lambda excision. EMBO J. 10:1593-1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osuna, R., D. Lienau, K. T. Hughes, and R. C. Johnson. 1995. Sequence, regulation, and functions of fis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 177:2021-2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pokholok, D. K., M. Redlak, C. L. Turnbough, Jr., S. Dylla, and W. M. Holmes. 1999. Multiple mechanisms are used for growth rate and stringent control of leuV transcriptional initiation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:5771-5782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pratt, T. S., T. Steiner, L. S. Feldman, K. A. Walker, and R. Osuna. 1997. Deletion analysis of the fis promoter region in Escherichia coli: antagonistic effects of integration host factor and Fis. J. Bacteriol. 179:6367-6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ross, W., J. F. Thompson, J. T. Newlands, and R. L. Gourse. 1990. E. coli Fis protein activates ribosomal RNA transcription in vitro and in vivo. EMBO J. 9:3733-3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook, J. E., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 47.Schell, M. A. 1993. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:597-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stock, J. B., A. J. Ninfa, and A. M. Stock. 1989. Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 53:450-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson, J. F., L. Moitoso de Vargas, C. Koch, R. Kahmann, and A. Landy. 1987. Cellular factors couple recombination with growth phase: characterization of a new component in the lambda site-specific recombination pathway. Cell 50:901-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]